Medieval Thessaly on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Thessaly covers the history of the region of

In the summer of 480 BC, the

In the summer of 480 BC, the

During the course of the 10th century, the Saracen threat receded and was practically ended as the result of the

During the course of the 10th century, the Saracen threat receded and was practically ended as the result of the

Following the sack of Constantinople and the dissolution of the Byzantine Empire by the Fourth Crusade in April 1204,

Following the sack of Constantinople and the dissolution of the Byzantine Empire by the Fourth Crusade in April 1204,  In 1212, however, Michael I Komnenos Doukas (), ruler of the independent Greek state of

In 1212, however, Michael I Komnenos Doukas (), ruler of the independent Greek state of

From his capital at Neopatras, John I Doukas governed Thessaly as a virtually independent state. Although he recognized the suzerainty of the Byzantine emperor

From his capital at Neopatras, John I Doukas governed Thessaly as a virtually independent state. Although he recognized the suzerainty of the Byzantine emperor

The Catalans continued for a while to hold the parts of southern Thessaly they had occupied and raided the region in the following years, while John Doukas' authority was increasingly enfeebled in Thessaly itself at the expense of the large landholders, who became virtually autonomous, maintaining their own, independent contacts with the Byzantine court. As a result, probably , John too was forced to formalize his relations with the Byzantines, recognizing the Empire's suzerainty and marrying Irene Palaiologina, the illegitimate daughter of Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos. When John Doukas died in 1318, the southern part of Thessaly was quickly captured by the Catalans of Athens. Between 1318 and 1325, the Catalans took Neopatras, Zetounion,

The Catalans continued for a while to hold the parts of southern Thessaly they had occupied and raided the region in the following years, while John Doukas' authority was increasingly enfeebled in Thessaly itself at the expense of the large landholders, who became virtually autonomous, maintaining their own, independent contacts with the Byzantine court. As a result, probably , John too was forced to formalize his relations with the Byzantines, recognizing the Empire's suzerainty and marrying Irene Palaiologina, the illegitimate daughter of Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos. When John Doukas died in 1318, the southern part of Thessaly was quickly captured by the Catalans of Athens. Between 1318 and 1325, the Catalans took Neopatras, Zetounion,

The Ottomans first invaded Thessaly in 1386, when

The Ottomans first invaded Thessaly in 1386, when

Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, The ...

in north-central Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

from antiquity to the present day.

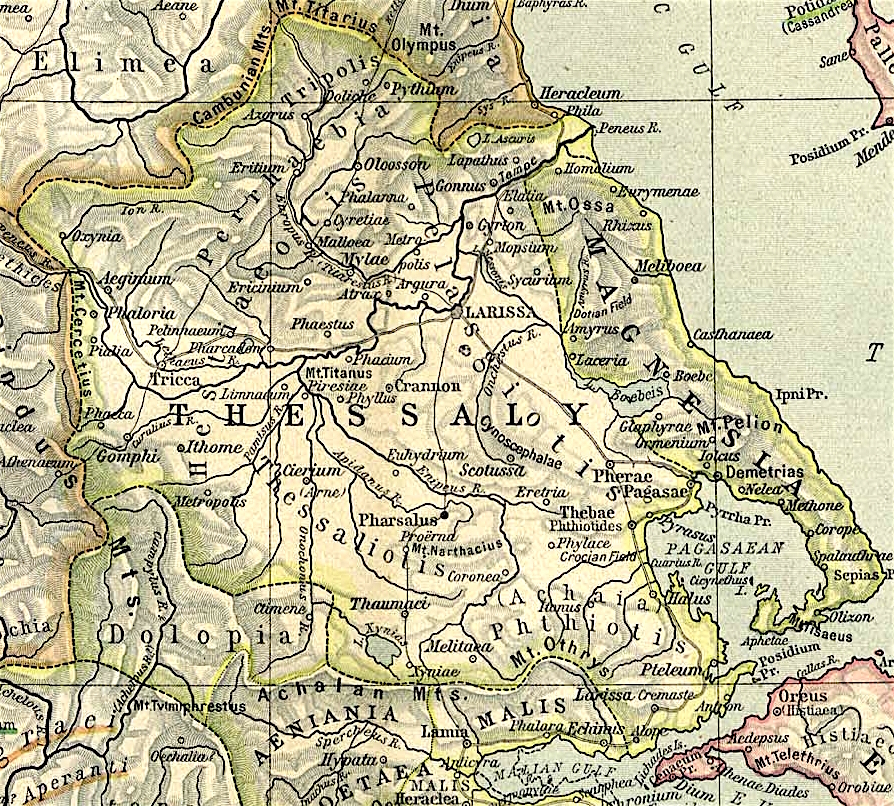

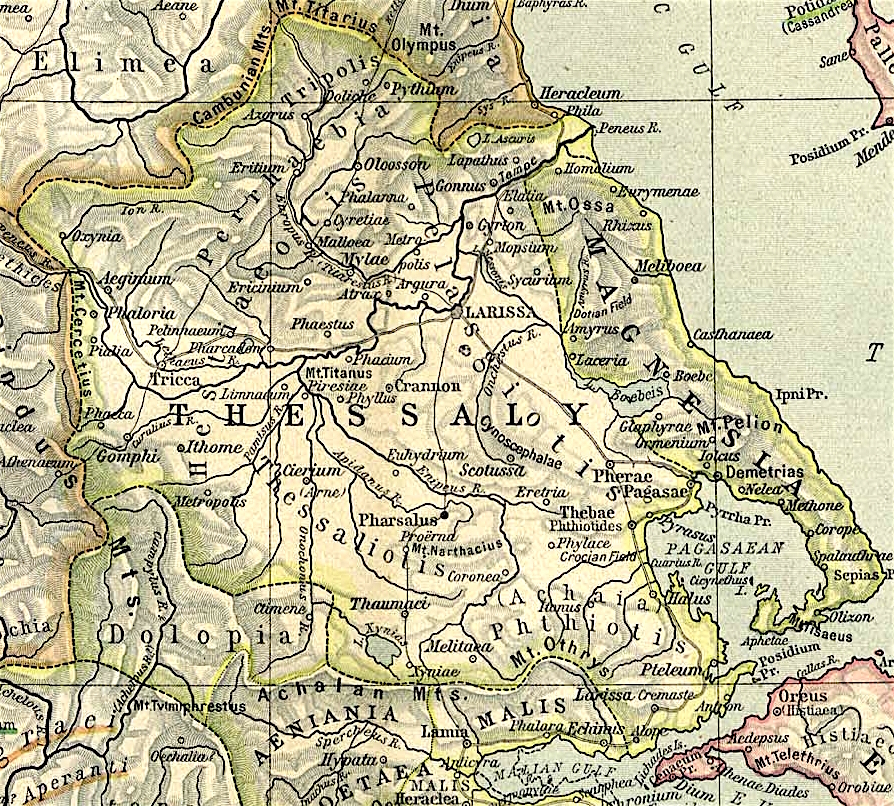

Topography

Thessaly is characterized by the largeThessalian plain

The Thessalian plain ( el, Θεσσαλική πεδιάδα, Θεσσαλικός κάμπος) is the dominant geographical feature of the Greek region of Thessaly.

The plain is formed by the Pineios River and its tributaries and is surrounded ...

, formed by the Pineios River, which is surrounded by mountains, most notably the Pindus

The Pindus (also Pindos or Pindhos; el, Πίνδος, Píndos; sq, Pindet; rup, Pindu) is a mountain range located in Northern Greece and Southern Albania. It is roughly 160 km (100 miles) long, with a maximum elevation of 2,637 metres ...

mountain range to the west, which separates Thessaly from Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

. Only two passes, the Porta pass and, in the summer, the pass of Metsovo

Metsovo ( el, Μέτσοβο; rup, Aminciu) is a town in Epirus, in the mountains of Pindus in northern Greece, between Ioannina to the west and Meteora to the east.

The largest centre of Aromanian (Vlach) life in Greece, Metsovo is a large r ...

, connect the two regions. From the south, the narrow coastal pass of Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: (''Thermopylai'') , Demotic Greek (Greek): , (''Thermopyles'') ; "hot gates") is a place in Greece where a narrow coastal passage existed in antiquity. It derives its name from its hot sulphur ...

connects Thessaly with southern Greece. In the north Thessaly borders on Macedonia, either through the coast or the pass of Servia towards Thessalonica

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

, or in the northwest towards western Macedonia.

Antiquity

The first evidence of human habitation inThessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, The ...

dates to the late Paleolithic, but in the early Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several p ...

this expanded rapidly. Over 400 archaeological sites dating to the period are known, including fortified ones. The most notable of these is at Sesklo

Sesklo ( el, Σέσκλο; rup, Seshklu) is a village in Greece that is located near Volos, a city located within the municipality of Aisonia. The municipality is located within the regional unit of Magnesia that is located within the admini ...

. During the Mycenaean period

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC.. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainland ...

, the main settlement was at Iolcos

Iolcus (; also rendered ''Iolkos'' ; grc, Ἰωλκός and Ἰαωλκός; grc-x-doric, Ἰαλκός; ell, Ιωλκός) is an ancient city, a modern village and a former municipality in Magnesia, Thessaly, Greece. Since the 2011 local gove ...

, as attested in the later legends of Jason

Jason ( ; ) was an ancient Greek mythological hero and leader of the Argonauts, whose quest for the Golden Fleece featured in Greek literature. He was the son of Aeson, the rightful king of Iolcos. He was married to the sorceress Medea. He ...

and the Argonauts.

Archaic period

A distinct Thessalian tribal identity and culture first began to form from the 9th century BC on as a mixture of the local population and immigrants from Epirus, first in the region of thePelasgiotis

Pelasgiotis ( grc, Πελασγιῶτις, Pelasgiōtis) was an elongated district of ancient Thessaly, extending from the Vale of Tempe in the north to the city of Pherae in the south. The Pelasgiotis included the following localities: Argos Pela ...

, with Pherae

Pherae (Greek: Φεραί) was a city and polis (city-state) in southeastern Ancient Thessaly. One of the oldest Thessalian cities, it was located in the southeast corner of Pelasgiotis. According to Strabo, it was near Lake Boebeïs 90 stadia ...

as its main centre. From there they quickly expanded inland to the plain of the Pineios and towards the Malian Gulf

The Malian or Maliac Gulf ( el, Μαλιακός Κόλπος, Maliakós Kólpos) is a gulf in the western Aegean Sea. It forms part of the coastline of Greece's region of Phthiotis. The gulf stretches east to west to a distance of , depending on ...

. The Thessalians spoke a distinct form of Aeolic Greek. In the late 7th century BC, the Thessalians conquered the so-called ''perioikoi''. In this process the Thessalians captured Anthela and came to control the local amphictyony

In Archaic Greece, an amphictyony ( grc-gre, ἀμφικτυονία, a "league of neighbors"), or amphictyonic league, was an ancient religious association of tribes formed before the rise of the Greek '' poleis''.

The six Dorian cities of coast ...

. By assuming the former share of the ''perioikoi'' in the Delphic Amphictyony

In Archaic Greece, an amphictyony ( grc-gre, ἀμφικτυονία, a "league of neighbors"), or amphictyonic league, was an ancient religious association of tribes formed before the rise of the Greek '' poleis''.

The six Dorian cities of coast ...

, the Thessalians also came to play a leading role in the latter, providing 14 of the 24 ''hieromnemones'' and presiding over the Pythian Games

The Pythian Games ( grc-gre, Πύθια;) were one of the four Panhellenic Games of Ancient Greece. They were held in honour of Apollo at his sanctuary at Delphi every four years, two years after the Olympic Games, and between each Nemean and ...

. As a result of the First Sacred War

The First Sacred War, or Cirraean War, was fought between the Amphictyonic League of Delphi and the city of Kirrha. At the beginning of the 6th century BC the Pylaeo-Delphic Amphictyony, controlled by the Thessalians, attempted to take hold of the ...

(595–585 BC), the Thessalians briefly extended their sway over Phocis

Phocis ( el, Φωκίδα ; grc, Φωκίς) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the administrative region of Central Greece. It stretches from the western mountainsides of Parnassus on the east to the mountain range of Var ...

as well, but the Boeotians drove them back after the battles of Hyampolis

Hyampolis (Ὑάμπολις ''Iabolis'') was a city in ancient Phocis, Greece. A native of this city was called a ''Hyampolites''. Some ancient authors record that the city was also called simply ''Hya''.

Mythology and situation

In the ancient tr ...

and Ceressus in the mid-6th century.

In the second half of the 7th century, Thessaly became the home of large aristocratic families, controlling huge tracts of land and working them with serfs ('' penestae''), which became a characteristic of Thessaly. The most important were the Aleuadae

The Aleuadae ( grc, Ἀλευάδαι) were an ancient Thessalian family of Larissa, who claimed descent from the mythical Aleuas. The Aleuadae were the noblest and most powerful among all the families of Thessaly, whence Herodotus calls its membe ...

of Larissa, the Echecratidae of Pharsalus

''Pharsalus''Melichar L (1906) ''Monographie der Issiden. (Homoptera). Abhandlungen der K. K. Zoologisch-botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien.'' Wien 3: 1-327 21 is the type genus of planthoppers in the subfamily Pharsalinae (family Ricaniidae); it ...

, and the Scopadae of Crannon

Cranon ( grc, Κρανών) or Crannon (Κραννών) was a town and polis (city-state) of Pelasgiotis, in ancient Thessaly, situated southwest of Larissa, and at the distance of 100 stadia from Gyrton, according to Strabo. Spelling differ ...

. Their clan chiefs were often called '' basileis'' ("kings"). It was Aleuas Pyrrhos ("the Red") who cemented the aristocracy's predominance by reforming the Thessalian League on the basis of the "tetrads" (quadripartite division), linking it with the noble-controlled ''kleroi'' ("land lots") obliged to supply 40 horsemen and 80 infantrymen each. Traditionally, the office of ''tagus

The Tagus ( ; es, Tajo ; pt, Tejo ; see below) is the longest river in the Iberian Peninsula. The river rises in the Montes Universales near Teruel, in mid-eastern Spain, flows , generally west with two main south-westward sections, to e ...

'' has been regarded as the senior magistrate of the Thessalian League; more recent studies however regard the ''tagus'' as a purely local official, and suggest the ''tetrarches'' as the head of the League.

Classical period

In the summer of 480 BC, the

In the summer of 480 BC, the Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian.

...

invaded Thessaly. The Greek army that guarded the Vale of Tempe

The Vale of Tempe ( el, Κοιλάδα των Τεμπών) is a gorge in the Tempi municipality of northern Thessaly, Greece, located between Olympus to the north and Ossa to the south, and between the regions of Thessaly and Macedonia.

The ...

evacuated the road before the enemy arrived. Not much later, Thessaly surrendered. The Thessalian family of Aleuadae

The Aleuadae ( grc, Ἀλευάδαι) were an ancient Thessalian family of Larissa, who claimed descent from the mythical Aleuas. The Aleuadae were the noblest and most powerful among all the families of Thessaly, whence Herodotus calls its membe ...

joined the Persians. In the Peloponnesian War the Thessalians tended to side with Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

and usually prevented Spartan

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta refe ...

troops from crossing through their territory with the exception of the army of Brasidas

Brasidas ( el, Βρασίδας, died 422 BC) was the most distinguished Spartan officer during the first decade of the Peloponnesian War who fought in battle of Amphipolis and Pylos. He died during the Second Battle of Amphipolis while winning ...

. In the 4th century BC Thessaly became dependent on Macedon

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an Classical antiquity, ancient monarchy, kingdom on the periphery of Archaic Greece, Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. Th ...

. In the 2nd century BC, as with the rest of Greece, Thessaly came under the control of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

.

Roman period

From 27 BC it formed part of theRoman province

The Roman provinces (Latin: ''provincia'', pl. ''provinciae'') were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was rule ...

of Achaea, with capital at Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government refor ...

. In the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius

Antoninus Pius ( Latin: ''Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius''; 19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Born into a senatori ...

(), Thessaly was separated from Achaea and given to the province of Macedonia; eventually it became a separate province. In the new administrative system as it evolved under Diocletian () and his successors, Thessaly was a separate province within the Diocese of Macedonia, in the praetorian prefecture of Illyricum

The praetorian prefecture of Illyricum ( la, praefectura praetorio per Illyricum; el, ἐπαρχότης/ὑπαρχία �ῶν πραιτωρίωντοῦ Ἰλλυρικοῦ, also termed simply the Prefecture of Illyricum) was one of four ...

. With the division of the Roman Empire in 395, Thessaly remained as a part of the East Roman (Byzantine) Empire.

Being far from the Empire's frontiers, and of little strategic importance, Greece lacked any serious fortifications or permanently stationed garrisons, a situation that lasted until the 6th century and led to much devastation by barbarian raids. Thus in 395–397, as most of Greece, Thessaly was occupied by the Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

under Alaric, until they were driven out by Stilicho

Flavius Stilicho (; c. 359 – 22 August 408) was a military commander in the Roman army who, for a time, became the most powerful man in the Western Roman Empire. He was of Vandal origins and married to Serena, the niece of emperor Theodosiu ...

. The Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The Vandals migrated to the area betw ...

under Geiseric

Gaiseric ( – 25 January 477), also known as Geiseric or Genseric ( la, Gaisericus, Geisericus; reconstructed Vandalic: ) was King of the Vandals and Alans (428–477), ruling a kingdom he established, and was one of the key players in the dif ...

raided the coasts of Greece in the period 466–475, and in 473 the Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

under Theodemir Theodemir, Theodemar, Theudemer or Theudimer was a Germanic name common among the various Germanic peoples of early medieval Europe. According to Smaragdus of Saint-Mihiel (9th century), the form ''Theudemar'' is Frankish and ''Theudemir'' is Gothi ...

advanced into Thessaly and captured Larissa before Emperor Leo I

The LEO I (Lyons Electronic Office I) was the first computer used for commercial business applications.

The prototype LEO I was modelled closely on the Cambridge EDSAC. Its construction was overseen by Oliver Standingford, Raymond Thompson and ...

gave in and allowed him and his people to settle in Macedonia. Under Theodemir's son, Theodoric the Great

Theodoric (or Theoderic) the Great (454 – 30 August 526), also called Theodoric the Amal ( got, , *Þiudareiks; Greek: , romanized: ; Latin: ), was king of the Ostrogoths (471–526), and ruler of the independent Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy ...

, the Ostrogoths once more invaded Thessaly in 482, until they left for Italy in 488. According to the '' Synecdemus'', in the 6th century the province included 16 cities along the capital, Larissa: Demetrias

Demetrias ( grc, Δημητριάς) was a Greek city in Magnesia in ancient Thessaly (east central Greece), situated at the head of the Pagasaean Gulf, near the modern city of Volos.

History

It was founded in 294 BCE by Demetrius Polior ...

, Phthiotic Thebes

Phthiotic Thebes ( grc, Θῆβαι Φθιώτιδες, Thebai Phthiotides or Φθιώτιδες Θήβες or Φθιώτιδος Θήβες; la, Thebae Phthiae) or Thessalian Thebes (Θῆβαι Θεσσαλικαἰ, ''Thebai Thessalikai'') was ...

, Echinos

Echinos ( el, Εχίνος; bg, Шахин, ''Shahin''; tr, Şahin) is a village and a community in the municipality Myki. Before the 2011 local government reform it was part of the municipality of Myki, of which it was a municipal district. T ...

, Lamia

LaMia Corporation S.R.L., operating as LaMia (short for ''Línea Aérea Mérida Internacional de Aviación''), was a Bolivian charter airline headquartered in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, as an EcoJet subsidiary. It had its origins from the failed ...

, Hypata

Ypati ( el, Υπάτη) is a village and a former municipality in Phthiotis, central peninsular Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality of Lamia, of which it is a municipal unit. The municipal unit has an a ...

, Metropolis, Trikke

The Trikke works by shifting body weight

The Trikke ( ; also known as a wiggle scooter, scissor scooter, carver scooter, and Y scooter) is a chainless, pedalless, personal vehicle with a three-wheel frame. The rider stands on two foot platform ...

, Gomphoi

Gomfoi (Greek: Γόμφοι, before 1930: Ραψίστα - ''Rapsista''; la, Gomphi) is a village and a former municipality in the Trikala regional unit, Thessaly, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pyl ...

, Caesarea, Diocletianopolis, Pharsalus

''Pharsalus''Melichar L (1906) ''Monographie der Issiden. (Homoptera). Abhandlungen der K. K. Zoologisch-botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien.'' Wien 3: 1-327 21 is the type genus of planthoppers in the subfamily Pharsalinae (family Ricaniidae); it ...

, Saltos Bouramesios

Saltos is a barrio in the municipality of Orocovis, Puerto Rico. Its population in 2010 was 3,238.

History

Puerto Rico was ceded by Spain in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War under the terms of the Treaty of Paris of 1898 and became an ...

, Saltos Iovios, and the islands of Skiathos

Skiathos ( el, Σκιάθος, , ; grc, Σκίαθος, ; and ) is a small Greek island in the northwest Aegean Sea. Skiathos is the westernmost island in the Northern Sporades group, east of the Pelion peninsula in Magnesia on the mainland ...

, Skopelos

Skopelos ( el, Σκόπελος, ) is a Greek island in the western Aegean Sea. Skopelos is one of several islands which comprise the Northern Sporades island group, which lies east of the Pelion peninsula on the mainland and north of the island ...

and Peparisthos.

From the reign of Justin I

Justin I ( la, Iustinus; grc-gre, Ἰουστῖνος, ''Ioustînos''; 450 – 1 August 527) was the Eastern Roman emperor from 518 to 527. Born to a peasant family, he rose through the ranks of the army to become commander of the imperial ...

() on, attacks on the imperial frontier on the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

became more and more frequent, and the Balkan provinces were heavily raided, although Greece was less affected. In 539, however, a large Hunnic raid plundered Thessaly and, bypassing the fortified Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: (''Thermopylai'') , Demotic Greek (Greek): , (''Thermopyles'') ; "hot gates") is a place in Greece where a narrow coastal passage existed in antiquity. It derives its name from its hot sulphur ...

pass, devastated Central Greece

Continental Greece ( el, Στερεά Ελλάδα, Stereá Elláda; formerly , ''Chérsos Ellás''), colloquially known as Roúmeli (Ρούμελη), is a traditional geographic region of Greece. In English, the area is usually called Central ...

. This led to a serious fortification effort under Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renova ...

(), and the establishment of a permanent garrison at Thermopylae. The area was once more invaded in 558 by the Kotrigurs

Kutrigurs were Turkic nomadic equestrians who flourished on the Pontic–Caspian steppe in the 6th century AD. To their east were the similar Utigurs and both possibly were closely related to the Bulgars. They warred with the Byzantine Empire an ...

, but they were stopped at the Thermopylae. Despite the devastation caused by these raids, in Thessaly, and southern Greece in general, the imperial administration seems to have continued to function, and traditional public life to have continued, for much of the century, possibly up to the end of the reign of Justin II

Justin II ( la, Iustinus; grc-gre, Ἰουστῖνος, Ioustînos; died 5 October 578) or Justin the Younger ( la, Iustinus minor) was Eastern Roman Emperor from 565 until 578. He was the nephew of Justinian I and the husband of Sophia, the ...

(). Nevertheless, the barbarian raids, the two great earthquakes of 522 and 552, and the arrival of the Plague of Justinian

The plague of Justinian or Justinianic plague (541–549 AD) was the first recorded major outbreak of the first plague pandemic, the first Old World pandemic of plague, the contagious disease caused by the bacterium ''Yersinia pestis''. The dis ...

in 541–544, led to a drop in population.

Middle Ages

Slavic invasions and restoration of Byzantine control

Thelate antique

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English has ...

order on Greece was irrevocably shattered with the Slavic incursions that began after 578. The first large-scale raid was in 581, and the Slavs appear to have remained in Greece until 584. Byzantium, confronted by long and bloody wars with Sassanid Persia

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

in the east, and with the Avar Khaganate in the north, was largely unable to stop these raids. After the murder of Emperor Maurice Maurice may refer to:

People

* Saint Maurice (died 287), Roman legionary and Christian martyr

* Maurice (emperor) or Flavius Mauricius Tiberius Augustus (539–602), Byzantine emperor

*Maurice (bishop of London) (died 1107), Lord Chancellor and ...

in 602 and the outbreak of the great Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

frontier, somewhat stabilized under Maurice, collapsed entirely, leaving the Balkans defenceless for the Slavs to raid and settle. The Slavic settlement that followed the raids in the late 6th and early 7th centuries affected the Peloponnese in the south and Macedonia in the north far more than Thessaly or Central Greece, with the fortified towns largely remaining in the hands of the native Greek population. Nevertheless, in the first decades of the 7th century the Slavs were free to raid Thessaly and further south relatively unhindered; according to the ''Miracles of Saint Demetrius

The ''Miracles of Saint Demetrius'' ( la, Miracula Sancti Demetrii) is a 7th-century collection of homilies, written in Greek, accounting the miracles performed by the patron saint of Thessalonica, Saint Demetrius. It is a unique work for the ...

'', in the Slavic tribes even built monoxyla

A dugout canoe or simply dugout is a boat made from a hollowed tree. Other names for this type of boat are logboat and monoxylon. ''Monoxylon'' (''μονόξυλον'') (pl: ''monoxyla'') is Greek – ''mono-'' (single) + '' ξύλον xylon'' (t ...

and raided the coasts of Thessaly and many Aegean islands, depopulating many of them. Five of Thessaly's cities disappear from the sources during the 7th century, and Slavs settled in the northern and northeastern parts of the country. Emperor Constans II () undertook in 658 the first attempt to restore imperial rule, and although his campaign was mostly carried out in the northern Aegean coast, it seems to have led to a relative pacification of the Slavic tribes in southern Greece as well, at least for a few years. Thus during the great Slavic siege of Thessalonica in the tribe of the Belegezitai, who according to the ''Miracles of Saint Demetrius'' were settled around Demetrias and Phthiotic Thebes, provided the besieged city with grain.

The parts of Thessaly that remained in imperial hands after the Slavic invasions—apparently the Aegean coast and the area around the Pagasetic Gulf

The Pagasetic Gulf ( el, Παγασητικός κόλπος, Pagasitikós kólpos) is a rounded gulf (max. depth 102 metres) in the Magnesia regional unit (east central Greece) that is formed by the Mount Pelion peninsula. It is connected with ...

—came under the theme

Theme or themes may refer to:

* Theme (arts), the unifying subject or idea of the type of visual work

* Theme (Byzantine district), an administrative district in the Byzantine Empire governed by a Strategos

* Theme (computing), a custom graphical ...

of Hellas. This was established between 687 and 695, and comprised the eastern coasts of mainland Greece, and possibly the Peloponnese, as well as Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poin ...

and a few other islands. Its '' strategos'' was probably based in (Boeotian) Thebes. Given its lack of depth into the hinterland

Hinterland is a German word meaning "the land behind" (a city, a port, or similar). Its use in English was first documented by the geographer George Chisholm in his ''Handbook of Commercial Geography'' (1888). Originally the term was associated ...

, the theme was originally probably oriented mostly towards the sea and was of a mostly maritime character, as seen during the anti-iconoclast

Iconoclasm (from Greek: grc, εἰκών, lit=figure, icon, translit=eikṓn, label=none + grc, κλάω, lit=to break, translit=kláō, label=none)From grc, εἰκών + κλάω, lit=image-breaking. ''Iconoclasm'' may also be conside ...

revolt of 726/7. Some time between 730 and 751, the Church in Thessaly, along with the rest of the Illyricum, were transferred from the jurisdiction of the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

to that of the Patriarch of Constantinople.

Like much of northern Greece, Thessaly suffered from raids by the Bulgarians

Bulgarians ( bg, българи, Bǎlgari, ) are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and the rest of Southeast Europe.

Etymology

Bulgarians derive their ethnonym from the Bulgars. Their name is not completely unders ...

, beginning in 773. At the same time, due to conflict between the Bulgarian ruling class and the Slavic population which led to an exodus from the latter, a second wave of Slavic settlement engulfed Greece from on. Unlike the first wave of settlement, this does not seem to have disrupted imperial control in the areas where it had been (re-)established. In 783, however, the eunuch minister Staurakios led a large-scale campaign across Greece from Thessalonica

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

to the Peloponnese, subduing the local Slavs and forcing them to acknowledge imperial overlordship. Despite continued raids by the Bulgarians and Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Pe ...

pirates—Demetrias was sacked by Damian of Tarsus Damian of Tarsus (Greek: Δαμιανός ό Ταρσεύς, ; died 924), surnamed Ghulam Yazman (" slave/page of Yazman"), was a Byzantine Greek convert to Islam, governor of Tarsus in 896–897 and one of the main leaders of naval raids against t ...

in 902 and Thessaly and much of Central Greece devastated by Bulgarian raids in 918 and 923–926—Thessaly, and Greece in general, recovered gradually after Byzantine control was firmly re-established, and there are signs of renewed prosperity and economic activity. Especially in Thessaly, this process manifested itself in the appearance of at least nine new cities, including Halmyros and Stagoi, and the resettlement of older ones, such as Zetounion (ancient Lamia).

Byzantine rule in the 10th–12th centuries

Byzantine reconquest of Crete

The siege of Chandax in 960-961 was the centerpiece of the Byzantine Empire's campaign to recover the island of Crete which since the 820s had been ruled by Muslim Arabs. The campaign followed a series of failed attempts to reclaim the island fro ...

in 960–961. The threat from Bulgaria remained, however, and in 986, during his wars with Basil II

Basil II Porphyrogenitus ( gr, Βασίλειος Πορφυρογέννητος ;) and, most often, the Purple-born ( gr, ὁ πορφυρογέννητος, translit=ho porphyrogennetos).. 958 – 15 December 1025), nicknamed the Bulgar S ...

(), the Bulgarian tsar Samuel sacked the city of Larissa and occupied Thessaly. The Bulgarian ruler undertook another large-scale expedition through the province and into the Peloponnese in 997, but on his return he suffered a devastating defeat at the Battle of Spercheios

The Battle of Spercheios ( bg, Битка при Сперхей, el, Μάχη του Σπερχειού) took place in 997 AD, on the shores of the Spercheios river near the city of Lamia in central Greece. It was fought between a Bulgarian army ...

. In the early 11th century, Thessaly was separated from Hellas and joined to the theme of Thessalonica

The Theme of Thessalonica ( el, Θέμα Θεσσαλονίκης) was a military-civilian province (''thema'' or theme (Byzantine administrative unit), theme) of the Byzantine Empire located in the southern Balkans, comprising varying parts of Ce ...

. The Spercheios

The Spercheios (, ''Sperkheiós''), also known as the Spercheus from its Latin name, is a river in Phthiotis in central Greece. It is long, and its drainage area is . It was worshipped as a god in the ancient Greek religion and appears in some c ...

valley however remained part of Hellas, with the new border running along the Othrys

Mount Othrys ( el, όρος Όθρυς – ''oros Othrys'', also Όθρη – ''Othri'') is a mountain range of central Greece, in the northeastern part of Phthiotis and southern part of Magnesia. Its highest summit, ''Gerakovouni'', situated on ...

–Agrafa

Agrafa ( el, Άγραφα, ) is a mountainous region in Evrytania and Karditsa regional units in mainland Greece, consisting mainly of small villages. It is the southernmost part of the Pindus range. There is also a municipality with the same n ...

line. The region enjoyed a long period of peace at this time, interrupted only by raids during the uprising of Petar Delyan

The Uprising of Peter Delyan ( bg, Въстанието на Петър Делян, el, Επανάσταση του Πέτρου Δελεάνου), which took place in 1040–1041, was a major Bulgarian rebellion against the Byzantine Empire in ...

(1040–1041), plundering by the Uzès

Uzès (; ) is a commune in the Gard department in the Occitanie region of Southern France. In 2017, it had a population of 8,454. Uzès lies about north-northeast of Nîmes, west of Avignon and south-east of Alès.

History

Originally ''Uc ...

in 1064, and the brief Norman attack into Thessaly in 1082–1083, which was beaten back by Emperor Alexios I Komnenos

Alexios I Komnenos ( grc-gre, Ἀλέξιος Κομνηνός, 1057 – 15 August 1118; Latinized Alexius I Comnenus) was Byzantine emperor from 1081 to 1118. Although he was not the first emperor of the Komnenian dynasty, it was during ...

(). The Vlachs

"Vlach" ( or ), also "Wallachian" (and many other variants), is a historical term and exonym used from the Middle Ages until the Modern Era to designate mainly Romanians but also Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, Istro-Romanians and other E ...

are first mentioned in Thessaly during the 11th century, in the ''Strategikon of Kekaumenos

The ''Strategikon of Kekaumenos'' ( el, Στρατηγικὸν τοῦ Κεκαυμένου, la, Cecaumeni Strategicon) is a late 11th century Byzantine manual offering advice on warfare and the handling of public and domestic affairs.

The bo ...

'' and Anna Komnene

Anna Komnene ( gr, Ἄννα Κομνηνή, Ánna Komnēnḗ; 1 December 1083 – 1153), commonly Latinized as Anna Comnena, was a Byzantine princess and author of the ''Alexiad'', an account of the reign of her father, the Byzantine emperor, ...

's '' Alexiad''. In the 12th century, the Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela recorded the existence of the district of "Vlachia" near Halmyros, while the Byzantine historian Niketas Choniates placed a " Great Vlachia" near Meteora

The Meteora (; el, Μετέωρα, ) is a rock formation in central Greece hosting one of the largest and most precipitously built complexes of Eastern Orthodox monasteries, second in importance only to Mount Athos.Sofianos, D.Z.: "Metéora" ...

. The term is also used by the 13th-century scholar George Pachymeres

George Pachymeres ( el, Γεώργιος Παχυμέρης, Geórgios Pachyméris; 1242 – 1310) was a Byzantine Greek historian, philosopher, music theorist and miscellaneous writer.

Biography

Pachymeres was born at Nicaea, in Bithynia, wher ...

, and it appears as a distinct administrative unit in 1276, when the ''pinkernes ''Pinkernes'' ( grc, πιγκέρνης, pinkernēs), sometimes also ''epinkernes'' (, ''epinkernēs''), was a high Byzantine court position.

The term derives from the Greek verb (''epikeránnymi'', "to mix ine), and was used to denote the cup- ...

'' Raoul Komnenos was its governor ('' kephale''). Thessalian Vlachia was apparently also known as "Vlachia in Hellas".

In the aftermath of the failed Norman invasion, Alexios I granted the first trading privileges to the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

, including immunity from taxation and the right to establish trade colonies in certain towns; in Thessaly, this was Demetrias. These concessions signalled the beginning of the ascendancy of the Italian maritime republics

The maritime republics ( it, repubbliche marinare), also called merchant republics ( it, repubbliche mercantili), were thalassocratic city-states of the Mediterranean Basin during the Middle Ages. Being a significant presence in Italy in the M ...

in maritime commerce and their gradual takeover of the Byzantine economy. Alexios' successors tried to curb these privileges with mixed success, but in 1198 Alexios III Angelos () was forced to concede even more extensive ones, allowing the Venetians to create trade stations at Vlachia, the "two Halmyroi", Grebenikon, Pharsalus, Domokos, Vesaina, Ezeros, Dobrochouvista, Trikala, Larissa, and Platamon

Platamon, or Platamonas (, ''Platamónas''), is a town and sea-side resort in south Pieria, Central Macedonia, Greece. Platamon has a population of about 2,000 permanent inhabitants. It is part of the Municipal unit of East Olympos of the Dio-Oly ...

.

Sometime in the 12th century, Thessaly reverted to Hellas, with the exception of the northwestern portion around Stagoi and Trikala, which was included in the new theme of Servia. Benjamin of Tudela, who visited the area in 1165, also recorded the presence of Jewish communities at Halmyros, Zetounion, Vesaina, and Gardiki. Both Benjamin and the Arab geographer al-Idrisi describe Greece during the middle of the 12th century as densely populated and prosperous. The situation began to change towards the end of the reign of Manuel I Komnenos (), whose costly military ventures led to a hike in taxation. Coupled with the corruption and autocratic behaviour of officials, this led to a decline in industry and the impoverishment of the peasantry, eloquently lamented by the Metropolitan of Athens

The Archbishopric of Athens ( el, Ιερά Αρχιεπισκοπή Αθηνών) is a Greek Orthodox archiepiscopal see based in the city of Athens, Greece. It is the senior see of Greece, and the seat of the autocephalous Church of Greece. Its ...

, Michael Choniates

Saint Michael Choniates (or Acominatus; el, ; c. 1140 – 1220) was a Byzantine Greek writer and cleric, born at Chonae (the ancient Colossae). At an early age he studied at Constantinople and was the pupil of Eustathius of Thessalonica. Around ...

. This decline was temporarily halted under Andronikos I Komnenos

Andronikos I Komnenos ( gr, Ἀνδρόνικος Κομνηνός; – 12 September 1185), Latinized as Andronicus I Comnenus, was Byzantine emperor from 1183 to 1185. He was the son of Isaac Komnenos and the grandson of the emperor Al ...

(), who sent the capable Nikephoros Prosouch as governor to Greece, but resumed after Andronikos' fall. In 1199–1201 Manuel Kamytzes

Manuel Kamytzes Komnenos Doukas Angelos ( gr, Μανουήλ Καμύτζης Κομνηνός Δούκας Ἄγγελος; after 1202) was a Byzantine general who was active in the late 12th century, and led an unsuccessful rebellion in 1201� ...

, the rebellious son-in-law of Byzantine emperor Alexios III Angelos (), with the support of Dobromir Chrysos

Dobromir, known to the Byzantines as Chrysos ( mk, Добромир Хрс, bg, Добромир Хриз, el, Δοβρομηρός Χρύσος), was a leader of the Vlachs and Bulgarian Slavs in eastern Macedonia during the reign of the Byzan ...

, the autonomous ruler of Prosek Prosek or Prošek may refer to:

Places

* Prosek, North Macedonia, an archaeological site in North Macedonia

* Prosek, Niška Banja, a village in Serbia

* Prosek (Prague), a neighbourhood in Prague

** Prosek (Prague Metro), a Prague Metro station

...

, established a short-lived principality in northern Thessaly, before he was overcome by an imperial expedition.

By the end of the 12th century, the theme of Hellas had been superseded by a collection of smaller districts variously termed ''horia'' (sing. ''horion''), ''chartoularata'' (sing. ''chartoularaton''), and '' episkepseis'' (sing. ''episkepsis''). This division is reflected in the 1198 chrysobull of Alexios III to the Venetians, and in the ''Partitio Romaniae

The ''Partitio terrarum imperii Romaniae'' (Latin for "Partition of the lands of the empire of ''Romania'' .e., the Byzantine Empire, or ''Partitio regni Graeci'' ("Partition of the kingdom of the Greeks"), was a treaty signed among the crusader ...

'' of 1204. These documents mention the ''episkepseis'' (domains of the imperial family) of Platamon, Demetrias, the "two Halmyroi", Krevennika and Pharsalus, Domokos and Vesaina, the ''horion'' of Larissa and the "provinces" of Vlachia, Servia, and Velechativa, and the ''chartoularata'' of Dobrochouvista and Ezeros (Sthlanitsa in the ''Partitio''), the latter evidently Slavic settlements.

Latin and Epirote rule

Following the sack of Constantinople and the dissolution of the Byzantine Empire by the Fourth Crusade in April 1204,

Following the sack of Constantinople and the dissolution of the Byzantine Empire by the Fourth Crusade in April 1204, Leo Sgouros

Leo Sgouros ( el, Λέων Σγουρός), Latinized as Leo Sgurus, was a Greek independent lord in the northeastern Peloponnese in the early 13th century. The scion of the magnate Sgouros family, he succeeded his father as hereditary lord in th ...

, the Greek ruler of Nauplia

Nafplio ( ell, Ναύπλιο) is a coastal city located in the Peloponnese in Greece and it is the capital of the regional unit of Argolis and an important touristic destination. Founded in antiquity, the city became an important seaport in the ...

, marched into central Greece. At Larissa he met the deposed Alexios III, and concluded a marriage alliance with him. Both were soon confronted by the Crusaders under Boniface of Montferrat

Boniface I, usually known as Boniface of Montferrat ( it, Bonifacio del Monferrato, link=no; el, Βονιφάτιος Μομφερρατικός, ''Vonifatios Momferratikos'') (c. 1150 – 4 September 1207), was the ninth Marquis of Montferrat ( ...

, who sought to expand his newly established Kingdom of Thessalonica

The Kingdom of Thessalonica () was a short-lived Crusader State founded after the Fourth Crusade over conquered Byzantine lands in Macedonia and Thessaly.

History

Background

After the fall of Constantinople to the crusaders in 1204, Bonif ...

into southern Greece. Unable to challenge the Crusaders in open battle, Sgouros gave up Thessaly without a fight, and withdrew to his bases in the Peloponnese. Boniface divided the captured lands among his followers: Platamon went to Rolando Piscia, Larissa and Halmyros to the Lombard Guglielmo, and Velestino

Velestino ( el, Βελεστίνο; rup, Velescir) is a town in the Magnesia regional unit, Thessaly, Greece. It is the seat of the municipality Rigas Feraios.

Location

It is situated at elevation on a hillside, at the southeastern end o ...

to Berthold of Katzenellenbogen, while further south in Central Greece Bodonitza went to Guido Pallavicini, Gravia

Gravia ( el, Γραβιά) is a village and a former municipality in the northeastern part of Phocis, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Delphi, of which it is a municipal unit. The municipal unit has ...

to Jacques de Saint Omer, Salona

Salona ( grc, Σάλωνα) was an ancient city and the capital of the Roman province of Dalmatia. Salona is located in the modern town of Solin, next to Split, in Croatia.

Salona was founded in the 3rd century BC and was mostly destroyed in ...

to Thomas d'Autremencourt, Thebes to the brothers Albertino and Rolando Canossa, Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

to Othon de la Roche

Othon de la Roche, also Otho de la Roche (died before 1234), was a Burgundian nobleman of the De la Roche family from La Roche-sur-l'Ognon. He joined the Fourth Crusade and became the first Frankish Lord of Athens in 1204. In addition to Athen ...

, and Euboea ( Negroponte) to Jacques d'Avesnes

James (also ''Jacques'' or ''Jacob''; 1152 – 7 September 1191) was a son of Nicholas d'Oisy, Lord of Avesnes and Matilda de la Roche. He was the lord of Avesnes, Condé, and Leuze from 1171. In November 1187, James joined the Third Crusad ...

. The boundaries of the actual Kingdom of Thessalonica seem to have extended only up to Domokos, Pharsalus, and Velestino: the Spercheios valley in southern Thessaly, with the towns of Zetounion and Ravennika

Ravennika or Ravenica was a medieval settlement in Central Greece.

Ravennika is first mentioned as "Rovinaca" by the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela, who reported 100 Jewish families there. The name is most likely of Slavic origin, its meani ...

, was under governors appointed by the Latin Emperor

The Latin Emperor was the ruler of the Latin Empire, the historiographical convention for the Crusader realm, established in Constantinople after the Fourth Crusade (1204) and lasting until the city was recovered by the Byzantine Greeks in 126 ...

.

In 1212, however, Michael I Komnenos Doukas (), ruler of the independent Greek state of

In 1212, however, Michael I Komnenos Doukas (), ruler of the independent Greek state of Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

, led his troops into Thessaly, overrunning the resistance of the local Lombard nobles. Larissa and much of central Thessaly came under Epirote rule, thereby separating Thessalonica from the Crusader principalities in southern Greece. Michael's work was completed by his half-brother and successor, Theodore Komnenos Doukas

Theodore Komnenos Doukas ( el, Θεόδωρος Κομνηνὸς Δούκας, ''Theodōros Komnēnos Doukas'', Latinized as Theodore Comnenus Ducas, died 1253) was ruler of Epirus and Thessaly from 1215 to 1230 and of Thessalonica and most ...

(), who by completed the recovery of the entire region except for Halmyros, which remained in Latin hands until 1246. Eventually, in December 1224, Theodore conquered Thessalonica as well. Soon thereafter he declared himself emperor, founding the Empire of Thessalonica

The Empire of Thessalonica is a historiographic term used by some modern scholarse.g. ,, , . to refer to the short-lived Byzantine Greek state centred on the city of Thessalonica between 1224 and 1246 (''sensu stricto'' until 1242) and ruled by t ...

. The region remained attached to Thessalonica until 1239, when the deposed ruler of Thessalonica Manuel Komnenos Doukas

Manuel Komnenos Doukas, Latinized as Ducas ( el, Μανουήλ Κομνηνός Δούκας, ''Manouēl Komnēnos Doukas''; c. 1187 – c. 1241), commonly simply Manuel Doukas (Μανουήλ Δούκας) and rarely also called Manuel Angelos ...

captured it from his nephew John Komnenos Doukas and secured its status as a separate section of the family holdings. Upon his death in 1241, the area quickly, and apparently without resistance, came under the control of the ruler of Epirus, Michael II Komnenos Doukas

Michael II Komnenos Doukas, Latinized as Comnenus Ducas ( el, Μιχαήλ Β΄ Κομνηνός Δούκας, ''Mikhaēl II Komnēnos Doukas''), often called Michael Angelos in narrative sources, was from 1230 until his death in 1266/68 the rule ...

(). Following the Battle of Pelagonia in 1259, Thessaly was occupied by the Empire of Nicaea, but an Epirote counter-offensive in spring 1260 under Nikephoros I Komnenos Doukas

Nikephoros I Komnenos Doukas, Latinized as Nicephorus I Comnenus Ducas ( el, Νικηφόρος Κομνηνός Δούκας, Nikēphoros Komnēnos Doukas; – ) was ruler of Epirus from 1267/8 to his death in 1296/98.

Life

Born around 1240 ...

defeated the Nicaean general Alexios Strategopoulos

Alexios Komnenos Strategopoulos ( gr, Ἀλέξιος Κομνηνὸς Στρατηγόπουλος) was a Byzantine aristocrat and general who rose to the rank of '' megas domestikos'' and ''Caesar''. Distantly related to the Komnenian dynasty ...

and recovered most of the province, except perhaps for part of the Aegean coast around Volos

Volos ( el, Βόλος ) is a coastal port city in Thessaly situated midway on the Greek mainland, about north of Athens and south of Thessaloniki. It is the sixth most populous city of Greece, and the capital of the Magnesia regional unit ...

, which possibly remained in Nicaean hands for several years thereafter.

Thessaly as an autonomous principality

On the death of Michael II in 1267/8, his dominions were divided between Nikephoros, who received Epirus proper, and Michael's illegitimate son John Doukas (), who was married to a Thessalian Vlach princess, received Thessaly. Although separated politically, Thessaly continued to share many similarities with the parent state of Epirus: both were reluctant to acknowledge the revivedPalaiologos

The House of Palaiologos ( Palaiologoi; grc-gre, Παλαιολόγος, pl. , female version Palaiologina; grc-gre, Παλαιολογίνα), also found in English-language literature as Palaeologus or Palaeologue, was a Byzantine Greek f ...

-led Byzantine Empire and its imperial pretensions, both established close ties with the Latin states of southern Greece in an attempt to maintain their independence, while at the same time being threatened by them and forced to cede territory to them. Both were eventually reunified under the Byzantines in the 1330s and the Serbians shortly after.

Michael VIII Palaiologos

Michael VIII Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( el, Μιχαὴλ Δούκας Ἄγγελος Κομνηνὸς Παλαιολόγος, Mikhaēl Doukas Angelos Komnēnos Palaiologos; 1224 – 11 December 1282) reigned as the co-emperor of the Empire ...

(), receiving the title of ''sebastokrator

''Sebastokrator'' ( grc-byz, Σεβαστοκράτωρ, Sevastokrátor, August Ruler, ; bg, севастократор, sevastokrator; sh, sebastokrator), was a senior court title in the late Byzantine Empire. It was also used by other rulers wh ...

'' in exchange, John I Doukas maintained a consistent anti-Palaiologan stance. In this conflict he allied himself with Latin powers, namely Charles of Anjou

Charles I (early 1226/12277 January 1285), commonly called Charles of Anjou, was a member of the royal Capetian dynasty and the founder of the second House of Anjou. He was Count of Provence (1246–85) and Forcalquier (1246–48, 1256–85) ...

and the Duchy of Athens

The Duchy of Athens (Greek: Δουκᾶτον Ἀθηνῶν, ''Doukaton Athinon''; Catalan: ''Ducat d'Atenes'') was one of the Crusader states set up in Greece after the conquest of the Byzantine Empire during the Fourth Crusade as part of th ...

. Michael VIII's attempts to form a union of the Orthodox and Catholic Churches, culminating in the Second Council of Lyon in 1274, were another point of friction. John portrayed himself as a champion of Orthodoxy, offering refuge to pro-Unionists and convoking a synod at his capital Neopatras

Ypati ( el, Υπάτη) is a village and a former municipality in Phthiotis, central peninsular Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality of Lamia, of which it is a municipal unit. The municipal unit has an a ...

in 1276/7 to condemn the Union. Sometime in 1273–75 (the date is disputed by scholars) Michael VIII dispatched a large army against John under his own brother, John Palaiologos. The Byzantine army advanced rapidly through Thessaly and blockaded John with a few of his men at Neopatras, which was placed under siege. John managed to evade the Byzantines and secure aid from Athens, with which he routed the Byzantine army at the Battle of Neopatras

The Battle of Neopatras was fought in the early 1270s between a Byzantine army besieging the city of Neopatras and the forces of John I Doukas, ruler of Thessaly. The battle was a rout for the Byzantine army, which was caught by surprise and def ...

. In exchange for this aid, however, John gave his daughter Helena to the future Duke of Athens William de la Roche (), with the towns of Zetounion, Gardiki, Gravia, and Siderokastron

Siderokastron ( el, Σιδηρόκαστρον) was a medieval fortified settlement on Mount Oeta in Central Greece.

Siderokastron is first mentioned in the 13th century. Some scholars have identified it with a place on Mount Knemis ( Buchon), De ...

as a dowry. In addition, the fleeing Byzantine troops were able to reach Demetrias and help their fleet secure a devastating victory against the Lombard lords of Euboea. A further Byzantine expedition in 1277 against John was equally unsuccessful. Finally, in 1282 Michael VIII in person campaigned against John, but fell ill and died on the way.

Nevertheless, after John's death, his widow was compelled to recognize the suzerainty of Michael VIII's successor, Andronikos II Palaiologos () to safeguard the position of her underage sons Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

and Theodore

Theodore may refer to:

Places

* Theodore, Alabama, United States

* Theodore, Australian Capital Territory

* Theodore, Queensland, a town in the Shire of Banana, Australia

* Theodore, Saskatchewan, Canada

* Theodore Reservoir, a lake in Sask ...

. Thus the Byzantines were allowed passage through Thessaly to invade Epirus in 1290, but soon after the two princes started conspiring with the Serbians of King Milutin Milutin ( sr, Милутин) is a Serbian masculine given name of Slavic origin. The name may refer to:

*Stephen Uroš II Milutin of Serbia

Stefan Uroš II Milutin ( sr-cyr, Стефан Урош II Милутин, Stefan Uroš II Milutin; 125 ...

against Byzantium. In 1295 the brothers invaded Epirus themselves and seized Naupaktos

Nafpaktos ( el, Ναύπακτος) is a town and a former municipality in Aetolia-Acarnania, West Greece, situated on a bay on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth, west of the mouth of the river Mornos.

It is named for Naupaktos (, Latiniz ...

, but no further gains appear to have been made. Both Constantine and Theodore died in 1303, leaving Thessaly to the young son of Constantine, John II Doukas

John II Doukas, also Angelos Doukas ( Latinized as Angelus Ducas) ( gr, Ἰωάννης Ἄγγελος Δούκας, Iōannēs Angelos Doukas), was ruler of Thessaly from 1303 to his death in 1318.

John II Angelos Doukas was the son of Constanti ...

. As he too was underage, Constantine had named the Duke of Athens, Guy II de la Roche

Guy II de la Roche, also known as Guyot or Guidotto (1280 – 5 October 1308), was the Duke of Athens from 1287, the last duke of his family.''The Latins in Greece and the Aegean from the Fourth Crusade to the End of the Middle Ages'', K. M. S ...

(), as his regent and guardian. John II continued his grandfather's pro-Latin policy, maintaining particularly close relations with the Venetians, who imported agricultural produce from Thessaly.

In 1308, Guy II de la Roche died. John II Doukas seized the opportunity to sever his dependency on Athens, and turned to Byzantium for support. In early 1309, the Catalan Company

The Catalan Company or the Great Catalan Company (Spanish: ''Compañía Catalana'', Catalan: ''Gran Companyia Catalana'', Latin: ''Exercitus francorum'', ''Societas exercitus catalanorum'', ''Societas cathalanorum'', ''Magna Societas Catalanorum' ...

, in conflict with the Byzantines, crossed from Macedonia into Thessaly. The arrival of the marauding Company, some 8,000 strong, alarmed John II Doukas. Defeated by the Greeks, the Catalans agreed to pass peacefully through Thessaly to the south, towards the Frankish principalities of southern Greece. After seizing the Spercheios Valley and capturing Salona, the new Duke of Athens, Walter of Brienne, hired the Company for service against Thessaly. Turning back, the Catalans captured Zetounion, Halmyros, Domokos and some thirty other fortresses, and plundered the rich plain of Thessaly, forcing the John Doukas to come to terms with Walter. Walter however tried to backtrack on his deal with the Catalans, leading to open conflict. In the Battle of Halmyros

The Battle of Halmyros, known by earlier scholars as the Battle of the Cephissus or Battle of Orchomenos, was fought on 15 March 1311, between the forces of the Frankish Duchy of Athens and its vassals under Walter of Brienne against the merc ...

on 15 March 1311, the Catalans crushed the Athenian army, killing Walter and most of the leading nobles of Frankish Greece. After the battle, the Catalan Company proceeded to occupy the defenceless duchy.

Thessaly in the 14th and 15th centuries

Loidoriki

Lidoriki ( el, Λιδωρίκι, Katharevousa: Λιδωρίκιον) is a village and a former municipality in Phocis, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Dorida, of which it is the seat and a municipal un ...

, Siderokastron, and Vitrinitsa, as well as—apparently briefly—Domokos, Gardiki, and Pharsalus. This territory formed the new, Catalan-dominated Duchy of Neopatras

The Duchy of Neopatras ( ca, Ducat de Neopàtria; scn, Ducatu di Neopatria; gr, Δουκάτο Νέων Πατρών; la, Ducatus Neopatriae) was a principality in southern Thessaly, established in 1319. Officially part of the Kingdom of Sici ...

. Venice also took advantage of the anarchy in Thessaly to acquire the port of Pteleos

Pteleos ( el, Πτελεός) is a village and a former municipality in the southern part of Magnesia, Thessaly, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part of the municipality of Almyros, of which it is a municipal unit. Th ...

. The central and northern part of Thessaly remained in Greek hands. Lacking a central authority, however, the area fractured among competing rulers. The north came under control of the Byzantines from Thessalonica, while in the centre three rival magnates, Stephen Gabrielopoulos Stephen Gabrielopoulos ( el, Στέφανος Γαβριηλόπουλος, died 1332/1333) was a powerful magnate and semi-independent ruler in western Thessaly, who pledged allegiance to the Byzantine Empire and was rewarded with the title of ''se ...

of Trikala, a certain Signorinos, and the Melissenos, or rather Maliasenos, family in the east around Volos, emerged. Gabrielopoulos was the most successful of the three, and soon managed to gain recognition of his rule by the Byzantine court, which granted him the title of ''sebastokrator

''Sebastokrator'' ( grc-byz, Σεβαστοκράτωρ, Sevastokrátor, August Ruler, ; bg, севастократор, sevastokrator; sh, sebastokrator), was a senior court title in the late Byzantine Empire. It was also used by other rulers wh ...

''. The Maliasenoi on the other hand seem to have turned to the Catalans for support. With the loss of Neopatras and the rise of Gabrielopoulos, Trikala became the new political centre of Thessaly. At about the same time, larger groups of Albanians, such as the tribes of the Malakasioi

The Malakasi were a historical Albanian tribe in medieval Epirus, Thessaly and later southern Greece. Their name is a reference to their area of origin, Mallakastër in southern Albania. They appear in historical records as one of the Albanian t ...

, Bouoi, and Mesaritai, began to raid and settle in Thessaly, although smaller groups of Albanians may have been present in the region already from the late 12th century.

When Gabrielopoulos died in , the Epirote ruler John II Orsini () tried to take advantage of the situation and seize his lands, but the Byzantines under Andronikos III Palaiologos () moved in and established direct control over the northern and western part of the region. Andronikos himself made agreements with the transhumant

Transhumance is a type of pastoralism or nomadism, a seasonal movement of livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and lower val ...

Albanian tribesmen of the Pindus

The Pindus (also Pindos or Pindhos; el, Πίνδος, Píndos; sq, Pindet; rup, Pindu) is a mountain range located in Northern Greece and Southern Albania. It is roughly 160 km (100 miles) long, with a maximum elevation of 2,637 metres ...

mountains and appointed Michael Monomachos

Michael Senachereim Monomachos ( el, Μιχαὴλ Σεναχηρείμ Μονομάχος; ) was a high-ranking Byzantine official, who served as governor of Thessalonica and Thessaly. He reached the high rank of ''megas konostaulos''.

Life

Mic ...

as governor of the region. It is unclear over which parts of Thessaly Byzantine control was restored: John Kantakouzenos

John VI Kantakouzenos or Cantacuzene ( el, , ''Iōánnēs Ángelos Palaiológos Kantakouzēnós''; la, Johannes Cantacuzenus; – 15 June 1383) was a Byzantine Greek nobleman, statesman, and general. He served as grand domestic under And ...

claims that the campaign restored the old Epirote–Thessalian border (i.e. the Pindus mountains), while the modern researcher Božidar Ferjančić

Božidar Ferjančić ( sr-cyr, Божидар Ферјанчић; 17 February 1929 – 28 June 1998) was a Serbian historian, a specialist in medieval Serbian history and the later Byzantine empire. He was member of the Serbian Academy of Scienc ...

suggests that the Byzantines recovered eastern and central Thessaly, but that the western part remained under Epirote rule until Orsini's death three years later, when this area too came under Byzantine control.

The successful Byzantine reconquest was led by Andronikos III's friend and chief aide, John Kantakouzenos. Thus when the Byzantine civil war of 1341–47

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

broke out between Kantakouzenos and the regency for the underage John V Palaiologos

John V Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( el, Ἰωάννης Παλαιολόγος, ''Iōánnēs Palaiológos''; 18 June 1332 – 16 February 1391) was Byzantine emperor from 1341 to 1391, with interruptions.

Biography

John V was the son of E ...

, Thessaly and Epirus quickly rallied to his side. Kantakouzenos' cousin, John Angelos, ruled the two regions until his death in 1348, whereupon they fell to the expanding Serbian Empire

The Serbian Empire ( sr, / , ) was a medieval Serbian state that emerged from the Kingdom of Serbia. It was established in 1346 by Dušan the Mighty, who significantly expanded the state.

Under Dušan's rule, Serbia was the major power in the ...

of Stefan Dushan

Stefan may refer to:

* Stefan (given name)

* Stefan (surname)

* Ștefan, a Romanian given name and a surname

* Štefan, a Slavic given name and surname

* Stefan (footballer) (born 1988), Brazilian footballer

* Stefan Heym, pseudonym of German writ ...

. Dushan appointed his general Gregory Preljub

Preljub ( sr-Cyrl, Прељуб; c. 1312–1356) was a Serbian magnate who served Emperor Stefan Dušan (r. 1331–55) as '' vojvoda'' (general). He participated in the southern conquests and held Thessaly with the rank of ''caesar'' (''kesar'') i ...

as governor of Thessaly, which he ruled, probably from Trikala, until his death in late 1355 or early 1356. In 1350, Kantakouzenos, now emperor, launched an attempt to reconquer Thessaly, but after capturing the towns of Lykostomion and Kastrion, he faltered before Servia, which was defended by Preljub himself. Kantakouzenos withdrew, and Lykostomion and Kastrion were recovered by the Serbs soon after. Preljub's rule is otherwise obscure, except for his reaching an agreement with the local Albanian tribes; an agreement that probably did not last long, for he was killed in a clash with them.

The death of Preljub was preceded by that of Dushan himself, leaving a power vacuum in the wider Serbian Empire and in Thessaly in particular. In this context, Nikephoros Orsini, the exiled son of John II Orsini, who had entered Byzantine service, tried to realize his ancestral claims over the region. From Ainos, he sailed to Thessaly, which he captured quickly, expelling Preljub's wife and son. He then conquered Aetolia

Aetolia ( el, Αἰτωλία, Aἰtōlía) is a mountainous region of Greece on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth, forming the eastern part of the modern regional unit of Aetolia-Acarnania.

Geography

The Achelous River separates Aetolia ...

, Acarnania, and Leukas

Lefkada ( el, Λευκάδα, ''Lefkáda'', ), also known as Lefkas or Leukas (Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: Λευκάς, ''Leukás'', modern pronunciation ''Lefkás'') and Leucadia, is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea on the west coast of Gr ...

. Catalan control over southern Thessaly had ceased by this time. Nikephoros came into conflict with the Albanians, however, and was killed in the Battle of Achelous in 1359. Following Nikephoros' death, Thessaly was taken over without resistance by Dushan's half-brother Simeon Uroš

Simeon Uroš ( sr-cyr, Симеон Урош, gr, Συμεών Ούρεσης; 1326–1370), nicknamed Siniša (Синиша), was a self-proclaimed Emperor of Serbs and Greeks, from 1356 to 1370. He was son of Serbian King Stephen Uroš III a ...

. Enjoying the support of the local Greek and Serbian nobility, Simeon Uroš reigned as self-proclaimed emperor from Trikala until his death in 1370. He was particularly noted as a patron of the Meteora

The Meteora (; el, Μετέωρα, ) is a rock formation in central Greece hosting one of the largest and most precipitously built complexes of Eastern Orthodox monasteries, second in importance only to Mount Athos.Sofianos, D.Z.: "Metéora" ...

monasteries, who regarded him as their "second founder". His son John Uroš

Jovan Uroš Nemanjić ( sr, Јован Урош Немањић / ''Jovan Uroš Nemanjić'') or John Ouresis Doukas Palaiologos or Joasaph of Meteora ( gr, Ιωάννης Ούρεσης Δούκας Παλαιολόγος, ''Iōannēs Ouresēs Doú ...

succeeded him until 1373, when he retired to a monastery; Thessaly was then ruled by Alexios Angelos Philanthropenos Alexios Angelos Philanthropenos ( el, ) was a Byzantine Greek nobleman who ruled Thessaly from 1373 until c. 1390 (from c. 1382 as a Byzantine vassal) with the title of ''Caesar''.

Biography

The Angeloi of Thessaly rose to prominence during the r ...

and (from ) Manuel Angelos Philanthropenos Manuel Angelos Philanthropenos ( el, ) was a Byzantine Greek nobleman who ruled Thessaly from c. 1390 until it was conquered by the Ottoman Turks in 1393, as a Byzantine vassal with the title of ''Caesar''.

Biography

Manuel was either the son or t ...

, who recognized Byzantine suzerainty until , when the region was conquered by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. In the south, the Florentine adventurer Nerio Acciaioli had managed to take over the Duchy of Athens from the Catalans, and in 1390 captured Neopatras as well. These territories were soon lost to the Ottoman Turks, at about the same time as the fall of Thessaly.

Ottoman period

The Ottomans first invaded Thessaly in 1386, when

The Ottomans first invaded Thessaly in 1386, when Gazi Evrenos

Evrenos or Evrenuz (died 17 November 1417 in Yenice-i Vardar) was an Ottoman military commander. Byzantine sources mention him as Ἐβρενός, Ἀβρανέζης, Βρανέζης, Βρανεύς (?), Βρενέζ, Βρενέζης, Βρε ...

took Larissa for a time, confining the Angeloi Philanthropenoi to their holdings in western Thessaly, around Trikala. In ca. 1393, the second phase of the invasion began, again under Evrenos. The Ottomans defeated Manuel Angelos Philanthropenos, and retook Larissa. The conquest of Thessaly was completed during the next few years, from 1394 under the personal supervision of Sultan Bayezid I

Bayezid I ( ota, بايزيد اول, tr, I. Bayezid), also known as Bayezid the Thunderbolt ( ota, link=no, یلدیرم بايزيد, tr, Yıldırım Bayezid, link=no; – 8 March 1403) was the Ottoman Sultan from 1389 to 1402. He adopted ...

. The fortresses of Volos, Pharsalus, Domokos and Neopatras were taken, and in 1395/6, Trikala too fell.

After the disastrous Battle of Ankara

The Battle of Ankara or Angora was fought on 20 July 1402 at the Çubuk plain near Ankara, between the forces of the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I and the Emir of the Timurid Empire, Timur. The battle was a major victory for Timur, and it led to the ...

in 1402, the weakened Ottomans were forced to return the eastern coasts of Thessaly and the region of Zetounion to Byzantine rule. In 1423, however, the renewed Ottoman pressure forced the local Byzantine commander to surrender the forts of Stylida

Stylida ( el, Στυλίδα; older Στυλίς, Stylis) is a town and a municipality in Phthiotis, Greece. The population of the municipal unit was 6,126 (2011).

History

First mention of the town of Stylida was during ancient times when the tow ...

and Avlaki to the Venetians. By 1444, however, the entire region had been finally conquered by the Turks. Pteleos alone remained in Venetian hands until 1470.

The newly conquered region was initially the patrimonial domain of the powerful marcher-lord Turahan Bey

Turahan Bey or Turakhan Beg ( tr, Turahan Bey/Beğ; sq, Turhan Bej; el, Τουραχάνης, Τουραχάν μπέης or Τουραχάμπεης;PLP 29165 died in 1456) was a prominent Ottoman military commander and governor of Thessaly ...

(died 1456) and of his son Ömer Bey (died 1484) rather than a regular province. Turahan and his heirs brought in settlers from Anatolia (the so-called "Konyalis" or "Koniarides" since most were from the region around Konya

Konya () is a major city in central Turkey, on the southwestern edge of the Central Anatolian Plateau, and is the capital of Konya Province. During antiquity and into Seljuk times it was known as Iconium (), although the Seljuks also called it ...

) to repopulate the sparsely inhabited area, and soon, Muslim settlers or converts dominated the lowlands, while the Christians held the mountains around the Thessalian plain. The area was generally peaceful, but banditry was endemic, and led to the creation of the first state-sanctioned Christian autonomies known as ''armatolik

The armatoles ( el, αρματολοί, armatoloi; sq, armatolë; rup, armatoli; bs, armatoli), or armatole in singular ( el, αρματολός, armatolos; sq, armatol; rup, armatol; bs, armatola), were Christian irregular soldiers, or mil ...

s'', the earliest and most notable of which was that of Agrafa

Agrafa ( el, Άγραφα, ) is a mountainous region in Evrytania and Karditsa regional units in mainland Greece, consisting mainly of small villages. It is the southernmost part of the Pindus range. There is also a municipality with the same n ...

. Failed Greek uprisings occurred in 1600/1 and 1612, and during the Morean War

The Morean War ( it, Guerra di Morea), also known as the Sixth Ottoman–Venetian War, was fought between 1684–1699 as part of the wider conflict known as the " Great Turkish War", between the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire. Military ...

and the Orlov Revolt.

After 1780, the ambitious Ali Pasha of Ioannina took over control of Thessaly, and consolidated his rule after 1808, when he suppressed a local uprising. His heavy taxation, however, ruined the province's commerce, and coupled with the outbreak of the plague in 1813, reduced the population to some 200,000 by 1820. When the Greek War of Independence broke out in 1821, Greek risings occurred in the Pelion

Pelion or Pelium (Modern el, Πήλιο, ''Pílio''; Ancient Greek/ Katharevousa: Πήλιον, ''Pēlion'') is a mountain at the southeastern part of Thessaly in northern Greece, forming a hook-like peninsula between the Pagasetic Gulf and the ...

and Olympus mountains as well as the western mountains around Fanari, but they were swiftly suppressed by the Ottoman armies under Mehmed Reshid Pasha and Mahmud Dramali Pasha

Dramalı Mahmud Pasha, ( Turkish: ''Dramalı Mahmut Paşa''; c. 1770 in Istanbul – 26 October 1822, in Corinth) was an Ottoman

Albanian statesman and military leader, and a pasha, and served as governor (''wali'') of Larissa, Drama, and the M ...

. After the establishment of the independent Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece ( grc, label= Greek, Βασίλειον τῆς Ἑλλάδος ) was established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally recognised by the Treaty of Constantinople, wh ...

, Greek nationalist agitation continued, with further revolts in 1841, 1854 and again during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. Thessaly remained in Ottoman hands until 1881, when it was handed over to Greece under the terms of the Convention of Constantinople

The Convention of Constantinople is a treaty concerning the use of the Suez Canal in Egypt. It was signed on 29 October 1888 by the United Kingdom, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands, the Russian Empire, and the Ott ...

.

Modern era

After union with Greece, Thessaly became divided into fourprefectures

A prefecture (from the Latin ''Praefectura'') is an administrative jurisdiction traditionally governed by an appointed prefect. This can be a regional or local government subdivision in various countries, or a subdivision in certain international ...

: Larissa Prefecture, Magnesia Prefecture

Magnesia Prefecture ( el, Νομός Μαγνησίας) was one of the prefectures of Greece. Its capital was Volos. It was established in 1899 from the Larissa Prefecture. The prefecture was disbanded on 1 January 2011 by the Kallikratis progra ...

, Karditsa Prefecture, and Trikala Prefecture

Trikala ( el, Περιφερειακή ενότητα Τρικάλων) is one of the regional units of Greece, forming the northwestern part of the region of Thessaly. Its capital is the town of Trikala. The regional unit includes the town of Kal ...

. In 1897, the region was overrun by the Ottomans during the brief Greco-Turkish War of 1897

The Greco-Turkish War of 1897 or the Ottoman-Greek War of 1897 ( or ), also called the Thirty Days' War and known in Greece as the Black '97 (, ''Mauro '97'') or the Unfortunate War ( el, Ατυχής πόλεμος, Atychis polemos), was a w ...

. The Ottoman army withdrew after the war's end, but minor territorial adjustments were made to the frontier in the Ottomans' favour. The early decades of Greek rule in Thessaly were dominated by the agricultural issue, as the area retained its Ottoman-era large landholdings (chiflik

Chiflik, or chiftlik (Ottoman Turkish: ; al, çiflig; bg, чифлик, ''chiflik''; mk, чифлиг, ''čiflig''; el, τσιφλίκι, ''tsiflíki''; sr, читлук/''čitluk''), is a Turkish term for a system of land management in th ...