Medieval Scotland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Scotland in the Middle Ages concerns the

In the centuries after the departure of the Romans from Britain, four major circles of influence emerged within the borders of what is now Scotland. In the east were the

In the centuries after the departure of the Romans from Britain, four major circles of influence emerged within the borders of what is now Scotland. In the east were the

This situation was transformed in AD 793 when ferocious Viking raids began on monasteries like Iona and Lindisfarne, creating fear and confusion across the kingdoms of North Britain.

This situation was transformed in AD 793 when ferocious Viking raids began on monasteries like Iona and Lindisfarne, creating fear and confusion across the kingdoms of North Britain.

The long reign (900–942/3) of Causantín (Constantine II) is often regarded as the key to formation of the Kingdom of Alba. He was later credited with bringing Scottish Christianity into conformity with the Catholic Church. After fighting many battles, his defeat at

The long reign (900–942/3) of Causantín (Constantine II) is often regarded as the key to formation of the Kingdom of Alba. He was later credited with bringing Scottish Christianity into conformity with the Catholic Church. After fighting many battles, his defeat at

When Alexander died in 1124, the crown passed to Margaret's fourth son

When Alexander died in 1124, the crown passed to Margaret's fourth son

The death of King Alexander III in 1286, and then of his granddaughter and heir Margaret, Maid of Norway in 1290, left 14 rivals for succession. To prevent civil war the Scottish magnates asked

The death of King Alexander III in 1286, and then of his granddaughter and heir Margaret, Maid of Norway in 1290, left 14 rivals for succession. To prevent civil war the Scottish magnates asked

After David II's death, Robert II, the first of the Stewart kings, came to the throne in 1371. He was followed in 1390 by his ailing son John, who took the

After David II's death, Robert II, the first of the Stewart kings, came to the throne in 1371. He was followed in 1390 by his ailing son John, who took the

Kingship was the major form of political organisation in the Early Middle Ages, with competing minor kingdoms and fluid relationships of over and under kingdoms.B. Yorke, "Kings and kingship", in P. Stafford, ed., ''A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500-c.1100'' (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), , pp. 76–90. The primary function of these kings was as war leaders, but there were also ritual elements to kingship, evident in ceremonies of coronation. The unification of the Scots and Picts from the tenth century that produced the Kingdom of Alba, retained some of these ritual aspects in the coronation at

Kingship was the major form of political organisation in the Early Middle Ages, with competing minor kingdoms and fluid relationships of over and under kingdoms.B. Yorke, "Kings and kingship", in P. Stafford, ed., ''A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500-c.1100'' (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), , pp. 76–90. The primary function of these kings was as war leaders, but there were also ritual elements to kingship, evident in ceremonies of coronation. The unification of the Scots and Picts from the tenth century that produced the Kingdom of Alba, retained some of these ritual aspects in the coronation at

In the Early Middle Ages, war on land was characterised by the use of small war-bands of household troops often engaging in raids and low level warfare.L. Alcock, ''Kings and Warriors, Craftsmen and Priests in Northern Britain AD 550–850'' (Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland), , pp. 248–9. The arrival of the Vikings brought a new scale of naval warfare, with rapid movement based around the Viking longship. The

In the Early Middle Ages, war on land was characterised by the use of small war-bands of household troops often engaging in raids and low level warfare.L. Alcock, ''Kings and Warriors, Craftsmen and Priests in Northern Britain AD 550–850'' (Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland), , pp. 248–9. The arrival of the Vikings brought a new scale of naval warfare, with rapid movement based around the Viking longship. The

Christianity was probably introduced to what is now lowland Scotland from Roman soldiers stationed in the north of the province of

Christianity was probably introduced to what is now lowland Scotland from Roman soldiers stationed in the north of the province of

Modern Scotland is half the size England and Wales in area, but with its many inlets, islands and inland

Modern Scotland is half the size England and Wales in area, but with its many inlets, islands and inland

Having between a fifth or sixth (15-20%) of the arable or good pastoral land and roughly the same amount of coastline as England and Wales, marginal pastoral agriculture and fishing were two of the most important aspects of the Medieval Scottish economy.E. Gemmill and N. J. Mayhew, ''Changing Values in Medieval Scotland: a Study of Prices, Money, and Weights and Measures'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), , pp. 8–10. With poor communications, in the Early Middle Ages most settlements needed to achieve a degree of self-sufficiency in agriculture.A. Woolf, ''From Pictland to Alba: 789 – 1070'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 17–20. Most farms were based around a family unit and used an infield and outfield system. Arable farming grew in the High Middle Ages and agriculture entered a period of relative boom between the thirteenth century and late fifteenth century.S. H. Rigby, ed., ''A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages'' (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), , pp. 111–6.

Unlike England, Scotland had no towns dating from Roman occupation. From the twelfth century there are records of burghs, chartered towns, which became major centres of crafts and trade. and there is evidence of 55 burghs by 1296.B. Webster, ''Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity'' (St. Martin's Press, 1997), , pp. 122–3. There are also Scottish coins, although English coinage probably remained more significant in trade and until the end of the period barter was probably the most common form of exchange.A. MacQuarrie, ''Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation'' (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), , pp. 136–40.K. J. Stringer, "The Emergence of a Nation-State, 1100–1300", in J. Wormald, ed., ''Scotland: A History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), , pp. 38–76. Nevertheless, craft and industry remained relatively undeveloped before the end of the Middle AgesJ. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 41–55. and, although there were extensive trading networks based in Scotland, while the Scots exported largely raw materials, they imported increasing quantities of luxury goods, resulting in a bullion shortage and perhaps helping to create a financial crisis in the fifteenth century.

Having between a fifth or sixth (15-20%) of the arable or good pastoral land and roughly the same amount of coastline as England and Wales, marginal pastoral agriculture and fishing were two of the most important aspects of the Medieval Scottish economy.E. Gemmill and N. J. Mayhew, ''Changing Values in Medieval Scotland: a Study of Prices, Money, and Weights and Measures'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), , pp. 8–10. With poor communications, in the Early Middle Ages most settlements needed to achieve a degree of self-sufficiency in agriculture.A. Woolf, ''From Pictland to Alba: 789 – 1070'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 17–20. Most farms were based around a family unit and used an infield and outfield system. Arable farming grew in the High Middle Ages and agriculture entered a period of relative boom between the thirteenth century and late fifteenth century.S. H. Rigby, ed., ''A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages'' (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), , pp. 111–6.

Unlike England, Scotland had no towns dating from Roman occupation. From the twelfth century there are records of burghs, chartered towns, which became major centres of crafts and trade. and there is evidence of 55 burghs by 1296.B. Webster, ''Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity'' (St. Martin's Press, 1997), , pp. 122–3. There are also Scottish coins, although English coinage probably remained more significant in trade and until the end of the period barter was probably the most common form of exchange.A. MacQuarrie, ''Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation'' (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), , pp. 136–40.K. J. Stringer, "The Emergence of a Nation-State, 1100–1300", in J. Wormald, ed., ''Scotland: A History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), , pp. 38–76. Nevertheless, craft and industry remained relatively undeveloped before the end of the Middle AgesJ. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 41–55. and, although there were extensive trading networks based in Scotland, while the Scots exported largely raw materials, they imported increasing quantities of luxury goods, resulting in a bullion shortage and perhaps helping to create a financial crisis in the fifteenth century.

The organisation of society is obscure in the early part of the period, for which there are few documentary sources.D. E. Thornton, "Communities and kinship", in P. Stafford, ed., ''A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500-c.1100'' (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), , pp. 98. Kinship probably provided the primary unit of organisation and society was divided between a small

The organisation of society is obscure in the early part of the period, for which there are few documentary sources.D. E. Thornton, "Communities and kinship", in P. Stafford, ed., ''A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500-c.1100'' (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), , pp. 98. Kinship probably provided the primary unit of organisation and society was divided between a small

Modern linguists divide Celtic languages into two major groups, the

Modern linguists divide Celtic languages into two major groups, the

''Scotland's Books: A History of Scottish Literature''

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), . In the late Middle Ages,

The establishment of Christianity brought Latin to Scotland as a scholarly and written language. Monasteries served as major repositories of knowledge and education, often running schools and providing a small educated elite, who were essential to create and read documents in a largely illiterate society.A. Macquarrie, ''Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation'' (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), , p. 128. In the High Middle Ages new sources of education arose, with

The establishment of Christianity brought Latin to Scotland as a scholarly and written language. Monasteries served as major repositories of knowledge and education, often running schools and providing a small educated elite, who were essential to create and read documents in a largely illiterate society.A. Macquarrie, ''Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation'' (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), , p. 128. In the High Middle Ages new sources of education arose, with

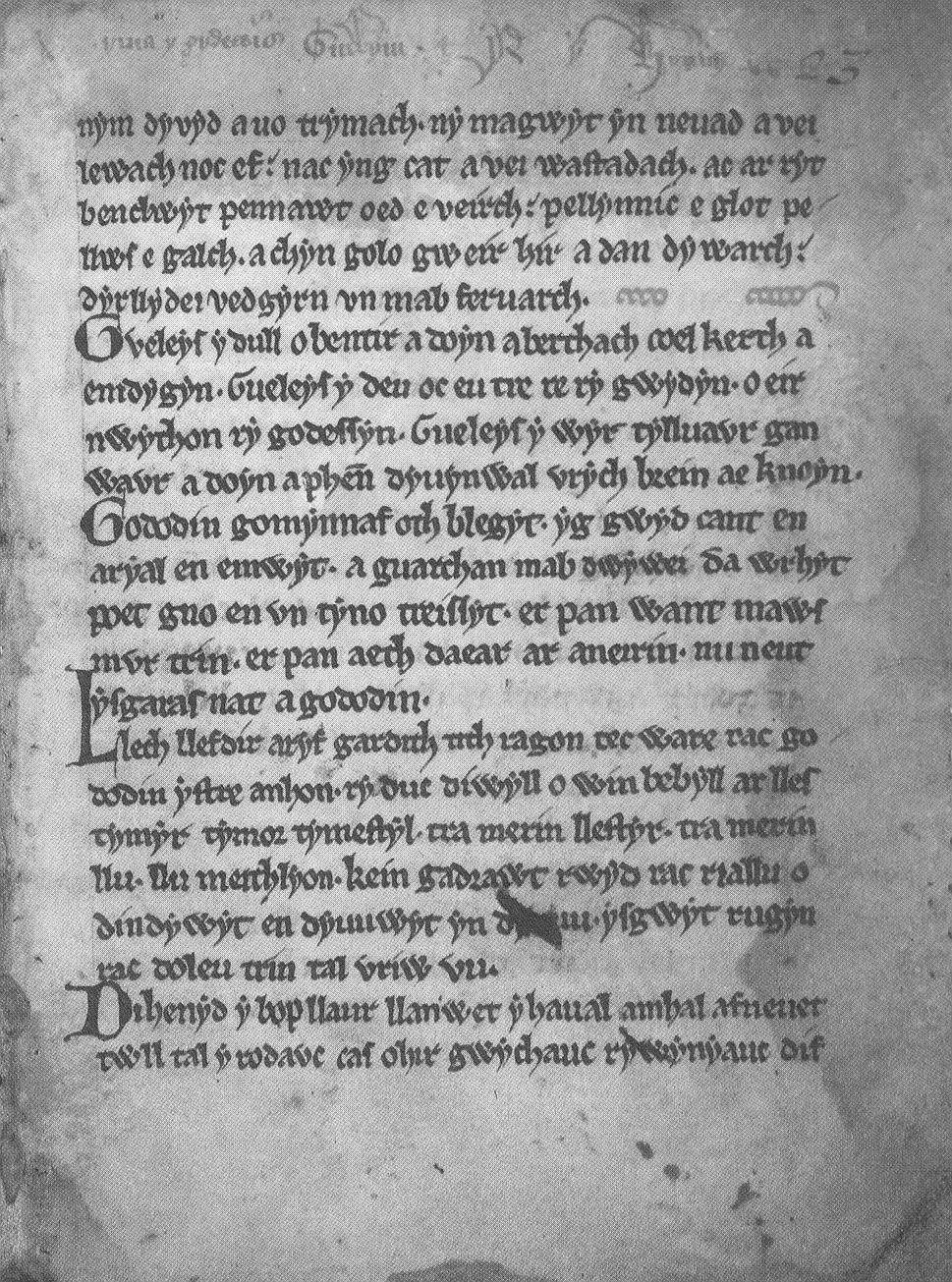

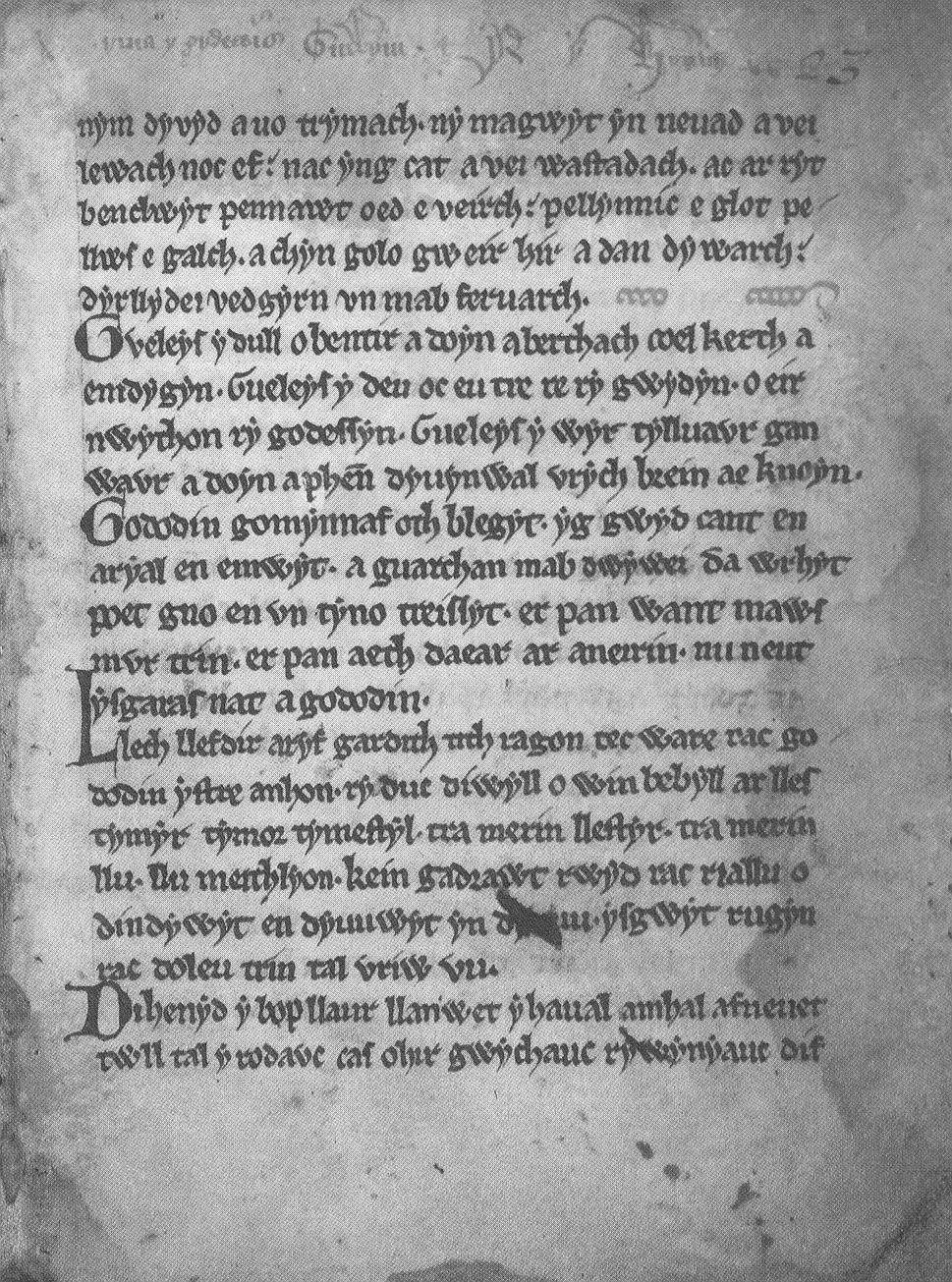

Much of the earliest Welsh literature was actually composed in or near the country now called Scotland, in the Brythonic speech, from which

Much of the earliest Welsh literature was actually composed in or near the country now called Scotland, in the Brythonic speech, from which

In the early middles ages, there were distinct material cultures evident in the different linguistic groups, federations and kingdoms within what is now Scotland. Pictish art can be seen in the extensive survival of carved stones, particularly in the north and east of the country, which hold a variety of recurring images and patterns, as at Dunrobin (

In the early middles ages, there were distinct material cultures evident in the different linguistic groups, federations and kingdoms within what is now Scotland. Pictish art can be seen in the extensive survival of carved stones, particularly in the north and east of the country, which hold a variety of recurring images and patterns, as at Dunrobin (

"Citadel of the first Scots"

''British Archaeology'', 62, December 2001. Retrieved 2 December 2010. Insular art is the name given to the common style that developed in Britain and Ireland after the conversion of the Picts and the cultural assimilation of Pictish culture into that of the Scots and Angles, and which became highly influential in continental Europe, contributing to the development of Romanesque and

Medieval

Medieval

In the late twelfth century,

In the late twelfth century,

In the High Middle Ages the word "Scot" was only used by Scots to describe themselves to foreigners, amongst whom it was the most common word. They called themselves ''Albanach'' or simply ''Gaidel''. Both "Scot" and ''Gaidel'' were ethnic terms that connected them to the majority of the inhabitants of Ireland. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the author of '' De Situ Albanie'' noted that: "The name Arregathel rgyllmeans margin of the Scots or Irish, because all Scots and Irish are generally called 'Gattheli'." Scotland came to possess a unity which transcended Gaelic, French and Germanic ethnic differences and by the end of the period, the Latin, French and English word "Scot" could be used for any subject of the Scottish king. Scotland's multilingual

In the High Middle Ages the word "Scot" was only used by Scots to describe themselves to foreigners, amongst whom it was the most common word. They called themselves ''Albanach'' or simply ''Gaidel''. Both "Scot" and ''Gaidel'' were ethnic terms that connected them to the majority of the inhabitants of Ireland. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the author of '' De Situ Albanie'' noted that: "The name Arregathel rgyllmeans margin of the Scots or Irish, because all Scots and Irish are generally called 'Gattheli'." Scotland came to possess a unity which transcended Gaelic, French and Germanic ethnic differences and by the end of the period, the Latin, French and English word "Scot" could be used for any subject of the Scottish king. Scotland's multilingual  The adoption of Middle Scots by the aristocracy has been seen as building a shared sense of national solidarity and culture between rulers and ruled, although the fact that north of the Tay Gaelic still dominated may have helped widen the cultural divide between highlands and lowlands. The national literature of Scotland created in the late medieval period employed legend and history in the service of the crown and nationalism, helping to foster a sense of national identity, at least within its elite audience. The epic poetic history of the ''Brus'' and ''Wallace'' helped outline a narrative of united struggle against the English enemy. Arthurian literature differed from conventional versions of the legend by treating

The adoption of Middle Scots by the aristocracy has been seen as building a shared sense of national solidarity and culture between rulers and ruled, although the fact that north of the Tay Gaelic still dominated may have helped widen the cultural divide between highlands and lowlands. The national literature of Scotland created in the late medieval period employed legend and history in the service of the crown and nationalism, helping to foster a sense of national identity, at least within its elite audience. The epic poetic history of the ''Brus'' and ''Wallace'' helped outline a narrative of united struggle against the English enemy. Arthurian literature differed from conventional versions of the legend by treating

, ''The National Archives of Scotland'', 28 November 2007, retrieved 12 September 2009. Use of a simplified symbol associated with Saint Andrew, the

www.flaginstitute.org ''British Flags & Emblems''

(Edinburgh: Tuckwell Press, 2004), , p. 10. The earliest reference to the Saint Andrew's Cross as a flag is to be found in the ''Vienna Book of Hours'', circa 1503.G. Bartram

''The Story of Scotland's Flags: Proceedings of the XIX International Congress of Vexillology''

(York: Fédération internationale des associations vexillologiques, 2001), retrieved 12 September 2009.

history of Scotland

The recorded begins with the arrival of the Roman Empire in the 1st century, when the province of Britannia reached as far north as the Antonine Wall. North of this was Caledonia, inhabited by the ''Picti'', whose uprisings forced Rome ...

from the departure of the Romans to the adoption of major aspects of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

in the early sixteenth century.

From the fifth century northern Britain was divided into a series of kingdoms. Of these the four most important to emerge were the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from ea ...

, the Gaels of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaelic kingdom that encompassed the western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel. At its height in the 6th and 7th centuries, it covered what is n ...

, the Britons of Strathclyde

Strathclyde ( in Gaelic, meaning "strath (valley) of the River Clyde") was one of nine former local government regions of Scotland created in 1975 by the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 and abolished in 1996 by the Local Government et ...

and the Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened wit ...

kingdom of Bernicia

Bernicia ( ang, Bernice, Bryneich, Beornice; la, Bernicia) was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England.

The Anglian territory of Bernicia was ap ...

, later taken over by Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

. After the arrival of the Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

in the late eighth century, Scandinavian rulers and colonies were established along parts of the coasts and in the islands.

In the ninth century the Scots and Picts combined under the House of Alpin

The House of Alpin, also known as the Alpínid dynasty, Clann Chináeda, and Clann Chinaeda meic Ailpín, was the kin-group which ruled in Pictland, possibly Dál Riata, and then the kingdom of Alba from the advent of Kenneth MacAlpin (Cináed ...

to form a single Kingdom of Alba

The Kingdom of Alba ( la, Scotia; sga, Alba) was the Kingdom of Scotland between the deaths of Donald II in 900 and of Alexander III in 1286. The latter's death led indirectly to an invasion of Scotland by Edward I of England in 1296 and the ...

, with a Pictish base and dominated by Gaelic culture

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Goidelic languages, Gaelic languages: a branch o ...

. After the reign of King David I

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim (Modern: ''Daibhidh I mac haoilChaluim''; – 24 May 1153) was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians from 1113 to 1124 and later King of Scotland from 1124 to 1153. The youngest son of Malcol ...

in the twelfth century, the Scottish monarchs

The monarch of Scotland was the head of state of the Kingdom of Scotland. According to tradition, the first King of Scots was Kenneth I MacAlpin (), who founded the state in 843. Historically, the Kingdom of Scotland is thought to have grown ...

are best described as Scoto-Norman

The term Scoto-Norman (also Franco-Scottish or Franco-Gaelic) is used to describe people, families, institutions and archaeological artifacts that are partly Scottish people, Scottish (in some sense) and partly Anglo-Normans, Anglo-Norman (in some ...

, preferring French culture

The culture of France has been shaped by geography, by historical events, and by foreign and internal forces and groups. France, and in particular Paris, has played an important role as a center of high culture since the 17th century and from ...

to native Scottish culture

The culture of Scotland refers to the patterns of human activity and symbolism associated with Scotland and the Scottish people. The Scottish flag is blue with a white saltire, and represents the cross of Saint Andrew.

Scots law

Scotland retain ...

. Alexander II and his son Alexander III, were able to regain the remainder of the western seaboard, cumulating the Treaty of Perth

The Treaty of Perth, signed 2 July 1266, ended military conflict between Magnus VI of Norway and Alexander III of Scotland over possession of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man. The text of the treaty.

The Hebrides and the Isle of Man had becom ...

with Norway in 1266.

After being invaded and briefly occupied, Scotland re-established its independence from England under figures including William Wallace

Sir William Wallace ( gd, Uilleam Uallas, ; Norman French: ; 23 August 1305) was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

Along with Andrew Moray, Wallace defeated an English army ...

in the late thirteenth century and Robert Bruce in the fourteenth century.

In the fifteenth century under the Stewart Dynasty, despite a turbulent political history

Political history is the narrative and survey of political events, ideas, movements, organs of government, voters, parties and leaders. It is closely related to other fields of history, including diplomatic history, constitutional history, social ...

, the crown gained greater political control at the expense of independent lords and regained most of its lost territory to approximately the modern borders of the country. However, the Auld Alliance

The Auld Alliance ( Scots for "Old Alliance"; ; ) is an alliance made in 1295 between the kingdoms of Scotland and France against England. The Scots word ''auld'', meaning ''old'', has become a partly affectionate term for the long-lasting a ...

with France led to the heavy defeat of a Scottish army at the Battle of Flodden

The Battle of Flodden, Flodden Field, or occasionally Branxton, (Brainston Moor) was a battle fought on 9 September 1513 during the War of the League of Cambrai between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland, resulting in an English ...

in 1513 and the death of the king James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

, which would be followed by a long minority and a period of political instability. Kingship was the major form of government, growing in sophistication in the late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Ren ...

. The scale and nature of war also changed, with larger armies, naval forces and the development of artillery and fortifications.

The Church in Scotland always accepted papal authority (contrary to the implications of Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity ( kw, Kristoneth; cy, Cristnogaeth; gd, Crìosdaidheachd; gv, Credjue Creestee/Creestiaght; ga, Críostaíocht/Críostúlacht; br, Kristeniezh; gl, Cristianismo celta) is a form of Christianity that was common, or held ...

), introduced monasticism, and from the eleventh century embraced monastic reform, developing a flourishing religious culture that asserted its independence from English control.

Scotland grew from its base in the eastern Lowlands

Upland and lowland are conditional descriptions of a plain based on elevation above sea level. In studies of the ecology of freshwater rivers, habitats are classified as upland or lowland.

Definitions

Upland and lowland are portions of p ...

, to approximately its modern borders. The varied and dramatic geography of the land provided a protection against invasion, but limited central control. It also defined the largely pastoral economy, with the first burgh

A burgh is an autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland and Northern England, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when King David I created the first royal burghs. Bur ...

s being created from the twelfth century. The population may have grown to a peak of a million before the arrival of the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

in 1350. In the early Middle Ages society was divided between a small aristocracy and larger numbers of freemen and slaves. Serfdom disappeared in the fourteenth century and there was a growth of new social groups.

The Pictish

Pictish is the extinct Brittonic language spoken by the Picts, the people of eastern and northern Scotland from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. Virtually no direct attestations of Pictish remain, short of a limited number of geographica ...

and Cumbric

Cumbric was a variety of the Common Brittonic language spoken during the Early Middle Ages in the '' Hen Ogledd'' or "Old North" in what is now the counties of Westmorland, Cumberland and northern Lancashire in Northern England and the south ...

languages were replaced by Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, an ...

, Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

and later Norse, with Gaelic emerging as the major cultural language. From the eleventh century French was adopted in the court and in the late Middle Ages, Scots, derived from Old English, became dominant, with Gaelic largely confined to the Highlands. Christianity brought Latin, written culture and monasteries as centres of learning. From the twelfth century, educational opportunities widened and a growth of lay education cumulated in the Education Act 1496

The Education Act 1496 was an act of the Parliament of Scotland (1496 c. 87) that required landowners to send their eldest sons to school to study Latin, arts and law. This made schooling compulsory for the first time in the world.

The humanis ...

. Until in the fifteenth century, when Scotland gained three universities, Scots pursuing higher education had to travel to England or the continent, where some gained an international reputation. Literature survives in all the major languages present in the early Middle Ages, with Scots emerging as a major literary language from John Barbour John Barbour may refer to:

* John Barbour (poet) (1316–1395), Scottish poet

* John Barbour (MP for New Shoreham), MP for New Shoreham 1368-1382

* John Barbour (footballer) (1890–1916), Scottish footballer

* John S. Barbour (1790–1855), U. ...

's '' Brus'' (1375), developing a culture of poetry by court makars, and later major works of prose. Art from the early Middle Ages survives in carving, in metalwork, and elaborate illuminated books, which contributed to the development of the wider insular style. Much of the finest later work has not survived, but there are a few key examples, particularly of work commissioned in the Netherlands. Scotland had a musical tradition, with secular music composed and performed by bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise ...

s and from the thirteenth century, church music increasingly influenced by continental and English forms.

Political history

Early Middle Ages

Minor kingdoms

In the centuries after the departure of the Romans from Britain, four major circles of influence emerged within the borders of what is now Scotland. In the east were the

In the centuries after the departure of the Romans from Britain, four major circles of influence emerged within the borders of what is now Scotland. In the east were the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from ea ...

, whose kingdoms eventually stretched from the river Forth to Shetland. The first identifiable king to have exerted a superior and wide-ranging authority, was Bridei mac Maelchon (r. c. 550–84), whose power was based in the Kingdom of Fidach and his base was at the fort of Craig Phadrig near modern Inverness

Inverness (; from the gd, Inbhir Nis , meaning "Mouth of the River Ness"; sco, Innerness) is a city in the Scottish Highlands. It is the administrative centre for The Highland Council and is regarded as the capital of the Highlands. Histor ...

.J. Haywood, ''The Celts: Bronze Age to New Age'' (London: Pearson Education, 2004), , p. 116. After his death leadership seems to have shifted to the Fortriu

Fortriu ( la, Verturiones; sga, *Foirtrinn; ang, Wærteras; xpi, *Uerteru) was a Pictish kingdom that existed between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but ...

, whose lands were centred on Strathearn

Strathearn or Strath Earn (, from gd, Srath Èireann) is the strath of the River Earn, in Scotland, extending from Loch Earn in the West to the River Tay in the east.http://www.strathearn.com/st_where.htm Derivation of name Strathearn was on ...

and Menteith

Menteith or Monteith ( gd, Mòine Tèadhaich), a district of south Perthshire, Scotland, roughly comprises the territory between the Teith and the Forth. Earlier forms of its name include ''Meneted'', ''Maneteth'' and ''Meneteth''. (Historically ...

and who raided along the eastern coast into modern England. Christian missionaries from Iona

Iona (; gd, Ì Chaluim Chille (IPA: �iːˈxaɫ̪ɯimˈçiʎə, sometimes simply ''Ì''; sco, Iona) is a small island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though ther ...

appear to have begun the conversion of the Picts to Christianity from 563.

In the west were the Gaelic (Goidelic

The Goidelic or Gaelic languages ( ga, teangacha Gaelacha; gd, cànanan Goidhealach; gv, çhengaghyn Gaelgagh) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historical ...

)-speaking people of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaelic kingdom that encompassed the western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel. At its height in the 6th and 7th centuries, it covered what is n ...

with their royal fortress at Dunadd

Dunadd (Scottish Gaelic ''Dún Ad'', "fort on the iverAdd") is a hillfort in Argyll and Bute, Scotland, dating from the Iron Age and early medieval period and is believed to be the capital of the ancient kingdom of Dál Riata. Dal Riata was a ki ...

in Argyll, with close links with the island of Ireland, from which they brought with them the name Scots. In 563 a mission from Ireland under St. Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is tod ...

founded the monastery of Iona

Iona (; gd, Ì Chaluim Chille (IPA: �iːˈxaɫ̪ɯimˈçiʎə, sometimes simply ''Ì''; sco, Iona) is a small island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though ther ...

off the west coast of Scotland and probably began the conversion of the region to Christianity.A. P. Smyth, ''Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), , pp. 43–6. The kingdom reached its height under Áedán mac Gabráin

Áedán mac Gabráin (pronounced in Old Irish; ga, Aodhán mac Gabhráin, lang), also written as Aedan, was a king of Dál Riata from 574 until c. 609 AD. The kingdom of Dál Riata was situated in modern Argyll and Bute, Scotland, and pa ...

(r. 574–608), but its expansion was checked at the Battle of Degsastan

The Battle of Degsastan was fought around 603 between king Æthelfrith of Bernicia and the Gaels under Áedán mac Gabráin, king of Dál Riada. Æthelfrith's smaller army won a decisive victory, although his brother Theodbald was killed. Very ...

in 603 by Æthelfrith of Northumbria

Æthelfrith (died c. 616) was King of Bernicia from c. 593 until his death. Around 604 he became the first Bernician king to also rule the neighboring land of Deira, giving him an important place in the development of the later kingdom of Nort ...

.

In the south was the British (Brythonic

Brittonic or Brythonic may refer to:

*Common Brittonic, or Brythonic, the Celtic language anciently spoken in Great Britain

*Brittonic languages, a branch of the Celtic languages descended from Common Brittonic

*Britons (Celtic people)

The Br ...

) Kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde (lit. " Strath of the River Clyde", and Strað-Clota in Old English), was a Brittonic successor state of the Roman Empire and one of the early medieval kingdoms of the Britons, located in the region the Welsh tribes referred to as ...

, descendants of the peoples of the Roman influenced kingdoms of " The Old North", often named Alt Clut, the Brythonic name for their capital at Dumbarton Rock. In 642, they defeated the men of Dál Riata, but the kingdom suffered a number of attacks from the Picts, and later their Northumbrian allies, between 744 and 756. After this, little is recorded until Alt Clut was burnt and probably destroyed in 780, although by whom and what in what circumstances is not known.

Finally, there were the English or "Angles", Germanic invaders who had conquered much of southern Britain and held the Kingdom of Bernicia

Bernicia ( ang, Bernice, Bryneich, Beornice; la, Bernicia) was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England.

The Anglian territory of Bernicia was ap ...

, in the south-east. The first English king in the historical record is Ida, who is said to have obtained the throne and the kingdom about 547. Ida's grandson, Æthelfrith, united his kingdom with Deira

Deira ( ; Old Welsh/Cumbric: ''Deywr'' or ''Deifr''; ang, Derenrice or ) was an area of Post-Roman Britain, and a later Anglian kingdom.

Etymology

The name of the kingdom is of Brythonic origin, and is derived from the Proto-Celtic *''daru' ...

to the south to form Northumbria around the year 604. There were changes of dynasty, and the kingdom was divided, but it was re-united under Æthelfrith's son Oswald Oswald may refer to:

People

*Oswald (given name), including a list of people with the name

*Oswald (surname), including a list of people with the name

Fictional characters

*Oswald the Reeve, who tells a tale in Geoffrey Chaucer's ''The Canterbur ...

(r. 634–42), who had converted to Christianity while in exile in Dál Riata and looked to Iona for missionaries to help convert his kingdom.

Origins of the Kingdom of Alba

This situation was transformed in AD 793 when ferocious Viking raids began on monasteries like Iona and Lindisfarne, creating fear and confusion across the kingdoms of North Britain.

This situation was transformed in AD 793 when ferocious Viking raids began on monasteries like Iona and Lindisfarne, creating fear and confusion across the kingdoms of North Britain. Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

, Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the n ...

and the Western Isles eventually fell to the Norsemen. The King of Fortriu, Eógan mac Óengusa, and the King of Dál Riata Áed mac Boanta

Áed mac Boanta (died 839) is believed to have been a king of Dál Riata.

The only reference to Áed in the Irish annals is found in the Annals of Ulster, where it is recorded that " Eóganán mac Óengusa, Bran mac Óengusa, Áed mac Boanta, an ...

, were among the dead in a major defeat at the hands of the Vikings in 839. A mixture of Viking and Gaelic Irish settlement into south-west Scotland produced the Gall-Gaidel, the ''Norse Irish'', from which the region gets the modern name Galloway

Galloway ( ; sco, Gallowa; la, Gallovidia) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council area of Dumfries and Galloway.

A native or ...

. Sometime in the ninth century the beleaguered Kingdom of Dál Riata lost the Hebrides to the Vikings, when Ketil Flatnose

Ketill Björnsson, nicknamed Flatnose (Old Norse: ''Flatnefr''), was a Norse King of the Isles of the 9th century.

Primary sources

The story of Ketill and his daughter Auðr (or Aud) was probably first recorded by the Icelander Ari Þorgilsson ...

is said to have founded the Kingdom of the Isles

The Kingdom of the Isles consisted of the Isle of Man, the Hebrides and the islands of the Firth of Clyde from the 9th to the 13th centuries AD. The islands were known to the Norse as the , or "Southern Isles" as distinct from the or North ...

.

These threats may have speeded a long-term process of gaelicisation of the Pictish kingdoms, which adopted Gaelic language and customs. There was also a merger of the Gaelic and Pictish crowns, although historians debate whether it was a Pictish takeover of Dál Riata, or the other way around. This culminated in the rise of Cínaed mac Ailpín (Kenneth MacAlpin) in the 840s, which brought to power the House of Alpin

The House of Alpin, also known as the Alpínid dynasty, Clann Chináeda, and Clann Chinaeda meic Ailpín, was the kin-group which ruled in Pictland, possibly Dál Riata, and then the kingdom of Alba from the advent of Kenneth MacAlpin (Cináed ...

.B. Yorke, ''The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c.600–800'' (Pearson Education, 2006), , p. 54. In AD 867 the Vikings seized Northumbria, forming the Kingdom of York

Scandinavian York ( non, Jórvík) Viking Yorkshire or Norwegian York is a term used by historians for the south of Northumbria (modern-day Yorkshire) during the period of the late 9th century and first half of the 10th century, when it was do ...

;D. W. Rollason, ''Northumbria, 500–1100: Creation and Destruction of a Kingdom'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), , p. 212. three years later they stormed the Britons' fortress of Dumbarton and subsequently conquered much of England except for a reduced Kingdom of Wessex, leaving the new combined Pictish and Gaelic kingdom almost encircled. When he died as king of the combined kingdom in 900, Domnall II (Donald II) was the first man to be called ''rí Alban'' (i.e. ''King of Alba''). The term Scotia would be increasingly be used to describe the kingdom between North of the Forth and Clyde and eventually the entire area controlled by its kings would be referred to as Scotland.B. Webster, ''Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity'' (St. Martin's Press, 1997), , p. 22.

High Middle Ages

Gaelic kings: Constantine II to Alexander I

The long reign (900–942/3) of Causantín (Constantine II) is often regarded as the key to formation of the Kingdom of Alba. He was later credited with bringing Scottish Christianity into conformity with the Catholic Church. After fighting many battles, his defeat at

The long reign (900–942/3) of Causantín (Constantine II) is often regarded as the key to formation of the Kingdom of Alba. He was later credited with bringing Scottish Christianity into conformity with the Catholic Church. After fighting many battles, his defeat at Brunanburh

The Battle of Brunanburh was fought in 937 between Æthelstan, King of England, and an alliance of Olaf Guthfrithson, King of Dublin, Constantine II, King of Scotland, and Owain, King of Strathclyde. The battle is often cited as the point ...

was followed by his retirement as a Culdee monk at St. Andrews. The period between the accession of his successor Máel Coluim I (Malcolm I) and Máel Coluim mac Cináeda (Malcolm II) was marked by good relations with the Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

rulers of England, intense internal dynastic disunity and relatively successful expansionary policies. In 945, Máel Coluim I annexed Strathclyde

Strathclyde ( in Gaelic, meaning "strath (valley) of the River Clyde") was one of nine former local government regions of Scotland created in 1975 by the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 and abolished in 1996 by the Local Government et ...

, where the kings of Alba had probably exercised some authority since the later ninth century, as part of an agreement with King Edmund of England. This event was offset by loss of control in Moray. The reign of King Donnchad I (Duncan I) from 1034 was marred by failed military adventures, and he was defeated and killed by Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

, the Mormaer of Moray

The title Earl of Moray, Mormaer of Moray or King of Moray was originally held by the rulers of the Province of Moray, which existed from the 10th century with varying degrees of independence from the Kingdom of Alba to the south. Until 1130 ...

, who became king in 1040. MacBeth ruled for 17 years before he was overthrown by Máel Coluim, the son of Donnchad, who some months later defeated Macbeth's step-son

A stepchild is the offspring of one's spouse, but not one's own offspring, either biologically or through adoption.

Stepchildren can come into a family in a variety of ways. A stepchild may be the child of one's spouse from a previous relationshi ...

and successor Lulach to become king Máel Coluim III (Malcolm III).J. D. Mackie, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Pelican, 1964). p. 43.

It was Máel Coluim III, who acquired the nickname "Canmore" (''Cenn Mór'', "Great Chief"), which he passed to his successors and who did most to create the Dunkeld dynasty

The House of Dunkeld (in or "of the Caledonians") is a historiographical and genealogical construct to illustrate the clear succession of Scottish kings from 1034 to 1040 and from 1058 to 1286. The line is also variously referred to by historians ...

that ruled Scotland for the following two centuries. Particularly important was his second marriage to the Anglo-Hungarian princess Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular through ...

. This marriage, and raids on northern England, prompted William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

to invade and Máel Coluim submitted to his authority, opening up Scotland to later claims of sovereignty by English kings. When Malcolm died in 1093, his brother Domnall III (Donald III) succeeded him. However, William II of England

William II ( xno, Williame; – 2 August 1100) was King of England from 26 September 1087 until his death in 1100, with powers over Normandy and influence in Scotland. He was less successful in extending control into Wales. The third so ...

backed Máel Coluim's son by his first marriage, Donnchad, as a pretender to the throne and he seized power. His murder within a few months saw Domnall restored with one of Máel Coluim sons by his second marriage, Edmund

Edmund is a masculine given name or surname in the English language. The name is derived from the Old English elements ''ēad'', meaning "prosperity" or "riches", and ''mund'', meaning "protector".

Persons named Edmund include:

People Kings an ...

, as his heir. The two ruled Scotland until two of Edmund's younger brothers returned from exile in England, again with English military backing. Victorious, Edgar

Edgar is a commonly used English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Eadgar'' (composed of '' ead'' "rich, prosperous" and '' gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the later medieval period; it was, however, r ...

, the oldest of the three, became king in 1097.B. Webster, ''Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity'' (St. Martin's Press, 1997), , pp. 23–4. Shortly afterwards Edgar and the King of Norway, Magnus Bare Legs concluded a treaty recognising Norwegian authority over the Western Isles. In practice Norse control of the Isles was loose, with local chiefs enjoying a high degree of independence. He was succeeded by his brother Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

, who reigned 1107–24.

Scoto-Norman kings: David I to Alexander III

When Alexander died in 1124, the crown passed to Margaret's fourth son

When Alexander died in 1124, the crown passed to Margaret's fourth son David I David I may refer to:

* David I, Caucasian Albanian Catholicos c. 399

* David I of Armenia, Catholicos of Armenia (728–741)

* David I Kuropalates of Georgia (died 881)

* David I Anhoghin, king of Lori (ruled 989–1048)

* David I of Scotland ...

, who had spent most of his life as an English baron. His reign saw what has been characterised as a " Davidian Revolution", by which native institutions and personnel were replaced by English and French ones, underpinning the development of later Medieval Scotland.G. W. S. Barrow, "David I of Scotland: The Balance of New and Old", in G. W. S. Barrow, ed., ''Scotland and Its Neighbours in the Middle Ages'' (London, 1992), pp. 9–11 pp. 9–11. Members of the Anglo-Norman nobility took up places in the Scottish aristocracy and he introduced a system of feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

land tenure, which produced knight service, castles and an available body of heavily armed body of cavalry. He created an Anglo-Norman style of court, introduced the office of justicar

Justiciar is the English form of the medieval Latin term ''justiciarius'' or ''justitiarius'' ("man of justice", i.e. judge). During the Middle Ages in England, the Chief Justiciar (later known simply as the Justiciar) was roughly equivalen ...

to oversee justice, and local offices of sheriffs

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly trans ...

to administer localities. He established the first royal burgh

A royal burgh () was a type of Scottish burgh which had been founded by, or subsequently granted, a royal charter. Although abolished by law in 1975, the term is still used by many former royal burghs.

Most royal burghs were either created by ...

s in Scotland, granting rights to particular settlements, which led to the development of the first true Scottish towns and helped facilitate economic development as did the introduction of the first recorded Scottish coinage. He continued a process begun by his mother and brothers, of helping to establish foundations that brought the reformed monasticism based on that at Cluny

Cluny () is a commune in the eastern French department of Saône-et-Loire, in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is northwest of Mâcon.

The town grew up around the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded by Duke William I of Aquitaine in ...

. He also played a part in the organisation of diocese on lines closer to those in the rest of Western Europe.B. Webster, ''Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity'' (St. Martin's Press, 1997), , pp. 29–37.

These reforms were pursued under his successors and grandchildren Malcolm IV of Scotland and William I

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

, with the crown now passing down the main line of descent through primogeniture, leading to the first of a series of minorities. The benefits of greater authority were reaped by William's son Alexander II and his son Alexander III, who pursued a policy of peace with England to expand their authority in the Highlands and Islands. By the reign of Alexander III, the Scots were in a position to annexe the remainder of the western seaboard, which they did following Haakon Haakonarson's ill-fated invasion and the stalemate of the Battle of Largs

The Battle of Largs (2 October 1263) was a battle between the kingdoms of Norway and Scotland, on the Firth of Clyde near Largs, Scotland. Through it, Scotland achieved the end of 500 years of Norse Viking depredations and invasions despite bei ...

with the Treaty of Perth

The Treaty of Perth, signed 2 July 1266, ended military conflict between Magnus VI of Norway and Alexander III of Scotland over possession of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man. The text of the treaty.

The Hebrides and the Isle of Man had becom ...

in 1266.A. Macquarrie, ''Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation'' (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), , p. 153.

Late Middle Ages

Wars of Independence: Margaret to David II

The death of King Alexander III in 1286, and then of his granddaughter and heir Margaret, Maid of Norway in 1290, left 14 rivals for succession. To prevent civil war the Scottish magnates asked

The death of King Alexander III in 1286, and then of his granddaughter and heir Margaret, Maid of Norway in 1290, left 14 rivals for succession. To prevent civil war the Scottish magnates asked Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a va ...

to arbitrate, for which he extracted legal recognition that the realm of Scotland was held as a feudal dependency to the throne of England before choosing John Balliol

John Balliol ( – late 1314), known derisively as ''Toom Tabard'' (meaning "empty coat" – coat of arms), was King of Scots from 1292 to 1296. Little is known of his early life. After the death of Margaret, Maid of Norway, Scotland entered a ...

, the man with the strongest claim, who became king in 1292. Robert Bruce, 5th Lord of Annandale

Robert V de Brus (Robert de Brus), 5th Lord of Annandale (ca. 1215 – 31 March or 3 May 1295), was a feudal lord, justice and constable of Scotland and England, a regent of Scotland, and a competitor for the Scottish throne in 1290/92 in the ...

, the next strongest claimant, accepted this outcome with reluctance. Over the next few years Edward I used the concessions he had gained to systematically undermine both the authority of King John and the independence of Scotland. In 1295 John, on the urgings of his chief councillors, entered into an alliance with France, known as the Auld Alliance

The Auld Alliance ( Scots for "Old Alliance"; ; ) is an alliance made in 1295 between the kingdoms of Scotland and France against England. The Scots word ''auld'', meaning ''old'', has become a partly affectionate term for the long-lasting a ...

. In 1296 Edward invaded Scotland, deposing King John. The following year William Wallace

Sir William Wallace ( gd, Uilleam Uallas, ; Norman French: ; 23 August 1305) was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

Along with Andrew Moray, Wallace defeated an English army ...

and Andrew de Moray

Andrew Moray ( xno, Andreu de Moray; la, Andreas de Moravia), also known as Andrew de Moray, Andrew of Moray, or Andrew Murray, was an esquire, who became one of Scotland's war-leaders during the First Scottish War of Independence. Moray, he ...

raised forces to resist the occupation and under their joint leadership an English army was defeated at the Battle of Stirling Bridge

The Battle of Stirling Bridge ( gd, Blàr Drochaid Shruighlea) was a battle of the First War of Scottish Independence. On 11 September 1297, the forces of Andrew Moray and William Wallace defeated the combined English forces of John de Warenne ...

. For a short time Wallace ruled Scotland in the name of John Balliol as guardian of the realm. Edward came north in person and defeated Wallace at the Battle of Falkirk

The Battle of Falkirk (''Blàr na h-Eaglaise Brice'' in Gaelic), on 22 July 1298, was one of the major battles in the First War of Scottish Independence. Led by King Edward I of England, the English army defeated the Scots, led by William Wa ...

. The English barons refuted the French-inspired papal claim to Scottish overlordship in the Barons' Letter, 1301

The Barons' Letter of 1301 was written by seven English earls and 96 English barons to Pope Boniface VIII as a repudiation of his claim of feudal overlordship of Scotland (expressed in the Bull Scimus Fili), and as a defence of the rights of Ki ...

, claiming it rather as long possessed by English kings. Wallace escaped but probably resigned as Guardian of Scotland. In 1305 he fell into the hands of the English, who executed him for treason despite the fact that he believed he owed no allegiance to England.

Rivals John Comyn and Robert the Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (Scottish Gaelic: ''Raibeart an Bruis''), was King of Scots from 1306 to his death in 1329. One of the most renowned warriors of his generation, Robert eventuall ...

, grandson of the claimant, were appointed as joint guardians in his place.David R. Ross, ''On the Trail of Robert the Bruce'' (Dundurn Press Ltd., 1999), , p. 21. On 10 February 1306, Bruce participated in the murder of Comyn, at Greyfriars Kirk in Dumfries

Dumfries ( ; sco, Dumfries; from gd, Dùn Phris ) is a market town and former royal burgh within the Dumfries and Galloway council area of Scotland. It is located near the mouth of the River Nith into the Solway Firth about by road from t ...

. Less than seven weeks later, on 25 March, Bruce was crowned as king. However, Edward's forces overran the country after defeating Bruce's small army at the Battle of Methven

The Battle of Methven took place at Methven, Scotland on 19 June 1306, during the Wars of Scottish Independence. The battlefield was researched to be included in the Inventory of Historic Battlefields in Scotland and protected by Historic Sco ...

. Despite the excommunication of Bruce and his followers by Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V ( la, Clemens Quintus; c. 1264 – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his de ...

, his support slowly strengthened; and by 1314 with the help of leading nobles such as Sir James Douglas and Thomas Randolph only the castles at Bothwell and Stirling remained under English control. Edward I had died in 1307. His heir Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to ...

moved an army north to break the siege of Stirling Castle

Stirling Castle, located in Stirling, is one of the largest and most important castles in Scotland, both historically and architecturally. The castle sits atop Castle Hill, an intrusive crag, which forms part of the Stirling Sill geological ...

and reassert control. Robert defeated that army at the Battle of Bannockburn

The Battle of Bannockburn ( gd, Blàr Allt nam Bànag or ) fought on June 23–24, 1314, was a victory of the army of King of Scots Robert the Bruce over the army of King Edward II of England in the First War of Scottish Independence. It wa ...

in 1314, securing ''de facto'' independence. In 1320 the Declaration of Arbroath

The Declaration of Arbroath ( la, Declaratio Arbroathis; sco, Declaration o Aiberbrothock; gd, Tiomnadh Bhruis) is the name usually given to a letter, dated 6 April 1320 at Arbroath, written by Scottish barons and addressed to Pope John ...

, a remonstrance to the pope from the nobles of Scotland, helped convince Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII ( la, Ioannes PP. XXII; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death in December 1334.

He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Pope, elected b ...

to overturn the earlier excommunication and nullify the various acts of submission by Scottish kings to English ones so that Scotland's sovereignty could be recognised by the major European dynasties. The declaration has also been seen as one of the most important documents in the development of a Scottish national identity.

In 1328, Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

signed the Treaty of Northampton

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

acknowledging Scottish independence under the rule of Robert the Bruce.M. H. Keen, ''England in the Later Middle Ages: a Political History'' (London: Routledge, 2nd edn., 2003), , pp. 86–8. However, four years after Robert's death in 1329, England once more invaded on the pretext of restoring Edward Balliol

Edward Balliol (; 1283 – January 1364) was a claimant to the Scottish throne during the Second War of Scottish Independence. With English help, he ruled parts of the kingdom from 1332 to 1356.

Early life

Edward was the eldest son of John B ...

, son of John Balliol, to the Scottish throne, thus starting the Second War of Independence. Despite victories at Dupplin Moor and Halidon Hill, in the face of tough Scottish resistance led by Sir Andrew Murray

Sir Andrew Murray (1298–1338), also known as Sir Andrew Moray, or Sir Andrew de Moray, was a Scottish military and political leader who supported King David II of Scotland against Edward Balliol and King Edward III of England during the Secon ...

, the son of Wallace's comrade in arms, successive attempts to secure Balliol on the throne failed. Edward III lost interest in the fate of his protégé after the outbreak of the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of England and France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French throne between the English House of Plantagen ...

with France. In 1341 David II, King Robert's son and heir, was able to return from temporary exile in France. Balliol finally resigned his claim to the throne to Edward in 1356, before retiring to Yorkshire, where he died in 1364.

The Stewarts: Robert II to James IV

After David II's death, Robert II, the first of the Stewart kings, came to the throne in 1371. He was followed in 1390 by his ailing son John, who took the

After David II's death, Robert II, the first of the Stewart kings, came to the throne in 1371. He was followed in 1390 by his ailing son John, who took the regnal name

A regnal name, or regnant name or reign name, is the name used by monarchs and popes during their reigns and, subsequently, historically. Since ancient times, some monarchs have chosen to use a different name from their original name when they ...

Robert III. During Robert III's reign (1390–1406), actual power rested largely in the hands of his brother, Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany

Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany (c. 1340 – 3 September 1420) was a member of the Scottish royal family who served as regent (at least partially) to three Scottish monarchs ( Robert II, Robert III, and James I). A ruthless politician, Albany ...

.S. H. Rigby, ''A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages'' (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), , pp. 301–2. After the suspicious death (possibly on the orders of the Duke of Albany) of his elder son, David, Duke of Rothesay in 1402, Robert, fearful for the safety of his younger son, the future James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

, sent him to France in 1406. However, the English captured him en route and he spent the next 18 years as a prisoner held for ransom. As a result, after the death of Robert III, regents ruled Scotland: first, the Duke of Albany; and later his son Murdoch

Murdoch ( , ) is an Irish/Scottish given name, as well as a surname. The name is derived from old Gaelic words ''mur'', meaning "sea" and ''murchadh'', meaning "sea warrior". The following is a list of notable people or entities with the name.

...

.

When Scotland finally paid the ransom in 1424, James, aged 32, returned with his English bride determined to assert this authority. Several members of the Albany family were executed, and he succeeded in centralising control in the hands of the crown, but at the cost of increasingly unpopularity and he was assassinated in 1437. His son James II when he came of age in 1449, continued his father's policy of weakening the great noble families, most notably taking on the powerful Black Douglas family that had come to prominence at the time of Robert I. His attempt to take Roxburgh from the English in 1460 succeeded, but at the cost of his life as he was killed by an exploding artillery piece.A. D. M. Barrell, ''Medieval Scotland'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), , pp. 160–9.

His young son came to the throne as James III, resulting in another minority, with Robert, Lord Boyd emerging as the most important figure. In 1468 James married Margaret of Denmark, receiving the Orkney and the Shetland Islands in payment of her dowry.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , p. 5. In 1469 the King asserted his control, executing members of the Boyd family and his brothers, Alexander, Duke of Albany

Alexander Stewart, Duke of Albany (7 August 1485), was a Scottish prince and the second surviving son of King James II of Scotland. He fell out with his older brother, King James III, and fled to France, where he unsuccessfully sought help. In 1 ...

and John, Earl of Mar, resulting in Albany leading an English backed invasion and becoming effective ruler. The English retreated, having taken Berwick for the last time in 1482, and James was able to regain power. However, the King managed to alienate the barons, former supporters, his wife and his son James. He was defeated at the Battle of Sauchieburn and killed in 1488.

His successor James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

successfully ended the quasi-independent rule of the Lord of the Isles

The Lord of the Isles or King of the Isles

( gd, Triath nan Eilean or ) is a title of Scottish nobility with historical roots that go back beyond the Kingdom of Scotland. It began with Somerled in the 12th century and thereafter the title ...

, bringing the Western Isles under effective Royal control for the first time. In 1503, he married Margaret Tudor

Margaret Tudor (28 November 1489 – 18 October 1541) was Queen of Scotland from 1503 until 1513 by marriage to King James IV. She then served as regent of Scotland during her son's minority, and successfully fought to extend her regency. Ma ...

, daughter of Henry VII of England

Henry VII (28 January 1457 – 21 April 1509) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizure of the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death in 1509. He was the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Henry's mother, Margaret Beauf ...

, thus laying the foundation for the seventeenth century Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns ( gd, Aonadh nan Crùintean; sco, Union o the Crouns) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas dip ...

. However, in 1512 the Auld Alliance was renewed and under its terms, when the French were attacked by the English under Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

the next year, James IV invaded England in support. The invasion was stopped decisively at the Battle of Flodden

The Battle of Flodden, Flodden Field, or occasionally Branxton, (Brainston Moor) was a battle fought on 9 September 1513 during the War of the League of Cambrai between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland, resulting in an English ...

during which the King, many of his nobles, and a large number of ordinary troops were killed. Once again Scotland's government lay in the hands of regents in the name of the infant James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV and Margaret Tudor, and du ...

.G. Menzies ''The Scottish Nation'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2002), , p. 179.

Government

Scone

A scone is a baked good, usually made of either wheat or oatmeal with baking powder as a leavening agent, and baked on sheet pans. A scone is often slightly sweetened and occasionally glazed with egg wash. The scone is a basic component ...

.B. Webster, ''Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity'' (St. Martin's Press, 1997), , pp. 45–7. While the Scottish monarchy remained a largely itinerant institution, Scone remained one of its most important locations,P. G. B. McNeill and Hector L. MacQueen, eds, ''Atlas of Scottish History to 1707'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), pp. 159–63. with Royal castles at Stirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

and Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

becoming significant in the later Middle Ages before Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

developed as a capital in the second half of the fifteenth century.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 14–15. The Scottish crown grew in prestige throughout the era and adopted the conventional offices of Western European courts and later elements of their ritual and grandeur.

In the early period the kings of the Scots depended on the great lords of the mormaer

In early medieval Scotland, a mormaer was the Gaelic name for a regional or provincial ruler, theoretically second only to the King of Scots, and the senior of a ''Toísech'' (chieftain). Mormaers were equivalent to English earls or Continental c ...

s (later earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant " chieftain", particu ...

s) and Toísechs (later thanes), but from the reign of David I sheriffdom

A sheriffdom is a judicial district in Scotland, led by a sheriff principal. Since 1 January 1975, there have been six sheriffdoms. Each sheriffdom is divided into a series of sheriff court districts, and each sheriff court is presided over by a r ...

s were introduced, which allowed more direct control and gradually limited the power of the major lordships.P. G. B. McNeill and Hector L. MacQueen, eds, ''Atlas of Scottish History to 1707'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), pp. 191–4. While knowledge of early systems of law is limited, justice can be seen as developing from the twelfth century onwards with local sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

, burgh

A burgh is an autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland and Northern England, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when King David I created the first royal burghs. Bur ...

, manorial and ecclesiastical court

An ecclesiastical court, also called court Christian or court spiritual, is any of certain courts having jurisdiction mainly in spiritual or religious matters. In the Middle Ages, these courts had much wider powers in many areas of Europe than be ...

s and offices of the justicar to oversee administration.K. Reid and R. Zimmerman, ''A History of Private Law in Scotland: I. Introduction and Property'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), , pp. 24–82. The Scots common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

began to develop in this period and there were attempts to systematise and codify the law and the beginnings of an educated professional body of lawyers.K. Reid and R. Zimmerman, ''A History of Private Law in Scotland: I. Introduction and Property'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), , p. 66. In the Late Middle Ages major institutions of government, including the privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

and parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

developed. The council emerged as a full-time body in the fifteenth century, increasingly dominated by laymen and critical to the administration of justice. Parliament also emerged as a major legal institution, gaining an oversight of taxation and policy. By the end of the era it was sitting almost every year, partly because of the frequent minorities and regencies of the period, which may have prevented it from being sidelined by the monarchy.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 21–3.

Warfare

In the Early Middle Ages, war on land was characterised by the use of small war-bands of household troops often engaging in raids and low level warfare.L. Alcock, ''Kings and Warriors, Craftsmen and Priests in Northern Britain AD 550–850'' (Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland), , pp. 248–9. The arrival of the Vikings brought a new scale of naval warfare, with rapid movement based around the Viking longship. The

In the Early Middle Ages, war on land was characterised by the use of small war-bands of household troops often engaging in raids and low level warfare.L. Alcock, ''Kings and Warriors, Craftsmen and Priests in Northern Britain AD 550–850'' (Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland), , pp. 248–9. The arrival of the Vikings brought a new scale of naval warfare, with rapid movement based around the Viking longship. The birlinn

The birlinn ( gd, bìrlinn) or West Highland galley was a wooden vessel propelled by sail and oar, used extensively in the Hebrides and West Highlands of Scotland from the Middle Ages on. Variants of the name in English and Lowland Scots in ...

, which developed from the longship, became a major factor in warfare in the Highlands and Islands. By the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended ...

, the kings of Scotland could command forces of tens of thousands of men for short periods as part of the "common army", mainly of poorly armoured spear and bowmen. After the introduction of feudalism to Scotland, these forces were augmented by small numbers of mounted and heavily armoured knights. Feudalism also introduced castles into the country, originally simple wooden motte-and-bailey

A motte-and-bailey castle is a European fortification with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised area of ground called a motte, accompanied by a walled courtyard, or bailey, surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade. Relatively easy t ...

constructions, but these were replaced in the thirteenth century with more formidable stone "enceinte

Enceinte (from Latin incinctus: girdled, surrounded) is a French term that refers to the "main defensive enclosure of a fortification". For a castle, this is the main defensive line of wall towers and curtain walls enclosing the position. For ...

" castles, with high encircling walls.T. W. West, ''Discovering Scottish Architecture'' (Botley: Osprey, 1985), , p. 21. In the thirteenth century the threat of Scandinavian naval power subsided and the kings of Scotland were able to use naval forces to help subdue the Highlands and Islands.