Mebyon Kernow on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mebyon Kernow – The Party for Cornwall (, MK; Cornish for ''Sons of Cornwall'') is a Cornish nationalist,

Three months later the

Three months later the

Stephen Richardson , Blog MK contested all six Cornish constituencies in the 2015 United Kingdom general election, 2015 general election. It complained against not being granted a party election broadcast: under current guidelines, it would need to stand in eighty-three constituencies outside of Cornwall in order to qualify for a broadcast. Ahead of the 2016 referendum on the issue, MK endorsed the United Kingdom's continued membership of the

Thisiscornwall.co.uk (1 November 2011). In November 2011 Eileen Carter resigned as a member of Perranzabuloe Parish Council, Perranporth Ward. In 2021, Zoe Fox, a Mebyon Kernow councillor, became Mayor of

European Election 2009: South West

BBC News (8 June 2009). Since 2009, MK has not stood candidates in European Parliament elections, given the difficulties of winning a seat in a constituency encompassing electorates outside Cornwall.

Mebyon Kernow website

Kernow X website

{{Authority control 1951 establishments in the United Kingdom Celtic nationalism Civic nationalism Cornish nationalism Cornish nationalist parties European Free Alliance Home rule in the United Kingdom Political parties established in 1951 Politics of Cornwall Pro-European political parties in the United Kingdom Regionalist parties in the United Kingdom Social democratic parties in the United Kingdom

centre-left

Centre-left politics lean to the left on the left–right political spectrum but are closer to the centre than other left-wing politics. Those on the centre-left believe in working within the established systems to improve social justice. The ...

political party in Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

, in southwestern Britain. It currently has five elected councillors on Cornwall Council

Cornwall Council ( kw, Konsel Kernow) is the unitary authority for Cornwall in the United Kingdom, not including the Isles of Scilly, which has its own unitary council. The council, and its predecessor Cornwall County Council, has a tradition ...

, and several town and parish councillors across Cornwall.

Influenced by the growth of Cornish nationalism in the first half of the twentieth century, Mebyon Kernow formed as a pressure group

Advocacy groups, also known as interest groups, special interest groups, lobbying groups or pressure groups use various forms of advocacy in order to influence public opinion and ultimately policy. They play an important role in the develop ...

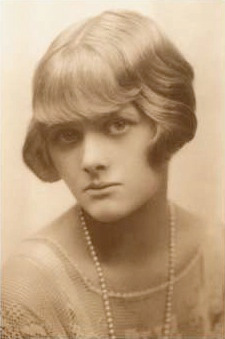

in 1951. Helena Charles was its first chair, while the novelist Daphne du Maurier

Dame Daphne du Maurier, Lady Browning, (; 13 May 1907 – 19 April 1989) was an English novelist, biographer and playwright. Her parents were actor-manager Sir Gerald du Maurier and his wife, actress Muriel Beaumont. Her grandfather was Geo ...

was another early member. In 1953 Charles won a seat on a local council, although lost it in 1955. Support for MK grew in the 1960s in opposition to growing migration into Cornwall from parts of England. In the 1970s, MK became a fully-fledged political party, and since then it has fielded candidates in elections to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

and the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the Legislature, legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven Institutions of the European Union, institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and in ...

, as well as local government in Cornwall. Infighting during the 1980s decimated the party but it revived in the 1990s.

Ideologically positioned on the centre-left

Centre-left politics lean to the left on the left–right political spectrum but are closer to the centre than other left-wing politics. Those on the centre-left believe in working within the established systems to improve social justice. The ...

of British politics, the central tenet of Mebyon Kernow's platform is Cornish nationalism. It emphasises a distinct Cornish identity, including the Cornish language

Cornish (Standard Written Form: or ) , is a Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family. It is a revived language, having become extinct as a living community language in Cornwall at the end of the 18th century. However, ...

and elements of Cornish culture

The culture of Cornwall ( kw, Gonisogeth Kernow) forms part of the culture of the United Kingdom, but has distinct customs, traditions and peculiarities. Cornwall has many strong local traditions. After many years of decline, Cornish culture h ...

. It campaigns for devolution

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territories ...

to Cornwall in the form of a Cornish Assembly

A Cornish Assembly ( kw, Senedh Kernow) is a proposed devolved law-making assembly for Cornwall along the lines of the Scottish Parliament, the Senedd (Welsh Parliament) and the Northern Ireland Assembly in the United Kingdom.

The campaign fo ...

. Economically, it is social democratic

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

, calling for continued public ownership

State ownership, also called government ownership and public ownership, is the ownership of an industry, asset, or enterprise by the state or a public body representing a community, as opposed to an individual or private party. Public ownershi ...

of education and healthcare and the renationalisation of railways. It also calls for greater environmental protection

Environmental protection is the practice of protecting the natural environment by individuals, organizations and governments. Its objectives are to conserve natural resources and the existing natural environment and, where possible, to repair dam ...

and continued UK membership of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

.

The party is a member of the European Free Alliance

The European Free Alliance (EFA) is a European political party that consists of various regionalist, separatist and ethnic minority political parties in Europe. Member parties advocate either for full political independence and sovereignty, ...

and has close links with Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru ( ; ; officially Plaid Cymru – the Party of Wales, often referred to simply as Plaid) is a centre-left to left-wing, Welsh nationalist political party in Wales, committed to Welsh independence from the United Kingdom.

Plaid wa ...

, the Scottish National Party

The Scottish National Party (SNP; sco, Scots National Pairty, gd, Pàrtaidh Nàiseanta na h-Alba ) is a Scottish nationalist and social democratic political party in Scotland. The SNP supports and campaigns for Scottish independence from th ...

and the Breton Democratic Union

Breton Democratic Union (french: Union démocratique bretonne, br, Unvaniezh Demokratel Breizh, UDB) is a Breton nationalist, autonomist, and regionalist political party in Brittany (''Bretagne administrée'') and Loire-Atlantique. The UDB ad ...

.

Several former Cornish MPs have been supporters of MK, including Andrew George (Liberal Democrat

Several political parties from around the world have been called the Liberal Democratic Party or Liberal Democrats. These parties usually follow a liberal democratic ideology.

Active parties

Former parties

See also

*Liberal democracy

*Lib ...

), Peter Bessell (Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

), John Pardoe

John Wentworth Pardoe (born 27 July 1934) is a retired British businessman and Liberal Party politician. He was Chairman of Sight and Sound Education Ltd from 1979 to 1989.

Early life and education

Pardoe was the son of Cuthbert B. Pardoe and ...

(Liberal Party), David Mudd

William David Mudd (2 June 1933 – 28 April 2020) was a British politician.

Mudd was born in Falmouth, Cornwall, in June 1933. He was educated at Truro Cathedral School and was a member of the Tavistock Urban District Council from 1959 to 19 ...

(Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

), and David Penhaligon (Liberal Party). George was himself a member of MK in his youth.

History

Founding (1950s)

In the half-century preceding its foundation, Cornish identity had been strengthened by theCeltic Revival

The Celtic Revival (also referred to as the Celtic Twilight) is a variety of movements and trends in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries that see a renewed interest in aspects of Celtic culture. Artists and writers drew on the traditions of Gae ...

, especially by the revival of the Cornish language. Cornish politics was dominated by the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

and the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

, with the Labour Party a distant third in the Duchy, in part because of Cornwall's declining tin-mining industry. Both the Liberal Party and the Labour Party had courted Cornish nationalism in their local campaigns, with both parties portraying "a distinctly Cornish image"; in turn, this meant that Cornish nationalism was from its inception associated with centre-left politics

Centre-left politics lean to the left on the left–right political spectrum but are closer to the centre than other left-wing politics. Those on the centre-left believe in working within the established systems to improve social justice. The ...

. Many of MK's initial supporters came from the Liberal Party, which had endorsed Home Rule for Ireland

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the e ...

. Early members of MK cited their absence from Cornwall during their university years and the war as instrumental in the formation of their Cornish identity. A catalyst for the party's foundation was the Celtic Congress

The International Celtic Congress ( br, Ar C'hendalc'h Keltiek, kw, An Guntelles Keltek, gv, Yn Cohaglym Celtiagh, gd, A' Chòmhdhail Cheilteach, ga, An Chomhdháil Cheilteach, cy, Y Gyngres Geltaidd) is a cultural organisation that seeks to ...

of 1950, held at the Royal Institution of Cornwall

The Royal Institution of Cornwall (RIC) is a Learned society in Truro, Cornwall, United Kingdom.

It was founded in Truro on 5 February 1818 as the Cornwall Literary and Philosophical Institution. The Institution was one of the earliest of seve ...

in Truro

Truro (; kw, Truru) is a cathedral city and civil parish in Cornwall, England. It is Cornwall's county town, sole city and centre for administration, leisure and retail trading. Its population was 18,766 in the 2011 census. People of Truro ...

, which facilitated the exchange of ideas between Cornish nationalists and other Celtic groups.

MK was founded as a pressure group

Advocacy groups, also known as interest groups, special interest groups, lobbying groups or pressure groups use various forms of advocacy in order to influence public opinion and ultimately policy. They play an important role in the develop ...

on 6 January 1951. At the party's inaugural meeting, held at the Oates Temperance Hotel in Redruth

Redruth ( , kw, Resrudh) is a town and civil parish in Cornwall, England. The population of Redruth was 14,018 at the 2011 census. In the same year the population of the Camborne-Redruth urban area, which also includes Carn Brea, Illogan ...

, thirteen people were present and a further seven sent their apologies. Helena Charles was elected as the organisation's first chair. MK adopted the following objectives:

#To study local conditions and attempt to remedy any that may be prejudicial to the best interests of Cornwall by the creation of public opinion or other means.

#To foster the Cornish language

Cornish (Standard Written Form: or ) , is a Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family. It is a revived language, having become extinct as a living community language in Cornwall at the end of the 18th century. However, ...

and Cornish literature

Cornish literature refers to written works in the Cornish language. The earliest surviving texts are in verse and date from the 14th century. There are virtually none from the 18th and 19th centuries but writing in revived forms of Cornish bega ...

.

#To encourage the study of Cornish history from a Cornish point of view.

#By self-knowledge to further the acceptance of the idea of the Celt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

ic character of Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

, one of the six Celtic nations

The Celtic nations are a cultural area and collection of geographical regions in Northwestern Europe where the Celtic languages and cultural traits have survived. The term ''nation'' is used in its original sense to mean a people who shar ...

.

#To publish pamphlets, broadsheets, articles and letters in the Press whenever possible, putting forward the foregoing aims.

#To arrange concerts and entertainments with a Cornish-Celtic flavour through which these aims can be further advanced.

#To co-operate with all societies concerned with preserving the character of Cornwall.

By September 1951 they had officially come to a stance of supporting self-government for Cornwall, when the fourth objective was replaced with: "To further the acceptance of the Celtic character of Cornwall and its right to self-government in domestic affairs in a Federated United Kingdom."

In its early years, MK engaged in cultural activities, such as producing Cornish calendars and sending a birthday prayer in Cornish to the Duke of Cornwall

Duke of Cornwall is a title in the Peerage of England, traditionally held by the eldest son of the reigning British monarch, previously the English monarch. The duchy of Cornwall was the first duchy created in England and was established by a r ...

. It highlighted the high proportion of executives in local government which were not Cornish and campaigned against inward migration to Cornwall from the rest of the United Kingdom. From 1952, the party was supported by ''New Cornwall'', a magazine which was edited by Charles until 1956. MK's agenda received support from the Liberal Party, whose candidates endorsed Home Rule for Cornwall. MK won its first seat in local government in 1953, when Charles won a seat on Redruth-Camborne Urban District Council, under the slogan of 'A Square Deal for the Cornish'. Charles lost her seat in 1955.

Following infighting between senior members who were frustrated at her radical separatism, in contrast to the passive culturalism of the broader Cultural nationalist movement, and following frustration at the party's dispersed and unenthusiastic membership, Charles resigned as Chairman of MK in 1956. Charles was replaced by Major Cecil Beer, a former civil servant who sought to reunify the Cornish nationalist movement. Beer's three years as chairman of MK provided "a period of quiet but steady growth", in which MK increased its membership and focussed on cultural rather than political issues. Party meetings largely focussed on "calendars, Christmas cards, serviettes, Cornish language classes and proposals for things like the Cornish kilt

A kilt ( gd, fèileadh ; Irish: ''féileadh'') is a garment resembling a wrap-around knee-length skirt, made of twill woven worsted wool with heavy pleats at the sides and back and traditionally a tartan pattern. Originating in the Scottish ...

."

Daphne du Maurier

Dame Daphne du Maurier, Lady Browning, (; 13 May 1907 – 19 April 1989) was an English novelist, biographer and playwright. Her parents were actor-manager Sir Gerald du Maurier and his wife, actress Muriel Beaumont. Her grandfather was Geo ...

, the well-known novelist, was an early member of MK. From its founding until the 1980s, the party was divided between proponents of ethnic nationalism

Ethnic nationalism, also known as ethnonationalism, is a form of nationalism wherein the nation and nationality are defined in terms of ethnicity, with emphasis on an ethnocentric (and in some cases an ethnocratic) approach to various politi ...

and proponents of civic nationalism

Civic nationalism, also known as liberal nationalism, is a form of nationalism identified by political philosophers who believe in an inclusive form of nationalism that adheres to traditional liberal values of freedom, tolerance, equality, i ...

.

Growth (1960s–1970s)

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, MK was in essence a small political pressure group rather than a true political party, with members being able to join other political parties as well. In February 1960, Beer was succeeded by Robert Dunstone as Chairman of MK. By March 1962, the party had seventy members, of which thirty were attending the party's infrequent meetings. Under Dunstone, the party followed a policy of "patient, persistent, and polite lobbying", the standard for which was set by its reaction to proposed railway closures in 1962, which included public meetings, letters of protest and the formation of a transport sub-committee of the party. MK campaigned for the establishment of a Cornish University, a Cornish Industrial Board, and the repatriation ofHeligoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possession ...

Frisians

The Frisians are a Germanic ethnic group native to the coastal regions of the Netherlands and northwestern Germany. They inhabit an area known as Frisia and are concentrated in the Dutch provinces of Friesland and Groningen and, in Germany, ...

whose land was used by the British government as a bombing range in the mid-1950s. It published numerous policy papers to support its positions.

MK gained popularity in the 1960s, when it campaigned against 'overspill' housing developments in Cornwall to accommodate incomers from Greater London. MK's opposition prompted opponents to label the party as racialist

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies can be more ex ...

; the party denied the allegations and responded with ''What Cornishmen Can Do'', a pamphlet published in September 1968 which proposed more investment in natural resources, food processing and technological industries, as well as a Cornish University, tidal barrages and more support for small farmers. Partly due to its opposition to overspill, by 1965, the party numbered 700 members, rising to 1,000 by early 1968. In April 1967, Colin Murley was elected for MK onto Cornwall County Council

Cornwall County Council ( kw, Konteth Konsel Kernow) was the county council of the non-metropolitan county of Cornwall in south west England. It came into its powers on 1 April 1889 and was abolished on 1 April 2009.

History

Cornwall County Counc ...

for the seat of St Day

St Day ( kw, Sen Day) is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated between the village of Chacewater and the town of Redruth. The electoral ward St Day and Lanner had a population at the 2011 census of 4,473 ...

& Lanner; he had stood on an anti-overspill platform. MK members also sat as independent councillors on the district council. The party grew to become the leading champion for Cornish nationalism

Cornish nationalism is a cultural, political and social movement that seeks the recognition of Cornwall – the south-westernmost part of the island of Great Britain – as a nation distinct from England. It is usually based on three gene ...

.

On St. Piran's Day in 1968, the first edition of ''Cornish Nation'' was published; this is the party's magazine. In the same year, Leonard Truran succeeded Dunstone as Chairman of MK; Dunstone then became the party's first Honorary President.

By the 1970s the group developed into a more coherent and unified organisation. At the annual conference in October 1967, party members voted for a resolution to contest elections to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, marking a turning point in MK's transition from a pressure group into a political party. The decision meant that councillors, prospective parliamentary candidates and MPs who held dual party membership began to disassociate themselves from MK. Despite the decision, a faction in MK remained frustrated at the continuing possibility of dual party membership, the wide range of views on Cornish nationalism in the party and MK's slow transition into a political party; this dissident faction formed the Cornish National Party in July 1969. The CNP's members were expelled from MK, but the CNP had disappointing election results in the 1970 county council elections, leading most CNP members to rejoin MK by the mid-1970s.

In the 1970 election, Richard Jenkin

Richard Garfield Jenkin (9 October 1925 – 29 October 2002), was a Cornish nationalist politician and one of the founding members of Mebyon Kernow. He was also a Grand Bard of the Gorseth Kernow.

Cornish language

In 1947, Jenkin was made a ...

, who would succeed Truran as Chairman of MK in 1973, won 2% of the vote in the Falmouth & Camborne constituency. James Whetter

James C. A. Whetter (20 September 1935 – 24 February 2018) was a British historian and politician, noted as a Cornish nationalist and editor of ''The Cornish Banner'' (''An Baner Kernewek''). He contested elections for two Cornish independence ...

stood for MK in the Truro

Truro (; kw, Truru) is a cathedral city and civil parish in Cornwall, England. It is Cornwall's county town, sole city and centre for administration, leisure and retail trading. Its population was 18,766 in the 2011 census. People of Truro ...

constituency in the general elections of February

February is the second month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian calendars. The month has 28 days in common years or 29 in leap years, with the 29th day being called the ''leap day''. It is the first of five months not to have 31 days (th ...

and October

October is the tenth month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian calendars and the sixth of seven months to have a length of 31 days. The eighth month in the old calendar of Romulus , October retained its name (from Latin and Greek ''ôct ...

1974, achieving 1.5% and 0.7% of the vote respectively. The party contested the constituencies of St Ives and Falmouth & Camborne in both the 1979

Events

January

* January 1

** United Nations Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim heralds the start of the '' International Year of the Child''. Many musicians donate to the '' Music for UNICEF Concert'' fund, among them ABBA, who write the so ...

and 1983

The year 1983 saw both the official beginning of the Internet and the first mobile cellular telephone call.

Events January

* January 1 – The migration of the ARPANET to TCP/IP is officially completed (this is considered to be the beginning ...

elections.F. W. S. Craig, ''British parliamentary election results, 1950–1973''. MK also contested the 1979 European Parliament election

The 1979 European Parliament election was a series of parliamentary elections held across all 9 (at the time) European Community member states. They were the first European elections to be held, allowing citizens to elect 410 MEPs to the Europe ...

, winning 5.9% of the vote in the constituency of Cornwall & West Plymouth.

Following Dunstone's death in 1973, E.G. Retallack Hooper was elected the party's Honorary President; Hooper was a former Grand Bard of the Gorseth Kernow

Gorsedh Kernow (Cornish Gorsedd) is a non-political Cornish organisation, based in Cornwall, United Kingdom, which exists to maintain the national Celtic spirit of Cornwall. It is based on the Welsh-based Gorsedd, which was founded by Iolo Morg ...

who had been a founding member of MK and was a prolific Cornish language writer and journalist.

The CNP's formation highlighted deep fissures in MK between its constitutionalist and separatist wings; these were exacerbated by continuing inward migration to Cornwall, leading to a 26% increase in its population in the two decades to 1981. The ''Cornish Nation'' gave increasingly sympathetic coverage of Irish republicanism; MK warned of civil unrest in Cornwall and the extermination of the Cornish national identity if overspill continued; and its members talked openly of plans to install a shadow government "in the name of the Cornish people in the event of civil breakdown". A motion to restrict party membership to those who were Cornish by "family trees going back through several centuries" was defeated in 1973; and a September 1974 issue of the ''Cornish Nation'' describing Michael Gaughan, an IRA hunger striker, as a "Celtic hero" was widely criticised in the press and rebuked by the party. MK's divisions came to a head in May 1975, when a motion to depose the party's leadership and integrate the party with the Revived Stannary Parliament, which had newly reopened in 1974, was narrowly defeated. On 28 May 1975, Whetter, who had led the defeated motion, resigned his membership of MK to form a second Cornish Nationalist Party

The Cornish Nationalist Party (CNP; kw, An Parti Kenethlegek Kernow) is a political party, founded by Dr James Whetter, who campaigned for independence for Cornwall.

History

It was formed by people who left Cornwall's main nationalist party Me ...

, which campaigned for full Cornish independence on a pro-European platform. This second CNP also had disappointing electoral results and has not contested elections since 1985.

During the 1970s, MK held rallies in support of Cornwall's fishing industry and against regional unemployment and nuclear waste; in the 1980s, these rallies were aggravated by the policies of the incumbent Thatcher government. Following the 1975 split, the party was re-energised by an influx of new, younger members, which also pushed MK more firmly away from its separatist wing. Citing concerns about its effect on Cornwall's fishing industry, the party opposed the Common Market; MK only began to endorse the UK's membership of the EEC in the 1980s.

Decline (1980s)

The party declined in the 1980s and was close to collapse by 1990. In 1980, renewed infighting over the party's structure led to a spate of resignations which received media attention; this included the resignation of Truran, who had served as party secretary after Jenkin had replaced him as Chairman of MK in 1973. Leading the infighting was a new, youthful leftist faction of MK, which sought to define the party's policies on defence, the monarchy and public ownership, bringing the party away from its traditional nationalist focus. While the infighting consolidated MK's economic stance as left-of-centre, the party's everchanging positions confused voters and presided over the decline of its magazines, including the ''Cornish Nation''. In 1983, Jenkin was replaced by Julyan Drew as the party leader; Drew was succeeded by Pedyr Prior in 1985 andLoveday Carlyon

Loveday Carlyon is a Cornish nationalist politician.

Originally from Torpoint, Carlyon joined Mebyon Kernow. She married fellow party member Julyan Holmes, and moved to Liskeard. She was soon elected to the town council, and became a promine ...

in 1986.

At the 1983 general election, MK achieved 1.2% of the vote in both Falmouth & Camborne and St Ives, reduced from 3% and 4% respectively in the previous election. It contested neither the 1984 European Parliament election

Events

January

* January 1 – The Bornean Sultanate of Brunei gains full independence from the United Kingdom, having become a British protectorate in 1888.

* January 7 – Brunei becomes the sixth member of the Association of Southeas ...

nor the 1987 general election; it received 1.9% of the vote in Cornwall & West Plymouth in the 1989 European Parliament election

The 1989 European Parliament election was a European election held across the 12 European Community member states in June 1989. It was the third European election but the first time that Spain and Portugal voted at the same time as the other me ...

. During this period, the party focussed on its opposition to the creation of a South West England

South West England, or the South West of England, is one of nine official regions of England. It consists of the counties of Bristol, Cornwall (including the Isles of Scilly), Dorset, Devon, Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire. Cities ...

region and the construction of a nuclear station at Luxulyan

Luxulyan (; kw, Logsulyan), also spelt Luxullian or Luxulian, is a village and civil parish in mid Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The village lies four miles (6.5 km) northeast of St Austell and six miles (10 km) south of Bodmin ...

; this latter campaign culminated in the formation of the Cornish Anti-Nuclear Alliance, which drew over 2,000 attendees to its first rallies in Truro in July 1980. MK's vociferous response to the planned building of 40,000 new homes in Cornwall, manifested in the formation in 1987 of the Cornish Alternatives to the Structure Plan, gained high-profile notability in Cornwall. MK also campaigned against tourism-centred economic development and the poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments f ...

. Nevertheless, public support for action was far lower than the previous decade and MK regressed into a pressure group.

In 1988, MK established the Campaign for a Cornish Constituency, which won the support of Cornwall County Council, all the district authorities, several Cornish organisations and three of Cornwall's five MPs. The campaign was well-publicised, attained national attention, and collected over 3,000 signatures in three months. The campaign called for an exclusively-Cornish European Parliament constituency and was founded on MK's long-standing opposition to amalgamating public boards and companies in Cornwall and Devon, a process which had steadily increased during the decade.

Relaunch (1990s)

In 1989, Carlyon resigned as MK's leader, leading to a review of the party's long-term strategy. Being close to collapse, in April 1990, the party's London branch convened a general meeting of all party members to consider whether the party should disband; it was agreed that the party would continue.Loveday Jenkin

Loveday Elizabeth Trevenen Jenkin is a British politician, biologist and language campaigner. She has been a member of Cornwall Council since 2011, and currently serves as councillor for Crowan, Sithney and Wendron.

Biography

Jenkin is the da ...

, daughter of Richard Jenkin, was promptly elected MK's leader. At this time, Truran, who had become a leading light in the Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

For ...

in Falmouth & Camborne since he had left the party in 1980, rejoined MK, re-energising the party. Nevertheless, MK did not contest the 1992 general election, focusing its efforts on lobbying for an exclusively-Cornish European Parliament constituency, a Cornish unitary authority, and the recognition of Cornwall as a European region.

Despite a promising local election result in 1993, obtaining an average of 17.5% per candidate in local government elections, MK's vote share declined further to 1.5% of the vote in the 1994 European Parliament election

The 1994 European Parliamentary election was a European election held across the 12 European Union member states in June 1994.

This election saw the merge of the European People's Party and European Democrats, an increase in the overall numbe ...

, in the new constituency of Cornwall & West Plymouth. Jenkin, who stood as the party's candidate, campaigned on a platform opposing out-of-town developments and a second Tamar crossing, and calling for greater Cornish representation in Europe.

In 1996, MK published 'Cornwall 2000 – The Way Ahead', its most detailed manifesto to date. The party fought the 1997 general election on its 18,000 words and delivered over 300,000 leaflets during the campaign; however, it polled merely 1,906 votes across four constituencies. MK activists were heavily involved in the 500th-anniversary commemorations of the Cornish Rebellion of 1497; these included a march from St. Keverne to Blackheath retracing the steps of the rebels, following which the participants demanded a Cornish Development Agency, an exclusively-Cornish seat in the European Parliament, a university campus in Cornwall and a Cornish curriculum for Cornish schools. The renewed interest in Cornish nationalism from this march led a group in MK to leave the party and form the An Gof National Party, another short-lived splinter group.

On 4 October 1997, at the Mebyon Kernow National Conference, Jenkin was replaced by Dick Cole as the leader of MK. One of Cole's earliest actions as leader was to launch the Cornish Millennium Convention on 8 March 1998, coinciding with protests at the closure of South Crofty, Cornwall's last working tin mine. However, the Convention's launch was eclipsed by the formation of Cornish Solidarity, a pressure group involved in direct action which grew from the South Crofty protests and had similar aims as MK. At the party's annual conference in 1998, Richard Jenkin was elected to succeed the late Hooper as Honorary President of MK.

In 1999, over 95% of members voted in favour of relaunching MK as Mebyon Kernow – the Party for Cornwall in order to distance itself from the ethnic nationalist 'Sons of Cornwall' label; the name change was adopted. The party did not contest the 1999 European Parliament election

The 1999 European Parliament election was a European election for all 626 members of the European Parliament held across the 15 European Union member states on 10, 11 and 13 June 1999. The voter turn-out was generally low, except in Belgium and L ...

, given the size of the new South West England constituency and the large prerequisite £5,000 deposit. It contested the 2001 general election, winning 3,199 votes across three constituencies.

Cornish Assembly Campaign

On 5 March 2000, MK launched a petition for aCornish Assembly

A Cornish Assembly ( kw, Senedh Kernow) is a proposed devolved law-making assembly for Cornwall along the lines of the Scottish Parliament, the Senedd (Welsh Parliament) and the Northern Ireland Assembly in the United Kingdom.

The campaign fo ...

. This was modelled from the "Declaration for a Cornish Assembly", which stated that: Three months later the

Three months later the Cornish Constitutional Convention

The Cornish Constitutional Convention (CCC; kw, Senedh Kernow) was formed in November 2000 with the objective of establishing a devolved Cornish Assembly (Senedh Kernow). The convention is a cross-party, cross-sector association with support both ...

was held with the objective of establishing a devolved Assembly. Within fifteen months, Mebyon Kernow's petition attracted the signatures of over 50,000 people calling for a referendum on a Cornish Assembly, which was a little over 10% of the total Cornish electorate. A delegation including Cole, Andrew George, then the Liberal Democrat

Several political parties from around the world have been called the Liberal Democratic Party or Liberal Democrats. These parties usually follow a liberal democratic ideology.

Active parties

Former parties

See also

*Liberal democracy

*Lib ...

MP for St Ives, and representatives of the Convention presented the Declaration to 10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street in London, also known colloquially in the United Kingdom as Number 10, is the official residence and executive office of the first lord of the treasury, usually, by convention, the prime minister of the United Kingdom. Along w ...

on 12 December 2001.

Early 21st century (2001–2009)

Ahead of the2004 European Parliament election

The 2004 European Parliament election was held between 10 and 13 June 2004 in the 25 member states of the European Union, using varying election days according to local custom. The European Parliamental parties could not be voted for, but electe ...

, MK reached an electoral partnership with the Green Party of England and Wales

The Green Party of England and Wales (GPEW; cy, Plaid Werdd Cymru a Lloegr, kw, Party Gwer Pow an Sowson ha Kembra, often simply the Green Party or Greens) is a green, left-wing political party in England and Wales. Since October 2021, Carla ...

. MK agreed not to stand its own candidates in the European election; in return, the Green Party would back MK candidates at the 2005 general election. In this latter election, MK did not contest George's seat of St Ives; in return, the Greens did not contest other seats in Cornwall. The electoral partnership was not renewed for the 2009 European Parliament election

The 2009 European Parliament election was held in the 27 member states of the European Union (EU) between 4 and 7 June 2009. A total of 736 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) were elected to represent some 500 million Europeans, making th ...

.

In August 2008 MK deputy leader, Conan Jenkin, expressed Mebyon Kernow's support for a proposed legal challenge by Cornwall 2000 over the UK Government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_est ...

's exclusion of the Cornish from the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

The Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM) is a multilateral treaty of the Council of Europe aimed at protecting the rights of minorities. It came into effect in 1998 and by 2009 it had been ratified by 39 member ...

. Cornwall 2000 need to show that they have exhausted all domestic legal avenues by having the case summarily dismissed by the High Court, the Appeal Court

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much of t ...

and the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

, before the case can be put to the European Court of Human Rights

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR or ECtHR), also known as the Strasbourg Court, is an international court of the Council of Europe which interprets the European Convention on Human Rights. The court hears applications alleging that ...

. MK requested the support of all of its members for this legal action. However the fund failed to meet the required target of £100,000 by the end of December 2008, having received just over £33,000 in pledges, and the plan was abandoned.

Unitary authority (2009–present)

In 2009, the former Cornwall County Council was replaced by the unitary authority ofCornwall Council

Cornwall Council ( kw, Konsel Kernow) is the unitary authority for Cornwall in the United Kingdom, not including the Isles of Scilly, which has its own unitary council. The council, and its predecessor Cornwall County Council, has a tradition ...

. In the first election to the new body, three MK candidates were elected: Andrew Long (Callington

Callington ( kw, Kelliwik) is a civil parish and town in east Cornwall, England, United Kingdom about north of Saltash and south of Launceston.

Callington parish had a population of 4,783 in 2001, according to the 2001 census. This had ...

), Stuart Cullimore ( Camborne South) and Dick Cole (St Enoder

St Enoder ( kw, Eglosenoder) is a civil parish and hamlet in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The hamlet is situated five miles (8 km) southeast of Newquay. There is an electoral ward bearing this name which includes St Columb Road. The populati ...

). In August 2010, an independent councillor, Neil Plummer ( Stithians), joined the MK group, citing his increasing disillusionment with the independent group. In November 2011, former chair of the party Loveday Jenkin

Loveday Elizabeth Trevenen Jenkin is a British politician, biologist and language campaigner. She has been a member of Cornwall Council since 2011, and currently serves as councillor for Crowan, Sithney and Wendron.

Biography

Jenkin is the da ...

was elected in a by-election in Wendron. In September 2012, Tamsin Williams ( Penzance Central) defected to MK from the Liberal Democrats, increasing MK's number of councillors on Cornwall Council to six.

Mebyon Kernow contested every seat in Cornwall in the 2010 general election.

In 2011, the party gained some prominence owing to the Devonwall affair; this was the proposal of a parliamentary constituency which would have been partly in Cornwall and partly in Devon. The Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Bill sought to equalise the size of constituencies in the United Kingdom. An amendment to the bill by Lord Teverson would have ensured that "all parts of Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly

The Isles of Scilly (; kw, Syllan, ', or ) is an archipelago off the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England. One of the islands, St Agnes, is the most southerly point in Britain, being over further south than the most southerly point of th ...

must be included in constituencies that are wholly in Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly"; this amendment was defeated by 250 to 221 votes in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

with 95% of Conservative and Liberal Democrat peers rejecting it. MK "accused the coalition government

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

of treating Cornwall with "absolute contempt" as a result of this, stating that Prime Minister David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron (born 9 October 1966) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2005 to 2016. He previously served as Leader o ...

and Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg

Sir Nicholas William Peter Clegg (born 7 January 1967) is a British media executive and former Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom who has been president for global affairs at Meta Platforms since 2022, having previously been vicep ...

had "devised the bill to breach the territorial integrity of Cornwall", and that it broke election promises from their parties to protect Cornish interests. Cameron replied to concerns by stating that "it's the Tamar, not the Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek mythology

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technolog ...

, for Heaven's sake"; his controversial remark was widely ridiculed in Cornwall. MK welcomed the later rejection of the parliamentary constituency boundary review, which in turn prevented the introduction of a cross-border Devonwall constituency for the 2015

File:2015 Events Collage new.png, From top left, clockwise: Civil service in remembrance of November 2015 Paris attacks; Germanwings Flight 9525 was purposely crashed into the French Alps; the rubble of residences in Kathmandu following the April ...

and 2017

File:2017 Events Collage V2.png, From top left, clockwise: The War Against ISIS at the Battle of Mosul (2016-2017); aftermath of the Manchester Arena bombing; The Solar eclipse of August 21, 2017 ("Great American Eclipse"); North Korea tests a s ...

general elections.

In 2011, Ann Trevenen Jenkin became Honorary President of MK, nine years after the last Honorary President, her husband, Richard Jenkin, had died.

In the 2013 Cornwall Council election

The Cornwall Council election, 2013, was an election for all 123 seats on the council. Cornwall Council is a unitary authority that covers the majority of the ceremonial county of Cornwall, with the exception of the Isles of Scilly which have ...

, the party was reduced to three seats. Williams did not seek re-election and MK lost her seat; MK did not win any of the newly-redrawn seats in Camborne; and Plummer unsuccessfully contested Lanner & Stithians as an independent. Only Cole and Jenkin held their seats; the party also gained a seat in Penwithick & Boscoppa. It held these seats and gained no further seats at the 2017 Cornwall Council election

The 2017 Cornwall Council election was held on 4 May 2017 as part of the 2017 local elections in the United Kingdom. 122 councillors were elected from the 121 electoral divisions of Cornwall Council, which returned either one or two councillor ...

.

MK decided not to stand candidates in the 2014 European elections, claiming the system is skewed against them winning seats.Stephen Richardson , Blog MK contested all six Cornish constituencies in the 2015 United Kingdom general election, 2015 general election. It complained against not being granted a party election broadcast: under current guidelines, it would need to stand in eighty-three constituencies outside of Cornwall in order to qualify for a broadcast. Ahead of the 2016 referendum on the issue, MK endorsed the United Kingdom's continued membership of the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

. On 23 June 2016, Cornwall voted to leave the European Union by 56.5%. Following the vote, MK reiterated its promise to campaign for a devolved Cornish Assembly.

MK declined to stand candidates in the snap 2017 general election, citing a lack of financing and resources. It also did not stand candidates in the 2019 European Parliament election

The 2019 European Parliament election was held between 23 and 26 May 2019, the ninth parliamentary election since the first direct elections in 1979. A total of 751 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) represent more than 512 million peop ...

, but its leadership endorsed the Green Party

A green party is a formally organized political party based on the principles of green politics, such as social justice, environmentalism and nonviolence.

Greens believe that these issues are inherently related to one another as a foundation f ...

because of their historic cooperation, support for a Cornish Assembly and other similar policies.

At a Policy Forum on 22 June 2018, Mebyon Kernow launched an updated version of its campaign publication titled "Towards a National Assembly of Cornwall."

Ideology and policies

MK is an advocate ofCornish nationalism

Cornish nationalism is a cultural, political and social movement that seeks the recognition of Cornwall – the south-westernmost part of the island of Great Britain – as a nation distinct from England. It is usually based on three gene ...

, seeing Cornwall as a separate nation rather than an English county

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposes Chambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

. It emphasises Cornwall's distinct Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foo ...

culture and language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

, as well as its border along the River Tamar

The Tamar (; kw, Dowr Tamar) is a river in south west England, that forms most of the border between Devon (to the east) and Cornwall (to the west). A part of the Tamar Valley is a World Heritage Site due to its historic mining activities.

T ...

, which has largely remained unchanged since 936 AD. The party's leaders identify as both Cornish and British but Cornish first. It rejects that Cornwall is a region of the United Kingdom or a county of England, preferring the label of 'duchy'. It advocates a National Curriculum for Cornwall, increased investment in the Cornish language, and a full inquiry into Cornwall's constitutional relationship with the United Kingdom.

The party advocates the establishment of a "fully devolved, democratically elected" Cornish National Assembly, established by "a dedicated, stand-alone, bespoke Act of Parliament." This would be complemented by a Cornish Civil Service. It accuses the civil service and government of "deep-seated prejudice" against Cornwall.

On economic policy, MK is left-of-centre. It rejects "austerity politics, deregulation and support for trade treaties such as TTIP

The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) was a proposed trade agreement between the European Union and the United States, with the aim of promoting trade and multilateral economic growth. According to Karel de Gucht, European ...

." It is committed against poverty and social deprivation; it advocates free and equal access to education, health and welfare services. It advocates tackling tax avoidance. It opposes the privatisation of the NHS and would renationalise railways and utilities. The party regularly highlights problems with the Cornish economy: Cornwall has lower wages and higher unemployment than the rest of the United Kingdom. MK describes its philosophy as based on being: "Cornish, Green, Left of Centre, Decentralist."

The party is environmentalist, advocating strong environmental safeguards and a "Green New Deal for Cornwall" aimed at creating jobs in the environmental sectors. It supports increasing planning restrictions to reverse the building of second homes in Cornwall. It would scrap the Trident

A trident is a three- pronged spear. It is used for spear fishing and historically as a polearm.

The trident is the weapon of Poseidon, or Neptune, the God of the Sea in classical mythology. The trident may occasionally be held by other mar ...

nuclear programme. It supports debt forgiveness for third world countries and supports the UN target of committing 0.7% of the UK's GDP as foreign aid.

The party would introduce proportional representation to UK elections through the Single Transferable Vote

Single transferable vote (STV) is a multi-winner electoral system in which voters cast a single vote in the form of a ranked-choice ballot. Voters have the option to rank candidates, and their vote may be transferred according to alternate p ...

and would abolish the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

.

MK supported the UK's membership of the European Union. It endorsed a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

on the final Brexit deal.

Cornwall is part of the South West Regional Assembly and the South West Regional Development Agency

The South West of England Regional Development Agency (SWRDA) was one of the nine Regional Development Agencies set up by the United Kingdom government in 1999. Its purpose was to lead the development of a sustainable economy in South West Engla ...

(SWRDA) administrates economic development, housing and strategic planning. MK claims that the area covered is an artificially imposed large region and not natural. Mebyon Kernow wants to break up the SWRDA into small county areas and implement a Cornish Regional Development Agency.

The party supports making Saint Piran

Saint Piran or Pyran ( kw, Peran; la, Piranus), died c. 480,Patrons - The Orthodox Church of Archangel Michael and Holy Piran'' Oecumenical Patriarchate, Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain. Laity Moor, Nr Ponsanooth, Cornwall. TR3 7H ...

's day, the day of Cornwall's patron saint, which falls on 5 March, a public holiday. It also advocates the establishment of a Cornish University.

The party has resisted proposals to reduce the number of councillors in Cornwall.

Mebyon Kernow is a member of the European Free Alliance

The European Free Alliance (EFA) is a European political party that consists of various regionalist, separatist and ethnic minority political parties in Europe. Member parties advocate either for full political independence and sovereignty, ...

. The party has close links with Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru ( ; ; officially Plaid Cymru – the Party of Wales, often referred to simply as Plaid) is a centre-left to left-wing, Welsh nationalist political party in Wales, committed to Welsh independence from the United Kingdom.

Plaid wa ...

, with whose Blaenau Gwent

Blaenau Gwent (; ) is a county borough in the south-east of Wales. It borders the unitary authority areas of Monmouthshire and Torfaen to the east, Caerphilly to the west and Powys to the north. Its main towns are Abertillery, Brynmawr, Ebbw ...

branch it cooperated in campaigns in 2000.

Organisation

MK is run on a day-to-day basis by a 20-member National Executive, which includes the leadership team, policy spokespersons, and local party representatives. Dick Cole is the current leader. The party's youth wing for under-30s is known as Kernow X.Party leaders

* Helena Charles (1951–1957) * Cecil Beer (1957–1960) * Robert Dunstone (1960–1968) * Leonard Truran (1968–1973) *Richard Jenkin

Richard Garfield Jenkin (9 October 1925 – 29 October 2002), was a Cornish nationalist politician and one of the founding members of Mebyon Kernow. He was also a Grand Bard of the Gorseth Kernow.

Cornish language

In 1947, Jenkin was made a ...

(1973–1983)

* Julyan Drew (1983–1985)

* Pedyr Prior (1985–1986)

* Loveday Carlyon

Loveday Carlyon is a Cornish nationalist politician.

Originally from Torpoint, Carlyon joined Mebyon Kernow. She married fellow party member Julyan Holmes, and moved to Liskeard. She was soon elected to the town council, and became a promine ...

(1986–1989)

* Loveday Jenkin

Loveday Elizabeth Trevenen Jenkin is a British politician, biologist and language campaigner. She has been a member of Cornwall Council since 2011, and currently serves as councillor for Crowan, Sithney and Wendron.

Biography

Jenkin is the da ...

(1990–1997)

* Dick Cole (1997–present)

Honorary presidents

* Robert Dunstone (1968–1973) * E. G. Retallack Hooper (1973–1998) *Richard Jenkin

Richard Garfield Jenkin (9 October 1925 – 29 October 2002), was a Cornish nationalist politician and one of the founding members of Mebyon Kernow. He was also a Grand Bard of the Gorseth Kernow.

Cornish language

In 1947, Jenkin was made a ...

(1998–2002)

* Ann Trevenen Jenkin (2011–)

Electoral performance

Elected representatives

MK has never won a parliamentary election to theHouse of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, nor has it ever won a seat in the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the Legislature, legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven Institutions of the European Union, institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and in ...

. Nonetheless, MK has been represented on Cornwall Council

Cornwall Council ( kw, Konsel Kernow) is the unitary authority for Cornwall in the United Kingdom, not including the Isles of Scilly, which has its own unitary council. The council, and its predecessor Cornwall County Council, has a tradition ...

since its inception in 2009, with five councillors elected in the most recent elections in 2021. It is also represented in numerous town and parish councils across Cornwall. A mixture of county and parish councillors serve as spokespeople on various topics.

MK's current elected representatives on Cornwall Council are:

Town and parish councils

In May 2007, Mebyon Kernow achieved its best-ever round of election results in Cornwall's district and town and parish councils. There were 225 district council seats up for election and MK put up 24 candidates. MK won seven district council seats, a net gain of one; seventeen town/city council seats and four parish council places, a net gain of one town/parish seat. MK polled about 5 per cent of the total votes cast in the district council elections. The seats won included their first seat onCaradon

Caradon was a local government district in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It contained five towns: Callington, Liskeard, Looe, Saltash and Torpoint, and over 80 villages and hamlets within 41 civil parishes. Its District Council was based in Lisk ...

Council for 24 years; defended their seat on North Cornwall District Council; three seats on Kerrier

Kerrier ( kw, Keryer) was a local government district in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It was the most southerly district in the United Kingdom, other than the Isles of Scilly. Its council was based in Camborne (). Other towns in the distr ...

District Council, where they lost one seat; and two on Restormel

Restormel ( kw, Rostorrmel) was a borough of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, one of the six administrative divisions that made up the county. Its council was based in St Austell; its other towns included Newquay.

The borough was named after ...

Borough Council. The results put Mebyon Kernow in third position behind the Liberal Democrats and the Conservative Party and ahead of Labour in several seats including Kerrier, Restormel, North Cornwall and Caradon. The total MK vote in the May 2007 local elections was over 10,000 votes across Cornwall. In June 2008 Mebyon Kernow's representation on Caradon increased to 3 following the defection of Glenn Renshaw (Saltash Essa) from the Lib Dems and Chris Thomas (Callington) from the Independent group, to join the party.

In the Town Council elections MK maintained groups of five councillors on both Camborne

Camborne ( kw, Kammbronn) is a town in Cornwall, England. The population at the 2011 Census was 20,845. The northern edge of the parish includes a section of the South West Coast Path, Hell's Mouth and Deadman's Cove.

Camborne was former ...

Town Council and Penzance

Penzance ( ; kw, Pennsans) is a town, civil parish and port in the Penwith district of Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is the most westerly major town in Cornwall and is about west-southwest of Plymouth and west-southwest of London. Situ ...

Town Council, with three new councillors also elected to Truro

Truro (; kw, Truru) is a cathedral city and civil parish in Cornwall, England. It is Cornwall's county town, sole city and centre for administration, leisure and retail trading. Its population was 18,766 in the 2011 census. People of Truro ...

City Council and is also represented on town councils in Callington

Callington ( kw, Kelliwik) is a civil parish and town in east Cornwall, England, United Kingdom about north of Saltash and south of Launceston.

Callington parish had a population of 4,783 in 2001, according to the 2001 census. This had ...

, Liskeard

Liskeard ( ; kw, Lyskerrys) is a small ancient stannary and market town in south-east Cornwall, South West England. It is situated approximately 20 miles (32 km) west of Plymouth, west of the Devon border, and 12 miles (20 km) eas ...

and Penryn.

In June 2011 Mebyon Kernow lost one of its Truro City councillors, and prior general election candidate, Loic Rich, who moved to the Conservative group. Rich gave as his reason; "I found it very frustrating being in a party that, along with the opposition parties, seemed to be in deliberate denial of the UK's economic and social needs." That loss was made up for in November 2011 when a Liberal Democrat

Several political parties from around the world have been called the Liberal Democratic Party or Liberal Democrats. These parties usually follow a liberal democratic ideology.

Active parties

Former parties

See also

*Liberal democracy

*Lib ...

councillor on St Austell

St Austell (; kw, Sans Austel) is a town in Cornwall, England, south of Bodmin and west of the border with Devon.

St Austell is one of the largest towns in Cornwall; at the 2011 census it had a population of 19,958.

History

St Austell ...

town council, Derek Collins, defected to MK, claiming that his former party had 'failed Cornwall'.Councillor defects to MK, claiming Lib Dems have 'failed Cornwall'Thisiscornwall.co.uk (1 November 2011). In November 2011 Eileen Carter resigned as a member of Perranzabuloe Parish Council, Perranporth Ward. In 2021, Zoe Fox, a Mebyon Kernow councillor, became Mayor of

Camborne

Camborne ( kw, Kammbronn) is a town in Cornwall, England. The population at the 2011 Census was 20,845. The northern edge of the parish includes a section of the South West Coast Path, Hell's Mouth and Deadman's Cove.

Camborne was former ...

.

Cornwall Council

From 2004 until the district councils were abolished in 2009, there were four MK councillors onKerrier

Kerrier ( kw, Keryer) was a local government district in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It was the most southerly district in the United Kingdom, other than the Isles of Scilly. Its council was based in Camborne (). Other towns in the distr ...

District Council, along with one in Restormel

Restormel ( kw, Rostorrmel) was a borough of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, one of the six administrative divisions that made up the county. Its council was based in St Austell; its other towns included Newquay.

The borough was named after ...

(the party leader Dick Cole) and, until his death in 2005, John Bolitho in North Cornwall. One of the MK councillors in Kerrier, Loveday Jenkin

Loveday Elizabeth Trevenen Jenkin is a British politician, biologist and language campaigner. She has been a member of Cornwall Council since 2011, and currently serves as councillor for Crowan, Sithney and Wendron.

Biography

Jenkin is the da ...

, joined the district council government in 2005 becoming the first MK councillor in such a position. In the final district council elections of 2007 MK won 8919 votes across the county.

In April 2009 MK leader Dick Cole announced his resignation from his job as an archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsca ...

with the new Cornwall Council

Cornwall Council ( kw, Konsel Kernow) is the unitary authority for Cornwall in the United Kingdom, not including the Isles of Scilly, which has its own unitary council. The council, and its predecessor Cornwall County Council, has a tradition ...

to become the full-time leader of Mebyon Kernow and to stand for election to the Council. He had previously worked for Cornwall County Council

Cornwall County Council ( kw, Konteth Konsel Kernow) was the county council of the non-metropolitan county of Cornwall in south west England. It came into its powers on 1 April 1889 and was abolished on 1 April 2009.

History

Cornwall County Counc ...

for 14 years, but it is not permitted for employees of Councils to stand for election to a council they work for.

On 12 May 2009, Dick Cole announced that thirty-three candidates would be standing for the party at the Cornwall Council elections

Cornwall Council in England, UK, was established in 2009 and is elected every four years. From 1973 to 2005 elections were for Cornwall County Council, with the first election for the new unitary Cornwall Council held in June 2009. This election ...

on 4 June 2009. This was the largest number of candidates that the party had ever fielded in a round of elections to a principal council

A Principal council is a local government authority carrying out statutory duties in a principal area in England and Wales.

The term “principal council” was first defined in the Local Government Act 1972, Section 270. This act created great ...

or councils. Under the new arrangements, 123 members were to be elected to the new unitary

Unitary may refer to:

Mathematics

* Unitary divisor

* Unitary element

* Unitary group

* Unitary matrix

* Unitary morphism

* Unitary operator

* Unitary transformation

* Unitary representation In mathematics, a unitary representation of a grou ...

Cornwall Council, in the place of the 82 councillors on the outgoing Cornwall County Council and another 249 on the six district councils within its area, all abolished.

Having contested thirty-three of the 123 seats on the authority, Mebyon Kernow won three, or 2.4 per cent of the total. Andrew Long was elected to represent Callington

Callington ( kw, Kelliwik) is a civil parish and town in east Cornwall, England, United Kingdom about north of Saltash and south of Launceston.

Callington parish had a population of 4,783 in 2001, according to the 2001 census. This had ...

with 54% of the votes. Stuart Cullimore was elected to represent Camborne

Camborne ( kw, Kammbronn) is a town in Cornwall, England. The population at the 2011 Census was 20,845. The northern edge of the parish includes a section of the South West Coast Path, Hell's Mouth and Deadman's Cove.

Camborne was former ...

South with 28% of the votes and Dick Cole was elected to represent St Enoder

St Enoder ( kw, Eglosenoder) is a civil parish and hamlet in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The hamlet is situated five miles (8 km) southeast of Newquay. There is an electoral ward bearing this name which includes St Columb Road. The populati ...

with 78% of the votes

Prior to the 2013 election, Mebyon Kernow held six seats on the council, having gained two due to defections from other parties, and winning one in a by-election. Three Mebyon Kernow councillors did not stand again in 2013. Keeping the seat won in the by-election, and a gain of one seat elsewhere, left them with four in total. This dropped them to being the sixth largest group on the council, from the position of fourth largest prior to the election, being overtaken by UKIP and Labour.

In the 2021 election, Mebyon Kernow fielded 19 candidates. They gained a seat despite the number of seats on the council being reduced to 87, polling 5% overall.

UK general elections

In the 2010 general election, Mebyon Kernow fielded candidates in each of the six constituencies in Cornwall. Their best result was in the St Austell & Newquay seat, where they came fourth, with 4.2% of the votes, up 4% from the previous election. The other main parties spent more on their election campaigns. MK also blamed bad results on a tactical voting campaign whereby Labour voters in Cornwall were urged to vote Liberal Democrat to stop the Conservatives from getting in. Overall they gained 1.9% of votes cast. All Mebyon Kernow candidates lost their deposits.European Parliament elections

In 1979, in the first elections to theEuropean Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the Legislature, legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven Institutions of the European Union, institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and in ...

, Mebyon Kernow's candidate Richard Jenkin

Richard Garfield Jenkin (9 October 1925 – 29 October 2002), was a Cornish nationalist politician and one of the founding members of Mebyon Kernow. He was also a Grand Bard of the Gorseth Kernow.

Cornish language

In 1947, Jenkin was made a ...

was able to attract more than five per cent of the vote in the Cornwall seat.

In April 2009 Mebyon Kernow announced that its list of candidates for the

'South West Region' seat in the European Parliament would comprise their six prospective parliamentary candidates for Westminster. The candidates were: Dick Cole (St Austell & Newquay), Conan Jenkin (Truro & Falmouth), Loveday Jenkin (Camborne & Redruth), Simon Reed (St Ives), Glenn Renshaw (South East Cornwall), Joanie Willett (North Cornwall). Mebyon Kernow had also committed itself to continue the fight for a "Cornwall only" Euro-constituency, to promote Cornwall in Europe.

Mebyon Kernow polled 14,922 votes in the 2009 European elections (11,534 votes in Cornwall, no seats, 7 per cent of the vote in Cornwall) putting them ahead of the Labour Party in Cornwall.BBC News (8 June 2009). Since 2009, MK has not stood candidates in European Parliament elections, given the difficulties of winning a seat in a constituency encompassing electorates outside Cornwall.

See also

*Cornish nationalism

Cornish nationalism is a cultural, political and social movement that seeks the recognition of Cornwall – the south-westernmost part of the island of Great Britain – as a nation distinct from England. It is usually based on three gene ...

*List of topics related to Cornwall

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Cornwall:

Cornwall – ceremonial county and unitary authority area of England within the United Kingdom. Cornwall is a peninsula bordered to the north and wes ...

*Cornish Nationalist Party

The Cornish Nationalist Party (CNP; kw, An Parti Kenethlegek Kernow) is a political party, founded by Dr James Whetter, who campaigned for independence for Cornwall.

History

It was formed by people who left Cornwall's main nationalist party Me ...

, an early splinter of MK (1975), often conflated with it.

*Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru ( ; ; officially Plaid Cymru – the Party of Wales, often referred to simply as Plaid) is a centre-left to left-wing, Welsh nationalist political party in Wales, committed to Welsh independence from the United Kingdom.

Plaid wa ...

*Scottish National Party

The Scottish National Party (SNP; sco, Scots National Pairty, gd, Pàrtaidh Nàiseanta na h-Alba ) is a Scottish nationalist and social democratic political party in Scotland. The SNP supports and campaigns for Scottish independence from th ...

* Unvaniezh Demokratel Breizh

References

* *Further reading

*External links

Mebyon Kernow website

Kernow X website

{{Authority control 1951 establishments in the United Kingdom Celtic nationalism Civic nationalism Cornish nationalism Cornish nationalist parties European Free Alliance Home rule in the United Kingdom Political parties established in 1951 Politics of Cornwall Pro-European political parties in the United Kingdom Regionalist parties in the United Kingdom Social democratic parties in the United Kingdom