Matthew Parker on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Matthew Parker (6 August 1504 – 17 May 1575) was an English

Parker was brought up in Norwich on Fye Bridge Street, now called Magdalen Street. He was possibly educated at home, and recalled later in life being taught by six men, mostly clerics. According to his biographer

Parker was brought up in Norwich on Fye Bridge Street, now called Magdalen Street. He was possibly educated at home, and recalled later in life being taught by six men, mostly clerics. According to his biographer

Parker was ordained as a

Parker was ordained as a  After being summoned to the court of

After being summoned to the court of  On 4 December 1544, on Henry's recommendation, he was elected master of Corpus Christi College. Such was his devotion towards the care of the college, he is now regarded as its second founder. Upon his election he began the process of putting organising its finances properly, which enabled him to repair the buildings and construct new ones' the master's Lodgings, the College halls and many of the students' rooms were improved. He worked hard to make Corpus Christi a centre of learning, founding new scholarships.

In January 1545, after two months in the post of master of Corpus, he was elected

On 4 December 1544, on Henry's recommendation, he was elected master of Corpus Christi College. Such was his devotion towards the care of the college, he is now regarded as its second founder. Upon his election he began the process of putting organising its finances properly, which enabled him to repair the buildings and construct new ones' the master's Lodgings, the College halls and many of the students' rooms were improved. He worked hard to make Corpus Christi a centre of learning, founding new scholarships.

In January 1545, after two months in the post of master of Corpus, he was elected

The Archbishop of Canterbury's official residence in London is

The Archbishop of Canterbury's official residence in London is  He also has a residence, named

He also has a residence, named

2

'' and '

3

'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Parker, Matthew Masters of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge 1504 births 1575 deaths 16th-century Church of England bishops Alumni of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge Archbishops of Canterbury Doctors of Divinity Clergy from Norwich Converts to Anglicanism from Roman Catholicism

bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

. He was the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

from 1559 until his death in 1575. He was also an influential theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

and arguably the co-founder (with a previous Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Hen ...

, and the theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

Richard Hooker

Richard Hooker (25 March 1554 – 2 November 1600) was an English priest in the Church of England and an influential theologian.The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church by F. L. Cross (Editor), E. A. Livingstone (Editor) Oxford University ...

) of a distinctive tradition of Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

theological thought.

Parker was one of the primary architects of the Thirty-nine Articles

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (commonly abbreviated as the Thirty-nine Articles or the XXXIX Articles) are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the ...

, the defining statements of Anglican doctrine. The Parker collection of early English manuscripts

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced i ...

, including the book of St Augustine Gospels and "Version A" of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of A ...

'', was created as part of his efforts to demonstrate that the English Church was historically independent of Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, creating one of the world's most important collections of ancient manuscripts. Along with the pioneering scholar Lawrence Nowell

Laurence (or Lawrence) Nowell (1530 – c.1570) was an English antiquarian, cartographer and pioneering scholar of Anglo-Saxon language and literature.

Life

Laurence Nowell was born around 1530 in Whalley, Lancashire, the second son of Alexand ...

, Parker's work concerning the Old English literature

Old English literature refers to poetry and prose written in Old English in early medieval England, from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066, a period often termed Anglo-Saxon England. The 7th-century work '' Cædmo ...

laid the foundation for Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened wit ...

studies.

Early years (15041525)

Matthew Parker, the eldest son of William and Alice Parker, was born inNorwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the Episcopal see, See of ...

in St Saviour's parish on 6 August 1504; he was one of six children, and the third son and eldest surviving child. His father was a wealthy worsted

Worsted ( or ) is a high-quality type of wool yarn, the fabric made from this yarn, and a yarn weight category. The name derives from Worstead, a village in the English county of Norfolk. That village, together with North Walsham and Aylsham ...

weaver and the grandson of Nicholas Parker, registrar to successive archbishops of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

between 1450 and 1483. His mother Alice Monins was originally from Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

; she may have been related by marriage to Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Hen ...

, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1533 to 1555. William Parker died in about 1516, and within three or four years following his death, Alice Parker married John Baker. Their son, also called John, was later nominated as one of Parker's executors. Matthew Parker's surviving siblings were Botolph (who became a priest), Thomas (who during his life became Mayor of Norwich) and Margaret. Their mother died in 1553.

Parker was brought up in Norwich on Fye Bridge Street, now called Magdalen Street. He was possibly educated at home, and recalled later in life being taught by six men, mostly clerics. According to his biographer

Parker was brought up in Norwich on Fye Bridge Street, now called Magdalen Street. He was possibly educated at home, and recalled later in life being taught by six men, mostly clerics. According to his biographer John Strype

John Strype (1 November 1643 – 11 December 1737) was an English clergyman, historian and biographer from London. He became a merchant when settling in Petticoat Lane. In his twenties, he became perpetual curate of Theydon Bois, Essex and lat ...

,

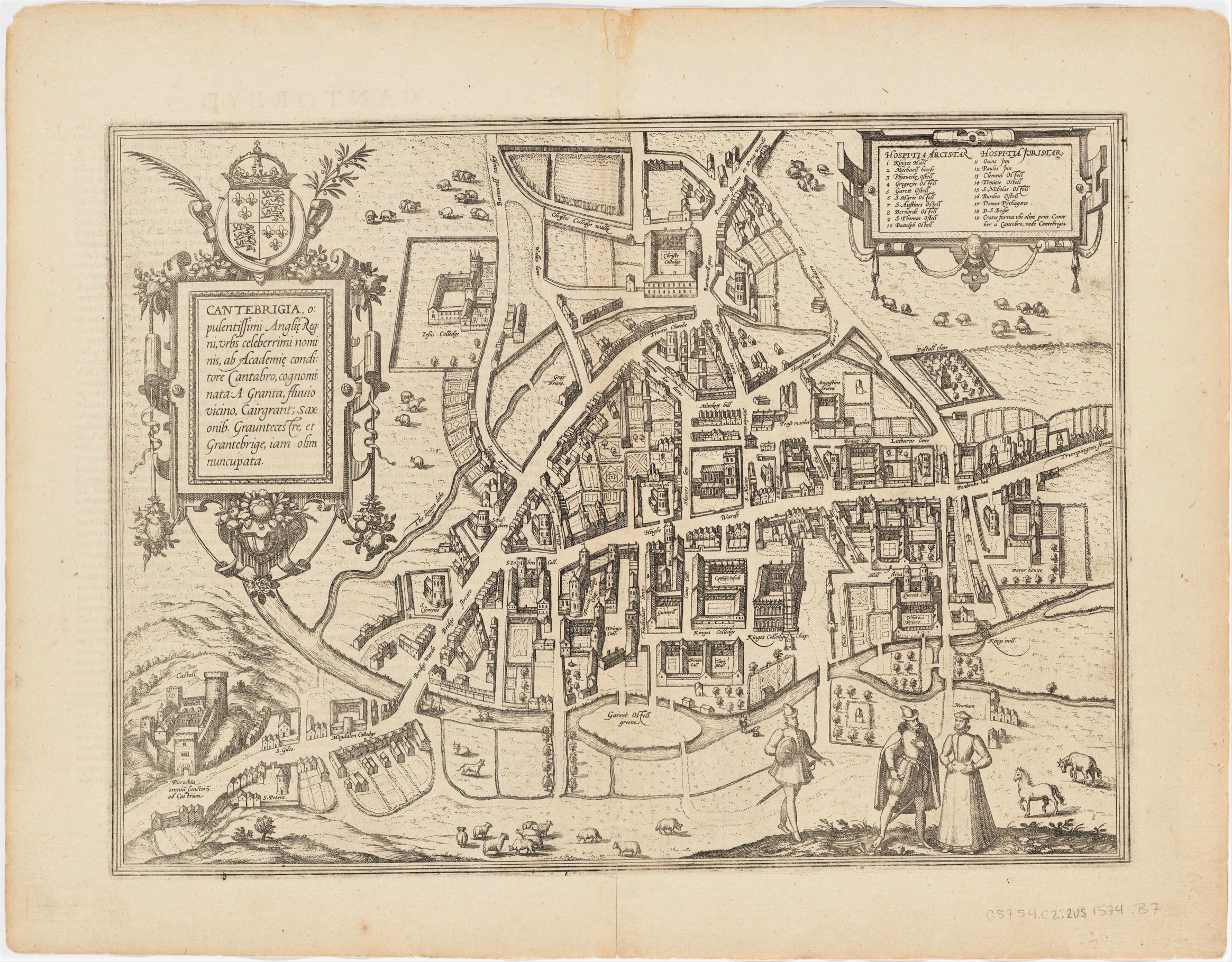

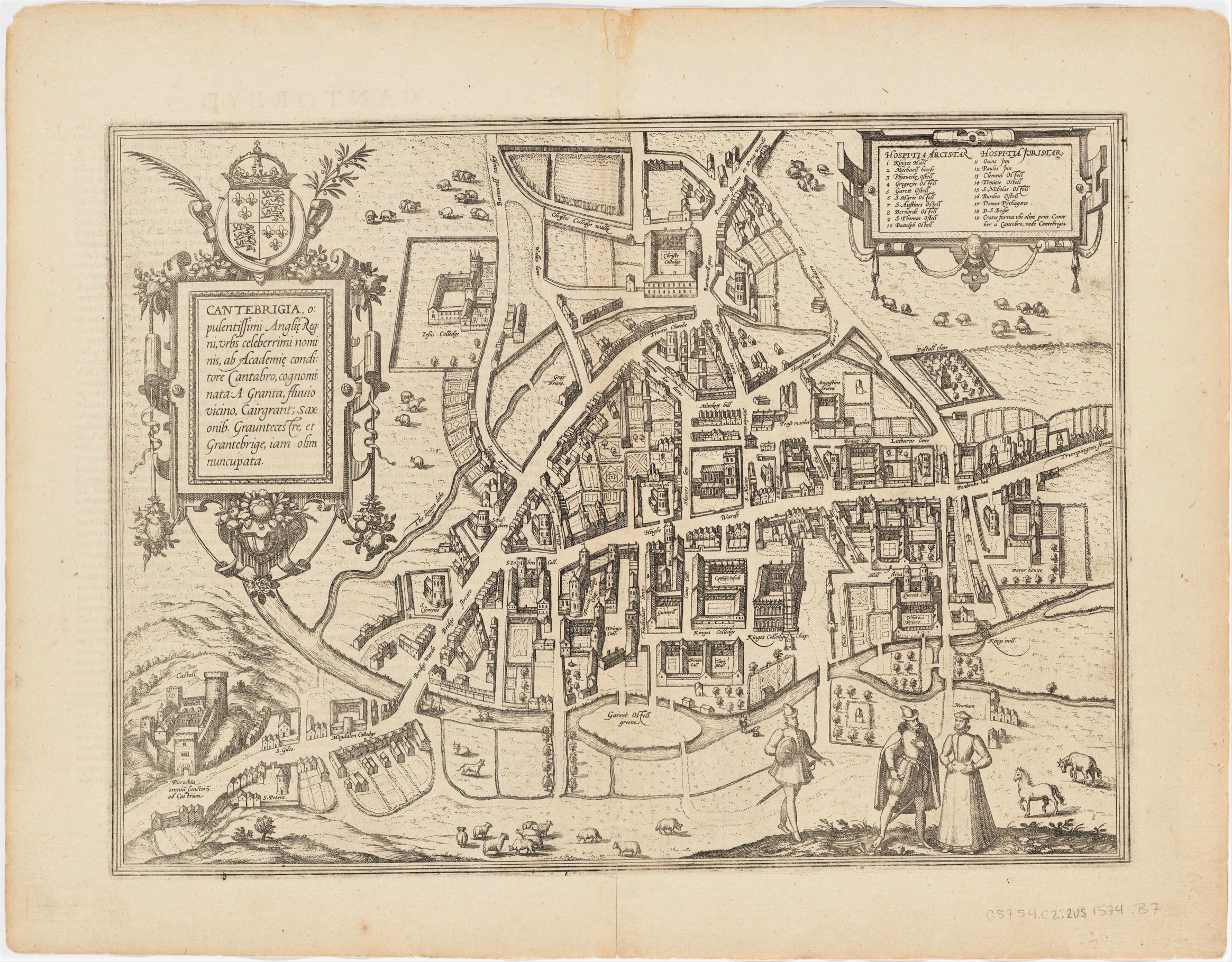

In 1520, the 16-year-old Parker went up to Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, where he studied at , now known as Corpus Christi College under Richard Cowper. On March 20, 1520, after six months at the college, he obtained a scholarship and became the Bible clerk at , and so was able to move from St Mary's Hostel to rooms in the college. At Cambridge he was able to read the works of Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

. and had access to books by married theologians from the Continent — he first commended clerical marriage

Clerical marriage is practice of allowing Christian clergy (those who have already been ordained) to marry. This practice is distinct from allowing married persons to become clergy. Clerical marriage is admitted among Protestants, including both A ...

when he was a student there. He was associated with the circle of Thomas Bilney

Thomas Bilney ( 149519 August 1531) was an English Christian martyr.

Early life

Thomas Bilney was born around 1495 in Norfolk, most likely in Norwich. Nothing is known of his parents except that they outlived him. He entered Trinity Hall, ...

, remaining loyal to him throughout their university days together. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

degree in 1525.

Career at Cambridge (15251547)

Parker was ordained as a

Parker was ordained as a deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

on 20 April 1527 and a priest two months later, on 15 June. In September he was elected a fellow

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

of Corpus Christi. There is no evidence that he was ever involved in a public dispute at Cambridge, unlike his contemporaries. Bilney was accused of heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

in 1527 and then recanted, but was imprisoned for two years. He returned to Cambridge, regretting his recantation, and began to preach throughout Norfolk. In August 1531 he was condemned to be burnt at the stake

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an execution and murder method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment f ...

as a relapsed heretic; Parker was present at his execution in Norwich on 19 August, and afterwards defended Bilney after accusations were made that he had recanted at the stake.

In around 1527, Parker was one of the Cambridge scholars whom Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**'' Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**'' Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, t ...

Thomas Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic bishop. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's Lord High Almoner, almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and by 1514 he had become the ...

invited to Cardinal College

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. Parker, like Cranmer, declined Wolsey's invitation. The college had been founded in 1525 on the site of St Frideswide's Priory, and was will still being built when Wolsey fell from power in 1529.

Parker began his Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

degree in 1528. He was licensed to preach by Cranmer in 1533, and quickly became a popular preacher in and around Cambridge; none of his sermons have survived. He would have had to adhere to the '' Ten Articles'' enforced on the clergy during that period.

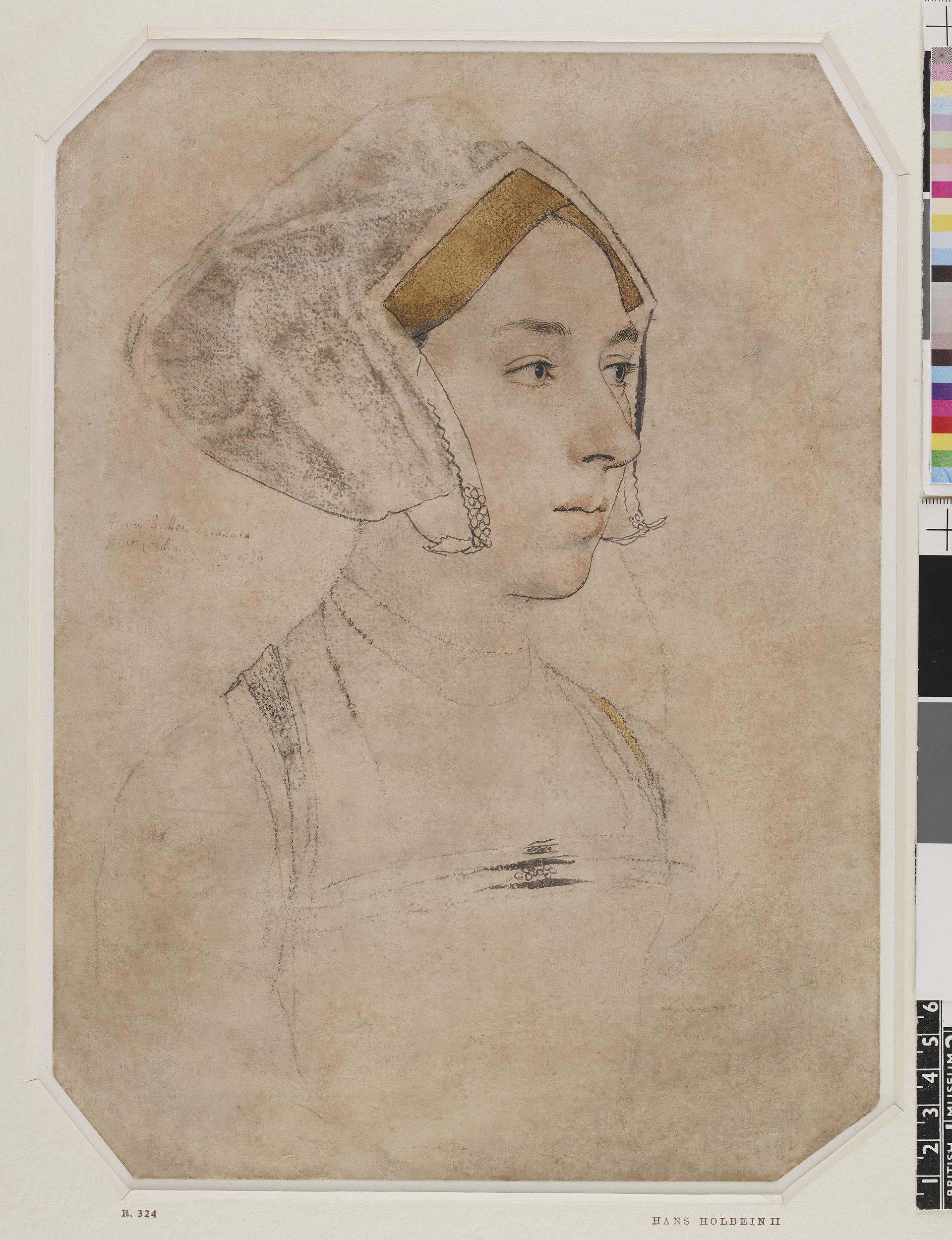

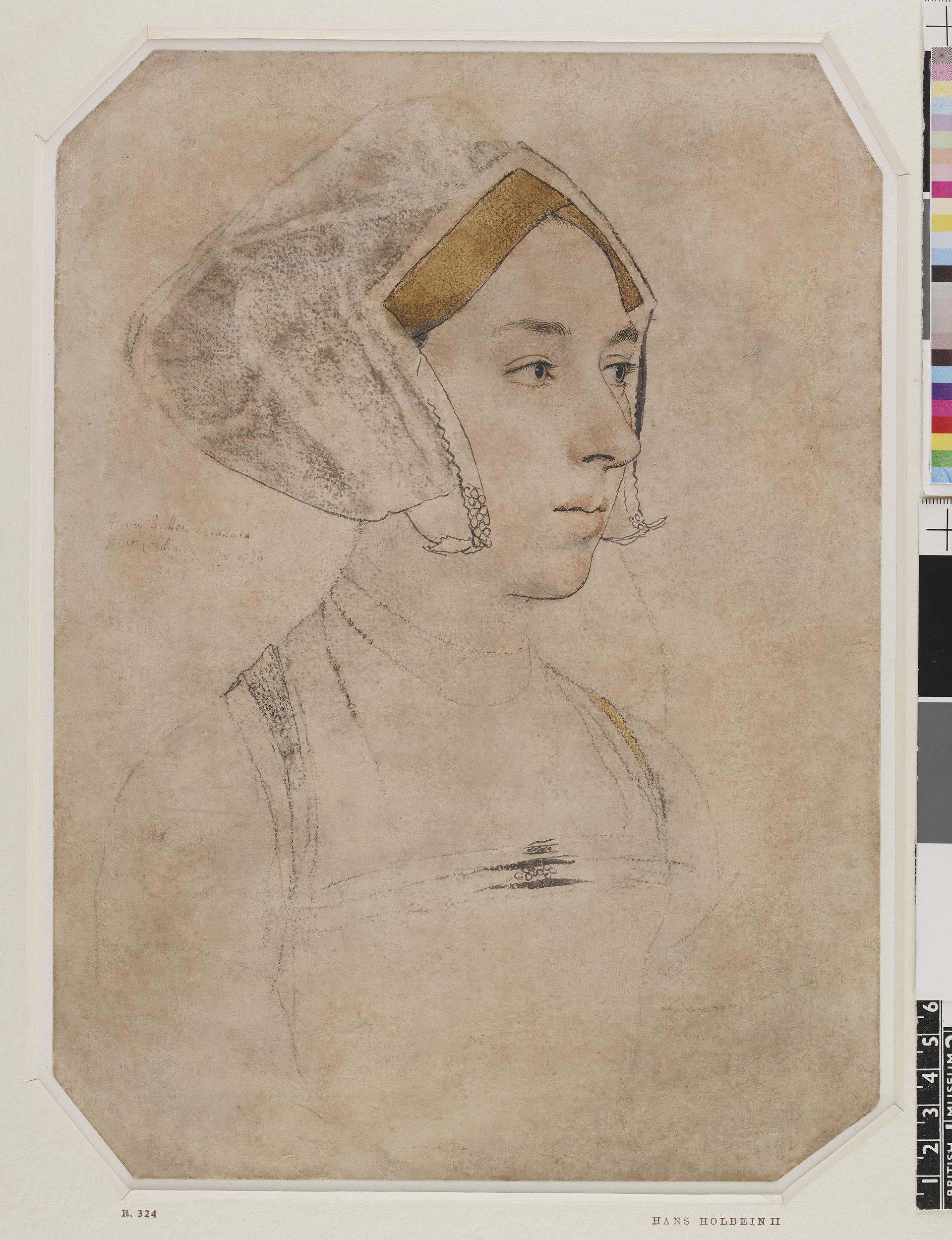

After being summoned to the court of

After being summoned to the court of Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key f ...

he became her chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intelligence ...

. Through her influence he was appointed dean

Dean may refer to:

People

* Dean (given name)

* Dean (surname), a surname of Anglo-Saxon English origin

* Dean (South Korean singer), a stage name for singer Kwon Hyuk

* Dean Delannoit, a Belgian singer most known by the mononym Dean

Titles

* ...

of the college of secular canons at Stoke-by-Clare

Stoke-by-Clare is a small village and civil parish in Suffolk located in the valley of the River Stour, about two miles west of Clare.

In 1124 Richard de Clare, 1st Earl of Hertford, moved the Benedictine Priory that had been established at ...

in Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include ...

in 1535, a post he held until 1547. The college had been secularised in 1514. The duties of the residents involved the regular performance of the offices of the Church and prayers for the founder's family, but little direction was provided in the statutes for other times during the day, and there was little to do for the residents beyond their daily tasks and the education of the choirboy

A choirboy is a boy member of a choir, also known as a treble.

As a derisive slang term, it refers to a do-gooder or someone who is morally upright, in the same sense that "Boy Scout" (also derisively) refers to someone who is considered honora ...

s. It had come close to be acquired by Wolsey, but this had been prevented by the intervention of the Bishop of Norwich

The Bishop of Norwich is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Norwich in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers most of the county of Norfolk and part of Suffolk. The bishop of Norwich is Graham Usher.

The see is in t ...

and Henry VIII's first wife, Catherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and other variations are feminine names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria.

In the early Christ ...

.

He retained his fellowship at Cambridge University whilst he was dean at Stoke-by-Clare. His biographer V.J.K. Brook commented that for Parker "his new post provided him with a happy and quiet place of retirement in the country to which he became devoted"; and allowed him to pursue his enthusiasm for education and the sponsorship of new buildings. At Stoke he transformed the college by introducing new statutes to ensure regular preaching occurred. Under Parker's deanship, scholars came from Cambridge to deliver lectures, greater care was taken over the education of the boy choristers, and a free grammar school for local boys was built within the precincts. His successful revitalisation of the college caused its reputation to spread, and he was able to protect it from being dissolved by citing the good work being done there; it retained its status until after Henry's death in 1547.

Shortly before Anne Boleyn's arrest in 1536, she charged her daughter Elizabeth to Parker's care, something he honoured for the rest of his life. He obtained his Bachelor of Divinity

In Western universities, a Bachelor of Divinity or Baccalaureate in Divinity (BD or BDiv; la, Baccalaureus Divinitatis) is a postgraduate academic degree awarded for a course taken in the study of divinity or related disciplines, such as theolog ...

in July 1535, and in 1537 was appointed chaplain to Henry; he graduated Doctor of Divinity

A Doctor of Divinity (D.D. or DDiv; la, Doctor Divinitatis) is the holder of an advanced academic degree in divinity.

In the United Kingdom, it is considered an advanced doctoral degree. At the University of Oxford, doctors of divinity are ran ...

in July 1538.

In 1539 he was denounced to the Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

, Thomas Audley by his opponents at Stoke-by-Clare, who accused him of heresy and using "disloyal language against Easter, relics and other details". Audley dismissed the charges and urged Parker to "go on and fear no such enemies". In 1541 was appointed to the second prebend

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of t ...

at Ely, a sign of royal approval.

On 4 December 1544, on Henry's recommendation, he was elected master of Corpus Christi College. Such was his devotion towards the care of the college, he is now regarded as its second founder. Upon his election he began the process of putting organising its finances properly, which enabled him to repair the buildings and construct new ones' the master's Lodgings, the College halls and many of the students' rooms were improved. He worked hard to make Corpus Christi a centre of learning, founding new scholarships.

In January 1545, after two months in the post of master of Corpus, he was elected

On 4 December 1544, on Henry's recommendation, he was elected master of Corpus Christi College. Such was his devotion towards the care of the college, he is now regarded as its second founder. Upon his election he began the process of putting organising its finances properly, which enabled him to repair the buildings and construct new ones' the master's Lodgings, the College halls and many of the students' rooms were improved. He worked hard to make Corpus Christi a centre of learning, founding new scholarships.

In January 1545, after two months in the post of master of Corpus, he was elected vice-chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth and former Commonwealth nations, the chancellor ...

of the university. During his year in office he got into some trouble with the Chancellor of Cambridge University, Stephen Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner (27 July 1483 – 12 November 1555) was an English Catholic bishop and politician during the English Reformation period who served as Lord Chancellor during the reign of Queen Mary I and King Philip.

Early life

Gardiner was ...

, over a play, ''Pammachius'', performed by the students and censored by the college, which derided the old ecclesiastical system. Parker was obliged to make enquiries into the nature of the play, but then allowed to settle the matter himself on behalf of the university authorities.

Career under Edward VI

On the passing of theAct of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of parliame ...

in 1545 enabling the king to dissolve chantries

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area i ...

and colleges, Parker was appointed one of the commissioners for Cambridge, and their report may have saved its colleges from destruction. Stoke, however, was dissolved in the following reign, and Parker received a generous pension. He took advantage of the new reign to marry in June 1547, before clerical marriages were legalised by Parliament and Convocation, Margaret, daughter of Robert Harlestone, a Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

squire. They had initially planned to marry since about 1540 but had waited until it was not a felony for priests to marry. The marriage was a happy one, although Queen Elizabeth's dislike of Margaret was later to cause Parker much distress. They had five children, of whom John and Matthew reached adulthood. During Kett's Rebellion

Kett's Rebellion was a revolt in Norfolk, England during the reign of Edward VI, largely in response to the enclosure of land. It began at Wymondham on 8 July 1549 with a group of rebels destroying fences that had been put up by wealthy landowners ...

, he preached at the rebels' camp on Mousehold Hill near Norwich, without much effect, and later encouraged his secretary, Alexander Neville

Alexander Neville ( 1340–1392) was a late medieval prelate who served as Archbishop of York from 1374 to 1388.

Life

Born in about 1340, Alexander Neville was a younger son of Ralph Neville, 2nd Baron Neville de Raby and Alice de Audley. He ...

, to write his history of the rising.

Parker's association with Protestantism

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

advanced with the times, and he received higher promotion under John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1504Loades 2008 – 22 August 1553) was an English general, admiral, and politician, who led the government of the young King Edward VI from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady J ...

, than under the moderate Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset (150022 January 1552) (also 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp), also known as Edward Semel, was the eldest surviving brother of Queen Jane Seymour (d. 1537), the third wife of King Henry VI ...

. At Cambridge, he was a friend of the German Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

reformer Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer ( early German: ''Martin Butzer''; 11 November 1491 – 28 February 1551) was a German Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg who influenced Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican doctrines and practices. Bucer was originally a me ...

after he was exiled to England, and preached Bucer's funeral sermon in 1551. In 1552 he was promoted to the rich deanery of Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

.

Demotion during the reign of Mary

In July 1553 he supped with Northumberland at Cambridge, when the duke marched north on his hopeless campaign against the accession of Mary Tudor. As a supporter of Northumberland and a married man, under the new regime, Parker was deprived of his deanery, his mastership of Corpus Christi and his other preferments. However, he survived Mary's reign without leaving the country – a fact that would not have endeared him to the more ardent Protestants who went into exile and idealised those who were martyred by Mary. Parker respected authority, and when his time came he could consistently impose authority on others. He was not eager to assume this task, and made great efforts to avoid promotion to Archbishop of Canterbury, which Elizabeth designed for him as soon as she had succeeded to the throne.Archbishop of Canterbury (1559–1575)

Elizabeth wanted a moderate man, so she chose Parker on the recommendations ofWilliam Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley

William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley (13 September 15204 August 1598) was an English statesman, the chief adviser of Queen Elizabeth I for most of her reign, twice Secretary of State (1550–1553 and 1558–1572) and Lord High Treasurer from 1 ...

, her chief adviser. There was also an emotional attachment. Parker had been the favourite chaplain of Elizabeth's mother, the queen Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key f ...

. Before Anne was arrested in 1536 she had entrusted Elizabeth's spiritual well-being to Parker. A few days afterwards Anne was executed following charges of adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

, incest

Incest ( ) is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by affinity ( marriage or stepfamily), ado ...

and treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

. Parker also possessed all the qualifications Elizabeth expected from an archbishop, except celibacy

Celibacy (from Latin ''caelibatus'') is the state of voluntarily being unmarried, sexually abstinent, or both, usually for religious reasons. It is often in association with the role of a religious official or devotee. In its narrow sense, th ...

. Elizabeth had a strong prejudice against married clergy, and in addition, she seems to have disliked Margaret Parker personally, often treating her so rudely that her husband was "in horror to hear it". After a visit to Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament, on the opposit ...

, the Queen duly thanked her hostess but maliciously asked how she should address her, "For Madam I may not call you, mistress I should be ashamed to call you."

Parker was elected on 1 August 1559 but, given the turbulence and executions that had preceded Elizabeth's accession, it was difficult to find the requisite four bishops willing and qualified to consecrate

Consecration is the solemn dedication to a special purpose or service. The word ''consecration'' literally means "association with the sacred". Persons, places, or things can be consecrated, and the term is used in various ways by different grou ...

him, and not until 19 December was the ceremony performed at Lambeth by William Barlow, formerly Bishop of Bath and Wells

The Bishop of Bath and Wells heads the Church of England Diocese of Bath and Wells in the Province of Canterbury in England.

The present diocese covers the overwhelmingly greater part of the (ceremonial) county of Somerset and a small area of D ...

, John Scory

John Scory (died 1585) was an English Dominican friar who later became a bishop in the Church of England.

He was Bishop of Rochester from 1551 to 1552, and then translated to Bishop of Chichester from 1552 to 1553. He was deprived of this positi ...

, formerly Bishop of Chichester

The Bishop of Chichester is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Chichester in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers the counties of East and West Sussex. The see is based in the City of Chichester where the bishop's sea ...

, Miles Coverdale

Myles Coverdale, first name also spelt Miles (1488 – 20 January 1569), was an English ecclesiastical reformer chiefly known as a Bible translator, preacher and, briefly, Bishop of Exeter (1551–1553). In 1535, Coverdale produced the first c ...

, formerly Bishop of Exeter

The Bishop of Exeter is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Exeter in the Province of Canterbury. Since 30 April 2014 the ordinary has been Robert Atwell.

, and John Hodgkins, Bishop of Bedford

The Bishop of Bedford is an episcopal title used by a Church of England suffragan bishop who, under the direction of the Diocesan Bishop of St Albans, oversees 150 parishes in Luton and Bedfordshire.

The title, which takes its name after the to ...

. The allegation of an indecent consecration at the Nag's Head public house seems first to have been made by a Jesuit, Christopher Holywood

Christopher Holywood (1559 – 4 September 1626) was an Irish Jesuit of the Counter Reformation. The origin of the Nag's Head Fable has been traced to him.

Roman Catholic and Irish

His family, which draws its name from Holywood, a village ne ...

, in 1604, and has since been discredited. Parker's consecration was, however, legally valid only by the plenitude of the Royal Supremacy

The Acts of Supremacy are two acts passed by the Parliament of England in the 16th century that established the English monarchs as the head of the Church of England; two similar laws were passed by the Parliament of Ireland establishing the Eng ...

approved by the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

and reluctantly by a vote of the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

21–18; the Edwardine Ordinal, which was used, had been repealed by Mary Tudor and not re-enacted by the parliament of 1559.

Parker mistrusted popular enthusiasm, and he wrote in horror of the idea that "the people" should be the reformers of the church. He was convinced that if ever Protestantism was to be firmly established in England at all, some definite ecclesiastical forms and methods must be sanctioned to secure the triumph of order over anarchy, and he vigorously set about the repression of what he thought a mutinous individualism incompatible with a catholic spirit.

He was not an inspiring leader and no dogma or prayer book is associated with his name. However, the English composer Thomas Tallis

Thomas Tallis (23 November 1585; also Tallys or Talles) was an English composer of High Renaissance music. His compositions are primarily vocal, and he occupies a primary place in anthologies of English choral music. Tallis is considered one o ...

contributed '' Nine Tunes for Archbishop Parker's Psalter'' which bears his name. The 55 volumes published by the Parker Society The Parker Society was a text publication society set up in 1841 to produce editions of the works of the early Protestant writers of the English Reformation. It was supported by both the High Church and evangelical wings of the Church of England, an ...

include only one by its eponymous hero, and that is a volume of correspondence. He was a disciplinarian, a scholar, a modest and moderate man of genuine piety and irreproachable morals.

Probably his most famous saying, prompted by the arrival of Mary Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Sco ...

in England, was "I fear our good Queen has the wolf by the ears."

Dispute about the validity of his consecration in 1559

Parker's consecration gave rise to a dispute, which continues to this day, in regard to its sacramental validity from the perspective of the Catholic Church. This eventually led to the condemnation of Anglican orders as "absolutely null and utterly void" by a papal commission in 1896. The commission could not dispute that consecration had taken place which met all the legal andliturgical

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

requirement or deny that a "manual" succession, that is, the consecration by the laying on of hands and prayer had taken place. Rather the Pope asserted in the condemnation that the "defect of form and intent" rendered the rite insufficient to make a bishop in the apostolic succession (according to the Catholic understanding of the minima for validity). Specifically the English rite was considered to be defective in "form", i.e. in the words of the rite which did not mention the "intention" to create a sacrificing bishop considered to be a priest in a higher degree, and the absence of a certain "matter" such as the handing of the chalice and paten to the ordinand to symbolise the power to offer sacrifice.

The Church of England archbishops of Canterbury and York rejected the Pontiff's arguments in ''Saepius Officio'' in 1897. This rebuttal was written to demonstrate the sufficiency of the form and intention used in the Anglican Ordinal: the archbishops wrote that in the preface to the Ordinal the intention clearly is stated to continue the existing holy orders as received. They stated that even if Parker's consecrators had private doubts or lacked intention to do what the rites of ordination clearly stated, it counted for nought, since the words and actions of a rite (the formularies) performed on behalf of the church by the ministers of the sacrament, and not the opinions, however erroneous or correct, or inner states of mind or moral condition of the actors who carry them out, are the sole determinants. This view is also held by the Catholic Church (and others) with few exceptions since the 3rd century. Likewise, according to the archbishops, the required references to the sacrificial priesthood never existed in any ancient Catholic ordination liturgies prior to the 9th century nor in certain current Eastern-rite ordination liturgies that the Catholic Church considers valid nor in Orthodoxy. Also, the archbishops argued that a particular formula in this respect as a ''sine qua non'' made no difference to the substance or validity of the act since the only two components that all ordination rites had in common were prayer and the laying on of hands, and in this regard, the words in the Anglican rite itself gave sufficient evidence as to the intent of the participants as stated in the preface, words and action of the rite. They pointed out that the only fixed and sure sacramental formulary is the baptismal rite. They argued that it was not necessary to consecrate a bishop as a "sacrificing priest" since he already was one by virtue of being a priest, except in ordinations ''per saltim'', i.e. from deacon to bishop when the person was made priest and bishop at once, a practice discontinued and forbidden. They also pointed out that none of the priests ordained with the English Ordinal were re-ordained as a requirement by Queen Mary - some did so voluntarily and some were re-anointed, a practice common at the time., On the contrary, the Queen, unhappy about married clergy, ordered all of them, estimated at 15% of the total at the beginning of her reign in 1553, to put their wives away. Parker was ordained in 1527 in the Latin Rite and before the break with Rome. As such according to this rite he was a "sacrificing priest" to which nothing more could be added by being consecrated a bishop. The orders of the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the sec ...

were also condemned as part of the wider denunciation of Anglican orders.

In regard to the legal and canonical requirements, the government was at pains to see all were met for the consecration. None of the 18 Marian bishops would agree to consecrate Parker. Not only were they opposed to the changes the bishops had been excluded from decision-making regarding changes in liturgy, doctrine and the Royal Supremacy. The Commons approved the changes and the Lords 21-18 approved after pressure was brought to bear on them; concessions were made in a more Catholic tone in eucharistic doctrine, and allowance made for the use of Mass vestments and other traditional clerical dress in use in the second year of the reign of Edward VI, i.e. January 1548 to 49, when the Latin Rite was still the legal form of worship (the 'Ornaments Rubric' in the 1559 Prayer Book seems to refer to the allowance as set forth in the 1549 BCP).

The government recruited four bishops who had been retired by Queen Mary or gone into exile. Two of the four, William Barlow and John Hodgkins had in Rome's view valid orders, since, having been made bishops in 1536 and 1537 with the Roman Pontifical in the Latin Rite, their consecrations met the criteria according to the definition stated in ''Apostolicae Curae''. John Scory and Miles Coverdale, the other two consecrators, were consecrated with the English Ordinal of 1550 on the same day in 1551 by Cranmer, Hodgkins and Ridley who were consecrated with the Latin Rite in 1532, 1537 and 1547 respectively. This ordinal was considered defective in form and intention. All four of Parker's consecrators were consecrated by bishops who themselves had been consecrated with the Roman Pontifical in the Church of England which at the time was in schism from Rome. Even though two of the consecrators had orders recognised as validity by Rome the consecration was considered to be "null and void" by Rome because the ordinal used was judged to be defective in matter, form and intention.

In the first year of his archiepiscopate, Parker participated in the consecration of 11 new bishops and confirmed two who had been ordained in previous reigns.

Later years

Parker avoided involvement in secular politics and was never admitted to Elizabeth'sPrivy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

. Ecclesiastical politics gave him considerable trouble. Some of the evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

reformers wanted liturgical

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

changes and at least the option not to wear certain clerical vestments

Vestments are liturgical garments and articles associated primarily with the Christian religion, especially by Eastern Churches, Catholics (of all rites), Anglicans, and Lutherans. Many other groups also make use of liturgical garments; th ...

, if not their complete prohibition. Early presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

wanted no bishops, and the conservatives opposed all these changes, often preferring to move in the opposite direction toward the practices of the Henrician church. The Queen herself begrudged episcopal privilege until she eventually recognised it as one of the chief bulwarks of royal supremacy. To Parker's consternation, the queen refused to add her ''imprimatur

An ''imprimatur'' (sometimes abbreviated as ''impr.'', from Latin, "let it be printed") is a declaration authorizing publication of a book. The term is also applied loosely to any mark of approval or endorsement. The imprimatur rule in the R ...

'' to his attempts to secure conformity, though she insisted that he achieve this goal. Thus Parker was left to stem the rising tide of Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

feeling with little support from Parliament, convocation

A convocation (from the Latin '' convocare'' meaning "to call/come together", a translation of the Greek ἐκκλησία ''ekklēsia'') is a group of people formally assembled for a special purpose, mostly ecclesiastical or academic.

In a ...

or the Crown.

The bishops' ''Interpretations and Further Considerations'', issued in 1560, tolerated a lower vestments

Vestments are liturgical garments and articles associated primarily with the Christian religion, especially by Eastern Churches, Catholics (of all rites), Anglicans, and Lutherans. Many other groups also make use of liturgical garments; th ...

standard than was prescribed by the rubric of 1559, but it fell short of the desires of the anti-vestment clergy such as Coverdale (one of the bishops who had consecrated Parker) who made a public display of their nonconformity in London.

The ''Book of Advertisements

The Book of Advertisements was a series of enactments concerning Anglican ecclesiastical matters, drawn up by Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury (1559-1575), with the help of Edmund Grindal, Robert Horne, Richard Cox, and Nicholas Bullingh ...

'', which Parker published in 1566 to check the anti-vestments faction, had to appear without specific royal sanction; and the ''Reformatio legum ecclesiasticarum'', which John Foxe

John Foxe (1516/1517 – 18 April 1587), an English historian and martyrologist, was the author of '' Actes and Monuments'' (otherwise ''Foxe's Book of Martyrs''), telling of Christian martyrs throughout Western history, but particularly the s ...

published with Parker's approval, received neither royal, parliamentary or synodical authorisation. Parliament even contested the claim of the bishops to determine matters of faith. "Surely", said Parker to Peter Wentworth

Sir Peter Wentworth (1529–1596) was a prominent Puritan leader in the Parliament of England. He was the elder brother of Paul Wentworth and entered as member for Barnstaple in 1571. He later sat for the Cornish borough of Tregony in 1578 an ...

, "you will refer yourselves wholly to us therein." "No, by the faith I bear to God", retorted Wentworth, "we will pass nothing before we understand what it is; for that were but to make you popes. Make you popes who list, for we will make you none."

Disputes about vestments had expanded into a controversy over the whole field of church government and authority. Parker died on 17 May 1575, lamenting that Puritan ideas of "governance" would "in conclusion undo the Queen and all others that depended upon her". By his personal conduct, he had set an ideal example for Anglican priests.

He is buried in the chapel of Lambeth Palace. Matthew Parker Street, near Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, is named after him.

Residences

The Archbishop of Canterbury's official residence in London is

The Archbishop of Canterbury's official residence in London is Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament, on the opposit ...

.

He also has a residence, named

He also has a residence, named The Old Palace

Stari dvor ( sr-cyr, Стари двор, lit. "Old Palace") was the royal residence of the Obrenović dynasty. Today it houses the City Assembly of Belgrade. The palace is located on the corner of Kralja Milana and Dragoslava Jovanovića stree ...

, next to Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, Kent, is one of the oldest and most famous Christian structures in England. It forms part of a World Heritage Site. It is the cathedral of the Archbishop of Canterbury, currently Justin Welby, leader of the ...

on the site of the medieval Archbishop's Palace.

Scholarship

Parker's historical research was exemplified in his ''De antiquitate Britannicæ ecclesiae'', and his editions ofAsser

Asser (; ; died 909) was a Welsh monk from St David's, Dyfed, who became Bishop of Sherborne in the 890s. About 885 he was asked by Alfred the Great to leave St David's and join the circle of learned men whom Alfred was recruiting for his ...

, Matthew Paris

Matthew Paris, also known as Matthew of Paris ( la, Matthæus Parisiensis, lit=Matthew the Parisian; c. 1200 – 1259), was an English Benedictine monk, chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts and cartographer, based at St Albans Abbey ...

(1571), Thomas Walsingham

Thomas Walsingham (died c. 1422) was an English chronicler, and is the source of much of the knowledge of the reigns of Richard II, Henry IV and Henry V, and the careers of John Wycliff and Wat Tyler.

Walsingham was a Benedictine monk who ...

, and the compiler known as Matthew of Westminster Matthew of Westminster, long regarded as the author of the ''Flores Historiarum'', is now thought never to have existed.

The error was first discovered in 1826 by Francis Turner Palgrave, who said that Matthew was "a phantom who never existed," and ...

(1571). ''De antiquitate Britannicæ ecclesiæ'' was probably printed at Lambeth in 1572, where the archbishop is said to have had an establishment of printers, engravers, and illuminators.

Parker gave the English people the ''Bishops' Bible

The Bishops' Bible is an English translation of the Bible which was produced under the authority of the established Church of England in 1568. It was substantially revised in 1572, and the 1602 edition was prescribed as the base text for the ...

'', which was undertaken at his request, prepared under his supervision, and published at his expense in 1572. Much of his time and labour from 1563 to 1568 was given to this work. He had also the principal share in drawing up the ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

'', for which his skill in ancient liturgies peculiarly fitted him. His liturgical skill was also shown in his version of the psalter

A psalter is a volume containing the Book of Psalms, often with other devotional material bound in as well, such as a liturgical calendar and litany of the Saints. Until the emergence of the book of hours in the Late Middle Ages, psalters w ...

. It was under his presidency that the Thirty-nine Articles

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (commonly abbreviated as the Thirty-nine Articles or the XXXIX Articles) are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the ...

were finally reviewed and subscribed by the clergy (1562).

Parker published in 1567 an old ''Saxon Homily on the Sacrament'', by Ælfric of Eynsham. He published ''A Testimonie of Antiquitie Showing the Ancient Fayth in the Church of England Touching the Sacrament of the Body and Bloude of the Lord'' to prove that transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (Latin: ''transubstantiatio''; Greek: μετουσίωσις '' metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and of ...

was not the doctrine of the ancient English Church. Parker collaborated with his secretary John Joscelyn

John Joscelyn, also John Jocelyn or John Joscelin, (1529–1603) was an English clergyman and antiquarian as well as secretary to Matthew Parker, an Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I of England. Joscelyn was involved ...

in his manuscript studies.

Manuscript collection

Parker left a priceless collection ofmanuscripts

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced i ...

, largely collected from former monastic

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic ...

libraries, to his college at Cambridge. Bevill has documented the manuscript transcriptions conducted under Parker. The Parker Library at Corpus Christi bears his name and houses most of his collection, with some volumes in the Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University Library is the main research library of the University of Cambridge. It is the largest of the over 100 libraries within the university. The Library is a major scholarly resource for the members of the University of Cambri ...

. The Parker Library on the Web

Parker Library on the Web is a multi-year undertaking of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, the Stanford University Libraries and the Cambridge University Library, to produce a high-resolution digital copy of every imageable page in the 538 manuscr ...

project has made digital images of all of these manuscripts available online.

Works

* * * * * * * *See also

*Tunes for Archbishop Parker's Psalter

In 1567 English composer Thomas Tallis contributed nine tunes for Archbishop Parker's Psalter, a collection of vernacular psalm settings intended for publication in a metrical psalter then being compiled for the Archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew ...

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * Volumes '2

'' and '

3

'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Parker, Matthew Masters of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge 1504 births 1575 deaths 16th-century Church of England bishops Alumni of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge Archbishops of Canterbury Doctors of Divinity Clergy from Norwich Converts to Anglicanism from Roman Catholicism

Matthew

Matthew may refer to:

* Matthew (given name)

* Matthew (surname)

* ''Matthew'' (ship), the replica of the ship sailed by John Cabot in 1497

* ''Matthew'' (album), a 2000 album by rapper Kool Keith

* Matthew (elm cultivar), a cultivar of the Chi ...

Deans of Lincoln

Vice-Chancellors of the University of Cambridge

Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

16th-century Anglican theologians