Mary Wigman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

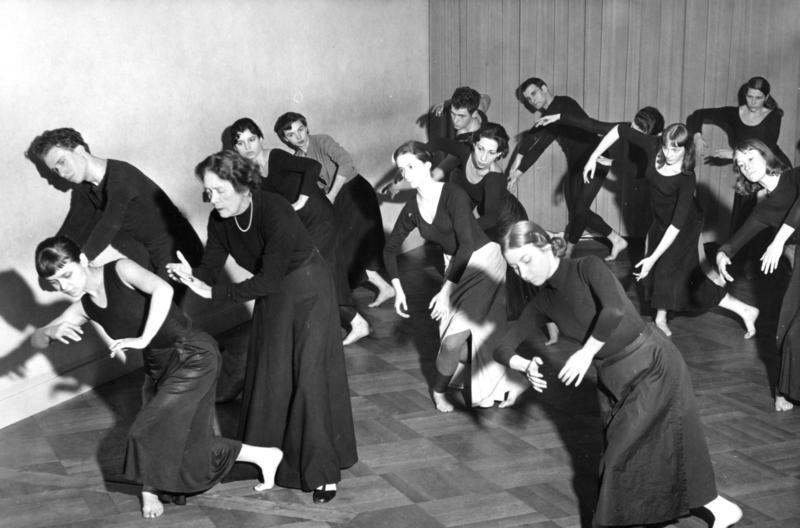

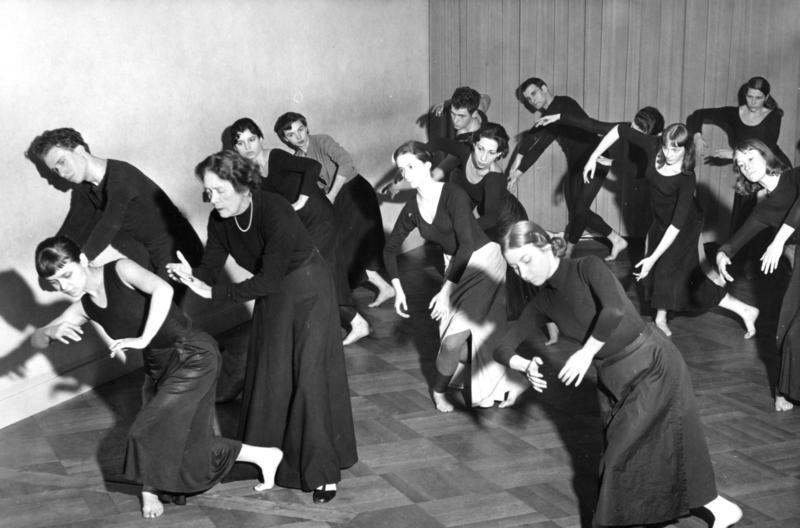

Mary Wigman (born Karoline Sophie Marie Wiegmann; 13 November 1886 – 18 September 1973) was a German dancer and

Karoline Sophie Marie Wiegmann was born in

Karoline Sophie Marie Wiegmann was born in

The Jaques-Dalcroze school's practice made dance secondary to music, so Wigman decided to take her interests elsewhere. In 1913, on advice from the German-Danish expressionist painter Emil Nolde, she entered the Rudolf von Laban School for Art (''Schule für Kunst'') on Monte Verità in the Swiss canton of

The Jaques-Dalcroze school's practice made dance secondary to music, so Wigman decided to take her interests elsewhere. In 1913, on advice from the German-Danish expressionist painter Emil Nolde, she entered the Rudolf von Laban School for Art (''Schule für Kunst'') on Monte Verità in the Swiss canton of

In 1920, Wigman was offered the post of ballet mistress at the Saxon State Opera in Dresden, but, after taking up residence in a hotel in Dresden and beginning to teach dance classes while awaiting her anticipated appointment, she learned that the position had been awarded to someone else. In the same year, Wigman together with her assistant Bertha Trümpy, opened a school for modern dance on ''Bautzner Strasse'' in Dresden.Prof. Dr. Karl Toepfer, Prof. Dr. Peter Reichel, Dr. Gabriele Postuwka, Frank-Manuel Peter

In 1920, Wigman was offered the post of ballet mistress at the Saxon State Opera in Dresden, but, after taking up residence in a hotel in Dresden and beginning to teach dance classes while awaiting her anticipated appointment, she learned that the position had been awarded to someone else. In the same year, Wigman together with her assistant Bertha Trümpy, opened a school for modern dance on ''Bautzner Strasse'' in Dresden.Prof. Dr. Karl Toepfer, Prof. Dr. Peter Reichel, Dr. Gabriele Postuwka, Frank-Manuel Peter

, Dr. Yvonne Hardt, Dr. Thomas Kupsch, Cathleen Bürgelt, Muriel Favre, Heide Lazarus (2003) ''Selection of documents about The Wigman School, Dresden, from the period of 1924 to 1937''] , Deutsches Tanzarchiv Köln, SK Stiftung Kultur (SK Culture Foundation) During Wigman's time in Dresden, Wigman had contacts with the city's lively art scene, for example with the German expressionist painter

Wigman ceaselessly created and choreographed new solo dances, including ''Tänze der Nacht'', ''Der Spuk'', ''Vision'' (all 1920), ''Tanzrhythmen I and II'', ''Tänze des Schweigens'' (all 1920–23), ''Die abendlichen Tänze'' (1924), ''Visionen'' (1925), ''Helle Schwingungen'' (1927), ''Schwingende Landschaft'' (1929) and ''Das Opfer'' (1931). Group dances were titled ''Die Feier I'' (1921), ''Die sieben Tänze des Lebens'' (1921), ''Szenen aus einem Tanzdrama'' (1923/24), ''Raumgesänge'' (1926), ''Die Feier II'' (1927/28) and ''Der Weg'' (1932).

In 1930 Wigman worked at the Munich Dancers' Congress as a choreographer and dancer in the choir work ''Das Totenmal'' created by in honour of the dead of World War I. By 1927, Wigman had 360 students in Dresden alone, and more than 1,200 students were taught at branches operated by former students in Berlin, Frankfurt, Chemnitz, Riesa, Hamburg, Leipzig, Erfurt, Magdeburg, Munich, and Freiburg, including from 1931 one in New York City by former student

Wigman ceaselessly created and choreographed new solo dances, including ''Tänze der Nacht'', ''Der Spuk'', ''Vision'' (all 1920), ''Tanzrhythmen I and II'', ''Tänze des Schweigens'' (all 1920–23), ''Die abendlichen Tänze'' (1924), ''Visionen'' (1925), ''Helle Schwingungen'' (1927), ''Schwingende Landschaft'' (1929) and ''Das Opfer'' (1931). Group dances were titled ''Die Feier I'' (1921), ''Die sieben Tänze des Lebens'' (1921), ''Szenen aus einem Tanzdrama'' (1923/24), ''Raumgesänge'' (1926), ''Die Feier II'' (1927/28) and ''Der Weg'' (1932).

In 1930 Wigman worked at the Munich Dancers' Congress as a choreographer and dancer in the choir work ''Das Totenmal'' created by in honour of the dead of World War I. By 1927, Wigman had 360 students in Dresden alone, and more than 1,200 students were taught at branches operated by former students in Berlin, Frankfurt, Chemnitz, Riesa, Hamburg, Leipzig, Erfurt, Magdeburg, Munich, and Freiburg, including from 1931 one in New York City by former student

Joan Woodbury

Another student and protegee of Wigman, Margret Dietz, taught in America from 1953 to 1972. During this time, Wigman's style was characterized by critics as "tense, introspective, and sombre," yet there was always an element of "radiance found even in her darkest compositions."

The seizure of power by the

The seizure of power by the

After 1945 Wigman began again with a

After 1945 Wigman began again with a

Wigman gave her first public performance in Munich in February 1914, performing two of her own dances, including one called ''Lento'' and the first version of ''Hexentanz'' (Witch Dance), which later became one of her most important works.

While recovering from her nervous breakdown, in 1918, Wigman wrote the choreography for her first group composition, ''Die sieben Tänze des Lebens'' (The Seven Dances of Life), which premiered several years later, in 1921. After that her career and influence began in earnest.

In 1925 the Italian financier

Wigman gave her first public performance in Munich in February 1914, performing two of her own dances, including one called ''Lento'' and the first version of ''Hexentanz'' (Witch Dance), which later became one of her most important works.

While recovering from her nervous breakdown, in 1918, Wigman wrote the choreography for her first group composition, ''Die sieben Tänze des Lebens'' (The Seven Dances of Life), which premiered several years later, in 1921. After that her career and influence began in earnest.

In 1925 the Italian financier

Wigman's former student Katharine Sehnert still teaches dance technique and improvisation based on the Wigman style. In

Wigman's former student Katharine Sehnert still teaches dance technique and improvisation based on the Wigman style. In

"Moving bodies and political movement: Dance in German modernism"

dissertation,

"Mary Wigman and German Modern Dance: A Modernist Witch?"

''Forum for Modern Language Studies'', Oxford University Press (1 October 2007), 43(4): 427–437. Special Issue on Stagecraft and Witchcraft. *Toepfer, Karl Eric (1997). ''Empire of Ecstasy: Nudity and Movement in Germany Body Culture, 1910–1935 (Weimer and Now: German Cultural Criticism, No 13)'', University of California Press. . *Wigman, Mary (1975). '' The Mary Wigman Book: Her Writings'', Olympic Marketing Corp. .

a student of Wigman's.

Photographs of Mary WigmanMary Wigman-Schule in Dresden

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wigman, Mary 1886 births 1973 deaths Dance teachers Expressionist choreographers Expressionist dancers German women choreographers German female dancers Modern dancers Dancers from Berlin People from Hanover

choreographer

Choreography is the art or practice of designing sequences of movements of physical bodies (or their depictions) in which motion or form or both are specified. ''Choreography'' may also refer to the design itself. A choreographer is one who c ...

, notable as the pioneer of expressionist dance

''Expressive dance'' from German ''Ausdruckstanz'', is a form of artistic dance in which the individual and artistic presentation (and sometimes also processing) of feelings is an essential part. It emerged as a counter-movement to classi ...

, dance therapy

Dance/movement therapy (DMT) in USA/ Australia or dance movement psychotherapy (DMP) in the UK is the psychotherapeutic use of movement and dance to support intellectual, emotional, and motor functions of the body. As a modality of the creativ ...

, and movement training without pointe shoes

A pointe shoe (, ), also called a ballet toe shoe or simply toe shoe, is a type of shoe worn by ballet dancers when performing pointe work. Pointe shoes were conceived in response to the desire for dancers to appear weightless and sylph-like and ...

. She is considered one of the most important figures in the history of modern dance

Modern dance is a broad genre of western concert or theatrical dance which included dance styles such as ballet, folk, ethnic, religious, and social dancing; and primarily arose out of Europe and the United States in the late 19th and early 20th ...

. She became one of the most iconic figures of Weimar German culture and her work was hailed for bringing the deepest of existential

Existentialism ( ) is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the problem of human existence and centers on human thinking, feeling, and acting. Existentialist thinkers frequently explore issues related to the meaning, purpose, and valu ...

experiences to the stage.

Early life

Karoline Sophie Marie Wiegmann was born in

Karoline Sophie Marie Wiegmann was born in Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

, Province of Hanover

The Province of Hanover (german: Provinz Hannover) was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia and the Free State of Prussia from 1868 to 1946.

During the Austro-Prussian War, the Kingdom of Hanover had attempted to maintain a neutral position ...

in the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

. Wiegmann was the daughter of a bicycle dealer. Already as a child she was called Mary, "because the Hanoverians were once kings of England and the House of Welf

The House of Welf (also Guelf or Guelph) is a European dynasty that has included many German and British monarchs from the 11th to 20th century and Emperor Ivan VI of Russia in the 18th century. The originally Franconian family from the Meus ...

pride never quite got over the decline of the Kingdom of Hanover

The Kingdom of Hanover (german: Königreich Hannover) was established in October 1814 by the Congress of Vienna, with the restoration of George III to his Hanoverian territories after the Napoleonic era. It succeeded the former Electorate of Ha ...

to a Prussian province.

Development of expressionist dance, early career

Wigman spent her youth in Hanover, England, the Netherlands and Lausanne. Wigman came to dance comparatively late after seeing three students ofÉmile Jaques-Dalcroze

Émile Jaques-Dalcroze (6 July 1865 – 1 July 1950) was a Swiss composer, musician, and music educator who developed Dalcroze eurhythmics, an approach to learning and experiencing music through movement. Dalcroze eurhythmics influenced Carl O ...

, who aimed to approach music through movement using three equally important elements: solfège

In music, solfège (, ) or solfeggio (; ), also called sol-fa, solfa, solfeo, among many names, is a music education method used to teach aural skills, pitch and sight-reading of Western music. Solfège is a form of solmization, though the tw ...

, improvisation

Improvisation is the activity of making or doing something not planned beforehand, using whatever can be found. Improvisation in the performing arts is a very spontaneous performance without specific or scripted preparation. The skills of impr ...

and his own system of movements—Dalcroze eurhythmics

Dalcroze eurhythmics, also known as the Dalcroze method or simply eurhythmics, is one of several developmental approaches including the Kodály method, Orff Schulwerk and Suzuki Method used to teach music to students. Eurhythmics was develope ...

. Wigman studied rhythmic gymnastics in Hellerau

Hellerau is a northern quarter ''(Stadtteil)'' in the city of Dresden, Germany, slightly south of Dresden Airport. It was the first garden city in Germany. The northern section of Hellerau absorbed the village of Klotzsche, where some 18th cent ...

from 1910–1911 with Émile Jaques-Dalcroze and Suzanne Perrottet

Suzanne Perrottet (13 September 1889 – 10 August 1983) was a Swiss dancer, musician, and movement teacher. Trained in music and dance, Perrottet ran the Bewegungsschule Suzanne Perrottet and was a member of the faculty at the École Polytechn ...

, but felt artistically dissatisfied there: Like Suzanne Perrottet, Mary Wigman was also looking for movements independent of music and independent physical expression. After that, she stayed in Rome and Berlin. Another key early experience was a solo concert by Grete Wiesenthal.

The Jaques-Dalcroze school's practice made dance secondary to music, so Wigman decided to take her interests elsewhere. In 1913, on advice from the German-Danish expressionist painter Emil Nolde, she entered the Rudolf von Laban School for Art (''Schule für Kunst'') on Monte Verità in the Swiss canton of

The Jaques-Dalcroze school's practice made dance secondary to music, so Wigman decided to take her interests elsewhere. In 1913, on advice from the German-Danish expressionist painter Emil Nolde, she entered the Rudolf von Laban School for Art (''Schule für Kunst'') on Monte Verità in the Swiss canton of Ticino

Ticino (), sometimes Tessin (), officially the Republic and Canton of Ticino or less formally the Canton of Ticino,, informally ''Canton Ticino'' ; lmo, Canton Tesin ; german: Kanton Tessin ; french: Canton du Tessin ; rm, Chantun dal Tessin . ...

. Laban was significantly involved in the development of modern expressive dance (Labanotation

Labanotation (the grammatically correct form "Labannotation" or "Laban notation" is uncommon) is a system for analyzing and recording human movement. The inventor was Rudolf von Laban (1879-1958), a central figure in European modern dance, who ...

). She enrolled in one of Laban's summer courses and was instructed in his technique.Mary Wigman Facts. (2010). http://biography.yourdictionary.com/mary-wigman Following their lead, she worked upon a technique based on contrasts of movement; expansion and contraction, pulling and pushing. She continued with the Laban school through the Swiss summer sessions and the Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and ...

winter sessions until 1919.

In Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and ...

, Wigman showed her first public dances ''Hexentanz I'', ''Lento'' and ''Ein Elfentanz''. During the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

she stayed in Switzerland with Laban as his assistant and taught in Zurich and Ascona

300px, Ascona

Ascona ( lmo, label= Ticinese, Scona ) is a municipality in the district of Locarno in the canton of Ticino in Switzerland.

It is located on the shore of Lake Maggiore.

The town is a popular tourist destination and holds the yea ...

. In 1917 Wigman offered three different programs in Zurich, including ''Der Tänzer unserer lieben Frau'', ''Das Opfer'', ''Tempeltanz'', ''Götzendienst'' and four Hungarian dances according to Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped wit ...

. In 1918, Wigman suffered a nervous breakdown. Wigman performed this program again in Zurich in 1919 and later in Germany. Only the performances in Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

and Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

brought her the big breakthrough.

Weimar Republic period

, Dr. Yvonne Hardt, Dr. Thomas Kupsch, Cathleen Bürgelt, Muriel Favre, Heide Lazarus (2003) ''Selection of documents about The Wigman School, Dresden, from the period of 1924 to 1937''] , Deutsches Tanzarchiv Köln, SK Stiftung Kultur (SK Culture Foundation) During Wigman's time in Dresden, Wigman had contacts with the city's lively art scene, for example with the German expressionist painter

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (6 May 1880 – 15 June 1938) was a German expressionist painter and printmaker and one of the founders of the artists group Die Brücke or "The Bridge", a key group leading to the foundation of Expressionism in 20th-century ...

. Rivalry and competition between Wigman's new school and the old schools of dance in Dresden would emerge, later especially with former students and teachers of the Palucca School of Dance

The Palucca University of Dance Dresden (german: Palucca Hochschule für Tanz Dresden), formerly the Palucca School Dresden, is a dance school in Dresden, Germany, founded in 1925 by the dancer and pedagogue Gret Palucca who taught until 1990. ...

. From 1921 the first performances took place with Wigman's dance group. Film recordings of the dance group made in 1923 in the Berlin Botanical Garden with excerpts from ''Szenen aus einem Tanzdrama'' were used in the 1925 German cultural silent film '' Ways to Strength and Beauty'' (''Wege zu Kraft und Schönheit''). For a long time, the school on ''Bautzner Strasse'' in Dresden was a rehearsal stage for the Saxon State Opera in Dresden. When the school moved under the name "''Semper Zwei''" next to the opera house, the state capital of Dresden bought the property and in 2019 gave it to the association Villa Wigman for Dance (''Villa Wigman für Tanz e. V.''), which uses it as a rehearsal and performance centre for the independent dance scene.

Wigman's most famous male student was Harald Kreutzberg

Harald Kreutzberg (December 11, 1902 – April 25, 1968) was a German dancer and choreographer associated with the Ausdruckstanz movement, a form in which the individual, artistic expression of feelings or emotions is essential. Though largely f ...

. Famous students included Gret Palucca

Gret Palucca (born Margarethe Paluka; 8 January 1902 – 22 March 1993) was a German dancer and dance teacher, notable for her dance school, the Palucca School of Dance, founded in Dresden in 1925.

Life and work

Margarethe Paluka was born in M ...

, Hanya Holm

Hanya Holm (born Johanna Eckert; 3 March 1893 – 3 November 1992) is known as one of the "Big Four" founders of American modern dance. She was a dancer, choreographer, and above all, a dance educator.

Early life, connection with Mary Wigman

B ...

, Yvonne Georgi

Yvonne Georgi (29 October 1903 – 25 January 1975) was a German dancer, choreographer and ballet mistress. She was known for her comedic talents and her extraordinary jumping ability. In her roles as a dancer, choreographer, and ballet mistres ...

, Margherita Wallmann

Margarete Wallmann or Wallman (aka Margarethe Wallmann, Margherita Wallman or Margarita Wallmann) (22 June or July 1901 or 1904 – 2 May 1992)

was a ballerina, choreographer, stage designer, and opera director.

Life and career

Born probably ...

, Lotte Goslar

Lotte Goslar (27 February 1907 – 16 October 1997) was a German-American dancer.

Life

Born in Dresden, Goslar came from a banking family and worked towards a career as a dancer from an early age. She took lessons with Mary Wigman and Gret Pa ...

, Birgit Åkesson, Sonia Revid, and Hanna Berger. Dore Hoyer

Dore Hoyer (12 December 1911 – 31 December 1967) was a German expressionist dancer and choreographer. She is credited as "one of the most important solo dancers of the Ausdruckstanz tradition." Inspired by Mary Wigman, she developed her own sol ...

, who further developed the expressive dance of Wigman and Palucca, worked together with Wigman on several occasions but was never her student. Student Irena Linn taught Wigman's ideas in the United States at Boston Conservatory and in Tennessee. Ursula Cain was also one of Wigman's students.

On tour, Wigman travelled throughout Germany and neighbouring countries with her chamber dance group. In 1928 Wigman performed for the first time in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

and in 1930 in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

. In the 1920s, Wigman was the idol of a movement that wanted dance free of being subordinate to music. Wigman rarely danced to music not composed for her. It was often only danced to the accompaniment of gongs or drums and in rare cases without any music at all, which was particularly popular in intellectual circles.

Selected works choreographed and dance school success

Wigman ceaselessly created and choreographed new solo dances, including ''Tänze der Nacht'', ''Der Spuk'', ''Vision'' (all 1920), ''Tanzrhythmen I and II'', ''Tänze des Schweigens'' (all 1920–23), ''Die abendlichen Tänze'' (1924), ''Visionen'' (1925), ''Helle Schwingungen'' (1927), ''Schwingende Landschaft'' (1929) and ''Das Opfer'' (1931). Group dances were titled ''Die Feier I'' (1921), ''Die sieben Tänze des Lebens'' (1921), ''Szenen aus einem Tanzdrama'' (1923/24), ''Raumgesänge'' (1926), ''Die Feier II'' (1927/28) and ''Der Weg'' (1932).

In 1930 Wigman worked at the Munich Dancers' Congress as a choreographer and dancer in the choir work ''Das Totenmal'' created by in honour of the dead of World War I. By 1927, Wigman had 360 students in Dresden alone, and more than 1,200 students were taught at branches operated by former students in Berlin, Frankfurt, Chemnitz, Riesa, Hamburg, Leipzig, Erfurt, Magdeburg, Munich, and Freiburg, including from 1931 one in New York City by former student

Wigman ceaselessly created and choreographed new solo dances, including ''Tänze der Nacht'', ''Der Spuk'', ''Vision'' (all 1920), ''Tanzrhythmen I and II'', ''Tänze des Schweigens'' (all 1920–23), ''Die abendlichen Tänze'' (1924), ''Visionen'' (1925), ''Helle Schwingungen'' (1927), ''Schwingende Landschaft'' (1929) and ''Das Opfer'' (1931). Group dances were titled ''Die Feier I'' (1921), ''Die sieben Tänze des Lebens'' (1921), ''Szenen aus einem Tanzdrama'' (1923/24), ''Raumgesänge'' (1926), ''Die Feier II'' (1927/28) and ''Der Weg'' (1932).

In 1930 Wigman worked at the Munich Dancers' Congress as a choreographer and dancer in the choir work ''Das Totenmal'' created by in honour of the dead of World War I. By 1927, Wigman had 360 students in Dresden alone, and more than 1,200 students were taught at branches operated by former students in Berlin, Frankfurt, Chemnitz, Riesa, Hamburg, Leipzig, Erfurt, Magdeburg, Munich, and Freiburg, including from 1931 one in New York City by former student Hanya Holm

Hanya Holm (born Johanna Eckert; 3 March 1893 – 3 November 1992) is known as one of the "Big Four" founders of American modern dance. She was a dancer, choreographer, and above all, a dance educator.

Early life, connection with Mary Wigman

B ...

. The engineer and Siemens

Siemens AG ( ) is a German multinational conglomerate corporation and the largest industrial manufacturing company in Europe headquartered in Munich with branch offices abroad.

The principal divisions of the corporation are ''Industry'', ''E ...

manager helped Wigman part-time with the administration of this large organization and also became her life partner between 1930 and 1941. Wigman has been photographed dancing and in portraits by many well-known photographers, including Hugo Erfurth

Hugo Erfurth (14 October 1874 – 14 February 1948) was a German photographer known for his portraits of celebrities and cultural figures of the early twentieth century.

Life Early years

Erfurth was born in Halle (Saale), in what was then t ...

, , Albert Renger-Patzsch

Albert Renger-Patzsch (June 22, 1897 – September 27, 1966) was a German photographer associated with the New Objectivity.

Biography

Renger-Patzsch was born in Würzburg and began making photographs by age twelve. After military service in the F ...

and Siegfried Enkelmann. The commemorative stamp of the German Federal Post shown here is based on a photo by Albert Renger-Patzsch. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (6 May 1880 – 15 June 1938) was a German expressionist painter and printmaker and one of the founders of the artists group Die Brücke or "The Bridge", a key group leading to the foundation of Expressionism in 20th-century ...

created the painting ''Totentanz der Mary Wigman'' (Mary Wigman's Dance of Death) in the mid-1920s.

United States tour

Wigman toured the United States in 1930 with her dance company, and again in 1931 and 1933. A Wigman school was founded by her disciples in New York City in 1931 and her work through dance and movement contributed as a gateway for social change with theNew Dance Group

New Dance Group, or more casually NDG, is a performing arts organization in New York City, United States.

History

New Dance Group was established in 1932 by a group of artists and choreographers dedicated to social change through dance and movem ...

in the 1930s, this group was started by students from Wigman's New York school. Wigman's work in the United States is credited to her protegee Hanya Holm

Hanya Holm (born Johanna Eckert; 3 March 1893 – 3 November 1992) is known as one of the "Big Four" founders of American modern dance. She was a dancer, choreographer, and above all, a dance educator.

Early life, connection with Mary Wigman

B ...

, and then to Holm's students Alwin Nikolais

Alwin Nikolais (November 25, 1910 – May 8, 1993) was an American choreographer, dancer, composer, musician, teacher. He had created the Nikolais Dance Theatre, and was best known for his self-designed innovative costume, lighting and production d ...

anJoan Woodbury

Another student and protegee of Wigman, Margret Dietz, taught in America from 1953 to 1972. During this time, Wigman's style was characterized by critics as "tense, introspective, and sombre," yet there was always an element of "radiance found even in her darkest compositions."

Dance under National Socialism

The seizure of power by the

The seizure of power by the National Socialists

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

in 1933 had an immediate effect on Wigman's school through the new law against racial overcrowding in German schools and universities of 25 April 1933 ('). Wigman initially obtained an exemption by allowing her "5% pupils of non-Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ...

descent" for the course from September 1933. However, in the course of the following years, a number of Wigman's students were forced to emigrate, such as the Jewish Berlin prima ballerina Ruth Abramovitsch Sorel Ruth Elly Abramovitsch Sorel (18 June 1907 - 1 April 1974) was a German choreographer, dancer, artistic director and teacher. She spent the first half of her career working mainly in Europe (particularly Warsaw) and then was predominantly active in ...

and member of Wigman's dance company Pola Nirenska

Pola Nirenska (28 July 1910 — 25 July 1992), born Pola Nirensztajn, was a Polish performer of modern dance. She had a critically acclaimed if brief career in Austria, Germany, Italy, and Poland in the 1930s before fleeing the continent in 1935 ...

, whom Wigman had organized to perform at a school audition in 1935 and teacher for a summer course, whereupon Wigman was accused of "friendliness toward Jews" in 1935 and 1937. The Wigman school became a member of the Militant League for German Culture

The English word ''militant'' is both an adjective and a noun, and it is generally used to mean vigorously active, combative and/or aggressive, especially in support of a cause, as in "militant reformers". It comes from the 15th century Latin ...

(''Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur'') in 1933. Wigman took over the local group leadership of the "Department of gymnastics and dance" (''Fachschaft Gymnastik und Tanz'') in the National Socialist Teachers League

The National Socialist Teachers League (German: , NSLB), was established on 21 April 1929. Its original name was the Organization of National Socialist Educators. Its founder and first leader was former schoolteacher Hans Schemm, the Gauleiter ...

in 1933–1934, but noted for example "Local group meeting – sickening!" in her diary. With ''Schicksalslied'' (1935) and ''Herbstliche Tänze'' (1937) further solo dances were created.

The Nazi press had criticized some of the 1934 dances by Wigman and other choreographers, for being insufficiently or unimpressively German, the 1935 ''Rogge'' and ''Wernicke'' works were lauded as appropriate examples of "heroic" German bodily movement, but Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

apparently disliked ''Amazonen'' for being too Greek in its iconography. In 1936 Wigman choreographed the ''Totenklage'' with a group of 80 dancers for the Olympic Youth festival to mark the opening of the 1936 Summer Olympics

The 1936 Summer Olympics (German: ''Olympische Sommerspiele 1936''), officially known as the Games of the XI Olympiad (German: ''Spiele der XI. Olympiade'') and commonly known as Berlin 1936 or the Nazi Olympics, were an international multi-s ...

in Berlin.

In 1942 Wigman sold her school in Dresden. She received a guest teaching contract at the dance department of the University of Music and Theatre Leipzig

The University of Music and Theatre "Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy" Leipzig (german: Hochschule für Musik und Theater "Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy" Leipzig) is a public university in Leipzig (Saxony, Germany). Founded in 1843 by Felix Mendelssohn ...

, where the concert pianist Heinz K. Urban accompanied her as a répétiteur. In the same year, Wigman appeared for the last time as a solo dancer with ''Abschied und Dank'' (Farewell and Thanks).

German dance festivals and Goebbels Nazi propaganda

Amidst the fall ofWeimar Germany

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is als ...

to Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

, Wigman's contributions to modern dance existed within the umbrella of Nazism and the rejection of structured dance (ballet) in favor of “freer” movements. Marion Kant writes in “Dance is a Race Question: The Dance politics of the Reich Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda” that Wigman's dance style became a means through which Nazi ideologies were propagated. Describing Nazi perceptions of art, records of the Propaganda Ministry in the Federal Archives “embody an ideology to which dance became subject,” as Ausdruckstanz, or the new German Dance, arose as a widely accepted art form due to Nazi leaders’ beliefs that dance would benefit the movement. Document 4 in Kant's work features a letter from Fritz Böhme to Goebbels, which articulates how the “German artistic dance … must not be allowed to be neglected as an art form” and must “function… as a constructive and formative force, as the guardian of racial values, and as a shield against the flood of confusing foreign postures alien to the German character and German stance”. Wigman and her colleagues’ modern dance styles were therefore deemed a means by which the German people could be shielded by outside influence and purified. A note from Ministerial Councilor von Keudell to the Reich Ministry for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda also recognized Wigman's school as one of the “four model schools of German art dance”. Ultimately, these records reveal how Wigman's work fit into the narrative of Nazism and how the fall of the Weimar Republic allowed for Wigman's success, yielding to the acceptance of “free” dance as Nazi propaganda.

Wigman's work also contributed to dance as a gateway for fascist community-building. Susan Manning writes in “Modern Dance in the Third Reich, Redux” that “modern dancers conflated and confused their ideal of the Tanzgemeinschaft (‘dance community’) with the fascist ideal of Volksgemeinschaft (‘ethnic community’)”. German dance environments therefore indirectly supported budding Nazi communities. Manning cites another work by Kant, “Death and the Maiden: Mary Wigman in the Weimar Republic,” in which Kant examines many writings by Wigman in the early years of the rise of Nazism in Germany. Here, Wigman seemed to express support for “the conservative and right-wing nationalists… who would bring down the Republic,” which Manning claims was instrumental in “bringing Volkish thought into the mainstream of Weimar politics”. Modern dance therefore became a hallmark of German unification, with Wigman's art heading the establishment of Volkish communities through dance. Whether Wigman's contributions to Nazism and its rise were intentional or unintentional is a matter of dispute, as Manning recognizes that “Mary Wigman could ave

''Alta Velocidad Española'' (''AVE'') is a service of high-speed rail in Spain operated by Renfe, the Spanish national railway company, at speeds of up to . As of December 2021, the Spanish high-speed rail network, on part of which the AVE s ...

�� opposed Nazi cultural policy, without recognizing that her own belief… reinforced the Nazi position”. Yet, despite Wigman's personal attitudes toward the Nazi Party, her work undoubtedly coexisted and even fit within Nazi ideals of Aryan freedom, community, and identity.

Post-war Germany

After 1945 Wigman began again with a

After 1945 Wigman began again with a Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

school and in 1947 staged a sensational performance of ''Orfeo ed Euridice

' (; French: '; English: ''Orpheus and Eurydice'') is an opera composed by Christoph Willibald Gluck, based on the myth of Orpheus and set to a libretto by Ranieri de' Calzabigi. It belongs to the genre of the '' azione teatrale'', meaning a ...

'' with her pupils at the Leipzig Opera. In 1949 Wigman settled in West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

, where she founded a new expressive dance school, the Mary Wigman Studio.

Schiller Prize and Order of Merit

In 1954 Wigman received the Schiller Prize of the City of Mannheim and in 1957 the Great Cross of theOrder of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

The Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (german: Verdienstorden der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, or , BVO) is the only federal decoration of Germany. It is awarded for special achievements in political, economic, cultural, intellect ...

. In 1967 she closed her West Berlin studio and devoted herself to lecturing at home and abroad. Mary Wigman died in 1973. Her funerary urn was buried on 14 November of that year in the Wiegmann family grave at the ''Ostfriedhof'' in Essen

Essen (; Latin: ''Assindia'') is the central and, after Dortmund, second-largest city of the Ruhr, the largest urban area in Germany. Its population of makes it the fourth-largest city of North Rhine-Westphalia after Cologne, Düsseldorf and Do ...

, Germany.

Productions

Wigman gave her first public performance in Munich in February 1914, performing two of her own dances, including one called ''Lento'' and the first version of ''Hexentanz'' (Witch Dance), which later became one of her most important works.

While recovering from her nervous breakdown, in 1918, Wigman wrote the choreography for her first group composition, ''Die sieben Tänze des Lebens'' (The Seven Dances of Life), which premiered several years later, in 1921. After that her career and influence began in earnest.

In 1925 the Italian financier

Wigman gave her first public performance in Munich in February 1914, performing two of her own dances, including one called ''Lento'' and the first version of ''Hexentanz'' (Witch Dance), which later became one of her most important works.

While recovering from her nervous breakdown, in 1918, Wigman wrote the choreography for her first group composition, ''Die sieben Tänze des Lebens'' (The Seven Dances of Life), which premiered several years later, in 1921. After that her career and influence began in earnest.

In 1925 the Italian financier Riccardo Gualino

Riccardo Gualino (25 March 1879 – 6 June 1964) was an Italian Business magnate and art collector. He was also a patron, and an important film producer. His first business empire was based on lumber from Eastern Europe and included forest concess ...

invited Wigman to Turin to perform in his private theater and in his newly opened ''Teatro di Torino''.

She had several years' success on the concert stage.

Wigman's dances were often accompanied by world music and non-Western instrumentation, such as fifes and primarily percussion, bells

Bells may refer to:

* Bell, a musical instrument

Places

* Bells, North Carolina

* Bells, Tennessee

* Bells, Texas

* Bells Beach, Victoria, an internationally famous surf beach in Australia

* Bells Corners, Ontario

Music

* Bells, directly st ...

, including the gongs

A gongFrom Indonesian and ms, gong; jv, ꦒꦺꦴꦁ ; zh, c=鑼, p=luó; ja, , dora; km, គង ; th, ฆ้อง ; vi, cồng chiêng; as, কাঁহ is a percussion instrument originating in East Asia and Southeast Asia. Gongs ...

and drum

The drum is a member of the percussion group of musical instruments. In the Hornbostel-Sachs classification system, it is a membranophone. Drums consist of at least one membrane, called a drumhead or drum skin, that is stretched over a ...

s from India, Thailand, Africa, and China, contrasted with silence. In later years, she used composers' talents to create music to accompany her choreography, and many choreographers began to use this tactic.

She would often employ masks in her pieces, influenced again by non-western/tribal dance. She did not use typical costumes associated with ballet. The subject matters included in her pieces were heavy, such as the death and desperation that was surrounding the war. However, she did not choreograph to represent the happenings of the war; she danced to outwardly convey the feelings that people were experiencing in this hard time.Mary Wigman. German Expressionist Dancer and Choreographer. https://www.contemporary-dance.org/mary-wigman.html

Recognition

Wigman's former student Katharine Sehnert still teaches dance technique and improvisation based on the Wigman style. In

Wigman's former student Katharine Sehnert still teaches dance technique and improvisation based on the Wigman style. In Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

, a street in the ''Seevorstadt'' and near Dresden Hauptbahnhof

Dresden Hauptbahnhof ("main station", abbreviated Dresden Hbf) is the largest passenger station in the Saxon capital of Dresden. In 1898, it replaced the ''Böhmischen Bahnhof'' ("Bohemian station") of the former Saxon-Bohemian State Railway ('' ...

, which had previously been named after Anton Saefkow

Anton Emil Hermann Saefkow (; 22 July 1903 – 18 September 1944) was a German Communist and a resistance fighter against the National Socialist régime. He was arrested in July 1944 and executed on 18 September by guillotine.

Early life

An ...

, was named after Mary Wigman. Streets were also named after her in the ''Vilich-Müldorf'' district of Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ru ...

, in the ''Bothfeld'' district of Hanover and in the '' Käfertal'' district of Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (german: Universitätsstadt Mannheim), is the second-largest city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg after the state capital of Stuttgart, and Germany's ...

. In Hanover, a commemorative plaque

A commemorative plaque, or simply plaque, or in other places referred to as a historical marker, historic marker, or historic plaque, is a plate of metal, ceramic, stone, wood, or other material, typically attached to a wall, stone, or other ...

was attached to Wigman's former home at ''Schmiedestrasse 18''. In Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

, a memorial plaque on the house at ''Mozartstrasse 17'' commemorates Wigman, who lived and taught there from 1942 until she moved to West Berlin in 1949.

Mary Wigman Societies and Mary Wigman Foundation

The first Mary Wigman Society was founded in Berlin in November 1925 as a society of friends of the Mary Wigman Dance Group. Founding members included the theatre director Max von Schillings, ReichskunstwartEdwin Redslob

Edwin Redslob (22 September 1884, Weimar – 24 January 1973, West Berlin) was a German art historian who served as Reichskunstwart under the Weimar Republic. Appointed in 1920, he was the only person to fulfil this role as the position was abolis ...

, the composer Eugen d'Albert

Eugen (originally Eugène) Francis Charles d'Albert (10 April 1864 – 3 March 1932) was a Scottish-born pianist and composer.

Educated in Britain, d'Albert showed early musical talent and, at the age of seventeen, he won a scholarship to stud ...

, the painters Emil Nolde and Conrad Felixmüller

Conrad Felixmüller (21 May 1897 – 24 March 1977) was a German Expressionism, expressionist painter and printmaker. Born in Dresden as Conrad Felix Müller, he chose Felixmüller as his ''Art-name, nom d'artiste''.

Early life and career

He a ...

, the archaeologist and senior government minister , the journalists and theatre critics Alfred Kerr

Alfred Kerr (''né'' Kempner; 25 December 1867 – 12 October 1948, surname: ) was an influential German theatre critic and essayist of Jewish descent, nicknamed the ''Kulturpapst'' ("Culture Pope").

Biography

Youth

Kerr was born in Breslau, ...

and , the art historian Fritz Wichert, Wilhelm Worringer

Wilhelm Robert Worringer (13 January 1881 in Aachen – 29 March 1965 in Munich) was a German art historian known for his theories about abstract art and its relation to avant-garde movements such as German Expressionism. Through his influence on ...

and and Privy Councilor Erich Lexer

Erich Lexer (22 May 1867 in Freiburg im Breisgau – 4 December 1937 in Berlin) was a German surgeon and university lecturer. With Eugen Holländer (1867 - 1932) and Jacques Joseph (1865 - 1934), he is regarded as the pioneer of plastic surgery. ...

, a surgeon. It only existed for a few years.

The ''Mary Wigman Gesellschaft e. V.'', which has been committed to the history and future of modern dance for decades, published the ''Tanzdrama'' (Dance Drama) magazine and organized a number of symposia, which was converted into a Mary Wigman Foundation (''Mary Wigman Stiftung'') in 2013. This is located at the German Dance Archive Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

(''Deutsches Tanzarchiv Köln''), which also owns the rights of use for Mary Wigman's works.

Mary Wigman Prize

Since 1993, the Foundation for the Promotion of theSemperoper

The Semperoper () is the opera house of the Sächsische Staatsoper Dresden (Saxon State Opera) and the concert hall of the Staatskapelle Dresden (Saxon State Orchestra). It is also home to the Semperoper Ballett. The building is located on the ...

has honoured outstanding artists or ensembles who belong or belonged to the Saxon State Opera (''Sächsischen Staatsoper'') with the Mary Wigman Prize. The award is presented annually at a gala – the foundation's prizewinners' concert. The first prize winner in 1993 was . The prize was not awarded from 2006 to 2012.

Works published

* ''Die sieben Tänze des Lebens. Tanzdichtung.'' Diederichs, Jena 1921. * ''Komposition.'' Seebote, Überlingen 1925. * ''Deutsche Tanzkunst.'' Reißner, Dresden 1935. * ''Die Sprache des Tanzes.'' Battenberg, Stuttgart 1963; New Edition: Battenberg, Munich 1986, . * ''The Language of Dance.'' Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, Connecticut 1966, .See also

*'' Ways to Strength and Beauty'', 1920s German cultural silent film featuring Mary Wigman and her dance group *Weimar culture

Weimar culture was the emergence of the arts and sciences that happened in Germany during the Weimar Republic, the latter during that part of the interwar period between Germany's defeat in World War I in 1918 and Hitler's rise to power in 193 ...

*Weimar Germany

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is als ...

*Expressionist dance

''Expressive dance'' from German ''Ausdruckstanz'', is a form of artistic dance in which the individual and artistic presentation (and sometimes also processing) of feelings is an essential part. It emerged as a counter-movement to classi ...

*Dore Hoyer

Dore Hoyer (12 December 1911 – 31 December 1967) was a German expressionist dancer and choreographer. She is credited as "one of the most important solo dancers of the Ausdruckstanz tradition." Inspired by Mary Wigman, she developed her own sol ...

*Isadora Duncan

Angela Isadora Duncan (May 26, 1877 or May 27, 1878 – September 14, 1927) was an American dancer and choreographer, who was a pioneer of modern contemporary dance, who performed to great acclaim throughout Europe and the US. Born and raised in ...

*Ruth St Denis

Ruth St. Denis (born Ruth Denis; January 20, 1879 – July 21, 1968) was an American pioneer of modern dance, introducing eastern ideas into the art. She was the co-founder of the American Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts and the tea ...

*Women in dance

The important place of women in dance can be traced back to the very origins of civilization. Cave paintings, Egyptian frescos, Indian statuettes, ancient Greek and Roman art and records of court traditions in China and Japan all testify to the i ...

References

Further reading

*Gilbert, Laure (2000). ''Danser avec le Troisième Reich'', Brussels: Editions Complex, *Karina, Lilian & Kant, Marion (2003). ''German Modern Dance and the Third Reich'', New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books, *Kolb, Alexandra (2009). ''Performing Femininity. Dance and Literature in German Modernism''. Oxford: Peter Lang. * Manning, Susan (1993). ''Ecstasy and the Demon: Feminism and Nationalism in the Dances of Mary Wigman'', University of California Press. . *Martin, John (1934). "Workers League In Group Dances", ''The New York Times'', 24 December. *Newhall, Mary; Santos, Anne (2009). ''Mary Wigman''. Routledge. *Partsch-Bergsohn, Isa; Bergsohn, Harold (2002). ''The Makers of Modern Dance in Germany: Rudolf Laban, Mary Wigman, Kurt Jooss'', Princeton Book Company Publishers. . *Song, Ji-yun (2006)"Moving bodies and political movement: Dance in German modernism"

dissertation,

Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is conside ...

.

*Song, Ji-yun (2007)"Mary Wigman and German Modern Dance: A Modernist Witch?"

''Forum for Modern Language Studies'', Oxford University Press (1 October 2007), 43(4): 427–437. Special Issue on Stagecraft and Witchcraft. *Toepfer, Karl Eric (1997). ''Empire of Ecstasy: Nudity and Movement in Germany Body Culture, 1910–1935 (Weimer and Now: German Cultural Criticism, No 13)'', University of California Press. . *Wigman, Mary (1975). '' The Mary Wigman Book: Her Writings'', Olympic Marketing Corp. .

External links

a student of Wigman's.

Photographs of Mary Wigman

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wigman, Mary 1886 births 1973 deaths Dance teachers Expressionist choreographers Expressionist dancers German women choreographers German female dancers Modern dancers Dancers from Berlin People from Hanover