Mary Harris Jones on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

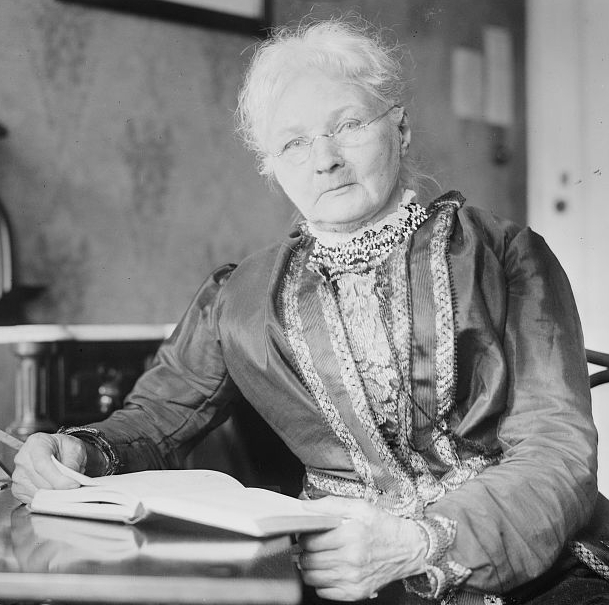

Mary G. Harris Jones (1837 (baptized) – November 30, 1930), known as Mother Jones from 1897 onwards, was an Irish-born American schoolteacher and dressmaker who became a prominent

Mary G. Harris was born on the north side of Cork, the daughter of

Mary G. Harris was born on the north side of Cork, the daughter of

Jones remained a union organizer for the UMW into the 1920s and continued to speak on union affairs almost until she died. She released her own account of her experiences in the labor movement as ''The Autobiography of Mother Jones'' (1925). Although Mother Jones organized for decades on behalf of the UMWA in West Virginia and even denounced the state as 'medieval', the chapter of the same name in her autobiography, she mostly praises Governor Morgan for defending the First Amendment freedom of the labor weekly ''The Federationist'' to publish. His refusal to consent to the mine owners' request that he ban the paper demonstrated to Mother Jones that he 'refused to comply with the requests of the dominant money interests. To a man of that type, I wish to pay my respects'. Apparently Jones did not know or overlooked that Morgan had received about $1 million in campaign donations from industrialists in the 1920 election.

During her later years, Jones lived with her friends Walter and Lillie May Burgess on their farm in what is now Adelphi, Maryland. She celebrated her self-proclaimed 100th birthday there on May 1, 1930, and was filmed making a statement for a

Jones remained a union organizer for the UMW into the 1920s and continued to speak on union affairs almost until she died. She released her own account of her experiences in the labor movement as ''The Autobiography of Mother Jones'' (1925). Although Mother Jones organized for decades on behalf of the UMWA in West Virginia and even denounced the state as 'medieval', the chapter of the same name in her autobiography, she mostly praises Governor Morgan for defending the First Amendment freedom of the labor weekly ''The Federationist'' to publish. His refusal to consent to the mine owners' request that he ban the paper demonstrated to Mother Jones that he 'refused to comply with the requests of the dominant money interests. To a man of that type, I wish to pay my respects'. Apparently Jones did not know or overlooked that Morgan had received about $1 million in campaign donations from industrialists in the 1920 election.

During her later years, Jones lived with her friends Walter and Lillie May Burgess on their farm in what is now Adelphi, Maryland. She celebrated her self-proclaimed 100th birthday there on May 1, 1930, and was filmed making a statement for a

She is buried in the Union Miners Cemetery in

She is buried in the Union Miners Cemetery in

* Jones' words are still invoked by union supporters more than a century later: "Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living." Already known as "the miners' angel" when she was denounced on the floor of the

* Jones' words are still invoked by union supporters more than a century later: "Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living." Already known as "the miners' angel" when she was denounced on the floor of the

online

* * Savage, Lon (1990)

Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. * State of West Virginia (2002). ''Marking Our Past: West Virginia's Historical Highway Markers''. Charleston: West Virginia Division of Culture and History. * Steel, Edward M. Steel, "Mother Jones in the Fairmont Field, 1902", ''Journal of American History'' 57, Number September 2, 1970) pp. 290–307.

DVD and virtual museum about Mother Jones

Mother Jones Speaks: Speeches and Writings of a Working-Class Fighter

''Autobiography of Mother Jones''

at

Free eBook of The Autobiography of Mother Jones

*

Mother Jones Monument at GuidepostUSA

* Michals, Debra

"Mary Harris Jones"

National Women's History Museum. 2015.

Jones

with Calvin Coolidge 1924 {{DEFAULTSORT:Jones, Mother 1837 births 1930 deaths 19th-century Irish women writers 19th-century Irish women 20th-century American educators 20th-century American memoirists 20th-century American women educators 20th-century American women writers American Christian socialists American community activists American women activists American women memoirists Burials in Illinois Catholic socialists Child labor in the United States Children's rights activists Civilians who were court-martialed Date of birth unknown Female Christian socialists Industrial Workers of the World leaders Irish Christian socialists Irish activists Irish emigrants to the United States (before 1923) Irish women activists Members of the Socialist Party of America People from County Cork People from Monroe, Michigan People from Mount Olive, Illinois Schoolteachers from Michigan Trade unionists from Pennsylvania Trade unionists from West Virginia United Mine Workers people

union organizer

A union organizer (or union organiser in Commonwealth spelling) is a specific type of trade union member (often elected) or an appointed union official. A majority of unions appoint rather than elect their organizers.

In some unions, the orga ...

, community organizer, and activist. She helped coordinate major strikes and co-founded the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

.

After Jones's husband and four children all died of yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

in 1867 and her dress shop was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire

The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned in the American city of Chicago during October 8–10, 1871. The fire killed approximately 300 people, destroyed roughly of the city including over 17,000 structures, and left more than 10 ...

of 1871, she became an organizer for the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

and the United Mine Workers union. In 1902, she was called "the most dangerous woman in America" for her success in organizing mine workers and their families against the mine owners. In 1903, to protest the lax enforcement of the child labor laws in the Pennsylvania mines and silk mills, she organized a children's march from Philadelphia to the home of President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

in New York.

Early life

Mary G. Harris was born on the north side of Cork, the daughter of

Mary G. Harris was born on the north side of Cork, the daughter of Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

tenant farmers Richard Harris and Ellen (née Cotter) Harris.''Day by Day in Cork'', Sean Beecher, Collins Press, Cork, 1992 Her exact date of birth is uncertain; she was baptized on August 1, 1837. Harris and her family were victims of the Great Famine, as were many other Irish families. The famine drove more than a million families, including the Harrises, to immigrate to North America when Harris was 10.

Formative years

Mary was a teenager when her family immigrated to Canada.Arnesen, Eric. "A Tarnished Icon", ''Reviews in American History'' 30, no. 1 (2002): 89 In Canada (and later in the United States), the Harris family were victims of discrimination due to their immigrant status as well as their Catholic faith and Irish heritage. Mary received an education inToronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

at the Toronto Normal School

The Toronto Normal School was a teachers college in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Opened in 1847, the Normal School was located at Church and Gould streets in central Toronto (after 1852), and was a predecessor to the current Ontario Institute for ...

, which was tuition-free and even paid a stipend to each student of one dollar per week for every semester completed. Mary did not graduate from the Toronto Normal School, but she was able to undergo enough training to occupy a teaching position at a convent in Monroe, Michigan

Monroe is the largest city and county seat of Monroe County in the U.S. state of Michigan. Monroe had a population of 20,462 in the 2020 census. The city is bordered on the south by Monroe Charter Township, but the two are administered auton ...

, on August 31, 1859 at the age of 23. She was paid eight dollars per month, but the school was described as a "depressing place". After tiring of her assumed profession, she moved first to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

and then to Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

, where in 1861 she married George E. Jones, a member and organizer of the National Union of Iron Moulders,''Religion and Radical Politics: An Alternative Christian Tradition in the United States'', Robert H. Craig, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1992 which later became the International Molders and Foundry Workers Union of North America

International Molders and Foundry Workers Union of North America was an affiliated trade union of the AFL–CIO. The union traced its roots back to the formation of the Iron Molders' Union of North America, established in 1859 to represent craftsm ...

, which represented workers who specialized in building and repairing steam engines, mills, and other manufactured goods.Russell E. Smith, "March of the Mill Children", ''The Social Service Review'' 41, no. 3 (1967): 299 Considering that Mary's husband was providing enough income to support the household, she altered her labor to housekeeping.

The loss of her husband and their four children, three girls and a boy (all under the age of five), in 1867, during a yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

epidemic in Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

marked a turning point in her life. After that tragedy, she returned to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

to begin another dressmaking business. She did work for those of the upper class of Chicago in the 1870s and 1880s. Then, four years later, she lost her home, shop, and possessions in the Great Chicago Fire

The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned in the American city of Chicago during October 8–10, 1871. The fire killed approximately 300 people, destroyed roughly of the city including over 17,000 structures, and left more than 10 ...

of 1871. This huge fire destroyed many homes and shops. Jones, like many others, helped rebuild the city. According to her autobiography, this led to her joining the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

. She started organizing strikes. At first the strikes and protests failed, sometimes ending with police shooting at and killing protesters. The Knights mainly attracted men, but by the middle of the decade member numbers leaped to more than a million, becoming the largest labor organization in the country. The Haymarket Affair

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square i ...

of 1886 and the fear of anarchism and social change incited by union organizations resulted in the demise of the Knights of Labor when an unknown person threw a bomb into an altercation between the Chicago police and workers on strike. Once the Knights ceased to exist, Mary Jones became involved mainly with the United Mine Workers. She frequently led UMW strikers in picketing and encouraged striking workers to stay on strike when management brought in strike-breakers and militias. She believed that "working men deserved a wage that would allow women to stay home to care for their kids." Around this time, strikes were getting better organized and started to produce greater results, such as better pay for the workers.

Another source of her transformation into an organizer, according to biographer Elliott Gorn, was her early Roman Catholicism and her relationship to her brother, Father William Richard Harris. He was a Roman Catholic teacher, writer, pastor, and dean of the Niagara Peninsula (in St. Catharines, Ontario) in the Diocese of Toronto and was "among the best-known clerics in Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central C ...

", but from whom she was reportedly estranged. Her political views may have been influenced by the 1877 railroad strike, Chicago's labor movement, and the Haymarket Affair

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square i ...

and depression of 1886.

Active as an organizer and educator in strikes throughout the country at the time, she was involved particularly with the UMW and the Socialist Party of America. As a union organizer

A union organizer (or union organiser in Commonwealth spelling) is a specific type of trade union member (often elected) or an appointed union official. A majority of unions appoint rather than elect their organizers.

In some unions, the orga ...

, she gained prominence for organizing the wives and children of striking workers in demonstrations on their behalf. She was termed "the most dangerous woman in America" by a West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the B ...

n district attorney, Reese Blizzard, in 1902 at her trial for ignoring an injunction banning meetings by striking miners. "There sits the most dangerous woman in America", announced Blizzard. "She comes into a state where peace and prosperity reign... crooks her finger ndtwenty thousand contented men lay down their tools and walk out."

Jones was ideologically separated from many female activists of the pre- Nineteenth Amendment days due to her lack of commitment to female suffrage. She was quoted as saying that "you don't need the vote to raise hell!" She opposed many of the activists because she believed it was more important to liberate the working class itself. When some suffragettes accused her of being anti-women's rights, she clearly articulated herself, "I'm not an anti to anything which brings freedom to my class." She became known as a charismatic and effective speaker throughout her career.Mari Boor Tonn, "Militant Motherhood: Labor's Mary Harris 'Mother' Jones", ''Quarterly Journal of Speech'' 81, no. 1 (1996): 2 She was an exceptionally talented orator. Occasionally she would include props, visual aids, and dramatic stunts for effect. Her talks usually involved the relating of some personal tale in which she invariably "showed up" one form of authority or another. It is said Mother Jones spoke in a pleasant-sounding brogue which projected well. When she grew excited, her voice dropped in pitch.

By age 60, she had assumed the persona of "Mother Jones" by claiming to be older than she was, wearing outdated black dresses and referring to the male workers that she helped as "her boys". The first reference to her in print as ''Mother Jones'' was in 1897.

"March of the Mill Children"

In 1901, workers in Pennsylvania's silk mills went on strike. Many of them were young women demanding to be paid adult wages.Bonnie Stepenoff, "Keeping it in the Family: Mother Jones and the Pennsylvania Silk Strike of 1900–1901", ''Labor History'' 38, no. 4 (1997): 446 The 1900 census had revealed that one sixth of American children under the age of sixteen were employed. John Mitchell, the president of the UMWA, brought Mother Jones to north-eastPennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

in the months of February and September to encourage unity among striking workers. To do so, she encouraged the wives of the workers to organize into a group that would wield brooms, beat on tin pans, and shout "join the union!" She felt that wives had an important role to play as the nurturers and motivators of the striking men, but not as fellow workers. She claimed that the young girls working in the mills were being robbed and demoralized. The rich were denying these children the right to go to school in order to be able to pay for their own children's college tuitions.

To enforce worker solidarity, she traveled to the silk mills in New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

and returned to Pennsylvania to report that the conditions she observed were much better. She stated that "the child labor

Child labour refers to the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, and is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such e ...

law is better enforced for one thing and there are more men at work than seen in the mills here." In response to the strike, mill owners also divulged their side of the story. They claimed that if the workers still insisted on a wage scale, they would not be able to do business while paying adult wages and would be forced to close.Bonnie Stepenoff, "Keeping it in the Family: Mother Jones and the Pennsylvania Silk Strike of 1900–1901", ''Labor History'' 38, no. 4 (1997): 448 Even Jones herself encouraged the workers to accept a settlement. Although she agreed to a settlement that sent the young girls back to the mills, she continued to fight child labor for the rest of her life.

In 1903, Jones organized children who were working in mills and mines to participate in her famous "March of the Mill Children" from Kensington, Philadelphia, to the summer house (and Summer White House

Listed below are the private residences of the various presidents of the United States. For a list of official residences, see President of the United States § Residence.

Private homes of the presidents

This is a list of homes where ...

) of President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

on Long Island (in Oyster Bay, New York). They had banners demanding "We want to go to school and not the mines!" and held rallies each night in a new town on the way with music, skits, and speeches drawing thousands of citizens.

As Mother Jones noted, many of the children at union headquarters were missing fingers and had other disabilities, and she attempted to get newspaper publicity for the bad conditions experienced by children working in Pennsylvania. However, the mill owners held stock in most newspapers. When the newspapermen informed her that they could not publish the facts about child labor because of this, she remarked "Well, I've got stock in these little children and I'll arrange a little publicity." Permission to see President Roosevelt was denied by his secretary, and it was suggested that Jones address a letter to the president requesting a visit with him. Even though Mother Jones wrote a letter asking for a meeting, she never received an answer. Though the president refused to meet with the marchers, the incident brought the issue of child labor to the forefront of the public agenda. The 2003 non-fiction book '' Kids on Strike!'' described Jones's Children's Crusade in detail.

Activism and criminal charges

During the Paint Creek–Cabin Creek strike of 1912 inWest Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the B ...

, Mary Jones arrived in June 1912, speaking and organizing despite a shooting war between United Mine Workers members and the private army of the mine owners. Martial law in the area was declared and rescinded twice before Jones was arrested on February 13, 1913, and brought before a military court. Accused of conspiring to commit murder among other charges, she refused to recognize the legitimacy of her court-martial. She was sentenced to twenty years in the state penitentiary. During house arrest at Mrs. Carney's Boarding House, she acquired a dangerous case of pneumonia.

After 85 days of confinement, her release coincided with Indiana Senator John W. Kern's initiation of a Senate investigation into the conditions in the local coal mines. Mary Lee Settle describes Jones at this time in her 1978 novel ''The Scapegoat''. Several months later, she helped organize coal miners in Colorado in the 1913–14 United Mine Workers of America strike against the Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel and Iron company, in what is known as the Colorado Coalfield War

The Colorado Coalfield War was a major labor uprising in the Southern and Central Colorado Front Range between September 1913 and December 1914. Striking began in late summer 1913, organized by the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) agai ...

. Once again she was arrested, serving time in prison and inside the San Rafael Hospital, and was escorted from the state in the months prior to the Ludlow Massacre. After the massacre, she was invited to meet face-to-face with the owner of the Ludlow mine, John D. Rockefeller Jr. The meeting was partially responsible for Rockefeller's 1915 visit to the Colorado mines and introduction of long-sought reforms.

Mother Jones attempted to stop miners from marching into Logan County, West Virginia, in late August 1921. Mother Jones also visited the governor and departed assured he would intervene. Jones opposed the armed march, appeared on the line of march and told them to go home. In her hand, she claimed to have a telegram from President Warren Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

offering to work to end the private police in West Virginia if they returned home. When UMW president Frank Keeney demanded to see the telegram, Mother Jones refused and he denounced her as a 'fake'. Because she refused to show anyone the telegram, and the President's secretary denied ever having sent one, she was suspected of having fabricated the story. After she fled the camp, she reportedly suffered a nervous breakdown.

Mother Jones was joined by Keeney and other UMWA officials who were also pressuring the miners to go home.

Later years

Jones remained a union organizer for the UMW into the 1920s and continued to speak on union affairs almost until she died. She released her own account of her experiences in the labor movement as ''The Autobiography of Mother Jones'' (1925). Although Mother Jones organized for decades on behalf of the UMWA in West Virginia and even denounced the state as 'medieval', the chapter of the same name in her autobiography, she mostly praises Governor Morgan for defending the First Amendment freedom of the labor weekly ''The Federationist'' to publish. His refusal to consent to the mine owners' request that he ban the paper demonstrated to Mother Jones that he 'refused to comply with the requests of the dominant money interests. To a man of that type, I wish to pay my respects'. Apparently Jones did not know or overlooked that Morgan had received about $1 million in campaign donations from industrialists in the 1920 election.

During her later years, Jones lived with her friends Walter and Lillie May Burgess on their farm in what is now Adelphi, Maryland. She celebrated her self-proclaimed 100th birthday there on May 1, 1930, and was filmed making a statement for a

Jones remained a union organizer for the UMW into the 1920s and continued to speak on union affairs almost until she died. She released her own account of her experiences in the labor movement as ''The Autobiography of Mother Jones'' (1925). Although Mother Jones organized for decades on behalf of the UMWA in West Virginia and even denounced the state as 'medieval', the chapter of the same name in her autobiography, she mostly praises Governor Morgan for defending the First Amendment freedom of the labor weekly ''The Federationist'' to publish. His refusal to consent to the mine owners' request that he ban the paper demonstrated to Mother Jones that he 'refused to comply with the requests of the dominant money interests. To a man of that type, I wish to pay my respects'. Apparently Jones did not know or overlooked that Morgan had received about $1 million in campaign donations from industrialists in the 1920 election.

During her later years, Jones lived with her friends Walter and Lillie May Burgess on their farm in what is now Adelphi, Maryland. She celebrated her self-proclaimed 100th birthday there on May 1, 1930, and was filmed making a statement for a newsreel

A newsreel is a form of short documentary film, containing news stories and items of topical interest, that was prevalent between the 1910s and the mid 1970s. Typically presented in a cinema, newsreels were a source of current affairs, inform ...

.

Death

Mary Harris Jones died on November 30, 1930, at the Burgess farm, then in Silver Spring, Maryland, though now part of Adelphi. There was a funeral Mass at St. Gabriel's in Washington, D.C. She is buried in the Union Miners Cemetery in

She is buried in the Union Miners Cemetery in Mount Olive, Illinois

Mount Olive is a city in Macoupin County, Illinois, United States. The population was 2,015 at the 2020 census. The city is part of the Metro East region within the St. Louis metropolitan area.

Geography

Mount Olive is located in southeastern Ma ...

, alongside miners who died in the 1898 Battle of Virden

The Battle of Virden, also known as the Virden Mine Riot and Virden Massacre, was a labor union conflict and a racial conflict in central Illinois that occurred on October 12, 1898. After a United Mine Workers of America local struck a mine in Vi ...

. She called these miners, killed in strike-related violence, "her boys." In 1932, about 15,000 Illinois mine workers gathered in Mount Olive to protest against the United Mine Workers, which soon became the Progressive Mine Workers of America. Convinced that they had acted in the spirit of Mother Jones, the miners decided to place a proper headstone on her grave. By 1936, the miners had saved up more than $16,000 and were able to purchase "eighty tons of Minnesota pink granite, with bronze statues of two miners flanking a twenty-foot shaft featuring a bas-relief of Mother Jones at its center." On October 11, 1936, also known as Miners' Day, an estimated 50,000 people arrived at Mother Jones's grave to see the new gravestone and memorial. Since then, October 11 is not only known as Miners' Day but is also referred to and celebrated in Mount Olive as "Mother Jones's Day."

The farm where she died began to advertise itself as the "Mother Jones Rest Home" in 1932, before being sold to a Baptist church in 1956. The site is now marked with a Maryland Historical Trust marker, and a nearby elementary school is named in her honor.

Legacy

According to labor historian Melvyn Dubofsky: ::Indeed her renown as a radical rests on a shaky historical foundation. A woman who publicly accused UMW officials of selling out their followers to the capitalist class, she negotiated amicably with John D Rockefeller. Jr., in the aftermath of the 1914 Ludlow massacre... Famous for enlisting workers' wives in the labor struggle, she opposed women's suffrage and insisted that woman's place was in the home... She was simply and essentially an individualist, one who chose to devote the last 30 years of a long life to the cause of the working-class. Her influence on the American labor movement was, however, largely symbolic: the image of a grandmotherly, staidly dressed, slightly built woman unfazed by hostile employers, their hired gunmen, or anti-labor public officials intensified the militancy workers who saw her or who heard of her deeds. * Jones' words are still invoked by union supporters more than a century later: "Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living." Already known as "the miners' angel" when she was denounced on the floor of the

* Jones' words are still invoked by union supporters more than a century later: "Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living." Already known as "the miners' angel" when she was denounced on the floor of the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

as the "grandmother of all agitators", she replied, "I hope to live long enough to be the great-grandmother of all agitators."

* During the bitter 1989–90 Pittston Coal strike

The Pittston Coal strike was a United States strike action led by the United Mine Workers Union (UMWA) against the Pittston Coal Company, nationally headquartered in Pittston, Pennsylvania. The strike, which lasted from April 5, 1989 to Febr ...

in Virginia, West Virginia and Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

, the wives and daughters of striking coal miners, inspired by the still-surviving tales of Jones's legendary work among an earlier generation of the region's coal miners, dubbed themselves the "Daughters of Mother Jones". They played a crucial role on the picket lines and in presenting the miners' case to the press and public.

* ''Mother Jones

Mary G. Harris Jones (1837 (baptized) – November 30, 1930), known as Mother Jones from 1897 onwards, was an Irish-born American schoolteacher and dressmaker who became a prominent union organizer, community organizer, and activist. She h ...

'' magazine was established in the 1970s and quickly became "the largest selling radical magazine of the decade."

* Mary Harris "Mother" Jones Elementary School in Adelphi, Maryland.

* Students at Wheeling Jesuit University

Wheeling University (WU, formerly Wheeling Jesuit University) is a private Roman Catholic university in Wheeling, West Virginia. It was founded as Wheeling College in 1954 by the Society of Jesus (also known as the Jesuits) and was a Jesuit inst ...

, Wheeling, West Virginia

Wheeling is a city in the U.S. state of West Virginia. Located almost entirely in Ohio County, of which it is the county seat, it lies along the Ohio River in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains and also contains a tiny portion extending ...

, can apply to reside in Mother Jones House, an off-campus service house. Residents perform at least ten hours of community service

Community service is unpaid work performed by a person or group of people for the benefit and betterment of their community without any form of compensation. Community service can be distinct from volunteering, since it is not always performe ...

each week and participate in community dinners and events.

* In 1984, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.

* To coincide with International Women's Day on March 8, 2010 a proposal from Councillor Ted Tynan for a plaque to be erected in Mary Harris Jones's native Cork City

Cork ( , from , meaning 'marsh') is the second largest city in Ireland and third largest city by population on the island of Ireland. It is located in the south-west of Ireland, in the province of Munster. Following an extension to the city's ...

was passed by the Cork City Council

Cork City Council ( ga, Comhairle Cathrach Chorcaí) is the authority responsible for local government in the city of Cork in Ireland. As a city council, it is governed by the Local Government Act 2001. Prior to the enactment of the 2001 Act, t ...

. Members of the Cork Mother Jones Commemorative Committee unveiled the plaque on August 1, 2012 to mark the 175th anniversary of her birth. The Cork Mother Jones Festival was held in the Shandon area of the city, close to her birthplace, with numerous guest speakers. The festival now takes place annually around the anniversary and has led to growing awareness of Mother Jones's legacy and links between admirers in Ireland and the US. A new documentary, Mother Jones and her children, has been produced by Cork-based Frameworks Films and premiered at the Cork festival in 2014.

* The imprisonment of "Mother" Jones is commemorated by the State of West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the B ...

through a Historic Highway marker. The marker was made by the West Virginia Division of Culture and History. The marker reads, "PRATT. First settled in the early 1780s and incorporated in 1905. Important site in 1912–13 Paint–Cabin Creek Strike. Labor organizer 'Mother Jones' spent her 84th birthday imprisoned here. Pratt Historic District, listed on the National Register in 1984, recognizes the town's important residential architecture from early plantation to Victorian Styles." The marker is located in the town of Pratt, right off of West Virginia 61.

*In 2019, Mother Jones was inducted into the National Mining Hall of Fame.

Music and the arts

* In ''The American Songbag'', Carl Sandburg suggests that the "she" in "She'll Be Coming 'Round the Mountain

"She'll Be Coming 'Round the Mountain" (sometimes referred to as "Coming 'Round the Mountain") is a traditional folk song often categorized as children's music. The song is derived from the Christian spiritual known as "When the Chariot Comes". ...

" references Mother Jones and her travels to Appalachian mountain coal-mining camps promoting the unionization of the miners.

* On February 25, 1925, Gene Autry recorded the W.C. Callaway composition "The Death Of Mother Jones".

* "The most dangerous woman," a spoken-word performance by indie folk singer/spoken word performer Utah Phillips

Bruce Duncan "Utah" Phillips (May 15, 1935 – May 23, 2008)

, KVMR, Nevada City, California, May 24, 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2008 ...

with music and backing vocals added to it by indie folk artist Ani Difranco, can be found on their collaborative album ''Fellow Workers''. The title refers to the moniker that a West Virginia District Attorney Reese Blizzard gave to Mother Jones, referring to her as "the most dangerous woman in America." Phillips performed the song "The Charge on Mother Jones." This folk song was written by William M. Rogers.

* In '', KVMR, Nevada City, California, May 24, 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2008 ...

Uncle

An uncle is usually defined as a male relative who is a sibling of a parent or married to a sibling of a parent. Uncles who are related by birth are second-degree relatives. The female counterpart of an uncle is an aunt, and the reciprocal rela ...

'' by J.P. Martin, a train line is called Mother Jones's Siding and is rumored to be run by Mother Jones.

* Through the fall of 1979 to summer 1980, the Overland Stage Company toured ''The Trial of Mother Jones'' throughout Wyoming and Colorado. The script by Roger Holzberg (with additional dialogue by Deb Scott) played in schools, community settings, and for union conferences. The middle school show was ''The Walsh Commission'' by John Murphy.

* "The Spirit of Mother Jones" is a track on the 2010 ''Abocurragh'' album by Irish singer-songwriter Andy Irvine.

* The title track of folk-roots duo Wishing Chair and Kara Barnard's 2002 album ''Dishpan Brigade'' is about Jones and her role in the 1899–1900 miners' strike in Arnot, Pennsylvania.

* Jones is the "woman" in Tom Russell's song "The Most Dangerous Woman in America," a commentary on the troubles of striking miners that appeared on his 2009 album ''Blood and Candle Smoke'' on the Shout! Factory label.

* The play ''The Kentucky Cycle: Fire in the Hole'' portrays Jones as an inspirational figure one of the other characters knew and was inspired by to go and create unions in other coal towns.

* The play ''Can't Scare Me...the Story of Mother Jones'' is written and performed by actress, playwright, and professor Kaiulani Lee. It premiered at the Atlas Theater in Washington, D.C. in 2011, and Lee took the show on tour with the United Mine Workers across Colorado as well as tours in Ireland, Bangladesh, and Cambodia.

* ''Mother Jones in Heaven'' is a one-woman musical written by the singer-songwriter and activist Si Kahn. It had its world premiere in Juneau, Alaska, in March 2014.

* ''Mother Jones and the Children's Crusade'', a musical based on her work in Pennsylvania, debuted in July 2014 as part of the New York Musical Theatre Festival

The New York Musical Festival (NYMF) was an annual three-week summer festival that operated from 2004 to 2019. It presented more than 30 new musicals a year in New York City's midtown theater district. More than half were chosen by leading theate ...

in NYC. The play starred Robin de Jesus and Lynne Wintersteller.

* "Never Call Me a Lady" (Brooklyn Publishers) is a 10-minute monologue by playwright Rusty Harding, in which Mother Jones recounts her life to a fellow traveler in a Chicago train station.

* ''Victory at Arnot'' is a work for chamber group and narrator by composer Eleanor Aversa. It recounts how Mother Jones assisted with the coal miners' strike in 1899–1900 in Arnot, Pennsylvania, and celebrates the power of non-violent resistance. The piece premiered in Philadelphia in 2016 and was followed by performances in Boston.

References

Primary sources

* * * Corbin, David (2011). ''Gun Thugs, Rednecks, and Radicals: A Documentary History of the West Virginia Mine Wars.'' Oakland: PM Press.Further reading

* Dilliard, Irving and Mary Sue Dilliard Schusky, "Mary Harris Jones," in ''Notable American Women 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume II'' ed. by Edward T. Wilson, (1971) pp. 286–88. * Fetherling, Dale. ''Mother Jones, the Miners' Angel: A Portrait'' (1979online

* * Savage, Lon (1990)

Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. * State of West Virginia (2002). ''Marking Our Past: West Virginia's Historical Highway Markers''. Charleston: West Virginia Division of Culture and History. * Steel, Edward M. Steel, "Mother Jones in the Fairmont Field, 1902", ''Journal of American History'' 57, Number September 2, 1970) pp. 290–307.

External links

DVD and virtual museum about Mother Jones

Mother Jones Speaks: Speeches and Writings of a Working-Class Fighter

''Autobiography of Mother Jones''

at

Project Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg (PG) is a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, as well as to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks."

It was founded in 1971 by American writer Michael S. Hart and is the oldest digital libr ...

Free eBook of The Autobiography of Mother Jones

*

Mother Jones Monument at GuidepostUSA

* Michals, Debra

"Mary Harris Jones"

National Women's History Museum. 2015.

Jones

with Calvin Coolidge 1924 {{DEFAULTSORT:Jones, Mother 1837 births 1930 deaths 19th-century Irish women writers 19th-century Irish women 20th-century American educators 20th-century American memoirists 20th-century American women educators 20th-century American women writers American Christian socialists American community activists American women activists American women memoirists Burials in Illinois Catholic socialists Child labor in the United States Children's rights activists Civilians who were court-martialed Date of birth unknown Female Christian socialists Industrial Workers of the World leaders Irish Christian socialists Irish activists Irish emigrants to the United States (before 1923) Irish women activists Members of the Socialist Party of America People from County Cork People from Monroe, Michigan People from Mount Olive, Illinois Schoolteachers from Michigan Trade unionists from Pennsylvania Trade unionists from West Virginia United Mine Workers people