Martha Layne Collins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Martha Layne Collins (

By 1971, Collins was the president of the Jayceettes; through her work there, she came to the attention of Democratic

By 1971, Collins was the president of the Jayceettes; through her work there, she came to the attention of Democratic

In the general election, Collins faced Republican state senator Jim Bunning, who was later elected to the

In the general election, Collins faced Republican state senator Jim Bunning, who was later elected to the

By virtue of her election as Kentucky's governor, Collins became the highest-ranking Democratic woman in the nation.York, "Victory Gives Collins Spot in the National Political Arena" The only two women in the U.S. Senate at the time were Republicans, and Collins was the only woman governor of any state. Shortly after her election, she appeared on ''

By virtue of her election as Kentucky's governor, Collins became the highest-ranking Democratic woman in the nation.York, "Victory Gives Collins Spot in the National Political Arena" The only two women in the U.S. Senate at the time were Republicans, and Collins was the only woman governor of any state. Shortly after her election, she appeared on ''

née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

Hall; born December 7, 1936) is an American former businesswoman and politician from the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

of Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

; she was elected as the state's 56th governor from 1983 to 1987, the first woman to hold the office and the only one to date. Prior to that, she served as the 48th Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky

The lieutenant governor of Kentucky was created under the state's second constitution, which was ratified in 1799. The inaugural officeholder was Alexander Scott Bullitt, who took office in 1800 following his election to serve under James Garra ...

, under John Y. Brown, Jr. Her election made her the highest-ranking Democratic woman in the U.S. She was considered as a possible running mate for Democratic presidential nominee Walter Mondale

Walter Frederick "Fritz" Mondale (January 5, 1928 – April 19, 2021) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 42nd vice president of the United States from 1977 to 1981 under President Jimmy Carter. A U.S. senator from Minnesota ...

in the 1984 presidential election, but Mondale chose Congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro

Geraldine Anne Ferraro (August 26, 1935 March 26, 2011) was an American politician, diplomat, and attorney. She served in the United States House of Representatives from 1979 to 1985, and was the Democratic Party's vice presidential nominee ...

instead.

After graduating from the University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky (UK, UKY, or U of K) is a public land-grant research university in Lexington, Kentucky. Founded in 1865 by John Bryan Bowman as the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Kentucky, the university is one of the state ...

, Collins worked as a school teacher while her husband finished a degree in dentistry. She became interested in politics, and worked on both Wendell Ford

Wendell Hampton Ford (September 8, 1924 – January 22, 2015) was an American politician from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. He served for twenty-four years in the U.S. Senate and was the 53rd Governor of Kentucky. He was the first person to be ...

's gubernatorial campaign in 1971 and Walter "Dee" Huddleston's U.S. Senate campaign in 1972. In 1975, she was chosen secretary of the state's Democratic Party and was elected clerk of the Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky.

Th ...

. During her tenure as clerk, a constitutional amendment restructured the state's judicial system, and the Court of Appeals became the Kentucky Supreme Court

The Kentucky Supreme Court was created by a 1975 constitutional amendment and is the state supreme court of the U.S. state of Kentucky. Prior to that the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky. The Kentucky Court of ...

. Collins continued as clerk of the renamed court and worked to educate citizens about the court's new role.

Collins was elected lieutenant governor in 1979, under Governor John Y. Brown, Jr. Brown was frequently out of the state, leaving Collins as acting governor for more than 500 days of her four-year term. In 1983, she defeated Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Jim Bunning to become Kentucky's first woman governor. Her administration had two primary focuses: education and economic development. After failing to secure increased funding for education in the 1984 legislative session, she conducted a statewide public awareness campaign in advance of a special legislative session the following year; the modified program was passed in that session. She successfully used economic incentives to bring a Toyota

is a Japanese multinational automotive manufacturer headquartered in Toyota City, Aichi, Japan. It was founded by Kiichiro Toyoda and incorporated on . Toyota is one of the largest automobile manufacturers in the world, producing about 10 ...

manufacturing plant to Georgetown, Kentucky

Georgetown is a home rule-class city in Scott County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 37,086 at the 2020 census. It is the 6th-largest city by population in the U.S. state of Kentucky. It is the seat of its county. It was original ...

in 1986. Legal challenges to the incentives – which would have cost the state the plant and its related economic benefits – were eventually dismissed by the Kentucky Supreme Court. The state experienced record economic growth under Collins's leadership.

At the time, Kentucky governors were not eligible for reelection. Collins taught at several universities after her four-year term as governor. From 1990 to 1996, she was the president of Saint Catharine College near Springfield, Kentucky

Springfield is a List of cities in Kentucky, home rule-class city in and county seat of Washington County, Kentucky, Washington County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 2,846 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census.

History

Spring ...

. The 1993 conviction of Collins's husband, Dr. Bill Collins, in an influence-peddling scandal, damaged her hopes for a return to political life. Prior to her husband's conviction it had been rumored that she would be a candidate for the U.S. Senate, or would take a position in the administration of President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again ...

. From 1998 to 2012, Collins served as an executive scholar-in-residence at Georgetown College

Georgetown College is a private Christian college in Georgetown, Kentucky. Chartered in 1829, Georgetown was the first Baptist college west of the Appalachian Mountains.

The college offers 38 undergraduate degrees and a Master of Arts in educat ...

.

Early life

Martha Layne Hall was born December 7, 1936, inBagdad, Kentucky

Bagdad is an unincorporated community in northeastern Shelby County, Kentucky, United States. It was founded at what is currently the intersection of Kentucky Routes 12 and 395

__NOTOC__

Year 395 ( CCCXCV) was a common year starting ...

,"Martha Layne Collins". Hall of Distinguished Alumni the only child of Everett and Mary (Taylor) Hall.Ryan, p. 229 When Martha Layne was in the sixth grade

Sixth grade (or grade six in some regions) is the sixth year of schooling. Students are typically 11–12 years old, depending on when their birthday occurs. Different terms and numbers are used in other parts of the world. It is commonly the firs ...

, her family moved to Shelbyville, Kentucky

Shelbyville is a home rule-class city in and the county seat of Shelby County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 14,045 at the 2010 census.

History

Early history

The town of Shelbyville was established in October 1792 at the first m ...

, and opened the Hall-Taylor Funeral Home. Martha Layne was involved in numerous extracurricular activities both in school and at the local Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

church. Her parents were active in local politics, working for the campaigns of several Democratic candidates, and Hall frequently joined them, stuffing envelopes and delivering pamphlets door-to-door.Bean, "Collins Prides Herself on Hard Work"

Martha Layne attended Shelbyville High School where she was a good student and a cheerleader.Jones, "Collins's Rise in Politics Credited to Hard Work" She frequently competed in beauty pageants and won the title of Shelby County Tobacco Festival Queen in 1954. After high school, Hall enrolled at Lindenwood College

Lindenwood University is a private university in St. Charles, Missouri. Founded in 1827 by George Champlin Sibley and Mary Easton Sibley as The Lindenwood School for Girls, it is the second-oldest higher-education institution west of the M ...

, then an all-woman college in Saint Charles, Missouri (It is now a co-ed university). After one year at Lindenwood, she transferred to the University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky (UK, UKY, or U of K) is a public land-grant research university in Lexington, Kentucky. Founded in 1865 by John Bryan Bowman as the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Kentucky, the university is one of the state ...

in Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a city in Kentucky, United States that is the county seat of Fayette County. By population, it is the second-largest city in Kentucky and 57th-largest city in the United States. By land area, it is the country's 28th-largest ...

. She was active in many clubs, including the Chi Omega

Chi Omega (, also known as ChiO) is a women's fraternity and a member of the National Panhellenic Conference, the umbrella organization of 26 women's fraternities.

Chi Omega has 181 active collegiate chapters and approximately 240 alumnae chap ...

social sorority, the Baptist Student Union

The Baptist Collegiate Network (BCN) is a college-level organization that can be found on many college campuses in the United States and Canada.

Organizations

These ministries are groups of students, faculty members and staff who are seeking to ...

, and the home economics club, and was also the president of her dormitory and vice president of the house presidents council.

In 1957, Hall met Billy Louis Collins while attending a Baptist camp in Shelby County. He was a student at Georgetown College

Georgetown College is a private Christian college in Georgetown, Kentucky. Chartered in 1829, Georgetown was the first Baptist college west of the Appalachian Mountains.

The college offers 38 undergraduate degrees and a Master of Arts in educat ...

in Georgetown, Kentucky

Georgetown is a home rule-class city in Scott County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 37,086 at the 2020 census. It is the 6th-largest city by population in the U.S. state of Kentucky. It is the seat of its county. It was original ...

, about 13 miles from Lexington; he and Hall dated while finishing their degrees. Hall earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Home Economics

Home economics, also called domestic science or family and consumer sciences, is a subject concerning human development, personal and family finances, consumer issues, housing and interior design, nutrition and food preparation, as well as texti ...

in 1959.Harrison, p. 214 Having won the title of Kentucky Derby Festival

The Kentucky Derby Festival is an annual festival held in Louisville, Kentucky, during the two weeks preceding the first Saturday in May, the day of the Kentucky Derby. The festival, Kentucky's largest single annual event, first ran from 1935 to ...

Queen earlier that year, she briefly considered a career in modeling. Instead, she and Collins married shortly after her graduation. While Billy Collins pursued a degree in dentistry

Dentistry, also known as dental medicine and oral medicine, is the branch of medicine focused on the teeth, gums, and mouth. It consists of the study, diagnosis, prevention, management, and treatment of diseases, disorders, and conditions of ...

at the University of Louisville

The University of Louisville (UofL) is a public research university in Louisville, Kentucky. It is part of the Kentucky state university system. When founded in 1798, it was the first city-owned public university in the United States and one ...

, Martha taught at Seneca and Fairdale high schools, both located in Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

.Ryan, p. 230 While living in Louisville, the couple had two children, Steve and Marla.

In 1966, the Collinses moved to Versailles, Kentucky

Versailles () is a home rule-class city in Woodford County, Kentucky, United States. It lies by road west of Lexington and is part of the Lexington-Fayette Metropolitan Statistical Area. Versailles has a population of 9,316 according to 2017 cen ...

, where Martha taught at Woodford County Junior High School. The couple became active in several civic organizations, including the Jaycees and Jayceettes and the Young Democratic Couples Club. Through the club, they worked on behalf of Henry Ward's unsuccessful gubernatorial campaign in 1967.

Early political career

By 1971, Collins was the president of the Jayceettes; through her work there, she came to the attention of Democratic

By 1971, Collins was the president of the Jayceettes; through her work there, she came to the attention of Democratic state senator

A state senator is a member of a state's senate in the bicameral legislature of 49 U.S. states, or a member of the unicameral Nebraska Legislature.

Description

A state senator is a member of an upper house in the bicameral legislatures of ...

Walter "Dee" Huddleston. Huddleston asked Collins to co-chair Wendell Ford

Wendell Hampton Ford (September 8, 1924 – January 22, 2015) was an American politician from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. He served for twenty-four years in the U.S. Senate and was the 53rd Governor of Kentucky. He was the first person to be ...

's gubernatorial campaign in the 6th District. J.R. Miller, then-chairman of the state Democratic Party, commented that "She organized that district like you wouldn't believe." After Ford's victory, he named Collins as a Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the governing body of the United States Democratic Party. The committee coordinates strategy to support Democratic Party candidates throughout the country for local, state, and national office, as well ...

woman from Kentucky. She quit her teaching job and went to work full-time at the state Democratic Party headquarters, as secretary of the state Democratic party and as a delegate to the 1972 Democratic National Convention

The 1972 Democratic National Convention was the presidential nominating convention of the Democratic Party for the 1972 presidential election. It was held at Miami Beach Convention Center in Miami Beach, Florida, also the host city of the Repub ...

. The following year, she worked for Huddleston's campaign for the U.S. Senate.

In 1975, Collins won the Democratic nomination for Clerk of the Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky.

Th ...

in a five-way primary. In the general election, she defeated Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Joseph E. Lambert by a vote of 382,528 to 233,442. During her term, an amendment to the state constitution changed the name of the Court of Appeals to the Kentucky Supreme Court

The Kentucky Supreme Court was created by a 1975 constitutional amendment and is the state supreme court of the U.S. state of Kentucky. Prior to that the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky. The Kentucky Court of ...

; Collins was the last person to hold the office of Clerk of the Court of Appeals and the first to hold the office of Clerk of the Supreme Court. As clerk, she compiled and distributed a brochure about the new role of the Supreme Court, and worked with the state department of education to create a teacher's manual for use in the public schools, detailing the changes effected in the court system as a result of the constitutional amendment. The Woodford County chapter of Business and Professional Women chose Collins as its 1976 Woman of Achievement, and in 1977, Governor Julian Carroll

Julian Morton Carroll (born April 16, 1931) is an American lawyer and politician from the state of Kentucky. A Democrat, he served as the 54th Governor of Kentucky from 1974 to 1979, succeeding Wendell H. Ford, who resigned to accept a seat ...

named her Kentucky Executive Director of the Friendship Force.

In a field that included six major candidates, Collins secured the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

in the 1979 primary, garnering 23 percent of the vote. She handily defeated Republican Hal Rogers

Harold Dallas Rogers (born December 31, 1937) is an American lawyer and politician serving his 21st term as the U.S. representative for , having served since 1981. He is a member of the Republican Party. Upon Don Young's death in 2022, Rogers b ...

in the general election 543,176 to 316,798. As lieutenant governor, she traveled the state, attending ceremonies in place of Democratic Governor John Y. Brown, Jr., who disliked such formal events and often chose not to attend.Ryan, p. 231 By the end of her term, she declared that she had visited all 120 counties in Kentucky. Governor Brown was frequently out of the state, leaving Collins as acting governor for more than 500 days of her four-year term.Harrison and Klotter, p. 417

As lieutenant governor, Collins presided over the state Senate. Members of both major parties praised Collins for her impartiality and knowledge of parliamentary procedure

Parliamentary procedure is the accepted rules, ethics, and customs governing meetings of an assembly or organization. Its object is to allow orderly deliberation upon questions of interest to the organization and thus to arrive at the sense ...

in this role. She was twice called upon to break tie votes in the Senate, once on a bill allowing the state's teachers to engage in collective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and rights for workers. The ...

and another on a bill to allow branch banking across county lines within the state; in both instances she voted in the negative, killing the bill. During her tenure, she also chaired the National Conference of Lieutenant Governors The National Lieutenant Governors Association (NLGA) is the non-profit, nonpartisan professional association for elected or appointed officials who are first in line of succession to the governors in the 50 U.S. states and the five organized terri ...

, becoming the first woman to hold that position. In 1982, she was named to the board of regents of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary (SBTS) is a Baptist theological institute in Louisville, Kentucky. It is affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention. The seminary was founded in 1859 in Greenville, South Carolina, where it was a ...

in Louisville."Ex-Governor Loses Board Post," ''The Kentucky Post''

Gubernatorial election of 1983

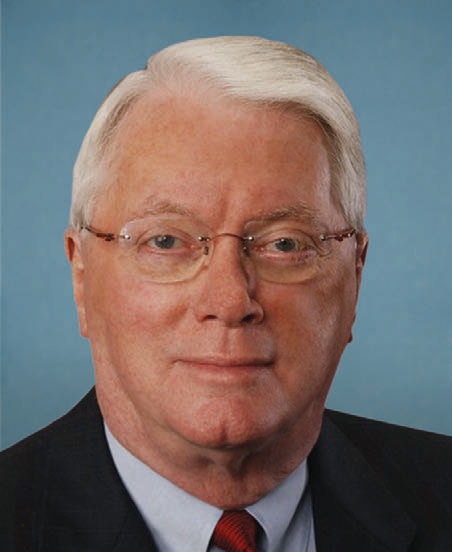

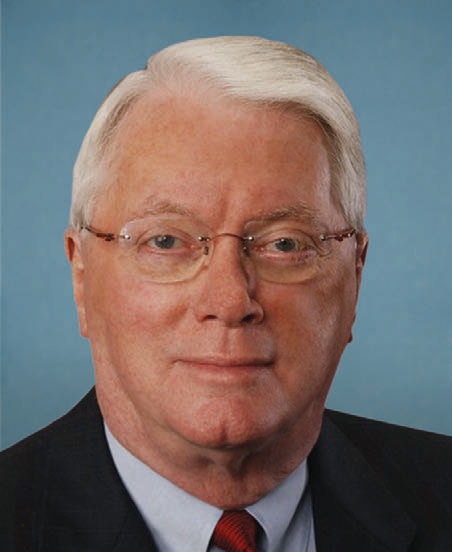

Nearing the end of her term as lieutenant governor, Collins announced her intent to run for governor in 1983. Her opponents for the Democratic nomination included Louisville mayor Harvey Sloane and Grady Stumbo, the former secretary of the state's Department of Human Resources. Collins had the support of many leaders in the Democratic Party, but just before the primary, Governor Brown endorsed Stumbo, charging that both Sloane and Collins would use their gubernatorial appointment power to dispense party patronage. Although this was a common practice at the time, Brown notably shunned it during his term.Osbourne, "Brown Gives Endorsement to Stumbo" With 223,692 votes, Collins edged out Sloane (219,160 votes) and Stumbo (199,795 votes) to secure the nomination. Sloane asked for a recanvass of the ballots, but ultimately decided it would not change the outcome and conceded defeat.Jester, "Harvey Sloane Concedes Loss in May Primary," 1983 In the general election, Collins faced Republican state senator Jim Bunning, who was later elected to the

In the general election, Collins faced Republican state senator Jim Bunning, who was later elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum is a history museum and hall of fame in Cooperstown, New York, operated by private interests. It serves as the central point of the history of baseball in the United States and displays baseball-r ...

for his achievements as a professional pitcher

In baseball, the pitcher is the player who throws ("pitches") the baseball from the pitcher's mound toward the catcher to begin each play, with the goal of retiring a batter, who attempts to either make contact with the pitched ball or dr ...

. The National Organization for Women

The National Organization for Women (NOW) is an American feminist organization. Founded in 1966, it is legally a 501(c)(4) social welfare organization. The organization consists of 550 chapters in all 50 U.S. states and in Washington, D.C. It ...

, the National Women's Campaign Fund, and the Women's Political Caucus all refused to endorse Collins, citing her lukewarm support for the Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution designed to guarantee equal legal rights for all American citizens regardless of sex. Proponents assert it would end legal distinctions between men and ...

and her opposition to abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pre ...

except in cases of rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ...

, incest

Incest ( ) is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by affinity ( marriage or stepfamily), ado ...

, or when the mother's life was in danger.Smith, "Mondale Stays Neutral on Female Running Mate" But, Bunning was not personable on the campaign trail and had difficulty finding issues that would draw traditionally Democratic voters to him.Harrison and Klotter, p. 418 His Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

was a political liability among the majority-Protestant voters. Collins won the election by a vote of 561,674 to 454,650, becoming the first, and to date only, woman to be elected governor of Kentucky.

Following her election, Collins donated the surplus $242,000 from her campaign coffers to the state Democratic Party. When Collins's husband was named state treasurer for the party – at an annual salary of $59,900 – the state press charged that the move was a plot to funnel Collins's campaign funds into her personal account. (The previous Democratic state treasurer had received no salary during his tenure.) Following the media criticism, Dr. Collins resigned his post as treasurer. All of the involved individuals insisted that Governor Collins had not been briefed on the details of her husband's appointment. The media's criticism of Collins continued as many of the appointments to her executive cabinet went to what they characterized as inexperienced personnel who had held key positions in her past campaigns. When newly appointed Insurance Commissioner Gilbert McCarty approved a 17% rate increase requested by Blue Cross Blue Shield

Blue Cross Blue Shield Association (BCBS, BCBSA) is a federation, or supraorganization, of, in 2022, 34 independent and locally operated BCBSA companies that provide health insurance in the United States to more than 106 million people. It was ...

– a request that his predecessor had denied a few days earlier – Collins quickly countermanded the approval pending a public hearing on the matter.Halsey, "Woman Ky. Governor is Off to a Rough Start"

Governor

In her first address to the legislature, Collins asked for an additional $324 million from theKentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It comprises the Kentucky Senate and the Kentucky House of Representatives.

The General Assembly meets annually in ...

, most of it allocated for education. The additional revenue was to be derived from Collins's proposed tax package, which included increasing the income tax on individuals making more than $15,000 annually, extending the sales tax

A sales tax is a tax paid to a governing body for the sales of certain goods and services. Usually laws allow the seller to collect funds for the tax from the consumer at the point of purchase. When a tax on goods or services is paid to a gove ...

to cover services such as auto repair and dry cleaning, and increasing the corporate licensing tax.Osbourne, "Collins Urges Tax Increase to Aid Schools" After opposition to her proposal developed among legislators during the 1984 biennial legislative session, Collins revised the tax package. She retained the corporate licensing tax increase, but replaced the sales tax and income tax modifications with a flat five percent personal income tax and phasing out the deductions for depreciation

In accountancy, depreciation is a term that refers to two aspects of the same concept: first, the actual decrease of fair value of an asset, such as the decrease in value of factory equipment each year as it is used and wear, and second, the ...

which corporations could claim on their state taxes.Osbourne, "Collins Says 'I've Got to Have' Proposals on Revenue, Education"

With the state still recovering from an economic recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction when there is a general decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be triggered by variou ...

and an election year upcoming, legislators refused to raise taxes. Collins eventually withdrew her request and submitted a continuation budget instead. Some education proposals advocated by Collins were passed, including mandatory kindergarten

Kindergarten is a preschool educational approach based on playing, singing, practical activities such as drawing, and social interaction as part of the transition from home to school. Such institutions were originally made in the late 18th cen ...

, remedial programs for elementary school children, mandatory testing and internship for teachers, and the implementation of academic receivership for underperforming schools.Ryan, p. 233 Among the other accomplishments of the 1984 legislative session were passage of a tougher drunk driving

Drunk driving (or drink-driving in British English) is the act of driving under the influence of alcohol. A small increase in the blood alcohol content increases the relative risk of a motor vehicle crash.

In the United States, alcohol is i ...

law, and a measure allowing state banking companies to purchase other banks within the state.

Consideration for vice-president

By virtue of her election as Kentucky's governor, Collins became the highest-ranking Democratic woman in the nation.York, "Victory Gives Collins Spot in the National Political Arena" The only two women in the U.S. Senate at the time were Republicans, and Collins was the only woman governor of any state. Shortly after her election, she appeared on ''

By virtue of her election as Kentucky's governor, Collins became the highest-ranking Democratic woman in the nation.York, "Victory Gives Collins Spot in the National Political Arena" The only two women in the U.S. Senate at the time were Republicans, and Collins was the only woman governor of any state. Shortly after her election, she appeared on ''Good Morning America

''Good Morning America'' (often abbreviated as ''GMA'') is an American morning television program that is broadcast on ABC. It debuted on November 3, 1975, and first expanded to weekends with the debut of a Sunday edition on January 3, 1993. ...

'', where she was asked about her interest in the vice-presidency and gave a non-committal answer. Four days after her inauguration as governor, she was chosen to deliver the Democratic response to President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

's weekly radio address.York, "Collins Delivers Democrats' Reply to Reagan Speech" At a news conference following her speech, Collins was asked again if she would be willing to be considered as the Democrats' vice-presidential candidate in the upcoming election; she replied "No, not at this time."

In mid-1984, the Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the governing body of the United States Democratic Party. The committee coordinates strategy to support Democratic Party candidates throughout the country for local, state, and national office, as well ...

chose Collins to preside over the 1984 Democratic National Convention

The 1984 Democratic National Convention was held at the Moscone Center in San Francisco, California from July 16 to July 19, 1984, to select candidates for the 1984 United States presidential election. Former Vice President Walter Mondale was nom ...

in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

. This engagement prevented Collins from chairing the state delegation to the convention, as was typical of governors.Osbourne, "Collins's Son to Head Convention Delegation" The party appointed Collins's son, Steve as state chair. Prior to the convention, Walter Mondale

Walter Frederick "Fritz" Mondale (January 5, 1928 – April 19, 2021) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 42nd vice president of the United States from 1977 to 1981 under President Jimmy Carter. A U.S. senator from Minnesota ...

, the presumptive presidential nominee, interviewed Collins as a possible vice-presidential candidate before choosing Geraldine Ferraro

Geraldine Anne Ferraro (August 26, 1935 March 26, 2011) was an American politician, diplomat, and attorney. She served in the United States House of Representatives from 1979 to 1985, and was the Democratic Party's vice presidential nominee ...

as his running mate. A writer for ''The Miami Herald

The ''Miami Herald'' is an American daily newspaper owned by the McClatchy Company and headquartered in Doral, Florida, a city in western Miami-Dade County and the Miami metropolitan area, several miles west of Downtown Miami.Eichel, "How Mondale Decided on Ferraro"

After fulfilling her one-year commitment to the University of Louisville, Collins was named a fellow of the

After fulfilling her one-year commitment to the University of Louisville, Collins was named a fellow of the

Education proposals

In January 1985, Collins renewed her push for additional education funding and changes by appointing herself secretary of the state Education and Humanities Cabinet.Roser, "Collins Picks Self as Chief of Education" Following the announcement, Collins and several key legislators held a series of meetings in every county, advocating for her proposed changes and seeking information about what types of changes the state's citizens desired.Osbourne, "Collins, Legislators Begin Campaign" At the meetings, Collins was careful to separate the issues of her proposed education plan and potential tax increases. She believed that opposition to increased taxes had prevented her previous package from being enacted. Collins announced a new education package in June 1985 that included a five percent across-the-board pay raise for teachers, a reduction in class sizes, funding for construction projects, aides for every kindergarten teacher in the state, and a "power equalization" program to make funding for poorer school districts more equal to that of their more affluent counterparts.Roser, "Governor Urges Legislators to Back Plan" After favorable reaction to the plan from legislators, she called a special legislative session to convene July 8 to consider the plan.Brammer, "Session Call Includes More Than Expected" After two weeks of deliberation, the General Assembly approved Collins's education plan, tripling the corporate licensing tax to $2.10 per $1,000 in order to pay for the package.Roser, "Education Reforms to Begin Gradually" The Assembly rejected a proposed five-cents-per-gallon increase in the stategasoline tax

A fuel tax (also known as a petrol, gasoline or gas tax, or as a fuel duty) is an excise tax imposed on the sale of fuel. In most countries the fuel tax is imposed on fuels which are intended for transportation. Fuels used to power agricultural ...

to finance other spending.Brammer, "Roads, Prisons, Child-Abuse Issues Linger"

Collins followed up her success in the 1985 special session with a push for more higher education funding in the 1986 legislative session. Lawmakers obliged by approving an additional $100 million for higher education in the biennial budget. They also approved implementation of a pilot preschool program and the purchase of new reading textbooks, but failed to act on Collins's request for an additional $3.9 million to improve the state's vocational education

Vocational education is education that prepares people to work as a technician or to take up employment in a skilled craft or trade as a tradesperson or artisan. Vocational Education can also be seen as that type of education given to an i ...

system. Legislators approved calling a referendum on a constitutional amendment – supported by Collins – to make the state superintendent of education an appointive, rather than elective, office.Roser, Duke, and Brammer, "'86 Legislature Called Both Independent, Cautious" The amendment was defeated by the state's voters in November 1986, despite a Collins-led campaign in favor of it.Rugeley and Wagar, "Rural Areas Killed Effort to Appoint School Chief" The increased corporate tax intended to cover the cost of the increased education budget was, however, inadequate. In 1987, a plan to increase revenue through changes in the state income tax was abandoned when Wallace Wilkinson

Wallace Glenn Wilkinson (December 12, 1941 – July 5, 2002) was an American businessman and politician from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. From 1987 to 1991, he served as the state's 57th governor. Wilkinson dropped out of college at the Unive ...

, the Democratic gubernatorial nominee who would go on to succeed Collins, announced his opposition to it.

Toyota Assembly Plant

In March 1985, Collins embarked on the first of severaltrade mission

Trade mission is an international trip by government officials and businesspeople that is organized by agencies of national or provincial governments for purpose of exploring international business opportunities. Business people who attend trade m ...

s to Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

."Collins's China Trip to be First for State". ''Lexington Herald-Leader'' She returned there in October 1985, and also visited China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

– a first for any Kentucky governor – to encourage opening Chinese markets for Kentucky goods and to establish a "sister state" relationship with China's Jiangxi

Jiangxi (; ; formerly romanized as Kiangsi or Chianghsi) is a landlocked province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north int ...

province. Collins's efforts in Japan yielded her most significant accomplishment as governor – convincing Toyota

is a Japanese multinational automotive manufacturer headquartered in Toyota City, Aichi, Japan. It was founded by Kiichiro Toyoda and incorporated on . Toyota is one of the largest automobile manufacturers in the world, producing about 10 ...

to locate an $800 million manufacturing plant in Georgetown.Truman, "Toyota to Get $125 Million in Incentives, Collins Says" According to published reports, the Kentucky location was chosen over proposed sites in Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

, Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

, Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

, and Kansas

Kansas () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its Capital city, capital is Topeka, Kansas, Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita, Kansas, Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebras ...

."Toyota Site Delegation is Given Real Bang-up Welcome by Collins". ''Lexington Herald-Leader''

The agreement with Toyota was contingent upon legislative approval of $125 million in incentives promised to Toyota by Collins and state Commerce Secretary Carroll Knicely. They included $35 million to buy and improve a tract to be given to Toyota for the plant, $33 million for initial training of employees, $10 million for a skills development center for employees, and $47 million in highway improvements near the site. The incentive package was approved in the 1986 legislative session. State Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

David L. Armstrong

David Lawrence Armstrong (August 6, 1941 – June 15, 2017) was an American politician. He served as the mayor of Louisville, Kentucky from 1999 to 2003. He was the city's last mayor before its merger with Jefferson County to form Louisville M ...

expressed concerns that the incentives might conflict with the state constitution by giving gifts from the state treasury to a private business, but concluded that the General Assembly had made "a good-faith effort to be in compliance with the constitution".Brammer, "Collins Signs Final Accord With Toyota on Incentives"

Given Armstrong's concerns, the administration employed general counsel J. Patrick Abell to file a friendly test case

In software engineering, a test case is a specification of the inputs, execution conditions, testing procedure, and expected results that define a single test to be executed to achieve a particular software testing objective, such as to exercise ...

to determine the constitutionality of the incentive package.Duke, "State Files Test Suit on Toyota" While the suit was pending, the ''Lexington Herald-Leader

The ''Lexington Herald-Leader'' is a newspaper owned by the McClatchy Company and based in Lexington, Kentucky. According to the ''1999 Editor & Publisher International Yearbook'', the paid circulation of the ''Herald-Leader'' is the second larg ...

'' reported that the administration had failed to include the interest on the bonds used to finance the expenditures in its estimation of the cost; this, plus the cost overruns reported by the ''Herald-Leader'', had already pushed the total cost of the package to about $354 million by late September 1986.Miller and Swasy, "The Wooing of Toyota: Kentucky Adds Up the Bill" In October, Toyota agreed to cover the cost overruns associated with preparing the site for construction.Swasy, "Toyota Promises to Help Pay Cost Overruns"

Opponents of the economic enticements for Toyota joined the state's test suit.Brammer and Miller, "Toyota Incentives Legal, Court Rules" In October 1986, Franklin County Circuit Court Judge Ray Corns issued an initial ruling that the package did not violate the state constitution, but both sides asked the Kentucky Supreme Court to make a final decision. On June 11, 1987, the Kentucky Supreme Court ruled 4–3 that the package served a public purpose and were therefore constitutional.

Shortly after the announcement that Toyota was moving to Georgetown Collins, in her capacity as governor, condemned a portion of land belonging to real estate developer Gordon Taub. Taub owned within the Toyota plant site and were condemned to build a four-lane highway to the Toyota plant entrance. Taub challenged the condemnation, stating that the Commonwealth did not have the right to condemn private property for the use of a for profit, public corporation. At trial, Collins became the first sitting governor of Kentucky to testify in court. She was represented by former governor Bert T. Combs

Bertram Thomas Combs (August 13, 1911 – December 4, 1991) was an American jurist and politician from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. After serving on the Kentucky Court of Appeals, he was elected the 50th Governor of Kentucky in 1959 on his sec ...

; Taub was represented by former governor Louie B. Nunn

Louie Broady Nunn (March 8, 1924 – January 29, 2004) was an American politician who served as the 52nd governor of Kentucky. Elected in 1967, he was the only Republican to hold the office between the end of Simeon Willis's term in 1947 and ...

. This was also the first time in the history of Kentucky that two former governors represented opposing parties in a legal action.

Later, Toyota set up several assembly plants across the state; near the end of Collins's term, the state Commerce Cabinet reported that 25 automotive-related manufacturing plants had been constructed in 17 counties since the Toyota announcement.Rugeley and Brammer, "After Shaky Start, Collins Converted the Skeptics"

In 1987, Collins promised $10 million in state aid to Ford to incentivize the company to expand its truck assembly plant in Louisville."Ford to Expand Plant in Louisville". ''The New York Times'' The state experienced record job growth under Collins's economic development plan, which included attempts to attract both domestic and international companies. The state's unemployment rate fell from 9.7 percent in October 1983 to 7.2 percent in October 1987; according to the administration's own figures, they created a net increase of 73,000 jobs in the state during Collins's tenure.

Other matters during Collins's term

On October 7, 1987, Collins called a special legislative session to close a deficit between state contributions to theworker's compensation

Workers' compensation or workers' comp is a form of insurance providing wage replacement and medical benefits to employees injured in the course of employment in exchange for mandatory relinquishment of the employee's right to sue his or her emp ...

Special Fund and disbursements.Rugeley and Brammer, "Lawmakers Summoned on Workers' Comp Woes" The Special Fund was designated for payments to workers with occupational disease

An occupational disease is any chronic ailment that occurs as a result of work or occupational activity. It is an aspect of occupational safety and health. An occupational disease is typically identified when it is shown that it is more prevalen ...

s and workers whose work-related injuries could not be traced to any single employer.Brammer and Miller, "Lawmakers Compromise, Pass Workers' Comp Plan" A plan proposed by Democratic state senator Ed O'Daniel was expected to provide the framework for legislation considered in the session. Under O'Daniel's plan, additional revenue for the Special Fund would be raised by increasing assessments on worker's compensation premiums for 30 years. Assessments for coal companies were increased more than those on other businesses because the majority of the claims paid from the Special Fund were for black lung, a breathing disease common among coal miners; consequently, it was opposed by legislators from heavily coal-dependent counties. Nevertheless, after nine days of negotiations, a bill substantially similar to O'Daniel's original plan was approved by the legislature and signed by Collins.

Collins chaired the Tennessee–Tombigbee Waterway

The Tennessee–Tombigbee Waterway (popularly known as the Tenn-Tom) is a artificial U.S. waterway built in the 20th century from the Tennessee River to the junction of the Black Warrior-Tombigbee River system near Demopolis, Alabama. The Tenne ...

Authority and held that position when the waterway opened to the public in 1985."Kentucky Governor Martha Layne Collins". National Governors Association On May 10, 1985, she was named to the University of Kentucky Alumni Association's Hall of Distinguished Alumni. She also chaired the Southern Growth Policies Board, Southern States Energy Board, and was co-chair of the Appalachian Regional Commission

The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) is a United States federal–state partnership that works with the people of Appalachia to create opportunities for self-sustaining economic development and improved quality of life. Congress established A ...

.

Activities after leaving office

Collins's term expired on December 8, 1987, and under the restrictions then present in the Kentucky Constitution, she was ineligible for consecutive terms.Berman, "Out of the Mansion, Back in the Classroom" In 1988, she accepted a position as "executive in residence" at the University of Louisville, giving guest lectures to students in the university's business classes. She also started an international trade consulting firm in Lexington. WhenWestern Kentucky University

Western Kentucky University is a public university in Bowling Green, Kentucky. It was founded by the Commonwealth of Kentucky in 1906, though its roots reach back a quarter-century earlier. It operates regional campuses in Glasgow, Elizabethtow ...

president Kern Alexander

Samuel Kern Alexander Jr. is Professor of Excellence at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where he is endowed by the O'Leary Endowment and Editor of the ''Journal of Education Finance'', published by the University of Illinois Press and ...

resigned to accept a position at Virginia Tech

Virginia Tech (formally the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University and informally VT, or VPI) is a public land-grant research university with its main campus in Blacksburg, Virginia. It also has educational facilities in six re ...

in 1988, Collins was among four finalists to succeed him.Pack, "Owensboro Native Picked to Lead WKU" Some faculty members publicly expressed concerns about Collins's lack of experience in academia, and she withdrew her name from consideration shortly before the new president was announced.

After fulfilling her one-year commitment to the University of Louisville, Collins was named a fellow of the

After fulfilling her one-year commitment to the University of Louisville, Collins was named a fellow of the Harvard Institute of Politics

The Institute of Politics (IOP) is an institute of Harvard Kennedy School at Harvard University that was created to serve as a living memorial to President John F. Kennedy, as well as to inspire Harvard undergraduates to consider careers in politi ...

' John F. Kennedy School of Government, teaching non-credit classes on leadership styles once a week.Fortune, "A Time to Reflect, A Time to Choose" Concurrent with her position at Harvard, Collins was named to the board of regents for Midway College in 1989; the following year, she was removed from the board of regents of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary."Midway College Elects Trustees". ''Lexington Herald-Leader'' Her removal was automatically triggered after she missed three consecutive board meetings between 1986 and 1989. In 1990, Collins accepted the presidency of Saint Catharine College in Springfield, Kentucky

Springfield is a List of cities in Kentucky, home rule-class city in and county seat of Washington County, Kentucky, Washington County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 2,846 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census.

History

Spring ...

, becoming the first president of the small, Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

college who was not a Dominican nun.Lucke and Mead, "Collins Named College President" College officials stated that Collins was recruited for the presidency to raise the college's profile.

In 1993, Collins's husband, Bill, was charged in an influence-peddling scandal. The prosecution claimed that while Collins was governor, Dr. Collins exploited a perception that he could influence the awarding of state contracts through his wife.Wolfe, "Bill Collins Sentenced to 5 Years and 3 Months in Prison, Fined" It was alleged that he exploited this perception to pressure people who did business with the state to invest nearly $2 million with him. He was convicted on October 14, 1993, after a seven-week trial; he was given a sentence of five years and three months in federal prison, which was at the low end of the range prescribed by the federal sentencing guidelines

The United States Federal Sentencing Guidelines are rules published by the U.S. Sentencing Commission that set out a uniform policy for sentencing individuals and organizations convicted of felonies and serious (Class A) misdemeanors in the Uni ...

."Former Governor's Husband Gets Jail Term for Extortion". ''The New York Times'' He was also fined $20,000 for a conspiracy charge that involved kickbacks

A kickback is a form of negotiated bribery in which a commission is paid to the bribe-taker in exchange for services rendered. Generally speaking, the remuneration (money, goods, or services handed over) is negotiated ahead of time. The kickbac ...

disguised as political contributions. Governor Collins was called to testify in the trial, but was not charged. The scandal tarnished her image, however, and may have cost her an appointment in the administration of President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again ...

. Collins was also rumored to be considering running for the U.S. Senate, a bid which never materialized following her husband's conviction. The Collinses reunited following Dr. Collins's release from prison on October 10, 1997."Ex-governor's Husband Takes Job at Georgetown". ''The Kentucky Post''

In 1996, Collins resigned as president of Saint Catharine College to direct the International Business and Management Center at the University of Kentucky."Collins going to UK". ''The Kentucky Post'' Later that year, she was a co-chair of the Credentials Committee at the Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 18 ...

."Former Fellow: Martha Layne Collins". Harvard University Institute of Politics When her contract with the University of Kentucky expired in 1998, Collins took a part-time position as "executive scholar in residence" at Georgetown College, which allowed her more time to pursue other interests."Ex-Governor Trades UK Position for Georgetown". ''Lexington Herald-Leader'' In 1999, she was named Honorary Consul General of Japan in Kentucky, a position which involved promoting Japanese interests in Kentucky, encouraging Japanese investment in the state, and encouraging cultural understanding between Kentucky and Japan.Honeycutt, "Japan Names Ex-Governor Collins to Consul Post" In 2001, Governor Paul E. Patton named her co-chair of the Kentucky Task Force on the Economic Status of Women.Ryan, p. 235 In January 2005, she became the chairwoman and chief executive officer

A chief executive officer (CEO), also known as a central executive officer (CEO), chief administrator officer (CAO) or just chief executive (CE), is one of a number of corporate executives charged with the management of an organization especiall ...

of the Kentucky World Trade Center."Martha Layne Collins". Education Hall of Fame She has held positions on the boards of directors for several corporations, including Eastman Kodak

The Eastman Kodak Company (referred to simply as Kodak ) is an American public company that produces various products related to its historic basis in analogue photography. The company is headquartered in Rochester, New York, and is incorpor ...

.

Awards and honors

Women Leading Kentucky, a non-profit group designed to promote education, mentorship, and networking among Kentucky professional women, created the Martha Layne Collins Leadership Award in 1999 to recognize "a Kentucky woman of achievement who inspires and motivates other women through her personal, community and professional lives"; Collins was the first recipient of the award."Eastern Kentucky University's Shain Receives Martha Layne Collins Leadership Award". U.S. Federal News Service In 2003, Kentucky's Bluegrass Parkway was renamed the Martha Layne Collins Bluegrass Parkway in her honor; Collins also received the World Trade Day Book of Honor Award for the state of Kentucky from theWorld Trade Centers Association

The World Trade Centers Association (WTCA) was founded in 1970 by Port Authority executive Guy F. Tozzoli. WTCA is a not-for-profit, non-political association dedicated to the establishment and operation of World Trade Centers (WTCs) as instrument ...

that year.Kocher, "Parkway to be Named for Collins" In 2009, she was inducted into the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs

The is an executive department of the Government of Japan, and is responsible for the country's foreign policy and international relations.

The ministry was established by the second term of the third article of the National Government Organ ...

for her contributions "to strengthening economic and cultural exchanges between Japan and the United States of America"."2009 Autumn Conferment of Decorations on Foreign Nationals". Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs Martha Layne Collins High School

Martha Layne Collins High School is a high school located in Shelbyville, Kentucky, United States and is a part of the Shelby County Public School District. Commonly referred to as Collins High School, the school is named after Martha Layne Col ...

in Shelby County was named in her honor and opened in 2010.

See also

*List of female governors in the United States

As of November 2022, 45 women have served or are serving as the governor of a U.S. state (two acting governors due to vacancies) and three women have served or are serving as the governor of an unincorporated U.S. territory. Two women have ser ...

*List of female lieutenant governors in the United States

As of January 18, 2023, there are 22 women currently serving (excluding acting capacity) as lieutenant governors in the United States. Overall, 118 women have served (including acting capacity).

Women have been elected lieutenant governor from 4 ...

*Kentucky Colonel

Kentucky Colonel is the highest title of honor bestowed by the Commonwealth of Kentucky, and is the most well-known of a number of honorary colonelcies conferred by United States governors. A Kentucky Colonel Commission (the certificate) i ...

<--(an article which features a photo of a certificate containing the name of Martha Layne Collins, including a gold colored seal and a double blue ribbon)

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Collins, Martha Layne 1936 births Heads of universities and colleges in the United States Baptists from Kentucky Democratic Party governors of Kentucky Georgetown College (Kentucky) faculty Lieutenant Governors of Kentucky Living people People from Shelbyville, Kentucky People from Versailles, Kentucky Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food, and Environment alumni Women in Kentucky politics Women state governors of the United States Kentucky women entrepreneurs Women heads of universities and colleges Schoolteachers from Kentucky Kentucky women in education American women academics 20th-century American politicians 20th-century American women politicians 21st-century American women