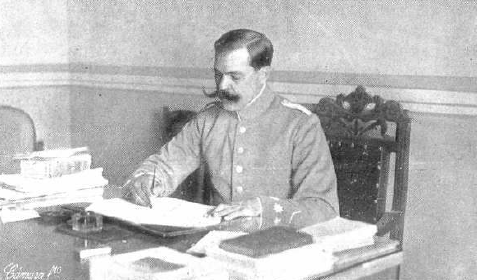

Manuel Fernández Silvestre on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Manuel Fernández Silvestre (December 16, 1871 – July 22, 1921) was a

After stopping in

After stopping in  Silvestre had spread out his troops in 144 forts and blockhouses (''blocaos'') from Sidi Dris on the Mediterranean across the Riff to Annual and Tizi Azza and on to Melilla. A typical blockhouse held about a dozen men while the larger forts had about 800 men. Silvestre, again demonstrating his boldness and impetuosity, had pushed his men too deep into the mountains hoping to reach Alhucemas Bay without undertaking the necessary work to built a logistical support network capable of supplying his men out in the ''blocaos'' up in the Riff mountains. Krim had sent Silvestre a letter warning him not to cross the Amekran River, as he would likely die. Silvestre commented to the Spanish press about the letter: "This man Abd el-Krim is crazy. I'm not going to take seriously the threats of a little Berber ''caid'' udgewhom I had at my mercy a short time ago. His insolence merits a new punishment". Krim allowed Silvestre to advance deep into since he knew that the Spanish logistics were, in the words of the Spanish historian Jose Alvarez, "tenuous" at best.

In late May 1921, Silvestre had his first inking of trouble, as he received reports that his supply columns he was sending up into the Riff were regularly being destroyed. As Silvestre had pushed his men very deep into the Riff, and his forts and ''blocaos'' held little in the way of food, the ambushes threatened to bring down the entire chain that Silvestre had built. On 29 May 1921, Silvestre wrote to Berenguer for the first time that the campaign against Krim might be more than a "mere kick in the pants" and that he needed more troops fast. However, in the words of Perry, "this stupid man" marched across the Amekran River to occupy the village Abaran on June 1, 1921. Most of the soldiers were ''regulares'' who promptly

Silvestre had spread out his troops in 144 forts and blockhouses (''blocaos'') from Sidi Dris on the Mediterranean across the Riff to Annual and Tizi Azza and on to Melilla. A typical blockhouse held about a dozen men while the larger forts had about 800 men. Silvestre, again demonstrating his boldness and impetuosity, had pushed his men too deep into the mountains hoping to reach Alhucemas Bay without undertaking the necessary work to built a logistical support network capable of supplying his men out in the ''blocaos'' up in the Riff mountains. Krim had sent Silvestre a letter warning him not to cross the Amekran River, as he would likely die. Silvestre commented to the Spanish press about the letter: "This man Abd el-Krim is crazy. I'm not going to take seriously the threats of a little Berber ''caid'' udgewhom I had at my mercy a short time ago. His insolence merits a new punishment". Krim allowed Silvestre to advance deep into since he knew that the Spanish logistics were, in the words of the Spanish historian Jose Alvarez, "tenuous" at best.

In late May 1921, Silvestre had his first inking of trouble, as he received reports that his supply columns he was sending up into the Riff were regularly being destroyed. As Silvestre had pushed his men very deep into the Riff, and his forts and ''blocaos'' held little in the way of food, the ambushes threatened to bring down the entire chain that Silvestre had built. On 29 May 1921, Silvestre wrote to Berenguer for the first time that the campaign against Krim might be more than a "mere kick in the pants" and that he needed more troops fast. However, in the words of Perry, "this stupid man" marched across the Amekran River to occupy the village Abaran on June 1, 1921. Most of the soldiers were ''regulares'' who promptly  The Spanish garrison at Igueriben was cut off but could communicate with the fort at Annual via

The Spanish garrison at Igueriben was cut off but could communicate with the fort at Annual via

Next publication of Abd el-Krim's biography in base of official Spanish documents

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

general

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

.

Silvestre was the son of a lieutenant colonel of artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

, Victor Fernández and Eleuteria Silvestre. In 1889 he enrolled in the Toledo Infantry Academy, where he met with the future high commissioner of Spanish Morocco, Dámaso Berenguer

Dámaso Berenguer y Fusté, 1st Count of Xauen (4 August 1873 – 19 May 1953) was a Spanish general and politician. He served as Prime Minister during the last thirteen months of the reign of Alfonso XIII.

Biography

Berenguer was born in Sa ...

.

He served as commander of the Spanish enclaves

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

in Morocco: Ceuta

Ceuta (, , ; ar, سَبْتَة, Sabtah) is a Spanish autonomous city on the north coast of Africa.

Bordered by Morocco, it lies along the boundary between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. It is one of several Spanish territorie ...

from 1919 to 1920 and of Melilla from 1920 to 1921. Afterward he commanded all Spanish armies in Africa during the opening phase of the Riff War

The Rif War () was an armed conflict fought from 1921 to 1926 between Spain (joined by France in 1924) and the Berber tribes of the mountainous Rif region of northern Morocco.

Led by Abd el-Krim, the Riffians at first inflicted several defe ...

in which he suffered a massive and disastrous defeat at Annual. With the battle lost, Silvestre was either killed or committed suicide on July 22, 1921. This is today considered one of the worst defeats ever suffered by the contemporary Spanish army.

Biography

Youth

Silvestre was born in El Caney in Spanish Cuba to the second marriage of his father, artillery lieutenant colonel Victor Fernandez y Pentiaga and his mother Eleuteria Silvestre Quesada. Silvestre joined the Toledo General Military Academy where he met future General and Prime Minister Damaso Berenguer y Fuste who was 2 years younger than Silvestre. Silvestre graduated on March 9, 1893, as a cavalry second lieutenant, aged 21.Career

Cuba

Silvestre first saw military action in 1890 at the age of 19 in a skirmish as a cadet against the '' Mambises'' guerrillas which were seeking independence for Cuba. In February 1895, a full-blown rebellion broke out, known as the Cuban War of Independence. After he concluded the academy, Silvestre returned to Cuba in 1895 to fight against the ''Mambises'' until the Spanish lost the 1898Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

in which he suffered 16 wounds, including a severe wound that led to an incapacity of the left arm, which, in the future, he disguised very well. During his time in Cuba, the aggressive Silvestre had a marked preference for cavalry charges and fighting hand to hand against the ''Mambises.'' He was widely liked and respected by the men under his command.

A charismatic, charming man whose nickname was Manolo, Silvestre was a great womanizer who fathered scores of illegitimate children by the various women he seduced. In the words of the American historian David Woolman: "Silvestre was a real-life character as flamboyant as any to be found in the pages of a romantic novel". Silvestre was a very brave but reckless junior officer in Cuba, where he was seriously wounded during a cavalry action, as a general though, he would be seen as hopelessly inept. His rapid rise in the ranks of the Spanish army was often attributed patronage of his best friend, King Alfonso XIII

Alfonso XIII (17 May 1886 – 28 February 1941), also known as El Africano or the African, was King of Spain from 17 May 1886 to 14 April 1931, when the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed. He was a monarch from birth as his father, Alf ...

, who used his position as commander-in-chief to promote his favorite officers. After the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

, Silvestre served as a military aide to the king, who became his patron. When Alfonso ascended to the Spanish throne in 1886, Spain could still be considered a world power, as Spain owned colonies in the Americas, Africa, Asia and the Pacific. The Spanish American War of 1898 was a traumatic event in Alfonsoäs childhood, which saw Spain defeated by the Americans followed by the loss of Cuba, Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and unincorporated ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, and Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

, and shortly afterward, Spain sold the Carolines and Mariana islands to Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. As a result, Spain's empire now consisted only of Spanish Guinea, in Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo ...

, and some footholds on the Moroccan coast. Alfonso had taken the losses of the Spanish–American War very badly and supported the ''africanistas'', who longed to conquer new imperial colonies in Northern Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in t ...

for Spain, to compensate for the lost colonies in the Americas and Asia. As a militarist educated by army officers and an ''africanista'', Alfonso favoured ''swashbuckling'', macho generals who he saw as potential conquerors of Africa; This is the reason why Silvestre, as such a general became a royal favourite. Alfonso was fascinated by Silvestre's flamboyant and colorful personality, which made him popular "both with his troops and with the ladies."

Spanish Morocco

In 1904, after many posts in peninsularregiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscript ...

s, he was dispatched to the Spanish exclave of Melilla on the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

Riff

A riff is a repeated chord progression or refrain in music (also known as an ostinato figure in classical music); it is a pattern, or melody, often played by the rhythm section instruments or solo instrument, that forms the basis or acc ...

coast of North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, where he proved to be an excellent negotiator but a fierce and an unpredictable man as well. In 1912, he occupied Larache

Larache ( ar, العرايش, al-'Araysh) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast, where the Loukkos River meets the Atlantic Ocean. Larache is one of the most important cities of the Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region.

Man ...

and in 1918, he became the Commandant-General

Commandant-general is a military rank in several countries and is generally equivalent to that of major-general.

Argentina

Commandant general is the highest rank in the Argentine National Gendarmerie, and is held by the national director of the g ...

of Ceuta

Ceuta (, , ; ar, سَبْتَة, Sabtah) is a Spanish autonomous city on the north coast of Africa.

Bordered by Morocco, it lies along the boundary between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. It is one of several Spanish territorie ...

. As such he reported to the High Commissioner, a position that was filled by Dámaso Berenguer

Dámaso Berenguer y Fusté, 1st Count of Xauen (4 August 1873 – 19 May 1953) was a Spanish general and politician. He served as Prime Minister during the last thirteen months of the reign of Alfonso XIII.

Biography

Berenguer was born in Sa ...

. Silvestre and Berenguer had once been friends at the military school, but they had fallen out as Silvestre was senior on the officer's list and yet had to take orders from Berenguer due to his post as High Commissioner. Berenguer regarded Silvestre as reckless but was unwilling to rein him in largely because his friendship with the king, who had the final say over who was promoted and when. Silvestre led several campaigns against Mulai Ahmed er Raisuni

Mulai Ahmed er Raisuni (Arabic: "مولاي أحمد الريسوني", known as Raisuli to most English speakers, also Raissoulli, Rais Uli, and Raysuni; 1871 – April 1925) was a Sharif (descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad), and a leader ...

, a notorious North Moroccan brigand, from 1913 to 1920. After a long struggle, Silvestre defeated Raisuni in October 1919 in the Battle of Fondak Pass. Although Raisuni and most of his troops managed to slip away, they eventually joined forces with the Spanish authority against rival rebel leader Abd el-Krim

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Karim al-Khattabi (; Tarifit: Muḥend n Ɛabd Krim Lxeṭṭabi, ⵎⵓⵃⵏⴷ ⵏ ⵄⴰⴱⴷⵍⴽⵔⵉⵎ ⴰⵅⵟⵟⴰⴱ), better known as Abd el-Krim (1882/1883, Ajdir, Morocco – 6 February 1963, Cairo, Egypt) ...

. Raisuni's army was key to the Spanish capture of Larache

Larache ( ar, العرايش, al-'Araysh) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast, where the Loukkos River meets the Atlantic Ocean. Larache is one of the most important cities of the Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region.

Man ...

and Arcila and to contain Abd El-Krim's offensives in 1923 and 1924, but he ended up as a prisoner of Abd El-Krim, who had him executed in 1925.

After stopping in

After stopping in Ceuta

Ceuta (, , ; ar, سَبْتَة, Sabtah) is a Spanish autonomous city on the north coast of Africa.

Bordered by Morocco, it lies along the boundary between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. It is one of several Spanish territorie ...

, Silvestre marched to Meilila in 1920 to take command of the Command

Command may refer to:

Computing

* Command (computing), a statement in a computer language

* COMMAND.COM, the default operating system shell and command-line interpreter for DOS

* Command key, a modifier key on Apple Macintosh computer keyboards

* ...

of the city, from where in January 1921 he led the Riff invasion to stop the local resistance, now led by Abd el-Krim. Berenguer commanded from his headquarters at Tétouan

Tétouan ( ar, تطوان, tiṭwān, ber, ⵜⵉⵟⵟⴰⵡⴰⵏ, tiṭṭawan; es, Tetuán) is a city in northern Morocco. It lies along the Martil Valley and is one of the two major ports of Morocco on the Mediterranean Sea, a few miles so ...

, south of Ceuta, and Silvestre was based at Meilila, 130 miles away, a command arrangement that did not facilitate smooth co-operation between the two generals. In March 1921, Silvestre met Berenguer aboard the old cruiser ''Princesa de Asturias'' to plan the operations in spring. Silvestre disregarded the Moroccans as a serious enemy, said he had all the troops and equipment that he needed, and causally mentioned: "The only way to succeed in Morocco is to cut off the heads of all the Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

". French Marshal Hubert Lyautey

Louis Hubert Gonzalve Lyautey (17 November 1854 – 27 July 1934) was a French Army general and colonial administrator. After serving in Indochina and Madagascar, he became the first French Resident-General in Morocco from 1912 to 1925. Early in ...

, who commanded the forces in French Morocco, complained that the Spanish lacked sufficient cultural sensitivity and often gratuitously offended the Islamic traditions of the Moroccans by openly engaging the services of the ubiquitous prostitutes, who followed the Spanish Army everywhere in Morocco; by engaging in harassment of Muslims on the streets; by dishonest and bigoted treatment of Moroccan tribal chiefs; and by all too often simply assuming that an "iron fist" approach was the best way to deal with the Moroccans. Lyautey criticized the Spanish Army in Morocco in general, but Silvestre exemplified it perfectly with his arrogance that led him to dismiss the Moroccans as hopelessly inferior and his firm belief in the "iron fist".

The operation was risky and dangerous since the Spanish soldiers were poorly trained and often scared of the Riffians. Silvestre's force comprised 20,000 Spanish soldiers, as well as 5,000 ''regulares'', as Moroccans in the Spanish Army were called. Of the Spanish troops, well over half were completely illiterate

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, hum ...

conscripts

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day und ...

from the poorest side of Spanish society and had been sent to Morocco with minimal training. Despite Silvestre's assurances that his equipment was sufficient to defeat the Riffians, about three quarters of the Riffles at the Melilla arsenal were in shoddy condition because of poor maintenance, and a report from late 1920, which Silvestre had never bothered to read, warned that many of the Riffles in Melilla arsenal were unusable or more of a danger to the soldier who was firing them than to the enemy. The average Spanish soldier in Morocco in 1921 was paid the equivalent of US$0.34 per day and lived on a simple diet of coffee, bread, beans, rice and meat offcuts. Many soldiers bartered their Riffles and ammunition at the local markets in exchange for fresh vegetables. The barracks that the soldiers lived in were unsanitary, and medical care at the few hospitals was very poor. Up in the mountains, Spanish soldiers lived in small outposts known as ''blocaos'', which the American historian Stanley Payne observed: "Many of these lacked any sort of toilet, and the soldier who ventured out of the filthy bunker risked exposure to the fire of lurking tribesmen". Continuing a practice first begun in Cuba, corruption flourished in the venal Spanish officer corps; Goods intended for the soldiers were sold to the black market and the funds intended to build road and railroads in Morocco ended up in the pockets of senior officers. A shockingly high number of Spanish officers could not read maps, which explains why Spanish units so frequently got lost in the Riff. In general, studying war was not considered to be a good use of an officer's time, and most officers devoted their time in Melilla in words of the American journalist James Perry to "gambling and whoring, sometimes molesting the native Moorish women". Morale in the army was extremely poor, and most Spanish soldiers just wanted to go home and leave Morocco forever. Because of the prostitutes from Spain, who attached themselves in great number to the Spanish bases in Morocco, venereal diseases

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral s ...

were rampant in the Spanish Army, which once contracted were often utilized as an excuse to evade service. Silvestre was well aware of the poor morale of his soldiers, but he did not regard it as a problem since he believed that his enemy was inferior by far, thus the problems afflicting his troops would be of no importance.

Silvestre had spread out his troops in 144 forts and blockhouses (''blocaos'') from Sidi Dris on the Mediterranean across the Riff to Annual and Tizi Azza and on to Melilla. A typical blockhouse held about a dozen men while the larger forts had about 800 men. Silvestre, again demonstrating his boldness and impetuosity, had pushed his men too deep into the mountains hoping to reach Alhucemas Bay without undertaking the necessary work to built a logistical support network capable of supplying his men out in the ''blocaos'' up in the Riff mountains. Krim had sent Silvestre a letter warning him not to cross the Amekran River, as he would likely die. Silvestre commented to the Spanish press about the letter: "This man Abd el-Krim is crazy. I'm not going to take seriously the threats of a little Berber ''caid'' udgewhom I had at my mercy a short time ago. His insolence merits a new punishment". Krim allowed Silvestre to advance deep into since he knew that the Spanish logistics were, in the words of the Spanish historian Jose Alvarez, "tenuous" at best.

In late May 1921, Silvestre had his first inking of trouble, as he received reports that his supply columns he was sending up into the Riff were regularly being destroyed. As Silvestre had pushed his men very deep into the Riff, and his forts and ''blocaos'' held little in the way of food, the ambushes threatened to bring down the entire chain that Silvestre had built. On 29 May 1921, Silvestre wrote to Berenguer for the first time that the campaign against Krim might be more than a "mere kick in the pants" and that he needed more troops fast. However, in the words of Perry, "this stupid man" marched across the Amekran River to occupy the village Abaran on June 1, 1921. Most of the soldiers were ''regulares'' who promptly

Silvestre had spread out his troops in 144 forts and blockhouses (''blocaos'') from Sidi Dris on the Mediterranean across the Riff to Annual and Tizi Azza and on to Melilla. A typical blockhouse held about a dozen men while the larger forts had about 800 men. Silvestre, again demonstrating his boldness and impetuosity, had pushed his men too deep into the mountains hoping to reach Alhucemas Bay without undertaking the necessary work to built a logistical support network capable of supplying his men out in the ''blocaos'' up in the Riff mountains. Krim had sent Silvestre a letter warning him not to cross the Amekran River, as he would likely die. Silvestre commented to the Spanish press about the letter: "This man Abd el-Krim is crazy. I'm not going to take seriously the threats of a little Berber ''caid'' udgewhom I had at my mercy a short time ago. His insolence merits a new punishment". Krim allowed Silvestre to advance deep into since he knew that the Spanish logistics were, in the words of the Spanish historian Jose Alvarez, "tenuous" at best.

In late May 1921, Silvestre had his first inking of trouble, as he received reports that his supply columns he was sending up into the Riff were regularly being destroyed. As Silvestre had pushed his men very deep into the Riff, and his forts and ''blocaos'' held little in the way of food, the ambushes threatened to bring down the entire chain that Silvestre had built. On 29 May 1921, Silvestre wrote to Berenguer for the first time that the campaign against Krim might be more than a "mere kick in the pants" and that he needed more troops fast. However, in the words of Perry, "this stupid man" marched across the Amekran River to occupy the village Abaran on June 1, 1921. Most of the soldiers were ''regulares'' who promptly mutinied

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among members ...

, murdered their Spanish officers and declared that they were now joining the '' jihad'' that Krim had proclaimed against the Spanish. After the debacle, Berenguer paid an emergency visit to Melilla to meet with Silvestre to "suggest" the latter to suspend his attempts to push over the Amekran River until Berenguer could "pacify" his zone south of Ceuta and start a supporting offensive from the west. Silvestre wanted to hear nothing of Berenguer's "suggestions" and said that unless he received a direct order to stop, he could continue his attempts to push Spanish power beyond the Amekran. Silvestre was so angry with the "suggestions" that he attempted to attack Berenguer and had to be restrained by the other officers. Though Berenguer continued to "suggest" to Silvestre caution in a steady stream of telegrams over the following days and advised no operations beyond the Amekran, he never ordered Silvestre to stop for fear of angering Silvestre's patron, Alfonso XIII, which meant that the stubborn Silvestre continued to press on.

The local resistance began to believe that they were able to defeat the Spanish when on June 1, 1921 it took the position from Abarrán, killing many Spanish soldiers in combat. On June 8, 1921, Silvestre again sent his men south of the Amekran to start building a fort at Igueriben. Krim then out a proclamation to all the Berber tribes of the Riff: "The Spaniards have already lost the game. Look At Abaran! They have left their dead mutilated and unburied, their souls vaguely wandering about, tragically denied the delights of Paradise!" The Riffians now surrounded the new Spanish base at Igueriben and used captured Spanish artillery to bring down fire on the Spanish. Then, Silvestre sent a telegram to Berenguer saying that the situation had become "somewhat delicate" and that he desperately needed more troops. Silvestre now started to worry, as he had much trouble sleeping and eating. However, Silvestre's doubts were quietened when King Alfonso sent him a telegram, whose first line was "Hurrah for real men!", and it urged his favorite general to stay the course and not to retreat. With that, any possibility of retreat vanished, as Silvestre would never displease the king.

The Spanish garrison at Igueriben was cut off but could communicate with the fort at Annual via

The Spanish garrison at Igueriben was cut off but could communicate with the fort at Annual via heliograph

A heliograph () is a semaphore system that signals by flashes of sunlight (generally using Morse code) reflected by a mirror. The flashes are produced by momentarily pivoting the mirror, or by interrupting the beam with a shutter. The heliograp ...

. From the heliograph, Silvestre learned that the men at Igueriben had no water and been reduced to drinking the juice from tomato cans, then vinegar and ink, and finally their own urine. With the dehydrated men of Igueriben in desperate condition, a relief force from Annual was sent down on July 19 but was ambushed and destroyed, with 152 Spanish killed. On July 21, Silvestre sent down another relief force of 3000 men, which was likewise ambushed and defeated.

Battle of Annual

After the fall of Igueriben on July 22, the rebels attacked the Spanishmilitary camp

A military camp or bivouac is a semi-permanent military base, for the lodging of an army. Camps are erected when a military force travels away from a major installation or fort during training or operations, and often have the form of large cam ...

. Silvestre, acting more and more erratically since the previous setbacks, ordered Major Julio Benitez to break out, which led to Benitez and most of his men being hacked to death by the Moroccan tribesmen, who rarely gave the Spanish much mercy. Only 11 survivors of Igueriben managed to reach the encampment at Annual, and 9 of them died within hours due to heat exhaustion. Having just arrived with his staff from Melilla on the 21st Silvestre "gnawed his mostache and swore mightily" upon learning of the final heliograph from the outpost. Matters were decided for Silvestre as Krim decided to follow up his victory at Igueriben by besieging the Annual camp, and a few hours later, his tribesmen had surrounded Annual. At that point, Silvestre, who having previously underestimated Krim now swung to the other extreme and called a council of his senior officers to announce he was ordering a general retreat back to the coast. Silvestre sent his last telegraphed message at about 4:55 a.m. in which he declared that he would start a retreat to Ben Tieb later that morning. Although facing an extreme shortage of ammunition Silvestre had little choice but to order a withdrawal, he inexcusably failed to organize an orderly retreat. Not least because of his ''machismo

Machismo (; ; ; ) is the sense of being " manly" and self-reliant, a concept associated with "a strong sense of masculine pride: an exaggerated masculinity". Machismo is a term originating in the early 1930s and 1940s best defined as hav ...

'', as he was possibly unwilling to admit to his men that they would be about to retreat.

At about 10 am on 22 July 1921, the 5,000 men of the Annual started to march out of the fort without being adequately prepared during the few preceeding hours. As the Spanish marched in a disorganized fashion with limited numbers of officers present to give them direction the Spanish army would suffer a devastating incoherence. As British historian Admiral Cecil Usborne describes: "Units broke up and became incoherent", as men started to head off in every direction amid "the terrible heat and dust of the Moroccan summer". With the Spanish receiving no orders, the Moroccans easily cut them down with writhing fire, which caused the Spanish army to descend into anarchy, with every man trying to save himself. The Riff tribesmen soon attacked the fleeing Spanish with swords, and others were "shot down like rabbits". According to some, the "smiling tribesmen" stood up from shelter to shoot down the Spanish "as if it was all a game to them". The Riffians almost used up all of their ammunition, but recompensated the loss with captured Spanish guns and ammunition. As a result the tribesmen had more ammunition at the end of the battle than they initially had at the beginning. Soon, the Riffians had entered the perimeter of the Spanish camp at Annual, killing every Spaniard they encountered. The Riffians had no mercy and cut down not only the Spanish soldiers but also the Spanish prostitutes, which had followed the troops up into the Riff. While that was happening, Silvestre reportedly stood on the parapet of the Annual encampment, watching his army being destroyed. With the exception of one cavalry unit, the Cazadores de Alcántara, the entire garrison of about 5,000 men were lost. Silvestre allegedly further demoralized his men by yelling at them, "Run, run, the bogeyman

The Bogeyman (; also spelled boogeyman, bogyman, bogieman, boogie monster, boogieman, or boogie woogie) is a type of mythic creature used by adults to frighten children into good behavior. Bogeymen have no specific appearance and conceptions var ...

is coming!" as they attempted to rally following their initial defeat. Silvestre's comments about the "bogeyman" was his only recorded contribution to the command of his army during the Annual rout. Of the 570 Spaniards who survived the " Disaster of Annual", the 326 who were taken prisoner were released in January 1923 after the Spanish state paid a ransom of four million '' pesetas''. The survivors consisted of 44 officers, 236 soldiers, 10 civilians and 33 prostitutes and their children.

Death

According to some witnesses, Silvestre, upon witnessing the disaster, went into his tent and committed suicide, shooting himself in the head. Whether dead by his own hand or, like most of his staff, killed in the turmoil of the retreat, the only remnant of Silvestre appears to have been his scarlet and gold general'ssash

A sash is a large and usually colorful ribbon or band of material worn around the body, either draping from one shoulder to the opposing hip and back up, or else running around the waist. The sash around the waist may be worn in daily attire, bu ...

. Captain Fortea, one of the few Spanish prisoners taken at Annual, reported that Abd el-Krim wore the sash during the pursuit. Abd el-Krim himself told the writer J. Roger-Mathieu that this and other insignia had been brought to him by one of his men. In addition to this, a Moroccan courier from Kaddur Nadar claimed 8 days after the battle to have seen Silvestre's dead body lying on the battlefield face down, still recognizable by his sash and epaulettes

Epaulette (; also spelled epaulet) is a type of ornamental shoulder piece or decoration used as insignia of rank by armed forces and other organizations. Flexible metal epaulettes (usually made from brass) are referred to as ''shoulder scales'' ...

.

A total of 15,000 Spanish soldiers fell in the days from July 22 to August 9; most died during the Battle of Annual

The Battle of Annual was fought on 22 July 1921 at Annual, in northeastern Morocco, between the Spanish Army and Rifian Berbers during the Rif War. The Spanish suffered a major military defeat, which is almost always referred to by the Spanish ...

(known as the ''Disaster of Annual'' to Spanish historians). Krim followed up his victory at Annual by laying siege to all of the ''blocaos'' in the Riff mountains, none of which had much food or water stored, and all of which he took. After the Annual rout, Spanish morale collapsed and there was very few attempts at organized resistance, with the commanders of every ''blocao'' making no effort for any organized retreat. On that final day, Silvestre's deputy, General Felipe Navarro y Ceballos-Escalera, surrendered with his men at the sprawling fort of Mount Arruit.

References

Next publication of Abd el-Krim's biography in base of official Spanish documents

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Silvestre, Manuel Fernandez Spanish generals Spanish military personnel killed in action People of the Rif War 1871 births 1921 suicides Military personnel missing in action