Manchester New College on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Harris Manchester College is one of the

The college started as the

The college started as the

Graduate Studies Prospectus - Last updated 17 Sep 08 Originally run by

In its early days, the college supported reforming causes, such as the

In its early days, the college supported reforming causes, such as the

Manchester College became a

Manchester College became a

Despite being one of the smallest colleges of

Despite being one of the smallest colleges of

File:Harris Manchester College, Oxford – Siew-Sngiem Clock Tower and Sukum Navapan Gate.jpg, Siew-Sngiem Clock Tower and Sukum Navapan Gate

File:Harris Manchester College library.jpg, Tate Library

File:Harris Manchester College Chapel Interior 2, Oxford, UK - Diliff.jpg, Stained-glass windows of chapel

File:Harris-53.jpg, College grounds

File:Arlosh Hall interior.jpg, Dining hall

File:Harris-47.jpg, Exterior of chapel

File:Priestley.jpg,

Virtual tour

{{Authority control 1786 establishments in England Colleges of the University of Oxford Educational institutions established in 1786 Buildings and structures of the University of Oxford

constituent colleges

A collegiate university is a university in which functions are divided between a central administration and a number of constituent colleges. Historically, the first collegiate university was the University of Paris and its first college was the C ...

of the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

in the United Kingdom. It was founded in Warrington

Warrington () is a town and unparished area in the borough of the same name in the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England, on the banks of the River Mersey. It is east of Liverpool, and west of Manchester. The population in 2019 was estimat ...

in 1757 as a college for Unitarian students and moved to Oxford in 1893. It became a full college of the university in 1996, taking its current name to commemorate its predecessor the Manchester Academy and a benefaction by Lord Harris of Peckham

Philip Charles Harris, Baron Harris of Peckham (born 15 September 1942), is an English businessman and politician. A prominent Conservative Party donor, Harris is a member of the House of Lords.

He is the sponsor of a large multi-academy trus ...

.

The college's postgraduate and undergraduate places are exclusively for students aged 21 years or over. With around 100 undergraduates

Undergraduate education is education conducted after secondary education and before postgraduate education. It typically includes all postsecondary programs up to the level of a bachelor's degree. For example, in the United States, an entry-le ...

and 150 postgraduates

Postgraduate or graduate education refers to academic or professional degrees, certificates, diplomas, or other qualifications pursued by post-secondary students who have earned an undergraduate (bachelor's) degree.

The organization and struc ...

, Harris Manchester is the smallest undergraduate college in either of the Oxbridge universities.

History

Foundation and relocation

The college started as the

The college started as the Warrington Academy

Warrington Academy, active as a teaching establishment from 1756 to 1782, was a prominent dissenting academy, that is, a school or college set up by those who dissented from the established Church of England. It was located in Warrington (then ...

in 1757 where its teachers included Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

, before being refounded as the Manchester Academy in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

in 1786.University of OxfordGraduate Studies Prospectus - Last updated 17 Sep 08 Originally run by

English Presbyterians

Presbyterianism in England is practised by followers of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism who practise the Presbyterian form of church government. Dating in England as a movement from 1588, it is distinct from Continental and Scottish ...

, it was one of several dissenting academies

The dissenting academies were schools, colleges and seminaries (often institutions with aspects of all three) run by English Dissenters, that is, those who did not conform to the Church of England. They formed a significant part of England's edu ...

that provided religious nonconformists with higher education

Higher education is tertiary education leading to award of an academic degree. Higher education, also called post-secondary education, third-level or tertiary education, is an optional final stage of formal learning that occurs after comple ...

, as at the time the only universities in England – Oxford and Cambridge – were restricted to Anglicans

Anglicanism is a Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia ...

. It taught radical theology as well as modern subjects, such as science, modern languages, language, and history; as well as the classics. Its most famous professor was John Dalton, developer of atomic theory

Atomic theory is the scientific theory that matter is composed of particles called atoms. Atomic theory traces its origins to an ancient philosophical tradition known as atomism. According to this idea, if one were to take a lump of matter ...

.

The college changed its location five times before settling in Oxford. It was located in Manchester between 1786 and 1803. It moved to York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

until 1840. It was located at 38 Monkgate, just outside Monkbar; later this was the first building of the College of Ripon and York St John

A college ( Latin: ''collegium'') is an educational institution or a constituent part of one. A college may be a degree-awarding tertiary educational institution, a part of a collegiate or federal university, an institution offerin ...

(now York St John University). The key person in York was Charles Wellbeloved

Charles Wellbeloved (6 April 1769 – 29 August 1858) was an English Unitarian divine and archaeologist.

Biography

Charles Wellbeloved, only child of John Wellbeloved (1742–1787), by his wife Elizabeth Plaw, was born in Denmark Street, St ...

, a Unitarian minister, after whom a function room in the college is named. Because he would not move to Manchester, the college moved to York to have him as head. At first he taught all subjects, but hired additional tutors after a year. He always worked hard and several times his health broke. Wellbeloved did not allow the school to be called Unitarian because he wanted students to have an open mind and to discover the truth for themselves. In 1809 he wrote to George Wood,

Under Wellbeloved's principalship 235 students were educated at the college: 121 divinity

Divinity or the divine are things that are either related to, devoted to, or proceeding from a deity.divine< ...

students and 114 laymen. Of the former, 30 did not enter the ministry and five entered the Anglican priesthood. Among the lay students were scholars, public servants, businessmen, and notable men in the arts. The majority was Unitarian.

In 1840, when age forced him to retire, the college moved back to Manchester, where it stayed until 1853. In 1840, the college started an association with the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

, and gained the right to present students for degrees from London. Between 1853 and 1889 the college was located in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, in University Hall, Gordon Square. From London it moved to Oxford, opening its new buildings in 1893. In Oxford, the Unitarian Manchester College was viewed with alarm by orthodox Anglicans. William Sanday was warned that his presence at the official opening of 'an institution which professedly allows such fundamental Christian truths as the Holy Trinity and the Incarnation to be treated as open questions' would 'tend to the severance of the friendly relation subsisting between the University and the Church'.

Social reform

In its early days, the college supported reforming causes, such as the

In its early days, the college supported reforming causes, such as the abolition of slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

(1778), and the repeal of the Test Act (1828) and the Corporation Act

The Corporation Act of 1661 was an Act of the Parliament of England (13 Cha. II. St. 2 c. 1). It belonged to the general category of test acts, designed for the express purpose of restricting public offices in England to members of the Church ...

(1828). In 1922 the principal, L.P. Jacks, hosted Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner (27 or 25 February 1861 – 30 March 1925) was an Austrian occultist, social reformer, architect, esotericist, and claimed clairvoyant. Steiner gained initial recognition at the end of the nineteenth century as ...

to present a conference on alternative education and the model Waldorf school

Waldorf education, also known as Steiner education, is based on the educational philosophy of Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy. Its educational style is holistic, intended to develop pupils' intellectual, artistic, and practical ...

at Stuttgart, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

which led to the establishment of such schools in Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the college provided courses for the Workers' Educational Association

The Workers' Educational Association (WEA), founded in 1903, is the UK's largest voluntary sector provider of adult education and one of Britain's biggest charities. The WEA is a democratic and voluntary adult education movement. It delivers lea ...

.

Women were permitted to attend some lectures in college from 1876, and in 1877, the college set up a series of examinations in theology, which could be taken by women as well as men. In 1901, Gertrude von Petzold graduated from her training at Manchester College to become a minister in the Unitarian church- the first woman to be qualified as a minister in England. This was possible despite the fact that Oxford University did not formally accept female students or award them degrees until 1920 because Manchester College was at that time associated with the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

, which in 1878 became the first UK university to award degrees to women.

World War II

Manchester College played a significant part in the planning of theD-Day landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

on 6 June 1944. The Ministry of Works and Buildings requisitioned most of the college's buildings on 17 October 1941 to facilitate the Naval Intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from a ...

and the Inter-Services Topographic Department (ISTD). ISTD operations focussed on gathering of topographical intelligence for the day when the Allies would return to continental Europe.

Departments were divided between Oxford and Cambridge, but it was the ISTD section in Manchester College which planned Operation Overlord, known as the D-Day landings. The college's Arlosh Hall served as the main centre of operations, with Nissen hut

A Nissen hut is a prefabricated steel structure for military use, especially as barracks, made from a half-cylindrical skin of Corrugated galvanised iron, corrugated iron. Designed during the First World War by the American-born, Canadian-British ...

s and tents put up in the quads. Among various other sources, the nearby School of Geography of the university supplied the ISTD with many maps and charts which proved an essential part in the success of the invasion.

Modern day

Manchester College became a

Manchester College became a permanent private hall

A permanent private hall (PPH) in the University of Oxford is an educational institution within the university. There are five permanent private halls at Oxford, four of which admit undergraduates. They were founded by different Christian denomina ...

of Oxford University in 1990 and subsequently a full constituent college

A collegiate university is a university in which functions are divided between a central administration and a number of constituent colleges. Historically, the first collegiate university was the University of Paris and its first college was the C ...

, being granted a royal charter in 1996. At the same time, it changed its name to Harris Manchester College in recognition of a benefaction by Philip Harris, Baron Harris of Peckham

Philip Charles Harris, Baron Harris of Peckham (born 15 September 1942), is an English businessman and politician. A prominent Conservative Party donor, Harris is a member of the House of Lords.

He is the sponsor of a large multi-academy tru ...

. Formerly known as Manchester College, it is listed in the University Statutes (V.1) as Manchester Academy and Harris College, and at university ceremonies it is called ''Collegium de Harris et Manchester''.

Today the college only accepts students over the age of 21, both for undergraduate and graduate studies. The college tries to continue its liberal and pioneering ethos, considering its mature student focus as a modern means of providing higher education to those that have been excluded from it in the past.

The college houses several research centres, including the Commercial Law Centre, directed by Prof Kristin van Zwieten, Clifford Chance Associate Professor of Law and Finance, which engages in research in all aspects of national, international, transnational and comparative law relating to commerce and finance; and the Wellbeing Research Centre, directed by Prof Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, which applies interdisciplinary research and teaching on well-being at Oxford.

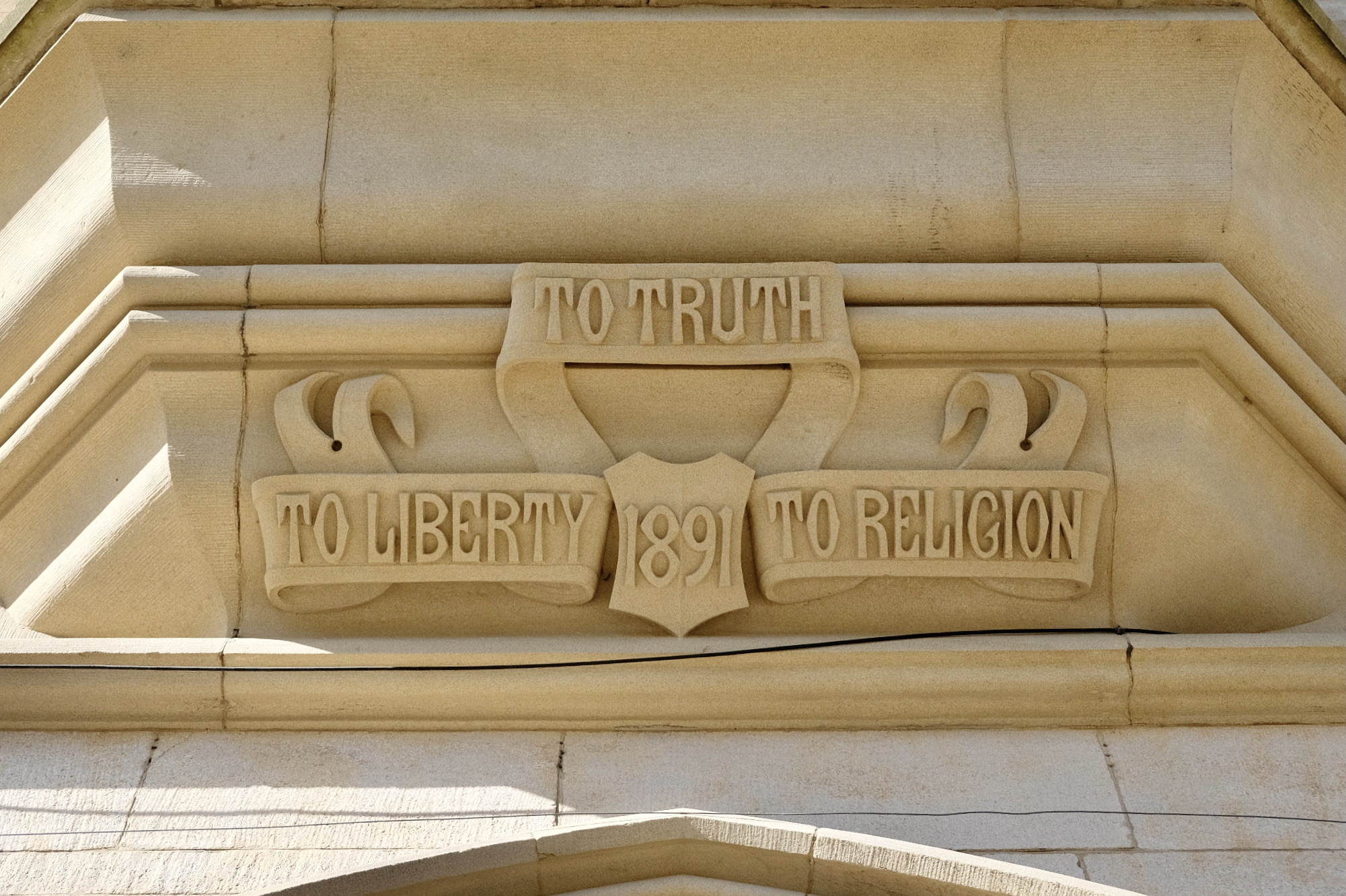

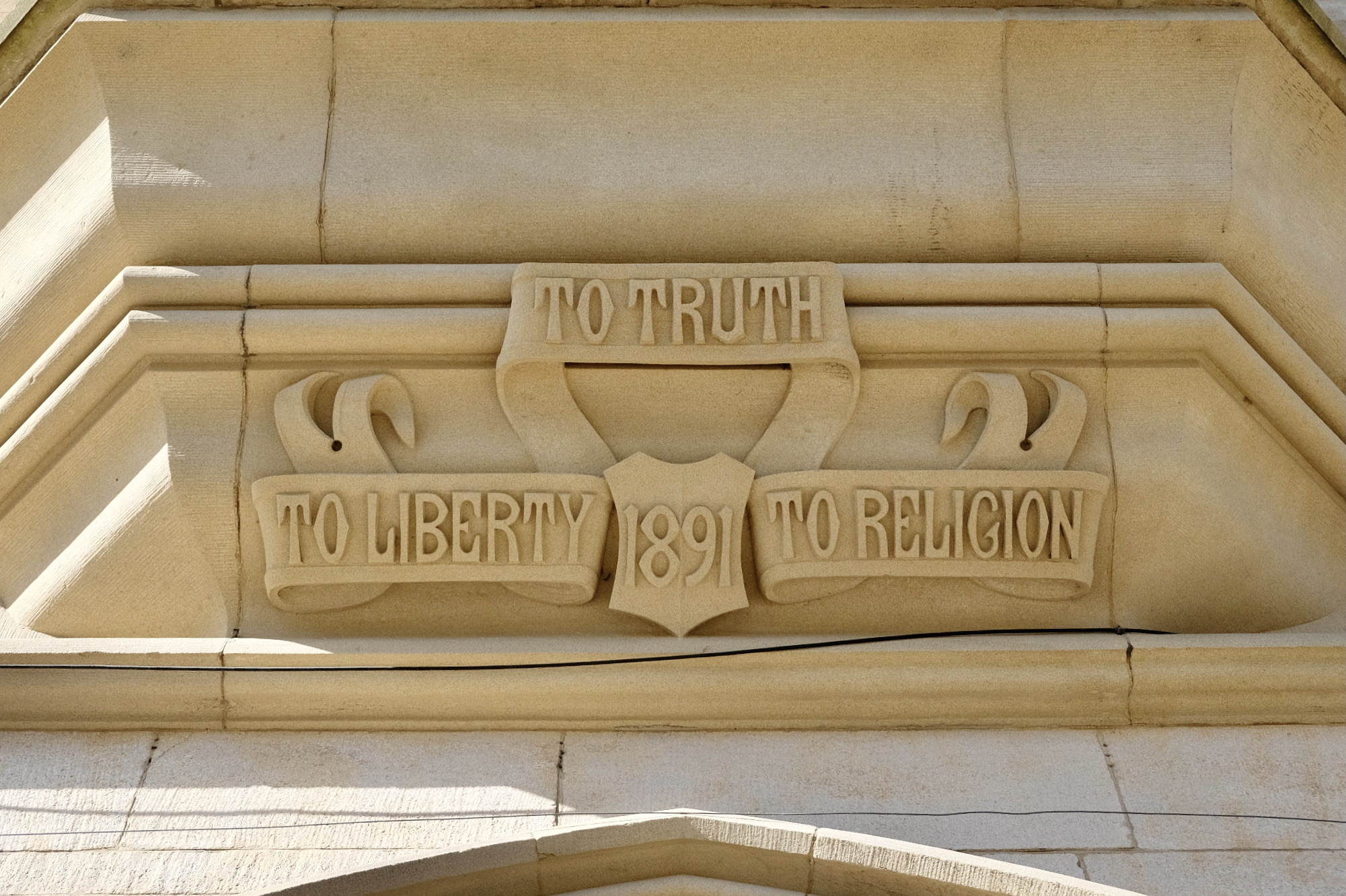

Buildings

The main quad was designed by architectThomas Worthington Thomas or Tom Worthington may refer to:

*Thomas Worthington (Douai) (1549–1627), English Catholic priest and third President of Douai College

* Thomas Worthington (Dominican) (1671–1754), English Dominican friar and writer

* Thomas Worthington ...

, and built between 1889 and 1893. It houses the Tate Library and the chapel. The Arlosh hall, designed by Percy Worthington

Sir Percy Scott Worthington (31 January 1864 – 15 July 1939) was an English architect.

He was born in Crumpsall, Manchester, the eldest son of the architect Thomas Worthington. He was educated at Clifton College, Bristol, and Corpus Christi Co ...

, was added in 1913. The college also has several newer buildings to the West of the main quad. In 2013–2014 the Siew-Sngiem Clock Tower & Sukum Navapan Gate were added to the Arlosh quad. The inscription on the tower "It is later than you think, but it is never too late", refers to the role of the college in educating mature students.

In 2018 a new building named Maevadi Hall was completed after two years of construction. It is situated to the west of the Arlosh Hall and contains a conference room, student accommodation and a student social area.

Chapel

The chapel designed by "Worthington and Elgood" was inaugurated in 1893. The chapel is notable for its stained-glass windows by the Pre-Raphaelite artists SirEdward Burne-Jones

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, 1st Baronet, (; 28 August, 183317 June, 1898) was a British painter and designer associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood which included Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Millais, Ford Madox Brown and Holman ...

and William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

, as well as its ornate wood carvings and organ, which was painted by Morris and Co

Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. (1861–1875) was a furnishings and decorative arts manufacturer and retailer founded by the artist and designer William Morris with friends from the Pre-Raphaelites. With its successor Morris & Co. (1875–194 ...

. Seating in the chapel consisted of individual chairs until pews were added in 1897. The oak screen was added in 1896 and the original windows were made of plain glass until the installation of stained glass windows in 1895 and 1899.

Particularly noteworthy are the stained glass windows on the north wall of the chapel, which were installed in 1896 and depict the Six Days of Creation

The Genesis creation narrative is the creation myth of both Judaism and Christianity. The narrative is made up of two stories, roughly equivalent to the first two chapters of the Book of Genesis. In the first, Elohim (the Hebrew generic word ...

. These were donated by James and Isabella Arlosh in memory of their son Godfrey. The Unitarian-affiliated Manchester College Oxford Chapel Society meets in the college chapel on Sundays. The society is affiliated to the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches

The General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches (GAUFCC or colloquially British Unitarians) is the umbrella organisation for Unitarian, Free Christians, and other liberal religious congregations in the United Kingdom and Irelan ...

.

The Tate Library

Despite being one of the smallest colleges of

Despite being one of the smallest colleges of Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

, Harris Manchester boasts the sixth largest college library and offers the best student population to book ratio. It houses a collection of books and manuscripts dating back to the fifteenth century and is famous for its antiquarian books, tract collection, and library of Protestant Dissent. The Tate Library was built by Sir Henry Tate, the benefactor behind London's Tate Gallery. The library was expanded in 2011 with the addition of a gallery, designed to blend in with the Victorian Gothic architecture. The library is well stocked in all the major subjects offered by the college including English Literature, Philosophy, Theology, Politics, Economics, Law, History and Medicine. It also holds a significant collection on the history of Protestant dissent in England and is home to the Carpenter Library of World Religions, donated to the college by its former principal, J. Estlin Carpenter.

Harris Manchester College is located 200 metres from the Bodleian Library, the main research library of Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

, as well as the English, History, Social Sciences, and Law faculty libraries.

Student life

Despite the small student body, the college offers a wide array of courses. Many undergraduate tutorials are carried out in the college, though for some specialist papers undergraduates may be sent to tutors in other colleges. Members are generally expected to dine in the Arlosh Hall, where there is a twice-weekly formal dinner on Mondays and Wednesdays at which students dress in jackets, ties, and gowns.Sports

Although the college does not have its own sports ground, it consistently enters women's and men's teams into the university leagues, and members routinely join teams from other colleges. The college has a punt, The Royle Yacht, and a croquet lawn. In recent years the college'sice hockey

Ice hockey (or simply hockey) is a team sport played on ice skates, usually on an ice skating rink with lines and markings specific to the sport. It belongs to a family of sports called hockey. In ice hockey, two opposing teams use ice h ...

team has been successful, once winning second place in the intercollegiate cuppers

Cuppers are intercollegiate sporting competitions at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. The term comes from the word "cup" and is an example of the Oxford "-er". Each sport holds only one Cuppers competition each year, which is open to all ...

tournament, with the Basketball team winning third place in its intercollegiate cuppers

Cuppers are intercollegiate sporting competitions at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. The term comes from the word "cup" and is an example of the Oxford "-er". Each sport holds only one Cuppers competition each year, which is open to all ...

tournament the year before. There is also an active pool team and a thriving squash club.

Harris Manchester also has an affiliation with neighbouring Wadham College

Wadham College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It is located in the centre of Oxford, at the intersection of Broad Street and Parks Road.

Wadham College was founded in 1610 by Dorothy W ...

for those interested in becoming members of Wadham College Boat Club

Wadham College Boat Club (WCBC) is the rowing club of Wadham College, Oxford, in Oxford, United Kingdom. The club's members are students and staff from Wadham College and Harris Manchester College. Founded some time before 1837, Wadham has had ...

, which came in second in the 2012 Women's Torpids

Torpids is one of two series of bumping races, a type of rowing race, held yearly at Oxford University; the other is Eights Week. Over 130 men's and women's crews race for their colleges in six men's divisions and five women's; almost 1,200 pa ...

and Summer VIIIs, and saw both the First and Second Men's boats winning blades.

Junior Common Room (JCR) Bar

Harris Manchester has one of the three remaining student run college bars in Oxford (the others beingBalliol College

Balliol College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. One of Oxford's oldest colleges, it was founded around 1263 by John I de Balliol, a landowner from Barnard Castle in County Durham, who provided the ...

and St Cross College). The common room is decorated with William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

wallpaper.

Gallery

Notable people

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

, (Warrington Academy) Credited with discovery of oxygen

File:Thomas Robert Malthus Wellcome L0069037 (Portrait).jpg, Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English cleric, scholar and influential economist in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

, (Warrington Academy), British political economist

File:James Martineau by Elliott & Fry, c1860s-crop.jpg, James Martineau

James Martineau (; 21 April 1805 – 11 January 1900) was a British religious philosopher influential in the history of Unitarianism.

For 45 years he was Professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy and Political Economy in Manchester New College ( ...

(Manchester College, York), English religious philosopher

File:Ren. Gertrud von Petzold LCCN2014685377 (cropped).jpg, Gertrude von Petzold (Manchester College), First woman church minister in England

File:Tope folarin 4011886.JPG, Tope Folarin (Harris Manchester College), Nigerian-American writer

File:INGRID BETANCOURT IN PISA.jpg, Íngrid Betancourt

Íngrid Betancourt Pulecio (; born 25 December 1961) is a Colombian politician, former senator and anti-corruption activist, especially opposing political corruption.

Betancourt was kidnapped by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) ...

(Harris Manchester College), Colombian senator and anti-corruption activist

Principals

Since 2018 the principal of the college has been the historian, Professor Jane Shaw.People associated with Harris Manchester

Fellows of the College

Alumni

See also

* List of dissenting academies (19th century) *Warrington Academy

Warrington Academy, active as a teaching establishment from 1756 to 1782, was a prominent dissenting academy, that is, a school or college set up by those who dissented from the established Church of England. It was located in Warrington (then ...

* College of the University of Oxford

References

Further reading

* ''A Fine Victorian Gentleman: The Life and Times of Charles Wellbeloved'' by Frank Schulman, published by Harris Manchester College 1999. Pages 55–89 cover Wellbeloved's period as principal of Manchester College, York.External links

*Virtual tour

{{Authority control 1786 establishments in England Colleges of the University of Oxford Educational institutions established in 1786 Buildings and structures of the University of Oxford