Malevich on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Kazimir Severinovich Malevich ; german: Kasimir Malewitsch; pl, Kazimierz Malewicz; russian: Казими́р Севери́нович Мале́вич ; uk, Казимир Северинович Малевич, translit=Kazymyr Severynovych Malevych ., group=nb (Запись о рождении в метрической книге римско-католического костёла св. Александра в Киеве, 1879 год

// ЦГИАК Украины, ф. 1268, оп. 1, д. 26, л. 13об—14. – 15 May 1935) was an artist and art theorist of the Russian avant-garde, whose pioneering work and writing had a profound influence on the development of abstract art in the 20th century.Milner and Malevich 1996, p. X; Néret 2003, p. 7; Shatskikh and Schwartz, p. 84. Born in Kiev to an ethnic

"The Square,"

''New Yorker'', 12 June 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2018. ''Suprematist Composition:

"Malevich in his Milieu,"

''Hyperallergic'', 24 July 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2018. In its immediate aftermath, vanguard movements such as Suprematism and

"Five unknown facts about Malevich"

''Opinion'', 23 February 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2020. But the start of repression in Ukraine against the intelligentsia forced Malevich return to modern-day

"Rare Glimpse of the Elusive Kazimir Malevich"

''

"The man they couldn't hang"

''The Guardian'', 10 May 2000. Retrieved 21 March 2018. In 1930, he was imprisoned for two months due to suspicions raised by his trip to Poland and Germany. Forced to abandon abstraction, he painted in a representational style in the years before his death from cancer in 1935, at the age of 56. Nonetheless, his art and his writing influenced contemporaries such as

Walczą o polskość Malewicza (Advocating the Polishness of Malewicz)

''Nowy Dziennik''. who settled near Kiev in

"The Ukrainian Museum will be displaying new materials highlighting artistic modernism in Ukraine: Kazimir Malevich.Kyiv Period"

11 February 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2020. and the House of the Arts in Leningrad (1930). He wrote the book ''The World as Non-Objectivity'', which was published in

In 1927, Malevich traveled to

In 1927, Malevich traveled to

Malevich’s Burial Site Is Found, Underneath Housing Development

''

Malevich's family was one of the millions of Poles who lived within the Russian Empire following the Partitions of Poland. Kazimir Malevich was born near Kiev on lands that had previously been part of the

Malevich's family was one of the millions of Poles who lived within the Russian Empire following the Partitions of Poland. Kazimir Malevich was born near Kiev on lands that had previously been part of the

Alfred H. Barr Jr. included several paintings in the groundbreaking exhibition "Cubism and Abstract Art" at the

Alfred H. Barr Jr. included several paintings in the groundbreaking exhibition "Cubism and Abstract Art" at the

''Black Square'', the fourth version of his

''Black Square'', the fourth version of his

†† Also known as ''Black Square and Red Square: Painterly Realism of a Boy with a Knapsack - Color Masses in the Fourth Dimension''.

File:Flowergirl.jpg, ''Flower Girl'', 1903

File:Bathers.jpg, ''Bathers'', 1908

File:Winter Landscape (Malevich, 1930).jpg, ''Winter'', 1909

File:Taking in the Rye Kazimir Malevich 1911.jpeg, ''Taking in the Rye'', 1911

File:Self-Portrait (1908 or 1910-1911).jpg, ''Self-portrait'', 1912

File:Head of a Peasant Girl.jpg, ''Head of a Peasant Girl'', 1912-1913

File:Bureau and Room, by Kazimir Malevich.jpg, ''Bureau and Room'', 1913

File:Cow and Fiddle, by Kazimir Malevich.jpg, ''Cow and Fiddle'', 1913

File:Englishman in Moscow.jpg, ''Englishman in Moscow'', 1914

File:Kazimir Malevich, 1914, Composition with the Mona Lisa, oil, collage and graphite on canvas, 62.5 × 49.3 cm, Russian Museum.jpg, ''Composition with the Mona Lisa'', 1914

File:Black circle.jpg, ''

Mylivepage.ru

' * Tedman, Gary. Soviet Avant Garde Aesthetics, chapter from Aesthetics & Alienation. pp 203–229. 2012. Zero Books. * Tolstaya, Tatyana

''The Square''

''The New Yorker'', 12 June 2015 * Das weiße Rechteck. Schriften zum Film, herausgegeben von Oksana Bulgakowa. PotemkinPress, Berlin 1997, * ''The White Rectangle. Writings on Film.'' (In English and the Russian original manuscript). Edited by Oksana Bulgakowa. PotemkinPress, Berlin / Francisco 2000,

Malevich works, MoMA

Kazimir Malevich, Guggenheim Collection Online

Floirat, Anetta. 2016, The Scythian element of the Russian primitivism, in music and visual arts

Based on the work Goncharova, Malevich, Roerich, Stravinsky and Prokofiev

Peter Brooke, ''Deux Peintres Philosophes - Albert Gleizes et Kasimir Malévitch and Quelques Réflexions sur la Littérature Actuelle du Cubisme''

both Ampuis (Association des Amis d’Albert Gleizes) 1995

History of Malevich-designed Perfume bottle of the eau de cologne “''Severny''”

{{DEFAULTSORT:Malevich, Kazimir 1879 births 1935 deaths Abstract painters Artists from Kyiv Ukrainian people of Polish descent 19th-century painters from the Russian Empire 20th-century Russian painters Futurist painters People from the Russian Empire of Polish descent Painters from the Russian Empire Russian male painters Modern painters Polish painters Polish male painters Russian avant-garde Soviet painters Suprematism (art movement) Ukrainian avant-garde Ukrainian painters Ukrainian male painters Ukrainian sculptors Ukrainian male sculptors Deaths from prostate cancer Deaths from cancer in the Soviet Union 19th-century male artists from the Russian Empire 20th-century Russian male artists Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture alumni

// ЦГИАК Украины, ф. 1268, оп. 1, д. 26, л. 13об—14. – 15 May 1935) was an artist and art theorist of the Russian avant-garde, whose pioneering work and writing had a profound influence on the development of abstract art in the 20th century.Milner and Malevich 1996, p. X; Néret 2003, p. 7; Shatskikh and Schwartz, p. 84. Born in Kiev to an ethnic

Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

family, his concept of Suprematism

Suprematism (russian: Супремати́зм) is an early twentieth-century art movement focused on the fundamentals of geometry (circles, squares, rectangles), painted in a limited range of colors. The term ''suprematism'' refers to an abstra ...

sought to develop a form of expression that moved as far as possible from the world of natural forms (objectivity) and subject matter in order to access "the supremacy of pure feeling"Malevich, Kazimir. ''The Non-Objective World'', Chicago: Theobald, 1959. and spirituality. Malevich is also considered to be part of the Ukrainian avant-garde

Ukrainian avant-garde is a term widely used to refer the most innovative metamorphosises in Ukrainian art from the end of 1890s to the middle of the 1930s along with associated artists. Broadly speaking, it is Ukrainian art synchronized with the i ...

(together with Alexander Archipenko

Alexander Porfyrovych Archipenko (also referred to as Olexandr, Oleksandr, or Aleksandr; uk, Олександр Порфирович Архипенко, Romanized: Olexandr Porfyrovych Arkhypenko; February 25, 1964) was a Ukrainian and American ...

, Sonia Delaunay

Sonia Delaunay (13 November 1885 – 5 December 1979) was a French artist, who spent most of her working life in Paris. She was born in Odessa (then part of Russian Empire), and formally trained in Russian Empire and Germany before moving to Fr ...

, Aleksandra Ekster

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "pr ...

, and David Burliuk

David Davidovich Burliuk (Давид Давидович Бурлюк; 21 July 1882 – 15 January 1967) was a Russian-language poet, artist and publicist associated with the Futurist and Neo-Primitivist movements. Burliuk has been described as ...

) that was shaped by Ukrainian-born artists who worked first in Ukraine and later over a geographical span between Europe and America.

Early on, Malevich worked in a variety of styles, quickly assimilating the movements of Impressionism

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage ...

, Symbolism

Symbolism or symbolist may refer to:

Arts

* Symbolism (arts), a 19th-century movement rejecting Realism

** Symbolist movement in Romania, symbolist literature and visual arts in Romania during the late 19th and early 20th centuries

** Russian sym ...

and Fauvism, and after visiting Paris in 1912, Cubism. Gradually simplifying his style, he developed an approach with key works consisting of pure geometric forms and their relationships to one another, set against minimal grounds. His ''Black Square

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have ...

'' (1915), a black square on white, represented the most radically abstract painting known to have been created so farChipp, Herschel B. ''Theories of Modern Art'', Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1968, p. 311-2. and drew "an uncrossable line (…) between old art and new art";Tolstaya, Tatiana"The Square,"

''New Yorker'', 12 June 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2018. ''Suprematist Composition:

White on White

''Suprematist Composition: White on White'' (1918) is an abstract oil-on-canvas painting by Kazimir Malevich. It is one of the more well-known examples of the Russian Suprematism movement, painted the year after the October Revolution.

Part ...

'' (1918), a barely differentiated off-white square superimposed on an off-white ground, would take his ideal of pure abstraction to its logical conclusion.de la Croix, Horst and Richard G. Tansey, Gardner's Art Through the Ages, 7th Ed., New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980, p. 826-7. In addition to his paintings, Malevich laid down his theories in writing, such as "From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism" (1915) and ''The Non-Objective World: The Manifesto of Suprematism'' (1926).

Malevich's trajectory in many ways mirrored the tumult of the decades surrounding the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

(O.S.) in 1917.Bezverkhny, Eva"Malevich in his Milieu,"

''Hyperallergic'', 24 July 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2018. In its immediate aftermath, vanguard movements such as Suprematism and

Vladimir Tatlin

Vladimir Yevgrafovich Tatlin ( – 31 May 1953) was a Russian and USSR, Soviet painter, architect and stage-designer. Tatlin achieved fame as the architect who designed The Monument to the Third International, more commonly known as Tatlin's Towe ...

's Constructivism

Constructivism may refer to:

Art and architecture

* Constructivism (art), an early 20th-century artistic movement that extols art as a practice for social purposes

* Constructivist architecture, an architectural movement in Russia in the 1920s a ...

were encouraged by Trotskyite

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a ...

factions in the government. Malevich held several prominent teaching positions and received a solo show at the Sixteenth State Exhibition in Moscow in 1919. His recognition spread to the West with solo exhibitions in Warsaw and Berlin in 1927. From 1928 to 1930, he taught at the Kiev Art Institute, with Alexander Bogomazov

Alexander Bogomazov or Oleksandr Bohomazov (russian: Александр Константинович Богомазов, uk, Олександр Костянтинович Богомазов; March 26, 1880 – June 3, 1930) was a Ukrainian painte ...

, Victor Palmov

Victor Nikolaevich Palmov ( uk, Віктор Никандрович Пальмов) (10 October 1888 – 7 June 1929) was a Russian and Ukrainian painter and avant-garde artist (Futurism (art), Futurist and Neo-primitivism, Neo-primitivist) from t ...

, Vladimir Tatlin

Vladimir Yevgrafovich Tatlin ( – 31 May 1953) was a Russian and USSR, Soviet painter, architect and stage-designer. Tatlin achieved fame as the architect who designed The Monument to the Third International, more commonly known as Tatlin's Towe ...

and published his articles in a Kharkiv magazine, ''Nova Generatsia'' (''New Generation'').Filevska, Tetiana"Five unknown facts about Malevich"

''Opinion'', 23 February 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2020. But the start of repression in Ukraine against the intelligentsia forced Malevich return to modern-day

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. From the beginning of the 1930s, modern art was falling out of favor with the new government of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

. Malevich soon lost his teaching position, artworks and manuscripts were confiscated, and he was banned from making art.Nina Siegal (5 November 2013)"Rare Glimpse of the Elusive Kazimir Malevich"

''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

''.Wood, Tony"The man they couldn't hang"

''The Guardian'', 10 May 2000. Retrieved 21 March 2018. In 1930, he was imprisoned for two months due to suspicions raised by his trip to Poland and Germany. Forced to abandon abstraction, he painted in a representational style in the years before his death from cancer in 1935, at the age of 56. Nonetheless, his art and his writing influenced contemporaries such as

El Lissitzky

Lazar Markovich Lissitzky (russian: link=no, Ла́зарь Ма́ркович Лиси́цкий, ; – 30 December 1941), better known as El Lissitzky (russian: link=no, Эль Лиси́цкий; yi, על ליסיצקי), was a Russian artist ...

, Lyubov Popova

Lyubov Sergeyevna Popova (russian: Любо́вь Серге́евна Попо́ва; April 24, 1889 – May 25, 1924) was a Russian-Soviet avant-garde artist, painter and designer.

Early life

Popova was born in Ivanovskoe, near Moscow, to t ...

and Alexander Rodchenko

Aleksander Mikhailovich Rodchenko (russian: link=no, Алекса́ндр Миха́йлович Ро́дченко; – 3 December 1956) was a Russian and Soviet artist, sculptor, photographer, and graphic designer. He was one of the founders ...

, as well as generations of later abstract artists, such as Ad Reinhardt

Adolph Dietrich Friedrich Reinhardt (December 24, 1913 – August 30, 1967) was an abstract painter active in New York for more than three decades. He was a member of the American Abstract Artists (AAA) and part of the movement center ...

and the Minimalists. He was celebrated posthumously in major exhibits at the Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is an art museum located in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, on 53rd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues.

It plays a major role in developing and collecting modern art, and is often identified as one of ...

(1936), the Guggenheim Museum

The Guggenheim Museums are a group of museums in different parts of the world established (or proposed to be established) by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Museums in this group include:

Locations

Americas

* The Solomon R. Guggenhei ...

(1973) and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1989), which has a large collection of his work. In the 1990s, the ownership claims of museums to many Malevich works began to be disputed by his heirs.

Early life

Kazimir Malevich was born Kazimierz Malewicz to aPolish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

family,N.D. (26 July 2013)Walczą o polskość Malewicza (Advocating the Polishness of Malewicz)

''Nowy Dziennik''. who settled near Kiev in

Kiev Governorate

Kiev Governorate, r=Kievskaya guberniya; uk, Київська губернія, Kyivska huberniia (, ) was an administrative division of the Russian Empire from 1796 to 1919 and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic from 1919 to 1925. It wa ...

of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

during the partitions of Poland. His parents, Ludwika and Seweryn Malewicz, were Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

like most ethnic Poles, though his father attended Orthodox services as well. They both had fled from the former eastern territories of the Commonwealth (present-day Kopyl

Kapyl ( be, Капы́ль, Kapyĺ, russian: Копыль, Kopyl; pl, Kopyl; lt, Kapylius; yi, קאפּוליע) is an urban settlement and the capital of Kapyl District in Belarus. It is located west-northwest of Slutsk and south-southwest o ...

Region of Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

) to Kiev in the aftermath of the failed Polish January Uprising of 1863 against the tsarist army.

His native language was Polish, but he also spoke Russian, as well as Ukrainian due to his childhood surroundings. Malevich would later write a series of articles in Ukrainian about art, and identified as Ukrainian.

Kazimir's father managed a sugar factory. Kazimir was the first of fourteen children, only nine of whom survived into adulthood. His family moved often and he spent most of his childhood in the villages of modern-day Ukraine, amidst sugar-beet plantations, far from centers of culture. Until age twelve, he knew nothing of professional artists, although art had surrounded him in childhood. He delighted in peasant embroidery, and in decorated walls and stoves. He was able to paint in the peasant style. He studied drawing in Kiev from 1895 to 1896.

Artistic career

From 1896 to 1904, Kazimir Malevich lived inKursk

Kursk ( rus, Курск, p=ˈkursk) is a city and the administrative center of Kursk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Kur, Tuskar, and Seym rivers. The area around Kursk was the site of a turning point in the Soviet–German stru ...

. In 1904, after the death of his father, he moved to Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

. He studied at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture

The Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture (russian: Московское училище живописи, ваяния и зодчества, МУЖВЗ) also known by the acronym MUZHZV, was one of the largest educational insti ...

from 1904 to 1910 and in the studio of Fedor Rerberg in Moscow. In 1911, he participated in the second exhibition of the group, '' Soyuz Molodyozhi'' (Union of Youth) in St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, together with Vladimir Tatlin

Vladimir Yevgrafovich Tatlin ( – 31 May 1953) was a Russian and USSR, Soviet painter, architect and stage-designer. Tatlin achieved fame as the architect who designed The Monument to the Third International, more commonly known as Tatlin's Towe ...

and, in 1912, the group held its third exhibition, which included works by Aleksandra Ekster

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "pr ...

, Tatlin, and others. In the same year, he participated in an exhibition by the collective, '' Donkey's Tail'' in Moscow. By that time, his works were influenced by Natalia Goncharova

Natalia Sergeevna Goncharova (russian: Ната́лья Серге́евна Гончаро́ва, p=nɐˈtalʲjə sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvnə ɡənʲtɕɪˈrovə; 3 July 188117 October 1962) was a Russian avant-garde artist, painter, costume designe ...

and Mikhail Larionov

Mikhail Fyodorovich Larionov ( Russian: Михаи́л Фёдорович Ларио́нов; June 3, 1881 – May 10, 1964) was a Russian avant-garde painter who worked with radical exhibitors and pioneered the first approach to abstract Ru ...

, Russian avant-garde painters, who were particularly interested in Russian folk art called ''lubok

A ''lubok'' (plural ''lubki'', Cyrillic: russian: лубо́к, лубо́чная картинка) is a Russian popular print, characterized by simple graphics and narratives derived from literature, religious stories, and popular tales. Lubki ...

''. Malevich described himself as painting in a " Cubo-Futurist" style in 1912. Honour, H. and Fleming, J. (2009) ''A World History of Art''. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing, pp. 794-795. In March 1913, a major exhibition of Aristarkh Lentulov's paintings opened in Moscow. The effect of this exhibition was comparable with that of Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne ( , , ; ; 19 January 1839 – 22 October 1906) was a French artist and Post-Impressionist painter whose work laid the foundations of the transition from the 19th-century conception of artistic endeavour to a new and radically d ...

in Paris in 1907, as all the main Russian avant-garde artists of the time (including Malevich) immediately absorbed the cubist

Cubism is an early-20th-century avant-garde art movement that revolutionized European painting and sculpture, and inspired related movements in music, literature and architecture. In Cubist artwork, objects are analyzed, broken up and reassemble ...

principles and began using them in their works. Already in the same year, the Cubo-Futurist opera, '' Victory Over the Sun'', with Malevich's stage-set, became a great success. In 1914, Malevich exhibited his works in the ''Salon des Indépendants

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon (Pa ...

'' in Paris together with Alexander Archipenko

Alexander Porfyrovych Archipenko (also referred to as Olexandr, Oleksandr, or Aleksandr; uk, Олександр Порфирович Архипенко, Romanized: Olexandr Porfyrovych Arkhypenko; February 25, 1964) was a Ukrainian and American ...

, Sonia Delaunay

Sonia Delaunay (13 November 1885 – 5 December 1979) was a French artist, who spent most of her working life in Paris. She was born in Odessa (then part of Russian Empire), and formally trained in Russian Empire and Germany before moving to Fr ...

, Aleksandra Ekster

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "pr ...

, and Vadim Meller, among others. Malevich also co-illustrated, with Pavel Filonov

Pavel Nikolayevich Filonov ( rus, Па́вел Никола́евич Фило́нов, p=ˈpavʲɪl nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ fʲɪˈlonəf, a=Pavyel Nikolayevich Filonov.ru.vorb.oga; January 8, 1883 – December 3, 1941) was a Russian avant-ga ...

, ''Selected Poems with Postscript, 1907–1914'' by Velimir Khlebnikov

Viktor Vladimirovich Khlebnikov, better known by the pen name Velimir Khlebnikov ( rus, Велими́р Хле́бников, p=vʲɪlʲɪˈmʲir ˈxlʲɛbnʲɪkəf; – 28 June 1922) was a Russian poet and playwright, a central part of th ...

and another work by Khlebnikov in 1914 titled ''Roar! Gauntlets, 1908–1914'', with Vladimir Burliuk. Later in that same year, he created a series of lithographs in support of Russia's entry into WWI. These prints, accompanied by captions by Vladimir Mayakovsky

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (, ; rus, Влади́мир Влади́мирович Маяко́вский, , vlɐˈdʲimʲɪr vlɐˈdʲimʲɪrəvʲɪtɕ məjɪˈkofskʲɪj, Ru-Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky.ogg, links=y; – 14 Apr ...

and published by the Moscow-based publication house Segodniashnii Lubok (Contemporary Lubok), on the one hand show the influence of traditional folk art, but on the other are characterised by solid blocks of pure colours juxtaposed in compositionally evocative ways that anticipate his Suprematist work.

In 1911, Brocard & Co. produced an eau de cologne called ''Severny''. Malevich conceived the advertisement and design of the perfume bottle with craquelure of an iceberg and a polar bear on the top, which lasted through the mid-1920s.

Suprematism

In 1915, Malevich laid down the foundations ofSuprematism

Suprematism (russian: Супремати́зм) is an early twentieth-century art movement focused on the fundamentals of geometry (circles, squares, rectangles), painted in a limited range of colors. The term ''suprematism'' refers to an abstra ...

when he published his manifesto, ''From Cubism to Suprematism''. In 1915–1916, he worked with other Suprematist artists in a peasant/artisan co-operative in Skoptsi and Verbovka village. In 1916–1917, he participated in exhibitions of the Jack of Diamonds group in Moscow together with Nathan Altman

Nathan Isaiovych Altman ( Ukrainian: , transliterated: ''Natan Isaiovych Altman''; – December 12, 1970) was a Russian, Soviet and Ukrainian artist, Cubist painter, stage designer and book illustrator.

Early life

He was born in Vinnytsia, i ...

, David Burliuk

David Davidovich Burliuk (Давид Давидович Бурлюк; 21 July 1882 – 15 January 1967) was a Russian-language poet, artist and publicist associated with the Futurist and Neo-Primitivist movements. Burliuk has been described as ...

, Aleksandra Ekster

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "pr ...

and others. Famous examples of his Suprematist works include ''Black Square

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have ...

'' (1915) and ''White On White

''Suprematist Composition: White on White'' (1918) is an abstract oil-on-canvas painting by Kazimir Malevich. It is one of the more well-known examples of the Russian Suprematism movement, painted the year after the October Revolution.

Part ...

'' (1918).

Malevich exhibited his first ''Black Square'', now at the Tretyakov Gallery

The State Tretyakov Gallery (russian: Государственная Третьяковская Галерея, ''Gosudarstvennaya Tretyâkovskaya Galereya''; abbreviated ГТГ, ''GTG'') is an art gallery in Moscow, Russia, which is considered th ...

in Moscow, at the Last Futurist Exhibition 0,10 in Petrograd (Saint Petersburg) in 1915. A black square placed against the sun appeared for the first time in the 1913 scenic designs for the Futurist

Futurists (also known as futurologists, prospectivists, foresight practitioners and horizon scanners) are people whose specialty or interest is futurology or the attempt to systematically explore predictions and possibilities abo ...

opera ''Victory over the Sun''. The second ''Black Square'' was painted around 1923. Some believe that the third ''Black Square'' (also at the Tretyakov Gallery) was painted in 1929 for Malevich's solo exhibition, because of the poor condition of the 1915 square. One more ''Black Square'', the smallest and probably the last, may have been intended as a diptych together with the ''Red Square

Red Square ( rus, Красная площадь, Krasnaya ploshchad', ˈkrasnəjə ˈploɕːətʲ) is one of the oldest and largest squares in Moscow, the capital of Russia. Owing to its historical significance and the adjacent historical build ...

'' (though of smaller size) for the exhibition Artists of the RSFSR: 15 Years, held in Leningrad (1932). The two squares, Black and Red, were the centerpiece of the show. This last square, despite the author's note ''1913'' on the reverse, is believed to have been created in the late twenties or early thirties, for there are no earlier mentions of it.

Malevich's student Anna Leporskaya

Anna Aleksandrovna Leporskaya (russian: А́нна Алекса́ндровна Лепо́рская; – March 14, 1982) was a Soviet avant-garde artist. She was a recipient of several awards, including Honored Artist of the RSFSR and the Repi ...

observed that Malevich "neither knew nor understood what the black square contained. He thought it so important an event in his creation that for a whole week he was unable to eat, drink or sleep."

In 1918, Malevich decorated a play, ''Mystery-Bouffe

''Mystery-Bouffe'' (russian: Мистерия-Буфф; Misteriya-Buff) is a socialist dramatic play written by Vladimir Mayakovsky in 1918/1921. Mayakovsky stated in a preface to the 1921 edition that "in the future, all persons performing, pres ...

'', by Vladimir Mayakovskiy produced by Vsevolod Meyerhold

Vsevolod Emilyevich Meyerhold (russian: Всеволод Эмильевич Мейерхольд, translit=Vsévolod Èmíl'evič Mejerchól'd; born german: Karl Kasimir Theodor Meyerhold; 2 February 1940) was a Russian and Soviet theatre ...

. He was interested in aerial photography

Aerial photography (or airborne imagery) is the taking of photographs from an aircraft or other airborne platforms. When taking motion pictures, it is also known as aerial videography.

Platforms for aerial photography include fixed-wing airc ...

and aviation

Aviation includes the activities surrounding mechanical flight and the aircraft industry. ''Aircraft'' includes fixed-wing and rotary-wing types, morphable wings, wing-less lifting bodies, as well as lighter-than-air craft such as hot a ...

, which led him to abstractions inspired by or derived from aerial landscape

::''(This article concerns painting and other non-photographic media. Otherwise, see aerial photography)''

Aerial landscape art includes paintings and other visual arts which depict or evoke the appearance of a landscape from a perspective abo ...

s.Julia Bekman Chadaga (2000). Conference paper, "Art, Technology, and Modernity in Russia and Eastern Europe". Columbia University, 2000. "the Suprematist is associated with a series of aerial views rendering the familiar landscape into an abstraction…"

Some Ukrainian authors argue that Malevich's Suprematism is rooted in the traditional Ukrainian culture.

Post-revolution

After theOctober Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

(1917), Malevich became a member of the Collegium on the Arts of Narkompros The People's Commissariat for Education (or Narkompros; russian: Народный комиссариат просвещения, Наркомпрос, directly translated as the "People's Commissariat for Enlightenment") was the Soviet agency charg ...

, the Commission for the Protection of Monuments and the Museums Commission (all from 1918–1919). He taught at the Vitebsk

Vitebsk or Viciebsk (russian: Витебск, ; be, Ві́цебск, ; , ''Vitebsk'', lt, Vitebskas, pl, Witebsk), is a city in Belarus. The capital of the Vitebsk Region, it has 366,299 inhabitants, making it the country's fourth-largest c ...

Practical Art School in Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

(1919–1922) alongside Marc Chagall, the Leningrad Academy of Arts (1922–1927), the Kiev Art Institute (1928–1930),Filevska, Tetiana"The Ukrainian Museum will be displaying new materials highlighting artistic modernism in Ukraine: Kazimir Malevich.Kyiv Period"

11 February 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2020. and the House of the Arts in Leningrad (1930). He wrote the book ''The World as Non-Objectivity'', which was published in

Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

in 1926 and translated into English in 1959. In it, he outlines his Suprematist theories.

In 1923, Malevich was appointed director of Petrograd State Institute of Artistic Culture, which was forced to close in 1926 after a Communist party newspaper called it "a government-supported monastery" rife with "counterrevolutionary sermonizing and artistic debauchery." The Soviet state was by then heavily promoting an idealized, propagandistic style of art called Socialist Realism

Socialist realism is a style of idealized realistic art that was developed in the Soviet Union and was the official style in that country between 1932 and 1988, as well as in other socialist countries after World War II. Socialist realism is c ...

—a style Malevich had spent his entire career repudiating. Nevertheless, he swam with the current, and was quietly tolerated by the Communists.

International recognition and banning

In 1927, Malevich traveled to

In 1927, Malevich traveled to Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

where he was given a hero's welcome. There, he met with artists and former students Władysław Strzemiński and Katarzyna Kobro, whose own movement, Unism, was highly influenced by Malevich. He held his first foreign exhibit in the Hotel Polonia Palace. From there, the painter ventured on to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

and Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

for a retrospective which finally brought him international recognition. He arranged to leave most of the paintings behind when he returned to the Soviet Union. Malevich's assumption that a shifting in the attitudes of the Soviet authorities toward the modernist

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

art movement would take place after the death of Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

and Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

's fall from power was proven correct in a couple of years, when the government of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

turned against forms of abstraction, considering them a type of " bourgeois" art, that could not express social realities. As a consequence, many of his works were confiscated and he was banned from creating and exhibiting similar art.

In autumn 1930, he was arrested and interrogated by the KGB

The KGB (russian: links=no, lit=Committee for State Security, Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), a=ru-KGB.ogg, p=kəmʲɪˈtʲet ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əj bʲɪzɐˈpasnəsʲtʲɪ, Komitet gosud ...

in Leningrad, accused of Polish espionage, and threatened with execution. He was released from imprisonment In early December.

Critics derided Malevich's art as a negation of everything good and pure: love of life and love of nature. The Westernizer artist and art historian Alexandre Benois

Alexandre Nikolayevich Benois (russian: Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Бенуа́, also spelled Alexander Benois; ,Salmina-Haskell, Larissa. ''Russian Paintings and Drawings in the Ashmolean Museum''. pp. 15, 23-24. Published by ...

was one such critic. Malevich responded that art can advance and develop for art's sake alone, saying that "art does not need us, and it never did".

Death

When Malevich died ofcancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

at the age of fifty-seven, in Leningrad on 15 May 1935, his friends and disciples buried his ashes in a grave marked with a black square. They didn't fulfill his stated wish to have the grave topped with an "architekton"—one of his skyscraper-like maquette

A ''maquette'' (French word for scale model, sometimes referred to by the Italian names ''plastico'' or ''modello'') is a scale model or rough draft of an unfinished sculpture. An equivalent term is ''bozzetto'', from the Italian word for "sketc ...

s of abstract forms, equipped with a telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observ ...

through which visitors were to gaze at Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousandth t ...

.

On his deathbed, Malevich had been exhibited with the ''Black Square'' above him, and mourners at his funeral rally were permitted to wave a banner bearing a black square. Malevich had asked to be buried under an oak tree on the outskirts of Nemchinovka, a place to which he felt a special bond.Sophia Kishkovsky (30 August 2013)Malevich’s Burial Site Is Found, Underneath Housing Development

''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

''. His ashes were sent to Nemchinovka, and buried in a field near his dacha

A dacha ( rus, дача, p=ˈdatɕə, a=ru-dacha.ogg) is a seasonal or year-round second home, often located in the exurbs of post-Soviet countries, including Russia. A cottage (, ') or shack serving as a family's main or only home, or an outbu ...

. Nikolai Suetin, a friend of Malevich's and a fellow artist, designed a white cube with a black square to mark the burial site. The memorial was destroyed during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. The city of Leningrad bestowed a pension on Malevich's mother and daughter.

In Nazi Germany his works were banned as "Degenerate Art

Degenerate art (german: Entartete Kunst was a term adopted in the 1920s by the Nazi Party in Germany to describe modern art. During the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, German modernist art, including many works of internationally renowned artists, ...

".

In 2013, an apartment block was built on the place of the tomb and burial site of Kazimir Malevich. Another nearby monument to Malevich, put up in 1988, is now also situated on the grounds of a gated community.

Painting technique

According to an observation by radiologist and art historian Milda Victurina, one of the features of Kazimir Malevich's painting technique was the layering of paints one on another to get a special kind of colour spots. For example, Malevich used two layers of colour for the red spot—the lower black and the upper red. The light ray going through these colour layers is perceived by the viewer not as red, but with a touch of darkness. This technique of superimposing the two colours allowed experts to identify fakes of Malevich's work, which generally lacked it.Polish ethnicity

Malevich's family was one of the millions of Poles who lived within the Russian Empire following the Partitions of Poland. Kazimir Malevich was born near Kiev on lands that had previously been part of the

Malevich's family was one of the millions of Poles who lived within the Russian Empire following the Partitions of Poland. Kazimir Malevich was born near Kiev on lands that had previously been part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ru ...

of parents who were ethnic Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in C ...

.

Both Polish, Ukrainian and Russian were native languages of Malevich, who would sign his artwork in the Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

form of his name as ''Kazimierz Malewicz''. In a visa application to travel to France, Malewicz claimed ''Polish'' as his nationality. French art historian Andrei Nakov

Andrei, Andrey or Andrej (in Cyrillic script: Андрэй , Андрей or Андреј) is a form of Andreas/ Ἀνδρέας in Slavic languages and Romanian. People with the name include:

*Andrei of Polotsk (–1399), Lithuanian nobleman

*An ...

, who re-established Malevich's birth year as 1879 (and not 1878), has argued for restoration of the Polish spelling of Malevich's name.

In 1985, Polish performance artist Zbigniew Warpechowski performed "Citizenship for a Pure Feeling of Kazimierz Malewicz" as an homage to the great artist and critique of Polish authorities that refused to grant Polish citizenship to Kazimir Malevich. In 2013, Malevich's family in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

and fans founded the not-for-profit ''The Rectangular Circle of Friends of Kazimierz Malewicz'', whose dedicated goal is to promote awareness of Kazimir's Polish ethnicity.

Russian art historian gained access to the artist's criminal case and found that in some documents Malevich specified his nationality as Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

.

Posthumous exhibitions

Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is an art museum located in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, on 53rd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues.

It plays a major role in developing and collecting modern art, and is often identified as one of ...

in New York in 1936. In 1939, the Museum of Non-Objective Painting opened in New York, whose founder, Solomon R. Guggenheim

Solomon Robert Guggenheim (February 2, 1861 – November 3, 1949) was an American businessman and art collector. He is best known for establishing the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City.

Guggen ...

—an early and passionate collector of the Russian avant-garde—was inspired by the same aesthetic ideals and spiritual quest that exemplified Malevich's art.Malevich and the American Legacy, March 3 - April 30, 2011Gagosian Gallery

Gagosian is a contemporary art gallery owned and directed by Larry Gagosian. The gallery exhibits some of the most influential artists of the 20th and 21st centuries. There are 16 gallery spaces: five in New York City; three in London; two in P ...

, New York.

The first U.S. retrospective of Malevich's work in 1973 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, often referred to as The Guggenheim, is an art museum at 1071 Fifth Avenue on the corner of East 89th Street on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City. It is the permanent home of a continuously exp ...

provoked a flood of interest and further intensified his impact on postwar American and European artists. However, most of Malevich's work and the story of the Russian avant-garde remained under lock and key until Glasnost. In 1989, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam held the West's first large-scale Malevich retrospective, including the paintings they owned and works from the collection of Russian art critic Nikolai Khardzhiev.

Collections

Malevich's works are held in several major art museums, including theState Tretyakov Gallery

The State Tretyakov Gallery (russian: Государственная Третьяковская Галерея, ''Gosudarstvennaya Tretyâkovskaya Galereya''; abbreviated ГТГ, ''GTG'') is an art gallery in Moscow, Russia, which is considered th ...

in Moscow, and in New York, the Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is an art museum located in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, on 53rd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues.

It plays a major role in developing and collecting modern art, and is often identified as one of ...

and the Guggenheim Museum

The Guggenheim Museums are a group of museums in different parts of the world established (or proposed to be established) by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Museums in this group include:

Locations

Americas

* The Solomon R. Guggenhei ...

. The Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam owns 24 Malevich paintings, more than any other museum outside of Russia. Another major collection of Malevich works is held by the State Museum of Contemporary Art

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

in Thessaloniki.

Art market

''Black Square'', the fourth version of his

''Black Square'', the fourth version of his magnum opus

A masterpiece, ''magnum opus'' (), or ''chef-d’œuvre'' (; ; ) in modern use is a creation that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of outstanding creativity, ...

painted in the 1920s, was discovered in 1993 in Samara and purchased by Inkombank

Vladimir Viktorovich Vinogradov (Russian Владимир Викторович Виноградов) (19 September 1955 in Ufa — 29 June 2008 in Moscow) was the owner and president of Inkombank, one of the largest banks in 90s' Russia. Considere ...

for US$250,000. In April 2002, the painting was auction

An auction is usually a process of buying and selling goods or services by offering them up for bids, taking bids, and then selling the item to the highest bidder or buying the item from the lowest bidder. Some exceptions to this definition ex ...

ed for an equivalent of US$1 million. The purchase was financed by the Russian philanthropist Vladimir Potanin

Vladimir Olegovich Potanin (russian: Владимир Олегович Потанин; born 3 January 1961) is a Russian billionaire businessman. He acquired his wealth notably through the controversial loans-for-shares program in Russia in ...

, who donated funds to the Russian Ministry of Culture, and ultimately, to the State Hermitage Museum collection. According to the Hermitage website, this was the largest private contribution to state art museums since the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

.

In 2008, the Stedelijk Museum restituted five works to the heirs of Malevich's family from a group that had been left in Berlin by Malevich, and acquired by the gallery in 1958, in exchange for undisputed title to the remaining pictures.

On 3 November 2008, one of these works entitled '' Suprematist Composition'' from 1916, set the world record for any Russian work of art and any work sold at auction for that year, selling at Sotheby's

Sotheby's () is a British-founded American multinational corporation with headquarters in New York City. It is one of the world's largest brokers of fine and decorative art, jewellery, and collectibles. It has 80 locations in 40 countries, an ...

in New York City for just over US$60 million (surpassing his previous record of US$17 million set in 2000).

In May 2018, the same painting '' Suprematist Composition'' 1916 sold at Christie's New York for over US$85 million (including fees), a record auction price for a Russian work of art.

In popular culture

Malevich's life inspires many references featuring events and the paintings as players. The smuggling of Malevich paintings out of Russia is a key to the plot line of writerMartin Cruz Smith

Martin Cruz Smith (born November 3, 1942) is an American mystery novelist. He is best known for his nine-novel series (to date) on Russian investigator Arkady Renko, who was first introduced in 1981 with '' Gorky Park''.

Early life and educ ...

's thriller ''Red Square

Red Square ( rus, Красная площадь, Krasnaya ploshchad', ˈkrasnəjə ˈploɕːətʲ) is one of the oldest and largest squares in Moscow, the capital of Russia. Owing to its historical significance and the adjacent historical build ...

''. Noah Charney

Noah Charney (born November 27, 1979) is an American art historian and novelist. He is the author of ''The Art Thief,'' a mystery novel about a series of thefts from European museums and churches, and is the founder of the Association for Res ...

's novel, ''The Art Thief'' tells the story of two stolen Malevich ''White on White'' paintings, and discusses the implications of Malevich's radical Suprematist compositions on the art world. British artist Keith Coventry has used Malevich's paintings to make comments on modernism, in particular his Estate Paintings. Malevich's work also is featured prominently in the Lars von Trier

Lars von Trier ('' né'' Trier; 30 April 1956) is a Danish filmmaker, actor, and lyricist. Having garnered a reputation as a highly ambitious, polarizing filmmaker, he has been the subject of several controversies: Cannes, in addition to nomina ...

film, ''Melancholia

Melancholia or melancholy (from el, µέλαινα χολή ',Burton, Bk. I, p. 147 meaning black bile) is a concept found throughout ancient, medieval and premodern medicine in Europe that describes a condition characterized by markedly d ...

''. At the Closing Ceremony of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Malevich visual themes were featured (via projections) in a section on 20th century Russian modern art.

Selected works

* 1912 – ''Morning in the Country after Snowstorm'' * 1912 – ''The Woodcutter'' * 1912–13 – ''Reaper on Red Background '' * 1914 – ''The Aviator'' * 1914 – '' An Englishman in Moscow'' * 1914 – ''Soldier of the First Division'' * 1915 – ''Black Square

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have ...

''

* 1915 – ''Red Square'' †

* 1915 – ''Black Square and Red Square'' ††

* 1915 – '' Suprematist Composition''

* 1915 – ''Suprematism (1915)''

* 1915 – ''Suprematist Painting: Aeroplane Flying''

* 1915 – ''Suprematism: Self-Portrait in Two Dimensions''

* 1915–16 – ''Suprematist Painting (Ludwigshafen)''

* 1916 – ''Suprematist Painting (1916)''

* 1916 – ''Supremus Supremus (; 1915–1916) was a group of Russian avant-garde artists led by the "father" of Suprematism, Kazimir Malevich. It has been described as the first attempt to found the Russian avant-garde movement as an artistic entity within its own histo ...

No. 56''

* 1916–17 – ''Suprematism (1916–17)''

* 1917 – ''Suprematist Painting (1917)''

* 1918 – ''White on White

''Suprematist Composition: White on White'' (1918) is an abstract oil-on-canvas painting by Kazimir Malevich. It is one of the more well-known examples of the Russian Suprematism movement, painted the year after the October Revolution.

Part ...

''

* 1919–1926 – '' Untitled (Suprematist Composition)''

* 1928–1932 – ''Complex Presentiment: Half-Figure in a Yellow Shirt''

* 1932–1934 – ''Running Man''

† Also known as ''Red Square: Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions''.†† Also known as ''Black Square and Red Square: Painterly Realism of a Boy with a Knapsack - Color Masses in the Fourth Dimension''.

Gallery

Black Circle

''Black Circle'' (or ''motive 1915'') is a 1924 oil on canvas painting by the Kiev-born Russian artist Kazimir Malevich, founder of the Russian Suprematism movement. From the mid-1910s, Malevich abandoned any trace of figurature or representat ...

'', motive 1915, painted 1924, State Russian Museum

The State Russian Museum (russian: Государственный Русский музей), formerly the Russian Museum of His Imperial Majesty Alexander III (russian: Русский Музей Императора Александра III), on ...

, St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, Russia

File:Казимир Малевич, Супрематическая композиция, 1915.jpg, ''Suprematist Composition'', painted in 1915

File:Kazimir malevich, quadrato rosso (realismo del pittore di una campagnola in due dimensioni), 1915.JPG, '' Red Square: Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions'', 1915

File:Suprematist Composition - Kazimir Malevich.jpg, '' Suprematist Composition'', 1916

File:Malevich-Suprematism..jpg, ''Suprematist Painting: Eight Red Rectangles'', 1915

File:Malevici06.jpg, ''Suprematism'', Museum of Art, Krasnodar

Krasnodar (; rus, Краснода́р, p=krəsnɐˈdar; ady, Краснодар), formerly Yekaterinodar (until 1920), is the largest city and the administrative centre of Krasnodar Krai, Russia. The city stands on the Kuban River in southe ...

1916

File:GUGG Untitled (Suprematist Composition, Malevich a).jpg, ''Untitled (Suprematist Composition)'', Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, often referred to as The Guggenheim, is an art museum at 1071 Fifth Avenue on the corner of East 89th Street on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City. It is the permanent home of a continuously exp ...

, New York City, c. 1919-1926

File:GUGG Untitled (Suprematist Composition, Malevich b).jpg, ''Untitled (Suprematist Composition)'', Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, often referred to as The Guggenheim, is an art museum at 1071 Fifth Avenue on the corner of East 89th Street on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City. It is the permanent home of a continuously exp ...

, New York City, c. 1919-1926

File:Malevich.black-square.jpg, ''Black Square

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have ...

'', c.1923, State Russian Museum

The State Russian Museum (russian: Государственный Русский музей), formerly the Russian Museum of His Imperial Majesty Alexander III (russian: Русский Музей Императора Александра III), on ...

, St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, Russia

File:Black Cross.jpg, ''Black Cross'', 1920s, State Russian Museum

The State Russian Museum (russian: Государственный Русский музей), formerly the Russian Museum of His Imperial Majesty Alexander III (russian: Русский Музей Императора Александра III), on ...

, St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, Russia

File:Malevitj.jpg, ''Suprematism'', 1921-1927

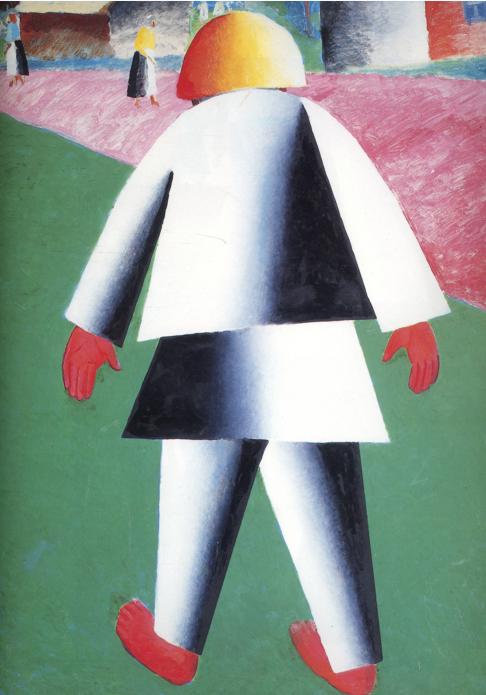

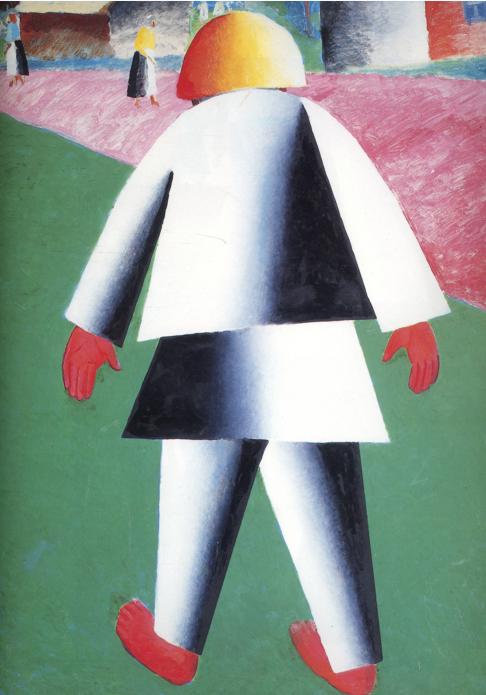

File:Malevich - Boy.jpg, ''Boy'', 1928-1932

File:Malevich cavalry.jpg, ''Red Cavalry

''Red Cavalry'' or ''Konarmiya'' (russian: Конармия) is a collection of short stories by Russian author Isaac Babel about the 1st Cavalry Army. The stories take place during the Polish–Soviet War and are based on Babel's diary, which ...

'', 1928-1932

File:Malevich Summer Landscape.JPG, ''Summer Landscape'', 1929

File:Malevich142.jpg, ''Mower'', 1930

File:Malevich running-man.jpg, ''Running man'', 1932

File:Казимир Малевич — Важке передчуття.jpg, ''Complex Presentiment: Half-Figure in a Yellow Shirt'', 1928-1932

See also

* List of Russian artists *Sergei Senkin

Sergei Yakovlevich Senkin (1894–1963) was a twentieth-century Russian artist, photographer, and illustrator.

Senkin studied with Kasimir Malevitch during the 1920s in Vkhutemas. He sometimes visited Malevitch in Vitebsk with his friend Gustav ...

* Oberiu

* UNOVIS

UNOVIS (also known as MOLPOSNOVIS and POSNOVIS) was a short-lived but influential group of artists, founded and led by Kazimir Malevich at the Vitebsk Art School in 1919.

Initially formed by students and known as MOLPOSNOVIS, the group formed ...

Footnotes

Citations

References

* Crone, Rainer, Kazimir Severinovich Malevich, and David Moos. ''Kazimir Malevich: The Climax of Disclosure.'' Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991. * Dreikausen, Margret, ''Aerial Perception: The Earth as Seen from Aircraft and Spacecraft and Its Influence on Contemporary Art'' (Associated University Presses:Cranbury, NJ

Cranbury is a township in Middlesex County, New Jersey, United States. Located within the Raritan Valley region, Cranbury is roughly equidistant between New York City and Philadelphia in the heart of the state. As of the 2010 United States Ce ...

; London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, England; Mississauga, Ontario: 1985).

* Drutt, Matthew; Malevich, Kazimir, ''Kazimir Malevich: suprematism'', Guggenheim Museum, 2003,

* Honour, H. and Fleming, J. (2009) ''A World History of Art''. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing.

* Malevich, Kasimir, ''The Non-objective World'', Chicago: P. Theobald, 1959.

* ''Malevich and his Influence'', Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein

The Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein ( English: ''Liechtenstein Museum of Fine Arts'') is the state museum of modern and contemporary art in Vaduz, Liechtenstein. The building by the Swiss architects Meinrad Morger, Heinrich Degelo and Christian Kere ...

, 2008.

* Milner, John; Malevich, Kazimir, ''Kazimir Malevich and the art of geometry'', Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day, and became an official department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and operationally autonomous.

, Yale Universi ...

, 1996.

* Nakov, Andrei, ''Kasimir Malevich, Catalogue raisonné'', Paris, Adam Biro, 2002

* Nakov, Andrei, vol. IV of ''Kasimir Malevich, le peintre absolu'', Paris, Thalia Édition, 2007

* Néret, Gilles, ''Kazimir Malevich and Suprematism 1878-1935'', Taschen, 2003.

* Petrova, Yevgenia, ''Kazimir Malevich in the State Russian Museum''. Palace Editions, 2002. . (English Edition)

* Shatskikh, Aleksandra S, and Marian Schwartz, ''Black Square: Malevich and the Origin of Suprematism'', 2012.

* Shishanov, V.A. ''Vitebsk Museum of Modern Art

Vitebsk Museum of Modern Art (russian: Витебский Музей Современного Искусства) was an art museum in Vitebsk, Belarus organized in 1918 by Marc Chagall, Kazimir Malevich and Alexander Romm. In 1921, it exhibited 1 ...

: a History of Creation and a Collection''. 1918–1941. - Minsk: Medisont, 2007. - 144 p.Mylivepage.ru

' * Tedman, Gary. Soviet Avant Garde Aesthetics, chapter from Aesthetics & Alienation. pp 203–229. 2012. Zero Books. * Tolstaya, Tatyana

''The Square''

''The New Yorker'', 12 June 2015 * Das weiße Rechteck. Schriften zum Film, herausgegeben von Oksana Bulgakowa. PotemkinPress, Berlin 1997, * ''The White Rectangle. Writings on Film.'' (In English and the Russian original manuscript). Edited by Oksana Bulgakowa. PotemkinPress, Berlin / Francisco 2000,

Autobiographies

Malevich wrote two biographical essays, a shorter one in 1923–25, and a much longer account in 1933, representing the artist's explanation of his own evolution up to the appearance of suprematism at the 1915 "0–10" exhibition in Petrograd. Both are published in: * Abridged and revised translations are published in: * The 1923–25 autobiography appears in: * The 1933 autobiography appears in: * *External links

Malevich works, MoMA

Kazimir Malevich, Guggenheim Collection Online

Based on the work Goncharova, Malevich, Roerich, Stravinsky and Prokofiev

Peter Brooke, ''Deux Peintres Philosophes - Albert Gleizes et Kasimir Malévitch and Quelques Réflexions sur la Littérature Actuelle du Cubisme''

both Ampuis (Association des Amis d’Albert Gleizes) 1995

History of Malevich-designed Perfume bottle of the eau de cologne “''Severny''”

{{DEFAULTSORT:Malevich, Kazimir 1879 births 1935 deaths Abstract painters Artists from Kyiv Ukrainian people of Polish descent 19th-century painters from the Russian Empire 20th-century Russian painters Futurist painters People from the Russian Empire of Polish descent Painters from the Russian Empire Russian male painters Modern painters Polish painters Polish male painters Russian avant-garde Soviet painters Suprematism (art movement) Ukrainian avant-garde Ukrainian painters Ukrainian male painters Ukrainian sculptors Ukrainian male sculptors Deaths from prostate cancer Deaths from cancer in the Soviet Union 19th-century male artists from the Russian Empire 20th-century Russian male artists Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture alumni