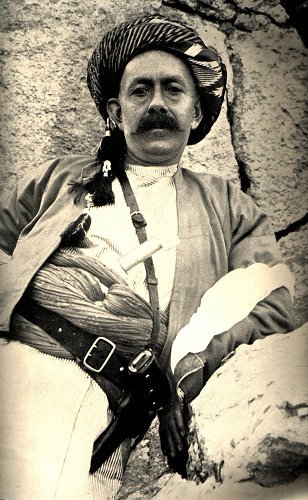

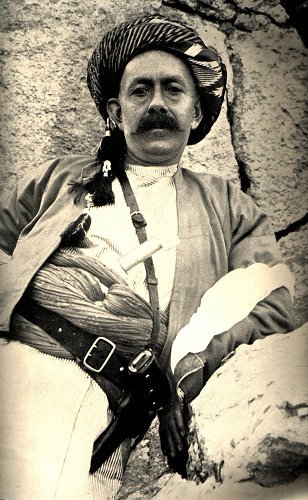

Mahmud Barzanji on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sheikh Mahmud Barzanji ( ku, ШҙЫҺШ® Щ…ЩҮвҖҢШӯЩ…ЩҲЩҲШҜ ШЁЫ•ШұШІЩҶШ¬ЫҢ) or Mahmud Hafid Zadeh (1878 вҖ“ October 9, 1956) was a Kurdish leader of a series of Kurdish uprisings against the British Mandate of

Mahmud was a very ambitious Kurdish national leader and promoted the idea of Kurds controlling their own state and gaining independence from the British. As Charles Tripp relates, the British appointed him governor of Sulaimaniah in southern Kurdistan as a way of gaining an indirect rule in this region. The British wanted this indirect rule with the popular Mahmud at the helm, which they believed would give them a face and a leader to control and calm the region. However, with a little taste of power, Mahmud had ambitions for more for himself and for the Kurdish people. He was declared "King of Kurdistan" and claimed to be the ruler of all Kurds, but the opinion of Mahmud among Kurds was mixed because he was becoming too powerful and ambitious for some.

Mahmud hoped to create Kurdistan and initially the British allowed Mahmud to pursue has ambitions because he was bringing the region and people together under indirect British control. However, by 1920 Mahmud, to British displeasure, was using his power against the British by arresting British officials in the Kurd region and starting uprisings against the British. As historian Kevin McKierman writes, "The rebellion lasted until Mahmud was wounded in combat, which occurred on the road between

Mahmud was a very ambitious Kurdish national leader and promoted the idea of Kurds controlling their own state and gaining independence from the British. As Charles Tripp relates, the British appointed him governor of Sulaimaniah in southern Kurdistan as a way of gaining an indirect rule in this region. The British wanted this indirect rule with the popular Mahmud at the helm, which they believed would give them a face and a leader to control and calm the region. However, with a little taste of power, Mahmud had ambitions for more for himself and for the Kurdish people. He was declared "King of Kurdistan" and claimed to be the ruler of all Kurds, but the opinion of Mahmud among Kurds was mixed because he was becoming too powerful and ambitious for some.

Mahmud hoped to create Kurdistan and initially the British allowed Mahmud to pursue has ambitions because he was bringing the region and people together under indirect British control. However, by 1920 Mahmud, to British displeasure, was using his power against the British by arresting British officials in the Kurd region and starting uprisings against the British. As historian Kevin McKierman writes, "The rebellion lasted until Mahmud was wounded in combat, which occurred on the road between

With the exile of the Sheikh in India, Turkish nationalists in the crumbling Ottoman Empire were causing a great deal of trouble in the Kurdish regions of Iraq. The Turkish nationalists, led by Mustafa Kemal, were riding high in the early 1920s after their victory against

With the exile of the Sheikh in India, Turkish nationalists in the crumbling Ottoman Empire were causing a great deal of trouble in the Kurdish regions of Iraq. The Turkish nationalists, led by Mustafa Kemal, were riding high in the early 1920s after their victory against

Ethnic Cleansing and the Kurds

in German {{DEFAULTSORT:Barzanji, Mahmud 1878 births 1956 deaths People from Sulaymaniyah Iraqi Kurdistani politicians Kurdish people from the Ottoman Empire Iraqi Kurdish people Kurdish rulers Kingdom of Kurdistan Kurdish nationalists Kurdish revolutionaries Burials in Iraq Iraqi exiles Iraqi expatriates in India Iraqi revolt of 1920

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, Ш№ЫҺШұШ§ЩӮ, translit=ГҠraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, Ъ©ЫҶЩ…Ш§ШұЫҢ Ш№ЫҺШұШ§ЩӮ, translit=KomarГ® ГҠraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to IraqвҖ“Turkey border, the north, Iran to IranвҖ“Iraq ...

. He was sheikh

Sheikh (pronounced or ; ar, ШҙЩҠШ® ' , mostly pronounced , plural ' )вҖ”also transliterated sheekh, sheyikh, shaykh, shayk, shekh, shaik and Shaikh, shakвҖ”is an honorific title in the Arabic language. It commonly designates a chief of a ...

of a Qadiriyah Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aб№Ј-б№ЈЕ«fiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taб№Јawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

family of the Barzanji clan from the city of Sulaymaniyah

Sulaymaniyah, also spelled as Slemani ( ku, ШіЩ„ЫҺЩ…Ш§ЩҶЫҢ, SilГӘmanГ®, ar, Ш§Щ„ШіЩ„ЩҠЩ…Ш§ЩҶЩҠШ©, as-SulaymДҒniyyah), is a city in the east of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, not far from the IranвҖ“Iraq border. It is surrounded by the Azmar, G ...

, which is now in Iraqi Kurdistan

Iraqi Kurdistan or Southern Kurdistan ( ku, ШЁШ§ШҙЩҲЩҲШұЫҢ Ъ©ЩҲШұШҜШіШӘШ§ЩҶ, BaЕҹГ»rГӘ KurdistanГӘ) refers to the Kurdish-populated part of northern Iraq. It is considered one of the four parts of "Kurdistan" in Western Asia, which also inc ...

. He was named King of Kurdistan during several of these uprisings.

Background

AfterWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, the British and other Western powers occupied parts of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, РһОёПүОјОұОҪО№ОәО® О‘П…П„ОҝОәПҒОұП„ОҝПҒОҜОұ, OthЕҚmanikД“ Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

. Plans made with the French in the SykesвҖ“Picot Agreement

The SykesвҖ“Picot Agreement () was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Italy, to define their mutually agreed spheres of influence and control in an eventual partition ...

designated Britain as the mandate power. The British were able to form their own borders to their pleasure to gain an advantage in this region. The British had firm control of Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, ШЁЩҺШәЩ’ШҜЩҺШ§ШҜ , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

and Basra

Basra ( ar, ЩұЩ„Щ’ШЁЩҺШөЩ’ШұЩҺШ©, al-Baб№Јrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

and the regions around these cities mostly consisted of Shiite

ShД«Кҝa Islam or ShД«КҝД«sm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated КҝAlД« ibn AbД« ṬДҒlib as his successor (''khalД«fa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, most ...

and Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85вҖ“90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a dis ...

Arabs.

In 1921, the British appointed Faisal I the King of Iraq. It was an interesting choice because Faisal had no local connections, as he was part of the Hashemite

The Hashemites ( ar, Ш§Щ„ЩҮШ§ШҙЩ…ЩҠЩҲЩҶ, al-HДҒshimД«yЕ«n), also House of Hashim, are the royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Hejaz (1916вҖ“1925), Syria (1920), and Iraq (1921в ...

family in Western Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, ШҙЩҗШЁЩ’ЩҮЩҸ Ш§Щ„Щ’Ш¬ЩҺШІЩҗЩҠШұЩҺШ©Щҗ Ш§Щ„Щ’Ш№ЩҺШұЩҺШЁЩҗЩҠЩҺЩ‘Ш©, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Pl ...

. As events were unfolding in the southern part of Iraq, the British were also developing new policies in northern Iraq, which was primarily inhabited by Kurds, and was known as Greater Kurdistan in the Paris (Versailles) Peace Conference of 1919. The borders that the British formed had the Kurds between central Iraq (Baghdad) and the Ottoman lands of the north.

The Kurdish people of Iraq lived in the mountainous and terrain of the Mosul Vilayet. It was a difficult region to control from the British perspective because of the terrain and tribal loyalties of the Kurds. There was much conflict after the Great War between the Ottoman government and British on how the borders should be established. The Ottomans were unhappy with the outcome of the Treaty of SГЁvres

The Treaty of SГЁvres (french: TraitГ© de SГЁvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

, which allowed the Great War victors control over much of the former Ottoman lands through the distribution of formerly Ottoman territory as League of Nations mandates.

In particular, the Turks felt that the Mosul Vilayet was theirs because the British had illegally conquered it after the Mudros Armistice, which had ended hostilities in the war. With the discovery of oil in northern Iraq, the British were unwilling to relinquish the Mosul Vilayet. Also, it was to the British advantage to have the Kurds play a buffer role between themselves and the Ottoman Empire. All that led to the importance of Sheikh Mahmud Barzanji.

The British government promised the Kurds during the First World War that they would receive their own land to form a Kurdish state. However, the British government did not keep their promise at the end of the war, leading to resentment among the Kurds.

There was mistrust on the part of the Kurds. In 1919, uneasiness began to evolve in the Kurdish regions because they were unhappy with their current situation and in their dealings with the British government. The Kurds revolted

In political science, a revolution ( Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically d ...

a year later.

The British government attempted to establish a Kurdish protectorate in the region and so appointed a popular leader of the region, which was how Mahmud became governor of southern Kurdistan.

Power and revolts

Kirkuk

Kirkuk ( ar, ЩғШұЩғЩҲЩғ, ku, Ъ©Ы•ШұЪ©ЩҲЩҲЪ©, translit=KerkГ»k, , tr, KerkГјk) is a city in Iraq, serving as the capital of the Kirkuk Governorate, located north of Baghdad. The city is home to a diverse population of Turkmens, Arabs, Kurds ...

and Sulaimaniah. Captured by British forces, he was sentenced to death but later imprisoned in a British fort in India." Mahmud remained in India until 1922.

Return and second revolt

With the exile of the Sheikh in India, Turkish nationalists in the crumbling Ottoman Empire were causing a great deal of trouble in the Kurdish regions of Iraq. The Turkish nationalists, led by Mustafa Kemal, were riding high in the early 1920s after their victory against

With the exile of the Sheikh in India, Turkish nationalists in the crumbling Ottoman Empire were causing a great deal of trouble in the Kurdish regions of Iraq. The Turkish nationalists, led by Mustafa Kemal, were riding high in the early 1920s after their victory against Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

and were looking to take that momentum into Iraq and take back Mosul

Mosul ( ar, Ш§Щ„Щ…ЩҲШөЩ„, al-Mawб№Јil, ku, Щ…ЩҲЩҲШіЪө, translit=MГ»sil, Turkish: ''Musul'', syr, ЬЎЬҳЬЁЬ , MДҒwб№Јil) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. The city is considered the second larg ...

. With the British in direct control of northern Iraq after the exile of Sheikh Mahmud, the area was becoming increasingly hostile for the British officials due to the threat from Turkey. The region was led by the Sheikh's brother, Sheikh Qadir, who was not capable of handling the situation and was seen by the British as an unstable and unreliable leader.

Sir Percy Cox, a British military official and administrator to the Middle East especially Iraq, and Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, a British politician, were at odds on whether to release the Sheikh from his exile and bring him back to reign in northern Iraq. That would allow the British to have better control over the hostile but important region. Cox argued that the British could gain authority in a region they recently evacuated, and the Sheikh was the only hope of gaining back a stable region. Cox was aware of the dangers of bringing back the Sheikh, but he was also aware that one of the main reasons for the unrest in the region was the growing perception that the earlier promises of autonomy would be abandoned and the British would bring the Kurdish people under direct rule of the Arab government in Baghdad. The Kurdish dream of an independent state was growing less likely which caused conflict in the region. Bringing the Sheikh back was their only chance of a peaceful Iraqi state in the region and against Turkey.

Cox agreed to bring back the Sheikh and name him governor of southern Kurdistan. On December 20, 1922, Cox also agreed to a joint Anglo-Iraqi declaration that would allow a Kurdish government if they were able to form a constitution and agree on boundaries. Cox knew that with the instability in the region and the fact that there were many Kurdish groups it would be nearly impossible for them to come to a solution. Upon his return, Mahmud proceeded to pronounce himself King of the Kingdom of Kurdistan. The Sheikh rejected the deal with the British and began working in alliance with the Turks against the British. Cox realized the situation and in 1923 he denied the Kurds any say in the Iraqi government and withdrew his offer of their own independent state. The Sheikh was the king until 1924 and was involved in uprisings against the British until 1932, when the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

and British-trained Iraqis were able to capture the Sheikh again and exile him to southern Iraq.

Death and legacy

Sheikh sued for peace and was exiled in southern Iraq in May 1932 and was able to return to his family village in 1941 where he remained the rest of his years. He ultimately died in 1956 with his family. He is still remembered today with displays of him around Iraqi Kurdistan and especially in Sulaimaniah. He is a hero to the Kurdish people to this day, as he is thought of as an pioneering Kurdish nationalist who fought for the independence and respect of his people. He is regarded as a pioneer for many future Kurd leaders.See also

*Kingdom of Kurdistan

The Kingdom of Kurdistan was a short-lived Kurdish state proclaimed in the city of Sulaymaniyah following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Officially, the territory involved was under the jurisdiction of the British Mandate of Mesopotamia.

...

*RAF Iraq Command

Iraq Command was the Royal Air Force (RAF) commanded inter-service command in charge of British forces in Iraq in the 1920s and early 1930s, during the period of the British Mandate of Mesopotamia. It continued as British Forces in Iraq until ...

References

External links

Ethnic Cleansing and the Kurds

in German {{DEFAULTSORT:Barzanji, Mahmud 1878 births 1956 deaths People from Sulaymaniyah Iraqi Kurdistani politicians Kurdish people from the Ottoman Empire Iraqi Kurdish people Kurdish rulers Kingdom of Kurdistan Kurdish nationalists Kurdish revolutionaries Burials in Iraq Iraqi exiles Iraqi expatriates in India Iraqi revolt of 1920