Macedonian culture (ethnic group) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Macedonians ( mk, Македонци, Makedonci) are a

The first expressions of Macedonian nationalism occurred in the second half of the 19th century mainly among intellectuals in Belgrade, Sofia, Thessaloniki and St. Petersburg. Since the 1850s some Slavic intellectuals from the area adopted the Greek designation ''Macedonian'' as a regional label, and it began to gain popularity.Roumen Daskalov, Tchavdar Marinov, Entangled Histories of the Balkans, Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies, BRILL, 2013, , pp. 283–285. In the 1860s, according to Petko Slaveykov, some young intellectuals from Macedonia were claiming that they are not Bulgarians, but rather Macedonians, descendants of the Ancient Macedonians. Slaveikov, himself with Macedonian roots, started in 1866 the publication of the newspaper ''Makedoniya (Bulgarian newspaper), Makedoniya''. Its main task was "to educate these misguided [sic] ''Grecomans'' there", who he called also ''Macedonism, Macedonists''. In a letter written to the Bulgarian Exarch in February 1874 Petko Slaveykov reports that discontent with the current situation "has given birth among local patriots to the disastrous idea of working independently on the advancement of their Macedonian dialects, own local dialect and what's more, of their own, separate Macedonian church leadership." The activities of these people were also registered by the Serbian politician Stojan Novaković, who promoted the idea to use the Macedonian nationalism in order to oppose the strong pro-Bulgarian sentiments in the area. The nascent Macedonian nationalism, illegal at home in the theocratic Ottoman Empire, and illegitimate internationally, waged a precarious struggle for survival against overwhelming odds: in appearance against the Ottoman Empire, but in fact against the three expansionist Balkan states and their respective patrons among the great powers.

The first known author that overtly speaks of a Macedonian nationality and language was Georgi Pulevski, who in 1875 published in Belgrade a ''Dictionary of Three languages: Macedonian, Albanian, Turkish'', in which he wrote that the Macedonians are a separate nation and the place which is theirs is called Macedonia. In 1880, he published in Sofia a ''Grammar of the language of the Slavic Macedonian population'', a work that is today known as the first attempt at a grammar of Macedonian. However, per some authors, his Macedonian self-identification was inchoate and resembled a regional phenomenon. In 1885 Theodosius of Skopje, a priest who have hold a high-ranking positions within the Bulgarian Exarchate was chosen as a bishop of the episcopacy of Skopje. In 1890 he renounced de facto the Bulgarian Exarchate and attempted to restore the Orthodox Archbishopric of Ohrid (ancient), Archbishopric of Ohrid as a separate Macedonian Orthodox Church in all eparchies of Macedonia, responsible for the spiritual, cultural and educational life of all Macedonian Orthodox Christians. During this time period Metropolitan Bishop Theodosius of Skopje made a plea to the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinople to allow a separate Macedonian church, and ultimately on 4 December 1891 he sent a s:Translation:Theodosius, the metropolitan of Skopje, to Pope Leo XIII, letter to the Pope Leo XIII to ask for a s:Translation:The conditions of transfer of Macedonian eparchies to Union with the Roman Catholic Church, recognition and a s:Translation:Bishop Augusto Bonetti on the talks with Theodosius, the Metropolitan of Skopje, protection from the Roman Catholic Church, but failed. Soon after, he repented and returned to pro-Bulgarian positions. In the 1880s and 1890s, Isaija Mažovski designated Macedonian Slavs as "Macedonians" and "Old Slavic Macedonian people", and also distinguished them from Bulgarians as follows: "Slavic-Bulgarian" for Mažovski was synonymous with "Macedonian", while only "Bulgarian" was a designation for the Bulgarians in Bulgaria.

In 1890, Austrian researcher of Macedonia Karl Hron reported that the Macedonians constituted a separate ethnic group by history and language. Within the next few years, this concept was also welcomed in Russia by linguists including :et:Gotthilf Leonhard Masing, Leonhard Masing, Pyotr Lavrov, Jan Baudouin de Courtenay, and Pyotr Draganov. Draganov, of Bulgarian descent, conducted research in Macedonia and determined that the local language had its own identifying characteristics compared to Bulgarian and Serbian. He wrote in a Saint Petersburg newspaper that the Macedonians should be recognized by Russia in a full national sense.

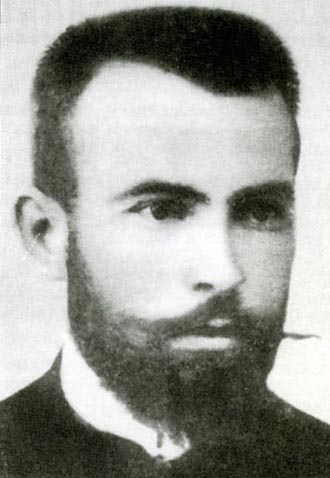

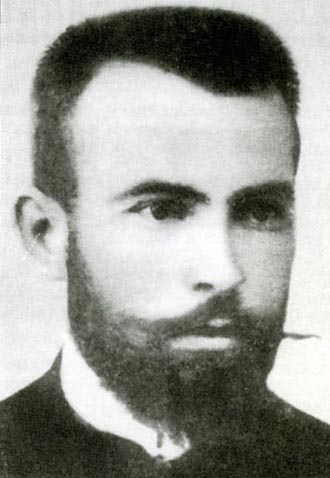

Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization leader Boris Sarafov in 1901 stated that Macedonians had a unique "national element" and, the following year, he stated "We the Macedonians are neither Serbs nor Bulgarians, but simply Macedonians... Macedonia exists only for the Macedonians." However after the failure of the Ilinden Uprising, Sarafov wanted to keep closer ties with Bulgaria, supporting the Bulgarian aspirations towards the area. Gyorche Petrov, another IMRO member, stated Macedonia was a "distinct moral unit" with its own "aspirations", while describing its Slavic population as Bulgarian.

The first expressions of Macedonian nationalism occurred in the second half of the 19th century mainly among intellectuals in Belgrade, Sofia, Thessaloniki and St. Petersburg. Since the 1850s some Slavic intellectuals from the area adopted the Greek designation ''Macedonian'' as a regional label, and it began to gain popularity.Roumen Daskalov, Tchavdar Marinov, Entangled Histories of the Balkans, Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies, BRILL, 2013, , pp. 283–285. In the 1860s, according to Petko Slaveykov, some young intellectuals from Macedonia were claiming that they are not Bulgarians, but rather Macedonians, descendants of the Ancient Macedonians. Slaveikov, himself with Macedonian roots, started in 1866 the publication of the newspaper ''Makedoniya (Bulgarian newspaper), Makedoniya''. Its main task was "to educate these misguided [sic] ''Grecomans'' there", who he called also ''Macedonism, Macedonists''. In a letter written to the Bulgarian Exarch in February 1874 Petko Slaveykov reports that discontent with the current situation "has given birth among local patriots to the disastrous idea of working independently on the advancement of their Macedonian dialects, own local dialect and what's more, of their own, separate Macedonian church leadership." The activities of these people were also registered by the Serbian politician Stojan Novaković, who promoted the idea to use the Macedonian nationalism in order to oppose the strong pro-Bulgarian sentiments in the area. The nascent Macedonian nationalism, illegal at home in the theocratic Ottoman Empire, and illegitimate internationally, waged a precarious struggle for survival against overwhelming odds: in appearance against the Ottoman Empire, but in fact against the three expansionist Balkan states and their respective patrons among the great powers.

The first known author that overtly speaks of a Macedonian nationality and language was Georgi Pulevski, who in 1875 published in Belgrade a ''Dictionary of Three languages: Macedonian, Albanian, Turkish'', in which he wrote that the Macedonians are a separate nation and the place which is theirs is called Macedonia. In 1880, he published in Sofia a ''Grammar of the language of the Slavic Macedonian population'', a work that is today known as the first attempt at a grammar of Macedonian. However, per some authors, his Macedonian self-identification was inchoate and resembled a regional phenomenon. In 1885 Theodosius of Skopje, a priest who have hold a high-ranking positions within the Bulgarian Exarchate was chosen as a bishop of the episcopacy of Skopje. In 1890 he renounced de facto the Bulgarian Exarchate and attempted to restore the Orthodox Archbishopric of Ohrid (ancient), Archbishopric of Ohrid as a separate Macedonian Orthodox Church in all eparchies of Macedonia, responsible for the spiritual, cultural and educational life of all Macedonian Orthodox Christians. During this time period Metropolitan Bishop Theodosius of Skopje made a plea to the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinople to allow a separate Macedonian church, and ultimately on 4 December 1891 he sent a s:Translation:Theodosius, the metropolitan of Skopje, to Pope Leo XIII, letter to the Pope Leo XIII to ask for a s:Translation:The conditions of transfer of Macedonian eparchies to Union with the Roman Catholic Church, recognition and a s:Translation:Bishop Augusto Bonetti on the talks with Theodosius, the Metropolitan of Skopje, protection from the Roman Catholic Church, but failed. Soon after, he repented and returned to pro-Bulgarian positions. In the 1880s and 1890s, Isaija Mažovski designated Macedonian Slavs as "Macedonians" and "Old Slavic Macedonian people", and also distinguished them from Bulgarians as follows: "Slavic-Bulgarian" for Mažovski was synonymous with "Macedonian", while only "Bulgarian" was a designation for the Bulgarians in Bulgaria.

In 1890, Austrian researcher of Macedonia Karl Hron reported that the Macedonians constituted a separate ethnic group by history and language. Within the next few years, this concept was also welcomed in Russia by linguists including :et:Gotthilf Leonhard Masing, Leonhard Masing, Pyotr Lavrov, Jan Baudouin de Courtenay, and Pyotr Draganov. Draganov, of Bulgarian descent, conducted research in Macedonia and determined that the local language had its own identifying characteristics compared to Bulgarian and Serbian. He wrote in a Saint Petersburg newspaper that the Macedonians should be recognized by Russia in a full national sense.

Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization leader Boris Sarafov in 1901 stated that Macedonians had a unique "national element" and, the following year, he stated "We the Macedonians are neither Serbs nor Bulgarians, but simply Macedonians... Macedonia exists only for the Macedonians." However after the failure of the Ilinden Uprising, Sarafov wanted to keep closer ties with Bulgaria, supporting the Bulgarian aspirations towards the area. Gyorche Petrov, another IMRO member, stated Macedonia was a "distinct moral unit" with its own "aspirations", while describing its Slavic population as Bulgarian.

In 1903 Krste Misirkov published in Sofia his book ''On Macedonian Matters'' in which he laid down the principles of the modern Macedonian nationhood and language. This book written in the standardized Dialects of Macedonian, central dialect of Macedonia is considered by ethnic Macedonians as a milestone of the process of Macedonian awakening. Misirkov argued that the dialect of central Macedonia (Veles-Prilep-Bitola-Ohrid) should be taken as a standard Macedonian literary language, in which Macedonians should write, study, and worship; the autocephalous Orthodox Archbishopric of Ohrid (ancient), Archbishopric of Ohrid should be restored; and the Slavic people of Macedonia should be identified in their Ottoman identity cards (''nofuz'') as "Macedonians".

Another major figure of the Macedonian awakening was Dimitrija Čupovski, one of the founders of the Macedonian Literary Society, established in Saint Petersburg in 1902. In 1913, the Macedonian Literary Society submitted the Memorandum of Independence of Macedonia (1913), Memorandum of Independence of Macedonia to the British Foreign Secretary and other European ambassadors, and it was printed in many European newspapers. In the period 1913–1918, Čupovski published the newspaper ''Македонскi Голосъ (Macedonian Voice)'' in which he and fellow members of the Saint Petersburg Macedonian Colony propagated the existence of a Macedonian people separate from the Greeks, Bulgarians and Serbs, and sought to popularize the idea for an independent Macedonian state.

In 1903 Krste Misirkov published in Sofia his book ''On Macedonian Matters'' in which he laid down the principles of the modern Macedonian nationhood and language. This book written in the standardized Dialects of Macedonian, central dialect of Macedonia is considered by ethnic Macedonians as a milestone of the process of Macedonian awakening. Misirkov argued that the dialect of central Macedonia (Veles-Prilep-Bitola-Ohrid) should be taken as a standard Macedonian literary language, in which Macedonians should write, study, and worship; the autocephalous Orthodox Archbishopric of Ohrid (ancient), Archbishopric of Ohrid should be restored; and the Slavic people of Macedonia should be identified in their Ottoman identity cards (''nofuz'') as "Macedonians".

Another major figure of the Macedonian awakening was Dimitrija Čupovski, one of the founders of the Macedonian Literary Society, established in Saint Petersburg in 1902. In 1913, the Macedonian Literary Society submitted the Memorandum of Independence of Macedonia (1913), Memorandum of Independence of Macedonia to the British Foreign Secretary and other European ambassadors, and it was printed in many European newspapers. In the period 1913–1918, Čupovski published the newspaper ''Македонскi Голосъ (Macedonian Voice)'' in which he and fellow members of the Saint Petersburg Macedonian Colony propagated the existence of a Macedonian people separate from the Greeks, Bulgarians and Serbs, and sought to popularize the idea for an independent Macedonian state.

File:Ethnographic map of the central Balkans, ca. 1900.png, Austrian ethnographic map of the vilayets of Kosovo, Saloniki, Scutari, Janina and Monastir, ca. 1900.

File:Cvijic, Jovan - Breisemeister, William A. - Carte ethnographique de la Péninsule balkanique (pd).jpg, Ethnographic map of the Balkans from the Serbian author Jovan Cvijic (1918)

File:Hellenism in the Near East 1918.jpg, Greek map by Georgios Sotiriadis submitted to the Paris Peace Conference (1919)

File:Macedonians coloured on this map from 1922.jpg, Ethnographic map of the Balkans in the ''New Josephus Nelson Larned, Larned History'' (1922)

Cvijić further elaborated the idea that had first appeared in Peucker's map and in his map of 1909 he ingeniously mapped the Macedonian Slavs as a third group distinct from Bulgarians and Serbians, and part of them "under Greek influence". Envisioning a future agreement with Greece, Cvijic depicted the southern half of the Macedo-Slavs "under Greek unfluence", while leaving the rest to appear as a subset of the Serbo-Croats. Cvijić's view was reproduced without acknowledgement by Alfred Stead, with no effect on British opinion, but, reflecting the reorientation of Serbian aims towards dividing Macedonia with Greece, Cvijić eliminated the Macedo-Slavs from a subsequent edition of his map. However, in 1913, before the conclusion of the Treaty of Bucharest (1913), Treaty of Bucharest he published his third ethnographic map distinguishing the Macedo-Slavs between Skopje and Salonica from both Bulgarians and Serbo-Croats, on the basis of the transitional character of their dialect per the linguistic researches of Vatroslav Jagić and Aleksandar Belić, and the Serb features of their customs, such as the zadruga. For Cvijić, the Macedo-Slavs were a transitional population, with any sense of nationality they displayed being weak, superficial, externally imposed and temporary. Despite arguing that they should be considered neutral, he postulated their division into Serbs and Bulgarians based on dialectical and cultural features in anticipation of Serbian demands regarding the delimitation of frontiers.

A Balkan committee of experts rejected Cvijić's concept of the Macedo-Slavs in 1914, However, in 1918 Cvijic published a revised version of his map of 1913, which, now included in a work of his modelling French geographers' standards, was taken as impeccable. This map was reproduced in modified form in French and American journals in 1918 and numerous other maps and atlases, including those produced by the Allies of World War I, Allies as the Entente Cordiale, Entente approached victory in the

The consolidation of an international Communist organization (the Comintern) in the 1920s led to some failed attempts by the Communists to use the Macedonian Question as a political weapon. In the 1920 Yugoslav parliamentary elections, 25% of the total Communist vote came from Macedonia, but participation was low (only 55%), mainly because the pro-Bulgarian IMRO organised a boycott against the elections. In the following years, the communists attempted to enlist the pro-IMRO sympathies of the population in their cause. In the context of this attempt, in 1924 the Comintern organized the filed signing of the so-called May Manifesto, in which independence of partitioned Macedonia was required. In 1925 with the help of the Comintern, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (United) was created, composed of former left-wing Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) members. This organization promoted for the first time in 1932 the existence of a separate ethnic Macedonian nation. In 1933 the Communist Party of Greece, in a series of articles published in its official newspaper, the ''Rizospastis'', criticizing Greek minority policy towards Slavic-speakers in Greek Macedonia, recognized the Slavs of the entire region of Macedonia as forming a distinct Macedonian ethnicity and their language as Macedonian. The idea of a Macedonian nation was internationalized and backed by the Comintern which issued in 1934 a Resolution of the Comintern on the Macedonian Question, resolution supporting the development of the entity. This action was attacked by the IMRO, but was supported by the Balkan communists. The Balkan communist parties supported the national consolidation of the ethnic Macedonian people and created Macedonian sections within the parties, headed by prominent IMRO (United) members.

The consolidation of an international Communist organization (the Comintern) in the 1920s led to some failed attempts by the Communists to use the Macedonian Question as a political weapon. In the 1920 Yugoslav parliamentary elections, 25% of the total Communist vote came from Macedonia, but participation was low (only 55%), mainly because the pro-Bulgarian IMRO organised a boycott against the elections. In the following years, the communists attempted to enlist the pro-IMRO sympathies of the population in their cause. In the context of this attempt, in 1924 the Comintern organized the filed signing of the so-called May Manifesto, in which independence of partitioned Macedonia was required. In 1925 with the help of the Comintern, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (United) was created, composed of former left-wing Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) members. This organization promoted for the first time in 1932 the existence of a separate ethnic Macedonian nation. In 1933 the Communist Party of Greece, in a series of articles published in its official newspaper, the ''Rizospastis'', criticizing Greek minority policy towards Slavic-speakers in Greek Macedonia, recognized the Slavs of the entire region of Macedonia as forming a distinct Macedonian ethnicity and their language as Macedonian. The idea of a Macedonian nation was internationalized and backed by the Comintern which issued in 1934 a Resolution of the Comintern on the Macedonian Question, resolution supporting the development of the entity. This action was attacked by the IMRO, but was supported by the Balkan communists. The Balkan communist parties supported the national consolidation of the ethnic Macedonian people and created Macedonian sections within the parties, headed by prominent IMRO (United) members.

The available data indicates that despite the policy of assimilation, pro-Bulgarian sentiments among the Macedonian Slavs in Yugoslavia were still sizable during the interwar period. However, if the Yugoslavs would recognize the Slavic inhabitants of Vardar Macedonia as Bulgarians, it would mean that the area should be part of Bulgaria. Practically in post-World War II Macedonia, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia's state policy of forced Serbianisation was changed with a new one — of Macedonization. The codification of Macedonian and the recognition of the Macedonian nation had the main goal: finally to ban any Bulgarophilia among the Macedonians and to build a new consciousness, based on identification with Yugoslavia. As a result, Yugoslavia introduced again an abrupt ''de-Bulgarization'' of the people in the PR Macedonia, such as it already had conducted in the Vardar Banovina during the Interwar period. Around 100,000 pro-Bulgarian elements were imprisoned for violations of the special ''Law for the Protection of Macedonian National Honour'', and over 1,200 were allegedly killed. In this way generations of students grew up educated in strong anti-Bulgarian sentiment which during the times of Communist Yugoslavia, increased to the level of state policy. Its main agenda was a result from the need to distinguish between the Bulgarians and the new Macedonian nation, because Macedonians could confirm themselves as a separate community with its own history, only through differentiating itself from Bulgaria. This policy has continued in the new Republic of Macedonia after 1990, although with less intensity. Thus, the Bulgarian part of the identity of the Slavic-speaking population in Vardar Macedonia has died out.

The available data indicates that despite the policy of assimilation, pro-Bulgarian sentiments among the Macedonian Slavs in Yugoslavia were still sizable during the interwar period. However, if the Yugoslavs would recognize the Slavic inhabitants of Vardar Macedonia as Bulgarians, it would mean that the area should be part of Bulgaria. Practically in post-World War II Macedonia, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia's state policy of forced Serbianisation was changed with a new one — of Macedonization. The codification of Macedonian and the recognition of the Macedonian nation had the main goal: finally to ban any Bulgarophilia among the Macedonians and to build a new consciousness, based on identification with Yugoslavia. As a result, Yugoslavia introduced again an abrupt ''de-Bulgarization'' of the people in the PR Macedonia, such as it already had conducted in the Vardar Banovina during the Interwar period. Around 100,000 pro-Bulgarian elements were imprisoned for violations of the special ''Law for the Protection of Macedonian National Honour'', and over 1,200 were allegedly killed. In this way generations of students grew up educated in strong anti-Bulgarian sentiment which during the times of Communist Yugoslavia, increased to the level of state policy. Its main agenda was a result from the need to distinguish between the Bulgarians and the new Macedonian nation, because Macedonians could confirm themselves as a separate community with its own history, only through differentiating itself from Bulgaria. This policy has continued in the new Republic of Macedonia after 1990, although with less intensity. Thus, the Bulgarian part of the identity of the Slavic-speaking population in Vardar Macedonia has died out.

Following the collapse of Yugoslavia, the issue of Macedonian identity emerged again. Nationalists and governments alike from neighbouring countries, especially Greece and Bulgaria, espouse the view that the Macedonian ethnicity is a modern, artificial creation. Such views have been seen by Macedonian historians to represent irredentist motives on Macedonian territory. Moreover, some historians point out that ''all'' modern nations are recent, politically motivated constructs based on creation "myths", that the creation of Macedonian identity is "no more or less artificial than any other identity", and that, contrary to the claims of Romantic nationalists, modern, territorially bound and mutually exclusive nation-states have little in common with their preceding large territorial or dynastic medieval empires, and any connection between them is tenuous at best. In any event, irrespective of shifting political affiliations, the Macedonian Slavs shared in the fortunes of the Byzantine commonwealth and the Rum millet and they can claim them as their heritage. Loring Danforth states similarly, the ancient heritage of modern Balkan countries is not "the mutually exclusive property of one specific nation" but "the shared inheritance of all Balkan peoples".

A more radical and uncompromising strand of Macedonian nationalism has recently emerged called "ancient Macedonism", or "Antiquisation". Proponents of this view see modern Macedonians as direct descendants of the ancient Macedonians. This view faces criticism by academics as it is not supported by archaeology or other historical disciplines and also could marginalize the Macedonian identity. Surveys on the effects of the controversial nation-building project Skopje 2014 and on the perceptions of the population of Skopje revealed a high degree of uncertainty regarding the latter's national identity. A supplementary national poll showed that there was a great discrepancy between the population's sentiment and the narrative the state sought to promote.

Additionally, during the last two decades, tens of thousands of citizens of North Macedonia have applied for Bulgarian citizenship. In the period since 2002 some 97,000 acquired it, while ca. 53,000 applied and are still waiting. Bulgaria has a special ethnic dual-citizenship regime which makes a constitutional distinction between ''ethnic Bulgarians'' and ''Bulgarian citizens''. In the case of the Macedonians, merely declaring their national identity as Bulgarian is enough to gain a citizenship. By making the procedure simpler, Bulgaria stimulates more Macedonian citizens (of Slavic origin) to apply for a Bulgarian citizenship. However, many Macedonians who apply for Bulgarian citizenship as ''Bulgarians by origin'', have few ties with Bulgaria. Further, those applying for Bulgarian citizenship usually say they do so to gain access to Member state of the European Union, member states of the European Union rather than to assert Bulgarian identity. This phenomenon is called ''placebo effect, placebo identity''. Some Macedonians view the Bulgarian policy as part of a strategy to destabilize the Macedonian national identity. As a nation engaged in a dispute over its distinctiveness from Bulgarians, Macedonians have always perceived themselves as threatened by their neighbor. Bulgaria insists its neighbor admit the common historical roots of their languages and nations, a view Skopje continues to reject. As a result, Bulgaria blocked the official start of EU accession talks with North Macedonia.

Despite sizable number of Macedonians that have acquired Bulgarian citizenship since 2002 (ca. 9.7% of the Slavic population), only 3,504 citizens of North Macedonia declared themselves as ethnic Bulgarians in the 2021 North Macedonia census, 2021 census (roughly 0.31% from the Slavic population). The Bulgarian side does not accept these results as completely objective, citing as an example the census has counted less than 20,000 people with Bulgarian citizenship in the country, while in fact they are over 100,000.

Following the collapse of Yugoslavia, the issue of Macedonian identity emerged again. Nationalists and governments alike from neighbouring countries, especially Greece and Bulgaria, espouse the view that the Macedonian ethnicity is a modern, artificial creation. Such views have been seen by Macedonian historians to represent irredentist motives on Macedonian territory. Moreover, some historians point out that ''all'' modern nations are recent, politically motivated constructs based on creation "myths", that the creation of Macedonian identity is "no more or less artificial than any other identity", and that, contrary to the claims of Romantic nationalists, modern, territorially bound and mutually exclusive nation-states have little in common with their preceding large territorial or dynastic medieval empires, and any connection between them is tenuous at best. In any event, irrespective of shifting political affiliations, the Macedonian Slavs shared in the fortunes of the Byzantine commonwealth and the Rum millet and they can claim them as their heritage. Loring Danforth states similarly, the ancient heritage of modern Balkan countries is not "the mutually exclusive property of one specific nation" but "the shared inheritance of all Balkan peoples".

A more radical and uncompromising strand of Macedonian nationalism has recently emerged called "ancient Macedonism", or "Antiquisation". Proponents of this view see modern Macedonians as direct descendants of the ancient Macedonians. This view faces criticism by academics as it is not supported by archaeology or other historical disciplines and also could marginalize the Macedonian identity. Surveys on the effects of the controversial nation-building project Skopje 2014 and on the perceptions of the population of Skopje revealed a high degree of uncertainty regarding the latter's national identity. A supplementary national poll showed that there was a great discrepancy between the population's sentiment and the narrative the state sought to promote.

Additionally, during the last two decades, tens of thousands of citizens of North Macedonia have applied for Bulgarian citizenship. In the period since 2002 some 97,000 acquired it, while ca. 53,000 applied and are still waiting. Bulgaria has a special ethnic dual-citizenship regime which makes a constitutional distinction between ''ethnic Bulgarians'' and ''Bulgarian citizens''. In the case of the Macedonians, merely declaring their national identity as Bulgarian is enough to gain a citizenship. By making the procedure simpler, Bulgaria stimulates more Macedonian citizens (of Slavic origin) to apply for a Bulgarian citizenship. However, many Macedonians who apply for Bulgarian citizenship as ''Bulgarians by origin'', have few ties with Bulgaria. Further, those applying for Bulgarian citizenship usually say they do so to gain access to Member state of the European Union, member states of the European Union rather than to assert Bulgarian identity. This phenomenon is called ''placebo effect, placebo identity''. Some Macedonians view the Bulgarian policy as part of a strategy to destabilize the Macedonian national identity. As a nation engaged in a dispute over its distinctiveness from Bulgarians, Macedonians have always perceived themselves as threatened by their neighbor. Bulgaria insists its neighbor admit the common historical roots of their languages and nations, a view Skopje continues to reject. As a result, Bulgaria blocked the official start of EU accession talks with North Macedonia.

Despite sizable number of Macedonians that have acquired Bulgarian citizenship since 2002 (ca. 9.7% of the Slavic population), only 3,504 citizens of North Macedonia declared themselves as ethnic Bulgarians in the 2021 North Macedonia census, 2021 census (roughly 0.31% from the Slavic population). The Bulgarian side does not accept these results as completely objective, citing as an example the census has counted less than 20,000 people with Bulgarian citizenship in the country, while in fact they are over 100,000.

Online Etymology Dictionary In the Late Middle Ages the name of Macedonia had different meanings for Western Europeans and for the Balkan people. For the Westerners it denoted the historical territory of the Ancient Macedonia, but for the Balkan Christians, it covered the territories of the former Theme of Macedonia, Byzantine province of Macedonia, situated around modern Turkish Edirne. With the conquest of the Balkans by the Ottomans in the late 14th century, the name of Macedonia disappeared as a geographical designation for several centuries. The name was revived just during the early 19th century, after the foundation of the modern Greece, Greek state with its Western Europe-derived Philhellenism, obsession with Ancient Greece. As a result of the rise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire, massive Greek Megali Idea, religious and school propaganda occurred, and a process of ''Hellenization'' was implemented among Slavic-speaking population of the area. In this way, the name ''Macedonians'' was applied to the local Slavs, aiming to stimulate the development of Grecoman, close ties between them and the Greeks, linking both sides to the ancient Macedonians, as a counteract against the growing National awakening of Bulgaria, Bulgarian cultural influence into the region. Although the local intellectuals initially rejected the Macedonian designation as Greek, since 1850s some of them, adopted it as a regional identity, and this name began to gain popularity. Serbian politics then, also encouraged this kind of Regionalism (politics), regionalism to neutralize the Bulgarian influx, thereby promoting Serbian interests there. The local educator Kuzman Shapkarev concluded that since the 1870s this foreign ethnonym began to replace the traditional one ''Bulgarians''.In a letter to Prof. Marin Drinov of May 25, 1888 Kuzman Shapkarev writes: "But even stranger is the name Macedonians, which was imposed on us only 10–15 years ago by outsiders, and not as some think by our own intellectuals.... Yet the people in Macedonia know nothing of that ancient name, reintroduced today with a cunning aim on the one hand and a stupid one on the other. They know the older word: "Bugari", although mispronounced: they have even adopted it as peculiarly theirs, inapplicable to other Bulgarians. You can find more about this in the introduction to the booklets I am sending you. They call their own Macedono-Bulgarian dialect the "Bugarski language", while the rest of the Bulgarian dialects they refer to as the "Shopski language". (Makedonski pregled, IX, 2, 1934, p. 55; the original letter is kept in the Marin Drinov Museum in Sofia, and it is available for examination and study) At the dawn of the 20th century the Bulgarian teacher Vasil Kanchov marked that the local Bulgarians and Koutsovlachs call themselves Macedonians, and the surrounding people also call them in the same way. During the interbellum Bulgaria also supported to some extent the Macedonian ''regional identity'', especially in Yugoslavia. Its aim was to prevent the Serbianization of the local Slavic speakers, because the very name ''Macedonia'' was prohibited in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Ultimately the designation Macedonian, changed its status in 1944, and went from being predominantly a regional, ethnographic denomination, to a national one.

2002 census

. Smaller numbers live in eastern Albania, northern Greece, and southern Serbia, mostly abutting the border areas of the North Macedonia, Republic of North Macedonia. A large number of Macedonians have immigrated overseas to Australia, the United States, Canada, New Zealand and to many European countries: Germany, Italy, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Austria among others.

Macedonian sources generally claim the number of ethnic Macedonians living in Greece at somewhere between 200,000 and 350,000. The ethnic Macedonians in Greece have faced difficulties from the Greek government in their ability to self-declare as members of a ''"Macedonian minority"'' and to refer to their native language as ''"Macedonian"''. Since the late 1980s there has been an ethnic Macedonian revival in Northern Greece, mostly centering on the region of Florina. Since then ethnic Macedonian organisations including the Rainbow (Greece), Rainbow political party have been established. ''Rainbow'' first opened its offices in Florina on 6 September 1995. The following day, the offices had been broken into and had been ransacked. Later Members of ''Rainbow'' had been charged for "causing and inciting mutual hatred among the citizens" because the party had bilingual signs written in both Greek language, Greek and Macedonian. On 20 October 2005, the European Convention on Human Rights, European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) ordered the Greek government to pay penalties to the ''Rainbow Party'' for violations of 2 ECHR articles. ''Rainbow'' has seen limited success at a national level, its best result being achieved in the 1994 European elections, with a total of 7,263 votes. Since 2004 it has participated in European Parliament elections and local elections, but not in national elections. A few of its members have been elected in local administrative posts. ''Rainbow'' has recently re-established ''Nova Zora'', a newspaper that was first published for a short period in the mid-1990s, with reportedly 20,000 copies being distributed free of charge.

here

. In the same report Macedonian nationalists (Popov et al., 1989) claimed that 200,000 ethnic Macedonians live in Bulgaria. However, ''Bulgarian Helsinki Committee'' stated that the vast majority of the Slavic-speaking population in Pirin Macedonia has a Bulgarian national self-consciousness and a Macedonian Bulgarians, regional Macedonian identity similar to the Macedonian regional identity in Greek Macedonia. Finally, according to personal evaluation of a leading local ethnic Macedonian political activist, Stoyko Stoykov, the number of Bulgarian citizens with ethnic Macedonian self-consciousness in 2009 was between 5,000 and 10,000. In 2000, the Bulgarian Constitutional Court banned UMO Ilinden-Pirin, a small Macedonian political party, as a separatist organization. Subsequently, activists attempted to re-establish the party but could not gather the required number of signatures.

File:Map of the majority ethnic groups of Macedonia by municipality.svg, Macedonians in North Macedonia, according to the 2002 census

File:Macedonians in Serbia.png, Concentration of Macedonians in Serbia

File:MalaPrespaiGoloBrdo.png, Regions where Macedonians live within Albania

File:Torbesija.png, Macedonian Muslims in North Macedonia

Significant Macedonian communities can also be found in the traditional immigrant-receiving nations, as well as in Western European countries. Census data in many European countries (such as Italy and Germany) does not take into account the ethnicity of émigrés from the Republic of North Macedonia.

Significant Macedonian communities can also be found in the traditional immigrant-receiving nations, as well as in Western European countries. Census data in many European countries (such as Italy and Germany) does not take into account the ethnicity of émigrés from the Republic of North Macedonia.

2001

. The main Macedonian communities are found in Melbourne, Geelong, Sydney, Wollongong, Newcastle, New South Wales, Newcastle, Canberra and Perth, Western Australia, Perth. The 2006 census recorded 83,983 people of Macedonian ancestry and the 2011 census recorded 93,570 people of Macedonian ancestry.

2004

. The Macedonian community is located mainly in Michigan, New York, Ohio, Indiana and New Jersey

2001

.

Foreign Citizens in Italy

.

The typical Macedonian village house is influenced by Ottoman architecture, Ottoman Architecture. Presented as a construction with two floors, with a hard facade composed of large stones and a wide balcony on the second floor. In villages with predominantly agricultural economy, the first floor was often used as a storage for the harvest, while in some villages the first floor was used as a cattle-pen.

The stereotype for a traditional Macedonian city house is a two-floor building with white façade, with a forward extended second floor, and black wooden elements around the windows and on the edges.

The typical Macedonian village house is influenced by Ottoman architecture, Ottoman Architecture. Presented as a construction with two floors, with a hard facade composed of large stones and a wide balcony on the second floor. In villages with predominantly agricultural economy, the first floor was often used as a storage for the harvest, while in some villages the first floor was used as a cattle-pen.

The stereotype for a traditional Macedonian city house is a two-floor building with white façade, with a forward extended second floor, and black wooden elements around the windows and on the edges.

Most Macedonians are members of the Macedonian Orthodox Church – Ohrid Archbishopric, Macedonian Orthodox Church. The official name of the church is Macedonian Orthodox Church – Ohrid Archbishopric and is the body of Christians who are united under the Archbishop of Ohrid and North Macedonia, exercising jurisdiction over Macedonian Orthodox Christians in the Republic of North Macedonia and in exarchates in the Macedonian diaspora.

The church gained autonomy from the Serbian Orthodox Church in 1959 and declared the restoration of the historic Orthodox Archbishopric of Ohrid (ancient), Archbishopric of Ohrid. On 19 July 1967, the Macedonian Orthodox Church declared autocephaly from the Serbian church. Due to protest from the Serbian Orthodox Church, the move was not recognised by any of the churches of the Eastern Orthodox Communion, and since then, the Macedonian Orthodox Church is not in communion with any Orthodox Church. A small number of Macedonians belong to the Roman Catholic and the Protestant Church, Protestant churches.

Between the 15th and the 20th centuries, during Ottoman Empire, Ottoman rule, a number of Orthodox Macedonian Slavs converted to Islam. Today in the Republic of North Macedonia, they are regarded as Macedonian Muslims, who constitute the second largest religious community of the country.

Most Macedonians are members of the Macedonian Orthodox Church – Ohrid Archbishopric, Macedonian Orthodox Church. The official name of the church is Macedonian Orthodox Church – Ohrid Archbishopric and is the body of Christians who are united under the Archbishop of Ohrid and North Macedonia, exercising jurisdiction over Macedonian Orthodox Christians in the Republic of North Macedonia and in exarchates in the Macedonian diaspora.

The church gained autonomy from the Serbian Orthodox Church in 1959 and declared the restoration of the historic Orthodox Archbishopric of Ohrid (ancient), Archbishopric of Ohrid. On 19 July 1967, the Macedonian Orthodox Church declared autocephaly from the Serbian church. Due to protest from the Serbian Orthodox Church, the move was not recognised by any of the churches of the Eastern Orthodox Communion, and since then, the Macedonian Orthodox Church is not in communion with any Orthodox Church. A small number of Macedonians belong to the Roman Catholic and the Protestant Church, Protestant churches.

Between the 15th and the 20th centuries, during Ottoman Empire, Ottoman rule, a number of Orthodox Macedonian Slavs converted to Islam. Today in the Republic of North Macedonia, they are regarded as Macedonian Muslims, who constitute the second largest religious community of the country.

* Vergina Flag (North Macedonia), Vergina Sun: (official flag, 1992–1995) The Vergina Sun is used unofficially by various associations and cultural groups in the Macedonian diaspora. The Vergina Sun is believed to have been associated with Greeks, ancient Greek kings such as Alexander the Great and Philip II of Macedon, Philip II, although it was used as an ornamental design in ancient Greek art long before the Macedonian period. The symbol was depicted on a golden larnax found in a 4th-century BC royal tomb belonging to either Philip II or Philip III of Macedon in the Greece, Greek region of Macedonia (Greece), Macedonia. The Greeks regard the use of the symbol by North Macedonia as a misappropriation of a Greece, Hellenic symbol, unrelated to Slavic cultures, and a direct claim on the legacy of Philip II. However, archaeological items depicting the symbol have also been excavated in the territory of

* Vergina Flag (North Macedonia), Vergina Sun: (official flag, 1992–1995) The Vergina Sun is used unofficially by various associations and cultural groups in the Macedonian diaspora. The Vergina Sun is believed to have been associated with Greeks, ancient Greek kings such as Alexander the Great and Philip II of Macedon, Philip II, although it was used as an ornamental design in ancient Greek art long before the Macedonian period. The symbol was depicted on a golden larnax found in a 4th-century BC royal tomb belonging to either Philip II or Philip III of Macedon in the Greece, Greek region of Macedonia (Greece), Macedonia. The Greeks regard the use of the symbol by North Macedonia as a misappropriation of a Greece, Hellenic symbol, unrelated to Slavic cultures, and a direct claim on the legacy of Philip II. However, archaeological items depicting the symbol have also been excavated in the territory of

New Balkan Politics – Journal of Politics

Macedonians in the UK

United Macedonian Diaspora

World Macedonian Congress

House of Immigrants

{{DEFAULTSORT:Macedonians (Ethnic Group) Ethnic Macedonian people, Ethnic groups in Albania Ethnic groups in Greece Ethnic groups in Macedonia (region) Ethnic groups in Serbia Ethnic groups in North Macedonia Slavic ethnic groups South Slavs

nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective Identity (social science), identity of a group of people unde ...

and a South Slavic ethnic group native to the region of Macedonia in Southeast Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe (SEE) is a geographical subregion of Europe, consisting primarily of the Balkans. Sovereign states and territories that are included in the region are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia (a ...

. They speak Macedonian, a South Slavic language

The South Slavic languages are one of three branches of the Slavic languages. There are approximately 30 million speakers, mainly in the Balkans. These are separated geographically from speakers of the other two Slavic branches (West and East) ...

. The large majority of Macedonians identify as Eastern Orthodox Christians

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or "canonical") ...

, who speak a South Slavic language

The South Slavic languages are one of three branches of the Slavic languages. There are approximately 30 million speakers, mainly in the Balkans. These are separated geographically from speakers of the other two Slavic branches (West and East) ...

, and share a cultural and historical "Orthodox Byzantine–Slavic heritage" with their neighbours. About two-thirds of all ethnic Macedonians live in North Macedonia

North Macedonia, ; sq, Maqedonia e Veriut, (Macedonia before February 2019), officially the Republic of North Macedonia,, is a country in Southeast Europe. It gained independence in 1991 as one of the successor states of Yugoslavia. It ...

and there are also communities in a number of other countries.

The concept of a Macedonian ethnicity, distinct from their Orthodox Balkan neighbours, is seen to be a comparatively newly emergent one. The earliest manifestations of an incipient Macedonian identity emerged during the second half of the 19th century among limited circles of Slavic-speaking intellectuals, predominantly outside the region of Macedonia. They arose after the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and especially during 1930s, and thus were consolidated by Communist Yugoslavia's governmental policy after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

.

The formation of the ethnic Macedonians as a separate community has been shaped by population displacement

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, ...

as well as by language shift

Language shift, also known as language transfer or language replacement or language assimilation, is the process whereby a speech community shifts to a different language, usually over an extended period of time. Often, languages that are percei ...

, both the result of the political developments in the region of Macedonia during the 20th century. Following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the decisive point in the ethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is "the formation and development of an ethnic group".

This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th century neologism that was later introd ...

of the South Slavic ethnic group was the creation of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia after World War II, a state in the framework of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yu ...

. This was followed by the development of a separate Macedonian language and national literature, and the foundation of a distinct Macedonian Orthodox Church

The Macedonian Orthodox Church – Archdiocese of Ohrid (MOC-AO; mk, Македонска православна црква – Охридска архиепископија), or simply the Macedonian Orthodox Church (MOC) or the Archdiocese o ...

and national historiography.

History

Ancient and Roman period

In antiquity, much of central-northern Macedonia (the Vardar basin) was inhabited byPaionians

Paeonians were an ancient Indo-European people that dwelt in Paeonia. Paeonia was an old country whose location was to the north of Ancient Macedonia, to the south of Dardania, to the west of Thrace and to the east of Illyria, most of their lan ...

who expanded from the lower Strymon basin. The Pelagonian plain was inhabited by the Pelagones and the Lyncestae, ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

tribes of Upper Macedonia; whilst the western region (Ohrid-Prespa) was said to have been inhabited by Illyrian tribes, such as the Enchelae. During the late Classical Period, having already developed several sophisticated ''polis

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

''-type settlements and a thriving economy based on mining, Paeonia became a constituent province of the Argead – Macedonian kingdom. In 310 BC, the Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

attacked deep into the south, subduing various local tribes, such as the Dardani

The Dardani (; grc, Δαρδάνιοι, Δάρδανοι; la, Dardani) or Dardanians were a Paleo-Balkan people, who lived in a region that was named Dardania after their settlement there. They were among the oldest Balkan peoples, and their ...

ans, the Paeonians and the Triballi

The Triballi ( grc, Τριβαλλοί, Triballoí, lat, Triballi) were an ancient people who lived in northern Bulgaria in the region of Roman Oescus up to southeastern Serbia, possibly near the territory of the Morava Valley in the late Iron A ...

. Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

conquest brought with it a significant Romanization

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, a ...

of the region. During the Dominate

The Dominate, also known as the late Roman Empire, is the name sometimes given to the " despotic" later phase of imperial government in the ancient Roman Empire. It followed the earlier period known as the "Principate". Until the empire was reuni ...

period, ' barbarian' foederati were settled on Macedonian soil at times; such as the Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

settled by Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

(330s AD) or the (10 year) settlement of Alaric I's Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

.''Macedonia in Late Antiquity'' p. 551. In A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Wiley -Blackwell, 2011 In contrast to 'frontier provinces', Macedonia (north and south) continued to be a flourishing Christian, Roman province in Late Antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

and into the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

.

Medieval period

Linguistically, the South Slavic languages from which Macedonian developed are thought to have expanded in the region during the post-Roman period, although the exact mechanisms of this linguistic expansion remains a matter of scholarly discussion. Traditional historiography has equated these changes with the commencement of raids and 'invasions' ofSclaveni

The ' (in Latin) or ' (various forms in Greek, see below) were early Slavic tribes that raided, invaded and settled the Balkans in the Early Middle Ages and eventually became the progenitors of modern South Slavs. They were mentioned by early Byz ...

and Antes from Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and s ...

and western Ukraine during the 6th and 7th centuries. However, recent anthropological and archaeological perspectives have viewed the appearance of Slavs in Macedonia, and throughout the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

in general, as part of a broad and complex process of transformation of the cultural, political and ethnolinguistic Balkan landscape before the collapse of Roman authority. The exact details and chronology of population shifts remain to be determined. What is beyond dispute is that, in contrast to "barbarian" Bulgaria, northern Macedonia remained Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

in its cultural outlook into the 7th century. Yet at the same time, sources attest numerous Slavic tribes

This is a list of Slavic peoples and Slavic tribes reported in Late Antiquity and in the Middle Ages, that is, before the year AD 1500.

Ancestors

*Proto-Indo-Europeans (Proto-Indo-European speakers)

** Proto-Balto-Slavs (common ancestors of B ...

in the environs of Thessaloniki and further afield, including the Berziti in Pelagonia. Apart from Slavs and late Byzantines, Kuver's "Bulgars" – a mix of Byzantine Greeks, Bulgars and Pannonian Avars – settled the "Keramissian plain" (Pelagonia) around Bitola in the late 7th century. Later pockets of settlers included "Danubian" Bulgars in the 9th century; Vardariotai, Magyars (Vardariotai) and Armenians in the 10th–12th centuries, Cumans and Pechenegs in the 11th–13th centuries, and Transylvanian Saxons, Saxon miners in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Having previously been Byzantine clients, the ''Sklaviniae'' of Macedonia probably switched their allegiance to Bulgaria during the reign of Irene of Athens, Empress Irene, and was gradually incorporated into the Bulgarian Empire before the mid-9th century. Subsequently, the literary and ecclesiastical centre in Ohrid became a second cultural capital of medieval Bulgaria. On the other hand, developments of Glagolitic script, Slavic Orthodox Culture occurred in Byzantine Thessaloniki.

Ottoman period

After the final Ottoman conquest of the Balkans by the Ottomans in the 14/15th century, all Eastern Orthodox Christians were included in a specific ethno-religious community under ''Graeco-Byzantine'' jurisdiction called Rum Millet. Belonging to this religious commonwealth was so important that most of the common people began to identify themselves as ''Christians''. However ethnonyms never disappeared and some form of primary ethnic identity was available. This is confirmed from a Sultan's Firman from 1680 which describes the ethnic groups in the Balkan territories of the Empire as follows: Greeks, Albanians, Serbs, Vlachs and Bulgarians. The rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire in the early 19th century brought opposition to this continued situation. At that time the classical Rum Millet began to degrade. The coordinated actions, carried out by Bulgarian national leaders supported by the majority of the Slavic-speaking population in today Republic of North Macedonia in order to be recognized as a separate ethnic entity, constituted the so-called "Bulgarian Millet", recognized in 1870. At the time of its creation, people living in Vardar Macedonia, were not in the Exarchate. However, as a result of plebiscites held between 1872 and 1875, the Slavic districts in the area voted overwhelmingly (over 2/3) to go over to the new national Church. Referring to the results of the plebiscites, and on the basis of statistical and ethnological indications, the 1876 Conference of Constantinople included most of Macedonia into the Bulgarian ethnic territory. The borders of new Bulgarian state, drawn by the 1878 Treaty of San Stefano, also included Macedonia, but the treaty was never put into effect and the Treaty of Berlin (1878) "returned" Macedonia to the Ottoman Empire. Throughout the Middle Ages and Ottoman rule up until the early 20th century the Slavic-speaking population majority in the region of Macedonia were more commonly referred to (both by themselves and outsiders) as Bulgarians. However, in pre-nationalist times, terms such as "Bulgarian" did not possess a strict ethno-nationalistic meaning, rather, they were loose, often interchangeable terms which could simultaneously denote regional habitation, allegiance to a particular empire, religious orientation, membership in certain social groups. Similarly, a "Byzantine" was a ''Roman'' subject of Constantinople, and the term bore no strict ethnic connotations, Greek or otherwise. Overall, in the Middle Ages, "a person's origin was distinctly regional", and in Ottoman era, before the 19th-century rise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire, rise of nationalism, it was based on the corresponding Millet system, confessional community. After the rise of nationalism, most of the Slavic-speaking population in the area, joined the Bulgarian Millet, Bulgarian community, through voting in its favor on plebiscites held during the 1870s, by a qualified majority (over two-thirds).Identity

The first expressions of Macedonian nationalism occurred in the second half of the 19th century mainly among intellectuals in Belgrade, Sofia, Thessaloniki and St. Petersburg. Since the 1850s some Slavic intellectuals from the area adopted the Greek designation ''Macedonian'' as a regional label, and it began to gain popularity.Roumen Daskalov, Tchavdar Marinov, Entangled Histories of the Balkans, Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies, BRILL, 2013, , pp. 283–285. In the 1860s, according to Petko Slaveykov, some young intellectuals from Macedonia were claiming that they are not Bulgarians, but rather Macedonians, descendants of the Ancient Macedonians. Slaveikov, himself with Macedonian roots, started in 1866 the publication of the newspaper ''Makedoniya (Bulgarian newspaper), Makedoniya''. Its main task was "to educate these misguided [sic] ''Grecomans'' there", who he called also ''Macedonism, Macedonists''. In a letter written to the Bulgarian Exarch in February 1874 Petko Slaveykov reports that discontent with the current situation "has given birth among local patriots to the disastrous idea of working independently on the advancement of their Macedonian dialects, own local dialect and what's more, of their own, separate Macedonian church leadership." The activities of these people were also registered by the Serbian politician Stojan Novaković, who promoted the idea to use the Macedonian nationalism in order to oppose the strong pro-Bulgarian sentiments in the area. The nascent Macedonian nationalism, illegal at home in the theocratic Ottoman Empire, and illegitimate internationally, waged a precarious struggle for survival against overwhelming odds: in appearance against the Ottoman Empire, but in fact against the three expansionist Balkan states and their respective patrons among the great powers.

The first known author that overtly speaks of a Macedonian nationality and language was Georgi Pulevski, who in 1875 published in Belgrade a ''Dictionary of Three languages: Macedonian, Albanian, Turkish'', in which he wrote that the Macedonians are a separate nation and the place which is theirs is called Macedonia. In 1880, he published in Sofia a ''Grammar of the language of the Slavic Macedonian population'', a work that is today known as the first attempt at a grammar of Macedonian. However, per some authors, his Macedonian self-identification was inchoate and resembled a regional phenomenon. In 1885 Theodosius of Skopje, a priest who have hold a high-ranking positions within the Bulgarian Exarchate was chosen as a bishop of the episcopacy of Skopje. In 1890 he renounced de facto the Bulgarian Exarchate and attempted to restore the Orthodox Archbishopric of Ohrid (ancient), Archbishopric of Ohrid as a separate Macedonian Orthodox Church in all eparchies of Macedonia, responsible for the spiritual, cultural and educational life of all Macedonian Orthodox Christians. During this time period Metropolitan Bishop Theodosius of Skopje made a plea to the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinople to allow a separate Macedonian church, and ultimately on 4 December 1891 he sent a s:Translation:Theodosius, the metropolitan of Skopje, to Pope Leo XIII, letter to the Pope Leo XIII to ask for a s:Translation:The conditions of transfer of Macedonian eparchies to Union with the Roman Catholic Church, recognition and a s:Translation:Bishop Augusto Bonetti on the talks with Theodosius, the Metropolitan of Skopje, protection from the Roman Catholic Church, but failed. Soon after, he repented and returned to pro-Bulgarian positions. In the 1880s and 1890s, Isaija Mažovski designated Macedonian Slavs as "Macedonians" and "Old Slavic Macedonian people", and also distinguished them from Bulgarians as follows: "Slavic-Bulgarian" for Mažovski was synonymous with "Macedonian", while only "Bulgarian" was a designation for the Bulgarians in Bulgaria.

In 1890, Austrian researcher of Macedonia Karl Hron reported that the Macedonians constituted a separate ethnic group by history and language. Within the next few years, this concept was also welcomed in Russia by linguists including :et:Gotthilf Leonhard Masing, Leonhard Masing, Pyotr Lavrov, Jan Baudouin de Courtenay, and Pyotr Draganov. Draganov, of Bulgarian descent, conducted research in Macedonia and determined that the local language had its own identifying characteristics compared to Bulgarian and Serbian. He wrote in a Saint Petersburg newspaper that the Macedonians should be recognized by Russia in a full national sense.

Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization leader Boris Sarafov in 1901 stated that Macedonians had a unique "national element" and, the following year, he stated "We the Macedonians are neither Serbs nor Bulgarians, but simply Macedonians... Macedonia exists only for the Macedonians." However after the failure of the Ilinden Uprising, Sarafov wanted to keep closer ties with Bulgaria, supporting the Bulgarian aspirations towards the area. Gyorche Petrov, another IMRO member, stated Macedonia was a "distinct moral unit" with its own "aspirations", while describing its Slavic population as Bulgarian.

The first expressions of Macedonian nationalism occurred in the second half of the 19th century mainly among intellectuals in Belgrade, Sofia, Thessaloniki and St. Petersburg. Since the 1850s some Slavic intellectuals from the area adopted the Greek designation ''Macedonian'' as a regional label, and it began to gain popularity.Roumen Daskalov, Tchavdar Marinov, Entangled Histories of the Balkans, Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies, BRILL, 2013, , pp. 283–285. In the 1860s, according to Petko Slaveykov, some young intellectuals from Macedonia were claiming that they are not Bulgarians, but rather Macedonians, descendants of the Ancient Macedonians. Slaveikov, himself with Macedonian roots, started in 1866 the publication of the newspaper ''Makedoniya (Bulgarian newspaper), Makedoniya''. Its main task was "to educate these misguided [sic] ''Grecomans'' there", who he called also ''Macedonism, Macedonists''. In a letter written to the Bulgarian Exarch in February 1874 Petko Slaveykov reports that discontent with the current situation "has given birth among local patriots to the disastrous idea of working independently on the advancement of their Macedonian dialects, own local dialect and what's more, of their own, separate Macedonian church leadership." The activities of these people were also registered by the Serbian politician Stojan Novaković, who promoted the idea to use the Macedonian nationalism in order to oppose the strong pro-Bulgarian sentiments in the area. The nascent Macedonian nationalism, illegal at home in the theocratic Ottoman Empire, and illegitimate internationally, waged a precarious struggle for survival against overwhelming odds: in appearance against the Ottoman Empire, but in fact against the three expansionist Balkan states and their respective patrons among the great powers.

The first known author that overtly speaks of a Macedonian nationality and language was Georgi Pulevski, who in 1875 published in Belgrade a ''Dictionary of Three languages: Macedonian, Albanian, Turkish'', in which he wrote that the Macedonians are a separate nation and the place which is theirs is called Macedonia. In 1880, he published in Sofia a ''Grammar of the language of the Slavic Macedonian population'', a work that is today known as the first attempt at a grammar of Macedonian. However, per some authors, his Macedonian self-identification was inchoate and resembled a regional phenomenon. In 1885 Theodosius of Skopje, a priest who have hold a high-ranking positions within the Bulgarian Exarchate was chosen as a bishop of the episcopacy of Skopje. In 1890 he renounced de facto the Bulgarian Exarchate and attempted to restore the Orthodox Archbishopric of Ohrid (ancient), Archbishopric of Ohrid as a separate Macedonian Orthodox Church in all eparchies of Macedonia, responsible for the spiritual, cultural and educational life of all Macedonian Orthodox Christians. During this time period Metropolitan Bishop Theodosius of Skopje made a plea to the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinople to allow a separate Macedonian church, and ultimately on 4 December 1891 he sent a s:Translation:Theodosius, the metropolitan of Skopje, to Pope Leo XIII, letter to the Pope Leo XIII to ask for a s:Translation:The conditions of transfer of Macedonian eparchies to Union with the Roman Catholic Church, recognition and a s:Translation:Bishop Augusto Bonetti on the talks with Theodosius, the Metropolitan of Skopje, protection from the Roman Catholic Church, but failed. Soon after, he repented and returned to pro-Bulgarian positions. In the 1880s and 1890s, Isaija Mažovski designated Macedonian Slavs as "Macedonians" and "Old Slavic Macedonian people", and also distinguished them from Bulgarians as follows: "Slavic-Bulgarian" for Mažovski was synonymous with "Macedonian", while only "Bulgarian" was a designation for the Bulgarians in Bulgaria.

In 1890, Austrian researcher of Macedonia Karl Hron reported that the Macedonians constituted a separate ethnic group by history and language. Within the next few years, this concept was also welcomed in Russia by linguists including :et:Gotthilf Leonhard Masing, Leonhard Masing, Pyotr Lavrov, Jan Baudouin de Courtenay, and Pyotr Draganov. Draganov, of Bulgarian descent, conducted research in Macedonia and determined that the local language had its own identifying characteristics compared to Bulgarian and Serbian. He wrote in a Saint Petersburg newspaper that the Macedonians should be recognized by Russia in a full national sense.

Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization leader Boris Sarafov in 1901 stated that Macedonians had a unique "national element" and, the following year, he stated "We the Macedonians are neither Serbs nor Bulgarians, but simply Macedonians... Macedonia exists only for the Macedonians." However after the failure of the Ilinden Uprising, Sarafov wanted to keep closer ties with Bulgaria, supporting the Bulgarian aspirations towards the area. Gyorche Petrov, another IMRO member, stated Macedonia was a "distinct moral unit" with its own "aspirations", while describing its Slavic population as Bulgarian.

National antagonisms and Macedonian separatism

Macedonian separatism

In 1903 Krste Misirkov published in Sofia his book ''On Macedonian Matters'' in which he laid down the principles of the modern Macedonian nationhood and language. This book written in the standardized Dialects of Macedonian, central dialect of Macedonia is considered by ethnic Macedonians as a milestone of the process of Macedonian awakening. Misirkov argued that the dialect of central Macedonia (Veles-Prilep-Bitola-Ohrid) should be taken as a standard Macedonian literary language, in which Macedonians should write, study, and worship; the autocephalous Orthodox Archbishopric of Ohrid (ancient), Archbishopric of Ohrid should be restored; and the Slavic people of Macedonia should be identified in their Ottoman identity cards (''nofuz'') as "Macedonians".

Another major figure of the Macedonian awakening was Dimitrija Čupovski, one of the founders of the Macedonian Literary Society, established in Saint Petersburg in 1902. In 1913, the Macedonian Literary Society submitted the Memorandum of Independence of Macedonia (1913), Memorandum of Independence of Macedonia to the British Foreign Secretary and other European ambassadors, and it was printed in many European newspapers. In the period 1913–1918, Čupovski published the newspaper ''Македонскi Голосъ (Macedonian Voice)'' in which he and fellow members of the Saint Petersburg Macedonian Colony propagated the existence of a Macedonian people separate from the Greeks, Bulgarians and Serbs, and sought to popularize the idea for an independent Macedonian state.

In 1903 Krste Misirkov published in Sofia his book ''On Macedonian Matters'' in which he laid down the principles of the modern Macedonian nationhood and language. This book written in the standardized Dialects of Macedonian, central dialect of Macedonia is considered by ethnic Macedonians as a milestone of the process of Macedonian awakening. Misirkov argued that the dialect of central Macedonia (Veles-Prilep-Bitola-Ohrid) should be taken as a standard Macedonian literary language, in which Macedonians should write, study, and worship; the autocephalous Orthodox Archbishopric of Ohrid (ancient), Archbishopric of Ohrid should be restored; and the Slavic people of Macedonia should be identified in their Ottoman identity cards (''nofuz'') as "Macedonians".

Another major figure of the Macedonian awakening was Dimitrija Čupovski, one of the founders of the Macedonian Literary Society, established in Saint Petersburg in 1902. In 1913, the Macedonian Literary Society submitted the Memorandum of Independence of Macedonia (1913), Memorandum of Independence of Macedonia to the British Foreign Secretary and other European ambassadors, and it was printed in many European newspapers. In the period 1913–1918, Čupovski published the newspaper ''Македонскi Голосъ (Macedonian Voice)'' in which he and fellow members of the Saint Petersburg Macedonian Colony propagated the existence of a Macedonian people separate from the Greeks, Bulgarians and Serbs, and sought to popularize the idea for an independent Macedonian state.

The "Macedonian Slavs" in cartography

From 1878 until 1918 most independent European observers viewed the Slavic speakers in Ottoman Macedonia, Slavs of Macedonia as Bulgarians or as Macedonian Slavs, while their association with Bulgaria was almost universally accepted. Original manuscript versions of population data mentioned "Macedonian Slavs", though the term was changed to "Bulgarians" in the official printing. Western publications usually presented the Slavs of Macedonia as Bulgarians, as happened, partly for political reasons, in Serbian ones. Prompted by the publication of a Serbian map by Spiridon Gopčević claiming the Slavs of Macedonia as Serbs, a version of a Russian map, published in 1891, in a period of deterioration of Bulgaria–Russia relations, Bulgarian-Russian relations, first presented Macedonia inhabited not by Bulgarians, but by Macedonian Slavs. Austrian-Hungarian maps followed suit in an effort to delegitimize the ambitions of Russophile Bulgaria, returning to presenting the Macedonian Slavs as Bulgarians when Austria-Bulgaria relations ameliorated, only to renege and employ the designation "Macedonian Slavs" when Bulgaria changed its foreign policy and Austria turned to envisaging an autonomous Macedonia under Austrian influence within the Murzsteg Agreement, Murzsteg process. The term "Macedonian Slavs" was used either as a middle solution between conflicting Serbian and Bulgarian claims, to denote an intermediary grouping of Slavs, associated with the Bulgarians, or to describe a separate Slavic group with no ethnic, national or political affiliation. The differentiation of ethnographic maps representing rival national views produced to satisfy the curiosity of European audience for the inhabitants of Macedonia, after the Ilinden uprising of 1903, indicated the complexity of the issue. Influenced by the conclusions of the research of young Serb Jovan Cvijić, that Macedonia's culture combined Byzantine culture, Byzantine influence with Serbian traditions, a map of 1903 by Austrian cartographer :de:Karl Peucker, Karl Peucker depicted Macedonia as a peculiar area, where zones of linguistic influence overlapped. In his first ethnographic map of 1906, Cvijic presented all Slavs of Serbia and Macedonia merely as "Slavs". In a pamphlet translated and circulated in Europe the same year, he elaborated his ostensibly impartial views and described the Slavs living south of the Babuna (mountain), Babuna and Plačkovica mountains as "Macedo-Slavs" arguing that the appellation "Bugari" meant simply "peasant" to them, that they had no national consciousness and could become Serbs or Bulgarians in the future. Cvijić thus transformed the political character of the IMRO's appeals to "Macedonians" into an ethnic one. Bulgarian cartographer Anastas Ishirkov countered Cvijić's views, pointing to the involvement of Macedonian Slavs in Bulgarian nationalist uprisings and the Macedonian origins of Bulgarian nationalists before 1878. Although Cvijic's arguments attracted the attention of Great Powers, they did not endorse at the time his view on the Macedo-Slavs.First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, replicated its ideas, especially its depiction of the Macedo-Slavs. The prevalence of the Yugoslavia, Yugoslav point of view, obliged :el:Γεώργιος Σωτηριάδης, Georgios Sotiriades, a professor of History at the University of Athens, to map the Macedo-Slavs as a distinct group in his work of 1918, that mirrored Greek views of the time and was used as an official document to advocate for Greece's positions in the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris peace conference. After World War I, Cvijić's map became the point of reference for all Balkan ethnographic maps, while his concept of Macedo-Slavs was reproduced in almost all maps, including German maps, that acknowledged a Macedonian nation.

Macedonian Nationalism and Interwar Communism