Lucille Clifton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lucille Clifton (June 27, 1936 – February 13, 2010) was an American poet, writer, and educator from Buffalo, New York. From 1979 to 1985 she was Poet Laureate of Maryland. Clifton was a finalist twice for the

webpage o

Maryland State Archives

Retrieved May 27, 2007. From 1982 to 1983, she was visiting writer at the Columbia University School of the Arts and at

"Lucille Clifton"

Maryland Women's Hall of Fame. Retrieved May 28, 2007. She was Distinguished Professor of Humanities at St. Mary's College of Maryland. From 1995 to 1999, she was a visiting professor at

African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund

Lucille Clifton traced her family's roots to the West African kingdom of

Lucille Clifton traced her family's roots to the West African kingdom of

''Past winners & finalists by category''. The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved April 8, 2012. *''Ten Oxherding Pictures'', Santa Cruz: Moving Parts Press, 1988 *''Quilting: Poems 1987–1990'', Brockport: BOA Editions, 1991, *''The Book of Light'', Port Townsend:

* ''Three Wishes'' (Doubleday)

* ''The Boy Who Didn't Believe In Spring'' (Penguin)

* ; Reprint Yearling Books,

* ''The Times They Used To Be'' (Henry Holt & Co)

* ''All Us Come Cross the Water'' (Henry Holt)

* ''My Friend Jacob'' (Dutton)

* ''Amifika'' (Dutton)

* ''Sonora the Beautiful'' (Dutton)

* ''The Black B C's'' (Dutton)

* ''The Palm of My Heart: Poetry by African American Children''. Introduction by Lucille Clifton (San Val)

* ''Three Wishes'' (Doubleday)

* ''The Boy Who Didn't Believe In Spring'' (Penguin)

* ; Reprint Yearling Books,

* ''The Times They Used To Be'' (Henry Holt & Co)

* ''All Us Come Cross the Water'' (Henry Holt)

* ''My Friend Jacob'' (Dutton)

* ''Amifika'' (Dutton)

* ''Sonora the Beautiful'' (Dutton)

* ''The Black B C's'' (Dutton)

* ''The Palm of My Heart: Poetry by African American Children''. Introduction by Lucille Clifton (San Val)

Clifton's Page at BOA Editions

Biography and critical appreciation of her work, and links to poems

at the Poetry Foundation.

for the WGBH series

New Television Workshop

for the WGBH series

New Television Workshop

"Jean Toomer's Cane and the Rise of the Harlem Renaissance"

Essay by Lucille Clifton.

PBS, September 8, 2006. (Audio)

Recorded in Los Angeles, CA, on May 21, 1996

From Lannan (Video 45 mins).

University of Illinois

Profile from Academy of American Poets

* * FBI file on Lucille Clifton {{DEFAULTSORT:Clifton, Lucille 1936 births 2010 deaths 20th-century African-American women 20th-century African-American writers 20th-century American poets 20th-century American women writers 21st-century African-American people 21st-century African-American women African-American history of Maryland African-American poets African-American women writers American people of Beninese descent American women academics American women poets Columbia University faculty Howard University alumni National Book Award winners People with polydactyly Poets from Maryland Poets from New York (state) Poets Laureate of Maryland St. Mary's College of Maryland faculty State University of New York at Fredonia alumni University of California, Santa Cruz faculty Writers from Buffalo, New York Writers from Maryland

Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made ...

for poetry.

Life and career

Lucille Clifton (born Thelma Lucille Sayles, in Depew, New York) grew up in Buffalo, New York, and graduated fromFosdick-Masten Park High School

Fosdick-Masten Park High School, now known as City Honors School, is a historic public high school building located at Buffalo in Erie County, New York. The school is located on a site. It was designed by architects Esenwein & Johnson and is ...

in 1953. She attended Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a Private university, private, University charter#Federal, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, classifie ...

with a scholarship from 1953 to 1955, leaving to study at the State University of New York at Fredonia

The State University of New York at Fredonia (SUNY Fredonia) is a public university in Fredonia, New York, United States. It is the westernmost member of the State University of New York. Founded in 1826, it is the sixty-sixth-oldest institute of ...

(near Buffalo).Holladay, Hilary, ''73 Poems for 73 Years'', James Madison University, September 21, 2010, p. 48.

In 1958, Lucille Sayles married Fred James Clifton, a professor of philosophy at the University at Buffalo

The State University of New York at Buffalo, commonly called the University at Buffalo (UB) and sometimes called SUNY Buffalo, is a public research university with campuses in Buffalo and Amherst, New York. The university was founded in 18 ...

, and a sculptor whose carvings depicted African faces. Lucille and her husband had six children together, and she worked as a claims clerk in the New York State Division of Employment, Buffalo (1958–60), and then as literature assistant in the Office of Education in Washington, D.C. (1960–71). Writer Ishmael Reed

Ishmael Scott Reed (born February 22, 1938) is an American poet, novelist, essayist, songwriter, composer, playwright, editor and publisher known for his satirical works challenging American political culture. Perhaps his best-known work is '' M ...

introduced Lucille to Clifton while he was organizing the Buffalo Community Drama Workshop. Fred and Lucille Clifton starred in the group's version of ''The Glass Menagerie

''The Glass Menagerie'' is a memory play by Tennessee Williams that premiered in 1944 and catapulted Williams from obscurity to fame. The play has strong autobiographical elements, featuring characters based on its author, his Histrionic persona ...

'', which was called "poetic and sensitive" by the ''Buffalo Evening News''.

In 1966, Reed took some of Clifton's poems to Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1901 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. One of the earliest innovators of the literary art form called jazz poetry, H ...

, who included them in his anthology ''The Poetry of the Negro''. In 1967, the Cliftons moved to Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

, Maryland. Her first poetry collection, ''Good Times'', was published in 1969, and listed by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' as one of the year's ten best books. From 1971 to 1974, Clifton was poet-in-residence at Coppin State College

Coppin State University (Coppin) is a public historically black university in Baltimore, Maryland. It is part of the University System of Maryland and a member of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund. In terms of demographics, the Coppin State ...

in Baltimore. From 1979 to 1985, she was Poet Laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch ...

of the state of Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

."Maryland Poets Laureate"webpage o

Maryland State Archives

Retrieved May 27, 2007. From 1982 to 1983, she was visiting writer at the Columbia University School of the Arts and at

George Washington University

, mottoeng = "God is Our Trust"

, established =

, type = Private federally chartered research university

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $2.8 billion (2022)

, presi ...

. In 1984, her husband died of cancer.

From 1985 to 1989, Clifton was a professor of literature and creative writing at the University of California, Santa Cruz

The University of California, Santa Cruz (UC Santa Cruz or UCSC) is a public land-grant research university in Santa Cruz, California. It is one of the ten campuses in the University of California system. Located on Monterey Bay, on the ed ...

.Maryland State Archives and Maryland Commission for Women"Lucille Clifton"

Maryland Women's Hall of Fame. Retrieved May 28, 2007. She was Distinguished Professor of Humanities at St. Mary's College of Maryland. From 1995 to 1999, she was a visiting professor at

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

. In 2006, she was a fellow at Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College (; ) is a private research university in Hanover, New Hampshire. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, it is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution. Although founded to educate Native ...

. She died in Baltimore on February 13, 2010.

In 2019, daughter Sidney Clifton reacquired the family's home near Baltimore, aiming to establish the Clifton House as a place to support young artists and writers through in-person and virtual workshops, classes, seminars, residencies, and a gallery. The Clifton House received preservation funding through the National Trust for Historic Preservation’African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund

Poetic work

Lucille Clifton traced her family's roots to the West African kingdom of

Lucille Clifton traced her family's roots to the West African kingdom of Dahomey

The Kingdom of Dahomey () was a West African kingdom located within present-day Benin that existed from approximately 1600 until 1904. Dahomey developed on the Abomey Plateau amongst the Fon people in the early 17th century and became a region ...

, now the Republic of Benin

Benin ( , ; french: Bénin , ff, Benen), officially the Republic of Benin (french: République du Bénin), and formerly Republic of Dahomey, Dahomey, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burki ...

. Growing up, she was told by her mother, "Be proud, you're from Dahomey women!" She cites as one of her ancestors the first black woman to be "legally hanged" for manslaughter in the state of Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

during the time of Slavery in the United States

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Sla ...

. Girls in her family are born with an extra finger on each hand, a genetic trait known as polydactyly

Polydactyly or polydactylism (), also known as hyperdactyly, is an anomaly in humans and animals resulting in supernumerary fingers and/or toes. Polydactyly is the opposite of oligodactyly (fewer fingers or toes).

Signs and symptoms

In hum ...

. Lucille's two extra fingers were amputated surgically when she was a small child, a common practice at that time for reasons of superstition and social stigma. Her "two ghost fingers" and their activities became a theme in her poetry and other writings. Health problems in her later years included painful gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intens ...

which gave her some difficulty in walking.

Often compared to Emily Dickinson

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry.

Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massac ...

for her short line length and deft rhymes, Clifton wrote poetry that "examine the inner world of her own body", used the body as a "theatre for her poetry". After her uterus was removed, for example, she spoke of her body "as a home without a kitchen".

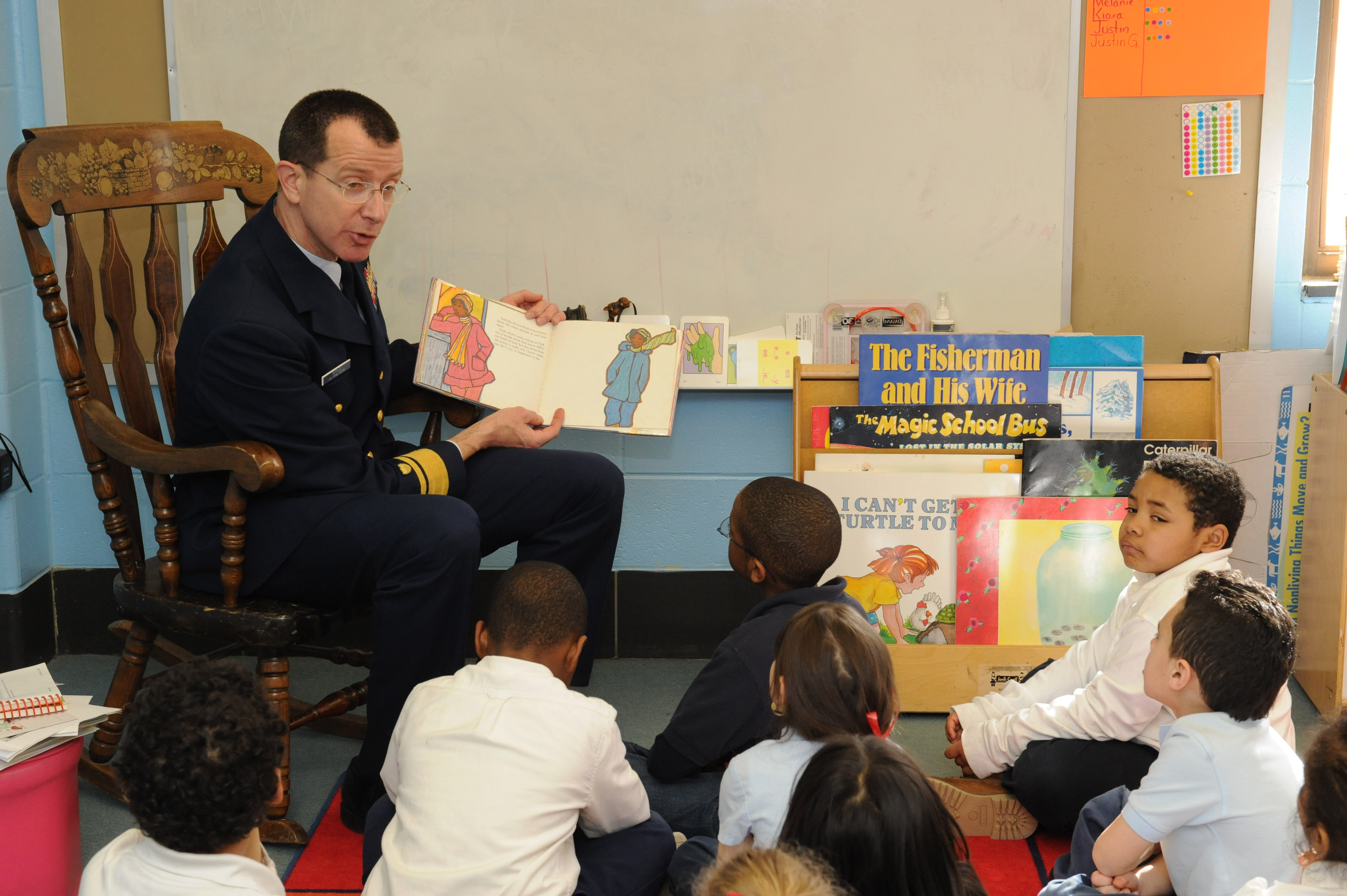

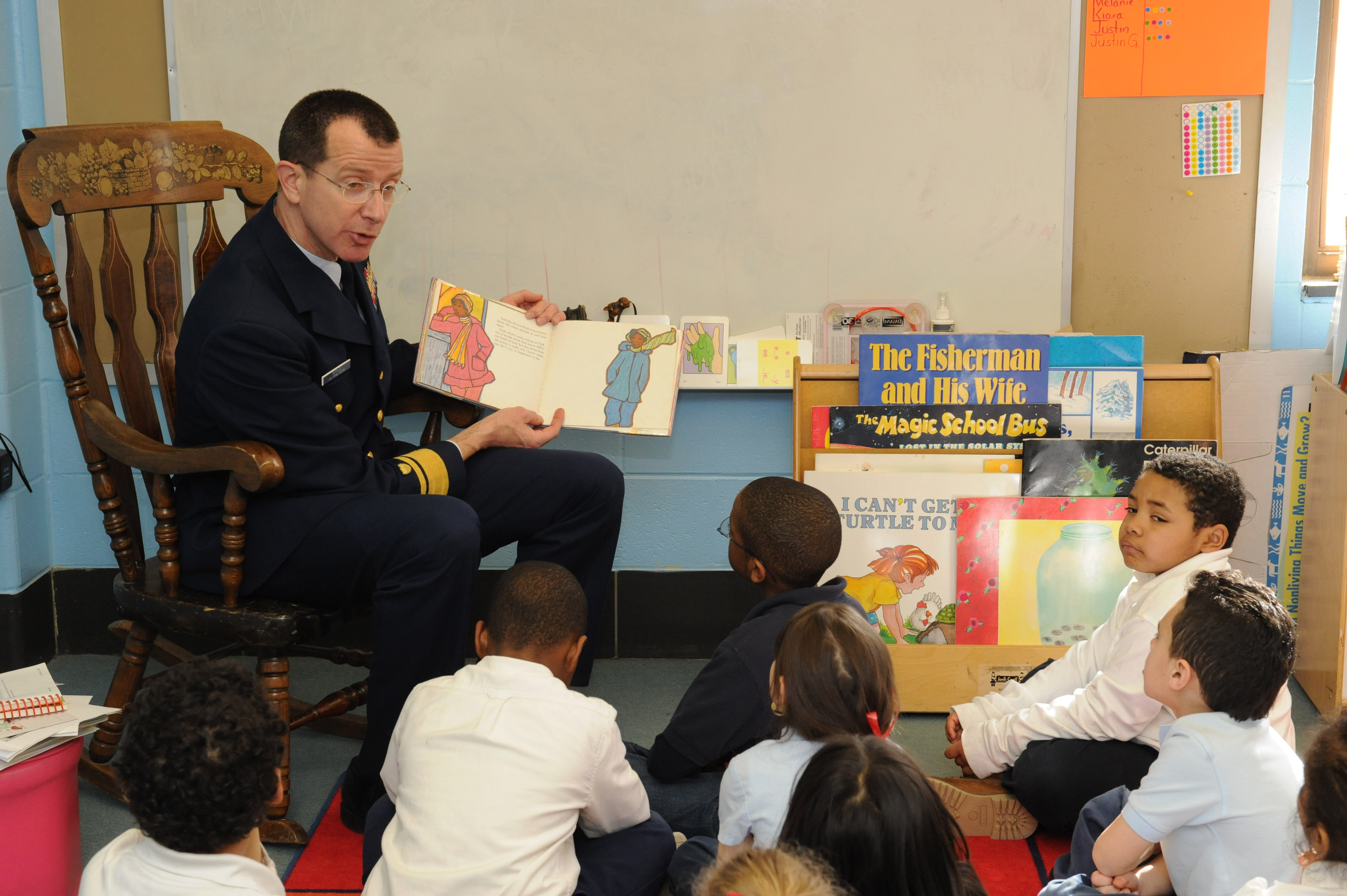

Her series of children's books about a young black boy began with 1970's ''Some of the Days of Everett Anderson.'' Everett Anderson, a recurring character in many of her books, spoke in African American English and dealt with real life social problems.

Clifton's work features in anthologies such as ''My Black Me: A Beginning Book of Black Poetry'' (ed. Arnold Adoff), ''A Poem of Her Own: Voices of American Women Yesterday and Today'' (ed. Catherine Clinton), ''Black Stars: African American Women Writers'' (ed. Brenda Scott Wilkinson), ''Daughters of Africa

''Daughters of Africa: An International Anthology of Words and Writings by Women of African Descent from the Ancient Egyptian to the Present'' is a compilation of orature and literature by more than 200 women from Africa and the African diaspora, ...

'' (ed. Margaret Busby

Margaret Yvonne Busby, , Hon. FRSL (born 1944), also known as Nana Akua Ackon, is a Ghanaian-born publisher, editor, writer and broadcaster, resident in the UK. She was Britain's youngest and first black female book publisherJazzmine Breary"Le ...

), and ''Bedrock: Writers on the Wonders of Geology'' (eds Lauret E. Savoy, Eldridge M. Moores, and Judith E. Moores (Trinity University Press

Trinity University Press is a university press affiliated with Trinity University, which is located in San Antonio, Texas. Trinity University Press was officially founded in 1967 after the university acquired the Illinois-based Principia Press. T ...

). Studies about Clifton's life and writings include ''Wild Blessings: The Poetry of Lucille Clifton'' (LSU Press, 2004) by Hilary Holladay, and ''Lucille Clifton: Her Life and Letters'' (Praeger, 2006) by Mary Jane Lupton.

''Two-Headed Woman'': "homage to my hips"

In 1980 Clifton published "homage to my hips" in her book of poems, ''Two-Headed Woman''. ''Two-Headed Woman'' won the 1980 Juniper Prize and was characterized by its "dramatic tautness, simple language … tributes to blackness, ndcelebrations of women", which are all traits reflected in the poem "homage to my hips". This particular collection of poetry also marks the beginning of Clifton's interest in depicting the "transgressive black body." "homage to my hips" was preceded by the poem "homage to my hair" – and acts as a complementary work that explores the relationship between African-American women and men and aimed to reinvent the negative stereotypes associated with the black female body. "Homage to my hips" and "homage to my hair" both relate the African-American body to mythological powers – a literary technique common among many literary works by African American women. Jane Campbell poses the idea that "the specific effect of mythmaking upon race relations … constitutes a radical act, inviting the audience to subvert the racist mythology that thwarts and defeats Afro-Americans, and to replace it with a new mythology rooted in the black perspective." Therefore, Clifton utilizes "homage to my hips" to celebrate the African-American female body as a source of power, sexuality, pride, and freedom.Awards and recognition

Lucille Clifton received a Creative Writing Fellowships from theNational Endowment for the Arts

The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) is an independent agency of the United States federal government that offers support and funding for projects exhibiting artistic excellence. It was created in 1965 as an independent agency of the federal ...

in 1970 and 1973, and a grant from the Academy of American Poets

The Academy of American Poets is a national, member-supported organization that promotes poets and the art of poetry. The nonprofit organization was incorporated in the state of New York in 1934. It fosters the readership of poetry through outreach ...

. She received the Charity Randall prize, the Jerome J. Shestack Prize from the ''American Poetry Review

''The American Poetry Review'' (''APR'') is an American poetry magazine printed every other month on tabloid-sized newsprint. It was founded in 1972 by Stephen Berg and Stephen Parker in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The magazine's editor is Elizabe ...

'', and an Emmy Award

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the calendar year, each with the ...

. Her children's book ''Everett Anderson's Good-bye'' won the 1984 Coretta Scott King Award

The Coretta Scott King Award is an annual award presented by the Ethnic & Multicultural Information Exchange Round Table, part of the American Library Association (ALA). Named for Coretta Scott King, wife of Martin Luther King Jr., this award r ...

. In 1988, Clifton became the first author to have two books of poetry named finalists for one year's Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made ...

. (The award dates from 1918, the announcement of finalists from 1980.) She won the 1991/1992 Shelley Memorial Award, the 1996 Lannan Literary Award for Poetry

The Lannan Literary Awards are a series of awards and literary fellowships given out in various fields by the Lannan Foundation. Established in 1989, the awards are meant "to honor both established and emerging writers whose work is of exceptional ...

, and for ''Blessing the Boats: New and Collected Poems 1988–2000'' the 2000 National Book Award for Poetry.

From 1999 to 2005, she served on the Board of Chancellors of the Academy of American Poets

The Academy of American Poets is a national, member-supported organization that promotes poets and the art of poetry. The nonprofit organization was incorporated in the state of New York in 1934. It fosters the readership of poetry through outreach ...

. In 2007, she won the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize; the $100,000 prize honors a living U.S. poet whose "lifetime accomplishments warrant extraordinary recognition."

In 2010, Clifton received the Robert Frost Medal

The Poetry Society of America is a literary organization founded in 1910 by poets, editors, and artists. It is the oldest poetry organization in the United States. Past members of the society have included such renowned poets as Witter Bynner, Ro ...

for lifetime achievement from the Poetry Society of America.

Works

Poetry collections

*''Good Times'', New York: Random House, 1969 *''Good News About the Earth'', New York: Random House, 1972 *''An Ordinary Woman'', New York: Random House, 1974) *''Two-Headed Woman'',University of Massachusetts Press

The University of Massachusetts Press is a university press that is part of the University of Massachusetts Amherst

The University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass Amherst, UMass) is a public research university in Amherst, Massachusetts a ...

, Amherst, 1980

*''Good Woman: Poems and a Memoir: 1969–1980'', Brockport: BOA Editions, 1987 — finalist for the 1988 Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made ...

*''Next: New Poems'', Brockport: BOA Editions, Ltd., 1987 — finalist for the 1988 Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made ...

"Fiction"''Past winners & finalists by category''. The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved April 8, 2012. *''Ten Oxherding Pictures'', Santa Cruz: Moving Parts Press, 1988 *''Quilting: Poems 1987–1990'', Brockport: BOA Editions, 1991, *''The Book of Light'', Port Townsend:

Copper Canyon Press

Copper Canyon Press is an independent, non-profit small press, founded in 1972 specializing exclusively in the publication of poetry. It is located in Port Townsend, Washington.

Copper Canyon Press publishes new collections of poetry by both ...

, 1993

*''The Terrible Stories'', Brockport: BOA Editions, 1996

*''Blessing The Boats: New and Collected Poems 1988–2000'', Rochester: BOA Editions, 2000, ; Paw Prints, 2008, —winner of the National Book Award

The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors.

The Nat ...

"National Book Awards – 2000"National Book Foundation

The National Book Foundation (NBF) is an American nonprofit organization established, "to raise the cultural appreciation of great writing in America". Established in 1989 by National Book Awards, Inc.,Edwin McDowell. "Book Notes: 'The Joy Luc ...

. Retrieved April 8, 2012. (With acceptance speech by Clifton and essay by Megan Snyder-Kamp from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.)

*''Mercy'', Rochester: BOA Editions, 2004,

*''Voices'', Rochester: BOA Editions, 2008,

*''The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton'', Rochester: BOA Editions, 2012,

Children's books

* ''Three Wishes'' (Doubleday)

* ''The Boy Who Didn't Believe In Spring'' (Penguin)

* ; Reprint Yearling Books,

* ''The Times They Used To Be'' (Henry Holt & Co)

* ''All Us Come Cross the Water'' (Henry Holt)

* ''My Friend Jacob'' (Dutton)

* ''Amifika'' (Dutton)

* ''Sonora the Beautiful'' (Dutton)

* ''The Black B C's'' (Dutton)

* ''The Palm of My Heart: Poetry by African American Children''. Introduction by Lucille Clifton (San Val)

* ''Three Wishes'' (Doubleday)

* ''The Boy Who Didn't Believe In Spring'' (Penguin)

* ; Reprint Yearling Books,

* ''The Times They Used To Be'' (Henry Holt & Co)

* ''All Us Come Cross the Water'' (Henry Holt)

* ''My Friend Jacob'' (Dutton)

* ''Amifika'' (Dutton)

* ''Sonora the Beautiful'' (Dutton)

* ''The Black B C's'' (Dutton)

* ''The Palm of My Heart: Poetry by African American Children''. Introduction by Lucille Clifton (San Val)

The Everett Anderson series

* ''Everett Anderson's Goodbye'' (Henry Holt) * ''One of the Problems of Everett Anderson'' (Henry Holt) * ''Everett Anderson's Friend'' (Henry Holt) * ''Everett Anderson's Christmas Coming'' (Henry Holt) * ''Everett Anderson's 1-2-3'' (Henry Holt) * ''Everett Anderson's Year'' (Henry Holt) * ''Some of the Days of Everett Anderson'' (Henry Holt) * ''Everett Anderson's Nine Month Long'' (Henry Holt)Nonfiction

*''Generations: A Memoir'', New York: Random House, 1976,See also

* List of U.S. states' Poets LaureateReferences

Further reading

* Holladay, Hilary, ''Wild Blessings: The Poetry of Lucille Clifton'', Louisiana State University Press, 2004, * Lupton, Mary Jane, ''Lucille Clifton: her life and letters'', Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006, * Howard, Carol, "Lucille Clifton," "World Poets," Vol. 1. Scribner Writer Series, 2000, (set)External links

Clifton's Page at BOA Editions

Biography and critical appreciation of her work, and links to poems

at the Poetry Foundation.

for the WGBH series

New Television Workshop

for the WGBH series

New Television Workshop

"Jean Toomer's Cane and the Rise of the Harlem Renaissance"

Essay by Lucille Clifton.

PBS, September 8, 2006. (Audio)

Recorded in Los Angeles, CA, on May 21, 1996

From Lannan (Video 45 mins).

University of Illinois

Profile from Academy of American Poets

* * FBI file on Lucille Clifton {{DEFAULTSORT:Clifton, Lucille 1936 births 2010 deaths 20th-century African-American women 20th-century African-American writers 20th-century American poets 20th-century American women writers 21st-century African-American people 21st-century African-American women African-American history of Maryland African-American poets African-American women writers American people of Beninese descent American women academics American women poets Columbia University faculty Howard University alumni National Book Award winners People with polydactyly Poets from Maryland Poets from New York (state) Poets Laureate of Maryland St. Mary's College of Maryland faculty State University of New York at Fredonia alumni University of California, Santa Cruz faculty Writers from Buffalo, New York Writers from Maryland