Lost Cause on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an

The defeat of the Confederacy devastated many white Southerners economically, emotionally, and psychologically. Before the war, many proudly believed that their rich military tradition would avail them in the forthcoming conflict. Many sought consolation in attributing their loss to factors beyond their control, such as physical size and overwhelming brute force.

The

The defeat of the Confederacy devastated many white Southerners economically, emotionally, and psychologically. Before the war, many proudly believed that their rich military tradition would avail them in the forthcoming conflict. Many sought consolation in attributing their loss to factors beyond their control, such as physical size and overwhelming brute force.

The

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

pseudohistorical negationist

Historical negationism, also called denialism, is falsification or distortion of the historical record. It should not be conflated with ''historical revisionism'', a broader term that extends to newly evidenced, fairly reasoned academic reinterp ...

mythology

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narra ...

that claims the cause of the Confederate States

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

was just, heroic, and not centered on slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. First enunciated in 1866

Events January–March

* January 1

** Fisk University, a historically black university, is established in Nashville, Tennessee.

** The last issue of the abolitionist magazine '' The Liberator'' is published.

* January 6 – Ottoman t ...

, it has continued to influence racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagoni ...

, gender roles

A gender role, also known as a sex role, is a social role encompassing a range of behaviors and attitudes that are generally considered acceptable, appropriate, or desirable for a person based on that person's sex. Gender roles are usually cen ...

and religious attitudes in the South to the present day.

Lost Cause proponents typically praise the traditional culture of honor

Honour (British English) or honor (American English; see spelling differences) is the idea of a bond between an individual and a society as a quality of a person that is both of social teaching and of personal ethos, that manifests itself as a ...

and chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It was associated with the medieval Christian institution of knighthood; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours were governed b ...

of the antebellum South

In the history of the Southern United States, the Antebellum Period (from la, ante bellum, lit= before the war) spanned the end of the War of 1812 to the start of the American Civil War in 1861. The Antebellum South was characterized by ...

. They argue that enslaved people were treated well and deny that their condition was the central cause of the war, contrary to statements made by Confederate leaders, such as in the Cornerstone Speech. Instead, they frame the war as a defense of states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

, and as necessary to protect their agrarian economy against supposed Northern aggression. The Union victory is thus explained as the result of its greater size and industrial wealth, while the Confederate side is portrayed as having greater morality and military skill. Modern historians overwhelmingly disagree with these characterizations, noting that the central cause of the war was slavery.

There were two intense periods of Lost Cause activity: the first was around the turn of the 20th century, when efforts were made to preserve the memories of dying Confederate veterans, and the second was during the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

of the 1950s and 1960s, in reaction to growing public support for racial equality. Through actions such as building prominent Confederate monuments

In the United States, the public display of Confederate monuments, memorials and symbols has been and continues to be controversial. The following is a list of Confederate monuments and memorials that were established as public displays and symb ...

and writing history textbooks, Lost Cause organizations (including the United Daughters of the Confederacy

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) is an American neo-Confederate hereditary association for female descendants of Confederate Civil War soldiers engaging in the commemoration of these ancestors, the funding of monuments to them, ...

and Sons of Confederate Veterans) sought to ensure Southern whites would know what they called the "true" narrative of the Civil War, and therefore continue to support white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

policies such as Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the S ...

. In that regard, white supremacy is a central feature of the Lost Cause narrative.

Origins

Though the idea of the Lost Cause has more than one origin, it consists mainly of an argument that slavery was not the primary cause, or not a cause at all, of the Civil War. Such a narrative denies or minimizes the statements of the seceding states, each of which issued a statement explaining its decision to secede, and the wartime writings and speeches of Confederate leaders, such as CSA Vice President Alexander Stephens's Cornerstone Speech, instead favoring the leaders' more moderate postwar views. The Lost Cause argument stresses the idea ofsecession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

as a defense against a Northern threat to a Southern way of life, and says that the threat violated the states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

guaranteed by the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

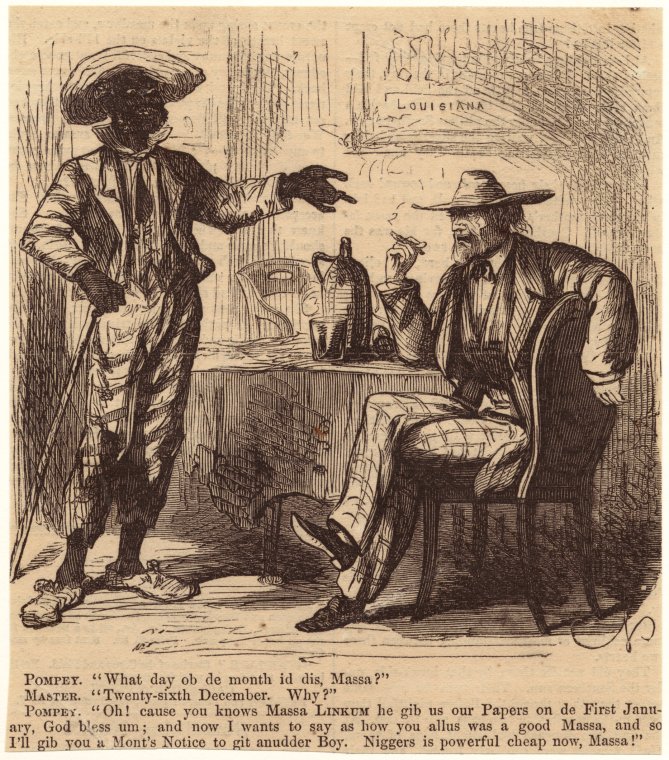

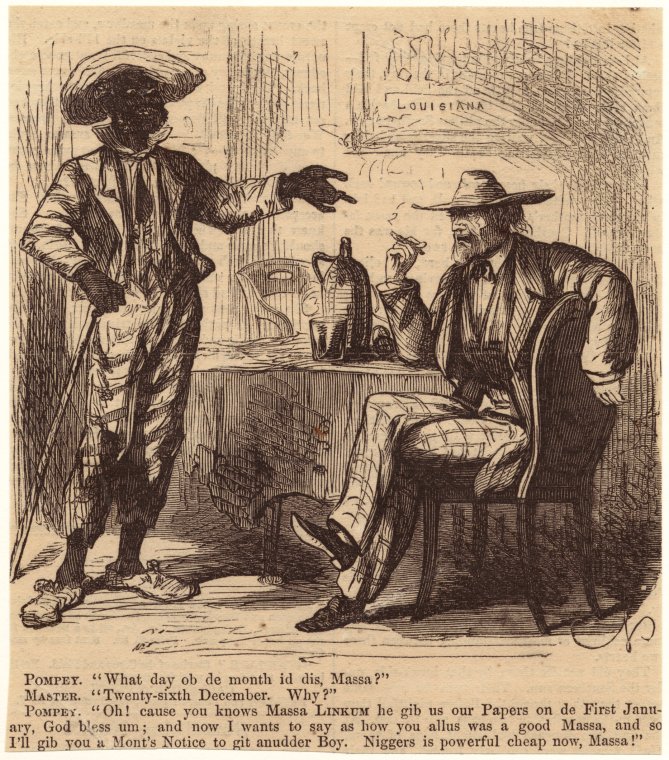

. It asserts that any state had the right to secede, a point strongly denied by the North. The Lost Cause portrays the South as more adherent to Christian values Christian values historically refers to values derived from the teachings of Jesus Christ. The term has various applications and meanings, and specific definitions can vary widely between denominations, geographical locations and different schools ...

than the allegedly greedy North. It portrays slavery as more benevolent than cruel, alleging that it taught Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

and "civilization". Stories of happy slaves are often used as propaganda in an effort to defend slavery; the United Daughters of the Confederacy

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) is an American neo-Confederate hereditary association for female descendants of Confederate Civil War soldiers engaging in the commemoration of these ancestors, the funding of monuments to them, ...

had a "Faithful Slave Memorial Committee" and erected the Heyward Shepherd monument

:''See also Blacks in John Brown's raid''

The Heyward Shepherd monument is a monument in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, constructed in 1931. It commemorates Heyward (sometimes spelled "Hayward" or "Heywood") Shepherd (1825 – October 16, 18 ...

in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is located in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The population was 285 at the 2020 census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, where the U.S. st ...

. These stories would be used to explain slavery to Northerners. The Lost Cause portrays slave owners being kind to their slaves. In explaining Confederate defeat, an assertion is made that the main factor was not qualitative inferiority in leadership or fighting ability but the massive quantitative superiority of the Yankee industrial machine. At the peak of troop strength in 1863, Union soldiers outnumbered Confederate soldiers by over two to one, and the Union had three times the bank deposits of the Confederacy.

History

19th century

The defeat of the Confederacy devastated many white Southerners economically, emotionally, and psychologically. Before the war, many proudly believed that their rich military tradition would avail them in the forthcoming conflict. Many sought consolation in attributing their loss to factors beyond their control, such as physical size and overwhelming brute force.

The

The defeat of the Confederacy devastated many white Southerners economically, emotionally, and psychologically. Before the war, many proudly believed that their rich military tradition would avail them in the forthcoming conflict. Many sought consolation in attributing their loss to factors beyond their control, such as physical size and overwhelming brute force.

The University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with highly selective ad ...

professor Gary W. Gallagher wrote:

The Lost Cause became a key part of the reconciliation process between North and South around 1900 and formed the basis of many white Southerners' postbellum war commemorations. The United Daughters of the Confederacy

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) is an American neo-Confederate hereditary association for female descendants of Confederate Civil War soldiers engaging in the commemoration of these ancestors, the funding of monuments to them, ...

, a major organization, has been associated with the Lost Cause for over a century.

Yale University history professor Rollin G. Osterweis

Rollin G. Osterweis (1907 – 1982) was an American historian in the Department of History at Yale University for twenty eight years while also serving as the Yale Director of Debating and Public Speaking. Osterweis was the author of numerous book ...

summarizes the content that pervaded "Lost Cause" writings:

Louisiana State University

Louisiana State University (officially Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, commonly referred to as LSU) is a public land-grant research university in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The university was founded in 1860 n ...

history professor Gaines Foster wrote in 2013:

The term "Lost Cause" first appeared in the title of an 1866 book by the Virginian author and journalist Edward A. Pollard

Edward Alfred Pollard (February 27, 1832December 17, 1872) was an American author, journalist, and Confederate sympathizer during the American Civil War who wrote several books on the causes and events of the war, notably ''The Lost Cause: A Ne ...

, ''The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates''. He promoted many of the aforementioned themes of the Lost Cause. In particular, he dismissed the role of slavery in starting the war and understated the cruelty of American slavery, even promoting it as a way of improving the lives of Africans:

However, it was the articles written by General Jubal A. Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was a Virginia lawyer and politician who became a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early resigned his U.S. Army commis ...

in the 1870s for the Southern Historical Society

The Southern Historical Society was an American organization founded to preserve archival materials related to the government of the Confederate States of America and to document the history of the Civil War.The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government'' by ex-Confederate President

The basic assumptions of the Lost Cause have proved durable for many in the modern South. The Lost Cause tenets frequently emerge during controversies surrounding public display of the

The basic assumptions of the Lost Cause have proved durable for many in the modern South. The Lost Cause tenets frequently emerge during controversies surrounding public display of the

Among writers on the Lost Cause,

Among writers on the Lost Cause,

Tenets of the Lost Cause movement include:

* Just as states had chosen to join the federal union, they could also choose to withdraw.

* Defense of

Tenets of the Lost Cause movement include:

* Just as states had chosen to join the federal union, they could also choose to withdraw.

* Defense of

In ''The Clansman'', the best known of the three novels, Dixon similarly claimed, "I have sought to preserve in this romance both the letter and the spirit of this remarkable period.... ''The Clansman'' develops the true story of the 'Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy', which overturned the Reconstruction regime."

"Lincoln is pictured as a kind, sympathetic man who is trying bravely to sustain his policies despite the pressures upon him to have a more vindictive attitude toward the Southern states."

In ''The Clansman'', the best known of the three novels, Dixon similarly claimed, "I have sought to preserve in this romance both the letter and the spirit of this remarkable period.... ''The Clansman'' develops the true story of the 'Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy', which overturned the Reconstruction regime."

"Lincoln is pictured as a kind, sympathetic man who is trying bravely to sustain his policies despite the pressures upon him to have a more vindictive attitude toward the Southern states."

"Regarding 'Song of the South' – The Film That Disney Doesn't Want You to See."

''IndieWire.com''. Retrieved January 22, 2019. In the framing story, the actor James Baskett played

online

with detailed bibliography pp. 231–57 * Coski, John M. ''The Confederate Battle Flag.'' (2005) * Cox, Karen L. ''Dixie's Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture'' (University Press of Florida, 2003) * * Davis, William C. ''Look Away: A History of the Confederate States of America.'' (2002) * * * * Freeman, Douglas Southall, ''The South to Posterity: An Introduction to the Writing of Confederate History'' (1939). * Gallagher, Gary W. and Alan T. Nolan (ed.), ''The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History'', Indiana University Press, 2000, . * Gallagher, Gary W., ''Jubal A. Early, the Lost Cause, and Civil War History: A Persistent Legacy (Frank L. Klement Lectures, No. 4)'', Marquette University Press, 1995, . * Goldfield, David. ''Still Fighting the Civil War.'' (2002) * Gulley, H. "Women and the lost cause: Preserving a Confederate identity in the American Deep South." ''Journal of historical geography'' 19.2 (1993): 125 * * * * Janney, Caroline E. "The Lost Cause.

''Encyclopedia Virginia'' (Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 2009)

* * Osterweis, Rollin G. ''The Myth of the Lost Cause, 1865–1900'' (1973

online

* Reardon, Carol, ''Pickett's Charge in History and Memory'', University of North Carolina Press, 1997, . * * Stampp, Kenneth. ''The Causes of the Civil War.'' (3rd edition 1991) * Ulbrich, David, "Lost Cause", ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', Heidler, David S., and Heidler, Jeanne T., eds., W. W. Norton & Company, 2000, . * Wilson, Charles Reagan, ''Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865–1920'', University of Georgia Press, 1980, . * Wilson, Charles Reagan, "The Lost Cause Myth in the New South Era" in ''Myth America: A Historical Anthology, Volume II''. 1997. Gerster, Patrick, and Cords, Nicholas. (editors.) Brandywine Press, St. James, NY.

''Whose Heritage? Public Symbols of the Confederacy''

map by

Interview with historian Adam Domby about ''The False Cause: Fraud, Fabrication, and White Supremacy in Confederate Memory''

on ''Half Hour of Heterodoxy''

Origins of the Lost Cause

an academic panel at ''Reconstruction and the Legacy of the War'' the 2016 summer conference hosted by the Civil War Institute. C-SPAN. {{DEFAULTSORT:Lost Cause Of The Confederacy Historiography of the American Civil War Aftermath of the American Civil War Cultural history of the American Civil War History of the Southern United States Historical negationism Social history of the United States Politics of the Southern United States Propaganda legends Pseudohistory Reconstruction Era Riots and civil disorder in South Carolina Riots and civil disorder during the Reconstruction Era Sons of Confederate Veterans White supremacy in the United States United Daughters of the Confederacy Nostalgia in the United States

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as ...

, a two-volume defense of the Southern cause, provided another important text in the history of the Lost Cause. Davis blamed the enemy for "whatever of bloodshed, of devastation, or shock to republican government has resulted from the war". He charged that the Yankees fought "with a ferocity that disregarded all the laws of civilized warfare". The book remained in print and often served to justify the Southern position and to distance it from slavery.

Early's original inspiration for his views may have come from Confederate General Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nor ...

. When Lee published his farewell order to the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

, he consoled his soldiers by speaking of the "overwhelming resources and numbers" that the Confederate army had fought against. In a letter to Early, Lee requested information about enemy strengths from May 1864 to April 1865, the period in which his army was engaged against Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

(the Overland Campaign and the Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

). Lee wrote, "My only object is to transmit, if possible, the truth to posterity, and do justice to our brave Soldiers." In another letter, Lee wanted all "statistics as regards numbers, destruction of private property by the Federal troops, &c." because he intended to demonstrate the discrepancy in strength between the two armies and believed it would "be difficult to get the world to understand the odds against which we fought". Referring to newspaper accounts that accused him of culpability in the loss, he wrote, "I have not thought proper to notice, or even to correct misrepresentations of my words & acts. We shall have to be patient, & suffer for awhile at least.... At present the public mind is not prepared to receive the truth."Gallagher, p. 12. All of the themes were made prominent by Early and the Lost Cause writers in the 19th century and continued to play an important role throughout the 20th.

In a November 1868 report, U.S. Army general George Henry Thomas, a Virginian who had fought for the Union in the war, noted efforts made by former Confederates to paint the Confederacy in a positive light:

Memorial associations such as the United Confederate Veterans, the United Daughters of the Confederacy

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) is an American neo-Confederate hereditary association for female descendants of Confederate Civil War soldiers engaging in the commemoration of these ancestors, the funding of monuments to them, ...

, and Ladies Memorial Association

A Ladies' Memorial Association (LMA) is a type of organization for women that sprang up all over the American South in the years after the American Civil War. Typically, these were organizations by and for women, whose goal was to raise monument ...

s integrated Lost-Cause themes to help white Confederate-sympathizing Southerners cope with the many changes during the era, most significantly Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

.Ulbrich, p. 1222. The institutions have lasted to the present and descendants of Southern soldiers continue to attend their meetings.

In 1879, John McElroy published '' Andersonville: A Story of Rebel Military Prisons'', which strongly criticized the Confederate treatment of prisoners and implied in the preface that the mythology of the Confederacy was well established and that criticism of the otherwise-lionized Confederates was met with disdain:

In 1907, Hunter Holmes McGuire, physician of Confederate general Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

, published in a book papers sponsored by the Grand Camp of Confederate Veterans of Virginia, supporting the Lost Cause tenets that "slavery asnot the cause of the war" and that "the North asthe aggressor in bringing on the war". The book quickly sold out and required a second edition.

Reunification of North and South

American historian Alan T. Nolan states that the Lost Cause "facilitated the reunification of the North and the South". He quotes historian Gaines M. Foster, who wrote that "signs of respect from former foes and northern publishers made acceptance of reunion easier. By the mid-eighties, most southerners had decided to build a future within a reunited nation. A few remained irreconcilable, but their influence in southern society declined rapidly." Nolan mentioned a second aspect: "The reunion was exclusively a white man's phenomenon and the price of the reunion was the sacrifice of theAfrican Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

."

The historian Caroline Janney stated:

The Yale historian David W. Blight wrote:

In exploring the literature of reconciliation, the historian William Tynes Cowa wrote, "The cult of the Lost Cause was part of a larger cultural project: the reconciliation of North and South after the Civil War". He identified a typical image in postwar fiction: a materialistic, rich Yankee man marrying an impoverished spiritual Southern bride as a symbol of happy national reunion. Examining films and visual art, Gallagher identified the theme of "white people North and South hoextol the ''American'' virtues both sides manifested during the war, to exalt the restored nation that emerged from the conflict, and to mute the role of African Americans".

Historian and journalist Bruce Catton argued that the myth or legend helped achieve national reconciliation between North and South. He concluded that "the legend of the lost cause has served the entire country very well", and he went on to say:

New South

Historians have stated that the "Lost Cause" theme helped white Southerners adjust to their new status and move forward into what became known as "the New South". Hillyer states that theConfederate Memorial Literary Society

The American Civil War Museum is a multi-site museum in the Greater Richmond Region of central Virginia, dedicated to the history of the American Civil War. The museum operates three sites: The White House of the Confederacy, American Civil Wa ...

(CMLS), founded by elite white women in Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

, in the 1890s, exemplifies that solution. The CMLS founded the Confederate Museum to document and to defend the Confederate cause and to recall the antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ar ...

mores that the new South's business ethos was thought to be displacing. By focusing on military sacrifice, rather than on grievances regarding the North, the Confederate Museum aided the process of sectional reconciliation, according to Hillyer. By depicting slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

as benevolent, the museum's exhibits reinforced the notion that Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the S ...

were a proper solution to the racial tensions that had escalated during Reconstruction. Lastly, by glorifying the common soldier and portraying the South as "solid", the museum promoted acceptance of industrial capitalism. Thus the Confederate Museum both critiqued and eased the economic transformations of the New South and enabled Richmond to reconcile its memory of the past with its hopes for the future and to leave the past behind as it developed new industrial and financial roles.

The historian Jacquelyn Dowd Hall stated that the Lost-Cause theme was fully developed around 1900 in a mood not of despair but of triumphalism for the New South. Much was left out of the Lost Cause:

Statues of Moses Jacob Ezekiel

The VirginianMoses Jacob Ezekiel

Moses Jacob Ezekiel, also known as Moses "Ritter von" Ezekiel (October 28, 1844 – March 27, 1917), was an American sculptor who lived and worked in Rome for the majority of his career. Ezekiel was "the first American-born Jewish artist to r ...

, the most prominent Confederate expatriate, was the only sculptor to have seen action during the Civil War. From his studio in Rome, where a Confederate flag hung proudly, he created a series of statues of Confederate "heroes" which both celebrated the Lost Cause in which he was a "true believer", and set a highly visible model for Confederate monument

In the United States, the public display of Confederate monuments, memorials and symbols has been and continues to be controversial. The following is a list of Confederate monuments and memorials that were established as public displays and symb ...

-erecting in the early 20th century.

According to journalist Lara Moehlman, "Ezekiel's work is integral to this sympathetic view of the Civil War". His Confederate statues included:

* ''Virginia Mourning Her Dead'' (1903), for which Ezekiel declined payment, although another source says that he charged half of his usual fee. The original is at his alma mater, the Virginia Military Institute

la, Consilio et Animis (on seal)

, mottoeng = "In peace a glorious asset, In war a tower of strength""By courage and wisdom" (on seal)

, established =

, type = Public senior military college

, accreditation = SACS

, endowment = $696.8 mill ...

, honoring the 10 cadets (students) who died, one (Thomas G. Jefferson, the president's great-great-nephew) in Ezekiel's arms, at the Battle of New Market

The Battle of New Market was fought on May 15, 1864, in Virginia during the Valley Campaigns of 1864 in the American Civil War. A makeshift Confederate army of 4,100 men defeated the larger Army of the Shenandoah under Major General Franz S ...

. It stands adjacent to the graves of six of the cadets. In 1914 Ezekiel gave a 3/4-size replica to the Museum of the Confederacy

The American Civil War Museum is a multi-site museum in the Greater Richmond Region of central Virginia, dedicated to the history of the American Civil War. The museum operates three sites: The White House of the Confederacy, American Civil War M ...

(since 2014 part of the American Civil War Museum) in his native Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, Californi ...

.

* ''Statue of Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

'' (1910), West Virginia State Capitol

The West Virginia State Capitol is the seat of government for the U.S. state of West Virginia, and houses the West Virginia Legislature and the office of the Governor of West Virginia. Located in Charleston, West Virginia, the building was ded ...

, Charleston, West Virginia

Charleston is the capital and most populous city of West Virginia. Located at the confluence of the Elk and Kanawha rivers, the city had a population of 48,864 at the 2020 census and an estimated population of 48,018 in 2021. The Charlesto ...

. A replica is at the Virginia Military Institute.

* ''Southern'', also called ''The Lookout'' (1910), Confederate Cemetery, Johnson's Island, Ohio. Commissioned by the United Daughters of the Confederacy

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) is an American neo-Confederate hereditary association for female descendants of Confederate Civil War soldiers engaging in the commemoration of these ancestors, the funding of monuments to them, ...

; Ezekiel asked only to be reimbursed the cost of the casting.

* '' Tyler Confederate Memorial Gateway'' (1913), City Cemetery, Hickman, Kentucky

Hickman is a city in and the county seat of Fulton County, Kentucky, United States. Located on the Mississippi River, the city had a population of 2,365 at the 2020 U.S. census and is classified as a home rule-class city. Hickman is part of th ...

. Commissioned by the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

* Statue of John Warwick Daniel

John Warwick Daniel (September 5, 1842June 29, 1910) was an American lawyer, author, and Democratic politician from Lynchburg, Virginia who promoted the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. Daniel served in both houses of the Virginia General Assemb ...

(c. 1913), Lynchburg, Virginia

Lynchburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. First settled in 1757 by ferry owner John Lynch, the city's population was 79,009 at the 2020 census. Located in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mounta ...

.

* ''Confederate Memorial'' (1914), Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

, Arlington, Virginia

Arlington County is a county in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The county is situated in Northern Virginia on the southwestern bank of the Potomac River directly across from the District of Columbia, of which it was once a part. The county ...

, which Ezekiel called ''New South

New South, New South Democracy or New South Creed is a slogan in the history of the American South first used after the American Civil War. Reformers used it to call for a modernization of society and attitudes, to integrate more fully with the ...

''. According to Moehlman, "no monument exemplifies the Lost Cause narrative better than Ezekiel's Confederate Memorial in Arlington, where the woman representing the South appears to be protecting the black figures below". Ezekiel included "faithful slaves" because he wanted to undermine what he called the "lies" told about the South and slavery in ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U ...

'', and wished to rewrite history "correctly" (his word) to depict black slaves' support for the Confederate cause. According to his descendant Judith Ezekiel, who has headed a group of his descendants calling for its removal, "This statue was a very, very deliberate part of revisionist history of racist America". According to historian Gabriel Reich, "the statue functions as propaganda for the Lost Cause.… It couldn't be worse."

Kali Holloway, director of the Make It Right Project, devoted to the removal of Confederate monuments, has said that:

Works of Thomas Dixon Jr.

No writer did more to establish the Lost Cause than Thomas Dixon Jr. (1864–1946), a Southern lecturer, novelist, playwright, filmmaker, andBaptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

minister.

Dixon, a North Carolinian, has been described as

Dixon predicted a " race war" if current trends continued unchecked that he believed white people would surely win, having "3,000 years of civilization in their favor". He also considered efforts to educate and civilize African Americans futile, even dangerous, and said that an African American was "all right" as a slave or laborer "but as an educated man he is a monstrosity". In the short term, Dixon saw white racial prejudice as "self preservation", and he worked to propagate a pro-Southern view of the recent Reconstruction period and spread it nationwide. He decried portrayals of Southerners as cruel and villainous in popular works such as ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U ...

'' (1852), seeking to counteract these portrayals with his own work.

He was a noted lecturer, often getting many more invitations to speak than he was capable of accepting. Moreover, he regularly drew very large crowds, larger than any other Protestant preacher in the United States at the time, and newspapers frequently reported on his sermons and addresses.

He resigned his minister's job so as to devote himself to lecturing full-time and supported his family that way. He had an immense following, and "his name had become a household word." In a typical review of the time, his talk was "decidedly entertaining and instructive.... There were great beds of solid thought, and timely instruction at the bottom".

Between 1899 and 1903, he was heard by more than 5,000,000 people; his play ''The Clansman

''The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' is a novel published in 1905, the second work in the Ku Klux Klan trilogy by Thomas Dixon Jr. (the others are ''The Leopard's Spots'' and ''The Traitor (Dixon novel), The Traitor''). Chro ...

'' was seen by over 4,000,000. He was commonly referred to as the best lecturer in the country. He enjoyed a "handsome income" from lectures and royalties on his novels, especially from his share of ''The Birth of a Nation

''The Birth of a Nation'', originally called ''The Clansman'', is a 1915 American silent epic drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and play ''The Clan ...

''. He bought a "steam yacht" and named it Dixie

Dixie, also known as Dixieland or Dixie's Land, is a nickname for all or part of the Southern United States. While there is no official definition of this region (and the included areas shift over the years), or the extent of the area it cove ...

.

After seeing a theatrical version of ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'', "he became obsessed with writing a trilogy of novels about the Reconstruction period." The trilogy comprised ''The Leopard's Spots. A Romance of the White Man's Burden—1865–1900'' (1902), '' The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' (1905), and ''The Traitor: A Story of the Fall of the Invisible Empire'' (1907). "Each of his trilogy novels had developed that black-and-white battle through rape/lynching scenarios that are always represented as prefiguring total racewar, should elite white men fail to resolve the nation's 'Negro Problem'." Dixon also wrote a novel about Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

''The Southerner'' (1913), "the story of what Davis called 'the real Lincoln'"another, ''The Man in Grey'' (1921), on Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nor ...

, and one on Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as ...

, ''The Victim'' (1914).

Dixon's most popular novels were '' The Leopard's Spots'' and ''The Clansman

''The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' is a novel published in 1905, the second work in the Ku Klux Klan trilogy by Thomas Dixon Jr. (the others are ''The Leopard's Spots'' and ''The Traitor (Dixon novel), The Traitor''). Chro ...

.'' Their influential spin-off, ''The Birth of a Nation

''The Birth of a Nation'', originally called ''The Clansman'', is a 1915 American silent epic drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and play ''The Clan ...

'' movie (1915), was the first film shown in the White House and repeated the next day to the entire Supreme Court, 38 Senators, and the Secretary of the Navy.

From the 20th century to the present

Confederate flag

The flags of the Confederate States of America have a history of three successive designs during the American Civil War. The flags were known as the "Stars and Bars", used from 1861 to 1863; the "Stainless Banner", used from 1863 to 1865; and ...

and various state flags. The historian John Coski noted that the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), the "most visible, active, and effective defender of the flag", "carried forward into the twenty-first century, virtually unchanged, the Lost Cause historical interpretations and ideological vision formulated at the turn of the twentieth". Coski wrote concerning "the flag wars of the late twentieth century":

The Confederate States used several flags during its existence from 1861 to 1865. Since the end of the American Civil War, the personal and official use of Confederate flags and flags derived from them has continued under considerable controversy. The second state flag of Mississippi, adopted in 1894 after the state's so-called " Redemption" and relinquished in 2020 during the George Floyd protests

The George Floyd protests were a series of protests and civil unrest against police brutality and racism that began in Minneapolis on May 26, 2020, and largely took place during 2020. The civil unrest and protests began as part of internat ...

, included the Confederate battle flag. The city flag

The list of city flags lists the flags of cities. Most of the city flags are based on the coat of arms or emblems of its city itself, and city flags can be also used by the coat of arms and emblems on its flag. Most of the city flags are flown o ...

of Trenton, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, which incorporates the Confederate battle flag, was adopted in 2001 as a protest against the Georgia General Assembly

The Georgia General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is bicameral, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives.

Each of the General Assembly's 236 members serve two-year terms and are direct ...

voting to significantly reduce the size of the Confederate battle flag on their state flag. The city flag of Trenton greatly resembles the former state flag of Georgia.

On March 23, 2015, a Confederate-flag-related case reached the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. Federal tribunals in the United States, federal court cases, and over Stat ...

. '' Walker v. Texas Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans'' centered on whether or not the state of Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

could deny a request by the SCV for vanity license plates that incorporated a Confederate battle flag. The Court heard the case on March 23, 2015. On June 18, 2015, the Supreme Court, in a 5–4 vote, held that Texas was entitled to reject the SCV proposal.

In October 2015, outrage erupted online following the discovery of a Texan school's geography textbook, which described slaves as "immigrants" and "workers". The publisher, McGraw-Hill

McGraw Hill is an American educational publishing company and one of the "big three" educational publishers that publishes educational content, software, and services for pre-K through postgraduate education. The company also publishes refere ...

, announced that it would change the wording.

Religious dimension

Charles Wilson argues that many white Southerners, most of whom were conservative and pious evangelical Protestants, sought reasons for the Confederacy's defeat inreligion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatur ...

. They felt that the Confederacy's defeat in the war was God's punishment for their sins and motivated by this belief, they increasingly turned to religion as their source of solace. The postwar era saw the birth of a regional "civil religion

Civil religion, also referred to as a civic religion, is the implicit religious values of a nation, as expressed through public rituals, symbols (such as the national flag), and ceremonies on sacred days and at sacred places (such as monuments, bat ...

" which was heavily laden with symbolism and ritual; clergymen were this new religion's primary celebrants. Wilson says that the ministers constructed

On both a cultural and religious level, white southerners tried to defend what their defeat in 1865 made impossible for them to defend on a political level. The Lost Cause, the South's defeat in a holy war, left southerners to face guilt, doubt, and the triumph of evil

Evil, in a general sense, is defined as the opposite or absence of good. It can be an extremely broad concept, although in everyday usage it is often more narrowly used to talk about profound wickedness and against common good. It is general ...

and they faced them by forming what C. Vann Woodward

Comer Vann Woodward (November 13, 1908 – December 17, 1999) was an American historian who focused primarily on the American South and race relations. He was long a supporter of the approach of Charles A. Beard, stressing the influence of unse ...

called a uniquely Southern sense of the tragedy

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a main character. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy ...

of history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

.

Poole stated that in fighting to defeat the Republican Reconstruction government in South Carolina in 1876, white conservative Democrats portrayed the Lost Cause scenario through "Hampton Days" celebrations and shouted, "Hampton or Hell!" They staged the contest between Reconstruction opponent and Democratic candidate Wade Hampton Wade Hampton may refer to the following people:

People

*Wade Hampton I (1752–1835), American soldier in Revolutionary War and War of 1812 and U.S. congressman

*Wade Hampton II (1791–1858), American plantation owner and soldier in War of 1812

*W ...

and incumbent Governor Daniel H. Chamberlain as a religious struggle between good and evil and called for " redemption". Indeed, throughout the South, the Democrats who overthrew Reconstruction were frequently called "Redeemers", echoing Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology of Christian belief and practice. Such study concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Christian tradition. Christian theologians use biblical exeg ...

.

Gender roles

Among writers on the Lost Cause,

Among writers on the Lost Cause, gender role

A gender role, also known as a sex role, is a social role encompassing a range of behaviors and attitudes that are generally considered acceptable, appropriate, or desirable for a person based on that person's sex. Gender roles are usually cen ...

s were a contested domain. Men typically honored the role which women played during the war by noting their total loyalty to the cause. Women, however, developed a much different approach to the cause by emphasizing female activism, initiative, and leadership. They explained that when all of the men left, the women took command, found substitute foods, rediscovered their old traditional skills with the spinning wheel

A spinning wheel is a device for spinning thread or yarn from fibres. It was fundamental to the cotton textile industry prior to the Industrial Revolution. It laid the foundations for later machinery such as the spinning jenny and spinnin ...

when factory cloth became unavailable, and ran all of the farm or plantation operations. They faced apparent danger without having men to perform the traditional role of being their protectors.

The popularization of the Lost Cause interpretation and the erection of monuments was primarily the work of Southern women, the center of which was the United Daughters of the Confederacy

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) is an American neo-Confederate hereditary association for female descendants of Confederate Civil War soldiers engaging in the commemoration of these ancestors, the funding of monuments to them, ...

(UDC).

The duty of memorializing the Confederate dead was a major activity for Southerners who were devoted to the Lost Cause, and chapters of the UDC played a central role in performing it. The UDC was especially influential across the South in the early 20th century, where its main role was to preserve and uphold the memory of Confederate veterans, especially the husbands, sons, fathers, and brothers who died in the war. Its long-term impact was to promote the Lost Cause image of the antebellum plantation South as an idealized society which was crushed by the forces of Yankee modernization, which also undermined traditional gender roles. In Missouri, a border state, the UDC was active in setting up its own system of memorials.

The Southern states set up their own pension systems for veterans and their dependents, especially for widows, since none of them was eligible to receive pensions under the federal pension system. The pensions were designed to honor the Lost Cause and reduce the severe poverty which was prevalent in the region. Male applicants for pensions had to demonstrate their continued loyalty to the "lost cause". Female applicants for pensions were rejected if their moral reputations were in question.

In Natchez, Mississippi

Natchez ( ) is the county seat of and only city in Adams County, Mississippi, United States. Natchez has a total population of 14,520 (as of the 2020 census). Located on the Mississippi River across from Vidalia in Concordia Parish, Louisiana, ...

, the local newspapers and veterans played a role in the maintenance of the Lost Cause. However, elite white women were central in establishing memorials such as the Civil War Monument which was dedicated on Memorial Day

Memorial Day (originally known as Decoration Day) is a federal holiday in the United States for mourning the U.S. military personnel who have fought and died while serving in the United States armed forces. It is observed on the last Monda ...

1890. The Lost Cause enabled women noncombatants to lay a claim to the central event in their redefinition of Southern history.

The UDC was quite prominent but not at all unique in its appeal to upscale white Southern women. "The number of women's clubs devoted to filiopietism and history was staggering," stated historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage

William Fitzhugh Brundage is an American historian, and William Umstead Distinguished Professor, at University of North Carolina. His works focus on white and black historical memory in the American South since the Civil War.

Early life

Brundage ...

. He noted two typical club women in Texas and Mississippi who between them belonged to the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the Daughters of the American Revolution

The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a person involved in the United States' efforts towards independence.

A non-profit group, they promote ...

, the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, the Daughters of the Pilgrims, the Daughters of the War of 1812

A daughter is a female offspring; a girl or a woman in relation to her parents. Daughterhood is the state of being someone's daughter. The male counterpart is a son. Analogously the name is used in several areas to show relations between gro ...

, the Daughters of Colonial Governors

A daughter is a female offspring; a girl or a woman in relation to her parents. Daughterhood is the state of being someone's daughter. The male counterpart is a son. Analogously the name is used in several areas to show relations between gro ...

, and the Daughters of the Founders and Patriots of America

A daughter is a female offspring; a girl or a woman in relation to her parents. Daughterhood is the state of being someone's daughter. The male counterpart is a son. Analogously the name is used in several areas to show relations between groups ...

, the Order of the First Families of Virginia

The Order of the First Families of Virginia was instituted on 11 May 1912 "to promote historical, biographical, and genealogical researches concerning Virginia history during the period when she was the only one of the thirteen original colonie ...

, and the Colonial Dames of America

The Colonial Dames of America (CDA) is an American organization composed of women who are descended from an ancestor who lived in British America from 1607 to 1775, and was of service to the colonies by either holding public office, being in t ...

as well as a few other historically-oriented societies. Comparable men, on the other hand, were much less interested in belonging to historical organizations; instead, they devoted themselves to secret fraternal societies and emphasized athletic, political, and financial exploits in order to prove their manhood. Brundage notes that after women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

came in 1920, the historical role of the women's organizations eroded.

In their heyday in the first two decades of the 20th century, Brundage concluded:

These women architects of whites' historical memory, by both explaining and mystifying the historical roots of white supremacy and elite power in the South, performed a conspicuous civic function at a time of heightened concern about the perpetuation of social and political hierarchies. Although denied the franchise, organized white women nevertheless played a dominant role in crafting the historical memory that would inform and undergird southern politics and public life.

Tenets

Tenets of the Lost Cause movement include:

* Just as states had chosen to join the federal union, they could also choose to withdraw.

* Defense of

Tenets of the Lost Cause movement include:

* Just as states had chosen to join the federal union, they could also choose to withdraw.

* Defense of states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

, rather than the preservation of chattel slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to per ...

, was the primary cause that led eleven Southern states to secede from the Union, thus precipitating the War.

* Secession was a justifiable and constitutional response to Northern cultural and economic aggression against the superior, chivalric Southern way of life, which included slavery. The South was fighting for its independence. Many still want it.

* The North was not attacking the South out of a pure, though misguided motive: to end slavery. Its motives were economic and venal.

* Slavery was not only a benign institution but a "positive good". It was not based on economic greed, and slaves were generally happy and loyal to their kind masters (see: Heyward Shepherd). Slavery was good for blacks and whites alike, a symbiosis

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or para ...

of races which were inherently unequal by nature. The lives of enslaved blacks were much better than they would be in Africa, or as free blacks in the North, where there were numerous anti-black riots. (Blacks were perceived as foreigners, immigrants taking jobs away from whites by working for less, and also as dangerously sexual.) It was not characterized by racism, rape, harsh working conditions, brutality, whipping, forced separation of families, and humiliation.

* Allgood identifies a Southern aristocratic chivalric ideal, typically called "the Southern Cavalier ideal", in the Lost Cause. It especially appeared in studies of Confederate partisans who fought behind Union lines, such as Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821October 29, 1877) was a prominent Confederate Army general during the American Civil War and the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan from 1867 to 1869. Before the war, Forrest amassed substantial wealt ...

, Turner Ashby, John Singleton Mosby, and John Hunt Morgan. Writers stressed how they embodied courage in the face of heavy odds, as well as horsemanship, manhood, and martial spirit.

* Confederate generals such as Robert E. Lee, Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) served as a general in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army. He saw extensive combat during his 34-year military career, figh ...

, and Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

represented the virtues of Southern nobility and fought bravely and humanely. On the other hand, most Northern generals were characterized by brutality and bloodlust, subjecting the Southern civilian population to depredations like Sherman's March to the Sea

Sherman's March to the Sea (also known as the Savannah campaign or simply Sherman's March) was a military campaign of the American Civil War conducted through Georgia from November 15 until December 21, 1864, by William Tecumseh Sherman, maj ...

and Philip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close a ...

's burning of the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridg ...

in the Valley Campaigns of 1864. Union General Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

is often portrayed as an alcoholic.

* Losses on the battlefield were inevitable, given the North's superiority in resources and manpower. Battlefield losses were also sometimes the result of betrayal and incompetence on the part of certain subordinates of General Lee, such as General James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost General officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his ...

, who was reviled for doubting Lee at Gettysburg.

* The Lost Cause focuses mainly on Lee and the Eastern Theater of operations, in northern Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. It usually takes Gettysburg as the turning point of the war, ignoring the Union victories in Tennessee and Mississippi, and that nothing could stop the Union army's humiliating advance through Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, South Carolina, and North Carolina, ending with the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

's surrender at Appomattox.

* General Sherman destroyed property out of meanness. Burning Columbia, South Carolina

Columbia is the capital of the U.S. state of South Carolina. With a population of 136,632 at the 2020 census, it is the second-largest city in South Carolina. The city serves as the county seat of Richland County, and a portion of the cit ...

, which had been a hotbed of secession, served no military purpose. It was intended only to humiliate and impoverish.

* Giving the vote to the newly freed slaves could only lead to political and social chaos. They were incapable of voting intelligently and were easily bribed or misled. Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

was a disaster, only benefitting greedy Northern interlopers (scalawags

In United States history, the term scalawag (sometimes spelled scallawag or scallywag) referred to white Southerners who supported Reconstruction policies and efforts after the conclusion of the American Civil War.

As with the term ''carpe ...

). It took great effort by chivalrous Southern gentlemen to reestablish law and order through white dominance.

* The order and customs of Southern society were in accordance with Christian virtue and God's will, given the inherent moral weakness of mankind.

Symbols

Confederate generals

The most powerful images and symbols of the Lost Cause were Robert E. Lee, Albert Sidney Johnston, and Pickett's Charge. David Ulbrich wrote, "Already revered during the war, Robert E. Lee acquired a divine mystique within Southern culture after it. Remembered as a leader whose soldiers would loyally follow him into every fight no matter how desperate, Lee emerged from the conflict to become an icon of the Lost Cause and the ideal of theantebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ar ...

Southern gentleman

A gentleman (Old French: ''gentilz hom'', gentle + man) is any man of good and courteous conduct. Originally, ''gentleman'' was the lowest rank of the landed gentry of England, ranking below an esquire and above a yeoman; by definition, the r ...

, an honorable and pious man who selflessly served Virginia and the Confederacy. Lee's tactical brilliance at Second Bull Run and Chancellorsville took on legendary status, and despite his accepting full responsibility for the defeat at Gettysburg, Lee remained largely infallible for Southerners and was spared criticism even from historians until recent times."

In terms of Lee's subordinates, the key villain in Jubal Early's view was General Longstreet. Although Lee took all responsibility for the defeats (particularly the one at Gettysburg), Early's writings place the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg squarely on Longstreet's shoulders by accusing him of failing to attack early in the morning of July 2, 1863, as instructed by Lee. In fact, however, Lee never expressed dissatisfaction with the second-day actions of his "Old War Horse". Longstreet was widely disparaged by Southern veterans because of his postwar cooperation with US President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

with whom he had shared a close friendship before the war and for joining the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

. Grant, in rejecting the Lost Cause arguments, said in an 1878 interview that he rejected the notion that the South had simply been overwhelmed by numbers. Grant wrote, "This is the way public opinion was made during the war and this is the way history is made now. We never overwhelmed the South.... What we won from the South we won by hard fighting." Grant further noted that when comparing resources, the "4,000,000 of negroes" who "kept the farms, protected the families, supported the armies, and were really a reserve force" were not treated as a southern asset.

"War of Northern Aggression"

One essential element of the Lost Cause movement was that the act of secession itself had been legitimate; otherwise, all of the Confederacy's leading figures would have become traitors to the United States. To legitimize the Confederacy's rebellion, Lost Cause intellectuals challenged the legitimacy of the federal government and the actions ofAbraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

as president. That was exemplified in "Force or Consent as the Basis of American Government" by Mary Scrugham in which she presented frivolous arguments against the legality of Lincoln's presidency. They include his receiving a minority and unmentioned plurality of the popular vote in the 1860 election and the false assertion that he made his position on slavery ambiguous. The accusations, though thoroughly refuted, gave rise to the belief that the North initiated the Civil War, making a designation of "The War of Northern Aggression" possible as one of the names of the American Civil War

The most common name for the American Civil War in modern American usage is simply "The Civil War". Although rarely used during the war, the term "War Between the States" became widespread afterward in the Southern United States. During and immed ...

.

Thomas Dixon Jr.'s novels

''The Leopard's Spots''

On the title page, Dixon citedJeremiah

Jeremiah, Modern: , Tiberian: ; el, Ἰερεμίας, Ieremíās; meaning "Yah shall raise" (c. 650 – c. 570 BC), also called Jeremias or the "weeping prophet", was one of the major prophets of the Hebrew Bible. According to Jewis ...

13:23: "Can the Ethiopian change his color, or the Leopard his spots?" He argued that just as the leopard cannot change his spots, the Negro cannot change his nature. The novel aimed to reinforce the superiority of the "Anglo-Saxon" race and advocate either for white dominance of black people or for the separation of the two races. According to historian and Dixon biographer Richard Allen Cook, "the Negro, according to Dixon, is a brute, not a citizen: a child of a degenerate race brought from Africa." Dixon expounded the views in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' of Philadelphia while he discussed the novel in 1902: "The negro is a human donkey. You can train him, but you can't make of him a horse." Dixon described the "towering figure of the freed negro" as "growing more and more ominous, until its menace overshadows the poverty, the hunger, the sorrows and the devastation of the South, throwing the blight of its shadow over future generations, a veritable black death for the land and its people." Using characters from ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U ...

'', he shows the "happy slave" who is now, free and manipulated by carpetbagger

In the history of the United States, carpetbagger is a largely historical term used by Southerners to describe opportunistic Northerners who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War, who were perceived to be exploiting the l ...

s, unproductive and disrespectful, and he believed that freedmen constantly pursued sexual relations with white women. In Dixon's work, the heroic Ku Klux Klan protects American women. "It is emphatically a man's book," said Dixon to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

''.

The novel, which "blazes with oratorial fireworks", "attracted attention as soon as it came from the press", and more than 100,000 copies were quickly sold. "Sales eventually passed the million mark; numerous foreign translations of the work appeared; and Dixon's fame was international."

''The Clansman''

In ''The Clansman'', the best known of the three novels, Dixon similarly claimed, "I have sought to preserve in this romance both the letter and the spirit of this remarkable period.... ''The Clansman'' develops the true story of the 'Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy', which overturned the Reconstruction regime."

"Lincoln is pictured as a kind, sympathetic man who is trying bravely to sustain his policies despite the pressures upon him to have a more vindictive attitude toward the Southern states."

In ''The Clansman'', the best known of the three novels, Dixon similarly claimed, "I have sought to preserve in this romance both the letter and the spirit of this remarkable period.... ''The Clansman'' develops the true story of the 'Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy', which overturned the Reconstruction regime."

"Lincoln is pictured as a kind, sympathetic man who is trying bravely to sustain his policies despite the pressures upon him to have a more vindictive attitude toward the Southern states." Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

was an attempt by Augustus Stoneman, a thinly-veiled reference to US Representative Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

of Pennsylvania, "the greatest and vilest man who ever trod the halls of the American Congress", to ensure that the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

would stay in power by securing the Southern black vote. Stoneman's hatred for US President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

stems from Johnson's refusal to disenfranchise Southern whites. Stoneman's anger towards former slaveholders is intensified after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, was assassinated by well-known stage actor John Wilkes Booth, while attending the play '' Our American Cousin'' at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Shot in the ...

, and Stoneman vows revenge on the South. His programs strip away the land owned by whites and give it to former slaves, as with the traditional idea of " forty acres and a mule". Men claiming to represent the government confiscate the material wealth of the South and destroy plantation-owning families. Finally, the former slaves are taught that they are superior to their former owners and should rise against them. These alleged injustices were the impetus for the creation of the Ku Klux Klan. "Mr. Dixon's purpose here is to show that the original formers of the Ku Klux Klan were modern knights errant, taking the only means at hand to right wrongs." Dixon's father belonged to the Klan, and his maternal uncle and boyhood idol, Col. Leroy McAfee, to whom ''The Clansman'' is dedicated, was a regional leader or, in the words of the dedication, "Grand Titan of the invisible Empire of the Ku Klux Klan".

The depiction of the Klan's burning of crosses, as shown in the illustrations of the first edition, is an innovation of Dixon. It had not previously been used by the Klan, but was later taken up by them.

"In Dixon's passionate prose, the book also treats at considerable length the poverty, shame, and degradation suffered by the Southerners at the hands of the Negroes and unscrupulous Northeners." Martial law is declared, US troops are sent in, as they were during Reconstruction. "The victory of the South was complete when the Klan defeats the federal troups throughout the state."

To publicize his views further, Dixon rewrote ''The Clansman'' as a play. Like the novel, it was a great commercial success; there were multiple touring companies presenting the play simultaneously in different cities. Sometimes, it was banned. ''Birth of a Nation'' is actually based on the play, which was unpublished until 2007, rather than directly on the novel.

''The Birth of a Nation''

Another prominent and influential popularizer of the Lost Cause perspective wasD. W. Griffith