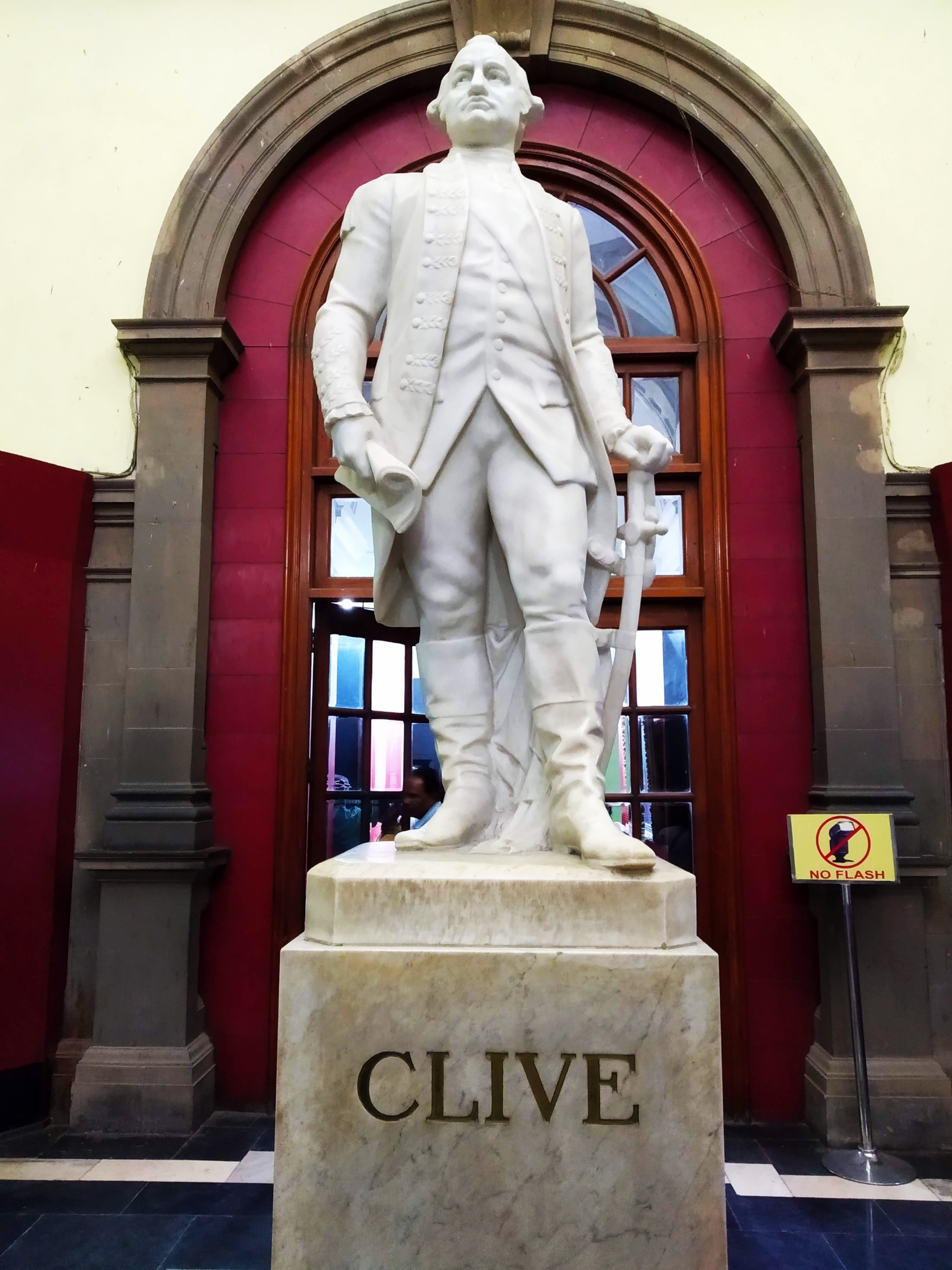

Lord Clive on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive, (29 September 1725 – 22 November 1774), also known as Clive of India, was the first British Governor of the

Clive's father was known to have a temper, which the boy apparently inherited. For reasons that are unknown, Clive was sent to live with his mother's sister in

Clive's father was known to have a temper, which the boy apparently inherited. For reasons that are unknown, Clive was sent to live with his mother's sister in

In 1744 Clive's father acquired for him a position as a "factor" or company agent in the service of the

In 1744 Clive's father acquired for him a position as a "factor" or company agent in the service of the

In 1720 France effectively nationalised the

In 1720 France effectively nationalised the

In the summer of 1751, Chanda Sahib left

In the summer of 1751, Chanda Sahib left

As Britain and France were once more at war, Clive sent the fleet up the river against the French colony of Chandannagar, while he besieged it by land. There was a strong incentive to capture the colony, as capture of a previous French settlement near

As Britain and France were once more at war, Clive sent the fleet up the river against the French colony of Chandannagar, while he besieged it by land. There was a strong incentive to capture the colony, as capture of a previous French settlement near

The whole hot season of 1757 was spent in negotiations with the Nawab of Bengal. In the middle of June Clive began his march from Chandannagar, with the British in boats and the sepoys along the right bank of the Hooghly River. During the rainy season, the Hooghly is fed by the overflow of the

The whole hot season of 1757 was spent in negotiations with the Nawab of Bengal. In the middle of June Clive began his march from Chandannagar, with the British in boats and the sepoys along the right bank of the Hooghly River. During the rainy season, the Hooghly is fed by the overflow of the

Clive came into direct contact with the Mughal himself, for the first time, a meeting which would prove beneficial in his later career. Prince Ali Gauhar escaped from

Clive came into direct contact with the Mughal himself, for the first time, a meeting which would prove beneficial in his later career. Prince Ali Gauhar escaped from

On 3 May 1765 Clive landed at Calcutta to learn that Mir Jafar had died, leaving him personally £70,000 (). Mir Jafar was succeeded by his son-in-law Kasim Ali, though not before the government had been further demoralised by taking £100,000 () as a gift from the new Nawab; while Kasim Ali had induced not only the viceroy of Awadh, but the emperor of Delhi himself, to invade

On 3 May 1765 Clive landed at Calcutta to learn that Mir Jafar had died, leaving him personally £70,000 (). Mir Jafar was succeeded by his son-in-law Kasim Ali, though not before the government had been further demoralised by taking £100,000 () as a gift from the new Nawab; while Kasim Ali had induced not only the viceroy of Awadh, but the emperor of Delhi himself, to invade  Clive had now an opportunity of repeating in

Clive had now an opportunity of repeating in

Later in 1768, Clive was elected a

Later in 1768, Clive was elected a  Clive was awarded an

Clive was awarded an

* Robert Clive's desk from his time at

* Robert Clive's desk from his time at

"Lord Clive," an essay by Thomas Babington Macaulay (January 1840)

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Clive, Robert Clive, 1st Baron 1725 births 1774 deaths British Army major generals Military personnel from Shropshire People from Market Drayton People educated at Merchant Taylors' School, Northwood Administrators in British India Barons in the Peerage of Ireland Peers of Ireland created by George III British Commanders-in-Chief of India British East India Company Army officers Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for English constituencies British MPs 1754–1761 British MPs 1761–1768 British MPs 1768–1774 British MPs 1774–1780 Knights Companion of the Order of the Bath Lord-Lieutenants of Montgomeryshire Lord-Lieutenants of Shropshire British military personnel who committed suicide British politicians who committed suicide Suicides by sharp instrument in England British East India Company Army generals Suicides in Westminster Fellows of the Royal Society Burials in Shropshire Mayors of places in Shropshire British governors of Bengal 18th-century suicides

Bengal Presidency

The Bengal Presidency, officially the Presidency of Fort William and later Bengal Province, was a subdivision of the British Empire in India. At the height of its territorial jurisdiction, it covered large parts of what is now South Asia and ...

. Clive has been widely credited for laying the foundation of the British East India Company rule in Bengal. He began as a writer (the term used then in India for an office clerk) for the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

(EIC) in 1744 and established Company rule in Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

by winning the Battle of Plassey in 1757. In return for supporting the Nawab

Nawab ( Balochi: نواب; ar, نواب;

bn, নবাব/নওয়াব;

hi, नवाब;

Punjabi : ਨਵਾਬ;

Persian,

Punjabi ,

Sindhi,

Urdu: ), also spelled Nawaab, Navaab, Navab, Nowab, Nabob, Nawaabshah, Nawabshah or Nobab, ...

Mir Jafar as ruler of Bengal, Clive was granted a jagir of £30,000 () per year which was the rent the EIC would otherwise pay to the Nawab for their tax-farming concession. When Clive left India he had a fortune of £180,000 () which he remitted through the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

.

Blocking impending French mastery of India, Clive improvised a 1751 military expedition that ultimately enabled the EIC to adopt the French strategy of indirect rule via puppet government. Hired by the EIC to return (1755) a second time to India, Clive conspired to secure the company's trade interests by overthrowing the ruler of Bengal, the richest state in India. Back in England from 1760 to 1765, he used the wealth accumulated from India to secure (1762) an Irish barony from the then Whig PM, Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle

Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne and 1st Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne, (21 July 169317 November 1768) was a British Whig statesman who served as the 4th and 6th Prime Minister of Great Britain, his official life extended ...

, and a seat for himself in Parliament, via Henry Herbert, 1st Earl of Powis, representing the Whigs in Shrewsbury, Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

(1761–1774), as he had previously in Mitchell, Cornwall

Mitchell (sometimes known as Michael or St Michael's) is a village in mid Cornwall, England. It is situated 14 miles (22 km) northeast of Redruth and 17 miles (27 km) west-southwest of Bodmin on the A30 trunk road.

Mitchell straddl ...

(1754–1755).

Clive's actions on behalf of the EIC have made him one of Britain's most controversial colonial figures. His achievements included checking French imperialist ambitions on the Coromandel Coast

The Coromandel Coast is the southeastern coastal region of the Indian subcontinent, bounded by the Utkal Plains to the north, the Bay of Bengal to the east, the Kaveri delta to the south, and the Eastern Ghats to the west, extending over an ...

and establishing EIC control over Bengal, thereby furthering the establishment of the British Raj, though he worked only as an agent of the East India Company, not of the British government. Vilified by his political rivals in Britain, he went on trial (1772 and 1773) before Parliament, where he was absolved from every charge. Historians have criticised Clive's management of Bengal during his tenure with the EIC and his responsibility in contributing to the Great Bengal Famine of 1770, which historians now estimate resulted in the deaths of between seven and ten million people.

Early life

Robert Clive was born at Styche, the Clive family estate, nearMarket Drayton

Market Drayton is a market town and electoral ward in the north of Shropshire, England, close to the Cheshire and Staffordshire borders. It is on the River Tern, and was formerly known as "Drayton in Hales" (c. 1868) and earlier simply as "D ...

in Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

, on 29 September 1725 to Richard Clive and Rebecca (née Gaskell) Clive. The family had held the small estate since the time of Henry VII and had a lengthy history of public service: members of the family included a Chancellor of the Exchequer of Ireland under Henry VIII, and a member of the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septem ...

. Robert's father, who supplemented the estate's modest income by practising as a lawyer, also served in Parliament for many years, representing Montgomeryshire

, HQ= Montgomery

, Government= Montgomeryshire County Council (1889–1974)Montgomeryshire District Council (1974–1996)

, Origin=

, Status=

, Start=

, End= ...

. Robert was their eldest son of thirteen children; he had seven sisters and five brothers, six of whom died in infancy.Harvey (1998), p. 11

Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

while still a toddler. The site is now Hope Hospital. Biographer Robert Harvey suggests that this move was made because Clive's father was busy in London trying to provide for the family. Daniel Bayley, the sister's husband, reported that the boy was "out of measure addicted to fighting". He was a regular troublemaker in the schools to which he was sent. When he was older he and a gang of teenagers established a protection racket

A protection racket is a type of racket and a scheme of organized crime perpetrated by a potentially hazardous organized crime group that generally guarantees protection outside the sanction of the law to another entity or individual from viol ...

that vandalised the shops of uncooperative merchants in Market Drayton. Clive also exhibited fearlessness at an early age. He is reputed to have climbed the tower of St Mary's Parish Church in Market Drayton and perched on a gargoyle

In architecture, and specifically Gothic architecture, a gargoyle () is a carved or formed grotesque with a spout designed to convey water from a roof and away from the side of a building, thereby preventing it from running down masonry walls ...

, frightening those down below.Treasure, p. 196

When Clive was nine his aunt died, and, after a brief stint in his father's cramped London quarters, he returned to Shropshire. There he attended the Market Drayton Grammar School, where his unruly behaviour (and an improvement in the family's fortunes) prompted his father to send him to Merchant Taylors' School in London. His bad behaviour continued, and he was then sent to a trade school in Hertfordshire to complete a basic education. Despite his early lack of scholarship, in his later years he devoted himself to improving his education. He eventually developed a distinctive writing style, and a speech in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

was described by William Pitt as the most eloquent he had ever heard.

First journey to India (1744–1753)

In 1744 Clive's father acquired for him a position as a "factor" or company agent in the service of the

In 1744 Clive's father acquired for him a position as a "factor" or company agent in the service of the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

, and Clive set sail for India. After running aground on the coast of Brazil, his ship was detained for nine months while repairs were completed. This enabled him to learn some Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

, one of the several languages then in use in south India because of the Portuguese centre at Goa

Goa () is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is located between the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north and Karnataka to the ...

. At this time the East India Company had a small settlement at Fort St. George near the village of Madraspatnam, later Madras, now the major Indian metropolis of Chennai

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

, in addition to others at Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

, Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second-m ...

, and Cuddalore

Cuddalore, also spelt as Kadalur (), is the city and headquarters of the Cuddalore District in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Situated south of Chennai, Cuddalore was an important port during the British Raj.

While the early history of Cudda ...

.Harvey (1998), p. 30 Clive arrived at Fort St. George in June 1744, and spent the next two years working as little more than a glorified assistant shopkeeper, tallying books and arguing with suppliers of the East India Company over the quality and quantity of their wares. He was given access to the governor's library, where he became a prolific reader.

Political situation in south India

The India Clive arrived in was divided into a number of successor states to theMughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

. Over the forty years since the death of the Emperor Aurangzeb

Muhi al-Din Muhammad (; – 3 March 1707), commonly known as ( fa, , lit=Ornament of the Throne) and by his regnal title Alamgir ( fa, , translit=ʿĀlamgīr, lit=Conqueror of the World), was the sixth emperor of the Mughal Empire, ruling ...

in 1707, the power of the emperor had gradually fallen into the hands of his provincial viceroys or '' Subahdars''. The dominant rulers on the Coromandel Coast

The Coromandel Coast is the southeastern coastal region of the Indian subcontinent, bounded by the Utkal Plains to the north, the Bay of Bengal to the east, the Kaveri delta to the south, and the Eastern Ghats to the west, extending over an ...

were the Nizam of Hyderabad, Asaf Jah I

Mir Qamar-ud-din Khan Siddiqi Bayafandi (11 August 16711 June 1748) also known as Chin Qilich qamaruddin Khan, Nizam-ul-Mulk, Asaf Jah and Nizam I, was the 1st Nizam of Hyderabad. He was married to the daughter of a Syed nobleman of Gulbarga. He ...

, and the Nawab of the Carnatic

The Carnatic Sultanate was a kingdom in South India between about 1690 and 1855, and was under the legal purview of the Nizam of Hyderabad, until their demise. They initially had their capital at Arcot in the present-day Indian state of Tamil N ...

, Anwaruddin Muhammed Khan

Anwaruddin Khan (1672 – 3 August 1749), also known as Muhammad Anwaruddin, was the 1st Nawab of Arcot. He belonged to a family of Qannauji Sheikhs. He was a major figure during the first two Carnatic Wars.

He was also Subedar of Thatta from 172 ...

. The Nawab nominally owed fealty to the nizam, but in many respects acted independently. Fort St. George and the French trading post at Pondicherry

Pondicherry (), now known as Puducherry ( French: Pondichéry ʊdʊˈtʃɛɹi(listen), on-dicherry, is the capital and the most populous city of the Union Territory of Puducherry in India. The city is in the Puducherry district on the sout ...

were both located in the Nawab's territory.

The relationship between the Europeans in India was influenced by a series of wars and treaties in Europe, and by competing commercial rivalry for trade on the subcontinent. Through the 17th and early 18th centuries, the French, Dutch, Portuguese, and British had vied for control of various trading posts, and for trading rights and favour with local Indian rulers. The European merchant companies raised bodies of troops to protect their commercial interests and latterly to influence local politics to their advantage. Military power was rapidly becoming as important as commercial acumen in securing India's valuable trade, and increasingly it was used to appropriate territory and to collect land revenue.

First Carnatic War

In 1720 France effectively nationalised the

In 1720 France effectively nationalised the French East India Company

The French East India Company (french: Compagnie française pour le commerce des Indes orientales) was a colonial commercial enterprise, founded on 1 September 1664 to compete with the English (later British) and Dutch trading companies in th ...

, and began using it to expand its imperial interests. This became a source of conflict with the British in India with the entry of Britain into the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George's ...

in 1744. The Indian theatre of the conflict is also known as the First Carnatic War

The First Carnatic War (1740–1748) was the Indian theatre of the War of the Austrian Succession and the first of a series of Carnatic Wars that established early British dominance on the east coast of the Indian subcontinent. In this conflict ...

, referring to the Carnatic region on the southeast coast of India. Hostilities in India began with a British naval attack on a French fleet in 1745, which led the French Governor-General Dupleix to request additional forces. On 4 September 1746, Madras was attacked by French forces led by La Bourdonnais. After several days of bombardment the British surrendered and the French entered the city. The British leadership was taken prisoner and sent to Pondicherry. It was originally agreed that the town would be restored to the British after negotiation but this was opposed by Dupleix, who sought to annex Madras to French holdings. The remaining British residents were asked to take an oath promising not to take up arms against the French; Clive and a handful of others refused, and were kept under weak guard as the French prepared to destroy the fort. Disguising themselves as natives, Clive and three others eluded their inattentive sentry, slipped out of the fort, and made their way to Fort St. David

Fort St David, now in ruins, was a British fort near the town of Cuddalore, a hundred miles south of Chennai on the Coromandel Coast of India. It is located near silver beach without any maintenance. It was named for the patron saint of Wales b ...

(the British post at Cuddalore

Cuddalore, also spelt as Kadalur (), is the city and headquarters of the Cuddalore District in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Situated south of Chennai, Cuddalore was an important port during the British Raj.

While the early history of Cudda ...

), some to the south. Upon his arrival, Clive decided to enlist in the Company army rather than remain idle; in the hierarchy of the company, this was seen as a step down. Clive was, however, recognised for his contribution in the defence of Fort St. David, where the French assault on 11 March 1747 was repulsed with the assistance of the Nawab of the Carnatic, and was given a commission as ensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

.Harvey (1998), p. 41

In the conflict, Clive's bravery came to the attention of Major Stringer Lawrence

Major-General Stringer Lawrence (February 1698–10 January 1775) was an English soldier, the first Commander-in-Chief of Fort William.

Origins

Lawrence was born at Hereford, England, the son of John Lawrence of Hereford by his wife Mary, about ...

, who arrived in 1748 to take command of the British troops at Fort St. David.Harvey (1998), p. 41 During the 1748 Siege of Pondicherry Clive distinguished himself in successfully defending a trench against a French sortie: one witness of the action wrote Clive's "platoon, animated by his exhortation, fired again with new courage and great vivacity upon the enemy." The siege was lifted in October 1748 with the arrival of the monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal osci ...

s, but the war came to a conclusion with the arrival in December of news of the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle. Madras was returned to the British as part of the peace agreement in early 1749.

Tanjore expedition

The end of the war between France and Britain did not, however, end hostilities in India. Even before news of the peace arrived in India, the British had sent an expedition toTanjore

Thanjavur (), also Tanjore, Pletcher 2010, p. 195 is a city in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Thanjavur is the 11th biggest city in Tamil Nadu. Thanjavur is an important center of South Indian religion, art, and architecture. Most of the ...

on behalf of a claimant to its throne. This expedition, on which Clive, now promoted to lieutenant, served as a volunteer, was a disastrous failure. Monsoons ravaged the land forces, and the local support claimed by their client was not in evidence. The ignominious retreat of the British force (which lost its baggage train to the pursuing Tanjorean army while crossing a swollen river) was a blow to the British reputation. Major Lawrence, seeking to recover British prestige, led the entire Madras garrison to Tanjore in response. At the fort of Devikottai on the Coleroon River the British force was confronted by the much larger Tanjorean army. Lawrence gave Clive command of 30 British soldiers and 700 sepoys, with orders to lead the assault on the fort. Clive led this force rapidly across the river and toward the fort, where the small British unit became separated from the sepoys and were enveloped by the Tanjorean cavalry. Clive was nearly cut down and the beachhead almost lost before reinforcements sent by Lawrence arrived to save the day. The daring move by Clive had an important consequence: the Tanjoreans abandoned the fort, which the British triumphantly occupied. The success prompted the Tanjorean rajah to open peace talks, which resulted in the British being awarded Devikottai and the costs of their expedition, and the British client was awarded a pension in exchange for renouncing his claim. Lawrence wrote of Clive's action that "he behaved in courage and in judgment much beyond what could be expected from his years."

On the expedition's return the process of restoring Madras was completed. Company officials, concerned about the cost of the military, slashed its size, denying Clive a promotion to captain in the process. Lawrence procured for Clive a position as the commissary at Fort St. George, a potentially lucrative posting (its pay included commissions on all supply contracts).

Second Carnatic War

The death ofAsaf Jah I

Mir Qamar-ud-din Khan Siddiqi Bayafandi (11 August 16711 June 1748) also known as Chin Qilich qamaruddin Khan, Nizam-ul-Mulk, Asaf Jah and Nizam I, was the 1st Nizam of Hyderabad. He was married to the daughter of a Syed nobleman of Gulbarga. He ...

, the Nizam of Hyderabad, in 1748 sparked a struggle to succeed him that is known as the Second Carnatic War

The Carnatic Wars were a series of military conflicts in the middle of the 18th century in India's coastal Carnatic region, a dependency of Hyderabad State, India. Three Carnatic Wars were fought between 1744 and 1763.

The conflicts involved n ...

, which was also furthered by the expansionist interests of French Governor-General Dupleix. Dupleix had grasped from the first war that small numbers of disciplined European forces (and well-trained sepoys) could be used to tip balances of power between competing interests, and used this idea to greatly expand French influence in southern India. For many years he had been working to negotiate the release of Chanda Sahib

Chanda Sahib (died 12 June 1752) was a subject of the Mughal Empire and the Nawab of the Carnatic between 1749 and 1752. Initially he was supported by the French during the Carnatic Wars. After his defeat at Arcot in 1751, he was captured by ...

, a longtime French ally who had at one time occupied the throne of Tanjore, and sought for himself the throne of the Carnatic. Chanda Sahib had been imprisoned by the Marathas

The Marathi people ( Marathi: मराठी लोक) or Marathis are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group who are indigenous to Maharashtra in western India. They natively speak Marathi, an Indo-Aryan language. Maharashtra was formed as a ...

in 1740; by 1748 he had been released from custody and was building an army at Satara.

Upon the death of Asaf Jah I, his son, Nasir Jung

Mir Ahmed Ali Khan Siddiqi Bayafandi, Nasir Jung, was the son of Nizam-ul-Mulk by his wife Saeed-un-nisa Begum. He was born 26 February 1712. He succeeded his father as the Nizam of Hyderabad State in 1748. He had taken up a title of ''Humayu ...

, seized the throne of Hyderabad, although Asaf Jah had designated as his successor his grandson, Muzaffar Jung

Muhyi ad-Din Muzaffar Jang Hidayat (died 13 February 1751) was the ruler of Hyderabad from 1750 until his death in 1751. His official name was ''Nawab Hidayat Muhi ud-din Sa'adu'llah Khan Bahadur, Muzaffar Jang, Nawab Subadar of the Deccan''. H ...

. The grandson, who was ruler of Bijapur, fled west to join Chanda Sahib, whose army was also reinforced by French troops sent by Dupleix. These forces met those of Anwaruddin Mohammed Khan in the Battle of Ambur in August 1749; Anwaruddin was slain, and Chanda Sahib victorious entered the Carnatic capital, Arcot

Arcot (natively spelt as Ārkāḍu) is a town and urban area of Ranipet district

Ranipet district is one of the 38 districts of Tamil Nadu, India, formed by trifurcating Vellore district. The Government of Tamil Nadu has announced its prop ...

. Anwaruddin's son, Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah

Muhammad Ali Khan Wallajah, or Muhammed Ali, Wallajah (7 July 1717 – 13 October 1795), was the Nawab of the Carnatic from 1749 until his death in 1795.

He declared himself Nawab in 1749. This position was disputed between Wallajah and Ch ...

, fled to Trichinopoly where he sought the protection and assistance of the British. In thanks for French assistance, the victors awarded them a number of villages, including territory nominally under British sway near Cuddalore and Madras. The British began sending additional arms to Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah and sought to bring Nasir Jung into the fray to oppose Chanda Sahib. Nasir Jung came south to Gingee

Gingee, also known as Senji or Jinji and originally called Singapuri, is a panchayat town in Viluppuram district in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Gingee is located between three hills covering a perimeter of 3 km, and lies west of the Sa ...

in 1750, where he requested and received a detachment of British troops. Chanda Sahib's forces advanced to meet them, but retreated after a brief long-range cannonade. Nasir Jung pursued, and was able to capture Arcot and his nephew, Muzaffar Jung. Following a series of fruitless negotiations and intrigues, Nasir Jung was assassinated by a rebellious soldier. This made Muzaffar Jung nizam and confirmed Chanda Sahib as Nawab of the Carnatic, both with French support. Dupleix was rewarded for French assistance with titled nobility and rule of the nizam's territories south of the Kistna River. His territories were "said to yield an annual revenue of over 350,000 rupees".

Robert Clive was not in southern India for many of these events. In 1750 Clive was afflicted with some sort of nervous disorder, and was sent north to Bengal to recuperate. It was there that he met and befriended Robert Orme

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

, who became his principal chronicler and biographer. Clive returned to Madras in 1751.

Siege of Arcot

In the summer of 1751, Chanda Sahib left

In the summer of 1751, Chanda Sahib left Arcot

Arcot (natively spelt as Ārkāḍu) is a town and urban area of Ranipet district

Ranipet district is one of the 38 districts of Tamil Nadu, India, formed by trifurcating Vellore district. The Government of Tamil Nadu has announced its prop ...

to besiege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characterize ...

Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah at Trichinopoly

Tiruchirappalli () ( formerly Trichinopoly in English), also called Tiruchi or Trichy, is a major tier II city in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu and the administrative headquarters of Tiruchirappalli district. The city is credited with bein ...

. This placed the British at Madras in a precarious position, since the latter was the last of their major allies in the area. The British company's military was also in some disarray, as Stringer Lawrence had returned to England in 1750 over a pay dispute, and much of the company was apathetic about the dangers the expanding French influence and declining British influence posed. The weakness of the British military command was exposed when a force was sent from Madras to support Muhammad Ali at Trichinopoly, but its commander, a Swiss mercenary, refused to attack an outpost at Valikondapuram. Clive, who accompanied the force as commissary, was outraged at the decision to abandon the siege. He rode to Cuddalore, and offered his services to lead an attack on Arcot if he was given a captain's commission, arguing this would force Chanda Sahib to either abandon the siege of Trichinopoly or significantly reduce the force there.

Madras and Fort St. David could supply him with only 200 Europeans, 300 sepoys, and three small cannons; furthermore, of the eight officers who led them, four were civilians like Clive, and six had never been in action. Clive, hoping to surprise the small garrison at Arcot, made a series of forced marches, including some under extremely rainy conditions. Although he did fail to achieve surprise, the garrison, hearing of the march being made under such arduous conditions, opted to abandon the fort and town; Clive occupied Arcot without firing a shot.

The fort was a rambling structure with a dilapidated wall a mile long (too long for his small force to effectively man), and it was surrounded by the densely packed housing of the town. Its moat was shallow or dry, and some of its towers were insufficiently strong to use as artillery mounts. Clive did the best he could to prepare for the onslaught he expected. He made a foray against the fort's former garrison, encamped a few miles away, which had no significant effect. When the former garrison was reinforced by 2,000 men Chanda Sahib sent from Trichinopoly it reoccupied the town on 15 September. That night Clive led most of his force out of the fort and launched a surprise attack on the besiegers. Because of the darkness, the besiegers had no idea how large Clive's force was, and they fled in panic.

The next day Clive learned that heavy guns he had requested from Madras were approaching, so he sent most of his garrison out to escort them into the fort. That night the besiegers, who had spotted the movement, launched an attack on the fort. With only 70 men in the fort, Clive once again was able to disguise his small numbers, and sowed sufficient confusion against his enemies that multiple assaults against the fort were successfully repulsed. That morning the guns arrived, and Chanda Sahib's men again retreated.

Over the next week Clive and his men worked feverishly to improve the defences, aware that another 4,000 men, led by Chanda Sahib's son Raza Sahib and accompanied by a small contingent of French troops, was on its way. (Most of these troops came from Pondicherry, not Trichinopoly, and thus did not have the effect Clive desired of raising that siege.) Clive was forced to reduce his garrison to about 300 men, sending the rest of his force to Madras in case the enemy army decided to go there instead. Raza Sahib arrived at Arcot, and on 23 September occupied the town. That night Clive launched a daring attack against the French artillery, seeking to capture their guns. The attack very nearly succeeded in its object, but was reversed when enemy sniper fire tore into the small British force. Clive himself was targeted on more than one occasion; one man pulled him down and was shot dead. The affair was a serious blow: 15 of Clive's men were killed, and another 15 wounded.

Over the next month the besiegers slowly tightened their grips on the fort. Clive's men were subjected to frequent sniper attacks and disease, lowering the garrison size to 200. He was heartened to learn that some 6,000 Maratha

The Marathi people ( Marathi: मराठी लोक) or Marathis are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group who are indigenous to Maharashtra in western India. They natively speak Marathi, an Indo-Aryan language. Maharashtra was formed as ...

forces had been convinced to come to his relief, but that they were awaiting payment before proceeding. The approach of this force prompted Raza Sahib to demand Clive's surrender; Clive's response was an immediate rejection, and he further insulted Raza Sahib by suggesting that he should reconsider sending his rabble of troops against a British-held position. The siege finally reached critical when Raza Sahib launched an all-out assault against the fort on 14 November. Clive's small force maintained its composure, and established killing fields outside the walls of the fort where the attackers sought to gain entry. Several hundred attackers were killed and many more wounded, while Clive's small force suffered only four British and two sepoy casualties.

The historian Thomas Babington Macaulay

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, (; 25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was a British historian and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster-General between 1846 and 1 ...

wrote a century later of the siege:

... the commander who had to conduct the defence ... was a young man of five and twenty, who had been bred as a book-keeper ... Clive ... had made his arrangements, and, exhausted by fatigue, had thrown himself on his bed. He was awakened by the alarm, and was instantly at his post ... After three desperate onsets, the besiegers retired behind the ditch. The struggle lasted about an hour ... the garrison lost only five or six men.His conduct during the siege made Clive famous in Europe. The

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

William Pitt the Elder

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British statesman of the Whig group who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him Chatham or William Pitt the Elder to distinguish ...

described Clive, who had received no formal military training whatsoever, as the "heaven-born general", endorsing the generous appreciation of his early commander, Major Lawrence. The Court of Directors of the East India Company voted him a sword worth £700, which he refused to receive unless Lawrence was similarly honoured.

Clive and Major Lawrence were able to bring the campaign to a successful conclusion. In 1754, the first of the provisional Carnatic treaties was signed between Thomas Saunders, the Company president at Madras, and Charles Godeheu

Charles Robert Godeheu de Zaimont was Acting Governor General of Pondicherry. He was the Commissioner of French army during Dupleix's reign.

Important incidents

In 1754, Godeheu gave up with the English the Indian territories, especially Madra ...

, the French commander who displaced Dupleix. Mohammed Ali Khan Wallajah was recognised as Nawab, and both nations agreed to equalise their possessions. When war again broke out in 1756, during Clive's absence in Bengal, the French obtained successes in the northern districts

The Northern Districts men's cricket team are one of six New Zealand first-class cricket teams that make up New Zealand Cricket.

They are based in the northern half of the North Island of New Zealand (excluding Auckland). They compete in the ...

, and it was Mohammed Ali Khan Wallajah's efforts which drove them from their settlements. The Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement, after Great Britain and Prussia's victory over France and Spain during the S ...

formally confirmed Mohammed Ali Khan Wallajah as Nawab of the Carnatic. It was a result of this action and the increased British influence that in 1765 a '' firman'' (decree) came from the Emperor of Delhi, recognising the British possessions in southern India.

Margaret Maskelyne had set out to find Clive who reportedly had fallen in love with her portrait. When she arrived Clive was a national hero. They were married at St. Mary's Church in (then) Madras on 18 February 1753. They then returned to England.

Clive also briefly sat as Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

for the Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

rotten borough

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act 1832, which had a very small electorate ...

of St Michael's, which then returned two Members, from 1754 to 1755. He and his colleague, John Stephenson were later unseated by petition of their defeated opponents, Richard Hussey and Simon Luttrell.

Second journey to India (1755–1760)

In July 1755, Clive returned to India to act as deputy governor of Fort St. David at Cuddalore. He arrived after having lost a considerable fortune en route, as the '' Doddington'', the lead ship of his convoy, was wrecked near Port Elizabeth, losing a chest of gold coins belonging to Clive worth £33,000 (). Nearly 250 years later in 1998, illegally salvaged coins from Clive's treasure chest were offered for sale, and in 2002 a portion of the coins were given to the South African government after protracted legal wrangling. Clive, now promoted to lieutenant-colonel in theBritish Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

, took part in the capture of the fortress of Gheriah, a stronghold of the Maratha Admiral Tuloji Angre. The action was led by Admiral James Watson and the British had several ships available, some Royal troops and some Maratha

The Marathi people ( Marathi: मराठी लोक) or Marathis are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group who are indigenous to Maharashtra in western India. They natively speak Marathi, an Indo-Aryan language. Maharashtra was formed as ...

allies. The overwhelming strength of the joint British and Maratha forces ensured that the battle was won with few losses. A fleet surgeon, Edward Ives, noted that Clive refused to take any part of the treasure divided among the victorious forces as was custom at the time.

Fall and recapture of Calcutta (1756–57)

Following this action Clive headed to his post at Fort St. David and it was there he received news of twin disasters for the British. Early in 1756,Siraj Ud Daulah

Mirza Muhammad Siraj-ud-Daulah ( fa, ; 1733 – 2 July 1757), commonly known as Siraj-ud-Daulah or Siraj ud-Daula, was the last independent Nawab of Bengal. The end of his reign marked the start of the rule of the East India Company over Be ...

had succeeded his grandfather Alivardi Khan

Alivardi Khan (1671 – 9 April 1756) was the Nawab of Bengal from 1740 to 1756. He toppled the Nasiri dynasty of Nawabs by defeating Sarfaraz Khan in 1740 and assumed power himself.

During much of his reign Alivardi encountered frequent Mar ...

as Nawab of Bengal. In June, Clive received news that the new Nawab had attacked the British at Kasimbazar

Cossimbazar is a sub-urban area of Berhampore City in the Berhampore CD block in the Berhampore subdivision in Murshidabad district in the Indian state of West Bengal."Cossimbazar" in ''Imperial Gazetteer of India'', Oxford, Clarendon Press, ...

and shortly afterwards on 20 June he had taken the fort at Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

. The losses to the Company because of the fall of Calcutta were estimated by investors at £2,000,000 (). Those British who were captured were placed in a punishment cell which became infamous as the Black Hole of Calcutta

The Black Hole of Calcutta was a dungeon in Fort William, Calcutta, measuring , in which troops of Siraj-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, held British prisoners of war on the night of 20 June 1756. John Zephaniah Holwell, one of the Britis ...

. In stifling summer heat, it was reported that 43 of the 64 prisoners died as a result of suffocation or heat stroke. While the Black Hole became infamous in Britain, it is debatable whether the Nawab was aware of the incident.

By Christmas 1756, as no response had been received to diplomatic letters to the Nawab, Admiral Charles Watson and Clive were dispatched to attack the Nawab's army and remove him from Calcutta by force. Their first target was the fortress of Baj-Baj which Clive approached by land while Admiral Watson bombarded it from the sea. The fortress was quickly taken with minimal British casualties. Shortly afterwards, on 2 January 1757, Calcutta itself was taken with similar ease.

Approximately a month later, on 3 February 1757, Clive encountered the army of the Nawab itself. For two days, the army marched past Clive's camp to take up a position east of Calcutta. Sir Eyre Coote, serving in the British forces, estimated the enemy's strength as 40,000 cavalry, 60,000 infantry and thirty cannon. Even allowing for overestimation this was considerably more than Clive's force of approximately 540 British infantry, 600 Royal Navy sailors, 800 local sepoys, fourteen field guns and no cavalry. The British forces attacked the Nawab's camp during the early morning hours of 5 February 1757. In this battle, unofficially called the 'Calcutta Gauntlet', Clive marched his small force through the entire Nawab's camp, despite being under heavy fire from all sides. By noon, Clive's force broke through the besieging camp and arrived safely at Fort William. During the assault, around one tenth of the British attackers became casualties. (Clive reported his losses at 57 killed and 137 wounded.) While technically not a victory in military terms, the sudden British assault intimidated the Nawab. He sought to make terms with Clive, and surrendered control of Calcutta on 9 February, promising to compensate the East India Company for damages suffered and to restore its privileges.

War with Siraj Ud Daulah

As Britain and France were once more at war, Clive sent the fleet up the river against the French colony of Chandannagar, while he besieged it by land. There was a strong incentive to capture the colony, as capture of a previous French settlement near

As Britain and France were once more at war, Clive sent the fleet up the river against the French colony of Chandannagar, while he besieged it by land. There was a strong incentive to capture the colony, as capture of a previous French settlement near Pondicherry

Pondicherry (), now known as Puducherry ( French: Pondichéry ʊdʊˈtʃɛɹi(listen), on-dicherry, is the capital and the most populous city of the Union Territory of Puducherry in India. The city is in the Puducherry district on the sout ...

had yielded the combined forces prizes valued at £130,000 (). After consenting to the siege, the Nawab unsuccessfully sought to assist the French. Some officials of the Nawab's court formed a confederacy to depose him. Jafar Ali Khan, also known as Mir Jafar, the Nawab's commander-in-chief, led the conspirators. With Admiral Watson, Governor Drake and Mr. Watts, Clive made a gentlemen's agreement in which it was agreed to give the office of viceroy of Bengal, Bihar

Bihar (; ) is a state in eastern India. It is the 2nd largest state by population in 2019, 12th largest by area of , and 14th largest by GDP in 2021. Bihar borders Uttar Pradesh to its west, Nepal to the north, the northern part of West ...

and Odisha

Odisha (English: , ), formerly Orissa ( the official name until 2011), is an Indian state located in Eastern India. It is the 8th largest state by area, and the 11th largest by population. The state has the third largest population of ...

to Mir Jafar, who was to pay £1,000,000 () to the company for its losses in Calcutta and the cost of its troops, £500,000 () to the British inhabitants of Calcutta, £200,000 () to the native inhabitants, and £70,000 () to its Armenian merchants.

Clive employed Umichand, a rich Bengali trader, as an agent between Mir Jafar and the British officials. Umichand threatened to betray Clive unless he was guaranteed, in the agreement itself, £300,000 (). To dupe him a second fictitious agreement was shown to him with a clause to this effect. Admiral Watson refused to sign it. Clive deposed later to the House of Commons that, "to the best of his remembrance, he gave the gentleman who carried it leave to sign his name upon it; his lordship never made any secret of it; he thinks it warrantable in such a case, and would do it again a hundred times; he had no interested motive in doing it, and did it with a design of disappointing the expectations of a rapacious man." It is nevertheless cited as an example of Clive's unscrupulousness.

Plassey

The whole hot season of 1757 was spent in negotiations with the Nawab of Bengal. In the middle of June Clive began his march from Chandannagar, with the British in boats and the sepoys along the right bank of the Hooghly River. During the rainy season, the Hooghly is fed by the overflow of the

The whole hot season of 1757 was spent in negotiations with the Nawab of Bengal. In the middle of June Clive began his march from Chandannagar, with the British in boats and the sepoys along the right bank of the Hooghly River. During the rainy season, the Hooghly is fed by the overflow of the Ganges

The Ganges ( ) (in India: Ganga ( ); in Bangladesh: Padma ( )). "The Ganges Basin, known in India as the Ganga and in Bangladesh as the Padma, is an international river to which India, Bangladesh, Nepal and China are the riparian states." is ...

to the north through three streams, which in the hot months are nearly dry. On the left bank of the Bhagirathi, the most westerly of these, above Chandernagore, stands Murshidabad, the capital of the Mughal viceroys of Bengal. Some miles farther down is the field of Plassey, then an extensive grove of mango trees.

On 21 June 1757, Clive arrived on the bank opposite Plassey, in the midst of the first outburst of monsoon rain. His whole army amounted to 1,100 Europeans and 2,100 sepoy troops, with nine field-pieces. The Nawab had drawn up 18,000 horse, 50,000-foot and 53 pieces of heavy ordnance, served by French artillerymen. For once in his career Clive hesitated, and called a council of sixteen officers to decide, as he put it, "whether in our present situation, without assistance, and on our own bottom, it would be prudent to attack the Nawab, or whether we should wait till joined by some country (Indian) power." Clive himself headed the nine who voted for delay; Major Eyre Coote Eyre Coote may refer to:

*Eyre Coote (East India Company officer) (1726–1783), Irish soldier and Commander-in-chief of India

*Eyre Coote (British Army officer) (1762–1823), Irish-born general in the British Army

* Eyre Coote (MP) (1806–1834), ...

led the seven who counselled immediate attack. But, either because his daring asserted itself, or because of a letter received from Mir Jafar, Clive was the first to change his mind and to communicate with Major Eyre Coote. One tradition, followed by Macaulay, represents him as spending an hour in thought under the shade of some trees, while he resolved the issues of what was to prove one of the decisive battles of the world. Another, turned into verse by Sir Alfred Lyall, pictures his resolution as the result of a dream. However that may be, he did well as a soldier to trust to the dash and even rashness that had gained Arcot and triumphed at Calcutta since retreat, or even delay, might have resulted in defeat.

After heavy rain, Clive's 3,200 men and the nine guns crossed the river and took possession of the grove and its tanks of water, while Clive established his headquarters in a hunting lodge. On 23 June, the engagement took place and lasted the whole day, during which remarkably little actual fighting took place. Gunpowder for the cannons of the Nawab was not well protected from rain. That impaired those cannons. Except for the 40 Frenchmen and the guns they worked, the Indian side could do little to reply to the British cannonade (after a spell of rain), which, with the 39th Regiment, scattered the host, inflicting on it a loss of 500 men. Clive had already made a secret agreement with aristocrats in Bengal, including Jagat Seth

The Jagat Seth family was a wealthy merchant, banker and money lender family from Murshidabad in Bengal during the time of the Nawabs of Bengal.

History

The house was founded by Jain Hiranand Shah from Nagaur, Rajasthan, who came to Patna in ...

and Mir Jafar. Clive restrained Major Kilpatrick, for he trusted to Mir Jafar's abstinence, if not desertion to his ranks, and knew the importance of sparing his own small force. He was fully justified in his confidence in Mir Jafar's treachery to his master, for he led a large portion of the Nawab's army away from the battlefield, ensuring his defeat.

Clive lost hardly any European troops; in all 22 sepoys

''Sepoy'' () was the Persian-derived designation originally given to a professional Indian infantryman, traditionally armed with a musket, in the armies of the Mughal Empire.

In the 18th century, the French East India Company and its oth ...

were killed and 50 wounded. It is curious in many ways that Clive is now best-remembered for this battle, which was essentially won by suborning the opposition rather than through fighting or brilliant military tactics. Whilst it established British military supremacy in Bengal, it did not secure the East India Company's control over Upper India, as is sometimes claimed. That would come only seven years later in 1764 at the Battle of Buxar, where Sir Hector Munro defeated the combined forces of the Mughal Emperor and the Nawab of Awadh

The Nawab of Awadh or the Nawab of Oudh was the title of the rulers who governed the state of Awadh (anglicised as Oudh) in north India during the 18th and 19th centuries. The Nawabs of Awadh belonged to a dynasty of Persian origin from Nishap ...

in a much more closely fought encounter.

Siraj Ud Daulah

Mirza Muhammad Siraj-ud-Daulah ( fa, ; 1733 – 2 July 1757), commonly known as Siraj-ud-Daulah or Siraj ud-Daula, was the last independent Nawab of Bengal. The end of his reign marked the start of the rule of the East India Company over Be ...

fled from the field on a camel, securing what wealth he could. He was soon captured by Mir Jafar's forces and later executed by the assassin Mohammadi Beg. Clive entered Murshidabad and established Mir Jafar as Nawab, the price which had been agreed beforehand for his treachery. Clive was taken through the treasury, amid £1,500,000 () sterling's worth of rupees, gold and silver plate, jewels and rich goods, and besought to ask what he would. Clive took £160,000 (), a vast fortune for the day, while £500,000 () was distributed among the army and navy of the East India Company, and provided gifts of £24,000 () to each member of the company's committee, as well as the public compensation stipulated for in the treaty.

In this extraction of wealth Clive followed a usage fully recognised by the company, although this was the source of future corruption which Clive was later sent to India again to correct. The company itself acquired revenue of £100,000 () a year, and a contribution towards its losses and military expenditure of £1,500,000 sterling (). Mir Jafar further discharged his debt to Clive by afterwards presenting him with the quit-rent of the company's lands in and around Calcutta, amounting to an annuity of £27,000 () for life, and leaving him by will the sum of £70,000 (), which Clive devoted to the army.

Further campaigns

=Battle of Condore

= While busy with the civil administration, Clive continued to follow up his military success. He sent Major Coote in pursuit of the French almost as far asBenares

Varanasi (; ; also Banaras or Benares (; ), and Kashi.) is a city on the Ganges river in northern India that has a central place in the traditions of pilgrimage, death, and mourning in the Hindu world.

*

*

*

* The city has a syncretic tra ...

. He dispatched Colonel Forde to Vizagapatam

, image_alt =

, image_caption = From top, left to right: Visakhapatnam aerial view, Vizag seaport, Simhachalam Temple, Aerial view of Rushikonda Beach, Beach road, Novotel Visakhapatnam, INS Kursura submarine museum, ...

and the northern districts of Madras, where Forde won the Battle of Condore (1758), pronounced by Broome "one of the most brilliant actions on military record".

=Mughals

= Clive came into direct contact with the Mughal himself, for the first time, a meeting which would prove beneficial in his later career. Prince Ali Gauhar escaped from

Clive came into direct contact with the Mughal himself, for the first time, a meeting which would prove beneficial in his later career. Prince Ali Gauhar escaped from Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders ...

after his father, the Mughal Emperor

The Mughal emperors ( fa, , Pādishāhān) were the supreme heads of state of the Mughal Empire on the Indian subcontinent, mainly corresponding to the modern countries of India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh. The Mughal rulers styled t ...

Alamgir II, had been murdered by the usurping Vizier

A vizier (; ar, وزير, wazīr; fa, وزیر, vazīr), or wazir, is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the near east. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called '' katib'' (secretary), who was ...

Imad-ul-Mulk

Feroze Jung III or Nizam Shahabuddin Muhammad Feroz Khan Siddiqi Bayafandi also known by his sobriquet Imad-ul-Mulk, was the grand vizier of the Mughal Empire allied with the Maratha Empire, who were often described as a de facto ruler of the ...

and his Maratha

The Marathi people ( Marathi: मराठी लोक) or Marathis are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group who are indigenous to Maharashtra in western India. They natively speak Marathi, an Indo-Aryan language. Maharashtra was formed as ...

associate Sadashivrao Bhau

Sadashivrao Bhau Peshwa (3 August 1730 – 14 January 1761) was son of Chimaji Appa (younger brother of Bajirao I) and Rakhmabai (Pethe family) and the nephew of Baji Rao I. He was a finance minister during the reign of Maratha emperor Chhatr ...

.

Prince Ali Gauhar was welcomed and protected by Shuja-ud-Daula

Shuja-ud-Daula (b. – d. ) was the Subedar and Nawab of Oudh and the Vizier of Delhi from 5 October 1754 to 26 January 1775.

Early life

Shuja-ud-Daula was the son of the Mughal Grand Vizier Safdarjung chosen by Ahmad Shah Bahadur. Unlik ...

, the Nawab of Awadh

The Nawab of Awadh or the Nawab of Oudh was the title of the rulers who governed the state of Awadh (anglicised as Oudh) in north India during the 18th and 19th centuries. The Nawabs of Awadh belonged to a dynasty of Persian origin from Nishap ...

. In 1760, after gaining control over Bihar

Bihar (; ) is a state in eastern India. It is the 2nd largest state by population in 2019, 12th largest by area of , and 14th largest by GDP in 2021. Bihar borders Uttar Pradesh to its west, Nepal to the north, the northern part of West ...

, Odisha

Odisha (English: , ), formerly Orissa ( the official name until 2011), is an Indian state located in Eastern India. It is the 8th largest state by area, and the 11th largest by population. The state has the third largest population of ...

and some parts of the Bengal, Ali Gauhar and his Mughal Army of 30,000 intended to overthrow Mir Jafar and the Company in order to reconquer the riches of the eastern Subahs for the Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

. Ali Gauhar was accompanied by Muhammad Quli Khan, Hidayat Ali, Mir Afzal, Kadim Husein and Ghulam Husain Tabatabai. Their forces were reinforced by the forces of Shuja-ud-Daula and Najib-ud-Daula

Najib ad-Dawlah ( ps, نجيب الدوله), also known as Najib Khan Yousafzai ( ps, نجيب خان), was a Rohilla Yousafzai Afghan who earlier served as a Mughal serviceman but later deserted the cause of the Mughals and joined Ahmed S ...

. The Mughals were also joined by Jean Law and 200 Frenchmen, and waged a campaign against the British during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

.

Prince Ali Gauhar successfully advanced as far as Patna

Patna (

), historically known as Pataliputra, is the capital and largest city of the state of Bihar in India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Patna had a population of 2.35 million, making it the 19th largest city in India. ...

, which he later besieged with a combined army of over 40,000 in order to capture or kill Ramnarian, a sworn enemy of the Mughals. Mir Jafar was terrified at the near demise of his cohort and sent his own son Miran to relieve Ramnarian and retake Patna. Mir Jafar also implored the aid of Robert Clive, but it was Major John Caillaud, who defeated and dispersed Prince Ali Gauhar's army.

=Dutch aggression

= While Clive was preoccupied with fighting the French, the Dutch directors of the outpost atChinsurah

Hugli-Chuchura or Hooghly-Chinsurah is a city and a municipality of Hooghly district in the Indian state of West Bengal. It lies on the bank of Hooghly River, 35 km north of Kolkata. It is located in the district of Hooghly and is home t ...

, not far from Chandernagore

Chandannagar french: Chandernagor ), also known by its former name Chandernagore and French name Chandernagor, is a city in the Hooghly district in the Indian state of West Bengal. It is headquarter of the Chandannagore subdivision and is part ...

, seeing an opportunity to expand their influence, agreed to send additional troops to Chinsurah. Despite Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

not formally being at war, a Dutch fleet of seven ships, containing more than fifteen hundred European and Malay troops, came from Batavia

Batavia may refer to:

Historical places

* Batavia (region), a land inhabited by the Batavian people during the Roman Empire, today part of the Netherlands

* Batavia, Dutch East Indies, present-day Jakarta, the former capital of the Dutch East In ...

and arrived at the mouth of the Hooghly River in October 1759, while Mir Jafar, the Nawab of Bengal, was meeting with Clive in Calcutta. They met a mixed force of British and local troops at Chinsurah

Hugli-Chuchura or Hooghly-Chinsurah is a city and a municipality of Hooghly district in the Indian state of West Bengal. It lies on the bank of Hooghly River, 35 km north of Kolkata. It is located in the district of Hooghly and is home t ...

, just outside Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

. The British, under Colonel Francis Forde, defeated the Dutch in the Battle of Chinsurah

The Battle of Chinsurah (also known as the Battle of Biderra or Battle of HooglySpectrum Modern History Of India, Rajiv Ahir, page 41.) took place near Chinsurah, India on 25 November 1759 during the Seven Years' War between a force of British ...

, forcing them to withdraw. The British engaged and defeated the ships the Dutch used to deliver the troops in a separate naval battle on 24 November. Thus Clive avenged the massacre of Amboyna – the occasion when he wrote his famous letter; "Dear Forde, fight them immediately; I will send you the order of council to-morrow".

Meanwhile, Clive improved the organisation and drill of the sepoy army, after a European model, and enlisted into it many Muslims from upper regions of the Mughal Empire. He re-fortified Calcutta. In 1760, after four years of hard labour, his health gave way and he returned to England. "It appeared", wrote a contemporary on the spot, "as if the soul was departing from the Government of Bengal". He had been formally made Governor of Bengal by the Court of Directors at a time when his nominal superiors in Madras sought to recall him to their help there. But he had discerned the importance of the province even during his first visit to its rich delta, mighty rivers and teeming population. Clive selected some able subordinates, notably a young Warren Hastings

Warren Hastings (6 December 1732 – 22 August 1818) was a British colonial administrator, who served as the first Governor of the Presidency of Fort William (Bengal), the head of the Supreme Council of Bengal, and so the first Governor-General ...

, who, a year after Plassey, was made Resident

Resident may refer to:

People and functions

* Resident minister, a representative of a government in a foreign country

* Resident (medicine), a stage of postgraduate medical training

* Resident (pharmacy), a stage of postgraduate pharmaceuti ...

at the Nawab's court.

The long-term outcome of Plassey was to place a very heavy revenue burden upon Bengal. The company sought to extract the maximum revenue possible from the peasantry to fund military campaigns, and corruption was widespread amongst its officials. Mir Jafar was compelled to engage in extortion on a vast scale in order to replenish his treasury, which had been emptied by the company's demand for an indemnity of 2.8 '' crores'' of rupees (£3 million).

Return to Great Britain

In 1760, the 35-year-old Clive returned to Great Britain with a fortune of at least £300,000 () and thequit-rent

Quit rent, quit-rent, or quitrent is a tax or land tax imposed on occupants of freehold or leased land in lieu of services to a higher landowning authority, usually a government or its assigns.

Under feudal law, the payment of quit rent (Latin ...

of £27,000 () a year. He financially supported his parents and sisters, while also providing Major Lawrence, the commanding officer who had early encouraged his military genius, with a stipend

A stipend is a regular fixed sum of money paid for services or to defray expenses, such as for scholarship, internship, or apprenticeship. It is often distinct from an income or a salary because it does not necessarily represent payment for work p ...

of £500 () a year. In the five years of his conquests and administration in Bengal, the young man had crowded together a succession of exploits that led Lord Macaulay

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, (; 25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was a British historian and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster-General between 1846 and 1 ...

, in what that historian termed his "flashy" essay on the subject, to compare him to Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

, declaring that " livegave peace, security, prosperity and such liberty as the case allowed of to millions of Indians, who had for centuries been the prey of oppression, while Napoleon's career of conquest was inspired only by personal ambition, and the absolutism he established vanished with his fall." Macaulay's ringing endorsement of Clive seems more controversial today, as some would argue that Clive's ambition and desire for personal gain set the tone for the administration of Bengal until the Permanent Settlement

The Permanent Settlement, also known as the Permanent Settlement of Bengal, was an agreement between the East India Company and Bengali landlords to fix revenues to be raised from land that had far-reaching consequences for both agricultural met ...

30 years later. The immediate consequence of Clive's victory at Plassey was an increase in the revenue demand on Bengal by at least 20%, which led to considerable hardship for the rural population, particularly during the famine of 1770.

During the three years that Clive remained in Great Britain, he sought a political position, chiefly that he might influence the course of events in India, which he had left full of promise. He had been well received at court, was elevated to the peerage as Baron Clive of Plassey

Palashi or Plassey ( bn, পলাশী, Palāśī, translit-std=ISO, , ) is a village on the east bank of Bhagirathi River, located approximately 50 kilometres north of the city of Krishnanagar in Kaliganj CD Block in the Nadia Distric ...

, County Clare

County Clare ( ga, Contae an Chláir) is a county in Ireland, in the Southern Region and the province of Munster, bordered on the west by the Atlantic Ocean. Clare County Council is the local authority. The county had a population of 118,81 ...

; had bought estates, and returned a few friends as well as himself to the House of Commons. Clive was MP for Shrewsbury from 1761

Events

January–March

* January 14 – Third Battle of Panipat: Ahmad Shah Durrani and his coalition decisively defeat the Maratha Confederacy, and restore the Mughal Empire to Shah Alam II.

* January 16 – Siege of Pond ...

until his death. He was allowed to sit in the Commons because his peerage was Irish. He was also elected Mayor of Shrewsbury for 1762–63. The non-graduate Clive received an honorary degree as DCL from Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

in 1760, and in 1764 he was appointed Knight of the Order of the Bath.

Clive set himself to reform the home system of the East India Company, and began a bitter dispute with the chairman of the Court of Directors, Laurence Sulivan

Laurence Sulivan (1713–1786) was an Anglo-Irish politician, Member of Parliament first for Taunton in 1762 and then for Ashburton in 1768. He was also Chairman of the British East India Company.

Sulivan was born in Ireland and moved to wo ...

, whom he defeated in the end. In this he was aided by the news of reverses in Bengal. Mir Jafar had finally rebelled over payments to British officials, and Clive's successor had put Qasim Ali Khan, Mir Jafar's son-in-law upon the ''musnud'' (throne). After a brief tenure, Mir Qasim

Mir Qasim ( bn, মীর কাশিম; died 8 May 1777) was the Nawab of Bengal from 1760 to 1763. He was installed as Nawab with the support of the British East India Company, replacing Mir Jafar, his father-in-law, who had himself been su ...

had fled, ordering Walter Reinhardt Sombre

Walter Reinhardt Sombre (born Walter Reinhardt or Reinert; ) was a European adventurer and mercenary in India from the 1760s.

Early life

Sombre is thought to have been born in Strasbourg or Treves. His birthplace and nationality, being given in v ...

(known to the Muslims as Sumru), a Swiss mercenary of his, to butcher the garrison of 150 British at Patna, and had disappeared under the protection of his brother, the Viceroy of Awadh. The whole company's service, civil and military, had become mired in corruption, demoralised by gifts and by the monopoly of inland and export trade, to such an extent that the Indians were pauperised, and the company was plundered of the revenues Clive had acquired. For this Clive himself must bear much responsibility, as he had set a very poor example during his tenure as Governor. Nevertheless, the Court of Proprietors, forced the Directors to hurry Lord Clive to Bengal with the double powers of Governor and Commander-in-Chief.

Third journey to India

On 3 May 1765 Clive landed at Calcutta to learn that Mir Jafar had died, leaving him personally £70,000 (). Mir Jafar was succeeded by his son-in-law Kasim Ali, though not before the government had been further demoralised by taking £100,000 () as a gift from the new Nawab; while Kasim Ali had induced not only the viceroy of Awadh, but the emperor of Delhi himself, to invade

On 3 May 1765 Clive landed at Calcutta to learn that Mir Jafar had died, leaving him personally £70,000 (). Mir Jafar was succeeded by his son-in-law Kasim Ali, though not before the government had been further demoralised by taking £100,000 () as a gift from the new Nawab; while Kasim Ali had induced not only the viceroy of Awadh, but the emperor of Delhi himself, to invade Bihar

Bihar (; ) is a state in eastern India. It is the 2nd largest state by population in 2019, 12th largest by area of , and 14th largest by GDP in 2021. Bihar borders Uttar Pradesh to its west, Nepal to the north, the northern part of West ...

. At this point a mutiny in the Bengal army occurred, which was a grim precursor of the Indian rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the fo ...

, but on this occasion it was quickly suppressed by blowing the sepoy ringleader from a gun. Major Munro, "the Napier of those times", scattered the united armies on the hard-fought field of Buxar

Buxar is a nagar parishad city in the state of Bihar, India bordering Uttar Pradesh. It is the headquarters of the eponymous Buxar district, as well as the headquarters of the community development block of Buxar, which also contains the ce ...

. The emperor, Shah Alam II

Shah Alam II (; 25 June 1728 – 19 November 1806), also known by his birth name Ali Gohar (or Ali Gauhar), was the seventeenth Mughal Emperor and the son of Alamgir II. Shah Alam II became the emperor of a crumbling Mughal empire. His powe ...

, detached himself from the league, while the Awadh viceroy threw himself on the mercy of the British.

Hindustan

''Hindūstān'' ( , from '' Hindū'' and ''-stān''), also sometimes spelt as Hindōstān ( ''Indo-land''), along with its shortened form ''Hind'' (), is the Persian-language name for the Indian subcontinent that later became commonly used by ...

, or Upper India, what he had accomplished in Bengal. He might have secured what is now called Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh (; , 'Northern Province') is a state in northern India. With over 200 million inhabitants, it is the most populated state in India as well as the most populous country subdivision in the world. It was established in 1950 ...

, and have rendered unnecessary the campaigns of Wellesley and Lake

A lake is an area filled with water, localized in a basin, surrounded by land, and distinct from any river or other outlet that serves to feed or drain the lake. Lakes lie on land and are not part of the ocean, although, like the much large ...

. But he believed he had other work in the exploitation of the revenues and resources of rich Bengal itself, making it a base from which British India would afterwards steadily grow. Hence he returned to the Awadh viceroy all his territory save the provinces of Allahabad and Kora, which he presented to the weak emperor.

Mughal ''Firman''

In return for the Awadhian provinces Clive secured from the emperor one of the most important documents in British history in India, effectively granting title of Bengal to Clive. It appears in the records as " firman from the King Shah Aalum, granting the diwani rights of Bengal, Bihar andOdisha

Odisha (English: , ), formerly Orissa ( the official name until 2011), is an Indian state located in Eastern India. It is the 8th largest state by area, and the 11th largest by population. The state has the third largest population of ...

to the Company 1765." The date was 12 August 1765, the place Benares

Varanasi (; ; also Banaras or Benares (; ), and Kashi.) is a city on the Ganges river in northern India that has a central place in the traditions of pilgrimage, death, and mourning in the Hindu world.

*

*

*

* The city has a syncretic tra ...