London Debating Societies on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Debating societies emerged in London in the early eighteenth century, and were a prominent feature of society until the end of the century. The origins of the debating societies are not certain, but by the mid-18th century, London fostered an active debating culture. Topics ranged from current events and governmental policy, to love and marriage, and the societies welcomed participants from all genders and all social backgrounds, exemplifying the enlarged

The Enlightenment is a period of history identified with the eighteenth century. Arising throughout Europe, Enlightenment philosophy emphasised

The Enlightenment is a period of history identified with the eighteenth century. Arising throughout Europe, Enlightenment philosophy emphasised

The "British elocutionary movement" is linked to Thomas Sheridan, an Irish actor turned orator and author who was an avid proponent of educational reform. A contemporary of

The "British elocutionary movement" is linked to Thomas Sheridan, an Irish actor turned orator and author who was an avid proponent of educational reform. A contemporary of

Regardless of when the debating societies formally began, they were firmly established in London society by the 1770s. At this time, many of the societies began to move out of the pubs and taverns in which they had initially met, and into larger and more sophisticated rooms and halls. Tea, coffee, and sometimes sweets and ice cream replaced the alcohol of the taverns, and the admission fee also increased. The new setting and atmosphere contributed to an overall more respectable audience in line with the Enlightened ideal of politeness. Mary Thale notes that, while the usual admission of a sixpence was not insubstantial, it was considerably less than the price of attending a lecture or the theatre. The debating societies were therefore more accessible to members of the working, middle, and lower classes, truly bringing the "rational entertainment" so favoured during the Enlightenment into the public sphere. Questions and topics for debate, as well as the outcomes of the debates, were advertised in the many London newspapers that flourished during the time, again linking the debating societies with the public sphere.

Andrew emphasises the year 1780 as pivotal in the history of the debating societies. The Morning Chronicle announced on 27 March: As the more respectable locales became a firmly entrenched element of the societies, the size of the audiences grew considerably. The move away from pubs and taverns likely contributed to an increased presence of women in the societies, and they were formally invited to take part in debate. In 1780, 35 differently named societies advertised and hosted debates for anywhere between 650 and 1200 people. The question for debate was introduced by a president or moderator who proceeded to regulate the discussion. Speakers were given set amounts of time to argue their point of view, and, at the end of the debate, a vote was taken to determine a decision or adjourn the question for further debate. Speakers were not permitted to slander or insult other speakers, or diverge from the topic at hand, again illustrating the value placed on politeness.

Another feature of London debating societies was the combination of other types of entertainment with the debates. Music, drama, and visual art were sometimes included in the evening's schedule. An advertisement in the London Courant for the University of Rational Amusement on 28 March 1780 read:"Horns and clarinets will assist to fill up the vacancy of time previous to the commencement of the debate." Similarly, an 3 April advertisement in the Morning Chronicle for The Oratorical Hall noted: "The Hall will be grandly illuminated, and the Company entertained with Music until the Debate commences." Some societies also contributed part of the evening's profits to charity. Andrew notes a donation of La Belle Assemblee for "the relief of sufferers from the fire at Cavendish Square."

Overall, the London debating societies represent how British society of the eighteenth century fostered open political, social, and democratic discussion, and exemplify the public sphere.

Regardless of when the debating societies formally began, they were firmly established in London society by the 1770s. At this time, many of the societies began to move out of the pubs and taverns in which they had initially met, and into larger and more sophisticated rooms and halls. Tea, coffee, and sometimes sweets and ice cream replaced the alcohol of the taverns, and the admission fee also increased. The new setting and atmosphere contributed to an overall more respectable audience in line with the Enlightened ideal of politeness. Mary Thale notes that, while the usual admission of a sixpence was not insubstantial, it was considerably less than the price of attending a lecture or the theatre. The debating societies were therefore more accessible to members of the working, middle, and lower classes, truly bringing the "rational entertainment" so favoured during the Enlightenment into the public sphere. Questions and topics for debate, as well as the outcomes of the debates, were advertised in the many London newspapers that flourished during the time, again linking the debating societies with the public sphere.

Andrew emphasises the year 1780 as pivotal in the history of the debating societies. The Morning Chronicle announced on 27 March: As the more respectable locales became a firmly entrenched element of the societies, the size of the audiences grew considerably. The move away from pubs and taverns likely contributed to an increased presence of women in the societies, and they were formally invited to take part in debate. In 1780, 35 differently named societies advertised and hosted debates for anywhere between 650 and 1200 people. The question for debate was introduced by a president or moderator who proceeded to regulate the discussion. Speakers were given set amounts of time to argue their point of view, and, at the end of the debate, a vote was taken to determine a decision or adjourn the question for further debate. Speakers were not permitted to slander or insult other speakers, or diverge from the topic at hand, again illustrating the value placed on politeness.

Another feature of London debating societies was the combination of other types of entertainment with the debates. Music, drama, and visual art were sometimes included in the evening's schedule. An advertisement in the London Courant for the University of Rational Amusement on 28 March 1780 read:"Horns and clarinets will assist to fill up the vacancy of time previous to the commencement of the debate." Similarly, an 3 April advertisement in the Morning Chronicle for The Oratorical Hall noted: "The Hall will be grandly illuminated, and the Company entertained with Music until the Debate commences." Some societies also contributed part of the evening's profits to charity. Andrew notes a donation of La Belle Assemblee for "the relief of sufferers from the fire at Cavendish Square."

Overall, the London debating societies represent how British society of the eighteenth century fostered open political, social, and democratic discussion, and exemplify the public sphere.

The content of the debates was incredibly diverse, and surprisingly progressive. Political topics that directly challenged governmental policies were common, as were social topics that called into question the authority of traditional institutions such as the church and the family. The gender divide was one of the most often addressed issues, and the simple presence of women in the societies certainly lead to a heightened gender consciousness. Commerce and education were also addressed by the debating societies.

It is important to remember that debating societies were run as commercial enterprises, and were designed to turn a profit for their managers. Thus, the content of the debates was not only informed by political or social sentiment, but by simple entertainment value or interest as well. In general, the debating topics of the 1770s and 1780s were more political and even radical, while the topics of the 1790s up to the decline and disappearance of the societies became less controversial. Donna Andrew's collation of newspaper advertisements from the period of 1776 to 1799 is the seminal resource for investigation of the content of the debating societies.

The content of the debates was incredibly diverse, and surprisingly progressive. Political topics that directly challenged governmental policies were common, as were social topics that called into question the authority of traditional institutions such as the church and the family. The gender divide was one of the most often addressed issues, and the simple presence of women in the societies certainly lead to a heightened gender consciousness. Commerce and education were also addressed by the debating societies.

It is important to remember that debating societies were run as commercial enterprises, and were designed to turn a profit for their managers. Thus, the content of the debates was not only informed by political or social sentiment, but by simple entertainment value or interest as well. In general, the debating topics of the 1770s and 1780s were more political and even radical, while the topics of the 1790s up to the decline and disappearance of the societies became less controversial. Donna Andrew's collation of newspaper advertisements from the period of 1776 to 1799 is the seminal resource for investigation of the content of the debating societies.

In 1791, the society at Coachmaker's Hall debated the question, "Is not the war now carrying on in India disgraceful to this country, injurious to its political interest, and ruinous to the commercial interests of the Company?" on two separate occasions, deciding almost unanimously that "war is unjust, disgraceful and ruinous." The society followed that debate with the question, "Would it be most for the interest of this country, that the territorial possessions in India should still continue in the hands of the present East India Company, be taken under the sole and immediate direction of the Legislature, or be relinquished to the native inhabitants of the country?" for two weeks as well.

Events on the continent, such as the

In 1791, the society at Coachmaker's Hall debated the question, "Is not the war now carrying on in India disgraceful to this country, injurious to its political interest, and ruinous to the commercial interests of the Company?" on two separate occasions, deciding almost unanimously that "war is unjust, disgraceful and ruinous." The society followed that debate with the question, "Would it be most for the interest of this country, that the territorial possessions in India should still continue in the hands of the present East India Company, be taken under the sole and immediate direction of the Legislature, or be relinquished to the native inhabitants of the country?" for two weeks as well.

Events on the continent, such as the

Perhaps one of the most interesting and radical themes of the debating societies was the continued and varied debate on men and women and their interactions. The presence of women in the societies meant that the debates had a chance of accurately representing contemporary women's own viewpoints on their role in society, not simply those of men, making the debates a significant marker of popular thought and opinion.

The Oratorical Academy at Mitre Tavern asked, "Can friendship subsist between the two sexes, without the passion of love?" In discussing marriage, La Belle Assemblée, a women's only society, asked, "In the failure of a mutual affection in the married state, which is to be preferred, to love or be loved?" The New Westminster Forum questioned, "Which is the more disagreeable, a jealous or a scolding Wife?" The society at Coachmaker's Hall debated, "Is not the deliberate Seduction of the Fair, with an intention to desert, under all circumstances, equal to murder?" American John Neal in the mid 1820s proposed the resolve, "That the intellectual powers of the two sexes are equal."

Though the decision was negative in this case, the question indicated the seriousness with which these questions were approached. Other questions seem to reveal a genuine interest in understanding relationships: "Which is to be preferred in the choice of a wife, beauty without fortune, or fortune without beauty?" and "Is it the love of the mental or personal charms of the fair sex, that is more likely to induce men to enter into the married state?"

These questions of love and marriage, and happiness in marriage, indicate how the social climate was changing, allowing for such discussions of gender relations. The societies were, in essence, part of a complete redefinition of gender roles that was underway in the late eighteenth century and into the nineteenth.

Perhaps one of the most interesting and radical themes of the debating societies was the continued and varied debate on men and women and their interactions. The presence of women in the societies meant that the debates had a chance of accurately representing contemporary women's own viewpoints on their role in society, not simply those of men, making the debates a significant marker of popular thought and opinion.

The Oratorical Academy at Mitre Tavern asked, "Can friendship subsist between the two sexes, without the passion of love?" In discussing marriage, La Belle Assemblée, a women's only society, asked, "In the failure of a mutual affection in the married state, which is to be preferred, to love or be loved?" The New Westminster Forum questioned, "Which is the more disagreeable, a jealous or a scolding Wife?" The society at Coachmaker's Hall debated, "Is not the deliberate Seduction of the Fair, with an intention to desert, under all circumstances, equal to murder?" American John Neal in the mid 1820s proposed the resolve, "That the intellectual powers of the two sexes are equal."

Though the decision was negative in this case, the question indicated the seriousness with which these questions were approached. Other questions seem to reveal a genuine interest in understanding relationships: "Which is to be preferred in the choice of a wife, beauty without fortune, or fortune without beauty?" and "Is it the love of the mental or personal charms of the fair sex, that is more likely to induce men to enter into the married state?"

These questions of love and marriage, and happiness in marriage, indicate how the social climate was changing, allowing for such discussions of gender relations. The societies were, in essence, part of a complete redefinition of gender roles that was underway in the late eighteenth century and into the nineteenth.

After their peak in 1780, the London debating societies generally declined in number and frequency, rising again slightly around the late 1780s, only to fall off completely by the end of the century. The French Revolution began in 1789 and Thale notes that, Understandably fearful of the ramifications of such an example just across the English Channel, the British government began to crack down on the debating societies. Without specific legislation to block the meetings, the government often intimidated or threatened the landlords of the venues where debates were held, who in turn closed the buildings to the public. 1792 saw the formation of the

After their peak in 1780, the London debating societies generally declined in number and frequency, rising again slightly around the late 1780s, only to fall off completely by the end of the century. The French Revolution began in 1789 and Thale notes that, Understandably fearful of the ramifications of such an example just across the English Channel, the British government began to crack down on the debating societies. Without specific legislation to block the meetings, the government often intimidated or threatened the landlords of the venues where debates were held, who in turn closed the buildings to the public. 1792 saw the formation of the

*Andrew, Donna T. "Popular Culture and Public Debate: London 1780," ''The Historical Journal'' 39, no. 2 (June 1996): 405–23. *Benzie, W. ''The Dublin Orator: Thomas Sheridan's Influence on Eighteenth-century Rhetoric and Belles Lettres.'' Menston: Scolar Press Limited, 1972. *Cowan, Brian William. ''The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse.'' New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005. *Goring, Paul. ''The Rhetoric of Sensibility in Eighteenth-Century Culture.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. *McCalman, Iain. "Ultra-Radicalism and Convivial Debating-Clubs in London, 1795–1838." ''The English Historical Review'' 102, no. 403 (April 1987): 309–33. *Munck, Thomas. ''The Enlightenment: A Comparative Social History 1721–1794.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. * John Neal (writer), Neal, Johnbr>''Wandering Recollections of a Somewhat Busy Life.''

Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1869. *Thale, Mary. "London Debating Societies in the 1790s." ''The Historical Journal'' 32, no. 1 (March 1989): 57–86. *Timbs, John. ''Clubs and Club Life in London.'' Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1967. First published 1866 by Chatto and Windus, Publishers, London. *Van Horn Melton, James. ''The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

public sphere

The public sphere (german: Öffentlichkeit) is an area in social life where individuals can come together to freely discuss and identify societal problems, and through that discussion influence political action. A "Public" is "of or concerning the ...

of the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

.

At the end of the century, the political environment created by the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

led to the tightening of governmental restrictions. The debating societies declined, and they virtually disappeared by the beginning of the nineteenth century. However, a select few societies survived to the present day, and new societies formed in recent years have been boosted by promotion via the internet and social media, giving debating in London a new lease on life.

Scholarship on London's debating societies is hindered by the lack of records left by the societies, but the work of historian Donna T. Andrew, among others, has contributed to the field.

Debating Societies and the Enlightenment

:''See main article'':Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

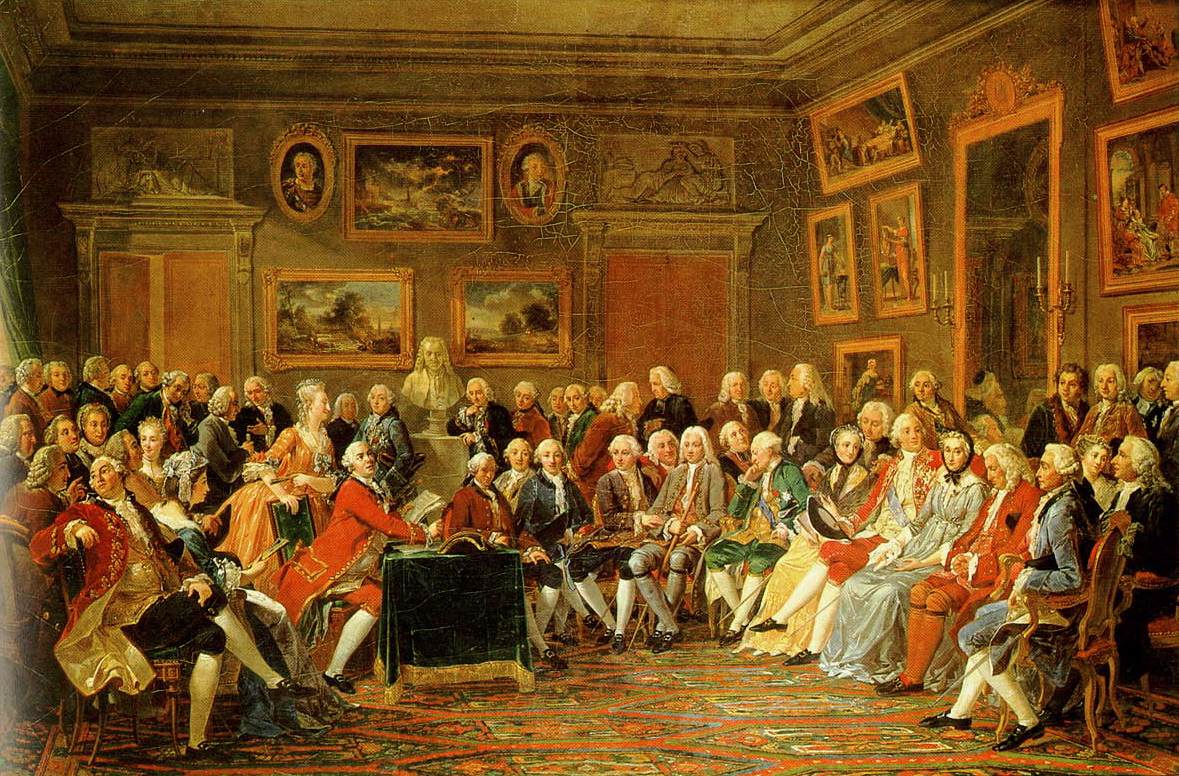

The Enlightenment is a period of history identified with the eighteenth century. Arising throughout Europe, Enlightenment philosophy emphasised

The Enlightenment is a period of history identified with the eighteenth century. Arising throughout Europe, Enlightenment philosophy emphasised reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, lang ...

as the foremost source of authority in all matters, and was simultaneously linked to increased secularisation

In sociology, secularization (or secularisation) is the transformation of a society from close identification with religious values and institutions toward non-religious values and secular institutions. The ''secularization thesis'' expresses the ...

and often political upheaval. The most obvious example of this link is the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

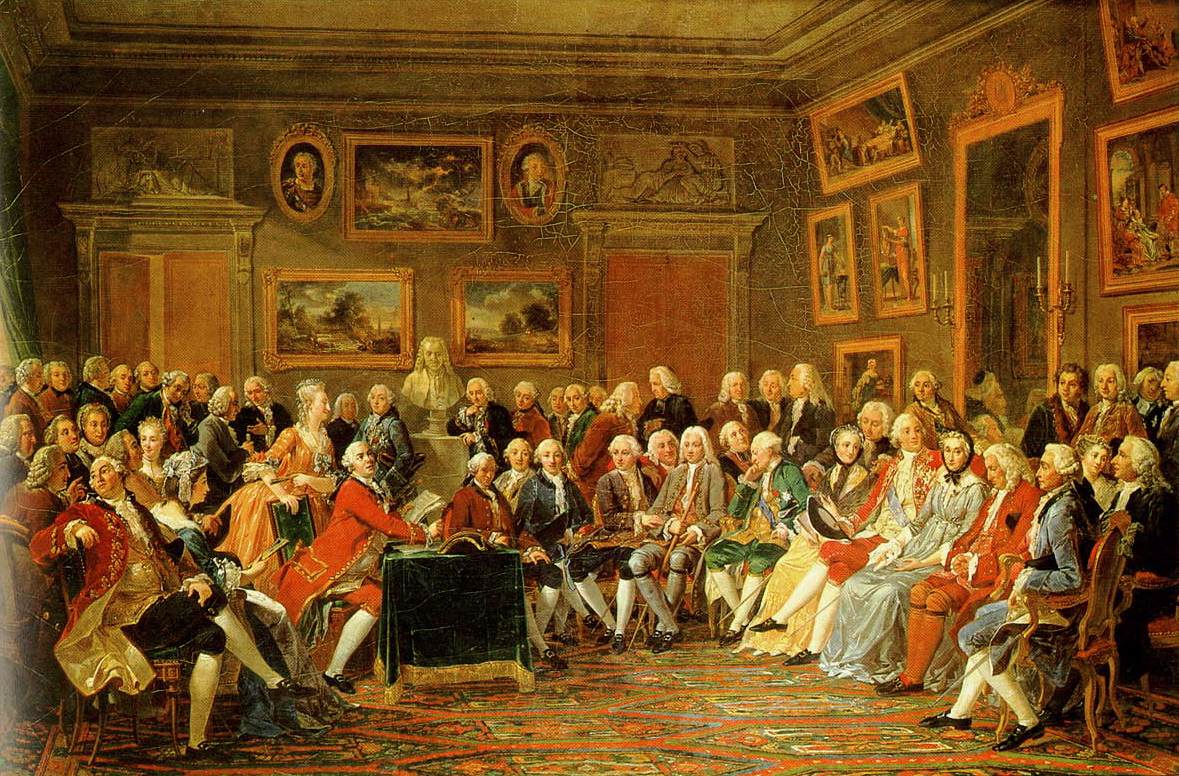

of 1789. The Enlightenment in France is tightly associated with the rise of the salons and the academies, institutions which have been intensely studied by many notable historians. The English Enlightenment has historically been largely associated with the rise of coffeehouse

A coffeehouse, coffee shop, or café is an establishment that primarily serves coffee of various types, notably espresso, latte, and cappuccino. Some coffeehouses may serve cold drinks, such as iced coffee and iced tea, as well as other non-ca ...

culture, a topic also investigated by many historians. More recent scholarship has identified early elements of the Enlightenment in other European countries, such as the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

.

The Public Sphere

While the Enlightenment was an incredibly diverse phenomenon that varied from country to country, one aspect common to each country was the rise of the "public sphere". The concept of the public sphere was articulated byJürgen Habermas

Jürgen Habermas (, ; ; born 18 June 1929) is a German social theorist in the tradition of critical theory and pragmatism. His work addresses communicative rationality and the public sphere.

Associated with the Frankfurt School, Habermas's wo ...

, a German sociologist and philosopher. Habermas saw in the eighteenth century the rise of new realm of communication that emphasised new areas of debate, as well as a surge in print culture. This new arena, which Habermas termed the "bourgeois public sphere," was characterised as separate from traditional authorities and accessible to all people, and could therefore act as a platform for criticism and the development of new ideas and philosophy. While the degree to which the salons and academies of France can be considered part of the public sphere has been questioned, the debating societies of London are undoubtedly part of the Enlightened public sphere. The relatively unrestricted print industry of late seventeenth century England, as well as the Triennial Act of 1694 that required elections of the British Parliament at least every three years, fostered a comparatively active political climate in eighteenth century England, in which the debating societies were able to flourish.

Origins of debating societies in London

While there were comparable societies in other parts of Europe, as well as in other British cities, London was home to the largest number of independent debate societies throughout all of the eighteenth century. This prominence was largely due to prior existence of clubs that had been created for various other reasons, the concentration of population in the capital, as well as other Enlightened philosophical developments.Philosophical origins

The Enlightenment saw an increasing emphasis on the concept of "politeness". Perhaps most obvious in the salons of Paris, polite discourse was seen as a way for the rising middle class to access the previously unattainable social status of the upper classes. In England, politeness came to be associated withelocution

Elocution is the study of formal speaking in pronunciation, grammar, style, and tone as well as the idea and practice of effective speech and its forms. It stems from the idea that while communication is symbolic, sounds are final and compelli ...

. Paul Goring argues that "elocutionary movement" arose initially from a desire to make sermons more interesting and attainable. He notes that periodicals such as ''The Tatler'' and ''The Spectator'', the quintessential reflections of British public opinion, often criticised Anglican ministers for their oratory. Goring also points out that, in spite of the burgeoning print culture of the eighteenth century, oratory was still the most effective way of communicating with a public that was basically only half literate in 1750.

The "British elocutionary movement" is linked to Thomas Sheridan, an Irish actor turned orator and author who was an avid proponent of educational reform. A contemporary of

The "British elocutionary movement" is linked to Thomas Sheridan, an Irish actor turned orator and author who was an avid proponent of educational reform. A contemporary of Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet, and Anglican cleric who became Dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Du ...

, Sheridan began his public career with the publishing of ''British Education; Or, The Source of the Disorders of Great Britain'' in 1756, which attacked the current practices of education that continued to emphasise Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

literature, and argued for a new system that instead concentrated on the study of English and elocution. Understandably, Sheridan's work was controversial, and his popularity in London society began to climb.

In 1762, Sheridan published ''A Course of Lectures on Elocution,'' a collection of lectures he had given throughout the previous years. These lectures insisted upon a standardised English pronunciation, and emphasised the public speaker as a powerful agent of cultural change. Sheridan also contended that improved oratory would contribute to the stability and strength of the nation of Great Britain, a relatively new ideological concept that reflected the growing interest in nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

. Sheridan was a noted public speaker in his own right, and his lectures on oratory were well attended throughout Britain. Subscribers to Sheridan's lectures at clubs, universities, and theatres paid a substantial amount (one guinea) to hear the Dublin orator; these lectures, which coincided with the debating societies, reflect the growing interest in public speaking during the eighteenth-century.

Structural origins

Along with the growing emphasis on politeness and elocution, Donna Andrew suggests four main institutional precursors of the formal debating societies of later eighteenth-century London. First of these were convivial clubs of fifty or more men who met weekly in pubs to discuss politics and religion. An example of this type of club was the Robin Hood Society. The nineteenth century author John Timbs notes: The "baker" was Caleb Jeacocke, president for 19 years. By the 1730s, the Robin Hood Society was flourishing, and by the 1740s was joined by a similar society known as the Queen's Arms. Other possible origins of the debating societies were the "mooting clubs" established by law students to practice rhetoric and the skills needed for the courtroom, and the "spouting clubs" designed for young actors to practice their delivery. The last possible forerunner of the debating societies given by Andrew is the Oratory of John Henley, commonly known as "Orator Henley". Originally a preacher in the Anglican church, Henley founded his Oratory in 1726 with the principal purpose of "reforming the manner in which such public presentations should be performed." He made extensive use of the print industry to advertise the events of his Oratory, making it an omnipresent part of the London public sphere. Henley was also instrumental in constructing the space of the debating club: he added two platforms to his room in the Newport district of London to allow for the staging of debates, and structured the entrances to allow for the collection of admission. These changes were further implemented when Henley moved his enterprise toLincoln's Inn Fields

Lincoln's Inn Fields is the largest public square in London. It was laid out in the 1630s under the initiative of the speculative builder and contractor William Newton, "the first in a long series of entrepreneurs who took a hand in develo ...

. The public was now willing to pay to be entertained, and Henley exploited this increasing commercialisation of British society. Indeed, commercial interests continued to inform and shape London debating societies in the years following Henley's Oratory. Henley's addresses initially focused on elocution and religious subject matter, but became increasingly directed towards entertainment. Andrew also notes the influence of entertainment on the early debating societies. She cites The Temple of Taste, a venue advertised as including music, poetry, lectures, and debate, as another possible precursor to the more formal debating societies of the later eighteenth century.

In his research on British coffeehouse culture, Brian Cowan briefly examines the Rota Club The Rota Club was a debate society of learned gentlemen who debated republican ideology in London between November 1659 and February 1660. The Club was founded and dominated by James Harrington. It began during the English Interregnum (1649–1660 ...

, a group founded by republican James Harrington in 1659 that met in Miles' Coffeehouse in the New Palace Yard

New Palace Yard is a yard (area of grounds) northwest of the Palace of Westminster in Westminster, London, England. It is part of the grounds not open to the public. However, it can be viewed from the two adjoining streets, as a result of Edwa ...

. Attended by Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys (; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English diarist and naval administrator. He served as administrator of the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament and is most famous for the diary he kept for a decade. Pepys had no mariti ...

and John Aubrey

John Aubrey (12 March 1626 – 7 June 1697) was an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He is perhaps best known as the author of the '' Brief Lives'', his collection of short biographical pieces. He was a pioneer archaeologist ...

, among other notables, the Rota club was designed to debate and discuss the politics of the time. Admission was required, and it was definitely aimed towards the "virtuosi" of society, but it is definitely possible that the Rota inspired the later debating societies. Timbs calls the Rota "a kind of debating society for the dissemination of Republican opinions."

While it is impossible to determine if one or more of these institutions directly engendered the debating societies of later 18th century London, their existence indicates the tendency toward elocution, public debate, and politics that was certainly present in the British mindset.

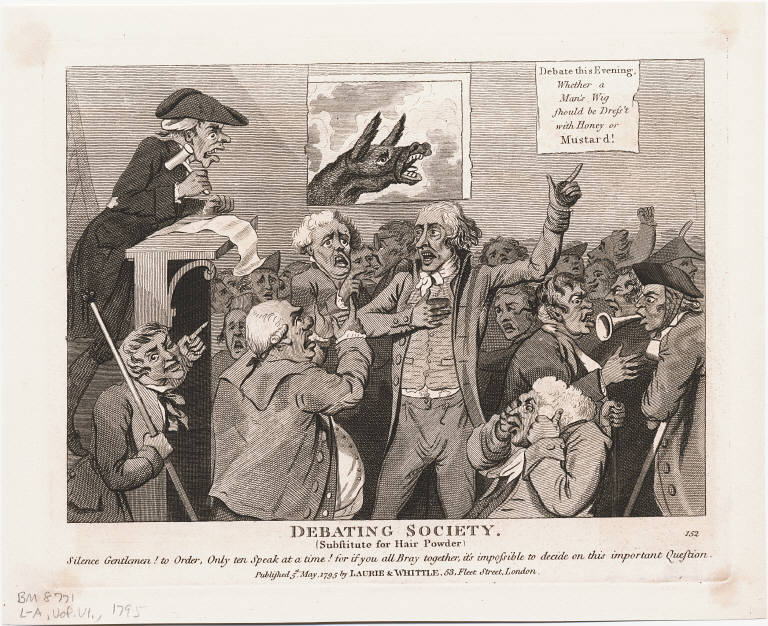

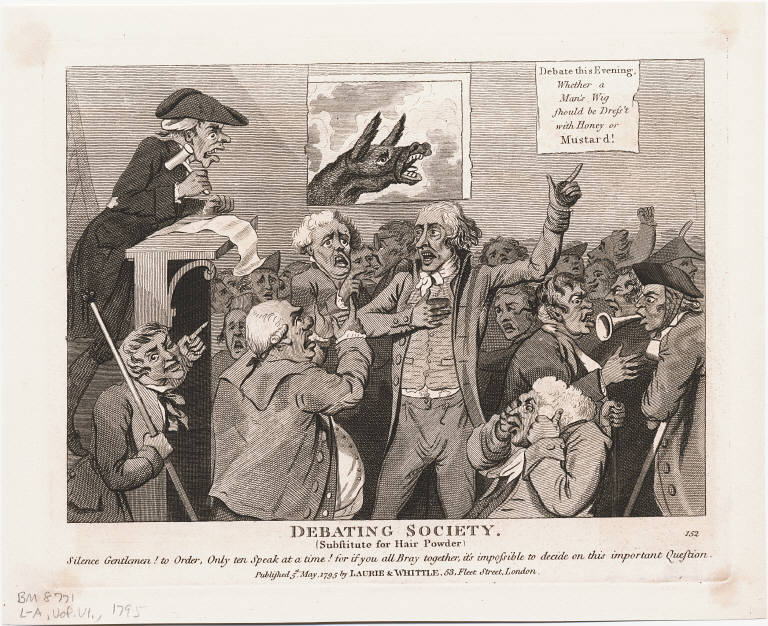

Characteristics

Regardless of when the debating societies formally began, they were firmly established in London society by the 1770s. At this time, many of the societies began to move out of the pubs and taverns in which they had initially met, and into larger and more sophisticated rooms and halls. Tea, coffee, and sometimes sweets and ice cream replaced the alcohol of the taverns, and the admission fee also increased. The new setting and atmosphere contributed to an overall more respectable audience in line with the Enlightened ideal of politeness. Mary Thale notes that, while the usual admission of a sixpence was not insubstantial, it was considerably less than the price of attending a lecture or the theatre. The debating societies were therefore more accessible to members of the working, middle, and lower classes, truly bringing the "rational entertainment" so favoured during the Enlightenment into the public sphere. Questions and topics for debate, as well as the outcomes of the debates, were advertised in the many London newspapers that flourished during the time, again linking the debating societies with the public sphere.

Andrew emphasises the year 1780 as pivotal in the history of the debating societies. The Morning Chronicle announced on 27 March: As the more respectable locales became a firmly entrenched element of the societies, the size of the audiences grew considerably. The move away from pubs and taverns likely contributed to an increased presence of women in the societies, and they were formally invited to take part in debate. In 1780, 35 differently named societies advertised and hosted debates for anywhere between 650 and 1200 people. The question for debate was introduced by a president or moderator who proceeded to regulate the discussion. Speakers were given set amounts of time to argue their point of view, and, at the end of the debate, a vote was taken to determine a decision or adjourn the question for further debate. Speakers were not permitted to slander or insult other speakers, or diverge from the topic at hand, again illustrating the value placed on politeness.

Another feature of London debating societies was the combination of other types of entertainment with the debates. Music, drama, and visual art were sometimes included in the evening's schedule. An advertisement in the London Courant for the University of Rational Amusement on 28 March 1780 read:"Horns and clarinets will assist to fill up the vacancy of time previous to the commencement of the debate." Similarly, an 3 April advertisement in the Morning Chronicle for The Oratorical Hall noted: "The Hall will be grandly illuminated, and the Company entertained with Music until the Debate commences." Some societies also contributed part of the evening's profits to charity. Andrew notes a donation of La Belle Assemblee for "the relief of sufferers from the fire at Cavendish Square."

Overall, the London debating societies represent how British society of the eighteenth century fostered open political, social, and democratic discussion, and exemplify the public sphere.

Regardless of when the debating societies formally began, they were firmly established in London society by the 1770s. At this time, many of the societies began to move out of the pubs and taverns in which they had initially met, and into larger and more sophisticated rooms and halls. Tea, coffee, and sometimes sweets and ice cream replaced the alcohol of the taverns, and the admission fee also increased. The new setting and atmosphere contributed to an overall more respectable audience in line with the Enlightened ideal of politeness. Mary Thale notes that, while the usual admission of a sixpence was not insubstantial, it was considerably less than the price of attending a lecture or the theatre. The debating societies were therefore more accessible to members of the working, middle, and lower classes, truly bringing the "rational entertainment" so favoured during the Enlightenment into the public sphere. Questions and topics for debate, as well as the outcomes of the debates, were advertised in the many London newspapers that flourished during the time, again linking the debating societies with the public sphere.

Andrew emphasises the year 1780 as pivotal in the history of the debating societies. The Morning Chronicle announced on 27 March: As the more respectable locales became a firmly entrenched element of the societies, the size of the audiences grew considerably. The move away from pubs and taverns likely contributed to an increased presence of women in the societies, and they were formally invited to take part in debate. In 1780, 35 differently named societies advertised and hosted debates for anywhere between 650 and 1200 people. The question for debate was introduced by a president or moderator who proceeded to regulate the discussion. Speakers were given set amounts of time to argue their point of view, and, at the end of the debate, a vote was taken to determine a decision or adjourn the question for further debate. Speakers were not permitted to slander or insult other speakers, or diverge from the topic at hand, again illustrating the value placed on politeness.

Another feature of London debating societies was the combination of other types of entertainment with the debates. Music, drama, and visual art were sometimes included in the evening's schedule. An advertisement in the London Courant for the University of Rational Amusement on 28 March 1780 read:"Horns and clarinets will assist to fill up the vacancy of time previous to the commencement of the debate." Similarly, an 3 April advertisement in the Morning Chronicle for The Oratorical Hall noted: "The Hall will be grandly illuminated, and the Company entertained with Music until the Debate commences." Some societies also contributed part of the evening's profits to charity. Andrew notes a donation of La Belle Assemblee for "the relief of sufferers from the fire at Cavendish Square."

Overall, the London debating societies represent how British society of the eighteenth century fostered open political, social, and democratic discussion, and exemplify the public sphere.

Prominent Debating Societies

The number of debating societies is vast and difficult to track, as they frequently changed names and venues. The list that follows is select and by no means comprehensive. The names of the societies themselves, however, are useful in understanding their nature, how they were often linked to their location, and the way they were represented in London society. * The Athenian Society * Capel Court Debating Society * The Carlisle House School for Eloquence * City Debates * The Coachmaker's Hall Society *Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in neighbour ...

Forum

* Oratorical Hall

* Pantheon Society

* Religious Society of Old Portugal Street

* Society for Free Debate

* Society of Cogers

* Sylvan Debating Club

* The University for Rational Amusements

* The Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

Forum

;All Women's Societies

* La Belle Assemblee

* The Carlisle House Debates for Ladies Only

* The Female Congress

* The Female Parliament

Content of debates

The content of the debates was incredibly diverse, and surprisingly progressive. Political topics that directly challenged governmental policies were common, as were social topics that called into question the authority of traditional institutions such as the church and the family. The gender divide was one of the most often addressed issues, and the simple presence of women in the societies certainly lead to a heightened gender consciousness. Commerce and education were also addressed by the debating societies.

It is important to remember that debating societies were run as commercial enterprises, and were designed to turn a profit for their managers. Thus, the content of the debates was not only informed by political or social sentiment, but by simple entertainment value or interest as well. In general, the debating topics of the 1770s and 1780s were more political and even radical, while the topics of the 1790s up to the decline and disappearance of the societies became less controversial. Donna Andrew's collation of newspaper advertisements from the period of 1776 to 1799 is the seminal resource for investigation of the content of the debating societies.

The content of the debates was incredibly diverse, and surprisingly progressive. Political topics that directly challenged governmental policies were common, as were social topics that called into question the authority of traditional institutions such as the church and the family. The gender divide was one of the most often addressed issues, and the simple presence of women in the societies certainly lead to a heightened gender consciousness. Commerce and education were also addressed by the debating societies.

It is important to remember that debating societies were run as commercial enterprises, and were designed to turn a profit for their managers. Thus, the content of the debates was not only informed by political or social sentiment, but by simple entertainment value or interest as well. In general, the debating topics of the 1770s and 1780s were more political and even radical, while the topics of the 1790s up to the decline and disappearance of the societies became less controversial. Donna Andrew's collation of newspaper advertisements from the period of 1776 to 1799 is the seminal resource for investigation of the content of the debating societies.

Local politics and current events

One of the functions of the debating societies was as a forum for discussion of current events. The specificity of these debates can be seen in many examples. The Society for Free Debate took up the question, "Can Mr. Wilkes and his friend be justified in their present opposition to the Chamberlain?" on 26 April 1776, shortly after Wilkes introduced a parliamentary reform motion in theHouse of Commons of Great Britain

The House of Commons of Great Britain was the lower house of the Parliament of Great Britain between 1707 and 1801. In 1707, as a result of the Acts of Union of that year, it replaced the House of Commons of England and the third estate of the ...

. The Gazetteer reported the results of the debate: The Gordon riots

The Gordon Riots of 1780 were several days of rioting in London motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment. They began with a large and orderly protest against the Papists Act 1778, which was intended to reduce official discrimination against Briti ...

, anti-Catholic uprisings led by Lord George Gordon in 1780, were certainly a hot topic. The King's Arms Society, for Free and Candid Debate, asked, "Were the late Riots the effect of Accident or Design?" on 7 September, and, three months later, the Pantheon society debated "Can the conduct of Lord George Gordon respecting the Protestant Association be construed into High Treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

?"

In response to governmental controls placed on the debating societies in the 1790s, the Westminster Forum debated the question, "Is not the prohibition of public discussion, a violation of the spirit of a free constitution?" and, less than two weeks later, "Ought the Public Debating Societies and the late Meetings at Copenhagen House to be supported, as friendly to the Rights of the People; or suppressed, as the Causes of the Insult offered to His Majesty, and justifiable Reasons for introducing the Convention Bill?" Clearly the debating societies offer valuable insight into the political climate of the times.

Foreign policy and international events

Debates were not restricted to only local issues and events. Theforeign policy

A state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterally or through ...

of the British Empire was a key concern of the societies. The turbulent colonial relations of the time, including the break out of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, and continued conflict of the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

in India, provided ample fodder for the debating societies.

In February 1776, in the midst of the Boston campaign

The Boston campaign was the opening campaign of the American Revolutionary War, taking place primarily in the Province of Massachusetts Bay. The campaign began with the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, in which the local colon ...

, the Robin Hood Society asked, "Is it manifest that the Colonies affect independency?" As the war continued, so did the debates. In May, the Robin Hood again took on the colonial dispute and asked, "Is it now compatible with the dignity, interest, and duty of Great Britain, to treat with America on terms of accommodation?"

In 1791, the society at Coachmaker's Hall debated the question, "Is not the war now carrying on in India disgraceful to this country, injurious to its political interest, and ruinous to the commercial interests of the Company?" on two separate occasions, deciding almost unanimously that "war is unjust, disgraceful and ruinous." The society followed that debate with the question, "Would it be most for the interest of this country, that the territorial possessions in India should still continue in the hands of the present East India Company, be taken under the sole and immediate direction of the Legislature, or be relinquished to the native inhabitants of the country?" for two weeks as well.

Events on the continent, such as the

In 1791, the society at Coachmaker's Hall debated the question, "Is not the war now carrying on in India disgraceful to this country, injurious to its political interest, and ruinous to the commercial interests of the Company?" on two separate occasions, deciding almost unanimously that "war is unjust, disgraceful and ruinous." The society followed that debate with the question, "Would it be most for the interest of this country, that the territorial possessions in India should still continue in the hands of the present East India Company, be taken under the sole and immediate direction of the Legislature, or be relinquished to the native inhabitants of the country?" for two weeks as well.

Events on the continent, such as the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, were also discussed by the debating societies. After the storming of the Bastille in July 1789, the society at Coachmaker's Hall advertised a debate on "Whether the late Destruction of the Bastile, and the spirited Conduct of the French, do not prove that the general Opinion of their being possessed by a slavish Disposition was founded in National Prejudice?" Later that year, they again asked, "Is the Conduct of the French Assembly, in declaring the Possession of the Church to be the Property of the Nation, and their Care in providing for the inferior Clergy, worthy the Imitation of this Country?" Considering the eventual ramifications of the French Revolution, the early concern of the debating societies for events outside their own borders illustrates the progressive nature of the societies.

Commerce

The sphere of commerce was also of concern to the debating societies. From small scale local issues to commercial matters facing the Empire abroad, commercial topics for debate were abundant. In an advertisement for the society at Coachmaker's Hall, Parker's General Advertiser asked "Is the present mode of reducing the price of Bread consistent with fair trade, and likely to produce any public good?" The Robin Hood asked, "Whether a union with Ireland, similar to that with Scotland, would not be injurious to the commercial interests of Great Britain?" A 1780 debate at the Carlisle House School of Eloquence asked, "Whether it will be most conducive to the general good of the Community that the East India Company should be dissolved, or their Charter renewed?"Education

The debating societies also addressed matters of education. The rise of the middle class, the educational reforms spearheaded by people such as Thomas Sheridan, and increased commercialisation had thrown the ideals of a classical education into the realm of debate. As early as 1776, the Robin Hood Society debated the question, "Whether a liberal and learned Education is proper for a Person intended for commerce?" In 1779, the society at Coachmaker's Hall asked, "Is the system of education generally practiced in this nation, more favourable or unfavourable to liberty?" With the inclusion of women in the debating societies, the question of female education also came to the fore. The 3 April 1780 masquerade meeting of The Oratorical Hall in Spring Gardens asked, "Is it not detrimental to the world to restrain the female sex from the pursuit of classical and mathematical learning?" The advertisement also notes, "It is particularly hoped that Ladies will avail themselves of their masks and join in the debate." An October meeting of the society at Coachmaker's Hall investigated the question: "Would it not tend to the happiness of mankind, if women were allowed a scientific education?" Again, the progressive nature of the debating societies is shown through their content and attitude towards women.Religion

Along with the progressive and sometimes radical nature of the debates, traditional questions of religion remained a central issue for the debating societies. Society meetings that took place on Sunday often based discussion on a particular verse of scripture. For example, the 14 May 1780 Theological Question of the University for Rational Amusements was based on Romans 4:5: "But to him that worketh not, but believeth on him that justifieth the ungodly, his faith is counted for righteousness." Questions on religion's role in society and relationship to politics were also discussed. The Society for Free Debate asked, "Can a Roman Catholic, consistent with his religious principle, be a good subject to a Protestant Prince?" The Westminster Forum posed the question, "Are not the Bishops and others of the clergy who have denied their support and assistance to the Protestant Association, highly culpable in so doing?" Given the history of religious wars in Britain and the continued struggle between Protestants and Catholics, these debates were obviously quite significant to the London population.Love, sex, marriage, and relations between the sexes

Perhaps one of the most interesting and radical themes of the debating societies was the continued and varied debate on men and women and their interactions. The presence of women in the societies meant that the debates had a chance of accurately representing contemporary women's own viewpoints on their role in society, not simply those of men, making the debates a significant marker of popular thought and opinion.

The Oratorical Academy at Mitre Tavern asked, "Can friendship subsist between the two sexes, without the passion of love?" In discussing marriage, La Belle Assemblée, a women's only society, asked, "In the failure of a mutual affection in the married state, which is to be preferred, to love or be loved?" The New Westminster Forum questioned, "Which is the more disagreeable, a jealous or a scolding Wife?" The society at Coachmaker's Hall debated, "Is not the deliberate Seduction of the Fair, with an intention to desert, under all circumstances, equal to murder?" American John Neal in the mid 1820s proposed the resolve, "That the intellectual powers of the two sexes are equal."

Though the decision was negative in this case, the question indicated the seriousness with which these questions were approached. Other questions seem to reveal a genuine interest in understanding relationships: "Which is to be preferred in the choice of a wife, beauty without fortune, or fortune without beauty?" and "Is it the love of the mental or personal charms of the fair sex, that is more likely to induce men to enter into the married state?"

These questions of love and marriage, and happiness in marriage, indicate how the social climate was changing, allowing for such discussions of gender relations. The societies were, in essence, part of a complete redefinition of gender roles that was underway in the late eighteenth century and into the nineteenth.

Perhaps one of the most interesting and radical themes of the debating societies was the continued and varied debate on men and women and their interactions. The presence of women in the societies meant that the debates had a chance of accurately representing contemporary women's own viewpoints on their role in society, not simply those of men, making the debates a significant marker of popular thought and opinion.

The Oratorical Academy at Mitre Tavern asked, "Can friendship subsist between the two sexes, without the passion of love?" In discussing marriage, La Belle Assemblée, a women's only society, asked, "In the failure of a mutual affection in the married state, which is to be preferred, to love or be loved?" The New Westminster Forum questioned, "Which is the more disagreeable, a jealous or a scolding Wife?" The society at Coachmaker's Hall debated, "Is not the deliberate Seduction of the Fair, with an intention to desert, under all circumstances, equal to murder?" American John Neal in the mid 1820s proposed the resolve, "That the intellectual powers of the two sexes are equal."

Though the decision was negative in this case, the question indicated the seriousness with which these questions were approached. Other questions seem to reveal a genuine interest in understanding relationships: "Which is to be preferred in the choice of a wife, beauty without fortune, or fortune without beauty?" and "Is it the love of the mental or personal charms of the fair sex, that is more likely to induce men to enter into the married state?"

These questions of love and marriage, and happiness in marriage, indicate how the social climate was changing, allowing for such discussions of gender relations. The societies were, in essence, part of a complete redefinition of gender roles that was underway in the late eighteenth century and into the nineteenth.

Decline

While the debating societies of 18th-century London were prominent fixtures of the public sphere, and not initially restricted by the government, they were not without their critics. Andrew describes some of the negative reaction to the societies thus: The active presence of women in the societies inevitably raised some eyebrows among more traditional types, and the debates on religious matters could not have been met with mere acceptance by the church and the clergy. Andrew cites the example of Bishop Porteus who called the debating societies, "schools of infidelity and popery." The political bent of many of the debates was seen as increasingly threatening as the French Revolution heightened the political climate. After their peak in 1780, the London debating societies generally declined in number and frequency, rising again slightly around the late 1780s, only to fall off completely by the end of the century. The French Revolution began in 1789 and Thale notes that, Understandably fearful of the ramifications of such an example just across the English Channel, the British government began to crack down on the debating societies. Without specific legislation to block the meetings, the government often intimidated or threatened the landlords of the venues where debates were held, who in turn closed the buildings to the public. 1792 saw the formation of the

After their peak in 1780, the London debating societies generally declined in number and frequency, rising again slightly around the late 1780s, only to fall off completely by the end of the century. The French Revolution began in 1789 and Thale notes that, Understandably fearful of the ramifications of such an example just across the English Channel, the British government began to crack down on the debating societies. Without specific legislation to block the meetings, the government often intimidated or threatened the landlords of the venues where debates were held, who in turn closed the buildings to the public. 1792 saw the formation of the London Corresponding Society

The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was a federation of local reading and debating clubs that in the decade following the French Revolution agitated for the democratic reform of the British Parliament. In contrast to other reform associa ...

, a group of artisans, mechanics, and shopkeepers. The LCS met in pubs and taverns, discussed openly radical works such as Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

's '' Rights of Man'', and issued proclamations in newspapers calling for adult male suffrage and parliamentary reform. Such overt radicalism certainly attracted the attention of the government, and on 21 May 1792, King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great B ...

issued a proclamation for the prevention of "seditious meetings and writings." While the proclamation did not make explicit reference to the debating societies, the membership of the LCS and the debating societies likely overlapped, and a cautionary response on behalf of the societies was observed.

For the rest of 1792, no debating societies advertised in the London newspapers. The debating societies gradually returned until late 1795, when the Two Acts were passed by the British parliament. The Treason Act and the Seditious Meeting Act required any meeting where money was taken to be licensed by two Justices of the Peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or '' puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission (letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sam ...

. The acts restricted public meetings to fifty persons, allowed licences to be revoked at any time, and invoked much stiffer penalties for any anti-monarchist sentiment. These acts effectively eliminated public, political debate, and, while the societies did continue until the turn of the century, their content was decidedly less radical and challenging. An advertisement for the London Forum in the 7 November 1796 Morning Herald warned that "Political allusion is utterly inadmissible," a stark contrast to the debates of previous years. Historian Iain McCalman has argued that in the wake of the repression of the formal debating clubs, more informal societies continued to meet in taverns and alehouses, as they were harder to control. McCalman sees in these meetings the foundations of British ultra-radicalism, and movements such as British Jacobinism

A Jacobin (; ) was a member of the Jacobin Club, a revolutionary political movement that was the most famous political club during the French Revolution (1789–1799).

The club got its name from meeting at the Dominican rue Saint-Honoré M ...

and Chartism

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, ...

.

Debating societies were an important fixture of the London social landscape for the better part of the eighteenth century. Shaped by the initial tolerance of British politics of the time, and demonstrating a progressive, democratic, and equality-minded attitude, the debating societies are perhaps the best example of truly Enlightened ideals and the rise of the public sphere.

Survivors and outlook

Due to the aforementioned decline, few of the original London debating societies have survived to the 21st century, though there are notable exceptions. The Society of Cogers, founded 1755, still operates to this day in the City of London. During the 18th century, the aforementioned anti-sedition pressure led the Cogers to recognise the monarchy explicitly in meetings. This holds to this day, where a picture of the sovereign and a "royal reference" in each meeting's opening speech maintains this tradition. Though it was strongly affected by the closure of major newspaper offices in Fleet Street from the 1960s, fragmenting into three separately-run clubs by the late 1990s as a result, ultimately those coalesced into a single Cogers organisation. The society celebrated its 250th anniversary with a keynote debate in 2005. Cogers members who were part of the original society in the 1950s and 1960s still attended regularly well into the late 2010s, ensuring continuity of the Cogers style of debating. While much younger than the original wave of London debating societies, the Sylvan Debating Club was founded in London in 1868 and has been in continuous operation since then. Membership went into decline in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but has since rebounded, and the club celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2018. Longstanding members attended the celebration, who had indeed attended the club's 100th anniversary in 1968. Another significant (although shorter lived) debating society formed in the nineteenth century was the London Dialectical Society. Established in 1867, it encouraged debate of philosophical and social topics, with a particular emphasis upon ethics, metaphysics, and theology. In addition, many new debating societies have been formed in London in recent years, including those affiliated with universities as well as independent clubs. The internet and social media have supported this activity, providing new channels to reach potential members interested in debate. During theCOVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a contagious disease caused by a virus, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The first known case was identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. The disease quick ...

lockdown in 2020, debates in many clubs have moved to online video platforms such as Zoom. Debating activity in London has as a result been given a new lease on life, with the potential to continue long into the future – though perhaps not in such a prominent and influential way as the first wave of pub and coffee house societies.

See also

*Salon (gathering)

A salon is a gathering of people held by an inspiring host. During the gathering they amuse one another and increase their knowledge through conversation. These gatherings often consciously followed Horace's definition of the aims of poetry, "ei ...

* Academy

* English coffeehouses in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

* Public House

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the United Kingdom in late 17th century, and wa ...

* London Corresponding Society

The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was a federation of local reading and debating clubs that in the decade following the French Revolution agitated for the democratic reform of the British Parliament. In contrast to other reform associa ...

* Elocution

Elocution is the study of formal speaking in pronunciation, grammar, style, and tone as well as the idea and practice of effective speech and its forms. It stems from the idea that while communication is symbolic, sounds are final and compelli ...

* Thomas Sheridan

* John Henley

* Republic of Letters

The Republic of Letters (''Respublica literaria'') is the long-distance intellectual community in the late 17th and 18th centuries in Europe and the Americas. It fostered communication among the intellectuals of the Age of Enlightenment, or ''phil ...

* Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

* Public Sphere

The public sphere (german: Öffentlichkeit) is an area in social life where individuals can come together to freely discuss and identify societal problems, and through that discussion influence political action. A "Public" is "of or concerning the ...

References

{{reflistBibliography

*Andrew, Donna T. ''London Debating Societies, 1776–1799.'' London Record Society, 1994*Andrew, Donna T. "Popular Culture and Public Debate: London 1780," ''The Historical Journal'' 39, no. 2 (June 1996): 405–23. *Benzie, W. ''The Dublin Orator: Thomas Sheridan's Influence on Eighteenth-century Rhetoric and Belles Lettres.'' Menston: Scolar Press Limited, 1972. *Cowan, Brian William. ''The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse.'' New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005. *Goring, Paul. ''The Rhetoric of Sensibility in Eighteenth-Century Culture.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. *McCalman, Iain. "Ultra-Radicalism and Convivial Debating-Clubs in London, 1795–1838." ''The English Historical Review'' 102, no. 403 (April 1987): 309–33. *Munck, Thomas. ''The Enlightenment: A Comparative Social History 1721–1794.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. * John Neal (writer), Neal, Johnbr>''Wandering Recollections of a Somewhat Busy Life.''

Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1869. *Thale, Mary. "London Debating Societies in the 1790s." ''The Historical Journal'' 32, no. 1 (March 1989): 57–86. *Timbs, John. ''Clubs and Club Life in London.'' Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1967. First published 1866 by Chatto and Windus, Publishers, London. *Van Horn Melton, James. ''The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Further reading

* Darnton, Robert. ''The Literary Underground of the Old Regime.'' Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982. * Goodman, Dena. ''The Republic of Letters: A Cultural History of the French Enlightenment.'' Cornell: Cornell University Press, 1994. * Hone, J. Ann. ''For The Cause of Truth: Radicalism in London 1796–1821.'' Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982. * Israel, Jonathan. ''Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650–1750.'' Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. * Lilti, Antoine. "Sociability and Mondanité: Men of Letters in the Parisian Salons of the Eighteenth-Century." ''French Historical Studies'' 28, no. 3 (Summer 2005): 415–45. * McKendrick, Neil, John Brewer, and J. H. Plumb. ''The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth-century England.'' London: Europa Publications Limited, 1982. * Money, John. "Taverns, Coffee Houses and Clubs: Local Politics and Popular Articulacy in the Birmingham Area, in the Age of the American Revolution." ''The Historical Journal'' 14, no. 1 (March 1971): 15–47. * Outram, Dorinda. ''The Enlightenment.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. * Sheridan, Thomas. ''A Course of Lectures on Elocution.'' New York: Georg Olms Verlag, 1970. First published in London by W. Strahan, 1762. Debating societies