Literature of Turkey on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Turkish literature ( tr, Türk edebiyatı) comprises oral compositions and written texts in

Turkish literature ( tr, Türk edebiyatı) comprises oral compositions and written texts in

''Persian Historiography & Geography''

Pustaka Nasional Pte Ltd p 69 and used the Ottoman Turkish alphabet. The history of the broader Turkic literature spans a period of nearly 1,300 years. The oldest extant records of written Turkic are the

Nasreddin also reflects another significant change that had occurred between the days when the Turkish people were nomadic and the days when they had largely become settled in Anatolia; namely, Nasreddin is a Muslim Imam. The Turkic peoples had first become

Nasreddin also reflects another significant change that had occurred between the days when the Turkish people were nomadic and the days when they had largely become settled in Anatolia; namely, Nasreddin is a Muslim Imam. The Turkic peoples had first become

The explicitly religious folk tradition of ''tekke'' literature shared a similar basis with the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition in that the poems were generally intended to be sung, generally in religious gatherings, making them somewhat akin to Western hymns (Turkish ''ilahi''). One major difference from the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition, however, is that—from the very beginning—the poems of the ''tekke'' tradition were written down. This was because they were produced by revered religious figures in the literate environment of the ''tekke'', as opposed to the milieu of the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition, where the majority could not read or write. The major figures in the tradition of ''tekke'' literature are: Yunus Emre (1240?–1320?), who is one of the most important figures in all of Turkish literature; Süleyman Çelebi (?–1422), who wrote a highly popular long poem called ''Vesîletü'n-Necât'' (وسيلة النجاة "The Means of Salvation", but more commonly known as the ''Mevlid''), concerning the Mawlid, birth of the Islamic prophet Muhammad; Kaygusuz Abdal (1397–?), who is widely considered the founder of Alevi/Bektashi literature; and Pir Sultan Abdal (?–1560), whom many consider to be the pinnacle of that literature.

The explicitly religious folk tradition of ''tekke'' literature shared a similar basis with the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition in that the poems were generally intended to be sung, generally in religious gatherings, making them somewhat akin to Western hymns (Turkish ''ilahi''). One major difference from the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition, however, is that—from the very beginning—the poems of the ''tekke'' tradition were written down. This was because they were produced by revered religious figures in the literate environment of the ''tekke'', as opposed to the milieu of the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition, where the majority could not read or write. The major figures in the tradition of ''tekke'' literature are: Yunus Emre (1240?–1320?), who is one of the most important figures in all of Turkish literature; Süleyman Çelebi (?–1422), who wrote a highly popular long poem called ''Vesîletü'n-Necât'' (وسيلة النجاة "The Means of Salvation", but more commonly known as the ''Mevlid''), concerning the Mawlid, birth of the Islamic prophet Muhammad; Kaygusuz Abdal (1397–?), who is widely considered the founder of Alevi/Bektashi literature; and Pir Sultan Abdal (?–1560), whom many consider to be the pinnacle of that literature.

The tradition of folklore—folktales, jokes, legends, and the like—in the Turkish language is very rich. Perhaps the most popular figure in the tradition is the aforementioned

The tradition of folklore—folktales, jokes, legends, and the like—in the Turkish language is very rich. Perhaps the most popular figure in the tradition is the aforementioned  Similar to the Nasreddin jokes, and arising from a similar religious milieu, are the Bektashi jokes, in which the members of the Bektashi religious order—represented through a character simply named ''Bektaşi''—are depicted as having an unusual and unorthodox wisdom, one that often challenges the values of Islam and of society.

Another popular element of Turkish folklore is the Theatre of shadows, shadow theater centered around the two characters of Karagöz and Hacivat, who both represent stock characters: Karagöz—who hails from a small village—is something of a country bumpkin, while Hacivat is a more sophisticated city-dweller. Popular legend has it that the two characters are actually based on two real persons who worked either for Osman I—the founder of the Ottoman Dynasty—or for his successor Orhan I, in the construction of a palace or possibly a mosque at Bursa, Turkey, Bursa in the early 14th century. The two workers supposedly spent much of their time entertaining the other workers, and were so funny and popular that they interfered with work on the palace, and were subsequently Decapitation, beheaded. Supposedly, however, their bodies then picked up their severed heads and walked away.

Similar to the Nasreddin jokes, and arising from a similar religious milieu, are the Bektashi jokes, in which the members of the Bektashi religious order—represented through a character simply named ''Bektaşi''—are depicted as having an unusual and unorthodox wisdom, one that often challenges the values of Islam and of society.

Another popular element of Turkish folklore is the Theatre of shadows, shadow theater centered around the two characters of Karagöz and Hacivat, who both represent stock characters: Karagöz—who hails from a small village—is something of a country bumpkin, while Hacivat is a more sophisticated city-dweller. Popular legend has it that the two characters are actually based on two real persons who worked either for Osman I—the founder of the Ottoman Dynasty—or for his successor Orhan I, in the construction of a palace or possibly a mosque at Bursa, Turkey, Bursa in the early 14th century. The two workers supposedly spent much of their time entertaining the other workers, and were so funny and popular that they interfered with work on the palace, and were subsequently Decapitation, beheaded. Supposedly, however, their bodies then picked up their severed heads and walked away.

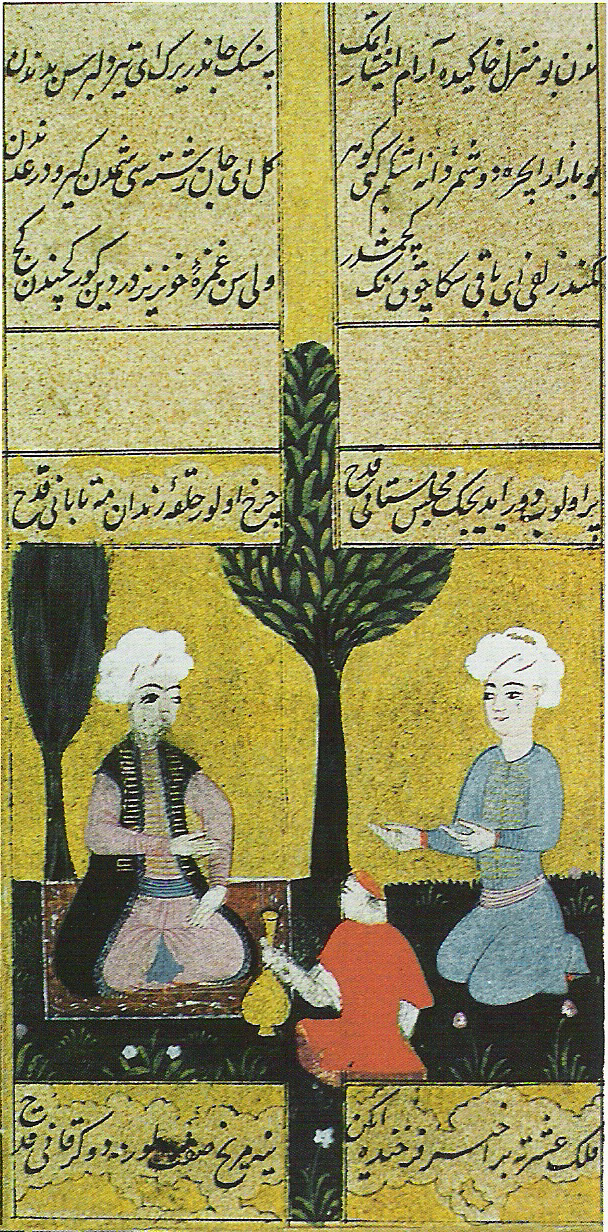

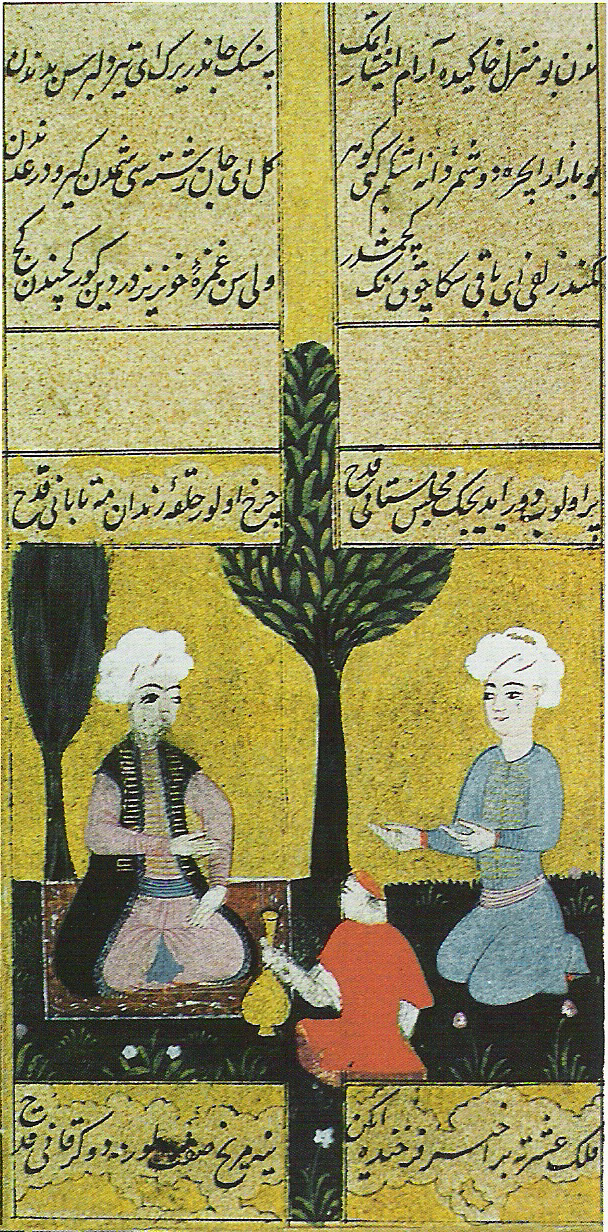

Ottoman Divan poetry was a highly ritualized and symbolic art form. From the Persian poetry that largely inspired it, it inherited a wealth of symbols whose meanings and interrelationships—both of similitude (مراعات نظير ''mura'ât-i nazîr'' / تناسب

''tenâsüb'') and opposition (تضاد ''tezâd'')—were more or less prescribed. Examples of prevalent symbols that, to some extent, oppose one another include, among others:

* the nightingale (بلبل ''bülbül'')—the rose (ﮔل ''gül'')

* the world (جهان ''cihan''; عالم ''‘âlem'')—the rosegarden (ﮔﻠﺴﺘﺎن ''gülistan''; ﮔﻠﺸﻦ ''gülşen'')

* the ascetic (زاهد ''zâhid'')—the dervish (درويش ''derviş'')

As the opposition of "the ascetic" and "the dervish" suggests, Divan poetry—much like Turkish folk poetry—was heavily influenced by Sufism#Basic beliefs, Sufi thought. One of the primary characteristics of Divan poetry, however—as of the Persian poetry before it—was its mingling of the mystical Sufi element with a profane and even erotic element. Thus, the pairing of "the nightingale" and "the rose" simultaneously suggests two different relationships:

* the relationship between the fervent lover ("the nightingale") and the inconstant beloved ("the rose")

* the relationship between the individual Sufi practitioner (who is often characterized in Sufism as a lover) and Allah, God (who is considered the ultimate source and object of love)

Similarly, "the world" refers simultaneously to the physical world and to this physical world considered as the abode of sorrow and impermanence, while "the rosegarden" refers simultaneously to a literal garden and to Heaven#In Islam, the garden of Paradise. "The nightingale", or suffering lover, is often seen as situated—both literally and figuratively—in "the world", while "the rose", or beloved, is seen as being in "the rosegarden".

Divan poetry was composed through the constant juxtaposition of many such images within a strict metrical framework, thus allowing numerous potential meanings to emerge. A brief example is the following line of verse, or ''mısra'' (مصراع), by the 18th-century Qadi, judge and poet Hayatî Efendi:

:بر گل مى وار بو گلشن ﻋالمدﻪ خارسز

:''Bir gül mü var bu gülşen-i ‘âlemde hârsız''

:("Does any rose, in this rosegarden world, lack thorns?")

Ottoman Divan poetry was a highly ritualized and symbolic art form. From the Persian poetry that largely inspired it, it inherited a wealth of symbols whose meanings and interrelationships—both of similitude (مراعات نظير ''mura'ât-i nazîr'' / تناسب

''tenâsüb'') and opposition (تضاد ''tezâd'')—were more or less prescribed. Examples of prevalent symbols that, to some extent, oppose one another include, among others:

* the nightingale (بلبل ''bülbül'')—the rose (ﮔل ''gül'')

* the world (جهان ''cihan''; عالم ''‘âlem'')—the rosegarden (ﮔﻠﺴﺘﺎن ''gülistan''; ﮔﻠﺸﻦ ''gülşen'')

* the ascetic (زاهد ''zâhid'')—the dervish (درويش ''derviş'')

As the opposition of "the ascetic" and "the dervish" suggests, Divan poetry—much like Turkish folk poetry—was heavily influenced by Sufism#Basic beliefs, Sufi thought. One of the primary characteristics of Divan poetry, however—as of the Persian poetry before it—was its mingling of the mystical Sufi element with a profane and even erotic element. Thus, the pairing of "the nightingale" and "the rose" simultaneously suggests two different relationships:

* the relationship between the fervent lover ("the nightingale") and the inconstant beloved ("the rose")

* the relationship between the individual Sufi practitioner (who is often characterized in Sufism as a lover) and Allah, God (who is considered the ultimate source and object of love)

Similarly, "the world" refers simultaneously to the physical world and to this physical world considered as the abode of sorrow and impermanence, while "the rosegarden" refers simultaneously to a literal garden and to Heaven#In Islam, the garden of Paradise. "The nightingale", or suffering lover, is often seen as situated—both literally and figuratively—in "the world", while "the rose", or beloved, is seen as being in "the rosegarden".

Divan poetry was composed through the constant juxtaposition of many such images within a strict metrical framework, thus allowing numerous potential meanings to emerge. A brief example is the following line of verse, or ''mısra'' (مصراع), by the 18th-century Qadi, judge and poet Hayatî Efendi:

:بر گل مى وار بو گلشن ﻋالمدﻪ خارسز

:''Bir gül mü var bu gülşen-i ‘âlemde hârsız''

:("Does any rose, in this rosegarden world, lack thorns?")

Here, the nightingale is only implied (as being the poet/lover), while the rose, or beloved, is shown to be capable of inflicting pain with its thorns (خار ''hâr''). The world, as a result, is seen as having both positive aspects (it is a rosegarden, and thus analogous to the garden of Paradise) and negative aspects (it is a rosegarden full of thorns, and thus different from the garden of Paradise).

As for the development of Divan poetry over the more than 500 years of its existence, that is—as the Ottomanist Walter G. Andrews points out—a study still in its infancy; clearly defined movements and periods have not yet been decided upon. Early in the history of the tradition, the Persian influence was very strong, but this was mitigated somewhat through the influence of poets such as the Azerbaijani people, Azerbaijani Nesîmî (?–1417?) and the Uyghur people, Uyghur Alisher Navoi, Ali Şîr Nevâî (1441–1501), both of whom offered strong arguments for the poetic status of the Turkic languages as against the much-venerated Persian. Partly as a result of such arguments, Divan poetry in its strongest period—from the 16th to the 18th centuries—came to display a unique balance of Persian and Turkish elements, until the Persian influence began to predominate again in the early 19th century.

Although Turkish poets (Ottoman Turks, Ottoman and Chagatai people, Chagatay) had been inspired and influenced by classical Persian poetry, it would be a superficial judgment to consider the former as blind imitators of the latter, as is often done. A limited vocabulary and common technique, and the same world of imagery and subject matter based mainly on Islamic sources, were shared by all poets of Islamic literature.

Despite the lack of certainty regarding the stylistic movements and periods of Divan poetry, however, certain highly different styles are clear enough, and can perhaps be seen as exemplified by certain poets:

Here, the nightingale is only implied (as being the poet/lover), while the rose, or beloved, is shown to be capable of inflicting pain with its thorns (خار ''hâr''). The world, as a result, is seen as having both positive aspects (it is a rosegarden, and thus analogous to the garden of Paradise) and negative aspects (it is a rosegarden full of thorns, and thus different from the garden of Paradise).

As for the development of Divan poetry over the more than 500 years of its existence, that is—as the Ottomanist Walter G. Andrews points out—a study still in its infancy; clearly defined movements and periods have not yet been decided upon. Early in the history of the tradition, the Persian influence was very strong, but this was mitigated somewhat through the influence of poets such as the Azerbaijani people, Azerbaijani Nesîmî (?–1417?) and the Uyghur people, Uyghur Alisher Navoi, Ali Şîr Nevâî (1441–1501), both of whom offered strong arguments for the poetic status of the Turkic languages as against the much-venerated Persian. Partly as a result of such arguments, Divan poetry in its strongest period—from the 16th to the 18th centuries—came to display a unique balance of Persian and Turkish elements, until the Persian influence began to predominate again in the early 19th century.

Although Turkish poets (Ottoman Turks, Ottoman and Chagatai people, Chagatay) had been inspired and influenced by classical Persian poetry, it would be a superficial judgment to consider the former as blind imitators of the latter, as is often done. A limited vocabulary and common technique, and the same world of imagery and subject matter based mainly on Islamic sources, were shared by all poets of Islamic literature.

Despite the lack of certainty regarding the stylistic movements and periods of Divan poetry, however, certain highly different styles are clear enough, and can perhaps be seen as exemplified by certain poets:

* Fuzûlî (1483?–1556); a unique poet who wrote with equal skill in Azerbaijani language, Azerbaijani,

* Fuzûlî (1483?–1556); a unique poet who wrote with equal skill in Azerbaijani language, Azerbaijani,

By the early 19th century, the Ottoman Empire had become Sick man of Europe, moribund. Attempts to right this situation had begun during the reign of Selim III, Sultan Selim III, from 1789 to 1807, but were continuously thwarted by the powerful Janissary corps. As a result, only after Mahmud II, Sultan Mahmud II had abolished the Janissary corps in 1826 was the way paved for truly effective reforms (Ottoman Turkish: تنظيمات ''tanzîmât'').

These reforms finally came to the empire during the Tanzimat period of 1839–1876, when much of the Ottoman system was reorganized along largely Civil law (legal system), French lines. The Tanzimat reforms "were designed both to modernize the empire and to forestall foreign intervention".

Along with reforms to the Ottoman system, serious reforms were also undertaken in the literature, which had become nearly as moribund as the empire itself. Broadly, these literary reforms can be grouped into two areas:

* changes brought to the language of Ottoman written literature;

* the introduction into Ottoman literature of previously unknown genres.

By the early 19th century, the Ottoman Empire had become Sick man of Europe, moribund. Attempts to right this situation had begun during the reign of Selim III, Sultan Selim III, from 1789 to 1807, but were continuously thwarted by the powerful Janissary corps. As a result, only after Mahmud II, Sultan Mahmud II had abolished the Janissary corps in 1826 was the way paved for truly effective reforms (Ottoman Turkish: تنظيمات ''tanzîmât'').

These reforms finally came to the empire during the Tanzimat period of 1839–1876, when much of the Ottoman system was reorganized along largely Civil law (legal system), French lines. The Tanzimat reforms "were designed both to modernize the empire and to forestall foreign intervention".

Along with reforms to the Ottoman system, serious reforms were also undertaken in the literature, which had become nearly as moribund as the empire itself. Broadly, these literary reforms can be grouped into two areas:

* changes brought to the language of Ottoman written literature;

* the introduction into Ottoman literature of previously unknown genres.

The reforms to the literary language were undertaken because the Ottoman Turkish language was thought by the reformists to have effectively lost its way. It had become more divorced than ever from its original basis in Turkish, with writers using more and more words and even grammatical structures derived from Persian and Arabic, rather than Turkish. Meanwhile, however, the Turkish folk literature tradition of Anatolia, away from the capital Constantinople, came to be seen as an ideal. Accordingly, many of the reformists called for written literature to turn away from the Divan tradition and towards the folk tradition; this call for change can be seen, for example, in a famous statement by the poet and reformist Ziya Pasha (1829–1880):

The reforms to the literary language were undertaken because the Ottoman Turkish language was thought by the reformists to have effectively lost its way. It had become more divorced than ever from its original basis in Turkish, with writers using more and more words and even grammatical structures derived from Persian and Arabic, rather than Turkish. Meanwhile, however, the Turkish folk literature tradition of Anatolia, away from the capital Constantinople, came to be seen as an ideal. Accordingly, many of the reformists called for written literature to turn away from the Divan tradition and towards the folk tradition; this call for change can be seen, for example, in a famous statement by the poet and reformist Ziya Pasha (1829–1880):

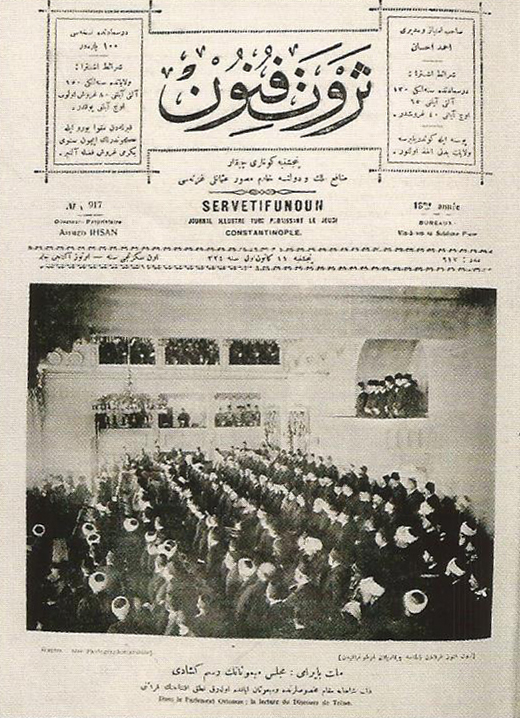

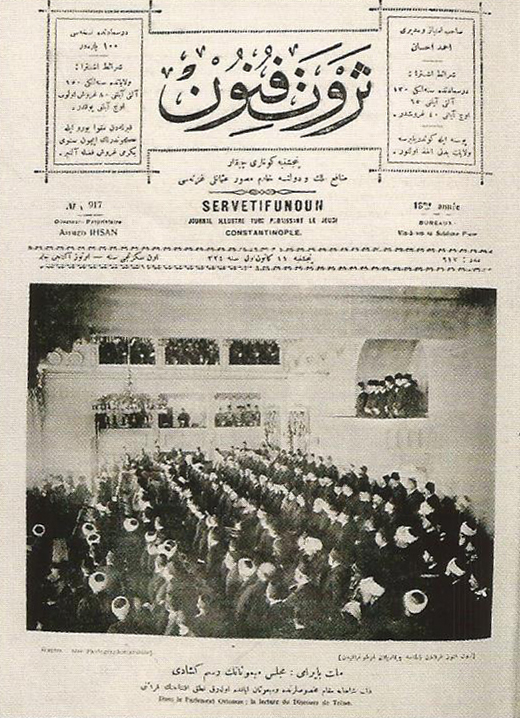

The ''Edebiyyât-ı Cedîde'', or "New Literature", movement began with the founding in 1891 of the magazine ''Servet-i Fünun, Servet-i Fünûn'' (ﺛﺮوت ﻓﻨﻮن; "Scientific Wealth"), which was largely devoted to progress—both intellectual and scientific—along the Western model. Accordingly, the magazine's literary ventures, under the direction of the poet Tevfik Fikret (1867–1915), were geared towards creating a Western-style "High culture, high art" in Turkey. The poetry of the group—of which Tevfik Fikret and Cenâb Şehâbeddîn (1870–1934) were the most influential proponents—was heavily influenced by the French Parnassian movement and the so-called "Decadence, Decadent" poets. The group's prose writers, on the other hand—particularly Halit Ziya Uşaklıgil (1867–1945)—were primarily influenced by Realism, although the writer Mehmed Rauf (1875–1931) did write the first Turkish example of a psychological novel, 1901's ''Eylül'' (ايلول; "September"). The language of the ''Edebiyyât-ı Cedîde'' movement remained strongly influenced by Ottoman Turkish.

In 1901, as a result of the article "''Edebiyyât ve Hukuk''" (ادبيات و ﺣﻘﻮق; "Literature and Law"), translated from French and published in ''Servet-i Fünûn'', the pressure of censorship was brought to bear and the magazine was closed down by the government of the Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid II, Abdülhamid II. Though it was closed for only six months, the group's writers each went their own way in the meantime, and the ''Edebiyyât-ı Cedîde'' movement came to an end.

The ''Edebiyyât-ı Cedîde'', or "New Literature", movement began with the founding in 1891 of the magazine ''Servet-i Fünun, Servet-i Fünûn'' (ﺛﺮوت ﻓﻨﻮن; "Scientific Wealth"), which was largely devoted to progress—both intellectual and scientific—along the Western model. Accordingly, the magazine's literary ventures, under the direction of the poet Tevfik Fikret (1867–1915), were geared towards creating a Western-style "High culture, high art" in Turkey. The poetry of the group—of which Tevfik Fikret and Cenâb Şehâbeddîn (1870–1934) were the most influential proponents—was heavily influenced by the French Parnassian movement and the so-called "Decadence, Decadent" poets. The group's prose writers, on the other hand—particularly Halit Ziya Uşaklıgil (1867–1945)—were primarily influenced by Realism, although the writer Mehmed Rauf (1875–1931) did write the first Turkish example of a psychological novel, 1901's ''Eylül'' (ايلول; "September"). The language of the ''Edebiyyât-ı Cedîde'' movement remained strongly influenced by Ottoman Turkish.

In 1901, as a result of the article "''Edebiyyât ve Hukuk''" (ادبيات و ﺣﻘﻮق; "Literature and Law"), translated from French and published in ''Servet-i Fünûn'', the pressure of censorship was brought to bear and the magazine was closed down by the government of the Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid II, Abdülhamid II. Though it was closed for only six months, the group's writers each went their own way in the meantime, and the ''Edebiyyât-ı Cedîde'' movement came to an end.

The tradition of literary modernism also informs the work of Turkish women in literature, female novelist Adalet Ağaoğlu (1929– ). Her trilogy of novels collectively entitled ''Dar Zamanlar'' ("''Tight Times''", 1973–1987), for instance, examines the changes that occurred in Turkish society between the 1930s and the 1980s in a formally and technically innovative style. Orhan Pamuk (1952– ), winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature, is another such innovative novelist, though his works—such as 1990's ''Beyaz Kale'' ("''The White Castle''") and ''Kara Kitap'' ("''The Black Book (Orhan Pamuk novel), The Black Book''") and 1998's ''Benim Adım Kırmızı'' ("''My Name is Red''")—are influenced more by Postmodern literature, postmodernism than by modernism. This is true also of Latife Tekin (1957– ), whose first novel ''Sevgili Arsız Ölüm'' ("''Dear Shameless Death''", 1983) shows the influence not only of postmodernism, but also of magic realism. Elif Şafak has been one of the most outstanding authors of Turkish literature which has new tendencies in language and theme in 2000s. Şafak was distinguished first by her use of extensive vocabulary and then became one of the pioneers in Turkish literature in international scope as a bilingual author who writes both in Turkish and in English.

A recent study by Can and PattonCan & Patton provides a quantitative analysis of twentieth century Turkish literature using forty novels of forty authors ranging from Mehmet Rauf's (1875–1931) ''Eylül'' (1901) to Ahmet Altan's (1950–) ''Kılıç Yarası Gibi'' (1998). They show using statistical analysis that, as time passes, words, in terms of both tokens (in text) and types (in vocabulary), have become longer. They indicate that the increase in word lengths with time can be attributed to the government-initiated language reform of the 20th century. This reform aimed at replacing foreign words used in Turkish, especially Arabic- and Persian-based words (since they were in majority when the reform was initiated in the early 1930s), with newly coined pure Turkish neologisms created by adding suffixes to Turkish word stems. Can and Patton; based on their observations of the change of a specific word use (more specifically in newer works the preference of "ama" over "fakat", both borrowed from Arabic and meaning 'but', and their inverse usage correlation is statistically significant); also speculate that the word length increase can influence the common word choice preferences of authors.

The tradition of literary modernism also informs the work of Turkish women in literature, female novelist Adalet Ağaoğlu (1929– ). Her trilogy of novels collectively entitled ''Dar Zamanlar'' ("''Tight Times''", 1973–1987), for instance, examines the changes that occurred in Turkish society between the 1930s and the 1980s in a formally and technically innovative style. Orhan Pamuk (1952– ), winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature, is another such innovative novelist, though his works—such as 1990's ''Beyaz Kale'' ("''The White Castle''") and ''Kara Kitap'' ("''The Black Book (Orhan Pamuk novel), The Black Book''") and 1998's ''Benim Adım Kırmızı'' ("''My Name is Red''")—are influenced more by Postmodern literature, postmodernism than by modernism. This is true also of Latife Tekin (1957– ), whose first novel ''Sevgili Arsız Ölüm'' ("''Dear Shameless Death''", 1983) shows the influence not only of postmodernism, but also of magic realism. Elif Şafak has been one of the most outstanding authors of Turkish literature which has new tendencies in language and theme in 2000s. Şafak was distinguished first by her use of extensive vocabulary and then became one of the pioneers in Turkish literature in international scope as a bilingual author who writes both in Turkish and in English.

A recent study by Can and PattonCan & Patton provides a quantitative analysis of twentieth century Turkish literature using forty novels of forty authors ranging from Mehmet Rauf's (1875–1931) ''Eylül'' (1901) to Ahmet Altan's (1950–) ''Kılıç Yarası Gibi'' (1998). They show using statistical analysis that, as time passes, words, in terms of both tokens (in text) and types (in vocabulary), have become longer. They indicate that the increase in word lengths with time can be attributed to the government-initiated language reform of the 20th century. This reform aimed at replacing foreign words used in Turkish, especially Arabic- and Persian-based words (since they were in majority when the reform was initiated in the early 1930s), with newly coined pure Turkish neologisms created by adding suffixes to Turkish word stems. Can and Patton; based on their observations of the change of a specific word use (more specifically in newer works the preference of "ama" over "fakat", both borrowed from Arabic and meaning 'but', and their inverse usage correlation is statistically significant); also speculate that the word length increase can influence the common word choice preferences of authors.

Another revolution in Turkish poetry came about in 1941 with the publication of a small volume of verse preceded by an essay and entitled ''Garip'' ("''Strange''"). The authors were Orhan Veli Kanık (1914–1950), Melih Cevdet Anday (1915–2002), and Oktay Rifat (1914–1988). Explicitly opposing themselves to everything that had gone in poetry before, they sought instead to create a popular art, "to explore the people's tastes, to determine them, and to make them reign supreme over art". To this end, and inspired in part by contemporary French poets like Jacques Prévert, they employed not only a variant of the free verse introduced by Nâzım Hikmet, but also highly Colloquialism, colloquial language, and wrote primarily about mundane daily subjects and the ordinary man on the street. The reaction was immediate and polarized: most of the Academia, academic establishment and older poets vilified them, while much of the Turkish population embraced them wholeheartedly. Though the movement itself lasted only ten years—until Orhan Veli's death in 1950, after which Melih Cevdet Anday and Oktay Rifat moved on to other styles—its effect on Turkish poetry continues to be felt today.

Just as the Garip movement was a reaction against earlier poetry, so—in the 1950s and afterwards—was there a reaction against the Garip movement. The poets of this movement, soon known as ''İkinci Yeni'' ("Second New",) opposed themselves to the social aspects prevalent in the poetry of Nâzım Hikmet and the Garip poets, and instead—partly inspired by the disruption of language in such Western movements as Dada and Surrealism—sought to create a more abstract poetry through the use of jarring and unexpected language, complex images, and the association of ideas. To some extent, the movement can be seen as bearing some of the characteristics of postmodern literature. The most well-known poets writing in the "Second New" vein were Turgut Uyar (1927–1985), Edip Cansever (1928–1986), Cemal Süreya (1931–1990), Ece Ayhan (1931–2002), Sezai Karakoç (1933– ), İlhan Berk (1918–2008).

Outside of the Garip and "Second New" movements also, a number of significant poets have flourished, such as Fazıl Hüsnü Dağlarca (1914–2008), who wrote poems dealing with fundamental concepts like life, death, God, time, and the cosmos; Behçet Necatigil (1916–1979), whose somewhat Allegory, allegorical poems explore the significance of Middle class, middle-class daily life; Can Yücel (1926–1999), who—in addition to his own highly colloquial and varied poetry—was also a translator into Turkish of a variety of world literature; İsmet Özel (1944– ), whose early poetry was highly leftist but whose poetry since the 1970s has shown a strong Mysticism, mystical and even Islamism, Islamist influence; and Hasan Hüseyin Korkmazgil (1927–1984) who wrote collectivist-realist poetry.

Another revolution in Turkish poetry came about in 1941 with the publication of a small volume of verse preceded by an essay and entitled ''Garip'' ("''Strange''"). The authors were Orhan Veli Kanık (1914–1950), Melih Cevdet Anday (1915–2002), and Oktay Rifat (1914–1988). Explicitly opposing themselves to everything that had gone in poetry before, they sought instead to create a popular art, "to explore the people's tastes, to determine them, and to make them reign supreme over art". To this end, and inspired in part by contemporary French poets like Jacques Prévert, they employed not only a variant of the free verse introduced by Nâzım Hikmet, but also highly Colloquialism, colloquial language, and wrote primarily about mundane daily subjects and the ordinary man on the street. The reaction was immediate and polarized: most of the Academia, academic establishment and older poets vilified them, while much of the Turkish population embraced them wholeheartedly. Though the movement itself lasted only ten years—until Orhan Veli's death in 1950, after which Melih Cevdet Anday and Oktay Rifat moved on to other styles—its effect on Turkish poetry continues to be felt today.

Just as the Garip movement was a reaction against earlier poetry, so—in the 1950s and afterwards—was there a reaction against the Garip movement. The poets of this movement, soon known as ''İkinci Yeni'' ("Second New",) opposed themselves to the social aspects prevalent in the poetry of Nâzım Hikmet and the Garip poets, and instead—partly inspired by the disruption of language in such Western movements as Dada and Surrealism—sought to create a more abstract poetry through the use of jarring and unexpected language, complex images, and the association of ideas. To some extent, the movement can be seen as bearing some of the characteristics of postmodern literature. The most well-known poets writing in the "Second New" vein were Turgut Uyar (1927–1985), Edip Cansever (1928–1986), Cemal Süreya (1931–1990), Ece Ayhan (1931–2002), Sezai Karakoç (1933– ), İlhan Berk (1918–2008).

Outside of the Garip and "Second New" movements also, a number of significant poets have flourished, such as Fazıl Hüsnü Dağlarca (1914–2008), who wrote poems dealing with fundamental concepts like life, death, God, time, and the cosmos; Behçet Necatigil (1916–1979), whose somewhat Allegory, allegorical poems explore the significance of Middle class, middle-class daily life; Can Yücel (1926–1999), who—in addition to his own highly colloquial and varied poetry—was also a translator into Turkish of a variety of world literature; İsmet Özel (1944– ), whose early poetry was highly leftist but whose poetry since the 1970s has shown a strong Mysticism, mystical and even Islamism, Islamist influence; and Hasan Hüseyin Korkmazgil (1927–1984) who wrote collectivist-realist poetry.

"Nâzım Hikmet: Life Story"

Tr. Nurgül Kıvılcım Yavuz. Retrieved 1 March 2006. * Gökalp, G. Gonca.

Osmanlı Dönemi Türk Romanının Başlangıcında Beş Eser

in ''Hacettepe Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Dergisi'', pp. 185–202. * Talât Sait Halman, Halman, Talât Sait; ed. tr

"Introduction"

''Just for the Hell of It: 111 Poems by Orhan Veli Kanık''. Multilingual Yabancı Dil Yayınları, 1997. * Hagen, Gottfried, ''Sira, Ottoman Turkish,'' in Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God (2 vols.), Edited by C. Fitzpatrick and A. Walker, Santa Barbara, ABC-CLIO, 2014, Vol. II, pp. 585–597. * Holbrook, Victoria. "Originality and Ottoman Poetics: In the Wilderness of the New". ''Journal of the American Oriental Society'', Vol. 112, No. 3. (Jul.–Sep. 1992), pp. 440–454. * Karaalioğlu, Seyit Kemal. ''Türk Edebiyatı Tarihi''. İstanbul: İnkılâp ve Aka Basımevi, 1980. * —; ed. ''Ziya Paşa: Hayatı ve Şiirleri''. İstanbul: İnkılâp ve Aka Basımevi, 1984. * Toby Lester, Lester, Toby. (1997

"New-Alphabet Disease?"

Retrieved 6 March 2006. * Lewis, Geoffrey (1999). ''The Turkish Language Reform: A Catastrophic Success.'' Oxford : Oxford University Press. * Philip Mansel, Mansel, Philip. ''Constantinople: City of the World's Desire, 1453–1924''. . * Moran, Berna. ''Türk Romanına Eleştirel Bir Bakış''. Vol. 1. . * Muhtar, İbrahim et al. (2003

"Genç Kalemler"

Retrieved 23 February 2006. * Pala, İskender. ''Divân Şiiri Antolojisi: Dîvânü'd-Devâvîn''. . * Paskin, Sylvia. (2005

Retrieved 5 March 2006. * Selçuk Üniversitesi Uzaktan Eğitim Programı (SUZEP)

Retrieved 29 May 2006. * Şafak, Elif. (2005

Retrieved 24 February 2006. * Şentürk, Ahmet Atilla. ''Osmanlı Şiiri Antolojisi''. . * Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar, Tanpınar, Ahmet Hamdi. ''19'uncu Asır Türk Edebiyatı Tarihi''. İstanbul: Çağlayan Kitabevi, 1988. * Tietze, Andreas; ed. "Önsöz", ''Akabi Hikyayesi''. pp. IX–XXI. İstanbul: Eren Yayıncılık ve Kitapçılık Ltd. Şti., 1991. * Wolf-Gazo, Ernest. (1996

"John Dewey in Turkey: An Educational Mission"

Retrieved 6 March 2006.

Ottoman Text Archive Project - University of Washington

A diverse collection of selected Ottoman texts, tools for working with digitized texts, and various projects for the dissemination of Ottoman texts.

Contemporary Turkish Literature

An excellent and well-translated selection of contemporary Turkish literature hosted by Boğaziçi University in Istanbul

Encyclopedia of Turkish Authors

A very comprehensive encyclopedia from the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism

A website with a number of Turkish literature-related links

The Online Bibliography of Ottoman-Turkish Literature

A bi-lingual site presenting in English (see in Turkish section below) a user-submissable database of references to theses, books, articles, papers and research-projects

Turkish Cultural Foundation

A website with a great deal of information on a number of Turkish authors and literary genres

A website with a good selection of both contemporary and somewhat older Turkish poems

Turkishpoetry.net

Contemporary Turkish poetry web site

ATON

the Uysal-Walker Archive of Turkish Oral Narrative A searchable archive of oral literature based at Texas Tech University containing links to numerous MP3 files.

Divan Edebiyat?

A website with many examples of Ottoman Divan poetry

Osmanlı Edebiyatı Çalışmaları Bibliyografyası Veritabanı

A bi-lingual site presenting (in Turkish, see above) a user-submissable database of references to theses, books, articles, papers and research-projects {{DEFAULTSORT:Turkish Literature Turkish literature, Turkish culture, Literature

Turkish literature ( tr, Türk edebiyatı) comprises oral compositions and written texts in

Turkish literature ( tr, Türk edebiyatı) comprises oral compositions and written texts in Turkic languages

The Turkic languages are a language family of over 35 documented languages, spoken by the Turkic peoples of Eurasia from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe to Central Asia, East Asia, North Asia ( Siberia), and Western Asia. The Turkic l ...

. The Ottoman and Azerbaijani forms of Turkish, which forms the basis of much of the written corpus, were highly influenced by Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

and Arabic literature,Bertold Spuler''Persian Historiography & Geography''

Pustaka Nasional Pte Ltd p 69 and used the Ottoman Turkish alphabet. The history of the broader Turkic literature spans a period of nearly 1,300 years. The oldest extant records of written Turkic are the

Orhon inscriptions

The Orkhon inscriptions (also known as the Orhon inscriptions, Orhun inscriptions, Khöshöö Tsaidam monuments (also spelled ''Khoshoo Tsaidam'', ''Koshu-Tsaidam'' or ''Höshöö Caidam''), or Kul Tigin steles ( zh, t=闕特勤碑, s=阙特勤� ...

, found in the Orhon River valley in central Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

and dating to the 7th century. Subsequent to this period, between the 9th and 11th centuries, there arose among the nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

ic Turkic peoples

The Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West, Central, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose members speak languages belonging t ...

of Central Asia a tradition of oral

The word oral may refer to:

Relating to the mouth

* Relating to the mouth, the first portion of the alimentary canal that primarily receives food and liquid

**Oral administration of medicines

** Oral examination (also known as an oral exam or or ...

epics

The Experimental Physics and Industrial Control System (EPICS) is a set of software tools and applications used to develop and implement distributed control systems to operate devices such as particle accelerators, telescopes and other large sci ...

, such as the '' Book of Dede Korkut'' of the Oghuz Turks— ancestors of the modern Turkish people

The Turkish people, or simply the Turks ( tr, Türkler), are the world's largest Turkic ethnic group; they speak various dialects of the Turkish language and form a majority in Turkey and Northern Cyprus. In addition, centuries-old ethnic ...

—and the Manas epic of the Kyrgyz people.

Beginning with the victory of the Seljuks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; fa, سلجوقیان ''Saljuqian'', alternatively spelled as Seljuqs or Saljuqs), also known as Seljuk Turks, Seljuk Turkomans "The defeat in August 1071 of the Byzantine emperor Romanos Diogenes

by the Turk ...

at the Battle of Manzikert in the late 11th century, the Oghuz Turks began to settle in Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

, and in addition to the earlier oral traditions there arose a written literary tradition issuing largely—in terms of themes, genres, and styles—from Arabic and Persian literature

Persian literature ( fa, ادبیات فارسی, Adabiyâte fârsi, ) comprises oral compositions and written texts in the Persian language and is one of the world's oldest literatures. It spans over two-and-a-half millennia. Its sources h ...

. For the next 900 years, until shortly before the fall of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in 1922, the oral and written traditions would remain largely separate from one another. With the founding of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, the two traditions came together for the first time.

History

The earliest known examples ofTurkic poetry

Turkic may refer to:

* anything related to the country of Turkey

* Turkic languages, a language family of at least thirty-five documented languages

** Turkic alphabets (disambiguation)

** Turkish language, the most widely spoken Turkic language

* ...

date to sometime in the 6th century AD and were composed in the Uyghur language

The Uyghur or Uighur language (; , , , or , , , , CTA: Uyğurçä; formerly known as Eastern Turki), is a Turkic language written in a Uyghur Perso-Arabic script with 8-11 million speakers, spoken primarily by the Uyghur people in the Xi ...

. Some of the earliest verses attributed to Uyghur Turkic

The Karluk or Qarluq languages are a sub-branch of the Turkic language family that developed from the varieties once spoken by Karluks.

Many Middle Turkic works were written in these languages. The language of the Kara-Khanid Khanate was known ...

writers are only available in Chinese language translations. During the era of oral poetry, the earliest Turkic verses were intended as songs and their recitation a part of the community's social life and entertainment. For example, in the shamanistic

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with what they believe to be a spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiri ...

and animistic

Animism (from Latin: ' meaning ' breath, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, ...

culture of the pre-Islamic Turkic peoples verses of poetry were performed at religious gatherings in ceremonies before a hunt (''sığır''), at communal feasts following a hunt (''şölen''). Poetry was also sung at solemn times and elegy

An elegy is a poem of serious reflection, and in English literature usually a lament for the dead. However, according to ''The Oxford Handbook of the Elegy'', "for all of its pervasiveness ... the 'elegy' remains remarkably ill defined: sometime ...

called ''sagu'' were recited at ''yuğ'' funerals and other commemorations of the dead.

Of the long epics, only the Oğuzname

Oguzname is the name of several historical books about the legends of the Turkic peoples. It is a composite word where Oğuz refers to Oghuz Khagan, the legendary king of the Turkic peoples and ''name'' means the story. According to the Islam ency ...

has survived in its entirety. The Book of Dede Korkut

The ''Book of Dede Korkut'' or ''Book of Korkut Ata'' ( az, Kitabi-Dədə Qorqud, ; tk, Kitaby Dädem Gorkut; tr, Dede Korkut Kitabı) is the most famous among the epic stories of the Oghuz Turks. The stories carry morals and values signific ...

may have had its origins in the poetry of the 10th century but remained an oral tradition until the 15th century. The earlier written works Kutadgu Bilig

The ''Kutadgu Bilig'' or ''Qutadğu Bilig'' (; Middle Turkic: ), is an 11th century work written by Yūsuf Balasaguni for the prince of Kashgar. The text reflects the author's and his society's beliefs, feelings and practices with regard to quite ...

and Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk

The ' ( ar, ديوان لغات الترك, lit=Compendium of the languages of the Turks) is the first comprehensive dictionary of Turkic languages, compiled in 1072–74 by the Turkic scholar Mahmud Kashgari who extensively studied the Turkic ...

date to the second half of the 11th century and are the earliest known examples of Turkish literature with few exceptions.

One of the most important figures of early Turkish literature was the 13th century Sufi poet Yunus Emre

Yunus Emre () also known as Derviş Yunus (Yunus the Dervish) (1238–1328) (Old Anatolian Turkish: يونس امره)

was a Turkish folk poet and Islamic Sufi mystic who greatly influenced Turkish culture. His name, ''Yunus'', is the Muslim ...

. The golden age of Ottoman literature

Turkish literature ( tr, Türk edebiyatı) comprises oral compositions and written texts in Turkic languages. The Ottoman and Azerbaijani forms of Turkish, which forms the basis of much of the written corpus, were highly influenced by Persian a ...

lasted from the 15th century until the 18th century and included mostly divan poetry

In Islamic cultures of the Middle East, North Africa, Sicily and South Asia, a Diwan ( fa, دیوان, ''divân'', ar, ديوان, ''dīwān'') is a collection of poems by one author, usually excluding his or her long poems ( mathnawī).

The ...

but also some prose works, most notably the 10-volume Seyahatnâme (Book of Travels) written by Evliya Çelebi

Derviş Mehmed Zillî (25 March 1611 – 1682), known as Evliya Çelebi ( ota, اوليا چلبى), was an Ottoman explorer who travelled through the territory of the Ottoman Empire and neighboring lands over a period of forty years, recording ...

.

Periodization

The periodization of Turkish literature is debated and scholars have floated different proposals to classify the stages of Turkic literary development. One proposal divides Turkish literature into early literature (8th to 19th c.) and modern (19th to 21st c.). Other systems of classification have divided the literature into three periods either pre-Islamic/Islamic/modern or pre-Ottoman/Ottoman/modern. Yet another more complex approach suggests a 5-stage division including both pre-Islamic (until the 11th century) and pre-Ottoman Islamic (between the 11th and 13th centuries). The 5-stage approach further divides modern literature into a transitional period from the 1850s to the 1920s and finally a modern period reaching into the present day.The two traditions of Turkish literature

Throughout most of its history, Turkish literature has been rather sharply divided into two different traditions, neither of which exercised much influence upon the other until the 19th century. The first of these two traditions is Turkish folk literature, and the second is Turkish written literature. For most of the history of Turkish literature, the salient difference between the folk and the written traditions has been the variety of language employed. The folk tradition, by and large, was an oral tradition carried on byminstrel

A minstrel was an entertainer, initially in medieval Europe. It originally described any type of entertainer such as a musician, juggler, acrobat, singer or fool; later, from the sixteenth century, it came to mean a specialist entertainer ...

s and remained free of the influence of Persian and Arabic literature, and consequently of those literatures' respective languages. In folk poetry—which is by far the tradition's dominant genre—this basic fact led to two major consequences in terms of poetic style:

* folk poetry made use of syllabic verse, as opposed to the qualitative verse employed in the written poetic tradition

* the basic structural unit of folk poetry became the quatrain (Turkish: ''dörtlük'') rather than the couplets (Turkish: ''beyit'') more commonly employed in written poetry

Furthermore, Turkish folk poetry has always had an intimate connection with song—most of the poetry was, in fact, expressly composed so as to be sung—and so became to a great extent inseparable from the tradition of Turkish folk music

Turkish folk music (''Türk Halk Müziği'') is the traditional music of Turkish people living in Turkey influenced by the cultures of Anatolia and former territories in Europe and Asia. Its unique structure includes regional differences under ...

.

In contrast to the tradition of Turkish folk literature, Turkish written literature—prior to the founding

Founding may refer to:

* The formation of a corporation, government, or other organization

* The laying of a building's Foundation

* The casting of materials in a mold

See also

* Foundation (disambiguation)

* Incorporation (disambiguation)

In ...

of the Republic of Turkey in 1923—tended to embrace the influence of Persian and Arabic literature. To some extent, this can be seen as far back as the Seljuk Seljuk or Saljuq (سلجوق) may refer to:

* Seljuk Empire (1051–1153), a medieval empire in the Middle East and central Asia

* Seljuk dynasty (c. 950–1307), the ruling dynasty of the Seljuk Empire and subsequent polities

* Seljuk (warlord) (di ...

period in the late 11th to early 14th centuries, where official business was conducted in the Persian language, rather than in Turkish, and where a court poet such as Dehhanî—who served under the 13th century sultan Ala ad-Din Kay Qubadh I—wrote in a language highly inflected with Persian.

When the Ottoman Empire arose early in the 14th century, in northwestern Anatolia, it continued this tradition. The standard poetic forms—for poetry was as much the dominant genre in the written tradition as in the folk tradition—were derived either directly from the Persian literary tradition (the ''gazel

''Gazel'' is a form of Turkish music that has almost died out. While in other parts of West Asia, ''gazel'' is synonymous with '' ghazal'', in Turkey it denotes an improvised form of solo singing that is sometimes accompanied by the '' ney'', '' ud ...

'' غزل; the '' mesnevî'' مثنوی), or indirectly through Persian from the Arabic (the '' kasîde'' قصيده). However, the decision to adopt these poetic forms wholesale led to two important further consequences:

* the poetic meters (Turkish: ''aruz'') of Persian poetry were adopted;

* Persian- and Arabic-based words were brought into the Turkish language in great numbers, as Turkish words rarely worked well within the system of Persian poetic meter.

Out of this confluence of choices, the Ottoman Turkish language—which was always highly distinct from standard Turkish—was effectively born. This style of writing under Persian and Arabic influence came to be known as "Divan literature" (Turkish: ''divan edebiyatı''), '' dîvân'' (ديوان) being the Ottoman Turkish word referring to the collected works of a poet.

Just as Turkish folk poetry was intimately bound up with Turkish folk music, so did Ottoman Divan poetry develop a strong connection with Turkish classical music

Ottoman music ( tr, Osmanlı müziği) or Turkish classical music ( tr, Türk sanat müziği) is the tradition of classical music originating in the Ottoman Empire. Developed in the palace, major Ottoman cities, and Sufi lodges, it traditionally ...

, with the poems of the Divan poets often being taken up to serve as song lyrics.

Folk literature

Turkish folk literature is anoral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985) ...

deeply rooted, in its form, in Central Asian nomadic traditions. However, in its themes, Turkish folk literature reflects the problems peculiar to a settled (or settling) people who have abandoned the nomadic lifestyle. One example of this is the series of folktales surrounding the figure of Keloğlan, a young boy beset with the difficulties of finding a wife, helping his mother to keep the family house intact, and dealing with the problems caused by his neighbors. Another example is the rather mysterious figure of Nasreddin

Nasreddin () or Nasreddin Hodja (other variants include: Mullah Nasreddin Hooja, Nasruddin Hodja, Mullah Nasruddin, Mullah Nasriddin, Khoja Nasriddin) (1208-1285) is a character in the folklore of the Muslim world from Arabia to Central Asia ...

, a trickster

In mythology and the study of folklore and religion, a trickster is a character in a story ( god, goddess, spirit, human or anthropomorphisation) who exhibits a great degree of intellect or secret knowledge and uses it to play tricks or otherwi ...

who often plays jokes, of a sort, on his neighbors.

Nasreddin also reflects another significant change that had occurred between the days when the Turkish people were nomadic and the days when they had largely become settled in Anatolia; namely, Nasreddin is a Muslim Imam. The Turkic peoples had first become

Nasreddin also reflects another significant change that had occurred between the days when the Turkish people were nomadic and the days when they had largely become settled in Anatolia; namely, Nasreddin is a Muslim Imam. The Turkic peoples had first become Islamized

Islamization, Islamicization, or Islamification ( ar, أسلمة, translit=aslamāh), refers to the process through which a society shifts towards the religion of Islam and becomes largely Muslim. Societal Islamization has historically occurre ...

sometime around the 9th or 10th century, as is evidenced from the clear Islamic influence on the 11th century Karakhanid

The Kara-Khanid Khanate (; ), also known as the Karakhanids, Qarakhanids, Ilek Khanids or the Afrasiabids (), was a Turkic khanate that ruled Central Asia in the 9th through the early 13th century. The dynastic names of Karakhanids and Ilek K ...

work the ''Kutadgu Bilig

The ''Kutadgu Bilig'' or ''Qutadğu Bilig'' (; Middle Turkic: ), is an 11th century work written by Yūsuf Balasaguni for the prince of Kashgar. The text reflects the author's and his society's beliefs, feelings and practices with regard to quite ...

'' ("''Wisdom of Royal Glory''"), written by Yusuf Has Hajib. The religion henceforth came to exercise an enormous influence on Turkish society and literature, particularly the heavily mystically oriented Sufi and Shi'a varieties of Islam. The Sufi influence, for instance, can be seen clearly not only in the tales concerning Nasreddin but also in the works of Yunus Emre

Yunus Emre () also known as Derviş Yunus (Yunus the Dervish) (1238–1328) (Old Anatolian Turkish: يونس امره)

was a Turkish folk poet and Islamic Sufi mystic who greatly influenced Turkish culture. His name, ''Yunus'', is the Muslim ...

, a towering figure in Turkish literature and a poet who lived at the end of the 13th and beginning of the 14th century, probably in the Karamanid

The Karamanids ( tr, Karamanoğulları or ), also known as the Emirate of Karaman and Beylik of Karaman ( tr, Karamanoğulları Beyliği), was one of the Anatolian beyliks, centered in South-Central Anatolia around the present-day Karaman Pr ...

state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

in south-central Anatolia. The Shi'a influence, on the other hand, can be seen extensively in the tradition of the ''aşık''s, or ''ozan''s, who are roughly akin to medieval European minstrel

A minstrel was an entertainer, initially in medieval Europe. It originally described any type of entertainer such as a musician, juggler, acrobat, singer or fool; later, from the sixteenth century, it came to mean a specialist entertainer ...

s and who traditionally have had a strong connection with the Alevi

Alevism or Anatolian Alevism (; tr, Alevilik, ''Anadolu Aleviliği'' or ''Kızılbaşlık''; ; az, Ələvilik) is a local Islamic tradition, whose adherents follow the mystical Alevi Islamic ( ''bāṭenī'') teachings of Haji Bektash Veli, w ...

faith, which can be seen as something of a homegrown Turkish variety of Shi'a Islam. It is, however, important to note that in Turkish culture, such a neat division into Sufi and Shi'a is scarcely possible: for instance, Yunus Emre is considered by some to have been an Alevi, while the entire Turkish ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition is permeated with the thought of the Bektashi

The Bektashi Order; sq, Tarikati Bektashi; tr, Bektaşi or Bektashism is an Islamic Sufi mystic movement originating in the 13th-century. It is named after the Anatolian saint Haji Bektash Wali (d. 1271). The community is currently led by ...

Sufi order, which is itself a blending of Shi'a and Sufi concepts. The word ''aşık'' (literally, "lover") is in fact the term used for first-level members of the Bektashi order.

Because the Turkish folk literature tradition extends in a more or less unbroken line from about the 10th or 11th century to today, it is perhaps best to consider the tradition from the perspective of genre. There are three basic genres in the tradition: epic; folk poetry; and folklore.

The epic tradition

The Turkish epic has its roots in the Central Asian epic tradition that gave rise to the '' Book of Dede Korkut''; written in the Azerbaijani language – and recognizably similar to modern Istanbul Turkish – the form developed from the oral traditions of the Oghuz Turks (a branch of the Turkic peoples which migrated towardswestern Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

and eastern Europe through Transoxiana, beginning in the 9th century). The ''Book of Dede Korkut'' endured in the oral tradition of the Oghuz Turks after settling in Anatolia.. Alpamysh is an earlier epic, still preserved in the literature of various Turkic peoples of Central Asia in addition to its important place in the Anatolian tradition.

The ''Book of Dede Korkut'' was the primary element of the Azerbaijani–Turkish epic tradition in the Caucasus and Anatolia for several centuries. Concurrent to the ''Book of Dede Korkut'' was the so-called ''Epic of Köroğlu'', which concerns the adventures of Rüşen Ali ("Köroğlu", or "son of the blind man") as he exacted revenge for the blinding of his father. The origins of this epic are somewhat more mysterious than those of the ''Book of Dede Korkut'': many believe it to have arisen in Anatolia sometime between the 15th and 17th centuries; more reliable testimony, though, seems to indicate that the story is nearly as old as that of the ''Book of Dede Korkut'', dating from around the dawn of the 11th century. Complicating matters somewhat is the fact that Köroğlu is also the name of a poet of the ''Ashik, aşık''/''ozan'' tradition.

The epic tradition in modern Turkish literature may be seen in the ''Epic of Shaykh Bedreddin'' (''Şeyh Bedreddin Destanı''), published in 1936 by the poet Nazım Hikmet, Nâzım Hikmet Ran (1901–1963). This long poem – which concerns an Anatolian shaykh's rebellion against the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed I — is a modern epic, yet draws upon the same independent-minded traditions of the Anatolian people as depicted in the ''Epic of Köroğlu''. Many of the works of the 20th-century novelist Yaşar Kemal (1923–2015 ), such as the 1955 novel ''Memed, My Hawk'' (''İnce Memed''), can be considered modern prose epics continuing this long tradition.

Folk poetry

The folk poetry tradition in Turkish literature, as indicated above, was strongly influenced by the Islamic Sufi and Shi'a traditions. Furthermore, as partly evidenced by the prevalence of the still existent ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition, the dominant element in Turkish folk poetry has always been song. The development of folk poetry in Turkish—which began to emerge in the 13th century with such important writers as Yunus Emre, Sultan Veled, and Şeyyâd Hamza—was given a great boost when, on 13 May 1277, Karamanoğlu Mehmet Bey declared Turkish the official state language of Anatolia's powerful Karamanid state; subsequently, many of the tradition's greatest poets would continue to emerge from this region. There are, broadly speaking, two traditions (or schools) of Turkish folk poetry: * the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition, which—although much influenced by religion, as mentioned above—was for the most part a secular tradition; * the explicitly religious tradition, which emerged from the gathering places (''Tekkes, tekke''s) of the Sufi religious orders and Shi'a groups. Much of the poetry and song of the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition, being almost exclusively oral until the 19th century, remains anonymous. There are, however, a few well-known ''aşık''s from before that time whose names have survived together with their works: the aforementioned Köroğlu (16th century); Karacaoğlan (1606?–1689?), who may be the best-known of the pre-19th century ''aşık''s; Dadaloğlu (1785?–1868?), who was one of the last of the great ''aşık''s before the tradition began to dwindle somewhat in the late 19th century; and several others. The ''aşık''s were essentially minstrels who travelled through Anatolia performing their songs on the ''Baglama, bağlama'', a mandolin-like instrument whose paired strings are considered to have a symbolic religious significance in Alevi/Bektashi culture. Despite the decline of the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition in the 19th century, it experienced a significant revival in the 20th century thanks to such outstanding figures as Aşık Veysel Şatıroğlu (1894–1973), Aşık Mahzuni Şerif (1938–2002), Neşet Ertaş (1938–2012), and many others. The explicitly religious folk tradition of ''tekke'' literature shared a similar basis with the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition in that the poems were generally intended to be sung, generally in religious gatherings, making them somewhat akin to Western hymns (Turkish ''ilahi''). One major difference from the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition, however, is that—from the very beginning—the poems of the ''tekke'' tradition were written down. This was because they were produced by revered religious figures in the literate environment of the ''tekke'', as opposed to the milieu of the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition, where the majority could not read or write. The major figures in the tradition of ''tekke'' literature are: Yunus Emre (1240?–1320?), who is one of the most important figures in all of Turkish literature; Süleyman Çelebi (?–1422), who wrote a highly popular long poem called ''Vesîletü'n-Necât'' (وسيلة النجاة "The Means of Salvation", but more commonly known as the ''Mevlid''), concerning the Mawlid, birth of the Islamic prophet Muhammad; Kaygusuz Abdal (1397–?), who is widely considered the founder of Alevi/Bektashi literature; and Pir Sultan Abdal (?–1560), whom many consider to be the pinnacle of that literature.

The explicitly religious folk tradition of ''tekke'' literature shared a similar basis with the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition in that the poems were generally intended to be sung, generally in religious gatherings, making them somewhat akin to Western hymns (Turkish ''ilahi''). One major difference from the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition, however, is that—from the very beginning—the poems of the ''tekke'' tradition were written down. This was because they were produced by revered religious figures in the literate environment of the ''tekke'', as opposed to the milieu of the ''aşık''/''ozan'' tradition, where the majority could not read or write. The major figures in the tradition of ''tekke'' literature are: Yunus Emre (1240?–1320?), who is one of the most important figures in all of Turkish literature; Süleyman Çelebi (?–1422), who wrote a highly popular long poem called ''Vesîletü'n-Necât'' (وسيلة النجاة "The Means of Salvation", but more commonly known as the ''Mevlid''), concerning the Mawlid, birth of the Islamic prophet Muhammad; Kaygusuz Abdal (1397–?), who is widely considered the founder of Alevi/Bektashi literature; and Pir Sultan Abdal (?–1560), whom many consider to be the pinnacle of that literature.

Folklore

The tradition of folklore—folktales, jokes, legends, and the like—in the Turkish language is very rich. Perhaps the most popular figure in the tradition is the aforementioned

The tradition of folklore—folktales, jokes, legends, and the like—in the Turkish language is very rich. Perhaps the most popular figure in the tradition is the aforementioned Nasreddin

Nasreddin () or Nasreddin Hodja (other variants include: Mullah Nasreddin Hooja, Nasruddin Hodja, Mullah Nasruddin, Mullah Nasriddin, Khoja Nasriddin) (1208-1285) is a character in the folklore of the Muslim world from Arabia to Central Asia ...

(known as ''Nasreddin Hoca'', or "teacher Nasreddin", in Turkish), who is the central character of thousands of stories of comical quality. He generally appears as a person who, though seeming somewhat stupid to those who must deal with him, actually proves to have a special wisdom all his own:

''One day, Nasreddin's neighbor asked him, "Khawaja, Hoca, do you have any forty-year-old vinegar?"—"Yes, I do," answered Nasreddin.—"Can I have some?" asked the neighbor. "I need some to make an ointment with."—"No, you can't have any," answered Nasreddin. "If I gave my forty-year-old vinegar to whoever wanted some, I wouldn't have had it for forty years, would I?"''

Similar to the Nasreddin jokes, and arising from a similar religious milieu, are the Bektashi jokes, in which the members of the Bektashi religious order—represented through a character simply named ''Bektaşi''—are depicted as having an unusual and unorthodox wisdom, one that often challenges the values of Islam and of society.

Another popular element of Turkish folklore is the Theatre of shadows, shadow theater centered around the two characters of Karagöz and Hacivat, who both represent stock characters: Karagöz—who hails from a small village—is something of a country bumpkin, while Hacivat is a more sophisticated city-dweller. Popular legend has it that the two characters are actually based on two real persons who worked either for Osman I—the founder of the Ottoman Dynasty—or for his successor Orhan I, in the construction of a palace or possibly a mosque at Bursa, Turkey, Bursa in the early 14th century. The two workers supposedly spent much of their time entertaining the other workers, and were so funny and popular that they interfered with work on the palace, and were subsequently Decapitation, beheaded. Supposedly, however, their bodies then picked up their severed heads and walked away.

Similar to the Nasreddin jokes, and arising from a similar religious milieu, are the Bektashi jokes, in which the members of the Bektashi religious order—represented through a character simply named ''Bektaşi''—are depicted as having an unusual and unorthodox wisdom, one that often challenges the values of Islam and of society.

Another popular element of Turkish folklore is the Theatre of shadows, shadow theater centered around the two characters of Karagöz and Hacivat, who both represent stock characters: Karagöz—who hails from a small village—is something of a country bumpkin, while Hacivat is a more sophisticated city-dweller. Popular legend has it that the two characters are actually based on two real persons who worked either for Osman I—the founder of the Ottoman Dynasty—or for his successor Orhan I, in the construction of a palace or possibly a mosque at Bursa, Turkey, Bursa in the early 14th century. The two workers supposedly spent much of their time entertaining the other workers, and were so funny and popular that they interfered with work on the palace, and were subsequently Decapitation, beheaded. Supposedly, however, their bodies then picked up their severed heads and walked away.

Ottoman literature

The two primary streams of Ottoman written literature are poetry and prose. Of the two, poetry—specifically, Divan poetry—was by far the dominant stream. Moreover, until the 19th century, Ottoman prose did not contain any examples of fiction; that is, there were no counterparts to, for instance, the European Romance (heroic literature), romance, short story, or novel (though analogous genres did, to some extent, exist in both the Turkish folk tradition and in Divan poetry).Divan poetry

Ottoman Divan poetry was a highly ritualized and symbolic art form. From the Persian poetry that largely inspired it, it inherited a wealth of symbols whose meanings and interrelationships—both of similitude (مراعات نظير ''mura'ât-i nazîr'' / تناسب

''tenâsüb'') and opposition (تضاد ''tezâd'')—were more or less prescribed. Examples of prevalent symbols that, to some extent, oppose one another include, among others:

* the nightingale (بلبل ''bülbül'')—the rose (ﮔل ''gül'')

* the world (جهان ''cihan''; عالم ''‘âlem'')—the rosegarden (ﮔﻠﺴﺘﺎن ''gülistan''; ﮔﻠﺸﻦ ''gülşen'')

* the ascetic (زاهد ''zâhid'')—the dervish (درويش ''derviş'')

As the opposition of "the ascetic" and "the dervish" suggests, Divan poetry—much like Turkish folk poetry—was heavily influenced by Sufism#Basic beliefs, Sufi thought. One of the primary characteristics of Divan poetry, however—as of the Persian poetry before it—was its mingling of the mystical Sufi element with a profane and even erotic element. Thus, the pairing of "the nightingale" and "the rose" simultaneously suggests two different relationships:

* the relationship between the fervent lover ("the nightingale") and the inconstant beloved ("the rose")

* the relationship between the individual Sufi practitioner (who is often characterized in Sufism as a lover) and Allah, God (who is considered the ultimate source and object of love)

Similarly, "the world" refers simultaneously to the physical world and to this physical world considered as the abode of sorrow and impermanence, while "the rosegarden" refers simultaneously to a literal garden and to Heaven#In Islam, the garden of Paradise. "The nightingale", or suffering lover, is often seen as situated—both literally and figuratively—in "the world", while "the rose", or beloved, is seen as being in "the rosegarden".

Divan poetry was composed through the constant juxtaposition of many such images within a strict metrical framework, thus allowing numerous potential meanings to emerge. A brief example is the following line of verse, or ''mısra'' (مصراع), by the 18th-century Qadi, judge and poet Hayatî Efendi:

:بر گل مى وار بو گلشن ﻋالمدﻪ خارسز

:''Bir gül mü var bu gülşen-i ‘âlemde hârsız''

:("Does any rose, in this rosegarden world, lack thorns?")

Ottoman Divan poetry was a highly ritualized and symbolic art form. From the Persian poetry that largely inspired it, it inherited a wealth of symbols whose meanings and interrelationships—both of similitude (مراعات نظير ''mura'ât-i nazîr'' / تناسب

''tenâsüb'') and opposition (تضاد ''tezâd'')—were more or less prescribed. Examples of prevalent symbols that, to some extent, oppose one another include, among others:

* the nightingale (بلبل ''bülbül'')—the rose (ﮔل ''gül'')

* the world (جهان ''cihan''; عالم ''‘âlem'')—the rosegarden (ﮔﻠﺴﺘﺎن ''gülistan''; ﮔﻠﺸﻦ ''gülşen'')

* the ascetic (زاهد ''zâhid'')—the dervish (درويش ''derviş'')

As the opposition of "the ascetic" and "the dervish" suggests, Divan poetry—much like Turkish folk poetry—was heavily influenced by Sufism#Basic beliefs, Sufi thought. One of the primary characteristics of Divan poetry, however—as of the Persian poetry before it—was its mingling of the mystical Sufi element with a profane and even erotic element. Thus, the pairing of "the nightingale" and "the rose" simultaneously suggests two different relationships:

* the relationship between the fervent lover ("the nightingale") and the inconstant beloved ("the rose")

* the relationship between the individual Sufi practitioner (who is often characterized in Sufism as a lover) and Allah, God (who is considered the ultimate source and object of love)

Similarly, "the world" refers simultaneously to the physical world and to this physical world considered as the abode of sorrow and impermanence, while "the rosegarden" refers simultaneously to a literal garden and to Heaven#In Islam, the garden of Paradise. "The nightingale", or suffering lover, is often seen as situated—both literally and figuratively—in "the world", while "the rose", or beloved, is seen as being in "the rosegarden".

Divan poetry was composed through the constant juxtaposition of many such images within a strict metrical framework, thus allowing numerous potential meanings to emerge. A brief example is the following line of verse, or ''mısra'' (مصراع), by the 18th-century Qadi, judge and poet Hayatî Efendi:

:بر گل مى وار بو گلشن ﻋالمدﻪ خارسز

:''Bir gül mü var bu gülşen-i ‘âlemde hârsız''

:("Does any rose, in this rosegarden world, lack thorns?")

* Fuzûlî (1483?–1556); a unique poet who wrote with equal skill in Azerbaijani language, Azerbaijani,

* Fuzûlî (1483?–1556); a unique poet who wrote with equal skill in Azerbaijani language, Azerbaijani, Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

, and Arabic, and who came to be as influential in Persian as in Divan poetry

* Hayâlî (1500?–1557); a poet that lived in the Divan tradition

* Bâkî (1526–1600); a poet of great rhetorical power and linguistic subtlety whose skill in using the pre-established Trope (linguistics), tropes of the Divan tradition is quite representative of the poetry in the time of Suleiman the Magnificent, Süleyman the Magnificent

* Nef‘î (1570?–1635); a poet considered the master of the ''kasîde'' (a kind of panegyric), as well as being known for his harshly satirical poems, which led to his execution

* Nâbî (1642–1712); a poet who wrote a number of socially oriented poems critical of the Stagnation of the Ottoman Empire, stagnation period of Ottoman history

* Nedîm (1681?–1730); a revolutionary poet of the Tulip Era in the Ottoman Empire, Tulip Era of Ottoman history, who infused the rather élite and abstruse language of Divan poetry with numerous simpler, populist elements

* Şeyh Gâlib (1757–1799); a poet of the Mevlevi, Mevlevî Tariqah, Sufi order whose work is considered the culmination of the highly complex so-called "Indian style" (سبك هندى ''sebk-i hindî'')

The vast majority of Divan poetry was Lyric poetry, lyric in nature: either ''gazel''s (which make up the greatest part of the repertoire of the tradition), or ''kasîde''s. There were, however, other common genres, most particularly the ''mesnevî'', a kind of Courtly romance, verse romance and thus a variety of narrative poetry; the two most notable examples of this form are the ''Leyli and Majnun, Leylî vü Mecnun'' (ليلى و مجنون) of Fuzûlî and the ''Hüsn ü Aşk'' (حسن و عشق; "Beauty and Love") of Şeyh Gâlib.

Early Ottoman prose

Until the 19th century, Ottoman prose never managed to develop to the extent that contemporary Divan poetry did. A large part of the reason for this was that much prose was expected to adhere to the rules of ''sec (سجع, also transliterated as ''seci''), or rhymed prose, a type of writing descended from the Arabic ''saj''' and which prescribed that between each adjective and noun in a sentence, there must be a rhyme. Nevertheless, there was a tradition of prose in the literature of the time. This tradition was exclusively Non-fiction, nonfictional in nature—the fiction tradition was limited to narrative poetry. A number of such nonfictional prose genres developed: * the ''târih'' (تاريخ), or history, a tradition in which there are many notable writers, including the 15th-century historian Aşıkpaşazâde and the 17th-century historians Kâtib Çelebi and Naîmâ * the ''seyahatname, seyâhatnâme'' (سياحت نامه), or Travel literature, travelogue, of which the outstanding example is the 17th-century ''Seyahatname, Seyahâtnâme'' ofEvliya Çelebi

Derviş Mehmed Zillî (25 March 1611 – 1682), known as Evliya Çelebi ( ota, اوليا چلبى), was an Ottoman explorer who travelled through the territory of the Ottoman Empire and neighboring lands over a period of forty years, recording ...

* the ''sefâretnâme'' (سفارت نامه), a related genre specific to the journeys and experiences of an Ottoman ambassador, and which is best exemplified by the 1718–1720 ''Paris Sefâretnâme'' of Yirmisekiz Mehmed Çelebi, ambassador to the court of Louis XV of France

* the ''siyâsetnâme'' (سياست نامه), a kind of political treatise describing the functionings of state and offering advice for rulers, an early Seljuk example of which is the 11th-century ''Siyasatnama, Siyāsatnāma'', written in Persian by Nizam al-Mulk, vizier to the Seljuk rulers Alp Arslan and Malik Shah I

* the ''tezkîre'' (تذکره), a collection of short biographies of notable figures, some of the most notable of which were the 16th-century ''tezkiretü'ş-şuarâ''s (تذكرة الشعرا), or biographies of poets, by Latîfî and Aşık Çelebi

* the ''münşeât'' (منشآت), a collection of writings and letters similar to the Western tradition of ''belles-lettres''

* the ''münâzara'' (مناظره), a collection of debates of either a religious or a philosophical nature

The 19th century and Western influence

By the early 19th century, the Ottoman Empire had become Sick man of Europe, moribund. Attempts to right this situation had begun during the reign of Selim III, Sultan Selim III, from 1789 to 1807, but were continuously thwarted by the powerful Janissary corps. As a result, only after Mahmud II, Sultan Mahmud II had abolished the Janissary corps in 1826 was the way paved for truly effective reforms (Ottoman Turkish: تنظيمات ''tanzîmât'').

These reforms finally came to the empire during the Tanzimat period of 1839–1876, when much of the Ottoman system was reorganized along largely Civil law (legal system), French lines. The Tanzimat reforms "were designed both to modernize the empire and to forestall foreign intervention".