This is a list of

internment and concentration camps, organized by country. In general, a camp or group of camps is designated to the country whose government was responsible for the establishment and/or operation of the camp regardless of the camp's location, but this principle can be, or it can appear to be, departed from in such cases as where a country's borders or name has changed or it was occupied by a foreign power.

Certain types of camps are excluded from this list, particularly refugee camps operated or endorsed by the

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is a United Nations agency mandated to aid and protect refugees, forcibly displaced communities, and stateless people, and to assist in their voluntary repatriation, local integrati ...

. Additionally,

prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military prisons. ...

s that do not also intern non-combatants or civilians are treated under a separate category.

Argentina

During the

Dirty War

The Dirty War ( es, Guerra sucia) is the name used by the military junta or civic-military dictatorship of Argentina ( es, dictadura cívico-militar de Argentina, links=no) for the period of state terrorism in Argentina from 1974 to 1983 a ...

which accompanied the

1976–1983 military dictatorship, there were over 300 places throughout the country that served as secret detention centres, where people were interrogated, tortured, and killed. Prisoners were often forced to hand and sign over property, in acts of individual, rather than official and systematic, corruption. Small children who were taken with their relatives, and babies born to female prisoners later killed, were frequently given for adoption to politically acceptable, often military, families. This is documented by a number of cases dating since the 1990s in which adopted children have identified their real families.

These were relatively small secret detention centres rather than actual camps. The peak years were 1976–78. According to the report of

CONADEP

National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (Spanish: ', CONADEP) was an Argentine organization created by President Raúl Alfonsín on 15 December 1983, shortly after his inauguration, to investigate the fate of the ''desaparecidos'' (v ...

(Argentine National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons) Report.

8,960 were killed during the Dirty War. It states that "We have reason to believe that the true figure is much higher" which is due to the fact that by the time they published the report (in late 1984) the research wasn't fully accomplished;

human rights organizations today consider 30,000 to be killed (

disappeared

An enforced disappearance (or forced disappearance) is the secret abduction or imprisonment of a person by a state or political organization, or by a third party with the authorization, support, or acquiescence of a state or political organi ...

). There was a total of 340 secret detention centres all over the country's territory.

Australia

World War I (Australia)

During World War I, 2,940 German and Austrian men were interned in ten different camps in Australia. Almost all of the men listed as being Austrians were from the

Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = " Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capi ...

n coastal region of

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

, then under Austrian rule.

In 1915 many of the smaller camps in Australia closed, with their inmates transferred to larger camps. The largest camp was

Holsworthy Internment Camp Holsworthy Internment Camp was the largest camp for prisoners of war in Australia during World War I. It was located at Holsworthy, near Liverpool on the outskirts of Sydney. There are varying estimates of the number of internees between 4,000 and 7 ...

at

Holsworthy. Families of the interned men were placed in a camp near

Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

.

World War II (Australia)

During World War II, internment camps were established at

Orange and

Hay in

New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

for ethnic Germans in Australia whose loyalty was suspect; German refugees from

Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

including the

"''Dunera'' boys"; and Italian immigrants, many were later transferred to

Tatura in

Victoria (4,721 Italian immigrants were interned in Australia).

The

Department of Immigration and Border Protection currently jointly manages two immigration centres on

Nauru

Nauru ( or ; na, Naoero), officially the Republic of Nauru ( na, Repubrikin Naoero) and formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country and microstate in Oceania, in the Central Pacific. Its nearest neighbour is Banaba Island in ...

and

Manus Islands with the host governments of

Nauru

Nauru ( or ; na, Naoero), officially the Republic of Nauru ( na, Repubrikin Naoero) and formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country and microstate in Oceania, in the Central Pacific. Its nearest neighbour is Banaba Island in ...

and

Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

, for the indefinite detention of asylum seekers attempting to reach Australia by boat. The claims of the asylum seekers to refugee status are processed in these centres. They are a part of the Australian government's policy that asylum seekers attempting to reach Australia by boat will never be permitted to settle in Australia, even if they are found to be refugees, but may be settled in other countries. The clear intention of the Australian government's policy is to deter asylum seekers attempting to reach Australia by boat. The great majority of boats come from Indonesia, which is used as a convenient jumping-off point for asylum seekers from other countries who want to reach Australia.

These centres are not

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is a United Nations agency mandated to aid and protect refugees, forcibly displaced communities, and stateless people, and to assist in their voluntary repatriation, local integrati ...

-endorsed refugee camps, and the operation of these facilities has caused

controversy

Controversy is a state of prolonged public dispute or debate, usually concerning a matter of conflicting opinion or point of view. The word was coined from the Latin ''controversia'', as a composite of ''controversus'' – "turned in an opposite d ...

, such as allegations of

torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts ...

and other breaches of

human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

.

Austria-Hungary

World War I (Austria-Hungary)

Starting in 1914, 16 camps were built in the Austrian regions of Lower Austria, Upper Austria, Salzburg and Styria. The majority of prisoners came from Russia, Italy, Serbia and Romania. Citizens deemed enemies of the state were displaced from their homes and sent to camps throughout the

Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

.

In addition of (internment camp) for civilians of enemy states, Austria-Hungary incarcerated over one million Allied prisoners of war.

Austria

* Braunau in

Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

(today:

Broumov

Broumov (; german: Braunau) is a town in Náchod District in the Hradec Králové Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 7,100 inhabitants. The town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monument zone.

Administrative ...

in the Czech Republic),

*

Drosendorf internment camp

* Grossau internment camp

*

Heinrichsgrien (today:

Jindřichovice Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

)

* Illmau internment camp - in the

Waldviertel

The (Forest Quarter; Central Bavarian: ) is the northwestern region of the northeast Austrian state of Lower Austria. It is bounded to the south by the Danube, to the southwest by Upper Austria, to the northwest and the north by the Czech Rep ...

* Katzenau - The largest internment camp in the territory of the monarchy, located on the right bank of the Danube near

Linz

Linz ( , ; cs, Linec) is the capital of Upper Austria and third-largest city in Austria. In the north of the country, it is on the Danube south of the Czech border. In 2018, the population was 204,846.

In 2009, it was a European Capital ...

, was used as an internment camp for civilians after Italy entered the war.

*

Karlstein an der Thaya

Karlstein an der Thaya is a municipality and market town in the district of Waidhofen an der Thaya in the Austrian state of Lower Austria

Lower Austria (german: Niederösterreich; Austro-Bavarian: ''Niedaöstareich'', ''Niedaestareich'') is one o ...

internment camp

* Kirchberg an der Wild internment camp - in the

Zwettl district

* Markl internment camp - In

Windigsteig in the

Waldviertel

The (Forest Quarter; Central Bavarian: ) is the northwestern region of the northeast Austrian state of Lower Austria. It is bounded to the south by the Danube, to the southwest by Upper Austria, to the northwest and the north by the Czech Rep ...

region

*

Neulengbach

Neulengbach is a municipality in the district of Sankt Pölten-Land in Lower Austria.

Population

Historical personalities

In 1911, the twenty-one year-old artist Egon Schiele met the seventeen-year-old Walburga (Wally) Neuzil, who lived wit ...

internment camp

* Sittmannshof internment camp - located near Loibes in Lower Austria's

Waldviertel

The (Forest Quarter; Central Bavarian: ) is the northwestern region of the northeast Austrian state of Lower Austria. It is bounded to the south by the Danube, to the southwest by Upper Austria, to the northwest and the north by the Czech Rep ...

region between 1915 and 1916.

* Steinklamm internment camp - located in the municipality of

Rabenstein an der Pielach in

Lower Austria

Lower Austria (german: Niederösterreich; Austro-Bavarian: ''Niedaöstareich'', ''Niedaestareich'') is one of the nine states of Austria, located in the northeastern corner of the country. Since 1986, the capital of Lower Austria has been Sankt P ...

.

* Thalerhof internment camp - Between 1914 and 1917, around 30,000 people from Eastern Europe (mainly Ukrainians) were interned in the Thalerhof camp near

Feldkirchen, south of

Graz

Graz (; sl, Gradec) is the capital city of the Austrian state of Styria and second-largest city in Austria after Vienna. As of 1 January 2021, it had a population of 331,562 (294,236 of whom had principal-residence status). In 2018, the popula ...

.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

*

Doboj

Doboj ( sr-cyrl, Добој, ) is a city located in Republika Srpska, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is situated on the banks of Bosna river, in the northern region of the Republika Srpska. As of 2013, it has a population of 71,441 ...

Hungary

*

Arad (today in

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

)

*

Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population o ...

*

Cegléd

*

Csót

*

Esztergom

Esztergom ( ; german: Gran; la, Solva or ; sk, Ostrihom, known by alternative names) is a city with county rights in northern Hungary, northwest of the capital Budapest. It lies in Komárom-Esztergom County, on the right bank of the river ...

*

Győr

Győr ( , ; german: Raab, links=no; names in other languages) is the main city of northwest Hungary, the capital of Győr-Moson-Sopron County and Western Transdanubia region, and – halfway between Budapest and Vienna – situated on one of ...

*

Keczkemét

*

Kenyérmező

* Nagymegyer (today

Veľký Meder

Veľký Meder (1948–1990 ''Čalovo'', hu, Nagymegyer, yi, Magendorf) is a town in the Dunajská Streda District, Trnava Region in southwestern Slovakia.

Etymology

The name is derived from the name of the ancient Hungarian ''Megyer'' tribe.

...

Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

)

*

Nezsider - The Nezsider concentration camp in Hungary, about 17,000 internees, mostly from Serbia and Montenegro, were held throughout the war.

*

Tápiósüly (today part of Sülysáp) - internment camp for civilians, including women and children, 45 km East of

Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population o ...

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnian war

In a UN report, 381 out of 677 alleged camps have been corroborated and verified, involving all warring factions during the

Bosnian War

The Bosnian War ( sh, Rat u Bosni i Hercegovini / Рат у Босни и Херцеговини) was an international armed conflict that took place in Bosnia and Herzegovina between 1992 and 1995. The war is commonly seen as having started ...

.

Bulgaria

World War I (Bulgaria)

During World War I,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

was part of the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

with Germany, Austria Hungary and Turkey. The Bulgarians established their largest prison camps in Sofia as well as smaller working camps across the kingdom but also military prison camps in

Bulgarian occupied Serbia.

*

Dobritch (Bazargic)

* Gorno Panicherevo - Located near

Stara Zagora

Stara Zagora ( bg, Стара Загора, ) is the sixth-largest city in Bulgaria, and the administrative capital of the homonymous Stara Zagora Province.

Name

The name comes from the Slavic root ''star'' ("old") and the name of the medieva ...

, holding prisoners of war and Serbian civilian internees, including women, children, a French school teacher and 84 Orthodox priests (according to Red Cross inspection of 11 May 1917)

*

Haskovo - This prison camp held both Serbian prisoners of war and civilian internees,

including women, children, and priests.

* Orhanie (today called

Botevgrad)

held both prisoners of war and civilian internees, mostly Serbian but also Russian.

*

Philippopolis - The camp was established on the site of a former cholera hospital and incarcerated approximately 5,250 Serbian, British, and French with a majority of Serbian civilians.

*

Rakhovo (today

Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

)

*

Sliven

Sliven ( bg, Сливен ) is the eighth-largest city in Bulgaria and the administrative and industrial centre of Sliven Province and municipality in Northern Thrace.

Sliven is famous for its heroic Haiduts who fought against the Ottoman Turk ...

- Sliven held approximately 19,900 Serbian, Romanian, Russian, British, and French prisoners, including sixteen Serbian Orthodox priests.

*

Sofia

Sofia ( ; bg, София, Sofiya, ) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain in the western parts of the country. The city is built west of the Iskar river, and h ...

- The Bulgarian army maintained three prison camps around the city, holding a total of 20,000 prisoners of war and civilian internees.

** Camp 1 - Mostly French prisoners

** Camp 2 - Mostly Serbian prisoners

** Camp 3 - Mostly Serbian prisoners with some Russians, Romanians and Italians

Bulgarian occupied Serbia

*

Niš

Niš (; sr-Cyrl, Ниш, ; names in other languages) is the third largest city in Serbia and the administrative center of the Nišava District. It is located in southern part of Serbia. , the city proper has a population of 183,164, whi ...

*

Struga

Struga ( mk, Струга , sq, Strugë) is a town and popular tourist destination situated in the south-western region of North Macedonia, lying on the shore of Lake Ohrid. The town of Struga is the seat of Struga Municipality.

Name

The n ...

(today

North Macedonia

North Macedonia, ; sq, Maqedonia e Veriut, (Macedonia before February 2019), officially the Republic of North Macedonia,, is a country in Southeast Europe. It gained independence in 1991 as one of the successor states of Socialist Feder ...

) - In Bulgarian-occupied province of Monastir in southwestern Serbia.

Cambodia

The

totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979 ...

régime established over 150 prisons for political opponents, of which

Tuol Sleng is the best known. According to

Ben Kiernan

Benedict F. "Ben" Kiernan (born 1953) is an Australian-born American academic and historian who is the Whitney Griswold Professor Emeritus of History, Professor of International and Area Studies and Director of the Genocide Studies Program at Yal ...

, "all but seven of the twenty thousand Tuol Sleng prisoners" were executed.

Canada

World War I (Canada)

Ukrainian Canadian internment

In World War I, 8,579 male "aliens of enemy nationality" were interned, including 5,954

Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1 ...

s, including ethnic

Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian. The majority of Ukrainians are Eastern Ort ...

,

Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic ...

, and

Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of ...

. Many of these internees were used for

forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

in internment camps.

Camps and relocation centres elsewhere in Canada

There were internment camps near

Kananaskis, Alberta;

Petawawa, Ontario;

Hull, Quebec

Hull is the central business district and oldest neighbourhood of the city of Gatineau, Quebec, Canada. It is located on the west bank of the Gatineau River and the north shore of the Ottawa River, directly opposite Ottawa. As part of the Canad ...

;

Minto, New Brunswick

Minto (2016 pop. 2,305) is a Canadian village straddling the border of Sunbury County and Queens County, New Brunswick. It is located on the north shore of Grand Lake, approximately 50 kilometres northeast of Fredericton. Its population meets ...

;

Amherst, Nova Scotia

Amherst ( ) is a town in northwestern Nova Scotia, Canada, located at the northeast end of the Cumberland Basin, an arm of the Bay of Fundy, and south of the Northumberland Strait. The town sits on a height of land at the eastern boundary of th ...

and

St. John's, Newfoundland.

About 250 people worked as guards at the Amherst, Nova Scotia camp at Park and Hickman streets from April 1915 to September 1919. The prisoners, including

Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

, cleared land around the experimental farm and built the pool in Dickey Park.

World War II (Canada)

During the World War II, the Canadian government interned people of German, Italian and Japanese ancestry, besides citizens of other origins it deemed dangerous to national security. This included both

fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

s (including Canadians such as

Adrien Arcand who had negotiated with

Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

to obtain positions in the government of Canada once Canada was conquered),

Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

mayor

Camillien Houde (for denouncing

conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to Ancient history, antiquity and it continues in some countries to th ...

) and

union organizers and other people deemed to be dangerous

Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

s. Such internment was made legal by the

Defence of Canada Regulations, passed 3 September 1939. Section 21 of which read:

:The Minister of Justice, if satisfied that, with a view to preventing any particular person from acting in a manner prejudicial to the public safety or the safety of the State, it is necessary to do so, may, notwithstanding anything in these regulations, make an order

..directing that he be detained by virtue of an order made under this paragraph, be deemed to be in legal custody.

Internment of Jewish refugees

European refugees who had managed to escape the Nazis and made it to Britain, were rounded up as "enemy aliens" in 1940. Many were interned on the

Isle of Man

)

, anthem = " O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europ ...

, and 2,300 were sent to Canada, mostly Jews. They were transported on the same boats as German and Italian POWs. They were sent to camps in

New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

,

Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

and

Quebec provinces where they were mixed in with Canadian fascists and other political prisoners, Nazi POWs, etc.

German Canadian internment

During the Second World War, 850

German Canadians were accused of being spies for the

Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in N ...

, as well as subversives and saboteurs. The internees were given a chance by authorities to defend themselves; according to the transcripts of the appeal tribunals, internees and state officials debated conflicting concepts of citizenship.

Many German Canadians interned in

Camp Petawawa

Garrison Petawawa is located in Petawawa, Ontario. It is operated as an army base by the Canadian Army.

Garrison facts

The Garrison is located in the Ottawa Valley in Renfrew County, northwest of Ottawa along the western bank of the Ottawa ...

were from a migration in 1876. They had arrived in a small area a year after a Polish migration landed in

Wilno, Ontario. Their hamlet, made up of farmers primarily, was called Germanicus, and is in the bush less than from

Eganville

Eganville is a community occupying a deep limestone valley carved at the Fifth Chute of the Bonnechere River in Renfrew County, Ontario, Renfrew County, Ontario, Canada. Eganville lies within the township of Bonnechere Valley, Ontario, Bonnechere ...

,

Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

. Their farms (homesteads originally) were expropriated by the federal government for no compensation, and the men were imprisoned behind barbed wire in the

AOAT camp. (The

Foymount Air Force Base near

Cormac and Eganville was built on this expropriated land.) Notable was that not one of these homesteaders from 1876 or their descendants had ever visited Germany again after 1876, yet they were accused of being German

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

agents.

756 German sailors, mostly captured in

East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea ...

were sent from camps in India to Canada in June 1941 (''Camp 33).

By 19 April 1941, 61 prisoners had made a break for liberty from Canadian internment camps. The escapees included 28 German prisoners who escaped from the internment camp east of

Port Arthur, Ontario in April 1941.

Italian Canadian internment

On 10 June 1940, Italy joined the war on the Axis side. After that,

Italian Canadians

Italian Canadians ( it, italo-canadesi, french: italo-canadiens) comprise Canadians who have full or partial Italian diaspora, Italian heritage and Italians who Italian diaspora, migrated from Italy or reside in Canada. According to the Canada 20 ...

were heavily scrutinized. Openly fascist organizations were deemed illegal while individuals with fascist inclinations were arrested, most often without warrants. Organizations seen as openly fascist also had properties confiscated without warrants. A provision under the Canadian ''

War Measures Act

The ''War Measures Act'' (french: Loi sur les mesures de guerre; 5 George V, Chap. 2) was a statute of the Parliament of Canada that provided for the declaration of war, invasion, or insurrection, and the types of emergency measures that could t ...

'' was immediately enacted by Prime Minister

William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A L ...

. Named the

Defence of Canada Regulations, it allowed government authorities to take the necessary measures to protect the country from internal threats and enemies. The same afternoon that Italy joined the Axis powers, Italian consular and embassy officials were asked to leave as soon as physically possible. Canada, which was heavily involved in the war effort on the Allies' side, saw the Italian communities as a breeding ground of likely internal threats and a haven of conceivable spy networks helping the fascist Axis nations of Italy and Germany. Though many Italians were anti-fascist and no longer politically involved with their homeland, this did not stop 600–700 Italians from being sent to internment camps throughout Canada.

[Massa, Evelyn Weinfield, Morton: WE NEEDED TO PROVE WE WERE GOOD CANADIANS: CONTRASTING PARADIGMS FOR SUSPECT MINORITIES, pp. 17–19 Canadian Issues Spring 2009.]

The first of these Italian prisoners were sent to Camp Petawawa, in the Ottawa River Valley. By October 1940 the round up had already been completed. Italian Canadian Montrealer, Mario Duliani wrote "The City Without Women" about his life in the internment camp Petawawa during World War II; it is a personal account of the struggles of the time. Throughout the country Italians were investigated by

RCMP

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP; french: Gendarmerie royale du Canada; french: GRC, label=none), commonly known in English as the Mounties (and colloquially in French as ) is the federal and national police service of Canada. As poli ...

officials who had a compiled list of Italian persons who were politically involved and deeply connected in the Italian communities. Most of the arrested individuals were from the Montreal and Toronto areas; they were pronounced

enemy aliens

In customary international law, an enemy alien is any native, citizen, denizen or subject of any foreign nation or government with which a domestic nation or government is in conflict and who is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and ...

.

[Iacovetta, Franca Pg 21–22"> Iacovetta, Franca: Such Hardworking People, pp. 21–23 McGill-Queen's University Press.]

After the war, resentment and suspicion of the Italian communities still lingered. Laval Fortier, commissioner for overseas immigration after the war, wrote: "The Italian South Peasant is not the type we are looking for in Canada. His standard of living, his way of life, even his civilization seem so different that I doubt if he could ever become an asset to our country". Such remarks reflected a large proportion of the population who had negative views of the Italian communities. A

Gallup poll released in 1946 showed 73 percent of Québécois were against immigration, with 25 percent stating Italians were the group of people most wanted kept out — even though the pre-war years had proved that Italians were an asset to the Canadian economy and industry, as they accomplished critical jobs that were seen as very unappealing, such as laying track across rural and dangerous landscapes and building infrastructure in urban areas.

[Iacovetta, Franca Pg 21–22"/>

]

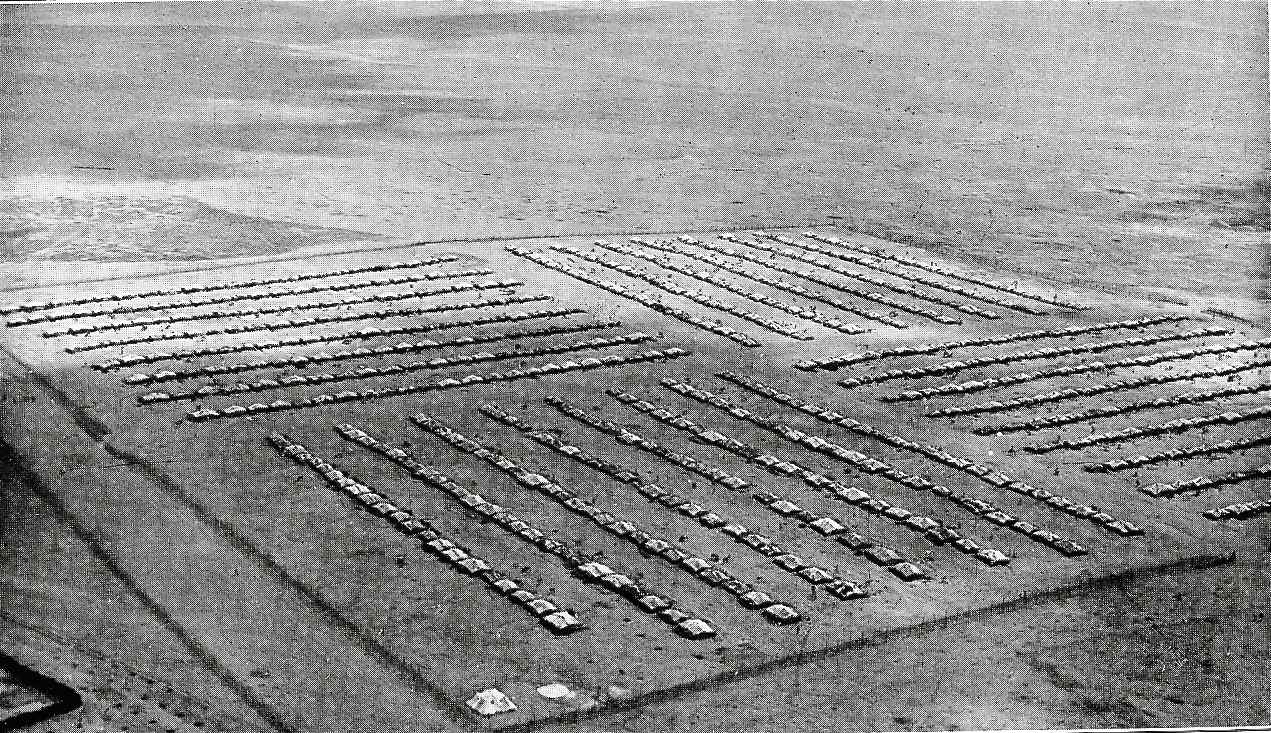

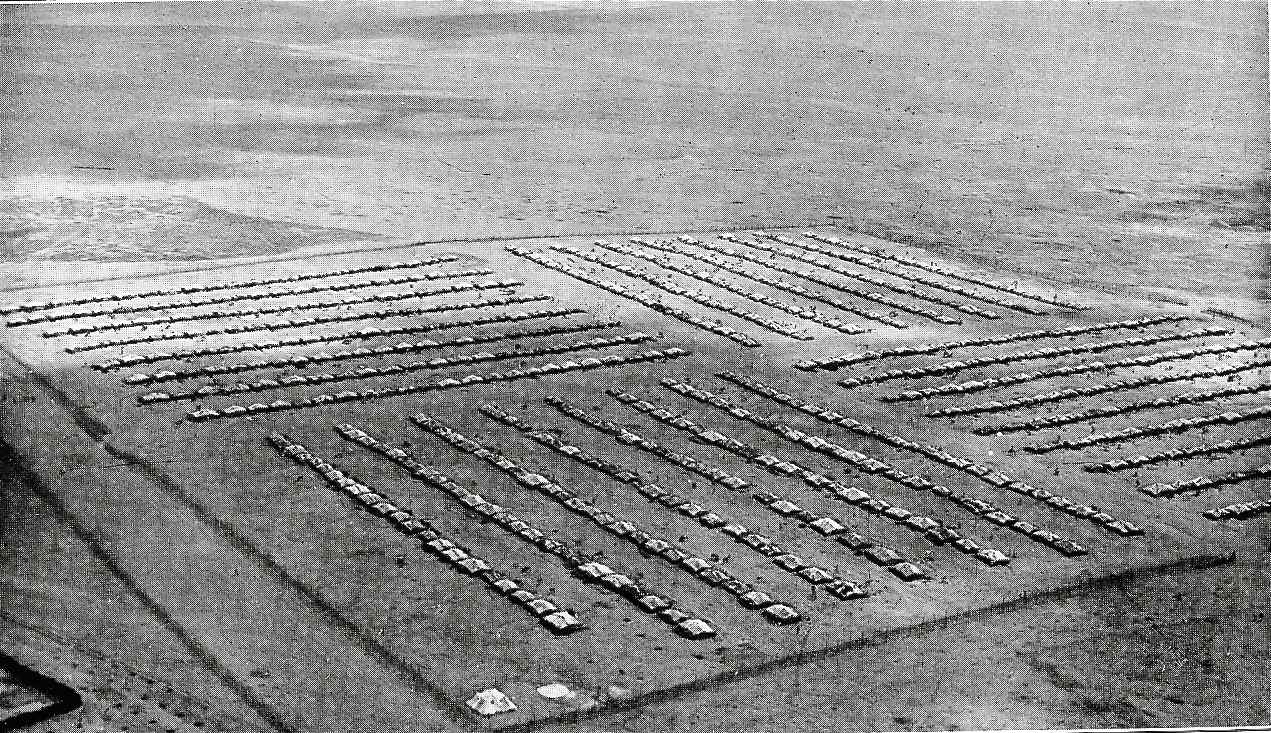

Japanese Canadian internment and relocation centres

During World War II, Canada interned residents of Japanese ancestry. Over 75% were Canadian nationals and they were vital in key areas of the economy, notably the fishery and also logging and berry farming. Exile took two forms: relocation centres for families and relatively well-off individuals who were a low security threat, and internment camps which were for single men, the less well-off, and those deemed to be a security risk. After the war, many did not return to the Coast because of bitter feelings as to their treatment, and fears of further hostility from non-Japanese citizens; of those that returned only about 25% regained confiscated property and businesses. Most remained in other parts of Canada, notably certain parts of the British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

Interior and in the neighbouring province of Alberta.

=Camps and relocation centres in the West Kootenay and Boundary regions

=

Internment camps, called "relocation centres", were at Greenwood, Kaslo, Lemon Creek, New Denver

New Denver is at the mouth of Carpenter Creek, on the east shore of Slocan Lake, in the West Kootenay region of southeastern British Columbia. The village is west of Kaslo on Highway 31A, and southeast of Nakusp and northeast of Slocan o ...

, Rosebery, Sandon, Slocan City

The Village of Slocan is in the West Kootenay region of southeastern British Columbia. The former steamboat landing and ferry terminal is at the mouth of Springer Creek, at the foot of Slocan Lake. The locality, on BC Highway 6 is about by ro ...

, and Tashme

The Tashme Incarceration Camp ( nglicized pronunciationor apanese pronunciation was a purpose-built incarceration camp constructed to forcibly detain people of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast of Canada during World War II after t ...

. Some were nearly-empty ghost towns

Ghost Town(s) or Ghosttown may refer to:

* Ghost town, a town that has been abandoned

Film and television

* ''Ghost Town'' (1936 film), an American Western film by Harry L. Fraser

* ''Ghost Town'' (1956 film), an American Western film by Alle ...

when the internment began, others, like Kaslo and Greenwood, while less populous than in their boom years, were substantial communities.

=Self-supporting centres in the Lillooet-Fraser Canyon region

=

A different kind of camp, known as a self-supporting centre, was found in other regions. Bridge River

The Bridge River is an approximately long river in southern British Columbia. It flows south-east from the Coast Mountains. Until 1961, it was a major tributary of the Fraser River, entering that stream about six miles upstream from the town of ...

, Minto City

Minto City, often called just Minto, sometimes Minto Mines, Minto Mine, Skumakum, or "land of plenty", was a gold mining town in the Bridge River Valley of British Columbia from 1930 to 1936, located at the confluence of that river with Gun Cree ...

, McGillivray Falls McGillivray may refer to:

People

* McGillivray (surname)

Places

* McGillivray Creek (British Columbia), a creek in the Lillooet Country of British Columbia

** McGillivray, British Columbia (formerly McGillivray Falls) in the Lillooet Country of ...

, East Lillooet, Taylor Lake were in the Lillooet Country

The Lillooet Country, also referred to as the Lillooet District, is a region spanning from the central Fraser Canyon town of Lillooet west to the valley of the Lillooet River, and including the valleys in between, in the Southern Interior of Br ...

or nearby. Other than Taylor Lake, these were all called "Self-supporting centres", not internment camps. The first three listed were all in a mountainous area so physically isolated that fences and guards were not required as the only egress from that region was by rail or water. McGillivray Falls and Tashme

The Tashme Incarceration Camp ( nglicized pronunciationor apanese pronunciation was a purpose-built incarceration camp constructed to forcibly detain people of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast of Canada during World War II after t ...

, on the Crowsnest Highway

The Crowsnest Highway is an east-west highway in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada. It stretches across the southern portions of both provinces, from Hope, British Columbia to Medicine Hat, Alberta, providing the shortest highway connectio ...

east of Hope, British Columbia

Hope is a district municipality at the confluence of the Fraser and Coquihalla rivers in the province of British Columbia, Canada. Hope is at the eastern end of both the Fraser Valley and the Lower Mainland region, and is at the southern en ...

, were just over the minimum 100 miles from the Coast required by the deportation order, though Tashme had direct road access over that distance, unlike McGillivray. Because of the isolation of the country immediately coast-wards from McGillivray, men from that camp were hired to work at a sawmill in what has since been named Devine, after the mill's owner, which is within the 100-mile quarantine zone. Many of those in the East Lillooet camp were hired to work in town, or on farms nearby, particularly at Fountain

A fountain, from the Latin "fons" (genitive "fontis"), meaning source or spring, is a decorative reservoir used for discharging water. It is also a structure that jets water into the air for a decorative or dramatic effect.

Fountains were ori ...

, while those at Minto and Minto Mine and those at Bridge River worked for the railway or the hydro company.

Channel Islands

Alderney

Alderney (; french: Aurigny ; Auregnais: ) is the northernmost of the inhabited Channel Islands. It is part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, a British Crown Dependencies, Crown dependency. It is long and wide.

The island's area is , making i ...

in the Channel Islands

The Channel Islands ( nrf, Îles d'la Manche; french: îles Anglo-Normandes or ''îles de la Manche'') are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They include two Crown Dependencies: the Bailiwick of Jersey, ...

was the only place in the British Isles where the Germans established concentration camps during their Occupation of the Channel Islands. In January 1942, the occupying German forces established four camps, called Helgoland, Norderney, Borkum

Borkum ( nds, Borkum, Börkum) is an island and a municipality in the Leer District in Lower Saxony, northwestern Germany. It is situated east of Rottumeroog and west of Juist.

Geography

Borkum is bordered to the west by the Westerems strait ...

and Sylt

Sylt (; da, Sild; Sylt North Frisian, Söl'ring North Frisian: ) is an island in northern Germany, part of Nordfriesland district, Schleswig-Holstein, and well known for the distinctive shape of its shoreline. It belongs to the North Frisian ...

(named after the German North Sea islands), where captive Russians and other East Europeans were used as slave labourers to build the Atlantic Wall

The Atlantic Wall (german: link=no, Atlantikwall) was an extensive system of coastal defences and fortifications built by Nazi Germany between 1942 and 1944 along the coast of continental Europe and Scandinavia as a defence against an anticip ...

defences on the island. Around 460 prisoners died in the Alderney camps.

Chile

* Concentration camps were used during the Selk'nam genocide.

* Concentration camps existed throughout Chile during Pinochet's dictatorship in the 1970s and 80s. An article in Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

Review of Latin America reported that "there were over eighty detention centers in Santiago alone" and it gave details of some. Information on detention centers is included in the Report of the Chilean National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation ( Rettig report).

Some of the detention centers in Chile in this period:

People's Republic of China

Laogai

Laogai (), the abbreviation for (), which means reform through labor, is a criminal justice

Criminal justice is the delivery of justice to those who have been accused of committing crimes. The criminal justice system is a series of government agencies and institutions. Goals include the rehabilitation of offenders, preventing other ...

system involving the use of penal labour and prison farm

A prison farm (also known as a penal farm) is a large correctional facility where penal labor convicts are forced to work on a farm legally and illegally (in the wide sense of a productive unit), usually for manual labor, largely in the open ai ...

s in the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

(PRC). ''Láogǎi'' is different from ''láojiào'', or re-education through labor

Re-education through labor (RTL; ), abbreviated ''laojiao'' () was a system of administrative detention on Mainland China. Active from 1957 to 2013, the system was used to detain persons who were accused of committing minor crimes such as pe ...

, which was the abolished administrative detention system for people who were not criminals but had committed minor offenses, and was intended to "reform offenders into law-abiding citizens".[Chang, Jung and Halliday, Jon. '' Mao: The Unknown Story.'' ]Jonathan Cape

Jonathan Cape is a London publishing firm founded in 1921 by Herbert Jonathan Cape, who was head of the firm until his death in 1960.

Cape and his business partner Wren Howard set up the publishing house in 1921. They established a reputation ...

, London, 2005. p. 338: By the general estimate China's prison and labor camp population was roughly 10 million in any one year under Mao. Descriptions of camp life by inmates, which point to high mortality rates, indicate a probable annual death rate of at least 10 per cent.

[ Rummel, R. J. ]

China’s Bloody Century: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900

'' Transaction Publishers

Transaction Publishers was a New Jersey-based publishing house that specialized in social science books and journals. It was located on the Livingston Campus of Rutgers University. Transaction was sold to Taylor & Francis in 2016 and merged wit ...

, 1991. pp. 214–215[Aikman, David.]

The Laogai Archipelago"

, ''The Weekly Standard

''The Weekly Standard'' was an American neoconservative political magazine of news, analysis and commentary, published 48 times per year. Originally edited by founders Bill Kristol and Fred Barnes, the ''Standard'' had been described as a "re ...

'', September 29, 1997. of deaths and it has also been likened to slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

by its critics.[Chapman, Michael. "Chinese slaves make goods for American malls", ''Human Events,'' 07/04/97, Vol. 53, Issue 25.] The memoirs of Harry Wu

Harry Wu (; February 8, 1937 – April 26, 2016) was a Chinese-American human rights activist. Wu spent 19 years in Chinese labor camps, and he became a resident and citizen of the United States. In 1992, he founded the Laogai Research Foun ...

describe his experience in reform-through-labor prisons from 1960 to 1979. Wu recounts his imprisonment for criticizing the government while he was in college and his release in 1979, after which he moved to the United States and eventually became an activist. Officials of the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

have argued that Wu far overstates the present role of Chinese labor camp

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (espec ...

s and ignores the tremendous changes that have occurred in China since the 1970s.

Falun Gong

The Chinese-language

Chinese (, especially when referring to written Chinese) is a group of languages spoken natively by the ethnic Han Chinese majority and many minority ethnic groups in Greater China. About 1.3 billion people (or approximately 16% of the ...

word '' laogai'', short for ''Láodòng Gǎizào'' ("reform through labor"), referred to penal labour or to prison farm

A prison farm (also known as a penal farm) is a large correctional facility where penal labor convicts are forced to work on a farm legally and illegally (in the wide sense of a productive unit), usually for manual labor, largely in the open ai ...

s in the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

. Chinese authorities dropped the word ''laogai'' itself in 1994 and replaced it with the label "prison".[ Translated from Chinese, original source was ] In the 1960s, critics of the government were arrested and sent to the prisons which were organized like factories. There are accusations that the products of penal labor are sold for profit by the government.Falun Gong

Falun Gong (, ) or Falun Dafa (; literally, "Dharma Wheel Practice" or "Law Wheel Practice") is a new religious movement.Junker, Andrew. 2019. ''Becoming Activists in Global China: Social Movements in the Chinese Diaspora'', pp. 23–24, 33, 119 ...

practitioners being detained at the Sujiatun Thrombosis Hospital, or at the "Sujiatun Concentration Camp". It has been alleged that Falun Gong practitioners are killed for their organs, which are then sold to medical facilities. The Chinese government rejects these allegations. The US State Department visited the alleged camp on two occasions, first unannounced, and found the allegations not credible.[U.S. Finds No Evidence of Alleged Concentration Camp in China]

, U.S. State Department, 16 April 2006 Chinese dissident and Executive Director of the Laogai Research Foundation, Harry Wu

Harry Wu (; February 8, 1937 – April 26, 2016) was a Chinese-American human rights activist. Wu spent 19 years in Chinese labor camps, and he became a resident and citizen of the United States. In 1992, he founded the Laogai Research Foun ...

, having sent his own investigators to the site, was unable to substantiate these claims, and he believed the reports were fabricated.[Harry Wu challenges Falun Gong organ harvesting claims]

, ''South China Morning Post'', 8 September 2006

Xinjiang

at least 120,000 members of China's Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

Uyghur minority were held in mass-detention camps, termed by Chinese authorities " re-education camps", which aim to change the political thinking of detainees, their identities and religious beliefs. According to Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says it has more than ten million members and s ...

and Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization, headquartered in New York City, that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. The group pressures governments, policy makers, companies, and individual human ...

, as many as 1 million people have been detained in these camps, which are located in the Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

region. International reports state that as many as 3 million Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities may have been detained China's re-education camps in the Xinjiang region.

Croatia

World War II (Croatia)

An estimated 320,000–340,000 Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of ...

, 30,000 Croatian Jews

The history of the Jews in Croatia dates back to at least the 3rd century, although little is known of the community until the 10th and 15th centuries. According to the 1931 census, the community numbered 21,505 members, and it is estimated ...

and 30,000 Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

Places Australia

* Roma, Queensland, a town

** Roma Airport

** Roma Courthouse

** Electoral district of Roma, defunct

** Town of Roma, defunct town, now part of the Maranoa Regional Council

* Roma Street, Brisbane, a ...

were killed during the Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia ( sh, Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH; german: Unabhängiger Staat Kroatien; it, Stato indipendente di Croazia) was a World War II-era puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Fascist It ...

, including between 77,000–99,000 Serbs, Bosniaks, Croats, Jews and Roma killed in the Jasenovac concentration camp.

Yugoslav wars

* Kerestinec prison

* Lora prison camp, Split

Cuba

Cuban War of Independence

After Marshal Campos had failed to pacify the Cuban rebellion, the Conservative government of

After Marshal Campos had failed to pacify the Cuban rebellion, the Conservative government of Antonio Cánovas del Castillo

Antonio Cánovas del Castillo (8 February 18288 August 1897) was a Spanish politician and historian known principally for serving six terms as Prime Minister and his overarching role as "architect" of the regime that ensued with the 1874 restor ...

sent out Valeriano Weyler

Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau, 1st Duke of Rubí, 1st Marquess of Tenerife (17 September 1838 – 20 October 1930) was a Spanish general and colonial administrator who served as the Governor-General of the Philippines and Cuba, and later as S ...

. This selection met the approval of most Spaniards, who thought him the proper man to crush the rebellion. While serving as a Spanish general, he was called "Butcher Weyler" because hundreds of thousands of people died in his concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

s.

He was made governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

of Cuba with full powers to suppress the insurgency (rebellion was widespread in Cuba) and restore the island to political order and its sugar production to greater profitability. Initially, Weyler was greatly frustrated by the same factors that had made victory difficult for all generals of traditional standing armies fighting against an insurgency. While the Spanish troops marched in regulation and required substantial supplies, their opponents practiced hit-and-run tactics and lived off the land, blending in with the non-combatant population. He came to the same conclusions as his predecessors as well—that to win Cuba back for Spain, he would have to separate the rebels from the civilians by putting the latter in safe havens, protected by loyal Spanish troops. By the end of 1897, General Weyler had relocated more than 300,000 into such "reconcentration camps." Weyler learned this tactic from the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

campaign of General Sherman while assigned to the post of military attaché in the Spanish Embassy in Washington D.C.. However, many mistakenly believe him to be to the origin of such tactics after it was later used by the British in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

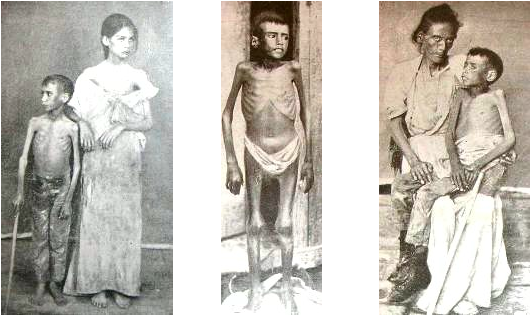

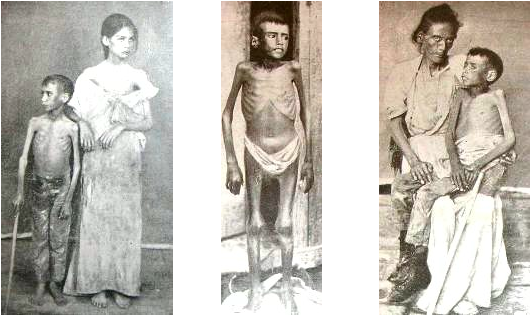

and later evolved into a designation to describe the concentration camps of the 20th century regimes of Hitler and Stalin. Although he was successful moving vast numbers of people, he failed to provide for them adequately. Consequently, these areas became cesspools of hunger and disease, where many hundreds of thousands died.

Weyler's "reconcentration" policy had another important effect. Although it made Weyler's military objectives easier to accomplish, it had devastating political consequences. Although the Spanish Conservative government supported Weyler's tactics wholeheartedly, the Liberals denounced them vigorously for their toll on the Cuban civilian population. In the propaganda war waged in the United States, Cuban émigrés made much of Weyler's inhumanity to their countrymen and won the sympathy of broad groups of the U.S. population to their cause. He was nicknamed "the Butcher" Weyler by journalists like William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

.

Weyler's strategy also backfired militarily due to the rebellion in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

that required the redeployment by 1897 of some troops already in Cuba. When Prime Minister Antonio Cánovas del Castillo

Antonio Cánovas del Castillo (8 February 18288 August 1897) was a Spanish politician and historian known principally for serving six terms as Prime Minister and his overarching role as "architect" of the regime that ensued with the 1874 restor ...

was assassinated in June, Weyler lost his principal supporter in Spain. He resigned his post in late 1897 and returned to Europe. He was replaced in Cuba by the more conciliatory Ramón Blanco y Erenas.

Rule of Fidel Castro

Military Units to Aid Production

Military Units to Aid Production or UMAPs (Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción) were agricultural forced labor camps operated by the Cuban government from November 1965 to July 1968 in the province of Camagüey.Guerra, Lillian. ""Gender ...

were forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

s which were established by Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

's communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

government, from November 1965 to July 1968.

They were used to brainwash the Cuban population and force it to renounce alleged "bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. ...

" and "counter-revolutionary

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revolu ...

" values. First, people were thrown into overcrowded prison cells which were located in police stations and later they were taken to secret police facilities, cinemas, stadiums, warehouses, and similar locations. They were photographed, fingerprinted and forced to sign confessions which declared that they were the "scum of society" in exchange for their temporary release until they were summoned to the concentration camps.homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to pe ...

s, vagrants, Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a millenarian restorationist Christian denomination with nontrinitarian beliefs distinct from mainstream Christianity. The group reports a worldwide membership of approximately 8.7 million adherents involved in ...

and other religious missionaries were imprisoned in these concentration camps, where they would be " reeducated".

Denmark

Before and during World War II

* Horserød camp

Horserød Camp (also Horserød State Prison, Danish: ''Horserødlejren'' or ''Horserød Statsfængsel'') is an open state prison at Horserød, Denmark located in North Zealand, approximately seven kilometers from Helsingør. Built in 1917, Hor ...

– established during World War I as a camp for war prisoners in need of treatment, it was used during World War II as an internment camp. It is now an open prison.

* Frøslev Prison Camp

Frøslev Camp ( da, Frøslevlejren, german: Polizeigefangenenlager Fröslee) was an internment camp in German- occupied Denmark during World War II.

In order to avoid deportation of Danes to German concentration camps, Danish authorities sugg ...

– established during World War II as an internment camp by the Danish government in order to avoid deportation of Danish citizens to Germany. Used after the war to house Nazi collaborators and later students of a continuation high school located inside the camp.

After World War II

Denmark received about 240,000 refugees from Germany and other countries after the war. They were put into camps guarded by the reestablished army. Contact between Danes and the refugees were very limited and strictly enforced. About 17,000 died in the camps caused either by injuries and illness as a result of their escape from Germany or the poor conditions in the camps. Known camps were

* Dragsbæklejren – a base for seaplanes, later converted into an internment camp for refugees. It is now used by the army

* Gedhus – located on an area which now is home to Karup Airport

Midtjyllands Airport ( da, Midtjyllands Lufthavn) , formerly known as Karup Airport, is an airport in Denmark. The airport is situated 3 km west of the town of Karup and carries passengers primarily from nine municipalities in mid- and west ...

* Grove – located on an area which now is home to Karup Airport

Midtjyllands Airport ( da, Midtjyllands Lufthavn) , formerly known as Karup Airport, is an airport in Denmark. The airport is situated 3 km west of the town of Karup and carries passengers primarily from nine municipalities in mid- and west ...

* Rye Flyveplads – a small airfield in Jutland

* Kløvermarken – is now a park in Copenhagen

* Oksbøl Refugee Camp The Oksbøl Refugee Camp was the largest camp for German refugees in Denmark after World War II.

Background

In early 1945 the Red Army started the East Prussian and East Pomeranian Offensives, soon interrupting the overland route to the wes ...

– now belongs to the Danish Army

* Skallerup Klit – was developed into an area for Summer houses

Finland

Finnish Civil War

In the Finnish Civil War

The Finnish Civil War; . Other designations: Brethren War, Citizen War, Class War, Freedom War, Red Rebellion and Revolution, . According to 1,005 interviews done by the newspaper ''Aamulehti'', the most popular names were as follows: Civil W ...

, the victorious White Army and German troops captured about 80,000 Red prisoners by the end of the war on 5 May 1918. Once the White terror subsided, a few thousand including mainly small children and women, were set free, leaving 74,000–76,000 prisoners. The largest prison camps were Suomenlinna

Suomenlinna (; until 1918 Viapori, ), or Sveaborg (), is an inhabited sea fortress the Suomenlinna district is on eight islands of which six have been fortified; it is about 4 km southeast of the city center of Helsinki, the capital of Finl ...

, an island facing Helsinki, Hämeenlinna

Hämeenlinna (; sv, Tavastehus; krl, Hämienlinna; la, Tavastum or ''Croneburgum'') is a city and municipality of about inhabitants in the heart of the historical province of Tavastia and the modern province of Kanta-Häme in the south of ...

, Lahti

Lahti (; sv, Lahtis) is a city and municipality in Finland. It is the capital of the region of Päijänne Tavastia (Päijät-Häme) and its growing region is one of the main economic hubs of Finland. Lahti is situated on a bay at the southern e ...

, Viipuri, Ekenäs, Riihimäki and Tampere

Tampere ( , , ; sv, Tammerfors, ) is a city in the Pirkanmaa region, located in the western part of Finland. Tampere is the most populous inland city in the Nordic countries. It has a population of 244,029; the urban area has a population ...

. The Senate made the decision to keep these prisoners detained until each person's guilt could be examined. A law for a ''Tribunal of Treason'' was enacted on 29 May after a long dispute between the White army and the Senate of the proper trial method to adopt. The start of the heavy and slow process of trials was delayed further until 18 June 1918. The Tribunal did not meet all the standards of neutral justice, due to the mental atmosphere of White Finland after the war. Approximately 70,000 Reds were convicted, mainly for complicity to treason. Most of the sentences were lenient, however, and many got out on parole. 555 persons were sentenced to death, of whom 113 were executed. The trials revealed also that some innocent persons had been imprisoned.

Combined with the severe food shortage, the mass imprisonment led to high mortality rates in the camps, and the catastrophe was compounded by a mentality of punishment, anger and indifference on the part of the victors. Many prisoners felt that they were abandoned also by their own leaders, who had fled to Russia. The condition of the prisoners had weakened rapidly during May, after food supplies had been disrupted during the Red Guards' retreat in April, and a high number of prisoners had been captured already during the first half of April in Tampere and Helsinki. As a consequence, 2,900 starved to death or died in June as a result of diseases caused by malnutrition and Spanish flu

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case wa ...

, 5,000 in July, 2,200 in August, and 1,000 in September. The mortality rate was highest in the Ekenäs camp at 34%, while in the others the rate varied between 5% and 20%. In total, between 11,000 and 13,500 Finns perished. The dead were buried in mass graves near the camps. The majority of the prisoners were paroled or pardoned by the end of 1918 after the victory of the Western powers in World War I also caused a major change in the Finnish domestic political situation. There were 6,100 Red prisoners left at the end of the year, 100 in 1921 (at the same time civil rights were given back to 40,000 prisoners) and in 1927 the last 50 prisoners were pardoned by the social democratic government led by Väinö Tanner. In 1973, the Finnish government paid reparations to 11,600 persons imprisoned in the camps after the civil war.

World War II (Continuation War)

When the

When the Finnish Army

The Finnish Army ( Finnish: ''Maavoimat'', Swedish: ''Armén'') is the land forces branch of the Finnish Defence Forces. The Finnish Army is divided into six branches: the infantry (which includes armoured units), field artillery, anti-aircraf ...

during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

occupied East Karelia

East Karelia ( fi, Itä-Karjala, Karelian: ''Idä-Karjala''), also rendered as Eastern Karelia or Russian Karelia, is a name for the part of Karelia that since the Treaty of Stolbova in 1617 has remained Eastern Orthodox under Russian supremacy ...

from 1941–1944, which was inhabited by ethnically related Finnic Karelians

Karelians ( krl, karjalaižet, karjalazet, karjalaiset, Finnish: , sv, kareler, karelare, russian: Карелы) are a Finnic ethnic group who are indigenous to the historical region of Karelia, which is today split between Finland and Ru ...

(although it never had been a part of Finland—or before 1809 of Swedish Finland), several concentration camps were set up for ethnically Russian civilians. The first camp was set up on 24 October 1941, in Petrozavodsk

Petrozavodsk (russian: Петрозаводск, p=pʲɪtrəzɐˈvotsk; Karelian, Vepsian and fi, Petroskoi) is the capital city of the Republic of Karelia, Russia, which stretches along the western shore of Lake Onega for some . The population ...

. The two largest groups were 6,000 Russian refugees and 3,000 inhabitants from the southern bank of River Svir forcibly evacuated because of the closeness of the front line. Around 4,000 of the prisoners perished due to malnourishment, 90% of them during the spring and summer 1942.[Laine, Antti, ''Suur-Suomen kahdet kasvot'', 1982, , Otava] The ultimate goal was to move the Russian speaking population to German-occupied Russia in exchange for any Finnish population from these areas, and also help to watch civilians.

Population in the Finnish camps:

* 13,400 – 31 December 1941

* 21,984 – 1 July 1942

* 15,241 – 1 January 1943

* 14,917 – 1 January 1944

France

Devil's Island

The Devil's Island

The penal colony of Cayenne (French: ''Bagne de Cayenne''), commonly known as Devil's Island (''Île du Diable''), was a French penal colony that operated for 100 years, from 1852 to 1952, and officially closed in 1953 in the Salvation Island ...

was a network of prisons in French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label= French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic coast of South America in the Guianas ...

that ran from 1852–1953 used to intern petty criminals and political prisoners in which up to 75% of the 80,000 interned perished.

Algeria

During the French conquest of Algeria

The French invasion of Algeria (; ) took place between 1830 and 1903. In 1827, an argument between Hussein Dey, the ruler of the Deylik of Algiers, and the French consul escalated into a blockade, following which the July Monarchy of France inva ...

, which began in 1830 was and fully

completed by 1903, the French used the camps to hold Arabs, Berbers and Turks they had forcibly removed from fertile areas of land, in order to replace them by primarily French, Spanish, and Maltese settlers.Ben Kiernan

Benedict F. "Ben" Kiernan (born 1953) is an Australian-born American academic and historian who is the Whitney Griswold Professor Emeritus of History, Professor of International and Area Studies and Director of the Genocide Studies Program at Yal ...

wrote on the conquest of Algeria: "By 1875, the French conquest was complete. The war killed approximately 825,000 indigenous Algerians since 1830,"

During the Algerian War of Independence

The Algerian War, also known as the Algerian Revolution or the Algerian War of Independence,( ar, الثورة الجزائرية '; '' ber, Tagrawla Tadzayrit''; french: Guerre d'Algérie or ') and sometimes in Algeria as the War of 1 November ...

(1954-1962), the French military created (regrouping centres), which were built settlements for forcibly displaced civilian populations, in order to separate them from National Liberation Front (FLN) guerilla combatants.Le Monde

''Le Monde'' (; ) is a French daily afternoon newspaper. It is the main publication of Le Monde Group and reported an average circulation of 323,039 copies per issue in 2009, about 40,000 of which were sold abroad. It has had its own website si ...

.

Spanish Republicans

After the end of Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

, there were harsh reprisals against Franco's former enemies. Hundreds of thousands of Republicans fled abroad, especially to France and Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

. On the other side of the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

, refugee

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution. s were confined in internment camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

of the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

, such as the Rieucros Camp, Camp de Rivesaltes, Camp Gurs

Gurs internment camp was an internment camp and prisoner of war camp constructed in 1939 in Gurs, a site in southwestern France, not far from Pau. The camp was originally set up by the French government after the fall of Catalonia at the ...

or Camp Vernet, where 12,000 Republicans were housed in squalid conditions (mostly soldiers from the Durruti Division

The Durruti Column (Spanish: ''Columna Durruti''), with about 6,000 people, was the largest anarchist column (or military unit) formed during the Spanish Civil War. During the first months of the war, it became the most recognized and popular mi ...

[''Camp Vernet'' Website](_blank)

). The 17,000 refugees housed in Gurs were divided into four categories (Brigadist

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existe ...

s, pilots, '' Gudaris'' and ordinary Spaniards). The ''Gudaris'' (Basques) and the pilots easily found local backers and jobs, and were allowed to quit the camp, but the farmers and ordinary people, who could not find relations in France, were encouraged by the Third Republic, in agreement with the Francoist government, to return to Spain. The great majority did so and were turned over to the Francoist authorities in Irún. From there they were transferred to the Miranda de Ebro camp for "purification".

After the proclamation by Marshal Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of Worl ...

of the Vichy regime

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...