Lionel Barrymore on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lionel Barrymore (born Lionel Herbert Blythe; April 28, 1878 – November 15, 1954) was an American actor of stage, screen and radio as well as a film director. He won an

Lionel Barrymore (born Lionel Herbert Blythe; April 28, 1878 – November 15, 1954) was an American actor of stage, screen and radio as well as a film director. He won an

"Barrymore, Lionel Herbert"

, Pennsylvania Center for the Book, Penn State University Libraries, 2009, accessed November 15, 2015 While raised a

Reluctant to follow his parents' career,Barrymore (1951), p. 40 Barrymore appeared together with his grandmother

Reluctant to follow his parents' career,Barrymore (1951), p. 40 Barrymore appeared together with his grandmother

Barrymore joined

Barrymore joined  Prior to his marriage to Irene, Barrymore and his brother John engaged in a dispute over the issue of Irene's chastity in the wake of her having been one of John's lovers. The brothers didn't speak again for two years and weren't seen together until the premiere of John's film ''

Prior to his marriage to Irene, Barrymore and his brother John engaged in a dispute over the issue of Irene's chastity in the wake of her having been one of John's lovers. The brothers didn't speak again for two years and weren't seen together until the premiere of John's film '' In a series of Doctor Kildare movies in the 1930s and 1940s, he played the irascible Doctor Gillespie, a role he repeated in an MGM radio series that debuted in New York in 1950 and was later syndicated. Barrymore had broken his hip in an accident, hence he played Gillespie in a wheelchair. Later, his worsening arthritis kept him in the chair. The injury also precluded his playing Ebenezer Scrooge in the 1938 MGM film version of ''

In a series of Doctor Kildare movies in the 1930s and 1940s, he played the irascible Doctor Gillespie, a role he repeated in an MGM radio series that debuted in New York in 1950 and was later syndicated. Barrymore had broken his hip in an accident, hence he played Gillespie in a wheelchair. Later, his worsening arthritis kept him in the chair. The injury also precluded his playing Ebenezer Scrooge in the 1938 MGM film version of ''

Barrymore registered for the draft during World War II, despite his age and disability, to encourage others to enlist in the military.

He loathed the Income tax in the United States, income tax, and by the time he was appearing on ''Mayor of the Town'', MGM withheld a sizable portion of his paychecks, paying back the Internal Revenue Service, IRS the amount he owed.

Barrymore registered for the draft during World War II, despite his age and disability, to encourage others to enlist in the military.

He loathed the Income tax in the United States, income tax, and by the time he was appearing on ''Mayor of the Town'', MGM withheld a sizable portion of his paychecks, paying back the Internal Revenue Service, IRS the amount he owed.

Barrymore also composed music. His works ranged from solo piano pieces to large-scale orchestral works, such as "Tableau Russe," which was performed twice in ''Dr. Kildare's Wedding Day'' (1941) as Cornelia's Symphony, first on piano by Nils Asther's character and later by a full symphony orchestra. His piano compositions, "Scherzo Grotesque" and "Song Without Words", were published by G. Schirmer in 1945. Upon the death of his brother John in 1942, he composed a work "In Memoriam", which was performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra. He also composed the theme song of the radio program '' Mayor of the Town''.

Barrymore had attended art school in New York and Paris and was a skillful graphic artist, creating etchings and drawings and was a member of the Society of American Graphic Artists, Society of American Etchers, now known as the Society of American Graphic Artists. For years, he maintained an artist's shop and studio attached to his home in Los Angeles. Some of his etchings were included in the ''Hundred Prints of the Year''.

He wrote a historical novel, ''Mr. Cantonwine: A Moral Tale'' (1953).

He was also a horticulturalist, growing roses on his Chatsworth Ranch.

Barrymore also composed music. His works ranged from solo piano pieces to large-scale orchestral works, such as "Tableau Russe," which was performed twice in ''Dr. Kildare's Wedding Day'' (1941) as Cornelia's Symphony, first on piano by Nils Asther's character and later by a full symphony orchestra. His piano compositions, "Scherzo Grotesque" and "Song Without Words", were published by G. Schirmer in 1945. Upon the death of his brother John in 1942, he composed a work "In Memoriam", which was performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra. He also composed the theme song of the radio program '' Mayor of the Town''.

Barrymore had attended art school in New York and Paris and was a skillful graphic artist, creating etchings and drawings and was a member of the Society of American Graphic Artists, Society of American Etchers, now known as the Society of American Graphic Artists. For years, he maintained an artist's shop and studio attached to his home in Los Angeles. Some of his etchings were included in the ''Hundred Prints of the Year''.

He wrote a historical novel, ''Mr. Cantonwine: A Moral Tale'' (1953).

He was also a horticulturalist, growing roses on his Chatsworth Ranch.

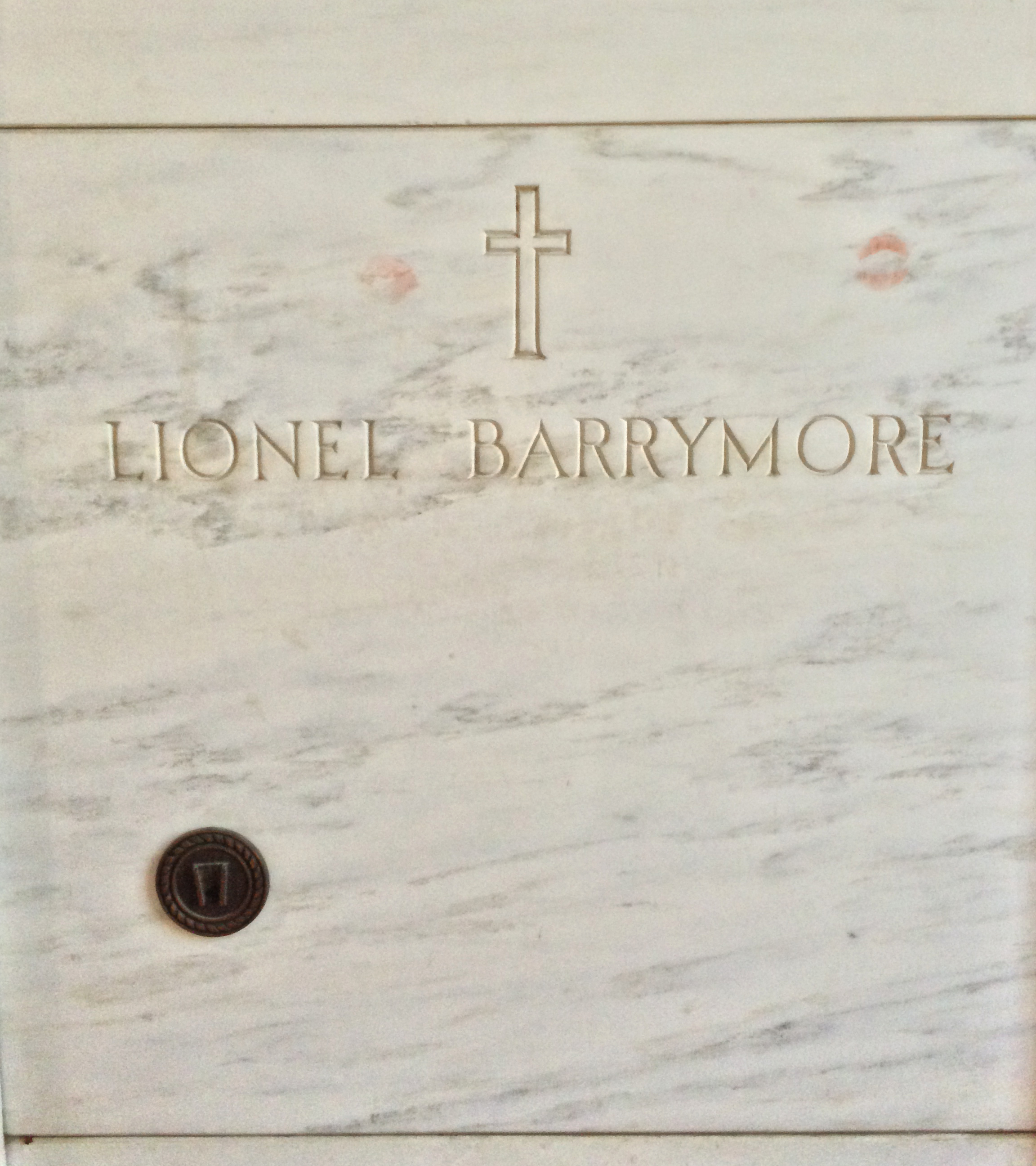

Barrymore died on November 15, 1954, from a myocardial infarction, heart attack in the Van Nuys neighborhood of Los Angeles. He was entombed in the Calvary Cemetery (Los Angeles), Calvary Cemetery in East Los Angeles, California, East Los Angeles.

Barrymore died on November 15, 1954, from a myocardial infarction, heart attack in the Van Nuys neighborhood of Los Angeles. He was entombed in the Calvary Cemetery (Los Angeles), Calvary Cemetery in East Los Angeles, California, East Los Angeles.

Lionel Barrymore - allmovie

*

Photographs of Lionel Barrymore

*

Lionel Barrymore

photo gallery NYP Library

Lionel Barrymore and several other actors on Orson Welles Radio Almanac 1944Lionel Barrymore in 1902 in "The Mummy and the Hummingbird"

portrait by Burr McIntosh for Munseys Magazine

Lionel with brother John Barrymore, 1917 Lionel Barrymore as a child

Lionel Barrymore - Aveleyman

{{DEFAULTSORT:Barrymore, Lionel 1878 births 1954 deaths 19th-century American male actors 20th-century American male actors American male composers American composers American male film actors American printmakers American male radio actors American male silent film actors American male stage actors American people of English descent American people of Irish descent Artists from Pennsylvania Barrymore family, Lionel Best Actor Academy Award winners Burials at Calvary Cemetery (Los Angeles) California Republicans Episcopal Academy alumni Film directors from Pennsylvania Male actors from Philadelphia Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer contract players Musicians from Philadelphia New York (state) Republicans People from Hempstead (village), New York Silent film directors Vaudeville performers Members of The Lambs Club

Lionel Barrymore (born Lionel Herbert Blythe; April 28, 1878 – November 15, 1954) was an American actor of stage, screen and radio as well as a film director. He won an

Lionel Barrymore (born Lionel Herbert Blythe; April 28, 1878 – November 15, 1954) was an American actor of stage, screen and radio as well as a film director. He won an Academy Award for Best Actor

The Academy Award for Best Actor is an award presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). It is given to an actor who has delivered an outstanding performance in a leading role in a film released that year. The ...

for his performance in ''A Free Soul

''A Free Soul'' is a 1931 American pre-Code drama film that tells the story of an alcoholic San Francisco defense attorney who must defend his daughter's ex-boyfriend on a charge of murdering the mobster she had started a relationship with, who ...

'' (1931), and remains best known to modern audiences for the role of villainous Mr. Potter

Henry F. Potter (commonly referred to as Mr. Potter or just Potter) is a fictional character, a villainous robber baron and the main antagonist in the 1946 Frank Capra film ''It's a Wonderful Life.'' He was portrayed by the veteran actor Lione ...

in Frank Capra's 1946 film ''It's a Wonderful Life

''It's a Wonderful Life'' is a 1946 American Christmas fantasy drama film produced and directed by Frank Capra, based on the short story and booklet ''The Greatest Gift'', which Philip Van Doren Stern self-published in 1943 and is in turn loos ...

''.

He is also particularly remembered as Ebenezer Scrooge in annual broadcasts of ''A Christmas Carol'' during his last two decades. He is also known for playing Dr. Leonard Gillespie in MGM's nine Dr. Kildare

Dr. James Kildare is a fictional American medical doctor, originally created in the 1930s by the author Frederick Schiller Faust under the pen name Max Brand. Shortly after the character's first appearance in a magazine story, Paramount Pictur ...

films, a role he reprised in a further six films focusing solely on Gillespie and in a radio series titled ''The Story of Dr. Kildare''. He was a member of the theatrical Barrymore family

The Barrymore family is an American acting family.

The Barrymores are also the inspiration of a Broadway play called ''The Royal Family'', which debuted in 1927. Many members of the Barrymore family are not mentioned in this article. The surnam ...

.

Early life

Lionel Barrymore was born Lionel Herbert Blythe inPhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, the son of actors Georgiana Drew

Georgiana Emma Drew (July 11, 1856 – July 2, 1893), Georgie Drew Barrymore, was an American stage actress and comedian and a member of the Barrymore acting family.

Life and career

Born in Philadelphia, her family — parents John Drew and L ...

Barrymore and Maurice Barrymore

Herbert Arthur Chamberlayne Blythe (21 September 1849 – 25 March 1905), known professionally by his stage name Maurice Barrymore, was an Indian-born British stage actor. He is the patriarch of the Barrymore acting family, father of John, Li ...

(born Herbert Arthur Chamberlayne Blythe). He was the elder brother of Ethel

Ethel (also '' æthel'') is an Old English word meaning "noble", today often used as a feminine given name.

Etymology and historic usage

The word means ''æthel'' "noble".

It is frequently attested as the first element in Anglo-Saxon names, b ...

and John Barrymore

John Barrymore (born John Sidney Blyth; February 14 or 15, 1882 – May 29, 1942) was an American actor on stage, screen and radio. A member of the Drew and Barrymore theatrical families, he initially tried to avoid the stage, and briefly att ...

, the uncle of John Drew Barrymore

John Drew Barrymore (born John Blyth Barrymore Jr.; June 4, 1932 – November 29, 2004) was an American film actor and member of the Barrymore family of actors, which included his father, John Barrymore, and his father's siblings, Lionel and E ...

and Diana Barrymore

Diana Blanche Barrymore Blythe (March 3, 1921 – January 25, 1960), known professionally as Diana Barrymore, was an American film and stage actress.

Early life

Born Diana Blanche Barrymore Blythe in New York, New York, Diana Barrymore was t ...

and the great-uncle of Drew Barrymore

Drew Blythe Barrymore (born February 22, 1975) is an American actress, director, producer, talk show host and author. A member of the Barrymore family of actors, she is the recipient of several accolades, including a Golden Globe Award and a ...

, among other members of the Barrymore family

The Barrymore family is an American acting family.

The Barrymores are also the inspiration of a Broadway play called ''The Royal Family'', which debuted in 1927. Many members of the Barrymore family are not mentioned in this article. The surnam ...

. He attended private schools as a child, including the Art Students League of New York

The Art Students League of New York is an art school at 215 West 57th Street in Manhattan, New York City, New York. The League has historically been known for its broad appeal to both amateurs and professional artists.

Although artists may stu ...

.Foster, Cherika and Lindley Homol"Barrymore, Lionel Herbert"

, Pennsylvania Center for the Book, Penn State University Libraries, 2009, accessed November 15, 2015 While raised a

Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

, Barrymore attended the Episcopal Academy

The Episcopal Academy, founded in 1785, is a private, co-educational school for grades Pre-K through 12 based in Newtown Square, Pennsylvania. Prior to 2008, the main campus was located in Merion Station and the satellite campus was located in D ...

in Philadelphia. Barrymore graduated from Seton Hall Preparatory School, the Roman Catholic college prep school, in the class of 1891.

He was married twice, to actresses Doris Rankin

Doris Marie Rankin (August 24, 1887 – March 18, 1947) was an American stage and film actress.

Biography

Born in New York City, Rankin was the daughter of actor McKee Rankin and Mabel Bert. She was married to actor Lionel Barrymore from 190 ...

and Irene Fenwick

Irene Fenwick (born Irene Frizell; September 5, 1887 – December 24, 1936) was an American stage and silent film actress. She was married to Lionel Barrymore from 1923 until her death in 1936. Fenwick has several surviving feature films fr ...

, a one-time lover of his brother, John. Doris's sister Gladys was married to Lionel's uncle Sidney Drew

Mr. & Mrs. Sidney Drew were an American comedy team on stage and screen. The team initially consisted of Sidney Drew (August 28, 1863 – April 9, 1919) and his first wife Gladys Rankin (October 8, 1870 – January 9, 1914). After Gladys died in 19 ...

, which made Gladys both his aunt and sister-in-law. Doris Rankin bore Lionel two daughters, Ethel Barrymore II (1908 – 1910) and Mary Barrymore (1916 – 1917). Neither child survived infancy. Barrymore never truly recovered from the deaths of his girls, and their loss undoubtedly strained his marriage to Doris Rankin, which ended in 1923. Years later, Barrymore developed a fatherly affection for Jean Harlow

Jean Harlow (born Harlean Harlow Carpenter; March 3, 1911 – June 7, 1937) was an American actress. Known for her portrayal of "bad girl" characters, she was the leading sex symbol of the early 1930s and one of the defining figures of the ...

, who was born about the same time as his daughters. When Harlow died in 1937, Barrymore and Clark Gable

William Clark Gable (February 1, 1901November 16, 1960) was an American film actor, often referred to as "The King of Hollywood". He had roles in more than 60 motion pictures in multiple genres during a career that lasted 37 years, three decades ...

mourned her as though she had been family.

Stage career

Reluctant to follow his parents' career,Barrymore (1951), p. 40 Barrymore appeared together with his grandmother

Reluctant to follow his parents' career,Barrymore (1951), p. 40 Barrymore appeared together with his grandmother Louisa Lane Drew

Louisa Lane Drew (January 10, 1820 – August 31, 1897) was an English-born American actress and theatre owner and an ancestor of the Barrymore acting family. Professionally she was often known as Mrs. John Drew.

Life and career

Louisa L ...

on tour and in a stage production of ''The Rivals

''The Rivals'' is a comedy of manners by Richard Brinsley Sheridan in five acts which was first performed at Covent Garden Theatre on 17 January 1775. The story has been updated frequently, including a 1935 musical and a 1958 List of Maverick ...

'' at the age of 15. He later recounted that "I didn't want to act. I wanted to paint or draw. The theater was not in my blood, I was related to the theater by marriage only; it was merely a kind of ''in-law'' of mine I had to live with." Nevertheless, he soon found success on stage in character roles and continued to act, although he still wanted to become a painter and also to compose music. He appeared on Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

in his early twenties with his uncle John Drew Jr. in such plays as ''The Second in Command'' (1901) and ''The Mummy and the Hummingbird'' (1902), the latter of which won him critical acclaim. Both were produced by Charles Frohman

Charles Frohman (July 15, 1856 – May 7, 1915) was an American theater manager and producer, who discovered and promoted many stars of the American stage. Notably, he produced ''Peter Pan'', both in London and the US, the latter production ...

, who produced other plays for Barrymore and his siblings, John and Ethel. ''The Other Girl'' in 1903–04 was a long-running success for Barrymore. In 1905, he appeared with John and Ethel in a pantomime

Pantomime (; informally panto) is a type of musical comedy stage production designed for family entertainment. It was developed in England and is performed throughout the United Kingdom, Ireland and (to a lesser extent) in other English-speaking ...

, starring as the title character in ''Pantaloon'' and playing another character in the other half of the bill, ''Alice Sit-by-the-Fire''.

In 1906, after a series of disappointing appearances in plays, Barrymore and his first wife, the actress Doris Rankin

Doris Marie Rankin (August 24, 1887 – March 18, 1947) was an American stage and film actress.

Biography

Born in New York City, Rankin was the daughter of actor McKee Rankin and Mabel Bert. She was married to actor Lionel Barrymore from 190 ...

, left their stage careers and travelled to Paris, where he trained as an artist. Lionel and Doris were in Paris in 1908 where their first baby, Ethel, was born. Lionel confirms in his autobiography, ''We Barrymores'', that he and Doris were in France when Bleriot flew the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

on July 25, 1909. He did not achieve success as a painter, and in 1909 he returned to the US. In December of that year, he returned to the stage in ''The Fires of Fate'', in Chicago, but left the production later that month after suffering an attack of nerves about the forthcoming New York opening. The producers gave appendicitis

Appendicitis is inflammation of the appendix. Symptoms commonly include right lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and decreased appetite. However, approximately 40% of people do not have these typical symptoms. Severe complications of a rup ...

as the reason for his sudden departure. Nevertheless, he was soon back on Broadway in ''The Jail Bird'' in 1910 and continued his stage career with several more plays. He also joined his family troupe, from 1910, in their vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition ...

act, where he was happy not to worry as much about memorizing lines.

From 1912 to 1917, Barrymore was away from the stage again while he established his film career, but after the First World War, he had several successes on Broadway, where he established his reputation as a dramatic and character actor, often performing together with his wife. He returned to the stage in ''Peter Ibbetson

''Peter Ibbetson'' is a 1935 American black-and-white drama/ fantasy film directed by Henry Hathaway and starring Gary Cooper and Ann Harding. The film is loosely based on the 1891 novel of the same name by George du Maurier. A tale of a love th ...

'' (1917) with his brother John and achieved star billing in ''The Copperhead'' (1918) (with Doris). He retained star billing for the next 6 years in plays such as ''The Jest'' (1919) (again with John) and ''The Letter of the Law'' (1920). Lionel gave a short-lived performance as MacBeth in 1921 opposite veteran actress Julia Arthur

Julia Arthur (May 3, 1869 – March 28, 1950)Although 1868 is accepted as the year of her birth, both ''The National Cyclopaedia of National Biography'' and ''Who Was Who in America'' give 1869 as the year. was a Canadian-born stage and film ac ...

as Lady MacBeth, but the production encountered strongly negative criticism. His last stage success was in ''Laugh, Clown, Laugh'', in 1923, with his second wife, Irene Fenwick; they met while acting together in ''The Claw'' the previous year, and after they fell in love he divorced his first wife. He also received negative notices in three productions in a row in 1925. After appearing in ''Man or Devil'' in 1926, he signed a film contract with MGM

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded on April 17, 1924 a ...

and after the advent of sound films in 1927, he never again appeared on stage.

Film career

Barrymore joined

Barrymore joined Biograph Studios

Biograph Studios was an early film studio and laboratory complex, built in 1912 by the Biograph Company at 807 East 175th Street, in The Bronx, New York City, New York.

History

Early years

The first studio of the Biograph Company, formerly ...

in 1909 and began to appear in leading roles by 1911 in films directed by D. W. Griffith. Barrymore made '' The Battle'' (1911), ''The New York Hat

''The New York Hat'' is a silent short film which was released in 1912, directed by D. W. Griffith from a screenplay by Anita Loos, and starring Mary Pickford, Lionel Barrymore, and Lillian Gish.

Production

''The New York Hat'' is one of the mo ...

'' (1912), ''Friends

''Friends'' is an American television sitcom created by David Crane and Marta Kauffman, which aired on NBC from September 22, 1994, to May 6, 2004, lasting ten seasons. With an ensemble cast starring Jennifer Aniston, Courteney Cox, Lisa ...

'', and '' Three Friends'' (1913). In 1915, he co-starred with Lillian Russell

Lillian Russell (born Helen Louise Leonard; December 4, 1860 or 1861 – June 6, 1922), was an American actress and singer. She became one of the most famous actresses and singers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, known for her beauty ...

in a movie called ''Wildfire

A wildfire, forest fire, bushfire, wildland fire or rural fire is an unplanned, uncontrolled and unpredictable fire in an area of Combustibility and flammability, combustible vegetation. Depending on the type of vegetation present, a wildfire ...

'', one of the legendary Russell's few film appearances. He also was involved in writing and directing at Biograph. The last silent film he directed, '' Life's Whirlpool'' (Metro Pictures

Metro Pictures Corporation was a motion picture production company founded in early 1915 in Jacksonville, Florida. It was a forerunner of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The company produced its films in New York, Los Angeles, and sometimes at leased f ...

, 1917), starred his sister, Ethel. He acted in more than 60 silent films with Griffith.

#

In 1920, Barrymore reprised his stage role in the film adaptation of '' The Copperhead''. Also in 1920, he starred in the lead role of '' The Master Mind'', with Gypsy O'Brien

Gypsy O'Brien (1889–1975) was a theater and film actress. Her theater performances included a role in '' Cheating Cheaters''. She also appeared in ''Bunny'' at the Hudson Theatre. Her performance as the persecuted heroine was described as pret ...

co-starring.

Before the formation of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by amazon (company), Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded o ...

in 1924, Barrymore forged a good relationship with Louis B. Mayer

Louis Burt Mayer (; born Lazar Meir; July 12, 1882 or 1884 or 1885 – October 29, 1957) was a Canadian-American film producer and co-founder of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios (MGM) in 1924. Under Mayer's management, MGM became the film industr ...

early on at Metro Pictures

Metro Pictures Corporation was a motion picture production company founded in early 1915 in Jacksonville, Florida. It was a forerunner of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The company produced its films in New York, Los Angeles, and sometimes at leased f ...

. He made several silent features for Metro, some surviving, some now lost. In 1923, Barrymore and Fenwick went to Italy to film '' The Eternal City'' for Metro Pictures in Rome, combining work with their honeymoon. He occasionally freelanced, returning to Griffith in 1924 to film ''America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

''. In 1924, he also went to Germany to star in British producer-director Herbert Wilcox

Herbert Sydney Wilcox Order of the British Empire, CBE (19 April 1890 – 15 May 1977) was a British film producer and film director, director.

He was one of the most successful British filmmakers from the 1920s to the 1950s. He is best know ...

's Anglo-German co-production ''Decameron Nights

''Decameron Nights'' is a 1953 anthology Technicolor film based on three tales from ''The Decameron'' by Giovanni Boccaccio, specifically the ninth and tenth tales of the second day and the ninth tale of the third. It stars Joan Fontaine and, a ...

'', filmed at UFA

Ufa ( ba, Өфө , Öfö; russian: Уфа́, r=Ufá, p=ʊˈfa) is the largest city and capital city, capital of Bashkortostan, Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Belaya River (Kama), Belaya and Ufa River, Ufa rivers, in the centre-n ...

's Babelsberg studios outside of Berlin. In 1925, he left New York for Hollywood. He starred as Frederick Harmon in director Henri Diamant-Berger's drama '' Fifty-Fifty'' (1925) opposite Hope Hampton

Hope Hampton (Mae Elizabeth Hampton; February 19, 1897 – January 23, 1982) was an American silent motion picture actress and producer, who was noted for her seemingly effortless incarnation of siren and flapper types in silent-picture roles ...

and Louise Glaum

Louise Glaum (September 4, 1888 – November 25, 1970) was an American actress. Known for her roles as a vamp in silent era motion picture dramas, she was credited with giving one of the best characterizations of a vamp in her early career ...

, and made several more freelance motion pictures, including '' The Bells'' (Chadwick Pictures

Chadwick Pictures was an American film production and distribution company active during the silent and early sound eras. It was originally established in New York by Isaac E. Chadwick (1884 – 1952) in 1920 to release films, but from 1924 als ...

, 1926) with a then-unknown Boris Karloff

William Henry Pratt (23 November 1887 – 2 February 1969), better known by his stage name Boris Karloff (), was an English actor. His portrayal of Frankenstein's monster in the horror film ''Frankenstein'' (1931) (his 82nd film) established h ...

. His last film for Griffith was 1928's ''Drums of Love

''Drums of Love'' (1928) is a silent romance film directed by D. W. Griffith.

Plot

After finding out her father and his estate is in danger, Princess Emanuella saves his life by marrying Duke Cathos de Alvia, a grotesque hunchback. She actually ...

''.

Prior to his marriage to Irene, Barrymore and his brother John engaged in a dispute over the issue of Irene's chastity in the wake of her having been one of John's lovers. The brothers didn't speak again for two years and weren't seen together until the premiere of John's film ''

Prior to his marriage to Irene, Barrymore and his brother John engaged in a dispute over the issue of Irene's chastity in the wake of her having been one of John's lovers. The brothers didn't speak again for two years and weren't seen together until the premiere of John's film ''Don Juan

Don Juan (), also known as Don Giovanni ( Italian), is a legendary, fictional Spanish libertine who devotes his life to seducing women. Famous versions of the story include a 17th-century play, ''El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra'' ...

'' in 1926, by which time they had patched up their differences. In 1926, Barrymore signed for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and his first picture there was ''The Barrier

The Barrier is a lava dam retaining the Garibaldi Lake system in southwestern British Columbia, Canada. It is over thick and about long where it impounds the lake.

The area below and adjacent to The Barrier is considered hazardous due to the u ...

''. His first talking picture was ''The Lion and the Mouse

The Lion and the Mouse is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 150 in the Perry Index. There are also Eastern variants of the story, all of which demonstrate mutual dependence regardless of size or status. In the Renaissance the fable was provided w ...

''; his stage experience allowed him to excel in delivering the dialogue in sound films.

On the occasional loan-out, Barrymore had a big success with Gloria Swanson

Gloria May Josephine Swanson (March 27, 1899April 4, 1983) was an American actress and producer. She first achieved fame acting in dozens of silent films in the 1920s and was nominated three times for the Academy Award for Best Actress, most f ...

in 1928's '' Sadie Thompson'' and the aforementioned Griffith film, ''Drums of Love''. In 1929, he returned to directing films. During this early and imperfect sound film period, he directed the controversial ''His Glorious Night

''His Glorious Night'' is a 1929 pre-Code American romance film directed by Lionel Barrymore and starring John Gilbert in his first released talkie. The film is based on the 1928 play ''Olympia'' by Ferenc Molnár.

''His Glorious Night'' has ...

'', with John Gilbert; ''Madame X

''Madame X'' (original title ''La Femme X'') is a 1908 play by French playwright Alexandre Bisson (1848–1912). It was novelized in English and adapted for the American stage; it was also adapted for the screen twelve times over sixty-five ...

'', starring Ruth Chatterton

Ruth Chatterton (December 24, 1892 – November 24, 1961) was an American stage, film, and television actress, aviator and novelist. She was at her most popular in the early to mid-1930s, and in the same era gained prominence as an aviator, ...

; and ''The Rogue Song

''The Rogue Song'' is a 1930 American pre-Code romantic and musical film that tells the story of a Russian bandit who falls in love with a princess, but takes his revenge on her when her brother rapes and kills his sister. The Metro-Goldwyn-Maye ...

'', Laurel and Hardy

Laurel and Hardy were a British-American Double act, comedy duo act during the early Classical Hollywood cinema, Classical Hollywood era of American cinema, consisting of Englishman Stan Laurel (1890–1965) and American Oliver Hardy (1892–19 ...

's first color film. He was credited with being the first director to move a microphone on a sound stage. Barrymore returned to acting in front of the camera in 1931. In that year, he won an Academy Award

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

for his role as an alcoholic lawyer in ''A Free Soul

''A Free Soul'' is a 1931 American pre-Code drama film that tells the story of an alcoholic San Francisco defense attorney who must defend his daughter's ex-boyfriend on a charge of murdering the mobster she had started a relationship with, who ...

'' (1931), after being considered in 1930 for Best Director Best Director is the name of an award which is presented by various film, television and theatre organizations, festivals, and people's awards. It may refer to:

Film awards

* AACTA Award for Best Direction

* Academy Award for Best Director

* BA ...

for ''Madame X''. He played alongside Greta Garbo in the 1931 film “Mata Hari”. He could play many characters, like the evil Rasputin

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (; rus, links=no, Григорий Ефимович Распутин ; – ) was a Russian mystic and self-proclaimed holy man who befriended the family of Nicholas II, the last Emperor of Russia, thus ga ...

in the 1932 ''Rasputin and the Empress

''Rasputin and the Empress'' is a 1932 American pre-Code film directed by Richard Boleslawski and written by Charles MacArthur. Produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), the film is set in Imperial Russia and stars the Barrymore siblings (John, a ...

'' (in which he co-starred for the only time with siblings John and Ethel) and the ailing Oliver Jordan in '' Dinner at Eight'' (1933 — also with John, although they had no scenes together). He played Professor Zelen, the Occultist expert, in the classic horror '' Mark of the Vampire'' (1935).

During the 1930s and 1940s, he became stereotyped as a grouchy but sweet elderly man in such films as ''The Mysterious Island

''The Mysterious Island'' (french: L'Île mystérieuse) is a novel by Jules Verne, published in 1875. The original edition, published by Hetzel, contains a number of illustrations by Jules Férat. The novel is a crossover sequel to Verne's f ...

'' (1929), ''Grand Hotel A grand hotel is a large and luxurious hotel, especially one housed in a building with traditional architectural style. It began to flourish in the 1800s in Europe and North America.

Grand Hotel may refer to:

Hotels Africa

* Grande Hotel Beir ...

'' (1932, with John Barrymore), Little Colonel (1935), ''Captains Courageous

''Captains Courageous: A Story of the Grand Banks'' is an 1897 novel by Rudyard Kipling that follows the adventures of fifteen-year-old Harvey Cheyne Jr., the spoiled son of a railroad tycoon, after he is saved from drowning by a Portuguese f ...

'' (1937), '' You Can't Take It with You'' (1938), ''On Borrowed Time

''On Borrowed Time'' is a 1939 film about the role death plays in life, and how humanity cannot live without it. It is adapted from Paul Osborn's 1938 Broadway hit play. The play, based on a novel by Lawrence Edward Watkin, has been revived twi ...

'' (1939, with Cedric Hardwicke

Sir Cedric Webster Hardwicke (19 February 1893 – 6 August 1964) was an English stage and film actor whose career spanned nearly 50 years. His theatre work included notable performances in productions of the plays of Shakespeare and Shaw, and ...

), '' Duel in the Sun'' (1946), '' Three Wise Fools'' (1946), and ''Key Largo

Key Largo ( es, Cayo Largo) is an island in the upper Florida Keys archipelago and is the largest section of the keys, at long. It is one of the northernmost of the Florida Keys in Monroe County, and the northernmost of the keys connected b ...

'' (1948).

In a series of Doctor Kildare movies in the 1930s and 1940s, he played the irascible Doctor Gillespie, a role he repeated in an MGM radio series that debuted in New York in 1950 and was later syndicated. Barrymore had broken his hip in an accident, hence he played Gillespie in a wheelchair. Later, his worsening arthritis kept him in the chair. The injury also precluded his playing Ebenezer Scrooge in the 1938 MGM film version of ''

In a series of Doctor Kildare movies in the 1930s and 1940s, he played the irascible Doctor Gillespie, a role he repeated in an MGM radio series that debuted in New York in 1950 and was later syndicated. Barrymore had broken his hip in an accident, hence he played Gillespie in a wheelchair. Later, his worsening arthritis kept him in the chair. The injury also precluded his playing Ebenezer Scrooge in the 1938 MGM film version of ''A Christmas Carol

''A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas'', commonly known as ''A Christmas Carol'', is a novella by Charles Dickens, first published in London by Chapman & Hall in 1843 and illustrated by John Leech. ''A Christmas C ...

'', a role Barrymore played every year but two (replaced by brother John Barrymore in 1936 and replaced by Orson Welles in 1938) on the radio from 1934 through 1953. He also played the title role in the 1940s radio series '' Mayor of the Town''.

He is well-known for his role as Mr. Potter

Henry F. Potter (commonly referred to as Mr. Potter or just Potter) is a fictional character, a villainous robber baron and the main antagonist in the 1946 Frank Capra film ''It's a Wonderful Life.'' He was portrayed by the veteran actor Lione ...

, the miserly and mean-spirited banker in ''It's a Wonderful Life

''It's a Wonderful Life'' is a 1946 American Christmas fantasy drama film produced and directed by Frank Capra, based on the short story and booklet ''The Greatest Gift'', which Philip Van Doren Stern self-published in 1943 and is in turn loos ...

'' (1946) opposite James Stewart.

He had a role with Clark Gable

William Clark Gable (February 1, 1901November 16, 1960) was an American film actor, often referred to as "The King of Hollywood". He had roles in more than 60 motion pictures in multiple genres during a career that lasted 37 years, three decades ...

in '' Lone Star'' in 1952. His final film appearance was a cameo in ''Main Street to Broadway

''Main Street to Broadway'' is a 1953 American romantic musical comedy-drama film by independent producer Lester Cowan, his final credit, in collaboration with The Council of the Living Theatre, which provided tie-up with a number of well-known ...

'', an MGM musical comedy released in 1953. His sister Ethel

Ethel (also '' æthel'') is an Old English word meaning "noble", today often used as a feminine given name.

Etymology and historic usage

The word means ''æthel'' "noble".

It is frequently attested as the first element in Anglo-Saxon names, b ...

also appeared in the film.

Politics

Barrymore was aRepublican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

. In 1944

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

January

* January 2 – WWII:

** Free French General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny is appointed to command French Army B, part of the Sixth United States Army Group in Nor ...

, he attended the massive rally organized by David O. Selznick in the Los Angeles Coliseum

The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum (also known as the L.A. Coliseum) is a multi-purpose stadium in the Exposition Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. Conceived as a hallmark of civic pride, the Coliseum was commissioned in 1921 as a me ...

in support of the Thomas E. Dewey, Dewey-John W. Bricker, Bricker ticket as well as governor of California, Governor Earl Warren of California, who would become Dewey's running mate in 1948 and later the Chief Justice of the United States. The gathering drew 93,000, with Cecil B. DeMille as the master of ceremonies and with short speeches by Hedda Hopper and Walt Disney. Among the others in attendance were Ann Sothern, Ginger Rogers, Randolph Scott, Adolphe Menjou, Gary Cooper, Edward Arnold (actor), Edward Arnold, William Bendix, and Walter Pidgeon.

Barrymore registered for the draft during World War II, despite his age and disability, to encourage others to enlist in the military.

He loathed the Income tax in the United States, income tax, and by the time he was appearing on ''Mayor of the Town'', MGM withheld a sizable portion of his paychecks, paying back the Internal Revenue Service, IRS the amount he owed.

Barrymore registered for the draft during World War II, despite his age and disability, to encourage others to enlist in the military.

He loathed the Income tax in the United States, income tax, and by the time he was appearing on ''Mayor of the Town'', MGM withheld a sizable portion of his paychecks, paying back the Internal Revenue Service, IRS the amount he owed.

Medical issues

Several sources argue that arthritis alone confined Barrymore to a wheelchair.Norden, p. 145. Film historian Jeanine Basinger says that his arthritis was serious by at least 1928, when Barrymore made ''Sadie Thompson''. Film historian David Wallace says it was well known that Barrymore was addicted to morphine due to arthritis by 1929. A history of Oscar-winning actors, however, says Barrymore was only suffering from arthritis, not crippled or incapacitated by it. Marie Dressler biographer Matthew Kennedy notes that when Barrymore won his Best Actor Oscar award in 1931, the arthritis was still so minor that it only made him limp a little as he went on stage to accept the honor. Barrymore can be seen being quite physical in late silent films like ''The Thirteenth Hour (1927 film), The Thirteenth Hour'' and ''West of Zanzibar (1928 film), West of Zanzibar'', where he can be seen climbing out of a window. Paul Donnelly says Barrymore's inability to walk was caused by a drawing table falling on him in 1936, breaking Barrymore's hip. Barrymore tripped over a cable while filming ''Saratoga (film), Saratoga'' in 1937 and broke his hip again. (Film historian Robert Osborne says Barrymore also suffered a broken kneecap.)Osborne, p. 31. The injury was so painful that Donnelly, quoting Barrymore, says thatLouis B. Mayer

Louis Burt Mayer (; born Lazar Meir; July 12, 1882 or 1884 or 1885 – October 29, 1957) was a Canadian-American film producer and co-founder of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios (MGM) in 1924. Under Mayer's management, MGM became the film industr ...

bought $400 worth of cocaine for Barrymore every day to help him cope with the pain and allow him to sleep.Donnelly, p. 68. Author David Schwartz says the hip fracture never healed, which was why Barrymore could not walk, and MGM historian John Douglas Eames describes the injury as "crippling". Barrymore himself said in 1951, that it was breaking his hip twice that kept him in the wheelchair. He said he had no other problems, and that the hip healed well, but it made walking exceptionally difficult. Film historian Allen Eyles reached the same conclusion.

Lew Ayres biographer Lesley Coffin and Louis B. Mayer biographer Scott Eyman argue that it was the combination of the broken hip and Barrymore's worsening arthritis that put him in a wheelchair.Eyman, p. 219 Barrymore family biographer Margot Peters says Gene Fowler and James Doane said Barrymore's arthritis was caused by syphilis, which they say he contracted in 1925. Eyman, however, explicitly rejects this hypothesis.

Whatever the cause, Barrymore's performance in ''Captains Courageous'' in 1937 was one of the last times he would be seen standing and walking unassisted. Afterward, Barrymore was able to get about for a short period of time on crutches even though he was in great pain. During the filming of 1938's ''You Can't Take It With You'', the pain of standing with crutches was so severe that Barrymore required hourly shots of painkillers. By 1938, Barrymore's disability forced him to relinquish the role of Ebenezer Scrooge (a role he made famous on the radio) to British actor Reginald Owen in the MGM film version of ''A Christmas Carol''. From then on, Barrymore used a wheelchair exclusively and never walked again. He could, however, stand for short periods of time such as at his brother's funeral in 1942.

Composer; graphic artist; novelist

Barrymore also composed music. His works ranged from solo piano pieces to large-scale orchestral works, such as "Tableau Russe," which was performed twice in ''Dr. Kildare's Wedding Day'' (1941) as Cornelia's Symphony, first on piano by Nils Asther's character and later by a full symphony orchestra. His piano compositions, "Scherzo Grotesque" and "Song Without Words", were published by G. Schirmer in 1945. Upon the death of his brother John in 1942, he composed a work "In Memoriam", which was performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra. He also composed the theme song of the radio program '' Mayor of the Town''.

Barrymore had attended art school in New York and Paris and was a skillful graphic artist, creating etchings and drawings and was a member of the Society of American Graphic Artists, Society of American Etchers, now known as the Society of American Graphic Artists. For years, he maintained an artist's shop and studio attached to his home in Los Angeles. Some of his etchings were included in the ''Hundred Prints of the Year''.

He wrote a historical novel, ''Mr. Cantonwine: A Moral Tale'' (1953).

He was also a horticulturalist, growing roses on his Chatsworth Ranch.

Barrymore also composed music. His works ranged from solo piano pieces to large-scale orchestral works, such as "Tableau Russe," which was performed twice in ''Dr. Kildare's Wedding Day'' (1941) as Cornelia's Symphony, first on piano by Nils Asther's character and later by a full symphony orchestra. His piano compositions, "Scherzo Grotesque" and "Song Without Words", were published by G. Schirmer in 1945. Upon the death of his brother John in 1942, he composed a work "In Memoriam", which was performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra. He also composed the theme song of the radio program '' Mayor of the Town''.

Barrymore had attended art school in New York and Paris and was a skillful graphic artist, creating etchings and drawings and was a member of the Society of American Graphic Artists, Society of American Etchers, now known as the Society of American Graphic Artists. For years, he maintained an artist's shop and studio attached to his home in Los Angeles. Some of his etchings were included in the ''Hundred Prints of the Year''.

He wrote a historical novel, ''Mr. Cantonwine: A Moral Tale'' (1953).

He was also a horticulturalist, growing roses on his Chatsworth Ranch.

Death

Tributes

Barrymore received two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960—a List of actors with Hollywood Walk of Fame motion picture stars, motion pictures star and a radio star. The stars are located at 1724 Vine Street for motion pictures, and 1651 Vine Street for radio. He was also inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame, along with his siblings,Ethel

Ethel (also '' æthel'') is an Old English word meaning "noble", today often used as a feminine given name.

Etymology and historic usage

The word means ''æthel'' "noble".

It is frequently attested as the first element in Anglo-Saxon names, b ...

and John Barrymore, John.

Works

See also

* List of actors with Academy Award nominationsReferences

Bibliography

* *Basinger, Jeanine. ''Silent Stars.'' Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 2000. *Bergan, Ronald; Fuller, Graham; and Malcolm, David. ''Academy Award Winners.'' New York: Smithmark Publishers, 1994. *Block, Alex Ben and Wilson, Lucy Autrey. ''George Lucas's Blockbusting: A Decade-by-Decade Survey of Timeless Movies, Including Untold Secrets of Their Financial and Cultural Success.'' New York: itBooks, 2010. * *Coffin, Lesley L. ''Lew Ayres: Hollywood's Conscientious Objector.'' Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2012. *Culbertson, Judi and Randall, Tom. ''Permanent Californians: An Illustrated Guide to the Cemeteries of California.'' Chelsea, VT: Chelsea Green Pub. Co., 1989. *Donnelly, Paul. ''Fade to Black: A Book of Movie Obituaries.'' London: Omnibus, 2003. *Eames, John Douglas. ''The MGM Story: The Complete History of Fifty Roaring Years.'' New York: Crown Publishers, 1975. *Eyles, Allen. ''That Was Hollywood: The 1930s.'' London: Batsford, 1987. *Eyman, Scott. ''Lion of Hollywood: The Life and Legend of Louis B. Mayer.'' New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005. *Kennedy, Matthew. ''Marie Dressler: A Biography.'' Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2006. * *Marzano, Rudy. ''The Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1940s: How Robinson, MacPhail, Reiser, and Rickey Changed Baseball.'' Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2005. *Norden, Martin F. ''The Cinema of Isolation: A History of Physical Disability in the Movies.'' New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994. *Osborne, Robert A. ''Academy Awards Illustrated: A Complete History of Hollywood's Academy Awards in Words and Pictures.'' La Habra, CA: E.E. Schworck, 1969. * *Reid, John Howard. ''Hollywood Movie Musicals: Great, Good and Glamorous.'' Morrisville, NC: Lulu Press, 2006. *Schwartz, David. ''Magic of Thinking Big.'' New York: Simon and Schuster, 1987. *Silvers, Anita. "The Crooked Timber of Humanity: Disability, Ideology and the Aesthetic." In ''Disability/Postmodernity: Embodying Disability Theory.'' Mairian Corker and Tom Shakespeare, eds. New York: Continuum, 2002. *Wallace, David. ''Lost Hollywood.'' New York: St. Martin's Press, 2001. *Wayne, Jane Ellen. ''The Leading Men of MGM.'' New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2005. *Willian, Michael. ''The Essential It's a Wonderful Life: A Scene-by-Scene Guide to the Classic Film.'' Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2006.External links

Lionel Barrymore - allmovie

*

Photographs of Lionel Barrymore

*

Lionel Barrymore

photo gallery NYP Library

Lionel Barrymore and several other actors on Orson Welles Radio Almanac 1944

portrait by Burr McIntosh for Munseys Magazine

Lionel with brother John Barrymore, 1917

Lionel Barrymore - Aveleyman

{{DEFAULTSORT:Barrymore, Lionel 1878 births 1954 deaths 19th-century American male actors 20th-century American male actors American male composers American composers American male film actors American printmakers American male radio actors American male silent film actors American male stage actors American people of English descent American people of Irish descent Artists from Pennsylvania Barrymore family, Lionel Best Actor Academy Award winners Burials at Calvary Cemetery (Los Angeles) California Republicans Episcopal Academy alumni Film directors from Pennsylvania Male actors from Philadelphia Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer contract players Musicians from Philadelphia New York (state) Republicans People from Hempstead (village), New York Silent film directors Vaudeville performers Members of The Lambs Club