Les Bienveillantes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Kindly Ones'' (french: Les Bienveillantes) is a 2006

The title ''Les Bienveillantes'' (; ''The Kindly Ones'') refers to the trilogy of ancient Greek tragedies '' The Oresteia'' written by

The title ''Les Bienveillantes'' (; ''The Kindly Ones'') refers to the trilogy of ancient Greek tragedies '' The Oresteia'' written by

The Monster in the Mirror

''The New York Times''. Retrieved on 2010-09-24. The

Writer’s Unlikely Hero: A Deviant Nazi

''The New York Times'', October 9, 2006. When asked why he wrote such a book, Littell invokes a photo he discovered in 1989 of Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, a female Soviet partisan hanged by the Nazis in 1941. He adds that a bit later, in 1992, he watched the movie '' Shoah'' by Claude Lanzmann, which left an impression on him, especially the discussion by Raul Hilberg about the bureaucratic aspect of

« Allemande I & II »: Aue describes his service as an officer in one of the Einsatzgruppen extermination squads operating in

« Allemande I & II »: Aue describes his service as an officer in one of the Einsatzgruppen extermination squads operating in

Night and Cog

''The New Republic''. Retrieved on 2009-04-21.). Aue's group is attached to the 6th Army in Ukraine, where he witnesses the Lviv pogroms and participates in the enormous massacre at Babi Yar. He describes in detail the killing of «

«  « Menuet en rondeaux »: Aue is transferred to Heinrich Himmler's personal staff, where he is assigned an at-large supervisory role for the concentration camps. He struggles to improve the living conditions of those prisoners selected to work in the factories as slave laborers, in order to improve their productivity. Aue meets Nazi bureaucrats organizing the implementation of the

« Menuet en rondeaux »: Aue is transferred to Heinrich Himmler's personal staff, where he is assigned an at-large supervisory role for the concentration camps. He struggles to improve the living conditions of those prisoners selected to work in the factories as slave laborers, in order to improve their productivity. Aue meets Nazi bureaucrats organizing the implementation of the  « Gigue »: Accompanied by his friend Thomas, who has come to rescue him, and escorted by a violent band of fanatical and half-feral orphaned German children, Max makes his way through the Soviet-occupied territory and across the front line. Arriving in Berlin, Max, Thomas, and many of their colleagues prepare for escape in the chaos of the last days of the Third Reich; Thomas' own plan is to impersonate a French laborer. Aue meets and is personally decorated by Hitler in the

« Gigue »: Accompanied by his friend Thomas, who has come to rescue him, and escorted by a violent band of fanatical and half-feral orphaned German children, Max makes his way through the Soviet-occupied territory and across the front line. Arriving in Berlin, Max, Thomas, and many of their colleagues prepare for escape in the chaos of the last days of the Third Reich; Thomas' own plan is to impersonate a French laborer. Aue meets and is personally decorated by Hitler in the

Not for the faint-hearted

''The Spectator''. Retrieved on 2009-04-21. security and intelligence service of the SS; the book is written in the form of his memoirs. His mother was French (from

'The Kindly Ones,' by Jonathan Littell

''Los Angeles Times'', March 15, 2009. a Belgian fascist leader, Nazi collaborator and

Nazi-Sex Novel The Kindly Ones Polarizes Western Civilization

Vulture, 3/11/09.

*Una Aue / Frau Von Üxküll – Una Aue is Maximilien's twin sister. She is married to the aristocrat Berndt von Üxküll, and although she appears only briefly in person, she dominates Aue's imagination, particularly his

*Una Aue / Frau Von Üxküll – Una Aue is Maximilien's twin sister. She is married to the aristocrat Berndt von Üxküll, and although she appears only briefly in person, she dominates Aue's imagination, particularly his

The Monster in the Mirror

''The New York Times''. Retrieved on 2010-09-24. * * * * * * * * * Grossman, Lev (Mar. 19, 2009)

The Good Soldier

''Time''. Retrieved on 2009-04-25. * * * * Lasdun, James (February 28, 2009)

The exoticism of evil

''The Guardian''. Retrieved on 2009-08-18. * * * * * Schuessler, Jennifer (March 21, 2009)

''The New York Times''. Retrieved on 2010-09-24. * * * * * * * *

''Les Bienveillantes de Jonathan Littell''

Open Book Publishers. (2009) . * Golsan, Richard J., Suleiman, Susan R., ''Suite Française and Les Bienveillantes, Two Literary "Exceptions" : A Conversation'', ''Contemporary French and Francophone Studies'', vol. 12, no 3 (2008), pp. 321–330 * Golsan, Richard J., (editor), Watts, Philip (editor).,'' Literature and History: Around "Suite Française" and "Les Bienveillantes"'', '' Yale French Studies'', Number 121 (2012) * Hussey, Andrew (February 27, 2009)

''The Kindly Ones, By Jonathan Littell, translated by Charlotte Mandell''

''

''Guilty pleasures''

''

Lettres de Jonathan Littell à ses traducteurs

Retrieved on 2009-04-24 * Mandell, Charlotte, (March 14, 2009)

''Living Inside The Kindly Ones''

Beatrice.com. Retrieved on 2009-04-24 * Razinsky, Liran, ''History, Excess and Testimony in Jonathan Littell’s Les Bienveillantes'', ''French Forum'', vol. 33, no 3 (Autumn 2008), pp. 69–87 * Razinsky, Liran (editor), Barjonet, Aurélie (Editor), ''Writing the Holocaust Today: Critical Perspectives on Jonathan Littell's The Kindly Ones''. Rodopi. (2012) * Moyn, Samuel (March 4, 2009)

''A Nazi Zelig: Jonathan Littell's The Kindly Ones''

''

''Raising Hell''

''

Official blog

Information

on the ''

historical fiction

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other t ...

novel written in French by American-born author Jonathan Littell

Jonathan Littell (born October 10, 1967) is a writer living in Barcelona. He grew up in France and the United States and is a citizen of both countries. After acquiring his bachelor's degree he worked for a humanitarian organisation for nine year ...

. The book is narrated by its fictional protagonist Maximilien Aue, a former SS officer of French and German ancestry who was a Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

perpetrator and was present during several major events of World War II.

The 983-page book became a bestseller in France and was widely discussed in newspapers, magazines, academic journals, books and seminars. It was also awarded two of the most prestigious French literary awards, the Grand Prix du roman de l'Académie française

Le Grand Prix du Roman is a French literary award, created in 1914, and given each year by the Académie française. Along with the Prix Goncourt

The Prix Goncourt (french: Le prix Goncourt, , ''The Goncourt Prize'') is a prize in French litera ...

and the Prix Goncourt

The Prix Goncourt (french: Le prix Goncourt, , ''The Goncourt Prize'') is a prize in French literature, given by the académie Goncourt to the author of "the best and most imaginative prose work of the year". The prize carries a symbolic reward o ...

in 2006, and has been translated into several languages.

Background

The title ''Les Bienveillantes'' (; ''The Kindly Ones'') refers to the trilogy of ancient Greek tragedies '' The Oresteia'' written by

The title ''Les Bienveillantes'' (; ''The Kindly Ones'') refers to the trilogy of ancient Greek tragedies '' The Oresteia'' written by Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; grc-gre, Αἰσχύλος ; c. 525/524 – c. 456/455 BC) was an ancient Greek tragedian, and is often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Gree ...

. Gates, David (March 5, 2009)The Monster in the Mirror

''The New York Times''. Retrieved on 2010-09-24. The

Erinyes

The Erinyes ( ; sing. Erinys ; grc, Ἐρινύες, pl. of ), also known as the Furies, and the Eumenides, were female chthonic deities of vengeance in ancient Greek religion and mythology. A formulaic oath in the ''Iliad'' invokes the ...

or Furies were vengeful goddesses who tracked and tormented those who murdered a parent. In the plays, Orestes, who has killed his mother Clytemnestra to avenge his father Agamemnon

In Greek mythology, Agamemnon (; grc-gre, Ἀγαμέμνων ''Agamémnōn'') was a king of Mycenae who commanded the Greeks during the Trojan War. He was the son, or grandson, of King Atreus and Queen Aerope, the brother of Menelaus, the ...

, was pursued by these female goddesses. The goddess Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarded as the patron and protectress of v ...

intervenes, setting up a jury trial to judge the Furies' case against Orestes. Athena casts the deciding vote which acquits Orestes, then pleads with the Furies to accept the trial's verdict and to transform themselves into "most loved of gods, with me to show and share fair mercy, gratitude and grace as fair." The Furies accept and are renamed the Eumenides or Kindly Ones (in French ''Les Bienveillantes'').

Andrew Nurnberg, Littell's literary agent, said that a possible one-line description of the novel would be: "The intimate memoirs of an ex-Nazi mass murder

Mass murder is the act of murdering a number of people, typically simultaneously or over a relatively short period of time and in close geographic proximity. The United States Congress defines mass killings as the killings of three or more pe ...

er."Mark LanderWriter’s Unlikely Hero: A Deviant Nazi

''The New York Times'', October 9, 2006. When asked why he wrote such a book, Littell invokes a photo he discovered in 1989 of Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, a female Soviet partisan hanged by the Nazis in 1941. He adds that a bit later, in 1992, he watched the movie '' Shoah'' by Claude Lanzmann, which left an impression on him, especially the discussion by Raul Hilberg about the bureaucratic aspect of

genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the ...

.

In 2001, Littell decided to quit his job at Action Against Hunger

Action Against Hunger (french: Action Contre La Faim - ACF) is a global humanitarian organization which originated in France and is committed to ending world hunger. The organization helps malnourished children and provides communities with acc ...

and started research which lasted 18 months, during which he went to Germany, Ukraine, Russia and Poland, and read around 200 books, mainly about Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, the Eastern Front, the Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

, and the genocide process. In addition, the author studied the literature and film archives of World War II and the post-war trials. Littell worked on this novel for about five years. This book is his first novel written in French and his second novel after the science fiction themed ''Bad Voltage'' in 1989.

Littell said he wanted to focus on the thinking of an executioner and of origins of state murder, showing how we can take decisions that lead, or not, to a genocide. Littell claims he set out creating the character Max Aue by imagining what he would have done and how he would have behaved if he had been born into Nazi Germany. One childhood event that kept Littell interested in the question of being a killer was the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

. According to him, his childhood terror was that he would be drafted, sent to Vietnam "and made to kill women and children who hadn't done anything to me."

Whereas the influence of Greek tragedies is clear from the choice of title, the absent father, and the roles of incest

Incest ( ) is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by affinity ( marriage or stepfamily), ado ...

and parricide

Parricide refers to the deliberate killing of one’s own father and mother, spouse (husband or wife), children, and/or close relative. However, the term is sometimes used more generally to refer to the intentional killing of a near relative. It ...

, Littell makes it clear that he was influenced by more than the structure of ''The Oresteia''. He found that the idea of morality in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cu ...

is more relevant for making judgments about responsibility for the Holocaust than the Judeo-Christian

The term Judeo-Christian is used to group Christianity and Judaism together, either in reference to Christianity's derivation from Judaism, Christianity's borrowing of Jewish Scripture to constitute the "Old Testament" of the Christian Bible, o ...

approach, wherein the idea of sin can be blurred by the concepts such as intentional sin, unintentional sin, sinning by thought, or sinning by deed. For the Greeks it was the commission of the act itself upon which one is judged: Oedipus

Oedipus (, ; grc-gre, Οἰδίπους "swollen foot") was a mythical Greek king of Thebes. A tragic hero in Greek mythology, Oedipus accidentally fulfilled a prophecy that he would end up killing his father and marrying his mother, thereby ...

is guilty of patricide, even if he did not know that he was killing his father.

Plot

The book is a fictional autobiography, describing the life of Maximilien Aue, a former officer in the SS who, decades later, tells the story of a crucial part of his life when he was an active member of the security forces of theThird Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. Aue begins his narrative as a member of an Einsatzgruppe in 1941, before being sent to the doomed German forces locked in the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II where Nazi Germany and its allies unsuccessfully fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (later r ...

, which he survives. After a convalescence period in Berlin, and a visit to occupied France

The Military Administration in France (german: Militärverwaltung in Frankreich; french: Occupation de la France par l'Allemagne) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied z ...

, he is designated for an advisory role for the concentration camps, and visits the extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

s. He is ultimately present during the 1945 Battle of Berlin

The Battle of Berlin, designated as the Berlin Strategic Offensive Operation by the Soviet Union, and also known as the Fall of Berlin, was one of the last major offensives of the European theatre of World War II.

After the Vistula– ...

, the Nazi regime's last stand. By the end of the story, he flees Germany under a false French identity to start a new life in northern France. Throughout the account, Aue meets several famous Nazis, including Adolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

'' Heinrich Himmler Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

and '' Heinrich Himmler Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

. In the book, Aue accepts responsibility for his actions, but most of the time he feels more like an observer than a direct participant.

The book is divided into seven chapters, each named after a baroque dance, following the sequence of a Bach Suite. The narrative of each chapter is influenced by the rhythm of its associated dance.

« Toccata »: In this introduction, we are introduced to the narrator, and discover how he has ended up in France after the war. He is the director of a lace factory, has a wife, children, and grandchildren, though he has no real affection for his family and continues his homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to pe ...

encounters when he travels on business. He hints of an incest

Incest ( ) is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by affinity ( marriage or stepfamily), ado ...

uous love, which we learn later was for his twin sister. He explains that he has decided to write about his experiences during the war for his own benefit and not as an attempt to justify himself. He closes the introduction by saying, "I live, I do what can be done, it's the same for everyone, I am a man like other men, I am a man like you. I tell you I am just like you!"

« Allemande I & II »: Aue describes his service as an officer in one of the Einsatzgruppen extermination squads operating in

« Allemande I & II »: Aue describes his service as an officer in one of the Einsatzgruppen extermination squads operating in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

, as well as later in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

(a major theme is the racial classification, and thus fate, of the region's Mountain Jews

Mountain Jews or Caucasus Jews also known as Juhuro, Juvuro, Juhuri, Juwuri, Juhurim, Kavkazi Jews or Gorsky Jews ( he, יהודי קווקז ''Yehudey Kavkaz'' or ''Yehudey he-Harim''; russian: Горские евреи, translit=Gorskie Yevrei ...

Franklin, Ruth (April 1, 2009)Night and Cog

''The New Republic''. Retrieved on 2009-04-21.). Aue's group is attached to the 6th Army in Ukraine, where he witnesses the Lviv pogroms and participates in the enormous massacre at Babi Yar. He describes in detail the killing of

Soviet Jews

The history of the Jews in the Soviet Union is inextricably linked to much earlier expansionist policies of the Russian Empire conquering and ruling the eastern half of the European continent already before the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. "For ...

, Communists, alleged partisans and other victims of the "special operations". Although he seems to become increasingly indifferent to the atrocities he is witnessing and sometimes taking part in, he begins to experience daily bouts of vomiting and suffers a mental breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitt ...

. After taking sick leave, he is transferred to Otto Ohlendorf's Einsatzgruppe D

(, ; also 'task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the imple ...

only to encounter much hostility from his new SS colleagues, who openly spread rumours of his homosexuality. Aue is then charged with the assignment of proving to the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

that the Mountain Jews

Mountain Jews or Caucasus Jews also known as Juhuro, Juvuro, Juhuri, Juwuri, Juhurim, Kavkazi Jews or Gorsky Jews ( he, יהודי קווקז ''Yehudey Kavkaz'' or ''Yehudey he-Harim''; russian: Горские евреи, translit=Gorskie Yevrei ...

were historically Jewish rather than later converts to Judaism. After he fails in this task, due to political pressure from the beleaguered Army, his disappointed commanding officer

The commanding officer (CO) or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually given wide latitu ...

arranged that he be transferred to the doomed German forces at Stalingrad

Volgograd ( rus, Волгогра́д, a=ru-Volgograd.ogg, p=vəɫɡɐˈɡrat), formerly Tsaritsyn (russian: Цари́цын, Tsarítsyn, label=none; ) (1589–1925), and Stalingrad (russian: Сталингра́д, Stalingrád, label=none; ) ...

in late 1942.

«

« Courante

The ''courante'', ''corrente'', ''coranto'' and ''corant'' are some of the names given to a family of triple metre dances from the late Renaissance and the Baroque era. In a Baroque dance suite an Italian or French courante is typically paired ...

»: Aue thus takes part in the final phase of the struggle for Stalingrad. As with the massacres, he is mostly an observer, the narrator rather than the combatant. In the midst of the mayhem and starvation, he manages to have a discussion with a captured Soviet political commissar about the similarities between the Nazi and the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

world views, and once again is able to indicate his intellectual support for Nazi ideas. Aue gets shot in the head and seriously wounded, but is miraculously evacuated just before the German surrender in February 1943.

« Sarabande

The sarabande (from es, zarabanda) is a dance in triple metre, or the music written for such a dance.

History

The Sarabande evolved from a Spanish dance with Arab influences, danced by a lively double line of couples with castanets. A dance c ...

»: Convalescing in Berlin, Aue is awarded the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia es ...

1st Class, by the SS chief Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

himself, for his duty at Stalingrad. While still on sick leave, he decides to visit his mother and stepfather in Antibes

Antibes (, also , ; oc, label= Provençal, Antíbol) is a coastal city in the Alpes-Maritimes department of southeastern France, on the Côte d'Azur between Cannes and Nice.

The town of Juan-les-Pins is in the commune of Antibes and the Sop ...

, in Italian-occupied France

Italian-occupied France (; ) was an area of south-eastern France and Monaco occupied by the Kingdom of Italy between 1940 and 1943 in parallel to the German occupation of France. The occupation had two phases, divided by Case Anton in Novembe ...

. Apparently, while he is in a deep sleep, his mother and stepfather are brutally murdered. Max flees from the house without notifying anybody and returns to Berlin.

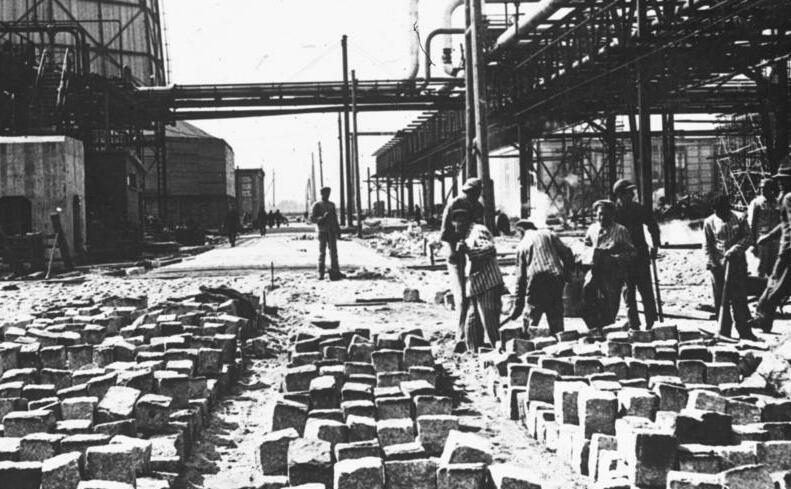

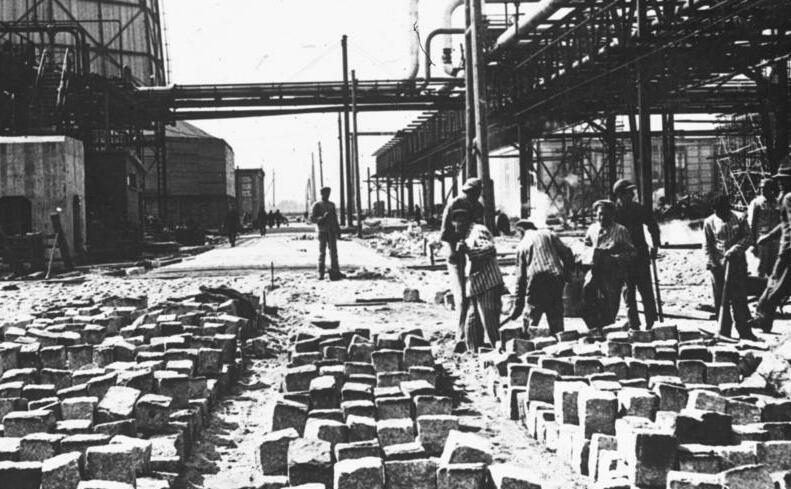

« Menuet en rondeaux »: Aue is transferred to Heinrich Himmler's personal staff, where he is assigned an at-large supervisory role for the concentration camps. He struggles to improve the living conditions of those prisoners selected to work in the factories as slave laborers, in order to improve their productivity. Aue meets Nazi bureaucrats organizing the implementation of the

« Menuet en rondeaux »: Aue is transferred to Heinrich Himmler's personal staff, where he is assigned an at-large supervisory role for the concentration camps. He struggles to improve the living conditions of those prisoners selected to work in the factories as slave laborers, in order to improve their productivity. Aue meets Nazi bureaucrats organizing the implementation of the Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

(i.e., Eichmann, Oswald Pohl

Oswald Ludwig Pohl (; 30 June 1892 – 7 June 1951) was a German SS functionary during the Nazi era. As the head of the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office and the head administrator of the Nazi concentration camps, he was a key figure in ...

, and Rudolf Höß) and is given a glimpse of extermination camps (i.e., Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

and Belzec); he also spends some time in Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population o ...

, just when preparations are being made for transporting Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz. Aue witnesses the tug-of-war between those who are concerned with war production (Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as the Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of World War II. A close ally of Adolf Hitler, h ...

) and those who are doggedly trying to implement the Final Solution. It is during this period that two police detectives from the Kripo

''Kriminalpolizei'' (, "criminal police") is the standard term for the criminal investigation agency within the police forces of Germany, Austria, and the German-speaking cantons of Switzerland. In Nazi Germany, the Kripo was the criminal poli ...

, who are investigating the murders of his mother and stepfather, begin to visit him regularly. Like the Furies, they hound and torment him with their questions, which indicate their suspicions about his role in the crime.

« Air »: Max visits his sister and brother-in-law's empty house in Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

. There, he engages in a veritable autoerotic orgy particularly fueled by fantasy images of his twin sister. The two police officers follow his trail to the house, but he manages to hide from them. However, Aue soon finds himself trapped when the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

rapidly invades and occupies Pomerania.

« Gigue »: Accompanied by his friend Thomas, who has come to rescue him, and escorted by a violent band of fanatical and half-feral orphaned German children, Max makes his way through the Soviet-occupied territory and across the front line. Arriving in Berlin, Max, Thomas, and many of their colleagues prepare for escape in the chaos of the last days of the Third Reich; Thomas' own plan is to impersonate a French laborer. Aue meets and is personally decorated by Hitler in the

« Gigue »: Accompanied by his friend Thomas, who has come to rescue him, and escorted by a violent band of fanatical and half-feral orphaned German children, Max makes his way through the Soviet-occupied territory and across the front line. Arriving in Berlin, Max, Thomas, and many of their colleagues prepare for escape in the chaos of the last days of the Third Reich; Thomas' own plan is to impersonate a French laborer. Aue meets and is personally decorated by Hitler in the Führerbunker

The ''Führerbunker'' () was an air raid shelter located near the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, Germany. It was part of a subterranean bunker complex constructed in two phases in 1936 and 1944. It was the last of the Führer Headquarters ...

. During the decoration ceremony, Aue inexplicably bites the Führer

( ; , spelled or ''Fuhrer'' when the umlaut is not available) is a German word meaning "leader" or " guide". As a political title, it is strongly associated with the Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler.

Nazi Germany cultivated the ("leader princip ...

's nose and is immediately arrested. When he is transported to his execution, the car is hit by an artillery shell, enabling him to escape. Aue flees through the Berlin U-Bahn

The Berlin U-Bahn (; short for , "underground railway") is a rapid transit system in Berlin, the capital and largest city of Germany, and a major part of the city's public transport system. Together with the S-Bahn, a network of suburban tra ...

subway tunnels, where he encounters his police pursuers again. Though their case has been repeatedly thrown out of court, the two detectives, unwilling to accept defeat, decided to track Aue down and execute him extrajudicially. Barely escaping when the Soviets storm the tunnels and kill one of the policemen, Aue wanders aimlessly in the ruined streets of war-torn Berlin before deciding to make a break for it. Making his way through the wasteland of the destroyed Berlin Zoo

The Berlin Zoological Garden (german: link=no, Zoologischer Garten Berlin) is the oldest surviving and best-known zoo in Germany. Opened in 1844, it covers and is located in Berlin's Tiergarten. With about 1,380 different species and over 20,2 ...

, he is yet again faced by the surviving policeman. Thomas shows up to kill the policeman, only to himself be killed by Aue, who steals from him the papers and uniform of a French STO conscripted worker.

The readers know from the beginning of the book that Aue's perfect mastery of the French language will allow him to slip away back to France with a new identity as a returning Frenchman. In the last paragraph of the novel, the narrator, after he ruthlessly killed his friend and protector, suddenly finds himself "alone with time and sadness": "The Kindly Ones were on to me." But in the end, all is not explicitly laid out for the reader; for Littell, in the words of one reviewer, "excels in the unsaid."

Characters

Maximilien Aue

Maximilien Aue is a former officer of the SD,Marham, Patrick (March 4, 2009)Not for the faint-hearted

''The Spectator''. Retrieved on 2009-04-21. security and intelligence service of the SS; the book is written in the form of his memoirs. His mother was French (from

Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

), while his father, who left his mother and disappeared from their life in 1921, was German. Aue's mother remarried a Frenchman, Aristide Moreau, which Maximilien highly disapproved of. After a childhood in Germany and an adolescence in France, where he attends Sciences-Po

, motto_lang = fr

, mottoeng = Roots of the Future

, type = Public research university''Grande école''

, established =

, founder = Émile Boutmy

, accreditation ...

, he later returns to Germany to study at the University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative ...

and the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. It is also during this period that he joins the SS, eventually rising to the rank of Obersturmbannführer. Aue is a cultured, highly educated, classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical music, as the term "classical music" al ...

-loving intellectual. He speaks many languages fluently – German, French, Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

– and holds a doctorate in law. Despite his French heritage and upbringing, he is, like his father, an ardent German nationalist. Even after the war, he is unrepentant of the crimes he committed in the name of National Socialism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Naz ...

, "believing that it was my duty and that it had to be done, disagreeable or unpleasant as it may have been." He is extremely attracted to his twin sister Una, which led to an incest

Incest ( ) is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by affinity ( marriage or stepfamily), ado ...

uous relationship with her when they were children, but ended when they entered puberty

Puberty is the process of physical changes through which a child's body matures into an adult body capable of sexual reproduction. It is initiated by hormonal signals from the brain to the gonads: the ovaries in a girl, the testes in a ...

. Refusing to truly love any woman other than Una, he resorts to having sexual affairs with only men, while continuing to fantasize about his sister.

The character appears to be in part inspired by Léon Degrelle,Laila Lalami'The Kindly Ones,' by Jonathan Littell

''Los Angeles Times'', March 15, 2009. a Belgian fascist leader, Nazi collaborator and

Waffen-SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscripts from both occup ...

officer who was the subject of Littell's short book '' Le sec et l’humide: Une brève incursion en territoire fasciste'' ("The dry and wet: A brief foray into fascist territory"). A number of critics compared Aue's omnipresence in the world of the novel to that of Winston Groom

Winston Francis Groom Jr. (March 23, 1943 – September 17, 2020) was an American novelist and non-fiction writer. He is best known for his novel '' Forrest Gump'' (1986), which became a cultural phenomenon after being adapted as a 1994 film o ...

's character Forrest Gump

''Forrest Gump'' is a 1994 American comedy-drama film directed by Robert Zemeckis and written by Eric Roth. It is based on the 1986 novel of the same name by Winston Groom and stars Tom Hanks, Robin Wright, Gary Sinise, Mykelti Williamson ...

.Boris KachkaNazi-Sex Novel The Kindly Ones Polarizes Western Civilization

Vulture, 3/11/09.

Aue's family

sexual fantasies

A sexual fantasy or erotic fantasy is a mental image or pattern of thought that stirs a person's sexuality and can create or enhance sexual arousal. A sexual fantasy can be created by the person's imagination or memory, and may be triggered aut ...

and hallucinations. She lived with her husband on his estate in Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

, but apparently moved to Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

with him towards the end of the war. Like her husband, she is critical of Germany's National Socialist regime; this, along with Max's hatred of their mother and stepfather, and his attraction to her, led to her being estranged from Aue following the war.

*Berndt Von Üxküll – Von Üxküll is a paraplegic

Paraplegia, or paraparesis, is an impairment in motor or sensory function of the lower extremities. The word comes from Ionic Greek ()

"half-stricken". It is usually caused by spinal cord injury or a congenital condition that affects the neura ...

junker from Pomerania and a composer who is married to Una. A World War I veteran, he fought alongside Aue's father, whom he describes as a sadist, in the Freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, rega ...

. Despite essentially agreeing with their nationalist and antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

ideology, he distances himself from the Nazis. His name is possibly a reference to Nikolaus Graf von Üxküll-Gyllenband, an anti-Nazi resistant and uncle of Claus von Stauffenberg

Colonel Claus Philipp Maria Justinian Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg (; 15 November 1907 – 21 July 1944) was a German army officer best known for his failed attempt on 20 July 1944 to assassinate Adolf Hitler at the Wolf's Lair.

Despite ...

, a central figure in the failed plot to assassinate Hitler.

*Héloïse Aue (Héloïse Moreau) – Max's mother, who, believing her first husband to be dead, remarried Aristide Moreau. Max does not accept that his father is dead and never forgives his mother for remarrying. Héloïse also disapproves of Max's joining the Nazis, which further strains their relationship.

*Aristide Moreau – Max's stepfather, who is apparently connected to the French Resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

. Moreau is also the name of the "hero" from Gustave Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert ( , , ; 12 December 1821 – 8 May 1880) was a French novelist. Highly influential, he has been considered the leading exponent of literary realism in his country. According to the literary theorist Kornelije Kvas, "in Flauber ...

's ''Sentimental Education

''Sentimental Education'' (French: ''L'Éducation sentimentale'', 1869) is a novel by Gustave Flaubert. Considered one of the most influential novels of the 19th century, it was praised by contemporaries such as George Sand and Émile Zola, bu ...

'', a book that Aue reads later in the novel. ''Aristide'' is reminiscent in French of ''Atrides'', the name given to the descendants of Atreus

In Greek mythology, Atreus ( , ; from ἀ-, "no" and τρέω, "tremble", "fearless", gr, Ἀτρεύς ) was a king of Mycenae in the Peloponnese, the son of Pelops and Hippodamia, and the father of Agamemnon and Menelaus. Collectively ...

, among whom figure Agamemnon, Orestes and Electra.

*The twins, Tristan and Orlando – Mysterious twin children who live with the Moreaus, but are most likely the offspring of the incestuous relationship between Aue and his sister. The epic poem ''Orlando Furioso

''Orlando furioso'' (; ''The Frenzy of Orlando'', more loosely ''Raging Roland'') is an Italian epic poem by Ludovico Ariosto which has exerted a wide influence on later culture. The earliest version appeared in 1516, although the poem was ...

'' is marked by the themes of love and madness, while the legend of ''Tristan and Iseult

Tristan and Iseult, also known as Tristan and Isolde and other names, is a medieval chivalric romance told in numerous variations since the 12th century. Based on a Celtic legend and possibly other sources, the tale is a tragedy about the illic ...

'' tells the story of an impossible love, two themes that can be found in ''The Kindly Ones''.

Other fictional main characters

*Thomas Hauser – Thomas is Max's closest friend and the only person who appears in one capacity or another wherever he is posted. A highly educated, multilingual SS officer like Max, he is Aue's main source of information about bureaucratic Nazi politics. He helps Max in a number of ways, both in advancing his career as well as rescuing him from his sister's house in Pomerania. He saves Max's life at Stalingrad. *Hélène Anders née Winnefeld – A young widow whom Aue meets through Thomas, while working in Berlin. When Max becomes seriously ill, she voluntarily comes to his apartment and nurses him back to health. While she is attracted to him, as he initially expresses interest in her, due to his feelings for his sister, as well as his homosexual tendencies, he coldly turns her down and away. She leaves Berlin for her parents' house and writes, asking if he intends to marry her. She does not appear again in the novel. In theGreek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities o ...

, Helen

Helen may refer to:

People

* Helen of Troy, in Greek mythology, the most beautiful woman in the world

* Helen (actress) (born 1938), Indian actress

* Helen (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

Places

* Helen, ...

marries Menelaus

In Greek mythology, Menelaus (; grc-gre, Μενέλαος , 'wrath of the people', ) was a king of Mycenaean (pre- Dorian) Sparta. According to the ''Iliad'', Menelaus was a central figure in the Trojan War, leading the Spartan contingent of ...

, brother of Agamemnon.

*Dr. Mandelbrod – The mysterious Dr. Mandelbrod plays an important role behind the scenes as Aue's protector and promoter with high-level NSDAP

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

connections, particularly with Himmler. He was an admirer of Max's father and grandfather. At the end of the book he is seen packing his bags to join the enemy, offering his services to the Soviet Union.

*Kriminalkommissars Weser and Clemens – A pair of Kriminalpolizei

''Kriminalpolizei'' (, "criminal police") is the standard term for the criminal investigation agency within the police forces of Germany, Austria, and the German-speaking cantons of Switzerland. In Nazi Germany, the Kripo was the criminal polic ...

detectives who are in charge of the investigation into the murders of Aue's mother and her husband. They question and pursue Aue throughout the war, as if he were a prime murder suspect, despite the cases being repeatedly thrown out. They play the role of the Erinyes in the novel.

*Dr. Hohenegg – Aue's friend, a doctor interested in nutrition as well as the condition of soldiers and prisoners in concentration camps. Aue meets him in Ukraine during the German offensive against the Soviet Union. They both take part in battle of Stalingrad and successfully escape before the German surrender. They reunite in Berlin, with Hohenegg revealing to Max how he saved his life by convincing doctors at Stalingrad to operate on him and transport him back to Germany, rather than leaving him for dead. He is depicted at different points in the book.

*Dr. Voss – A lieutenant sent in to the Eastern Front (where he befriends Aue) by the Abwehr

The ''Abwehr'' ( German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', but the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context; ) was the German military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the '' Wehrmacht'' from 1920 to 1944. ...

and actually a university investigator and specialist in Indo-Germanic, Indo-Iranian and Caucasian languages.

Historical characters

Littell also includes many historical figures that Max encounters throughout the novel. Amongst them are: *Top-ranking Nazis: Werner Best,Martin Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann (17 June 1900 – 2 May 1945) was a German Nazi Party official and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. He gained immense power by using his position as Adolf Hitler's private secretary to control the flow of information ...

, Hermann Fegelein

Hans Otto Georg Hermann Fegelein (30 October 1906 – 28 April 1945) was a high-ranking commander in the Waffen-SS of Nazi Germany. He was a member of Adolf Hitler's entourage and brother-in-law to Eva Braun through his marriage to her si ...

, Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank (23 May 1900 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and lawyer who served as head of the General Government in Nazi-occupied Poland during the Second World War.

Frank was an early member of the German Workers' Par ...

, Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( ; ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust.

He was chief of the Reich Security Main Office (inclu ...

, Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

, Ernst Kaltenbrunner

Ernst Kaltenbrunner (4 October 190316 October 1946) was a high-ranking Austrian SS official during the Nazi era and a major perpetrator of the Holocaust. After the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich in 1942, and a brief period under Heinrich Hi ...

, Heinrich Müller Heinrich Müller may refer to:

* Heinrich Müller (cyclist) (born 1926), Swiss cyclist

* Heinrich Müller (footballer, born 1888) (1888–1957), Swiss football player and manager

* Heinrich Müller (footballer, born 1909) (1909–2000), Austrian ...

, Arthur Nebe, Walter Schellenberg and Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as the Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of World War II. A close ally of Adolf Hitler, h ...

.

*Other Nazis: Richard Baer

Richard Baer (9 September 1911 – 17 June 1963) was a German SS officer who, among other assignments, was the commandant of Auschwitz I concentration camp from May 1944 to January 1945, and right after, from February to April 1945, commandan ...

, Walter Bierkamp, Paul Blobel, Rudolf Brandt

Rudolf Hermann Brandt (2 June 1909 – 2 June 1948) was a German SS officer from 1933–45 and a civil servant. A lawyer by profession, Brandt was the Personal Administrative Officer to ''Reichsführer-SS'' (''Persönlicher Referent vom Reichsf ...

, Adolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

'' Otto Förschner Otto Förschner (4 November 1902 – 28 May 1946) was a German SS commander and a Nazi concentration camp official. He served as commandant of the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp and the Kaufering concentration camp in the Dachau camp syst ...

, Odilo Globocnik, Rudolf Höß, '' Otto Förschner Otto Förschner (4 November 1902 – 28 May 1946) was a German SS commander and a Nazi concentration camp official. He served as commandant of the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp and the Kaufering concentration camp in the Dachau camp syst ...

Hans Kammler

Hans Kammler (26 August 1901 – 1945 ssumed was an SS-Obergruppenführer responsible for Nazi civil engineering projects and its top secret weapons programmes. He oversaw the construction of various Nazi concentration camps before being put ...

, Arthur Liebehenschel, Josef Mengele

, allegiance =

, branch = Schutzstaffel

, serviceyears = 1938–1945

, rank = '' SS''-'' Hauptsturmführer'' (Captain)

, servicenumber =

, battles =

, unit =

, awards =

, commands =

, ...

, Theodor Oberländer

Theodor Oberländer (1 May 1905 – 4 May 1998) was an Ostforschung scientist and German Nazi official and politician, who after the Second World War served as Federal Minister for Displaced Persons, Refugees and Victims of War in West Germany ...

, Otto Ohlendorf

Otto Ohlendorf (; 4 February 1907 – 7 June 1951) was a German SS functionary and Holocaust perpetrator during the Nazi era. An economist by education, he was head of the (SD) Inland, responsible for intelligence and security within Germ ...

, Otto Rasch

Emil Otto Rasch (7 December 1891 – 1 November 1948) was a high-ranking German Nazi official and Holocaust perpetrator, who commanded Einsatzgruppe C in northern and central Ukraine until October 1941. After World War II, Rasch was indicted for ...

, Walther von Reichenau, Franz Six, Eduard Wirths and Dieter Wisliceny

Dieter Wisliceny (13 January 1911 – 4 May 1948) was a member of the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) and one of the deputies of Adolf Eichmann, helping to organise and coordinate the wide scale deportations of the Jews across Europe during the Holocaust.

...

.

*French collaborators

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its t ...

: Robert Brasillach

Robert Brasillach (; 31 March 1909 – 6 February 1945) was a French author and journalist. Brasillach was the editor of ''Je suis partout'', a nationalist newspaper which advocated fascist movements and supported Jacques Doriot. After the liberat ...

and Lucien Rebatet

Lucien Rebatet (15 November 1903 – 24 August 1972) was a French writer, journalist, and intellectual. He is known as an exponent of fascism and virulent antisemite but also as the author of '' Les Deux étendards'', regarded by some as one of ...

.

Contemporary writers that have no interaction with Aue are Ernst Jünger, Charles Maurras

Charles-Marie-Photius Maurras (; ; 20 April 1868 – 16 November 1952) was a French author, politician, poet, and critic. He was an organizer and principal philosopher of ''Action Française'', a political movement that is monarchist, anti-parl ...

, Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Paul Carell

Paul Carell was the post-war pen name of Paul Karl Schmidt (2 November 1911 – 20 June 1997) who was a writer and German propagandist. During the Nazi era, Schmidt served as the chief press spokesman for Joachim von Ribbentrop's Foreign Ministry. ...

. Historians cited by Aue are Alan Bullock

Alan Louis Charles Bullock, Baron Bullock, (13 December 1914 – 2 February 2004) was a British historian. He is best known for his book '' Hitler: A Study in Tyranny'' (1952), the first comprehensive biography of Adolf Hitler, which influence ...

, Raul Hilberg and Hugh Trevor-Roper.

Reception

The original French edition

Besides winning two of the most prestigious literary prizes in France (Grand Prix du roman de l'Académie française

Le Grand Prix du Roman is a French literary award, created in 1914, and given each year by the Académie française. Along with the Prix Goncourt

The Prix Goncourt (french: Le prix Goncourt, , ''The Goncourt Prize'') is a prize in French litera ...

and Prix Goncourt

The Prix Goncourt (french: Le prix Goncourt, , ''The Goncourt Prize'') is a prize in French literature, given by the académie Goncourt to the author of "the best and most imaginative prose work of the year". The prize carries a symbolic reward o ...

), ''Les Bienveillantes'' was generally very favourably reviewed in the French literary press. ''Le Figaro

''Le Figaro'' () is a French daily morning newspaper founded in 1826. It is headquartered on Boulevard Haussmann in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. The oldest national newspaper in France, ''Le Figaro'' is one of three French newspapers of r ...

'' proclaimed Littell "man of the year". The editor of the ''Nouvel Observateur

(), previously known as (1964–2014), is a weekly French news magazine. Based in the 2nd arrondissement of Paris, it is the most prominent French general information magazine in terms of audience and circulation. Its current editor is Cécil ...

''s literary section called it "a great book" and the weekly ''Le Point

''Le Point'' () is a French weekly political and news magazine published in Paris.

History and profile

''Le Point'' was founded in September 1972 by a group of journalists who had, one year earlier, left the editorial team of '' L'Express'', w ...

'' stated that the novel has "exploded onto the dreary plain of the literary autumn like a meteor." Even though French filmmaker and professor Claude Lanzmann had mixed feelings about the book, he said: "I am familiar with his subject, and above all I was astounded by the absolute accuracy of the novel. Everything is correct." French historian Pierre Nora

Pierre Nora (born 17 November 1931) is a French historian elected to the Académie française on 7 June 2001. He is known for his work on French identity and memory. His name is associated with the study of new history. He is the brother of t ...

called it "an extraordinary literary and historical phenomenon." The book has been compared to ''War and Peace

''War and Peace'' (russian: Война и мир, translit=Voyna i mir; pre-reform Russian: ; ) is a literary work by the Russian author Leo Tolstoy that mixes fictional narrative with chapters on history and philosophy. It was first published ...

'' for its similar scope and ambition.

''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''Th ...

''s literary reviewer, Anita Brookner, based on her reading of the novel in the original French, described the book as a "masterly novel ... diabolically (and I use the word advisedly) clever. It is also impressive, not merely as an act of impersonation but perhaps above all for the fiendish diligence with which it is carried out ... presuppose(s) formidable research on the part of the author, who is American, educated in France and writing fluent, idiomatic and purposeful French. This tour de force, which not everyone will welcome, outclasses all other fictions and will continue to do so for some time to come. No summary can do it justice." ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...

''s Paris correspondent, Jason Burke, praised the book as an "extraordinary Holocaust novel asks what it is that turns normal people into mass killers," adding that "notwithstanding the controversial subject matter, this is an extraordinarily powerful novel."

Initially, Littell thought that his book would sell around three to five thousand copies. Éditions Gallimard

Éditions Gallimard (), formerly Éditions de la Nouvelle Revue Française (1911–1919) and Librairie Gallimard (1919–1961), is one of the leading French book publishers. In 2003 it and its subsidiaries published 1,418 titles.

Founded by Ga ...

, his publishing house, was more optimistic and decided to print 12,000 copies. Word of mouth and the enthusiastic reviews soon catapulted sales to such an extent that Gallimard had to stop publishing the latest ''Harry Potter

''Harry Potter'' is a series of seven fantasy novels written by British author J. K. Rowling. The novels chronicle the lives of a young wizard, Harry Potter, and his friends Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley, all of whom are students at ...

'' novel in order to meet the demand for ''The Kindly Ones'', which ended up selling more than 700,000 copies in France by the end of 2007. Littell was finally given French citizenship

French nationality law is historically based on the principles of ''jus soli'' (Latin for "right of soil") and ''jus sanguinis'', according to Ernest Renan's definition, in opposition to the German definition of nationality, ''jus sanguinis'' ( ...

.

Other language editions

After the book was translated into German, there was widespread debate in Germany, during which Littell was accused of being "a pornographer of violence." Some criticised it from a historical perspective, calling the novel a "strange, monstrous book" and alleging it is "full of errors and anachronisms over wartime German culture." Upon its publication inEnglish

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

in early 2009, ''The Kindly Ones'' received mixed reviews. ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' is an American magazine of commentary on politics, contemporary culture, and the arts. Founded in 1914 by several leaders of the progressive movement, it attempted to find a balance between "a liberalism centered in hu ...

''s literary critic Ruth Franklin called it "one of the most repugnant books I have ever read ..if getting under the skin of a murderer were sufficient to produce a masterpiece, then Thomas Harris would be Tolstoy." Michiko Kakutani, the principal book critic of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', called the novel " llfully sensationalistic and deliberately repellent" and went on to question the "perversity" of the French literary establishment for praising the novel. In a reply to Kakutani, writer and novelist Michael Korda wrote, "You want to read about Hell

In religion and folklore, hell is a location in the afterlife in which evil souls are subjected to punitive suffering, most often through torture, as eternal punishment after death. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hell ...

, here it is. If you don’t have the strength to read it, tough shit. It’s a dreadful, compelling, brilliantly researched, and imagined masterpiece, a terrifying literary achievement, and perhaps the first work of fiction to come out of the Holocaust that places us in its very heart, and keeps us there." Writing for ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and event (philosophy), events that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various me ...

'', American writer and journalist Lev Grossman compared it to Roberto Bolaño

Roberto Bolaño Ávalos (; 28 April 1953 – 15 July 2003) was a Chilean novelist, short-story writer, poet and essayist. In 1999, Bolaño won the Rómulo Gallegos Prize for his novel ''Los detectives salvajes'' (''The Savage Detectives'' ...

's ''2666

''2666'' is the last novel by Roberto Bolaño. It was released in 2004, a year after Bolaño's death. It is over 1100 pages long in Spanish, and almost 900 in its English translation, it is divided into five parts. An English-language translat ...

'', similar in "their seriousness of purpose, their wild overestimation of the reader's attention span and their interest in physical violence that makes '' Saw'' look like ''Dora the Explorer

''Dora the Explorer'' is an American children's animated television series and multimedia franchise created by Chris Gifford, Valerie Walsh Valdes and Eric Weiner that premiered on Nickelodeon on August 14, 2000, went on hiatus on June 5, 20 ...

''," but added that while far from perfect, ''The Kindly Ones'' "is unmistakably the work of a profoundly gifted writer, if not an especially disciplined one." In her review for ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the ...

'', novelist and essayist Laila Lalami wrote: "Jonathan Littell has undertaken a very ambitious project in ''The Kindly Ones'', and I think his boldness deserves to be commended. In the end, however, his highly problematic characterization and awkward handling of point of view make this book far more successful as a dramatized historical document than as a novel." British historian Antony Beevor, author of ''Stalingrad'' and ''The Fall of Berlin 1945'', reviewing ''The Kindly Ones'' in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'', called it "a great work of literary fiction, to which readers and scholars will turn for decades to come," and listed it as one of the top five books of World War II fiction.

Jonathan Derbyshire, culture editor of the ''New Statesman

The ''New Statesman'' is a British political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney and Beatrice Webb and other leading members ...

'' called it "a remarkable novel" and its protagonist "a convincing witness to the defining moral catastrophe of the 20th century." Tim Martin of ''The Telegraph

''The Telegraph'', ''Daily Telegraph'', ''Sunday Telegraph'' and other variant names are popular names for newspapers. Newspapers with these titles include:

Australia

* ''The Telegraph'' (Adelaide), a newspaper in Adelaide, South Australia, publ ...

'' praised the novel for not being just another story about banality of evil

''Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil'' is a 1963 book by political thinker Hannah Arendt. Arendt, a Jew who fled Germany during Adolf Hitler's rise to power, reported on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the major organizers ...

: "it is a magnificently artificial project in character construction, a highly literary and provocative attempt to create a character various enough to match the many discontinuous realities of the apocalyptic Nazi world-view. The result is a sprawling, daring, loose-ended monster of a book, one that justifies its towering subject matter by its persistent and troubling refusal to offer easy answers and to make satisfying sense." Writing for ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

'', British author James Lasdun

James Lasdun (born 1958) is an English novelist and poet.

Life and career

Lasdun was born in London, the son of Susan (Bendit) and British architect Sir Denys Lasdun. Lasdun has written four novels, including , a New York Times Notable Book, and ...

criticized the novel for "some large flaws" such as its main character, "a ghoul belonging more to the fictional universe of, say, Bret Easton Ellis

Bret Easton Ellis (born March 7, 1964) is an American author, screenwriter, short-story writer, and director. Ellis was first regarded as one of the so-called literary Brat Pack and is a self-proclaimed satirist whose trademark technique, as a ...

's ''American Psycho

''American Psycho'' is a novel by Bret Easton Ellis, published in 1991. The story is told in the first person by Patrick Bateman, a serial killer and Manhattan investment banker. Alison Kelly of ''The Observer'' notes that while "some countr ...

''", and provocative use of anachronisms, but called it a "monumental inquiry into evil. To say that it falls short of Melville's visionary originality (and lacks, also, the breadth and vitality of Tolstoy, despite the claims of some reviewers) is hardly a criticism. It's a rare book that even invites such comparisons, and for all its faults, for all its problematic use of history, ''The Kindly Ones'' does just that." In ''The Spectator'', British journalist and biographer Patrick Marnham wrote: "Dr Aue cannot be brought to trial because he does not exist; on the other hand, he can give us something even more valuable than vengeance, something that no real war criminal can manage, and that is total honesty." Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

's English studies

English studies (usually called simply English) is an academic discipline taught in primary, secondary, and post-secondary education in English-speaking countries; it is not to be confused with English taught as a foreign language, which ...

' Professor Leland de la Durantaye wrote that ''The Kindly Ones'' "is indeed about cruelty and evil in the way that morality plays are, but it is also about evil in ''history'', the weaving together of hundreds of objectives, millions of people, into an ensemble so vast, diverse, and ever-changing that even a well-placed and sharp-sighted observer cannot fully grasp it."

Sales in the United States were considered extremely low. The book was bought by HarperCollins

HarperCollins Publishers LLC is one of the Big Five English-language publishing companies, alongside Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, Hachette, and Macmillan. The company is headquartered in New York City and is a subsidiary of News C ...

for a rumored $1 million, and the first printing consisted of 150,000 copies. According to Nielsen BookScan

BookScan is a data provider for the book publishing industry that compiles point of sale data for book sales, owned by The NPD Group in the United States and the Nielsen Company in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, India, So ...

– which captures around 70 percent of total sales – by the end of July 2009 only 17,000 copies had been sold.

Adaptations

The novel was adapted into opera by Catalan composerHèctor Parra

Hèctor Parra i Esteve (born 17 April 1976) is a Spanish composer. Since 2002 he lives in Paris.

Life

Born in Barcelona, Parra completed his studies with Carles Guivoart, David Padrós and Maria Jesús Crespo at the Municipal Conservatory o ...

with libretto by Händl Klaus, directed by Calixto Bieito. The work was commissioned by Opera Vlaanderen, premiered on April 24, 2019 in Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

.

Notes

References

* * Gates, David (March 5, 2009)The Monster in the Mirror

''The New York Times''. Retrieved on 2010-09-24. * * * * * * * * * Grossman, Lev (Mar. 19, 2009)

The Good Soldier

''Time''. Retrieved on 2009-04-25. * * * * Lasdun, James (February 28, 2009)

The exoticism of evil

''The Guardian''. Retrieved on 2009-08-18. * * * * * Schuessler, Jennifer (March 21, 2009)

''The New York Times''. Retrieved on 2010-09-24. * * * * * * * *

Further reading

* Clément, Murielle Lucie (editor)''Les Bienveillantes de Jonathan Littell''

Open Book Publishers. (2009) . * Golsan, Richard J., Suleiman, Susan R., ''Suite Française and Les Bienveillantes, Two Literary "Exceptions" : A Conversation'', ''Contemporary French and Francophone Studies'', vol. 12, no 3 (2008), pp. 321–330 * Golsan, Richard J., (editor), Watts, Philip (editor).,'' Literature and History: Around "Suite Française" and "Les Bienveillantes"'', '' Yale French Studies'', Number 121 (2012) * Hussey, Andrew (February 27, 2009)

''The Kindly Ones, By Jonathan Littell, translated by Charlotte Mandell''

''

The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publish ...

''. Retrieved on 2009-04-21.

* Hussey, Andrew (December 11, 2006)''Guilty pleasures''

''

New Statesman

The ''New Statesman'' is a British political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney and Beatrice Webb and other leading members ...

''. Retrieved on 2010-09-24.

* Lemonier, Marc, ''Les Bienveillantes décryptées''. Le Pré aux Clercs. (2007) .

* Littell, Jonathan, (November 13, 2006)Lettres de Jonathan Littell à ses traducteurs

Retrieved on 2009-04-24 * Mandell, Charlotte, (March 14, 2009)

''Living Inside The Kindly Ones''

Beatrice.com. Retrieved on 2009-04-24 * Razinsky, Liran, ''History, Excess and Testimony in Jonathan Littell’s Les Bienveillantes'', ''French Forum'', vol. 33, no 3 (Autumn 2008), pp. 69–87 * Razinsky, Liran (editor), Barjonet, Aurélie (Editor), ''Writing the Holocaust Today: Critical Perspectives on Jonathan Littell's The Kindly Ones''. Rodopi. (2012) * Moyn, Samuel (March 4, 2009)

''A Nazi Zelig: Jonathan Littell's The Kindly Ones''

''

The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper t ...

''. Retrieved on 2009-04-21.

* Suleiman, Susan Rubin, ''When the Perpetrator Becomes a Reliable Witness of the Holocaust : On Jonathan Littell's Les Bienveillantes'', '' New German Critique'', vol. 36, no 1 (2009), pp. 1–19

* Suleiman, Susan Rubin (March 15, 2009)''Raising Hell''

''

The Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe'' is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes, and has a total circulation of close to 300,000 print and digital subscribers. ''The Boston Glob ...

''. Retrieved on 2011-06-20.

* Theweleit, Klaus, ''On the German Reaction to Jonathan Littell's Les Bienveillantes'', '' New German Critique'', vol. 36, no 1 (2009), pp. 21–34

External links

Official blog

Information

on the ''

Frankfurter Allgemeine

The ''Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung'' (; ''FAZ''; "''Frankfurt General Newspaper''") is a centre-right conservative-liberal and liberal-conservativeHans Magnus Enzensberger: Alter Wein in neuen Schläuchen' (in German). ''Deutschland Radio'', ...

'' website

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kindly Ones, The

2006 French novels

French historical novels

Novels about Nazi Germany

Novels about the Holocaust

Prix Goncourt winning works

Novels set during World War II

HarperCollins books

Éditions Gallimard books

Cultural depictions of Adolf Hitler

Cultural depictions of Heinrich Himmler

Cultural depictions of Josef Mengele