Leoš Janáček on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Leoš Janáček (, baptised Leo Eugen Janáček; 3 July 1854 – 12 August 1928) was a Czech composer, musical theorist,

Leoš Janáček (, baptised Leo Eugen Janáček; 3 July 1854 – 12 August 1928) was a Czech composer, musical theorist,

Leoš Janáček, son of schoolmaster Jiří (1815–1866) and Amalie (née Grulichová) Janáčková (1819–1884), was born in

Leoš Janáček, son of schoolmaster Jiří (1815–1866) and Amalie (née Grulichová) Janáčková (1819–1884), was born in

In 1927 – the year of the Sinfonietta's first performances in New York, Berlin and Brno – he began to compose his final operatic work, '' From the House of the Dead'', the third Act of which would be found on his desk after his death. In January 1928, he began his second string quartet, the '' Intimate Letters'', his "manifesto on love". Meanwhile, the Sinfonietta was performed in London, Vienna and Dresden. In his later years, Janáček became an international celebrity. He became a member of the

In 1927 – the year of the Sinfonietta's first performances in New York, Berlin and Brno – he began to compose his final operatic work, '' From the House of the Dead'', the third Act of which would be found on his desk after his death. In January 1928, he began his second string quartet, the '' Intimate Letters'', his "manifesto on love". Meanwhile, the Sinfonietta was performed in London, Vienna and Dresden. In his later years, Janáček became an international celebrity. He became a member of the

Janáček worked tirelessly throughout his life. He led the organ school, was a professor at the teachers institute and gymnasium in Brno, collected his "speech tunes" and was composing. From an early age, he presented himself as an individualist and his firmly formulated opinions often led to conflict. He unhesitatingly criticized his teachers, who considered him a defiant and anti-authoritarian student, yet his own students found him to be strict and uncompromising. Vilém Tauský, one of his pupils, described his encounters with Janáček as somewhat distressing for someone unused to his personality and noted that Janáček's characteristically staccato speech rhythms were reproduced in some of his operatic characters. In 1881, Janáček gave up his leading role with the ''Beseda brněnská'', as a response to criticism, but a rapid decline in ''Beseda''

Janáček worked tirelessly throughout his life. He led the organ school, was a professor at the teachers institute and gymnasium in Brno, collected his "speech tunes" and was composing. From an early age, he presented himself as an individualist and his firmly formulated opinions often led to conflict. He unhesitatingly criticized his teachers, who considered him a defiant and anti-authoritarian student, yet his own students found him to be strict and uncompromising. Vilém Tauský, one of his pupils, described his encounters with Janáček as somewhat distressing for someone unused to his personality and noted that Janáček's characteristically staccato speech rhythms were reproduced in some of his operatic characters. In 1881, Janáček gave up his leading role with the ''Beseda brněnská'', as a response to criticism, but a rapid decline in ''Beseda''' s performance quality led to his recall in 1882.

His married life, settled and calm in its early years, became increasingly tense and difficult following the death of his daughter, Olga, in 1903. Years of effort in obscurity took their toll, and almost ended his ambitions as a composer: "I was beaten down", he wrote later, "My own students gave me advice – how to compose, how to speak through the orchestra". Success in 1916 – when

Czech musicology at the beginning of the 20th century was strongly influenced by Romanticism, in particular by the styles of Wagner and Smetana. Performance practices were conservative, and actively resistant to stylistic innovation. During his lifetime, Janáček reluctantly conceded to Karel Kovařovic's instrumental rearrangement of ''Jenůfa'', most noticeably in the finale, in which Kovařovic added a more "festive" sound of trumpets and French horns, and doubled some instruments to support Janáček's "poor" instrumentation. The score of ''Jenůfa'' was later restored by Charles Mackerras, and is now performed according to Janáček's original intentions.

Another important Czech musicologist, Zdeněk Nejedlý, a great admirer of Smetana and later a communist Minister of Culture, condemned Janáček as an author who could accumulate a lot of material, but was unable to do anything with it. He called Janáček's style "unanimated", and his operatic duets "only speech melodies", without polyphonic strength. Nejedlý considered Janáček rather an amateurish composer, whose music did not conform to the style of Smetana. According to Charles Mackerras, he tried to destroy Janáček professionally. In 2006 Josef Bartoš, the Czech aesthetician and music critic, described Janáček as a "musical eccentric" who clung tenaciously to an imperfect, improvising style, but Bartoš appreciated some elements of Janáček's works and judged him more positively than Nejedlý.

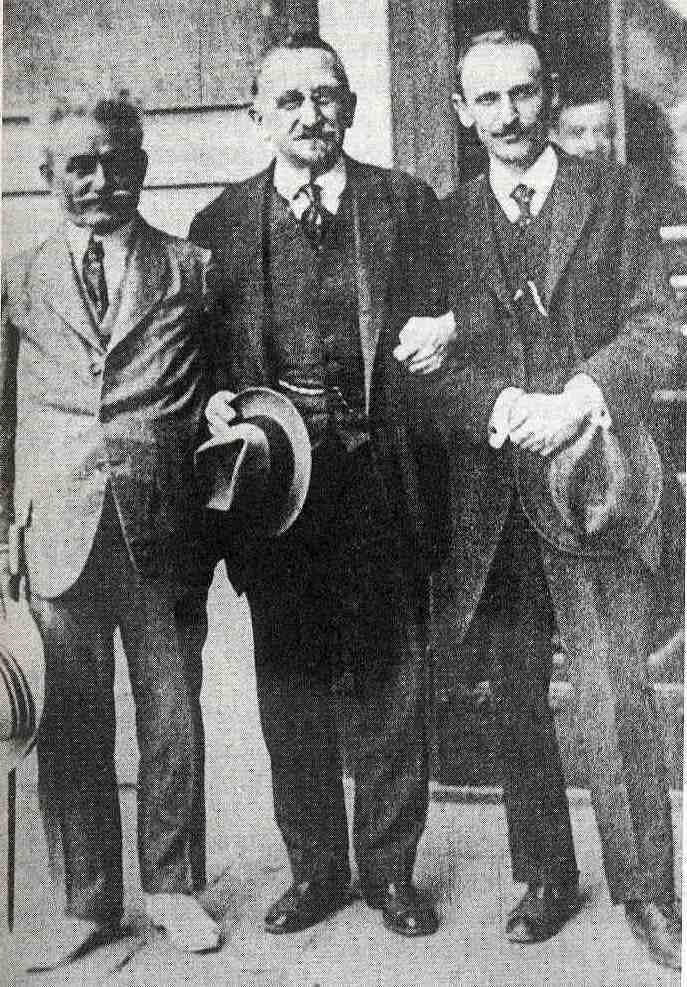

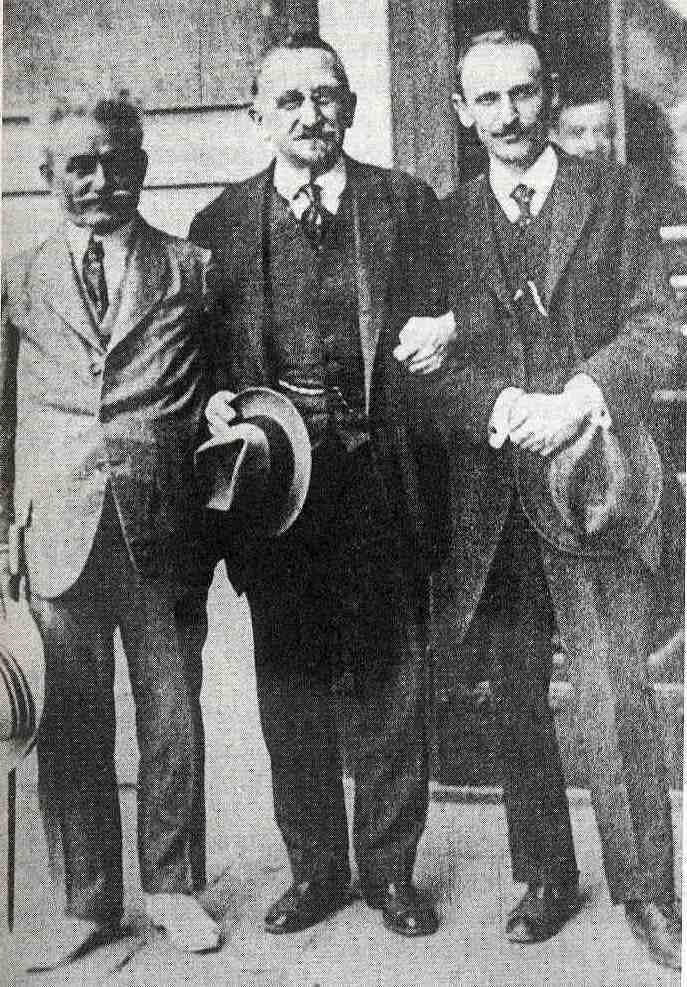

Janáček's friend and collaborator

Czech musicology at the beginning of the 20th century was strongly influenced by Romanticism, in particular by the styles of Wagner and Smetana. Performance practices were conservative, and actively resistant to stylistic innovation. During his lifetime, Janáček reluctantly conceded to Karel Kovařovic's instrumental rearrangement of ''Jenůfa'', most noticeably in the finale, in which Kovařovic added a more "festive" sound of trumpets and French horns, and doubled some instruments to support Janáček's "poor" instrumentation. The score of ''Jenůfa'' was later restored by Charles Mackerras, and is now performed according to Janáček's original intentions.

Another important Czech musicologist, Zdeněk Nejedlý, a great admirer of Smetana and later a communist Minister of Culture, condemned Janáček as an author who could accumulate a lot of material, but was unable to do anything with it. He called Janáček's style "unanimated", and his operatic duets "only speech melodies", without polyphonic strength. Nejedlý considered Janáček rather an amateurish composer, whose music did not conform to the style of Smetana. According to Charles Mackerras, he tried to destroy Janáček professionally. In 2006 Josef Bartoš, the Czech aesthetician and music critic, described Janáček as a "musical eccentric" who clung tenaciously to an imperfect, improvising style, but Bartoš appreciated some elements of Janáček's works and judged him more positively than Nejedlý.

Janáček's friend and collaborator

Sir Charles Mackerras, the Australian conductor who helped promote Janáček's works on the world's opera stages, described his style as "... completely new and original, different from anything else ... and impossible to pin down to any one style". According to Mackerras, Janáček's use of whole-tone scale differs from that of

Sir Charles Mackerras, the Australian conductor who helped promote Janáček's works on the world's opera stages, described his style as "... completely new and original, different from anything else ... and impossible to pin down to any one style". According to Mackerras, Janáček's use of whole-tone scale differs from that of

A detailed site on Leoš Janáček created by Gavin Plumley

*

A detailed site on Leoš Janáček by Brno Tourist Information Office

– a 1999 review by Thomas D. Svatos in '' The Prague Post''

Janáček "Žárlivost" (Jealousy overture) YouTube

{{DEFAULTSORT:Janacek, Leos 1854 births 1928 deaths 19th-century classical composers 19th-century Czech people 19th-century Czech male musicians 20th-century classical composers 20th-century Czech people 20th-century Czech male musicians Ballet composers Composers for pipe organ Czech folk-song collectors Czech male classical composers Czech opera composers Czech Romantic composers Deaths from pneumonia in Czechoslovakia Male opera composers People from Frýdek-Místek District People from the Margraviate of Moravia Pupils of Carl Reinecke University of Music and Theatre Leipzig alumni Burials at Brno Central Cemetery 19th-century musicologists

Leoš Janáček (, baptised Leo Eugen Janáček; 3 July 1854 – 12 August 1928) was a Czech composer, musical theorist,

Leoš Janáček (, baptised Leo Eugen Janáček; 3 July 1854 – 12 August 1928) was a Czech composer, musical theorist, folklorist

Folklore studies, less often known as folkloristics, and occasionally tradition studies or folk life studies in the United Kingdom, is the branch of anthropology devoted to the study of folklore. This term, along with its synonyms, gained currenc ...

, publicist, and teacher. He was inspired by Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The ...

n and other Slavic musics, including Eastern European folk music, to create an original, modern musical style.Sehnal and Vysloužil (2001), p. 175

Until 1895 he devoted himself mainly to folkloristic research. While his early musical output was influenced by contemporaries such as Antonín Dvořák

Antonín Leopold Dvořák ( ; ; 8 September 1841 – 1 May 1904) was a Czech composer. Dvořák frequently employed rhythms and other aspects of the folk music of Moravia and his native Bohemia, following the Romantic-era nationalist example ...

, his later, mature works incorporate his earlier studies of national folk music in a modern, highly original synthesis, first evident in the opera '' Jenůfa'', which was premiered in 1904 in Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

. The success of ''Jenůfa'' (often called the "Moravian national opera") at Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

in 1916 gave Janáček access to the world's great opera stages. Janáček's later works are his most celebrated. They include operas such as '' Káťa Kabanová'' and '' The Cunning Little Vixen'', the Sinfonietta, the '' Glagolitic Mass'', the rhapsody '' Taras Bulba'', two string quartets, and other chamber works. Along with Dvořák and Bedřich Smetana, he is considered one of the most important Czech composers.

Biography

Early life

Leoš Janáček, son of schoolmaster Jiří (1815–1866) and Amalie (née Grulichová) Janáčková (1819–1884), was born in

Leoš Janáček, son of schoolmaster Jiří (1815–1866) and Amalie (née Grulichová) Janáčková (1819–1884), was born in Hukvaldy

Hukvaldy (german: Hochwald) is a municipality and village in Frýdek-Místek District in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 2,100 inhabitants. It is known for the ruins of the third-largest castle in the Czech Republi ...

, Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The ...

(then part of the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central- Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

).Drlíková (2004), p. 7 He was a gifted child in a family of limited means, and showed an early musical talent in choral singing. His father wanted him to follow the family tradition and become a teacher, but he deferred to Janáček's obvious musical abilities.

In 1865, young Janáček enrolled as a ward of the foundation of the Abbey of St. Thomas in Brno, where he took part in choral singing under Pavel Křížkovský

Pavel Křížkovský (born as Karel Křížkovský) (9 January 1820, Kreuzendorf – 8 May 1885, Brno) was a Czech choral composer and conductor.

Life

Křížkovský was born in Kreuzendorf, Austrian Silesia. He was a chorister in a monaster ...

and occasionally played the organ. One of his classmates, František Neumann

František Neumann (16 June 187425 February 1929) was a Czech conductor and composer. He was particularly associated with the National Theatre in Brno, and the composer Leoš Janáček, the premieres of many of whose operas he conducted.

Biograp ...

, later described Janáček as an "excellent pianist, who played Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classic ...

symphonies perfectly in a piano duet with a classmate, under Křížkovský's supervision". Křížkovský found him a problematic and wayward student but recommended his entry to the Prague Organ School. Janáček later remembered Křížkovský as a great conductor and teacher.

Janáček originally intended to study piano and organ but eventually devoted himself to composition. He wrote his first vocal compositions while choirmaster of the ''Svatopluk Artisan's Association'' (1873–76). In 1874, he enrolled at the Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

organ school, under František Skuherský and František Blažek.Černušák (1963), p. 557

His student days in Prague were impoverished; with no piano in his room, he had to make do with a keyboard drawn on his tabletop. His criticism of Skuherský's performance of the Gregorian mass was published in the March 1875 edition of the journal ''Cecilie'' and led to his expulsion from the school, but Skuherský relented, and on 24 July 1875 Janáček graduated with the best results in his class.

On his return to Brno he earned a living as a music teacher, and conducted various amateur choir

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which sp ...

s. From 1876 he taught music at Brno's Teachers' Institute. Among his pupils there was Zdenka Schulzová, daughter of Emilian Schulz, the Institute director. She was later to be Janáček's wife. In 1876, he also became a piano student of Amálie Wickenhauserová-Nerudová, with whom he co-organized chamber concertos and performed in concerts over the following two years. In February 1876, he was voted Choirmaster of the ''Beseda brněnská'' Philharmonic Society. Apart from an interruption from 1879 to 1881, he remained its choirmaster and conductor until 1888.

From October 1879 to February 1880, he studied piano, organ, and composition at the Leipzig Conservatory. While there, he composed ''Thema con variazioni'' for piano in B flat, subtitled ''Zdenka's Variations''. Dissatisfied with his teachers (among them Oscar Paul and Leo Grill), and denied a studentship with Camille Saint-Saëns

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns (; 9 October 183516 December 1921) was a French composer, organist, conductor and pianist of the Romantic music, Romantic era. His best-known works include Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso (1863), the Piano C ...

in Paris, Janáček moved on to the Vienna Conservatory, where from April to June 1880, he studied composition with Franz Krenn

Franz Krenn (26 February 1816 – 18 June 1897) was an Austrian composer and composition teacher born in Droß. He studied under Ignaz von Seyfried in Vienna, and served as organist in a number of Viennese churches, becoming Kapellmeister of St ...

. He concealed his opposition to Krenn's neo-romanticism, but he quit Josef Dachs's classes and further piano study after he was criticised for his piano style and technique. He submitted a violin sonata (now lost) to a Vienna Conservatory competition, but the judges rejected it as being "too academic". Janáček left the conservatory in June 1880, disappointed despite Franz Krenn's very complimentary personal report.

He returned to Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

where, on 13 July 1881, he married his young pupil, Zdenka Schulzová.Drlíková (2004), p. 33

In 1881, Janáček founded and was appointed director of the organ school, and held this post until 1919, when the school became the Brno Conservatory. In the mid-1880s, Janáček began composing more systematically. Among other works, he created the ''Four male-voice choruses'' (1886), dedicated to Antonín Dvořák, and his first opera, '' Šárka'' (1887–88).Vysloužil, p. 224 During this period he began to collect and study folk music, songs and dances. In the early months of 1887, he sharply criticized the comic opera ''The Bridegrooms'', by Czech composer Karel Kovařovic

Karel Kovařovic (Prague, 9 December 1862 Prague, 6 December 1920) was a Czech composer and conductor.

Life

From 1873 to 1879 he studied clarinet, harp and piano at the Prague Conservatory.''Dopisy o životě hudebním i lidském, p. 484'' H ...

, in a ''Hudební listy'' journal review: "Which melody stuck in your mind? Which motif? Is this dramatic opera? No, I would write on the poster: 'Comedy performed together with music', since the music and the libretto aren't connected to each other". Janáček's review apparently led to mutual dislike and later professional difficulties when Kovařovic, as director of the National Theatre in Prague, refused to stage Janáček's opera '' Jenůfa''.

From the early 1890s, Janáček led the mainstream of folklorist activity in Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The ...

and Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

, using a repertoire of folk songs and dances in orchestral and piano arrangements. Many of the tunes he used had been recorded by him but a second source was Xavera Běhálková who sent him 70 to 100 tunes that she had gathered from around the Haná

Haná or Hanakia ( cs, Haná or ''Hanácko'', german: Hanna or ''Hanakei'') is an ethnographic region in central Moravia in the Czech Republic. Its core area is located along the eponymous river of Haná, around the towns of Vyškov and Pro ...

region of central Morovia.

Most of his achievements in this field were published in 1899–1901 though his interest in folklore would be lifelong.Janáčkovy záznamy hudebního a tanečního folkloru, p. 380 His compositional work was still influenced by the declamatory, dramatic style of Smetana and Dvořák. He expressed very negative opinions on German neo-classicism and especially on Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

in the ''Hudební listy'' journal, which he founded in 1884. The death of his second child, Vladimír, in 1890 was followed by an attempted opera, ''Beginning of the Romance'' (1891) and the cantata

A cantata (; ; literally "sung", past participle feminine singular of the Italian verb ''cantare'', "to sing") is a vocal composition with an instrumental accompaniment, typically in several movements, often involving a choir.

The meaning o ...

'' Amarus'' (1897).

Later years and masterworks

In the first decade of the 20th century, Janáček composed choral church music including '' Otčenáš'' (Our Father, 1901), ''Constitues'' (1903) and ''Ave Maria'' (1904). In 1901, the first part of his piano cycle '' On an Overgrown Path'' was published and gradually became one of his most frequently-performed works. In 1902, Janáček visited Russia twice. On the first occasion he took his daughter Olga to St. Petersburg, where she stayed to study Russian. Only three months later, he returned to St. Petersburg with his wife because Olga had become very ill. They took her back toBrno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

, but her health worsened.

Janáček expressed his painful feelings for his daughter in a new work, his opera ''Jenůfa'', in which the suffering of his daughter had transfigured into Jenůfa's. When Olga died in February 1903, Janáček dedicated ''Jenůfa'' to her memory. The opera was performed in Brno in 1904, with reasonable success, but Janáček felt this was no more than a provincial achievement. He aspired to recognition by the more influential Prague opera, but ''Jenůfa'' was refused there (twelve years passed before its first performance in Prague). Dejected and emotionally exhausted, Janáček went to Luhačovice

Luhačovice (; german: Luhatschowitz) is a spa town in Zlín District in the Zlín Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 5,000 inhabitants. It is known for the largest spa in Moravia. The town centre with the spa infrastructure is well preserv ...

spa to recover. There he met Kamila Urválková, whose love story supplied the theme for his next opera, '' Osud'' (''Destiny'').

In 1905, Janáček attended a demonstration in support of a Czech university in Brno, where the violent death of František Pavlík, a young joiner, at the hands of the police inspired his piano sonata, '' 1. X. 1905'' (''From The Street''). The incident led him to further promote the anti-German and anti-Austrian ethos of the ''Russian Circle'', which he had co-founded in 1897 and which would be officially banned by the Austrian police in 1915. In 1906, he approached the Czech poet Petr Bezruč, with whom he later collaborated, composing several choral works based on Bezruč's poetry. These included ''Kantor Halfar'' (1906), ''Maryčka Magdónova'' (1908), and ''Sedmdesát tisíc'' (1909).

Janáček's life in the first decade of the 20th century was complicated by personal and professional difficulties. He still yearned for artistic recognition from Prague. He destroyed some of his works, others remained unfinished. Nevertheless, he continued composing, and would create several remarkable choral, chamber, orchestral and operatic works, the most notable being the 1914 cantata, ''Věčné evangelium'' (''The Eternal Gospel''), '' Pohádka'' (''Fairy tale'') for 'cello and piano (1910), the 1912 piano cycle ''V mlhách'' ('' In the Mists'') and his first symphonic poem ''Šumařovo dítě'' (''A Fiddler's Child''). His fifth opera, ''Výlet pana Broučka do měsíce'', composed from 1908 to 1917, has been characterized as the most "purely Czech in subject and treatment" of all of Janáček's operas.

In 1916, he started a long professional and personal relationship with theatre critic, dramatist and translator Max Brod. In the same year, ''Jenůfa'', revised by Kovařovic, was finally accepted by the National Theatre. Its performance in Prague in 1916 was a great success, and brought Janáček his first acclaim. He was 62.

Following the Prague première, he began a relationship with singer Gabriela Horváthová, which led to his wife Zdenka's attempted suicide and their "informal" divorce. A year later (1917), he met Kamila Stösslová

Kamila Stösslová (née Neumannová; 1891–1935) was a Czech woman. The composer Leoš Janáček, upon meeting her in 1917 in the Moravian resort town of Luhačovice, fell deeply in love with her, despite the fact that both of them were marri ...

, a young married woman 38 years his junior, who was to inspire him for the remaining years of his life. He conducted an obsessive and (on his side at least) passionate correspondence with her, of nearly 730 letters.Drlíková (2004), p. 99 From 1917 to 1919, deeply inspired by Stösslová, he composed ''The Diary of One Who Disappeared

''Zápisník zmizelého'', or ''(The) Diary of One Who Disappeared'', is a half-hour Czech-language quasi-operatic song cycle for tenor, alto, three other women's voices and piano completed in 1919 by Leoš Janáček. Of its 22 sections, 18 are f ...

''. As he completed its final revision, he began his next 'Kamila' work, the opera '' Káťa Kabanová''.

In 1920, Janáček retired from his post as director of the Brno Conservatory but continued to teach until 1925. In 1921, he attended a lecture by the Indian philosopher-poet Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore (; bn, রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর; 7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He resh ...

and used a Tagore poem as the basis for the chorus '' The Wandering Madman'' (1922). At the same time, he encountered the microtonal works of Alois Hába. In the early 1920s, Janáček completed his opera '' The Cunning Little Vixen'', which had been inspired by a serialized novella in the newspaper Lidové noviny.

In Janáček's 70th year (1924), his biography was published by Max Brod, and he was interviewed by Olin Downes for ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

''. In 1925, he retired from teaching but continued composing and was awarded the first honorary doctorate to be given by Masaryk University

Masaryk University (MU) ( cs, Masarykova univerzita; la, Universitas Masarykiana Brunensis) is the second largest university in the Czech Republic, a member of the Compostela Group and the Utrecht Network. Founded in 1919 in Brno as the se ...

in Brno. In the spring of 1926, he created his Sinfonietta, a monumental orchestral work, which rapidly gained wide critical acclaim. In the same year, he went to England at the invitation of Rosa Newmarch. A number of his works were performed in London, including his first string quartet, the wind sextet ''Youth'', and his violin sonata. Shortly after, and still in 1926, he started to compose a setting to an Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic () was the first Slavic literary language.

Historians credit the 9th-century Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius with standardizing the language and using it in translating the Bible and othe ...

text. The result was the large-scale orchestral '' Glagolitic Mass''.

Janáček was an atheist, and critical of the organized Church, but religious themes appear frequently in his work. The ''Glagolitic Mass'' was partly inspired by the suggestion by a clerical friend and partly by Janáček's wish to celebrate the anniversary of Czechoslovak independence.

In 1927 – the year of the Sinfonietta's first performances in New York, Berlin and Brno – he began to compose his final operatic work, '' From the House of the Dead'', the third Act of which would be found on his desk after his death. In January 1928, he began his second string quartet, the '' Intimate Letters'', his "manifesto on love". Meanwhile, the Sinfonietta was performed in London, Vienna and Dresden. In his later years, Janáček became an international celebrity. He became a member of the

In 1927 – the year of the Sinfonietta's first performances in New York, Berlin and Brno – he began to compose his final operatic work, '' From the House of the Dead'', the third Act of which would be found on his desk after his death. In January 1928, he began his second string quartet, the '' Intimate Letters'', his "manifesto on love". Meanwhile, the Sinfonietta was performed in London, Vienna and Dresden. In his later years, Janáček became an international celebrity. He became a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts

The Prussian Academy of Arts (German: ''Preußische Akademie der Künste'') was a state arts academy first established in Berlin, Brandenburg, in 1694/1696 by prince-elector Frederick III, in personal union Duke Frederick I of Prussia, and la ...

in Berlin in 1927, along with Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

and Paul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith (; 16 November 189528 December 1963) was a German composer, music theorist, teacher, violist and conductor. He founded the Amar Quartet in 1921, touring extensively in Europe. As a composer, he became a major advocate of the ' ...

.Vysloužil, p. 227 His operas and other works were finally performed at the world stages.

In August 1928, he took an excursion to Štramberk with Kamila Stösslová and her son Otto, but caught a chill which developed into pneumonia. He died on 12 August 1928 in Ostrava

Ostrava (; pl, Ostrawa; german: Ostrau ) is a city in the north-east of the Czech Republic, and the capital of the Moravian-Silesian Region. It has about 280,000 inhabitants. It lies from the border with Poland, at the confluences of four riv ...

, at the sanatorium of Dr. L. Klein, at the age of 74. He was given a large public funeral that included music from the last scene of his ''Cunning Little Vixen''. He was buried in the Field of Honour at the Central Cemetery, Brno.

Personality

Janáček worked tirelessly throughout his life. He led the organ school, was a professor at the teachers institute and gymnasium in Brno, collected his "speech tunes" and was composing. From an early age, he presented himself as an individualist and his firmly formulated opinions often led to conflict. He unhesitatingly criticized his teachers, who considered him a defiant and anti-authoritarian student, yet his own students found him to be strict and uncompromising. Vilém Tauský, one of his pupils, described his encounters with Janáček as somewhat distressing for someone unused to his personality and noted that Janáček's characteristically staccato speech rhythms were reproduced in some of his operatic characters. In 1881, Janáček gave up his leading role with the ''Beseda brněnská'', as a response to criticism, but a rapid decline in ''Beseda''

Janáček worked tirelessly throughout his life. He led the organ school, was a professor at the teachers institute and gymnasium in Brno, collected his "speech tunes" and was composing. From an early age, he presented himself as an individualist and his firmly formulated opinions often led to conflict. He unhesitatingly criticized his teachers, who considered him a defiant and anti-authoritarian student, yet his own students found him to be strict and uncompromising. Vilém Tauský, one of his pupils, described his encounters with Janáček as somewhat distressing for someone unused to his personality and noted that Janáček's characteristically staccato speech rhythms were reproduced in some of his operatic characters. In 1881, Janáček gave up his leading role with the ''Beseda brněnská'', as a response to criticism, but a rapid decline in ''Beseda''Karel Kovařovic

Karel Kovařovic (Prague, 9 December 1862 Prague, 6 December 1920) was a Czech composer and conductor.

Life

From 1873 to 1879 he studied clarinet, harp and piano at the Prague Conservatory.''Dopisy o životě hudebním i lidském, p. 484'' H ...

finally decided to perform ''Jenůfa'' in Prague – brought its own problems. Janáček grudgingly resigned himself to the changes forced upon his work. Its success brought him into Prague's music scene and the attentions of soprano Gabriela Horvátová, who guided him through Prague society. Janáček was enchanted by her. On his return to Brno, he appears not to have concealed his new passion from Zdenka, who responded by attempting suicide. Janáček was furious with Zdenka and tried to instigate a divorce, but lost interest in Horvátová. Zdenka, anxious to avoid the public scandal of formal divorce, persuaded him to settle for an "informal" divorce. From then on, until Janáček's death, they lived separate lives in the same household.

In 1917, he began his lifelong, inspirational and unrequited passion for Kamila Stösslová

Kamila Stösslová (née Neumannová; 1891–1935) was a Czech woman. The composer Leoš Janáček, upon meeting her in 1917 in the Moravian resort town of Luhačovice, fell deeply in love with her, despite the fact that both of them were marri ...

, who neither sought nor rejected his devotion.Přibáňová (2007), p. 9 Janáček pleaded for first-name terms in their correspondence. In 1927, she finally agreed and signed herself "Tvá Kamila" (Your Kamila) in a letter, which Zdenka found. This revelation provoked a furious quarrel between Zdenka and Janáček, though their living arrangements did not change – Janáček seems to have persuaded her to stay. In 1928, the year of his death, Janáček confessed his intention to publicize his feelings for Stösslová. Max Brod had to dissuade him.Přibáňová (2007), p. 10 Janáček's contemporaries and collaborators described him as mistrustful and reserved, but capable of obsessive passion for those he loved. His overwhelming passion for Stösslová was sincere but verged upon self-destruction. Their letters remain an important source for Janáček's artistic intentions and inspiration. His letters to his long-suffering wife are, by contrast, mundanely descriptive. Zdenka seems to have destroyed all hers to Janáček. Only a few postcards survive.

Style

In 1874, Janáček became friends withAntonín Dvořák

Antonín Leopold Dvořák ( ; ; 8 September 1841 – 1 May 1904) was a Czech composer. Dvořák frequently employed rhythms and other aspects of the folk music of Moravia and his native Bohemia, following the Romantic-era nationalist example ...

, and began composing in a relatively traditional Romantic style. After his opera '' Šárka'' (1887–1888), his style absorbed elements of Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The ...

n and Slovak folk music

Folk music is a music genre that includes traditional folk music and the contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be called world music. Traditional folk music has ...

.

His musical assimilation of the rhythm, pitch contour and inflections of normal Czech speech ( Moravian dialect) helped create the very distinctive vocal melodies of his opera '' Jenůfa'' (1904), whose 1916 success in Prague was to be the turning point in his career. In ''Jenůfa'', Janáček developed and applied the concept of "speech tunes" to build a unique musical and dramatic style quite independent of "Wagnerian" dramatic method. He studied the circumstances in which "speech tunes" changed, the psychology and temperament of speakers and the coherence within speech, all of which helped render the dramatically truthful roles of his mature operas, and became one of the most significant markers of his style. Janáček took these stylistic principles much farther in his vocal writing than Modest Mussorgsky

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky ( rus, link=no, Модест Петрович Мусоргский, Modest Petrovich Musorgsky , mɐˈdɛst pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ ˈmusərkskʲɪj, Ru-Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky version.ogg; – ) was a Russian compo ...

, and thus anticipates the later work of Béla Bartók

Béla Viktor János Bartók (; ; 25 March 1881 – 26 September 1945) was a Hungarian composer, pianist, and ethnomusicologist. He is considered one of the most important composers of the 20th century; he and Franz Liszt are regarded as Hu ...

.Samson 1977 The stylistic basis for his later works originates in the period of 1904–1918, but Janáček composed most of his output – and his best known works – in the last decade of his life.

Much of Janáček's work displays great originality and individuality. It employs a vastly expanded view of tonality

Tonality is the arrangement of pitches and/or chords of a musical work in a hierarchy of perceived relations, stabilities, attractions and directionality. In this hierarchy, the single pitch or triadic chord with the greatest stability is ca ...

, uses unorthodox chord spacings and structures, and often, modality

Modality may refer to:

Humanities

* Modality (theology), the organization and structure of the church, as distinct from sodality or parachurch organizations

* Modality (music), in music, the subject concerning certain diatonic scales

* Modaliti ...

: "there is no music without key. Atonality

Atonality in its broadest sense is music that lacks a tonal center, or key. ''Atonality'', in this sense, usually describes compositions written from about the early 20th-century to the present day, where a hierarchy of harmonies focusing on a ...

abolishes definite key, and thus tonal modulation

In electronics and telecommunications, modulation is the process of varying one or more properties of a periodic waveform, called the '' carrier signal'', with a separate signal called the ''modulation signal'' that typically contains informat ...

.... Folksong knows of no atonality." Janáček features accompaniment

Accompaniment is the musical part which provides the rhythmic and/or harmonic support for the melody or main themes of a song or instrumental piece. There are many different styles and types of accompaniment in different genres and styles o ...

figures and patterns, with (according to Jim Samson) "the on-going movement of his music...similarly achieved by unorthodox means; often a discourse of short, 'unfinished' phrases

In syntax and grammar, a phrase is a group of words or singular word acting as a grammatical unit. For instance, the English expression "the very happy squirrel" is a noun phrase which contains the adjective phrase "very happy". Phrases can consi ...

comprising constant repetitions of short motifs which gather momentum in a cumulative manner." Janáček named these motifs "sčasovka" in his theoretical works. "Sčasovka" has no strict English equivalent, but John Tyrrell, a leading specialist on Janáček's music, describes it as "a little flash of time, almost a kind of musical capsule, which Janáček often used in slow music as tiny swift motifs with remarkably characteristic rhythms that are supposed to pepper the musical flow." Janáček's use of these repeated motifs demonstrates a remote similarity to minimalist composers (Sir Charles Mackerras called Janáček "the first minimalist composer").

Inspiration

Folklore

Janáček was deeply influenced by folklore, and byMoravian folk music

Moravian traditional music or Moravian folk music represents a part of the European musical culture connected with the Moravian region of the Czech Republic. Styles of Moravian traditional music vary by location and subject, but much of it is ...

in particular, but not by the pervasive, idealized 19th century romantic folklore variant. He took a realistic, descriptive and analytic approach to the material. Moravian folk songs, compared with their Bohemian counterparts, are much freer and more irregular in their metrical and rhythmic structure, and more varied in their melodic intervals.Zemanová (2002), p. 61 In his study of Moravian modes, Janáček found that the peasant musicians did not know the names of the modes and had their own ways of referring to them. He considered their Moravian modulation, as he called it, a general characteristic of this region's folk music.

Janáček partly composed the original piano accompaniments to more than 150 folk songs, respectful of their original function and context, and partly used folk inspiration in his own works, especially in his mature compositions. His work in this area was not stylistically imitative; instead, he developed a new and original musical aesthetic based on a deep study of the fundamentals of folk music. Through his systematic notation of folk songs as he heard them, Janáček developed an exceptional sensitivity to the melodies and rhythms of speech, from which he compiled a collection of distinctive segments he called "speech tunes". He used these "essences" of spoken language in his vocal and instrumental works. The roots of his style, marked by the lilts of human speech, emerge from the world of folk music.

Russia

Janáček's deep and lifelong affection for Russia and Russian culture represents another important element of his musical inspiration. In 1888 he attended the Prague performance of Tchaikovsky's music, and met the older composer. Janáček profoundly admired Tchaikovsky, and particularly appreciated his highly developed musical thought in connection with the use of Russian folk motifs. Janáček's Russian inspiration is especially apparent in his later chamber, symphonic and operatic output. He closely followed developments in Russian music from his early years, and in 1896, following his first visit to Russia, he founded a ''Russian Circle'' in Brno. Janáček read Russian authors in their original language. Their literature offered him an enormous and reliable source of inspiration, though this did not blind him to the problems of Russian society. He was twenty-two years old when he wrote his first composition based on a Russian theme: a melodrama, ''Death'', set to Lermontov's poem. In his later works, he often used literary models with sharply contoured plots. In 1910 Zhukovsky's ''Tale of Tsar Berendei'' inspired him to write the ''Fairy Tale for Cello and Piano''. He composed the rhapsody ''Taras Bulba'' (1918) to Gogol's short story, and five years later, in 1923, completed his first string quartet, inspired by Tolstoy's '' Kreutzer Sonata''. Two of his later operas were based on Russian themes: ''Káťa Kabanová'', composed in 1921 toAlexander Ostrovsky

Alexander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky (russian: Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Остро́вский; ) was a Russian playwright, generally considered the greatest representative of the Russian realistic period. The author of 47 original ...

's play ''The Storm'', and his last work, ''From the House of the Dead'', which transformed Dostoyevsky's vision of the world into an exciting collective drama.

Other composers

Janáček always deeply admired Antonín Dvořák, to whom he dedicated some of his works. He rearranged part of Dvořák'sMoravian Duets

''Moravian Duets'' (in cs, Moravské dvojzpěvy) by Antonín Dvořák is a cycle of 23 Moravian folk poetry settings for two voices with piano accompaniment, composed between 1875 and 1881. The Duets, published in three volumes, Op. 20 (B.&n ...

for mixed choir with original piano accompaniment. In the early years of the 20th century, Janáček became increasingly interested in the music of other European composers. His opera ''Destiny'' was a response to another significant and famous work in contemporary Bohemia – Louise, by the French composer Gustave Charpentier. The influence of Giacomo Puccini

Giacomo Puccini ( Lucca, 22 December 1858Bruxelles, 29 November 1924) was an Italian composer known primarily for his operas. Regarded as the greatest and most successful proponent of Italian opera after Verdi, he was descended from a long ...

is apparent particularly in Janáček's later works, for example in his opera ''Káťa Kabanová''. Although he carefully observed developments in European music, his operas remained firmly connected with Czech and Slavic themes.

Music theorist

Musicology

Janáček created his music theory works, essays and articles over a period of fifty years, from 1877 to 1927. He wrote and edited the ''Hudební listy'' journal, and contributed to many specialist music journals, such as ''Cecílie'', ''Hlídka'' and ''Dalibor''. He also completed several extensive studies, as ''Úplná nauka o harmonii'' (The Complete Harmony Theory), ''O skladbě souzvukův a jejich spojův'' (On the Construction of Chords and Their Connections) and ''Základy hudebního sčasování'' (Basics of Musical ''Sčasování''). In his essays and books, Janáček examined various musical topics, forms, melody and harmony theories, dyad and triad chords, counterpoint (or "opora", meaning "support") and devoted himself to the study of the mental composition. His theoretical works stress the Czech term "sčasování", Janáček's specific word for rhythm, which has relation to time ("čas" in Czech), and the handling of time in music composition. He distinguished several types of rhythm (''sčasovka''): "znící" (sounding) – meaning any rhythm, "čítací" (counting) – meaning smaller units measuring the course of rhythm; and "scelovací" (summing) – a long value comprising the length of a rhythmical unit. Janáček used the combination of their mutual action widely in his own works.Other writings

Leoš Janáček's literary legacy represents an important illustration of his life, public work and art between 1875 and 1928. He contributed not only to music journals, but wrote essays, reports, reviews, feuilletons, articles and books. His work in this area comprises around 380 individual items. His writing changed over time, and appeared in many genres. Nevertheless, the critical and theoretical sphere remained his main area of interest.Folk music research

Janáček came from a region characterized by its deeply rootedfolk culture

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, ranging fro ...

, which he explored as a young student under Pavel Křížkovský.Janáčkovy záznamy hudebního a tanečního folkloru, p. 381 His meeting with the folklorist and dialectologist František Bartoš (1837–1906) was decisive in his own development as a folklorist and composer, and led to their collaborative and systematic collections of folk songs. Janáček became an important collector in his own right, especially of Lachian, Moravian Slovakian, Moravian Wallachia

Moravian Wallachia ( cs, Moravské Valašsko, or simply ''Valašsko''; ro, Valahia Moravă) is a mountainous ethnoregion located in the easternmost part of Moravia in the Czech Republic, near the Slovak border, roughly centered on the cities ...

n and Slovakian songs. From 1879, his collections included transcribed speech intonations. He was one of the organizers of the ''Czech-Slavic Folklore Exhibition'', an important event in Czech culture at the end of 19th century. From 1905 he was President of the newly instituted ''Working Committee for Czech National Folksong in Moravia and Silesia'', a branch of the Austrian institute ''Das Volkslied in Österreich'' (Folksong in Austria), which was established in 1902 by the Viennese publishing house Universal Edition

Universal Edition (UE) is a classical music publishing firm. Founded in 1901 in Vienna, they originally intended to provide the core classical works and educational works to the Austrian market (which had until then been dominated by Leipzig-bas ...

. Janáček was a pioneer and propagator of ethnographic

Ethnography (from Greek ''ethnos'' "folk, people, nation" and ''grapho'' "I write") is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject ...

photography in Moravia and Silesia. In October 1909 he acquired an Edison phonograph and became one of the first to use phonographic recording as a folklore research tool. Several of these recording sessions have been preserved, and were reissued in 1998.

Criticism

Czech musicology at the beginning of the 20th century was strongly influenced by Romanticism, in particular by the styles of Wagner and Smetana. Performance practices were conservative, and actively resistant to stylistic innovation. During his lifetime, Janáček reluctantly conceded to Karel Kovařovic's instrumental rearrangement of ''Jenůfa'', most noticeably in the finale, in which Kovařovic added a more "festive" sound of trumpets and French horns, and doubled some instruments to support Janáček's "poor" instrumentation. The score of ''Jenůfa'' was later restored by Charles Mackerras, and is now performed according to Janáček's original intentions.

Another important Czech musicologist, Zdeněk Nejedlý, a great admirer of Smetana and later a communist Minister of Culture, condemned Janáček as an author who could accumulate a lot of material, but was unable to do anything with it. He called Janáček's style "unanimated", and his operatic duets "only speech melodies", without polyphonic strength. Nejedlý considered Janáček rather an amateurish composer, whose music did not conform to the style of Smetana. According to Charles Mackerras, he tried to destroy Janáček professionally. In 2006 Josef Bartoš, the Czech aesthetician and music critic, described Janáček as a "musical eccentric" who clung tenaciously to an imperfect, improvising style, but Bartoš appreciated some elements of Janáček's works and judged him more positively than Nejedlý.

Janáček's friend and collaborator

Czech musicology at the beginning of the 20th century was strongly influenced by Romanticism, in particular by the styles of Wagner and Smetana. Performance practices were conservative, and actively resistant to stylistic innovation. During his lifetime, Janáček reluctantly conceded to Karel Kovařovic's instrumental rearrangement of ''Jenůfa'', most noticeably in the finale, in which Kovařovic added a more "festive" sound of trumpets and French horns, and doubled some instruments to support Janáček's "poor" instrumentation. The score of ''Jenůfa'' was later restored by Charles Mackerras, and is now performed according to Janáček's original intentions.

Another important Czech musicologist, Zdeněk Nejedlý, a great admirer of Smetana and later a communist Minister of Culture, condemned Janáček as an author who could accumulate a lot of material, but was unable to do anything with it. He called Janáček's style "unanimated", and his operatic duets "only speech melodies", without polyphonic strength. Nejedlý considered Janáček rather an amateurish composer, whose music did not conform to the style of Smetana. According to Charles Mackerras, he tried to destroy Janáček professionally. In 2006 Josef Bartoš, the Czech aesthetician and music critic, described Janáček as a "musical eccentric" who clung tenaciously to an imperfect, improvising style, but Bartoš appreciated some elements of Janáček's works and judged him more positively than Nejedlý.

Janáček's friend and collaborator Václav Talich

Václav Talich (; 28 May 1883, Kroměříž – 16 March 1961, Beroun) was a Czech violinist and later a musical pedagogue. He is remembered today as one of the greatest conductors of the 20th century, the object of countless reissues of his ...

, former chief-conductor of the Czech Philharmonic

The Česká filharmonie (Czech Philharmonic) is a symphony orchestra based in Prague. The orchestra's principal concert venue is the Rudolfinum.

History

The name "Czech Philharmonic Orchestra" appeared for the first time in 1894, as the titl ...

, sometimes adjusted Janáček's scores, mainly for their instrumentation and dynamics; some critics sharply attacked him for doing so. Talich re-orchestrated ''Taras Bulba'' and the Suite from ''Cunning Little Vixen'' justifying the latter with the claim that "it was not possible to perform it in the Prague National Theatre

The National Theatre ( cs, Národní divadlo) in Prague is known as the alma mater of Czech opera, and as the national monument of Czech history and art.

The National Theatre belongs to the most important Czech cultural institutions, with a ri ...

unless it was entirely re-orchestrated". Talich's rearrangement rather emasculated the specific sounds and contrasts of Janáček's original, but was the standard version for many years. Charles Mackerras started to research Janáček's music in the 1960s, and gradually restored the composer's distinctive scoring. The critical edition of Janáček's scores is published by the Czech ''Editio Janáček''.

Legacy

Janáček belongs to a wave of twentieth-century composers who sought greater realism and greater connection with everyday life, combined with a more all-encompassing use of musical resources. His operas, in particular, demonstrate the use of "speech"-derived melodic lines, folk and traditional material, and complex modal musical argument. Janáček's works are still regularly performed around the world, and are generally considered popular with audiences. He would also inspire later composers in his homeland, as well as music theorists (among them Jaroslav Volek) to place modal development alongsideharmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. Howeve ...

of importance in music.

The operas of his mature period, '' Jenůfa'' (1904), '' Káťa Kabanová'' (1921), '' The Cunning Little Vixen'' (1924), ''The Makropulos Affair

''Věc Makropulos'' is a Czech play written by Karel Čapek. Its title—literally ''The Makropulos Thing''—has been variously rendered in English as ''The Makropulos Affair'', ''The Makropulos Case'', or ''The Makropulos Secret'' (Čapek's o ...

'' (1926) and '' From the House of the Dead'' (after a novel by Dostoyevsky and premièred posthumously in 1930) are considered his finest works. The Australian conductor Sir Charles Mackerras became very closely associated with Janáček's operas.

Janáček's chamber music, while not especially voluminous, includes works which are widely considered twentieth-century classics, particularly his two string quartet

The term string quartet can refer to either a type of musical composition or a group of four people who play them. Many composers from the mid-18th century onwards wrote string quartets. The associated musical ensemble consists of two violinist ...

s: Quartet No. 1, "The Kreutzer Sonata" inspired by the Tolstoy novel, and the Quartet No. 2, "Intimate Letters". Milan Kundera

Milan Kundera (, ; born 1 April 1929) is a Czech writer who went into exile in France in 1975, becoming a naturalised French citizen in 1981. Kundera's Czechoslovak citizenship was revoked in 1979, then conferred again in 2019. He "sees himsel ...

called these compositions the peak of Janáček's output.Kundera (1996), p. 180

The world première of Janáček's lyrical Concertino for piano, two violins, viola, clarinet, French horn and bassoon took place in Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

on 16 February 1926. It was also performed at the Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

Festival of Modern Music in 1927 by Ilona Štěpánová-Kurzová.

A comparable chamber work for an even more unusual set of instruments, the Capriccio for piano left hand, flute, two trumpets, three trombones and tenor tuba, was written for pianist Otakar Hollmann, who lost the use of his right hand during World War I. After its première in Prague on 2 March 1928, the Capriccio gained considerable acclaim in the musical world.

Other well known pieces by Janáček include the '' Sinfonietta'', the '' Glagolitic Mass'' (the text written in Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic () was the first Slavic literary language.

Historians credit the 9th-century Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius with standardizing the language and using it in translating the Bible and othe ...

), and the rhapsody '' Taras Bulba''. These pieces and the above-mentioned five late operas were all written in the last decade of Janáček's life.

Janáček established a school of composition in Brno. Among his notable pupils were Jan Kunc, Václav Kaprál, Vilém Petrželka

Petrželka in 1931

Vilém Petrželka (10 September 1889, Brno, Moravia – 10 January 1967, Brno) was a prominent Czech composer and conductor.

Petrželka was a pupil of Leoš Janáček, Vítězslav Novák and Karel Hoffmeister. From 1914 he ...

, Jaroslav Kvapil

Jaroslav Kvapil (25 September 1868 in Chudenice, Kingdom of Bohemia – 10 January 1950 in Prague) was a Czech poet, theatre director, translator, playwright, and librettist. From 1900 he was a director and Dramaturg at the National Theatr ...

, Osvald Chlubna

Osvald Chlubna (July 22, 1893 in Brno – October 30, 1971 in Brno) was a prominent Czech composer. Intending originally to study engineering, Chlubna switched his major and from 1914 to 1924, he studied composition with Leoš Janáček. Until 1953 ...

, Břetislav Bakala

Břetislav Bakala (February 12, 1897 in Fryšták – April 1, 1958 in Brno) was a Czech conductor, pianist, and composer. His career was centred on Brno and he was particularly associated with the music of Leoš Janáček.

Life and career

...

and Pavel Haas. Most of his students neither imitated nor developed Janáček's style, which left him no direct stylistic descendants. According to Milan Kundera, Janáček developed a personal, modern style in relative isolation from contemporary modernist movements but was in close contact with developments in modern European music. His path towards the innovative "modernism" of his later years was long and solitary, and he achieved true individuation as a composer around his 50th year.

Sir Charles Mackerras, the Australian conductor who helped promote Janáček's works on the world's opera stages, described his style as "... completely new and original, different from anything else ... and impossible to pin down to any one style". According to Mackerras, Janáček's use of whole-tone scale differs from that of

Sir Charles Mackerras, the Australian conductor who helped promote Janáček's works on the world's opera stages, described his style as "... completely new and original, different from anything else ... and impossible to pin down to any one style". According to Mackerras, Janáček's use of whole-tone scale differs from that of Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most infl ...

, his folk music inspiration is absolutely dissimilar from Dvořák's and Smetana's, and his characteristically complex rhythms differ from the techniques of the young Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential 20th-century clas ...

.

The French conductor and composer Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music.

Born in Mo ...

, who interpreted Janáček's operas and orchestral works, called his music surprisingly modern and fresh: "Its repetitive pulse varies through changes in rhythm, tone and direction." He described his opera ''From the House of the Dead'' as "primitive, in the best sense, but also extremely strong, like the paintings of Léger, where the rudimentary character allows a very vigorous kind of expression".

The Czech conductor, composer and writer Jaroslav Vogel wrote what was for a long time considered the standard biography of Janáček in 1958. It first appeared in German translation, and in the Czech original in 1963. The first English translation came out in 1962 and it was later re-issued, in a version revised by Karel Janovický

Karel Janovický (born 18 February 1930) is a Czech composer, pianist, BBC producer and administrator who has lived in the UK since 1950, one of the youngest of the group of European émigré composers who came to live and work in Britain during t ...

, in 1981. Charles Mackerras regarded it as his "Janáček bible".

Janáček's life has been featured in several films. In 1974 Eva Marie Kaňková made a short documentary ''Fotograf a muzika'' (The Photographer and the Music) about the Czech photographer Josef Sudek

Josef Sudek (17 March 1896 – 15 September 1976) was a Czech photographer, best known for his photographs of Prague.

Life

Sudek was born in Kolín, Bohemia. He was originally a bookbinder. During the First World War he was drafted into the Au ...

and his relationship to Janáček's work. In 1983 the Brothers Quay

Stephen and Timothy Quay ( ; born June 17, 1947) are American identical twin brothers and stop-motion animators who are better known as the Brothers Quay or Quay Brothers. They were also the recipients of the 1998 Drama Desk Award for Outstandin ...

produced a stop motion

Stop motion is an animated filmmaking technique in which objects are physically manipulated in small increments between individually photographed frames so that they will appear to exhibit independent motion or change when the series of frames i ...

animated film, ''Leoš Janáček: Intimate Excursions'', about Janáček's life and work, and in 1986 the Czech director Jaromil Jireš

Jaromil Jireš (10 December 1935 – 24 October 2001) was a director associated with the Czechoslovak New Wave movement.

His 1963 film '' The Cry'' was entered into the 1964 Cannes Film Festival. It is often described as the first film of the Cze ...

made ''Lev s bílou hřívou'' (Lion with the White Mane), which showed the amorous inspiration behind Janáček's works. In Search of Janáček is a Czech documentary directed in 2004 by Petr Kaňka, made to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Janáček's birth. An animated cartoon version of '' The Cunning Little Vixen'' was made in 2003 by the BBC, with music performed by the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin and conducted by Kent Nagano. A re-arrangement of the opening of the ''Sinfonietta'' was used by the progressive rock band Emerson, Lake & Palmer

Emerson, Lake & Palmer (informally known as ELP) were an English progressive rock supergroup formed in London in 1970. The band consisted of Keith Emerson (keyboards), Greg Lake (vocals, bass, guitar, producer) and Carl Palmer (drums, percus ...

for the song "Knife-Edge" on their 1970 debut album.

The Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra

The Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra (''Janáčkova filharmonie Ostrava'') is a Czech orchestra based in Ostrava, Czech Republic. Named after composer Leoš Janáček, the orchestra performs its concerts at the City of Ostrava Cultural Centre.

H ...

was established in 1954. Today the 116-piece ensemble is associated with mostly contemporary music but also regularly performs works from the classical repertoire. The orchestra is resident at the House of Culture Vítkovice (Dům kultury Vítkovice) in Ostrava

Ostrava (; pl, Ostrawa; german: Ostrau ) is a city in the north-east of the Czech Republic, and the capital of the Moravian-Silesian Region. It has about 280,000 inhabitants. It lies from the border with Poland, at the confluences of four riv ...

, Czech Republic. The orchestra tours extensively and has performed in Europe, the U.S., Australia, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

; its current music director is Theodore Kuchar.

Asteroid 2073 Janáček, discovered in 1974 by Luboš Kohoutek, is named in his honor. The Haruki Murakami

is a Japanese writer. His novels, essays, and short stories have been bestsellers in Japan and internationally, with his work translated into 50 languages and having sold millions of copies outside Japan. He has received numerous awards for his ...

novel 1Q84

is a novel written by Japanese writer Haruki Murakami, first published in three volumes in Japan in 2009–10. It covers a fictionalized year of 1984 in parallel with a "real" one. The novel is a story of how a woman named Aomame begins to not ...

uses Janáček's Sinfonietta as a recurring plot point. Ostrava

Ostrava (; pl, Ostrawa; german: Ostrau ) is a city in the north-east of the Czech Republic, and the capital of the Moravian-Silesian Region. It has about 280,000 inhabitants. It lies from the border with Poland, at the confluences of four riv ...

's international airport

An international airport is an airport with customs and border control facilities enabling passengers to travel between countries around the world. International airports are usually larger than domestic airports and they must feature longer r ...

was renamed after Janáček in November 2006.

Selected writings

*''O dokonalé představě dvojzvuku'' (On the Perfect Image of Dyad Chord) (1885–1886) *''Bedřich Smetana o formách hudebních'' (Bedřich Smetana: On Music Forms) (1886) *''O představě tóniny'' (On an Idea of Key) (1886–1887) *''O vědeckosti nauk o harmonii'' (On Scientism of Harmony Theories) (1887) *''O trojzvuku'' (On a Triad) (1887–1888) *''Slovíčko o kontrapunktu'' (A Word on Counterpoint) (1888) *''Nový proud v teorii hudební'' (New Stream in Music Theory) (1894) *''O skladbě souzvukův a jejich spojův'' (On the Construction of Chords and Their Progressions) (1896) *''Moderní harmonická hudba'' (Modern Harmonic Music) (1907) *''Můj názor o sčasování (rytmu)'' (My Opinion of "sčasování" (Rhythm)) (1907) *''Z praktické části o sčasování (rytmu)'' (On "sčasování" From practice) (1908) *''Váha reálních motivů'' (The Weight of Real Motifs) (1910) *''O průběhu duševní práce skladatelské'' (On the Course of Mental Compositional Work) (1916) *''Úplná nauka o harmonii'' (Harmony Theory) (1920)References

Sources

* * * * * * * (notes based on English summary) * (notes based on English summary) * BA 9502. ISMN M-2601-0365-8 * * * * * (notes based on English summary) * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * Štědroň, Miloš (1998). ''Leoš Janáček a hudba 20. století''. Brno: Nadace Universitas Masarykiana. . * * * * * *External links

*A detailed site on Leoš Janáček created by Gavin Plumley

*

A detailed site on Leoš Janáček by Brno Tourist Information Office

– a 1999 review by Thomas D. Svatos in '' The Prague Post''

Janáček "Žárlivost" (Jealousy overture) YouTube

{{DEFAULTSORT:Janacek, Leos 1854 births 1928 deaths 19th-century classical composers 19th-century Czech people 19th-century Czech male musicians 20th-century classical composers 20th-century Czech people 20th-century Czech male musicians Ballet composers Composers for pipe organ Czech folk-song collectors Czech male classical composers Czech opera composers Czech Romantic composers Deaths from pneumonia in Czechoslovakia Male opera composers People from Frýdek-Místek District People from the Margraviate of Moravia Pupils of Carl Reinecke University of Music and Theatre Leipzig alumni Burials at Brno Central Cemetery 19th-century musicologists