Ledringhem on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ledringhem ( vls, Ledringem) is a

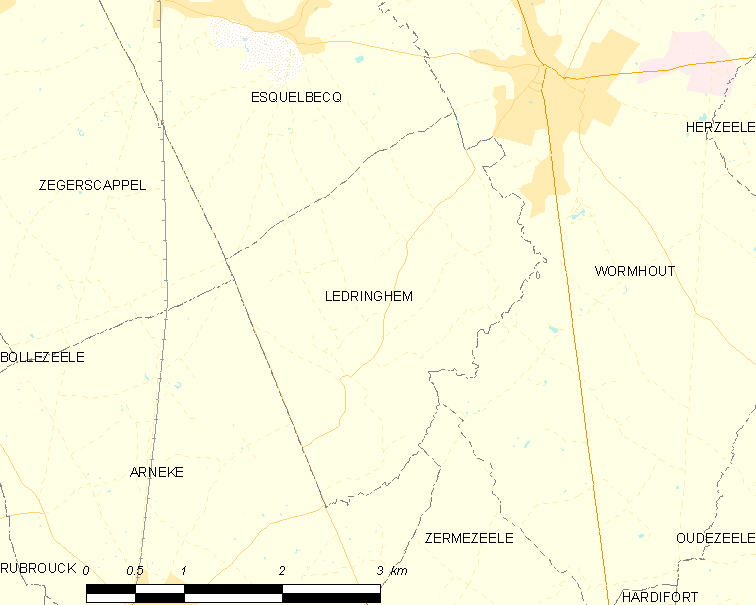

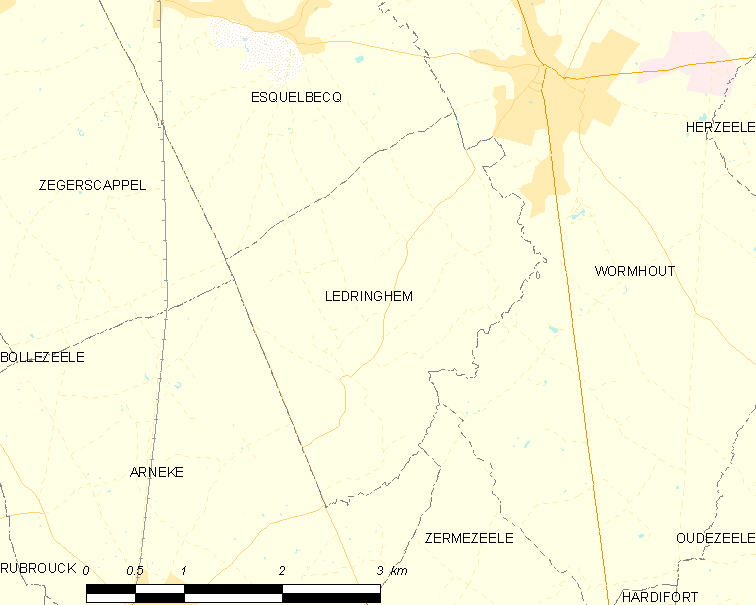

The village is about 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) southwest of the small town of Wormhout, and approximately 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) north of

The village is about 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) southwest of the small town of Wormhout, and approximately 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) north of

The river Peene Becque constitutes the southern border between Ledringhem and

The river Peene Becque constitutes the southern border between Ledringhem and

Other smaller roads include ''rue Henri Wallaert'', ''chemin d'

The village is a little off the ancient Roman road, now D52, roughly North-South in direction.

''Le soulèvement de la Flandre maritime de 1323–1328''

(1900), p. 125. On gallica.bnf.fr (French) *''Leodredingas'' in 1614–1616 by Ferry de Locre (Ferreolus Locrius) in p. 86 of his ''Chronicum belgicum'' (''Chronicon belgicum, ab anno CCLVIII ad annum usque M.D.C. continuo perductum.'') Atrecht (Arras), a work published posthumously by his father Philippus Locrius *''Leregem'' in 1609 (

*''Leregem'' in 1609 (

(French)Les Flamands de France: Études sur leur langue, leur littérature et leurs Monuments, Louis de Baecker, 1830, page 40

(French) In reality, the place-name Ledringhem is typical Germanic, with the common Germanic double end ''-ing-hem'' (name suffix + toponymic appellative) found everywhere in Flanders, corresponding exactly to the English one ''-ing-ham'' (e. g. Nottingham). This ''-ing-hem'' turned into ''-egem'' where Flemish-Dutch continued to be spoken, but remained the same ''-ing-hem'' where the Picard language replaced the Flemish one in the Middle Ages. The French language has retained the old version, and often frenchified it as ''-eng-hien'' or ''-ing-hien'' (see above ''Ledringhien'' in 1330, similar to

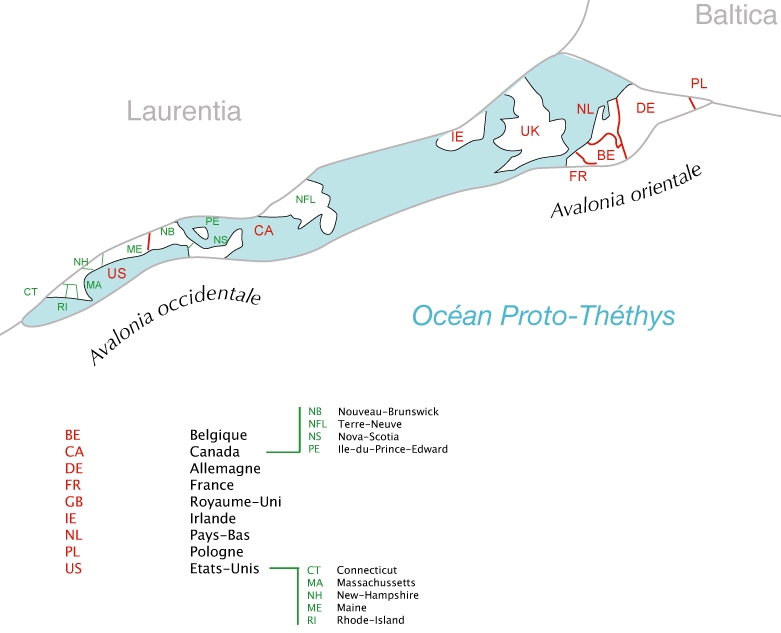

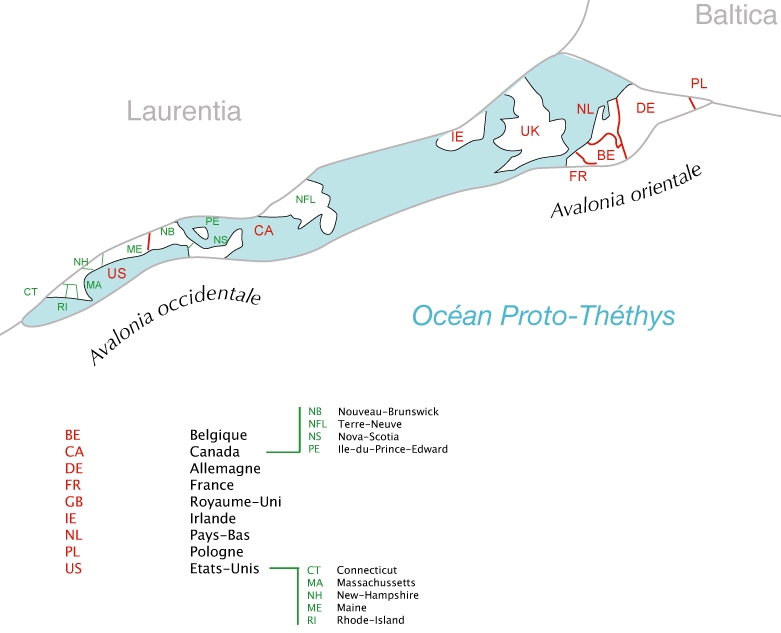

The territory of Ledringhem was part of the microcontinent

The territory of Ledringhem was part of the microcontinent  Ledringhem lies on the

Ledringhem lies on the

The evidences of the last glacial period, alternatively named ''Weichsel glaciation'' or ''Vistulian glaciation'' in Europe, suggest that the ice sheets were at their maximum size for only a short period, between 25,000 to 13,000 BP. During the

The evidences of the last glacial period, alternatively named ''Weichsel glaciation'' or ''Vistulian glaciation'' in Europe, suggest that the ice sheets were at their maximum size for only a short period, between 25,000 to 13,000 BP. During the

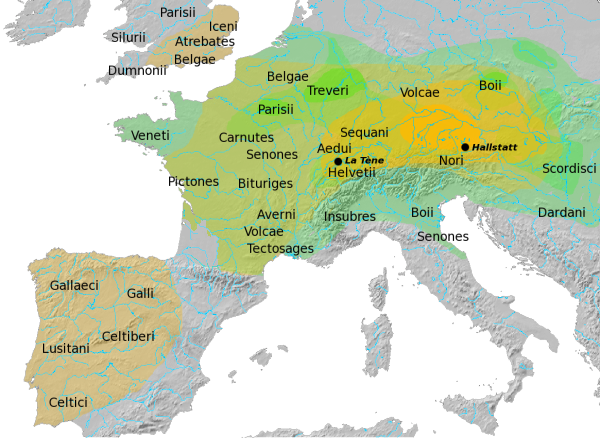

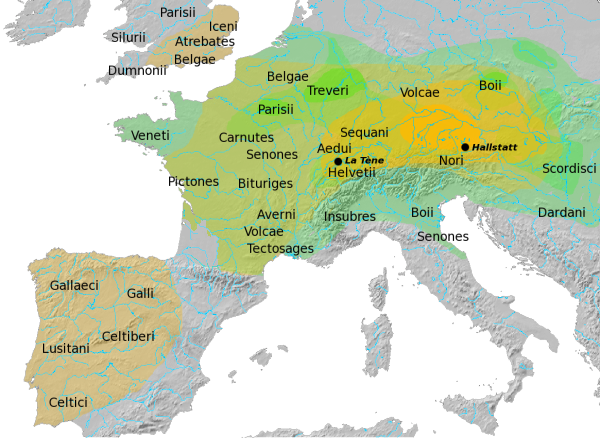

The territory of Northern France is part of the areas of influence of the

The territory of Northern France is part of the areas of influence of the

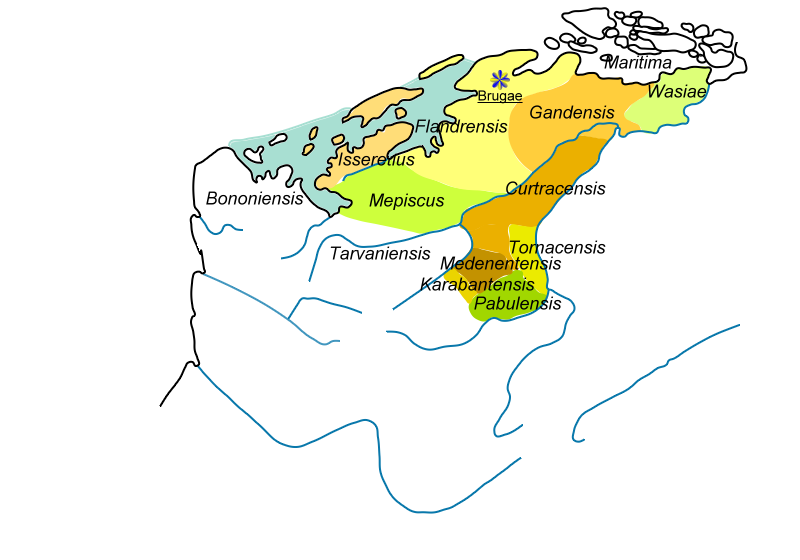

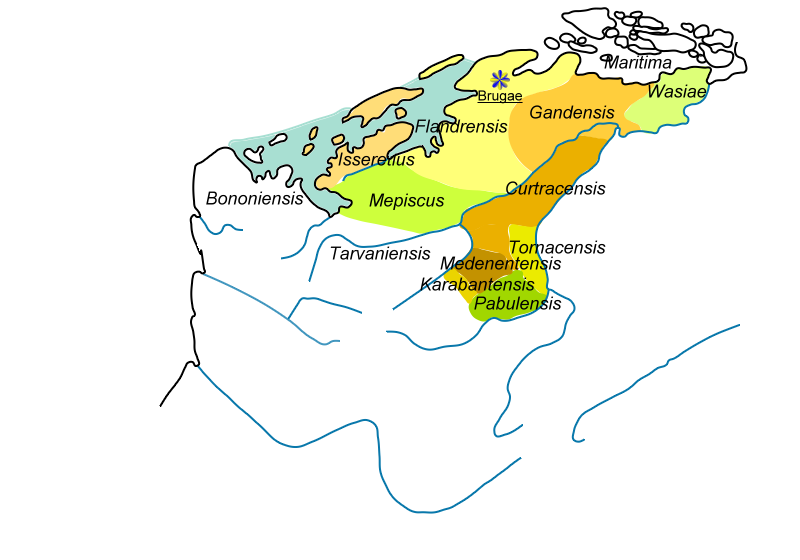

The village could have been occupied since Gaulish times. At that time, the village territory was dry land (or moorland), unlike other territories which were underwater in the "plaine maritime" (see the three

The village could have been occupied since Gaulish times. At that time, the village territory was dry land (or moorland), unlike other territories which were underwater in the "plaine maritime" (see the three

The

The

In Gaul, the

In Gaul, the

During the Middle Ages, Ledringhem was one of the 6 fiefs in the

During the Middle Ages, Ledringhem was one of the 6 fiefs in the

During the Dutch Reformation ''

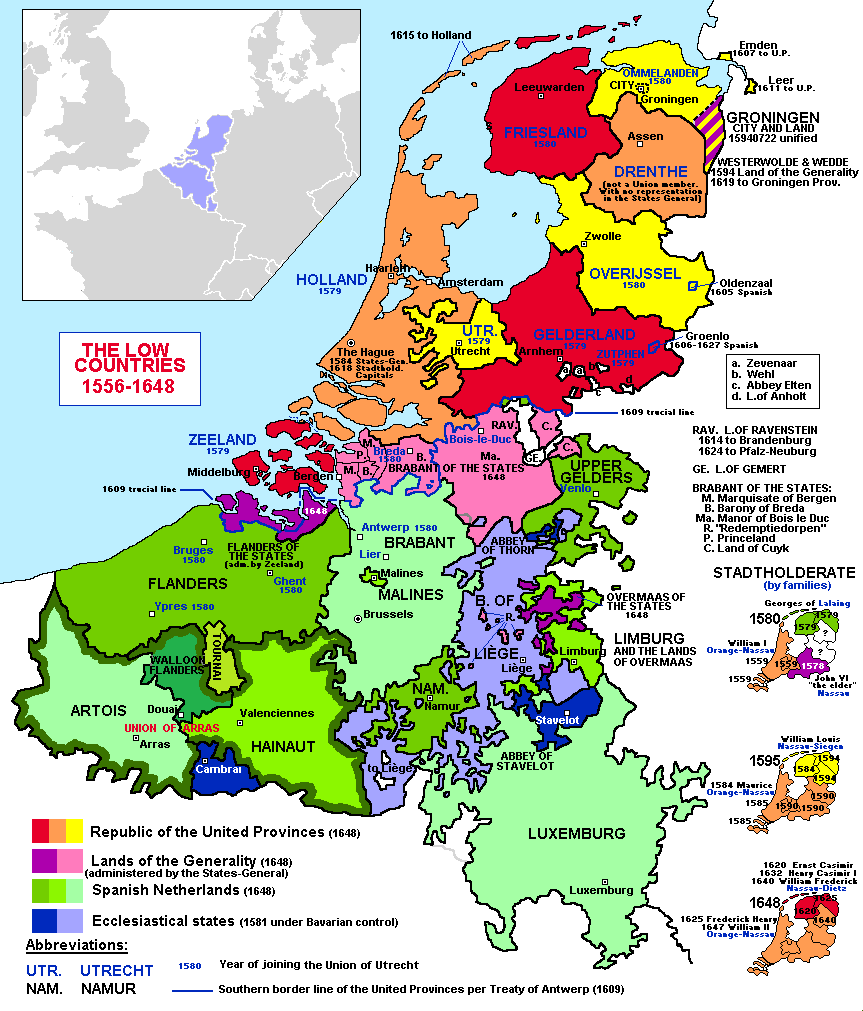

During the Dutch Reformation '' Ledringhem was part of

Ledringhem was part of

In 1794 the entire region of the Spanish/Austrian Netherlands was overrun by France ending the existence of this territory as such. This was resisted by the Flamingant movement organized by Roman Catholic clergy. Austria confirmed the loss of its territories by the

Ledringhem became part of the

Ledringhem became part of the

at fr.geneawiki.com (French) * Gabriel Deblock (1935 in Ledringhem-2006), son of Roger, député of Nord from 1993 to 1997

There is a municipal school (Ecole "Les boutons d'Or – Butter Bloeme") in Ledringhem, a multi-sport stadium and a feasting hall (''salle des fêtes'').

There is ''le Trou Flamand''

There is a municipal school (Ecole "Les boutons d'Or – Butter Bloeme") in Ledringhem, a multi-sport stadium and a feasting hall (''salle des fêtes'').

There is ''le Trou Flamand''

* ''Paeltronck Hoeve'' (French : ''ferme du têtard borne'') is a typical Flemish farm.

;Religious patrimony

* The catholic Hall church-type "hallekerque", with three same-sized naves, is dedicated to

* ''Paeltronck Hoeve'' (French : ''ferme du têtard borne'') is a typical Flemish farm.

;Religious patrimony

* The catholic Hall church-type "hallekerque", with three same-sized naves, is dedicated to Les symboles dits runiques en Flandre on Westhoekpedia

(French) The roof and bell tower are covered with

File:LEDRINGHEM chevet de l'église ST OMER.jpg, Front view of the church with its double

Ledringem's natural catastophy risks assessment on prim.net

(French)

Ledringhem's news on lavoixdunord.fr

(French)

(French)

(French) ; Photographs

(French)

Photographs of Ledringhem on Le Masquelour's blogger site

(French)

Photographs of Ledringhem on www.picturefrance.fr

(French) {{Authority control Communes of Nord (French department) Treasure troves of France Treasure troves of late antiquity French Flanders

commune

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. Commune or comună or comune or other derivations may also refer to:

Administrative-territorial entities

* Commune (administrative division), a municipality or township

** Communes of ...

in the Nord

Nord, a word meaning "north" in several European languages, may refer to:

Acronyms

* National Organization for Rare Disorders, an American nonprofit organization

* New Orleans Recreation Department, New Orleans, Louisiana, US

Film and televisi ...

department

Department may refer to:

* Departmentalization, division of a larger organization into parts with specific responsibility

Government and military

*Department (administrative division), a geographical and administrative division within a country, ...

in northern France.

It is situated also in the ancient territory of the County of Flanders

The County of Flanders was a historic territory in the Low Countries.

From 862 onwards, the counts of Flanders were among the original twelve peers of the Kingdom of France. For centuries, their estates around the cities of Ghent, Bruges and Y ...

, in the '' Houtland'' (or ''woodland'', with the cities of Cassel Cassel may refer to:

People

* Cassel (surname)

Places

;France

* Cassel, Nord, a town and commune in northern France

** Battle of Cassel (1071)

** Battle of Cassel (1328)

** Battle of Cassel (1677)

;Germany

* Cassel, Germany, a city in Hesse rena ...

and Hazebrouck) in the ''Franse Westhoek'' (''French Western corner'') where French Flemish

French Flemish (French Flemish: , Standard Dutch: , french: flamand français) is a West Flemish dialect spoken in the north of contemporary France. Place names attest to Flemish having been spoken since the 8th century in the part of Flan ...

was still spoken until recently.

The residents of Ledringhem are called in French ''Ledringhemois''.

Geography

Cassel Cassel may refer to:

People

* Cassel (surname)

Places

;France

* Cassel, Nord, a town and commune in northern France

** Battle of Cassel (1071)

** Battle of Cassel (1328)

** Battle of Cassel (1677)

;Germany

* Cassel, Germany, a city in Hesse rena ...

. Bigger cities are Dunkirk further to the north and Hazebrouck further to the south.

Ledringhem is crossed by the small river Peene Becque

The Peene Becque (West Flemish: Penebeke) is a small river in the Nord department in France. It is long. The word ''Peene'' may be related to the modern Dutch word ''Peen'' that refers to the wild carrot plant (''Daucus carota''), while ''becque ...

, a tributary of the Franco-Belgian river Yser and there is one shorter tributary, the ''Lyncke Becque'', passing closer to the village center. Other small rivers are ''Trommels Becque'', ''Putte Becque'', ''Platse Becque'' and ''Kaliszewski Becque''.

The climate in Ledringhem is oceanic with a mild summer ( Köppen Classification : Cfb).

Village limits

The river Peene Becque constitutes the southern border between Ledringhem and

The river Peene Becque constitutes the southern border between Ledringhem and Arnèke

Arnèke (; vls, label=French Flemish, Arnyke; nl, Arneke) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

Geography

Arnèke is situated on the D55 (''route de Wormhout''). The small river Peene Becque is flowing through the village. T ...

and Zermezeele

Zermezeele (; nl, Zermezele) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

The northern border between Ledringhem and Zermezeele is marked by the river Peene Becque.

Population

Heraldry

See also

*Communes of the Nord department ...

. It is also the South-Eastern limit with Wormhout until the limit crosses a field between ''rue des postes'' and ''rue de la Forgé''. The North-Eastern limit with Wormhout is ''rue Louis Patoor''. The village Western limit with Arnèke

Arnèke (; vls, label=French Flemish, Arnyke; nl, Arneke) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

Geography

Arnèke is situated on the D55 (''route de Wormhout''). The small river Peene Becque is flowing through the village. T ...

is ''Voie romaine'' (D52). The Northern limit with Esquelbecq

Esquelbecq (; from ) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

Its southern limit with Ledringhem is ''chemin de Rubrouck''.

Heraldry

History

In 1436, Wautier de Ghistelles was ''seigneur d'Ekelsbeke et de Ledringhem'' (Lord ...

is ''chemin de Rubrouck''.

Place-names

The village center consists of the main square (''La Place''), the church, the cemetery, the town's hall and the village park, forming an islet nested in a large turn of the ''route de Wormhout''. There are two subdivisions: * ''La campagnarde'' is a more modern part of the village in comparison with the rest of the built patrimony, situated in the west. * Another modern neighborough dating 2005 is situated at the former place of the village windmill, destroyed during World War II, at the east. The newly built road serving this neighborhood is called ''route du moulin'' (wind mill road). Other locations ('' Lieux-dits'') are called ''Bas de la Plaine'', ''La Belette'', ''La Butte'', ''La Motte'', ''La Plaine'', ''La Potence'', ''Le Baron'', ''Les Grenouilles'', ''Les Tambours'', ''Oost Houck'' (coin de l'Est), ''Planckeel'' (Planckael), ''Sainte Anne'', ''Tampon court'' and ''Zinkepit''. Ledringhem is situated on the D55 road (actually called ''route de Wormhout'' towards Wormhout in the North-East direction and ''route d'Arnèke

Arnèke (; vls, label=French Flemish, Arnyke; nl, Arneke) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

Geography

Arnèke is situated on the D55 (''route de Wormhout''). The small river Peene Becque is flowing through the village. T ...

'' in the West direction).

Other smaller roads include ''rue Henri Wallaert'', ''chemin d'

Esquelbecq

Esquelbecq (; from ) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

Its southern limit with Ledringhem is ''chemin de Rubrouck''.

Heraldry

History

In 1436, Wautier de Ghistelles was ''seigneur d'Ekelsbeke et de Ledringhem'' (Lord ...

'', ''petit chemin d'Esquelbecq'' (north directions), ''chemin de Bodeye'', ''chemin de la chapelle'', ''chemin de la pâture grasse'', ''chemin de Steenvoorde'', ''chemin des postes'', ''chemin des prairies'', ''chemin d'Heenhout'', ''chemin du moulin'', ''chemin du tétard borne'' and ''voie nouvelle''.

The village is a little off the ancient Roman road, now D52, roughly North-South in direction.

Heraldry

Toponymy

First appearances in texts

*The place-name is first mentioned ''Leodringas'' in 723 : "''Leodringas'' mansiones infra Mempisco" in the Latincartulary

A cartulary or chartulary (; Latin: ''cartularium'' or ''chartularium''), also called ''pancarta'' or ''codex diplomaticus'', is a medieval manuscript volume or roll ('' rotulus'') containing transcriptions of original documents relating to the f ...

of St Bertin's whose first part is credited to St Folquin. This text relates a sale act written in 723 where the names given are ''Leodringas mansiones'' or ''Leodringae mansiones''. It is thought that Leodringas is a Latin form of ''Ledring'' while mansiones were official stopping places on a Roman road and ''Mempisco'' refers to the Pagus Mempiscus, an administrative subdivision in the territory of the Flanders at the time. In this sale act, the owner, who is described as having a considerable wealth, was named Rigobert, whereas the buyer was Sitdiu's (Saint-Omer) abbot.

*''Ledringehem'' ar. 1090

*''Lidringhere'' in 1207 (titre de l'abbaye de Blandecques ir.,

*''Ledringhien'' in 1330 (''manuscrit de la bataille de Cassel'')Henri Pirenne (ed.''Le soulèvement de la Flandre maritime de 1323–1328''

(1900), p. 125. On gallica.bnf.fr (French) *''Leodredingas'' in 1614–1616 by Ferry de Locre (Ferreolus Locrius) in p. 86 of his ''Chronicum belgicum'' (''Chronicon belgicum, ab anno CCLVIII ad annum usque M.D.C. continuo perductum.'') Atrecht (Arras), a work published posthumously by his father Philippus Locrius

*''Leregem'' in 1609 (

*''Leregem'' in 1609 (Matthias Quad

Matthias Quad (1557–1613) was an engraver and cartographer from Cologne. He was the first European mapmaker to use dotted lines to indicate international borders.Helmut Walser Smith, ''The Continuities of German History'' (Cambridge Univer ...

's map ''Flandriae Descriptio'')

*''Leodringas'' in 1639 (Jacques Malbrancq Jacques Malbrancq or Malbrancque, also known as ''Jacobus Malbrancq'' or ''Jacobi Malbrancq'' (born circa 1579 in Saint-Omer - died in 1653 in Tournai, in what is now Belgium), Father, ''Audomarensis, e Societate Jesu'', was a Jesuit priest in the S ...

's ''De Morinis et Morinorum rebus, sylvis, paludibus, oppidis, regia comitum prosapia ac territoriis'', Tomus Primus, ab anno ante Christum 309 ad annum eiusdem 751, Tornaci Nerviorum, 1639)

*''Leregem'' in 1645 (Joan Blaeu

Joan Blaeu (; 23 September 1596 – 21 December 1673) was a Dutch cartographer born in Alkmaar, the son of cartographer Willem Blaeu.

Life

In 1620, Blaeu became a doctor of law but he joined the work of his father. In 1635, they published ...

's map ''Artesia Comitatus Artois'')

*''Ledrenghem'' in 1757 (14th sheet of Cassini's map, the village is pictured as a parish with a wooden wind mill)

Etymology

An ancient and legendary explanation is that the name comes from the Latin form (''Ledera'') of the name of a local brook called the ''Leder''. This explanation, given in tome II, page 572 ofFlandria Illustrata

''Flandria Illustrata'' is a historiographical and topographical work from 1641 by the Flemish canon Antonius Sanderus. It contains historical descriptions of the main towns and villages of the former County of Flanders, in addition to the lives ...

(1641), and though doubtful, is also provided for the name of nearby village Lederzeele. It comes from Sanderus

Antonius Sanderus (Antwerp, 15 September 1586 – Affligem, 10 January 1664) was a Flemish Catholic cleric and historian.

Biography

Sanderus was born "Antoon Sanders", but like all writers and scholars of his time he Latinized his name. Having ...

(1586–1664) who wrote, citing Malbrancq: ''Lederam pluribus ab ortu suo pagis nomem communicantem'' (The Leder was the source of many country names).Annales de la Société d'émulation de Bruges, Volume 10, 1848, pages 68–69(French)Les Flamands de France: Études sur leur langue, leur littérature et leurs Monuments, Louis de Baecker, 1830, page 40

(French) In reality, the place-name Ledringhem is typical Germanic, with the common Germanic double end ''-ing-hem'' (name suffix + toponymic appellative) found everywhere in Flanders, corresponding exactly to the English one ''-ing-ham'' (e. g. Nottingham). This ''-ing-hem'' turned into ''-egem'' where Flemish-Dutch continued to be spoken, but remained the same ''-ing-hem'' where the Picard language replaced the Flemish one in the Middle Ages. The French language has retained the old version, and often frenchified it as ''-eng-hien'' or ''-ing-hien'' (see above ''Ledringhien'' in 1330, similar to

Enghien

Enghien (; nl, Edingen ; pcd, Inguî; vls, Enge) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium.

On 1January 2006, Enghien had a total population of 11,980. The total area is , which gives a population den ...

for instance) but the existence of the evoluted Dutch form is attested : ''Ledregem'' in the 17th century.

The only problem that divides the specialists (the "toponymists") is the right identification of the personal name (male's name) contained in this place-name.

The current name Ledringhem could be of Frankish origin, with the ''-hem'' particle meaning "home" and ''Ledring-'' being the genitive form of ''Leodro'', a common given name at the time, who could have been a local chief. ''Hem'' is the same word as Old English ''hām'' (home), the Old Low Franconian

In linguistics, Old Dutch (Dutch: Oudnederlands) or Old Low Franconian (Dutch: Oudnederfrankisch) is the set of Franconian dialects (i.e. dialects that evolved from Frankish) spoken in the Low Countries during the Early Middle Ages, from arou ...

form would have been ''*haim''.

Another explanation for the name etymology is the Old Low Franconian ''*Liuthari-ing-haim'' "home of Luithari's people".

Ernest Nègre

Ernest Angély Séraphin Nègre (, born 11 October 1907 in Saint-Julien-Gaulène (Tarn), died 15 April 2000 in Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occit ...

notices that the Germanic ''-heim'' (sic) is precisely rendered by the Latin ''mansiones'' in the earliest document. He hesitates about the personal name contained in this place-name, but believes that it is probably ''Liutradus'' instead of ''Liuthari'' supported by Marie-Thérèse Morlet, after Albert Dauzat

Albert Dauzat (; 4 July 1877 – 31 October 1955) was a French linguist specializing in toponymy and onomastics.

Dauzat, a student of Jules Gilliéron, was a director of studies at the École des hautes études.

Works

* ''L'argot des poilus; ...

and Charles Rostaing

Charles Rostaing (9 October 1904 – 24 April 1999) was a French linguist who specialised in toponymy.Obituar ...

.

The Anglo-Saxon history specialist Daniel Henry Haigh

Daniel Henry Haigh (7 August 1819 — 10 May 1879) was a noted Victorian scholar of Anglo-Saxon history and literature, as well as a runologist and numismatist.

Biography

Haigh was born 7 August 1819 at Brinscall Hall in the village of Brinscal ...

(1819—1879) noticed that the village could share a common etymology with the civil parish of Letheringham

Letheringham is a sparsely populated civil parish in the East Suffolk district (formerly Deben Rural District and then Suffolk Coastal) in Suffolk, England, on the Deben River.

St Mary is a tiny church, the remains of the tower and nave of a ...

in Suffolk, England. and this theory of a Saxon or Anglo-Saxon origin is supported nowadays by linguists that analysed toponyms thought before to be Franconian as Saxon afterwards. Numerous archeological sites in the northern part of France along the channel coast show a very strong Saxon and Anglo-Saxon influence in the early Middle Ages.

Geology

Undersurface geology

The territory of Ledringhem was part of the microcontinent

The territory of Ledringhem was part of the microcontinent Avalonia

Avalonia was a microcontinent in the Paleozoic era. Crustal fragments of this former microcontinent underlie south-west Great Britain, southern Ireland, and the eastern coast of North America. It is the source of many of the older rocks of West ...

in the Paleozoic era.

Euramerica

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

, also known as Laurussia, was a landmass created in the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wh ...

as the result of a collision between the Laurentian, Baltica, and Avalonia cratons. Euramerica became a part of the supercontinent Pangaea in the Permian.

In the Jurassic, when Pangaea rifted into two continents, Gondwana and Laurasia, Euramerica was a part of Laurasia.

In the Cretaceous, Laurasia split into the continents of North America and Eurasia. The Laurentian craton became a part of North America while Baltica became a part of Eurasia, and Avalonia was split between the two.

Ledringhem lies on the

Ledringhem lies on the London-Brabant Massif

The London-Brabant Massif or London-Brabant Platform is, in the tectonic structure of Europe, a structural high or massif that stretches from the Rhineland in western Germany across northern Belgium (in the province of Brabant) and the North ...

, a structural high or massif that stretches from the Rhineland in western Germany across northern Belgium (in the province of Brabant) and the North Sea to the sites of East Anglia and the middle Thames in southern England. The London–Brabant Massif is part of the former microcontinent Avalonia. The formation formed an island at some point in geological time. As the island was drifting past the Equator during the Carboniferous, on the shores grew a rich tropical forest swamp.

Superficial geology

Ledringhem is situated in theCenozoic Era

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configu ...

Bassin de Flandre of French regional geology. It is north of the Weald–Artois Anticline

The Weald–Artois Anticline, or Wealden Anticline, is a large anticline, a geological structure running between the regions of the Weald in southern England and Artois in northern France. The fold formed during the Alpine orogeny, from the late ...

.

Prehistory

The evidences of the last glacial period, alternatively named ''Weichsel glaciation'' or ''Vistulian glaciation'' in Europe, suggest that the ice sheets were at their maximum size for only a short period, between 25,000 to 13,000 BP. During the

The evidences of the last glacial period, alternatively named ''Weichsel glaciation'' or ''Vistulian glaciation'' in Europe, suggest that the ice sheets were at their maximum size for only a short period, between 25,000 to 13,000 BP. During the glacial maximum

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gree ...

in Scandinavia, only the western parts of Jutland

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

were ice-free, and a large part of what is today the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

was dry land connecting Jutland with Britain.

Early human settlements

The territory of Northern France is part of the areas of influence of the

The territory of Northern France is part of the areas of influence of the Beaker culture

The Bell Beaker culture, also known as the Bell Beaker complex or Bell Beaker phenomenon, is an archaeological culture named after the inverted-bell beaker drinking vessel used at the very beginning of the European Bronze Age. Arising from a ...

(c. 2800–1800 BC), the Atlantic Bronze Age

The Atlantic Bronze Age is a cultural complex of the Bronze Age period in Prehistoric Europe of approximately 1300–700 BC that includes different cultures in Britain, France, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain.

Trade

The Atlantic Bronze Age ...

(approximately 1300–700 BC), then of the Hallstatt culture

The Hallstatt culture was the predominant Western and Central European culture of Late Bronze Age (Hallstatt A, Hallstatt B) from the 12th to 8th centuries BC and Early Iron Age Europe (Hallstatt C, Hallstatt D) from the 8th to 6th centuries ...

(800 -500 BC) and La Tène culture

The La Tène culture (; ) was a European Iron Age culture. It developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from about 450 BC to the Roman conquest in the 1st century BC), succeeding the early Iron Age Hallstatt culture without any defi ...

(450 BC).

History

The origins of the village are unclear.Gaulish times

The village could have been occupied since Gaulish times. At that time, the village territory was dry land (or moorland), unlike other territories which were underwater in the "plaine maritime" (see the three

The village could have been occupied since Gaulish times. At that time, the village territory was dry land (or moorland), unlike other territories which were underwater in the "plaine maritime" (see the three Dunkirk transgression

The Dunkirk transgressions were tidal bulges or other sea level-related marine transgressions (risings), often heightened by river floods, affecting the North Sea and adjoining low land. Most of this land is vulnerable to such events being below ...

s), a polder region made from Les Moëres, part of French Flanders.

The nearby presence of a Roman road (now voie romaine

Roman roads ( la, viae Romanae ; singular: ; meaning "Roman way") were physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, and were built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman Re ...

– D52) from Cassel and leading to the sea could have been a reason for an early settlement. This road could have preceded the Romans.

;1852 Ledringhem's treasure discovery

As a proof of possible gaulish origins, a hoard

A hoard or "wealth deposit" is an archaeological term for a collection of valuable objects or artifacts, sometimes purposely buried in the ground, in which case it is sometimes also known as a cache. This would usually be with the intention of ...

was discovered in 1852 in Ledringhem. This treasure was estimated by Jérémie Landron (1840–1904), a pharmacist-chemist-''gold-and-silver assayer'', to be composed of 35 000 small gold coins

A coin is a small, flat (usually depending on the country or value), round piece of metal or plastic used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order t ...

, described as stater

The stater (; grc, , , statḗr, weight) was an ancient coin used in various regions of Greece. The term is also used for similar coins, imitating Greek staters, minted elsewhere in ancient Europe.

History

The stater, as a Greek silver curre ...

s, and locally known as Ledringhem's buttons (''boutons de Ledringhem'').

The coins were retrieved in an 18-liter vase, which has been lost, by two workers cleaning a farm cesspit of the Mormentyn farm. Each coin was 18 mm wide and weighed approximately 6 grams.

Half of the coins were reddish in color due to a higher richness in copper in the gold-silver-copper alloy, the remaining coins being yellow-white-colored. They presented an image of a running wild horse on one of the two faces.

It has been hypothesized that this treasure could have been hidden underground and never recovered by its Morini

The Morini (Gaulish: "sea folk, sailors") were a Belgic coastal tribe dwelling in the modern Pas de Calais region, around present-day Boulogne-sur-Mer, during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Name

They are mentioned as ''Morini'' by Caesar ( ...

or Menapian

The Menapii were a Belgic tribe dwelling near the North Sea, around present-day Cassel, during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Name Attestations

They are mentioned as ''Menapii'' by Caesar (mid-1st c. BC) and Orosius (early 5th c. AD), ' ...

owners, during troubled times like during the Gallic Wars

The Gallic Wars were waged between 58 and 50 BC by the Roman general Julius Caesar against the peoples of Gaul (present-day France, Belgium, Germany and Switzerland). Gallic, Germanic, and British tribes fought to defend their homel ...

.

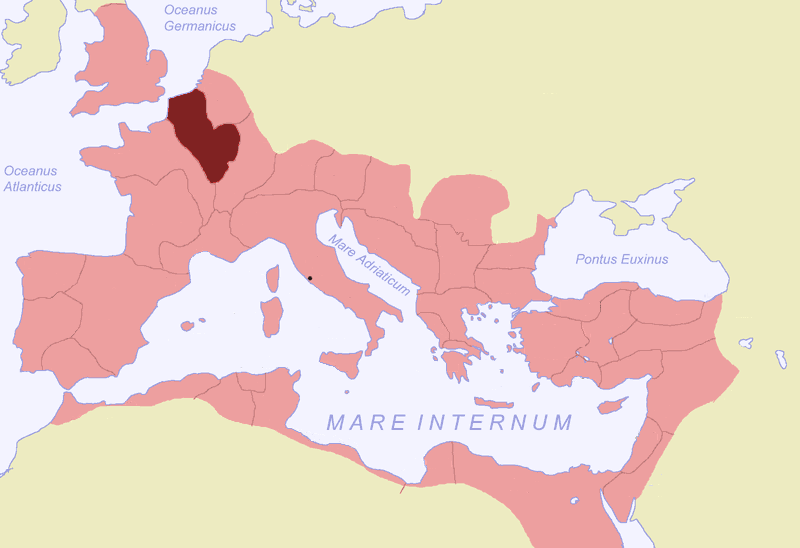

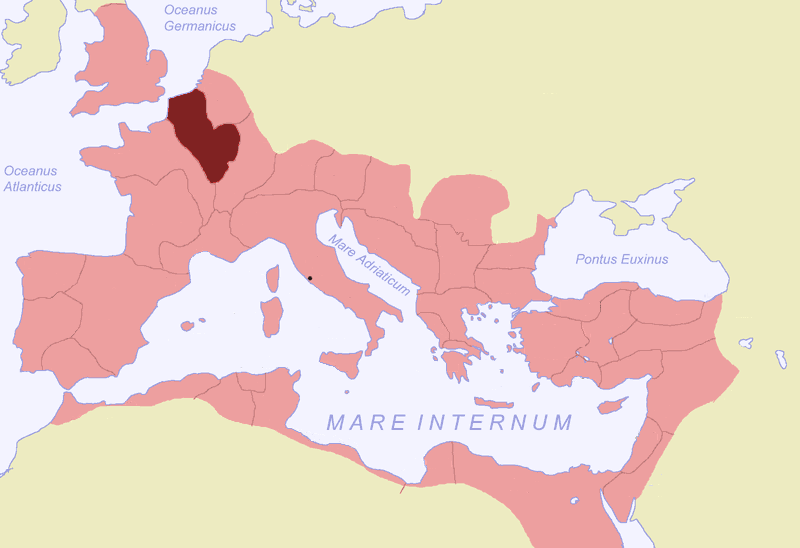

Roman time

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

conquered the Belgae

The Belgae () were a large confederation of tribes living in northern Gaul, between the English Channel, the west bank of the Rhine, and the northern bank of the river Seine, from at least the third century BC. They were discussed in depth by Ju ...

, beginning in 57 BC. He marched into the territory of the Suessiones and besieged the town of Noviodunum (Soissons). Seeing the Romans' siege engines, the Suessiones surrendered, whereupon Caesar turned his attention to the Bellovaci, who had retreated into the fortress of Bratuspantium (between modern Amiens and Beauvais). They quickly surrendered, as did the Ambiani.

The Nervii

The Nervii were one of the most powerful Belgic tribes of northern Gaul at the time of its conquest by Rome. Their territory corresponds to the central part of modern Belgium, including Brussels, and stretched southwards into French Hainault. ...

, along with the Atrebates and Viromandui, decided to fight (the Atuatuci had also agreed to join them but had not yet arrived). They concealed themselves in the forests and attacked the approaching Roman column at the river Sabis (previously thought to be the Sambre but recently the Selle is thought to be more probable). Their attack was quick and unexpected. The element of surprise briefly left the Romans exposed. Some of the Romans did not have time to take the covers off their shields or to even put on their helmets. However Caesar grabbed a shield, made his way to the front line, and quickly organised his forces. The two Roman legions guarding the baggage train at the rear finally arrived and helped to turn the tide of the battle. Caesar says the Nervii were almost annihilated in the battle, and is effusive in his tribute to their bravery, calling them "heroes".

The Atuatuci, who were marching to their aid, turned back on hearing of the defeat and retreated to one stronghold, were put under siege, and soon surrendered and handed over their arms. However the surrender was a ploy, and the Atuatuci, armed with weapons they had hidden, tried to break out during the night. The Romans had the advantage of position and killed four thousand. The rest, about fifty-three thousand, were sold into slavery.

In 53 BC the Eburones, led by Ambiorix, along with the Nervii

The Nervii were one of the most powerful Belgic tribes of northern Gaul at the time of its conquest by Rome. Their territory corresponds to the central part of modern Belgium, including Brussels, and stretched southwards into French Hainault. ...

, Menapii

The Menapii were a Belgic tribe dwelling near the North Sea, around present-day Cassel, during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Name Attestations

They are mentioned as ''Menapii'' by Caesar (mid-1st c. BC) and Orosius (early 5th c. AD ...

and Morini

The Morini (Gaulish: "sea folk, sailors") were a Belgic coastal tribe dwelling in the modern Pas de Calais region, around present-day Boulogne-sur-Mer, during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Name

They are mentioned as ''Morini'' by Caesar ( ...

, revolted again and wiped out 15 cohorts, only to be put down by Caesar.

The Belgae

The Belgae () were a large confederation of tribes living in northern Gaul, between the English Channel, the west bank of the Rhine, and the northern bank of the river Seine, from at least the third century BC. They were discussed in depth by Ju ...

fought in the uprising of Vercingetorix in 52 BC.

The Menapii again rebelled along with their neighbours, the Morini, in 30 or 29 BC. The Roman governor of Gaul, Gaius Carrinas, successfully quelled the rebellion and the territory of the Menapii was subsequently absorbed into the Roman province of Gallia Belgica

Gallia Belgica ("Belgic Gaul") was a province of the Roman Empire located in the north-eastern part of Roman Gaul, in what is today primarily northern France, Belgium, and Luxembourg, along with parts of the Netherlands and Germany.

In 50 BC, a ...

.

After their final subjugation, Caesar combined the three parts of Gaul, the territory of the Belgae, Celtae and Aquitani, into a single unwieldy province (Gallia Comata, "long-haired Gaul") that was reorganized by the emperor Augustus into its traditional cultural divisions. The population was partially Romanised from the 1st to 3rd centuries.

Gallic Empire

The Gallic Empire or the Gallic Roman Empire are names used in modern historiography for a breakaway part of the Roman Empire that functioned ''de facto'' as a separate state from 260 to 274. It originated during the Crisis of the Third Century, ...

(Latin: Imperium Galliarum) is the modern name for a breakaway realm of the Roman Empire that existed from 260 to 274. It originated during the Crisis of the 3rd Century (AD 235–284). It was retaken by Roman Emperor Aurelian

Aurelian ( la, Lucius Domitius Aurelianus; 9 September 214 October 275) was a Roman emperor, who reigned during the Crisis of the Third Century, from 270 to 275. As emperor, he won an unprecedented series of military victories which reunited ...

after the Battle of Châlons

The Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (or Fields), also called the Battle of the Campus Mauriacus, Battle of Châlons, Battle of Troyes or the Battle of Maurica, took place on June 20, 451 AD, between a coalition – led by the Roman general ...

in 274.

Constantius Chlorus

Flavius Valerius Constantius "Chlorus" ( – 25 July 306), also called Constantius I, was Roman emperor from 305 to 306. He was one of the four original members of the Tetrarchy established by Diocletian, first serving as caesar from 293 ...

’ first task on becoming Caesar was to deal with the Roman usurper

Roman usurpers were individuals or groups of individuals who obtained or tried to obtain power by force and without legitimate legal authority. Usurpation was endemic during the Roman imperial era, especially from the crisis of the third cent ...

Carausius

Marcus Aurelius Mausaeus Carausius (died 293) was a military commander of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century. He was a Menapian from Belgic Gaul, who usurped power in 286, during the Carausian Revolt, declaring himself emperor in Britain and ...

who had declared himself emperor in Britannia and northern Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

in 286. In late 293, Constantius defeated the forces of Carausius in Gaul, capturing Bononia (Boulogne-sur-Mer

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Hauts-de-France, Northern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Department ...

). This precipitated the assassination of Carausius by his '' rationalis'' Allectus

Allectus (died 296) was a Roman-Britannic usurper-emperor in Britain and northern Gaul from 293 to 296.

History

Allectus was treasurer to Carausius, a Menapian officer in the Roman navy who had seized power in Britain and northern Gaul in 286. I ...

, who assumed command of the British provinces until his death in 296. Constantius spent the next two years neutralising the threat of the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools ...

who were the allies of Allectus, as northern Gaul remained under the control of the British usurper until at least 295.

Later Emperor Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

restructured the provinces around 300, and split Belgica into two provinces: Belgica Prima and Belgica Secunda. Belgica Prima had Treveri (Trier) as its main city, and consisted of the eastern part. Belgica Secunda was situated between the English channel and the River Meuse, which therefore contained the original "Belgium" that Caesar had described. Reims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded b ...

(Durocortorum) was the capital of that second province.

The Saxon Shore

The Saxon Shore ( la, litus Saxonicum) was a military command of the late Roman Empire, consisting of a series of fortifications on both sides of the Channel. It was established in the late 3rd century and was led by the " Count of the Saxon Sh ...

(Latin: litus Saxonicum) was a military command of the late Roman Empire, established during the Crisis of the 3rd Century and consisted of a series of fortifications on both sides of the English channel. It was established in the late 3rd century and was led by the "Count of the Saxon Shore". In the late 4th century, his functions were limited to Britain, while the fortifications in Gaul were established as separate commands, dux tractus Amoricani and dux Belgicae Secundae, with headquarters at Portus Aepatiaci (possibly Étaples).

Frankish Empire

Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools ...

, a fusion of western Germanic tribes whose leaders had been strongly aligned with Rome since the 3rd century, subsequently entered Roman lands more gradually and peacefully during the 5th century, and were generally endured as rulers by the Roman-Gaulish population.

The Franks became foederati

''Foederati'' (, singular: ''foederatus'' ) were peoples and cities bound by a treaty, known as ''foedus'', with Rome. During the Roman Republic, the term identified the ''socii'', but during the Roman Empire, it was used to describe foreign stat ...

in 358 AD, when Emperor Julian let them keep the areas in northern Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

, which had been depopulated during the preceding century. Roman soldiers defended the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

and had major armies 100 miles (160 km) south and west of the Rhine. Frankish settlers were established in the areas north and east of the Romans and helped with the Roman defense by providing intelligence and a buffer state. The breach of the Rhine borders in the frozen winter of 406 and 407 made an end to the Roman presence at the Rhine when both the Romans and the allied Franks were overrun by a tribal migration ''en masse'' of Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

and Alans

The Alans (Latin: ''Alani'') were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the A ...

.

They emerged victorious and Belgica Secunda became in the 5th century the center of Clovis' Merovingian

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the Franks and northern Gaul ...

kingdom and during the 8th century the heart of the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the L ...

.

The current territory of the village of Ledringhem became part of Francia

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks du ...

, the territory held by Franks, in 481. It became part of West Francia

In medieval history, West Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the West Franks () refers to the western part of the Frankish Empire established by Charlemagne. It represents the earliest stage of the Kingdom of France, lasting from ab ...

in 843, and more accurately part of Neustria

Neustria was the western part of the Kingdom of the Franks.

Neustria included the land between the Loire and the Silva Carbonaria, approximately the north of present-day France, with Paris, Orléans, Tours, Soissons as its main cities. It late ...

.

From 830 until around 910, the Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

s invaded Flanders. After the destruction caused by Norman and Magyar invasion, the eastern part of the region fell under the eyes of the area's princes.

In 962, Baldwin III, Count of Flanders

Baldwin III (–962), called the Young, was Count of Flanders, who briefly ruled the County of Flanders together with his father, Arnulf I, from 958 until his early death.

Baldwin III was born . He was the son of Count Arnulf I of Flanders and ...

, son, co-ruler, and heir of Arnulf I died and Arnulf bequeathed Flanders to Lothair of France

Lothair (french: Lothaire; la, Lothārius; 941 – 2 March 986), sometimes called Lothair II,After the emperor Lothair I. IIICounting Lothair II of Lotharingia, who ruled over modern Lorraine and Belgium. or IV,Counting Lothair II of Ita ...

. On Arnulf's death in 965, Lothair invaded Flanders and took many cities, but was eventually repulsed by the supporters of Arnulf II. He temporarily remained in control of Arras

Arras ( , ; pcd, Aro; historical nl, Atrecht ) is the prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais department, which forms part of the region of Hauts-de-France; before the reorganization of 2014 it was in Nord-Pas-de-Calais. The historic centre of ...

and Douai

Douai (, , ,; pcd, Doï; nl, Dowaai; formerly spelled Douay or Doway in English) is a city in the Nord département in northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department. Located on the river Scarpe some from Lille and from Arras, Dou ...

.

Old Dutch

In linguistics, Old Dutch (Dutch: Oudnederlands) or Old Low Franconian (Dutch: Oudnederfrankisch) is the set of Franconian dialects (i.e. dialects that evolved from Frankish) spoken in the Low Countries during the Early Middle Ages, from aro ...

was the Frankish dialects spoken and written in the Low Countries during the Early Middle Ages. It evolved from Old Frankish

Frankish ( reconstructed endonym: *), also known as Old Franconian or Old Frankish, was the West Germanic language spoken by the Franks from the 5th to 9th century.

After the Salian Franks settled in Roman Gaul, its speakers in Picardy ...

around the 6th century and in turn evolved into Middle Dutch

Middle Dutch is a collective name for a number of closely related West Germanic dialects whose ancestor was Old Dutch. It was spoken and written between 1150 and 1500. Until the advent of Modern Dutch after 1500 or c. 1550, there was no overarc ...

around the 12th century.

Middle Ages

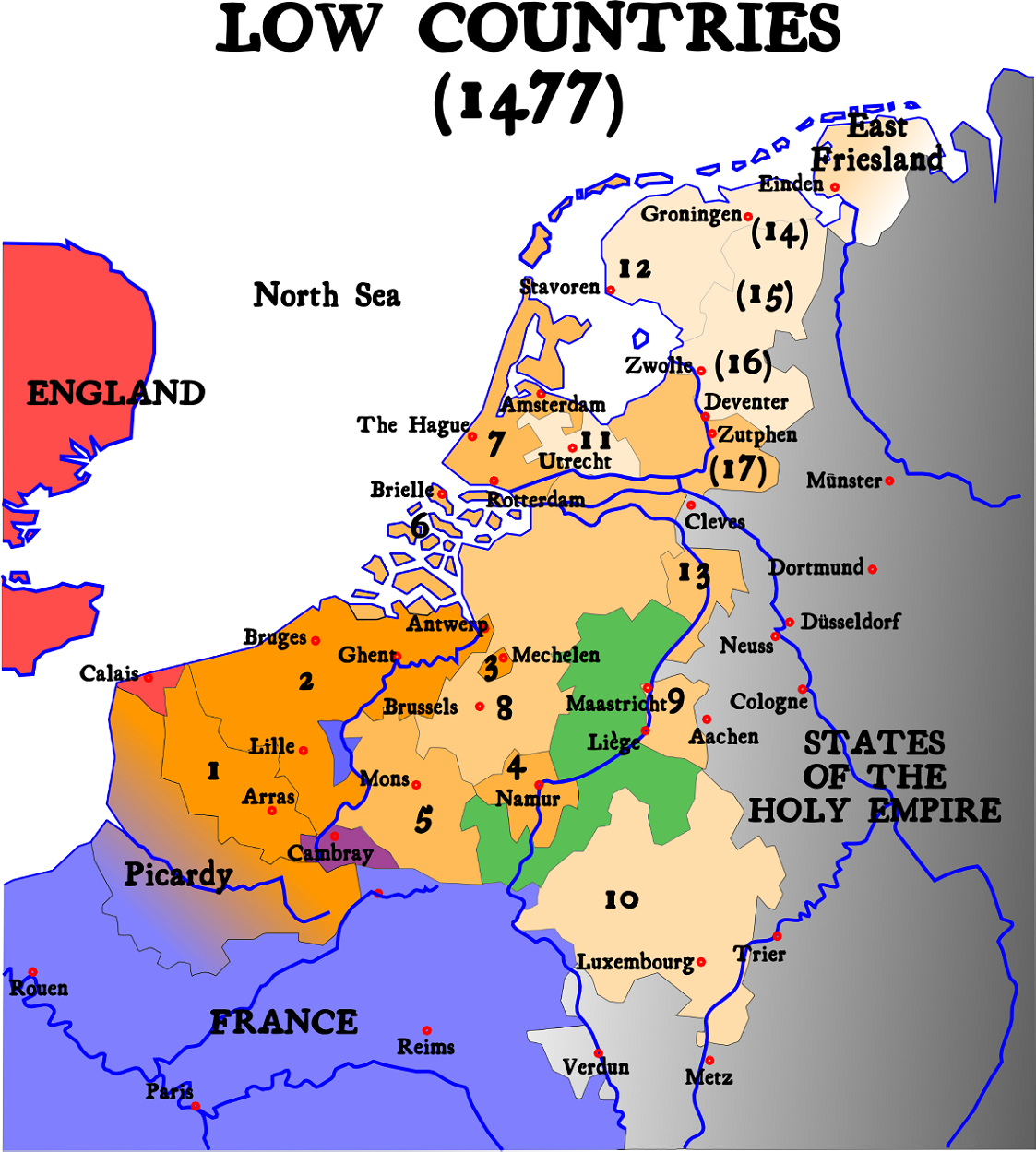

During the Middle Ages, Ledringhem was one of the 6 fiefs in the

During the Middle Ages, Ledringhem was one of the 6 fiefs in the Bergues

Bergues (; nl, Sint-Winoksbergen; vls, Bergn) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

It is situated to the south of Dunkirk and from the Belgian border. Locally it is referred to as "the other Bruges in Flanders". Bergues ...

fiefdom, composed out of 24 villages. under the jurisdiction of Counts of Flandres. Esquelbecques and Ledringhem were parts of the same fief, but both villages had their own town magistrates.

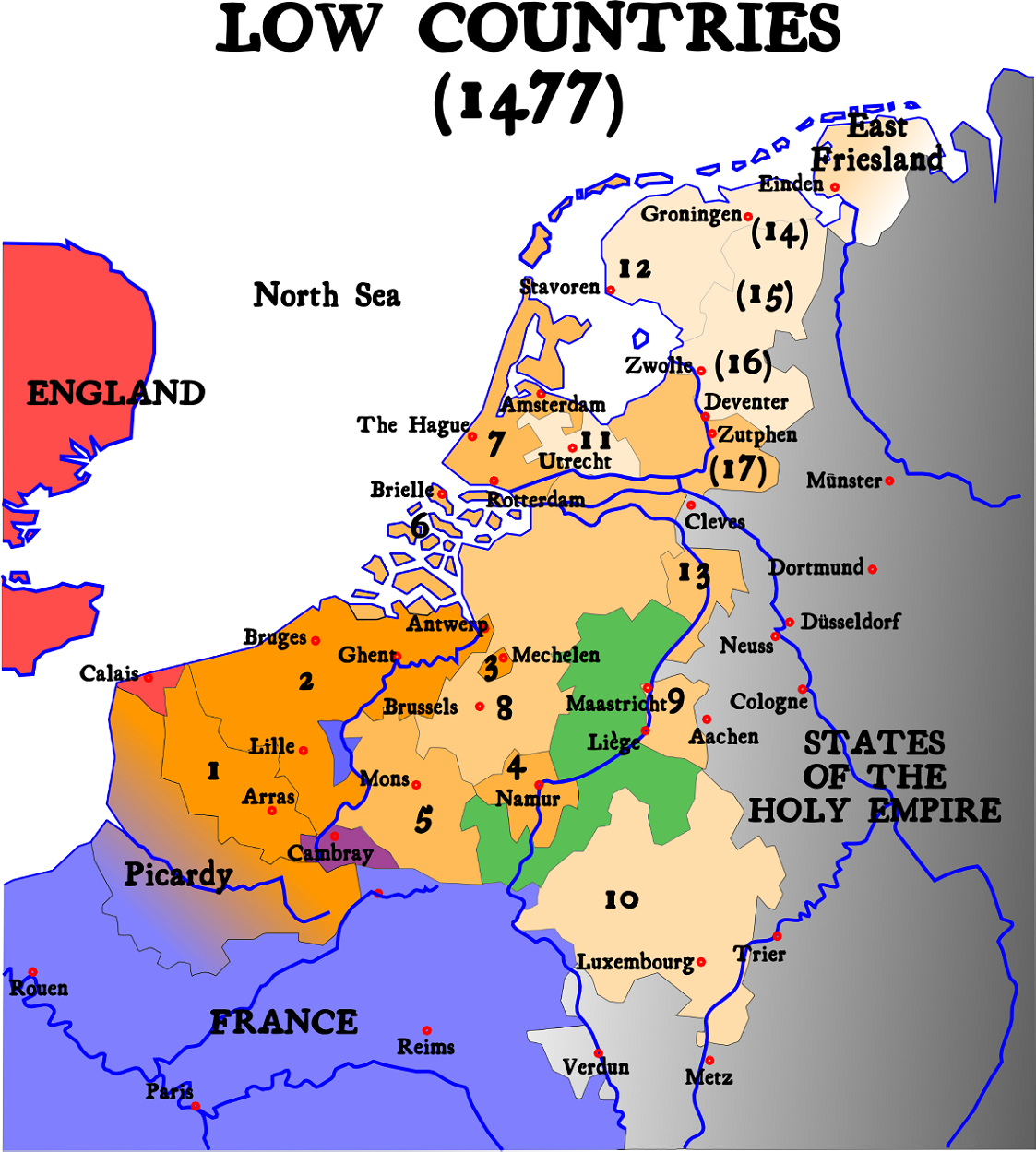

The County of Flanders

The County of Flanders was a historic territory in the Low Countries.

From 862 onwards, the counts of Flanders were among the original twelve peers of the Kingdom of France. For centuries, their estates around the cities of Ghent, Bruges and Y ...

was one of the territories constituting the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

. The county existed from 862 to 1795. It was one of the original secular fiefs of France and for centuries was one of the most affluent regions in Europe.

From 1323 to 1328 people from Ledringhem took part to the peasant revolt in Flanders and five of them died in 1328 during the Battle of Cassel.

In 1436, Wautier de Ghistelles was ''seigneur d'Ekelsbeke et de Ledringhem'' (Lord of Esquelbecq and Ledringhem) and governor of ''La Madeleine'' hospital in Bierne

Bierne (; vls, label=French Flemish, Bieren) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

History

In 1436, Wautier de Ghistelles was ''seigneur d'Ekelsbeke et de Ledringhem'' (Lord of Esquelbecq and Ledringhem) and governor of ''L ...

.

English rule over Northern France

On 21 May 1420, theTreaty of Troyes

The Treaty of Troyes was an agreement that King Henry V of England and his heirs would inherit the French throne upon the death of King Charles VI of France. It was formally signed in the French city of Troyes on 21 May 1420 in the aftermath of ...

is signed. With the Burgundian faction dominant in France, King Charles VI of France

Charles VI (3 December 136821 October 1422), nicknamed the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé) and later the Mad (french: le Fol or ''le Fou''), was King of France from 1380 until his death in 1422. He is known for his mental illness and psychotic ...

acknowledges Henry V of England

Henry V (16 September 1386 – 31 August 1422), also called Henry of Monmouth, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1413 until his death in 1422. Despite his relatively short reign, Henry's outstanding military successes in the ...

as his heir and as virtual ruler of most of France.

Charles VII of France

Charles VII (22 February 1403 – 22 July 1461), called the Victorious (french: le Victorieux) or the Well-Served (), was King of France from 1422 to his death in 1461.

In the midst of the Hundred Years' War, Charles VII inherited the throne of F ...

and Philip the Good

Philip III (french: Philippe le Bon; nl, Filips de Goede; 31 July 1396 – 15 June 1467) was Duke of Burgundy from 1419 until his death. He was a member of a cadet line of the Valois dynasty, to which all 15th-century kings of France belonge ...

, Duke of Burgundy, then signed the 1435 Treaty of Arras, which allowed the Burgundians to return to the side of the French just as things were going badly for their English allies. With this accomplishment, Charles attained the essential goal of ensuring that no Prince of the Blood recognised Henry VI as King of France. Over the following two decades, the French recaptured Paris from the English and eventually recovered all of France with the exception of the northern port of Calais and the Channel Islands.

Habsburg Netherlands

Ledringhem was part of theHabsburg Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands was the Renaissance period fiefs in the Low Countries held by the Holy Roman Empire's House of Habsburg. The rule began in 1482, when the last Valois-Burgundy ruler of the Netherlands, Mary, wife of Maximilian I of Austr ...

(1526 to 1556/1581).

On 14 January 1526, the Treaty of Madrid is signed. Peace is declared between Francis I of France

Francis I (french: François Ier; frm, Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin on ...

and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) fr ...

. Francis agrees to cede Burgundy to Charles, and abandons all claims to Flanders, Artois, Naples and Milan.

Spanish Netherlands period and Dutch Reformation

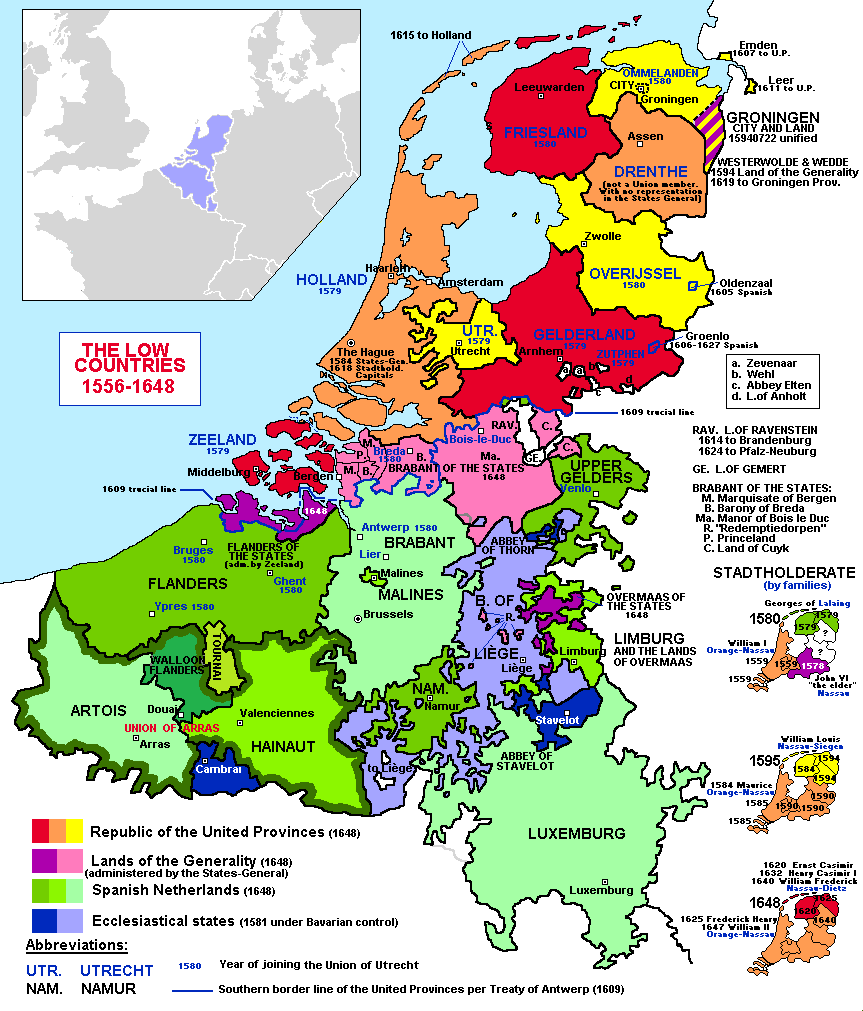

During the Dutch Reformation ''

During the Dutch Reformation ''Beeldenstorm

''Beeldenstorm'' () in Dutch and ''Bildersturm'' in German (roughly translatable from both languages as 'attack on the images or statues') are terms used for outbreaks of destruction of religious images that occurred in Europe in the 16th centu ...

'' iconoclasm movement, an episode took place in Ledringhem on Friday 16 August 1566. A depiction of the events is given in:

Jan de Druck was a busy iconoclast. He participated in attacks in Broxeele, Eecke, North and South Berkijn, and Ledringhem, for which he was condemned to death on october 28, 1567, by Alba's special law court, theAs Spain was fighting back Reformation, a war developed leading to the formation of a Dutch protestant independent state and the Southern part of the territory still loyal to Catholicism and Spanish power. As thiscouncil of Troubles The Council of Troubles (usual English translation of nl, Raad van Beroerten, or es, Tribunal de los Tumultos, or french: Conseil des Troubles) was the special tribunal instituted on 9 September 1567 by Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of .... His crimes centered on destruction of religious art and objects in parish churches in mid-August 1566: ... He also ransacked several altars at Ledringhem, stealing money amounting to 3 or 4 Parisian pounds and intended "for common devotion." ... Druck's deeds mirror those of other individuals and small groups; at Ledringhem, on September 10, a crowd of about thirty-two seized the priest's house, eating and drinking heartily before they settled down for the night there. Refreshed, the next morning they sacked the local parish church, destroying four altars. They scattered for the balance of the day, some going to Ekelsbeke, other to Arnèke, both sets listening to sermons, only to return at nightfall, this time to the chaplain's house,where they had something to eat and pocketed four candles. Afterward, they randomly searched private houses looking for objects the churchwardens might have hidden, or domestic altars or shrines. The next morning, they continued their efforts, overturning basins of holy oil, smashing up more altars, and shredding the priest's and chaplains's books. As a parting shot, they derisively cut up the chaplain's bonnet.

eighty years war

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) ( c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Ref ...

developed, raids against cities and villages occurred. The church of Ledringhem was burnt by orangists during this period. It took several decades for the population to reconstruct it.

Ledringhem was part of

Ledringhem was part of Southern Netherlands

The Southern Netherlands, also called the Catholic Netherlands, were the parts of the Low Countries belonging to the Holy Roman Empire which were at first largely controlled by Habsburg Spain (Spanish Netherlands, 1556–1714) and later by the A ...

(Dutch: Zuidelijke Nederlanden, Spanish: Países Bajos del Sur, French: Pays-Bas du sud, also called the Catholic Netherlands), a part of the Low Countries controlled by Spain (Spanish Netherlands, 1579–1713), then by Austria after the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 (Austrian Netherlands, 1713–1794). The Southern Netherlands remained part of the Burgundian Circle

The Burgundian Circle (german: Burgundischer Kreis, nl, Bourgondische Kreits, french: Cercle de Bourgogne) was an Imperial Circle of the Holy Roman Empire created in 1512 and significantly enlarged in 1548. In addition to the Free County of Burg ...

of the Holy Roman Empire until its annexation to France in 1794.

From February to May 1638, a plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

episode made victims in Ledringhem.

French rule

1646 taking of Furnes (Veurne), Dunkirk andCourtrai

Kortrijk ( , ; vls, Kortryk or ''Kortrik''; french: Courtrai ; la, Cortoriacum), sometimes known in English as Courtrai or Courtray ( ), is a Belgian city and municipality in the Flemish province of West Flanders.

It is the capital and large ...

by Duc d'Enghien

Duke of Enghien (french: Duc d'Enghien, pronounced with a silent ''i'') was a noble title pertaining to the House of Condé. It was only associated with the town of Enghien for a short time.

Dukes of Enghien – first creation (1566–1569)

The ...

1652 Dunkirk taken back by the Spanish.

On 14 June 1658, Spanish troops of Condé and Juan José de Austria

John Joseph of Austria or John of Austria (the Younger) ( es, Don Juan José de Austria; 7 April 1629 – 17 September 1679) was a Spanish general and political figure. He was the only illegitimate son of Philip IV of Spain to be acknowledge ...

had a severe defeat at the battle of the Dunes, near Dunkirk. Turenne continue his triumphant march into Flanders.

On 22 May 1659, France, England and Netherlands signed the ''Hedges Concerto'' treaty.

1659 Treaty of the Pyrenees

The Treaty of the Pyrenees (french: Traité des Pyrénées; es, Tratado de los Pirineos; ca, Tractat dels Pirineus) was signed on 7 November 1659 on Pheasant Island, and ended the Franco-Spanish War that had begun in 1635.

Negotiations were ...

1662 Sale of Dunkirk

The Sale of Dunkirk took place on when Charles II of England sold his sovereign rights to Dunkirk and Fort-Mardyck to his cousin Louis XIV of France.

Context

Dunkirk was occupied by English forces of the Protectorate in 1658, when it was captured ...

by the English to the French

1672 Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, also known as the Dutch War (french: Guerre de Hollande; nl, Hollandse Oorlog), was fought between France and the Dutch Republic, supported by its allies the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark-Nor ...

1677 Battle of Cassel

1678 taking of Saint-Omer

Saint-Omer (; vls, Sint-Omaars) is a commune and sub-prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais department in France.

It is west-northwest of Lille on the railway to Calais, and is located in the Artois province. The town is named after Saint Audoma ...

, Treaties of Nijmegen, end of the war

Parts of Flanders became a French possession following the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1668, ending the War of Devolution

In the 1667 to 1668 War of Devolution (, ), France occupied large parts of the Spanish Netherlands and Franche-Comté, both then provinces of the Holy Roman Empire (and properties of the King of Spain). The name derives from an obscure law k ...

(1667–1668) which saw Louis XIV

Louis XIV (Louis Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was List of French monarchs, King of France from 14 May 1643 until his death in 1715. His reign of 72 years and 110 days is the Li ...

's French armies overrun the Habsburg-controlled Spanish Netherlands. With the fall of the fortresses of Bergues (6 June 1667), Louis XIV took hold of Ledringhem, part of the Châtellenie.

France gained some territory in Flanders, but nearly all of the Spanish Netherlands, as well as the Franche-Comté, was returned to Spain. Inwardly, Louis XIV was seething. He had hoped to take the entirety of the Spanish Netherlands and felt betrayed by the Dutch, who, to French eyes, were only independent due to French assistance in the Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) ( c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Ref ...

. The War of Devolution thus led directly to the Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, also known as the Dutch War (french: Guerre de Hollande; nl, Hollandse Oorlog), was fought between France and the Dutch Republic, supported by its allies the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark-Nor ...

of 1672–1678.

The consequences of the War of Devolution were manifold. From a purely military perspective, France had gained some advantages, by breaking through the ring of fortresses that surrounded the Spanish Netherlands. This simultaneously increased the French defensive power, as Vauban immediately set about expanding the conquered cities into strong fortifications. These in turn served as starting points from which further French campaigns of conquest could be launched in later wars.

French Revolution

After the French Revolution, French rule has been secured with revolutionary victory in the Battle of Hondshoote in 1793 against English and Austrian troops wanting to get hold of Dunkirk port.In 1794 the entire region of the Spanish/Austrian Netherlands was overrun by France ending the existence of this territory as such. This was resisted by the Flamingant movement organized by Roman Catholic clergy. Austria confirmed the loss of its territories by the

Treaty of Campo Formio

The Treaty of Campo Formio (today Campoformido) was signed on 17 October 1797 (26 Vendémiaire VI) by Napoleon Bonaparte and Count Philipp von Cobenzl as representatives of the French Republic and the Austrian monarchy, respectively. The trea ...

, in 1797.

Henri-Louis de Guernoval, marquis d'Esquelbecq (1729–1801) (marquis de Ledringhem), captain in second of Louis XIV Royal-Cravattes regiment was the last of the nobility member to administer Ledringhem.

First French Empire

Ledringhem became part of the

Ledringhem became part of the First French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental E ...

1810 Napoleonic Nord département. Most of the Low Countries were also annexed. After Napoleon's defeat at Leipzig (October 1813), the French troops retreated to France. The Treaty of Kortrijk (Dutch: ''Verdrag van Kortrijk''), signed 28 March 1820 in the Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

city of Kortrijk

Kortrijk ( , ; vls, Kortryk or ''Kortrik''; french: Courtrai ; la, Cortoriacum), sometimes known in English as Courtrai or Courtray ( ), is a Belgian city and municipality in the Flemish province of West Flanders.

It is the capital and larg ...

laid out the boundaries between France and the United Kingdom of the Netherlands

The United Kingdom of the Netherlands ( nl, Verenigd Koninkrijk der Nederlanden; french: Royaume uni des Pays-Bas) is the unofficial name given to the Kingdom of the Netherlands as it existed between 1815 and 1839. The United Netherlands was cr ...

(under the reign of King William I of the Netherlands

William I (Willem Frederik, Prince of Orange-Nassau; 24 August 1772 – 12 December 1843) was a Prince of Orange, the King of the Netherlands and Grand Duke of Luxembourg.

He was the son of the last Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic, who went ...

). Nowadays, these boundaries still stand, with some minor corrections, as the official boundary between Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

and France. In 1830, the Belgian Revolution led to the separation of the Southern Provinces from the Netherlands.

World wars

Shrapnel, like canon shells and bullet casings can still be found in and around the fields here. They are usually found by farmers ploughing, and date back to World Wars. ; World War I : German Schlieffen Plan in 1914 was to invade Belgium to better attack France to the north. Thus, at the beginning, the war was a mobility war. At that time, French bicycle riding 3e Groupe de Chasseurs Cyclistes were in Ledringhem during theFirst Battle of Ypres

The First Battle of Ypres (french: Première Bataille des Flandres; german: Erste Flandernschlacht – was a battle of the First World War, fought on the Western Front around Ypres, in West Flanders, Belgium. The battle was part of the Firs ...

in November 1914. As the war turned into a trenches war with the front established to the east near Ypres, some 30 km away, Ledringhem served as a resting and training place (''billet

A billet is a living-quarters to which a soldier is assigned to sleep. Historically, a billet was a private dwelling that was required to accept the soldier.

Soldiers are generally billeted in barracks or garrisons when not on combat duty, alth ...

'') to the rear. French 12th cuirassiers were there in December 1914 – September 1915, British horse-riding 20th Hussars 7 May 1915, the 75th Brigade RFA in May–June 1916, the 1st Royal Marine Battalion from 14 to 22 November 1917, French 114ème Régiment d'Artillerie Lourde and 15e Régiment de Dragons in May 1918, and 2e Régiment d'Artillerie de Campagne in August 1918. These French troops are then replaced (26–28 June 1918) by English men of the 187th and 190th brigades of the 41st division (2e RAC JMO 26N906-23, 27 & 31).

; World War II :

A violent battle took place in Ledringhem during the Battle of France in May 1940, which involved British soldiers against German troops. On 27 to 29 May 1940, the British 5th Glosters got separated from the rest of the British forces in Ledringhem and became involved in fierce combats against motorized German troops. Several casualties among the British soldiers, including officers and also French civilians, occurred during the fight. Nevertheless, the village was never conquered by the Germans at that time, and finally the British escaped to embark in Dunkirk evacuation during Operation Dynamo. There is a Military Cemetery located at the site of the battle.

Other casualties were made by Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler

The 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler or SS Division Leibstandarte, abbreviated as LSSAH, (german: 1. SS-Panzerdivision "Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler") began as Adolf Hitler's personal bodyguard unit, responsible for guarding ...

by killing prisoners gathered in a barn at '' La Plaine au Bois'' in Wormhoudt

Wormhout (; before 1975: ''Wormhoudt''; vls, Wormout) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France. Several people in Wormhout still speak West Flemish, a local dialect of Dutch and the traditional language of the region, while Frenc ...

on Tuesday 28 May 1940.

Also during that period, the windmill in Ledringhem has been burnt down. The head of the windmill served to repair the ''Drievenmeulen'' in Steenvoorde

Steenvoorde () is a commune in the Nord department in northern France. Once part of the Seventeen Provinces of the Low Countries, Steenvoorde was the site of the beginning of the Beeldenstorm, or " Iconoclastic Fury." Today the city is known for ...

.

After the 1940 defeat, Belgium and Northern France were put under Nazi Germany control. The structure remained in existence until July 1944.

War monuments

The French Monument to the Dead (''Monument aux Morts'') presents 25 names, 15 of which being French soldiers killed during the first World War, the other ten being civilian victims during World War II. It is situated in the cemetery near the church. In the British military part of the cemetery containing 52 graves, there is aCross of Sacrifice

The Cross of Sacrifice is a Commonwealth war memorial designed in 1918 by Sir Reginald Blomfield for the Imperial War Graves Commission (now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission). It is present in Commonwealth war cemeteries containing 40 or m ...

.

Administration

Town hall :. Mayors : * 2001–2008, 2008–2014, 2014–current : Christian Delassus * 1995–2001 : Christian (Roger Germain) Deblock * Jules Arthur Gabriel Deblock (1877–?), father of Roger * 1893 : Amand (Aimé Erremond) Cailliau (1842–1923) * 1870 : M. Vanhoucke * 1861 : Pierre (Augustin Ambroise) Devulder (1814–?) * 1854 : M. Wispelaere. * 1806 : M. Blanckaert * Pierre Jacques Cornil Hondermarck (1774–1834) * Charles Winoc Hondermarck (1772–1829) Ledringhem doesn't participate in a twinnage program with a foreign country municipality. ; personalities * Roger Deblock (1908–1994, in Ledringhem), senator of Nord from 1969 to 1974Ledrinhemat fr.geneawiki.com (French) * Gabriel Deblock (1935 in Ledringhem-2006), son of Roger, député of Nord from 1993 to 1997

Transportation

There is a bus stop, for pupils to go to collège in Wormhout, or the high school in Hazebrouck, or to go to Wormhout. The nearest railway stations are inArnèke

Arnèke (; vls, label=French Flemish, Arnyke; nl, Arneke) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

Geography

Arnèke is situated on the D55 (''route de Wormhout''). The small river Peene Becque is flowing through the village. T ...

and Esquelbecq

Esquelbecq (; from ) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

Its southern limit with Ledringhem is ''chemin de Rubrouck''.

Heraldry

History

In 1436, Wautier de Ghistelles was ''seigneur d'Ekelsbeke et de Ledringhem'' (Lord ...

, for transport to Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.

or Hazebrouck and Lille Flandres

Lille-Flandres station ( French: ''Gare de Lille-Flandres'', Dutch: ''Rijsel Vlaanderen'') is the main railway station of Lille, capital of French Flanders. It is a terminus for SNCF Intercity and regional trains. It opened in 1842 as the ''Gare ...

.

Accommodations

estaminet

French cuisine () is the cooking traditions and practices from France. It has been influenced over the centuries by the many surrounding cultures of Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Germany and Belgium, in addition to the food traditions of the r ...

(Flemish-style café-restaurant) which is also a general store situated on the main square and the inn ''Auberge Du Kok-smid'' situated along ''route de Wormhout''.

Economy

The village main resources are agriculture productions. These include cereals (wheat, barley, oat), flax, fodder (mangel) and sugar beets, potatoes, horticulture and cattle raising (cows, pigs, fowls, ...). There are a few other businesses and also a general practitioner.Social life

List of associations in Ledringhem: * ''Alcyon, Association pour le rayonnement de la francophonie'', help to French speaking students * ''Association Audrey 59 Steven'' * ''Association des parents d'élèves de l'école publique de Ledringhem'' (APEEPL), pupil's parents association * ''Association Jeunesse et ambitions'' * ''Association Nature et Patrimoine de Ledringhem'' (ANPL), Nature and Patrimony association * ''Club Agro Convergence'' * ''Frisons en Flandre'', Friesian horses association * ''Jogging club de Wormhout'' * ''La Jet moins set moto'', moto association * ''Lame Soeur'', help to musicians association * ''La Petite Reine Ledringhemoise'', bicycling association * ''L'Art Sauv.'', art at the hospital association * ''Les Pieds Tanqués'', pétanque association * ''Les Quickpitchenaeres'', carnival association * ''Union nationale des combattants de Ledringhem'', war veterans association * ''Wormhout Volley-Sport'' * international association : ''Association Franco-Britannique de la Plaine au bois'', French-British association for ''La Plaine au bois'' massacre commemoration, with mayors of Esquelbecq, Ledringhem andLlandudno

Llandudno (, ) is a seaside resort, town and community in Conwy County Borough, Wales, located on the Creuddyn peninsula, which protrudes into the Irish Sea. In the 2011 UK census, the community – which includes Gogarth, Penrhyn Bay, Craig ...

.

Patron saint fest (''Ducasse'') occurs during June first Sunday.

Main sights

* ''Paeltronck Hoeve'' (French : ''ferme du têtard borne'') is a typical Flemish farm.

;Religious patrimony

* The catholic Hall church-type "hallekerque", with three same-sized naves, is dedicated to

* ''Paeltronck Hoeve'' (French : ''ferme du têtard borne'') is a typical Flemish farm.

;Religious patrimony

* The catholic Hall church-type "hallekerque", with three same-sized naves, is dedicated to Audomar

Saint Audomar (died 670), better known as Saint Omer, was a bishop of Thérouanne, after whom nearby Saint-Omer in northern France was named.

Biography

He was born of a distinguished family of Coutances, then under the Frankish realm of Neus ...

(''Saint-Omer'') dating 16th century (1548), with an organ and an 18th-century pulpit, an 18th-century tabernacle

According to the Hebrew Bible, the tabernacle ( he, מִשְׁכַּן, mīškān, residence, dwelling place), also known as the Tent of the Congregation ( he, link=no, אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד, ’ōhel mō‘ēḏ, also Tent of Meeting, etc.), ...

and a 17th-century retable

A retable is a structure or element placed either on or immediately behind and above the altar or communion table of a church. At the minimum it may be a simple shelf for candles behind an altar, but it can also be a large and elaborate structure ...

dedicated to saint Omer. It is made of red brick

A brick is a type of block used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term ''brick'' denotes a block composed of dried clay, but is now also used informally to denote other chemically cured cons ...

s. There are several runic

Runes are the letters in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were used to write various Germanic languages (with some exceptions) before they adopted the Latin alphabet, and for specialised ...

-like shapes, made of yellow-coloured bricks, included in the red-coloured brick masonry, around the building.(French)

slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

s.

* Several small chapel

A chapel is a Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. Firstly, smaller spaces inside a church that have their own altar are often called chapels; the Lady chapel is a common type ...

s and crosses are scattered all around the village.

apse

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an '' exedra''. ...

chevet and calvary

Calvary ( la, Calvariae or ) or Golgotha ( grc-gre, Γολγοθᾶ, ''Golgothâ'') was a site immediately outside Jerusalem's walls where Jesus was said to have been crucified according to the canonical Gospels. Since at least the early medie ...

File:LEDRINGHEM église St Omer.jpg, Church hall or hallekerk (hallekerk), made up of three naves, Romanesque A runic-shaped design on the gable of the church, on the left

File:Ledringhem-runes.jpg, Examples of rune-shaped designs found on Ledringhem's church (a five- lozenges cross

A cross is a geometrical figure consisting of two intersecting lines or bars, usually perpendicular to each other. The lines usually run vertically and horizontally. A cross of oblique lines, in the shape of the Latin letter X, is termed a s ...

and a heart

The heart is a muscular Organ (biology), organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as ca ...

on the gable

A gable is the generally triangular portion of a wall between the edges of intersecting roof pitches. The shape of the gable and how it is detailed depends on the structural system used, which reflects climate, material availability, and aest ...

)

References

External links

Ledringem's natural catastophy risks assessment on prim.net

(French)

Ledringhem's news on lavoixdunord.fr

(French)

(French)

(French) ; Photographs

(French)

Photographs of Ledringhem on Le Masquelour's blogger site

(French)

Photographs of Ledringhem on www.picturefrance.fr

(French) {{Authority control Communes of Nord (French department) Treasure troves of France Treasure troves of late antiquity French Flanders