Lazar Kaganovich on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich, also Kahanovich (russian: Ла́зарь Моисе́евич Кагано́вич, Lázar' Moiséyevich Kaganóvich; – 25 July 1991), was a

In 1932, he led the suppression of the workers' strike in Ivanovo-Voznesensk.

Kaganovich (together with

Kaganovich (together with

From 1935 to 1937, Kaganovich worked as Narkom (Minister) for the

From 1935 to 1937, Kaganovich worked as Narkom (Minister) for the

Kaganovich was married to Maria Markovna Kaganovich (née Privorotskaya) [1894-1961], a fellow assimilated History of the Jews in Kyiv, Kievan Jew who was part of the revolutionary effort since 1909. Mrs. Kaganovich spent many years as a powerful municipal official, directly ordering the demolition of the Iberian Gate and Chapel and

Kaganovich was married to Maria Markovna Kaganovich (née Privorotskaya) [1894-1961], a fellow assimilated History of the Jews in Kyiv, Kievan Jew who was part of the revolutionary effort since 1909. Mrs. Kaganovich spent many years as a powerful municipal official, directly ordering the demolition of the Iberian Gate and Chapel and

''Time'' October 24, 1932 The expression was used in France as early as 1742, and then more famously in 1796 in reference to a War in the Vendée, French Royalist populist counter-revolution in the Vendée. According to ''Time'' magazine and some newspapers, Lazar Kaganovich's son Mikhail (named after Lazar's late brother) married Svetlana Alliluyeva, Svetlana Dzhugashvili, daughter of Joseph Stalin on 3 July 1951.Social Notes"

''Time'' July 23, 1951 Svetlana in her memoirs denies even the existence of Mikhail. Kaganovich is portrayed by Irish actor Dermot Crowley in the 2017 historical comedy ''The Death of Stalin''.

Profile at http://www.hrono.ru

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Kaganovich, Lazar 1893 births 1991 deaths Stalinism Anti-revisionists Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery Expelled members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union First convocation members of the Verkhovna Rada of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic First Secretaries of the Communist Party of Ukraine (Soviet Union) Genocide perpetrators Great Purge perpetrators Heroes of Socialist Labour Holodomor Jewish socialists Jewish Soviet politicians Old Bolsheviks People from Kiev Governorate People from Kyiv Oblast People's Commissariat of Heavy Industry People's commissars and ministers of the Soviet Union Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union members Recipients of the Order of Lenin Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Soviet people of World War II Ukrainian communists

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

politician and administrator, and one of the main associates of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

. He was one of several associates who helped Stalin to seize power, demonstrating exceptional brutality towards those deemed threats to Stalin's regime

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

and facilitating the executions of thousands of people.

Born to Jewish parents in modern Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

(then part of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

) in 1893, Kaganovich was the son of Moisei Benovich Kaganovich (1863-1923) and Genya Iosifovna Dubinskaya (1860-1933). Of the 13 children born to the family, 6 died in infancy. Lazar had four elder brothers, all of whom became members of the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

party. Several of Lazar's brothers ended up occupying positions of varying significance in the Soviet government. Mikhail Kaganovich

Mikhail Moiseyevich Kaganovich (russian: Михаи́л Моисе́евич Кагано́вич; 16 October 1888 – 1 July 1941) was a Soviet politician. He was the older brother of Lazar Kaganovich. He was born in Kiev Governorate. Kaganovich ...

(1888–1941) served as People's Commissar of Defence Industry before being appointed Head of the People's Commissariat of the Aviation Industry of the USSR, while Yuli Kaganovich (1892–1962) became the 3rd First Secretary of the Gorky Regional Committee of the CPSU. Israel Kaganovich (1884–1973) was made the head of the Main Directorate for Cattle Harvesting of the Ministry of Meat and Dairy Industry

The Ministry of Meat and Dairy Industry (Minmyasomolprom; russian: Министерство мясной и молочной промышленности) was a government ministry in the Soviet Union.

History

The People's Commissariat of Meat and ...

. However, Aron Moiseevich Kaganovich (1888-1960s) apparently decided against follow his siblings into government, and did not pursue a career in politics. Lazar also had a sister, Rachel Moiseevna Kaganovich (1883-1926), who married Mordechai Ber Lantzman; they lived together in Chernobyl

Chernobyl ( , ; russian: Чернобыль, ) or Chornobyl ( uk, Чорнобиль, ) is a partially abandoned city in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, situated in the Vyshhorod Raion of northern Kyiv Oblast, Ukraine. Chernobyl is about n ...

for a period, but she subsequently died in the 1920s and was interred in Kiev.

Kaganovich worked as a shoemaker and became a member of the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, joining the party around 1911. As an organizer, Kaganovich was active in Yuzovka (Donetsk

Donetsk ( , ; uk, Донецьк, translit=Donets'k ; russian: Донецк ), formerly known as Aleksandrovka, Yuzivka (or Hughesovka), Stalin and Stalino (see also: cities' alternative names), is an industrial city in eastern Ukraine loc ...

), Saratov and Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

throughout the 1910s, and led a revolt in Belarus during the 1917 October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

. In the early 1920s, he helped consolidate Soviet rule in Turkestan. In 1922, Stalin placed Kaganovich in charge of organizational work within the Communist Party, through which he helped Stalin consolidate his grip of the party bureaucracy. Kaganovich rose quickly through the ranks, becoming a full member of the Central Committee in 1924, First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine in 1925, and Secretary of the Central Committee as well as a member of the Politburo in 1930.

Kaganovich played a central role during the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

, personally signing over 180 lists that sent tens of thousands of people to their deaths. For his ruthlessness, he received the nickname "Iron Lazar". From the mid-1930s onwards, Kaganovich served as people's commissar for Railways

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

, Heavy Industry and Oil Industry

The petroleum industry, also known as the oil industry or the oil patch, includes the global processes of exploration, extraction, refining, transportation (often by oil tankers and pipelines), and marketing of petroleum products. The larges ...

.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, Kaganovich was commissar of the North Caucasian and Transcaucasian Fronts. After the war, apart from serving in various industrial posts, Kaganovich was also made deputy head of the Soviet government. After Stalin's death in 1953 he quickly lost influence. Following an unsuccessful coup attempt against Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

in 1957, Kaganovich was forced to retire from the Presidium and the Central Committee. In 1961 he was expelled from the party, and lived out his life as a pensioner in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

. At his death in 1991, he was the last surviving Old Bolshevik

Old Bolshevik (russian: ста́рый большеви́к, ''stary bolshevik''), also called Old Bolshevik Guard or Old Party Guard, was an unofficial designation for a member of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Par ...

. The Soviet Union itself outlasted him by only five months, dissolving on 26 December 1991.

Early life

Kaganovich was born in 1893 toJew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

ish parents

in the village of Kabany, Radomyshl uyezd

An uezd (also spelled uyezd; rus, уе́зд, p=ʊˈjest), or povit in a Ukrainian context ( uk, повіт), or Kreis in Baltic-German context, was a type of administrative subdivision of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, the Russian Empire, and the ea ...

, Kiev Governorate

Kiev Governorate, r=Kievskaya guberniya; uk, Київська губернія, Kyivska huberniia (, ) was an administrative division of the Russian Empire from 1796 to 1919 and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic from 1919 to 1925. It wa ...

, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

(today Dibrova, Kyiv Oblast

Kyiv Oblast ( uk, Ки́ївська о́бласть, translit=Kyïvska oblast), also called Kyivshchyna ( uk, Ки́ївщина), is an oblast (province) in central and northern Ukraine. It surrounds, but does not include, the city of Kyiv, ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

). Although not from a "fanatically observant" family, according to Kaganovich, he spoke Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

at home.

Around 1911, he joined the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

party (his older brother Mikhail Kaganovich

Mikhail Moiseyevich Kaganovich (russian: Михаи́л Моисе́евич Кагано́вич; 16 October 1888 – 1 July 1941) was a Soviet politician. He was the older brother of Lazar Kaganovich. He was born in Kiev Governorate. Kaganovich ...

had become a member in 1905). Early in his political career, in 1915, Kaganovich became a Communist organizer at a shoe factory where he worked. During the same year he was arrested and sent back to Kabany.

Revolution and Civil War

During March and April 1917, he served as the Chairman of the Tanners Union and as the vice-chairman of the YuzovkaSoviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. In May 1917, he became the leader of the military organization of Bolsheviks in Saratov, and in August 1917, he became the leader of the '' Polessky Committee'' of the Bolshevik party in Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

. During the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

of 1917 he led the revolt in Gomel

Gomel (russian: Гомель, ) or Homiel ( be, Гомель, ) is the administrative centre of Gomel Region and the second-largest city in Belarus with 526,872 inhabitants (2015 census).

Etymology

There are at least six narratives of the o ...

.

In 1918 Kaganovich acted as Commissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English transliteration of the Russian (''komissar''), which means ' commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the political commissars of Soviet and E ...

of the propaganda department of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

. From May 1918 to August 1919 he was the Chairman of the Ispolkom The Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, commonly known as the Ispolkom (russian: исполком, исполнительный комитет, literally " executive committee") was a self-appointed executive committee of the Petrograd So ...

(Committee) of the Nizhny Novgorod Governorate

The Nizhny Novgorod Governorate (Pre-reformed rus, Нижегородская губернія, r=Nizhegorodskaya guberniya, p=nʲɪʐɨɡɐˈrotskəjə ɡʊˈbʲernʲɪjə), was an administrative division (a '' guberniya'') of the Russian Empi ...

. In 1919–1920, he served as governor of the Voronezh Governorate. The years 1920 to 1922 he spent in Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan ( or ; tk, Türkmenistan / Түркменистан, ) is a country located in Central Asia, bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the s ...

as one of the leaders of the Bolshevik struggle against local Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

rebels (''basmach

The Basmachi movement (russian: Басмачество, ''Basmachestvo'', derived from Uzbek: "Basmachi" meaning "bandits") was an uprising against Russian Imperial and Soviet rule by the Muslim peoples of Central Asia.

The movement's roots ...

i''), and also commanding the succeeding punitive expeditions against local opposition.

Communist functionary

In May 1922,Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

became the General Secretary of the Communist Party and immediately transferred Kaganovich to his apparatus to head the ''Organizational Bureau'' or Orgburo

The Orgburo (russian: Оргбюро́), also known as the Organisational Bureau (russian: организационное бюро), of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union existed from 1919 to 1952, when it was abo ...

of the Secretariat. This department was responsible for all assignments within the apparatus of the Communist Party. Working there, Kaganovich helped to place Stalin's supporters in important jobs within the Communist Party bureaucracy. In this position he became noted for his great work capacity and for his personal loyalty to Stalin. He stated publicly that he would execute absolutely any order from Stalin, which at that time was a novelty.

In 1924, Kaganovich became a full member of the Central Committee, after having first been elected as a candidate one year earlier. From 1925 to 1928, Kaganovich was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Ukrainian SSR. He was given the task of "ukrainizatsiya" – meaning at that time the building up of Ukrainian communist popular cadres. He also had the duty of implementing collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

and the policy of economic suppression of the kulak

Kulak (; russian: кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈlak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned ove ...

s (wealthier peasants). He opposed the more moderate policy of Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Буха́рин) ( – 15 March 1938) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, Marxist philosopher and economist and prolific author on revolutionary theory. ...

, who argued in favor of the "peaceful integration of kulaks into socialism." In 1928, due to numerous protests against Kaganovich's management, Stalin was forced to transfer Kaganovich from Ukraine to Moscow, where he returned to his position as a Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, a job he held until 1939. As Secretary, he endorsed Stalin's struggle against the so-called Left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album '' Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relative direction opposite of right

* ...

and Right

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical ...

Oppositions within the Communist Party, in the hope that Stalin would become the sole leader of the country. In 1933 and 1934, he served as the Chairman of the Commission for Vetting of the Party Membership (''Tsentralnaya komissiya po proverke partiynykh ryadov'') and ensured personally that nobody associated with anti-Stalin opposition would be permitted to remain a Communist Party member. In 1934, at the XVII Congress of the Communist Party, Kaganovich chaired the Counting Committee. He falsified voting for positions in the Central Committee, deleting 290 votes opposing the Stalin candidacy. His actions resulted in Stalin's being re-elected as the General Secretary instead of Sergey Kirov

Sergei Mironovich Kirov (né Kostrikov; 27 March 1886 – 1 December 1934) was a Soviet politician and Bolshevik revolutionary whose assassination led to the first Great Purge.

Kirov was an early revolutionary in the Russian Empire and memb ...

. By the rules, the candidate receiving fewer opposing votes should become the General Secretary. Before Kaganovich's falsification, Stalin received 292 opposing votes and Kirov only three. However, the "official" result (due to the interference of Kaganovich) saw Stalin with just two opposing votes (Radzinsky, 1996).

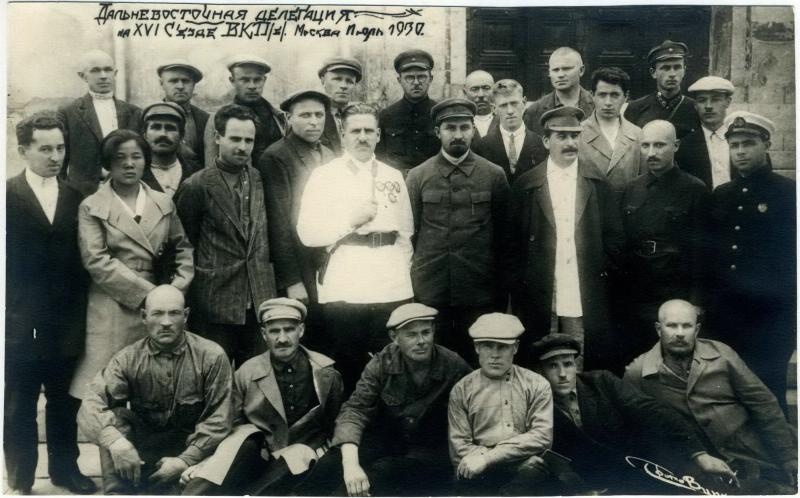

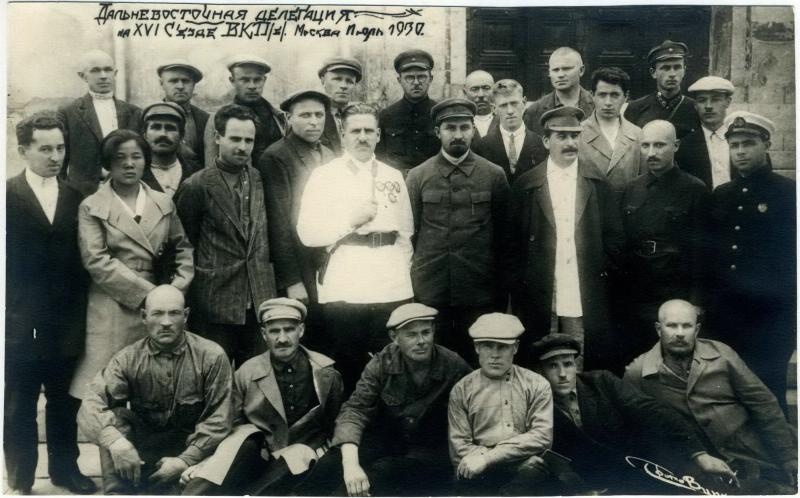

In 1930, Kaganovich became a member of the Soviet Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contracti ...

and the First Secretary of the Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

Obkom of the Communist Party (1930–1935). He later headed the Moscow Gorkom

The organization of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was based on the principles of democratic centralism.

The governing body of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was the Party Congress, which initially met annually but whose m ...

of the Communist Party (1931–1934).

He also supervised implementation of many of Stalin's economic

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with th ...

policies, including the collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

of agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

and rapid industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

. During this period, he also supervised destruction of many of the city's oldest monuments, including the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour

The Cathedral of Christ the Saviour ( rus, Храм Христа́ Спаси́теля, r=Khram Khristá Spasítelya, p=xram xrʲɪˈsta spɐˈsʲitʲɪlʲə) is a Russian Orthodox cathedral in Moscow, Russia, on the northern bank of the Moskv ...

.Rees, Edward Afron. 1994. Stalinism and Soviet Rail Transport, 1928–41. Birmingham: Palgrave MacmillaIn 1932, he led the suppression of the workers' strike in Ivanovo-Voznesensk.

Moscow Metro

On June 15, 1931, at the Plenum of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), after a report by the first secretary of the Moscow City Party Committee, Lazar Kaganovich, a decision was made to build the Moscow metro to improve the transport situation in the city and partially relieve tram lines. In the 1930s, Kaganovich – along with project managers Ivan Kuznetsov and, later Isaac Segal – organized and led the building of the first Soviet underground rapid-transport system, theMoscow Metro

The Moscow Metro) is a metro system serving the Russian capital of Moscow as well as the neighbouring cities of Krasnogorsk, Reutov, Lyubertsy and Kotelniki in Moscow Oblast. Opened in 1935 with one line and 13 stations, it was the first ...

, known as ''Metropoliten imeni L.M. Kaganovicha'' after him until 1955.

On October 15, 1941, L. M. Kaganovich received an order to close the Moscow Metro, and within 3 hours to prepare proposals for its destruction, as a strategically important object. The metro was supposed to be destroyed, and the remaining cars and equipment removed. On the morning of October 16, 1941, on the day of the panic in Moscow, the metro was not opened for the first time. It was the only day in the history of the Moscow metro when it did not work. By evening, the order to destroy the metro was canceled.

In 1955, after the death of Stalin, the Moscow Metro was renamed to no longer include Kaganovich's name.

Responsibility for the 1932 - 1933 famine

Kaganovich (together with

Kaganovich (together with Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

) participated with the All-Ukrainian Party Conference of 1930 and were given the task of implementation of the collectivization policy that influenced the 1932–33 famine (known as the Holodomor

The Holodomor ( uk, Голодомо́р, Holodomor, ; derived from uk, морити голодом, lit=to kill by starvation, translit=moryty holodom, label=none), also known as the Terror-Famine or the Great Famine, was a man-made famin ...

in Ukraine). Similar policies also inflicted enormous suffering on the Soviet Central Asian republic of Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

, the Kuban

Kuban ( Russian and Ukrainian: Кубань; ady, Пшызэ) is a historical and geographical region of Southern Russia surrounding the Kuban River, on the Black Sea between the Don Steppe, the Volga Delta and the Caucasus, and separated ...

region, Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

, the lower Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catch ...

region, and other parts of the Soviet Union. As an emissary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, Kaganovich traveled to Ukraine, the central regions of the USSR, the Northern Caucasus

The North Caucasus, ( ady, Темыр Къафкъас, Temır Qafqas; kbd, Ишхъэрэ Къаукъаз, İṩxhərə Qauqaz; ce, Къилбаседа Кавказ, Q̇ilbaseda Kavkaz; , os, Цӕгат Кавказ, Cægat Kavkaz, inh, ...

, and Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

demanding the acceleration of collectivization and repressions against the Kulaks, who were generally blamed for the slow progress of collectivization.

Attorney and 'father of the UN Genocide Convention' Rafael Lemkin in his work ''Soviet Genocide in the Ukraine'' described the Holodomor as a genocide of a totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

regime.

On 13 January 2010, Kyiv Appellate Court

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much of ...

posthumously

Posthumous may refer to:

* Posthumous award - an award, prize or medal granted after the recipient's death

* Posthumous publication

Posthumous publication refers to material that is published after the author's death. This can be because the auth ...

found Kaganovich, Postyshev, Kosior, Chubar and other Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

Communist Party functionaries guilty of genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the ...

against Ukrainians during the catastrophic Holodomor famine. Though they were pronounced guilty as criminals, the case was ended immediately according to paragraph 8 of Article 6 of the Criminal Procedural Code of Ukraine. By New Year's Day

New Year's Day is a festival observed in most of the world on 1 January, the first day of the year in the modern Gregorian calendar. 1 January is also New Year's Day on the Julian calendar, but this is not the same day as the Gregorian one. Whi ...

, the Security Service of Ukraine

The Security Service of Ukraine ( uk, Служба безпеки України, translit=Sluzhba bezpeky Ukrainy}) or SBU ( uk, СБУ, link=no) is the law enforcement authority and main intelligence and security agency of the Ukraini ...

had finished pre-court investigation and transferred its materials to the Prosecutor General of Ukraine

The prosecutor general of Ukraine (also procurator general of Ukraine, uk, Генеральний прокурор України) heads the system of official prosecution in courts known as the Office of the Prosecutor General ( uk, Офіс ...

. The materials consist of over 250 volumes of archive documents (from within Ukraine as well as from abroad), interviews with witnesses, and expert analysis of several institutes of National Academies of Sciences. Oleksandr Medvedko

Oleksandr Medvedko ( uk, Олександр Іванович Медведько) is a former Prosecutor General of Ukraine Medvedko was installed in a political deal with the Party of Regions.

Biography

In December 2009, during the 2010 Ukrainian ...

, the Prosecutor General, stated that the material proves that a genocide occurred in Ukraine.

"Iron Lazar"

From 1935 to 1937, Kaganovich worked as Narkom (Minister) for the

From 1935 to 1937, Kaganovich worked as Narkom (Minister) for the railways

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

. Even before the start of the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

s, he organized the arrests of thousands of railway administrators and managers accused of sabotage.

From 1937 to 1939, Kaganovich served as Narkom for Heavy Industry. During 1939–1940, he served as Narkom for the Oil Industry.

Each of his assignments was associated with arrests in order to improve discipline and compliance with Stalin's policies.

In all Party conferences of the later 1930s, he made speeches demanding increased efforts in the search for and prosecution of "foreign spies" and "saboteurs." For his ruthlessness in the execution of Stalin's orders, he was nicknamed "Iron Lazar." During the period of the Great Terror, starting in 1936, Kaganovich's signature appears on 188 out of 357 documented execution lists.

One of many who perished during these years was Lazar's brother, Mikhail Kaganovich

Mikhail Moiseyevich Kaganovich (russian: Михаи́л Моисе́евич Кагано́вич; 16 October 1888 – 1 July 1941) was a Soviet politician. He was the older brother of Lazar Kaganovich. He was born in Kiev Governorate. Kaganovich ...

, who was People's Commissar of the Aviation Industry. On 10 January 1940 Mikhail was demoted to director of aviation plant 124 in Kazan

Kazan ( ; rus, Казань, p=kɐˈzanʲ; tt-Cyrl, Казан, ''Qazan'', IPA: Help:IPA/Tatar, ɑzan is the capital city, capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and t ...

. In February 1941, during the 18th Conference of the Communist Party, Mikhail was warned that if the plant missed its quotas he would be eliminated from the Party. On 1 June 1941 Stalin mentioned to Lazar that he had heard that Mikhail was "associating with the right wing." Lazar reportedly did not speak in the defence of his brother to Stalin, but did notify him by telephone. The same day Mikhail committed suicide. Other versions of the events can be found on Mikhail Kaganovich

Mikhail Moiseyevich Kaganovich (russian: Михаи́л Моисе́евич Кагано́вич; 16 October 1888 – 1 July 1941) was a Soviet politician. He was the older brother of Lazar Kaganovich. He was born in Kiev Governorate. Kaganovich ...

's wiki.

During his time serving as Railways Commissar, Kaganovich participated in the murder of 36,000 people by signing death lists. Kaganovich had exterminated so many railwaymen that one official called to warn that one line was entirely unmanned.

During World War II (known as the Great Patriotic War

The Eastern Front of World War II was a theatre of conflict between the European Axis powers against the Soviet Union (USSR), Poland and other Allies, which encompassed Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Northeast Europe (Baltics), an ...

in the USSR), Kaganovich was Commissar (Member of the Military Council) of the North Caucasian and Transcaucasian Fronts. During 1943–1944, he was again the Narkom for the railways. In 1943, he was presented with the title of Hero of Socialist Labour

The Hero of Socialist Labour (russian: links=no, Герой Социалистического Труда, Geroy Sotsialisticheskogo Truda) was an honorific title in the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact countries from 1938 to 1991. It repre ...

. From 1944 to 1947, Kaganovich was the Minister for Building Materials.

In 1947, he became the First Secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party. From 1948 to 1952, he served as the Chairman of Gossnab

State Supplies of the USSR, known as the Gossnab of USSR (russian: Госснаб СССР) was active from 1948 to 1953, and 1965 to 1991. It was the state committee for material technical supply in the Soviet Union. It was charged with the prim ...

(State Committee for Material-Technical Supply, charged with the primary responsibility for the allocation of producer goods to enterprises, a critical state function in the absence of markets), and from 1952 to 1957, as the First Vice-Premier of the Council of Ministers

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or ...

. He was also the first Chairman of Goskomtrud (State Committee for Labour and Wages, charged with introducing the minimum wage, with other wage policy, and with improving the old-age pension system).

Until 1957, Kaganovich was a voting member of the Politburo as well as the Presidium

A presidium or praesidium is a council of executive officers in some political assemblies that collectively administers its business, either alongside an individual president or in place of one.

Communist states

In Communist states the presid ...

. He was also an early mentor of the eventual First Secretary of the Communist Party Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

, who first became important as Kaganovich's Moscow City deputy during the 1930s. In 1947, when Khrushchev was dismissed as the Party secretary of Ukraine (he remained in the somewhat lesser "chief of government" position), Stalin dispatched Kaganovich to replace him until Khrushchev was reinstated later that year.

Later life

Kaganovich was a doctrinaireStalinist

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory ...

, and though he remained a member of the Presidium, he quickly lost influence after Stalin's death

Joseph Stalin, second leader of the Soviet Union, died on 5 March 1953 at his Kuntsevo Dacha at the age of 74, after suffering a stroke. He was given a state funeral in Moscow on 9 March, with four days of national mourning declared. The day of ...

in March 1953. In 1957, along with fellow devoted Stalinists as well as other opponents of Khrushchev: Molotov, Dmitri Shepilov and Georgy Malenkov

Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov ( – 14 January 1988) was a Soviet politician who briefly succeeded Joseph Stalin as the leader of the Soviet Union. However, at the insistence of the rest of the Presidium, he relinquished control over the p ...

(the so-called Anti-Party Group

The Anti-Party Group ( rus, Антипартийная группа, r=Antipartiynaya gruppa) was a Stalinist group within the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union that unsuccessfully attempted to depose Nikita Khrushchev as Fir ...

), he participated in an abortive party coup against his former protégé Khrushchev, whose criticism of Stalin had become increasingly harsh during the preceding two years. As a result of the unsuccessful coup, Kaganovich was forced to retire from the Presidium and the Central Committee, and was given the job of director of a small potash

Potash () includes various mined and manufactured salts that contain potassium in water- soluble form.

works in the Urals. In 1961, Kaganovich was completely expelled from the Party and became a pensioner living in Moscow. His grandchildren reported that after his dismissal from the Central Committee, Kaganovich (who had a reputation for his temperamental and allegedly violent nature) never again shouted and became a devoted grandfather.

In 1984, his re-admission to the Party was considered by the Politburo, alongside that of Molotov. During the last years of life he played dominoes with fellow pensioners and criticized Soviet media attacks on Stalin with words: "First, Stalin is disowned, now, little by little, it gets to prosecute socialism, the October Revolution, and in no time they will also want to prosecute Lenin and Marx." Shortly before death he suffered a heart attack.

Kaganovich died on July 25, 1991 at the age of 97, just before the events that resulted in the end of the USSR. He is buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery

Novodevichy Cemetery ( rus, Новоде́вичье кла́дбище, Novodevichye kladbishche) is a cemetery in Moscow. It lies next to the southern wall of the 16th-century Novodevichy Convent, which is the city's third most popular touris ...

in Moscow.

''The Wolf of the Kremlin''

In 1987, Americanjournalist

A journalist is an individual that collects/gathers information in form of text, audio, or pictures, processes them into a news-worthy form, and disseminates it to the public. The act or process mainly done by the journalist is called journalis ...

Stuart Kahan published a book entitled ''The Wolf of the Kremlin: The First Biography of L.M. Kaganovich, the Soviet Union's Architect of Fear'' (William Morrow & Co

William Morrow and Company is an American publishing company founded by William Morrow in 1926. The company was acquired by Scott Foresman in 1967, sold to Hearst Corporation in 1981, and sold to News Corporation (now News Corp) in 1999. The c ...

). In the book, Kahan made a series of claims about Kaganovich's working relationship with Stalin and his activities during the Ukrainian famine, and claimed to be Kaganovich's long-lost nephew. He also claimed to have interviewed Kaganovich personally and stated that Kaganovich admitted to being partially responsible for the death of Stalin in 1953 (supposedly by poisoning). A number of other unusual claims were made as well, including that Stalin was married to a sister of Kaganovich (supposedly named "Rosa") during the last year of his life and that Kaganovich (who was raised Jewish) was the architect of anti-Jewish pogroms.Kahan, Stuart. ''The Wolf of the Kremlin: The First Biography of L.M. Kaganovich, the Soviet Union's Architect of Fear'' (William Morrow & Co, 1987)

After ''The Wolf of the Kremlin'' was translated into Russian by Progress Publishers, and a chapter from it printed in the ''Nedelya'' (''Week'') newspaper in 1991, remaining members of Kaganovich's family composed the ''Statement of the Kaganovich Family'' in response. The statement disputed all of Kahan's claims.

Rosa Kaganovich, who the Statement of the Kaganovich Family says was fabricated, was referenced as Stalin's wife in the 1940s and 1950s by Western media including ''The New York Times'', ''Time (magazine), Time'' and ''Life (magazine), Life''. Although probably a hoax, the story of Rosa Kaganovich was also spread by notable Soviet defectors, including Trotsky, who alleged that "Stalin married the sister of Kaganovich, thereby presenting the latter with hopes for a promising future."

Personal life

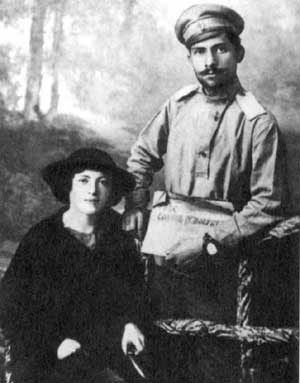

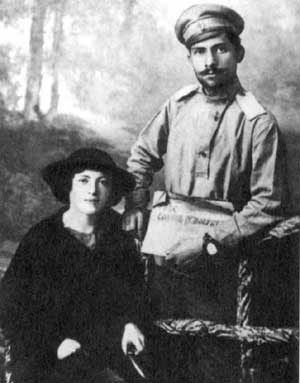

Kaganovich entered the workforce at the age of 13, an event which would shape his aesthetics and preferences through adulthood. Stalin himself confided to Kaganovich that the latter had a much greater fondness and appreciation for the proletariat. As his favorability with Stalin rose, Kaganovich felt compelled to rapidly fill the noticeable gaps in his education and upbringing. Stalin, upon noticing that Kaganovich could not use commas properly, gave Kaganovich three months' leave to undertake a blitz course in grammar. Kaganovich was married to Maria Markovna Kaganovich (née Privorotskaya) [1894-1961], a fellow assimilated History of the Jews in Kyiv, Kievan Jew who was part of the revolutionary effort since 1909. Mrs. Kaganovich spent many years as a powerful municipal official, directly ordering the demolition of the Iberian Gate and Chapel and

Kaganovich was married to Maria Markovna Kaganovich (née Privorotskaya) [1894-1961], a fellow assimilated History of the Jews in Kyiv, Kievan Jew who was part of the revolutionary effort since 1909. Mrs. Kaganovich spent many years as a powerful municipal official, directly ordering the demolition of the Iberian Gate and Chapel and Cathedral of Christ the Saviour

The Cathedral of Christ the Saviour ( rus, Храм Христа́ Спаси́теля, r=Khram Khristá Spasítelya, p=xram xrʲɪˈsta spɐˈsʲitʲɪlʲə) is a Russian Orthodox cathedral in Moscow, Russia, on the northern bank of the Moskv ...

. The couple had two children: a daughter, named Maya, and an adopted son, Yuri. Much attention has been devoted by historians to Kaganovich's Jewish peoplehood, Jewishness, and how it conflicted with Stalin's biases. Kaganovich frequently found it necessary to allow great cruelties to occur to his family to preserve Stalin's trust in him, such as allowing his brother to be coerced into suicide.

The Kaganovich family initially lived, as most high-level Soviet functionaries in the 1930s, a conservative lifestyle in modest conditions. This changed when Stalin entrusted the construction of the Moscow Metro to Kaganovich. The family moved into a luxurious apartment near ground zero (Sokolniki (Sokolnicheskaya line), Sokolniki station), located at 3 Pesochniy Pereulok (Sandy Lane). Kaganovich's apartment consisted of two floors (an extreme rarity in the USSR), a private access garage, and a designated space for butlers, security, and drivers.

Miscellaneous

Kaganovich is responsible for the use of the "eggs and omelette" metaphor in reference to the Great Terror ("Why wail over broken eggs when we are trying to make an omelette!"), a usage commonly attributed to Stalin himself.RUSSIA: Stalin's Omelette"''Time'' October 24, 1932 The expression was used in France as early as 1742, and then more famously in 1796 in reference to a War in the Vendée, French Royalist populist counter-revolution in the Vendée. According to ''Time'' magazine and some newspapers, Lazar Kaganovich's son Mikhail (named after Lazar's late brother) married Svetlana Alliluyeva, Svetlana Dzhugashvili, daughter of Joseph Stalin on 3 July 1951.Social Notes"

''Time'' July 23, 1951 Svetlana in her memoirs denies even the existence of Mikhail. Kaganovich is portrayed by Irish actor Dermot Crowley in the 2017 historical comedy ''The Death of Stalin''.

Decorations and awards

*Order of Lenin, four times *Order of the Red Banner of Labour (27 October, 1938) *Hero of Socialist Labour

The Hero of Socialist Labour (russian: links=no, Герой Социалистического Труда, Geroy Sotsialisticheskogo Truda) was an honorific title in the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact countries from 1938 to 1991. It repre ...

(5 November, 1943)

References

Further reading

* * Sheila Fitzpatrick, Fitzpatrick, S. (1996). ''Stalin's Peasants: Resistance and Survival in the Russian Village after Collectivization.'' New York: Oxford University Press. *——. (1999). ''Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s.'' New York: Oxford University Press. * Stephen Kotkin, Kotkin, S. (2017). ''Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929-1941''. New York: Random House. * Edvard Radzinsky, Radzinsky, Edvard, (1996) ''Stalin'', Doubleday (English translation edition), 1996. *Rees, E.A. ''Iron Lazar: A Political Biography of Lazar Kaganovich'' (Anthem Press; 2012) 373 pages; scholarly biography *Rubenstein, Joshua, ''The Last Days of Stalin'', (Yale University Press: 2016)External links

Profile at http://www.hrono.ru

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Kaganovich, Lazar 1893 births 1991 deaths Stalinism Anti-revisionists Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery Expelled members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union First convocation members of the Verkhovna Rada of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic First Secretaries of the Communist Party of Ukraine (Soviet Union) Genocide perpetrators Great Purge perpetrators Heroes of Socialist Labour Holodomor Jewish socialists Jewish Soviet politicians Old Bolsheviks People from Kiev Governorate People from Kyiv Oblast People's Commissariat of Heavy Industry People's commissars and ministers of the Soviet Union Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union members Recipients of the Order of Lenin Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Soviet people of World War II Ukrainian communists