Labyrinthodont on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

"Labyrinthodontia" (

The labyrinthodonts flourished for more than 200 million years. Particularly the early forms exhibited a lot of variation, yet there are still a few basic anatomical traits that make their fossils very distinct and easily recognizable in the field:

* Strongly folded tooth surface, involving infolding of the

The labyrinthodonts flourished for more than 200 million years. Particularly the early forms exhibited a lot of variation, yet there are still a few basic anatomical traits that make their fossils very distinct and easily recognizable in the field:

* Strongly folded tooth surface, involving infolding of the

With the exception of the snake-like aïstopods, the skulls of labyrinthodonts were massive. The broad head and short neck may have been a result of respiratory constraints. Their jaws were lined with small, sharp, conical teeth and the roof of the mouth bore larger tusk-like teeth. The teeth were replaced in waves that traveled from the front of the jaw to the back in such a way that every other tooth was mature, and the ones in between were young. All teeth were labyrinthodont. The sole exception were the chisel-like teeth of some of the advanced

With the exception of the snake-like aïstopods, the skulls of labyrinthodonts were massive. The broad head and short neck may have been a result of respiratory constraints. Their jaws were lined with small, sharp, conical teeth and the roof of the mouth bore larger tusk-like teeth. The teeth were replaced in waves that traveled from the front of the jaw to the back in such a way that every other tooth was mature, and the ones in between were young. All teeth were labyrinthodont. The sole exception were the chisel-like teeth of some of the advanced

Temnospondyli: Overview

from

PDF

Several groups are identified, but there is no consensus of their

Summary

Further complicating the picture is the amphibian larval-adult life cycle, with physical changes throughout life complicating phylogenetic analysis. The Labyrinthodontia appear to be composed of several nested

The early labyrinthodonts are known from the Devonian and possibly extending into the

The early labyrinthodonts are known from the Devonian and possibly extending into the

An early branch was the terrestrial reptile-like amphibians, variously called

An early branch was the terrestrial reptile-like amphibians, variously called

The most diverse group of labyrinthodonts was the

The most diverse group of labyrinthodonts was the  A temnospondyl's fore-foot had only four toes, and the hind-foot five, similar to the pattern seen in modern amphibians. Temnospondyls had a conservative vertebral column in which the pleurocentra remained small in primitive forms, vanishing entirely in the more advanced ones. The intercentra bore the weight of the animal, being large and forming a complete ring. All were more or less flat-headed with either strong or secondarily weak vertebrae and limbs. There were also fully aquatic forms, like the

A temnospondyl's fore-foot had only four toes, and the hind-foot five, similar to the pattern seen in modern amphibians. Temnospondyls had a conservative vertebral column in which the pleurocentra remained small in primitive forms, vanishing entirely in the more advanced ones. The intercentra bore the weight of the animal, being large and forming a complete ring. All were more or less flat-headed with either strong or secondarily weak vertebrae and limbs. There were also fully aquatic forms, like the

Phylogeny of Stegocephalians

from the

A small group of uncertain origin, the

A small group of uncertain origin, the

The labyrintodonts have their origin in the early middle Devonian (398–392 Mya) or possibly earlier. They evolved from a

The labyrintodonts have their origin in the early middle Devonian (398–392 Mya) or possibly earlier. They evolved from a

The end of the Devonian saw the

The end of the Devonian saw the

(abstract)

''

The herbivorous Diadectidae reached their maximum diversity in the late Carboniferous/early

The herbivorous Diadectidae reached their maximum diversity in the late Carboniferous/early

There is today a general consensus that all modern amphibians, the

There is today a general consensus that all modern amphibians, the

The fossil sequence leading from the early

The fossil sequence leading from the early

The term ''labyrinthodont'' was coined by

The term ''labyrinthodont'' was coined by

Palaeos.com Cladogram of Reptiliomorpha

{{Taxonbar, from=Q753235 Mesozoic amphibians Paleozoic amphibians Paraphyletic groups Taxa named by Richard Owen

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, 'maze-toothed') is an informal grouping of extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

predatory amphibians

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbo ...

which were major components of ecosystems in the late Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ...

and early Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

eras (about 390 to 150 million years ago). Traditionally considered a subclass of the class Amphibia, modern classification systems recognize that labyrinthodonts are not a formal natural group (clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English ter ...

) exclusive of other tetrapods

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids (reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids ( pelycosaurs, extinct therapsi ...

. Instead, they consistute an evolutionary grade (a paraphyletic group

In taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

), ancestral to living tetrapods such as lissamphibians (modern amphibians) and amniotes

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are dis ...

(reptiles

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates ( lizards and snakes) and rhynchoceph ...

, mammals

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur o ...

, and kin). "Labyrinthodont"-grade vertebrates evolved from lobe-finned fishes in the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wh ...

, though a formal boundary between fish and amphibian is difficult to define at this point in time.

"Labyrinthodont" generally refers to extinct four-limbed tetrapods with a large body size and a crocodile

Crocodiles (family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to include all extant me ...

-like lifestyle. The name describes the pattern of infolding of the dentin

Dentin () (American English) or dentine ( or ) (British English) ( la, substantia eburnea) is a calcified tissue of the body and, along with enamel, cementum, and pulp, is one of the four major components of teeth. It is usually covered by e ...

and enamel of the teeth, which are often the only part of the creatures that fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

ize. They are also distinguished by a broad, strongly-built skull roof

The skull roof, or the roofing bones of the skull, are a set of bones covering the brain, eyes and nostrils in bony fishes and all land-living vertebrates. The bones are derived from dermal bone and are part of the dermatocranium.

In compar ...

composed of many small heavily-textured skull bones. "Labyrinthodonts" generally have complex multi-part vertebrae, and several classification schemes have utilized vertebrae to define subgroups.

Because labyrinthodonts do not form a monophyletic group, many modern researchers have abandoned the term. However, some have continued to use the group in their classifications, at least informally, pending more detailed study of their relationships. Many authors prefer to simply use the term tetrapod

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids ( pelycosaurs, extinct t ...

, while others have re-defined the previously obsolete term Stegocephalia

Stegocephali (often spelled Stegocephalia) is a group containing all four-limbed vertebrates. It is equivalent to a broad definition of Tetrapoda: under this broad definition, the term "tetrapod" applies to any animal descended from the first ve ...

("roof heads") as a cladistic

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived char ...

alternative to "Labyrinthodontia" or "Tetrapoda".

Labyrinthodont traits

The labyrinthodonts flourished for more than 200 million years. Particularly the early forms exhibited a lot of variation, yet there are still a few basic anatomical traits that make their fossils very distinct and easily recognizable in the field:

* Strongly folded tooth surface, involving infolding of the

The labyrinthodonts flourished for more than 200 million years. Particularly the early forms exhibited a lot of variation, yet there are still a few basic anatomical traits that make their fossils very distinct and easily recognizable in the field:

* Strongly folded tooth surface, involving infolding of the dentin

Dentin () (American English) or dentine ( or ) (British English) ( la, substantia eburnea) is a calcified tissue of the body and, along with enamel, cementum, and pulp, is one of the four major components of teeth. It is usually covered by e ...

and enamel of the teeth. The cross section resembles a classical labyrinth

In Greek mythology, the Labyrinth (, ) was an elaborate, confusing structure designed and built by the legendary artificer Daedalus for King Minos of Crete at Knossos. Its function was to hold the Minotaur, the monster eventually killed by ...

(or maze

A maze is a path or collection of paths, typically from an entrance to a goal. The word is used to refer both to branching tour puzzles through which the solver must find a route, and to simpler non-branching ("unicursal") patterns that le ...

), hence the name of the group.

* Massive skull roof, with openings only for the nostrils, eyes and a parietal eye

A parietal eye, also known as a third eye or pineal eye, is a part of the epithalamus present in some vertebrates. The eye is located at the top of the head, is photoreceptive and is associated with the pineal gland, regulating circadian rhyth ...

, similar to the structure of the "anapsid

An anapsid is an amniote whose skull lacks one or more skull openings (fenestra, or fossae) near the temples. Traditionally, the Anapsida are the most primitive subclass of amniotes, the ancestral stock from which Synapsida and Diapsida evolv ...

" reptiles. With the exception of the later more reptile-like forms, the skull was rather flat and strongly ornamented with presumably tough dermal covering, accounting for an older term for the group: "Stegocephalia".

* Otic notch

Otic notches are invaginations in the posterior margin of the skull roof, one behind each orbit. Otic notches are one of the features lost in the evolution of amniotes from their tetrapod ancestors.

The notches have been interpreted as part of an ...

behind each eye at the back edge of the skull. In earlier fully aquatic forms such as ''Ichthyostega

''Ichthyostega'' (from el, ἰχθῦς , 'fish' and el, στέγη , 'roof') is an extinct genus of limbed tetrapodomorphs from the Late Devonian of Greenland. It was among the earliest four-limbed vertebrates in the fossil record, and was o ...

'', it may have formed an open spiracle. In later terrestrial forms such as ''Seymouria

''Seymouria'' is an extinct genus of seymouriamorpha, seymouriamorph from the Early Permian of North America and Europe. Although they were amphibians (in a biological sense), ''Seymouria'' were well-adapted to life on land, with many reptile, re ...

'', it may possibly have held a tympanic membrane

In the anatomy of humans and various other tetrapods, the eardrum, also called the tympanic membrane or myringa, is a thin, cone-shaped membrane that separates the external ear from the middle ear. Its function is to transmit sound from the a ...

(eardrum). Laurin M. (1998): The importance of global parsimony and historical bias in understanding tetrapod evolution. Part I-systematics, middle ear evolution, and jaw suspension. ''Annales des Sciences Naturelles, Zoologie, Paris'', 13e Série 19: pp 1–42.

* Complex vertebrae

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristi ...

made of multiple components: an intercentrum (wedge-shaped front lower piece), two pleurocentra (upper rear piece), and a vertebral arch

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic ...

/spine (upper projection). The relative development and shape of the elements is highly variable.

The labyrinthodonts in life

General build

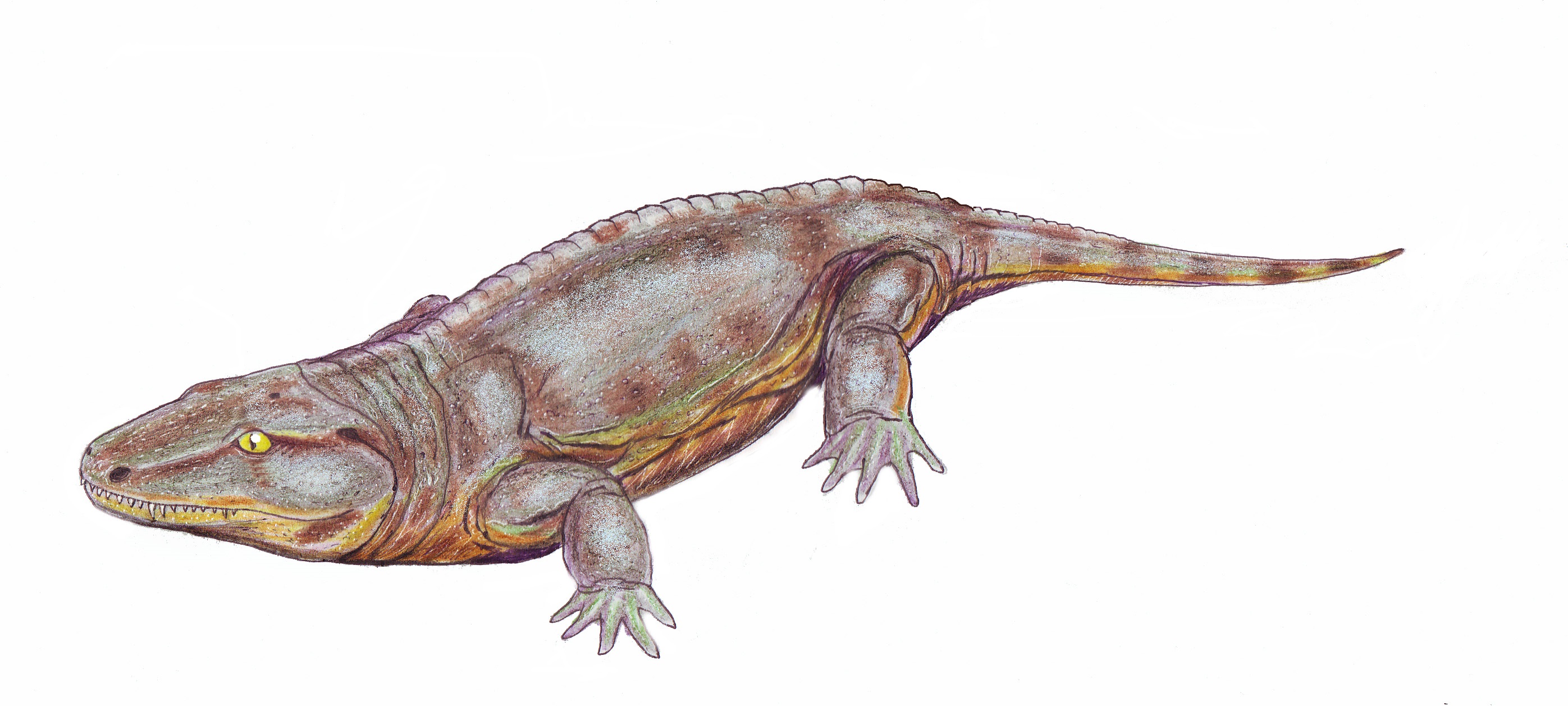

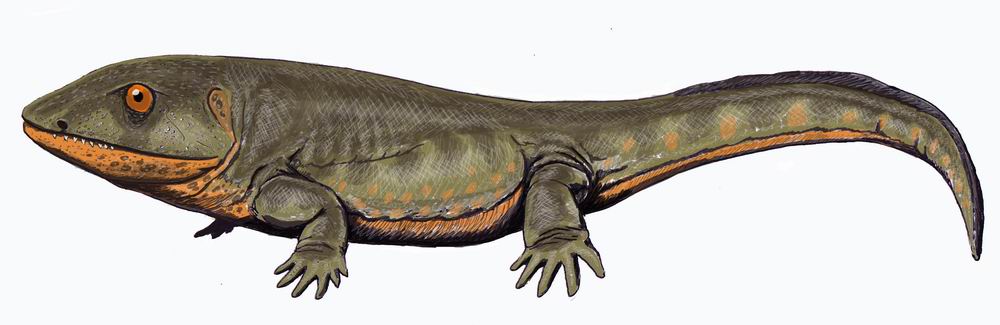

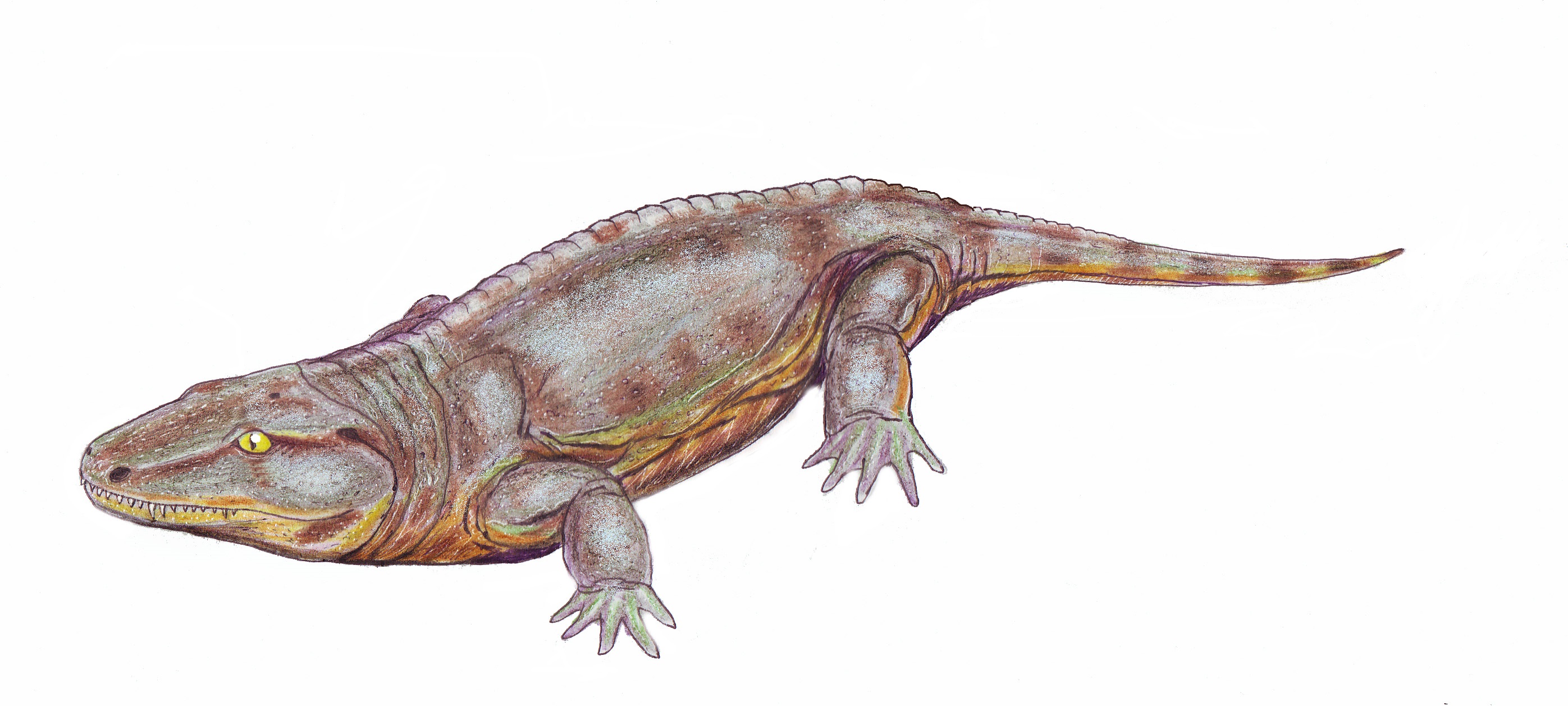

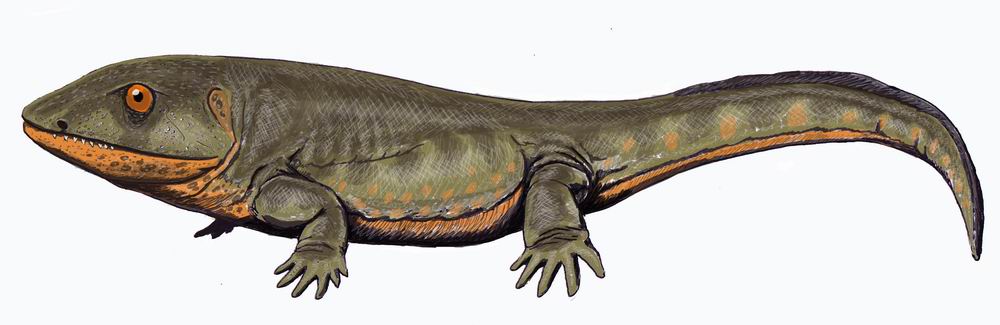

Labyrinthodonts were generally amphibian-like in build. They were short-legged and mostly large headed, with moderately short to long tails. Many groups, and all the early forms, were large animals. Primitive members of all labyrinthodont groups were probably true water predators, and various degrees of amphibious, semi-aquatic and semi terrestrial modes of living arose independently in different groups.Clack, J. A. (2002): Gaining ground: the origin and evolution of tetrapods. ''Indiana University Press'', Bloomington, Indiana. 369 pp Some lineages remained waterbound or became secondarily fully aquatic with reduced limbs and elongated, eel-like bodies.Skull

With the exception of the snake-like aïstopods, the skulls of labyrinthodonts were massive. The broad head and short neck may have been a result of respiratory constraints. Their jaws were lined with small, sharp, conical teeth and the roof of the mouth bore larger tusk-like teeth. The teeth were replaced in waves that traveled from the front of the jaw to the back in such a way that every other tooth was mature, and the ones in between were young. All teeth were labyrinthodont. The sole exception were the chisel-like teeth of some of the advanced

With the exception of the snake-like aïstopods, the skulls of labyrinthodonts were massive. The broad head and short neck may have been a result of respiratory constraints. Their jaws were lined with small, sharp, conical teeth and the roof of the mouth bore larger tusk-like teeth. The teeth were replaced in waves that traveled from the front of the jaw to the back in such a way that every other tooth was mature, and the ones in between were young. All teeth were labyrinthodont. The sole exception were the chisel-like teeth of some of the advanced herbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpar ...

diadectomorphs. The skull had prominent otic notches behind each eye and a parietal eye

A parietal eye, also known as a third eye or pineal eye, is a part of the epithalamus present in some vertebrates. The eye is located at the top of the head, is photoreceptive and is associated with the pineal gland, regulating circadian rhyth ...

.

Post-cranial skeleton

Thevertebrae

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristi ...

were complex and not particularly strong, consisting of numerous, often poorly ossified elements. The long bones

The long bones are those that are longer than they are wide. They are one of five types of bones: long, short, flat, irregular and sesamoid. Long bones, especially the femur and tibia, are subjected to most of the load during daily activities a ...

of the limbs were short and broad and the ankle had limited mobility and the toes lacked claw

A claw is a curved, pointed appendage found at the end of a toe or finger in most amniotes (mammals, reptiles, birds). Some invertebrates such as beetles and spiders have somewhat similar fine, hooked structures at the end of the leg or tarsus ...

s, limiting the amount of traction the feet could produce. This would have made most labyrinthodonts slow and clumsy on land. In adulthood, most of the larger species were likely confined to water. Some late Paleozoic groups, particularly microsaurs and seymouriamorphs

Seymouriamorpha were a small but widespread group of limbed vertebrates (tetrapods). They have long been considered reptiliomorphs, and most paleontologists may still accept this point of view, but some analyses suggest that seymouriamorphs are s ...

, were small to medium-sized and appear to have been competent terrestrial animals. The advanced diadectomorphs from the Late Carboniferous

Late may refer to:

* LATE, an acronym which could stand for:

** Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, a proposed form of dementia

** Local-authority trading enterprise, a New Zealand business law

** Local average treatment effe ...

and Early Permian 01 or '01 may refer to:

* The year 2001, or any year ending with 01

* The month of January

* 1 (number)

Music

* 01'' (Richard Müller album), 2001

* ''01'' (Son of Dave album), 2000

* ''01'' (Urban Zakapa album), 2011

* ''O1'' (Hiroyuki Sawan ...

were fully terrestrial with stout skeletons, and were the heaviest land animals of their time. The Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

labyrinthodonts were primarily aquatic with increasingly cartilaginous skeleton.White, T. & Kazlev, M. A. (2006)Temnospondyli: Overview

from

Palaeos Palaeos.com is a web site on biology, paleontology, phylogeny and geology and which covers the history of Earth. The site is well respected and has been used as a reference by professional paleontologists such as Michael J. Benton, the professor of ...

website

Sensory apparatus

The eyes of most labyrinthodonts were situated at the top of the skull, offering good vision upwards, but very little lateral vision. Theparietal eye

A parietal eye, also known as a third eye or pineal eye, is a part of the epithalamus present in some vertebrates. The eye is located at the top of the head, is photoreceptive and is associated with the pineal gland, regulating circadian rhyth ...

was prominent, although there is uncertainty as to whether it was a true image producing organ or one that could only register light and dark, like that of the modern tuatara

Tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') are reptiles endemic to New Zealand. Despite their close resemblance to lizards, they are part of a distinct lineage, the order Rhynchocephalia. The name ''tuatara'' is derived from the Māori language and m ...

.

Most labyrinthodonts had special sense organs in the skin, forming a lateral line

The lateral line, also called the lateral line organ (LLO), is a system of sensory organs found in fish, used to detect movement, vibration, and pressure gradients in the surrounding water. The sensory ability is achieved via modified epithelial ...

organ for perception of water flow and pressure, like those found in fish

Fish are Aquatic animal, aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack Limb (anatomy), limbs with Digit (anatomy), digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and Chondrichthyes, cartilaginous and bony fish as we ...

and a number of modern amphibians. This would enable them to pick up the vibration of their prey and other waterborne sounds while hunting in murky, weed filled waters. Early labyrinthodont groups had massive stapes

The ''stapes'' or stirrup is a bone in the middle ear of humans and other animals which is involved in the conduction of sound vibrations to the inner ear. This bone is connected to the oval window by its annular ligament, which allows the foo ...

, likely primarily anchoring the brain case to the skull roof

The skull roof, or the roofing bones of the skull, are a set of bones covering the brain, eyes and nostrils in bony fishes and all land-living vertebrates. The bones are derived from dermal bone and are part of the dermatocranium.

In compar ...

. It is a question of some doubt whether early terrestrial labyrinthodonts had the stapes connected to a tympanum covering their otic notch, and if they had an aerial sense of hearing at all. The tympanum in anurans and amniote

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are dis ...

s appear to have evolved separately, indicating most, if not all, labyrinthodonts were unable to pick up airborne sound.

Respiration

The early labyrinthodonts possessed well developed internal gills as well as primitivelung

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of ...

s, derived from the swim bladder

The swim bladder, gas bladder, fish maw, or air bladder is an internal gas-filled organ that contributes to the ability of many bony fish (but not cartilaginous fish) to control their buoyancy, and thus to stay at their current water depth wit ...

s of their ancestors. They could breathe air, which would have been a great advantage for residents of warm shoal

In oceanography, geomorphology, and geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material and rises from the bed of a body of water to near the surface. It ...

s with low oxygen levels in the water. There was no diaphragma and the ribs in many forms were too short or spaced too closely to aid in expanding the lungs. Likely air was inflated into the lungs by contractions of a throat sac against the skull floor like in modern amphibians, which may be the reason for the retention of the very flat skull in later forms. Exhalation with the aid of the ribs probably evolved only in the line leading to amniote

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are dis ...

s. Many aquatic forms retained their larval gills in adulthood.

With the high atmospheric oxygen and carbon dioxide pressure, particularly during the Carboniferous, the primitive throat sac breathing would have been sufficient for obtaining oxygen even for the large forms. Getting rid of carbon dioxide would present a greater problem on land, and the larger labyrinthodonts probably combined a high tolerance for blood carbonic acid with returning to the water to dissipate the carbon dioxide through the skin. The loss of the armour of rhomboid

Traditionally, in two-dimensional geometry, a rhomboid is a parallelogram in which adjacent sides are of unequal lengths and angles are non-right angled.

A parallelogram with sides of equal length (equilateral) is a rhombus but not a rhomboi ...

scales

Scale or scales may refer to:

Mathematics

* Scale (descriptive set theory), an object defined on a set of points

* Scale (ratio), the ratio of a linear dimension of a model to the corresponding dimension of the original

* Scale factor, a number w ...

of their piscine ancestors allowed for this as well as additional respiration through the skin as in modern amphibians.

Hunting and feeding

Like their sarcopterygian ancestors, the labyrinthodonts were carnivorous. The rather broad, flat skulls and hence short jaw muscle would however not allow them to open their mouth to any great extent. Likely the majority of them would employ a sit-and-wait strategy, similar to that of many modern amphibians. When suitable prey swam or walked within reach, the jaw would slam shut, the palatine tusks stabbing the hapless victim. The strain put on the teeth by this mode of feeding may have been the reason for the reinforcing labyrinthodont enamel typifying the group. Swallowing was done by tipping the head back, as seen in many modern amphibians and incrocodile

Crocodiles (family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to include all extant me ...

s.

Evolution of a deeper skull, better jaw control and a reduction of the palatine tusks is only seen in the more advanced reptile-like forms, possibly in connection with the evolution of more effective breathing, allowing for a more refined hunting style.

Reproduction

The labyrinthodonts had an amphibious reproduction — they laid eggs in water, where they would hatch totadpole

A tadpole is the larval stage in the biological life cycle of an amphibian. Most tadpoles are fully aquatic, though some species of amphibians have tadpoles that are terrestrial. Tadpoles have some fish-like features that may not be found ...

s. They would remain in water throughout the larval stage until metamorphosis

Metamorphosis is a biological process by which an animal physically develops including birth or hatching, involving a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell growth and differentiation. Some inse ...

. Only the metamorphosed individuals would eventually venture onto land on occasion. Fossil tadpoles from several species are known, as are neotenic

Neoteny (), also called juvenilization,Montagu, A. (1989). Growing Young. Bergin & Garvey: CT. is the delaying or slowing of the physiological, or somatic, development of an organism, typically an animal. Neoteny is found in modern humans compare ...

adults with feathery external gills External gills are the gills of an animal, most typically an amphibian, that are exposed to the environment, rather than set inside the pharynx and covered by gill slits, as they are in most fishes. Instead, the respiratory organs are set on a fril ...

similar to those found in modern lissamphibia

The Lissamphibia is a group of tetrapods that includes all modern amphibians. Lissamphibians consist of three living groups: the Salientia (frogs, toads, and their extinct relatives), the Caudata (salamanders, newts, and their extinct relativ ...

n tadpoles and in the fry of lungfish

Lungfish are freshwater vertebrates belonging to the order Dipnoi. Lungfish are best known for retaining ancestral characteristics within the Osteichthyes, including the ability to breathe air, and ancestral structures within Sarcopterygii, i ...

and bichir

Bichirs and the reedfish comprise Polypteridae , a family of archaic ray-finned fishes and the only family in the order Polypteriformes .Helfman GS, Collette BB, Facey DE, Bowen BW. 2009. The Diversity of Fishes. West Sussex, UK: Blackwell Pu ...

s. The existence of a larval stage as the primitive condition in all groups of labyrinthodonts can be fairly safely assumed, in that tadpoles of ''Discosauriscus

''Discosauriscus'' was a small seymouriamorph which lived in what is now Central and Western Europe in the Early Permian Period. Its best fossils have been found in the Broumov and Bačov Formations of Boskovice Furrow, in the Czech Republic. ...

'', a close relative of the amniote

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are dis ...

s, are known. Špinar, Z. V. (1952): Revision of some Morovian Discosauriscidae. ''Rozpravy ustrededniho Uštavu Geologickeho'' no 15, pp 1–160

Groups of labyrinthodonts

The systematic placement of groups within Labyrinthodontia is notoriously fickle. Carroll, R. L. (2001): The origin and early radiation of terrestrial vertebrates. ''Journal of Paleontology'' no 75(6), pp 1202–121Several groups are identified, but there is no consensus of their

phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups ...

relationship. Many key groups were small with moderately ossified skeletons, and there is a gap in the fossil record in the early Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian Period million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Permian Period, million years ago. The name ''Carboniferou ...

(the "Romer's gap

Romer's gap is an example of an apparent gap in the tetrapod fossil record used in the study of evolutionary biology. Such gaps represent periods from which excavators have not yet found relevant fossils. Romer's gap is named after paleontologist ...

") when most of the groups appear to have evolved. Carroll, R. L. (1995): Problems of the phylogenetic analysis of Paleozoic choanates. ''Bulletin du Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle de Paris'', 4ème série 17: pp 389–445Summary

Further complicating the picture is the amphibian larval-adult life cycle, with physical changes throughout life complicating phylogenetic analysis. The Labyrinthodontia appear to be composed of several nested

clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English ter ...

s. The two best understood groups, the Ichthyostegalia

Ichthyostegalia is an order of extinct amphibians, representing the earliest landliving vertebrates. The group is thus an evolutionary grade rather than a clade. While the group are recognized as having feet rather than fins, most, if not all, ...

and the reptile-like amphibians have from the outset been known to be paraphyletic

In taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In ...

. Tellingly, labyrinthodont systematics was the subject of the inaugural meeting of International Society for Phylogenetic Nomenclature.

Ichthyostegalia

The early labyrinthodonts are known from the Devonian and possibly extending into the

The early labyrinthodonts are known from the Devonian and possibly extending into the Romer's Gap

Romer's gap is an example of an apparent gap in the tetrapod fossil record used in the study of evolutionary biology. Such gaps represent periods from which excavators have not yet found relevant fossils. Romer's gap is named after paleontologist ...

of the early Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian Period million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Permian Period, million years ago. The name ''Carboniferou ...

. These labyrinthodonts are often grouped together as the order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

Ichthyostegalia

Ichthyostegalia is an order of extinct amphibians, representing the earliest landliving vertebrates. The group is thus an evolutionary grade rather than a clade. While the group are recognized as having feet rather than fins, most, if not all, ...

, though the group is an evolutionary grade rather than a clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English ter ...

. Ichthyostegalians were predominantly aquatic and most show evidence of functional internal gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they ar ...

s throughout life, and probably only occasionally ventured onto land. Their polydactylous feet had more than the usual five digits for tetrapods and were paddle-like. The tail bore true fin rays like those found in fish. The vertebrae

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristi ...

were complex and rather weak. At the close of the Devonian, forms with progressively stronger legs and vertebrae evolved, and the later groups lacked functional gills as adults. All were however predominantly aquatic and some spent all or nearly all their lives in water.

Reptile-like amphibians

An early branch was the terrestrial reptile-like amphibians, variously called

An early branch was the terrestrial reptile-like amphibians, variously called Anthracosauria

Anthracosauria is an order of extinct reptile-like amphibians (in the broad sense) that flourished during the Carboniferous and early Permian periods, although precisely which species are included depends on one's definition of the taxon. "Anthra ...

or Reptiliomorpha

Reptiliomorpha (meaning reptile-shaped; in PhyloCode known as ''Pan-Amniota'') is a clade containing the amniotes and those tetrapods that share a more recent common ancestor with amniotes than with living amphibians (lissamphibians). It was def ...

. ''Tulerpeton

''Tulerpeton'' is an extinct genus of Devonian four-limbed vertebrate, known from a fossil that was found in the Tula Region of Russia at a site named Andreyevka. This genus and the closely related ''Acanthostega'' and ''Ichthyostega'' represen ...

'' has been suggested as the earliest member of the line, indicating the split may have happened before the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wh ...

-Carboniferous transition. Their skulls were relatively deep and narrow compared to other labyrinthodonts. Front and hind feet bore five digits on most forms. Several of the early groups are known from brackish or even marine environments, having returned to a more or less fully aquatic mode of living.

With the exception of the diadectomorphs, the terrestrial forms were moderately sized creatures that appeared in the early Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian Period million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Permian Period, million years ago. The name ''Carboniferou ...

. The vertebrae

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristi ...

of the group foreshadowed that of primitive reptiles, with small pleurocentra, which grew and fused to become the true centrum in later vertebrates. The most well known genus is ''Seymouria

''Seymouria'' is an extinct genus of seymouriamorpha, seymouriamorph from the Early Permian of North America and Europe. Although they were amphibians (in a biological sense), ''Seymouria'' were well-adapted to life on land, with many reptile, re ...

''. Some members of the most advanced group, the Diadectomorpha, were herbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpar ...

and grew to several meters in length, with great, barrel-shaped bodies. Small relatives of the diadectomorphs gave rise to the first reptile

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates ( lizards and snakes) and rhynchocephalia ...

s in the Late Carboniferous

Late may refer to:

* LATE, an acronym which could stand for:

** Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, a proposed form of dementia

** Local-authority trading enterprise, a New Zealand business law

** Local average treatment effe ...

.

Temnospondyli

The most diverse group of labyrinthodonts was the

The most diverse group of labyrinthodonts was the Temnospondyli

Temnospondyli (from Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') is a diverse order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished worldwide during the Carb ...

. Temnospondyls appeared in the early Carboniferous

Early may refer to:

History

* The beginning or oldest part of a defined historical period, as opposed to middle or late periods, e.g.:

** Early Christianity

** Early modern Europe

Places in the United States

* Early, Iowa

* Early, Texas

* Ear ...

and came in all sizes, from small salamander-like Stereospondyli

The Stereospondyli are a group of extinct temnospondyl amphibians that existed primarily during the Mesozoic period. They are known from all seven continents and were common components of many Triassic ecosystems, likely filling a similar ecologi ...

that scurried along the waters edge and undergrowth, to giant, well armoured Archegosauroidea

Archegosauroidea is an extinct superfamily of Permian temnospondyls. The superfamily is assigned to the clade Stereospondylomorpha and is the sister taxon to the suborder Stereospondyli. It includes the families Actinodontidae and Archegosaurid ...

that looked more like crocodiles. ''Prionosuchus

''Prionosuchus'' is an extinct genus of large temnospondyl. A single species ''P. plummeri'', is recognized from the Early Permian (some time between 299 and 272 million years ago). Its fossils have been found in what is now northeastern Brazil.

...

'' was an exceptionally large member of the Archegosauridae, estimated to have been up to 9 meters long, it is the largest amphibian ever known to have lived. Temnospondyls typically had large heads and heavy shoulder girdles with moderately long tails. A fossil trackway from Lesotho shows larger forms dragged themselves by the front limbs over slippery surfaces with limited sideways movement of the body, very unlike modern salamanders.

A temnospondyl's fore-foot had only four toes, and the hind-foot five, similar to the pattern seen in modern amphibians. Temnospondyls had a conservative vertebral column in which the pleurocentra remained small in primitive forms, vanishing entirely in the more advanced ones. The intercentra bore the weight of the animal, being large and forming a complete ring. All were more or less flat-headed with either strong or secondarily weak vertebrae and limbs. There were also fully aquatic forms, like the

A temnospondyl's fore-foot had only four toes, and the hind-foot five, similar to the pattern seen in modern amphibians. Temnospondyls had a conservative vertebral column in which the pleurocentra remained small in primitive forms, vanishing entirely in the more advanced ones. The intercentra bore the weight of the animal, being large and forming a complete ring. All were more or less flat-headed with either strong or secondarily weak vertebrae and limbs. There were also fully aquatic forms, like the Dvinosauria

Dvinosaurs are one of several new clades of Temnospondyl amphibians named in the phylogenetic review of the group by Yates and Warren 2000. They represent a group of primitive semi-aquatic to completely aquatic amphibians, and are known from t ...

, and even marine forms such as the Trematosauridae

Trematosauridae are a family of large marine temnospondyl amphibians with many members. They first appeared during the Induan age of the Early Triassic, and existed until around the Carnian stage of the Late Triassic, although by then they wer ...

. The Temnospondyli may have given rise to the modern frog

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely Carnivore, carnivorous group of short-bodied, tailless amphibians composing the order (biology), order Anura (ανοὐρά, literally ''without tail'' in Ancient Greek). The oldest fossil "proto-f ...

s and salamander

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All t ...

s in the late Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleo ...

or early Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest per ...

.Laurin, M. (1996)Phylogeny of Stegocephalians

from the

Tree of Life Web Project

The Tree of Life Web Project is an Internet project providing information about the diversity and phylogeny of life on Earth.

This collaborative peer reviewed project began in 1995, and is written by biologists from around the world. The site ...

Lepospondyli

A small group of uncertain origin, the

A small group of uncertain origin, the Lepospondyli

Lepospondyli is a diverse taxon of early tetrapods. With the exception of one late-surviving lepospondyl from the Late Permian of Morocco ('' Diplocaulus minumus''), lepospondyls lived from the Early Carboniferous ( Mississippian) to the Early Pe ...

evolved mostly small species that can be found in European and North American Carboniferous and early Permian strata. They are characterized by simple spool-shaped vertebrae formed from a single element, rather than the complex system found in other labyrinthodont groups. Most were aquatic and external gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they ar ...

s are sometimes found preserved. The Leposondyli were generally salamander-like, but one group, the Aïstopoda

Aistopoda (Greek for " avingnot-visible feet") is an order of highly specialised snake-like stegocephalians known from the Carboniferous and Early Permian of Europe and North America, ranging from tiny forms only , to nearly in length. They fir ...

, was snakelike with flexible, reduced skulls, though whether the families belong with the other lepospondyls is uncertain. Some microsaur

Microsauria ("small lizards") is an extinct, possibly polyphyletic order of tetrapods from the late Carboniferous and early Permian periods. It is the most diverse and species-rich group of lepospondyls. Recently, Microsauria has been considered ...

lepospondyls were squat and short-tailed and appear to have been well adapted to terrestrial life. The best known genus is '' Diplocaulus'', a nectridea

Nectridea is the name of an extinct order of lepospondyl tetrapods from the Carboniferous and Permian periods, including animals such as '' Diplocaulus''. In appearance, they would have resembled modern newts or aquatic salamanders, although the ...

n with a boomerang

A boomerang () is a thrown tool, typically constructed with aerofoil sections and designed to spin about an axis perpendicular to the direction of its flight. A returning boomerang is designed to return to the thrower, while a non-returning ...

-shaped head.

The position of Lepospondyli in relation to other labyrinthodont groups is uncertain, and it is sometimes classified as a separate subclass.Kent, G. C. & Miller, L. (1997): Comparative anatomy of the vertebrates. 8th edition. Wm. C. Brown Publishers. Dubuque. 487 pages. The teeth were not labyrinthodont, and the group has classically been seen as separate from the Labyrinthodontia. There is some doubt as to whether the lepospondyls form a phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups ...

unit at all, or is a wastebin taxon containing the padamorphic forms and tadpoles

A tadpole is the larval stage in the biological life cycle of an amphibian. Most tadpoles are fully aquatic, though some species of amphibians have tadpoles that are terrestrial. Tadpoles have some fish-like features that may not be found in ...

of other labyrinthodonts, notably the reptile-like amphibians, or even very small primitive amniotes with reduced skulls.

Evolutionary history

The labyrintodonts have their origin in the early middle Devonian (398–392 Mya) or possibly earlier. They evolved from a

The labyrintodonts have their origin in the early middle Devonian (398–392 Mya) or possibly earlier. They evolved from a bony fish

Osteichthyes (), popularly referred to as the bony fish, is a diverse superclass of fish that have skeletons primarily composed of bone tissue. They can be contrasted with the Chondrichthyes, which have skeletons primarily composed of cartil ...

group: the fleshy-finned Rhipidistia. The only other living group of Rhipidistans alive today are the lungfish

Lungfish are freshwater vertebrates belonging to the order Dipnoi. Lungfish are best known for retaining ancestral characteristics within the Osteichthyes, including the ability to breathe air, and ancestral structures within Sarcopterygii, i ...

, the sister group of the landliving vertebrates. Earliest traces of the land-living forms are fossil trackways from Zachełmie quarry, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, dated to 395 million years ago, attributed to an animal with feet very similar to Ichthyostega

''Ichthyostega'' (from el, ἰχθῦς , 'fish' and el, στέγη , 'roof') is an extinct genus of limbed tetrapodomorphs from the Late Devonian of Greenland. It was among the earliest four-limbed vertebrates in the fossil record, and was o ...

.

Swamp predators

By the late Devonian, landplant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae excl ...

s had stabilized freshwater habitats, allowing the first wetland

A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). Flooding results in oxygen-free (Anoxic waters, anoxic) processes prevailing, especially in t ...

ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syst ...

s to develop, with increasingly complex food web

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Another name for food web is consumer-resource system. Ecologists can broadly lump all life forms into one o ...

s that afforded new opportunities. The early labyrinthodonts were wholly aquatic, hunting in shallow water along tidal shores or weed filled tidal channels. From their piscine ancestors, they had inherited swim bladder

The swim bladder, gas bladder, fish maw, or air bladder is an internal gas-filled organ that contributes to the ability of many bony fish (but not cartilaginous fish) to control their buoyancy, and thus to stay at their current water depth wit ...

s that opened to the esophagus

The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to t ...

and were capable of functioning as lungs

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either si ...

(a condition still found in lungfish and some physostome

Physostomes are fishes that have a pneumatic duct connecting the gas bladder to the alimentary canal. This allows the gas bladder to be filled or emptied via the mouth. This not only allows the fish to fill their bladder by gulping air, but also t ...

ray-finned fishes), allowing them to hunt in stagnant water or in waterways where rotting vegetation would have lowered oxygen content. The earliest forms, such as ''Acanthostega

''Acanthostega'' (meaning "spiny roof") is an extinct genus of stem-tetrapod, among the first vertebrate animals to have recognizable limbs. It appeared in the late Devonian period (Famennian age) about 365 million years ago, and was anatomic ...

'', had vertebrae and limbs quite unsuited to life on land. This is in contrast to the earlier view that fish had first invaded the land—either in search of prey like modern mudskipper

Mudskippers are any of the 23 extant species of amphibious fish from the subfamily Oxudercinae of the goby family Oxudercidae. They are known for their unusual body shapes, preferences for semiaquatic habitats, limited terrestrial locomotion ...

s, or to find water when the pond they lived in dried out. Early fossil tetrapods have been found in marine sediments, suggesting marine and brackish areas were their primary habitat. This is further corroborated by fossils of early labyrinthodonts being found scattered all around the world, indicating they must have spread by following the coastal lines rather than through freshwater only.

The first labyrinthodonts were all large to moderately large animals, and would have suffered considerable problems on land despite their members ending in toes rather than fin-rays. While they retained gills and fish-like skulls and tails with fin ray

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as see ...

s, the early forms can readily be separated from Rhipidistan fish by the cleithrum

The cleithrum (plural cleithra) is a membrane bone which first appears as part of the skeleton in primitive bony fish, where it runs vertically along the scapula. Its name is derived from Greek κλειθρον = "key (lock)", by analogy with "cla ...

/scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eith ...

complex being separate from the skull to form a pectoral girdle

The shoulder girdle or pectoral girdle is the set of bones in the appendicular skeleton which connects to the arm on each side. In humans it consists of the clavicle and scapula; in those species with three bones in the shoulder, it consists of ...

able to carry the weight of the front end of the animals. They were all carnivorous

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other ...

, initially eating fish and possibly going ashore to feed off washed up carrion of sea animals caught in tidal ponds, only later turning into predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill t ...

s of the large invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chorda ...

s of the Devonian at the waters edge. The various early forms are for convenience grouped together as Ichthyostegalia

Ichthyostegalia is an order of extinct amphibians, representing the earliest landliving vertebrates. The group is thus an evolutionary grade rather than a clade. While the group are recognized as having feet rather than fins, most, if not all, ...

.

While the body shape and proportions of the ichthyostegalians went largely unchanged throughout their evolutionary history, the limbs underwent a rapid evolution. The proto-tetrapods like from ''Elginerpeton

''Elginerpeton'' is a genus of stegocephalian (stem-tetrapod), the fossils of which were recovered from Scat Craig, Morayshire in the UK, from rocks dating to the late Devonian Period (Early Famennian stage, 368 million years ago). The only know ...

'' and ''Tiktaalik

''Tiktaalik'' (; Inuktitut ) is a monospecific genus of extinct sarcopterygian (lobe-finned fish) from the Late Devonian Period, about 375 Mya (million years ago), having many features akin to those of tetrapods (four-legged animals). It may ha ...

'' had extremities ending in fin-rays with no clear fingers, primarily suited for movement in open water, but also capable of propelling the animal across sandbanks and through vegetation filled waterways. ''Ichthyostega

''Ichthyostega'' (from el, ἰχθῦς , 'fish' and el, στέγη , 'roof') is an extinct genus of limbed tetrapodomorphs from the Late Devonian of Greenland. It was among the earliest four-limbed vertebrates in the fossil record, and was o ...

'' and ''Acanthostega

''Acanthostega'' (meaning "spiny roof") is an extinct genus of stem-tetrapod, among the first vertebrate animals to have recognizable limbs. It appeared in the late Devonian period (Famennian age) about 365 million years ago, and was anatomic ...

'' had paddle-like polydactyl feet with stout bony toes that also would have enabled them to drag themselves across land. The aquatic ichthyostegalians flourished in tidal channels and swampland through the remainder of the Devonian, only to disappear from the fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

record at the transition to the Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian Period million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Permian Period, million years ago. The name ''Carboniferou ...

.

Onto land

The end of the Devonian saw the

The end of the Devonian saw the late Devonian extinction

The Late Devonian extinction consisted of several extinction events in the Late Devonian Epoch, which collectively represent one of the five largest mass extinction events in the history of life on Earth. The term primarily refers to a major ex ...

event, followed by a gap in the fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

record of some 15 million years at the start of the Carboniferous, called "Romer's gap

Romer's gap is an example of an apparent gap in the tetrapod fossil record used in the study of evolutionary biology. Such gaps represent periods from which excavators have not yet found relevant fossils. Romer's gap is named after paleontologist ...

". The gap marks the disappearance of the ichthyostegalian forms as well as the origin of the higher labyrinthodonts. Finds from this period found in East Kirkton Quarry

East Kirkton Quarry is a former limestone quarry in West Lothian, Scotland ( East Kirkton Limestone), now better known as a fossil site known for terrestrial fossils from the fossil-poor Romer's gap, a 15 million year period at the beginning of ...

includes the peculiar, probably secondarily aquatic ''Crassigyrinus

''Crassigyrinus'' (from la, crassus, 'thick' and el, γυρίνος el, gyrínos, 'tadpole') is an extinct genus of carnivorous stem tetrapod from the Early Carboniferous Limestone Coal Group of Scotland and possibly Greer, West Virginia. Th ...

'', which may represent the sister group to later labyrinthodont groups.

Early Carboniferous saw the radiation of the family Loxommatidae, a distinct if mysterious group that may have been the ancestors or sister taxon of the higher groups, characterized by keyhole-shaped eye openings. By the Visean age of mid-Carboniferous times the labyrinthodonts had radiated into at least three main branches. Recognizable groups are representative of the temnospondyls

Temnospondyli (from Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') is a diverse order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished worldwide during the Carbo ...

, lepospondyls and reptile-like amphibians, the latter which were the relatives and ancestors of the Amniota

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are dis ...

.

While most labyrinthodonts remained aquatic or semi-aquatic, some of the reptile-like amphibians adapted to explore the terrestrial ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for ...

s as small or medium-sized predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill t ...

s. They evolved increasingly terrestrial adaptions during the Carboniferous, including stronger vertebrae and slender limbs, and a deeper skull with laterally placed eyes. They probably had watertight skin, possibly covered with a horny epidermis overlaying small bony nodules, forming scute

A scute or scutum (Latin: ''scutum''; plural: ''scuta'' "shield") is a bony external plate or scale overlaid with horn, as on the shell of a turtle, the skin of crocodilians, and the feet of birds. The term is also used to describe the anterior po ...

s, similar to those found in modern caecilians. To the modern eye, these animals would appear like heavyset, lizards betraying their amphibious nature only by their lack of claw

A claw is a curved, pointed appendage found at the end of a toe or finger in most amniotes (mammals, reptiles, birds). Some invertebrates such as beetles and spiders have somewhat similar fine, hooked structures at the end of the leg or tarsus ...

s and by spawning

Spawn is the eggs and sperm released or deposited into water by aquatic animals. As a verb, ''to spawn'' refers to the process of releasing the eggs and sperm, and the act of both sexes is called spawning. Most aquatic animals, except for aquat ...

aquatic eggs. In the middle or late Carboniferous, smaller forms gave rise to the first reptile

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates ( lizards and snakes) and rhynchocephalia ...

s.R. L. Paton, R. L., Smithson, T. R. & Clack, J. A. (1999): An amniote-like skeleton from the Early Carboniferous of Scotlan(abstract)

''

Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

'' 398, 508–513 (8 April 1999) In the late Carboniferous, a global rainforest collapse

Ecological collapse refers to a situation where an ecosystem suffers a drastic, possibly permanent, reduction in carrying capacity for all organisms, often resulting in mass extinction. Usually, an ecological collapse is precipitated by a disastro ...

favoured the more terrestrially adapted reptiles, while the many of their amphibian relatives failed to reestablish. Some reptile-like amphibians did flourish in the new seasonal environment. The reptiliomorph family Diadectidae

Diadectidae is an extinct family of early tetrapods that lived in what is now North America and Europe during the Late Carboniferous and Early Permian in Asia during the Late Permian. They were the first herbivorous tetrapods, and also the first ...

evolved herbivory, becoming the largest terrestrial animals of the day with barrel-shaped, heavy bodies. There were also a family of correspondingly large carnivores, the Limnoscelidae, that flourished briefly in the late Carboniferous.

Heyday of the labyrinthodonts

The herbivorous Diadectidae reached their maximum diversity in the late Carboniferous/early

The herbivorous Diadectidae reached their maximum diversity in the late Carboniferous/early Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleo ...

, and then quickly declined, their role taken over by early reptilian herbivores like Pareiasaur

Pareiasaurs (meaning "cheek lizards") are an extinct clade of large, herbivorous parareptiles. Members of the group were armoured with scutes which covered large areas of the body. They first appeared in southern Pangea during the Middle Permi ...

s and Edaphosaurs. Colbert, E. H. & Morales, M. (1990): Evolution of the Vertebrates: A history of the Backboned Animals Through Time, John Wiley & Sons Inc (4th ed., 470 pp) Unlike the reptile-like amphibians, the Temnospondyli

Temnospondyli (from Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') is a diverse order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished worldwide during the Carb ...

remained mostly denizens of rivers and swampland, feeding on fish and perhaps other labyrinthodonts. They underwent a major diversification in the wake of the Carboniferous rainforest collapse and they too subsequently reached their greatest diversity in the late Carboniferous and early Permian, thriving in the rivers and brackish coal forest

Coal forests were the vast swathes of wetlands that covered much of the Earth's tropical land areas during the late Carboniferous ( Pennsylvanian) and Permian times.Cleal, C. J. & Thomas, B. A. (2005). "Palaeozoic tropical rainforests and their e ...

s in continental shallow basins around equatorial Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea () was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million y ...

and around the Paleo-Tethys Ocean

The Paleo-Tethys or Palaeo-Tethys Ocean was an ocean located along the northern margin of the paleocontinent Gondwana that started to open during the Middle Cambrian, grew throughout the Paleozoic, and finally closed during the Late Triassic; exi ...

.

Several adaptations to piscivory

A piscivore () is a carnivorous animal that eats primarily fish. The name ''piscivore'' is derived . Piscivore is equivalent to the Greek-derived word ichthyophage, both of which mean "fish eater". Fish were the diet of early tetrapod evolut ...

evolved with some groups having crocodile

Crocodiles (family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to include all extant me ...

-like skulls with slender snouts, and presumably had a similar life-style (Archegosauridae

Archegosauridae is a family of relatively large and long snouted temnospondyls that lived in the Permian period. They were fully aquatic animals, and were metabolically and physiologically more similar to fish than modern amphibians.Florian Witzm ...

, Melosauridae, Cochleosauridae

Cochleosauridae is a family of edopoid temnospondyl amphibians, among the most basal of temnospondyls. Most members of this family are known from the late Carboniferous ( Pennsylvanian) and early Permian (Cisuralian) of Europe and North America, ...

and Eryopidae, and the reptile-like suborder Embolomeri

Embolomeri is an order of tetrapods or stem-tetrapods, possibly members of Reptiliomorpha. Embolomeres first evolved in the Early Carboniferous ( Mississippian) Period and were the largest and most successful predatory tetrapods of the Late Carbon ...

). Others evolved as aquatic ambush predators, with short, broad skulls that allowed for opening the mouth by tipping the skull back rather than dropping the jaw (Plagiosauridae

Plagiosauridae is a clade of temnospondyl amphibians of the Middle to Late Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the begi ...

and the Dvinosauria

Dvinosaurs are one of several new clades of Temnospondyl amphibians named in the phylogenetic review of the group by Yates and Warren 2000. They represent a group of primitive semi-aquatic to completely aquatic amphibians, and are known from t ...

). In life they would have hunted rather like the modern day monkfish

Members of the genus ''Lophius'', also sometimes called monkfish, fishing-frogs, frog-fish, and sea-devils, are various species of lophiid anglerfishes found in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. ''Lophius'' is known as the "monk" or "monkfish" ...

, and several groups are known to have retained the larval gills into adulthood, being fully aquatic. The Metoposauridae

Metoposauridae is an extinct family of trematosaurian temnospondyls. The family is known from the Triassic period. Most members are large, approximately long and could reach 3 m long.Brusatte, S. L., Butler R. J., Mateus O., & Steyer S. J. (201 ...

adapted to hunting in shallows and murky swamps, with ∩-shaped skull, much like their Devonian ancestors.

In Euramerica

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

, the Lepospondyli

Lepospondyli is a diverse taxon of early tetrapods. With the exception of one late-surviving lepospondyl from the Late Permian of Morocco ('' Diplocaulus minumus''), lepospondyls lived from the Early Carboniferous ( Mississippian) to the Early Pe ...

, a host of small, mostly aquatic amphibians of uncertain phylogeny, appeared in the Carboniferous. They lived in the tropical forest undergrowth and in small ponds, in ecological niches similar to those of modern amphibians. In the Permian, the peculiar Nectridea

Nectridea is the name of an extinct order of lepospondyl tetrapods from the Carboniferous and Permian periods, including animals such as '' Diplocaulus''. In appearance, they would have resembled modern newts or aquatic salamanders, although the ...

found their way from Euramerica to Gondwanaland.

Decline

From the middle of the Permian, the climate dried up, making life difficult for the amphibians. The terrestrial reptiliomorphs disappeared, though aquatic crocodile-likeEmbolomeri

Embolomeri is an order of tetrapods or stem-tetrapods, possibly members of Reptiliomorpha. Embolomeres first evolved in the Early Carboniferous ( Mississippian) Period and were the largest and most successful predatory tetrapods of the Late Carbon ...

continued to thrive until going extinct in the Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest per ...

. The diverse lepospondyl inhabitants of the undergrowth disappear from the fossil record, among them the snake-like Aïstopoda

Aistopoda (Greek for " avingnot-visible feet") is an order of highly specialised snake-like stegocephalians known from the Carboniferous and Early Permian of Europe and North America, ranging from tiny forms only , to nearly in length. They fir ...

.

With the close of the Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ...

, most of the Permian groups disappeared

An enforced disappearance (or forced disappearance) is the secret abduction or imprisonment of a person by a state or political organization, or by a third party with the authorization, support, or acquiescence of a state or political organi ...

, with the exceptions of the Mastodonsauroidea, Metoposauridae

Metoposauridae is an extinct family of trematosaurian temnospondyls. The family is known from the Triassic period. Most members are large, approximately long and could reach 3 m long.Brusatte, S. L., Butler R. J., Mateus O., & Steyer S. J. (201 ...

and Plagiosauridae

Plagiosauridae is a clade of temnospondyl amphibians of the Middle to Late Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the begi ...

, who continued into the Triassic. In the early Triassic these groups enjoyed a brief renaissance in the waterways of continental shallows, with large forms like ''Thoosuchus

''Thoosuchus'' (meaning "active crocodile") is an extinct genus of basal trematosauroid trematosaurian temnospondyl. Fossils have been found from Russia and date back to the Early Triassic. It is the type genus of the family Thoosuchidae, fo ...

'', ''Benthosuchus

''Benthosuchus'' (meaning "deep water crocodile") is an extinct genus of temnospondyl amphibian from the Early Triassic of Russia. It was primarily aquatic, living in rivers and lakes. Multiple species are known, with the largest reaching ab ...

'' and ''Eryosuchus

''Eryosuchus'' is an extinct genus of capitosauroid temnospondyl amphibian from the Middle Triassic of northern Russia. It was a very large predator: the largest specimen known could reach up to 3.5 m (11.5 ft) in length, with a skull ...

''. Their ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for ...

s were probably similar to those of modern-day crocodiles, as fish hunters and riverside carnivores. All groups developed progressively weaker vertebrae, reduced limb ossification and flatter skulls with prominent lateral line

The lateral line, also called the lateral line organ (LLO), is a system of sensory organs found in fish, used to detect movement, vibration, and pressure gradients in the surrounding water. The sensory ability is achieved via modified epithelial ...

organs, indicating the late Permian/early Triassic temnospondyls rarely if ever left the water. An extremely large brachyopid

Brachyopidae is an extinct family of temnospondyl labyrintodonts. They evolved in the early Mesozoic and were mostly aquatic. A fragmentary find from Lesotho, Africa is estimated to have been long, the largest amphibian ever known to have li ...

(likely a plagiosaur or a close relative) is estimated to have been 7 meters long, and probably just as heavy as the Permian ''Prionosuchus

''Prionosuchus'' is an extinct genus of large temnospondyl. A single species ''P. plummeri'', is recognized from the Early Permian (some time between 299 and 272 million years ago). Its fossils have been found in what is now northeastern Brazil.

...

''.

With the rise of the real crocodile

Crocodiles (family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to include all extant me ...