Labrador Sea on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Labrador Sea (French: ''mer du Labrador'', Danish: ''Labradorhavet'') is an arm of the

The Labrador Sea is about deep and wide where it joins the Atlantic Ocean. It becomes shallower, to less than towards Baffin Bay (see depth map) and passes into the wide Davis Strait. A deep

The Labrador Sea is about deep and wide where it joins the Atlantic Ocean. It becomes shallower, to less than towards Baffin Bay (see depth map) and passes into the wide Davis Strait. A deep

The Labrador duck was a common bird on the Canadian coast until the 19th century, but is now extinct. Other coastal animals include the Labrador wolf (''Canis lupus labradorius''),

The Labrador duck was a common bird on the Canadian coast until the 19th century, but is now extinct. Other coastal animals include the Labrador wolf (''Canis lupus labradorius''),

Ledum groenlandicum Oeder – Labrador Tea

(PDF) . Retrieved on 2013-03-20.

North Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

between the Labrador Peninsula

The Labrador Peninsula, or Quebec-Labrador Peninsula, is a large peninsula in eastern Canada. It is bounded by the Hudson Bay to the west, the Hudson Strait to the north, the Labrador Sea to the east, and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the so ...

and Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

. The sea is flanked by continental shelves

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

to the southwest, northwest, and northeast. It connects to the north with Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay (Inuktitut: ''Saknirutiak Imanga''; kl, Avannaata Imaa; french: Baie de Baffin), located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arc ...

through the Davis Strait. It is a marginal sea of the Atlantic.

The sea formed upon separation of the North American Plate

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate covering most of North America, Cuba, the Bahamas, extreme northeastern Asia, and parts of Iceland and the Azores. With an area of , it is the Earth's second largest tectonic plate, behind the Paci ...

and Greenland Plate

The Greenland Plate is a supposed tectonic plate bounded to the west by Nares Strait, a probable transform fault; on the southwest by the Ungava transform underlying Davis Strait; on the southeast by the Mid-Atlantic Ridge; and the northeast by t ...

that started about 60 million years ago and stopped about 40 million years ago. It contains one of the world's largest turbidity current

A turbidity current is most typically an underwater current of usually rapidly moving, sediment-laden water moving down a slope; although current research (2018) indicates that water-saturated sediment may be the primary actor in the process. T ...

channel systems, the Northwest Atlantic Mid-Ocean Channel (NAMOC), that runs for thousands of kilometers along the sea bottom toward the Atlantic Ocean.

The Labrador Sea is a major source of the North Atlantic Deep Water, a cold water mass that flows at great depth along the western edge of the North Atlantic, spreading out to form the largest identifiable water mass in the World Ocean.

History

The Labrador Sea formed upon separation of theNorth American Plate

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate covering most of North America, Cuba, the Bahamas, extreme northeastern Asia, and parts of Iceland and the Azores. With an area of , it is the Earth's second largest tectonic plate, behind the Paci ...

and Greenland Plate

The Greenland Plate is a supposed tectonic plate bounded to the west by Nares Strait, a probable transform fault; on the southwest by the Ungava transform underlying Davis Strait; on the southeast by the Mid-Atlantic Ridge; and the northeast by t ...

that started about 60 million years ago (Paleocene

The Paleocene, ( ) or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name is a combination of the Ancient Greek ''pala ...

) and stopped about 40 million years ago. A sedimentary basin

Sedimentary basins are region-scale depressions of the Earth's crust where subsidence has occurred and a thick sequence of sediments have accumulated to form a large three-dimensional body of sedimentary rock. They form when long-term subsiden ...

, which is now buried under the continental shelves, formed during the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

. Onset of magmatic sea-floor spreading

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener ...

was accompanied by volcanic eruptions of picrite

Picrite basalt or picrobasalt is a variety of high-magnesium olivine basalt that is very rich in the mineral olivine. It is dark with yellow-green olivine phenocrysts (20-50%) and black to dark brown pyroxene, mostly augite.

The olivine-rich p ...

s and basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90 ...

s in the Paleocene

The Paleocene, ( ) or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name is a combination of the Ancient Greek ''pala ...

at the Davis Strait and Baffin Bay.

Between about 500 BC and 1300 AD, the southern coast of the sea contained Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

, Beothuk and Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

settlements; Dorset tribes were later replaced by Thule people

The Thule (, , ) or proto-Inuit were the ancestors of all modern Inuit. They developed in coastal Alaska by the year 1000 and expanded eastward across northern Canada, reaching Greenland by the 13th century. In the process, they replaced people o ...

.

Extent

TheInternational Hydrographic Organization

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) is an intergovernmental organisation representing hydrography. , the IHO comprised 98 Member States.

A principal aim of the IHO is to ensure that the world's seas, oceans and navigable waters ...

defines the limits of the Labrador Sea as follows:

On the North: the South limit of Davis Strait 60° North betweenGreenland Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...and Labrador]. On the East: a line from Cape St. Francis (Newfoundland and Labrador, Newfoundland) to Cape Farewell, Greenland, Cape Farewell (Greenland). On the West: the East Coast of Labrador and Newfoundland and the Northeast limit of the Gulf of St. Lawrence – a line running from Cape Bauld (North point of Kirpon Island, ) to the East extreme of Belle Isle and on to the Northeast Ledge (). Thence a line joining this ledge with the East extreme ofCape St. Charles Cape St. Charles is a headland on the coast of Labrador in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. At longitude 55°37'15" W, it is the easternmost point of continental North America North America is a continent in the Nor ...(52°13'N) in Labrador.

Natural Resources Canada

Natural Resources Canada (NRCan; french: Ressources naturelles Canada; french: RNCan, label=none)Natural Resources Canada is the applied title under the Federal Identity Program; the legal title is Department of Natural Resources (). is the dep ...

uses a slightly different definition, putting the northern boundary of the Labrador Sea on a straight line from a headland on Killiniq Island

Killiniq Island (English: ''ice floes'') is a remote island in southeastern Nunavut and northern Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Located at the extreme northern tip of Labrador between Ungava Bay and the Labrador Sea, it is notable in that it c ...

abutting Lady Job Harbour to Cape Farewell.

Oceanography

The Labrador Sea is about deep and wide where it joins the Atlantic Ocean. It becomes shallower, to less than towards Baffin Bay (see depth map) and passes into the wide Davis Strait. A deep

The Labrador Sea is about deep and wide where it joins the Atlantic Ocean. It becomes shallower, to less than towards Baffin Bay (see depth map) and passes into the wide Davis Strait. A deep turbidity current

A turbidity current is most typically an underwater current of usually rapidly moving, sediment-laden water moving down a slope; although current research (2018) indicates that water-saturated sediment may be the primary actor in the process. T ...

channel system, which is about wide and long, runs on the bottom of the sea, near its center from the Hudson Strait

Hudson Strait (french: Détroit d'Hudson) links the Atlantic Ocean and Labrador Sea to Hudson Bay in Canada. This strait lies between Baffin Island and Nunavik, with its eastern entrance marked by Cape Chidley in Newfoundland and Labrador and ...

into the Atlantic. It is called the Northwest Atlantic Mid-Ocean Channel (NAMOC) and is one of the world's longest drainage systems of Pleistocene age. It appears as a submarine river bed with numerous tributaries and is maintained by high-density turbidity currents flowing within the levee

A levee (), dike (American English), dyke (Commonwealth English), embankment, floodbank, or stop bank is a structure that is usually earthen and that often runs parallel to the course of a river in its floodplain or along low-lying coastli ...

s.

The water temperature varies between in winter and in summer. The salinity is relatively low, at 31–34.9 parts per thousand. Two-thirds of the sea is covered in ice in winter. Tides are semi-diurnal

A diurnal cycle (or diel cycle) is any pattern that recurs every 24 hours as a result of one full rotation of the planet Earth around its axis. Earth's rotation causes surface temperature fluctuations throughout the day and night, as well as ...

(i.e. occur twice a day), reaching .

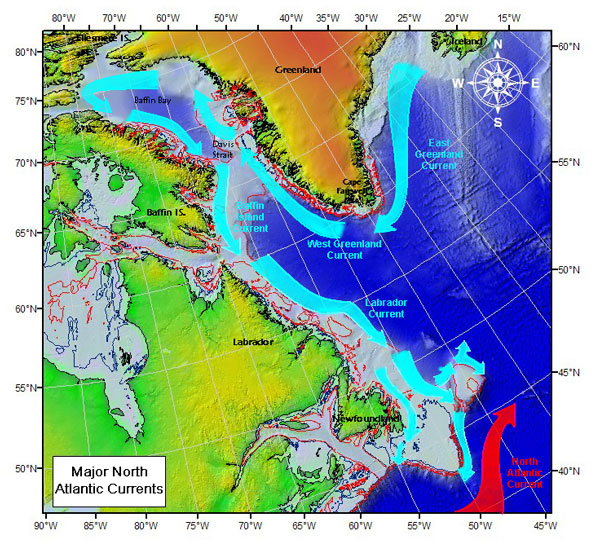

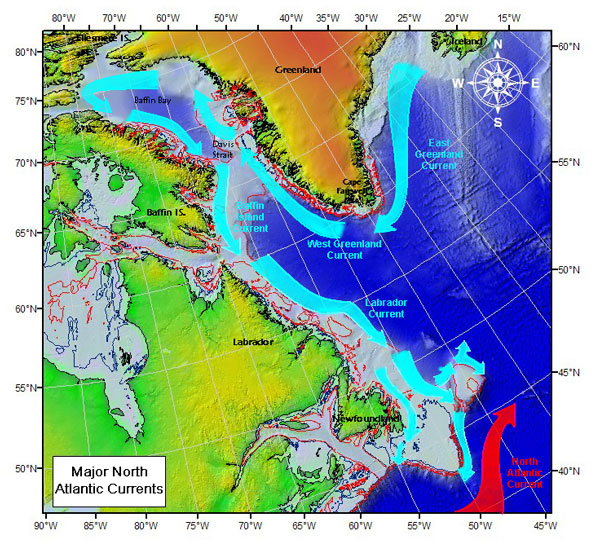

There is an anticlockwise water circulation in the sea. It is initiated by the East Greenland Current and continued by the West Greenland Current, which brings warmer, more saline waters northwards, along the Greenland coasts up to the Baffin Bay. Then, the Baffin Island Current and Labrador Current transport cold and less saline water southward along the Canadian coast. These currents carry numerous icebergs and therefore hinder navigation and exploration of the gas fields beneath the sea bed. The speed of the Labrador current is typically , but can reach in some areas, whereas the Baffin Current is somewhat slower at about . The Labrador Current maintains the water temperature at and salinity between 30 and 34 parts per thousand.

The sea provides a significant part of the North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) – a cold water mass that flows at great depth along the western edge of the North Atlantic, spreading out to form the largest identifiable water mass in the World Ocean. The NADW consists of three parts of different origin and salinity, and the top one, the Labrador Sea Water (LSW), is formed in the Labrador Sea. This part occurs at a medium depth and has a relatively low salinity (34.84–34.89 parts per thousand), low temperature () and high oxygen content compared to the layers above and below it. LSW also has a relatively low vorticity, i.e. the tendency to form vortices, than any other water in North Atlantic that reflects its high homogeneity. It has a potential density of 27.76–27.78 mg/cm3 relatively to the surface layers, meaning it is denser, and thus sinks under the surface and remains homogeneous and unaffected by the surface fluctuations.

Fauna

The northern and western parts of the Labrador Sea are covered in ice between December and June. The drift ice serves as a breeding ground for seals in early spring. The sea is also a feeding ground forAtlantic salmon

The Atlantic salmon (''Salmo salar'') is a species of ray-finned fish in the family Salmonidae. It is the third largest of the Salmonidae, behind Siberian taimen and Pacific Chinook salmon, growing up to a meter in length. Atlantic salmon are ...

and several marine mammal species. Shrimp fisheries began in 1978 and intensified toward 2000, as well as cod fishing. However, the cod fishing rapidly depleted the fish population in the 1990s near the Labrador and West Greenland banks and was therefore halted in 1992. Other fishery targets include haddock, Atlantic herring

Atlantic herring (''Clupea harengus'') is a herring in the family Clupeidae. It is one of the most abundant fish species in the world. Atlantic herrings can be found on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, congregating in large schools. They can ...

, lobster

Lobsters are a family (Nephropidae, synonym Homaridae) of marine crustaceans. They have long bodies with muscular tails and live in crevices or burrows on the sea floor. Three of their five pairs of legs have claws, including the first pair, ...

and several species of flatfish

A flatfish is a member of the ray-finned demersal fish order Pleuronectiformes, also called the Heterosomata, sometimes classified as a suborder of Perciformes. In many species, both eyes lie on one side of the head, one or the other migrating ...

and pelagic fish

Pelagic fish live in the pelagic zone of ocean or lake waters—being neither close to the bottom nor near the shore—in contrast with demersal fish that do live on or near the bottom, and reef fish that are associated with coral re ...

such as sand lance and capelin. They are most abundant in the southern parts of the sea.

Beluga whales

The beluga whale () (''Delphinapterus leucas'') is an Arctic and sub-Arctic cetacean. It is one of two members of the family Monodontidae, along with the narwhal, and the only member of the genus ''Delphinapterus''. It is also known as the whi ...

, while abundant to the north, in the Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay (Inuktitut: ''Saknirutiak Imanga''; kl, Avannaata Imaa; french: Baie de Baffin), located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arc ...

, where their population reaches 20,000, are rare in the Labrador Sea, especially since the 1950s. The sea contains one of the two major stocks of Sei whale

The sei whale ( , ; ''Balaenoptera borealis'') is a baleen whale, the third-largest rorqual after the blue whale and the fin whale. It inhabits most oceans and adjoining seas, and prefers deep offshore waters. It avoids polar and tropical w ...

s, the other one being the Scotian Shelf. Also common are minke and bottlenose whale

''Hyperoodon'' (or ''Hyperoödon'') is a genus of beaked whale, containing just two species: the Northern and Southern bottlenose whales.

While not in the genus ''Hyperoodon'', Longman's beaked whale

The tropical bottlenose whale (''Indopac ...

s.

The Labrador duck was a common bird on the Canadian coast until the 19th century, but is now extinct. Other coastal animals include the Labrador wolf (''Canis lupus labradorius''),

The Labrador duck was a common bird on the Canadian coast until the 19th century, but is now extinct. Other coastal animals include the Labrador wolf (''Canis lupus labradorius''), caribou

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subspe ...

(''Rangifer'' spp.), moose

The moose (in North America) or elk (in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is a member of the New World deer subfamily and is the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is the largest and heaviest extant species in the deer family. Most adult ma ...

(''Alces alces''), black bear (''Ursus americanus''), red fox

The red fox (''Vulpes vulpes'') is the largest of the true foxes and one of the most widely distributed members of the Order (biology), order Carnivora, being present across the entire Northern Hemisphere including most of North America, Europe ...

(''Vulpes vulpes''), Arctic fox (''Alopex lagopus''), wolverine

The wolverine (), (''Gulo gulo''; ''Gulo'' is Latin for " glutton"), also referred to as the glutton, carcajou, or quickhatch (from East Cree, ''kwiihkwahaacheew''), is the largest land-dwelling species of the family Mustelidae. It is a musc ...

, snowshoe hare (''Lepus americanus''), grouse

Grouse are a group of birds from the order Galliformes, in the family Phasianidae. Grouse are presently assigned to the tribe Tetraonini (formerly the subfamily Tetraoninae and the family Tetraonidae), a classification supported by mitochondria ...

(''Dendragapus'' spp.), osprey

The osprey (''Pandion haliaetus''), , also called sea hawk, river hawk, and fish hawk, is a diurnal, fish-eating bird of prey with a cosmopolitan range. It is a large raptor reaching more than in length and across the wings. It is brown o ...

(''Pandion haliaetus''), raven (''Corvus corax''), ducks, geese, partridge and American wild pheasant.

Flora

Coastal vegetation includesblack spruce

''Picea mariana'', the black spruce, is a North American species of spruce tree in the pine family. It is widespread across Canada, found in all 10 provinces and all 3 territories. It is the official tree of the province of Newfoundland and Lab ...

(''Picea mariana''), tamarack, white spruce White spruce is a common name for several species of spruce (''Picea'') and may refer to:

* ''Picea glauca'', native to most of Canada and Alaska with limited populations in the northeastern United States

* ''Picea engelmannii

''Picea engelman ...

(''P. glauca''), dwarf birch (''Betula'' spp.), aspen

Aspen is a common name for certain tree species; some, but not all, are classified by botanists in the section ''Populus'', of the '' Populus'' genus.

Species

These species are called aspens:

*'' Populus adenopoda'' – Chinese aspen (C ...

, willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, from the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 400 speciesMabberley, D.J. 1997. The Plant Book, Cambridge University Press #2: Cambridge. of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist so ...

(''Salix'' spp.), ericaceous shrubs ('' Ericaceae''), cottongrass

''Eriophorum'' (cottongrass, cotton-grass or cottonsedge) is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cyperaceae, the sedge family. They are found throughout the arctic, subarctic, and temperate portions of the Northern Hemisphere in acid bog h ...

(''Eriophorum'' spp.), sedge

The Cyperaceae are a family of graminoid (grass-like), monocotyledonous flowering plants known as sedges. The family is large, with some 5,500 known species described in about 90 genera, the largest being the "true sedges" genus '' Carex'' ...

(''Carex'' spp.), lichens and moss. Evergreen bushes of Labrador tea, which is used to make herbal teas, are common in the area, both on the Greenland and Canadian coasts.(PDF) . Retrieved on 2013-03-20.

References

{{Authority control Oceanography Seas of Greenland Seas of the Atlantic Ocean Bodies of water of Newfoundland and Labrador Seas of Canada Geography of North America Cenozoic rifts and grabens