LGBT history in the United Kingdom on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

* 117 – Emperor

* 117 – Emperor

* 1533 – King

* 1533 – King

*1726 – Three men (Gabriel Lawrence, William Griffin, and Thomas Wright) were hanged at

*1726 – Three men (Gabriel Lawrence, William Griffin, and Thomas Wright) were hanged at

*1800 –

*1800 –  *1872 – Sheridan Le Fanu publishes the novella ''

*1872 – Sheridan Le Fanu publishes the novella ''

*1906 – Dr.

*1906 – Dr.

*1921 – The Criminal Law Amendment Act was amended in the

*1921 – The Criminal Law Amendment Act was amended in the

*1954 –

*1954 –

*1975 – The groundbreaking film portraying homosexual gay icon

*1975 – The groundbreaking film portraying homosexual gay icon

– 'Gay Left Collective' *1976 – The was established by Phillip Cox and Paul Welch. It was chaired by Steven Power, a 1970s gay activist, from 1977 until 1980 when he became 21. It was the first officially registered gay youth group in Europe.

*1977 – The first gay lesbian

*1976 – The was established by Phillip Cox and Paul Welch. It was chaired by Steven Power, a 1970s gay activist, from 1977 until 1980 when he became 21. It was the first officially registered gay youth group in Europe.

*1977 – The first gay lesbian

*1980 – The

*1980 – The  *1988 – Section 28 of the

*1988 – Section 28 of the

Host: James Lipton. ''

*1990 – In July, following the murders in a short period of time, of Christopher Schliach, Henry Bright, William Dalziel and Michael Boothe, hundreds of lesbians and gay men marched from the park where Boothe had been killed to Ealing Town Hall and held a candlelit vigil. The demonstration led to the formation of OutRage, who called for the police to start protecting gay men instead of arresting them. In September, lesbian and gay police officers established the Lesbian and Gay Police Association (Lagpa/GPA). The first

*1990 – In July, following the murders in a short period of time, of Christopher Schliach, Henry Bright, William Dalziel and Michael Boothe, hundreds of lesbians and gay men marched from the park where Boothe had been killed to Ealing Town Hall and held a candlelit vigil. The demonstration led to the formation of OutRage, who called for the police to start protecting gay men instead of arresting them. In September, lesbian and gay police officers established the Lesbian and Gay Police Association (Lagpa/GPA). The first  *1997 –

*1997 –

*2001

** The last two pieces of unequal law regarding gay male sex are changed. In 1997 the

*2001

** The last two pieces of unequal law regarding gay male sex are changed. In 1997 the

Chris Smith writing in ''The Sunday Times'', 30 January 2005 ** The UK-based online newspaper PinkNews is launched, which is specifically marketed to the LGBT community. *2006 ** The Equality Act 2006 which establishes the Equality and Human Rights Commission (CEHR) and makes discrimination against lesbians and gay men in the provision of goods and services illegal, gains Royal Assent on 16 February. ** The

*2011

**England, Wales and Scotland allow gay and bi men to donate blood after a 1-year deferral period.

*2012

** In the year in which London hosted the Olympic Games, London hosts World Pride but the committee fails to secure funding and has to drastically cut back the parade and cancel many of the events.

** The coalition government committed to legislate for gay marriage by 2015, but by 2012 still had not been included in the Queen's Speech.

** Thousands of people sign an e-petition to feature

*2011

**England, Wales and Scotland allow gay and bi men to donate blood after a 1-year deferral period.

*2012

** In the year in which London hosted the Olympic Games, London hosts World Pride but the committee fails to secure funding and has to drastically cut back the parade and cancel many of the events.

** The coalition government committed to legislate for gay marriage by 2015, but by 2012 still had not been included in the Queen's Speech.

** Thousands of people sign an e-petition to feature  *2016

** There are 40 LGBT MPs in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which in 2016 is the most in any parliament around the world.

** Hannah Blythyn, Jeremy Miles, and Adam Price became the first openly gay members of the Welsh Assembly.

** Carl Austin-Behan was sworn in as Manchester's first openly gay Lord Mayor.

** Northern Ireland allow gay and bi men to donate blood after a 1-year deferral period.

** Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, Prince William became the first member of Britain's royal family to appear on the cover of a gay magazine when he appeared on the cover of the July issue of ''Attitude (magazine), Attitude''; in the cover story, he also became the first British royal to openly condemn the bullying of the gay community.

** British Government minister Justine Greening revealed that she was in a same-sex relationship, thus becoming the first out LGB female cabinet minister.

** ''Elle (magazine), Elle'' printed special collectors' covers for their September 2016 issue, and one of them featured Hari Nef, which was the first time an openly transgender woman had been on the cover of a major commercial British magazine.

** The Great Britain women's national field hockey team, British women's field hockey team won gold at the Olympics; as Kate and Helen Richardson-Walsh were both on that team, this made them the first same-sex married couple to win Olympic medals.

** Nicholas Chamberlain became the first bishop in the Church of England to coming out, come out as gay, which occurred following threats of an outing from an unnamed Sunday newspaper. He said he lived with his partner in a celibate same-sex relationship, as required by the Bishops' guidelines, under which LGBT clergy in Christianity, gay clergy must practice abstinence and may not marry.

** Ivar Mountbatten came out as gay and revealed that he was in a relationship with James Coyle, an airline cabin services director whom he met whilst at a ski resort in Verbier. While not being a member of the British royal family, he is the first member of the extended family to come out as gay.

** Anwen Muston, a British Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician, was elected to Wolverhampton City Council at the Wolverhampton City Council election, 2016, 2016 elections; this makes her the first openly transgender woman to be elected as a Labour representative.

** The Armed Forces Act 2016 finally repeals "homosexual acts as a grounds of discharge from the armed forces".

*2017

** In April 2017, the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the Merchant Shipping (Homosexual Conduct) Act 2017. This private member's bill was drafted by

*2016

** There are 40 LGBT MPs in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which in 2016 is the most in any parliament around the world.

** Hannah Blythyn, Jeremy Miles, and Adam Price became the first openly gay members of the Welsh Assembly.

** Carl Austin-Behan was sworn in as Manchester's first openly gay Lord Mayor.

** Northern Ireland allow gay and bi men to donate blood after a 1-year deferral period.

** Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, Prince William became the first member of Britain's royal family to appear on the cover of a gay magazine when he appeared on the cover of the July issue of ''Attitude (magazine), Attitude''; in the cover story, he also became the first British royal to openly condemn the bullying of the gay community.

** British Government minister Justine Greening revealed that she was in a same-sex relationship, thus becoming the first out LGB female cabinet minister.

** ''Elle (magazine), Elle'' printed special collectors' covers for their September 2016 issue, and one of them featured Hari Nef, which was the first time an openly transgender woman had been on the cover of a major commercial British magazine.

** The Great Britain women's national field hockey team, British women's field hockey team won gold at the Olympics; as Kate and Helen Richardson-Walsh were both on that team, this made them the first same-sex married couple to win Olympic medals.

** Nicholas Chamberlain became the first bishop in the Church of England to coming out, come out as gay, which occurred following threats of an outing from an unnamed Sunday newspaper. He said he lived with his partner in a celibate same-sex relationship, as required by the Bishops' guidelines, under which LGBT clergy in Christianity, gay clergy must practice abstinence and may not marry.

** Ivar Mountbatten came out as gay and revealed that he was in a relationship with James Coyle, an airline cabin services director whom he met whilst at a ski resort in Verbier. While not being a member of the British royal family, he is the first member of the extended family to come out as gay.

** Anwen Muston, a British Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician, was elected to Wolverhampton City Council at the Wolverhampton City Council election, 2016, 2016 elections; this makes her the first openly transgender woman to be elected as a Labour representative.

** The Armed Forces Act 2016 finally repeals "homosexual acts as a grounds of discharge from the armed forces".

*2017

** In April 2017, the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the Merchant Shipping (Homosexual Conduct) Act 2017. This private member's bill was drafted by

UK LGBT Archive

's "Timeline of UK LGBT History"] {{LGBT in the United Kingdom LGBT history in the United Kingdom, * British history timelines LGBT timelines, United Kingdom

Celtic Britain

*TheIron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ap ...

(600 BC to 50 AD) – Celtic Britain

The British Iron Age is a conventional name used in the archaeology of Great Britain, referring to the prehistoric and protohistoric phases of the Iron Age culture of the main island and the smaller islands, typically excluding prehistoric Ir ...

commenced around the time of the Iron Age. In Celtic society male homosexuality was permissible and acceptable between free adult men. However, these homosexual activities were bound by the male dominated Celtic culture, and was not seen as an effeminate practice.

*Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which s ...

the Sicilian historian (1st century BC) stated that, 'although Celtic women were beautiful, their men preferred to sleep with each other'. Siculus also noted that 'it was an insult if a guest refused an offer of sex from a Celtic man. They usually sleep on the ground on skins of wild animals and tumble about with a bedfellow on either side. And what is strangest of all is that, without any thought for a natural sense of modesty, they carelessly surrender their virginity to other man. Far from finding anything shameful in all this, they feel insulted if anyone refuses the favours they offer'.

1st century

* TheRoman conquest of Britain

The Roman conquest of Britain refers to the conquest of the island of Britain by occupying Roman forces. It began in earnest in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and was largely completed in the southern half of Britain by 87 when the Stane ...

begins, creating Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the period in classical antiquity when large parts of the island of Great Britain were under occupation by the Roman Empire. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410. During that time, the territory conquered wa ...

. Roman society was to shape Britain for the next four centuries. In the three main cities of London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a major s ...

, Colchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in Essex, in the East of England. It had a population of 122,000 in 2011. The demonym is Colcestrian.

Colchester occupies the site of Camulodunum, the first major city in Roman Britain and its first capital. Colches ...

and Saint Albans as in all Roman settlements was patriarchal

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of dominance and privilege are primarily held by men. It is used, both as a technical anthropological term for families or clans controlled by the father or eldest male or group of males a ...

, and the freeborn

"Freeborn" is a term associated with political agitator John Lilburne (1614–1657), a member of the Levellers, a 17th-century English political party. As a word, "freeborn" means born free, rather than in slavery or bondage or vassalage. Lilbur ...

male citizen

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

possessed political liberty (''libertas'') and the right to rule both himself and his household ('' familia''). "Virtue" (''virtus

''Virtus'' () was a specific virtue in Ancient Rome. It carries connotations of valor, manliness, excellence, courage, character, and worth, perceived as masculine strengths (from Latin ''vir'', "man"). It was thus a frequently stated virtue ...

'') was seen as an active quality through which a man (''vir'') defined himself. The conquest mentality and "cult of virility" shaped same-sex relations. Roman men were free to enjoy sex with other males without a perceived loss of masculinity or social status, as long as they took the dominant or penetrative role.

* Acceptable male partners included prostitutes

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-penet ...

, and entertainers, whose lifestyle placed them in the nebulous social realm of ''infamia

In ancient Roman culture, ''infamia'' (''in-'', "not," and ''fama'', "reputation") was a loss of legal or social standing. As a technical term of Roman law, ''infamia'' was an official exclusion from the legal protections enjoyed by a Roman citize ...

'', excluded from the normal protections accorded to a citizen even if they were technically free.

* Although Roman men in general seem to have preferred youths between the ages of 12 and 20 as sexual partners, freeborn male minors were off limits, though professional prostitutes and entertainers might remain sexually available well into adulthood.

* By the end of the first century, Londinium

Londinium, also known as Roman London, was the capital of Roman Britain during most of the period of Roman rule. It was originally a settlement established on the current site of the City of London around AD 47–50. It sat at a key cross ...

the city was dotted with lupanaria ('wolf dens' or public pleasure houses), fornices (brothels) and thermiae (hot baths).

2nd century

* 117 – Emperor

* 117 – Emperor Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman '' municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania ...

, ruled Britain from 117 to 138. Hadrian was not only a peacemaker, he was also the first leader of Rome to make it clear that he was in today's language what we would call ''gay''. Many predecessors had taken male lovers, as was possible in Roman society. Hadrian was unique however in making his love "official" in a way that no other emperor had before him. Hadrian had an openly sexual relationship with a beautiful youth, Antinous

Antinous, also called Antinoös, (; grc-gre, Ἀντίνοος; 27 November – before 30 October 130) was a Greek youth from Bithynia and a favourite and probable lover of the Roman emperor Hadrian. Following his premature death before his ...

. When Antinous drowned in AD 130, Hadrian made Antinous

Antinous, also called Antinoös, (; grc-gre, Ἀντίνοος; 27 November – before 30 October 130) was a Greek youth from Bithynia and a favourite and probable lover of the Roman emperor Hadrian. Following his premature death before his ...

into a god, publicly commemorated him across the empire, created a city Antinopolis in his name and created a religious cult equivalent at the time to Christianity in his name.

3rd century

* 208 – The Roman Empire was ruled from Britain for a brief period in AD 208–211.4th century

* 312 – Roman Empire began to accept Christianity with the first emperor to convert to Christianity,Emperor Constantine

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

. Along with his bishops, monks and missionaries an endless loop of alternating permissiveness and homosexual censure in the Roman world began.

* Eusebius of Caesarea

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christi ...

wrote that "Among the Gauls, the young men marry each other (gamountai) with complete freedom. In doing this, they do not incur any reproach or blame, since this is done according to custom amongst them."

* Temples devoted to the goddess Cybele

Cybele ( ; Phrygian: ''Matar Kubileya/Kubeleya'' "Kubileya/Kubeleya Mother", perhaps "Mountain Mother"; Lydian ''Kuvava''; el, Κυβέλη ''Kybele'', ''Kybebe'', ''Kybelis'') is an Anatolian mother goddess; she may have a possible forer ...

are present in Britain, including sites that are now Catterick and Corbridge

Corbridge is a village in Northumberland, England, west of Newcastle and east of Hexham. Villages nearby include Halton, Acomb, Aydon and Sandhoe.

Etymology

Corbridge was known to the Romans as something like ''Corstopitum'' or ''Coriosopit ...

. Archeology in Catterick has located the remains of a Galla; one of a priesthood to Cybele who could be understood in today's language as being transgender

A transgender (often abbreviated as trans) person is someone whose gender identity or gender expression does not correspond with their sex assigned at birth. Many transgender people experience dysphoria, which they seek to alleviate through tr ...

.

5th century

* 410 – Following the departure of the Romans,Jutes

The Jutes (), Iuti, or Iutæ ( da, Jyder, non, Jótar, ang, Ēotas) were one of the Germanic tribes who settled in Great Britain after the departure of the Romans. According to Bede, they were one of the three most powerful Germanic nation ...

, Angles

The Angles ( ang, Ængle, ; la, Angli) were one of the main Germanic peoples who settled in Great Britain in the post-Roman period. They founded several kingdoms of the Heptarchy in Anglo-Saxon England. Their name is the root of the name ' ...

, Frisians

The Frisians are a Germanic ethnic group native to the coastal regions of the Netherlands and northwestern Germany. They inhabit an area known as Frisia and are concentrated in the Dutch provinces of Friesland and Groningen and, in Germany, E ...

and Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

arrived at different times and regions, bringing with them their indigenous sexual traditions. (Tacitus previously described North Germanic tribes punishing homosexuality by drowning the offender in a bog.) There was no specific mention of homosexuality in Anglo-Saxon law

Anglo-Saxon law (Old English ''ǣ'', later ''lagu'' "law"; dōm "decree, judgment") is a body of written rules and customs that were in place during the Anglo-Saxon period in England, before the Norman conquest. This body of law, along with earl ...

(which was in place during the Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened wit ...

period in England, before the Norman conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conqu ...

) until the seventh century.

6th century

* Welsh King Maelgwn (Malgo) ofGwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, and ...

ruled. Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth ( la, Galfridus Monemutensis, Galfridus Arturus, cy, Gruffudd ap Arthur, Sieffre o Fynwy; 1095 – 1155) was a British cleric from Monmouth, Wales and one of the major figures in the development of British historiography ...

in his pseudohistorical book ''History of the Kings of Britain

''Historia regum Britanniae'' (''The History of the Kings of Britain''), originally called ''De gestis Britonum'' (''On the Deeds of the Britons''), is a pseudohistorical account of British history, written around 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. ...

'' described the king as one of the handsomest of men in Britain, a great scourge of tyrants, and a man of great strength, extraordinary munificence, and matchless valour, but addicted very much to the detestable vice of sodomy, by which he made himself abominable to God.

* 597 – Christianity did not formally arrive in Britain until 597, when Augustine of Canterbury

Augustine of Canterbury (early 6th century – probably 26 May 604) was a monk who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597. He is considered the "Apostle to the English" and a founder of the English Church.Delaney '' ...

arrived in Britain to convert the Germanic Anglo Saxons (Jutes

The Jutes (), Iuti, or Iutæ ( da, Jyder, non, Jótar, ang, Ēotas) were one of the Germanic tribes who settled in Great Britain after the departure of the Romans. According to Bede, they were one of the three most powerful Germanic nation ...

, Angles

The Angles ( ang, Ængle, ; la, Angli) were one of the main Germanic peoples who settled in Great Britain in the post-Roman period. They founded several kingdoms of the Heptarchy in Anglo-Saxon England. Their name is the root of the name ' ...

, Frisians

The Frisians are a Germanic ethnic group native to the coastal regions of the Netherlands and northwestern Germany. They inhabit an area known as Frisia and are concentrated in the Dutch provinces of Friesland and Groningen and, in Germany, E ...

and Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

) to Christianity, thus confirming the prohibition of homosexuality, which was already punishable by death in Germanic societies.

8th century

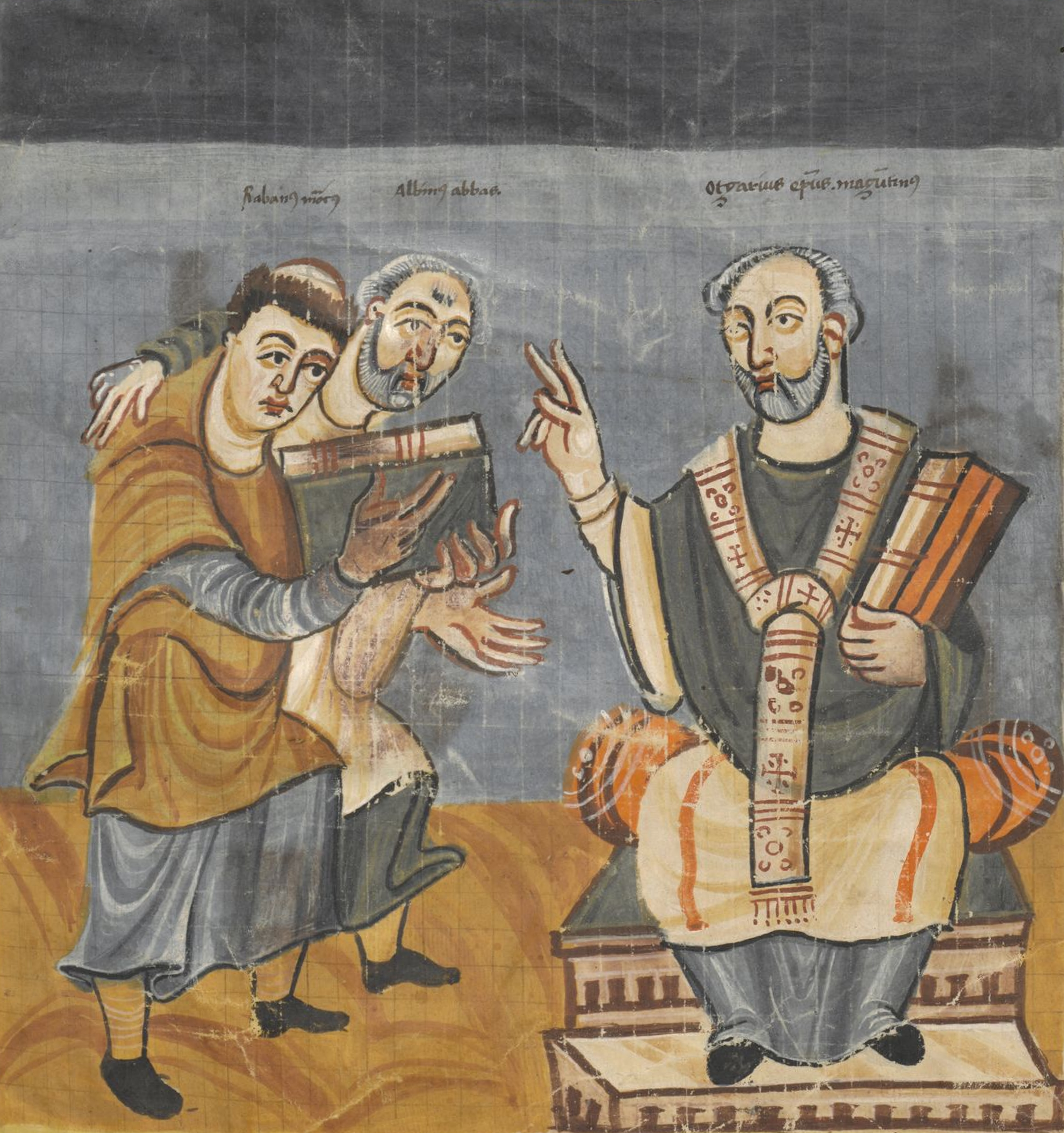

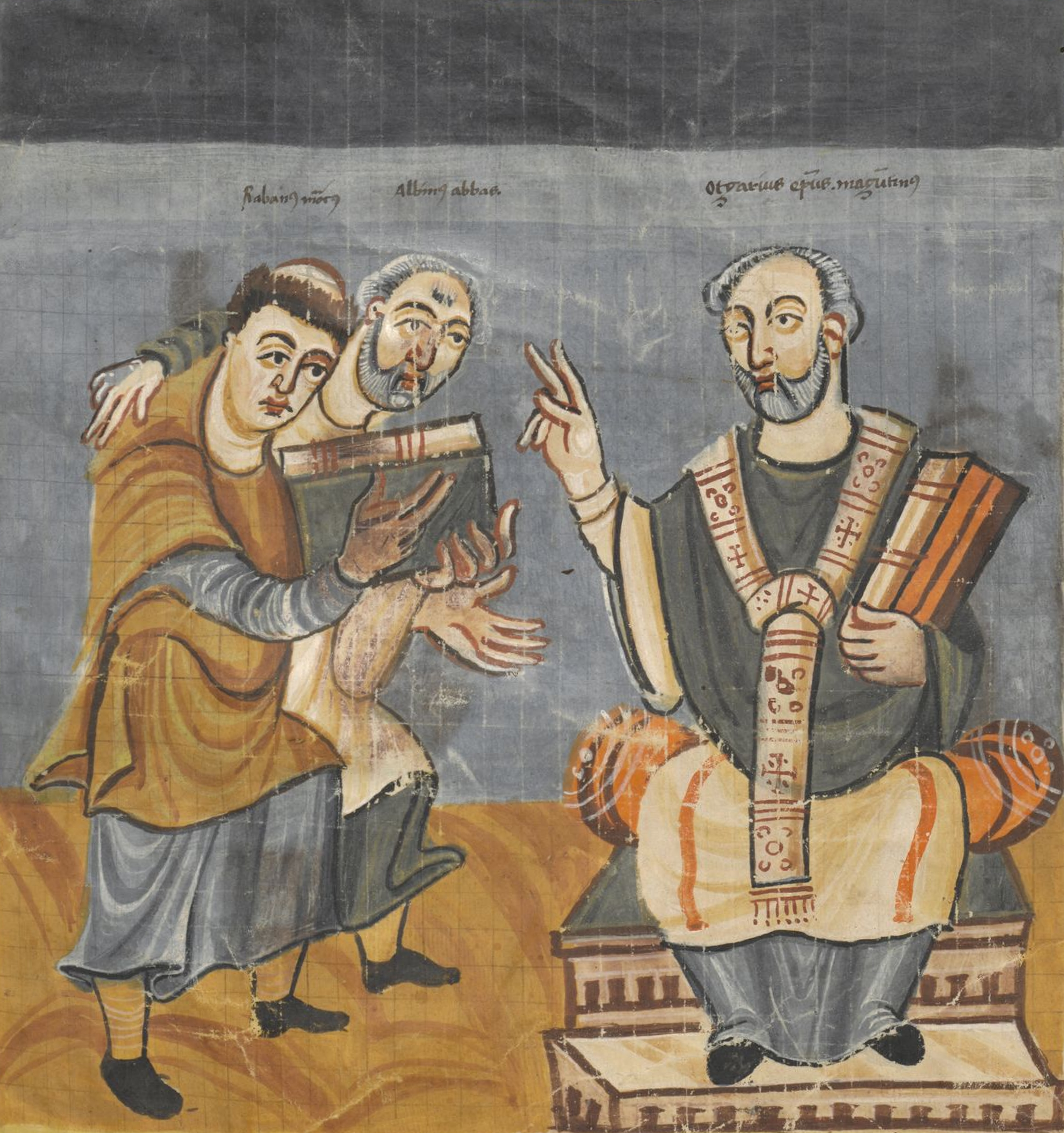

* 797 – During theCarolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. It occurred from the late 8th century to the 9th century, taking inspiration from the Christian Roman Empire of th ...

, Alcuin of York

Alcuin of York (; la, Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; 735 – 19 May 804) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student o ...

, an abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The fe ...

affectionately known as David, wrote love poems to other monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedicat ...

s in spite of numerous church laws condemning homosexuality. Historians agree that Alcuin at times "comes perilously close to communicating openly his same-sex desires", and this reflects the erotic subculture of the Carolingian monastic.

11th century

* 1050–1150 – HistorianJohn Boswell

John Eastburn Boswell (March 20, 1947December 24, 1994) was an American historian and a full professor at Yale University. Many of Boswell's studies focused on the issue of religion and homosexuality, specifically Christianity and homosexuality. ...

called the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD 1500 ...

the time of the 'Triumph of Ganymede' and finds evidence for a "reappearance for the first time since the decline of Rome of "what might be called a gay subculture" between 1050 and 1150 which completely disappears by 1300.

* 1056–1100 – William II of England

William II ( xno, Williame; – 2 August 1100) was King of England from 26 September 1087 until his death in 1100, with powers over Normandy and influence in Scotland. He was less successful in extending control into Wales. The third so ...

inherited the throne on his father William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 1087 ...

's death in 1087. Described as red haired, muscular and stocky and a taste for the latest fashion (including at shoes that curled up at the toe), he never married or produced heirs. William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury ( la, Willelmus Malmesbiriensis; ) was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. He has been ranked among the most talented English historians since Bede. Modern historian C. Warren Hollister described him as "a ...

, the foremost English historian of the 12th century. described the King as "being in lust with Ranulf Flambard

Ranulf Flambard ( c. 1060 – 5 September 1128) was a medieval Norman Bishop of Durham and an influential government minister of King William Rufus of England. Ranulf was the son of a priest of Bayeux, Normandy, and his nickname Flambard m ...

". He described the men of court having flamboyant tunics, pointed shoes, and hair down their backs like whores. He said court was full of "sodimites" and that William's death while hunting was judgement for his sins. Sodomy at this time however related to any sexual practice outside of marriage, and therefore does not necessarily refer to homosexuality.

12th century

* 1102 – The Council of London ( Roman Catholic church council of the church in England) took measures to encourage the English public to believe that homosexuality wassin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

ful.

13th century

* 1290 – Publication ofFleta

''Fleta'' is a treatise on the common law of England. It was written in Latin with the sub-title ''seu Commentarius juris Anglicani''. The anonymous author of the book is sometimes referred to as "Fleta", although this is not in fact a person's na ...

, first book to suggest a punishment for homosexuality in English law. The 'Fleta' required 'sodomites' to be punished by being buried alive, whilst the 'Britton' advocated burning. No evidence exists that the punishments were ever carried out.

* 1297 – Edward II of England

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

(1307–1337) and his favourite, his closest political and emotional ally and lover Piers Gaveston

Piers Gaveston, Earl of Cornwall (c. 1284 – 19 June 1312) was an English nobleman of Gascon origin, and the favourite of Edward II of England.

At a young age, Gaveston made a good impression on King Edward I, who assigned him to the househo ...

, met. At 16 years old, Edward thus began a history of conflict with the nobility, who repeatedly banished Gaveston, the Earl of Cornwall

The title of Earl of Cornwall was created several times in the Peerage of England before 1337, when it was superseded by the title Duke of Cornwall, which became attached to heirs-apparent to the throne.

Condor of Cornwall

*Condor of Cornwall, ...

, until Edward was king and could keep him reinstated. Gaveston's abuse of that power led to dangerous tensions with the barons who helped run the country and resulted in Gaveston's capture and eventual execution. After his death in 1312, Edward "constantly had prayers said for aveston'ssoul; he spent a lot of money on Gaveston's tomb".

14th century

* 1315–1317 –King Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

had Piers Gaveston's embalmed body buried, two and a half years after his death. Edward moved on with a growing infatuation with Roger d'Amory

Roger Damory, Lord d'Amory, Baron d'Amory in Ireland, (d. bef. 14 March 1321/1322) was a nobleman and Constable of Corfe Castle.

He was the younger son of Sir Robert D'Amory, Knight, of Bucknell and Woodperry, Oxfordshire. Sir Roger also posses ...

which can be tracked from the extensive list of gifts, grants, wardship and land. By 1317 Damory was the most important man at court and the King's 'favourite'. It is unknown whether Roger Damory was Edward II's lover.

* 1320 – King Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

formed a close relationship with another good looking favorite and aide, Hugh Despenser, who manoeuvred into the affections of King Edward, displacing Roger d'Amory. This came much to the dismay of the baronage as they saw him both taking their rightful places at court at best, and at worst being the new, worse Gaveston. By 1320 Despenser's greed was running free. He also supposedly vowed revenge on Roger Mortimer, because Mortimer's grandfather had killed his own grandfather.

* 1321 – Despenser had earned many enemies in every stratum of society, from King Edward's wife Queen Isabella in France, to the barons, to the common people. There was even a plot to kill Despenser by sticking his wax likeness with pins.

* 1326 – While Isabella was in France to negotiate between her husband and the French king, she formed a liaison with Roger Mortimer and began planning an invasion of England in September 1326. The majority of the nobility rallied to them throughout September and October, preferring to stand with them rather than King Edward and Despenser. Despenser fled west with the King, with a sizeable sum from the treasury, but the escape was unsuccessful. The King and Despenser were deserted by most of their followers, and were captured near Neath

Neath (; cy, Castell-nedd) is a market town and community situated in the Neath Port Talbot County Borough, Wales. The town had a population of 50,658 in 2011. The community of the parish of Neath had a population of 19,258 in 2011. Histori ...

in mid-November.

* 1337 – King Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

was placed in captivity and later forced to abdicate in favour of his son Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ro ...

. The popular story that the king was then assassinated by having a red-hot poker thrust into his anus has no basis in accounts recorded by Edward's contemporaries. Despenser was brought to trial and was found guilty on many charges. He was sentenced to death and was dragged naked through the streets, for the crowd's mistreatment. He was made a spectacle, which included writing on his body biblical verses against the capital sins he was accused of. Then he was hanged as a mere commoner, yet released before asphyxiation killed him. In Froissart

Jean Froissart (Old and Middle French: ''Jehan'', – ) (also John Froissart) was a French-speaking medieval author and court historian from the Low Countries who wrote several works, including ''Chronicles'' and ''Meliador'', a long Arthurian ...

's account of his execution, Despenser was then tied firmly to a ladder and his genitals sliced off and burned while he was still conscious. His entrails were slowly pulled out; finally, his heart was cut out and thrown into a fire. Froissart (or, rather, Jean le Bel

Jean Le Bel (c. 1290 – 15 February 1370) was a chronicler from Liège.

Biography

Jean Le Bel's father, Gilles le Beal des Changes, was an alderman of Liège. Jean entered the church and became a canon of the cathedral church, but he and his b ...

's chronicle, on which he relied) is the only source to mention castration; other contemporary accounts have Despenser hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the reign of King Henry III ( ...

, which usually did not involve castration.

* 1395 – John Rykener, known also as Johannes Richer and Eleanor, a transvestite

Transvestism is the practice of dressing in a manner traditionally associated with the opposite sex. In some cultures, transvestism is practiced for religious, traditional, or ceremonial reasons. The term is considered outdated in Western c ...

prostitute

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in Sex work, sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, n ...

working mainly in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a major s ...

(near Cheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, which forms part of the A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St. Martin's Le Grand with Poultry. Near its eastern end at Bank junction, where ...

), but also active in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, was arrested for cross-dressing

Cross-dressing is the act of wearing clothes usually worn by a different gender. From as early as pre-modern history, cross-dressing has been practiced in order to disguise, comfort, entertain, and self-express oneself.

Cross-dressing has play ...

and interrogated.

16th century

* 1533 – King

* 1533 – King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagr ...

passed the Buggery Act 1533

The Buggery Act 1533, formally An Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie (25 Hen. 8 c. 6), was an Act of the Parliament of England that was passed during the reign of Henry VIII.

It was the country's first civil sodomy law, such offe ...

making all male–male sexual activity punishable by death. Buggery related only to intercourse '' per anum'' by a man with a man or woman or intercourse '' per anum'' or '' per vaginum'' by either a man or a woman with an animal. Other forms of "unnatural intercourse" amounted to indecent assault

Indecent assault is an offence of aggravated assault in some common law-based jurisdictions. It is characterised as a sex crime and has significant overlap with offences referred to as sexual assault.

England and Wales

Indecent assault was a broa ...

or gross indecency Gross indecency is a crime in some parts of the English-speaking world, originally used to criminalize sexual activity between men that fell short of sodomy, which required penetration. The term was first used in British law in a statute of the B ...

, but did not constitute buggery. The lesser offence of "attempted buggery" was punished by two years of jail and often horrific time on the pillory

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, formerly used for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. The pillory is related to the stocks ...

.

* 1541 – The Buggery Act 1533

The Buggery Act 1533, formally An Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie (25 Hen. 8 c. 6), was an Act of the Parliament of England that was passed during the reign of Henry VIII.

It was the country's first civil sodomy law, such offe ...

only ran until the end of the parliament. The law was re-enacted three times, and then in 1541 it was enacted to continue in force "for ever".Bailey, 147–148, and H. Montgomery Hyde, ''The Love That Dared Not Speak Its Name: A Candid History of Homosexuality in Britain'' (Boston: Little, Brown, 1970) ritish title: ''The Other Love''/ref>

* 1543 – Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagr ...

gives royal assent to the Laws in Wales Act 1542, extending the buggery law into Wales.

* 1547 – King Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first En ...

's first Parliament repealed all felonies created in the last reign of King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagr ...

.

* 1548 – The provisions of the Buggery Act 1533

The Buggery Act 1533, formally An Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie (25 Hen. 8 c. 6), was an Act of the Parliament of England that was passed during the reign of Henry VIII.

It was the country's first civil sodomy law, such offe ...

were given new force, with minor amendments. The penalty for buggery remained death, but goods and lands were not forfeit, and the rights of wives and heirs were safeguarded.

* 1553 – Mary Tudor ascends the English throne and repealed the Buggery Act 1533

The Buggery Act 1533, formally An Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie (25 Hen. 8 c. 6), was an Act of the Parliament of England that was passed during the reign of Henry VIII.

It was the country's first civil sodomy law, such offe ...

during her brief reign of 1553–1558.

* 1558 – Elizabeth I ascended the English throne and reinstated the sodomy laws of 1533 (not 1548), which were then given permanent force until 1828 when replaced with the Offences Against the Person Act 1828

The Offences Against the Person Act 1828 (9 Geo. 4 c. 31) (also known as Lord Lansdowne's Act) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It consolidated provisions in the law related to offences against ...

.

* 1580 – King James VI of Scotland, King James I England had romantic relationships with three men: Esmé Stewart, Robert Carr

Leonard Robert Carr, Baron Carr of Hadley, (11 November 1916 – 17 February 2012) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Home Secretary from 1972 to 1974. He served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for 26 years, and later se ...

and George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, 28 August 1592 – 23 August 1628), was an English courtier, statesman, and patron of the arts. He was a favourite and possibly also a lover of King James I of England. Buckingham remained at the ...

. In 1580 at 14 years old, King James I of England began a relationship with Franco-Scottish Lord Esmé Stewart, 1st Duke of Lennox

Esmé Stewart, 1st Duke of Lennox, 1st Earl of Lennox, 6th Seigneur d'Aubigny, (26 May 1583) of the Château d'Aubigny at Aubigny-sur-Nère in the ancient province of Berry, France, was a Roman Catholic French nobleman of Scottish ancestry ...

. Lennox was a relative and 24 years senior to James, married and the father of 5 children. The influence Lennox his "favourite" had on politics, and the resentment at the wealth they acquired, became major political issues during his reign. Scottish nobles ousted Lennox by luring the young king to Ruthven Castle as a guest but then imprisoned him for ten months. The Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their na ...

nobles forced King James to banish Lennox to France. Lennox and James remained in secret contact. Lennox remained in France. He died in Paris in 1583. William Schaw

William Schaw (c. 1550–1602) was Master of Works to James VI of Scotland for building castles and palaces, and is claimed to have been an important figure in the development of Freemasonry in Scotland.

Biography

William Schaw was the second ...

took Lennox's heart back to James in Scotland, since in life its true place had been with the King.

17th century

* 1682 – A same-sex marriage is annulled.Arabella Hunt

Arabella Hunt (1662–1705) was an English vocalist and lutenist, celebrated for her beauty and talents.

Early life

Arabella Hunt was born in London on 27 February 1662 to Richard and Elizabeth Hunt. She sang at court and is recorded to have per ...

had married "James Howard" two years earlier but the marriage was annulled on the ground that Howard was in fact Amy Poulter, a 'perfect woman in all her parts', and two women could not validly marry.

* 1690 – King William III of England

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 16508 March 1702), also widely known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from the ...

had several close, male associates, including two Dutch courtiers to whom he granted English titles: Hans Willem Bentinck became Earl of Portland

Earl of Portland is a title that has been created twice in the Peerage of England, firstly in 1633 and secondly in 1689. What proved to be a long co-held title, Duke of Portland, was created in 1716 and became extinct in 1990 upon the death of ...

and Arnold Joost van Keppel was created Earl of Albemarle

Earl of Albemarle is a title created several times from Norman times onwards. The word ''Albemarle'' is derived from the Latinised form of the French county of ''Aumale'' in Normandy (Latin: ''Alba Marla'' meaning "White Marl", marl being a typ ...

. These relationships with male friends and his apparent lack of more than one female mistress led William's enemies to suggest that he might prefer homosexual relationships. Keppel was 20 years William's junior, described as strikingly handsome, and rose from being a royal page to an earldom with some ease.

* 1697 – William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland

Hans William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland, (20 July 164923 November 1709) was a Dutch and English nobleman who became in an early stage the favourite of William, Prince of Orange, Stadtholder in the Netherlands, and future King of England. ...

wrote to King William III that "the kindness which your Majesty has for a young man, and the way in which you seem to authorise his liberties ... make the world say things I am ashamed to hear".Van der Kiste, 202–203 This, he said, was "tarnishing a reputation which has never before been subject to such accusations". William tersely dismissed these suggestions, saying, "It seems to me very extraordinary that it should be impossible to have esteem and regard for a young man without it being criminal."

18th century

* 1711 –Anne, Queen of Great Britain

Anne (6 February 1665 – 1 August 1714) was Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland from 8 March 1702 until 1 May 1707. On 1 May 1707, under the Acts of Union, the kingdoms of England and Scotland united as a single sovereign state known as ...

ended a long-lasting intimate friendship with Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough

Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough, Princess of Mindelheim, Countess of Nellenburg (née Jenyns, spelt Jennings in most modern references; 5 June 1660 (Old Style) – 18 October 1744), was an English courtier who rose to be one of th ...

. The "Queen's Favourite" hoped to wield power equal to that of a government minister. When their relationship soured, she blackmailed Anne with letters revealing their intimacy, and accused her of perverting the course of national affairs by keeping lesbian favourites. Anne and Sarah had invented petnames for themselves during their youths which they continued to use after Anne became queen: ''Mrs Freeman'' (Sarah) and ''Mrs Morley'' (Anne). Effectively a business manager, Sarah had control over the queen's position, from her finances to people admitted to the royal presence.

* 1722 – John Quincy writes about lesbianism in his second edition of the ''Lexicon Physico Medicum''. According to Quincy, ''confricatrices'' or ''confictrices'' were terms used by authors for lesbians "who have learned to titulate one another with their clitoris

The clitoris ( or ) is a female sex organ present in mammals, ostriches and a limited number of other animals. In humans, the visible portion – the glans – is at the front junction of the labia minora (inner lips), above the ope ...

, in imitation of venereal intercourse with men".

*1724 – Margaret Clap

Margaret Clap (died c. 1726), better known as Mother Clap, ran a coffee house from 1724 to 1726 in Holborn, Middlesex, a short distance from the City of London. As well as running a molly house (an inn or tavern primarily frequented by homosexua ...

, better known as ''Mother Clap'', ran a coffee house from 1724 to 1726 in Holborn

Holborn ( or ) is a district in central London, which covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part ( St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Ward of Farringdon Without in the City of London.

The area has its roots ...

, London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a major s ...

. The coffee house served as a Molly House

Molly-house was a term used in 18th- and 19th-century Britain for a meeting place for homosexual men. The meeting places were generally taverns, public houses, coffeehouses or even private rooms where men could either socialise or meet possible s ...

for the underground gay community. Her house was popular, being well known within the gay community. She cared for her customers, and catered especially to the gay men who frequented it. She was known to have provided "beds in every room of the house" and commonly had "thirty or forty of such Kind of Chaps every Night, but more especially on Sunday Nights".

*1726 – Three men (Gabriel Lawrence, William Griffin, and Thomas Wright) were hanged at

*1726 – Three men (Gabriel Lawrence, William Griffin, and Thomas Wright) were hanged at Tyburn

Tyburn was a manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman roads to the west (modern Edgware Road) and south (modern Ox ...

for sodomy following a raid of Margaret Clap's Molly House.

*1727 – Charles Hitchen

Charles Hitchen, also mentioned as Charles Hitchin in other sources, (''c.'' 1675 – 1727) was a "thief-taker" (private policeman) and under-marshal of the City of London in the early 18th century, also, famously tried for homosexual acts and ...

, a London Under City Marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used for elevated o ...

, was convicted of attempted sodomy

Sodomy () or buggery (British English) is generally anal or oral sex between people, or sexual activity between a person and a non-human animal ( bestiality), but it may also mean any non- procreative sexual activity. Originally, the term ''sod ...

at a Molly House

Molly-house was a term used in 18th- and 19th-century Britain for a meeting place for homosexual men. The meeting places were generally taverns, public houses, coffeehouses or even private rooms where men could either socialise or meet possible s ...

. Hitchen had abused his position of power to extort bribes from brothels and pickpockets to prevent arrest, and he particularly leaned on the thieves to make them fence their goods through him. Hitchen had frequently picked up soldiers for sex, but had eluded prosecution by the Society for the Reformation of Manners

The Society for the Reformation of Manners was founded in the Tower Hamlets area of London in 1691.Molly House

Molly-house was a term used in 18th- and 19th-century Britain for a meeting place for homosexual men. The meeting places were generally taverns, public houses, coffeehouses or even private rooms where men could either socialise or meet possible s ...

, Julius Caesar Taylor's, Tottenham Court Road

Tottenham Court Road (occasionally abbreviated as TCR) is a major road in Central London, almost entirely within the London Borough of Camden.

The road runs from Euston Road in the north to St Giles Circus in the south; Tottenham Court Road tu ...

, Jenny Greensleeves' Molly House, Durham Yard, off The Strand, The Golden Ball, Bond's Stables, off Chancery Lane

Chancery Lane is a one-way street situated in the ward of Farringdon Without in the City of London. It has formed the western boundary of the City since 1994, having previously been divided between the City of Westminster and the London Boro ...

, Royal Oak Molly House, Giltspur Street, Smithfield and Three Tobacco Rolls Covent Garden were operating in London.

*1730 – The term "lesbian" to describe same sex relationships between women comes into use around the 1730s.

*1735 – Conyers Place wrote "Reason Insufficient Guide to Conduct Mankind in Religion".

*1736 – Love letters from Lord John Hervey to Stephen Fox

Sir Stephen Fox (27 March 1627 – 28 October 1716) of Farley in Wiltshire, of Redlynch Park in Somerset, of Chiswick, Middlesex and of Whitehall, was a royal administrator and courtier to King Charles II, and a politician, who rose from ...

PC, a British peer and Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members ofte ...

, show that they had been living in a homosexual relationship for a period of ten years, from 1726 to 1736.

*1749 – Thomas Cannon

Thomas Cannon (1720–?)Gladfelder, Hal ''Fanny Hill in Bombay: The Making and Unmaking of John Cleland'', Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012, p. 46 of Gray's Inn was an English author of the 18th century. He wrote what may be the earliest ...

wrote "Ancient and Modern Pederasty Investigated and Exemplified".

*1772 – The first public debate about homosexuality began during the trial of Captain Robert Jones who was convicted of the capital offence of sodomising a thirteen-year-old boy. The debate during the case and with the background of the 1772 Macaroni

Macaroni (, Italian: maccheroni) is dry pasta shaped like narrow tubes.Oxford DictionaryMacaroni/ref> Made with durum wheat, macaroni is commonly cut in short lengths; curved macaroni may be referred to as elbow macaroni. Some home machine ...

prosecutions considered Christian intolerance of homosexuality and the human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hum ...

of men who were homosexual. Jones was acquitted and received a pardon on condition that he leave the country. He ended up living in grandeur with his footman

A footman is a male domestic worker employed mainly to wait at table or attend a coach or carriage.

Etymology

Originally in the 14th century a footman denoted a soldier or any pedestrian, later it indicated a foot servant. A running footman del ...

at Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of th ...

, in the South of France

Southern France, also known as the South of France or colloquially in French as , is a defined geographical area consisting of the regions of France that border the Atlantic Ocean south of the Marais Poitevin,Louis Papy, ''Le midi atlantique'', A ...

.

*1773 – Charles Crawford wrote "A Dissertation on the Phaedon of Plato".

*1776 –18th century London gay bar, Harlequin (Nag's Head Court, Covent Garden) was operating

*1778 - Eleanor Butler & Sarah Ponsonby, known as The Ladies of Llangollen

The "Ladies of Llangollen", Eleanor Butler (1739–1829) and Sarah Ponsonby (1755–1831), were two upper-class Irish women whose relationship scandalised and fascinated their contemporaries. The pair moved to a Gothic house in Llangollen, N ...

, were two upper-class Irish women whose relationship scandalised and fascinated their contemporaries during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The pair moved to a Gothic house in Llangollen

Llangollen () is a town and community, situated on the River Dee, in Denbighshire, Wales. Its riverside location forms the edge of the Berwyn range, and the Dee Valley section of the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beau ...

, North Wales, in 1780 after leaving Ireland to escape the social pressures of conventional marriages. Over the years, numerous distinguished visitors called upon them. Guests included Shelley, Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and h ...

, Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

and Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

, who wrote a sonnet about them.

*1785 – Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

becomes one of the first people to argue for the decriminalisation of sodomy in England, which was punishable by hanging. The essay ''Offences Against One's Self'', written about 1785, argued for the liberalisation of laws prohibiting homosexual sex. He argued that homosexual acts did not weaken men, nor threaten population or marriage. The essay was never published in his lifetime.

*1797 – The ''Encyclopedia Britannica

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into article ...

'' published a brief mention of homosexuality in the article about Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

.

19th century

*1800 –

*1800 – William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. ...

paints "Lot and His Daughters". The Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek ; Hebrew: בְּרֵאשִׁית ''Bəreʾšīt'', "In hebeginning") is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its first word, ( "In the beginning"). ...

in chapters 11–14 and 18–19 describes Lot and his family, living through the fire and brimstone

Fire and brimstone ( ''gofrit va’esh'', grc, πυρὸς καὶ θείου) is an idiomatic expression referring to God's wrath found in both the Hebrew Bible and the Christian New Testament. In the Bible, it often appears in reference ...

sent against Sodom and Gomorrah

Sodom and Gomorrah () were two legendary biblical cities destroyed by God for their wickedness. Their story parallels the Genesis flood narrative in its theme of God's anger provoked by man's sin (see Genesis 19:1–28). They are mentioned frequ ...

apparently for either rape, transgression of the laws of hospitality, or homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peop ...

. "Lot and His Daughters" however portrays the part of the story that involves incest, not homosexuality: the story in Genesis describes how the daughters of Lot, along the road as they fled from Sodom and Gomorrah, got their father drunk so that after he fell asleep they could have sex with him and in this way get children from him.

*1806 – Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other English counties, functions have ...

gentlewoman Anne Lister

Anne Lister (3 April 1791 – 22 September 1840) was an English diarist, famous for revelations for which she was dubbed "the first modern lesbian".

Lister was from a minor landowning family at Shibden in Calderdale, West Riding of Yorkshire, ...

starts writing love letters to and from Eliza Raine. Lister actively participated in and wrote about her lesbian relationships in an encrypted diary. Although she did not use the word lesbian, at age thirty, she wrote, "I love and only love the fairer sex and thus, beloved by them in turn my heart revolts from any other love but theirs."

*1810 – The nineteenth century began with a wave of prosecutions against homosexual men. On 14 January, a farmer in West Yorkshire wrote in his diary that capital punishment seemed an unacceptably cruel response to a sexual behavior that nature or God had ordained in an individual. (The diary entry was discovered in 2020.) On 8 July, the Bow Street Runners

The Bow Street Runners were the law enforcement officers of the Bow Street Magistrates' Court in the City of Westminster. They have been called London's first professional police force. The force originally numbered six men and was founded in 1 ...

raided The White Swan, a tumbledown pub of Tudor origin near Drury Lane

Drury Lane is a street on the eastern boundary of the Covent Garden area of London, running between Aldwych and High Holborn. The northern part is in the borough of Camden and the southern part in the City of Westminster.

Notable landmarks

T ...

. Twenty-seven men were arrested on suspicion of sodomy and attempted sodomy.

*1811 – The Scottish court case ''Woods and Pirie vs Dame Cumming Gordon'' showed two teachers are accused of having a lesbian relationship by a pupil, claiming they had indecent sexual relationships. However, one judge found that sex between women was "equally imaginary with witchcraft, sorcery or carnal copulation with the devil", illustrating notions at the time that tied sexuality with masculinity.

*1812 – James Miranda Barry graduated from the Medical School of Edinburgh University as a doctor. Barry went on to serve as an army surgeon working overseas. Barry lived as a man but was found to be female-bodied upon his death in 1865.

*1828 – The Buggery Act 1533 was repealed and replaced by the Offences against the Person Act 1828

The Offences Against the Person Act 1828 (9 Geo. 4 c. 31) (also known as Lord Lansdowne's Act) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It consolidated provisions in the law related to offences against ...

. Buggery remained punishable by death.

*1833 – 24-year old actor Eliza Edwards is found dead. The corpse was taken to Guys Hospital for an autopsy, where it is discovered that they were 'a perfect man'.

*1835 – The last two men to be executed in Britain for buggery, James Pratt and John Smith

James Pratt (1805–1835), also known as John Pratt, and John Smith (1795–1835) were two London men who, in November 1835, became the last two to be executed for sodomy in England.Cook ''et al'' (2007), p. 109. Pratt and Smith were arrested in ...

, were arrested on 29 August in London after being spied upon while having sex in a private room; they were hanged on 27 November.

*1838 – Harry Stokes

Harry Stokes (c1799 – 15 October 1859) was a master bricklayer, beerhouse manager and special constable in Manchester. He was assigned a female gender at birth but lived as a man. Harry had two long-term relationships with women, both of whic ...

was a master bricklayer

A bricklayer, which is related to but different from a mason, is a craftsman and tradesman who lays bricks to construct brickwork. The terms also refer to personnel who use blocks to construct blockwork walls and other forms of masonry ...

, beerhouse A beerhouse was a type of public house

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the Unite ...

manager and special constable in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The tw ...

. He was assigned a female gender at birth but lived as a man. Harry had two long-term relationships with women, both of which lasted over 20 years. In 1838 and 1859 his gender variance

Gender variance or gender nonconformity is behavior or gender expression by an individual that does not match masculine or feminine gender norms. A gender-nonconforming person may be variant in their gender identity, being transgender or non-bin ...

became the subject of local and national newspaper articles in which he was described as a 'man-woman' and a 'female husband'.

*1852 – John Martin paints ''The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorah.'' Sodom was (supposedly) destroyed for the sin of sodomy

Sodomy () or buggery (British English) is generally anal or oral sex between people, or sexual activity between a person and a non-human animal ( bestiality), but it may also mean any non- procreative sexual activity. Originally, the term ''sod ...

, although a strong case has been made that violence against persons and transgression of the laws of hospitality, including a demand that he hand over his houseguests (who happened to be angels) to the ruffian citizens of the town, were more important at the time of the composition of the story in Genesis, chapter 19.

*1861 – The death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

for buggery was abolished when the Offences Against the Person Act 1828

The Offences Against the Person Act 1828 (9 Geo. 4 c. 31) (also known as Lord Lansdowne's Act) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It consolidated provisions in the law related to offences against ...

was replaced with the Offences Against the Person Act 1861. A total of 8921 men had been prosecuted since 1806 for sodomy

Sodomy () or buggery (British English) is generally anal or oral sex between people, or sexual activity between a person and a non-human animal ( bestiality), but it may also mean any non- procreative sexual activity. Originally, the term ''sod ...

with 404 sentenced to death and 56 executed. Homosexuality remained illegal until 1967 in England and Wales and 1980 in Scotland.

*1866 – Marriage was defined as being between a man and a woman (preventing future same-sex marriages

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same sex or gender. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 33 countries, with the most recent being Mexico, constituting ...

). In the case of ''Hyde v. Hyde and Woodmansee'' (a case of polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is married ...

), Lord Penzance

James Plaisted Wilde, 1st Baron Penzance, (12 July 1816 – 9 December 1899) was a noted British judge and rose breeder who was also a proponent of the Baconian theory that the works usually attributed to William Shakespeare were in fact writte ...

's judgment began "Marriage as understood in Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

is the voluntary union for life of one man and one woman, to the exclusion of all others."

*1871 – Ernest 'Stella' Boulton and Frederick 'Fanny' Park, two Victorian transvestites and suspected homosexuals

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peop ...

, appeared as defendants in the celebrated Boulton and Park

Thomas Ernest Boulton and Frederick William Park were two Victorian cross-dressers. In 1870, while in drag, they were arrested after leaving a London theatre. They were charged with conspiracy to commit sodomy, a crime that carried a maximum pr ...

trial in London, charged "with conspiring and inciting persons to commit an unnatural offence". The indictment was against Lord Arthur Clinton, Ernest Boulton, Frederic Park, Louis Hurt, John Fiske, Martin Cumming, William Sommerville and C. H. Thompson. The prosecution was unable to prove either that they had committed any homosexual offence or that men wearing women's clothing was an offence in English law. Lord Arthur Clinton killed himself before his trial.

*1872 – Sheridan Le Fanu publishes the novella ''

*1872 – Sheridan Le Fanu publishes the novella ''Carmilla

''Carmilla'' is an 1872 Gothic novella by Irish author Sheridan Le Fanu and one of the early works of vampire fiction, predating Bram Stoker's ''Dracula'' (1897) by 26 years. First published as a serial in '' The Dark Blue'' (1871–72), the ...

'', which depicts the tale of a lesbian vampire luring young women for her mother to sacrifice

*1883 – John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

, Baron Keynes of Tilton, CB FBA was born. Openly homosexual, Keynes a British economist whose ideas have profoundly affected the theory and practice of modern macroeconomics, as well as the economic policies of governments. He diarised his homosexual encounters and records that he had 65 encounters in 1909, 26 in 1910, 39 in 1911.

*1885 – The British Parliament enacted Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885

The Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 ( 48 & 49 Vict. c.69), or "An Act to make further provision for the Protection of Women and Girls, the suppression of brothels, and other purposes," was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, the lat ...

, section 11 of which, known as the Labouchere Amendment

Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, commonly known as the Labouchere Amendment, made "gross indecency" a crime in the United Kingdom. In practice, the law was used broadly to prosecute male homosexuals where actual sodomy (meaning ...

, prohibited gross indecency Gross indecency is a crime in some parts of the English-speaking world, originally used to criminalize sexual activity between men that fell short of sodomy, which required penetration. The term was first used in British law in a statute of the B ...

between males. It thus became possible to prosecute homosexuals for engaging in sexual acts where buggery or attempted buggery could not be proven.

*1885 – A collection of the poems of Sappho were translated and published in English by Henry Thornton Wharton as ''Sappho: Memoir, Text, and Selected Renderings''. Wharton maintained a homosexual interpretation of "Ode to Aphrodite".

*1889 – The Cleveland Street scandal

The Cleveland Street scandal occurred in 1889, when a homosexual male brothel and house of assignation on Cleveland Street, London, was discovered by police. The government was accused of covering up the scandal to protect the names of aristocr ...

occurred, when a homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to p ...

male brothel in Cleveland Street, Fitzrovia

Fitzrovia () is a district of central London, England, near the West End. The eastern part of area is in the London Borough of Camden, and the western in the City of Westminster. It has its roots in the Manor of Tottenham Court, and was urban ...

, London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a major s ...

, was raided by police after they discovered telegraph boys had been working there as rent boys. A number of aristocratic clients were discovered, including Lord Arthur Somerset, equerry

An equerry (; from French 'stable', and related to 'squire') is an officer of honour. Historically, it was a senior attendant with responsibilities for the horses of a person of rank. In contemporary use, it is a personal attendant, usually upo ...

to the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the ruler ...

. The Prince of Wales's son Prince Albert Victor

Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale (Albert Victor Christian Edward; 8 January 1864 – 14 January 1892) was the eldest child of the Prince and Princess of Wales (later King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra) and grandson of the re ...

and Lord Euston were also implicated in the scandal.

*Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to th ...

became the last jurisdiction in Europe to abolish the death penalty for same-sex sexual intercourse, which reduced the penalty to life imprisonment in a penitentiary.

*1895 – Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

, tried for gross indecency Gross indecency is a crime in some parts of the English-speaking world, originally used to criminalize sexual activity between men that fell short of sodomy, which required penetration. The term was first used in British law in a statute of the B ...

over a relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas

Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas (22 October 1870 – 20 March 1945), also known as Bosie Douglas, was an English poet and journalist, and a lover of Oscar Wilde. At Oxford he edited an undergraduate journal, ''The Spirit Lamp'', that carried a homoe ...

, was sentenced to two years in prison with hard labour.

* The gay English poet A. E. Housman

Alfred Edward Housman (; 26 March 1859 – 30 April 1936) was an English classical scholar and poet. After an initially poor performance while at university, he took employment as a clerk in London and established his academic reputation by pub ...

writes a poem about the trial of Oscar Wilde. Due to its content, it was not published until after Housman's death.

* Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

was accused of having committed "acts of gross immorality of the Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

type" while a cadet at Sandhurst. Churchill sued the accuser for defamation and was awarded £400 in damages. Throughout his life, Churchill showed little interest in women other than his wife, enjoyed the company of homosexuals, and was deeply attached to male friends and his long-standing secretary Edward Marsh, although there is no evidence of any physical relationships.

* 1897 – George Cecil Ives