Ku Klux Klan in Canada on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Ku Klux Klan is an organization that expanded operations into Canada, based on the second Ku Klux Klan established in the United States in 1915. It operated as a

The Ku Klux Klan is an organization that expanded operations into Canada, based on the second Ku Klux Klan established in the United States in 1915. It operated as a

Presidents

Presidents

In March 1922, an

In March 1922, an

Although distancing itself from the violence perpetrated by the Ku Klux Klan in the United States, the Ku Klux Klan in Canada was engaged in various campaigns threatening those who didn't conform to the Klan's beliefs. It resulted in significant property damage throughout Canada. Although there is little proof, the Klan was blamed for the razing of Saint-Boniface College in

Although distancing itself from the violence perpetrated by the Ku Klux Klan in the United States, the Ku Klux Klan in Canada was engaged in various campaigns threatening those who didn't conform to the Klan's beliefs. It resulted in significant property damage throughout Canada. Although there is little proof, the Klan was blamed for the razing of Saint-Boniface College in

Certificate of Incorporation

was approved every two years until 2003.

In a letter to the

In a letter to the  In October 1927 at a Ku Klux Klan meeting held at Regina City Hall, Maloney said he had received a letter from

In October 1927 at a Ku Klux Klan meeting held at Regina City Hall, Maloney said he had received a letter from

In July 1927, a Klan organizer claimed that there were 46,500 members in Saskatchewan. By late 1927, there were 2,300 members of the Ku Klux Klan in Moose Jaw.

In July 1927, a Klan organizer claimed that there were 46,500 members in Saskatchewan. By late 1927, there were 2,300 members of the Ku Klux Klan in Moose Jaw.

The Ku Klux Klan is an organization that expanded operations into Canada, based on the second Ku Klux Klan established in the United States in 1915. It operated as a

The Ku Klux Klan is an organization that expanded operations into Canada, based on the second Ku Klux Klan established in the United States in 1915. It operated as a fraternity

A fraternity (from Latin ''frater'': "brother"; whence, " brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club or fraternal order traditionally of men associated together for various religious or secular aims. Fraternit ...

, with chapters established in parts of Canada throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. The first registered provincial chapter was registered in Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

in 1925 by two Americans and a Torontonian. The organization was most successful in Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

, where it briefly influenced political activity and whose membership included a member of Parliament, Walter Davy Cowan

Walter Davy Cowan, D.D.S., (December 31, 1865 – September 28, 1934) was a Canadian politician in Saskatchewan and Ku Klux Klan member. Cowan served as Mayor of Regina and served as Conservative- Unionist Member of Parliament for Regina fr ...

.

Background

The conclusion of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

in 1865 resulted in the termination of the secessionist movement of the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

and the abolition of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. The United States entered a period of Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, during which the infrastructure destroyed during the civil war would be rebuilt, national unity would be restored, and freed slaves were guaranteed their civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

with the passage of the Reconstruction Amendments

The , or the , are the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments to the United States Constitution, adopted between 1865 and 1870. The amendments were a part of the implementation of the Reconstruction of the American South which oc ...

.

In December 1865, six veterans of the Confederate Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighti ...

established the Ku Klux Klan in Pulaski, Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

.

Presidents

Presidents Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

(1861–1865) and Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

(1865–1869) undertook a moderate approach to Reconstruction, but after the 1866 election resulted in the Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recons ...

controlling the policy of the 40th United States Congress

The 40th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1867, ...

, a harsher approach was adopted in which former Confederates were removed from power and freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom ...

were enfranchised. In July 1868, Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

passed the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

, addressing citizenship rights and granting equal protection under the law.

The 1868 presidential election victory by Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

, who supported Radical Republicans, further entrenched this approach. Under his presidency

A presidency is an administration or the executive, the collective administrative and governmental entity that exists around an office of president of a state or nation. Although often the executive branch of government, and often personified by ...

, the Fifteenth Amendment to the constitution was passed, prohibiting federal and state governments from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude". This was followed by three Enforcement Acts

The Enforcement Acts were three bills that were passed by the United States Congress between 1870 and 1871. They were criminal codes that protected African Americans’ right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, and receive equal protect ...

, criminal codes protecting African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

s and primarily targeting the Ku Klux Klan. It was the third act

Third Act is the third full-length album by the Swedish/Danish band Evil Masquerade.

Track listing

All songs written by Henrik Flyman.

Black Ravens Cry was released as a single in 2012 by Dark Minstrel Music

Personnel

;Evil Masquerade

*Hen ...

, also known as the "Ku Klux Klan Act", which resulted in the termination of the Ku Klux Klan by 1872 and prosecution of hundreds of Klan members.

The release of the film ''The Birth of a Nation

''The Birth of a Nation'', originally called ''The Clansman'', is a 1915 American silent epic drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and play ''The Clan ...

'' by D. W. Griffith

David Wark Griffith (January 22, 1875 – July 23, 1948) was an American film director. Considered one of the most influential figures in the history of the motion picture, he pioneered many aspects of film editing and expanded the art of the n ...

in 1915, glorifying the original Ku Klux Klan using historical revisionism

In historiography, historical revisionism is the reinterpretation of a historical account. It usually involves challenging the orthodox (established, accepted or traditional) views held by professional scholars about a historical event or times ...

, stoked resentment among some citizens and riots in cities where it screened. The day before Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated on various dates in the United States, Canada, Grenada, Saint Lucia, Liberia, and unofficially in countries like Brazil and Philippines. It is also observed in the Netherlander town of Leiden ...

in 1915, William Joseph Simmons and 15 of his friends established the second Ku Klux Klan atop Stone Mountain in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, ceremonially burning a cross to mark the occasion.

Expansion into Canada

In March 1922, an

In March 1922, an African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

man named Matthew Bullock fled North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

after the Ku Klux Klan had stated he was a wanted man, accusing him of inciting riots. His brother had been killed by Klansmen, who the ''Toronto Star

The ''Toronto Star'' is a Canadian English-language broadsheet daily newspaper. The newspaper is the country's largest daily newspaper by circulation. It is owned by Toronto Star Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary of Torstar Corporation and par ...

'' reported at the time had "threatened to send robed riders to fetch Bullock and whisk him back to the American south".

On 1 December 1924, C. Lewis Fowler of New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, John H. Hawkins of Newport, Virginia, and Richard L. Cowan of Toronto signed an agreement to establish the Knights of Ku Klux Klan of Canada. Funding responsibilities for the provincial organization were split equally among them, and each was a founding Imperial Officer of the Provincial Kloncillum, the governing body of the organization. Fowler travelled to Canada on 1 January 1925 to officially establish the organization. Cowan was the Imperial Wizard

The Grand Wizard (later the Grand and Imperial Wizard simplified as the Imperial Wizard and eventually, the National Director) referred to the national leader of several different Ku Klux Klan organizations in the United States and abroad.

The ti ...

(president), Hawkins the Imperial Klaliff (vice-president) and Chief of Staff, and Fowler the Imperial Kligrapp (secretary). They also split the organization's income equally. Fowler left Canada in 1926.

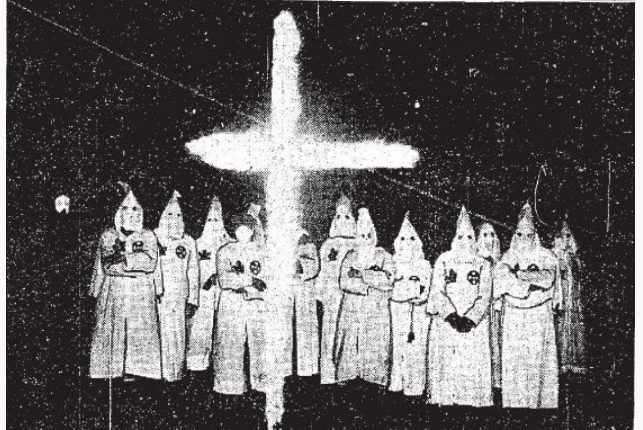

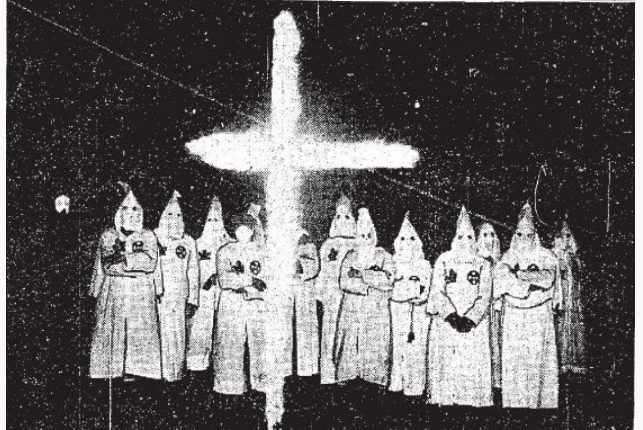

During the mid 1920s, Ku Klux Klan branches were established throughout Canada. According to historian James Pitsula, these groups observed the same racial ideology but had a narrower focus than those in the United States, primarily to preserve the "Britishness" of Canada with respect to ethnicity and religious affiliation. The Ku Klux Klan of Canada made efforts to distinguish itself from the American organization, which used a "spectacular level of violent criminality" against black Americans and the white Americans who supported them. Hawkins stated at a rally in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

that the Canadian Ku Klux Klan was not lawless, that it abided by the laws of the nation, but that it would promote changing those laws it didn't support or did "not meet the needs of the country". A 1925 photograph of garbed Canadian Klansmen published by the '' London Advertiser'' demonstrated that the Klan robes in Canada differed from those in the United States by including a maple leaf

The maple leaf is the characteristic leaf of the maple tree. It is the most widely recognized national symbol of Canada.

History of use in Canada

By the early 1700s, the maple leaf had been adopted as an emblem by the French Canadians along th ...

opposite the cross insignia.

One of the most prominent groups was the Ku Klux Klan of Kanada, whose main principles of white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White ...

and nationalism required members to pledge that they were white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

, gentile

Gentile () is a word that usually means "someone who is not a Jew". Other groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, sometimes use the term ''gentile'' to describe outsiders. More rarely, the term is generally used as a synonym fo ...

, and Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

. Organizers stated that the Ku Klux Klan was a Christian organization with "first allegiance to Canada and the Union Jack", disqualifying Jews from membership because they are not Christian, and Roman Catholics because their first allegiance is to the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

.

Although the KKK operated throughout Canada, it was most successful in Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

, where by the late 1920s its membership was over 25,000. Historian Allan Bartley states that this success was a result of opposition to liberal Government of Saskatchewan policy established by the entrenched Saskatchewan Liberal Party

The Saskatchewan Liberal Party is a liberal political party in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan.

The party was the provincial affiliate of the Liberal Party of Canada until 2009. It was previously one of the two largest parties in the provi ...

, which had held power in the province since its inception in 1905.

In 1991, Carney Nerland, a professed white supremacist, member of the Ku Klux Klan and leader of the Saskatchewan branch of the Church of Jesus Christ Christian Aryan Nation killed a Cree man, Leo LaChance, with an assault rifle. LaChance had entered Nerland's Prince Albert, Saskatchewan pawn shop to sell furs he had trapped.

Operations

Although distancing itself from the violence perpetrated by the Ku Klux Klan in the United States, the Ku Klux Klan in Canada was engaged in various campaigns threatening those who didn't conform to the Klan's beliefs. It resulted in significant property damage throughout Canada. Although there is little proof, the Klan was blamed for the razing of Saint-Boniface College in

Although distancing itself from the violence perpetrated by the Ku Klux Klan in the United States, the Ku Klux Klan in Canada was engaged in various campaigns threatening those who didn't conform to the Klan's beliefs. It resulted in significant property damage throughout Canada. Although there is little proof, the Klan was blamed for the razing of Saint-Boniface College in Saint Boniface, Winnipeg

St-Boniface (or Saint-Boniface) is a city ward and neighbourhood in Winnipeg. Along with being the centre of the Franco-Manitoban community, it ranks as the largest francophone community in Western Canada.

It features such landmarks as the St. B ...

, which resulted in 10 deaths, destruction of the building, and loss of all of its records and its library.

Before the official establishment of the Ku Klux Klan in Canada, Catholic churches and property throughout Canada were targets of arson

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, wate ...

, notably the Cathedral-Basilica of Notre-Dame de Québec

The Cathedral-Basilica of Notre-Dame de Québec ("Our Lady of Quebec City"), located at 16, rue de Buade, Quebec City, Quebec, is the primatial church of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Quebec. It is the oldest church in Canada and was th ...

in Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the metropolitan area had a population of 839,311. It is t ...

in 1922. These were attributed to the Ku Klux Klan.

Other violent acts associated with the Klan include the 1926 detonation of dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive made of nitroglycerin, sorbents (such as powdered shells or clay), and stabilizers. It was invented by the Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel in Geesthacht, Northern Germany, and patented in 1867. It rapidl ...

at St. Mary's Roman Catholic Church in Barrie

Barrie is a city in Southern Ontario, Canada, about north of Toronto. The city is within Simcoe County and located along the shores of Kempenfelt Bay, the western arm of Lake Simcoe. Although physically in Simcoe County, Barrie is politicall ...

. The man who placed the dynamite in the church's furnace room was later caught, and admitted that he did so on orders from the Ku Klux Klan. The Ontario media, politicians and other civic authorities, and religious leaders spoke out against such violence and against the Klan. By the winter of 1926, Klan membership in Ontario was declining.

Westward expansion

In 1926, American Ku Klux Klan organizers Hugh Finlay Emmons and Lewis A. Scott fromIndiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

established a Klan organization in Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

. They spent most of early 1927 travelling throughout the province, establishing local Klan branches and selling memberships for per individual. They also spread Klan propaganda and burned crosses, and in July and August 1927 they made another tour of the province.

Soon after, they fled Saskatchewan with the funds they had raised, leaving the Ku Klux Klan floundering. Hawkins and John James Maloney, a seminarian from Hamilton who denounced Romanism

Romanism is a derogatory term for Roman Catholicism used when anti-Catholicism was more common in the United States.

The term was frequently used in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Republican invectives against the Democrats, as pa ...

, moved to Saskatchewan to revive the organization. Under his leadership, the organization raised over in membership fees and claimed to have registered over 70,000 members. Fees were set at $15 per member annually. Many of its members were supporters of the Conservative Party of Saskatchewan frustrated with the success of the Liberal Party as a result of strong support from Catholics.

Under the leadership of Hawkins and Maloney, the Klan became increasingly anti-Catholic and anti-French, and campaigned against the separate school

In Canada, a separate school is a type of school that has constitutional status in three provinces (Ontario, Alberta and Saskatchewan) and statutory status in the three territories (Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut). In these Canadian ...

system with the slogan "one nation, one flag, one language, one school". They opposed "crucifixes on public school walls, nuns teaching in public schools, and the teaching of French in public schools", blaming these issues on Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

. (The Constitution Act, 1867

The ''Constitution Act, 1867'' (french: Loi constitutionnelle de 1867),''The Constitution Act, 1867'', 30 & 31 Victoria (U.K.), c. 3, http://canlii.ca/t/ldsw retrieved on 2019-03-14. originally enacted as the ''British North America Act, 186 ...

guaranteed provincial rights to education and language, protecting minority rights, including those of Catholics and French-speaking citizens.) At a meeting of the Ku Klux Klan on 10 January 1929 at the Regent Hall in Saskatoon

Saskatoon () is the largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Saskatchewan. It straddles a bend in the South Saskatchewan River in the central region of the province. It is located along the Trans-Canada Hig ...

, reverend S.P. Rondeau stated that Quebec was attempting to establish Saskatchewan as a second French-speaking province. Newly founded local chapters would announce their presence to the community with a ritual cross burning.

This became an issue in the 1929 provincial election, ultimately resulting in a coalition government

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

led by James Thomas Milton Anderson

James Thomas Milton Anderson (July 23, 1878 – December 29, 1946) was the fifth premier of Saskatchewan and the first Conservative to hold the office.

Early career

Anderson was chosen as leader of the Conservatives in 1924 and was one of the pa ...

of the Conservatives after the Liberals failed to form a minority government

A minority government, minority cabinet, minority administration, or a minority parliament is a government and cabinet formed in a parliamentary system when a political party or coalition of parties does not have a majority of overall seats in t ...

. The Ku Klux Klan would appear at many election rallies for James Garfield Gardiner

James Garfield Gardiner (30 November 1883 – 12 January 1962) was a Canadian farmer, educator, and politician. He served as the fourth premier of Saskatchewan, and as a minister in the Canadian Cabinet.

Political career

Gardiner was first ele ...

, burning crosses. Gardiner accused Anderson and the Conservatives of being associated with the Ku Klux Klan or seeking its support, but never provided proof. Klan membership included Conservatives, Liberals, and Progressives, and the provincial treasurer ("Klabee") was Walter Davy Cowan

Walter Davy Cowan, D.D.S., (December 31, 1865 – September 28, 1934) was a Canadian politician in Saskatchewan and Ku Klux Klan member. Cowan served as Mayor of Regina and served as Conservative- Unionist Member of Parliament for Regina fr ...

, Conservative Party of Canada

The Conservative Party of Canada (french: Parti conservateur du Canada), colloquially known as the Tories, is a federal political party in Canada. It was formed in 2003 by the merger of the two main right-leaning parties, the Progressive Co ...

Member of Parliament for Long Lake during the 17th Canadian Parliament

The 17th Canadian Parliament was in session from 8 September 1930, until 14 August 1935. The membership was set by the 1930 federal election on 28 July 1930, and it changed only somewhat due to resignations and by-elections until it was disso ...

from 1930 to 1935. Once they formed the government, the Conservatives condemned the Ku Klux Klan, but their opponents persisted in linking them to the organization until the 1934 provincial election. The Conservative government amended the School Act to ban the display of religious insignia in educational settings, and also amended the provincial immigration policy. The government also terminated recognition of teaching certificates granted by Quebec, effectively halting the recruitment of teachers from that province.

Alberta

Maloney married Leorna Miller, the daughter of William Willoughby Miller who was aMember of the Legislative Assembly

A member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) is a representative elected by the voters of a constituency to a legislative assembly. Most often, the term refers to a subnational assembly such as that of a state, province, or territory of a country. S ...

for Biggar during the 7th Saskatchewan Legislature led by Anderson. In his book ''Rome in Canada'' he states that the Anderson government forgot him, and "in their pride and conceit" took credit for much of his effort. Bitter at the rejection, he made visits to Ontario then moved to Alberta in 1930, and spoke at 20 engagements that spring at the request of Orange Lodge Grand Master A.E. Williams. Finding competition against William Aberhart ("Bible Bill") in Calgary

Calgary ( ) is the largest city in the western Canadian province of Alberta and the largest metro area of the three Prairie Provinces. As of 2021, the city proper had a population of 1,306,784 and a metropolitan population of 1,481,806, maki ...

difficult, he moved to Edmonton

Edmonton ( ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Alberta. Edmonton is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Alberta's central region. The city an ...

, which he stated was the "Rome of the West" because of its many Roman Catholic properties.

He restored the Alberta Ku Klux Klan, which had been established in 1923 but was poorly organized and managed. He declared himself the Imperial Wizard, and sent for experienced Klan organizers from British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

and Saskatchewan. Travelling to as many as five engagements a day in rural areas to establish Klaverns and collect membership fees, the Klan sometimes encountered strong opposition, requiring police protection at Gibbons Gibbons may refer to:

* The plural of gibbon, an ape in the family Hylobatidae

* Gibbons (surname)

* Gibbons, Alberta

* Gibbons (automobile), a British light car of the 1920s

* Gibbons P.C., a leading American law firm headquartered in New Jerse ...

and Stony Plain, facing a volley of thrown rocks at Chauvin, and prevented from disembarking a train at Wainwright. The Klan carried out the same activities in Alberta as in the rest or North America, although they were somewhat less overtly violent. For example, there was only one tarring and feathering reported in Lacombe during this era, to which the Klan denied involvement. As their main focus in Alberta was to marginalize Catholic, Jewish, and non-Anglo-Saxon white people, they led boycotts of Catholic businesses, targeted francophones with intimidation tactics, and influenced municipal elections to oust politicians they deemed to be "papist sympathizers."

The Klan celebrated the 1931 election of Edmonton mayor Dan Knott

Daniel Kennedy Knott (July 1, 1879 – November 26, 1959) was a labour activist and politician in Alberta, Canada and a mayor of Edmonton. He had associations with the Canadian branch of the Ku Klux Klan.

Early life

Dan Knott was born in Co ...

by burning a cross. On three separate occasions, Knott granted the Klan permission to hold "picnics" and erect burning crosses on the Edmonton Exhibition grounds, now known as Northlands. The Klan published a newspaper ''The Liberator'' in downtown Edmonton during the early 1930s. Klan meetings were held in the Memorial Hall of the Royal Canadian Legion in Edmonton.

The Ku Klux Klan received its charter in September 1932, but questions about the organization's funds led to disputes about Maloney's leadership. On 25 January 1933, he was convicted of stealing legal documents from the office of a lawyer who had opposed incorporation of the Ku Klux Klan, and on 3 February he was convicted of insurance fraud.

The downfall of Maloney was chiefly responsible for the discontinuation of the Ku Klux Klan in Alberta.

While the Ku Klux Klan did not achieve the same prominence in Alberta as it did in Saskatchewan, there was still at least one local charter whosCertificate of Incorporation

was approved every two years until 2003.

Policy and propaganda

In a letter to the

In a letter to the Manitoba Free Press

The ''Winnipeg Free Press'' (or WFP; founded as the ''Manitoba Free Press'') is a daily (excluding Sunday) broadsheet newspaper in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. It provides coverage of local, provincial, national, and international news, as well ...

on 8 May 1928, J. W. E. Rosborough, the Imperial Wizard for Saskatchewan, stated that the creed of the Saskatchewan Ku Klux Klan was a belief in Protestantism, separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular s ...

, one public school system, just laws and liberty, law and order, freedom from mob violence, freedom of speech

Speech is a human vocal communication using language. Each language uses phonetic combinations of vowel and consonant sounds that form the sound of its words (that is, all English words sound different from all French words, even if they are th ...

and press, higher moral standards, gentile economic freedom

Economic freedom, or economic liberty, is the ability of people of a society to take economic actions. This is a term used in economic and policy debates as well as in the philosophy of economics. One approach to economic freedom comes from the l ...

, racial purity, restrictive and selective immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, ...

, and pure patriotism. T.J. Hind, the reverend

The Reverend is an honorific style most often placed before the names of Christian clergy and ministers. There are sometimes differences in the way the style is used in different countries and church traditions. ''The Reverend'' is correctly ...

of First Baptist Church in Moose Jaw, stated that one of the purposes of the establishment of the Ku Klux Klan was for the protection of the physical purity of current and future generations.

Klansmen believed that Canada's immigration policy made it the dumping ground of the world. They falsely stated that of Regina's 8,000 recent immigrants, only 7 were Protestants. They promoted a "100 percent Canadian" policy to deter the declining influence of Protestant Anglo-Saxon Canadians as a result of increasing immigration from Europe, particularly Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

, which was primarily Roman Catholic and Jewish.

In October 1927 at a Ku Klux Klan meeting held at Regina City Hall, Maloney said he had received a letter from

In October 1927 at a Ku Klux Klan meeting held at Regina City Hall, Maloney said he had received a letter from Plutarco Elías Calles

Plutarco Elías Calles (25 September 1877 – 19 October 1945) was a general in the Mexican Revolution and a Sonoran politician, serving as President of Mexico from 1924 to 1928.

The 1924 Calles presidential campaign was the first populist ...

, the President of Mexico

The president of Mexico ( es, link=no, Presidente de México), officially the president of the United Mexican States ( es, link=no, Presidente de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos), is the head of state and head of government of Mexico. Under the ...

, in which Calles stated that Mexico had an illiteracy

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in Writing, written form in some specific context of use. In other wo ...

rate of 80% as a result of the Roman Catholic Church's control of the educational system over the previous 400 years. (Calles was staunchly anti-clerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

, and during his presidency hostility to Catholics and the enactment of the Calles Law resulted in the Cristero War.) Maloney described the Roman Catholic Church as "that dark system which has wrecked every country it got hold of", and campaigned to radically change Canada's immigration laws to restrict entry to Catholics. Klan organizers stated that the organization was pro-Protestant and did not discriminate based on political or religious affiliation, but was established to save Canada.

Klansmen stated that the organization did not receive fair treatment from the media, and that they were willing to establish their own news presses to disseminate facts about the organization.

Membership

In July 1927, a Klan organizer claimed that there were 46,500 members in Saskatchewan. By late 1927, there were 2,300 members of the Ku Klux Klan in Moose Jaw.

In July 1927, a Klan organizer claimed that there were 46,500 members in Saskatchewan. By late 1927, there were 2,300 members of the Ku Klux Klan in Moose Jaw.

See also

*Fascism in Canada

Fascism in Canada (french: Fascisme au Canada) consists of a variety of movements and political parties in Canada during the 20th century. Largely a fringe ideology, fascism has never commanded a large following amongst the Canadian people, and ...

* Fascism in North America

*Ku Klux Klan titles and vocabulary

Ku Klux Klan (KKK) nomenclature has evolved over the order's nearly 160 years of existence. The titles and designations were first laid out in the original Klan's prescripts of 1867 and 1868, then revamped with William J. Simmons's ''Kloran'' of 1 ...

*James Alexander McQuirter James Alexander McQuirter (born and also known as James Tavian Alexander) is a former Grand Wizard of the Canadian Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. In 1981, he was charged, along with Wolfgang Droege and other white supremacists, with plotting to overt ...

* List of fascist movements

* List of Ku Klux Klan organizations

* List of neo-Nazi organizations

* List of organizations designated by the Southern Poverty Law Center as hate groups

* List of white nationalist organizations

*Operation Red Dog

Operation Red Dog was the code name of an April 27, 1981 military filibustering plot by Canadian and American citizens, largely affiliated with white supremacist and Ku Klux Klan groups, to overthrow the government of Dominica, where they plann ...

*Racism in North America

This article describes the state of race relations and racism in North America. Racism manifests itself in different ways and severities throughout North America depending on the country. Colonial processes shaped the continent culturally, demogra ...

* Racism in the United States

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * {{Authority control 1925 establishments in Canada Anti-black racism in Canada Anti-Quebec sentiment Antisemitism in Canada Anti-Slavic sentiment Canadian far-right political movements Francophobia in North America Canada White supremacy in Canada Anti-communist organizations