Krupp family on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Krupp family (see

The Krupp family (see

In the 20th century the company was headed by

In the 20th century the company was headed by

In 1807 the progenitor of the modern Krupp firm, Friedrich Krupp, began his commercial career at age 19 when the Widow Krupp appointed him manager of the forge. Friedrich's father, the widow's son, had died 11 years previously; since that time, the widow had tutored the boy in the ways of commerce, as he seemed the logical family heir. Unfortunately, Friedrich proved too ambitious for his own good, and quickly ran the formerly profitable forge into the ground. The widow soon had to sell it away.

In 1810, the widow died, and in what would prove a disastrous move, left virtually all the Krupp fortune and property to Friedrich. Newly enriched, Friedrich decided to discover the secret of cast (crucible) steel. Benjamin Huntsman, a clockmaker from

In 1807 the progenitor of the modern Krupp firm, Friedrich Krupp, began his commercial career at age 19 when the Widow Krupp appointed him manager of the forge. Friedrich's father, the widow's son, had died 11 years previously; since that time, the widow had tutored the boy in the ways of commerce, as he seemed the logical family heir. Unfortunately, Friedrich proved too ambitious for his own good, and quickly ran the formerly profitable forge into the ground. The widow soon had to sell it away.

In 1810, the widow died, and in what would prove a disastrous move, left virtually all the Krupp fortune and property to Friedrich. Newly enriched, Friedrich decided to discover the secret of cast (crucible) steel. Benjamin Huntsman, a clockmaker from

After Krupp's death in 1887, his only son, Friedrich Alfred, carried on the work. The father had been a hard man, known as "Herr Krupp" since his early teens. Friedrich Alfred was called "Fritz" all his life, and was strikingly dissimilar to his father in appearance and personality. He was a philanthropist, a rarity amongst Ruhr industrial leaders. Part of his philanthropy supported the study of

After Krupp's death in 1887, his only son, Friedrich Alfred, carried on the work. The father had been a hard man, known as "Herr Krupp" since his early teens. Friedrich Alfred was called "Fritz" all his life, and was strikingly dissimilar to his father in appearance and personality. He was a philanthropist, a rarity amongst Ruhr industrial leaders. Part of his philanthropy supported the study of

Upon Fritz's death, his teenage daughter Bertha inherited the firm. In 1903, the firm formally incorporated as a

Upon Fritz's death, his teenage daughter Bertha inherited the firm. In 1903, the firm formally incorporated as a  Gustav led the firm through

Gustav led the firm through  In 1920, the Ruhr Uprising occurred in reaction to the

In 1920, the Ruhr Uprising occurred in reaction to the

As the eldest son of

As the eldest son of  After the war, the Ruhr became part of the British Zone of occupation. The British dismantled Krupp's factories, sending machinery all over Europe as

After the war, the Ruhr became part of the British Zone of occupation. The British dismantled Krupp's factories, sending machinery all over Europe as

Meanwhile, Alfried was held in Landsberg prison, where Hitler had been imprisoned in 1924. At the Krupp Trial, held in 1947–1948 in Nuremberg following the main

Meanwhile, Alfried was held in Landsberg prison, where Hitler had been imprisoned in 1924. At the Krupp Trial, held in 1947–1948 in Nuremberg following the main  Despite having only 16,000 employees and 16,000 pensioners, Alfried refused to cut pensions. He ended unprofitable businesses including shipbuilding, railway tyres, and farm equipment. He hired

Despite having only 16,000 employees and 16,000 pensioners, Alfried refused to cut pensions. He ended unprofitable businesses including shipbuilding, railway tyres, and farm equipment. He hired

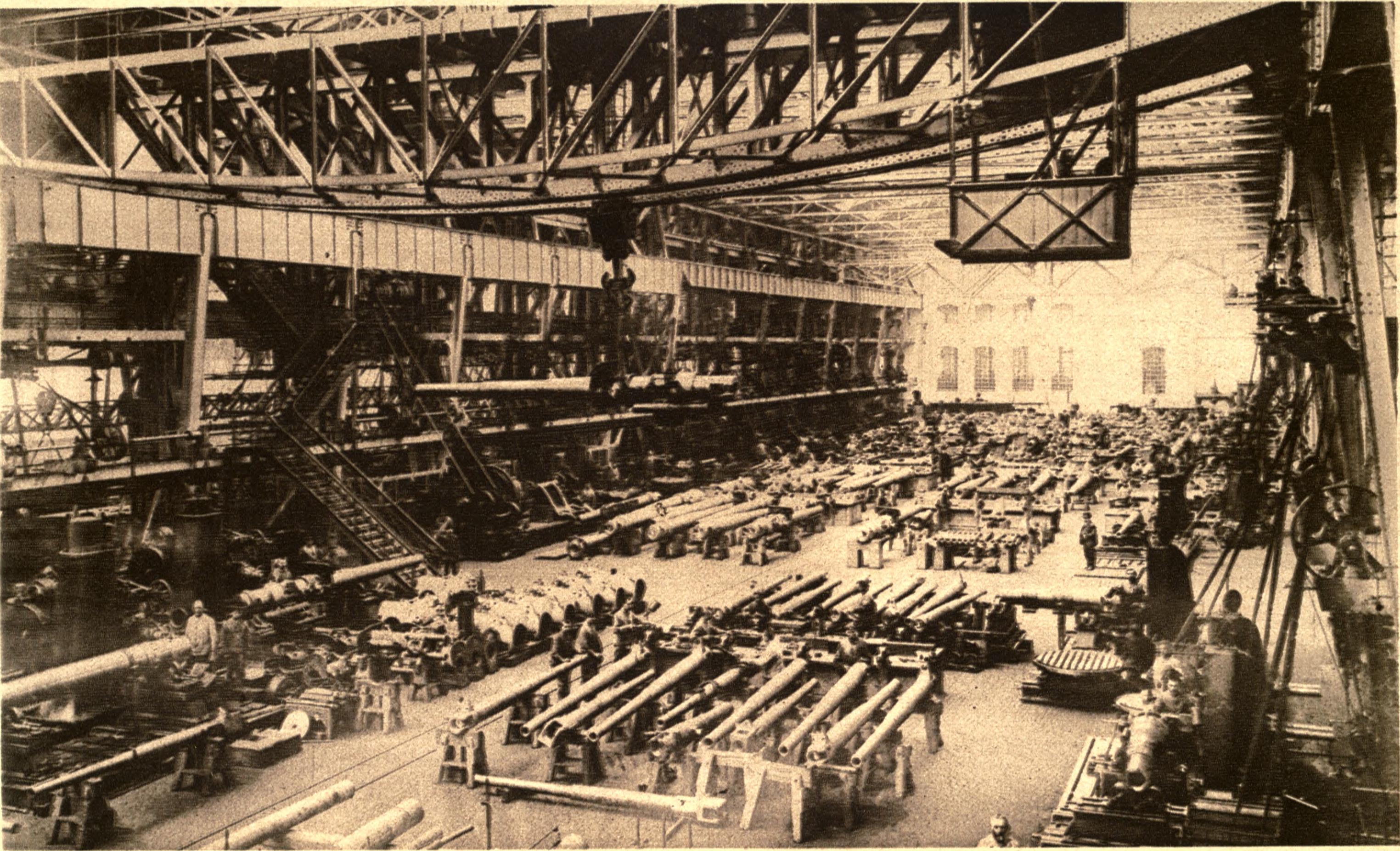

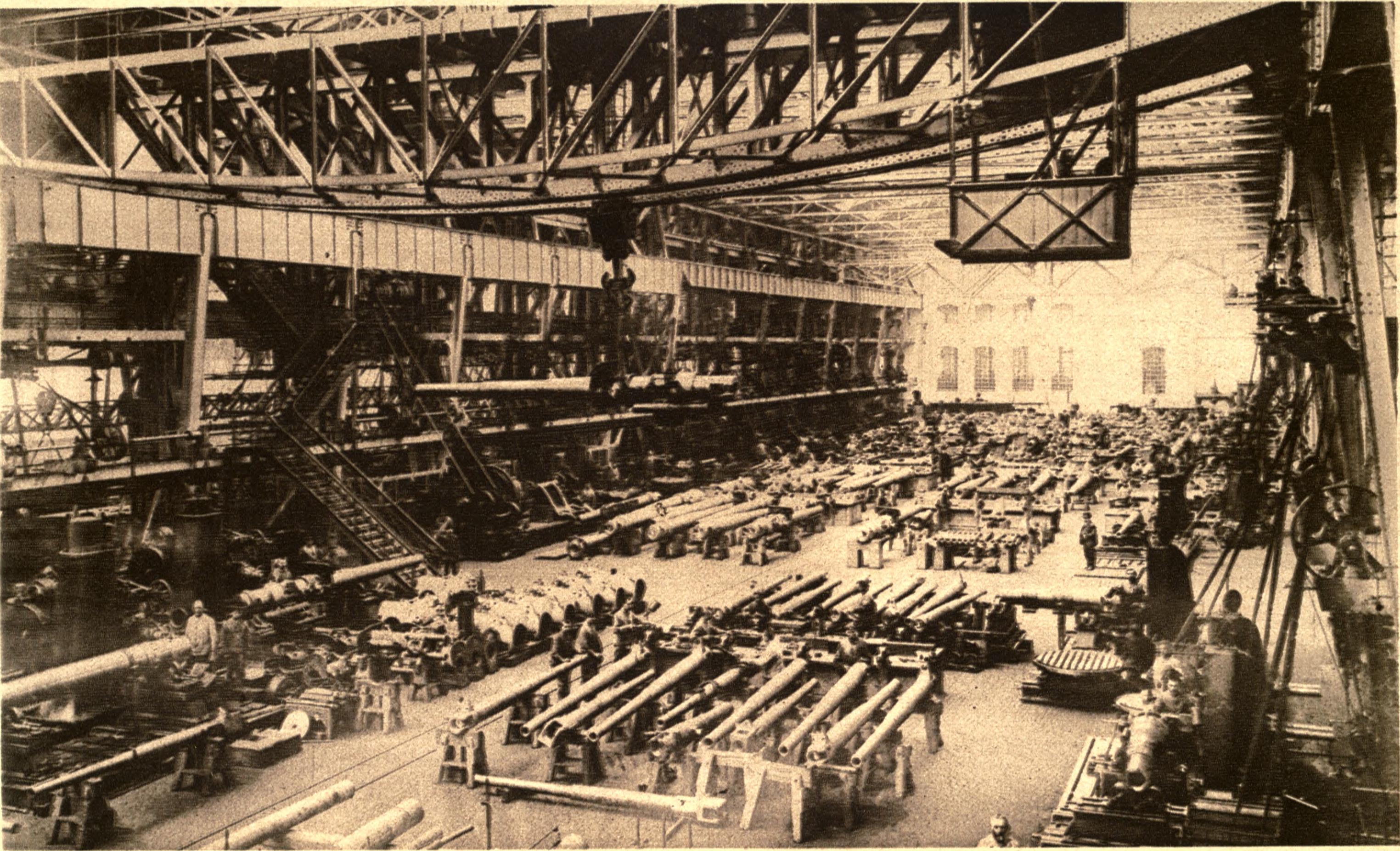

Krupp produced most of the artillery of the Imperial German Army, including its heavy siege guns: the 1914 420 mm Big Bertha, the 1916 Langer Max, and the seven

Krupp produced most of the artillery of the Imperial German Army, including its heavy siege guns: the 1914 420 mm Big Bertha, the 1916 Langer Max, and the seven

42(1) ''The Business History Review'' 24–49

* {{Authority control Companies based in Essen Defence companies of Germany Firearm manufacturers of Germany Companies involved in the Holocaust Auschwitz concentration camp 1881 establishments in Germany

The Krupp family (see

The Krupp family (see pronunciation

Pronunciation is the way in which a word or a language is spoken. This may refer to generally agreed-upon sequences of sounds used in speaking a given word or language in a specific dialect ("correct pronunciation") or simply the way a particular ...

), a prominent 400-year-old German dynasty

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family,''Oxford English Dictionary'', "dynasty, ''n''." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1897. usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A ...

from Essen

Essen (; Latin: ''Assindia'') is the central and, after Dortmund, second-largest city of the Ruhr, the largest urban area in Germany. Its population of makes it the fourth-largest city of North Rhine-Westphalia after Cologne, Düsseldorf and Do ...

, is notable for its production of steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistan ...

, artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

, ammunition

Ammunition (informally ammo) is the material fired, scattered, dropped, or detonated from any weapon or weapon system. Ammunition is both expendable weapons (e.g., bombs, missiles, grenades, land mines) and the component parts of other we ...

and other armaments

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

. The family business

A family business is a commercial organization in which decision-making is influenced by multiple generations of a family, related by blood or marriage or adoption, who has both the ability to influence the vision of the business and the willingn ...

, known as Friedrich Krupp AG (Friedrich Krupp AG Hoesch-Krupp after acquiring Hoesch AG

Hoesch AG was an important steel and mining company with locations in the Ruhr area and Siegen.

In 1871, Hoesch was founded by Leopold Hoesch. In 1938, Hoesch employed 30,000 people.

In 1972, the prominent steel producer merged with the Dutch ...

in 1991 and lasting until 1999), was the largest company in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century, and was the premier weapons manufacturer for Germany in both world war

A world war is an international conflict which involves all or most of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World WarI (1914 ...

s. Starting from the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

until the end of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, it produced battleship

A battleship is a large armour, armored warship with a main artillery battery, battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1 ...

s, U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

s, tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful ...

s, howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

s, guns, utilities, and hundreds of other commodities.

The dynasty began in 1587 when trader Arndt Krupp moved to Essen and joined the merchants' guild. He bought and sold real estate, and became one of the city's richest men. His descendants produced small guns during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

and eventually acquired fulling

Fulling, also known as felting, tucking or walking ( Scots: ''waukin'', hence often spelled waulking in Scottish English), is a step in woollen clothmaking which involves the cleansing of woven or knitted cloth (particularly wool) to eli ...

mills, coal mine

Coal mining is the process of extracting coal from the ground. Coal is valued for its energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use coal as a fuel for extraction of iron from ...

s and an iron forge. During the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

, Friedrich Krupp founded the Gusstahlfabrik (Cast Steel Works) and started smelted steel production in 1816. This led to the company becoming a major industrial power and laid the foundation for the steel empire that would come to dominate the world for nearly a century under his son Alfred

Alfred may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*'' Alfred J. Kwak'', Dutch-German-Japanese anime television series

* ''Alfred'' (Arne opera), a 1740 masque by Thomas Arne

* ''Alfred'' (Dvořák), an 1870 opera by Antonín Dvořák

*"Alfred (Interl ...

. Krupp became the arms manufacturer for the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

in 1859, and later the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

.

The company produced steel used to build railroads in the United States and to cap the Chrysler Building

The Chrysler Building is an Art Deco skyscraper on the East Side of Manhattan in New York City, at the intersection of 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue in Midtown Manhattan. At , it is the tallest brick building in the world with a steel fra ...

. During the time of the Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, the Krupp company supported the Nazi regime and used slave labour, which was used by the Nazi Party to help carry out the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

, with Krupp reaping the economic benefit. Krupp used almost 100,000 slave labourers, housed in poor conditions and many worked to death. The company had a workshop near the Auschwitz concentration camp

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. I ...

. Alfried Krupp was convicted as a criminal against humanity for the employment of the prisoners of war, foreign civilians and concentration camp inmates under inhumane conditions in work connected with the conduct of war. He was sentenced to twelve years imprisonment, but served just three and was pardoned (but not acquitted) by John J. McCloy

John Jay McCloy (March 31, 1895 – March 11, 1989) was an American lawyer, diplomat, banker, and a presidential advisor. He served as Assistant Secretary of War during World War II under Henry Stimson, helping deal with issues such as German sa ...

.

Part of this pardoning meant that all of Krupp's holdings were restored. Again, the company rose to become one of the wealthiest companies in Europe. However, this growth did not last indefinitely. In 1967, an economic recession resulted in significant financial loss for the company. In 1999, it merged with Thyssen AG to form the industrial conglomerate

Conglomerate or conglomeration may refer to:

* Conglomerate (company)

* Conglomerate (geology)

* Conglomerate (mathematics)

In popular culture:

* The Conglomerate (American group), a production crew and musical group founded by Busta Rhymes

** ...

ThyssenKrupp AG

ThyssenKrupp AG (, ; stylized as thyssenkrupp) is a German industrial engineering and steel production multinational conglomerate. It is the result of the 1999 merger of Thyssen AG and Krupp and has its operational headquarters in Duisburg and ...

.

Controversy has not eluded the Krupp company. Being a major weapons supplier to multiple sides throughout various conflicts, the Krupps were sometimes blamed for the wars themselves or the degree of carnage that ensued.

Overview

Friedrich Krupp (1787–1826) launched the family's metal-based activities, building a pioneeringsteel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistan ...

foundry

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

in Essen in 1810. After his death, his sons Alfred

Alfred may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*'' Alfred J. Kwak'', Dutch-German-Japanese anime television series

* ''Alfred'' (Arne opera), a 1740 masque by Thomas Arne

* ''Alfred'' (Dvořák), an 1870 opera by Antonín Dvořák

*"Alfred (Interl ...

and an unidentified brother operated the business in partnership with their mother. An account cited that, on his deathbed, the elder Krupp confided to Alfred, who was then 14 years old, the secret of steel casting. In 1848, Alfred became the sole owner of the foundry. This next generation Krupp (1812–87), known as "the Cannon King" or as "Alfred the Great", invested heavily in new technology to become a significant manufacturer of steel rollers (used to make eating utensils) and railway tyres. He also invested in fluidized hotbed technologies (notably the Bessemer process

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass production of steel from molten pig iron before the development of the open hearth furnace. The key principle is removal of impurities from the iron by oxidation ...

) and acquired many mines in Germany and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. Initially, Krupp failed to gain profit from the Bessemer process due to the high phosphorus content of German iron ores. His chemists, however, later learned of the problem and constructed a Bessemer plant called C&T Steel. Unusual for the era, he provided social services for his workers, including subsidized housing and health and retirement benefits.

The company began to make steel cannons in the 1840s—especially for the Russian, Turkish, and Prussian armies. Low non-military demand and government subsidies meant that the company specialized more and more in weapons: by the late 1880s the manufacture of armaments represented around 50% of Krupp's total output. When Alfred started with the firm, it had five employees. At his death twenty thousand people worked for Krupp—making it the world's largest industrial company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared ...

and the largest private company in the German empire.

Krupp's had a Great Krupp Building with an exhibition of guns at the Columbian Exposition in 1893.

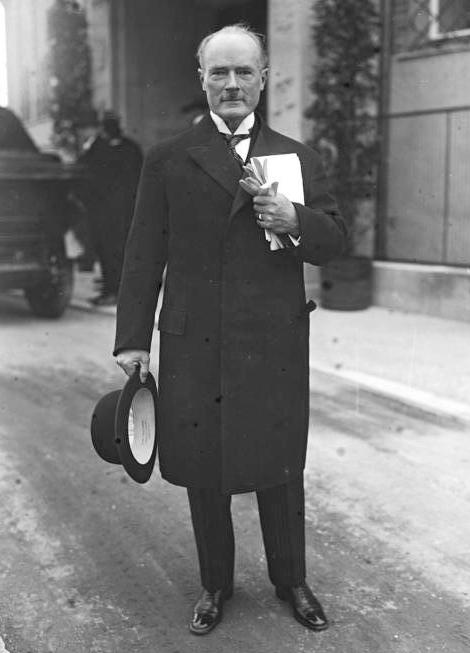

Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach

Gustav Georg Friedrich Maria Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach (born Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach; 7 August 1870 – 16 January 1950) was a German foreign service official who became chairman of the board of Friedrich Krupp AG, a heavy industry con ...

(1870–1950), who assumed the surname of Krupp when he married the Krupp heiress, Bertha Krupp

Bertha Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach (29 March 1886 – 21 September 1957) was a member of the Krupp family, Germany's leading industrial dynasty of the 19th and 20th centuries. As the elder child and heir of Friedrich Alfred Krupp she was the ...

. After Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

came to power in Germany in 1933, the Krupp works became the center for German rearmament. In 1943, by a special order from Hitler, the company reverted to a sole-proprietorship, with Gustav and Bertha's eldest son Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach (1907–67) as proprietor.

After Germany's defeat, Gustav was senile and incapable of standing trial, and the Nuremberg Military Tribunal

The subsequent Nuremberg trials were a series of 12 military tribunals for war crimes against members of the leadership of Nazi Germany between December 1946 and April 1949. They followed the first and best-known Nuremberg trial before the Int ...

convicted Alfried as a war criminal in the Krupp Trial for "plunder" and for his company's use of slave labor

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. It sentenced him to 12 years in prison and ordered him to sell 75% of his holdings. In 1951, as the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

developed and no buyer came forward, the U.S. occupation authorities released him, and in 1953 he resumed control of the firm.

In 1968, the company became an Aktiengesellschaft

(; abbreviated AG, ) is a German word for a corporation limited by share ownership (i.e. one which is owned by its shareholders) whose shares may be traded on a stock market. The term is used in Germany, Austria, Switzerland (where it is equ ...

and ownership was transferred to the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation

__NOTOC__

The Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation (german: Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Stiftung) is a major German philanthropic foundation, created by and named in honor of Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, former owner ...

. In 1999, the Krupp Group merged with its largest competitor, Thyssen AG; the combined company—ThyssenKrupp

ThyssenKrupp AG (, ; stylized as thyssenkrupp) is a German industrial engineering and steel production multinational conglomerate. It is the result of the 1999 merger of Thyssen AG and Krupp and has its operational headquarters in Duisburg a ...

, became Germany's fifth-largest firm and one of the largest steel producers in the world.

History of the family

Early history

The Krupp family first appeared in the historical record in 1587, when Arndt Krupp joined the merchants'guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometim ...

in Essen. Arndt, a trader, arrived in town just before an outbreak of the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

and became one of the city's wealthiest men by purchasing the property of families who fled the epidemic. After he died in 1624, his son Anton took over the family business; Anton oversaw a gunsmith

A gunsmith is a person who repairs, modifies, designs, or builds guns. The occupation differs from an armorer, who usually replaces only worn parts in standard firearms. Gunsmiths do modifications and changes to a firearm that may require a very ...

ing operation during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

(1618–48), which was the first instance of the family's long association with arms manufacturing.

For the next century the Krupps continued to acquire property and became involved in municipal politics in Essen. By the mid-18th-century, Friedrich Jodocus Krupp, Arndt's great-great-grandson, headed the Krupp family. In 1751, he married Helene Amalie Ascherfeld (another of Arndt's great-great-grandchildren); Jodocus died six years later, which left his widow to run the business: a family first. The Widow Krupp greatly expanded the family's holdings over the decades, acquiring a fulling

Fulling, also known as felting, tucking or walking ( Scots: ''waukin'', hence often spelled waulking in Scottish English), is a step in woollen clothmaking which involves the cleansing of woven or knitted cloth (particularly wool) to eli ...

mill, shares in four coal mine

Coal mining is the process of extracting coal from the ground. Coal is valued for its energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use coal as a fuel for extraction of iron from ...

s, and (in 1800) an iron forge located on a stream near Essen.

Friedrich's era

In 1807 the progenitor of the modern Krupp firm, Friedrich Krupp, began his commercial career at age 19 when the Widow Krupp appointed him manager of the forge. Friedrich's father, the widow's son, had died 11 years previously; since that time, the widow had tutored the boy in the ways of commerce, as he seemed the logical family heir. Unfortunately, Friedrich proved too ambitious for his own good, and quickly ran the formerly profitable forge into the ground. The widow soon had to sell it away.

In 1810, the widow died, and in what would prove a disastrous move, left virtually all the Krupp fortune and property to Friedrich. Newly enriched, Friedrich decided to discover the secret of cast (crucible) steel. Benjamin Huntsman, a clockmaker from

In 1807 the progenitor of the modern Krupp firm, Friedrich Krupp, began his commercial career at age 19 when the Widow Krupp appointed him manager of the forge. Friedrich's father, the widow's son, had died 11 years previously; since that time, the widow had tutored the boy in the ways of commerce, as he seemed the logical family heir. Unfortunately, Friedrich proved too ambitious for his own good, and quickly ran the formerly profitable forge into the ground. The widow soon had to sell it away.

In 1810, the widow died, and in what would prove a disastrous move, left virtually all the Krupp fortune and property to Friedrich. Newly enriched, Friedrich decided to discover the secret of cast (crucible) steel. Benjamin Huntsman, a clockmaker from Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire ...

, had pioneered a process to make crucible steel

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron (cast iron), iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. In ancient times steel and iron were impossible to melt using charcoal or coal fires ...

in 1740, but the British had managed to keep it secret, forcing others to import steel. When Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

began his blockade of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

(see Continental System

The Continental Blockade (), or Continental System, was a large-scale embargo against British trade by Napoleon Bonaparte against the British Empire from 21 November 1806 until 11 April 1814, during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon issued the Berli ...

), British steel became unavailable, and Napoleon offered a prize of four thousand francs to anyone who could replicate the British process. This prize piqued Friedrich's interest.

Thus, in 1811 Friedrich founded the Krupp Gusstahlfabrik (Cast Steel Works). He realized he would need a large facility with a power source for success, and so he built a mill

Mill may refer to:

Science and technology

*

* Mill (grinding)

* Milling (machining)

* Millwork

* Textile mill

* Steel mill, a factory for the manufacture of steel

* List of types of mill

* Mill, the arithmetic unit of the Analytical Engine early ...

and foundry

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

on the Ruhr River

__NOTOC__

The Ruhr is a river in western Germany ( North Rhine-Westphalia), a right tributary (east-side) of the Rhine.

Description and history

The source of the Ruhr is near the town of Winterberg in the mountainous Sauerland region, at ...

, which unfortunately proved an unreliable stream. Friedrich spent a significant amount of time and money in the small, waterwheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with a number of blades or bucke ...

-powered facility, neglecting other Krupp business, but in 1816 he was able to produce smelted steel. He died in Essen, 8 October 1826 age 39.

Alfred's era

Alfred Krupp (born Alfried Felix Alwyn Krupp), son of Friedrich Carl, was born in Essen in 1812. His father's death forced him to leave school at the age of fourteen and take on responsibility for the steel works in companionship with his motherTherese Krupp

Therese Krupp (1790–1850) was a German industrialist.Antonius Lux (Hrsg.): Große Frauen der Weltgeschichte. Tausend Biographien in Wort und Bild. Sebastian Lux Verlag, München 1963 She was married to Friedrich Krupp and took over the Krupp c ...

. Prospects were daunting: his father had spent a considerable fortune in the attempt to cast steel in large ingots, and to keep the works going the widow and family lived in extreme frugality. The young director laboured alongside the workmen by day and carried on his father's experiments at night, while occasionally touring Europe trying to promote Krupp products and make sales. It was during a stay in England that young Alfried became enamored of the country and adopted the English spelling of his name.

For years, the works made barely enough money to cover the workmen's wages. Then, in 1841, Alfred's brother Hermann invented the spoon-roller—which Alfred patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A ...

ed, bringing in enough money to enlarge the factory, steel production, and cast steel blocks. In 1847 Krupp made his first cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

of cast steel. At the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition which took pl ...

(London) of 1851, he exhibited a 6 pounder made entirely from cast steel, and a solid flawless ingot

An ingot is a piece of relatively pure material, usually metal, that is cast into a shape suitable for further processing. In steelmaking, it is the first step among semi-finished casting products. Ingots usually require a second procedure of sha ...

of steel weighing , more than twice as much as any previously cast. He surpassed this with a ingot for the Paris Exposition in 1855. Krupp's exhibits caused a sensation in the engineering world, and the Essen works became famous.

In 1851, another successful innovation, no-weld railway tyres, began the company's primary revenue stream, from sales to railways in the United States. Alfred enlarged the factory and fulfilled his long-cherished scheme to construct a breech-loading cannon of cast steel. He strongly believed in the superiority of breech-loader

A breechloader is a firearm in which the user loads the ammunition ( cartridge or shell) via the rear (breech) end of its barrel, as opposed to a muzzleloader, which loads ammunition via the front ( muzzle).

Modern firearms are generally breec ...

s, on account of improved accuracy and speed, but this view did not win general acceptance among military officers, who remained loyal to tried-and-true muzzle-loaded bronze cannon. Alfred soon began producing breech loading howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

s, one of which he gifted to the Prussian court.

Indeed, unable to sell his steel cannon, Krupp gave it to the King of Prussia, who used it as a decorative piece. The king's brother Wilhelm

Wilhelm may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* William Charles John Pitcher, costume designer known professionally as "Wilhelm"

* Wilhelm (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

Other uses

* Mount ...

, however, realized the significance of the innovation. After he became regent in 1859, Prussia bought its first 312 steel cannon from Krupp, which became the main arms manufacturer for the Prussian military.

Prussia used the advanced technology of Krupp to defeat both Austria and France in the German Wars of Unification. The French high command refused to purchase Krupp guns despite Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A neph ...

's support. The Franco-Prussian war was in part a contest of "Kruppstahl" versus bronze cannon. The success of German artillery spurred the first international arms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more states to have superior armed forces; a competition concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and ...

, against Schneider-Creusot in France and Armstrong Armstrong may refer to:

Places

* Armstrong Creek (disambiguation), various places

Antarctica

* Armstrong Reef, Biscoe Islands

Argentina

* Armstrong, Santa Fe

Australia

* Armstrong, Victoria

Canada

* Armstrong, British Columbia

* Armstrong, ...

in England. Krupp was able to sell, alternately, improved artillery and improved steel shielding to countries from Russia to Chile to Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

(formerly known as Siam).

In the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

, Alfred continued to expand, including the purchase of Spanish mines and Dutch shipping, making Krupp the biggest and richest company in Europe but nearly bankrupting it. He was bailed out with a 30 million Mark loan from a consortium of banks arranged by the Prussian State Bank.

In 1878 and 1879 Krupp held competitions known as ''Völkerschiessen'', which were firing demonstrations of cannon for international buyers. These were held in Meppen, at the largest proving ground in the world; privately owned by Krupp. He took on 46 nations as customers. At the time of his death in 1887, he had 75,000 employees, including 20,200 in Essen. In his lifetime, Krupp manufactured a total of 24,576 guns; 10,666 for the German government and 13,910 for export.

Krupp established the ''Generalregulativ'' as the firm's basic constitution. The company was a sole proprietorship

A sole proprietorship, also known as a sole tradership, individual entrepreneurship or proprietorship, is a type of enterprise owned and run by one person and in which there is no legal distinction between the owner and the business entity. A sol ...

, inherited by primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

, with strict control of workers. Krupp demanded a loyalty oath, required workers to obtain written permission from their foremen when they needed to use the toilet and issued proclamations telling his workers not to concern themselves with national politics. In return, Krupp provided social services that were unusually liberal for the era, including "colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

" with parks, schools and recreation grounds - while the widows' and orphans' and other benefit schemes insured the men and their families in case of illness or death. Essen became a large company town

A company town is a place where practically all stores and housing are owned by the one company that is also the main employer. Company towns are often planned with a suite of amenities such as stores, houses of worship, schools, markets and re ...

and Krupp became a de facto state within a state, with "Kruppianer" as loyal to the company and the Krupp family as to the nation and the Hohenzollern family. Krupp's paternalist

Paternalism is action that limits a person's or group's liberty or autonomy and is intended to promote their own good. Paternalism can also imply that the behavior is against or regardless of the will of a person, or also that the behavior expres ...

strategy was adopted by Bismarck as government policy, as a preventive against Social Democratic

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

tendencies, and later influenced the development and adoption of ''Führerprinzip

The (; German for 'leader principle') prescribed the fundamental basis of political authority in the Government of Nazi Germany. This principle can be most succinctly understood to mean that "the Führer's word is above all written law" and th ...

'' by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

.

The Krupp social services programme began about 1861, when it was found that there were not sufficient houses in the town for firm employees, and the firm began building dwellings. By 1862 ten houses were ready for foremen, and in 1863 the first houses for workingmen were built in Alt Westend. Neu Westend was built in 1871 and 1872. By 1905, 400 houses were provided, many being given rent free to widows of former workers. A cooperative society

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-control ...

was founded in 1868 which became the Consum-Anstalt. Profits were divided according to amounts purchased. A boarding house for single men, the Ménage, was started in 1865 with 200 boarders and by 1905 accommodated 1000. Bath houses were provided and employees received free medical services. Accident, life, and sickness insurance societies were formed, and the firm contributed to their support. Technical and manual training schools were provided.

Krupp was also held in high esteem by the kaiser, who dismissed Julius von Verdy du Vernois

Adrian Friedrich Wilhelm Julius Ludwig von Verdy du Vernois (19 July 1832 – 30 September 1910), often given the short name of Verdy, was a German general and staff officer, chiefly noted both for his military writings and his service o ...

and his successor Hans von Kaltenborn for rejecting Krupp's design of the C-96 field gun, quipping, "I've canned three War Ministers because of Krupp, and still they don't catch on!"

Krupp proclaimed he wished to have "a man come and start a counter-revolution

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revoluti ...

" against Jews, socialists and liberals. In some of his odder moods, he considered taking the role himself. According to historian William Manchester

William Raymond Manchester (April 1, 1922 – June 1, 2004) was an American author, biographer, and historian. He was the author of 18 books which have been translated into over 20 languages. He was awarded the National Humanities Medal and the ...

, Alfried Krupp, his great grandson, would interpret these outbursts as a prophecy fulfilled by the coming of Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

.

Krupp's marriage was not a happy one. His wife Bertha (not to be confused with their granddaughter), was unwilling to remain in polluted Essen in Villa Hügel

The Villa Hügel is a 19th-century mansion in Bredeney, now part of Essen, Germany. It was built by the industrialist Alfred Krupp in 1870-1873 as his main residence and was the home of the Krupp family until after World War II. More recently, ...

, the mansion which Krupp designed. She spent most of their married years in resorts and spas, with their only child, a son.

Friedrich Alfred's era

After Krupp's death in 1887, his only son, Friedrich Alfred, carried on the work. The father had been a hard man, known as "Herr Krupp" since his early teens. Friedrich Alfred was called "Fritz" all his life, and was strikingly dissimilar to his father in appearance and personality. He was a philanthropist, a rarity amongst Ruhr industrial leaders. Part of his philanthropy supported the study of

After Krupp's death in 1887, his only son, Friedrich Alfred, carried on the work. The father had been a hard man, known as "Herr Krupp" since his early teens. Friedrich Alfred was called "Fritz" all his life, and was strikingly dissimilar to his father in appearance and personality. He was a philanthropist, a rarity amongst Ruhr industrial leaders. Part of his philanthropy supported the study of eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

. He was particularly interested in promoting the application of genetics to social science and public policy.

Fritz was a skilled businessman, though of a different sort from his father. Fritz was a master of the subtle sell, and cultivated a close rapport with the Kaiser, Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

. Under Fritz's management, the firm's business blossomed further and further afield, spreading across the globe. He focused on arms manufacturing, as the US railroad market purchased from its own growing steel industry.

Fritz Krupp authorized many new products that would do much to change history. In 1890 Krupp developed nickel steel, which was hard enough to allow thin battleship armor and cannon using Nobel's improved gunpowder. In 1892, Krupp bought Gruson in a hostile takeover

In business, a takeover is the purchase of one company (the ''target'') by another (the ''acquirer'' or ''bidder''). In the UK, the term refers to the acquisition of a public company whose shares are listed on a stock exchange, in contrast to ...

. It became Krupp-Panzer and manufactured armor plate and ships' turrets. In 1893 Rudolf Diesel brought his new engine to Krupp to construct. In 1896 Krupp bought Germaniawerft in Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the Jutland ...

, which became Germany's main warship builder and built the first German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

in 1906.

Fritz married Magda and they had two daughters: Bertha (1886–1957) and Barbara (1887–1972); the latter married Tilo Freiherr von Wilmowsky (1878–1966) in 1907.

Fritz was arrested on 15 October 1902 by Italian police at his retreat on the Mediterranean island of Capri

Capri ( , ; ; ) is an island located in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the Sorrento Peninsula, on the south side of the Gulf of Naples in the Campania region of Italy. The main town of Capri that is located on the island shares the name. It has be ...

, where he enjoyed the companionship of forty or so adolescent Italian boys. He had a subsequent publicity disaster and was found dead in his chambers not long after. It was alleged suicide, but foul play was suspected and details of the event were vague. His wife was institutionalized for insanity.

Gustav's era

Upon Fritz's death, his teenage daughter Bertha inherited the firm. In 1903, the firm formally incorporated as a

Upon Fritz's death, his teenage daughter Bertha inherited the firm. In 1903, the firm formally incorporated as a joint-stock company

A joint-stock company is a business entity in which shares of the company's stock can be bought and sold by shareholders. Each shareholder owns company stock in proportion, evidenced by their shares (certificates of ownership). Shareholders a ...

, Fried. Krupp Grusonwerk AG. However, Bertha owned all but four shares. Kaiser Wilhelm II felt it was unthinkable for the Krupp firm to be run by a woman. He arranged for Bertha to marry Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach, a Prussian courtier to the Vatican and grandson of American Civil War General Henry Bohlen

Henry Bohlen (October 22, 1810 – August 22, 1862) was a German-American Union Army, Union Brigadier general (United States), Brigadier General of the American Civil War. Before becoming the first foreign-born Union general in the Civil War, he f ...

. By imperial proclamation at the wedding, Gustav was given the additional surname "Krupp," which was to be inherited by primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

along with the company.

In 1911, Gustav bought Hamm Wireworks to manufacture barbed wire. In 1912, Krupp began manufacturing stainless steel. At this time 50% of Krupp's armaments were sold to Germany, and the rest to 52 other nations. The company had invested worldwide, including in cartels with other international companies. Essen

Essen (; Latin: ''Assindia'') is the central and, after Dortmund, second-largest city of the Ruhr, the largest urban area in Germany. Its population of makes it the fourth-largest city of North Rhine-Westphalia after Cologne, Düsseldorf and Do ...

was the company headquarters. In 1913 Germany jailed a number of military officers for selling secrets to Krupp, in what was known as the "Kornwalzer scandal." Gustav was not himself penalized and fired only a single director, Otto Eccius.

After Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Archduke Franz Ferdinand Carl Ludwig Joseph Maria of Austria, (18 December 1863 – 28 June 1914) was the heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary. His assassination in Sarajevo was the most immediate cause of World War I.

F ...

was assassinated in 1914, Krupp bought his , in Werfen

Werfen () is a market town in the district of St. Johann im Pongau, in the Austrian state of Salzburg. It is mainly known for medieval Hohenwerfen Castle and the Eisriesenwelt ice cave, the largest in the world.

Geography

Werfen is located in ...

in the Austrian Alps, and which was a former residence of the Archbishops of Salzburg.

Gustav led the firm through

Gustav led the firm through World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, concentrating almost entirely on artillery manufacturing, particularly following the loss of overseas markets as a result of the Allied blockade. Vickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public i ...

of England naturally suspended royalty payment

A royalty payment is a payment made by one party to another that owns a particular asset, for the right to ongoing use of that asset. Royalties are typically agreed upon as a percentage of gross or net revenues derived from the use of an asset o ...

s during the war (Krupp held the patent on shell fuses, but back-payment was made in 1926).

In 1916, the German government seized Belgian industry and conscripted Belgian civilians for forced labor in the Ruhr. These were novelties in modern warfare and in violation of the Hague Conventions, to which Germany was a signatory. During the war, Friedrich Krupp Germaniawerft produced 84 U-boats for the German navy, as well as the Deutschland submarine freighter, intended to ship raw material to Germany despite the blockade. In 1918 the Allies named Gustav a war criminal, but the trials never proceeded.

After the war, the firm was forced to renounce arms manufacturing. Gustav attempted to reorient to consumer products, under the slogan "Wir machen alles!" (we make everything!), but operated at a loss for years. The company laid off 70,000 workers but was able to stave off Socialist unrest by continuing severance pay and its famous social services for workers. The company opened a dental hospital to provide steel teeth and jaws for wounded veterans. It received its first contract from the Prussian State railway, and manufactured its first locomotive.

In 1920, the Ruhr Uprising occurred in reaction to the

In 1920, the Ruhr Uprising occurred in reaction to the Kapp Putsch

The Kapp Putsch (), also known as the Kapp–Lüttwitz Putsch (), was an attempted coup against the German national government in Berlin on 13 March 1920. Named after its leaders Wolfgang Kapp and Walther von Lüttwitz, its goal was to undo th ...

. The Ruhr Red Army

The Ruhr Red Army (13 March – 12 April 1920) was an army of between 50,000 and 80,000 left-wing workers who conducted what was known as the Ruhr Uprising (''Ruhraufstand''), in the Weimar Republic. It was the largest armed workers' uprising in ...

, or Rote Soldatenbund, took over much of the demilitarized Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

unopposed. Krupp's factory in Essen

Essen (; Latin: ''Assindia'') is the central and, after Dortmund, second-largest city of the Ruhr, the largest urban area in Germany. Its population of makes it the fourth-largest city of North Rhine-Westphalia after Cologne, Düsseldorf and Do ...

was occupied, and independent republics were declared, but the German Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshape ...

invaded from Westphalia

Westphalia (; german: Westfalen ; nds, Westfalen ) is a region of northwestern Germany and one of the three historic parts of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It has an area of and 7.9 million inhabitants.

The territory of the regio ...

and quickly restored order. Later in the year, Britain oversaw the dismantling of much of Krupp's factory, reducing capacity by half and shipping industrial equipment to France as war reparations

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war.

History

Making one party pay a war indemnity is a common practice with a long history.

...

.

In the hyperinflation of 1923, the firm printed Kruppmarks for use in Essen, where it was the only stable currency. France and Belgium occupied the Ruhr and established martial law. French soldiers inspecting Krupp's factory in Essen were cornered by workers in a garage, opened fire with a machine gun, and killed thirteen. This incident spurred reprisal killings and sabotage across the Rhineland, and when Krupp held a large, public funeral for the workers, he was fined and jailed by the French. This made him a national hero, and he was granted an amnesty by the French after seven months.

Although Krupp was a monarchist at heart, he cooperated with the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

; as a munitions manufacturer his first loyalty was to the government in power. He was deeply involved with the Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshape ...

's evasion of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

, and secretly engaged in arms design and manufacture. In 1921 Krupp bought Bofors

AB Bofors ( , , ) is a former Swedish arms manufacturer which today is part of the British arms concern BAE Systems. The name has been associated with the iron industry and artillery manufacturing for more than 350 years.

History

Located ...

in Sweden as a front company

A front organization is any entity set up by and controlled by another organization, such as intelligence agencies, organized crime groups, terrorist organizations, secret societies, banned organizations, religious or political groups, advocacy ...

and sold arms to neutral nations including the Netherlands and Denmark. In 1922, Krupp established Suderius AG in the Netherlands, as a front company for shipbuilding, and sold submarine designs to neutrals including the Netherlands, Spain, Turkey, Finland, and Japan. German Chancellor Wirth arranged for Krupp to secretly continue designing artillery and tanks, coordinating with army chief von Seeckt and navy chief Paul Behncke. Krupp was able to hide this activity from Allied inspectors for five years, and kept up his engineers' skills by hiring them out to Eastern European governments including Russia.

In 1924, the Raw Steel Association (Rohstahlgemeinschaft) was established in Luxembourg, as a quota-fixing cartel for coal and steel, by France, Britain, Belgium, Luxembourg, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Germany. Germany, however, chose to violate quotas and pay fines, in order to monopolize the Ruhr's output and continue making high-grade steel. In 1926, Krupp began the manufacture of Widia ("Wie Diamant") cobalt-tungsten carbide. In 1928, German industry under Krupp leadership put down a general strike, locking out 250,000 workers, and encouraging the government to cut wages 15%. In 1929, the Chrysler Building was capped with Krupp steel.

Gustav and especially Bertha were initially skeptical of Hitler, who was not of their class. Gustav's skepticism toward the Nazis waned when Hitler dropped plans to nationalize business, the Communists gained seats in the 6 November elections, and Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher

Kurt Ferdinand Friedrich Hermann von Schleicher (; 7 April 1882 – 30 June 1934) was a German general and the last chancellor of Germany (before Adolf Hitler) during the Weimar Republic. A rival for power with Hitler, Schleicher was murdered by ...

suggested a planned economy with price controls. Despite this, as late as the day before President Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fr ...

appointed Hitler Chancellor, Gustav warned him not to do so. However, after Hitler won power, Gustav became enamoured with the Nazis ( Fritz Thyssen described him as "a super-Nazi") to a degree his wife and subordinates found bizarre.

In 1933, Hitler made Gustav chairman of the Reich Federation of German Industry. Gustav ousted Jews from the organization and disbanded the board, establishing himself as the sole-decision maker. Hitler visited Gustav just before the Röhm purge in 1934, which among other things eliminated many of those who actually believed in the "socialism" of "National Socialism." Gustav supported the "Adolf Hitler Endowment Fund of German Industry", administrated by Bormann, who used it to collect millions of Marks from German businessmen. As part of Hitler's secret rearmament program, Krupp expanded from 35,000 to 112,000 employees.

Gustav was alarmed at Hitler's aggressive foreign policy after the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

, but by then he was fast succumbing to senility and was effectively displaced by his son Alfried. He was indicted as a major war criminal at the Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

but never tried, due to his advanced dementia. He was thus the only German to be accused of being a war criminal after both world wars. He was nursed by his wife in a roadside inn near Blühnbach until his death in 1950, and then cremated and interred quietly, since his adopted name was at that time one of the most notorious in the American Zone

Germany was already de facto occupied by the Allies from the real fall of Nazi Germany in World War II on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany on 7 October 1949. The Allies (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Franc ...

.

Alfried's era

As the eldest son of

As the eldest son of Bertha Krupp

Bertha Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach (29 March 1886 – 21 September 1957) was a member of the Krupp family, Germany's leading industrial dynasty of the 19th and 20th centuries. As the elder child and heir of Friedrich Alfred Krupp she was the ...

, Alfried was destined by family tradition to become the sole heir of the Krupp concern. An amateur photographer and Olympic sailor, he was an early supporter of Nazism among German industrialists, joining the SS in 1931, and never disavowing his allegiance to Hitler. According to Manchester, he kept a copy of ''Mein Kampf'' on his bedside table to the day of his death.

His father's health began to decline in 1939, and after a stroke in 1941, Alfried took over full control of the firm, continuing its role as main arms supplier to Germany at war. In 1943, Hitler decreed the Lex Krupp

The Lex Krupp was a document signed into law on 12 November 1943 by Adolf Hitler that made the Krupp company a personal company with specially regulated rules of succession, in order to ensure that the Krupp family enterprise remain intact.

Histo ...

, authorizing the transfer of all Bertha's shares to Alfried, giving him the name "Krupp" and dispossessing his siblings.

During the war, Krupp was allowed to take over many industries in occupied nations, including Arthur Krupp steel works in Berndorf, Austria, the Alsacian Corporation for Mechanical Construction (Elsaessische Maschinenfabrik AG, or ELMAG), Robert Rothschild's tractor factory in France, Škoda Works in Czechoslovakia, and Deutsche Schiff- und Maschinenbau AG ( Deschimag) in Bremen

Bremen ( Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state cons ...

. This activity became the basis for the charge of "plunder" at the war crimes trial of Krupp executives after the war.

As another war crime, Krupp used slave labor, both POWs and civilians from occupied countries, and Krupp representatives were sent to concentration camps to select laborers. Treatment of Slavic and Jewish slaves was particularly harsh, since they were considered sub-human in Nazi Germany, and Jews were targeted for "extermination through labor

Extermination through labour (or "extermination through work", german: Vernichtung durch Arbeit) is a term that was adopted to describe forced labor in Nazi concentration camps in light of the high mortality rate and poor conditions; in some ...

". The number of slaves cannot be calculated due to constant fluctuation but is estimated at 100,000, at a time when the free employees of Krupp numbered 278,000. The highest number of Jewish slave laborers at any one time was about 25,000 in January 1943.

In 1942–1943, Krupp built the Berthawerk factory (named for his mother), near the Markstadt forced labour camp, for production of artillery fuses. Jewish women were used as slave labor there, leased from the SS for 4 Marks a head per day. Later in 1943 it was taken over by Union Werke.

In 1942, although Russia in retreat relocated many factories to the Urals, steel factories were simply too large to move. Krupp took over production, including at the Molotov steel works near Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

and Kramatorsk

Kramatorsk ( uk, Краматорськ, translit=Kramatorsk ) is a city and the administrative centre of Kramatorsk Raion in the northern portion of Donetsk Oblast, in eastern Ukraine. Prior to 2020, Kramatorsk was a city of oblast significan ...

in eastern Ukraine, and at mines supplying the iron, manganese, and chrome vital for steel production.

The battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II where Nazi Germany and its allies unsuccessfully fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (later r ...

in 1942 convinced Krupp that Germany would lose the war, and he secretly began liquidating 200 million Marks in government bonds. This allowed him to retain much of his fortune and hide it overseas.

Beginning in 1943, Allied bombers targeted the main German industrial district in the Ruhr

The Ruhr ( ; german: Ruhrgebiet , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr area, sometimes Ruhr district, Ruhr region, or Ruhr valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 2,800/km ...

. Most damage at Krupp's works was actually to the slave labor camps, and German tank production continued to increase from 1,000 to 1,800 per month. However, by the end of the war, with a manpower shortage preventing repairs, the main factories were out of commission.

On 25 July 1943 the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

attacked the Krupp Works with 627 heavy bombers, dropping 2,032 long tons of bombs in an Oboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

...

-marked attack. Upon his arrival at the works the next morning, Gustav Krupp suffered a fit from which he never recovered.

After the war, the Ruhr became part of the British Zone of occupation. The British dismantled Krupp's factories, sending machinery all over Europe as

After the war, the Ruhr became part of the British Zone of occupation. The British dismantled Krupp's factories, sending machinery all over Europe as war reparations

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war.

History

Making one party pay a war indemnity is a common practice with a long history.

...

. The Russians seized Krupp's Grusonwerk in Magdeburg, including the formula for tungsten steel Tungsten steel is any steel that has tungsten as its alloying element with characteristics derived mostly from the presence of this element (as opposed to any other element in the alloy). Common alloys have between 2% and 18% tungsten by weight alo ...

. Germaniawerft in Kiel was dismantled, and Krupp's role as an arms manufacturer came to an end. Allied High Commission

The Allied High Commission (also known as the High Commission for Occupied Germany, HICOG; in German ''Alliierte Hohe Kommission'', ''AHK'') was established by the United States, the United Kingdom, and France after the 1948 breakdown of the Alli ...

Law 27, in 1950, mandated the decartelization of German industry.

Meanwhile, Alfried was held in Landsberg prison, where Hitler had been imprisoned in 1924. At the Krupp Trial, held in 1947–1948 in Nuremberg following the main

Meanwhile, Alfried was held in Landsberg prison, where Hitler had been imprisoned in 1924. At the Krupp Trial, held in 1947–1948 in Nuremberg following the main Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

, Alfried and most of his co-defendants were convicted of crimes against humanity (plunder and slave labor), while being acquitted of crimes against peace, and conspiracy. Alfried was condemned to 12 years in prison and the "forfeiture of all isproperty both real and personal," making him a pauper. Two years later, on 31 January 1951, John J. McCloy

John Jay McCloy (March 31, 1895 – March 11, 1989) was an American lawyer, diplomat, banker, and a presidential advisor. He served as Assistant Secretary of War during World War II under Henry Stimson, helping deal with issues such as German sa ...

, High Commissioner of the American zone of occupation, issued an amnesty to the Krupp defendants. Much of Alfried's industrial empire was restored, but he was forced to transfer some of his fortune to his siblings, and he renounced arms manufacturing.

By this time, West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

's Wirtschaftswunder

The ''Wirtschaftswunder'' (, "economic miracle"), also known as the Miracle on the Rhine, was the rapid reconstruction and development of the economies of West Germany and Austria after World War II (adopting an ordoliberalism-based social ma ...

had begun, and the Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top:{ ...

had shifted the United States's priority from denazification

Denazification (german: link=yes, Entnazifizierung) was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of the Nazi ideology following the Second World War. It was carried out by remov ...

to anti-Communism

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

. German industry was seen as integral to western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

's economic recovery, the limit on steel production was lifted, and the reputation of Hitler-era firms and industrialists was rehabilitated.

In 1953 Krupp negotiated the Mehlem agreement with the governments of the US, Great Britain and France. Hitler's Lex Krupp

The Lex Krupp was a document signed into law on 12 November 1943 by Adolf Hitler that made the Krupp company a personal company with specially regulated rules of succession, in order to ensure that the Krupp family enterprise remain intact.

Histo ...

was upheld, reestablishing Alfried as sole proprietor, but Krupp mining and steel businesses were sequestered and pledged to be divested by 1959. There is scant evidence that Alfried intended to fulfill his side of the bargain, and he continued to receive royalties from the sequestered industries.

Despite having only 16,000 employees and 16,000 pensioners, Alfried refused to cut pensions. He ended unprofitable businesses including shipbuilding, railway tyres, and farm equipment. He hired

Despite having only 16,000 employees and 16,000 pensioners, Alfried refused to cut pensions. He ended unprofitable businesses including shipbuilding, railway tyres, and farm equipment. He hired Berthold Beitz

Berthold Beitz (; 26 September 1913 – 30 July 2013) was a German industrialist. He was the head of the Krupp steel conglomerate beginning in the 1950s. He was credited with helping to lead the re-industrialization of the Ruhr Valley and r ...

, an insurance executive, as the face of the company, and began a public relations campaign to promote Krupp worldwide, omitting references to Nazism or arms manufacturing. Beginning with Adenauer, he established personal diplomacy with heads of state, making both open and secret deals to sell equipment and engineering expertise. Expansion was significant in the former colonies of Great Britain and behind the Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its ...

, in countries eager to industrialize but suspicious of NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

. Krupp built rolling mills in Mexico, paper mills in Egypt, foundries in Iran, refineries in Greece, a vegetable oil processing plant in Sudan, and its own steel plant in Brazil. In India, Krupp rebuilt Rourkela

Rourkela is a planned city located in the northern district Sundargarh of Odisha, India. It is the third-largest Urban Agglomeration in Odisha after Bhubaneswar and Cuttack. It is situated about west of state capital Bhubaneswar and is surrou ...

in Odisha

Odisha (English: , ), formerly Orissa ( the official name until 2011), is an Indian state located in Eastern India. It is the 8th largest state by area, and the 11th largest by population. The state has the third largest population of ...

as company town similar to his own Essen. In West Germany, Krupp made jet fighters in Bremen, as a joint venture with United Aircraft

The United Aircraft Corporation was an American aircraft manufacturer formed by the break-up of United Aircraft and Transport Corporation in 1934. In 1975, the company became United Technologies.

History

Pre-1930s

1930s

The Air Mail scandal ...

, and built an atomic reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from n ...

in Jülich, partly funded by the government. The company expanded to 125,000 employees worldwide, and in 1959 Krupp was the fourth largest in Europe (after Royal Dutch, Unilever

Unilever plc is a British multinational consumer goods company with headquarters in London, England. Unilever products include food, condiments, bottled water, baby food, soft drink, ice cream, instant coffee, cleaning agents, energy dri ...

, and Mannesmann

Mannesmann was a German industrial conglomerate. It was originally established as a manufacturer of steel pipes in 1890 under the name "Deutsch-Österreichische Mannesmannröhren-Werke AG". (Loosely translated: "German-Austrian Mannesmann pip ...

), and the 12th largest in the world.

1959 was also Krupp's deadline to sell his sequestered industries, but he was supported by other Ruhr industrialists, who refused to place bids. Krupp not only took back control of those companies in 1960, he used a shell company in Sweden to buy the Bochumer Verein für Gussstahlfabrikation AG, in his opinion the best remaining steel manufacturer in West Germany. The Common Market

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

allowed these moves, effectively ending the Allied policy of decartelization. Alfried was the richest man in Europe, and among the world's handful of billionaires.

The treatment of Jews during the war had remained an issue. In 1951, Adenauer acknowledged that "unspeakable crimes were perpetrated in the name of the German people, which impose upon them the obligation to make moral and material amends." Negotiations with the Claims Conference

The Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, or Claims Conference, represents the world's Jews in negotiating for compensation and restitution for victims of Nazi persecution and their heirs. According to Section 2(1)(3) of the Proper ...

resulted in the Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany

The Reparations Agreement between Israel and the Federal Republic of Germany (German: ''Luxemburger Abkommen'' "Luxembourg Agreement" or ''Wiedergutmachungsabkommen'' "'' Wiedergutmachung'' Agreement", Hebrew: ''הסכם השילומים'' ''Hesk ...

. IG Farben

Interessengemeinschaft Farbenindustrie AG (), commonly known as IG Farben (German for 'IG Dyestuffs'), was a German chemical and pharmaceutical conglomerate. Formed in 1925 from a merger of six chemical companies— BASF, Bayer, Hoechst, Agf ...

, Siemens

Siemens AG ( ) is a German multinational conglomerate corporation and the largest industrial manufacturing company in Europe headquartered in Munich with branch offices abroad.

The principal divisions of the corporation are ''Industry'', ''E ...

, Krupp, AEG

Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft AG (AEG; ) was a German producer of electrical equipment founded in Berlin as the ''Deutsche Edison-Gesellschaft für angewandte Elektricität'' in 1883 by Emil Rathenau. During the Second World War, ...

, Telefunken

Telefunken was a German radio and television apparatus company, founded in Berlin in 1903, as a joint venture of Siemens & Halske and the ''Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft'' (AEG) ('General electricity company').

The name "Telefunken" ap ...

, and Rheinmetall

Rheinmetall AG is a German automotive and arms manufacturer, headquartered in Düsseldorf, Germany