Knute Nelson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Knute Nelson (born Knud Evanger; February 2, 1843 – April 28, 1923) was an American attorney and politician active in Wisconsin and Minnesota. A Republican, he served in state and national positions: he was elected to the

In the fall of 1850, Ingebjørg married Nils Olson Grotland, also from Voss. The family of three moved to Skoponong, a Norwegian settlement in Palmyra, Wisconsin. Knud was given the surname Nelson after his stepfather, which eliminated the stigma of being fatherless.

By then 17 years old, Nelson was street-smart and rebellious, with a proclivity for profanity. He was accepted to the school held by Mary Blackwell Dillon, an Irish immigrant with linguistic talents. Nelson proved himself an apt though undisciplined student; he later recalled being whipped up to three times a day.

Still in his teens, Nelson joined the Democratic Party out of admiration for Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. The family moved to the Koshkonong settlement, which by 1850 had more than half of Wisconsin's Norwegian population of 5,000. Nils Olson had bad luck with land purchases and became sickly. Nelson picked up most of the work of the farm, but maintained his commitment to education. Olson was not supportive and Nelson often had to scrounge to find money for schoolbooks.

Nelson's academic interests led him to enroll in Albion Academy in

In the fall of 1850, Ingebjørg married Nils Olson Grotland, also from Voss. The family of three moved to Skoponong, a Norwegian settlement in Palmyra, Wisconsin. Knud was given the surname Nelson after his stepfather, which eliminated the stigma of being fatherless.

By then 17 years old, Nelson was street-smart and rebellious, with a proclivity for profanity. He was accepted to the school held by Mary Blackwell Dillon, an Irish immigrant with linguistic talents. Nelson proved himself an apt though undisciplined student; he later recalled being whipped up to three times a day.

Still in his teens, Nelson joined the Democratic Party out of admiration for Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. The family moved to the Koshkonong settlement, which by 1850 had more than half of Wisconsin's Norwegian population of 5,000. Nils Olson had bad luck with land purchases and became sickly. Nelson picked up most of the work of the farm, but maintained his commitment to education. Olson was not supportive and Nelson often had to scrounge to find money for schoolbooks.

Nelson's academic interests led him to enroll in Albion Academy in

Nelson returned to Albion in the spring of 1861, when the

Nelson returned to Albion in the spring of 1861, when the

Nelson was already interested in moving further west when in 1870 he was invited by Lars K. Aaker to set up a practice in

Nelson was already interested in moving further west when in 1870 he was invited by Lars K. Aaker to set up a practice in

Nelson served in the

Nelson served in the

Nelson's campaign for election to the United States Senate was reported to have begun early in 1894. It was conducted quietly and behind the scenes, to avoid the appearance that his bid for governorship was less than genuine, and to avoid an internal Republican feud with incumbent U.S. Senator

Nelson's campaign for election to the United States Senate was reported to have begun early in 1894. It was conducted quietly and behind the scenes, to avoid the appearance that his bid for governorship was less than genuine, and to avoid an internal Republican feud with incumbent U.S. Senator

Nelson always took care in public to define himself first and foremost as an American, with no conflicted loyalty to his birth country. But in the background he supported Norway in various ways, notably by inviting Norwegian officers to observe and learn from American tactics in Cuba. He had been planning a trip to Norway for some time, but made sure he would also visit

Nelson always took care in public to define himself first and foremost as an American, with no conflicted loyalty to his birth country. But in the background he supported Norway in various ways, notably by inviting Norwegian officers to observe and learn from American tactics in Cuba. He had been planning a trip to Norway for some time, but made sure he would also visit  He traveled alone and made his home town of Evanger one of the first stops. He arrived at the village in a horse-drawn buggy with only his luggage and was received as an honored guest. He spoke in his native

He traveled alone and made his home town of Evanger one of the first stops. He arrived at the village in a horse-drawn buggy with only his luggage and was received as an honored guest. He spoke in his native

Minnesota Legislators Past and Present

and hi

gubernatorial records

are available for research use at th

Minnesota Historical Society.

* *

Knute Nelson in MNopedia, the Minnesota Encyclopedia

{{DEFAULTSORT:Nelson, Knute 1843 births 1923 deaths People from Voss Norwegian emigrants to the United States Wisconsin Democrats Wisconsin Republicans Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Minnesota Republican Party United States senators from Minnesota Republican Party governors of Minnesota Governors of Minnesota Members of the Wisconsin State Assembly Minnesota state senators People from Alexandria, Minnesota Politicians from Madison, Wisconsin Lawyers from Madison, Wisconsin People from Palmyra, Wisconsin People from Koshkonong, Wisconsin 19th-century American lawyers American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law People of Wisconsin in the American Civil War

Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

and Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

legislatures and to the U.S. House of Representatives and the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

from Minnesota, and served as the 12th governor of Minnesota from 1893 to 1895. Having served in the Senate for 28 years, 55 days, he is the longest-serving Senator in Minnesota's history.

Nelson is known for promoting the Nelson Act of 1889

An act for the relief and civilization of the Chippewa Indians in the State of Minnesota (51st-1st-Ex.Doc.247; ), commonly known as the Nelson Act of 1889, was a United States federal law intended to relocate all the Anishinaabe people in Minnesot ...

to consolidate Minnesota's Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

/ Chippewa on a reservation in western Minnesota and break up their communal land by allotting it to individual households, with sales of the remainder to anyone, including non-natives. This was similar to the Dawes Act of 1887, which applied to Native American lands in the Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

.

Early life and education

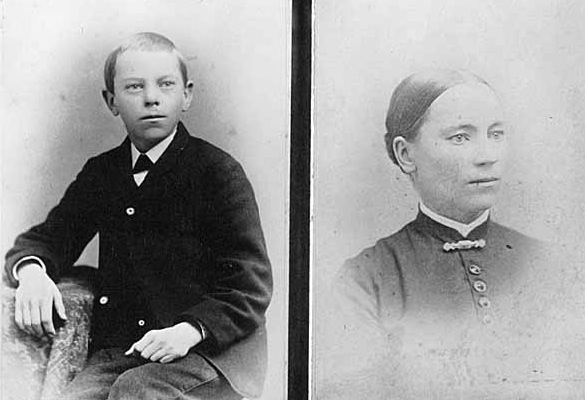

Knute Nelson was born out of wedlock in Evanger, near Voss, Norway, to Ingebjørg Haldorsdatter Kvilekval, who named him Knud Evanger. He was baptized by his uncle on their farm of Kvilekval, who recorded his father as Helge Knudsen Styve. This is unconfirmed. Various theories persist about Knud's paternity, including one involvingGjest Baardsen

Gjest Baardsen (1791 – 13 May 1849) was a Norwegian outlaw, jail-breaker, non-fiction writer, songwriter and memoirist. He was among the most notorious criminals in Norway in the 19th century.

Personal life

Baardsen was born in Sogndalsfjør ...

, a famous outlaw.Millard L Gieske and Steven J Keillor: ''Norwegian Yankee: Knute Nelson and the Failure of American Politics 1860–1923''. 1995: Norwegian-American Historical Association, Northfield, Minnesota. , pps. 3–7

In 1843, Ingebjørg's brother Jon Haldorsson sold the farm where she and Knud lived, as he could not make a living, and emigrated to Chicago. Ingebjørg took Knud with her to Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Vestland county on the Western Norway, west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the list of towns and cities in Norway, secon ...

, where she worked as a domestic servant. Having borrowed money for the passage, she and six-year-old Knud emigrated to the United States, arriving in Castle Garden in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

on July 4, 1849. The holiday fireworks made a lasting impression on Knud, who was listed in immigration records as "Knud Helgeson Kvilekval". Ingebjørg Haldorsdatter claimed to be a widow (a story she stuck to until 1923). She and Knud traveled by the Hudson River to Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York Cit ...

, and then via the Erie Canal to Buffalo.

They continued across the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

to Chicago. There her brother Jon, now working as a carpenter, took them in.Minnesota Historical Society: ''Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society'', 1908, pp. 328–355 While with him, Ingebjørg worked as a domestic servant and paid off her debt for passage in less than a year. Knud also worked, first as a house servant, then as a paperboy for the ''Chicago Free Press,'' which gave him an early education, both because he read the paper and because he learned street profanity.

In the fall of 1850, Ingebjørg married Nils Olson Grotland, also from Voss. The family of three moved to Skoponong, a Norwegian settlement in Palmyra, Wisconsin. Knud was given the surname Nelson after his stepfather, which eliminated the stigma of being fatherless.

By then 17 years old, Nelson was street-smart and rebellious, with a proclivity for profanity. He was accepted to the school held by Mary Blackwell Dillon, an Irish immigrant with linguistic talents. Nelson proved himself an apt though undisciplined student; he later recalled being whipped up to three times a day.

Still in his teens, Nelson joined the Democratic Party out of admiration for Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. The family moved to the Koshkonong settlement, which by 1850 had more than half of Wisconsin's Norwegian population of 5,000. Nils Olson had bad luck with land purchases and became sickly. Nelson picked up most of the work of the farm, but maintained his commitment to education. Olson was not supportive and Nelson often had to scrounge to find money for schoolbooks.

Nelson's academic interests led him to enroll in Albion Academy in

In the fall of 1850, Ingebjørg married Nils Olson Grotland, also from Voss. The family of three moved to Skoponong, a Norwegian settlement in Palmyra, Wisconsin. Knud was given the surname Nelson after his stepfather, which eliminated the stigma of being fatherless.

By then 17 years old, Nelson was street-smart and rebellious, with a proclivity for profanity. He was accepted to the school held by Mary Blackwell Dillon, an Irish immigrant with linguistic talents. Nelson proved himself an apt though undisciplined student; he later recalled being whipped up to three times a day.

Still in his teens, Nelson joined the Democratic Party out of admiration for Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. The family moved to the Koshkonong settlement, which by 1850 had more than half of Wisconsin's Norwegian population of 5,000. Nils Olson had bad luck with land purchases and became sickly. Nelson picked up most of the work of the farm, but maintained his commitment to education. Olson was not supportive and Nelson often had to scrounge to find money for schoolbooks.

Nelson's academic interests led him to enroll in Albion Academy in Albion, Dane County, Wisconsin

Albion is a town in Dane County, Wisconsin, United States, located about 27 miles southeast of Madison on Interstate 90. The population was 1,823 at the 2000 Census. The unincorporated communities of Albion, Highwood, Hillside, and Indian Heig ...

, in the fall of 1858. The school was founded by the Seventh-day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbath, and ...

to provide education to children who could not afford private school; Nelson was deemed "very deserving." To earn his keep he did various jobs around the school.

After two years, Nelson took a job as a country teacher in Pleasant Springs, near Stoughton. Teaching mostly other Norwegian immigrants, he was an agent of Americanization.

Military service

Nelson returned to Albion in the spring of 1861, when the

Nelson returned to Albion in the spring of 1861, when the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

had started. By then, he had developed his position as a "low-tariff, anti-slavery, pro-Union Democrat," but was in the minority in a pro-Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

region. In May 1861, he and 18 other Albion students enlisted in a state militia company known as the Black Hawk Rifles of Racine

Jean-Baptiste Racine ( , ) (; 22 December 163921 April 1699) was a French dramatist, one of the three great playwrights of 17th-century France, along with Molière and Corneille as well as an important literary figure in the Western traditi ...

, to fight with the Union Army in the war. Appalled by its debauchery, the young men refused to be sworn into the army under this militia, and eventually succeeded in being transferred to the 4th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment. This was an "all-American" regiment, made up generally of native-born men.

Nelson's parents opposed his volunteering, but he saw it as his duty. He sent half his soldier's pay to his parents to help retire the debt on the farm. He seems to have enjoyed army life, noting that the food was better than at home. He shared his fellow soldiers' frustration at not being put into battle soon enough. His unit moved from Racine to Camp Dix

Fort Dix, the common name for the Army Support Activity (ASA) located at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst, is a United States Army post. It is located south-southeast of Trenton, New Jersey. Fort Dix is under the jurisdiction of the Air Force A ...

near Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

, Maryland. From there they moved to combat operations in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

.

On May 27, 1863, after the 4th Wisconsin became a cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

unit, Nelson was wounded in the Battle of Port Hudson

The siege of Port Hudson, Louisiana, (May 22 – July 9, 1863) was the final engagement in the Union (American Civil War), Union campaign to recapture the Mississippi River in the American Civil War.

While Major General#United States, Union Gen ...

, captured and made a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of ...

. He was released when the siege ended. He served as an adjutant, was promoted to corporal, and briefly considered applying for a lieutenant's commission.

Military service sharpened Nelson's identity as an American and his patriotism. He was deeply concerned about what he considered the ambivalent attitude among Norwegian-American Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

clergy toward slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, and thought that too few of his fellow Norwegian Americans from Koshkonong had volunteered. He read the Norwegian translation of Esaias Tegnér

Esaias Tegnér (; – ) was a Swedish writer, professor of the Greek language, and bishop. He was during the 19th century regarded as the father of modern poetry in Sweden, mainly through the national romantic epic ''Frithjof's Saga''. He has b ...

's '' Friðþjófs saga ins frœkna'' and found it enthralling. Its unsentimental depiction of character and virtue he found to be a synthesis of his Norwegian heritage and American home.

Within two years after he mustered out, Nelson acquired his United States citizenship. His disdain for the Copperheads contributed to his becoming a Republican after the war.

Political career

Local politics in Wisconsin

Nelson returned to Albion and completed his studies as one of the oldest students, graduating at the top of his class. He gave his first campaign speech of record on behalf of Lincoln, and drew praise from the faculty. Deciding to become a lawyer, Nelson moved toMadison Madison may refer to:

People

* Madison (name), a given name and a surname

* James Madison (1751–1836), fourth president of the United States

Place names

* Madison, Wisconsin, the state capital of Wisconsin and the largest city known by this ...

, where he studied law in the office of William F. Vilas

William Freeman Vilas (July 9, 1840August 27, 1908) was an American lawyer, politician, and United States Senator. In the U.S. Senate, he represented the state of Wisconsin for one term, from 1891 to 1897. As a prominent Bourbon Democrat, he wa ...

, one of the few academically trained attorneys in the area. In the spring of 1867, Judge Philip L. Spooner admitted him to the Wisconsin bar.

Nelson opened his law practice in Madison, where he appealed to the Norwegian immigrant community, advertising in the Norwegian language newspaper ''Emigranten''. He also became Madison's unofficial representative of the Norwegian community. With Eli A. Spencer's help, he successfully ran for Dane County's seat in the Wisconsin State Assembly

The Wisconsin State Assembly is the lower house of the Wisconsin Legislature. Together with the smaller Wisconsin Senate, the two constitute the legislative branch of the U.S. state of Wisconsin.

Representatives are elected for two-year terms, e ...

, starting its session on January 8, 1868.

He was reelected to a second term in the Assembly, as he had quickly learned how to get things done in politics. He got involved in a divisive debate about public and parochial schools in Norwegian communities, taking the "liberal" side that promoted public, non-sectarian schools rather than those run by Lutheran clergy. After his second term in the Assembly, Nelson decided not to run for a third.

Marriage and family

After being elected the first time, Nelson married Nicholina Jacobsen, originally fromToten

Toten is a traditional district in Innlandet county in the eastern part of Norway. It consists of the municipalities Østre Toten and Vestre Toten.

The combined population of Toten is approximately 27,000. The largest town is Raufoss with appro ...

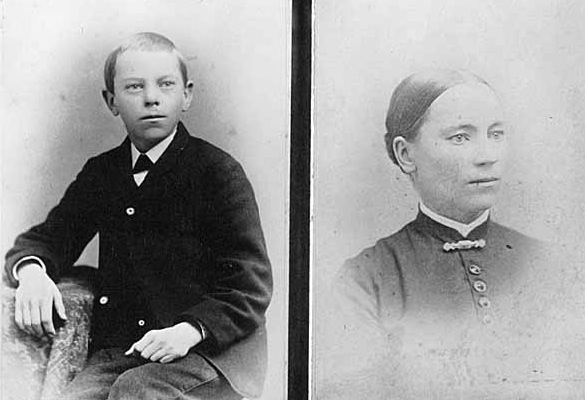

, Norway, in 1868. She was five months pregnant by the time of their marriage and, because of Nelson's poor relations with local Lutheran clergy, they were married by Justice of the Peace Lars Erdall in a private home.

A national recession limited the couple's financial success. While Nelson slept in his office in Madison during his legislative and professional career, Nicholina and the newborn Ida stayed with her family in Koshkonong.

Minnesota frontier

Nelson was already interested in moving further west when in 1870 he was invited by Lars K. Aaker to set up a practice in

Nelson was already interested in moving further west when in 1870 he was invited by Lars K. Aaker to set up a practice in Alexandria, Minnesota

Alexandria is a city in and the county seat of Douglas County, Minnesota, United States. First settled in 1858, it was named after brothers Alexander and William Kinkead from Maryland. The form of the name alludes to Alexandria, Egypt, a center ...

, in Douglas County, part of the state's "Upper Country." Nelson was attracted by the possibilities afforded by the opening frontier, especially the prospect of the railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

. After also visiting Fergus Falls, he moved his wife and newborn son Henry to Alexandria in August 1871.

He was admitted to the Minnesota bar in October and set up a legal practice primarily around land cases referred to him by Aaker, the land agent. He also bought a homestead in Alexandria, a claim that was contested but which he won. He also became an accomplished trial lawyer, was elected the Douglas County attorney, and acted as the county attorney for Pope County. As was typically the case at that time, Nelson's legal work on land issues got him involved in political issues. He became a champion for the economic development of the Upper Country through the introduction of the railroad.

Minnesota state senator

The so-called "Aaker faction" within the Upper County Republican party found in Nelson a capable politician, with connections to the immigrant community, experience in land-office issues, and political background in Wisconsin. He was put forward as a Republican candidate for theMinnesota Senate

The Minnesota Senate is the upper house of the Legislature of the U.S. state of Minnesota. At 67 members, half as many as the Minnesota House of Representatives, it is the largest upper house of any U.S. state legislature. Floor sessions are h ...

in 1874, running against banker Francis Bennett Van Hoesen, who was aligned with the Grange movement

The Grange, officially named The National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry, is a social organization in the United States that encourages families to band together to promote the economic and political well-being of the community and ...

and state Anti-Monopoly Party

The Anti-Monopoly Party was a short-lived American political party. The party nominated Benjamin F. Butler for President of the United States in 1884, as did the Greenback Party, which ultimately supplanted the organization.

Organizational hi ...

. Though Nelson did not get unanimous support from his Norwegian-American constituency, he carried 59% of the vote and four out of five counties in his constituency.

Nelson's first challenge in the state senate, whether to reelect Alexander Ramsey

Alexander Ramsey (September 8, 1815 April 22, 1903) was an American politician. He served as a Whig and Republican over a variety of offices between the 1840s and the 1880s. He was the first Minnesota Territorial Governor.

Early years and fa ...

to a third term in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

, was contentious, as it was against Governor Cushman Davis

Cushman Kellogg Davis (June 16, 1838November 27, 1900) was an American United States Republican Party, Republican politician who served as the List of Governors of Minnesota, seventh Governor of Minnesota and as a United States Senate, U.S. Senat ...

's wishes. Nelson was caught between his allegiance to the Douglas County Republicans, who were staunch Davis supporters, and his land office constituency, who favored Ramsey. Nelson voted for Ramsey, the dark-horse candidate William D. Washburn

William Drew "W.D." Washburn, Sr. (January 14, 1831 – July 29, 1912) was an American politician. He served in both the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate as a Republican from Minnesota. Three of his seven ...

, and finally for the victor, Samuel J. R. McMillan.

Nelson spent more time on the issue of extending the railroad infrastructure into the Upper Country. His constituents elected him in large part to resolve the gridlock that prevented the completion of the railroad extension from St. Cloud west to Alexandria and beyond. The railroad company, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad (SP&P), had run out of funds to complete the St. Vincent extension, and the bondholders were unwilling to invest further. The Minnesota legislature agreed on the need for the railroad but were not in a position to pay for its completion.

In 1875, Nelson introduced the Upper Country bill, which gave SP&P added incentives in the form of land to complete the line, but also imposed a deadline after which the rights to build the railroad were forfeited, presumably in favor of Northern Pacific, whose plans would bypass Alexandria. The bill met with controversy from both sides of the issue and was ultimately amended to the point that Nelson first sought to table it and then abstained from voting on it. The bill was enacted and was considered a success in its time, with most of the credit going to Nelson.

It took several years for the various financial and political matters to be sorted out for the railroad, and Nelson played an active role throughout, both as an elected official, attorney, and businessman. He secured rights-of-way for virtually the entire line from Alexandria to Fergus Falls, negotiating with many stakeholders for every tract of land. This proved to be an all-consuming effort for several years, though he ran unsuccessfully for lieutenant governor of Minnesota in 1879.

In May 1877, three of Nelson's five children died during a diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild clinical course, but in some outbreaks more than 10% of those diagnosed with the disease may die. Signs and s ...

epidemic. The two oldest, Ida and Henry, survived.

In November 1878, the railroad finally reached Alexandria, thanks in large part to Nelson's close working relationship with James J. Hill. Several Minnesota towns were founded as a result of these efforts, including Nelson and Ashby.

National politics

Nelson was invited to deliver the "oration of the day" at the United States Centennial on July 4, 1876, in Alexandria, exactly 27 years after he had immigrated to the United States. The "unimpassioned" speech sought to reinforce an American identity and made no mention of his Norwegian roots. It coincided with his campaign for U.S. representative from Minnesota's third district. By then, Nelson had developed the strategy of orchestrating a "bottoms-up" campaign in which he would quietly enlist supporters to publicly encourage him to run, while appearing reluctant. His constituency in the Upper Country frontier put him at a disadvantage with respect to the rivaling Twin Cities. After having flexed his political muscle by "bolting" from the campaign for a few weeks, he supported the Republican nomination of Jacob Stewart, a medical doctor from St. Paul, who won the election against Democrat William McNair. This endorsement was not backed by the Norwegian-American community, who were concerned about Stewart's association with theKnow Nothing Party

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

and the apparent rise of a ruling class in society.

The battle for the "Bloody Fifth"

As a result of the 1880 census, the United States Congress decided to allocate a new congressional seat to the Upper Country, creating the Fifth Minnesota District. Nelson quietly entered the race for this seat. First he secured a seat on theBoard of Regents

In the United States, a board often governs institutions of higher education, including private universities, state universities, and community colleges. In each US state, such boards may govern either the state university system, individual c ...

at the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public land-grant research university in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. ...

, where he managed to establish a Department of Scandinavian Studies.

The campaign opened in 1882 and quickly devolved into one of the most contentious elections in history at that point. The contest between Nelson and Charles F. Kindred for the "Bloody Fifth", as it became known, involved widespread graft, intimidation, and election fraud. The Republican convention on July 12 in Detroit Lakes

Detroit Lakes is a city in the State of Minnesota and the county seat of Becker County. The population was 9,869 at the 2020 census. Its unofficial population during summer months is much higher, estimated by citizens to peak at 13,000 mids ...

was compared to the historic Battle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne ( ga, Cath na Bóinne ) was a battle in 1690 between the forces of the deposed King James II of England and Ireland, VII of Scotland, and those of King William III who, with his wife Queen Mary II (his cousin and J ...

in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

. 150 delegates fought over 80 seats, and after a scuffle in the main conference center, the Kindred and Nelson campaigns nominated their candidates.

The rivalry between Kindred and Nelson centered to a large extent on the two competing railroads in the Upper Country, the Northern Pacific in Kindred's corner and the Great Northern Great Northern may refer to:

Transport

* One of a number of railways; see Great Northern Railway (disambiguation).

* Great Northern Railway (U.S.), a defunct American transcontinental railroad and major predecessor of the BNSF Railway.

* Great ...

in Nelson's. Kindred spent between $150,000 and $200,000, but Nelson won handily, overcoming massive election fraud in Northern Pacific counties.

U.S. House of Representatives, 1883–1889

Nelson served in the

Nelson served in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

from March 4, 1883, to March 4, 1889, in the 48th, 49th, and 50th congresses. In keeping with practices of the Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Wes ...

, his first agenda item in Congress was to ensure patronage for his supporters in Minnesota by doling out the limited number of federal appointments available. Most were made through Paul C. Sletten, the Receiver of the U.S. Land Office in Crookston. In addition to rewarding political support, he replaced pro-Kindred appointees in the forested counties around the Northern Pacific Railroad

The Northern Pacific Railway was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by Congress in 1864 and given nearly of land grants, whi ...

, the so-called "Pineries." Particularly publicized was the firing of Søren Listoe as Register of the U.S. Land Office in Fergus Falls.

Nelson did not always follow the orthodox Republican line in the House. In 1886, he abandoned the Republican caucus to vote for the Morrison Tariff Bill of 1886, which sought to reduce the tariffs on some imported items. Two years later, he and three other Republicans voted for the more aggressive tariff reductions in the Mills Tariff Bill of 1888. Although passed by the House on July 21, 1888, the Mills Bill was so heavily amended by the high-tariff Republicans in the Senate that the House found the result unacceptable, and no changes to the tariff were made in 1888.

Nelson was frustrated by what he perceived as the House's lack of effectiveness. He got involved in long debates about pension issues for Civil War veterans. His most notable legacy as a representative was passing the Nelson Act of 1889

An act for the relief and civilization of the Chippewa Indians in the State of Minnesota (51st-1st-Ex.Doc.247; ), commonly known as the Nelson Act of 1889, was a United States federal law intended to relocate all the Anishinaabe people in Minnesot ...

. It created the White Earth Indian Reservation

The White Earth Indian Reservation ( oj, Gaa-waabaabiganikaag, "Where there is an abundance of white clay") is the home to

the White Earth Band, located in northwestern Minnesota. It is the largest Indian reservation in the state by land area. T ...

in western Minnesota as a place to consolidate Native Americans from other reservations in the state, allocated communal land to heads of households, and opened up sale of the remaining thousands of acres of land to immigrants, at Native Americans' expense.

Considering his time in the House a "personal failure", Nelson decided not to seek reelection in 1888. Some suspect that a narrow escape from a drowning accident on October 11, 1886, also played a role in increasing his ambition.

Governor of Minnesota, 1893–1895

Though Nelson claimed to retire from politics, he remained an active insider in Minnesota Republican politics. In 1890 he started showing interest in running for governor. Meanwhile, he resumed an active law practice from Alexandria, continued running his farm, and opened a hardware store. Increasing pressure on the Minnesotan agricultural economy gave rise to theFarmers' Alliance

The Farmers' Alliance was an organized agrarian economic movement among American farmers that developed and flourished ca. 1875. The movement included several parallel but independent political organizations — the National Farmers' Alliance and ...

, which became a formidable political force in both parties, but especially the Republican Party. In 1890, the alliance voted to run its own candidates, and suggested nominating Nelson. In the Minnesota alliance convention in July 1890, Nelson did not acknowledge interest from the delegates, who ended up nominating Sidney M. Owen. But after the Alliance made a strong showing in the 1890 legislative election, Republicans saw Nelson as a strong alternative to the Alliance in the Upper Country.

Nelson worked to strengthen his candidacy for governor, though historians suggest that his ultimate goal was the U.S. Senate. He arranged to be drafted as a candidate rather than actively pursuing office. Appointed officeholders, fearing the loss of patronage to Alliance political victories, were glad to support him. Appealing to the Republican need for unity at the convention, Nelson maneuvered to gain the support of rivals such as Davis and Washburn, or at least avoid their opposition. He was unanimously nominated by 709 delegates as the Republican candidate for governor on July 28, 1892, at the St. Paul People's Church. His acceptance speech was a libertarian broadside against both Democrats and Populists; it emboldened the delegates for the campaign.

The ensuing campaign against Democratic nominee Daniel Lawler and Populist Ignatius Donnelly centered on allegations of undue influence by railroad interests, tariffs, and ethnicity and patriotism. When Nelson took the campaign to northwestern Minnesota, he had a minor physical altercation with Tobias Sawby, a local populist. After a grueling campaign, he carried 51 of 80 counties with 42.6% of the vote to Lawler's 37% and Donnelly's 15.6%. He gave a short victory speech in Alexandria, saying, "I go in without having made any promises to any combine, corporation, or person, and shall endeavor to do right, because it is right, and I endeavor to give an administration for the people, for the people, and by the people."

There were significant limitations on Governor Nelson's ability to pursue his agenda. The balance of power in Minnesota was shared among five independently elected officials, the state legislature, and the governor. In his inaugural speech on January 4, 1893, he presented himself as a fiscal conservative with an affinity for education and dwelled on statistics related to various state services and for solutions.

Nelson used his governorship as a bully pulpit for modest Republican reforms intended to provide moderate alternatives to the radical Populist actions. He promoted the "Governor's Grain Bill" as a way to regulate trade in grain, specifically by giving the Railroad and Warehouse Commission the authority to license, inspect, and regulate country grain elevators. Republican members of the legislature supported it as well, going so far as making it a party measure. Opposition to the bill from Democrats and Populists was based on suspicion of the railroad commission. The bill went through two rounds of voting with considerable horse-trading but in the end won narrowly, giving Nelson credibility as a political force.

Nelson also ended up cooperating with his former adversary Donnelly on the "timber ring" investigation; it sought to end land claim fraud in lumber areas. Nelson convened an interstate antitrust Conference in Chicago on June 5, 1893, where he spoke against the lumber trust and in favor of strengthening the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (, ) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce. It was passed by Congress and is named for Senator John Sherman, its principal author.

T ...

.

The Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

created a crisis for the railroad companies. After a series of wage cuts by the Great Northern, the American Railway Union

The American Railway Union (ARU) was briefly among the largest labor unions of its time and one of the first industrial unions in the United States. Launched at a meeting held in Chicago in February 1893, the ARU won an early victory in a strike ...

went on strike on April 13. Nelson suggested the parties engage in arbitration while demanding law and order from the strikers. He left enforcement to federal marshals and arbitration to private business leaders. The strike was resolved largely in favor of the workers, and Nelson survived untarnished.

Nelson was handily renominated in 1894, and ran against Populist Sidney Owen and Democrat George Becker. He projected the image of a systematic and scientific reformer compared to such populist speakers as Mary Ellen Lease and Jerry Simpson

Jeremiah Simpson (March 31, 1842 – October 23, 1905), nicknamed "Sockless Jerry" Simpson, was an American politician from the U.S. state of Kansas. An old-style populist, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives three ti ...

. He demonstrated hands-on leadership in the dry summer of 1894, when the Great Hinckley Fire spread across east-central Minnesota on September 1. Although the state did not have the financial means to provide direct support, Nelson used his office to encourage private relief efforts. He won the election with 60,000 more votes than Owen."Nelson Governor of Minnesota," ''New York Times'', November 7, 1894

United States Senator, 1895–1923

Nelson vs. Washburn

Nelson's campaign for election to the United States Senate was reported to have begun early in 1894. It was conducted quietly and behind the scenes, to avoid the appearance that his bid for governorship was less than genuine, and to avoid an internal Republican feud with incumbent U.S. Senator

Nelson's campaign for election to the United States Senate was reported to have begun early in 1894. It was conducted quietly and behind the scenes, to avoid the appearance that his bid for governorship was less than genuine, and to avoid an internal Republican feud with incumbent U.S. Senator William D. Washburn

William Drew "W.D." Washburn, Sr. (January 14, 1831 – July 29, 1912) was an American politician. He served in both the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate as a Republican from Minnesota. Three of his seven ...

. Before the 17th Amendment went into effect in 1914, state legislatures elected their U.S. senators. Nelson's campaign for Senate was a "still hunt," consisting of building support among incoming legislators while letting Washburn think he was running unopposed for the Republican nomination.

Sensing Nelson's rising star in the Republican establishment, Washburn tried to obtain Nelson's unequivocal assurance that he was not running for Senate, while solidifying his own standing as the Minneapolis candidate. On September 21, 1894, the two candidates met at the Freeborn county fair in Albert Lea, where Nelson was asked directly whether he supported Washburn's candidacy or had his own designs on the seat. He reportedly advised the state legislature to "elect your Republican legislative ticket, so as to send my friend Washburn back the United States senate, or if you do not like him, send some other good Republican."

Nelson's strategy was to prevent Washburn from gaining a straightforward majority in either the nomination or the election in the Republican caucus, and to appear as a unifying choice for the Republicans. He had to strike a fine balance between appealing to Scandinavian ethnic pride on the one hand and affirming himself a true American on the other, and between the appearance of treachery against Washburn and maintaining an honest impression.

The campaign came to a head in the so-called "Three Week War" or "Hotel Campaign", which was in full force by January 5, 1895. The confrontations, lobbying, cajoling, and alleged bribery centered on St. Paul's Windsor and Merchants hotels. Legislators were unnerved by the campaign, and the outcome remained uncertain. Return visits to their constituencies in mid-January did little to clarify public opinion. Public meetings with "wirepullers" had similarly little effect.

Nelson's strength became apparent but was not yet decisive on January 18 when the Republicans caucused. Washburn fell well short of reaching the necessary 72 votes, and a number of erstwhile supporters fell to Nelson on the second ballot. By the time the election went to the full legislature, it was clear that Washburn had lost. On January 23 Nelson was elected to the United States Senate, the first Scandinavian-born American to reach this post. Exhausted from the campaign, Washburn called for direct, popular elections of senators. It is remembered as one of the bitterest elections in Minnesota political history.

Washburn was perceived as a wealthy, urban, aristocratic native Yankee

The term ''Yankee'' and its contracted form ''Yank'' have several interrelated meanings, all referring to people from the United States. Its various senses depend on the context, and may refer to New Englanders, residents of the Northern United S ...

from Maine, and Nelson as a hard-working immigrant from the Upper Country. Nelson's victory reinforced the growing influence of areas of Minnesota outside the Twin Cities, and strengthened political awareness among ethnic Scandinavians in the region. Nelson decided early to make this image his platform, asking his constituency to call him "Uncle Knute."

First Senate term

The54th United States Congress

The 54th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1895 ...

did not convene until December 1895, and though Nelson was eager to get to work, he spent the recess traveling and working on his farm. He also translated the Constitution of Norway

nb, Kongeriket Norges Grunnlov

nn, Kongeriket Noregs Grunnlov

, jurisdiction = Kingdom of Norway

, date_created =10 April - 16 May 1814

, date_ratified =16 May 1814

, system =Constitutional monarchy

, ...

to English and studied the Free Silver

Free silver was a major economic policy issue in the United States in the late 19th-century. Its advocates were in favor of an expansionary monetary policy featuring the unlimited coinage of silver into money on-demand, as opposed to strict adhe ...

issue. This was the subject of his first Senate speech, on December 31, 1895, when he advocated a paper currency

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes were originally issued ...

.

Nelson maintained—as he did throughout his career—a strong anti-Populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develop ...

, though pragmatic, profile. His most important first-term accomplishment was probably the Nelson Bankruptcy Law, intended to give farmers the means to enter into voluntary, as opposed to forced, bankruptcy by creditors. He positioned this as an alternative to the Judiciary Committee that was much harsher to debtors. Although he championed the bill on its own merits, it also gave him an opportunity both to disassociate himself from his background as an attorney and to build favor with his agricultural constituency. After 18 months of painstaking negotiations, Nelson managed to get the bill passed by Congress on June 24, 1898. Filing bankruptcy would be known for some time afterwards as "taking the Nelson cure."

If Nelson showed independence in the bankruptcy law, he toed the party line on the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

, enthusiastically supporting the war effort. He got embroiled in a bitter debate on the Senate floor on the issue of annexing the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

and Hawaii. He and one of the authors of the treaty, senior Minnesota senator Cushman Davis

Cushman Kellogg Davis (June 16, 1838November 27, 1900) was an American United States Republican Party, Republican politician who served as the List of Governors of Minnesota, seventh Governor of Minnesota and as a United States Senate, U.S. Senat ...

, voted with the majority in ratifying the Treaty of Paris. He is often quoted as saying:

Providence has given the United States the duty of extending Christian civilization. We come as ministering angels, not despots.

Return to Norway

Nelson always took care in public to define himself first and foremost as an American, with no conflicted loyalty to his birth country. But in the background he supported Norway in various ways, notably by inviting Norwegian officers to observe and learn from American tactics in Cuba. He had been planning a trip to Norway for some time, but made sure he would also visit

Nelson always took care in public to define himself first and foremost as an American, with no conflicted loyalty to his birth country. But in the background he supported Norway in various ways, notably by inviting Norwegian officers to observe and learn from American tactics in Cuba. He had been planning a trip to Norway for some time, but made sure he would also visit Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

and Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

, emphasizing his Scandinavian-American background.

He traveled alone and made his home town of Evanger one of the first stops. He arrived at the village in a horse-drawn buggy with only his luggage and was received as an honored guest. He spoke in his native

He traveled alone and made his home town of Evanger one of the first stops. He arrived at the village in a horse-drawn buggy with only his luggage and was received as an honored guest. He spoke in his native dialect

The term dialect (from Latin , , from the Ancient Greek word , 'discourse', from , 'through' and , 'I speak') can refer to either of two distinctly different types of linguistic phenomena:

One usage refers to a variety of a language that is ...

of Vossemål, slipping into Riksmål

(, also , ) is a written Norwegian language form or spelling standard, meaning the ''National Language'', closely related and now almost identical to the dominant form of Bokmål, known as .

Both Bokmål and Riksmål evolved from the Danish wri ...

only when he felt it necessary to make an important political point. His hosts quickly started addressing him in the familiar "du Knut," which he appeared to enjoy.

From Evanger, Nelson traveled to Kristiania

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population o ...

, where he refused official honors, and to Stockholm

Stockholm () is the capital and largest city of Sweden as well as the largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.6 million in the urban area, and 2.4 million in the metropo ...

, where he made even less fuss. He spent a week in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan a ...

, visiting with his own patronage appointees Laurits S. Swenson, U.S. ambassador to Denmark, and Søren Listoe, consul to Rotterdam. He had an audience with King Christian IX

Christian IX (8 April 181829 January 1906) was King of Denmark from 1863 until his death in 1906. From 1863 to 1864, he was concurrently Duke of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg.

A younger son of Frederick William, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein ...

and a formal dinner hosted by Swenson. He traveled through the contentious area of Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; da, Slesvig-Holsten; nds, Sleswig-Holsteen; frr, Slaswik-Holstiinj) is the northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Sc ...

and the site of the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armies of the Sevent ...

.

Nelson traveled home via England and happened to be in the visitors' gallery in the British parliament on October 17 when Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

convened an extraordinary session to debate the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

.

1900–1902 reelection campaign

Owing, once again, to his being elected by the state legislature, Nelson's campaign for reelection in 1902 started with the Minnesota state legislature elections of 1900. His strategy was to align himself with celebrated national leaders, especiallyTheodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

and Robert M. La Follette Sr.

Robert Marion "Fighting Bob" La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th Governor of Wisconsin. A Republican for most of his ...

, as they swung through the state campaigning for William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in t ...

. Nelson was known more for thoroughness than charisma in his campaigns, but contributed significantly to the Republican success that year. Nelson's son Henry Knute Nelson was elected to the Minnesota state legislature that year.

Nelson's reelection to a second Senate term was assured for all practical purposes. The campaign continued into 1902, when Nelson made a name for himself by commandeering a handcar

A handcar (also known as a pump trolley, pump car, rail push trolley, push-trolley, jigger, Kalamazoo, velocipede, or draisine) is a railroad car powered by its passengers, or by people pushing the car from behind. It is mostly used as a railway ...

when his train broke down east of Hibbing, Minnesota

Hibbing is a city in Saint Louis County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 16,214 at the 2020 census. The city was built on mining the rich iron ore of the Mesabi Iron Range and still relies on that industrial activity today. At th ...

. He made his own way to Wolf Junction, Minnesota at a brisk pace.

Until that point, Nelson's political career was largely based on the issues of an unfolding economic frontier, with land development, immigration, and Gilded Age dynamics. With the birth of the Progressive Era, the winds of reform started blowing more from the east than the west, and urban issues came more to the forefront. As a result, Nelson had to reinvent his political strategy.

In the crosswinds of the political movements of the time, Nelson chose a largely "moderate progressive" profile, accepting government intervention on some issues (such as antitrust matters) but opposing anything that smacked of socialism. He eased up on patronage as a political tool and focused instead on helping his constituents in matters small and large, often invoking the image of himself as a "drayhorse"—a hard-working, persistent advocate for the things and people he believed in.

Territories and statehood

In the Senate, Nelson was involved in creating theDepartment of Commerce and Labor

The United States Department of Commerce and Labor was a short-lived Cabinet department of the United States government, which was concerned with fostering and supervising big business.

Origins and establishment

Calls in the United States for ...

and the 1898 passage of the Nelson Bankruptcy Act, and served on the Overman Committee from 1918 to 1919. Serving from 1895 to 1923, he was a senator from the 54th through the 67th congresses. He was an active senator until his death in 1923 en route by train from Washington, D.C., to his hometown of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, where he was buried.

See also

* Knute Nelson Memorial Park * List of United States senators born outside the United States *List of United States Congress members who died in office (1900–49)

There are several lists of United States Congress members who died in office. These include:

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

* List of United States Congress members who died in office (1900–1949)

* List ...

* List of U.S. state governors born outside the United States

References

Minnesota Legislators Past and Present

and hi

gubernatorial records

are available for research use at th

Minnesota Historical Society.

* *

External links

Knute Nelson in MNopedia, the Minnesota Encyclopedia

{{DEFAULTSORT:Nelson, Knute 1843 births 1923 deaths People from Voss Norwegian emigrants to the United States Wisconsin Democrats Wisconsin Republicans Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Minnesota Republican Party United States senators from Minnesota Republican Party governors of Minnesota Governors of Minnesota Members of the Wisconsin State Assembly Minnesota state senators People from Alexandria, Minnesota Politicians from Madison, Wisconsin Lawyers from Madison, Wisconsin People from Palmyra, Wisconsin People from Koshkonong, Wisconsin 19th-century American lawyers American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law People of Wisconsin in the American Civil War