Kingdom of Two Sicilies on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies ( it, Regno delle Due Sicilie) was a kingdom in

During the reign of

During the reign of

Only with the

Only with the

The

The  The

The  In 1836 the Kingdom was struck by a

In 1836 the Kingdom was struck by a

The Kingdom of Two Sicilies, in the course of 1848–1849, had been able to suppress the revolution and the attempt of Sicilian secession with their own forces, hired Swiss guards included. The war declared on Austria in April 1848, under pressure of public sentiment, had been an event on paper only.

The Kingdom of Two Sicilies, in the course of 1848–1849, had been able to suppress the revolution and the attempt of Sicilian secession with their own forces, hired Swiss guards included. The war declared on Austria in April 1848, under pressure of public sentiment, had been an event on paper only.

In 1849 King Ferdinand II was 39 years old. He had begun as a reformer; the early death of his wife (1836), the frequency of political unrest, the extent and range of political expectations on the side of various groups that made up public opinion, had caused him to pursue a cautious, yet authoritarian policy aiming at the prevention of the occurrence of yet another rebellion. Over half of the delegates elected to parliament in the liberal atmosphere of 1848 were arrested or fled the country. The administration, in their treatment of political prisoners, in their observation of 'suspicious elements', violated the rights of the individual guaranteed by the constitution. Conditions were so bad that they caused international attention; in 1856

In 1849 King Ferdinand II was 39 years old. He had begun as a reformer; the early death of his wife (1836), the frequency of political unrest, the extent and range of political expectations on the side of various groups that made up public opinion, had caused him to pursue a cautious, yet authoritarian policy aiming at the prevention of the occurrence of yet another rebellion. Over half of the delegates elected to parliament in the liberal atmosphere of 1848 were arrested or fled the country. The administration, in their treatment of political prisoners, in their observation of 'suspicious elements', violated the rights of the individual guaranteed by the constitution. Conditions were so bad that they caused international attention; in 1856  Until 1849, the political movement among the bourgeoisie, at times revolutionary, had been Neapolitan respectively Sicilian rather than Italian in its tendency; Sicily in 1848-1849 had striven for a higher degree of independence from

Until 1849, the political movement among the bourgeoisie, at times revolutionary, had been Neapolitan respectively Sicilian rather than Italian in its tendency; Sicily in 1848-1849 had striven for a higher degree of independence from

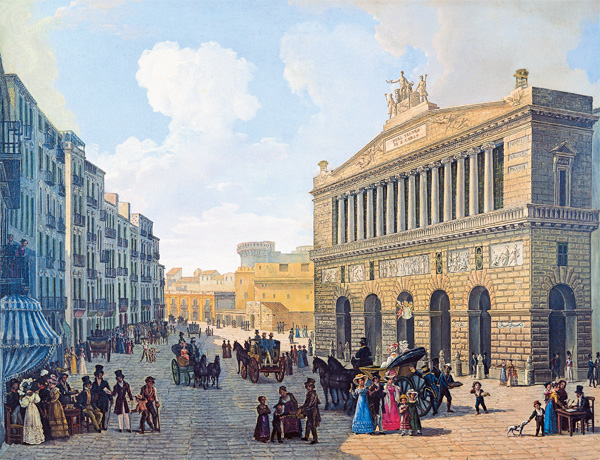

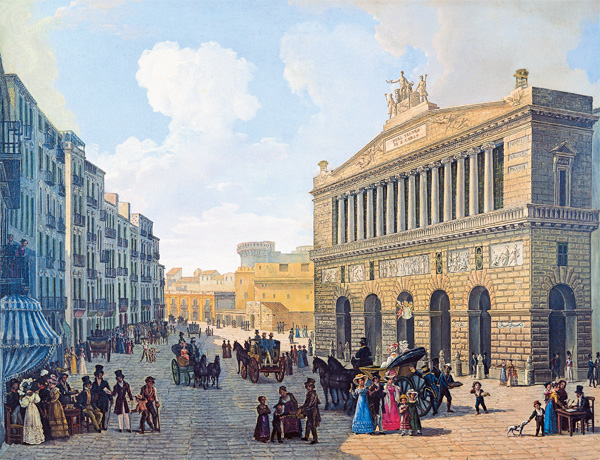

The Teatro Reale di San Carlo commissioned by the Bourbon King

The Teatro Reale di San Carlo commissioned by the Bourbon King  On 13 February 1816 a fire broke out during a dress-rehearsal for a ballet performance and quickly spread to destroy a part of building. On the orders of King Ferdinand I, who used the services of Antonio Niccolini, to rebuild the opera house within ten months as a traditional horseshoe-shaped auditorium with 1,444 seats, and a proscenium, 33.5m wide and 30m high. The stage was 34.5m deep. Niccolini embellished in the inner of the bas-relief depicting "Time and the Hour".

On 13 February 1816 a fire broke out during a dress-rehearsal for a ballet performance and quickly spread to destroy a part of building. On the orders of King Ferdinand I, who used the services of Antonio Niccolini, to rebuild the opera house within ten months as a traditional horseshoe-shaped auditorium with 1,444 seats, and a proscenium, 33.5m wide and 30m high. The stage was 34.5m deep. Niccolini embellished in the inner of the bas-relief depicting "Time and the Hour".

A major problem in the Kingdom was the distribution of land property - most of it concentrated in the hands of a few families, the

A major problem in the Kingdom was the distribution of land property - most of it concentrated in the hands of a few families, the

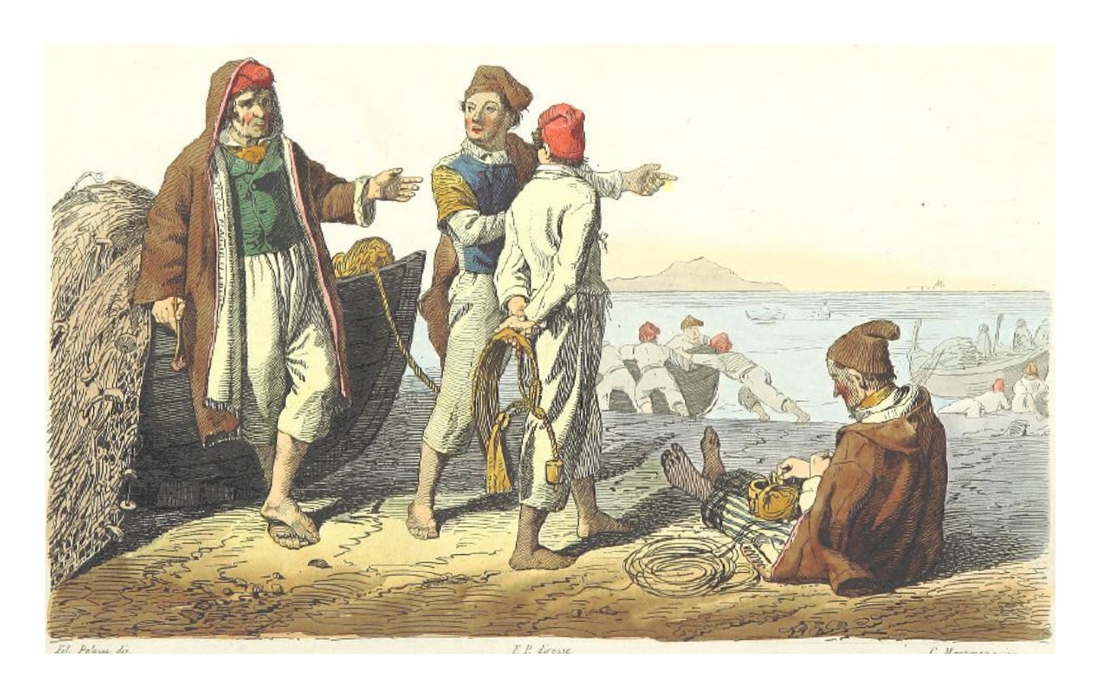

With all of its major cities boasting successful ports, transport and trade in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was most efficiently conducted by sea. The kingdom possessed the largest merchant fleet in the Mediterranean. Urban road conditions were to the best European standards; by 1839, the main streets of Naples were gas-lit. Efforts were made to tackle the tough mountainous terrain; Ferdinand II built the cliff-top road along the Sorrentine peninsula. Road conditions in the interior and hinterland areas of the kingdom made internal trade difficult. The first railways and iron-suspension bridges in Italy were developed in the south, as was the first overland electric telegraph cable.

With all of its major cities boasting successful ports, transport and trade in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was most efficiently conducted by sea. The kingdom possessed the largest merchant fleet in the Mediterranean. Urban road conditions were to the best European standards; by 1839, the main streets of Naples were gas-lit. Efforts were made to tackle the tough mountainous terrain; Ferdinand II built the cliff-top road along the Sorrentine peninsula. Road conditions in the interior and hinterland areas of the kingdom made internal trade difficult. The first railways and iron-suspension bridges in Italy were developed in the south, as was the first overland electric telegraph cable.

The peninsula was divided into fifteen departments and Sicily was divided into seven departments. The island itself had a special administrative status, with its base at Palermo. In 1860, when the Two Sicilies were conquered by the

The peninsula was divided into fifteen departments and Sicily was divided into seven departments. The island itself had a special administrative status, with its base at Palermo. In 1860, when the Two Sicilies were conquered by the  Province of Naples -

Province of Naples -

Principato Ultra -

Principato Ultra -

Terra di Bari -

Terra di Bari -  Terra d'Otranto -

Terra d'Otranto -  Calabria Citra -

Calabria Citra -  Calabria Ultra I - Reggio

*

Calabria Ultra I - Reggio

*  Calabria Ultra II -

Calabria Ultra II -  Contado di Molise -

Contado di Molise -

Abruzzo Ultra I -

Abruzzo Ultra I -  Abruzzo Ultra II - Aquila

Insular departments

*

Abruzzo Ultra II - Aquila

Insular departments

*  Province of Caltanissetta -

Province of Caltanissetta -  Province of Catania -

Province of Catania -  Province of Girgenti - Girgenti

*

Province of Girgenti - Girgenti

*  Province of Messina -

Province of Messina -  Province of Noto -

Province of Noto -  Province of Palermo -

Province of Palermo -  Province of Trapani -

Province of Trapani -

File:Ferdinand i twosicilies.jpg, Ferdinand I, 1816–1825

File:Francisco I de las Dos Sicilias (por Vicente López Portaña. 1829. Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando).jpg,

In 1860–61 with influence from Great Britain and

File:Flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1738).svg, 1816–1848; 1849–1860 flag

File:Flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1848).svg, 1848–1849 flag

File:Flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1860).svg, 1860–1861 flag

File:Royal Standard of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1829).svg, Royal standard 1829–1861

Brigantino – Il portale del Sud

a massive Italian-language site dedicated to the history, culture and arts of southern Italy

Casa Editoriale Il Giglio

an Italian publisher that focuses on history, culture and the arts in the Two Sicilies

La Voce di Megaride

a website by Marina Salvadore dedicated to Napoli and Southern Italy

Associazione culturale "Amici di Angelo Manna"

dedicated to the work of Angelo Manna, historian, poet and deputy

professor; includes many articles about southern Italy's culture and history

Regalis

a website on Italian dynastic history, with sections on the House of the Two Sicilies {{DEFAULTSORT:Kingdom of the Two Sicilies 19th century in Sicily History of Campania History of Calabria History of Apulia History of Basilicata Italian unification States and territories established in 1816 1816 establishments in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies 1861 disestablishments in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

Southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the pe ...

from 1816 to 1860. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and size in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

before Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

, comprising Sicily and all of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

, which covered most of the area of today's Mezzogiorno

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the pe ...

.

The kingdom was formed when the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily ( la, Regnum Siciliae; it, Regno di Sicilia; scn, Regnu di Sicilia) was a state that existed in the south of the Italian Peninsula and for a time the region of Ifriqiya from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 un ...

merged with the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

, which was officially also known as the Kingdom of Sicily. Since both kingdoms were named Sicily, they were collectively known as the "Two Sicilies" (''Utraque Sicilia'', literally "both Sicilies"), and the unified kingdom adopted this name. The king of the Two Sicilies was overthrown by Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1860, after which the people voted in a plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

to join the Savoyard Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia,The name of the state was originally Latin: , or when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is , in French , in Sardinian , and in Piedmontese . also referred to as the Kingdom of Savoy-S ...

. The annexation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies completed the first phase of Italian unification, and the new Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

was proclaimed in 1861.

The Two Sicilies were heavily agricultural, like the other Italian states.

Name

The name "Two Sicilies" originated from the partition of the medievalKingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily ( la, Regnum Siciliae; it, Regno di Sicilia; scn, Regnu di Sicilia) was a state that existed in the south of the Italian Peninsula and for a time the region of Ifriqiya from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 un ...

. Until 1285, the island of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and the Mezzogiorno

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the pe ...

were constituent parts of the Kingdom of Sicily. As a result of the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302), the King of Sicily lost the Island of Sicily (also called Trinacria) to the Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon ( , ) an, Corona d'Aragón ; ca, Corona d'Aragó, , , ; es, Corona de Aragón ; la, Corona Aragonum . was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of ...

, but remained ruler over the peninsular part of the realm. Although his territory became known unofficially as the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

, he and his successors never gave up the title "King of Sicily" and still officially referred to their realm as the "Kingdom of Sicily". At the same time, the Aragonese rulers of the Island of Sicily also called their realm the "Kingdom of Sicily". Thus, there were two kingdoms called "Sicily": hence, the Two Sicilies. This is readopted by Two Sicilies national football team, an Italian football club since December 2008.

Background

Origins of the two kingdoms

In 1130 the Norman kingRoger II

Roger II ( it, Ruggero II; 22 December 1095 – 26 February 1154) was King of Sicily and Africa, son of Roger I of Sicily and successor to his brother Simon. He began his rule as Count of Sicily in 1105, became Duke of Apulia and Calabria in ...

formed the Kingdom of Sicily by combining the County of Sicily

The County of Sicily, also known as County of Sicily and Calabria, was a Norman state comprising the islands of Sicily and Malta and part of Calabria from 1071 until 1130. The county began to form during the Christian reconquest of Sicily (106 ...

with the southern part of the Italian Peninsula (then known as the Duchy of Apulia and Calabria) as well as with the Maltese Islands. The capital of this kingdom was Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The city is noted for its ...

, which is on the island of Sicily.

During the reign of

During the reign of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

of Anjou Anjou may refer to:

Geography and titles France

*County of Anjou, a historical county in France and predecessor of the Duchy of Anjou

**Count of Anjou, title of nobility

*Duchy of Anjou, a historical duchy and later a province of France

**Duke ...

(1266–1285), the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302) split the kingdom. Charles, who was of French origin, lost the island of Sicily to the House of Barcelona

The House of Barcelona was a medieval dynasty that ruled the County of Barcelona continuously from 878 and the Crown of Aragon from 1137 (as kings from 1162) until 1410. They descend from the Bellonids, the descendants of Wifred the Hairy. Th ...

, who were from Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

and Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the no ...

. Charles remained king of the peninsular region, which became informally known as the Kingdom of Naples. Officially Charles never gave up the title of "The Kingdom of Sicily"; thus there existed two separate kingdoms calling themselves "Sicily".

Aragonese and Spanish direct rule

Only with the

Only with the Peace of Caltabellotta

The Peace of Caltabellotta, signed on 31 August 1302, was the last of a series of treaties, including those of Tarascon and Anagni, designed to end the conflict between the Houses of Anjou and Barcelona for ascendancy in the Mediterranean and esp ...

(1302), sponsored by Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII ( la, Bonifatius PP. VIII; born Benedetto Caetani, c. 1230 – 11 October 1303) was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 to his death in 1303. The Caetani family was of baronial ...

, did the two kings of "Sicily" recognize each other's legitimacy; the island kingdom then became the " Kingdom of Trinacria" in official contexts, though the populace still called it Sicily. In 1442, Alfonso V of Aragon

Alfonso the Magnanimous (139627 June 1458) was King of Aragon and King of Sicily (as Alfonso V) and the ruler of the Crown of Aragon from 1416 and King of Naples (as Alfonso I) from 1442 until his death. He was involved with struggles to the ...

, king of insular Sicily, conquered Naples and became king of both.

Alfonso V called his kingdom in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

"''Regnum Utriusque Siciliæ"'', meaning "Kingdom of both Sicilies". At the death of Alfonso in 1458, the kingdom again became divided between his brother John II of Aragon

John II ( Spanish: ''Juan II'', Catalan: ''Joan II'', Aragonese: ''Chuan II'' and eu, Joanes II; 29 June 1398 – 20 January 1479), called the Great (''el Gran'') or the Faithless (''el Sense Fe''), was King of Aragon from 1458 until his death ...

, who kept the island of Sicily, and his illegitimate son Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "protection", "peace" (PIE "to love, to make peace") or alternatively "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "co ...

, who became King of Naples. In 1501, King Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia fro ...

, the son of John II, agreed to help Louis XII of France

Louis XII (27 June 14621 January 1515), was King of France from 1498 to 1515 and King of Naples from 1501 to 1504. The son of Charles, Duke of Orléans, and Maria of Cleves, he succeeded his 2nd cousin once removed and brother in law at the time ...

conquer Naples and Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

. After Frederick IV was forced to abdicate, the French took power, and Louis reigned as Louis III of Naples for three years. Negotiations to divide the region failed, and the French soon began unsuccessful attempts to force the Spanish out of the peninsula.

After the French lost the Battle of Garigliano (1503), they left the kingdom. Ferdinand II then re-united the two areas into one kingdom. From 1516, when Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) fr ...

, became the first king of Spain

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

, both Naples and Sicily came under direct Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

rule and after that navigated between Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

and Spanish Rule In 1530 Charles V granted the islands of Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and Gozo

Gozo (, ), Maltese: ''Għawdex'' () and in antiquity known as Gaulos ( xpu, 𐤂𐤅𐤋, ; grc, Γαῦλος, Gaúlos), is an island in the Maltese archipelago in the Mediterranean Sea. The island is part of the Republic of Malta. After ...

, which had been part of the Kingdom of Sicily, to the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

(thereafter known as the Order of Malta

The Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), officially the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta ( it, Sovrano Militare Ordine Ospedaliero di San Giovanni di Gerusalemme, di Rodi e di Malta; ...

). At the end of the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

, the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne ...

in 1713 granted Sicily to the Duke of Savoy

The titles of count, then of duke of Savoy are titles of nobility attached to the historical territory of Savoy. Since its creation, in the 11th century, the county was held by the House of Savoy. The County of Savoy was elevated to a duchy at ...

, until the Treaty of Rastatt

The Treaty of Rastatt was a peace treaty between France and Austria that was concluded on 7 March 1714 in the Baden city of Rastatt to end the War of the Spanish Succession between both countries. The treaty followed the Treaty of Utrecht of 11 A ...

in 1714 left Naples to the Emperor Charles VI

Charles VI (german: Karl; la, Carolus; 1 October 1685 – 20 October 1740) was Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of the Austrian Habsburg monarchy from 1711 until his death, succeeding his elder brother, Joseph I. He unsuccessfully claimed the thron ...

. In the 1720 Treaty of The Hague, the Emperor and Savoy exchanged Sicily for Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

, thus reuniting Naples and Sicily.

History

1816–1848

The

The Treaty of Casalanza

The Treaty of Casalanza, which ended the Neapolitan War, was signed on 20 May 1815 between the pro- Napoleon Kingdom of Naples on the one hand and the Austrian Empire, as well as the Great Britain, on the other. The signature occurred in a patricia ...

restored Ferdinand IV of Bourbon to the throne of Naples and the island of Sicily (where the constitution of 1812 virtually had disempowered him) was returned to him. In 1816 he annulled the constitution and Sicily became fully reintegrated into the new state, which was now officially called the Regno delle Due Sicilie (Kingdom of Two Sicilies). Ferdinand IV became Ferdinand I.

A number of accomplishments under the administration of Kings Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the m ...

and Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also , ; it, Gioacchino Murati; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French military commander and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the ...

, such as the Code Civil, the penal and commercial code, were kept (and extended to Sicily). In the mainland parts of the Kingdom, the power and influence of both nobility and clergy had been greatly reduced, though at the expense of law and order. Brigandage

Brigandage is the life and practice of highway robbery and plunder. It is practiced by a brigand, a person who usually lives in a gang and lives by pillage and robbery.Oxford English Dictionary second edition, 1989. "Brigand.2" first recorded u ...

and the forceful occupation of lands were problems the restored Kingdom inherited from its predecessors.

The

The Vienna Congress

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

had granted Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

the right to station troops in the kingdom, and Austria, as well as Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

and Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

, insisted that no written constitution was to be granted to the kingdom. In October 1815, Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also , ; it, Gioacchino Murati; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French military commander and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the ...

landed in Calabria

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, in an attempt to regain his kingdom. The government responded to acts of collaboration or of terrorism with severe repression and by June 1816 Murat's attempt had failed and the situation was under government control. However, the Neapolitan administration had changed from conciliatory to reactionary policies. The French novelist Henri de Stendhal, who visited Naples in 1817, called the kingdom "an absurd monarchy in the style of Philip II".

As open political activity was suppressed, liberals organized themselves in secret societies, such as the Carbonari

The Carbonari () was an informal network of secret revolutionary societies active in Italy from about 1800 to 1831. The Italian Carbonari may have further influenced other revolutionary groups in France, Portugal, Spain, Brazil, Uruguay and Ru ...

, an organization whose origins date back into the French period and which had been outlawed in 1816. In 1820 a revolution planned by Carbonari and their supporters, aimed at obtaining a written constitution (the Spanish constitution of 1812), did not work out as planned. Nevertheless, King Ferdinand felt compelled to grant the constitution sought by the liberals (13 July). That same month, a revolution broke out in Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The city is noted for its ...

, Sicily, but was quickly suppressed. Rebels from Naples occupied Benevento

Benevento (, , ; la, Beneventum) is a city and '' comune'' of Campania, Italy, capital of the province of Benevento, northeast of Naples. It is situated on a hill above sea level at the confluence of the Calore Irpino (or Beneventano) and the ...

and Pontecorvo, two enclaves belonging to the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

. At the Congress of Troppau The Congress of Troppau was a conference of the Quintuple Alliance to discuss means of suppressing the revolution in Naples of July 1820, and at which the Troppau Protocol was signed on 19 November 1820.

The Congress met on 20 October 1820 in Tropp ...

(Nov. 19th), the Holy Alliance

The Holy Alliance (german: Heilige Allianz; russian: Священный союз, ''Svyashchennyy soyuz''; also called the Grand Alliance) was a coalition linking the monarchist great powers of Austria, Prussia, and Russia. It was created after ...

( Metternich being the driving force) decided to intervene. On 23 February 1821, in front of 50,000 Austrian troops paraded outside his capital, King Ferdinand cancelled the constitution. An attempt at Neapolitan resistance to the Austrians by regular forces under General Guglielmo Pepe

Guglielmo Pepe (13 February 1783 – 8 August 1855) was an Italian general and patriot. He was brother to Florestano Pepe and cousin to Gabriele Pepe. He was married to Mary Ann Coventry, a Scottish woman who was the widow of John Borthw ...

, as well as by irregular rebel forces (Carbonari), was smashed and on 24 March 1821 Austrian forces entered the city of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

.

Political repression then only intensified. Lawlessness in the countryside was aggravated by the problem of administrative corruption. A coup attempted in 1828 and aimed at forcing the promulgation of a constitution was suppressed by Neapolitan troops (the Austrian troops had left the previous year). King Francis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe-Lau ...

(1825-1830) died after having visited Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, where he witnessed the 1830 revolution. In 1829 he had created the Royal Order of Merit (Royal Order of Francis I. of the Two Sicilies). His successor Ferdinand II declared a political amnesty and undertook steps to stimulate the economy, including reduction of taxation. Eventually the city of Naples would be equipped with street lighting and in 1839 the railroad from Naples to Portici was put into operation, measures that were visible signs of progress. However, as to the railroad, the Church still objected to the construction of tunnels, because of their 'obscenity'.

In 1836 the Kingdom was struck by a

In 1836 the Kingdom was struck by a cholera epidemic

Seven cholera pandemics have occurred in the past 200 years, with the first pandemic originating in India in 1817. The seventh cholera pandemic is officially a current pandemic and has been ongoing since 1961, according to a World Health Organizat ...

which killed 65,000 in Sicily alone. In the following years the Neapolitan countryside saw sporadic local insurrections. In the 1840s, clandestine political pamphlets circulated, evading censorship. Moreover, in September 1847 an uprising saw insurrectionists crossing from mainland Calabria over to Sicily before government forces were able to suppress them. On 13 January 1848, an open rebellion

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

began in Palermo and demands were made for the reintroduction of the 1812 constitution. King Ferdinand II appointed a liberal prime minister, broke off diplomatic relations with Austria and even declared war on the latter (7 April). Although revolutionaries who had risen in several mainland cities outside Naples shortly after the Sicilians approved of the new measures (April 1848), Sicily continued with her revolution. Faced with these differing reactions to his moves, King Ferdinand, using the Swiss Guard, took the initiative and ordered the suppression of the revolution in Naples (15 May) and by July the mainland was again under royal control and by September, also Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in t ...

. Palermo, the revolutionaries' capital and last stronghold, fell to the government some months later on 15 May 1849.

1848–1861

The Kingdom of Two Sicilies, in the course of 1848–1849, had been able to suppress the revolution and the attempt of Sicilian secession with their own forces, hired Swiss guards included. The war declared on Austria in April 1848, under pressure of public sentiment, had been an event on paper only.

The Kingdom of Two Sicilies, in the course of 1848–1849, had been able to suppress the revolution and the attempt of Sicilian secession with their own forces, hired Swiss guards included. The war declared on Austria in April 1848, under pressure of public sentiment, had been an event on paper only.

In 1849 King Ferdinand II was 39 years old. He had begun as a reformer; the early death of his wife (1836), the frequency of political unrest, the extent and range of political expectations on the side of various groups that made up public opinion, had caused him to pursue a cautious, yet authoritarian policy aiming at the prevention of the occurrence of yet another rebellion. Over half of the delegates elected to parliament in the liberal atmosphere of 1848 were arrested or fled the country. The administration, in their treatment of political prisoners, in their observation of 'suspicious elements', violated the rights of the individual guaranteed by the constitution. Conditions were so bad that they caused international attention; in 1856

In 1849 King Ferdinand II was 39 years old. He had begun as a reformer; the early death of his wife (1836), the frequency of political unrest, the extent and range of political expectations on the side of various groups that made up public opinion, had caused him to pursue a cautious, yet authoritarian policy aiming at the prevention of the occurrence of yet another rebellion. Over half of the delegates elected to parliament in the liberal atmosphere of 1848 were arrested or fled the country. The administration, in their treatment of political prisoners, in their observation of 'suspicious elements', violated the rights of the individual guaranteed by the constitution. Conditions were so bad that they caused international attention; in 1856 Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

demanded the release of the political prisoners. When this was rejected, both countries broke off diplomatic relations. The Kingdom pursued an economic policy of protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulation ...

; the country's economy was mainly based on agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

, the cities, especially Naples – with over 400,000 inhabitants Italy's largest – "a center of consumption rather than of production" (Santore p. 163) and home to poverty most expressed by the masses of Lazzaroni

Lazzaroni () is the brand name related to several biscuits and bakery products manufactured by the Italian company D. Lazzaroni & C. Spa.

Lazzaroni is a well-known Italian brand thanks to products such as Amaretti di Saronno. Lazzaroni was the ...

, the poorest class.

After visiting Naples in 1850, Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-cons ...

began to support Neapolitan opponents of the Bourbon rulers: his "support" consisted of a couple of letters that he sent from Naples to the Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

in London, describing the "awful conditions" of the Kingdom of Southern Italy and claiming that "it is the negation of God erected to a system of government". Gladstone's letters provoked sensitive reactions in the whole of Europe and helped to cause its diplomatic isolation before the invasion

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing ...

and annexation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies by the Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia,The name of the state was originally Latin: , or when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is , in French , in Sardinian , and in Piedmontese . also referred to as the Kingdom of Savoy-S ...

, with the following foundation of modern Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. Administratively, Naples and Sicily remained separate units; in 1858 the Neapolitan Postal Service issued her first postage stamps; that of Sicily followed in 1859.

Until 1849, the political movement among the bourgeoisie, at times revolutionary, had been Neapolitan respectively Sicilian rather than Italian in its tendency; Sicily in 1848-1849 had striven for a higher degree of independence from

Until 1849, the political movement among the bourgeoisie, at times revolutionary, had been Neapolitan respectively Sicilian rather than Italian in its tendency; Sicily in 1848-1849 had striven for a higher degree of independence from Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

rather than for a unified Italy. As public sentiment for Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

was rather low in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the country did not feature as an object of acquisition in the earlier plans of Piemont-Sardinia's prime minister Cavour. Only when Austria was defeated

Defeated may refer to:

* "Defeated" (Breaking Benjamin song)

* "Defeated" (Anastacia song)

*"Defeated", a song by Snoop Dogg from the album ''Bible of Love''

*Defeated, Tennessee, an unincorporated community

*''The Defeated

''The Defeated'', al ...

in 1859 and the unification of Northern Italy (except Venetia) was accomplished in 1860, did Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, pa ...

, at the head of the Expedition of the Thousand, launch his invasion

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing ...

of Sicily, with the connivance of Cavour (once in Sicily, many rallied to his colours); after a successful campaign in Sicily, he crossed over to the mainland and won the battle of the Volturno with half of his army being local volunteers. King Francis II (since 1859) withdrew to the fortified port of Gaeta

Gaeta (; lat, Cāiēta; Southern Laziale: ''Gaieta'') is a city in the province of Latina, in Lazio, Southern Italy. Set on a promontory stretching towards the Gulf of Gaeta, it is from Rome and from Naples.

The town has played a consp ...

, where he surrendered and abdicated in February 1861 after the Siege of Gaeta. At the encounter of Teano, Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, pat ...

met King Victor Emmanuel, transferring to him the conquered kingdom, the Two Sicilies were annexed into the Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia,The name of the state was originally Latin: , or when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is , in French , in Sardinian , and in Piedmontese . also referred to as the Kingdom of Savoy-S ...

, which became the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

in 1861. What used to be the Kingdom of Two Sicilies became Italy's Mezzogiorno

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the pe ...

.

Arts patronage

The Teatro Reale di San Carlo commissioned by the Bourbon King

The Teatro Reale di San Carlo commissioned by the Bourbon King Charles VII of Naples

it, Carlo Sebastiano di Borbone e Farnese

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Philip V of Spain

, mother = Elisabeth Farnese

, birth_date = 20 January 1716

, birth_place = Royal Alcazar of Madrid, Spain

, death_da ...

who wanted to grant Naples a new and larger theatre to replace the old, dilapidated, and too-small Teatro San Bartolomeo of 1621. Which had served the city well, especially after Scarlatti had moved there in 1682 and had begun to create an important opera centre which existed well into the 1700s. Thus, the San Carlo was inaugurated on 4 November 1737, the king's name day

In Christianity, a name day is a tradition in many countries of Europe and the Americas, among other parts of Christendom. It consists of celebrating a day of the year that is associated with one's baptismal name, which is normatively that of a ...

, with the performance of Domenico Sarro

Domenico Natale Sarro, also Sarri (24 December 1679 – 25 January 1744) was an Italian composer.

Born in Trani, Apulia, he studied at the Neapolitan conservatory of S. Onofrio. He composed extensively in the early 18th century. His opera ''Di ...

's opera ''Achille in Sciro'' and much admired for its architecture the San Carlo was now the biggest opera house in the world.Beauvert 1985, p. 44Stendhal

Marie-Henri Beyle (; 23 January 1783 – 23 March 1842), better known by his pen name Stendhal (, ; ), was a 19th-century French writer. Best known for the novels ''Le Rouge et le Noir'' ('' The Red and the Black'', 1830) and ''La Chartreuse de ...

attended the second night of the inauguration and wrote: "There is nothing in all Europe, I won't say comparable to this theatre, but which gives the slightest idea of what it is like..., it dazzles the eyes, it enraptures the soul...".

From 1815 to 1822, Gioachino Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer who gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces, and some sacred music. He set new standards ...

was the house composer and artistic director of the royal opera houses, including the San Carlo. During this period he wrote ten operas which were ''Elisabetta, regina d'Inghilterra

''Elisabetta, regina d'Inghilterra'' (; ''Elizabeth, Queen of England'') is a ''dramma per musica'' or opera in two acts by Gioachino Rossini to a libretto by Giovanni Schmidt, from the play ''Il paggio di Leicester'' (''Leicester's Page'') by Ca ...

'' (1815), ''La gazzetta

''La gazzetta, ossia Il matrimonio per concorso'' (''The Newspaper, or The Marriage Contest)'' is an opera buffa by Gioachino Rossini. The libretto was by Giuseppe Palomba after Carlo Goldoni's play ''Il matrimonio per concorso'' of 1763. The o ...

'', '' Otello, ossia il Moro di Venezia'' (1816), '' Armida'' (1817), '' Mosè in Egitto'', '' Ricciardo e Zoraide'' (1818), ''Ermione

''Ermione'' (1819) is a tragic opera (azione tragica) in two acts by Gioachino Rossini to an Italian libretto by Andrea Leone Tottola, based on the play ''Andromaque'' by Jean Racine.

Performance history

19th century

''Ermione'' was first ...

'', ''Bianca e Falliero

''Bianca e Falliero, ossia Il consiglio dei tre'' (English: ''Bianca and Falliero, or The Counsel of Three'') is a two-act operatic ''melodramma'' by Gioachino Rossini to an Italian libretto by Felice Romani. The libretto was based on Antoine-Vi ...

'', ''Eduardo e Cristina

''Eduardo e Cristina'' () is an operatic ''dramma'' in two acts by Gioachino Rossini to an Italian libretto originally written by Giovanni Schmidt for ''Odoardo e Cristina'' (1810), an opera by Stefano Pavesi, and adapted for Rossini by Andrea ...

'', '' La donna del lago'' (1819), '' Maometto II'' (1820), and '' Zelmira'' (1822), many premiered at the San Carlo. An offer in 1822 from Domenico Barbaja, the impresario of the San Carlo, which followed the composer's ninth opera, led to Gaetano Donizetti

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti (29 November 1797 – 8 April 1848) was an Italian composer, best known for his almost 70 operas. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, he was a leading composer of the '' bel canto'' opera style ...

's move to Naples and his residency there which lasted until the production of ''Caterina Cornaro

Catherine Cornaro ( el, Αικατερίνη Κορνάρο, vec, Catarina Corner) (25 November 1454 – 10 July 1510) was the last monarch of the Kingdom of Cyprus, also holding the titles of the Queen of Jerusalem and Armenia. She was queen ...

'' in January 1844.Black 1982, p. 1 In all, Naples presented 51 of Donizetti's operas. Also Vincenzo Bellini's first professionally staged opera had its first performance

''First Performance'' is a Canadian dramatic television series which aired on CBC Television from 1956 to 1958.

Premise

These short series of television plays were produced as a promotion for Canada Savings Bonds.

Scheduling

The first season ...

at the Teatro di San Carlo

The Real Teatro di San Carlo ("Royal Theatre of Saint Charles"), as originally named by the Bourbon monarchy but today known simply as the Teatro (di) San Carlo, is an opera house in Naples, Italy, connected to the Royal Palace and adjacent ...

in Naples on 30 May 1826.Weinstock 1971, pp. 30—34

Historical population

The kingdom had a large population, its capital Naples being the biggest city in Italy, at least three times as large as any other contemporary Italian state. At its peak, the kingdom had amilitary

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

100,000 soldiers strong, and a large bureaucracy

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

. Naples was the largest city in the kingdom and the third largest city in Europe. The second largest city, Palermo, was the third largest in Italy. In the 1800s, the kingdom experienced large population growth, rising from approximately five to seven million. It held approximately 36% of Italy's population around 1850.

Because the kingdom did not establish a statistical department until after 1848, most population statistics before that year are estimates and censuses that were thought by contemporaries to be inaccurate.

Military

The Army of the Two Sicilies was the land forces of the Kingdom, it was created by the settlement of the Bourbon dynasty in southern Italy following the events of the War of the Polish Succession. The army collapsed during the Expedition of the Thousand. The Real Marina was the naval forces of the Kingdom. It was the most important of the pre-unification Italian navies.Economy

A major problem in the Kingdom was the distribution of land property - most of it concentrated in the hands of a few families, the

A major problem in the Kingdom was the distribution of land property - most of it concentrated in the hands of a few families, the landed oligarchy

Landed may refer to:

* ''Landed'' (album), a 1975 album by Can

* "Landed", a song by Ben Folds from ''Songs for Silverman''

* "Landed", a song by Drake from ''Dark Lane Demo Tapes''

* Landed gentry, a largely historical privileged British social ...

. The villages housed a large rural proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

, desperately poor and dependent on the landlords for work. The Kingdom's few cities had little industry, thus not providing the outlet excess rural population found in northern Italy, France or Germany. The figures above show that the population of the countryside rose at a faster rate than that of the city of Naples herself, a rather odd phenomenon in a time when much of Europe experienced the Industrial Revolution.

While underdeveloped compared to Northwest Italy

Northwest Italy ( it, Italia nord-occidentale or just ) is one of the five official statistical regions of Italy used by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), a first level NUTS region and a European Parliament constituency. Northwes ...

and contemporary Western European countries at the time of unification in 1861, the average wage of the Two Sicilies was actually higher than Central Italy

Central Italy ( it, Italia centrale or just ) is one of the five official statistical regions of Italy used by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), a first-level NUTS region, and a European Parliament constituency.

Regions

Central I ...

and on par with Northeast Italy

Northeast Italy ( it, Italia nord-orientale or just ) is one of the five official statistical regions of Italy used by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), a first level NUTS region and a European Parliament constituency. Northeast ...

. The island of Sicily, in particular, was richer than the mainland part of the kingdom and its wages were very close to the northwest's. The Divergence increased massively after unification however, due to the complete collapse of the South's economy.

Agriculture

As registered in the 1827 census, for theNeapolitan

Neapolitan means of or pertaining to Naples, a city in Italy; or to:

Geography and history

* Province of Naples, a province in the Campania region of southern Italy that includes the city

* Duchy of Naples, in existence during the Early and Hig ...

(continental) part of the kingdom, 1,475,314 of the male population were listed as husbandmen which traditionally consisted of three classes the ''Borgesi'' (or yeomanry), the ''Inquilani'' (or small-farmers) and the ''Contadini'' (or peasantry), along with 65,225 listed as shepherds

A shepherd or sheepherder is a person who tends, herds, feeds, or guards flocks of sheep. ''Shepherd'' derives from Old English ''sceaphierde (''sceap'' 'sheep' + ''hierde'' 'herder'). ''Shepherding is one of the world's oldest occupations, i ...

. Wheat, wine, olive oil and cotton were the chief products with an annual production, as recorded in 1844, of 67 million liters of olive oil

Olive oil is a liquid fat obtained from olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea''; family Oleaceae), a traditional tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin, produced by pressing whole olives and extracting the oil. It is commonly used in cooking: ...

largely produced in Apulia

it, Pugliese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographic ...

and Calabria and loaded for export at Gallipoli

The Gallipoli peninsula (; tr, Gelibolu Yarımadası; grc, Χερσόνησος της Καλλίπολης, ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles s ...

along with 191 million liters of wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink typically made from Fermentation in winemaking, fermented grapes. Yeast in winemaking, Yeast consumes the sugar in the grapes and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Different ...

that were for the most part consumed domestically. On the island of Sicily, in 1839, due to less arable lands, the output was much smaller than on the mainland yet approximately 115,000 acres of vineyard

A vineyard (; also ) is a plantation of grape-bearing vines, grown mainly for winemaking, but also raisins, table grapes and non-alcoholic grape juice. The science, practice and study of vineyard production is known as viticulture. Vineyard ...

s and about 260,000 acres of orchard

An orchard is an intentional plantation of trees or shrubs that is maintained for food production. Orchards comprise fruit- or nut-producing trees which are generally grown for commercial production. Orchards are also sometimes a feature of ...

s, mainly fig, orange and citrus, were cultivated.

Industry

Industry was the largest source of income if compared with the other preunitarian states. One of the most important industrial complexes in the kingdom was theshipyard

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance ...

of Castellammare di Stabia

Castellammare di Stabia (; nap, Castiellammare 'e Stabbia) is a '' comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Naples, Campania region, in southern Italy. It is situated on the Bay of Naples about southeast of Naples, on the route to Sorrento.

History ...

, which employed 1800 workers. The engineering factory of Pietrarsa

The National Railway Museum of Pietrarsa ( it, Museo Nazionale Ferroviario di Pietrarsa, italic=no) lies beside the Naples–Portici railway, between the city of Naples and the towns of Portici and San Giorgio a Cremano. Pietrarsa is an area a ...

was the largest industrial plant in the Italian peninsula, producing tools, cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

s, rails, locomotive

A locomotive or engine is a rail transport vehicle that provides the motive power for a train. If a locomotive is capable of carrying a payload, it is usually rather referred to as a multiple unit, motor coach, railcar or power car; the ...

s. The complex also included a school for train drivers, and naval engineers and, thanks to this school, the kingdom was able to replace the English personnel who had been necessary until then. The first steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. Steamboats sometimes use the ship prefix, prefix designation SS, S.S. or S/S ...

with screw propulsion known in the Mediterranean Sea was the "Giglio delle Onde", with mail delivery and passenger transport purposes after 1847.

In Calabria, the Fonderia Ferdinandea was a large foundry

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

where cast iron was produced. The Reali ferriere ed Officine di Mongiana

Reali ferriere ed Officine di Mongiana or Villaggio Siderurgico di Mongiana (in English: ''Mongiana Royal Iron Foundry and Works'' or ''The Iron & Steel town of Mangiano'') was an iron and steel foundry in the small town of Mongiana, in Calabri ...

was an iron foundry and weapons factory. Founded in 1770, it employed 1600 workers in 1860 and closed in 1880. In Sicily (near Catania

Catania (, , Sicilian and ) is the second largest municipality in Sicily, after Palermo. Despite its reputation as the second city of the island, Catania is the largest Sicilian conurbation, among the largest in Italy, as evidenced also b ...

and Agrigento

Agrigento (; scn, Girgenti or ; grc, Ἀκράγας, translit=Akrágas; la, Agrigentum or ; ar, كركنت, Kirkant, or ''Jirjant'') is a city on the southern coast of Sicily, Italy and capital of the province of Agrigento. It was one o ...

), sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formul ...

was mined to make gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

. The Sicilian mines were able to satisfy most of the global demand for sulfur. Silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from th ...

cloth production was focused in San Leucio

San Leucio is a ''frazione'' of the '' comune'' of Caserta, in the region of Campania in southern Italy. It is most notable for a resort developed around an old silk factory, named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997.

It is located 3.5 ...

(near Caserta

Caserta () is the capital of the province of Caserta in the Campania region of Italy. It is an important agricultural, commercial, and industrial '' comune'' and city. Caserta is located on the edge of the Campanian plain at the foot of the Ca ...

). The region of Basilicata

it, Lucano (man) it, Lucana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

...

also had several mills in Potenza

Potenza (, also , ; , Potentino dialect: ''Putenz'') is a ''comune'' in the Southern Italian region of Basilicata (former Lucania).

Capital of the Province of Potenza and the Basilicata region, the city is the highest regional capital and one ...

and San Chirico Raparo, where cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

, wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool. ...

and silk were processed. Food processing

Food processing is the transformation of agricultural products into food, or of one form of food into other forms. Food processing includes many forms of processing foods, from grinding grain to make raw flour to home cooking to complex in ...

was widespread, especially near Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

( Torre Annunziata and Gragnano

Gragnano, a hill town located between a mountain crest and the Amalfi Coast, is a '' comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Naples in southern Italy's Campania region, located about southeast of Naples city.

Gragnano borders the fo ...

).

Sulfur

The kingdom maintained a large sulfur mining industry. In the increasingly industrialized Great Britain, with the repeal oftariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and p ...

s on salt in 1824, demand for sulfur from Sicily surged. The growing British control and exploitation of the mining, refining, and transportation of sulfur, combined with the failure of this lucrative export to transform Sicily's backward and impoverished economy, led to the 'Sulfur Crisis' of 1840. This was precipitated when King Ferdinand II granted a monopoly of the sulfur industry to a French company, in violation of an 1816 trade agreement with Britain. A peaceful solution was eventually negotiated by France.

Transport

With all of its major cities boasting successful ports, transport and trade in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was most efficiently conducted by sea. The kingdom possessed the largest merchant fleet in the Mediterranean. Urban road conditions were to the best European standards; by 1839, the main streets of Naples were gas-lit. Efforts were made to tackle the tough mountainous terrain; Ferdinand II built the cliff-top road along the Sorrentine peninsula. Road conditions in the interior and hinterland areas of the kingdom made internal trade difficult. The first railways and iron-suspension bridges in Italy were developed in the south, as was the first overland electric telegraph cable.

With all of its major cities boasting successful ports, transport and trade in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was most efficiently conducted by sea. The kingdom possessed the largest merchant fleet in the Mediterranean. Urban road conditions were to the best European standards; by 1839, the main streets of Naples were gas-lit. Efforts were made to tackle the tough mountainous terrain; Ferdinand II built the cliff-top road along the Sorrentine peninsula. Road conditions in the interior and hinterland areas of the kingdom made internal trade difficult. The first railways and iron-suspension bridges in Italy were developed in the south, as was the first overland electric telegraph cable.

Technological and scientific achievements

The kingdom achieved several scientific and technological accomplishments, such as the first steamboat in the Mediterrean Sea (1818), built in the shipyard of Stanislao Filosa al ponte di Vigliena, near Naples, and the first railway in the Italian peninsula (1839), which connected Naples to Portici. However, until the Italian unification, the railway development was highly limited. In the year 1859, the kingdom had only 99 kilometers of rail, compared to the 850 kilometers ofPiedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

. Southern landscape was mainly mountainous so making the process of building railways was quite difficult, as building railway tunnels was much harder at the time. Other achievements included the first volcano observatory in the world, l'Osservatorio Vesuviano (1841). The rails for the first Italian railways were built in Mongiana as well. All the rails of the old railways that went from the south to as far as Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label= Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different na ...

were built in Mongiana.

Education

The kingdom was home to three universities namely those inNaples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

founded in 1224, Catania

Catania (, , Sicilian and ) is the second largest municipality in Sicily, after Palermo. Despite its reputation as the second city of the island, Catania is the largest Sicilian conurbation, among the largest in Italy, as evidenced also b ...

founded in 1434 and Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The city is noted for its ...

founded in 1806. Also in Naples, established by Matteo Ripa

Matteo is the Italian form of the given name Matthew. Another form is Mattia. The Hebrew meaning of Matteo is "gift of god". Matteo can also be used as a patronymic surname, often in the forms of de Matteo, De Matteo or DeMatteo, meaning " escenda ...

in 1732, was the ''Collegio dei Cinesi'' today the University of Naples "L'Orientale teaching Sinology

Sinology, or Chinese studies, is an academic discipline that focuses on the study of China primarily through Chinese philosophy, language, literature, culture and history and often refers to Western scholarship. Its origin "may be traced to the e ...

and Oriental studies

Oriental studies is the academic field that studies Near Eastern and Far Eastern societies and cultures, languages, peoples, history and archaeology. In recent years, the subject has often been turned into the newer terms of Middle Eastern stu ...

. Despite these institutions of higher learning the kingdom however had no obligation for school attendance nor a recognizable school system. Clerics could inspect schools and had a veto power over appointments of teachers who were for the most part from the clergy anyhow. The literacy rate

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, huma ...

was just 14.4% in 1861.

Social spending and public hygiene

The situation of the time in terms of social expenditure andpublic hygiene

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

is mainly known today thanks to the writings of the historian and journalist Raffaele De Cesare. It is well known that public hygiene conditions in the regions of the Kingdom of the Two-Siciles are very poor and especially in the central and rural regions. Most small municipalities do not have sewers and have a low water supply due to the lack of public investment in the construction of pipes, which also means that most private houses do not have toilets. Paved roads are rare, except in the area around Naples or on the main roads of the country, and they are often flooded and have many potholes.

Moreover, most rural inhabitants often live in small old towns which, due to lack of social expenditure, become unhealthy, allowing many infectious diseases

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable di ...

to spread rapidly. While the municipal administration has few economic means to remedy the situation, the gentlemen often have whole sections of streets paved in front of the entrance of their home

Geography

Departments

The peninsula was divided into fifteen departments and Sicily was divided into seven departments. The island itself had a special administrative status, with its base at Palermo. In 1860, when the Two Sicilies were conquered by the

The peninsula was divided into fifteen departments and Sicily was divided into seven departments. The island itself had a special administrative status, with its base at Palermo. In 1860, when the Two Sicilies were conquered by the Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia,The name of the state was originally Latin: , or when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is , in French , in Sardinian , and in Piedmontese . also referred to as the Kingdom of Savoy-S ...

, the departments became provinces of Italy

The provinces of Italy ( it, province d'Italia) are the second-level administrative divisions of the Italian Republic, on an intermediate level between a municipality () and a region (). Since 2015, provinces have been classified as "instituti ...

, according to the Urbano Rattazzi

Urbano Pio Francesco Rattazzi (; 29 June 1808 5 June 1873) was an Italian statesman.

Personal life

He was born in Alessandria (Piedmont). He studied law at Turin, and in 1838 began his practice, which met with marked success at the capital and ...

law.

Peninsula departments

* Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

* Terra di Lavoro

Terra di Lavoro (Liburia in Latin) is the name of a historical region of Southern Italy. It corresponds roughly to the modern southern Lazio and northern Campania and upper north west and west border area of Molise regions of Italy.

In Itali ...

- Capua

Capua ( , ) is a city and ''comune'' in the province of Caserta, in the region of Campania, southern Italy, situated north of Naples, on the northeastern edge of the Campanian plain.

History

Ancient era

The name of Capua comes from the Etrus ...

/ Caserta

Caserta () is the capital of the province of Caserta in the Campania region of Italy. It is an important agricultural, commercial, and industrial '' comune'' and city. Caserta is located on the edge of the Campanian plain at the foot of the Ca ...

from 1818

* Principato Citra

This page is a list of the rulers of the Principality of Salerno.

When Prince Sicard of Benevento was assassinated by Radelchis in 839, the people of Salerno promptly proclaimed his brother, Siconulf, prince. War raged between Radelchis and Sico ...

- Salerno

Salerno (, , ; nap, label= Salernitano, Saliernë, ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' in Campania (southwestern Italy) and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after ...

* Avellino

Avellino () is a town and ''comune'', capital of the province of Avellino in the Campania region of southern Italy. It is situated in a plain surrounded by mountains east of Naples and is an important hub on the road from Salerno to Benevento.

...

* Basilicata

it, Lucano (man) it, Lucana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

...

- Potenza

Potenza (, also , ; , Potentino dialect: ''Putenz'') is a ''comune'' in the Southern Italian region of Basilicata (former Lucania).

Capital of the Province of Potenza and the Basilicata region, the city is the highest regional capital and one ...

* Capitanata

The Province of Foggia ( it, Provincia di Foggia ; Foggiano: ) is a province in the Apulia (Puglia) region of southern Italy.

This province is also known as Daunia, after the Daunians, an Iapygian pre-Roman tribe living in Tavoliere plain, and ...

-

* Bari

Bari ( , ; nap, label= Barese, Bare ; lat, Barium) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia region, on the Adriatic Sea, southern Italy. It is the second most important economic centre of mainland Southern Ital ...

* Lecce

Lecce ( ); el, label= Griko, Luppìu, script=Latn; la, Lupiae; grc, Λουπίαι, translit=Loupíai), group=pron is a historic city of 95,766 inhabitants (2015) in southern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Lecce, the provi ...

* Cosenza

Cosenza (; :it:Dialetto cosentino, local dialect: ''Cusenza'', ) is a city in Calabria, Italy. The city centre has a population of approximately 70,000; the urban area counts more than 200,000 inhabitants. It is the capital of the Province of Cosen ...

* Catanzaro

Catanzaro (, or ; scn, label= Catanzarese, Catanzaru ; , or , ''Katastaríoi Lokrói''; ; la, Catacium), also known as the "City of the two Seas", is an Italian city of 86,183 inhabitants (2020), the capital of the Calabria region and of its p ...

* Campobasso

Campobasso (, ; nap, label= Campobassan, Cambuàsce ) is a city and '' comune'' in southern Italy, the capital of the region of Molise and of the province of Campobasso. It is located in the high basin of the Biferno river, surrounded by ...

* Abruzzo Citra