King Island emu on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The King Island emu (''Dromaius novaehollandiae minor'') is an extinct subspecies of

The King Island emu was the smallest type of emu and was about 44% or half of the size of the mainland bird. It was about tall. According to Péron's interview with the local English sealer Daniel Cooper, the largest specimens were up to 137 cm (4.5 ft) in length, and the heaviest weighed 20 to 23 kg (45 to 50 lb). It had a darker plumage, with extensive black feathers on the neck and head, and blackish feathers on the body, where it was also mixed with brown. The bill and feet were blackish, and the naked skin on the side of the neck was blue. The 2011 genetic study did not find genes commonly associated with

The King Island emu was the smallest type of emu and was about 44% or half of the size of the mainland bird. It was about tall. According to Péron's interview with the local English sealer Daniel Cooper, the largest specimens were up to 137 cm (4.5 ft) in length, and the heaviest weighed 20 to 23 kg (45 to 50 lb). It had a darker plumage, with extensive black feathers on the neck and head, and blackish feathers on the body, where it was also mixed with brown. The bill and feet were blackish, and the naked skin on the side of the neck was blue. The 2011 genetic study did not find genes commonly associated with  The King Island emu and the mainland emu show few morphological differences other than their significant difference in size. Mathews stated that the legs and bill were shorter than those of the mainland emu, yet the toes were nearly of equal length, and therefore proportionally longer. The tarsus of the King Island emu was also three times longer than the culmen, whereas it was four times longer in the mainland emu. Additional traits that supposedly distinguish this bird from the mainland emu have previously been suggested to be the distal foramen of the tarsometatarsus, and the contour of the cranium. However, the distal foramen is known to be variable in the mainland emu showing particular diversity between juvenile and adult forms and is therefore taxonomically insignificant. The same is true of the contour of the cranium, which is more dome-shaped in the King Island emu, a feature that is also seen in juvenile mainland emus.

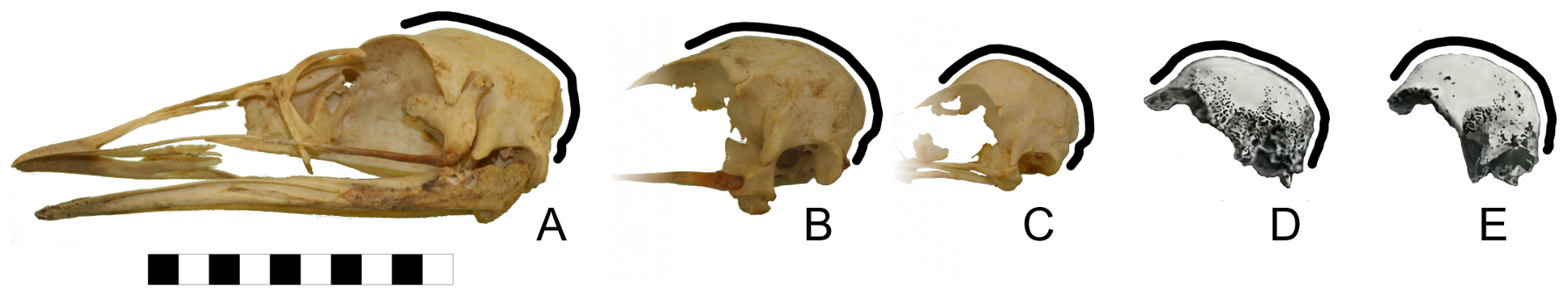

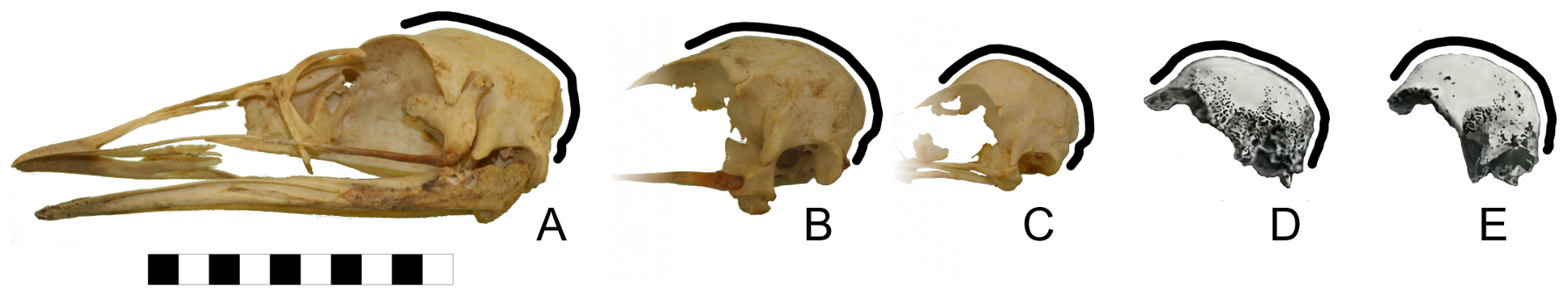

The King Island emu and the mainland emu show few morphological differences other than their significant difference in size. Mathews stated that the legs and bill were shorter than those of the mainland emu, yet the toes were nearly of equal length, and therefore proportionally longer. The tarsus of the King Island emu was also three times longer than the culmen, whereas it was four times longer in the mainland emu. Additional traits that supposedly distinguish this bird from the mainland emu have previously been suggested to be the distal foramen of the tarsometatarsus, and the contour of the cranium. However, the distal foramen is known to be variable in the mainland emu showing particular diversity between juvenile and adult forms and is therefore taxonomically insignificant. The same is true of the contour of the cranium, which is more dome-shaped in the King Island emu, a feature that is also seen in juvenile mainland emus.

Péron stated that the nest was usually situated near water and on the ground under the shade of a bush. It was constructed of sticks and lined with dead leaves and moss; it was oval in shape and not very deep. He claimed that seven to nine eggs were laid always on 25 and 26 July, but the selective advantage of this breeding synchronisation is unknown. The female incubated the eggs, but the male apparently developed a brood patch, which indicates it contributed as well. The non-incubating parent also stayed by the nest, and the chicks left the nest two to three days after hatching. The eggs were preyed upon by snakes, rats, and quolls. Péron gave the incubation period as five or six weeks, but since the mainland emu incubates for 50 to 56 days, Pfennigwerth pointed out that this may be too short. He stated a mother emu would defend its young from

Péron stated that the nest was usually situated near water and on the ground under the shade of a bush. It was constructed of sticks and lined with dead leaves and moss; it was oval in shape and not very deep. He claimed that seven to nine eggs were laid always on 25 and 26 July, but the selective advantage of this breeding synchronisation is unknown. The female incubated the eggs, but the male apparently developed a brood patch, which indicates it contributed as well. The non-incubating parent also stayed by the nest, and the chicks left the nest two to three days after hatching. The eggs were preyed upon by snakes, rats, and quolls. Péron gave the incubation period as five or six weeks, but since the mainland emu incubates for 50 to 56 days, Pfennigwerth pointed out that this may be too short. He stated a mother emu would defend its young from

The exact cause for the extinction of the King Island emu is unknown. Soon after the bird was discovered, sealers settled on the island because of the abundance of

The exact cause for the extinction of the King Island emu is unknown. Soon after the bird was discovered, sealers settled on the island because of the abundance of

emu

The emu () (''Dromaius novaehollandiae'') is the second-tallest living bird after its ratite relative the ostrich. It is endemic to Australia where it is the largest native bird and the only extant member of the genus '' Dromaius''. The emu ...

that was endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

to King Island, in the Bass Strait between mainland Australia and Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

. Its closest relative may be the extinct Tasmanian emu

The Tasmanian emu (''Dromaius novaehollandiae diemenensis'') is an extinct subspecies of emu. It was found in Tasmania, where it had become isolated during the Late Pleistocene. As opposed to the other insular emu taxa, the King Island emu and t ...

(''D. n. diemenensis''), as they belonged to a single population until less than 14,000 years ago when Tasmania and King Island were still connected. The small size of the King Island emu may be an example of insular dwarfism

Insular dwarfism, a form of phyletic dwarfism, is the process and condition of large animals evolving or having a reduced body size when their population's range is limited to a small environment, primarily islands. This natural process is disti ...

. The King Island emu was the smallest of all known emus and had darker plumage than the mainland emu. It was black and brown and had naked blue skin on the neck, and its chicks were striped like those on the mainland. The subspecies was distinct from the likewise small and extinct Kangaroo Island emu

Kangaroos are four marsupials from the family Macropodidae (macropods, meaning "large foot"). In common use the term is used to describe the largest species from this family, the red kangaroo, as well as the antilopine kangaroo, eastern gre ...

(''D. n. baudinianus'') in a number of osteological

Osteology () is the scientific study of bones, practised by osteologists. A subdiscipline of anatomy, anthropology, and paleontology, osteology is the detailed study of the structure of bones, skeletal elements, teeth, microbone morphology, func ...

details, including size. The behaviour of the King Island emu probably did not differ much from that of the mainland emu. The birds gathered in flocks to forage and during breeding time. They fed on berries, grass and seaweed. They ran swiftly and could defend themselves by kicking. The nest was shallow and consisted of dead leaves and moss. Seven to nine eggs were laid, which were incubated by both parents.

Europeans discovered the King Island emu in 1802 during early expeditions to the island, and most of what is known about the bird in life comes from an interview French naturalist François Péron conducted with a sealer there, as well as depictions by artist Charles Alexandre Lesueur

Charles Alexandre Lesueur (1 January 1778 in Le Havre – 12 December 1846 in Le Havre) was a French naturalist, artist, and explorer. He was a prolific natural-history collector, gathering many type specimens in Australia, Southeast Asia, ...

. They had arrived on King Island in 1802 with Nicolas Baudin's expedition, and in 1804 several live and stuffed King and Kangaroo Island emus were sent to France. The two live King Island specimens were kept in the Jardin des Plantes, and the remains of these and the other birds are scattered throughout various museums in Europe today. The logbooks of the expedition did not specify from which island each captured bird originated, or even that they were taxonomically distinct, so their status remained unclear until more than a century later. Hunting pressure and fires started by early settlers on King Island likely drove the wild population to extinction by 1805. The captive specimens in Paris both died in 1822 and are believed to have been the last of their kind.

Taxonomy

There was long confusion regarding the taxonomic status and geographic origin of the small islandemu

The emu () (''Dromaius novaehollandiae'') is the second-tallest living bird after its ratite relative the ostrich. It is endemic to Australia where it is the largest native bird and the only extant member of the genus '' Dromaius''. The emu ...

taxa from King Island and Kangaroo Island

Kangaroo Island, also known as Karta Pintingga (literally 'Island of the Dead' in the language of the Kaurna people), is Australia's third-largest island, after Tasmania and Melville Island. It lies in the state of South Australia, southwest ...

, since specimens of both populations were transported to France as part of the same French expedition to Australia

The Baudin expedition of 1800 to 1803 was a French expedition to map the coast of New Holland (now Australia). Nicolas Baudin was selected as leader in October 1800. The expedition started with two ships, '' Géographe'', captained by Baudin, and ...

in the early 1800s. The logbooks of the expedition failed to clearly state where and when the small emu individuals were collected, and this has resulted in a plethora of scientific names

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

subsequently being coined for either bird, many on questionable grounds, and the idea that all specimens had originated from Kangaroo Island. Furthermore, in 1914, L. Brasil argued the expedition did not encounter emus on King Island, because the weather had been too bad for them to leave their camp. The French also referred to both emus and cassowaries as "casoars" at the time, which has led to further confusion.

The French naturalist Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot

Louis Pierre Vieillot (10 May 1748, Yvetot – 24 August 1830, Sotteville-lès-Rouen) was a French ornithologist.

Vieillot is the author of the first scientific descriptions and Linnaean names of a number of birds, including species he collec ...

coined the binomial ''Dromaius ater'' in 1817. Various collectors found subfossil emu remains on King Island during the early 20th century, the first by the Australian amateur ornithologist Archibald James Campbell

Archibald James Campbell (18 February 1853 – 11 September 1929) was an Australian civil servant in the Victorian (later Australian) government Customs Service. However, his international reputation rests on his expertise as an amateur ornit ...

in 1903, near a lagoon on the east coast. In 1906, the Australian ornithologist Walter Baldwin Spencer

Sir Walter Baldwin Spencer (23 June 1860 – 14 July 1929), commonly referred to as Baldwin Spencer, was a British-Australian evolutionary biologist, anthropologist and ethnologist.

He is known for his fieldwork with Aboriginal peoples in ...

coined the name ''Dromaius minor'' based on some Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed in ...

subfossil bones and eggshells found on King Island, which he considered distinct from ''D. ater'' (then thought to be from Kangaroo Island) due to the smaller size of the former. The Australian ornithologist William Vincent Legge

Colonel William Vincent Legge (2 September 1841 – 25 March 1918) was an Australian soldier and an ornithologist who documented the birds of Sri Lanka. Legge's hawk-eagle is named after him as is Legge's flowerpecker and Legges Tor, the seco ...

also coined a name for these remains in 1906, ''Dromaius bassi'', but at a later date. In his 1907 book '' Extinct Birds'', the British zoologist Walter Rothschild

Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild, Baron de Rothschild, (8 February 1868 – 27 August 1937) was a British banker, politician, zoologist and soldier, who was a member of the Rothschild family. As a Zionist leader, he was presen ...

stated that Vieillot's description actually referred to the mainland emu, and that the name ''D. ater'' was therefore invalid. Believing the skin in Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle

The French National Museum of Natural History, known in French as the ' (abbreviation MNHN), is the national natural history museum of France and a ' of higher education part of Sorbonne Universities. The main museum, with four galleries, is loc ...

of Paris was from Kangaroo Island, he made it the type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes th ...

of his new species ''Dromaius peroni'', named after the French naturalist François Péron, who is the main source of information about the bird in life. Spencer reported more emu bones from King Island in 1910, which he compared to bones from Kangaroo Island which were by then considered to belong to ''D. peroni''. The Australian amateur ornithologist Gregory Mathews

Gregory Macalister Mathews CBE FRSE FZS FLS (10 September 1876 – 27 March 1949) was an Australian-born amateur ornithologist who spent most of his later life in England.

Life

He was born in Biamble in New South Wales the son of Robert H. M ...

coined further names in the early 1910s, including a new genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

name, ''Peronista'', as he believed the King and Kangaroo Island birds were generically distinct from the mainland emu.

Later writers claimed that the subfossil remains found on King and Kangaroo Islands were not discernibly different, and that they therefore belonged to the same taxon

In biology, a taxon ( back-formation from '' taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular n ...

. In 1959, the French ornithologist Christian Jouanin

Christian Jouanin (1925 – 8 November 2014) was a prominent French ornithologist and expert on petrels. He worked for the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle in Paris and is a former Vice President of the International Union for Conservat ...

proposed that none of the skins were actually from Kangaroo Island, after inspecting expedition and museum documents. In 1990, Jouanin and the French palaeontologist Jean-Christophe Balouet used environmental forensics to demonstrate that the mounted skin in Paris came from King Island, and that at least one live bird had been brought from each island. All scientific names given to the Kangaroo Island emu

Kangaroos are four marsupials from the family Macropodidae (macropods, meaning "large foot"). In common use the term is used to describe the largest species from this family, the red kangaroo, as well as the antilopine kangaroo, eastern gre ...

were therefore based on specimens from King Island or were otherwise invalid, leaving it nameless. Based on later finds of subfossil material in 1984, the Australian ornithologist Shane A. Parker confirmed the separate geographic origin and distinct morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

* Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

* Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies ...

of the King and Kangaroo Island emus, finding that the latter was larger. Parker named the Kangaroo Island bird ''Dromaius baudinianus'', after Nicolas Baudin

Nicolas Thomas Baudin (; 17 February 1754 – 16 September 1803) was a French explorer, cartographer, naturalist and hydrographer, most notable for his explorations in Australia and the southern Pacific.

Biography

Early career

Born a comm ...

, the leader of the French expedition. The name ''Dromaius ater'' was kept for the King Island emu.

There are few morphological differences that distinguish the extinct insular emus from the mainland emu besides their size, but all three taxa were most often considered distinct species. A 2011 study by the Australian geneticist Tim H. Heupink and colleagues of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA, which was extracted from five subfossil King Island emu bones, showed that its genetic variation fell within that of the extant mainland emus. It was therefore interpreted as conspecific

Biological specificity is the tendency of a characteristic such as a behavior or a biochemical variation to occur in a particular species.

Biochemist Linus Pauling stated that "Biological specificity is the set of characteristics of living organis ...

with the emus of the Australian mainland, and was reclassified as a subspecies of ''Dromaius novaehollandiae'', ''D. n. ater''. Other animals present on King Island are also considered as subspecies of their mainland or Tasmanian

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

counterparts rather than distinct species. The authors suggested that further studies using different methods might be able to find features that distinguish the taxa. In its 2013 edition, The Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World emended the trinomial name of the King Island emu to ''D. n. minor'', based on Spencer's ''D. minor'', on the ground that Vieillot's ''D. ater'' was originally meant for the mainland emu. This rationale was accepted by the IOC World Bird List, which used ''D. n. minor'' thereafter.

In 2014–2015, the English palaeontologist Julian Hume and colleagues conducted a search for emu fossils on King Island; no major palaeontological surveys had been done since the early 20th century, apart from discoveries made by the local natural historian Christian Robertson during the preceding thirty years. In 2014, Hume and colleagues found emu subfossils in Cape Wickham, but upon returning to the site in 2015, the area had been turned into a golf course, and the researchers were denied access to the site. They cautioned in 2018 that other fossiliferous sites on King Island were also under such threat, and highlighted the need to protect them. The researchers also identified an area near Surprise Bay where subfossils had been collected in 1906, but found it almost impossible to find more, since the area had been covered in grass in the meantime (the grass had previously been kept down by livestock). In 2021, Hume and Robertson reported a King Island emu eggshell missing a few pieces, which Robertson had discovered in a sand dune during fieldwork. This the only known almost complete egg of this emu, glued together from broken pieces.

Evolution

During the Late Quaternary period (0.7 million years ago), small emus lived on a number of offshore islands of mainland Australia. In addition to the King Island emu, these included taxa found on Kangaroo Island and Tasmania, all of which are now extinct. The smallest taxon, the King Island emu, was confined to a small island situated in the Bass Strait between Tasmania and Victoria, approximately 100 km (62 mi) from both coasts. King Island was once part of theland bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea leve ...

which connected Tasmania and mainland Australia, but rising sea levels following the last glacial maximum eventually isolated the island. As a result of phenotypic plasticity

Phenotypic plasticity refers to some of the changes in an organism's behavior, morphology and physiology in response to a unique environment. Fundamental to the way in which organisms cope with environmental variation, phenotypic plasticity encompa ...

the King Island emu population possibly underwent a process of insular dwarfism

Insular dwarfism, a form of phyletic dwarfism, is the process and condition of large animals evolving or having a reduced body size when their population's range is limited to a small environment, primarily islands. This natural process is disti ...

. Emu eggshells were also identified from Flinders Island

Flinders Island, the largest island in the Furneaux Group, is a island in the Bass Strait, northeast of the island of Tasmania. Flinders Island was the place where the last remnants of aboriginal Tasmanian population were exiled by the colo ...

(in the opposite, eastern end of the Bass Strait) in 2017, possibly representing a distinct taxon.

According to the 2011 genetic study, the close relation between the King Island and mainland emus indicates that the former population was isolated from the latter relatively recently, due to sea level changes in the Bass Strait, as opposed to a founding

Founding may refer to:

* The formation of a corporation, government, or other organization

* The laying of a building's Foundation

* The casting of materials in a mold

See also

* Foundation (disambiguation)

* Incorporation (disambiguation)

In ...

emu lineage that diverged from the mainland emu far earlier and had subsequently gone extinct on the mainland. Models of sea level change indicate that Tasmania, including King Island, was isolated from the Australian mainland around 14,000 years ago. Up to several thousand years later King Island was then separated from Tasmania. This scenario would suggest that a population ancestral to both the King Island and Tasmanian emu

The Tasmanian emu (''Dromaius novaehollandiae diemenensis'') is an extinct subspecies of emu. It was found in Tasmania, where it had become isolated during the Late Pleistocene. As opposed to the other insular emu taxa, the King Island emu and t ...

was initially isolated from the mainland taxon, after which the King Island and Tasmanian populations were separated. This, in turn, indicates that the likewise extinct Tasmanian emu is probably as closely related to the mainland emu as is the King Island emu, with both the King Island and Tasmanian emu being more closely related to each other. Fossil emu taxa show an average size between that of the King Island emu and mainland emu. Hence, mainland emus can be regarded as a large or gigantic form.

A 2018 study by Australian geneticist Vicki A. Thomson and colleagues (based on ancient bone, eggshell and feather samples) found that the emus of Kangaroo Island and Tasmania also represented sub-populations of the mainland emu, and therefore belonged in the same species. They also found that the size of the island emus scaled linearly to the size of the islands they inhabited (the King Island emu was the smallest, while the Tasmanian was the largest), while time in isolation did not affect their size. This suggest that island size was the important driver in dwarfism of these emus, probably due to limitation in resources, though the exact effect needs to be confirmed. The little genetic differentiation between island emus indicates their dwarfism evolved rapidly and independently since they became isolated from each other. King Island is , and was isolated from Tasmania for 12,000 years, while Tasmania was itself isolated from mainland Australia for 14,000 years. Kangaroo Island is and was isolated from the mainland 10,000 years ago. A 2020 genetic study of the only known Kangaroo Island emu skin by the French ornithologist Alice Cibois and colleagues also supported retaining the three island emus as subspecies, with the King Island emu as ''D. n. minor''.

Description

The King Island emu was the smallest type of emu and was about 44% or half of the size of the mainland bird. It was about tall. According to Péron's interview with the local English sealer Daniel Cooper, the largest specimens were up to 137 cm (4.5 ft) in length, and the heaviest weighed 20 to 23 kg (45 to 50 lb). It had a darker plumage, with extensive black feathers on the neck and head, and blackish feathers on the body, where it was also mixed with brown. The bill and feet were blackish, and the naked skin on the side of the neck was blue. The 2011 genetic study did not find genes commonly associated with

The King Island emu was the smallest type of emu and was about 44% or half of the size of the mainland bird. It was about tall. According to Péron's interview with the local English sealer Daniel Cooper, the largest specimens were up to 137 cm (4.5 ft) in length, and the heaviest weighed 20 to 23 kg (45 to 50 lb). It had a darker plumage, with extensive black feathers on the neck and head, and blackish feathers on the body, where it was also mixed with brown. The bill and feet were blackish, and the naked skin on the side of the neck was blue. The 2011 genetic study did not find genes commonly associated with melanism

The term melanism refers to black pigment and is derived from the gr, μελανός. Melanism is the increased development of the dark-colored pigment melanin in the skin or hair.

Pseudomelanism, also called abundism, is another variant of ...

in birds, but proposed the dark colouration could be due to alternative genetic or non-genetic factors.

Péron stated there was little difference between the sexes, but that the male was perhaps brighter in colouration and slightly larger. The juveniles were grey, while the chicks were striped like other emus. There were no seasonal variations in plumage. Since the female mainland emus are on average larger than the males, and can turn brighter during the mating season, contrary to the norm in other bird species, the Australian museum curator Stephanie Pfennigwerth suggested that some of these observations may have been based on erroneous conventional wisdom

The conventional wisdom or received opinion is the body of ideas or explanations generally accepted by the public and/or by experts in a field. In religion, this is known as orthodoxy.

Etymology

The term is often credited to the economist John ...

. Hume and Robinson also suggested female King Island emus were larger than the males, and that Cooper could have mistaken brooding males for females when he stated the males were larger.

Subfossil remains of the King Island emu show that the tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects ...

was about 330 mm (13 in) long, and the femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates wit ...

was 180 mm (7 in) long. The pelvis was 280 mm (11 in) long, 64 mm (2.5 in) wide at the front, and 86 mm (3 in) wide at the back. The tarsometatarsus averaged 232 mm (9 in) in length. In males, the tibiotarsus

The tibiotarsus is the large bone between the femur and the tarsometatarsus in the leg of a bird. It is the fusion of the proximal part of the tarsus with the tibia.

A similar structure also occurred in the Mesozoic Heterodontosauridae. These s ...

averaged 261 mm (10 in), whereas it averaged 301 mm (12 in) in females. In contrast, the same bones measured 269 mm (10.5 in) and 305 mm (12 in) in the Kangaroo Island emu. Apart from being smaller, the King Island emu differed osteologically from the Kangaroo Island emu in the intertrochlear foramen

In anatomy and osteology, a foramen (;Entry "foramen"

in

of the tarsometatarsus usually being fully or partially abridged. The outer in

trochlea

Trochlea (Latin for pulley) is a term in anatomy. It refers to a grooved structure reminiscent of a pulley's wheel.

Related to joints

Most commonly, trochleae bear the articular surface of saddle and other joints:

* Trochlea of humerus (part of ...

was more incurved towards the middle trochlea in the Kangaroo Island bird, whereas they were parallel in the King Island emu.

The King Island emu and the mainland emu show few morphological differences other than their significant difference in size. Mathews stated that the legs and bill were shorter than those of the mainland emu, yet the toes were nearly of equal length, and therefore proportionally longer. The tarsus of the King Island emu was also three times longer than the culmen, whereas it was four times longer in the mainland emu. Additional traits that supposedly distinguish this bird from the mainland emu have previously been suggested to be the distal foramen of the tarsometatarsus, and the contour of the cranium. However, the distal foramen is known to be variable in the mainland emu showing particular diversity between juvenile and adult forms and is therefore taxonomically insignificant. The same is true of the contour of the cranium, which is more dome-shaped in the King Island emu, a feature that is also seen in juvenile mainland emus.

The King Island emu and the mainland emu show few morphological differences other than their significant difference in size. Mathews stated that the legs and bill were shorter than those of the mainland emu, yet the toes were nearly of equal length, and therefore proportionally longer. The tarsus of the King Island emu was also three times longer than the culmen, whereas it was four times longer in the mainland emu. Additional traits that supposedly distinguish this bird from the mainland emu have previously been suggested to be the distal foramen of the tarsometatarsus, and the contour of the cranium. However, the distal foramen is known to be variable in the mainland emu showing particular diversity between juvenile and adult forms and is therefore taxonomically insignificant. The same is true of the contour of the cranium, which is more dome-shaped in the King Island emu, a feature that is also seen in juvenile mainland emus.

Behaviour and ecology

Péron's interview described some aspects of the behaviour of the King Island emu. He wrote that the bird was generally solitary but gathered in flocks of ten to twenty at breeding time, then wandered off in pairs. They ate berries, grass and seaweed, and foraged mainly during morning and evening. They were swift runners, but were apparently slower than the mainland birds, due to being fat. They swam well, but only did so when necessary. They reportedly liked the shade of lagoons and the shoreline, rather than open areas. They used a claw on each wing for scratching themselves. If unable to flee from thehunting dogs

A hunting dog is a canine that hunts with or for hunters. There are several different types of hunting dog developed for various tasks and purposes. The major categories of hunting dog include hounds, terriers, dachshunds, cur type dogs, and g ...

of the sealers, they would defend themselves by kicking, which could inflict a great deal of harm.

The English Captain Matthew Flinders did not encounter emus when he visited King Island in 1802, but his naturalist, Robert Brown, examined their dung and noted they had chiefly fed on the berries of ''Leptecophylla juniperina

''Leptecophylla juniperina'' is a species of flowering plant in the family Ericaceae. The species is native to New Zealand and the Australian states of Tasmania and Victoria (Australia), Victoria. The plant's fruit is edible, raw or cooked. Plan ...

''. An account by English ornithologist John Latham about the " Van Diemen's cassowary" may also refer to the King Island emu, based on the small size described. In addition to a physical description, he stated that they gathered in groups of 70 to 80 individuals in a given location while foraging, behaviour that was exploited by hunters. Hume and colleagues noted that most emu subfossils from King Island were found on the drier, leeward west coast of the island, and though probably due to preservation bias, they suggested that the emus were restricted to coastal and more open inland areas, and not found in the dense interior forests. An 1802 report by the English surveyor Charles Grimes also supported this, stating there were "plenty on the coast–but not inland". The tall, dense eucalypt

Eucalypt is a descriptive name for woody plants with capsule fruiting bodies belonging to seven closely related genera (of the tribe Eucalypteae) found across Australasia:

''Eucalyptus'', ''Corymbia'', ''Angophora'', '' Stockwellia'', ''Allosyn ...

forests of the island have since been destroyed.

Breeding

Péron stated that the nest was usually situated near water and on the ground under the shade of a bush. It was constructed of sticks and lined with dead leaves and moss; it was oval in shape and not very deep. He claimed that seven to nine eggs were laid always on 25 and 26 July, but the selective advantage of this breeding synchronisation is unknown. The female incubated the eggs, but the male apparently developed a brood patch, which indicates it contributed as well. The non-incubating parent also stayed by the nest, and the chicks left the nest two to three days after hatching. The eggs were preyed upon by snakes, rats, and quolls. Péron gave the incubation period as five or six weeks, but since the mainland emu incubates for 50 to 56 days, Pfennigwerth pointed out that this may be too short. He stated a mother emu would defend its young from

Péron stated that the nest was usually situated near water and on the ground under the shade of a bush. It was constructed of sticks and lined with dead leaves and moss; it was oval in shape and not very deep. He claimed that seven to nine eggs were laid always on 25 and 26 July, but the selective advantage of this breeding synchronisation is unknown. The female incubated the eggs, but the male apparently developed a brood patch, which indicates it contributed as well. The non-incubating parent also stayed by the nest, and the chicks left the nest two to three days after hatching. The eggs were preyed upon by snakes, rats, and quolls. Péron gave the incubation period as five or six weeks, but since the mainland emu incubates for 50 to 56 days, Pfennigwerth pointed out that this may be too short. He stated a mother emu would defend its young from crows

The Common Remotely Operated Weapon Station (CROWS) is a series of remote weapon stations used by the US military on its armored vehicles and ships. It allows weapon operators to engage targets without leaving the protection of their vehicle. ...

with its beak, but this is now known to be strictly male behaviour.

Hume and Robertson compared the eggs of all emu taxa in 2021, and found that the eggs of the island dwarf emus were within or close to the size and smallest volume and mass ranges for mainland birds, with seemingly thinner eggshells. The egg of the mainland emu weighs 1.3 lbs. (0.59 kilograms) and has a volume of about 0.14 gallons (539 milliliters), while those of the King Island emu weighed 1.2 lbs. (0.54 kg) and had a volume of 0.12 gallons (465 mL). The egg mass of the mainland emu accounts for 1.6% of its body mass, whereas the egg mass of the King Island emu accounted for 2.3% of its body mass, even though it was 44% lighter than the mainland bird. Hume and Robertson attempted to explain these findings, and noted that emus and other ratites

A ratite () is any of a diverse group of flightless, large, long-necked, and long-legged birds of the infraclass Palaeognathae. Kiwi, the exception, are much smaller and shorter-legged and are the only nocturnal extant ratites.

The systematics ...

have precocial

In biology, altricial species are those in which the young are underdeveloped at the time of birth, but with the aid of their parents mature after birth. Precocial species are those in which the young are relatively mature and mobile from the mome ...

juveniles, that is, relatively mature and mobile when they hatch, and appear to have laid their eggs at the same time.

Hume and Robertson suggested the evolutionary advantage for the small emus in retaining large eggs and precocial chicks was driven mainly by limited food resources on their islands. Their chicks had to be large enough to feed on seasonably available food, and possibly to develop thermoregulation

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

sufficient for them to deal with cool temperatures, as is the case for mainland emus and kiwis. The large egg-size and smaller clutch of small emus may have been evolutionary steps towards K selection. The precocial juveniles may also have been an adaptation to predation, and while King Island did not have large carnivores, there was a now extirpated population of very large tiger quolls which could have preyed on emu chicks. If the size of the clutch of King Island emus was large, and not the result of more than one female laying eggs in a single nest, this bird must have devoted an amount of energy to reproduction that was proportionally higher than that of mainland birds. Among living ratites, the rhea is morphometrically similar to the King Island emu, and has a similar breeding strategy.

Relationship with humans

The emus of King Island were first recorded by Europeans when a party from the British ship '' Lady Nelson'', led by the Scottish explorer John Murray, visited the island in January 1802. Murray noted on 12 January that "they found feathers of emus and a dead one", but some days later they found "woods full of kangaroo, emus, badgers, etc.", and one emu was "caught by the dog about 50 lbs weight and surprisingly fat." The bird was sporadically mentioned by travellers henceforward, but not in detail. Captain Nicolas Baudin visited King Island later in 1802, during an 1800–04 French expedition to map the coast of Australia. Two ships, '' Le Naturaliste'' and '' Le Géographe'', were part of the expedition, which also brought along naturalists who described the local wildlife. Péron visited King Island and was the last person to record descriptions of the King Island emu from the wild. At one point, Péron and some of his companions became stranded due to storms and took refuge with some sealers. They were served emu meat, which Péron described in favourable terms as tasting halfway "between that of the turkey-cock and that of the young pig". Péron did not report seeing any emus on the island himself, which might explain why he described them as being the size of mainland birds. Instead, most of what is known about the King Island emu today stems from a 33-pointquestionnaire

A questionnaire is a research instrument that consists of a set of questions (or other types of prompts) for the purpose of gathering information from respondents through survey or statistical study. A research questionnaire is typically a mix of ...

that he used to interview Cooper about the bird. In accordance with a request by the authorities for the expedition to bring back useful plants and animals, Péron asked if the emus could be bred and fattened in captivity, and received a variety of cooking recipes. Cooper sold at least three King Island emus to the French expedition, as well as kangaroos

Kangaroos are four marsupials from the family Macropodidae (macropods, meaning "large foot"). In common use the term is used to describe the largest species from this family, the red kangaroo, as well as the antilopine kangaroo, eastern gre ...

and wombats

Wombats are short-legged, muscular quadrupedal marsupials that are native to Australia. They are about in length with small, stubby tails and weigh between . All three of the extant species are members of the family Vombatidae. They are adap ...

. Péron's questionnaire remained unpublished until 1899, and very little was therefore known about the bird in life until then.

Transported specimens

Several emu specimens belonging to the different subspecies were sent to France, both live and dead, as part of the expedition. Some of these exist in European museums today. ''Le Naturaliste'' brought one live specimen and one skin of the mainland emu to France in June 1803. ''Le Géographe'' collected emus from both King and Kangaroo Island, and at least two live King Island individuals, assumed to be a male and female by some sources, were taken to France in March 1804. This ship also brought skins of five juveniles collected from different islands. Two of these skins, of which the provenance is unknown, are presently kept in Paris and Turin; the rest are lost. In addition to rats, cockroaches, and other inconveniences aboard the ships, the emus were incommoded by the rough weather which caused the ships to shake violently; some died as a result, while others had to be force fed so they did not starve to death. In all, ''Le Géographe'' brought 73 live animals of various species back to France. The two individuals brought to France were first kept in captivity in the menagerie ofEmpress Josephine

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother ( e ...

, and were moved to the Jardin des Plantes after a year. The "female" died in April 1822, and its skin is now mounted in the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle of Paris. The "male" died in May 1822, and is preserved as a skeleton in the same museum. A feather of the Paris skin was given to the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) is a museum located in Hobart, Tasmania. The museum was established in 1846, by the Royal Society of Tasmania, the oldest Royal Society outside England.

The TMAG receives 400,000 visitors annually.

...

, the only confirmed feather belonging to this subspecies currently in Australia. The Paris skin contains several bones, but not the pelvis, which is an indicator of sex, so the supposed female identity is unconfirmed. Péron noted that the small emus brought to France were distinct from those of the mainland, but not that they were distinct from each other, or which island each had come from, so their provenance was unknown for more than a century later.

There is also a skeleton in the Royal Zoological Museum, Florence, which it obtained from France in 1833, but was mislabelled as a cassowary

Cassowaries ( tpi, muruk, id, kasuari) are flightless birds of the genus ''Casuarius'' in the order Casuariiformes. They are classified as ratites (flightless birds without a keel on their sternum bones) and are native to the tropical fore ...

and used by students until correctly identified by Italian zoologist Enrico Hillyer Giglioli

Enrico Hillyer Giglioli (13 June 1845 – 16 December 1909) was an Italian zoologist and anthropologist.

Giglioli was born in London and first studied there. He obtained a degree in science at the University of Pisa in 1864 and started to teach ...

in 1900. The skeleton is worn, and several elements are missing, some having been replaced with wooden copies (probably based on those of the Paris skeleton), including the pectoral girdle, the wings, and parts of the legs and skull. Its right metatarsus was damaged during life and had healed incorrectly. It was thought to be a male (and incorrectly that of the Paris skin), but is now known to be a composite of two individuals. A fourth specimen was thought to be kept in the Liverpool Museum

World Museum is a large museum in Liverpool, England which has extensive collections covering archaeology, ethnology and the natural and physical sciences. Special attractions include the Natural History Centre and a planetarium. Entry to the ...

, but it may simply be a juvenile mainland emu. Apart from the King Island emu specimens brought to France, a few are also known to have been brought to mainland Australia in 1803, but their fate is unknown.

Contemporary depictions

Péron's 1807, three-volume account of the expedition, ''Voyage de découverte aux terres Australes'', contains an illustration (plate 36) of "casoars" by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, who was the resident artist during Baudin's voyage. The caption states the birds shown are from "Ile Decrès", the French name for Kangaroo Island, but there is confusion over what is actually depicted. The two adult birds are labelled as a male and female of the same species, surrounded by juveniles. The family-group shown is improbable, since breeding pairs of the mainland emu split up once the male begins incubating the eggs. Lesueur's preparatory sketches also indicate these may have been drawn after the captive birds in Jardin des Plantes, and not wild ones, which would have been harder to observe for extended periods. Pfennigwerth has instead proposed that the larger, light-ruffed "male" was actually drawn after a captive Kangaroo Island emu, that the smaller, dark "female" is a captive King Island emu, that the scenario is fictitious, and the sexes of the birds indeterminable. They may instead only have been assumed to be male and female of the same species due to their difference in size. A crooked claw on the "male" has also been interpreted as evidence that it had lived in captivity, and it may also indicate that the depicted specimen is identical to the Kangaroo Island emu skeleton in Paris, which has a deformed toe. The juvenile on the right may have been based on the Paris skin of an approximately five-month-old emu specimen (from either King or Kangaroo Island), which may in turn be the individual that died on board ''le Geographe'' during rough weather, and was presumably stuffed there by Lesueur himself. The chicks may instead simply have been based on those of mainland emus, as none are known to have been collected.Extinction

The exact cause for the extinction of the King Island emu is unknown. Soon after the bird was discovered, sealers settled on the island because of the abundance of

The exact cause for the extinction of the King Island emu is unknown. Soon after the bird was discovered, sealers settled on the island because of the abundance of elephant seals

Elephant seals are very large, oceangoing earless seals in the genus ''Mirounga''. Both species, the northern elephant seal (''M. angustirostris'') and the southern elephant seal (''M. leonina''), were hunted to the brink of extinction for oil ...

. Péron's interview with Cooper suggested that they likely contributed to the demise of the bird by hunting it, and perhaps by starting fires. Péron described how dogs were purpose-trained to hunt down the emus; Cooper even claimed to have killed no fewer than 300 emus himself. Cooper had been on the island for six months, which suggests he killed 50 birds a month. His group of sealers consisted of eleven men as well as his wife, and they alone may have killed 3,600 emus by the time Péron visited them.

Péron explained that the sealers consumed an enormous quantity of meat, and that their dogs killed several animals each day. He also observed such hunting dogs being released on Kangaroo Island, and mused that they might wipe out the entire population of kangaroos there in some years, but he did not express the same sentiment about the emus of King Island. Based on the possibly restricted distribution of the emu to coastal areas, Hume and colleagues suggested this might explain their rapid disappearance, as these areas were easily accessible to sealers. Natural fires may also have played a role. It is probable that the two captive birds in France, which died in 1822, outlived their wild fellows on King Island, and were therefore the last of their kind. Though Péron stated King Island "swarmed" with emus in 1802, they may have become extinct in the wild as early as 1805. They were certainly extinct by 1836, when some English settlers arrived on the island. Elephant seals disappeared from the island around 1819 due to over-hunting.

In 1967, when the King Island emu was still thought to be only known from prehistoric remains, the American ornithologist James Greenway questioned whether they could have been exterminated by a few natives, and speculated that fires started by prehistoric men or lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an avera ...

may have been responsible. At this time, the mainland emu was also threatened by overhunting, and Greenway cautioned that it could end up sharing the fate of its island relatives if no measures were taken in time.

References

{{Taxonbar, from1=Q27600963, from2=Q903601 King Island emu † Extinct birds of Australia Extinct flightless birds King Island (Tasmania) Bird extinctions since 1500 Species made extinct by human activities King Island emu