Kievan Rus' on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ;

Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encompassing a variety of polities and peoples, including East Slavic, Norse, and Finnic, it was ruled by the Rurik dynasty, founded by the

During its existence, Kievan Rusʹ was known as the "land of the Rus" ( orv, ро́усьскаѧ землѧ, from the ethnonym ;

During its existence, Kievan Rusʹ was known as the "land of the Rus" ( orv, ро́усьскаѧ землѧ, from the ethnonym ;

Глава I

/

Древняя Русь на международных путях: Междисциплинарные очерки культурных, торговых, политических связей IX—XII вв.

— М.: Языки русской культуры, 2001. — c. 40, 42—45, 49—50. — . Various etymologies have been proposed, including , the

The Viking World

', ed. by Stefan Brink and Neil Price (Abingdon: Routledge, 2008), pp. 4-10 (pp. 6–7). The name ''Rusʹ'' would then have the same origin as the Finnish and Estonian names for Sweden: ''Ruotsi'' and ''Rootsi''."Russ, adj. and n." OED Online, Oxford University Press, June 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/169069. Accessed 12 January 2021. The term ''Kievan Rusʹ'' (russian: Ки́евская Русь, translit=Kiyevskaya Rus) was coined in the 19th century in

There was once controversy over whether the Rusʹ were

There was once controversy over whether the Rusʹ were

A Military History of Russia: From Ivan the Terrible to the war in Chechnya

' (2006), pp. 2–3. Nevertheless, the close connection between the Rusʹ and the Norse is confirmed both by extensive Scandinavian settlement in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine and by Slavic influences in the Swedish language. Though the debate over the origin of the Rusʹ remains politically charged, there is broad agreement that if the proto-Rusʹ were indeed originally Norse, they were quickly nativized, adopting Slavic languages and other cultural practices. This position, roughly representing a scholarly consensus (at least outside of nationalist historiography), was summarized by the historian, F. Donald Logan, "in 839, the Rus were Swedes; in 1043 the Rus were Slavs". Recent scholarship has attempted to move past the narrow and politicized debate on origins, to focus on how and why assimilation took place so quickly. Some modern DNA testing also points to Viking origins, not only of some of the early Rusʹ princely family and/or their retinues, but also links to possible brethren from neighboring countries like

According to the ''Primary Chronicle'', the territories of the East Slavs in the 9th century were divided between the Varangians and the Khazars. The Varangians are first mentioned imposing tribute from Slavic and Finnic tribes in 859. In 862, the Finnic and Slavic tribes in the area of Novgorod rebelled against the Varangians, driving them "back beyond the sea and, refusing them further tribute, set out to govern themselves." The tribes had no laws, however, and soon began to make war with one another, prompting them to invite the Varangians back to rule them and bring peace to the region:

The three brothers— Rurik, Sineus and Truvor—established themselves in Novgorod, Beloozero and Izborsk, respectively. Two of the brothers died, and Rurik became the sole ruler of the territory and progenitor of the Rurik dynasty. A short time later, two of Rurik's men,

According to the ''Primary Chronicle'', the territories of the East Slavs in the 9th century were divided between the Varangians and the Khazars. The Varangians are first mentioned imposing tribute from Slavic and Finnic tribes in 859. In 862, the Finnic and Slavic tribes in the area of Novgorod rebelled against the Varangians, driving them "back beyond the sea and, refusing them further tribute, set out to govern themselves." The tribes had no laws, however, and soon began to make war with one another, prompting them to invite the Varangians back to rule them and bring peace to the region:

The three brothers— Rurik, Sineus and Truvor—established themselves in Novgorod, Beloozero and Izborsk, respectively. Two of the brothers died, and Rurik became the sole ruler of the territory and progenitor of the Rurik dynasty. A short time later, two of Rurik's men,

"The First East Slavic State"

''A Companion to Russian History'' (Abbott Gleason, ed., 2009), p. 37Primary Chronicle

, p.8. The Chronicle reports that Askold and Dir continued to Constantinople with a navy to attack the city in 863–66, catching the Byzantines by surprise and ravaging the surrounding area, though other accounts date the attack in 860. Patriarch Photius vividly describes the "universal" devastation of the suburbs and nearby islands, and another account further details the destruction and slaughter of the invasion. The Rusʹ turned back before attacking the city itself, due either to a storm dispersing their boats, the return of the Emperor, or in a later account, due to a miracle after a ceremonial appeal by the Patriarch and the Emperor to the Virgin. The attack was the first encounter between the Rusʹ and Byzantines and led the Patriarch to send missionaries north to engage and attempt to convert the Rusʹ and the Slavs.Majeska (2009)

p.52

Dimitri Obolensky, ''Byzantium and the Slavs'' (1994)

p.245

Rurik led the Rusʹ until his death in about 879, bequeathing his kingdom to his kinsman, Prince Oleg, as regent for his young son, Igor. In 880–82, Oleg led a military force south along the

Rurik led the Rusʹ until his death in about 879, bequeathing his kingdom to his kinsman, Prince Oleg, as regent for his young son, Igor. In 880–82, Oleg led a military force south along the

p. 37

and because it controlled three main trade routes of

p. 47

Trade from the Baltic also moved south on a network of rivers and short portages along the Dnieper known as the " route from the Varangians to the Greeks," continuing to the Black Sea and on to Constantinople.Martin (2009)

pp. 40, 47. Kiev was a central outpost along the Dnieper route and a hub with the east–west overland trade route between the Khazars and the Germanic lands of Central Europe. and may have been a staging post for Radhanite Jewish traders between Western Europe, Itil and China. These commercial connections enriched Rusʹ merchants and princes, funding military forces and the construction of churches, palaces, fortifications, and further towns. Demand for luxury goods fostered production of expensive jewelry and religious wares, allowing their export, and an advanced credit and money-lending system may have also been in place.

p. 62

Magocsi (2010)

p.66

The Khazars dominated trade from the Volga-Don steppes to the eastern Crimea and the northern Caucasus during the 8th century during an era historians call the ' Pax Khazarica', trading and frequently allying with the Byzantine Empire against Persians and Arabs. In the late 8th century, the collapse of the Göktürk Khaganate led the Magyars and the Pechenegs, The Byzantine Empire was able to take advantage of the turmoil to expand its political influence and commercial relationships, first with the Khazars and later with the Rusʹ and other steppe groups. The Byzantines established the Theme of Cherson, formally known as Klimata, in the Crimea in the 830s to defend against raids by the Rusʹ and to protect vital grain shipments supplying Constantinople. Cherson also served as a key diplomatic link with the Khazars and others on the steppe, and it became the centre of Black Sea commerce. The Byzantines also helped the Khazars build a fortress at Sarkel on the Don river to protect their northwest frontier against incursions by the Turkic migrants and the Rusʹ, and to control caravan trade routes and the portage between the Don and Volga rivers.

The expansion of the Rusʹ put further military and economic pressure on the Khazars, depriving them of territory, tributaries and trade. In around 890, Oleg waged an indecisive war in the lands of the lower

The Byzantine Empire was able to take advantage of the turmoil to expand its political influence and commercial relationships, first with the Khazars and later with the Rusʹ and other steppe groups. The Byzantines established the Theme of Cherson, formally known as Klimata, in the Crimea in the 830s to defend against raids by the Rusʹ and to protect vital grain shipments supplying Constantinople. Cherson also served as a key diplomatic link with the Khazars and others on the steppe, and it became the centre of Black Sea commerce. The Byzantines also helped the Khazars build a fortress at Sarkel on the Don river to protect their northwest frontier against incursions by the Turkic migrants and the Rusʹ, and to control caravan trade routes and the portage between the Don and Volga rivers.

The expansion of the Rusʹ put further military and economic pressure on the Khazars, depriving them of territory, tributaries and trade. In around 890, Oleg waged an indecisive war in the lands of the lower

pp. 138–139

Spanei (2009)

pp. 66, 70

Boxed in, the Magyars were forced to migrate further west across the Carpathian Mountains into the Hungarian plain, depriving the Khazars of an important ally and a buffer from the Rusʹ. The migration of the Magyars allowed Rusʹ access to the Black Sea, and they soon launched excursions into Khazar territory along the sea coast, up the Don river, and into the lower Volga region. The Rusʹ were raiding and plundering into the Caspian Sea region from 864, with the first large-scale expedition in 913, when they extensively raided Baku, Gilan, Mazandaran and penetrated into the Caucasus. As the 10th century progressed, the Khazars were no longer able to command tribute from the Volga Bulgars, and their relationship with the Byzantines deteriorated, as Byzantium increasingly allied with the Pechenegs against them. The Pechenegs were thus secure to raid the lands of the Khazars from their base between the Volga and

p. 17

The lucrative Rusʹ trade with the Byzantine Empire had to pass through Pecheneg-controlled territory, so the need for generally peaceful relations was essential. Nevertheless, while the Primary Chronicle reports the Pechenegs entering Rusʹ territory in 915 and then making peace, they were waging war with one another again in 920.Magocsi (2010)

p. 67

Pechenegs are reported assisting the Rusʹ in later campaigns against the Byzantines, yet allied with the Byzantines against the Rusʹ at other times.

After the Rusʹ attack on Constantinople in 860, the Byzantine Patriarch Photius sent missionaries north to convert the Rusʹ and the Slavs to Christianity. Prince

After the Rusʹ attack on Constantinople in 860, the Byzantine Patriarch Photius sent missionaries north to convert the Rusʹ and the Slavs to Christianity. Prince

p.22

The importance of this trade relationship led to military action when disputes arose. The Primary Chronicle reports that the Rusʹ attacked Constantinople again in 907, probably to secure trade access. The Chronicle glorifies the military prowess and shrewdness of Oleg, an account imbued with legendary detail. Byzantine sources do not mention the attack, but a pair of treaties in 907 and 911 set forth a trade agreement with the Rusʹ, the terms suggesting pressure on the Byzantines, who granted the Rusʹ quarters and supplies for their merchants and tax-free trading privileges in Constantinople. The Chronicle provides a mythic tale of Oleg's death. A sorcerer prophesies that the death of the In 941, Igor led another major Rusʹ attack on Constantinople, probably over trading rights again. A navy of 10,000 vessels, including Pecheneg allies, landed on the Bithynian coast and devastated the Asiatic shore of the Bosphorus.Ostrogorski, p.277 The attack was well timed, perhaps due to intelligence, as the Byzantine fleet was occupied with the Arabs in the Mediterranean, and the bulk of its army was stationed in the east. The Rusʹ burned towns, churches and monasteries, butchering the people and amassing booty. The emperor arranged for a small group of retired ships to be outfitted with Greek fire throwers and sent them out to meet the Rusʹ, luring them into surrounding the contingent before unleashing the Greek fire.Logan, p.193.

In 941, Igor led another major Rusʹ attack on Constantinople, probably over trading rights again. A navy of 10,000 vessels, including Pecheneg allies, landed on the Bithynian coast and devastated the Asiatic shore of the Bosphorus.Ostrogorski, p.277 The attack was well timed, perhaps due to intelligence, as the Byzantine fleet was occupied with the Arabs in the Mediterranean, and the bulk of its army was stationed in the east. The Rusʹ burned towns, churches and monasteries, butchering the people and amassing booty. The emperor arranged for a small group of retired ships to be outfitted with Greek fire throwers and sent them out to meet the Rusʹ, luring them into surrounding the contingent before unleashing the Greek fire.Logan, p.193.

Following the death of Grand Prince Igor in 945, his wife Olga ruled as

Following the death of Grand Prince Igor in 945, his wife Olga ruled as

Vladimir's choice of Eastern Christianity may also have reflected his close personal ties with Constantinople, which dominated the Black Sea and hence trade on Kiev's most vital commercial route, the Dnieper River. Adherence to the

Vladimir's choice of Eastern Christianity may also have reflected his close personal ties with Constantinople, which dominated the Black Sea and hence trade on Kiev's most vital commercial route, the Dnieper River. Adherence to the

Yaroslav, known as "the Wise", struggled for power with his brothers. A son of

Yaroslav, known as "the Wise", struggled for power with his brothers. A son of

The gradual disintegration of the Kievan Rusʹ began in the 11th century, after the death of

The gradual disintegration of the Kievan Rusʹ began in the 11th century, after the death of  The most prominent struggle for power was the conflict that erupted after the death of Yaroslav the Wise. The rival

The most prominent struggle for power was the conflict that erupted after the death of Yaroslav the Wise. The rival

In the northeast, Slavs from the Kievan region colonized the territory that later would become the Grand Duchy of Moscow by subjugating and merging with the Finnic tribes already occupying the area. The city of

In the northeast, Slavs from the Kievan region colonized the territory that later would become the Grand Duchy of Moscow by subjugating and merging with the Finnic tribes already occupying the area. The city of

Following the Mongol invasion of

Following the Mongol invasion of

Due to the expansion of trade and its geographical proximity, Kiev became the most important trade centre and chief among the communes; therefore the leader of Kiev gained political "control" over the surrounding areas. This

Due to the expansion of trade and its geographical proximity, Kiev became the most important trade centre and chief among the communes; therefore the leader of Kiev gained political "control" over the surrounding areas. This

Kievan Rusʹ, although sparsely populated compared to Western Europe, was not only the largest contemporary European state in terms of area but also culturally advanced.

Literacy in Kiev, Novgorod and other large cities was high; as

Kievan Rusʹ, although sparsely populated compared to Western Europe, was not only the largest contemporary European state in terms of area but also culturally advanced.

Literacy in Kiev, Novgorod and other large cities was high; as

The Mongol Empire invaded Kievan Rusʹ in the 13th century, destroying numerous cities, including

The Mongol Empire invaded Kievan Rusʹ in the 13th century, destroying numerous cities, including

Byzantium quickly became the main trading and cultural partner for Kiev, but relations were not always friendly. The most serious conflict between the two powers was the war of 968–971 in Bulgaria, but several Rusʹ raiding expeditions against the Byzantine cities of the Black Sea coast and Constantinople itself are also recorded. Although most were repulsed, they were concluded by trade treaties that were generally favourable to the Rusʹ.

Rusʹ-Byzantine relations became closer following the marriage of the ''

Byzantium quickly became the main trading and cultural partner for Kiev, but relations were not always friendly. The most serious conflict between the two powers was the war of 968–971 in Bulgaria, but several Rusʹ raiding expeditions against the Byzantine cities of the Black Sea coast and Constantinople itself are also recorded. Although most were repulsed, they were concluded by trade treaties that were generally favourable to the Rusʹ.

Rusʹ-Byzantine relations became closer following the marriage of the ''

In 988, the Christian Church in Rusʹ territorially fell under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople after it was officially adopted as the state religion. According to several chronicles after that date the predominant cult of Slavic paganism was persecuted.

The exact date of creation of the Kiev Metropolis is uncertain, as well as its first church leader. It is generally considered that the first head was Michael I of Kiev; however, some sources claim it to be Leontiy, who is often placed after Michael or Anastas Chersonesos, who became the first bishop of the

In 988, the Christian Church in Rusʹ territorially fell under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople after it was officially adopted as the state religion. According to several chronicles after that date the predominant cult of Slavic paganism was persecuted.

The exact date of creation of the Kiev Metropolis is uncertain, as well as its first church leader. It is generally considered that the first head was Michael I of Kiev; however, some sources claim it to be Leontiy, who is often placed after Michael or Anastas Chersonesos, who became the first bishop of the

File:CHODZKO(1861) CARTE DES PAYS SLAVO-POLONAIS AUX VIII ET IX SIECLE.jpg, Map of 8th- to 9th-century Rusʹ by Leonard Chodzko (1861)

File:Polska Rosja Skandynawia w IX w.jpg, Map of 9th-century Rusʹ by Antoine Philippe Houze (1844)

File:LEROY-BEAULIEU(1893) p1.097 RUSSIA IN THE 9th CENTURY.jpg, Map of 9th-century Rusʹ by F. S. Weller (1893)

File:Europe 1000.jpg, Map of Rusʹ in Europe in 1000 (1911)

File:Shepherd-c-066-067.jpg, Map of Rusʹ in 1097 (1911)

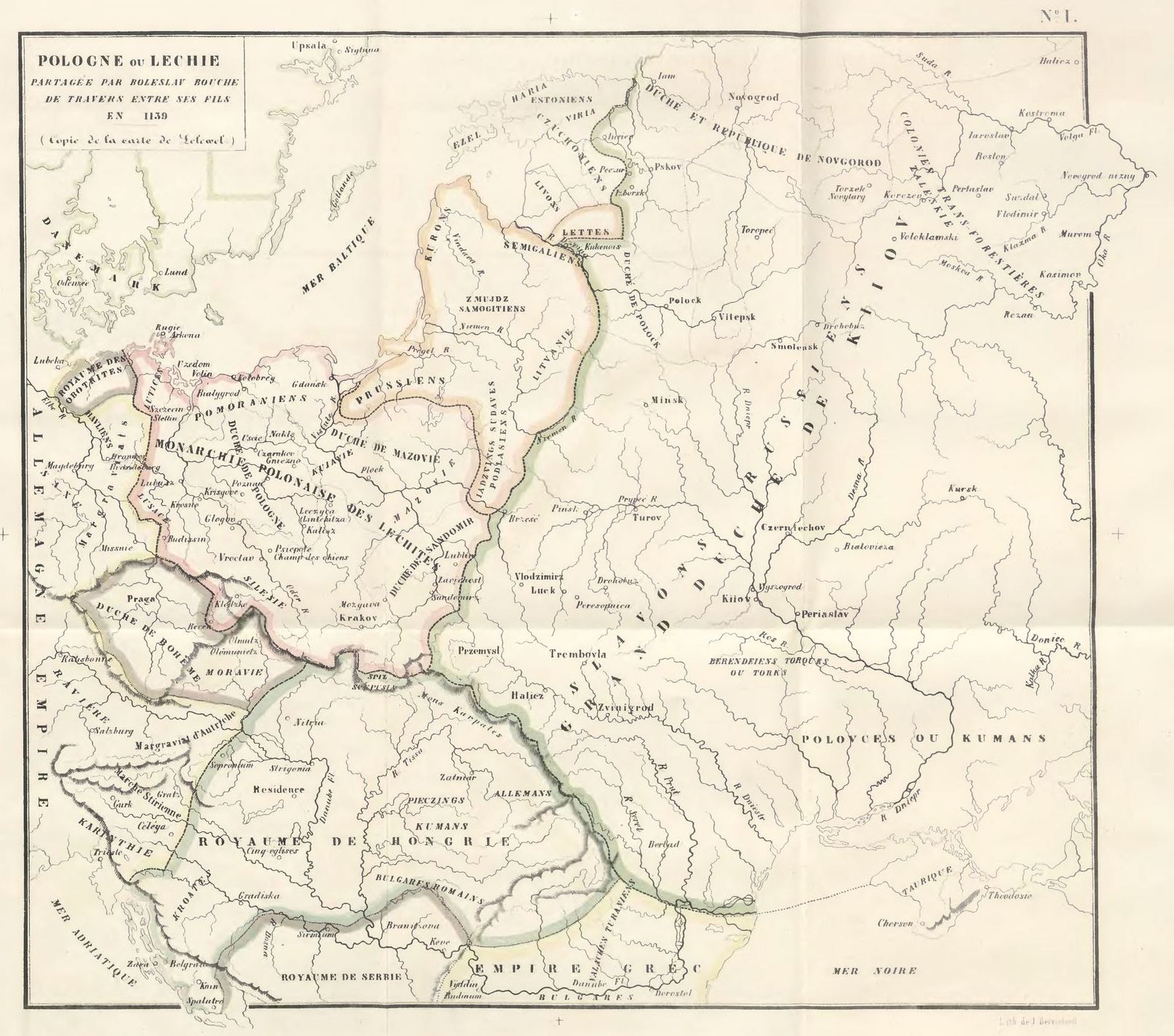

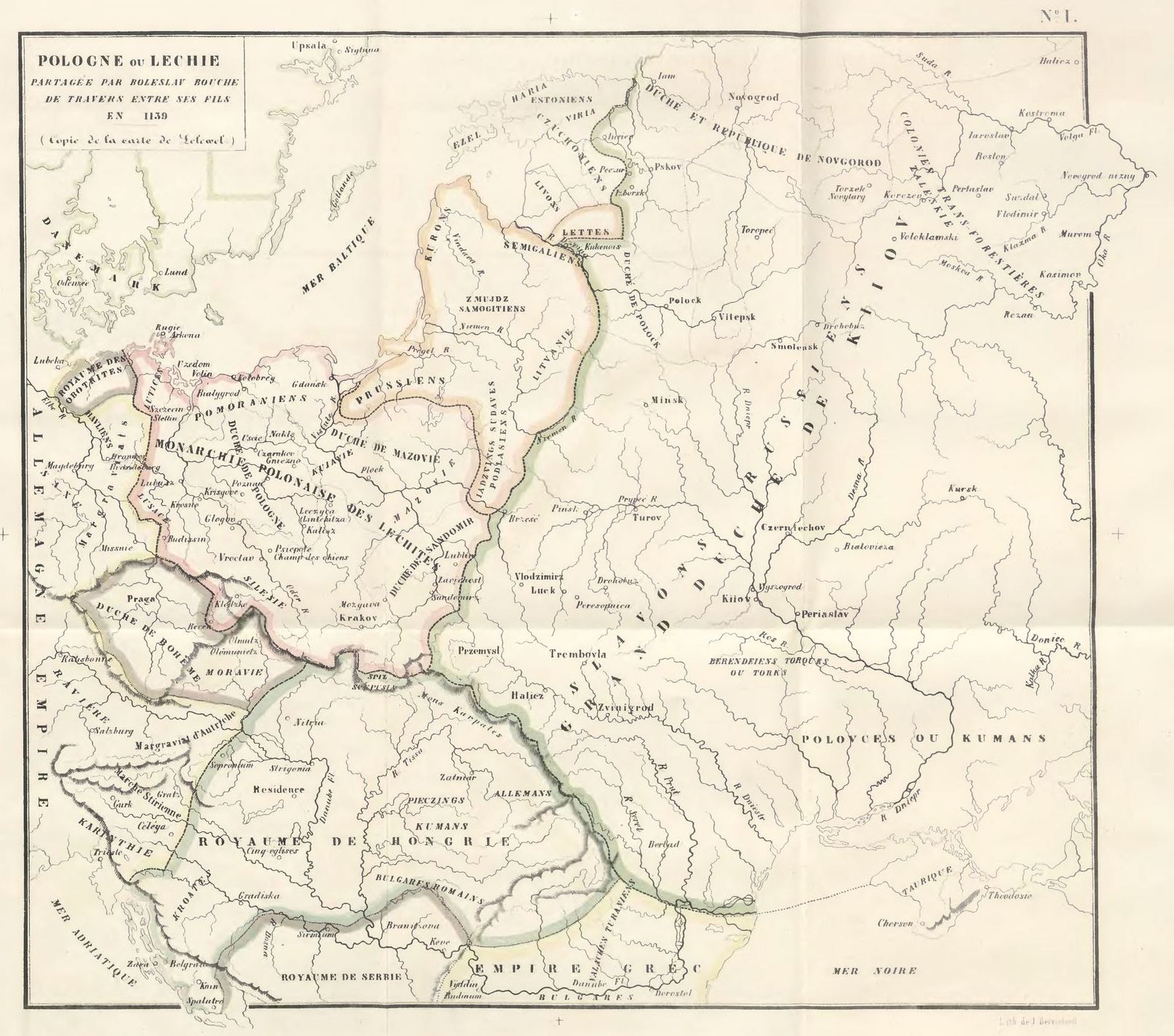

File:Europe-1139.jpg, Map of 1139 by Joachim Lelewel (1865)

File:Центры Руси по Идриси.jpg, Fragment of the 1154 Tabula Rogeriana by

Russia

Stephen Velychenko. New Wine Old Bottle. Ukrainian History, Muscovite /Russian Imperial Myths and the Cambridge History of Russia

*

Ancient Rus: trade and crafts

Chronology of Kievan Rusʹ 859–1240.

{{Authority control States and territories established in the 870s States and territories disestablished in 1240 882 establishments 1240 disestablishments in Europe Former countries in Europe Former Slavic countries Medieval Belarus Medieval Russia Medieval Ukraine 9th-century establishments in Russia Historical regions Former countries

Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlemen ...

: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of Russia'' (Penguin, 1995), p.14–16.Kievan RusEncyclopædia Britannica Online. Encompassing a variety of polities and peoples, including East Slavic, Norse, and Finnic, it was ruled by the Rurik dynasty, founded by the

Varangian

The Varangians (; non, Væringjar; gkm, Βάραγγοι, ''Várangoi'';Varangian

" Online Etymo ...

prince Rurik. The modern nations of " Online Etymo ...

Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

, and Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

all claim Kievan Rusʹ as their cultural ancestor, with Belarus and Russia deriving their names from it. At its greatest extent in the mid-11th century, Kievan Rusʹ stretched from the White Sea in the north to the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

in the south and from the headwaters

The headwaters of a river or stream is the farthest place in that river or stream from its estuary or downstream confluence with another river, as measured along the course of the river. It is also known as a river's source.

Definition

The ...

of the Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

in the west to the Taman Peninsula

The Taman Peninsula (russian: Тама́нский полуо́стров, ''Tamanskiy poluostrov'') is a peninsula in the present-day Krasnodar Krai of Russia, which borders the Sea of Azov to the North, the Strait of Kerch to the West and the ...

in the east, uniting the East Slavic tribes.

According to the '' Primary Chronicle'', the first ruler to start uniting East Slavic lands into what would become Kievan Rusʹ was Prince Oleg (879–912). He extended his control from Novgorod south along the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

river valley to protect trade from Khazar

The Khazars ; he, כּוּזָרִים, Kūzārīm; la, Gazari, or ; zh, 突厥曷薩 ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a semi-nomadic Turkic people that in the late 6th-century CE established a major commercial empire coverin ...

incursions from the east, and took control of the city of Kiev. Sviatoslav I (943–972) achieved the first major territorial expansion of the state, fighting a war of conquest against the Khazars

The Khazars ; he, כּוּזָרִים, Kūzārīm; la, Gazari, or ; zh, 突厥曷薩 ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a semi-nomadic Turkic people that in the late 6th-century CE established a major commercial empire coverin ...

. Vladimir the Great

Vladimir I Sviatoslavich or Volodymyr I Sviatoslavych ( orv, Володимѣръ Свѧтославичь, ''Volodiměrъ Svętoslavičь'';, ''Uladzimir'', russian: Владимир, ''Vladimir'', uk, Володимир, ''Volodymyr''. Se ...

(980–1015) introduced Christianity with his own baptism and, by decree, extended it to all inhabitants of Kiev and beyond. Kievan Rusʹ reached its greatest extent under Yaroslav the Wise

Yaroslav the Wise or Yaroslav I Vladimirovich; russian: Ярослав Мудрый, ; uk, Ярослав Мудрий; non, Jarizleifr Valdamarsson; la, Iaroslaus Sapiens () was the Grand Prince of Kiev from 1019 until his death. He was al ...

(1019–1054); his sons assembled and issued its first written legal code, the '' Russkaya Pravda'', shortly after his death.Bushkovitch, Paul. ''A Concise History of Russia''. Cambridge University Press. 2011.

The state began to decline in the late 11th century, gradually disintegrating into various rival regional powers throughout the 12th century. It was further weakened by external factors, such as the decline of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire experienced several cycles of growth and decay over the course of nearly a thousand years, including major losses during the Early Muslim conquests of the 7th century. However, modern historians generally agree that the star ...

, its major economic partner, and the accompanying diminution of trade routes

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over bodies of water. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a sing ...

through its territory. It finally fell to the Mongol invasion in the mid-13th century, though the Rurik dynasty would continue to rule until the death of Feodor I of Russia

Fyodor I Ivanovich (russian: Фёдор I Иванович) or Feodor I Ioannovich (russian: Феодор I Иоаннович; 31 May 1557 – 17 January (NS) 1598), also known as Feodor the Bellringer (russian: Феодор Звонарь), ...

in 1598.

Name

During its existence, Kievan Rusʹ was known as the "land of the Rus" ( orv, ро́усьскаѧ землѧ, from the ethnonym ;

During its existence, Kievan Rusʹ was known as the "land of the Rus" ( orv, ро́усьскаѧ землѧ, from the ethnonym ; Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

: ; Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

: '), in Greek as , in Old French as , in Latin as or (with local German spelling variants ''Ruscia'' and ''Ruzzia''), and from the 12th century also as or . ''Назаренко А. В.'Глава I

/

Древняя Русь на международных путях: Междисциплинарные очерки культурных, торговых, политических связей IX—XII вв.

— М.: Языки русской культуры, 2001. — c. 40, 42—45, 49—50. — . Various etymologies have been proposed, including , the

Finnish

Finnish may refer to:

* Something or someone from, or related to Finland

* Culture of Finland

* Finnish people or Finns, the primary ethnic group in Finland

* Finnish language, the national language of the Finnish people

* Finnish cuisine

See also ...

designation for Sweden or ''Ros'', a tribe from the middle Dnieper valley region.

According to the prevalent theory, the name ''Rusʹ'', like the Proto-Finnic name for Sweden (''*rootsi''), is derived from an Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlemen ...

term for 'men who row' (''rods-'') because rowing was the main method of navigating the rivers of Eastern Europe, and could be linked to the Swedish coastal area of Roslagen

Roslagen is the name of the coastal areas of Uppland province in Sweden, which also constitutes the northern part of the Stockholm archipelago.

Historically, it was the name for all the coastal areas of the Baltic Sea, including the eastern p ...

(''Rus-law'') or ''Roden'', as it was known in earlier times.Stefan Brink, 'Who were the Vikings?', in The Viking World

', ed. by Stefan Brink and Neil Price (Abingdon: Routledge, 2008), pp. 4-10 (pp. 6–7). The name ''Rusʹ'' would then have the same origin as the Finnish and Estonian names for Sweden: ''Ruotsi'' and ''Rootsi''."Russ, adj. and n." OED Online, Oxford University Press, June 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/169069. Accessed 12 January 2021. The term ''Kievan Rusʹ'' (russian: Ки́евская Русь, translit=Kiyevskaya Rus) was coined in the 19th century in

Russian historiography

This list of Russian historians includes the famous historians, as well as archaeologists, paleographers, genealogists and other representatives of auxiliary historical disciplines from the Russian Federation, the Soviet Union, the Russian Empire ...

to refer to the period when the centre was in Kiev. In the 19th century it also appeared in uk, Ки́ївська Русь, translit=Kyivska Rus, translit-std=ungegn. In English, the term was introduced in the early 20th century, when it was found in the 1913 English translation of Vasily Klyuchevsky

Vasily Osipovich Klyuchevsky (russian: Василий Осипович Ключевский; in Voskresnskoye Village, Penza Governorate, Russia – , Moscow) was a leading Russian Imperial historian of the late imperial period. Also, he addres ...

's ''A History of Russia'', to distinguish the early polity from successor states, which were also named ''Rusʹ''. The variant ''Kyivan Rusʹ'' appeared in English-language scholarship by the 1950s. Later, the Russian term was rendered into be, Кіеўская Русь, translit=Kiyewskaya Rus’, translit-std=bgn/pcgn or and rue, Київска Русь, translit=Kyïvska Rus′, translit-std=ala-lc.

The historically accurate but rare spelling ''Kyevan Rusʹ'', based on Old East Slavic () 'Kyiv', is also occasionally seen.

History

Origin

Prior to the emergence of Kievan Rusʹ in the 9th century, most of the area north of theBlack Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

, which roughly overlaps with modern-day Ukraine and Belarus, was primarily populated by eastern Slavic tribes. In the northern region around Novgorod were the Ilmen Slavs and neighboring Krivichi, who occupied territories surrounding the headwaters of the West Dvina, Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

and Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchm ...

rivers. To their north, in the Ladoga and Karelia regions, were the Finnic Chud tribe. In the south, in the area around Kiev, were the Poliane, a group of Slavicized

Slavicisation or Slavicization, is the acculturation of something Slavic into a non-Slavic culture, cuisine, region, or nation. To a lesser degree, it also means acculturation or adoption of something non-Slavic into Slavic culture or terms. Th ...

tribes with Iranian

Iranian may refer to:

* Iran, a sovereign state

* Iranian peoples, the speakers of the Iranian languages. The term Iranic peoples is also used for this term to distinguish the pan ethnic term from Iranian, used for the people of Iran

* Iranian lan ...

origins, the Drevliane to the west of the Dnieper, and the Severiane to the east. To their north and east were the Vyatichi

The Vyatichs or more properly Vyatichi or Viatichi (russian: вя́тичи) were a native tribe of Early East Slavs who inhabited regions around the Oka, Moskva and Don rivers.

The Vyatichi had for a long time no princes, but the social struc ...

, and to their south was forested land settled by Slav farmers, giving way to steppelands populated by nomadic herdsmen.

There was once controversy over whether the Rusʹ were

There was once controversy over whether the Rusʹ were Varangians

The Varangians (; non, Væringjar; gkm, Βάραγγοι, ''Várangoi'';Varangian

" Online Etymo ...

or Slavs, however, more recently scholarly attention has focused more on debating how quickly an ancestrally Norse people assimilated into Slavic culture. "The controversies over the nature of the Rus and the origins of the Russian state have bedevilled Viking studies, and indeed Russian history, for well over a century. It is historically certain that the Rus were Swedes. The evidence is incontrovertible, and that a debate still lingers at some levels of historical writing is clear evidence of the holding power of received notions. The debate over this issue – futile, embittered, tendentious, doctrinaire – served to obscure the most serious and genuine historical problem which remains: the assimilation of these Viking Rus into the Slavic people among whom they lived. The principal historical question is not whether the Rus were Scandinavians or Slavs, but, rather, how quickly these Scandinavian Rus became absorbed into Slavic life and culture." This uncertainty is due largely to a paucity of contemporary sources. Attempts to address this question instead rely on archaeological evidence, the accounts of foreign observers, and legends and literature from centuries later. To some extent the controversy is related to the foundation myths of modern states in the region. This often unfruitful debate over origins has periodically devolved into competing nationalist narratives of dubious scholarly value being promoted directly by various government bodies, in a number of states. This was seen in the Stalinist period, when Soviet historiography sought to distance the Rusʹ from any connection to Germanic tribes, in an effort to dispel Nazi propaganda claiming the Russian state owed its existence and origins to the supposedly racially superior Norse tribes. More recently, in the context of resurgent nationalism in post-Soviet states, Anglophone scholarship has analyzed renewed efforts to use this debate to create ethno-nationalist foundation stories, with governments sometimes directly involved in the project. Conferences and publications questioning the Norse origins of the Rusʹ have been supported directly by state policy in some cases, and the resultant foundation myths have been included in some school textbooks in Russia.

While Varangians were Norse traders and " Online Etymo ...

Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and ...

, some Russian and Ukrainian nationalist historians argue that the Rusʹ were themselves Slavs (see Anti-Normanism). Normanist theories focus on the earliest written source for the East Slavs

The East Slavs are the most populous subgroup of the Slavs. They speak the East Slavic languages, and formed the majority of the population of the medieval state Kievan Rus', which they claim as their cultural ancestor.John Channon & Robert H ...

, the '' Primary Chronicle'', which was produced in the 12th century. Nationalist accounts on the other hand have suggested that the Rusʹ were present before the arrival of the Varangians, noting that only a handful of Scandinavian words can be found in Russian and that Scandinavian names in the early chronicles were soon replaced by Slavic names. David R. Stone, A Military History of Russia: From Ivan the Terrible to the war in Chechnya

' (2006), pp. 2–3. Nevertheless, the close connection between the Rusʹ and the Norse is confirmed both by extensive Scandinavian settlement in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine and by Slavic influences in the Swedish language. Though the debate over the origin of the Rusʹ remains politically charged, there is broad agreement that if the proto-Rusʹ were indeed originally Norse, they were quickly nativized, adopting Slavic languages and other cultural practices. This position, roughly representing a scholarly consensus (at least outside of nationalist historiography), was summarized by the historian, F. Donald Logan, "in 839, the Rus were Swedes; in 1043 the Rus were Slavs". Recent scholarship has attempted to move past the narrow and politicized debate on origins, to focus on how and why assimilation took place so quickly. Some modern DNA testing also points to Viking origins, not only of some of the early Rusʹ princely family and/or their retinues, but also links to possible brethren from neighboring countries like

Sviatopolk I of Kiev

Sviatopolk I Vladimirovich (''Sviatopolk the Accursed'', the ''Accursed Prince''; orv, Свѧтоплъкъ, translit=Svętoplŭkŭ; russian: Святополк Окаянный; uk, Святополк Окаянний; c. 980 – 1019) was the ...

.

Ahmad ibn Fadlan, an Arab traveler during the 10th century, provided one of the earliest written descriptions of the Rusʹ: "They are as tall as a date palm, blond and ruddy, so that they do not need to wear a tunic nor a cloak; rather the men among them wear garments that only cover half of his body and leaves one of his hands free." Liutprand of Cremona

Liutprand, also Liudprand, Liuprand, Lioutio, Liucius, Liuzo, and Lioutsios (c. 920 – 972),"LIUTPRAND OF CREMONA" in '' The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium'', Oxford University Press, New York & Oxford, 1991, p. 1241. was a historian, diplomat, ...

, who was twice an envoy to the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

court (949 and 968), identifies the "Russi" with the Norse ("the Russi, whom we call Norsemen by another name") but explains the name as a Greek term referring to their physical traits ("A certain people made up of a part of the Norse, whom the Greeks call ..the Russi on account of their physical features, we designate as Norsemen because of the location of their origin."). Leo the Deacon, a 10th-century Byzantine historian and chronicler, refers to the Rusʹ as "Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

" and notes that they tended to adopt Greek rituals and customs. But 'Scythians' in Greek parlance is used predominantly as a generic term for nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

s.

Invitation of the Varangians

According to the ''Primary Chronicle'', the territories of the East Slavs in the 9th century were divided between the Varangians and the Khazars. The Varangians are first mentioned imposing tribute from Slavic and Finnic tribes in 859. In 862, the Finnic and Slavic tribes in the area of Novgorod rebelled against the Varangians, driving them "back beyond the sea and, refusing them further tribute, set out to govern themselves." The tribes had no laws, however, and soon began to make war with one another, prompting them to invite the Varangians back to rule them and bring peace to the region:

The three brothers— Rurik, Sineus and Truvor—established themselves in Novgorod, Beloozero and Izborsk, respectively. Two of the brothers died, and Rurik became the sole ruler of the territory and progenitor of the Rurik dynasty. A short time later, two of Rurik's men,

According to the ''Primary Chronicle'', the territories of the East Slavs in the 9th century were divided between the Varangians and the Khazars. The Varangians are first mentioned imposing tribute from Slavic and Finnic tribes in 859. In 862, the Finnic and Slavic tribes in the area of Novgorod rebelled against the Varangians, driving them "back beyond the sea and, refusing them further tribute, set out to govern themselves." The tribes had no laws, however, and soon began to make war with one another, prompting them to invite the Varangians back to rule them and bring peace to the region:

The three brothers— Rurik, Sineus and Truvor—established themselves in Novgorod, Beloozero and Izborsk, respectively. Two of the brothers died, and Rurik became the sole ruler of the territory and progenitor of the Rurik dynasty. A short time later, two of Rurik's men, Askold and Dir

Askold and Dir (''Haskuldr'' or ''Hǫskuldr'' and ''Dyr'' or ''Djur'' in Old Norse; died in 882), mentioned in both the Primary Chronicle and the Nikon Chronicle, were the earliest known ''purportedly Norse'' rulers of Kiev.

Primary Chronicle ...

, asked him for permission to go to Tsargrad (Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

). On their way south, they discovered "a small city on a hill," Kiev, captured it and the surrounding country from the Khazars, populated the region with more Varangians, and "established their dominion over the country of the Polyanians."Janet Martin"The First East Slavic State"

''A Companion to Russian History'' (Abbott Gleason, ed., 2009), p. 37Primary Chronicle

, p.8. The Chronicle reports that Askold and Dir continued to Constantinople with a navy to attack the city in 863–66, catching the Byzantines by surprise and ravaging the surrounding area, though other accounts date the attack in 860. Patriarch Photius vividly describes the "universal" devastation of the suburbs and nearby islands, and another account further details the destruction and slaughter of the invasion. The Rusʹ turned back before attacking the city itself, due either to a storm dispersing their boats, the return of the Emperor, or in a later account, due to a miracle after a ceremonial appeal by the Patriarch and the Emperor to the Virgin. The attack was the first encounter between the Rusʹ and Byzantines and led the Patriarch to send missionaries north to engage and attempt to convert the Rusʹ and the Slavs.Majeska (2009)

p.52

Dimitri Obolensky, ''Byzantium and the Slavs'' (1994)

p.245

Foundation of the Kievan state

Rurik led the Rusʹ until his death in about 879, bequeathing his kingdom to his kinsman, Prince Oleg, as regent for his young son, Igor. In 880–82, Oleg led a military force south along the

Rurik led the Rusʹ until his death in about 879, bequeathing his kingdom to his kinsman, Prince Oleg, as regent for his young son, Igor. In 880–82, Oleg led a military force south along the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

river, capturing Smolensk

Smolensk ( rus, Смоленск, p=smɐˈlʲensk, a=smolensk_ru.ogg) is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow. First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest ...

and Lyubech

Liubech ( uk, Любеч, russian: Любеч, pl, Lubecz) is an urban-type settlement, previously a small ancient town (first mentioned in 882) connected with many important events in the Principality of Chernigov since the times of Kievan Rus'. ...

before reaching Kiev, where he deposed and killed Askold and Dir, proclaimed himself prince, and declared Kiev the " mother of Rusʹ cities." Oleg set about consolidating his power over the surrounding region and the riverways north to Novgorod, imposing tribute on the East Slav tribes.

In 883, he conquered the Drevlians

The Drevlians ( uk, Древляни, Drevliany, russian: Древля́не, Drevlyane) were a tribe of Early East Slavs between the 6th and the 10th centuries, which inhabited the territories of Polesia and right-bank Ukraine, west of the ea ...

, imposing a fur

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

tribute on them. By 885 he had subjugated the Poliane, Severiane, Vyatichi, and Radimichs

The Radimichs (also Radimichi) ( be, Радзiмiчы, russian: Радимичи, uk, Радимичі and pl, Radymicze) were an East Slavic tribe of the last several centuries of the 1st millennium, which inhabited upper east parts of the ...

, forbidding them to pay further tribute to the Khazars. Oleg continued to develop and expand a network of Rusʹ forts in Slav lands, begun by Rurik in the north.

The new Kievan state prospered due to its abundant supply of fur

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

s, beeswax

Beeswax (''cera alba'') is a natural wax produced by honey bees of the genus ''Apis''. The wax is formed into scales by eight wax-producing glands in the abdominal segments of worker bees, which discard it in or at the hive. The hive work ...

, honey

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of plants (primar ...

and slaves for export,Walter Moss, A History of Russia: To 1917 (2005)p. 37

and because it controlled three main trade routes of

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whic ...

. In the north, Novgorod served as a commercial link between the Baltic Sea and the Volga trade route

In the Middle Ages, the Volga trade route connected Northern Europe and Northwestern Russia with the Caspian Sea and the Sasanian Empire, via the Volga River. The Rus used this route to trade with Muslim countries on the southern shores of the ...

to the lands of the Volga Bulgars, the Khazars, and across the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central Asia ...

as far as Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon. I ...

, providing access to markets and products from Central Asia and the Middle East.Martin (2009)p. 47

Trade from the Baltic also moved south on a network of rivers and short portages along the Dnieper known as the " route from the Varangians to the Greeks," continuing to the Black Sea and on to Constantinople.Martin (2009)

pp. 40, 47. Kiev was a central outpost along the Dnieper route and a hub with the east–west overland trade route between the Khazars and the Germanic lands of Central Europe. and may have been a staging post for Radhanite Jewish traders between Western Europe, Itil and China. These commercial connections enriched Rusʹ merchants and princes, funding military forces and the construction of churches, palaces, fortifications, and further towns. Demand for luxury goods fostered production of expensive jewelry and religious wares, allowing their export, and an advanced credit and money-lending system may have also been in place.

Early foreign relations

Volatile steppe politics

The rapid expansion of the Rusʹ to the south led to conflict and volatile relationships with the Khazars and other neighbors on the Pontic steppe.Magocsi (2010)p. 62

Magocsi (2010)

p.66

The Khazars dominated trade from the Volga-Don steppes to the eastern Crimea and the northern Caucasus during the 8th century during an era historians call the ' Pax Khazarica', trading and frequently allying with the Byzantine Empire against Persians and Arabs. In the late 8th century, the collapse of the Göktürk Khaganate led the Magyars and the Pechenegs,

Ugrians

Historically, the Ugrians or Ugors were the ancestors of the Hungarians of Central Europe, and the Khanty and Mansi people of the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug of Russia. The name is sometimes also used in a modern context as a cover term for th ...

and Turkic peoples

The Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West, Central, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose members speak languages belonging t ...

from Central Asia, to migrate west into the steppe region, leading to military conflict, disruption of trade, and instability within the Khazar Khaganate. The Rusʹ and Slavs had earlier allied with the Khazars against Arab raids on the Caucasus, but they increasingly worked against them to secure control of the trade routes.

The Byzantine Empire was able to take advantage of the turmoil to expand its political influence and commercial relationships, first with the Khazars and later with the Rusʹ and other steppe groups. The Byzantines established the Theme of Cherson, formally known as Klimata, in the Crimea in the 830s to defend against raids by the Rusʹ and to protect vital grain shipments supplying Constantinople. Cherson also served as a key diplomatic link with the Khazars and others on the steppe, and it became the centre of Black Sea commerce. The Byzantines also helped the Khazars build a fortress at Sarkel on the Don river to protect their northwest frontier against incursions by the Turkic migrants and the Rusʹ, and to control caravan trade routes and the portage between the Don and Volga rivers.

The expansion of the Rusʹ put further military and economic pressure on the Khazars, depriving them of territory, tributaries and trade. In around 890, Oleg waged an indecisive war in the lands of the lower

The Byzantine Empire was able to take advantage of the turmoil to expand its political influence and commercial relationships, first with the Khazars and later with the Rusʹ and other steppe groups. The Byzantines established the Theme of Cherson, formally known as Klimata, in the Crimea in the 830s to defend against raids by the Rusʹ and to protect vital grain shipments supplying Constantinople. Cherson also served as a key diplomatic link with the Khazars and others on the steppe, and it became the centre of Black Sea commerce. The Byzantines also helped the Khazars build a fortress at Sarkel on the Don river to protect their northwest frontier against incursions by the Turkic migrants and the Rusʹ, and to control caravan trade routes and the portage between the Don and Volga rivers.

The expansion of the Rusʹ put further military and economic pressure on the Khazars, depriving them of territory, tributaries and trade. In around 890, Oleg waged an indecisive war in the lands of the lower Dniester

The Dniester, ; rus, Дне́стр, links=1, Dnéstr, ˈdⁿʲestr; ro, Nistru; grc, Τύρᾱς, Tyrās, ; la, Tyrās, la, Danaster, label=none, ) ( ,) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and th ...

and Dnieper rivers with the Tivertsi

The Tivertsi ( uk, Тиверці; ro, Tiverți or ), were a tribe of early East Slavs which lived in the lands near the Dniester, and probably the lower Danube, that is in modern-day western Ukraine and Republic of Moldova and possibly in east ...

and the Ulichs, who were likely acting as vassals of the Magyars, blocking Rusʹ access to the Black Sea. In 894, the Magyars and Pechenegs were drawn into the wars between the Byzantines and the Bulgarian Empire. The Byzantines arranged for the Magyars to attack Bulgarian territory from the north, and Bulgaria in turn persuaded the Pechenegs to attack the Magyars from their rear.John V. A. Fine, ''The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century'' (1991)pp. 138–139

Spanei (2009)

pp. 66, 70

Boxed in, the Magyars were forced to migrate further west across the Carpathian Mountains into the Hungarian plain, depriving the Khazars of an important ally and a buffer from the Rusʹ. The migration of the Magyars allowed Rusʹ access to the Black Sea, and they soon launched excursions into Khazar territory along the sea coast, up the Don river, and into the lower Volga region. The Rusʹ were raiding and plundering into the Caspian Sea region from 864, with the first large-scale expedition in 913, when they extensively raided Baku, Gilan, Mazandaran and penetrated into the Caucasus. As the 10th century progressed, the Khazars were no longer able to command tribute from the Volga Bulgars, and their relationship with the Byzantines deteriorated, as Byzantium increasingly allied with the Pechenegs against them. The Pechenegs were thus secure to raid the lands of the Khazars from their base between the Volga and

Don

Don, don or DON and variants may refer to:

Places

*County Donegal, Ireland, Chapman code DON

*Don (river), a river in European Russia

*Don River (disambiguation), several other rivers with the name

*Don, Benin, a town in Benin

*Don, Dang, a vill ...

rivers, allowing them to expand to the west. Rusʹ relations with the Pechenegs were complex, as the groups alternately formed alliances with and against one another. The Pechenegs were nomads roaming the steppe raising livestock which they traded with the Rusʹ for agricultural goods and other products.Martin (2003)p. 17

The lucrative Rusʹ trade with the Byzantine Empire had to pass through Pecheneg-controlled territory, so the need for generally peaceful relations was essential. Nevertheless, while the Primary Chronicle reports the Pechenegs entering Rusʹ territory in 915 and then making peace, they were waging war with one another again in 920.Magocsi (2010)

p. 67

Pechenegs are reported assisting the Rusʹ in later campaigns against the Byzantines, yet allied with the Byzantines against the Rusʹ at other times.

Rusʹ–Byzantine relations

After the Rusʹ attack on Constantinople in 860, the Byzantine Patriarch Photius sent missionaries north to convert the Rusʹ and the Slavs to Christianity. Prince

After the Rusʹ attack on Constantinople in 860, the Byzantine Patriarch Photius sent missionaries north to convert the Rusʹ and the Slavs to Christianity. Prince Rastislav of Moravia

Rastislav or Rostislav, also known as St. Rastislav, (Latin: ''Rastiz'', Greek: Ῥασισθλάβος / ''Rhasisthlábos'') was the second known ruler of Moravia (846–870).Spiesz ''et al.'' 2006, p. 20. Although he started his reign as vass ...

had requested the Emperor to provide teachers to interpret the holy scriptures, so in 863 the brothers Cyril and Methodius were sent as missionaries, due to their knowledge of the Slavonic language. The Slavs had no written language, so the brothers devised the Glagolitic alphabet

The Glagolitic script (, , ''glagolitsa'') is the oldest known Slavic alphabet. It is generally agreed to have been created in the 9th century by Saint Cyril, a monk from Thessalonica. He and his brother Saint Methodius were sent by the Byzan ...

, later replaced by Cyrillic (developed in the First Bulgarian Empire) and standardized the language of the Slavs, later known as Old Church Slavonic. They translated portions of the Bible and drafted the first Slavic civil code and other documents, and the language and texts spread throughout Slavic territories, including Kievan Rusʹ. The mission of Cyril and Methodius served both evangelical and diplomatic purposes, spreading Byzantine cultural influence in support of imperial foreign policy. In 867 the Patriarch announced that the Rusʹ had accepted a bishop, and in 874 he speaks of an "Archbishop of the Rusʹ."

Relations between the Rusʹ and Byzantines became more complex after Oleg took control over Kiev, reflecting commercial, cultural, and military concerns. The wealth and income of the Rusʹ depended heavily upon trade with Byzantium. Constantine Porphyrogenitus

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (; 17 May 905 – 9 November 959) was the fourth Emperor of the Macedonian dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, reigning from 6 June 913 to 9 November 959. He was the son of Emperor Leo VI and his fourth wife, Zoe Ka ...

described the annual course of the princes of Kiev, collecting tribute from client tribes, assembling the product into a flotilla of hundreds of boats, conducting them down the Dnieper to the Black Sea, and sailing to the estuary of the Dniester, the Danube delta, and on to Constantinople. On their return trip they would carry silk fabrics, spices, wine, and fruit.Vernadsky (1976)p.22

The importance of this trade relationship led to military action when disputes arose. The Primary Chronicle reports that the Rusʹ attacked Constantinople again in 907, probably to secure trade access. The Chronicle glorifies the military prowess and shrewdness of Oleg, an account imbued with legendary detail. Byzantine sources do not mention the attack, but a pair of treaties in 907 and 911 set forth a trade agreement with the Rusʹ, the terms suggesting pressure on the Byzantines, who granted the Rusʹ quarters and supplies for their merchants and tax-free trading privileges in Constantinople. The Chronicle provides a mythic tale of Oleg's death. A sorcerer prophesies that the death of the

Grand Prince

Grand prince or great prince (feminine: grand princess or great princess) ( la, magnus princeps; Greek: ''megas archon''; russian: великий князь, velikiy knyaz) is a title of nobility ranked in honour below emperor, equal of king ...

would be associated with a certain horse. Oleg has the horse sequestered, and it later dies. Oleg goes to visit the horse and stands over the carcass, gloating that he had outlived the threat, when a snake strikes him from among the bones, and he soon becomes ill and dies. The Chronicle reports that Prince Igor succeeded Oleg in 913, and after some brief conflicts with the Drevlians and the Pechenegs, a period of peace ensued for over twenty years.

In 941, Igor led another major Rusʹ attack on Constantinople, probably over trading rights again. A navy of 10,000 vessels, including Pecheneg allies, landed on the Bithynian coast and devastated the Asiatic shore of the Bosphorus.Ostrogorski, p.277 The attack was well timed, perhaps due to intelligence, as the Byzantine fleet was occupied with the Arabs in the Mediterranean, and the bulk of its army was stationed in the east. The Rusʹ burned towns, churches and monasteries, butchering the people and amassing booty. The emperor arranged for a small group of retired ships to be outfitted with Greek fire throwers and sent them out to meet the Rusʹ, luring them into surrounding the contingent before unleashing the Greek fire.Logan, p.193.

In 941, Igor led another major Rusʹ attack on Constantinople, probably over trading rights again. A navy of 10,000 vessels, including Pecheneg allies, landed on the Bithynian coast and devastated the Asiatic shore of the Bosphorus.Ostrogorski, p.277 The attack was well timed, perhaps due to intelligence, as the Byzantine fleet was occupied with the Arabs in the Mediterranean, and the bulk of its army was stationed in the east. The Rusʹ burned towns, churches and monasteries, butchering the people and amassing booty. The emperor arranged for a small group of retired ships to be outfitted with Greek fire throwers and sent them out to meet the Rusʹ, luring them into surrounding the contingent before unleashing the Greek fire.Logan, p.193.

Liutprand of Cremona

Liutprand, also Liudprand, Liuprand, Lioutio, Liucius, Liuzo, and Lioutsios (c. 920 – 972),"LIUTPRAND OF CREMONA" in '' The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium'', Oxford University Press, New York & Oxford, 1991, p. 1241. was a historian, diplomat, ...

wrote that "the Rusʹ, seeing the flames, jumped overboard, preferring water to fire. Some sank, weighed down by the weight of their breastplates and helmets; others caught fire." Those captured were beheaded. The ploy dispelled the Rusʹ fleet, but their attacks continued into the hinterland as far as Nicomedia, with many atrocities reported as victims were crucified and set up for use as targets. At last a Byzantine army arrived from the Balkans to drive the Rusʹ back, and a naval contingent reportedly destroyed much of the Rusʹ fleet on its return voyage (possibly an exaggeration since the Rusʹ soon mounted another attack). The outcome indicates increased military might by Byzantium since 911, suggesting a shift in the balance of power.

Igor returned to Kiev keen for revenge. He assembled a large force of warriors from among neighboring Slavs and Pecheneg allies, and sent for reinforcements of Varangians from "beyond the sea." In 944 the Rusʹ force advanced again on the Greeks, by land and sea, and a Byzantine force from Cherson responded. The Emperor sent gifts and offered tribute in lieu of war, and the Rusʹ accepted. Envoys were sent between the Rusʹ, the Byzantines, and the Bulgarians in 945, and a peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring ...

was completed. The agreement again focused on trade, but this time with terms less favorable to the Rusʹ, including stringent regulations on the conduct of Rusʹ merchants in Cherson and Constantinople and specific punishments for violations of the law. The Byzantines may have been motivated to enter the treaty out of concern of a prolonged alliance of the Rusʹ, Pechenegs, and Bulgarians against them, though the more favorable terms further suggest a shift in power.

Sviatoslav

Following the death of Grand Prince Igor in 945, his wife Olga ruled as

Following the death of Grand Prince Igor in 945, his wife Olga ruled as regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

in Kiev until their son Sviatoslav reached maturity (c. 963). His decade-long reign over Rusʹ was marked by rapid expansion through the conquest of the Khazars of the Pontic steppe and the invasion of the Balkans. By the end of his short life, Sviatoslav carved out for himself the largest state in Europe, eventually moving his capital from Kiev to Pereyaslavets

Pereyaslavets ( East Slavic: ) or Preslavets ( bg, Преславец) was a trade city located near mouths of the Danube. The city's name is derived from that of the Bulgarian capital of the time, Preslav, and means Little Preslav (). In Greek ...

on the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

in 969.

In contrast with his mother's conversion to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

, Sviatoslav, like his druzhina

In the medieval history of Kievan Rus' and Early Poland, a druzhina, drużyna, or družyna ( Slovak and cz, družina; pl, drużyna; ; , ''druzhýna'' literally a "fellowship") was a retinue in service of a Slavic chieftain, also called ''knyaz ...

, remained a staunch pagan. Due to his abrupt death in an ambush in 972, Sviatoslav's conquests, for the most part, were not consolidated into a functioning empire, while his failure to establish a stable succession led to a fratricidal feud among his sons, which resulted in two of his three sons being killed.

Reign of Vladimir and Christianisation

It is not clearly documented when the title of the Grand Duke was first introduced, but the importance of the Kiev principality was recognized after the death of Sviatoslav I in 972 and the ensuing struggle betweenVladimir the Great

Vladimir I Sviatoslavich or Volodymyr I Sviatoslavych ( orv, Володимѣръ Свѧтославичь, ''Volodiměrъ Svętoslavičь'';, ''Uladzimir'', russian: Владимир, ''Vladimir'', uk, Володимир, ''Volodymyr''. Se ...

and Yaropolk I. The region of Kiev dominated the state of Kievan Rusʹ for the next two centuries. The grand prince

Grand prince or great prince (feminine: grand princess or great princess) ( la, magnus princeps; Greek: ''megas archon''; russian: великий князь, velikiy knyaz) is a title of nobility ranked in honour below emperor, equal of king ...

or grand duke ( be, вялікі князь, translit=vyaliki knyaz’, translit-std=bgn/pcgn or , russian: великий князь, translit=velikiy kniaz, rue, великый князь, translit=velykŷĭ kni͡az′, translit-std=ala-lc, uk, великий князь, translit=velykyi kniaz, translit-std=ungegn) of Kiev controlled the lands around the city, and his formally subordinate relatives ruled the other cities and paid him tribute. The zenith of the state's power came during the reigns of Vladimir the Great (980–1015) and Prince Yaroslav I the Wise (1019–1054). Both rulers continued the steady expansion of Kievan Rusʹ that had begun under Oleg.

Vladimir had been prince of Novgorod The Prince of Novgorod (russian: Князь новгородский, ''knyaz novgorodskii'') was the chief executive of the Republic of Novgorod. The office was originally an appointed one until the late eleventh or early twelfth century, then bec ...

when his father Sviatoslav I died in 972. He was forced to flee to Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

in 976 after his half-brother Yaropolk had murdered his other brother Oleg

Oleg (russian: Олег), Oleh ( uk, Олег), or Aleh ( be, Алег) is an East Slavic given name. The name is very common in Russia, Ukraine and Belаrus. It derives from the Old Norse ''Helgi'' ( Helge), meaning "holy", "sacred", or "bless ...

and taken control of Rus. In Scandinavia, with the help of his relative Earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form '' jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particula ...

Håkon Sigurdsson, ruler of Norway, Vladimir assembled a Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

army and reconquered Novgorod and Kiev from Yaropolk.

As Prince of Kiev, Vladimir's most notable achievement was the Christianization of Kievan Rusʹ, a process that began in 988. The Primary Chronicle states that when Vladimir had decided to accept a new faith instead of the traditional idol-worship ( paganism) of the Slavs, he sent out some of his most valued advisors and warriors as emissaries to different parts of Europe. They visited the Christians of the Latin Rite, the Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s, and the Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

before finally arriving in Constantinople. They rejected Islam because, among other things, it prohibited the consumption of alcohol, and Judaism because the god of the Jews had permitted his chosen people

Throughout history, various groups of people have considered themselves to be the chosen people of a deity, for a particular purpose. The phenomenon of a "chosen people" is well known among the Israelites and Jews, where the term ( he, עם ס� ...

to be deprived of their country.Janet Martin, Medieval Russia, 980–1584, (Cambridge, 1995), p. 6-7

They found the ceremonies in the Roman church to be dull. But at Constantinople, they were so astounded by the beauty of the cathedral of Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia ( 'Holy Wisdom'; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque ( tr, Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi), is a mosque and major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The cathedral was originally built as a Greek Ortho ...

and the liturgical service held there that they made up their minds there and then about the faith they would like to follow. Upon their arrival home, they convinced Vladimir that the faith of the Byzantine Rite was the best choice of all, upon which Vladimir made a journey to Constantinople and arranged to marry Princess Anna, the sister of Byzantine emperor Basil II

Basil II Porphyrogenitus ( gr, Βασίλειος Πορφυρογέννητος ;) and, most often, the Purple-born ( gr, ὁ πορφυρογέννητος, translit=ho porphyrogennetos).. 958 – 15 December 1025), nicknamed the Bulgar S ...

.

Vladimir's choice of Eastern Christianity may also have reflected his close personal ties with Constantinople, which dominated the Black Sea and hence trade on Kiev's most vital commercial route, the Dnieper River. Adherence to the

Vladimir's choice of Eastern Christianity may also have reflected his close personal ties with Constantinople, which dominated the Black Sea and hence trade on Kiev's most vital commercial route, the Dnieper River. Adherence to the Eastern Church

Eastern Christianity comprises Christian traditions and church families that originally developed during classical and late antiquity in Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, Asia Minor, the Caucasus, Northeast Africa, the Fertile Crescent and ...

had long-range political, cultural, and religious consequences. The church had a liturgy written in Cyrillic and a corpus of translations from Greek that had been produced for the Slavic peoples. This literature facilitated the conversion to Christianity of the Eastern Slavs

The East Slavs are the most populous subgroup of the Slavs. They speak the East Slavic languages, and formed the majority of the population of the medieval state Kievan Rus', which they claim as their cultural ancestor.John Channon & Robert Hud ...

and introduced them to rudimentary Greek philosophy, science, and historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians ha ...

without the necessity of learning Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

(there were some merchants who did business with Greeks and likely had an understanding of contemporary business Greek).

In contrast, educated people in medieval Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

learned Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

. Enjoying independence from the Roman authority and free from tenets of Latin learning, the East Slavs developed their own literature and fine arts, quite distinct from those of other Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonical ...

countries. (See Old East Slavic language and Architecture of Kievan Rus for details). Following the Great Schism of 1054, the Rusʹ church maintained communion with both Rome and Constantinople for some time, but along with most of the Eastern churches it eventually split to follow the Eastern Orthodox. That being said, unlike other parts of the Greek world, Kievan Rusʹ did not have a strong hostility to the Western world.

Golden age

Yaroslav, known as "the Wise", struggled for power with his brothers. A son of

Yaroslav, known as "the Wise", struggled for power with his brothers. A son of Vladimir the Great

Vladimir I Sviatoslavich or Volodymyr I Sviatoslavych ( orv, Володимѣръ Свѧтославичь, ''Volodiměrъ Svętoslavičь'';, ''Uladzimir'', russian: Владимир, ''Vladimir'', uk, Володимир, ''Volodymyr''. Se ...

, he was prince of Novgorod at the time of his father's death in 1015. Subsequently, his eldest surviving brother, Svyatopolk the Accursed, according to domestic but not foreign sources, killed three of his other brothers and seized power in Kiev. Yaroslav, with the active support of the Novgorodians and the help of Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

mercenaries, defeated Svyatopolk and became the grand prince of Kiev in 1019.

Although he first established his rule over Kiev in 1019, he did not have uncontested rule of all of Kievan Rusʹ until 1036. Like Vladimir, Yaroslav was eager to improve relations with the rest of Europe, especially the Byzantine Empire. Yaroslav's granddaughter, Eupraxia, the daughter of his son Vsevolod I, Prince of Kiev

Vsevolod I Yaroslavich ( Russian: Всеволод I Ярославич, Ukrainian: Всеволод I Ярославич, Old Norse: Vissivald) (c. 1030 – 13 April 1093), ruled as Grand Prince of Kiev from 1078 until his death.

Early l ...

, was married to Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor

Henry IV (german: Heinrich IV; 11 November 1050 – 7 August 1106) was Holy Roman Emperor from 1084 to 1105, King of Germany from 1054 to 1105, King of Italy and Burgundy from 1056 to 1105, and Duke of Bavaria from 1052 to 1054. He was the so ...

. Yaroslav also arranged marriages for his sister and three daughters to the kings of Poland, France, Hungary and Norway.

Yaroslav promulgated the first East Slavic law code, '' Russkaya Pravda''; built Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kiev

Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, Ukraine, is an architectural monument of Kyivan Rus. The former cathedral is one of the city's best known landmarks and the first heritage site in Ukraine to be inscribed on the World Heritage List along with the K ...

and Saint Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod; patronized local clergy and monasticism; and is said to have founded a school system. Yaroslav's sons developed the great Kiev Pechersk Lavra (monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone ( hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer whi ...

), which functioned in Kievan Rusʹ as an ecclesiastical academy.

In the centuries that followed the state's foundation, Rurik's descendants shared power over Kievan Rusʹ. Princely succession moved from elder to younger brother and from uncle to nephew, as well as from father to son. Junior members of the dynasty usually began their official careers as rulers of a minor district, progressed to more lucrative principalities, and then competed for the coveted throne of Kiev.

Fragmentation and decline

The gradual disintegration of the Kievan Rusʹ began in the 11th century, after the death of

The gradual disintegration of the Kievan Rusʹ began in the 11th century, after the death of Yaroslav the Wise

Yaroslav the Wise or Yaroslav I Vladimirovich; russian: Ярослав Мудрый, ; uk, Ярослав Мудрий; non, Jarizleifr Valdamarsson; la, Iaroslaus Sapiens () was the Grand Prince of Kiev from 1019 until his death. He was al ...

. The position of the Grand Prince of Kiev was weakened by the growing influence of regional clans.

An unconventional power succession system was established (rota system

The rota (or rotation) system or the lestvitsa system (from the Old Church Slavonic word for "ladder" or "staircase") was a system of collateral succession practiced

(though imperfectly) in Kievan Rus', later appanages, and early the Grand Duchy ...