Keith Park on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Following the commencement of the German spring offensive in late March 1918, Park returned to France as a major to take command of No. 48 Squadron. At the time he joined the squadron, he was the only surviving pilot from its 1917 ranks. The first few days of his tenure were marked by a number of relocations, as the squadron repeatedly retreated to new sites to stay ahead of the advancing Germans. It eventually settled in at

Following the commencement of the German spring offensive in late March 1918, Park returned to France as a major to take command of No. 48 Squadron. At the time he joined the squadron, he was the only surviving pilot from its 1917 ranks. The first few days of his tenure were marked by a number of relocations, as the squadron repeatedly retreated to new sites to stay ahead of the advancing Germans. It eventually settled in at

On 8 July 1942, Park relinquished command in Egypt and went to Malta on 14 July as a replacement for Hugh Lloyd, the RAF commander on the besieged island. It was felt that his experience of fighter defence operations was needed. Arriving by flying boat, he landed in the midst of a raid although Lloyd had specifically requested he circle the harbour until it had passed. Lloyd met Park and admonished him for taking an unnecessary risk.

Park abandoned the defensive approach taken by Lloyd, in which the island's fighters took off, circled behind the approaching enemy bombers and engaged them over Malta. Park, having plenty of Spitfires on hand, sought to intercept and break up the German and Italian bomber formations before they reached Malta. One squadron would endeavour to engage the fighters providing high cover for the bombers, another would deal with the closer escorting fighters and the third would seek out the bombers directly. Using these tactics, similar what had been employed by his No. 11 Group during the Battle of Britain, Park believed that it would be more likely that the enemy would be shot down or abort their objectives. His forces began implementing what Park called his ''Forward Interception Plan'' on 25 July. It was immediately successful, for within a week, daylight raids had ceased. The Axis response was to send in fighter sweeps at even higher altitudes to gain the tactical advantage. Park retaliated by ordering his fighters to climb no higher than . This conceded a considerable height advantage to the enemy fighters, but forced them to engage the Spitfires at altitudes more suitable for the latter.

By September the Axis's aerial operations against Malta were on the decline and the British regained air superiority over the island. Shortly, RAF bomber and torpedo squadrons returned to Malta in anticipation of offensive operations against German forces in North Africa. Park dispatched Hurricane fighter bombers, fitted with extra fuel tanks, to attack enemy supply lines as far away as Egypt. Vickers Wellington medium bombers and Bristol Beaufort

On 8 July 1942, Park relinquished command in Egypt and went to Malta on 14 July as a replacement for Hugh Lloyd, the RAF commander on the besieged island. It was felt that his experience of fighter defence operations was needed. Arriving by flying boat, he landed in the midst of a raid although Lloyd had specifically requested he circle the harbour until it had passed. Lloyd met Park and admonished him for taking an unnecessary risk.

Park abandoned the defensive approach taken by Lloyd, in which the island's fighters took off, circled behind the approaching enemy bombers and engaged them over Malta. Park, having plenty of Spitfires on hand, sought to intercept and break up the German and Italian bomber formations before they reached Malta. One squadron would endeavour to engage the fighters providing high cover for the bombers, another would deal with the closer escorting fighters and the third would seek out the bombers directly. Using these tactics, similar what had been employed by his No. 11 Group during the Battle of Britain, Park believed that it would be more likely that the enemy would be shot down or abort their objectives. His forces began implementing what Park called his ''Forward Interception Plan'' on 25 July. It was immediately successful, for within a week, daylight raids had ceased. The Axis response was to send in fighter sweeps at even higher altitudes to gain the tactical advantage. Park retaliated by ordering his fighters to climb no higher than . This conceded a considerable height advantage to the enemy fighters, but forced them to engage the Spitfires at altitudes more suitable for the latter.

By September the Axis's aerial operations against Malta were on the decline and the British regained air superiority over the island. Shortly, RAF bomber and torpedo squadrons returned to Malta in anticipation of offensive operations against German forces in North Africa. Park dispatched Hurricane fighter bombers, fitted with extra fuel tanks, to attack enemy supply lines as far away as Egypt. Vickers Wellington medium bombers and Bristol Beaufort

In the

In the

In the United Kingdom, Keith Park Crescent, a residential road near the former RAF station at Biggin Hill, is named after him, as is Keith Park Road in Uxbridge.

A

In the United Kingdom, Keith Park Crescent, a residential road near the former RAF station at Biggin Hill, is named after him, as is Keith Park Road in Uxbridge.

A  Thanks to the advocacy of financier Terry Smith, on 4 November 2009 a temporary fibreglass statue of Park was unveiled on the Fourth plinth in

Thanks to the advocacy of financier Terry Smith, on 4 November 2009 a temporary fibreglass statue of Park was unveiled on the Fourth plinth in

''Keith Rodney Park 2/1254'' WWI NZEF Military Personnel Record (online)

Thames Coromandel District Council – our airfields

Profile

on

Clive James, BBC

1961 BBC Interview – Park describes Battle of Britain tactics, strategies and post-campaign conspiracies.

# , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Park, Keith 1892 births 1975 deaths Battle of Britain British Army personnel of World War I Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath People educated at Otago Boys' High School New Zealand Army personnel New Zealand military personnel of World War I New Zealand World War I flying aces New Zealand World War II pilots New Zealand people of Scottish descent New Zealand people of World War II Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) Commanders of the Legion of Merit Royal Air Force air marshals of World War II Royal Flying Corps officers New Zealand military personnel of World War II New Zealand commanders People from Thames, New Zealand New Zealand Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Alumni of the Royal College of Defence Studies Auckland City Councillors

Air Chief Marshal

Air chief marshal (Air Chf Mshl or ACM) is a high-ranking air officer originating from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence. An air chief marshal is equivalent to an Admi ...

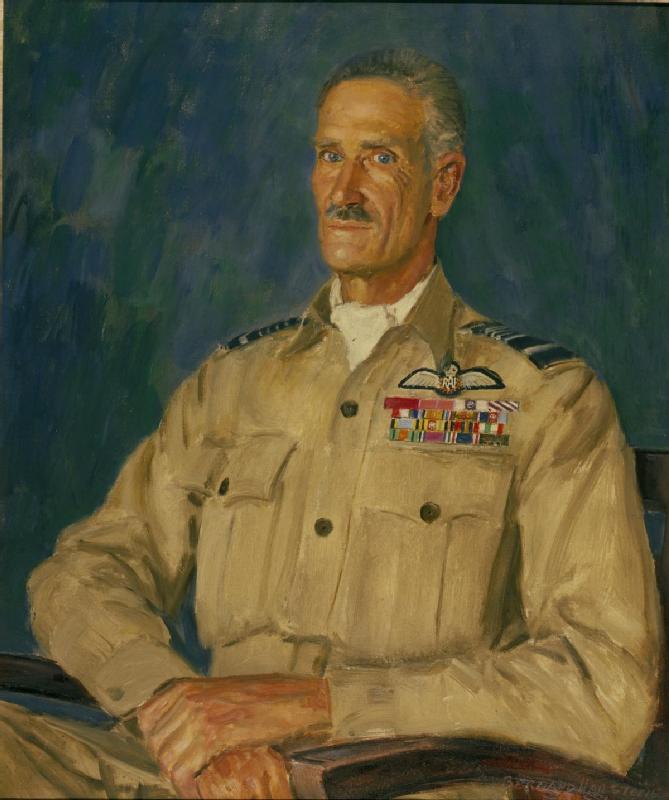

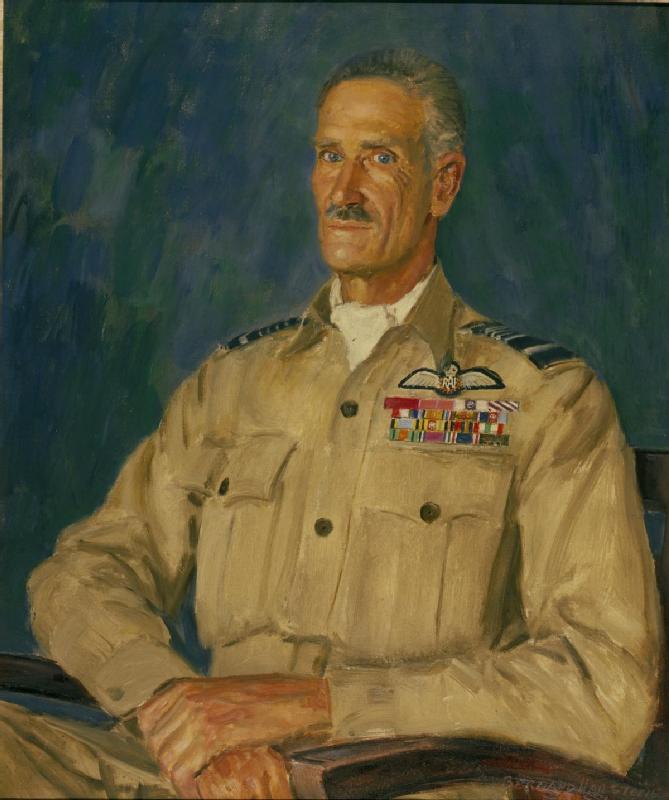

Sir Keith Rodney Park, (15 June 1892 – 6 February 1975) was a New Zealand-born officer of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

(RAF). During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, his leadership of the RAF's No. 11 Group was pivotal to the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

's defeat in the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

.

Born in Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

, Park was a mariner when he enlisted in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force

The New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) was the title of the military forces sent from New Zealand to fight alongside other British Empire and Dominion troops during World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945). Ultimately, the NZE ...

for service in the First World War. Posted to the artillery, he fought in the Gallipoli campaign, partway through which he transferred to the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

. On the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

, he was present for the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme (French: Bataille de la Somme), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place be ...

and was injured. He obtained another transfer, this time to the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

. Once his flight training was completed, he served as an instructor before being posted to serve with No. 48 Squadron on the Western Front. He became a flying ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during aerial combat. The exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ace is varied, but is usually co ...

, achieving a number of aerial victories and eventually becoming commander of the squadron.

In the postwar period, he served with the RAF in a series of command and staff postings, including a period as air attaché in South America. By the late 1930s, he was serving in Fighter Command, as Air Marshal Hugh Dowding

Air Chief Marshal Hugh Caswall Tremenheere Dowding, 1st Baron Dowding, (24 April 1882 – 15 February 1970) was an officer in the Royal Air Force. He was Air Officer Commanding RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain and is generally c ...

's senior air staff officer. The two worked together to devise aerial tactics and management strategies for the aerial defence of the United Kingdom. Soon after the outbreak of the Second World War, he was placed in command of No. 11 Group, responsible for the defence of South East England and London. Due to the strategic significance and geographic location concerning the Luftwaffe, Park’s No. 11 Group bore the brunt of the German aerial assault during the Battle of Britain. His careful management of his fighter aircraft and pilots ensured that Britain retained air superiority along the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

.

Relieved of command after the Battle of Britain, Park served in a training role before being posted to the Middle East as Air Officer Commanding, Egypt in late 1941. Midway through the following year, he took charge of the aerial defences of Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, then under heavy attack from the Luftwaffe and the ''Regia Aeronautica

The Italian Royal Air Force (''Regia Aeronautica Italiana'') was the name of the air force of the Kingdom of Italy. It was established as a service independent of the Royal Italian Army from 1923 until 1946. In 1946, the monarchy was aboli ...

'' (Italian Air Force). When the siege was lifted he successfully transitioned Malta's RAF forces from a defensive role into an offensive footing in preparation for the Allied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis powers ( Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany). It b ...

. From 1944, he held senior roles in the Middle East and in British India. He retired from the RAF in 1946 as air chief marshal. Returning to New Zealand, he worked in the aviation industry for a British aircraft manufacturer and then became involved in local body politics in Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about I ...

. He died in February 1975 due to heart problems.

Early life

Born inThames, New Zealand

Thames () ( mi, Pārāwai) is a town at the southwestern end of the Coromandel Peninsula in New Zealand's North Island. It is located on the Firth of Thames close to the mouth of the Waihou River. The town is the seat of the Thames-Coromandel ...

, on 15 June 1892, Keith Rodney Park was the third son and ninth of ten children born to Professor James Livingstone Park from Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, who was a geologist and director of the Thames School of Mines, and his wife, New Zealand native Frances Rogers. Park was schooled at King's College in Auckland until 1905. The following year he attended Otago Boys' High School

, motto_translation = "The ‘right’ learning builds a heart of oak"

, type = State secondary, day and boarding

, established = ; years ago

, streetaddress= 2 Arthur Street

, region = Dunedin

, state = Otago

, zipcod ...

in Dunedin

Dunedin ( ; mi, Ōtepoti) is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand (after Christchurch), and the principal city of the Otago region. Its name comes from , the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. Th ...

, to where his father had moved the family following his appointment as a lecturer in mining at the University of Otago

, image_name = University of Otago Registry Building2.jpg

, image_size =

, caption = University clock tower

, motto = la, Sapere aude

, mottoeng = Dare to be wise

, established = 1869; 152 years ago

, type = Public research collegiate ...

. By this time Park's parents had separated, his mother moving to Australia and leaving the children in the care of their father.

At Otago Boys' High, Park joined the school's Cadet Corps. Once Park completed his education, he found employment at the Union Steam Ship Company. He had always enjoyed boats and within the Park family was known as 'Skipper'. In his new job, he went to sea as a purser

A purser is the person on a ship principally responsible for the handling of money on board. On modern merchant ships, the purser is the officer responsible for all administration (including the ship's cargo and passenger manifests) and supply. ...

aboard collier and passenger

A passenger (also abbreviated as pax) is a person who travels in a vehicle, but does not bear any responsibility for the tasks required for that vehicle to arrive at its destination or otherwise operate the vehicle, and is not a steward. Th ...

steamships, initially sailing on vessels making their way along the coast but later he worked on passenger vessels travelling to Australia and islands in the Pacific. He also served as a Territorial

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or an ...

soldier in the New Zealand Field Artillery

Field artillery is a category of mobile artillery used to support armies in the field. These weapons are specialized for mobility, tactical proficiency, short range, long range, and extremely long range target engagement.

Until the early 20t ...

, from March 1911 to November 1913.

First World War

Soon after outbreak of theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Park was given permission from his employers to leave the company and join the war effort. Despite his maritime experience, he enlisted in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force

The New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) was the title of the military forces sent from New Zealand to fight alongside other British Empire and Dominion troops during World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945). Ultimately, the NZE ...

(NZEF) on 14 December 1914 and was posted to the Field Artillery. He was promoted to corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use in some form by many militaries and by some police forces or other uniformed organizations. The word is derived from the medieval Italian phrase ("head of a body"). The rank is usually the lowest ranking non- ...

in early February 1915. He departed New Zealand the same month as part of the third draft of reinforcements for the NZEF, destined for the Middle East. On arrival, he was posted to the 4th Howitzer Battery, under the command of Major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

Norrie Falla.

In early April 1915, military planners in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

decided that the NZEF would be part of the Allied forces that would open up a new front in the Middle East, by landing on the Gallipoli Peninsula. Park participated in the Landing at Anzac Cove on 25 April, going ashore at Anzac Cove that evening or early the following morning with his battery. The 4th Howitzer Battery was the only such unit at Anzac Cove but had limited ammunition and initially was unable to expend more than a few rounds a day. When not engaged in artillery fire, Park would act as a messenger. In the trench warfare

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising Trench#Military engineering, military trenches, in which troops are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artille ...

that followed, Park's achievements were recognised and in July he gained a commission as second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army unt ...

. He commanded an artillery battery during the August offensive. Afterwards Park took the unusual decision to transfer from the NZEF to the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

, joining the Royal Horse and Field Artillery.

Attached to the 29th Division as a temporary second lieutenant, Park was posted to No. 10 Battery, of the 147th Brigade, at Helles. He was commander of a 12-pounder naval gun, which was often subject to Turkish counter-fire. He and the rest of his battery was evacuated from Gallipoli to Egypt in January 1916, after the decision was made to abandon the Allied positions there. The battle had left its mark on him both physically and mentally, though later on in life he would remember it with nostalgia. He particularly admired the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. It was formed in Egypt in December 1914, and operated during the Gallipoli campaign. General William Birdwood com ...

commander, Sir William Birdwood

Field Marshal William Riddell Birdwood, 1st Baron Birdwood, (13 September 1865 – 17 May 1951) was a British Army officer. He saw active service in the Second Boer War on the staff of Lord Kitchener. He saw action again in the First World War ...

, whose leadership style and attention to detail would be a model for Park in his later career.

In March Park's battery, along with the rest of the 29th Division, was shipped to the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

and assigned to a sector along the Somme __NOTOC__

Somme or The Somme may refer to: Places

*Somme (department), a department of France

*Somme, Queensland, Australia

*Canal de la Somme, a canal in France

*Somme (river), a river in France

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Somme'' (book), a ...

. Two months later, Park's rank was made substantive. By this time he had an interest in aviation; while in Egypt while preparing for the move to France, he had requested a flight so that he could assess its suitability to help in observations but was told that aerial reconnaissance was a waste of time. Now, prior to the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme (French: Bataille de la Somme), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place be ...

, he learned how useful aircraft could be in a military role, getting a taste of flight by being taken aloft to check his battery's camouflage. He reported back on the ready manner in which the British guns could be detected. During the battle itself, which commenced on 1 July, the artillery was heavily engaged. On 21 October, while trying to withdraw an unserviceable gun for repair, Park was blown off his horse by a German shell. Wounded, he was evacuated to England and medically certified "unfit for active service," which technically meant he was unfit to ride a horse. After a brief remission recovering from his wounds, recuperating and doing training duties at Woolwich Depot, he joined the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

(RFC) in December. He had been trying for some time to obtain a transfer but the senior officers in the 29th Division would not allow this for its personnel serving in France; in later years Park saw his wounding as being particularly fortuitous for his future military career.

Royal Flying Corps

Once in the RFC, Park's training commenced atReading

Reading is the process of taking in the sense or meaning of letters, symbols, etc., especially by sight or touch.

For educators and researchers, reading is a multifaceted process involving such areas as word recognition, orthography (spell ...

, for a course at the School of Military Aeronautics. Much of this initial training involved military basics, such as drill, and theoretical matters, like Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one ...

. His flight instruction did not commence until he went to Netheravon

Netheravon is a village and civil parish on the River Avon and A345 road, about north of the town of Amesbury in Wiltshire, South West England. It is within Salisbury Plain.

The village is on the right (west) bank of the Avon, opposite Fitt ...

where, after flying an Avro 504K

The Avro 504 was a First World War biplane aircraft made by the Avro aircraft company and under licence by others. Production during the war totalled 8,970 and continued for almost 20 years, making it the most-produced aircraft of any kind tha ...

with an instructor, he soled on a Maurice Farman MF11 Shorthorn. The RFC still lacked sophistication in its flight training, and many pilots were sent to France with barely more than basic skills in flying. Park, having accumulated over 20 hours solo and 30 hours flying in total, thus qualifying for his wings

A wing is a type of fin that produces lift while moving through air or some other fluid. Accordingly, wings have streamlined cross-sections that are subject to aerodynamic forces and act as airfoils. A wing's aerodynamic efficiency is expre ...

, was posted to Rendcomb on instructing duties in March 1917.

At Rendcomb, Park accumulated over 100 hours more flying time before, in June, he was posted to France. The amount of time he had accumulated in the air at this stage enhanced his survival prospects in aerial combat. On reporting to RFC headquarters in Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the C ...

, he was advised that he was to be a bomber pilot and sent to a depot pool of pilots at Saint-Omer

Saint-Omer (; vls, Sint-Omaars) is a commune and sub-prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais department in France.

It is west-northwest of Lille on the railway to Calais, and is located in the Artois province. The town is named after Saint Audoma ...

. This was despite his specialisation in fighter aircraft. After some days without an assignment, he contacted No. 48 Squadron at La Bellevue; this resulted in Park's posting to that squadron on 7 July.

Service with No. 48 Squadron

Shortly after Park's arrival at No. 48 Squadron, it was moved to Frontier Aerodrome just east ofDunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.

. It was equipped with the new Bristol Fighter, a two-seat biplane fighter and reconnaissance aircraft, and carried out patrols, reconnaissance flights and escorted bombers attacking German aerodromes in Belgium. He had his first engagement with an enemy fighter on 24 July, when he was engaged by three Albatros D.III

The Albatros D.III was a biplane fighter aircraft used by the Imperial German Army Air Service ('' Luftstreitkräfte'') during World War I. A modified licence model was built by Oeffag for the Austro-Hungarian Air Service ( ''Luftfahrtruppen''). ...

scout aircraft near Middelkerke. He and his observer, operating a Lewis gun, successfully drove off the attackers. When the Germans started using their heavy bombers to attack London and other targets in England during the summer, the squadron was tasked with interception duties. However, Park never saw the enemy on these flights. He achieved his first aerial victory on 17 August, shooting down a German aircraft and causing the destruction of three others, with Arthur Noss as his observer. For his exploits, the commander of 4th Brigade, Brigadier-General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

John Becke

Brigadier general John Harold Whitworth Becke, (17 September 1879 – 7 February 1949) was an infantry officer in the Second Boer War and squadron, wing and brigade commander in the Royal Flying Corps during World War I. He transferred to the ...

, recommended Park and Noss for the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC ...

(MC). This was duly awarded, the published citation for Park's MC reading:

Park had more success on 21 August, driving one Albatros scout out of control and shooting down another. On 2 September, he fired upon another Albatros scout near Diksmuide

(; french: Dixmude, ; vls, Diksmude) is a Belgian city and municipality in the Flemish province of West Flanders. The municipality comprises the city of proper and the former communes of Beerst, Esen, Kaaskerke, Keiem, Lampernisse, Leke ...

, seeing it go down out of control. He and his observer shot down Hauptmann Otto Hartmann, the commander of '' Jagdstaffel 28'' on 3 September. Two days later a pilot of '' Jasta Boelcke'', Franz Pernet, the stepson of General Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German general, politician and military theorist. He achieved fame during World War I for his central role in the German victories at Liège and Tannenberg in 1914. ...

, was killed by Park and his observer, and this was followed by the destruction of a DFW C.V

The DFW C.IV, DFW C.V, DFW C.VI, and DFW F37 were a family of German reconnaissance aircraft first used in 1916 in World War I. They were conventionally configured biplanes with unequal-span unstaggered wings and seating for the pilot and observer ...

reconnaissance aircraft over the sea. He was promoted to temporary captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on 11 September. He shot down two more German aircraft on 15 September. To recognise Park's run of success, which by this time amounted to having destroyed seven German aircraft and damaging at least five others, Becke recommended him for the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly of other parts of the Commonwealth, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, ty ...

. The senior officer of the RFC in France, Major-General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Hugh Trenchard, downgraded this to a Bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar ( ...

to his MC on the basis this was sufficient reward. The published citation read:

Soon afterwards, No. 48 Squadron moved to the Arras

Arras ( , ; pcd, Aro; historical nl, Atrecht ) is the prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais department, which forms part of the region of Hauts-de-France; before the reorganization of 2014 it was in Nord-Pas-de-Calais. The historic centre of ...

sector for a rest, having incurred a number of casualties in the previous weeks. There, Park, now a flight leader, concentrated on preparing his command, which contained many inexperienced replacement pilots, for aerial combat. It resumed operations but it was now involved in less dangerous work, and casualties were light. On 3 January 1918, Park and his observer were flying near Ramicourt on a photo reconnaissance when they were engaged by several German Albatros fighters. Park was able to send one Albatros out of control but his observer's gun jammed, increasing the difficulty of fending off the remainder. Park eventually evaded them, although his engine was damaged by machine gun fire and he force landed behind British lines. The squadron's most successful pilot over the August–September period, he was subsequently sent to England for a rest. This involved instructing Canadian trainee fighter pilots at Hooton Park

Royal Air Force Hooton Park or more simply RAF Hooton Park, on the Wirral Peninsula, Cheshire, is a former Royal Air Force station originally built for the Royal Flying Corps in 1917 as a training aerodrome for pilots in the First World War. D ...

.

Squadron command

Following the commencement of the German spring offensive in late March 1918, Park returned to France as a major to take command of No. 48 Squadron. At the time he joined the squadron, he was the only surviving pilot from its 1917 ranks. The first few days of his tenure were marked by a number of relocations, as the squadron repeatedly retreated to new sites to stay ahead of the advancing Germans. It eventually settled in at

Following the commencement of the German spring offensive in late March 1918, Park returned to France as a major to take command of No. 48 Squadron. At the time he joined the squadron, he was the only surviving pilot from its 1917 ranks. The first few days of his tenure were marked by a number of relocations, as the squadron repeatedly retreated to new sites to stay ahead of the advancing Germans. It eventually settled in at Bertangles

Bertangles () is a commune in the Somme department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

Geography

Bertangles is situated on the D97 road, just off the N25, north of Amiens. A farming area with extensive woodland and a grand chateau.

Populat ...

, where it would remain for some time. Park was well respected by his men although he tended not form close relationships with those under his command.

The squadron was carrying out low level attacks on German troops and positions, in addition to its reconnaissance work. The Bristol fighter was poorly suited for the former role, having limited maneuverability at low altitude. At one point in the later stages of the German advance, the squadron was reduced to three operational aircraft, the rest having been damaged or destroyed by ground fire.

By November, the strain of command had all but exhausted Park. On 9 November, in a fatigued state, he crashed a Bristol during a test. Two days later, the war ended. He and his observers were credited with 11 aerial victories.

Interwar period

Immediately after the war, on 25 November, Park married Dorothy Parish at Christ Church in Lancaster Gate. Thoughts now turned to his postwar career. Having applied for a permanent commission in theRoyal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

(RAF) earlier in the year, he had heard nothing despite his application having the support of his wing commander. For the time being, he was posted to command of No. 54 Training Depot at Fairlop

Fairlop is a district in the north of Ilford, part of the London Borough of Redbridge in east London. The district consists of fields, forestry and open land providing space for sport/ activity centres (Redbridge Sport Centre), some houses, farml ...

, but was deemed fit only for light flying and ground duties. In February 1919 he applied again for a permanent commission in the RAF. In addition, the same month his father made an application to the Minister of Defence in New Zealand on Park's behalf for a potential role in the military aviation service that was proposed to be formed for the country's defence. However, this proved to be fruitless as a firm decision regarding the service was not made. In the meantime Park also sought employment with a New Zealand firm, the Canterbury Aviation Company which had been formed by Henry Wigram

Sir Henry Francis Wigram (18 January 1857 – 6 May 1934) was a New Zealand businessman, politician and aviation promoter. He is best known for his role in developing a public transport system in Christchurch and as a key player in the establishme ...

, a pioneer of commercial aviation in the country. However, Park was overlooked for the role.

Park went to London Colney

London Colney () is a village and civil parish in Hertfordshire, England. It is located to the north of London, close to Junction 22 of the M25 motorway.

It is near St Albans and part of the St Albans District. At the time of the 2001 census ...

to command the training depot there and also went on a course at the No. 2 School of Navigation and Bomb Dropping. Then, together with a Captain Stewart, in late April he flew a Handley Page 0/400

The Handley Page Type O was a biplane bomber used by Britain during the First World War. When built, the Type O was the largest aircraft that had been built in the UK and one of the largest in the world. There were two main variants, the Handle ...

twin-engined bomber on a circuit of the British Isles, completing the flight in 28 hours, 30 minutes. It was the second such flight of its type, designed to foster public awareness of the RAF. The following month, Park had an adverse medical examination and was deemed to be unfit for further service, notwithstanding the record flight he had just made. He went on leave for rest and two months later sought a re-examination. This graded him fit for ground duties although he was still not able to fly. In the meantime, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Park was finally granted his permanent commission in September, with effect from 1 August, with the rank of flight lieutenant

Flight lieutenant is a junior Officer (armed forces)#Commissioned officers, commissioned rank in air forces that use the Royal Air Force (RAF) RAF officer ranks, system of ranks, especially in Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth countries. I ...

. He was appointed as commander of a store of Handley Page aircraft at Hawkinge. It was not a role that he was satisfied with and he was pleased when in early 1920, he was posted to the newly reformed No. 25 Squadron as a flight commander. At the time, it was the only fighter squadron based in the United Kingdom. Later in the year he took up duties as the commander of the School of Technical Training, based at Manston. During his time there he was promoted to squadron leader. His health also improved. In April 1922 he was one of twenty officers selected to attend the newly formed RAF Staff College

The RAF Staff College may refer to:

*RAF Staff College, Andover (active: 1922 to 1940 and 1948 to 1970)

*RAF Staff College, Bulstrode Park (active: 1941 to 1948)

*RAF Staff College, Bracknell

The RAF Staff College at Bracknell was a Royal Air ...

at Andover

Andover may refer to:

Places Australia

*Andover, Tasmania

Canada

* Andover Parish, New Brunswick

* Perth-Andover, New Brunswick

United Kingdom

* Andover, Hampshire, England

** RAF Andover, a former Royal Air Force station

United States

* Andov ...

. He spent a year here, along with other notable students, including Sholto Douglas

Sholto Douglas was the mythical progenitor of Clan Douglas, a powerful and warlike family in medieval Scotland.

A mythical battle took place: "in 767, between King '' Solvathius'' rightful king of Scotland and a pretender ''Donald Bane''. The vic ...

, with whom he had clashed the previous year over arrangements for flight demonstrations at an air show, and Arthur Portal.

Staff officer

In March 1923, Park's health was sufficiently restored that he was returned to flight duties and two months later he was posted to Egypt on technical duties. Based at Aboukir, he was accompanied by his wife and the couple's young son. Later in the year, he transferred toCairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

, working as a technical staff officer at the headquarters of RAF Middle East

Middle East Command was a command of the Royal Air Force (RAF) that was active during the Second World War. It had been preceded by RAF Middle East, which was established in 1918 by the redesignation of HQ Royal Flying Corps Middle East that ha ...

. In October 1924 he was switched to air staff duties. He became well respected by his commander, Oliver Swann, who advocated for him in 1925 when concerns were raised regarding Park's health. In June 1926, Park and his family, which now included a second son, returned to England. A medical examination at this time graded him as fit for duty.

At the behest of an acquaintance, Air Commodore Felton Holt, Park was posted to the Air Defence of Great Britain

The Air Defence of Great Britain (ADGB) was a RAF command comprising substantial army and RAF elements responsible for the air defence of the British Isles. It lasted from 1925, following recommendations that the RAF take control of homeland air ...

(ADGB) in August. He was to serve on the staff of the commander of the ADGB, Air Marshal Sir John Salmond, with responsibility for 'Operations, Intelligence Mobilization and Combined Training'. The ADGB, based at Uxbridge

Uxbridge () is a suburban town in west London and the administrative headquarters of the London Borough of Hillingdon. Situated west-northwest of Charing Cross, it is one of the major metropolitan centres identified in the London Plan. Uxb ...

, was tasked with the aerial defence of the United Kingdom, and Park was given considerable latitude in developing his role. After 15 months with the ADGB, Park was given a squadron command; he proceeded to Duxford

Duxford is a village in Cambridgeshire, England, about south of Cambridge. It is part of the Hundred Parishes area.

History

The village formed on the banks of the River Cam, a little below its emergence from the hills of north Essex. One of th ...

to lead No. 111 Squadron. A fighter squadron, it operated the Armstrong Whitworth Siskin

The Armstrong Whitworth Siskin was a biplane single-seat fighter aircraft developed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft. It was also the first all-metal fighter to be operated by the Royal Air Force (RA ...

and Park ensured that it worked extensively, routinely recording high flying hours during his tenure in command. While commanding the squadron, he was involved in one incident on 7 February 1928, he crashed a Siskin while landing at night. In the ensuing investigation, he conceded his night vision was flawed and thereafter did not fly at night.

Promoted to wing commander on 1 January 1929, he was posted back to Uxbridge on staff duties two months later. For two years running he helped in the organisation of the air pageants at Hendon, which drew over 100,000 spectators, and he was also involved in the development of systems for controlling the operations of fighter aircraft defending the United Kingdom from aerial attacks. His senior officer at this time was Air Vice Marshal Hugh Dowding

Air Chief Marshal Hugh Caswall Tremenheere Dowding, 1st Baron Dowding, (24 April 1882 – 15 February 1970) was an officer in the Royal Air Force. He was Air Officer Commanding RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain and is generally c ...

. In January 1931, Park was given command of the RAF station at Northolt

Northolt is a town in West London, England, spread across both sides of the A40 trunk road. It is west-northwest of Charing Cross and is one of the seven major towns that make up the London Borough of Ealing. It had a population of 30,304 at ...

, his tenure lasting for 18 months. He then became the chief instructor at the Oxford University Air Squadron (OUAS). A prestigious post, Park was responsible for 75 students, among them Archibald Hope, who later commanded No. 601 Squadron. Hope regarded Park as a good commander of the OUAS as did a junior instructor, the future flying ace Tom Gleave

Group Captain Thomas Percy Gleave CBE (6 September 1908 – June 1993) was a British fighter pilot during the Battle of Britain. He was shot down in his Hurricane the summer of 1940 and grievously burned. He was one of the first patients treated ...

. Many of the students at OUSA, encouraged by Park, would go on to join the RAF. Park was subsequently awarded an honorary Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

degree by Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

in recognition of his services.

South America

In November 1934, Park was dispatched toBuenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

to serve as the Air Attaché for South America. A key part of his role was to facilitate local interest in British aircraft. He had been given notice of his appointment some months prior, which afforded him time to learn Spanish. He was accompanied by his wife but their two children remained in England, attending boarding schools. His wife, Dol, had longstanding connections to Argentina, as members of her family had held diplomatic postings in the country. Soon after his arrival he was promoted to group captain

Group captain is a senior commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force, where it originated, as well as the air forces of many countries that have historical British influence. It is sometimes used as the English translation of an equivalent rank i ...

. He travelled throughout the continent, visiting aircraft factories and air bases, and promoting British aircraft, military and civilian. It was tough work since American aircraft manufacturers dominated the scene and he was not helped by the Air Ministry's commitment to expanding the RAF in preference to aircraft sales to foreign countries. Nonetheless, the skills he learnt in the role, ranging from mixing with military personnel of all ranks to rapid inspections of air bases, would prove beneficial in the future.

Fighter Command

Park was appointed Air Aide-de-Camp toKing George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of In ...

in early 1937. By this time, he was back in the United Kingdom and attending the Imperial Defence College, which was close to Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

. The course at the Imperial Defence College was designed to enhance the knowledge of its students, mostly senior officers from the British armed forces, in staff, diplomacy and political matters. Park became known for being a questioning student, and demanding of guest lecturers. At the end of the year, he became commander of the RAF station at Tangmere

Tangmere is a village, civil parish, and electoral ward in the Chichester District of West Sussex, England. Located three miles (5 km) north east of Chichester, it is twinned with Hermanville-sur-Mer in Lower Normandy, France.

The parish h ...

, which was home to two fighter squadrons plus a bomber unit. Then in April 1938, he took ill with streptococcal pharyngitis; this meant that he did not take up his next posting in Palestine, which instead went to Arthur Harris, future leader of Bomber Command. Park, after a period of rest, then took the role that had been intended for Harris: Senior Air Staff Officer (SASO) to Hugh Dowding, the commander of Fighter Command, which had been formed in July 1936, following the splitting up of the ADGB.

Park took up his new appointment in May, and this coincided with a promotion to air commodore. He was now based at Bentley Priory

Bentley Priory is an eighteenth to nineteenth century stately home and deer park in Stanmore on the northern edge of the Greater London area in the London Borough of Harrow.

It was originally a medieval priory or cell of Augustinian Canons in ...

, second-in-command to Dowding. The two worked well together as they worked towards improving the operational efficiency of Fighter Command and the integration of radio direction finding

Direction finding (DF), or radio direction finding (RDF), isin accordance with International Telecommunication Union (ITU)defined as radio location that uses the reception of radio waves to determine the direction in which a radio stati ...

(RDF) techniques into the tactical handling of fighters to counter incoming bombers. One notable improvement made by Park in the control of RAF fighters over the southeast of England was better vetting of data that made it to the plotting tables on which movement of both friendly and enemy aircraft were shown. Dowding had been resistant to Park's suggestion to filter out some data but he was then convinced of its merits when Park did unauthorised test trials and showed the results to Dowding. The plotting tables, now less cluttered, made for more effective decision making.

With the blessing of Dowding, Park also worked on an air tactics manual for Fighter Command. As part of this he favoured the replacement of the rifle calibre machine guns that equipped the Hurricane and Spitfire with heavy machine guns, but was overruled. He was also against the use of the conventional 'Vic' formation used by the RAF, in which three fighter aircraft flew in a V-formation, on the basis that these were not suited for monoplanes and wanted to explore alternatives. Despite his best efforts the Air Ministry maintained its existing approach to fighter tactics.

Second World War

Following the outbreak of the Second World War, Park supported Dowding in his efforts to retain as many fighter aircraft as possible for the aerial defence of the United Kingdom. This was despite the requests for fighter squadrons to support the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) dispatched to France shortly after the commencement of hostilities. During the Phoney War, there was great urgency in developing and implementing tactics for the defence of British airspace, through coordination of data collected from RDF stations, the sightings of the Observer Corps, and the fighters themselves. Promoted to the rank of air vice marshal, Park took command ofNo. 11 Group RAF

No. 11 Group is a group in the Royal Air Force first formed in 1918. It had been formed and disbanded for various periods during the 20th century before disbanding in 1996 and reforming again in 2018. Its most famous service was in 1940 in the Ba ...

, responsible for the fighter defence of London and southeast England, on 13 April 1940. He had only just recovered from an emergency appendectomy. Park's appointment affronted Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, the commander of neighbouring No. 12 Group, which covered the Midlands. However, Park had greater experience with fighters, with most of Leigh-Mallory's career, aside from the three years that he had spent in charge of No. 12 Group, spent in a training role. There were already tensions between Park and Leigh-Mallory; in exercises carried out in the summer of 1939, No. 12 Group had not performed as expected and Park, on behalf of Dowding, raised concerns in this respect.

Dunkirk

At the time, Park took command of No. 11 Group, it was perceived that Leigh-Mallory's No. 12 Group would bear the brunt of the German bombing campaign since it was this area of the British Isles that was closest to Germany. However, the subsequent invasion of the Low Countries on 10 May changed the threat level for the southeast of England. By 24 May the majority of the BEF along with French and Belgian troops had been pushed back and became encircled at Dunkirk. During the subsequentDunkirk evacuation

The Dunkirk evacuation, codenamed Operation Dynamo and also known as the Miracle of Dunkirk, or just Dunkirk, was the evacuation of more than 338,000 Allies of World War II, Allied soldiers during the World War II, Second World War from the bea ...

, codenamed Operation Dynamo, No. 11 Group provided aerial cover under Park's direction. The RAF fighters were disadvantaged, having to operate over from their bases in the southeast of England and without the benefit of radar coverage. At best, they had about 40 minutes of flying time over Dunkirk.

Park operated patrol lines over Dunkirk on 27 May, the first day of the evacuation, but the RAF fighters were heavily outnumbered. They were unable to prevent the bombing of Dunkirk itself, but were able to provide some limited protection of the moles and ships. The following day, under orders from the Chief of the Air Staff (CAS), Air Chief Marshal

Air chief marshal (Air Chf Mshl or ACM) is a high-ranking air officer originating from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence. An air chief marshal is equivalent to an Admi ...

Cyril Newall, fighters attempted to provide continuous coverage throughout the day but were unable to do so due to their relatively limited numbers. Park advocated for the usage of at least two squadrons at a time in stronger patrols rather than the continuous coverage. This was based on his own observations from flying his personal Hurricane over Dunkirk. His approach was put into effect the next day, sometimes using as many four squadrons, with greater intervals between patrols. Although there was some pressure from Newall and Churchill for a stronger RAF presence over the beachhead, Dowding sheltered Park from this influence and left him to his work. In the later stages of Operation Dynamo, which ended on 4 June, weather and the pressure from the advancing Germans forced the evacuation efforts to be concentrated on the times around dawn and dusk, and Park's fighters were able to operate more effectively.

Throughout this time, Park not only flew his Hurricane to Dunkirk to see the situation for himself, but he also visited airfields and met with RAF personnel, both pilots and groundcrew. He was very recognisable, wearing white overalls when flying. This helped foster his reputation within No. 11 Group. He also maintained a desire to switch to the offensive; just two weeks after Dunkirk, he sought to have some Hurricane squadrons refitted as fighter-bombers and used along with Bristol Blenheims, to make nighttime attack on the German airfields in France. Dowding did not approve.

Battle of Britain

Being responsible for the south-eastern England area, including London, No. 11 Group faced the majority of theLuftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

's air strength, at least 1,000 bombers and 400 fighters, during the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

. To counter this, at the start of the battle Park had at his disposal 350 fighters across 22 fighter squadrons and just over 550 pilots. Under Park's direction, these fighter squadrons were scrambled against incoming German bombers. Using the plotting tables at his headquarters at Uxbridge, he had to assess which raids were a real threat and which were diversionary in nature, intended to draw away RAF fighters. Timing was important; incoming raids needed to be intercepted before reaching their targets. An understanding of what aircraft were available was also critical. He needed to ensure that there were as many as possible in the air to counter the German bombers but also to avoid having too many on the ground being refueled and rearmed. Even with the benefit of radar, Park was still disadvantaged. He usually had only around 20 minutes from when radar detected the buildup of the incoming bombers over the Pas de Calais or Cotentin regions to scramble his squadrons and have them at a suitable height for interception.

At the start of the Battle of Britain, generally deemed by British historians to be 10 July (German sources usually cite a date in August), the Luftwaffe's initial focus was to gain air superiority over the English Channel, before moving to strike targets inland of the coastline. Its targets were shipping convoys moving through the Channel as well as the ports in the south of England. It was not until 1 August, when Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of Britain, that the Luftwaffe escalated its aerial operations. At this time, the coastal radar stations were targeted, as well as airfields and aircraft manufacturing facilities. This placed further pressure on Park and how he dispersed his fighter squadrons.

On 16 August, following a visit to Park's headquarters at Uxbridge, Winston Churchill made a speech in which he recited one of his most famous lines, referring to RAF fighter pilots: "Never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few". Churchill, who thought well of Park, made another visit to Uxbridge the following month, on 15 September. His visit coincided with the Luftwaffe's greatest daytime raid on England. Churchill noted the large numbers of incoming German aircraft but was reassured with Park's calm reply that RAF forces would meet them. He put up all his aircraft, leaving no reserve and they were joined by 60 fighters from No. 12 Group. It was the first time that the RAF and the Luftwaffe would meet in nearly equal numbers. The Luftwaffe's attack was a significant failure and an even larger raid was mounted later in the afternoon and was also unsuccessful. The date of 15 September subsequently became known as Battle of Britain Day.

By this time, the Luftwaffe had switched from attacking the RAF airfields to London itself. The Germans believed that Fighter Command was largely exhausted but the change in tactics was welcomed as both Park and Dowding recognised that it would be a relief for their pilots. Park later remarked to Alan Mitchell, a New Zealand journalist: "The Hun lost the Battle of Britain when he switched from bombing my fighter-stations to bombing London...".

Big Wings controversy

As the Battle of Britain progressed, Park had increasing concerns about Leigh-Mallory's handling of No. 12 Group. Oftentimes, Park's airfields were left exposed to attack while his squadrons were in the air. Requests to No. 12 Group for aerial cover were often inadequately responded to. This was due to Leigh-Mallory encouraging the use of "Big Wings" in his group; this involved the assembling of three or more squadrons in a single formation before they were directed onto approaching German bombers. By the time the Big Wing was assembled, often Park's undefended airfields had already been attacked and the German bombers on their way back to their bases in France. Leigh-Mallory believed that this was justified as the assembled Big Wing would theoretically inflict significant losses on the departing bombers. Park was not opposed to the use of squadrons en masse and had even used comparable tactics while defending the evacuation of the beaches at Dunkirk a few months previously. However, he recognised that the short time between the detection of the approaching German bombers and them reaching their targets in southeast England meant that Big Wings were not practical. Park preferred greater control over individual squadrons. This allowed him to be more responsive to changes in tactics by the Luftwaffe which might, for example, send one group of bombers to a certain target as a diversion to draw in RAF fighters while another group of bombers attacked the actual target. A report that Leigh-Mallory had sent to the Air Ministry, which overinflated claims made by No. 12 Group when operating the "Big Wing", had found a receptive audience at senior levels of the RAF. Park sent his own report on recent operations during the August-September period, which included critical comments on the Air Ministry's efforts in repairing damaged airfields. Underlying this was increasing tensions between Dowding and the Air Ministry over Fighter Command's ability to deal with the Luftwaffe's night bombing campaign. Sholto Douglas, the deputy CAS, felt Dowding was inadequately dealing with the situation. On 17 October, Dowding and Park attended a meeting, chaired by Douglas, to discuss fighter tactics at the Air Ministry in London. Senior RAF personnel were present, including Leigh-Mallory, but so was the relatively junior Squadron Leader Douglas Bader, a firm advocate for the "Big Wing". Neither Park nor Dowding had expected this nor thought to invite an officer with a contrary front-line experience. Park found himself having to justify his interception tactics and explain why the "Big Wing" was not an appropriate tactic for his area of operations. Leigh-Mallory countered, stating his desire to help No. 11 Group and promising good response times for assembly of the Big Wing. In the absence of any protest from Dowding, Douglas approved of the use of Big Wings over No. 11 Group.Relief

On 7 December, Park was formally replaced as commander of No. 11 Group, his successor being Leigh-Mallory. The decision had been made late the previous month. Officially, this was because Park needed a rest from the stress of the past several months. However, Park believed his relief was due to the dispute with Leigh-Mallory. Historian John Ray, in his account of Dowding's handling of the Battle of Britain argues that Park was seen at the Air Ministry as being closely aligned with Dowding, implementing the latter's defensive scheme. Dowding, already overdue for his retirement, had been released from his post on 17 November and once he went, Park had to follow to enable a fresh start at Fighter Command. Douglas took over Fighter Command and Leigh-Mallory No. 11 Group. On learning of Park's impending departure from No. 11 Group, Air Vice MarshalRichard Saul

Air Vice-Marshal Richard Ernest Saul, (16 April 1891 – 30 November 1965) was a pilot during the First World War and a senior Royal Air Force commander during the Second World War.

Earlier years

Saul was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1891. He ...

, who led No. 13 Group, wrote to Park and noted "the magnificent achievements of your group in the past six months; they have borne the brunt of the war, and undoubtedly saved England". Park himself felt that Saul should have taken over No. 11 Group instead of Leigh-Mallory, on the basis the former was much more familiar with the various RAF stations in the area. The news of Park's dismissal was met with dismay amongst his command. Wing Commander Victor Beamish wrote to Park, advising that the regret at his departure was across all ranks. According to Park, on his final day at No. 11 Group, he had to formally brief Leigh-Mallory's SASO rather Leigh-Mallory himself, who had not attended.

Shortly after his relief, on 17 December it was publicly announced that Park had been appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath. Published in ''The London Gazette'', a statement said the award was "in recognition of distinguished services rendered in recent operations". Despite this reward, Park was angry at his treatment by the Air Ministry and his opinion for the reason for his relief was reinforced by comments from colleagues that unofficial reports had been made about Park's poor relationship with Leigh-Mallory. Late the following year he wrote to Air Chief Marshal Charles Portal

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Charles Frederick Algernon Portal, 1st Viscount Portal of Hungerford, (21 May 1893 – 22 April 1971) was a senior Royal Air Force officer. He served as a bomber pilot in the First World War, and rose to become fi ...

, the current CAS who had made the decision to replace Park with Leigh-Mallory, arguing his case. Portal promptly replied with assurances that his decision had nothing to do with Leigh-Mallory and was simply a matter of Park's health. Churchill was angered at the treatment of Park, and Dowding, by the Air Ministry's publication in March 1941 of a pamphlet on the Battle of Britain, in which neither officer was mentioned. A subsequent republication of the pamphlet, in an illustrated form, remedied this omission.

Training Command

Declining an assignment to the Air Ministry, Park was posted to Training Command, becoming commander of No. 23 Group. His command, centered on RAF South Cerney, encompassed seven service flying training schools, the Central Flying School at Upavon and the School of Air Navigation, at St Athan. It was later expanded with the addition of the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment and the Blind Approach Development Unit, both at RAF Boscombe Down. When he arrived at his command on 27 December, he immediately noted deficiencies in its procedures as it had not moved to a wartime footing. There were personnel within No. 23 Group who were quite unaware of the urgent need for trained pilots during the Battle of Britain. Park moved immediately to remedy the situation. As he had at No. 11 Group, Park regularly flew himself to the various stations of his command. Within a month of his arrival, he had visited each unit under his command at least once, seeing for himself their state of readiness. He improved operational efficiencies, introduced new equipment and modernised aerodromes. At times, there was an embedded cultural resistance within Training Command for change which he had to overcome. By the end of 1941, overseas training establishments were coming on steam and Park was looking ahead to a potential return to frontline duties. In December, he was given a posting to Iraq as Air Officer, Commanding (AOC). However, within a matter of days, this was changed, and he instead proceeded to Egypt to become AOC there. In his new role, he was responsible for the aerial defence of the Nile Delta region, duties that were similar to what he performed as commander of No. 11 Group although he now had night fighters under his control. The Luftwaffe, flying from bases in theGreek islands

Greece has many islands, with estimates ranging from somewhere around 1,200 to 6,000, depending on the minimum size to take into account. The number of inhabited islands is variously cited as between 166 and 227.

The largest Greek island by a ...

, became more aggressive in its aerial operations against targets in Egypt which threatened the buildup of Allied forces in the region. The efficiency and coordination of Egypt's defences were much improved by Park and better able to deal with incoming bombing raids.

Malta

On 8 July 1942, Park relinquished command in Egypt and went to Malta on 14 July as a replacement for Hugh Lloyd, the RAF commander on the besieged island. It was felt that his experience of fighter defence operations was needed. Arriving by flying boat, he landed in the midst of a raid although Lloyd had specifically requested he circle the harbour until it had passed. Lloyd met Park and admonished him for taking an unnecessary risk.

Park abandoned the defensive approach taken by Lloyd, in which the island's fighters took off, circled behind the approaching enemy bombers and engaged them over Malta. Park, having plenty of Spitfires on hand, sought to intercept and break up the German and Italian bomber formations before they reached Malta. One squadron would endeavour to engage the fighters providing high cover for the bombers, another would deal with the closer escorting fighters and the third would seek out the bombers directly. Using these tactics, similar what had been employed by his No. 11 Group during the Battle of Britain, Park believed that it would be more likely that the enemy would be shot down or abort their objectives. His forces began implementing what Park called his ''Forward Interception Plan'' on 25 July. It was immediately successful, for within a week, daylight raids had ceased. The Axis response was to send in fighter sweeps at even higher altitudes to gain the tactical advantage. Park retaliated by ordering his fighters to climb no higher than . This conceded a considerable height advantage to the enemy fighters, but forced them to engage the Spitfires at altitudes more suitable for the latter.

By September the Axis's aerial operations against Malta were on the decline and the British regained air superiority over the island. Shortly, RAF bomber and torpedo squadrons returned to Malta in anticipation of offensive operations against German forces in North Africa. Park dispatched Hurricane fighter bombers, fitted with extra fuel tanks, to attack enemy supply lines as far away as Egypt. Vickers Wellington medium bombers and Bristol Beaufort

On 8 July 1942, Park relinquished command in Egypt and went to Malta on 14 July as a replacement for Hugh Lloyd, the RAF commander on the besieged island. It was felt that his experience of fighter defence operations was needed. Arriving by flying boat, he landed in the midst of a raid although Lloyd had specifically requested he circle the harbour until it had passed. Lloyd met Park and admonished him for taking an unnecessary risk.

Park abandoned the defensive approach taken by Lloyd, in which the island's fighters took off, circled behind the approaching enemy bombers and engaged them over Malta. Park, having plenty of Spitfires on hand, sought to intercept and break up the German and Italian bomber formations before they reached Malta. One squadron would endeavour to engage the fighters providing high cover for the bombers, another would deal with the closer escorting fighters and the third would seek out the bombers directly. Using these tactics, similar what had been employed by his No. 11 Group during the Battle of Britain, Park believed that it would be more likely that the enemy would be shot down or abort their objectives. His forces began implementing what Park called his ''Forward Interception Plan'' on 25 July. It was immediately successful, for within a week, daylight raids had ceased. The Axis response was to send in fighter sweeps at even higher altitudes to gain the tactical advantage. Park retaliated by ordering his fighters to climb no higher than . This conceded a considerable height advantage to the enemy fighters, but forced them to engage the Spitfires at altitudes more suitable for the latter.

By September the Axis's aerial operations against Malta were on the decline and the British regained air superiority over the island. Shortly, RAF bomber and torpedo squadrons returned to Malta in anticipation of offensive operations against German forces in North Africa. Park dispatched Hurricane fighter bombers, fitted with extra fuel tanks, to attack enemy supply lines as far away as Egypt. Vickers Wellington medium bombers and Bristol Beaufort torpedo bombers

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

attacked ports, shipping and airfields, disrupting the Axis supply routes. In October, the Axis resumed its bomber offensive against the island but this was more effectively resisted using Park's tactics although some bombers still managed to attack some targets on Malta.

With supplies more regularly getting through to Malta, offensive operations in support of the Allied campaign in North Africa increased under Park's direction. More bombers arrived and these attacked targets in Algeria ahead of Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – 16 November 1942) was an Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa while al ...

and, later on, in Tunisia. There were also sorties against targets in Sicily and Sardinia. On 27 November, Park's appointment as a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire was announced. This was "in recognition of distinguished services in the campaign in the Middle East". At times his relations with senior officials on Malta was testy; for example, Vice Admiral Power described Park as "unsatisfactory to deal with". However Park's work was also complimented, with both the American General Dwight Eisenhower and British General Bernard Montgomery appreciative of the RAF's operations from Malta in support of their ground forces in North Africa.

The operations of the RAF forces in Malta against Sicily became increasingly important into 1943; the Italian island was a major departure point for shipping taking supplies to the Axis forces in Tunisia. By the end of May, Park had 600 modern aircraft under his control, three times what he had at the start of the year. Additionally, the RAF facilities on Malta had undergone significant expansion in anticipation of the island serving as a major airbase in support of an Allied offensive against Italy. This began with the invasion of Sicily on 10 July, a campaign which lasted less than six weeks. Prior to its commencement, Park arranged the construction of a control room at Malta. From here, he controlled the aerial operations of the aircraft under his command, which amounted to 40 squadrons based at Malta, Gozo and Pantelleria. In September, Park went to London on leave and while there, agitated for a new posting. Portal, still the CAS, thought that Park could become head of the Northwest African Tactical Air Force The Northwest African Tactical Air Force (NATAF) was a component of the Northwest African Air Forces which itself reported to the Mediterranean Air Command (MAC). These new Allied air force organizations were created at the Casablanca Conference ...

, replacing another New Zealander, Arthur Coningham. However, Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Arthur William Tedder, 1st Baron Tedder, (11 July 1890 – 3 June 1967) was a senior Royal Air Force commander. He was a pilot and squadron commander in the Royal Flying Corps in the First World War and he went on ...

, commander of Mediterranean Air Command

The Mediterranean Air Command (MAC) was a World War II Allied air-force command that was active in the North African and Mediterranean Theater of Operations (MTO) between February 18 and December 10, 1943 . MAC was under the command of Air Chi ...

, preferred another candidate. Park was then slated to go to India as the air officer in charge of administration. However, when the proposed appointment went to Winston Churchill for approval, he preferred Park remain where he was for the time being.

Middle East

In January 1944, Park was promoted to the rank of air marshal and was appointed air officer commander-in-chief ofMiddle East Command

Middle East Command, later Middle East Land Forces, was a British Army Command established prior to the Second World War in Egypt. Its primary role was to command British land forces and co-ordinate with the relevant naval and air commands to ...