Karma in Jainism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Karma is the basic principle within an overarching psycho-cosmology in

Karma is the basic principle within an overarching psycho-cosmology in

The Jain texts postulate four ''gatis'', that is states-of-existence or birth-categories, within which the soul transmigrates. The four ''gatis'' are: ''

The Jain texts postulate four ''gatis'', that is states-of-existence or birth-categories, within which the soul transmigrates. The four ''gatis'' are: ''

According to the Jain theory of karma, the karmic matter imparts a colour (''leśyā'') to the soul, depending on the mental activities behind an action. The coloring of the soul is explained through the analogy of crystal, that acquires the color of the matter associated with it. In the same way, the soul also reflects the qualities of taste, smell and touch of associated karmic matter, although it is usually the colour that is referred to when discussing the ''leśyās''. ''Uttarādhyayana-sūtra'' 34.3 speaks of six main categories of ''leśyā'' represented by six colours: black, blue, grey, yellow, red and white. The black, blue and grey are inauspicious ''leśyā'', leading to the soul being born into misfortunes. The yellow, red and white are auspicious ''leśyās'', that lead to the soul being born into good fortune. ''Uttarādhyayana-sūtra'' describes the mental disposition of persons having black and white ''leśyās'':

The Jain texts further illustrate the effects of ''leśyās'' on the mental dispositions of a soul, using an example of the reactions of six travellers on seeing a fruit-bearing tree. They see a tree laden with fruit and begin to think of getting those fruits: one of them suggests uprooting the entire tree and eating the fruit; the second one suggests cutting the trunk of the tree; the third one suggests simply cutting the branches; the fourth one suggests cutting the twigs and sparing the branches and the tree; the fifth one suggests plucking only the fruits; the sixth one suggests picking up only the fruits that have fallen down. The thoughts, words and bodily activities of each of these six travellers are different based on their mental dispositions and are respectively illustrative of the six ''leśyās''. At one extreme, the person with the black ''leśyā'', having evil disposition, thinks of uprooting the whole tree even though he wants to eat only one fruit. At the other extreme, the person with the white ''leśyā'', having a pure disposition, thinks of picking up the fallen fruit, in order to spare the tree.

According to the Jain theory of karma, the karmic matter imparts a colour (''leśyā'') to the soul, depending on the mental activities behind an action. The coloring of the soul is explained through the analogy of crystal, that acquires the color of the matter associated with it. In the same way, the soul also reflects the qualities of taste, smell and touch of associated karmic matter, although it is usually the colour that is referred to when discussing the ''leśyās''. ''Uttarādhyayana-sūtra'' 34.3 speaks of six main categories of ''leśyā'' represented by six colours: black, blue, grey, yellow, red and white. The black, blue and grey are inauspicious ''leśyā'', leading to the soul being born into misfortunes. The yellow, red and white are auspicious ''leśyās'', that lead to the soul being born into good fortune. ''Uttarādhyayana-sūtra'' describes the mental disposition of persons having black and white ''leśyās'':

The Jain texts further illustrate the effects of ''leśyās'' on the mental dispositions of a soul, using an example of the reactions of six travellers on seeing a fruit-bearing tree. They see a tree laden with fruit and begin to think of getting those fruits: one of them suggests uprooting the entire tree and eating the fruit; the second one suggests cutting the trunk of the tree; the third one suggests simply cutting the branches; the fourth one suggests cutting the twigs and sparing the branches and the tree; the fifth one suggests plucking only the fruits; the sixth one suggests picking up only the fruits that have fallen down. The thoughts, words and bodily activities of each of these six travellers are different based on their mental dispositions and are respectively illustrative of the six ''leśyās''. At one extreme, the person with the black ''leśyā'', having evil disposition, thinks of uprooting the whole tree even though he wants to eat only one fruit. At the other extreme, the person with the white ''leśyā'', having a pure disposition, thinks of picking up the fallen fruit, in order to spare the tree.

The karmic bondage occurs as a result of the following two processes: ''āsrava'' and ''bandha''. ''Āsrava'' is the inflow of karma. The karmic influx occurs when the particles are attracted to the soul on account of ''

The karmic bondage occurs as a result of the following two processes: ''āsrava'' and ''bandha''. ''Āsrava'' is the inflow of karma. The karmic influx occurs when the particles are attracted to the soul on account of ''

The consequences of karma are inevitable, though they may take some time to take effect. To explain this, a Jain monk, Ratnaprabhacharya says:

The latent karma becomes active and bears fruit when the supportive conditions arise. A great part of attracted karma bears its consequences with minor fleeting effects, as generally most of our activities are influenced by mild negative emotions. However, those actions that are influenced by intense negative emotions cause an equally strong karmic attachment which usually does not bear fruit immediately. It takes on an inactive state and waits for the supportive conditions—like proper time, place, and environment—to arise for it to manifest and produce effects. If the supportive conditions do not arise, the respective karmas will manifest at the end of maximum period for which it can remain bound to the soul. These supportive conditions for activation of latent karmas are determined by the nature of karmas, intensity of emotional engagement at the time of binding karmas and our actual relation to time, place, surroundings. There are certain laws of precedence among the karmas, according to which the fruition of some of the karmas may be deferred but not absolutely barred.

Jain texts distinguish between the effect of the fruition of ''karma'' on a right believer and a wrong believer:

The consequences of karma are inevitable, though they may take some time to take effect. To explain this, a Jain monk, Ratnaprabhacharya says:

The latent karma becomes active and bears fruit when the supportive conditions arise. A great part of attracted karma bears its consequences with minor fleeting effects, as generally most of our activities are influenced by mild negative emotions. However, those actions that are influenced by intense negative emotions cause an equally strong karmic attachment which usually does not bear fruit immediately. It takes on an inactive state and waits for the supportive conditions—like proper time, place, and environment—to arise for it to manifest and produce effects. If the supportive conditions do not arise, the respective karmas will manifest at the end of maximum period for which it can remain bound to the soul. These supportive conditions for activation of latent karmas are determined by the nature of karmas, intensity of emotional engagement at the time of binding karmas and our actual relation to time, place, surroundings. There are certain laws of precedence among the karmas, according to which the fruition of some of the karmas may be deferred but not absolutely barred.

Jain texts distinguish between the effect of the fruition of ''karma'' on a right believer and a wrong believer:

The Jaina Philosophy, Karma Theory

Surendranath Dasgupta, 1940 {{DEFAULTSORT:Karma In Jainism

Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle bein ...

. Human moral actions form the basis of the transmigration of the soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '' soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest att ...

('). The soul is constrained to a cycle of rebirth, trapped within the temporal world ('), until it finally achieves liberation ('). Liberation is achieved by following a path of purification.

Jains believe that karma is a physical substance that is everywhere in the universe. Karma particles are attracted to the soul by the actions of that soul. Karma particles are attracted when we do, think, or say things, when we kill something, when we lie, when we steal and so on. Karma not only encompasses the causality

Causality (also referred to as causation, or cause and effect) is influence by which one event, process, state, or object (''a'' ''cause'') contributes to the production of another event, process, state, or object (an ''effect'') where the cau ...

of transmigration, but is also conceived of as an extremely subtle matter, which infiltrates the soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '' soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest att ...

—obscuring its natural, transparent and pure qualities. Karma is thought of as a kind of pollution, that taints the soul with various colours ('' leśyā''). Based on its karma, a soul undergoes transmigration and reincarnates in various states of existence—like heavens or hells, or as humans or animals.

Jains cite inequalities, sufferings, and pain as evidence for the existence of karma. Various types of karma are classified according to their effects on the potency of the soul. The Jain theory seeks to explain the karmic process by specifying the various causes of karmic influx ('' āsrava'') and bondage ('' bandha''), placing equal emphasis on deeds themselves, and the intentions behind those deeds. The Jain karmic theory attaches great responsibility to individual actions, and eliminates any reliance on some supposed existence of divine grace

Divine grace is a theological term present in many religions. It has been defined as the divine influence which operates in humans to regenerate and sanctify, to inspire virtuous impulses, and to impart strength to endure trial and resist temptat ...

or retribution. The Jain doctrine also holds that it is possible for us to both modify our karma, and to obtain release from it, through the austerities and purity of conduct.

Philosophical overview

According to Jains, all souls are intrinsically pure in their inherent and ideal state, possessing the qualities of infinite knowledge, infinite perception, infinite bliss and infinite energy. However, in contemporary experience, these qualities are found to be defiled and obstructed, on account of the association of these souls with karma. The soul has been associated with karma in this way throughout an eternity of beginning-less time. This bondage of the soul is explained in theJain texts

Jain literature (Sanskrit: जैन साहित्य) refers to the literature of the Jain religion. It is a vast and ancient literary tradition, which was initially transmitted orally. The oldest surviving material is contained in the c ...

by analogy with gold ore, which—in its natural state—is always found unrefined of admixture with impurities. Similarly, the ideally pure state of the soul has always been overlaid with the impurities of karma. This analogy with gold ore is also taken one step further: the purification of the soul can be achieved if the proper methods of refining are applied. Over the centuries, Jain monks

Jain monasticism refers to the order of monks and nuns in the Jain community and can be divided into two major denominations: the '' Digambara'' and the '' Śvētāmbara''. The monastic practices of the two major sects vary greatly, but the ...

have developed a large and sophisticated corpus of literature describing the nature of the soul, various aspects of the working of karma, and the ways and means of attaining '. ''Tirthankara-nama-karma'' is a special type of karma, bondage of which raises a soul to the supreme status of a ''tirthankara''.

Material theory

Jainism speaks of karmic "dirt", as karma is thought to be manifest as very subtle and sensually imperceptible particles pervading the entire universe. They are so small that one space-point—the smallest possible extent of space—contains an infinite number of karmic particles (or quantity of karmic dirt). It is these karmic particles that adhere to the soul and affect its natural potency. This material karma is called ''dravya karma''; and the resultant emotions—pleasure, pain, love, hatred, and so on—experienced by the soul are called ''bhava karma'', psychic karma. The relationship between the material and psychic karma is that of cause and effect. The material karma gives rise to the feelings and emotions in worldly souls,Jain philosophy

Jain philosophy refers to the ancient Indian philosophical system found in Jainism. One of the main features of Jain philosophy is its dualistic metaphysics, which holds that there are two distinct categories of existence, the living, consciou ...

categorises the souls ''jivas'' into two categories: worldly souls, who are unliberated; and liberated souls, who are free from all karma. which—in turn—give rise to psychic karma, causing emotional modifications within the soul. These emotions, yet again, result in influx and bondage of fresh material karma. Jains hold that the karmic matter is actually an agent that enables the consciousness to act within the material context of this universe. They are the material carrier of a soul's desire to physically experience this world. When attracted to the consciousness, they are stored in an interactive karmic field called ', which emanates from the soul. Thus, karma is a subtle matter surrounding the consciousness of a soul. When these two components—consciousness and ripened karma—interact, the soul experiences life as known in the present material universe.

Self regulating mechanism

According toIndologist

Indology, also known as South Asian studies, is the academic study of the history and cultures, languages, and literature of the Indian subcontinent, and as such is a subset of Asian studies.

The term ''Indology'' (in German, ''Indologie'') i ...

Robert J. Zydenbos

Robert J. Zydenbos (born 1957) is a Dutch-Canadian scholar who has doctorate degrees in Indian philosophy and Dravidian studies. He also has a doctorate of literature from the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands. Zydenbos also studied Indi ...

, karma is a system of natural laws, where actions that carry moral significance are considered to cause certain consequences in the same way as physical actions. When one holds an apple and then lets it go, the apple will fall. There is no judge, and no moral judgment involved, since this is a mechanical consequence of the physical action. In the same manner, consequences occur naturally when one utters a lie, steals something, commits senseless violence or leads a life of debauchery. Rather than assume that these consequences—the moral rewards and retributions—are a work of some divine judge, Jains believe that there is an innate moral order in the cosmos, self-regulating through the workings of the law of karma. Morality and ethics are important in Jainism not because of a God, but because a life led in agreement with moral and ethical principles (''mahavrata

Jain ethical code prescribes two ''dharmas'' or rules of conduct. One for those who wish to become ascetic and another for the ''śrāvaka'' (householders). Five fundamental vows are prescribed for both votaries. These vows are observed by '' � ...

'') is considered beneficial: it leads to a decrease—and finally to the total loss of—karma, which in turn leads to everlasting happiness. The Jain conception of karma takes away the responsibility for salvation from God and bestows it on man himself. In the words of the Jain scholar, J. L. Jaini:

Predominance of karma

According to Jainism, karmic consequences are unerringly certain and inescapable. No divine grace can save a person from experiencing them. Only the practice of austerities and self-control can modify or alleviate the consequences of karma. Even then, in some cases, there is no option but to accept karma with equanimity. The second-century Jain text, ''Bhagavatī Ārādhanā'' (verse no. 1616) sums up the predominance of karma in Jain doctrine: This predominance of karma is a theme often explored by Jain ascetics in the literature they have produced, throughout all centuries. Paul Dundas notes that the ascetics often usedcautionary tale

A cautionary tale is a tale told in folklore to warn its listener of a danger. There are three essential parts to a cautionary tale, though they can be introduced in a large variety of ways. First, a taboo or prohibition is stated: some act, lo ...

s to underline the full karmic implications of morally incorrect modes of life, or excessively intense emotional relationships. However, he notes that such narratives were often softened by concluding statements about the transforming effects of the protagonists' pious actions, and their eventual attainment of liberation.

The biographies of legendary persons like Rama

Rama (; ), Ram, Raman or Ramar, also known as Ramachandra (; , ), is a major deity in Hinduism. He is the seventh and one of the most popular '' avatars'' of Vishnu. In Rama-centric traditions of Hinduism, he is considered the Supreme Bei ...

and Krishna

Krishna (; sa, कृष्ण ) is a major deity in Hinduism. He is worshipped as the eighth avatar of Vishnu and also as the Supreme god in his own right. He is the god of protection, compassion, tenderness, and love; and is on ...

, in the Jain versions of the epics ''Ramayana

The ''Rāmāyana'' (; sa, रामायणम्, ) is a Sanskrit epic composed over a period of nearly a millennium, with scholars' estimates for the earliest stage of the text ranging from the 8th to 4th centuries BCE, and later stages ...

'' and ''Mahabharata

The ''Mahābhārata'' ( ; sa, महाभारतम्, ', ) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India in Hinduism, the other being the '' Rāmāyaṇa''. It narrates the struggle between two groups of cousins in the K ...

'',

"The first Jain version of the ' was written in about the fourth century CE in by ." see Dundas, Paul (2002): pp. 238–39.

"The Jains seem at times to have employed the epic to engage in confrontation with the Hindus. In the sixteenth century, Jain writers in western India produced versions of the ' libelling who, according to another influential Hindu text, the ', had created a fordmaker-like figure who converted the demons to Jain mendicancy, thus enabling the gods to defeat them. Another target of these Jain ' was who ceases to be the pious Jain of early tradition and instead is portrayed as a devious and immoral schemer." see Dundas, Paul (2002): p. 237.

also have karma as one of the major themes. The major events, characters and circumstances are explained by reference to their past lives, with examples of specific actions of particular intensity in one life determining events in the next. Jain texts narrate how even Māhavīra, one of the most popular propagators of Jainism and the 24th ' (ford-maker),The word ' is translated as ''ford-maker'', but is also loosely translated as a ''prophet'' or a ''teacher''. Fording means crossing or wading in the river. Hence, they are called ford-makers because they serve as ferrymen across the river of transmigration. see Grimes, John (1996) p. 320 had to bear the brunt of his previous karma before attaining '' kevala jñāna'' ( enlightenment). He attained it only after bearing twelve years of severe austerity with detachment. The ' speaks of how Māhavīra bore his karma with complete equanimity, as follows:

Reincarnation and transmigration

Karma forms a central and fundamental part of Jain faith, being intricately connected to other of its philosophical concepts like transmigration, reincarnation, liberation, non-violence (''ahiṃsā

Ahimsa (, IAST: ''ahiṃsā'', ) is the ancient Indian principle of nonviolence which applies to all living beings. It is a key virtue in most Indian religions: Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.Bajpai, Shiva (2011). The History of India – F ...

'') and non-attachment, among others. Actions are seen to have consequences: some immediate, some delayed, even into future incarnations. So the doctrine of karma is not considered simply in relation to one life-time, but also in relation to both future incarnations and past lives. '' Uttarādhyayana-sūtra'' 3.3–4 states:

The text further states (32.7):

There is no retribution, judgment or reward involved but a natural consequences of the choices in life made either knowingly or unknowingly. Hence, whatever suffering or pleasure that a soul may be experiencing in its present life is on account of choices that it has made in the past. As a result of this doctrine, Jainism attributes supreme importance to pure thinking and moral behavior.

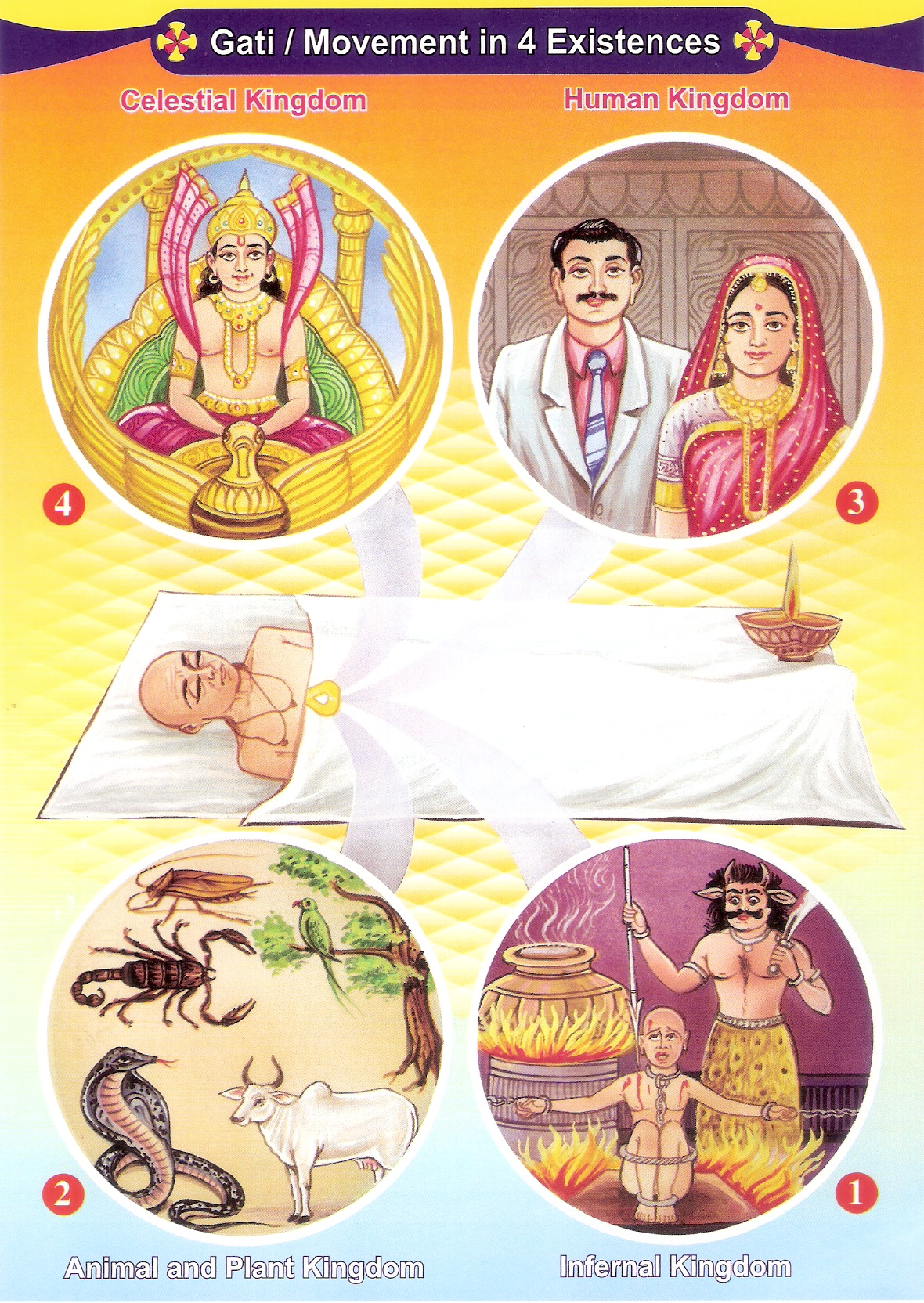

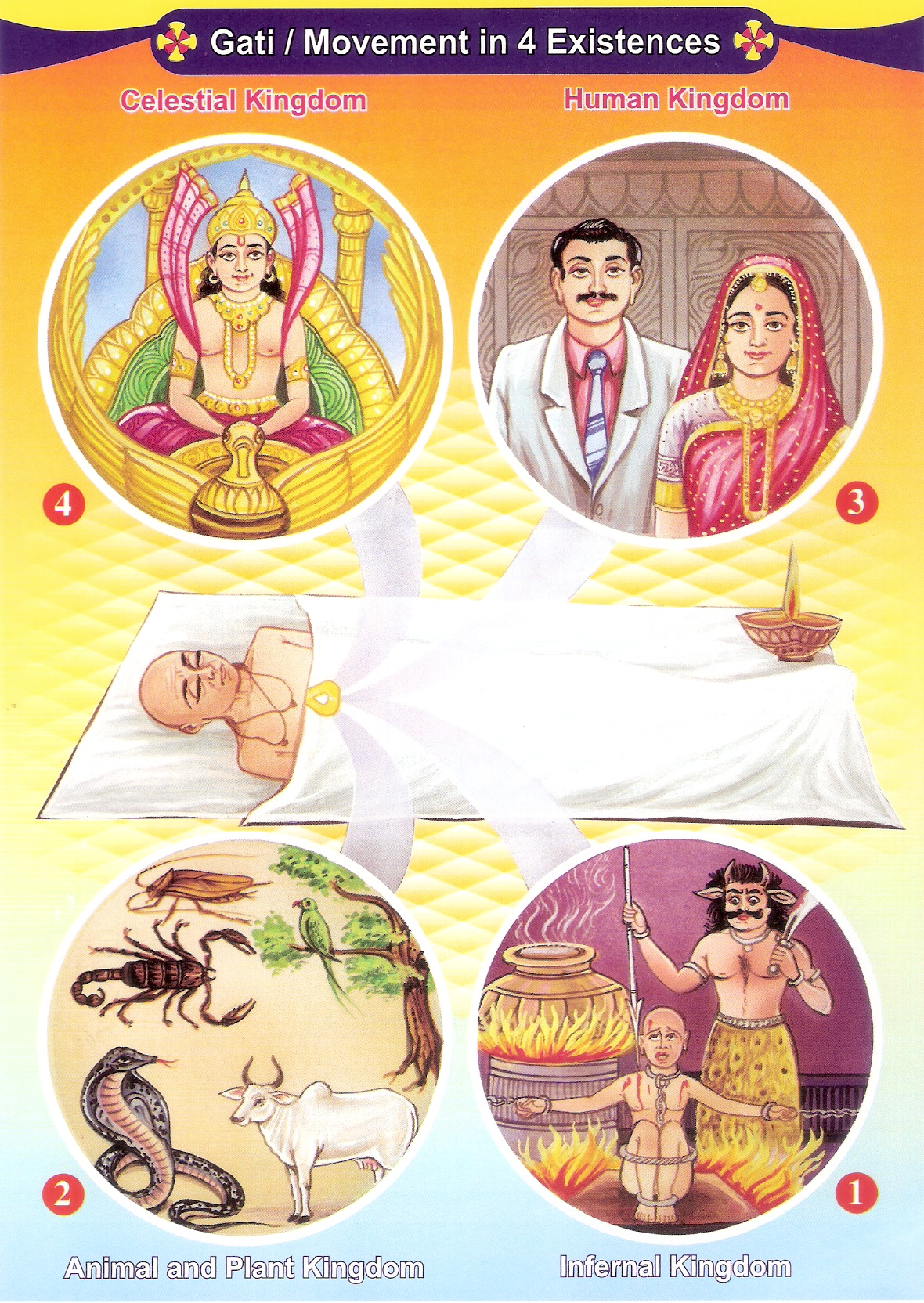

Four Gatis (states of existence)

The Jain texts postulate four ''gatis'', that is states-of-existence or birth-categories, within which the soul transmigrates. The four ''gatis'' are: ''

The Jain texts postulate four ''gatis'', that is states-of-existence or birth-categories, within which the soul transmigrates. The four ''gatis'' are: ''deva

Deva may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Deva'' (1989 film), a 1989 Kannada film

* ''Deva'' (1995 film), a 1995 Tamil film

* ''Deva'' (2002 film), a 2002 Bengali film

* Deva (2007 Telugu film)

* ''Deva'' (2017 film), a 2017 Marathi film

* Deva ...

'' (demi-gods), ''manuṣya'' (humans), '' nāraki'' (hell beings) and ''tiryañca'' (animals, plants and micro-organisms). The four ''gatis'' have four corresponding realms or habitation levels in the vertically tiered Jain universe: demi-gods occupy the higher levels where the heavens are situated; humans, plants and animals occupy the middle levels; and hellish beings occupy the lower levels where seven hells are situated.

Single-sensed souls, however, called '' nigoda'',The Jain hierarchy of life classifies living beings on the basis of the senses: five-sensed beings like humans and animals are at the top, and single sensed beings like microbes and plants are at the bottom. and element-bodied souls pervade all tiers of this universe. ''Nigodas'' are souls at the bottom end of the existential hierarchy. They are so tiny and undifferentiated, that they lack even individual bodies, living in colonies. According to Jain texts, this infinity of ''nigodas'' can also be found in plant tissues, root vegetables and animal bodies. Depending on its karma, a soul transmigrates and reincarnates within the scope of this cosmology of destinies. The four main destinies are further divided into sub-categories and still smaller sub–sub categories. In all, Jain texts speak of a cycle of 8.4 million birth destinies in which souls find themselves again and again as they cycle within '' samsara''.

In Jainism, God has no role to play in an individual's destiny; one's personal destiny is not seen as a consequence of any system of reward or punishment, but rather as a result of its own personal karma. A text from a volume of the ancient Jain canon, '' Bhagvati sūtra'' 8.9.9, links specific states of existence to specific karmas. Violent deeds, killing of creatures having five sense organs, eating fish, and so on, lead to rebirth in hell. Deception, fraud and falsehood leads to rebirth in the animal and vegetable world. Kindness, compassion and humble character result in human birth; while austerities and the making and keeping of vows leads to rebirth in heaven.

There are five types of bodies in the Jain thought: earthly (e.g. most humans, animals and plants), metamorphic (e.g. gods, hell beings, fine matter, some animals and a few humans who can morph because of their perfections), transference type (e.g. good and pure substances realized by ascetics), fiery (e.g. heat that transforms or digests food), and karmic (the substrate where the karmic particles reside and which make the soul ever changing).

Jain philosophy further divides the earthly body by symmetry, number of sensory organs, vitalities (''ayus''), functional capabilities and whether one body hosts one soul or one body hosts many. Every living being has one to five senses, three ''balas'' (power of body, language and mind), respiration (inhalation and exhalation), and life-duration. All living beings, in every realm including the gods and hell beings, accrue and destroy eight types of karma according to the elaborate theories in Jain texts. Elaborate descriptions of the shape and function of the physical and metaphysical universe, and its constituents are also provided in the Jain texts

Jain literature (Sanskrit: जैन साहित्य) refers to the literature of the Jain religion. It is a vast and ancient literary tradition, which was initially transmitted orally. The oldest surviving material is contained in the c ...

. All of these elaborate theories attempt to illustrate and consistently explain the Jain karma theory in a deeply moral framework, much like Buddhism and Hinduism but with significant differences in the details and assumptions.

Lesya – colouring of the soul

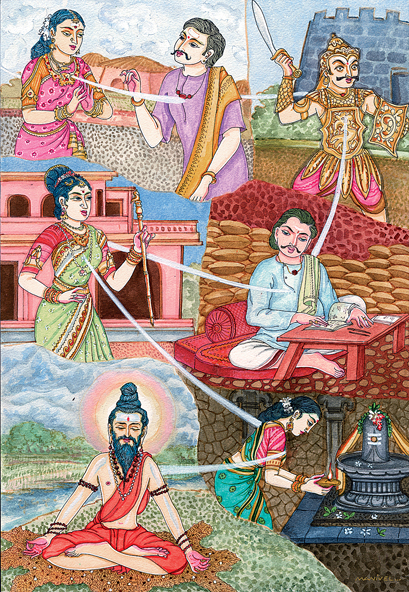

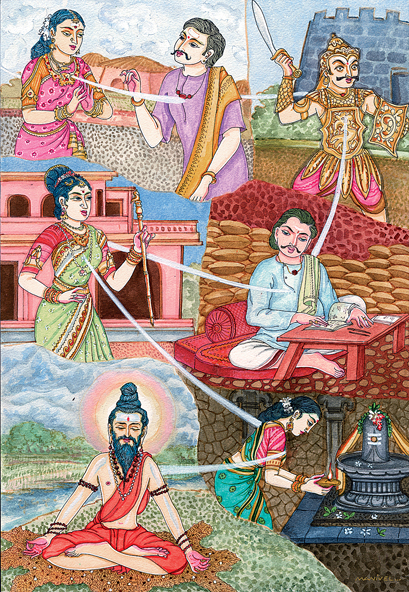

According to the Jain theory of karma, the karmic matter imparts a colour (''leśyā'') to the soul, depending on the mental activities behind an action. The coloring of the soul is explained through the analogy of crystal, that acquires the color of the matter associated with it. In the same way, the soul also reflects the qualities of taste, smell and touch of associated karmic matter, although it is usually the colour that is referred to when discussing the ''leśyās''. ''Uttarādhyayana-sūtra'' 34.3 speaks of six main categories of ''leśyā'' represented by six colours: black, blue, grey, yellow, red and white. The black, blue and grey are inauspicious ''leśyā'', leading to the soul being born into misfortunes. The yellow, red and white are auspicious ''leśyās'', that lead to the soul being born into good fortune. ''Uttarādhyayana-sūtra'' describes the mental disposition of persons having black and white ''leśyās'':

The Jain texts further illustrate the effects of ''leśyās'' on the mental dispositions of a soul, using an example of the reactions of six travellers on seeing a fruit-bearing tree. They see a tree laden with fruit and begin to think of getting those fruits: one of them suggests uprooting the entire tree and eating the fruit; the second one suggests cutting the trunk of the tree; the third one suggests simply cutting the branches; the fourth one suggests cutting the twigs and sparing the branches and the tree; the fifth one suggests plucking only the fruits; the sixth one suggests picking up only the fruits that have fallen down. The thoughts, words and bodily activities of each of these six travellers are different based on their mental dispositions and are respectively illustrative of the six ''leśyās''. At one extreme, the person with the black ''leśyā'', having evil disposition, thinks of uprooting the whole tree even though he wants to eat only one fruit. At the other extreme, the person with the white ''leśyā'', having a pure disposition, thinks of picking up the fallen fruit, in order to spare the tree.

According to the Jain theory of karma, the karmic matter imparts a colour (''leśyā'') to the soul, depending on the mental activities behind an action. The coloring of the soul is explained through the analogy of crystal, that acquires the color of the matter associated with it. In the same way, the soul also reflects the qualities of taste, smell and touch of associated karmic matter, although it is usually the colour that is referred to when discussing the ''leśyās''. ''Uttarādhyayana-sūtra'' 34.3 speaks of six main categories of ''leśyā'' represented by six colours: black, blue, grey, yellow, red and white. The black, blue and grey are inauspicious ''leśyā'', leading to the soul being born into misfortunes. The yellow, red and white are auspicious ''leśyās'', that lead to the soul being born into good fortune. ''Uttarādhyayana-sūtra'' describes the mental disposition of persons having black and white ''leśyās'':

The Jain texts further illustrate the effects of ''leśyās'' on the mental dispositions of a soul, using an example of the reactions of six travellers on seeing a fruit-bearing tree. They see a tree laden with fruit and begin to think of getting those fruits: one of them suggests uprooting the entire tree and eating the fruit; the second one suggests cutting the trunk of the tree; the third one suggests simply cutting the branches; the fourth one suggests cutting the twigs and sparing the branches and the tree; the fifth one suggests plucking only the fruits; the sixth one suggests picking up only the fruits that have fallen down. The thoughts, words and bodily activities of each of these six travellers are different based on their mental dispositions and are respectively illustrative of the six ''leśyās''. At one extreme, the person with the black ''leśyā'', having evil disposition, thinks of uprooting the whole tree even though he wants to eat only one fruit. At the other extreme, the person with the white ''leśyā'', having a pure disposition, thinks of picking up the fallen fruit, in order to spare the tree.

Role of deeds and intent

The role of intent is one of the most important and definitive elements of the karma theory, in all its traditions. In Jainism, intent is important but not an essential precondition of sin or wrong conduct. Evil intent forms only one of the modes of committing sin. Any action committed, knowingly or ''unknowingly'', has karmic repercussions. In certain philosophies, like Buddhism, a person is guilty of violence only if he had an intention to commit violence. On the other hand, according to Jains, if an act produces violence, then the person is guilty of it, whether or not he had an intention to commit it. John Koller explains the role of intent in Jainism with the example of a monk, who unknowingly offered poisoned food to his brethren. According to the Jain view, the monk is guilty of a violent act if the other monks die because they eat the poisoned food; but according to the Buddhist view he would not be guilty. The crucial difference between the two views is that the Buddhist view excuses the act, categorizing it as non-intentional, since he was not aware that the food was poisoned; whereas the Jain view holds the monk to have been responsible, due to his ignorance and carelessness. Jains argue that the monk's very ignorance and carelessness constitute an intent to do violence and hence entail his guilt. So the absence of intent does not absolve a person from the karmic ''consequences'' of guilt either, according to the Jain analysis. Intent is a function of kaṣāya, which refers to negative emotions and negative qualities of mental (or deliberative) action. The presence of intent acts as an aggravating factor, increasing the vibrations of the soul, which results in the soul absorbing more karma. This is explained by ''Tattvārthasūtra

''Tattvārthasūtra'', meaning "On the Nature '' ''artha">nowiki/>''artha''.html" ;"title="artha.html" ;"title="nowiki/>''artha">nowiki/>''artha''">artha.html" ;"title="nowiki/>''artha">nowiki/>''artha''of Reality 'tattva'' (also known as ...

'' 6.7: " heintentional act produces a strong karmic bondage and heunintentional produces weak, shortlived karmic bondage." Similarly, the physical act is also not a necessary condition

In logic and mathematics, necessity and sufficiency are terms used to describe a conditional or implicational relationship between two statements. For example, in the conditional statement: "If then ", is necessary for , because the truth o ...

for karma to bind to the soul: the existence of intent alone is sufficient. This is explained by Kundakunda

Kundakunda was a Digambara Jain monk and philosopher, who likely lived in the 2nd CE century CE or later.

His date of birth is māgha māsa, śukla pakṣa, pañcamī tithi, on the day of Vasant Panchami.

He authored many Jain texts such ...

(1st Century CE) in ''Samayasāra

''Samayasāra'' (''The Nature of the Self'') is a famous Jain text composed by '' Acharya Kundakunda'' in 439 verses. Its ten chapters discuss the nature of '' Jīva'' (pure self/soul), its attachment to Karma and Moksha (liberation). ''Samay ...

'' 262–263: "The intent to kill, to steal, to be unchaste and to acquire property, whether these offences are actually carried or not, leads to bondage of evil karmas." Jainism thus places an equal emphasis on the physical act as well as intent for binding of karmas.

Origins and influence

Although the doctrine of karma is central to allIndian religions

Indian religions, sometimes also termed Dharmic religions or Indic religions, are the religions that originated in the Indian subcontinent. These religions, which include Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism,Adams, C. J."Classification of ...

, it is difficult to say when and where in India the concept of karma originated. In Jainism, it is assumed its development took place in an era from which the literary documents are not available, since the basics of this doctrine were present and concluded even in the earliest documents of Jains. ''Acaranga Sutra

The Acharanga Sutra (; First book c. 5th–4th century BCE; Second book c. 2nd–1st century BCE) is the first of the twelve Angas, part of the agamas (religious texts) which were compiled based on the teachings of 24th Jina Mahavira.

The exi ...

'' and ''Sutrakritanga

Sūtrakṛtāṅga सूत्रकृताङ्ग (also known in Prakrit as Sūyagaḍaṃga सूयगडंग) is the second agama of the 12 main aṅgās of the Jain Svetambara canon. According to the Svetambara tradition it was w ...

'', contain a general outline of the doctrines of karma and reincarnation. The roots of this doctrine in Jainism might be in the teachings of Parsva, who is said to have lived about two hundred fifty years before Mahavira. The Jain conception of karma—as something material that encumbers the soul—has an archaic nature which justifies the hypothesis that it goes back to 8th or 9th century BCE.

The present form of the doctrine seems to be unchanged at least since the time of Bhadrabahu (c. 300 BCE) who is respected by both the sects. This is supported by the fact that both Svetambara and Digambara sects agree on the basic doctrine, giving indication that it reached in its present form before the schism took place. Bhadrabahu is usually seen as the last leader of united Jain sangh. Detailed codification of types of karma and their effects were attested by Umasvati

Umaswati, also spelled as Umasvati and known as Umaswami, was an Indian scholar, possibly between 2nd-century and 5th-century CE, known for his foundational writings on Jainism. He authored the Jain text ''Tattvartha Sutra'' (literally '"All Tha ...

who is regarded by both Digambara and Svetambara as one of theirs.

Jain and Buddhist scholar Padmanabh Jaini

Padmanabh Shrivarma Jaini (October 23, 1923 - May 25, 2021) was an Indian born scholar of Jainism and Buddhism, living in Berkeley, California, United States. He was from a Digambar Jain family; however he was equally familiar with both the ...

observes:

With regards to the influence of the theory of karma on development of various religious and social practices in ancient India, Dr. Padmanabh Jaini states:Padmanabh Jaini, Collected papers on Jaina Studies, Chapter 7, Pg 137

The Jain socio-religious practices like regular fasting, practicing severe austerities and penances, the ritual death of ''Sallekhana

''Sallekhana'' (IAST: ), also known as ''samlehna'', ''santhara'', ''samadhi-marana'' or ''sanyasana-marana'', is a supplementary vow to the ethical code of conduct of Jainism. It is the religious practice of voluntarily fasting to death by ...

'' and rejection of God as the creator and operator of the universe can all be linked to the Jain theory of karma. Jaini notes that the disagreement over the karmic theory of transmigration resulted in the social distinction between the Jains and their Hindu neighbours. Thus one of the most important Hindu rituals, ''śrāddha'' was not only rejected but strongly criticized by the Jains as superstition. Certain authors have also noted the strong influence of the concept of karma on the Jain ethics

Jain ethical code prescribes two ''dharmas'' or rules of conduct. One for those who wish to become ascetic and another for the ''śrāvaka'' (householders). Five fundamental vows are prescribed for both votaries. These vows are observed by '' � ...

, especially the ethics of non-violence. Once the doctrine of transmigration of souls came to include rebirth on earth in animal as well as human form, depending upon one's karmas, it is quite probable that, it created a humanitarian sentiment of kinship amongst all life forms and thus contributed to the notion of ' (non-violence).

Factors affecting the effects of Karma

The nature of experience of the effects of the karma depends on the following four factors: *''Prakriti'' (nature or type of karma) – According to Jain texts, there are eight main types of karma which categorized into the 'harming' and the 'non-harming'; each divided into four types. The harming karmas (''ghātiyā karmas'') directly affect the soul powers by impeding its perception, knowledge and energy, and also brings about delusion. These harming karmas are: ''darśanāvaraṇa'' (perception-obscuring karma), ''jñānavāraṇa'' (knowledge-obscuring karma), ''antarāya'' (obstacle-creating karma) and ''mohanīya'' (deluding karma). The non-harming category (''aghātiyā karmas'') is responsible for the reborn soul's physical and mental circumstances, longevity, spiritual potential and experience of pleasant and unpleasant sensations. These non-harming karmas are: ''nāma'' (body-determining karma), ''āyu'' (lifespan-determining karma), ''gotra'' (status-determining karma) and ''vedanīya'' (feeling-producing karma), respectively. Different types of karmas thus affect the soul in different ways as per their nature. *''Sthiti'' (the duration of the karmic bond) – The karmic bond remains latent and bound to the consciousness up to the time it is activated. Although latent karma does not affect the soul directly, its existence limits the spiritual growth of the soul. Jain texts provide the minimum and the maximum duration for which such karma is bound before it matures. *''Anubhava'' (intensity of karmas) – The degree of the experience of the karmas, that is, mild or intense, depends on the ''anubhava'' quality or the intensity of the bondage. It determines the power of karmas and its effect on the soul. ''Anubhava'' depends on the intensity of the passions at the time of binding the karmas. More intense the emotions—like anger, greed etc.—at the time of binding the karma, the more intense will be its experience at the time of maturity. *''Pradesha'' (The quantity of the karmas) – It is the quantity of karmic matter that is received and gets activated at the time of experience. Both emotions and activity play a part in binding of karmas. Duration and intensity of the karmic bond are determined by emotions or ''" "'' and type and quantity of the karmas bound is depended on ''yoga'' or activity.The process of bondage and release

The karmic process in Jainism is based on seven truths or fundamental principles (''tattva

According to various Indian schools of philosophy, ''tattvas'' () are the Classical element, elements or aspects of reality that constitute human experience. In some traditions, they are conceived as an aspect of deity. Although the number of ' ...

'') of Jainism which explain the human predicament. Out that the seven ''tattvas'', the four—influx ('' āsrava''), bondage ('' bandha''), stoppage (''saṃvara

''Samvara'' (''saṃvara'') is one of the ''tattva'' or the fundamental reality of the world as per the Jain philosophy. It means stoppage—the stoppage of the influx of the material karmas into the soul consciousness. The karmic process in J ...

'') and release ('' nirjarā'')—pertain to the karmic process.

Attraction and binding

The karmic bondage occurs as a result of the following two processes: ''āsrava'' and ''bandha''. ''Āsrava'' is the inflow of karma. The karmic influx occurs when the particles are attracted to the soul on account of ''

The karmic bondage occurs as a result of the following two processes: ''āsrava'' and ''bandha''. ''Āsrava'' is the inflow of karma. The karmic influx occurs when the particles are attracted to the soul on account of ''yoga

Yoga (; sa, योग, lit=yoke' or 'union ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines which originated in ancient India and aim to control (yoke) and still the mind, recognizing a detached witness-consciou ...

''. ''Yoga'' is the vibrations of the soul due to activities of mind, speech and body. However, the ''yoga'' alone do not produce bondage. The karmas have effect only when they are bound to the consciousness. This binding of the karma to the consciousness is called ''bandha''. Out of the many causes of bondage, emotions or passions are considered as the main cause of bondage. The karmas are literally bound on account of the stickiness of the soul due to existence of various passions or mental dispositions. The passions like anger, pride, deceit and greed are called sticky ('' kaṣāyas'') because they act like glue in making karmic particles stick to the soul resulting in ''bandha''. The karmic inflow on account of ''yoga'' driven by passions and emotions cause a long-term inflow of karma prolonging the cycle of reincarnations. On the other hand, the karmic inflows on account of actions that are not driven by passions and emotions have only a transient, short-lived karmic effect. Hence the ancient Jain texts talk of subduing these negative emotions:

Causes of attraction and bondage

The Jain theory of karma proposes that karma particles are attracted and then bound to the consciousness of souls by a combination of four factors pertaining to actions: instrumentality, process, modality and motivation. *The instrumentality of an action refers to whether the instrument of the action was: the body, as in physical actions; one's speech, as inspeech acts

Speech is a human vocal communication using language. Each language uses phonetic combinations of vowel and consonant sounds that form the sound of its words (that is, all English words sound different from all French words, even if they are th ...

; or the mind, as in thoughtful deliberation.

*The process of an action refers to the temporal sequence in which it occurs: the decision to act, plans to facilitate the act, making preparations necessary for the act, and ultimately the carrying through of the act itself.

*The modality of an action refers to different modes in which one can participate in an action, for example: being the one who carries out the act itself; being one who instigates another to perform the act; or being one who gives permission, approval or endorsement of an act.

*The motivation for an action refers to the internal passions or negative emotions that prompt the act, including: anger, greed, pride, deceit and so on.

All actions have the above four factor present in them. When different permutation

In mathematics, a permutation of a set is, loosely speaking, an arrangement of its members into a sequence or linear order, or if the set is already ordered, a rearrangement of its elements. The word "permutation" also refers to the act or pro ...

s of the sub-elements of the four factors are calculated, the Jain teachers speak of 108 ways in which the karmic matter can be attracted to the soul. Even giving silent assent or endorsement to acts of violence from far away has karmic consequences for the soul. Hence, the scriptures advise carefulness in actions, awareness of the world, and purity in thoughts as means to avoid the burden of karma.

According to the major Jain text

Jain literature (Sanskrit: जैन साहित्य) refers to the literature of the Jain religion. It is a vast and ancient literary tradition, which was initially transmitted orally. The oldest surviving material is contained in the ca ...

, ''Tattvartha sutra

''Tattvārthasūtra'', meaning "On the Nature '' ''artha">nowiki/>''artha''.html" ;"title="artha.html" ;"title="nowiki/>''artha">nowiki/>''artha''">artha.html" ;"title="nowiki/>''artha">nowiki/>''artha''of Reality 'tattva'' (also known as ...

'':

The causes of ''bandha'' or the karmic bondage—in the order they are required to be eliminated by a soul for spiritual progress—are:

* ''Mithyātva'' (Irrationality and a deluded world view) – The deluded world view is the misunderstanding as to how this world really functions on account of one-sided perspectives, perverse viewpoints, pointless generalisations and ignorance.

* ''Avirati'' (non-restraint or a vowless life) – ''Avirati'' is the inability to refrain voluntarily from the evil actions, that harms oneself and others. The state of ''avirati'' can only be overcome by observing the minor vows of a layman.

* ''Pramāda'' (carelessness and laxity of conduct) – This third cause of bondage consists of absentmindedness, lack of enthusiasm towards acquiring merit and spiritual growth, and improper actions of mind, body and speech without any regard to oneself or others.

* '' '' (passions or negative emotions) – The four passions—anger, pride, deceit and greed—are the primary reason for the attachment of the karmas to the soul. They keep the soul immersed in the darkness of delusion leading to deluded conduct and unending cycles of reincarnations.

* ''Yoga'' (activities of mind, speech and body)

Each cause presupposes the existence of the next cause, but the next cause does not necessarily pre-suppose the existence of the previous cause. A soul is able to advance on the spiritual ladder called '' '', only when it is able to eliminate the above causes of bondage one by one.

Fruition

The consequences of karma are inevitable, though they may take some time to take effect. To explain this, a Jain monk, Ratnaprabhacharya says:

The latent karma becomes active and bears fruit when the supportive conditions arise. A great part of attracted karma bears its consequences with minor fleeting effects, as generally most of our activities are influenced by mild negative emotions. However, those actions that are influenced by intense negative emotions cause an equally strong karmic attachment which usually does not bear fruit immediately. It takes on an inactive state and waits for the supportive conditions—like proper time, place, and environment—to arise for it to manifest and produce effects. If the supportive conditions do not arise, the respective karmas will manifest at the end of maximum period for which it can remain bound to the soul. These supportive conditions for activation of latent karmas are determined by the nature of karmas, intensity of emotional engagement at the time of binding karmas and our actual relation to time, place, surroundings. There are certain laws of precedence among the karmas, according to which the fruition of some of the karmas may be deferred but not absolutely barred.

Jain texts distinguish between the effect of the fruition of ''karma'' on a right believer and a wrong believer:

The consequences of karma are inevitable, though they may take some time to take effect. To explain this, a Jain monk, Ratnaprabhacharya says:

The latent karma becomes active and bears fruit when the supportive conditions arise. A great part of attracted karma bears its consequences with minor fleeting effects, as generally most of our activities are influenced by mild negative emotions. However, those actions that are influenced by intense negative emotions cause an equally strong karmic attachment which usually does not bear fruit immediately. It takes on an inactive state and waits for the supportive conditions—like proper time, place, and environment—to arise for it to manifest and produce effects. If the supportive conditions do not arise, the respective karmas will manifest at the end of maximum period for which it can remain bound to the soul. These supportive conditions for activation of latent karmas are determined by the nature of karmas, intensity of emotional engagement at the time of binding karmas and our actual relation to time, place, surroundings. There are certain laws of precedence among the karmas, according to which the fruition of some of the karmas may be deferred but not absolutely barred.

Jain texts distinguish between the effect of the fruition of ''karma'' on a right believer and a wrong believer:

Modifications

Although the Jains believe the karmic consequences as inevitable, Jain texts also hold that a soul has energy to transform and modify the effects of karma. Karma undergoes following modifications: *''Udaya'' (maturity) – It is the fruition of karmas as per its nature in the due course. *''Udīraṇa'' (premature operation) – By this process, it is possible to make certain karmas operative before their predetermined time. *''Udvartanā'' (augmentation) – By this process, there is a subsequent increase in duration and intensity of the karmas due to additional negative emotions and feelings. *''Apavartanā'' (diminution) – In this case, there is subsequent decrease in duration and intensity of the karmas due to positive emotions and feelings. *' (transformation) – It is the mutation or conversion of one sub-type of karmas into another sub-type. However, this does not occur between different types. For example, ''papa'' (bad karma) can be converted into '' punya'' (good karma) as both sub-types belong to the same type of karma. *''Upaśamanā'' (state of subsidence) – During this state the operation of karma does not occur. The karma becomes operative only when the duration of subsidence ceases. *''Nidhatti'' (prevention) – In this state, premature operation and transformation is not possible but augmentation and diminution of karmas is possible. *''Nikācanā'' (invariance) – For some sub-types, no variations or modifications are possible—the consequences are the same as were established at the time of bonding. The Jain karmic theory, thus speaks of great powers of soul to manipulate the karmas by its actions.Release

Jain philosophy

Jain philosophy refers to the ancient Indian philosophical system found in Jainism. One of the main features of Jain philosophy is its dualistic metaphysics, which holds that there are two distinct categories of existence, the living, consciou ...

assert that emancipation is not possible as long as the soul is not released from bondage of karma. This is possible by ''samvara

''Samvara'' (''saṃvara'') is one of the '' tattva'' or the fundamental reality of the world as per the Jain philosophy. It means stoppage—the stoppage of the influx of the material karmas into the soul consciousness. The karmic process in ...

'' (stoppage of inflow of new karmas) and '' nirjarā'' (shedding of existing karmas through conscious efforts). ''Samvara'' is achieved through practice of:

*Three ''guptis'' or three controls of mind, speech and body,

*Five ''samitis'' or observing carefulness in movement, speaking, eating, placing objects and disposing refuse.

*Ten ''dharmas'' or observation of good acts like – forgiveness, humility, straightforwardness, contentment, truthfulness, self-control, penance, renunciation, non-attachment and continence.

*'' Anuprekshas'' or meditation on the truths of this universe.

*''Pariṣahajaya'', that is, a man on moral path must develop a perfectly patient and unperturbed attitude in the midst of trying and difficult circumstances.

*''Cāritra'', that is, endeavour to remain in steady spiritual practices.

''Nirjarā'' is possible through ''tapas

A tapa () is an appetizer or snack in Spanish cuisine. Tapas can be combined to make a full meal, and can be cold (such as mixed olives and cheese) or hot (such as ''chopitos'', which are battered, fried baby squid, or patatas bravas). In so ...

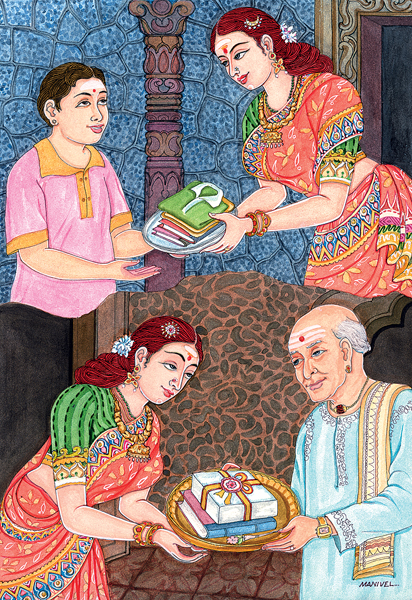

'', austerities and penances. ''Tapas'' can be either external or internal. Six forms of external ''tapas'' are—fasting, control of appetite, accepting food under certain conditions, renunciation of delicious food, sitting and sleeping in lonely place and renunciation of comforts. Six forms of internal ''tapas'' are—atonement, reverence, rendering of service to worthy ones, spiritual study, avoiding selfish feelings and meditation.

Rationale

Justice Tukol notes that the supreme importance of the doctrine of karma lies in providing a rational and satisfying explanation to the apparent unexplainable phenomenon of birth and death, of happiness and misery, of inequalities and of existence of different species of living beings. The '' Sūtrakṛtāṅga'', one of the oldest canons of Jainism, states: Jains thus cite inequalities, sufferings, and pain as evidence for the existence of karma. The theory of karma is able to explain day-to-day observable phenomena such as inequality between the rich and the poor, luck, differences in lifespan, and the ability to enjoy life despite being immoral. According to Jains, such inequalities and oddities that exist even from the time of birth can be attributed to the deeds of the past lives and thus provide evidence to existence of karmas:Criticisms

The Jain theory of karma has been challenged from an early time by theVedanta

''Vedanta'' (; sa, वेदान्त, ), also ''Uttara Mīmāṃsā'', is one of the six (''āstika'') schools of Hindu philosophy. Literally meaning "end of the Vedas", Vedanta reflects ideas that emerged from, or were aligned with, ...

and branches of Hindu philosophy

Hindu philosophy encompasses the philosophies, world views and teachings of Hinduism that emerged in Ancient India which include six systems ('' shad-darśana'') – Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Mimamsa and Vedanta.Andrew Nicholson ( ...

.

In particular, Vedanta Hindus considered the Jain position on the supremacy and potency of karma, specifically its insistence on non-intervention by any Supreme Being in regard to the fate of souls, as ''nāstika'' or atheistic

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no d ...

.

For example, in a commentary to the Brahma Sutras

The ''Brahma Sūtras'' ( sa, ब्रह्मसूत्राणि) is a Sanskrit text, attributed to the sage bādarāyaṇa or sage Vyāsa, estimated to have been completed in its surviving form in approx. 400–450 CE,, Quote: "...we c ...

(III, 2, 38, and 41), Adi Sankara

Adi Shankara ("first Shankara," to distinguish him from other Shankaras)(8th cent. CE), also called Adi Shankaracharya ( sa, आदि शङ्कर, आदि शङ्कराचार्य, Ādi Śaṅkarācāryaḥ, lit=First Shank ...

, argues that the original karmic actions themselves cannot bring about the proper results at some future time; neither can super sensuous, non-intelligent qualities like '' adrsta''—an unseen force being the metaphysical link between work and its result—by themselves mediate the appropriate, justly deserved pleasure and pain. The fruits, according to him, then, must be administered through the action of a conscious agent, namely, a supreme being (Ishvara

''Ishvara'' () is a concept in Hinduism, with a wide range of meanings that depend on the era and the school of Hinduism. Monier Monier Williams, Sanskrit-English dictionarySearch for Izvara University of Cologne, Germany In ancient texts of ...

).For the Jain refutation of the theory of God as operator and dispenser of karma, see Jainism and non-creationism

According to Jain doctrine, the universe and its constituents—soul, matter, space, time, and principles of motion—have always existed. Jainism does not support belief in a creator deity. All the constituents and actions are governed by univ ...

.

Jainism's strong emphasis on the doctrine of karma and intense asceticism was also criticised by the Buddhists. Thus, the ''Saṃyutta Nikāya

The Saṃyukta Nikāya/Samyutta Nikaya (''Saṃyukta'' ''Nikāya/'' SN, "Connected Discourses" or "Kindred Sayings") is a Buddhist scripture, the third of the five nikayas, or collections, in the Sutta Pitaka, which is one of the "three basket ...

'' narrates the story of Asibandhakaputta, a headman who was originally a disciple of Māhavīra. He debates with the Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in L ...

, telling him that, according to Māhavīra (Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta), a man's fate or karma is decided by what he does habitually. The Buddha responds, considering this view to be inadequate, stating that even a habitual sinner spends more time "not doing the sin" and only some time actually "doing the sin."

In another Buddhist text ''Majjhima Nikāya

The Majjhima Nikāya (-nikāya; "Collection of Middle-length Discourses") is a Buddhist scripture, the second of the five nikayas, or collections, in the Sutta Pitaka, which is one of the "three baskets" that compose the Pali Tipitaka (lit ...

'', the Buddha criticizes Jain emphasis on the destruction of unobservable and unverifiable types of karma as a means to end suffering, rather than on eliminating evil mental states such as greed, hatred and delusion, which are observable and verifiable. In the Upālisutta dialogue of this ''Majjhima Nikāya'' text, Buddha contends with a Jain monk who asserts that bodily actions are the most criminal, in comparison to the actions of speech and mind. Buddha criticises this view, saying that the actions of ''mind'' are most criminal, and not the actions of speech or body. Buddha also criticises the Jain ascetic practice of various austerities, claiming that he, Buddha, is happier when ''not'' practising the austerities.In the 8th century Jain text

Jain literature (Sanskrit: जैन साहित्य) refers to the literature of the Jain religion. It is a vast and ancient literary tradition, which was initially transmitted orally. The oldest surviving material is contained in the ca ...

''Aṣṭakaprakaraṇam'' (11.1–8), Haribhadra

Aacharya Haribhadra Suri was a Svetambara mendicant Jain leader, philosopher , doxographer, and author. There are multiple contradictory dates assigned to his birth. According to tradition, he lived c. 459–529 CE. However, in 1919, a Jain m ...

refutes the Buddhist view that austerities and penances results in suffering and pain. According to him suffering is on account of past karmas and not due to penances. Even if penances result in some suffering and efforts, they should be undertaken as it is the only means of getting rid of the karma. He compares it to the efforts and pains undertaken by a businessman to earn profit, which makes him happy. In the same way the austerities and penances are blissful to an ascetic who desires emancipation. See Haribhadrasūri, Sinha, Ashok Kumar, & Jain, Sagarmal (2000) p. 47

While admitting the complexity and sophistication of the Jain doctrine, Padmanabh Jaini compares it with that of Hindu doctrine of rebirth and points out that the Jain seers are silent on the exact moment and mode of rebirth, that is, the re-entry of soul in womb after the death. The concept of ''nitya-nigoda'', which states that there are certain categories of souls who have always been ''nigodas'', is also criticized. According to Jainism, ''nigodas'' are lowest form of extremely microscopic beings having momentary life spans, living in colonies and pervading the entire universe. According to Jaini, the entire concept of ''nitya-nigoda'' undermines the concept of karma, as these beings clearly would not have had prior opportunity to perform any karmically meaningful actions.

Karma is also criticised on the grounds that it leads to the dampening of spirits with men suffering the ills of life because the course of one's life is determined by karma. It is often maintained that the impression of karma as the accumulation of a mountain of bad deeds looming over our heads without any recourse leads to fatalism. However, as Paul Dundas puts it, the Jain theory of karma does not imply lack of free will

Free will is the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, sin, and other judgements which apply only to ac ...

or operation of total deterministic

Determinism is a philosophical view, where all events are determined completely by previously existing causes. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and cons ...

control over destinies. Furthermore, the doctrine of karma does not promote fatalism amongst its believers on account of belief in personal responsibility of actions and that austerities could expatiate the evil karmas and it was possible to attain salvation by emulating the life of the Jinas.

See also

*Karma

Karma (; sa, कर्म}, ; pi, kamma, italic=yes) in Sanskrit means an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptively ...

*Karma in Buddhism

Karma (Sanskrit, also ''karman'', Pāli: ''kamma'') is a Sanskrit term that literally means "action" or "doing". In the Buddhist tradition, ''karma'' refers to action driven by intention (''cetanā'') which leads to future consequences. Those i ...

*Karma in Hinduism

Karma is a concept of Hinduism which describes a system in which beneficial effects are derived from past beneficial actions and harmful effects from past harmful actions, creating a system of actions and reactions throughout a soul's ( jivatma ...

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * ''Note: ISBN and page nos. refers to the UK:Routledge (2001) reprint. URL is the scan version of the original 1895 reprint.'' * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

*The Jaina Philosophy, Karma Theory

Surendranath Dasgupta, 1940 {{DEFAULTSORT:Karma In Jainism