Karleton Armstrong on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Sterling Hall bombing occurred on the

Sterling Hall is a centrally located building on the

Sterling Hall is a centrally located building on the

During the

During the

The bombers were Karleton "Karl" Armstrong, Dwight Armstrong, David Fine, and

The bombers were Karleton "Karl" Armstrong, Dwight Armstrong, David Fine, and

David Fine came to Madison as a freshman in 1969 at the age of 17. He wrote for the campus newspaper ''

David Fine came to Madison as a freshman in 1969 at the age of 17. He wrote for the campus newspaper ''

Robert Fassnacht was a 33-year-old postdoctoral researcher at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. On the night and early morning of August 23/24, 1970, he had gone to the lab to finish up work before leaving on a family vacation. He was involved in research in the field of

Robert Fassnacht was a 33-year-old postdoctoral researcher at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. On the night and early morning of August 23/24, 1970, he had gone to the lab to finish up work before leaving on a family vacation. He was involved in research in the field of

University of Wisconsin–Madison

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United Stat ...

campus on August 24, 1970, and was committed by four men as an action against the university's research connections with the U.S. military during the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

. It resulted in the death of a university physics researcher and injuries to three others.

Overview

Sterling Hall is a centrally located building on the

Sterling Hall is a centrally located building on the University of Wisconsin–Madison

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United Stat ...

campus. The bomb, set off at 3:42 am on August 24, 1970, was intended to destroy the Army Mathematics Research Center (AMRC) housed on the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th floors of the building. It caused massive destruction to other parts of the building and nearby buildings as well. It resulted in the death of the researcher Robert Fassnacht, injured three others and caused significant destruction to the physics department and its equipment. Neither Fassnacht nor the physics department itself was involved with or employed by the Army Mathematics Research Center.

The bombers used a Ford Econoline

The Ford E-Series (also known as the Ford Econoline or Ford Club Wagon) is a range of full-size vans manufactured and marketed by the Ford Motor Company. Introduced for model year 1961 as the replacement for the Ford F-Series panel van, the E-S ...

van stolen from a University of Wisconsin professor of Computer Sciences. It was filled with close to of ANFO (i.e., ammonium nitrate

Ammonium nitrate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a white crystalline salt consisting of ions of ammonium and nitrate. It is highly soluble in water and hygroscopic as a solid, although it does not form hydrates. It is ...

and fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil, marine fuel oil (MFO), b ...

). Pieces of the van were found on top of an eight-story building three blocks away and 26 nearby buildings were damaged; however, the targeted AMRC was scarcely damaged. Total damage to University of Wisconsin–Madison property was over $2.1 million ($ in ) as a result of the bombing.

Army Mathematics Research Center

During the

During the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, the 2nd, 3rd and 4th floors of the southern (east-west) wing of Sterling Hall housed the Army Mathematics Research Center (AMRC). This was an Army-funded think tank, directed by J. Barkley Rosser, Sr.

The staff at the center, at the time of the bombing, consisted of about 45 mathematicians, about 30 of them full-time. Rosser was well known for his research in pure mathematics

Pure mathematics is the study of mathematical concepts independently of any application outside mathematics. These concepts may originate in real-world concerns, and the results obtained may later turn out to be useful for practical applications, ...

, logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from prem ...

(Rosser's trick

In mathematical logic, Rosser's trick is a method for proving Gödel's incompleteness theorems without the assumption that the theory being considered is ω-consistent (Smorynski 1977, p. 840; Mendelson 1977, p. 160). This method w ...

, the Kleene–Rosser paradox, and the Church-Rosser theorem) and in number theory

Number theory (or arithmetic or higher arithmetic in older usage) is a branch of pure mathematics devoted primarily to the study of the integers and integer-valued functions. German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) said, "Ma ...

(Rosser sieve Rosser may refer to:

__NOTOC__ People

* Rosser (surname)

* Rosser Evans (1867–?), Welsh rugby union player

* Rosser Reeves (1910–1984), American advertising executive and pioneer of television advertising

Places

* Rural Municipality of Rosser ...

). Rosser had been the head of the U.S. ballistics program during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and also had contributed to research on several missiles used by the U.S. military.

The money to build a home for AMRC came from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) in 1955. Their money built a 6-floor addition to Sterling Hall. In the contract to work at the facility, it was required that mathematicians spend at least half their time on U.S. Army research.

Rosser publicly minimized any military role of the center and implied that AMRC pursued mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, including both pure and applied mathematics. The University of Wisconsin student newspaper, ''The Daily Cardinal

''The Daily Cardinal'' is a student newspaper that serves the University of Wisconsin–Madison community. One of the oldest student newspapers in the country, it began publishing on Monday, April 4, 1892. The newspaper is financially and editoria ...

'', obtained and published quarterly reports that AMRC submitted to the Army. ''The Cardinal'' published a series of investigative articles making a convincing case that AMRC was pursuing research that was directly pursuant to specific U.S. Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense (DoD, USDOD or DOD) is an executive branch department of the federal government charged with coordinating and supervising all agencies and functions of the government directly related to national secur ...

requests, and relevant to counterinsurgency operations in Vietnam. AMRC became a magnet for demonstrations, in which protesters chanted "U.S. out of Vietnam! Smash Army Math!"

The Army Mathematics Research Center was phased out by the Department of Defense at the end of the 1970 fiscal year.

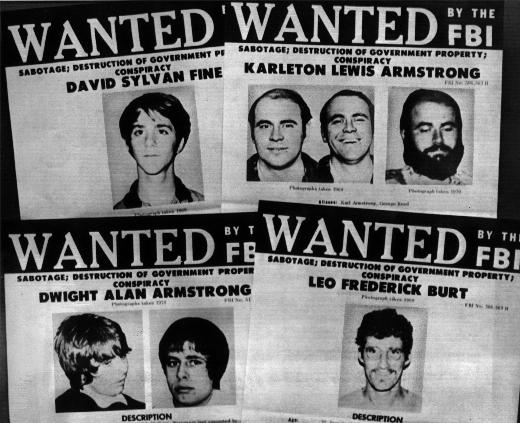

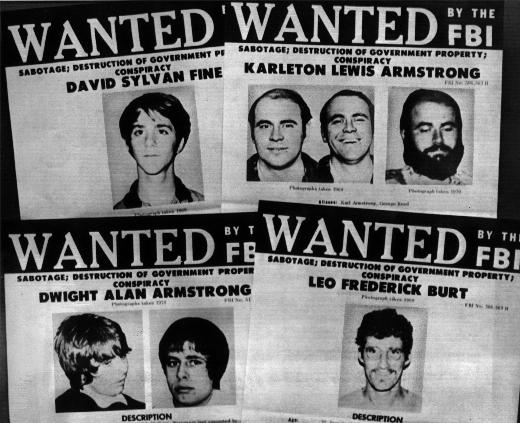

The bombers

The bombers were Karleton "Karl" Armstrong, Dwight Armstrong, David Fine, and

The bombers were Karleton "Karl" Armstrong, Dwight Armstrong, David Fine, and Leo Burt

Leo Frederick Burt (born April 18, 1948) is an American man indicted in connection with the August 24, 1970 Sterling Hall bombing at the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus, a protest against the Vietnam War. The bombing killed physics resea ...

. They called themselves the "New Year's Gang", a name which was derived from an exploit on New Year's Eve 1969. In that earlier attack, Dwight and Karl, with Karl's girlfriend, Lynn Schultz (who drove the getaway car), stole a small plane from Morey Field in Middleton. Dwight and Karl dropped homemade explosives on the Badger Army Ammunition Plant

The Badger Army Ammunition Plant (BAAP or Badger) or Badger Ordnance Works (B.O.W.) is an excess, non- BRAC, United States Army facility located near Sauk City, Wisconsin. It manufactured nitrocellulose-based propellants during World War II, the K ...

, but the explosives failed to detonate. They successfully landed the plane at another airport and escaped.

Before the Sterling Hall bombing, Karl had committed several other acts with anti-war motivations, including setting fire to a ROTC

The Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC ( or )) is a group of college- and university-based officer-training programs for training commissioned officers of the United States Armed Forces.

Overview

While ROTC graduate officers serve in al ...

installation at the University of Wisconsin Armory and Gymnasium

The University of Wisconsin Armory and Gymnasium, also called "the Red Gym", is a building on the campus of University of Wisconsin–Madison. It was originally used as a combination gymnasium and armory beginning in 1894. Designed in the Romanesqu ...

(the Red Gym) and one meant for the state Selective Service

The Selective Service System (SSS) is an independent agency of the United States government that maintains information on U.S. citizens and other U.S. residents potentially subject to military conscription (i.e., the draft) and carries out contin ...

headquarters which instead held the University of Wisconsin Primate Research Center. Karl also attempted to plant explosives at a Prairie du Sac

Prairie du Sac is a village in Sauk County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 4,420 at the 2020 census. The village is surrounded by the Town of Prairie du Sac, the Wisconsin River, and the village of Sauk City; together, Prairie du ...

electrical substation that supplied power to the ammunition plant, but was frightened off by the night watchman.

Karleton “Blackman" Armstrong

Karl was oldest of the bombers, and had been admitted into the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1964. He was changed by theVietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

and quit school a year later. He took on odd jobs for the next few years, and was re-accepted into the university in the fall of 1967. He was witness to violence between police and protesters on October 18, 1967, when the Dow Chemical Company

The Dow Chemical Company, officially Dow Inc., is an American multinational chemical corporation headquartered in Midland, Michigan, United States. The company is among the three largest chemical producers in the world.

Dow manufactures plastics ...

arranged for job interviews with students on campus and many students protested and blocked potential interviewers from the building where the interviews were being held.

After the bombing, he went into hiding until he was caught on February 16, 1972, in Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

. He was sentenced to 23 years in prison, but served only seven years. After his release, Armstrong returned to Madison, where he operated a juice cart called Loose Juice on the library mall. In the early 2000s, he also owned a deli called Radical Rye on State Street near the UW–Madison campus until it was displaced by the development of the Overture Center

Overture Center for the Arts is a performing arts center and art gallery in Madison, Wisconsin, United States. The center opened on September 19, 2004, replacing the former Civic Center. In addition to several theaters, the center also houses the ...

.

Dwight Armstrong

The younger brother of Karl, Dwight was 19 at the time of the bombing. After the bombing, he lived in a commune in Toronto, where he used the name "Virgo". After a few months, he left the commune, went toVancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the city, up from 631,486 in 2016. ...

and then re-appeared in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

, where he connected with the Symbionese Liberation Army

The United Federated Forces of the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) was a small, American far-left organization active between 1973 and 1975; it claimed to be a vanguard movement. The FBI and American law enforcement considered the SLA to be the ...

(SLA), which was holding Patty Hearst at the time. It is believed he was not active in the SLA. He returned to Toronto and was arrested there on April 10, 1977. He pleaded guilty to the bombing, was sentenced to seven years in prison, and served three years before being released.

In 1987, he was arrested and then later convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison for conspiring to distribute amphetamines in Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

. After being released from prison, he returned to Madison and worked for Union Cab until January 2001 when he purchased the Radical Rye Deli with his brother Karl.

Dwight Armstrong died from lung cancer on June 20, 2010, at age 58.

David Fine

The Daily Cardinal

''The Daily Cardinal'' is a student newspaper that serves the University of Wisconsin–Madison community. One of the oldest student newspapers in the country, it began publishing on Monday, April 4, 1892. The newspaper is financially and editoria ...

'', and associated with the other writers, including Leo Burt. He met Karl Armstrong for the first time in the summer of 1970.

Being 18 years old at the time of the bombing, he was the youngest of the four bombers. He was captured in San Rafael, California

San Rafael ( ; Spanish for " St. Raphael", ) is a city and the county seat of Marin County, California, United States. The city is located in the North Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's popula ...

, on January 7, 1976. He was sentenced to seven years in federal prison for his part in the bombing, and he served three years.

In 1987, after passing the Oregon bar exam

A bar examination is an examination administered by the bar association of a jurisdiction that a lawyer must pass in order to be admitted to the bar of that jurisdiction.

Australia

Administering bar exams is the responsibility of the bar associat ...

, Fine was denied admission to the bar on the grounds that he "had failed to show good moral character". Fine appealed the decision to the Supreme Court of Oregon which upheld the decision.

Leo Burt

Leo Burt was 22 years old, and worked for the campus newspaper, ''The Daily Cardinal'', with David Fine. Burt came to Wisconsin following his interest inrowing

Rowing is the act of propelling a human-powered watercraft using the sweeping motions of oars to displace water and generate reactional propulsion. Rowing is functionally similar to paddling, but rowing requires oars to be mechanically ...

, and he joined the crew team. He introduced Fine and Karl Armstrong to each other in July 1970.

After the bombing, Burt fled to Canada with Fine, and as of May 2020, still has not been seen. In 2010, there had been new leads on his possible whereabouts, which came up inconclusive.

Victims

Robert Fassnacht was a 33-year-old postdoctoral researcher at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. On the night and early morning of August 23/24, 1970, he had gone to the lab to finish up work before leaving on a family vacation. He was involved in research in the field of

Robert Fassnacht was a 33-year-old postdoctoral researcher at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. On the night and early morning of August 23/24, 1970, he had gone to the lab to finish up work before leaving on a family vacation. He was involved in research in the field of superconductivity

Superconductivity is a set of physical properties observed in certain materials where electrical resistance vanishes and magnetic flux fields are expelled from the material. Any material exhibiting these properties is a superconductor. Unlike ...

. At the time of the explosion, Fassnacht was in his lab located in the basement level of Sterling Hall. He was monitoring an experiment when the explosion occurred. Rescuers found him face down in about a foot of water. He was survived by his wife, Stephanie, and their three children, a three-year-old son, Christopher, and twin one-year-old daughters, Heidi and Karin.

Injured in the bombing were Paul Quin, David Schuster, and Norbert Sutler. Schuster, a South African graduate student, who became deaf in one ear and with only partial hearing in the other ear, was the most seriously injured of the three, suffering a broken shoulder, fractured ribs and a broken eardrum; he was buried in the rubble for three hours before being rescued by firefighters. Quin, a postdoctoral physics researcher, and Sutler, a university security officer, suffered cuts from shattered glass and bruises. Quin, who became a physics professor at U. W. Madison, always refused to discuss the bombing in public.

See also

* Lists of protests against the Vietnam War#1970 *List of homicides in Wisconsin

This is a list of homicides in Wisconsin. This list includes notable homicides committed in the U.S. state of Wisconsin that have a Wikipedia article on the killing, the killer, or the victim. It is divided into three subject areas as follows ...

* ''The War at Home'' (1979 film)

* ''Running on Empty'' (1988 film)

References

Further reading

* * *External links

* * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Sterling Hall Bombing School bombings in the United States 1970 murders in the United States Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War Riots and civil disorder in Wisconsin University of Wisconsin–Madison Murder in Wisconsin Car and truck bombings in the United States 1970 in Wisconsin School killings in the United States Attacks on universities and colleges in the United States August 1970 events in the United States Terrorist incidents in the United States in 1970 History of Madison, Wisconsin