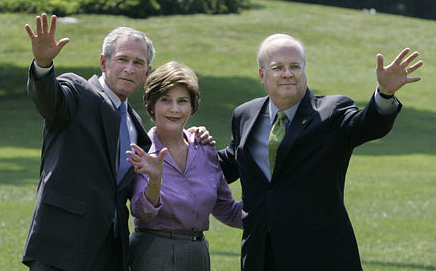

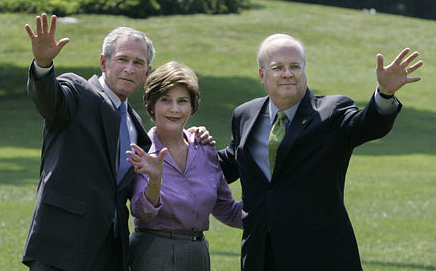

Karl Christian Rove (born December 25, 1950) is an American

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

political consultant

Political consulting is a form of consulting that consists primarily of advising and assisting political campaigns. Although the most important role of political consultants is arguably the development and production of mass media (largely tel ...

, policy advisor, and lobbyist. He was

Senior Advisor

In some countries, a senior advisor (also spelt senior adviser, especially in the UK) is an appointed position by the Head of State to advise on the highest levels of national and government policy. Sometimes a junior position to this is called a N ...

and

Deputy Chief of Staff during the

George W. Bush administration until his resignation on August 31, 2007. He has also headed the Office of Political Affairs, the

Office of Public Liaison

The White House Office of Public Engagement is a unit of the White House Office within the Executive Office of the President of the United States. Under the administration of President Barack Obama, it was called the White House Office of Publ ...

, and the

White House Office of Strategic Initiatives The White House Office of Strategic Initiatives (OSI) was a staff unit within the Executive Office of the President of the United States during the administration of U.S. President George W. Bush. Karl Rove was the first head of the office as Seni ...

.

Prior to his White House appointments, he is credited with the 1994 and 1998

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

gubernatorial victories of

George W. Bush, as well as Bush's

2000

File:2000 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: Protests against Bush v. Gore after the 2000 United States presidential election; Heads of state meet for the Millennium Summit; The International Space Station in its infant form as seen from S ...

and 2004 successful presidential campaigns. In his 2004 victory speech, Bush referred to Rove as "the Architect". Rove has also been credited for the successful campaigns of

John Ashcroft

John David Ashcroft (born May 9, 1942) is an American lawyer, lobbyist and former politician who served as the 79th U.S. Attorney General in the George W. Bush administration from 2001 to 2005. A former U.S. Senator from Missouri and the 50th ...

(1994 U.S. Senate election),

Bill Clements

William Perry Clements Jr. (April 13, 1917 – May 29, 2011) was an American businessman and Republican Party politician who served two non-consecutive terms as the governor of Texas between 1979 and 1991. His terms bookended the sole t ...

(1986 Texas gubernatorial election), Senator

John Cornyn

John Cornyn III ( ; born February 2, 1952) is an American politician and attorney serving as the senior United States senator from Texas, a seat he has held since 2002. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the Senate majority whip for ...

(2002 U.S. Senate election),

Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Rick Perry

James Richard Perry (born March 4, 1950) is an American politician who served as the 14th United States secretary of energy from 2017 to 2019 and as the 47th governor of Texas from 2000 to 2015. Perry also ran unsuccessfully for the Republic ...

(1990 Texas Agriculture Commission election), and

Phil Gramm

William Philip Gramm (born July 8, 1942) is an American economist and politician who represented Texas in both chambers of Congress. Though he began his political career as a Democrat, Gramm switched to the Republican Party in 1983. Gramm was a ...

(1982

U.S. House and 1984 U.S. Senate elections). Since leaving the White House, Rove has worked as a political analyst and contributor for

Fox News

The Fox News Channel, abbreviated FNC, commonly known as Fox News, and stylized in all caps, is an American multinational conservative cable news television channel based in New York City. It is owned by Fox News Media, which itself is o ...

, ''

Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis (businessman), Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print m ...

'', and ''

The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' is an American business-focused, international daily newspaper based in New York City, with international editions also available in Chinese and Japanese. The ''Journal'', along with its Asian editions, is published ...

''.

Early years

Family, upbringing, and early education

Rove was born on Christmas Day in

Denver, Colorado

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

, the second of five children, and was raised in

Sparks, Nevada

Sparks is a city in Washoe County, Nevada, United States. It was founded in 1904, incorporated on March 15, 1905, and is located just east of Reno. The 2020 U.S. Census counted 108,445 residents in the city. It is the fifth most populous city i ...

. His parents separated when he was 19 years old and the man whom Rove knew as his father was a

geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althou ...

.

In 1965, his family moved to

Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the capital and most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in Utah. With a population of 200,133 in 2020, th ...

, where Rove entered high school, becoming a skilled debater. Encouraged by a teacher to run for class senate, Rove won the election. As part of his campaign strategy he rode in the back of a convertible inside the school gymnasium sitting between two attractive girls before his election speech. While at

Olympus High School

Olympus High School is a public high school in the Granite School District in Holladay, Utah, a suburb of Salt Lake City.

Description

The school opened on September 1, 1953, with an original enrollment of 1028 students. In the fall of 1960, t ...

, he was elected student council president his junior and senior years. Rove was also a

Teenage Republican and served as Chairman of the Utah Federation of Teenage Republicans. During this time, his father got a job in Los Angeles and visited the family during holidays.

Rove's mother suffered from depression and had contemplated suicide more than once in her life.

Rove stated that although he loved his mother, she was seriously flawed, undependable and, at times, unstable.

In December 1969, after a heated fight with his wife, the man Rove had known as his father left the family and

divorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving th ...

d Rove's mother soon afterwards. Rove's mother moved back to Nevada, and his siblings briefly lived with relatives after the divorce.

Rove learned from his aunt and uncle that the man who had raised him was not his biological father; both he and his older brother Eric were the children of another man. Rove has expressed great love and admiration for his adoptive father and for "how selfless" his love had been.

['']The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

'' profile

The Controller: Karl Rove is working to get George Bush reelected, but he has bigger plans.

by Nicholas Lemann "Profiles", ''The New Yorker.'', May 12, 2003

Rove's father and mother expressed deep regret over the failure of the marriage and briefly tried dating each other after the divorce, but they refused to explain the breakup of the marriage, only stating that they still "loved each other dearly."

Rove was unable to convince his parents to get back together, as they were adamant about the divorce, a situation which Rove still does not understand.

Rove's relationship with his adoptive father was briefly strained for a few months following the divorce, but they maintained a very close relationship for the rest of his life.

Rove had only infrequent contact with his mother in the 1970s. She frequently withheld child support checks and spent them for herself. She and her second husband lost most of their money due to poor financial decisions on her part and his gambling and overspending.

On September 11, 1981, Rove's mother died by

suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and ...

in

Reno, Nevada

Reno ( ) is a city in the northwest section of the U.S. state of Nevada, along the Nevada-California border, about north from Lake Tahoe, known as "The Biggest Little City in the World". Known for its casino and tourism industry, Reno is th ...

, shortly after she decided to divorce her third and final husband, to whom she had been unhappily married for only three months.

['' CNN'' Transcripts]

The Situation Room: Reversal on 9/11 Trials; Karl Rove's Book; Shooting outside the Pentagon; Violent Incidents; Millennial Second Thoughts; Mitt Romney Interview.

''CNN: The Situation Room'', Aired March 5, 2010.

Entry into politics

Rove began his involvement in American politics in 1968. In a 2002 ''

Deseret News

The ''Deseret News'' () is the oldest continuously operating publication in the American west. Its multi-platform products feature journalism and commentary across the fields of politics, culture, family life, faith, sports, and entertainment. Th ...

'' interview, Rove explained, "I was the Olympus High chairman for (former U.S. Sen.)

Wallace F. Bennett

Wallace Foster Bennett (November 13, 1898 – December 19, 1993) was an American businessman and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as a US Senator from Utah from 1951 to 1974. He was the father of Bob Bennett, who late ...

's re-election campaign, where he was opposed by the dynamic, young, aggressive political science professor at the

University of Utah

The University of Utah (U of U, UofU, or simply The U) is a public research university in Salt Lake City, Utah. It is the flagship institution of the Utah System of Higher Education. The university was established in 1850 as the University of De ...

, J.D. Williams."

Bennett was reelected to a third six-year term in November 1968. Through Rove's campaign involvement, Bennett's son,

Robert "Bob" Foster Bennett—a future United States Senator from

Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

—would become a friend. Williams would later become a mentor to Rove.

College and the Dixon campaign sabotage incident

In the fall of 1969, Rove entered the

University of Utah

The University of Utah (U of U, UofU, or simply The U) is a public research university in Salt Lake City, Utah. It is the flagship institution of the Utah System of Higher Education. The university was established in 1850 as the University of De ...

, on a $1,000 scholarship, as a

political science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and ...

major and joined the

Pi Kappa Alpha

Pi Kappa Alpha (), commonly known as PIKE, is a college fraternity founded at the University of Virginia in 1868. The fraternity has over 225 chapters and colonies across the United States and abroad with over 15,500 undergraduate members over 3 ...

fraternity. Through the University's

Hinckley Institute of Politics

The Hinckley Institute of Politics is a nonpartisan institute located on the University of Utah campus in Salt Lake City, Utah. Its purpose is "to engage students in transformative experiences and provide political thought leadership" through inv ...

, he got an

intern

An internship is a period of work experience offered by an organization for a limited period of time. Once confined to medical graduates, internship is used practice for a wide range of placements in businesses, non-profit organizations and gove ...

ship with the

Utah Republican Party

The Utah Republican Party is the affiliate of the Republican Party in the U.S. state of Utah. It is currently the dominant party in the state, controlling all four of Utah's U.S. House seats, both U.S. Senate seats, the governorship, and has s ...

. That position, and contacts from the 1968 Bennett campaign, helped him secure a job in 1970 on

Ralph Tyler Smith's unsuccessful re-election campaign for

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

from

Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

against

Democrat Adlai E. Stevenson III.

In the fall of 1970, Rove used a false identity to enter the campaign office of Democrat

Alan J. Dixon

Alan John Dixon (July 7, 1927 – July 6, 2014) was an American politician and member of the Democratic Party who served in the Illinois General Assembly from 1951 to 1971, as the Illinois Treasurer from 1971 to 1977, as the Illinois Secretary o ...

, who was running for

Treasurer of Illinois

The Treasurer of Illinois is an elected official of the U.S. state of Illinois. The office was created by the Constitution of Illinois.

Current Occupant

The current Treasurer of Illinois is Democrat Mike Frerichs. He was first elected to hea ...

. He stole 1000 sheets of paper with campaign letterhead, printed fake campaign rally fliers promising "free beer, free food, girls and a good time for nothing", and distributed them at rock concerts and

homeless

Homelessness or houselessness – also known as a state of being unhoused or unsheltered – is the condition of lacking stable, safe, and adequate housing. People can be categorized as homeless if they are:

* living on the streets, also kn ...

shelters, with the effect of disrupting Dixon's rally. (Dixon eventually won the election.) Rove's role would not become publicly known until August 1973 when Rove told ''The Dallas Morning News''. In 1999 he said, "It was a youthful prank at the age of 19 and I regret it."

In his memoir, Rove wrote that when he was later nominated to the Board for International Broadcasting by President George H.W. Bush, Senator Dixon did not kill his nomination. In Rove's account, "Dixon displayed more grace than I had shown and kindly excused this youthful prank."

College Republicans, Watergate, and the Bushes

In June 1971, after the end of the semester, Rove

dropped out of the University of Utah to take a paid position as the Executive Director of the

College Republican National Committee

The College Republican National Committee (CRNC) is a national organization for College Republicans — college and university students who support the Republican Party of the United States. The organization is known as an active recruiting tool f ...

. Joe Abate, who was National Chairman of the College Republicans at the time, became his mentor.

Rove then enrolled at the

University of Maryland in College Park in the Fall of 1971, but withdrew from classes during the first half of the semester.

In July 1999 he told ''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'' that he did not have a degree because "I lack at this point one math class, which I can take by exam, and my foreign language requirement."

Rove traveled extensively, participating as an instructor at weekend seminars for campus

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

s across the country. He was an active participant in

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

's

1972 Presidential campaign. A CBS report on the organization of the Nixon campaign from June 1972 includes an interview with a young Rove working for the College Republican National Committee.

Rove held the position of executive director of the College Republicans until early 1973. He left the job to spend five months, without pay, campaigning full-time for the position of National Chairman during the time he attended

George Mason University

George Mason University (George Mason, Mason, or GMU) is a public research university in Fairfax County, Virginia with an independent City of Fairfax, Virginia postal address in the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area. The university was origin ...

.

Lee Atwater

Harvey LeRoy "Lee" Atwater (February 27, 1951 – March 29, 1991) was an American political consultant and strategist for the Republican Party. He was an adviser to US presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush and chairman of the Repub ...

, the group's Southern regional coordinator, who was two months younger than Rove, assisted with Rove's campaign. His campaign was managed by Daniel Mintz, of the Maryland College Republicans. Karl spent the spring of 1973 crisscrossing the country in a

Ford Pinto

The Ford Pinto is a subcompact car that was manufactured and marketed by Ford Motor Company in North America from 1971 until 1980 model years. The Pinto was the first subcompact vehicle produced by Ford in North America.

The Pinto was marketed ...

, lining up the support of Republican state chairs.

The College Republicans summer 1973 convention at the

Lake of the Ozarks

Lake of the Ozarks is a reservoir created by impounding the Osage River in the northern part of the Ozarks in central Missouri. Parts of three smaller tributaries to the Osage are included in the impoundment: the Niangua River, Grandglaize Cr ...

resort in

Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

was quite contentious. Rove's opponent was Robert Edgeworth of

Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and t ...

. The other major candidate,

Terry Dolan of

California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, dropped out, supporting Edgeworth. A number of states had sent two competing delegates, because Rove and his supporters had made credential challenges at state and regional conventions. For example, after the Midwest regional convention, Rove forces had produced a version of the Midwestern College Republicans constitution which differed significantly from the constitution that the Edgeworth forces were using, in order to justify the unseating of the Edgeworth delegates on procedural grounds,

including delegations, such as

Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

and Missouri, which had been certified earlier by Rove himself. In the end, there were two votes, conducted by two convention chairs, and two winners—Rove and Edgeworth, each of whom delivered an acceptance speech. After the convention, both Edgeworth and Rove appealed to

Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is a U.S. political committee that assists the Republican Party of the United States. It is responsible for developing and promoting the Republican brand and political platform, as well as assisting in ...

Chairman

George H. W. Bush, each contending that he was the new College Republican chairman.

While resolution was pending, Dolan went (anonymously) to ''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'' with recordings of several training seminars for young Republicans where a co-presenter of Rove's, Bernie Robinson, cautioned against doing the same thing he had done: rooting through opponents' garbage cans. The tape with this story on it, as well as Rove's admonition not to copy similar tricks as Rove's against Dixon, was secretly recorded and edited by Rich Evans, who had hoped to receive an appointment from Rove's competitor in the CRNC chairmanship race. On August 10, 1973, in the midst of the

Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's contin ...

, the ''Post'' broke the story in an article titled "GOP Party Probes Official as Teacher of Tricks".

[

In response, then RNC Chairman George H.W. Bush, had an FBI agent question Rove. As part of the investigation, Atwater signed an ]affidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or '' deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by law. Such a stateme ...

, dated August 13, 1973, stating that he had heard a "20 minute anecdote similar to the one described in ''The Washington Post''" in July 1972, but that "it was a funny story during a coffee break". Former Nixon White House

Richard Nixon's tenure as the 37th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1969, and ended when he resigned on August 9, 1974, in the face of almost certain impeachment because of the Watergate Scan ...

Counsel John Dean

John Wesley Dean III (born October 14, 1938) is an American former attorney who served as White House Counsel for U.S. President Richard Nixon from July 1970 until April 1973. Dean is known for his role in the cover-up of the Watergate scandal ...

, has been quoted as saying "based on my review of the files, it appears the Watergate prosecutors were interested in Rove's activities in 1972, but because they had bigger fish to fry they did not aggressively investigate him."

On September 6, 1973, three weeks after announcing his intent to investigate the allegations against Rove, George H. W. Bush chose him to be chairman of the College Republicans. Bush then wrote Edgeworth a letter saying that he had concluded that Rove had fairly won the vote at the convention. Edgeworth wrote back, asking about the basis of that conclusion. Not long after that, Edgeworth stated "Bush sent me back the angriest letter I have ever received in my life. I had leaked to ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'', and now I was out of the Party forever."

As National Chairman, Rove introduced Bush to Atwater, who had taken Rove's job as the College Republican's executive director, and who would become Bush's main campaign strategist in future years. Bush hired Rove as a Special Assistant in the Republican National Committee, a job Rove left in 1974 to become Executive Assistant to the co-chair of the RNC, Richard D. Obenshain.

As Special Assistant, Rove performed small personal tasks for Bush. In November 1973, he asked Rove to take a set of car keys to his son George W. Bush, who was visiting home during a break from Harvard Business School

Harvard Business School (HBS) is the graduate business school of Harvard University, a private research university in Boston, Massachusetts. It is consistently ranked among the top business schools in the world and offers a large full-time MBA ...

. It was the first time the two met. "Huge amounts of charisma, swagger, cowboy boots, flight jacket, wonderful smile, just charisma – you know, wow", Rove recalled years later.

Virginia

In 1976, Rove left D.C. to work in Virginian politics. Initially, Rove served as the Finance Director for the Republican Party of Virginia. Rove describes this as the role in which he discovered his love for direct mail campaigns.

The Texas years and notable political campaigns

1977–1991

Rove's initial job in Texas was in 1977 as a legislative aide for Fred Agnich

Frederick Joseph Agnich (July 19, 1913 – October 28, 2004) was a Minnesota-born geophysicist who served from 1971 to 1987 as a Republican member of the Texas House of Representatives. From 1972 to 1976, he was the Texas Republican Nationa ...

, a Texas Republican state representative

A state legislature is a legislative branch or body of a political subdivision in a federal system.

Two federations literally use the term "state legislature":

* The legislative branches of each of the fifty state governments of the United S ...

from Dallas

Dallas () is the third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 million people. It is the largest city in and seat of Dallas County ...

. Later that same year, Rove got a job as executive director of the Fund for Limited Government, a political action committee (PAC) in Houston headed by James A. Baker, III

James Addison Baker III (born April 28, 1930) is an American attorney, diplomat and statesman. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 10th White House Chief of Staff and 67th United States Secretary of the Treasury under President ...

, a Houston lawyer (later President George H. W. Bush's Secretary of State). The PAC eventually became the genesis of the Bush-for-President campaign of 1979–1980.

His work for Bill Clements

William Perry Clements Jr. (April 13, 1917 – May 29, 2011) was an American businessman and Republican Party politician who served two non-consecutive terms as the governor of Texas between 1979 and 1991. His terms bookended the sole t ...

during the Texas gubernatorial

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of politica ...

election of 1978 helped Clements become the first Republican Governor of Texas in over 100 years. Clements was elected to a four-year term, succeeding Democrat Dolph Briscoe

Dolph Briscoe Jr. (April 23, 1923 – June 27, 2010) was an American rancher and businessman from Uvalde, Texas, who was the 41st governor of Texas between 1973 and 1979. He was a member of the Democratic Party.

Because of his re-election foll ...

. Rove was deputy director of the Governor William P. Clements Junior Committee in 1979 and 1980, and deputy executive assistant to the governor of Texas (roughly, Deputy Chief of Staff) in 1980 and 1981.

In 1981, Rove founded a direct mail

Advertising mail, also known as direct mail (by its senders), junk mail (by its recipients), mailshot or admail (North America), letterbox drop or letterboxing (Australia) is the delivery of advertising material to recipients of postal mail. The d ...

consulting firm, Karl Rove & Co., in Austin. The firm's first clients included Texas Governor Bill Clements and Democratic congressman Phil Gramm

William Philip Gramm (born July 8, 1942) is an American economist and politician who represented Texas in both chambers of Congress. Though he began his political career as a Democrat, Gramm switched to the Republican Party in 1983. Gramm was a ...

, who later became a Republican congressman and United States Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

. Rove operated his consulting business until 1999, when he sold the firm to take a full-time position in George W. Bush's presidential campaign.

Between 1981 and 1999, Rove worked on hundreds of races. Most were in a supporting role, doing direct mail fundraising. A November 2004 ''Atlantic Monthly

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher. It features articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 in Boston, ...

'' article estimated that he was the primary strategist for 41 statewide, congressional, and national races, and Rove's candidates won 34 races.Philip Morris Phil(l)ip or Phil Morris may refer to:

Companies

*Altria, a conglomerate company previously known as Philip Morris Companies Inc., named after the tobacconist

**Philip Morris USA, a tobacco company wholly owned by Altria Group

** Philip Morris Inte ...

, and ultimately earned $3,000 a month via a consulting contract. In a deposition

Deposition may refer to:

* Deposition (law), taking testimony outside of court

* Deposition (politics), the removal of a person of authority from political power

* Deposition (university), a widespread initiation ritual for new students practiced f ...

, Rove testified that he severed the tie in 1996 because he felt awkward "about balancing that responsibility with his role as Bush's top political advisor" while Bush was governor of Texas and Texas was suing the tobacco industry

The tobacco industry comprises those persons and companies who are engaged in the growth, preparation for sale, shipment, advertisement, and distribution of tobacco and tobacco-related products. It is a global industry; tobacco can grow in any ...

.

1978 George W. Bush congressional campaign

Rove advised the younger Bush during his unsuccessful Texas congressional campaign in 1978.

1980 George H. W. Bush presidential campaign

In 1977, Rove was the first person hired by George H. W. Bush for his unsuccessful 1980 presidential campaign, which ended with Bush as the vice-presidential nominee.

1982 William Clements, Jr. gubernatorial campaign

In 1982, Rove returned to assisting Governor Bill Clements in his run for reelection, but was defeated by Democrat Mark White.

1982 Phil Gramm congressional campaign

In 1982, Phil Gramm

William Philip Gramm (born July 8, 1942) is an American economist and politician who represented Texas in both chambers of Congress. Though he began his political career as a Democrat, Gramm switched to the Republican Party in 1983. Gramm was a ...

was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a conservative Texas Democrat.

1984 Phil Gramm senatorial campaign

In 1984, Rove helped Gramm, who had become a Republican in 1983, defeat Republican Ron Paul

Ronald Ernest Paul (born August 20, 1935) is an American author, activist, physician and retired politician who served as the U.S. representative for Texas's 22nd congressional district from 1976 to 1977 and again from 1979 to 1985, as we ...

in the primary and Democrat Lloyd Doggett

Lloyd Alton Doggett II (born October 6, 1946) is an American attorney and politician who is a U.S. representative from Texas. A member of the Democratic Party, he has represented a district based in Austin since 1995, currently numbered as Tex ...

in the race for U.S. Senate.

1984 Ronald Reagan presidential campaign

Rove handled direct-mail for the Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

-Bush campaign.

1986 William Clements, Jr. gubernatorial campaign

In 1986, Rove helped Clements become governor a second time. In a strategy memo Rove wrote for his client prior to the race, now among Clements' papers in the Texas A&M University

Texas A&M University (Texas A&M, A&M, or TAMU) is a public university, public, Land-grant university, land-grant, research university in College Station, Texas. It was founded in 1876 and became the flagship institution of the Texas A&M Unive ...

library, Rove quoted Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

: "The whole art of war consists in a well-reasoned and extremely circumspect defensive, followed by rapid and audacious attack."

In 1986, just before a crucial debate in the campaign, Rove claimed that his office had been bugged by Democrats. The police and FBI investigated and discovered that the bug's battery was so small that it needed to be changed every few hours, and the investigation was dropped. Critics, including other Republican operatives, suspected Rove had bugged his own office to garner sympathy votes in the close governor's race.

1988 Texas Supreme Court races

In 1988, Rove helped Thomas R. Phillips

Thomas Royal Phillips (born October 23, 1949) is an attorney with the Baker Botts firm in Austin, Texas, who was from 1988 to 2004 the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Texas. With nearly seventeen years of service, Phillips is the third- ...

become the first Republican elected as Chief Justice of the Texas Supreme Court. Phillips had been appointed to the position in November 1987 by Clements. Phillips was re-elected in 1990, 1996 and 2002.

Phillips' election in 1988 was part of an aggressive grassroots campaign called "Clean Slate '88", a conservative effort that was successful in getting five of its six candidates elected. (Ordinarily there were three justices on the ballot each year, on a nine-justice court, but, because of resignations, there were six races for the Supreme Court on the ballot in November 1988.) By 1998, Republicans held all nine seats on the Court.

1990 Texas gubernatorial campaign

In 1989, Rove encouraged George W. Bush to run for Texas governor, brought in experts to tutor him on policy, and introduced him to local reporters. Eventually, Bush decided not to run, and Rove backed another Republican for governor who lost in the primary.

Other 1990 Texas statewide races

In 1990, two other Rove candidates won: Rick Perry

James Richard Perry (born March 4, 1950) is an American politician who served as the 14th United States secretary of energy from 2017 to 2019 and as the 47th governor of Texas from 2000 to 2015. Perry also ran unsuccessfully for the Republic ...

, the future governor of the state, became agricultural commissioner, and Kay Bailey Hutchison

Kay Bailey Hutchison (born Kathryn Ann Bailey; July 22, 1943) is an American attorney, television correspondent, politician, diplomat, and was the 22nd United States Permanent Representative to NATO from 2017 until 2021. A member of the Republic ...

became state treasurer.

One notable aspect of the 1990 election was the charge that Rove had asked the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice ...

(FBI) to investigate major Democratic officeholders in Texas. In his autobiography, Rove called the whole thing a "myth", saying:

* The FBI did investigate Texas officials during that span, but I had nothing to do with it. The investigation was called "Brilab" and was part of a broad anti-corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense which is undertaken by a person or an organization which is entrusted in a position of authority, in order to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's personal gain. Corruption m ...

probe that looked at officials in Louisiana, Oklahoma, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C., as well as Texas ... An official for the U.S. Department of Agriculture spotted expenses claimed by Hightower's shop that raised red flags ... enough to indict some of Hightower's top aides; they were later found guilty and sent to prison.

* The myth that I had something to do both with spurring the investigation and with airing all of this has stuck around because it is convenient for some to blame me rather than those aides who ran afoul of the law.

1991 Richard L. Thornburgh senatorial campaign and lawsuit

In 1991, United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

Dick Thornburgh

Richard Lewis Thornburgh (July 16, 1932 – December 31, 2020) was an American lawyer, author, and Republican politician who served as the 41st governor of Pennsylvania from 1979 to 1987, and then as the United States attorney general fr ...

resigned to run for a Senate seat in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, one made vacant by John Heinz

Henry John Heinz III (October 23, 1938 – April 4, 1991) was an American businessman and Republican politician from Pennsylvania. Heinz represented the Pittsburgh suburbs in the United States House of Representatives from 1971 to 1977 ...

's death in a helicopter crash. Rove's company worked for the campaign, but it ended with an upset loss to Democrat Harris Wofford.

Rover had been hired by an intermediary Murray Dickman to work for Thornburgh's campaign. Subsequently, Rove sued Thornburgh directly, alleging non-payment for services rendered. The Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is a U.S. political committee that assists the Republican Party of the United States. It is responsible for developing and promoting the Republican brand and political platform, as well as assisting in ...

, worried that the suit would make it hard to recruit good candidates, urged Rove to back off. When Rove refused, the RNC hired Kenneth Starr to write an amicus brief

An ''amicus curiae'' (; ) is an individual or organization who is not a party to a legal case, but who is permitted to assist a court by offering information, expertise, or insight that has a bearing on the issues in the case. The decision on ...

on Thornburgh's behalf. ''Karl Rove & Co. v. Thornburgh'' was heard by U.S. Federal Judge Sam Sparks

Sam Sparks (born 1939) is a Senior Status, Senior United States federal judge, United States district judge of the Austin Division of the United States District Court for the Western District of Texas.

Early life

After graduating from Austin H ...

, who had been appointed by George H.W. Bush in 1991. After a trial in Austin, Rove prevailed.

1992 George H. W. Bush presidential campaign

Rove was fired from the 1992 Bush presidential campaign after he planted a negative story with columnist Robert Novak

Robert David Sanders Novak (February 26, 1931 – August 18, 2009) was an American syndicated columnist, journalist, television personality, author, and conservative political commentator. After working for two newspapers before serving in the ...

about dissatisfaction with campaign fundraising chief Robert Mosbacher Jr. Novak's column suggested a motive when it described the firing of Mosbacher by former Senator Phil Gramm

William Philip Gramm (born July 8, 1942) is an American economist and politician who represented Texas in both chambers of Congress. Though he began his political career as a Democrat, Gramm switched to the Republican Party in 1983. Gramm was a ...

: "Also attending the session was political consultant Karl Rove, who had been shoved aside by Mosbacher." Novak and Rove denied that Rove leaked, but Mosbacher maintained that "Rove is the only one with a motive to leak this. We let him go. I still believe he did it."

During testimony before the CIA leak grand jury, Rove apparently confirmed his prior involvement with Novak in the 1992 campaign leak, according to ''National Journal

''National Journal'' is an advisory services company based in Washington, D.C., offering services in government affairs, advocacy communications, stakeholder mapping, and policy brands research for government and business leaders. It publishes d ...

'' reporter Murray Waas.

1993–2000

1993 Kay Bailey Hutchison senatorial campaign

Rove helped Hutchison win a special Senate election in June 1993. Hutchison defeated Democrat Bob Krueger

Robert Charles Krueger (September 19, 1935 – April 30, 2022) was an American diplomat, politician, and U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from Texas, a U.S. Ambassador, and a member of the Democratic Party. , he was the last Democrat t ...

to fill the last two years of Lloyd Bentsen

Lloyd Millard Bentsen Jr. (February 11, 1921 – May 23, 2006) was an American politician who was a four-term United States Senator (1971–1993) from Texas and the Democratic Party nominee for vice president in 1988 on the Michael Dukakis t ...

's term. Bentsen had resigned to become Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

in the Clinton administration.

1994 Alabama Supreme Court races

In 1994, a group called the Business Council of Alabama hired Rove to help run a slate of Republican candidates for the state supreme court. No Republican had been elected to that court in more than a century. The campaign by the Republicans was unprecedented in the state, which had previously only seen low-key contests. After the election, a court battle over absentee and other ballots followed that lasted more than 11 months. It ended when a federal appeals court judge ruled that disputed absentee ballots could not be counted, and ordered the Alabama Secretary of State

The secretary of state of Alabama is one of the constitutional officers of the U.S. state of Alabama. The office actually predates the statehood of Alabama, dating back to the Alabama Territory. From 1819 to 1901, the secretary of state served ...

to certify the Republican candidate for Chief Justice, Perry Hooper, as the winner. An appeal to the Supreme Court by the Democratic candidate was turned down within a few days, making the ruling final. Hooper won by 262 votes.

Another candidate, Harold See

Harold Frend See, Jr. (born November 7, 1943) is a legal scholar and was an associate justice of the Alabama Supreme Court from 1997 to 2009. The son of Harold F. See, Sr., and Corinne See, he was born at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center in ...

, ran against Mark Kennedy, an incumbent Democratic justice and the son-in-law of George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist a ...

. The race included charges that Kennedy was mingling campaign funds with those of a non-profit

A nonprofit organization (NPO) or non-profit organisation, also known as a non-business entity, not-for-profit organization, or nonprofit institution, is a legal entity organized and operated for a collective, public or social benefit, in co ...

children's foundation he was involved with. A former Rove staffer reported that some within the See camp initiated a whisper campaign that Kennedy was a pedophile

Pedophilia ( alternatively spelt paedophilia) is a psychiatric disorder in which an adult or older adolescent experiences a primary or exclusive sexual attraction to prepubescent children. Although girls typically begin the process of pubert ...

.Ann Richards

Dorothy Ann Richards (née Willis; September 1, 1933 – September 13, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Texas from 1991 to 1995. A Democrat, she first came to national attention as the Texas State Treasurer, w ...

, with $340,000 of that paid to Rove's firm.

Rove has been accused of using the push poll technique to call voters to ask such things as whether people would be "more or less likely to vote for Governor Richards if hey

Hey or Hey! may refer to:

Music

* Hey (band), a Polish rock band

Albums

* ''Hey'' (Andreas Bourani album) or the title song (see below), 2014

* ''Hey!'' (Julio Iglesias album) or the title song, 1980

* ''Hey!'' (Jullie album) or the title ...

knew her staff is dominated by lesbian

A lesbian is a Homosexuality, homosexual woman.Zimmerman, p. 453. The word is also used for women in relation to their sexual identity or sexual behavior, regardless of sexual orientation, or as an adjective to characterize or associate n ...

s". Rove has denied having been involved in circulating these rumors about Richards during the campaign, although many critics nonetheless identify this technique, particularly as used in this instance against Richards, as a hallmark of his career.

1996 Harold See's campaign for Associate Justice, Alabama Supreme Court

A former campaign worker charged that, at Rove's behest, he distributed flyers that anonymously attacked Harold See

Harold Frend See, Jr. (born November 7, 1943) is a legal scholar and was an associate justice of the Alabama Supreme Court from 1997 to 2009. The son of Harold F. See, Sr., and Corinne See, he was born at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center in ...

, their own client. This put the opponent's campaign in an awkward position; public denials of responsibility for the scurrilous flyers would be implausible. Rove's client was elected.

1998 George W. Bush gubernatorial campaign

Rove was an adviser for Bush's 1998 reelection campaign. From July through December 1998, Bush's reelection committee paid Rove & Co. nearly $2.5 million, and also paid the Rove-owned Praxis List Company $267,000 for use of mailing lists. Rove says his work for the Bush campaign included direct mail, voter contact, phone banks, computer services, and travel expenses. Of the $2.5 million, Rove said, ''" out 30 percent of that is postage"''. In all, Bush (primarily through Rove's efforts) raised $17.7 million, with $3.4 million unspent as of March 1999. During the course of this campaign Rove's much-reported feud with Rick Perry began, with Perry's strategists believing Rove gave Perry bad advice in order to help Bush get a larger share of the Hispanic vote.

2000 Harold See campaign for Chief Justice

For the race to succeed Perry Hooper, who was retiring as Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

's chief justice, Rove lined up support for See from a majority of the state's important Republicans.

2000 George W. Bush presidential campaign and the sale of Karl Rove & Co.

In early 1999, Rove sold his 20-year-old direct-mail business, Karl Rove & Co., which provided campaign services to candidates, along with Praxis List Company (in whole or part) to Ted Delisi and Todd Olsen, two young political operatives who had worked on campaigns of some other Rove candidates. Rove helped finance the sale of the company, which had 11 employees. Selling Karl Rove & Co. was a condition that George W. Bush had insisted on before Rove took the job of chief strategist for Bush's presidential bid.[

During the Republican primary, Rove was accused of spreading false rumors that John McCain had fathered an illegitimate black child. Rove denies the accusation.]

George W. Bush administration

When George W. Bush was first inaugurated in January 2001, Rove accepted an appointment as Senior Advisor. He was later given the title Deputy Chief of Staff to the President after the successful 2004 Presidential election. In a November 2004 speech, Bush publicly thanked Rove, calling him "the architect" of his victory over

When George W. Bush was first inaugurated in January 2001, Rove accepted an appointment as Senior Advisor. He was later given the title Deputy Chief of Staff to the President after the successful 2004 Presidential election. In a November 2004 speech, Bush publicly thanked Rove, calling him "the architect" of his victory over John Kerry

John Forbes Kerry (born December 11, 1943) is an American attorney, politician and diplomat who currently serves as the first United States special presidential envoy for climate. A member of the Forbes family and the Democratic Party, he ...

in the 2004 presidential election. In April 2006, Rove was reassigned from his policy development role to one focusing on strategic and tactical planning in anticipation of the November 2006 congressional elections.

Iraq War

Rove played a leading role in the lead-up to the Iraq War.White House Iraq Group

The White House Iraq Group (aka, White House Information Group or WHIG) was a working group of the White House set up in August 2002 and tasked with disseminating information supporting the positions of the George W. Bush administration relati ...

(WHIG), an internal White House working group

A working group, or working party, is a group of experts working together to achieve specified goals. The groups are domain-specific and focus on discussion or activity around a specific subject area. The term can sometimes refer to an interdis ...

established in August 2002, eight months prior to the 2003 invasion of Iraq

The 2003 invasion of Iraq was a United States-led invasion of the Republic of Iraq and the first stage of the Iraq War. The invasion phase began on 19 March 2003 (air) and 20 March 2003 (ground) and lasted just over one month, including ...

. WHIG was charged with developing a strategy "for publicizing the White House's assertion that Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolutio ...

posed a threat to the United States.".Chief of Staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

Andrew Card

Andrew Hill Card Jr. (born May 10, 1947) is an American politician and academic administrator who was White House Chief of Staff under President George W. Bush from 2001 to 2006, as well as head of Bush's White House Iraq Group. Card served as ...

, national security advisor A national security advisor serves as the chief advisor to a national government on matters of security. The advisor is not usually a member of the government's cabinet but is usually a member of various military or security councils.

National sec ...

Condoleezza Rice

Condoleezza Rice ( ; born November 14, 1954) is an American diplomat and political scientist who is the current director of the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. A member of the Republican Party, she previously served as the 66th Un ...

, her deputy Stephen Hadley

Stephen John Hadley (born February 13, 1947) is an American attorney and senior government official who served as the 20th United States National Security Advisor from 2005 to 2009. He served under President George W. Bush during the second term ...

, Vice President Dick Cheney

Richard Bruce Cheney ( ; born January 30, 1941) is an American politician and businessman who served as the 46th vice president of the United States from 2001 to 2009 under President George W. Bush. He is currently the oldest living former ...

's Chief of Staff Lewis "Scooter" Libby, legislative liaison Nicholas E. Calio, and communication strategists Mary Matalin, Karen Hughes

Karen Parfitt Hughes (born December 27, 1956) is the global vice chair of the public relations firm Burson-Marsteller. She served as the Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs in the U.S. Department of State and as a ...

, and James R. Wilkinson.

Quoting one unnamed WHIG member, ''The Washington Post'' explained that the task force's mission was to "educate the public" about the threat posed by Saddam and (in the reporters' words) ''" oset strategy for each stage of the confrontation with Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

"''. Rove's "strategic communications" task force within WHIG helped write and coordinate speeches by senior Bush administration officials, emphasizing Iraq's purported nuclear threat. The White House Iraq Group was "little known" until a subpoena

A subpoena (; also subpœna, supenna or subpena) or witness summons is a writ issued by a government agency, most often a court, to compel testimony by a witness or production of evidence under a penalty for failure. There are two common types of ...

for its notes, email, and attendance records was issued by CIA leak investigator Patrick Fitzgerald

Patrick J. Fitzgerald (born December 22, 1960) is an American lawyer and partner at the law firm of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom since October 2012.

For more than a decade, until June 30, 2012, Fitzgerald was the United States Attorney ...

in January 2004.

Valerie Plame affair

On August 29, 2003, retired ambassador Joseph C. Wilson IV

Joseph Charles Wilson IV (November 6, 1949 – September 27, 2019) was an American diplomat who was best known for his 2002 trip to Niger to investigate allegations that Saddam Hussein was attempting to purchase yellowcake uranium; his '' Ne ...

claimed that Rove leaked the identity of Wilson's wife, Valerie Plame

Valerie Elise Plame (born August 13, 1963) is an American writer, spy novelist, and former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) officer. As the subject of the 2003 Plame affair, also known as the CIA leak scandal, Plame's identity as a CIA officer ...

, as a Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA) employee,The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' in which he criticized the Bush administration's citation of the yellowcake documents among the justifications for the War in Iraq

This is a list of wars involving the Republic of Iraq and its predecessor states.

Other armed conflicts involving Iraq

* Wars during Mandatory Iraq

** Ikhwan raid on South Iraq 1921

* Smaller conflicts, revolutions, coups and periphery confli ...

enumerated in Bush's 2003 State of the Union Address

The State of the Union Address (sometimes abbreviated to SOTU) is an annual message delivered by the president of the United States to a joint session of the United States Congress near the beginning of each calendar year on the current conditi ...

.

In late August 2006, it became known that Richard L. Armitage was responsible for the leak. The investigation led to felony charges being filed against Lewis "Scooter" Libby for perjury

Perjury (also known as foreswearing) is the intentional act of swearing a false oath or falsifying an affirmation to tell the truth, whether spoken or in writing, concerning matters material to an official proceeding."Perjury The act or an inst ...

and obstruction of justice

Obstruction of justice, in United States jurisdictions, is an act that involves unduly influencing, impeding, or otherwise interfering with the justice system, especially the legal and procedural tasks of prosecutors, investigators, or other gov ...

. Eventually, Libby was found guilty by a jury.Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nominations ...

issued a subpoena to Attorney General Gonzales compelling the Department of Justice to produce all email from Rove regarding the Dismissal of U.S. attorneys controversy

On December 7, 2006, the George W. Bush Administration's Department of Justice ordered the unprecedented midterm dismissal of seven United States attorneys. Congressional investigations focused on whether the Department of Justice and the White ...

, no matter what email account Rove may have used, with a deadline of May 15, 2007, for compliance. The subpoena also demanded relevant email previously produced in the Valerie Plame

Valerie Elise Plame (born August 13, 1963) is an American writer, spy novelist, and former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) officer. As the subject of the 2003 Plame affair, also known as the CIA leak scandal, Plame's identity as a CIA officer ...

controversy and the investigation regarding the CIA leak scandal (2003)

The Plame affair (also known as the CIA leak scandal and Plamegate) was a political scandal that revolved around journalist Robert Novak's public identification of Valerie Plame as a covert Central Intelligence Agency officer in 2003.

In 2002, ...

. On August 31, 2007, Karl Rove resigned without responding to the Senate Judiciary Committee subpoena, saying, "I just think it's time to leave."

Scott McClellan

Scott McClellan (born February 14, 1968) is the former White House Press Secretary (2003–06) for President George W. Bush, he was the 24th person to hold this post. He was also the author of a controversial No. 1 ''New York Times'' bestseller ...

claims in his book '' What Happened: Inside the Bush White House and Washington's Culture of Deception'', published in the spring of 2008 by Public Affairs Books, that the statements he made in 2003 about Rove's lack of involvement in the Valerie Plame affair were untrue, and that he had been encouraged to repeat such untruths. His book has been widely disputed, however, with many key members of McClellan's own staff telling a completely different story. Former CNN commentator Robert Novak has questioned if McClelland wrote the book himself. It was also revealed that the publisher was seeking a negative book to increase sales.

2006 Congressional elections and beyond

On October 24, 2006, two weeks before the Congressional election, in an interview with National Public Radio

National Public Radio (NPR, stylized in all lowercase) is an American privately and state funded nonprofit media organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with its NPR West headquarters in Culver City, California. It differs from other n ...

's Robert Siegel

Robert Charles Siegel (born June 26, 1947) is an American retired radio journalist. He was one of the co-hosts of the National Public Radio evening news broadcast ''All Things Considered'' from 1987 until his retirement in January 2018.

Early ...

, Rove insisted that his insider polling data forecast Republican retention of both houses. In the election the Democrats won both houses of Congress. The ''White House Bulletin'', published by Bulletin News, cited rumors of Rove's impending departure from the White House staff: ''"'Karl represents the old style and he's got to go if the Democrats are going to believe Bush's talk of getting along', said a key Bush advisor."'' However, while allowing that many Republican members of Congress are "resentful of the way he and the White House conducted the losing campaign", ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' also stated that, ''"White House officials say President Bush has every intention of keeping Mr. Rove on through the rest of his term."''

Torture

Rove defended the Bush administration's use of waterboarding

Waterboarding is a form of torture in which water is poured over a cloth covering the face and breathing passages of an immobilized captive, causing the person to experience the sensation of drowning. In the most common method of waterboard ...

, a form of torture.

E-mail scandal

Due to investigations into White House staffers' e-mail communication related to the controversy over the dismissal of United States Attorneys, it was discovered that many White House staff members, including Rove, had exchanged documents using Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is a U.S. political committee that assists the Republican Party of the United States. It is responsible for developing and promoting the Republican brand and political platform, as well as assisting in ...

e-mail servers such as gwb43.com and georgewbush.com or personal e-mail accounts with third party providers such as BlackBerry

The blackberry is an edible fruit produced by many species in the genus ''Rubus'' in the family Rosaceae, hybrids among these species within the subgenus ''Rubus'', and hybrids between the subgenera ''Rubus'' and ''Idaeobatus''. The taxonomy ...

, considered a violation of the Presidential Records Act

The Presidential Records Act (PRA) of 1978, , is an Act of the United States Congress governing the official records of Presidents and Vice Presidents created or received after January 20, 1981, and mandating the preservation of all presidentia ...

. Over 500 of Rove's emails were mistakenly sent to a parody website, who forwarded them to an investigative reporter

Investigative journalism is a form of journalism in which reporters deeply investigate a single topic of interest, such as serious crimes, political corruption, or corporate wrongdoing. An investigative journalist may spend months or years rese ...

.

Congressional subpoenas

On May 22, 2008, Rove was subpoena

A subpoena (; also subpœna, supenna or subpena) or witness summons is a writ issued by a government agency, most often a court, to compel testimony by a witness or production of evidence under a penalty for failure. There are two common types of ...

ed by House Judiciary Committee

The U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary, also called the House Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of the United States House of Representatives. It is charged with overseeing the administration of justice within the federal courts, ...

Chairman John Conyers

John James Conyers Jr. (May 16, 1929October 27, 2019) was an American politician of the Democratic Party who served as a U.S. representative from Michigan from 1965 to 2017. The districts he represented always included part of western Detroit ...

to testify on the politicization of the Department of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

. But on July 10, Rove refused to obey the congressional subpoena, citing executive privilege

Executive privilege is the right of the president of the United States and other members of the executive branch to maintain confidential communications under certain circumstances within the executive branch and to resist some subpoenas and othe ...

as his reason.

On February 23, 2009, Rove was required by Congressional subpoena to testify before the House Judiciary Committee concerning his knowledge of the controversy over the dismissal of seven U.S. Attorneys, and the alleged political prosecution of former Alabama Governor Don Siegelman

Donald Eugene Siegelman ( ; born February 24, 1946) is a former American politician, lawyer and convicted felon who was the 51st governor of Alabama from 1999 to 2003. A member of the Democratic Party, as of , Siegelman is the last Democrat, as w ...

, but did not appear on that date. He and former White House Counsel

The White House counsel is a senior staff appointee of the president of the United States whose role is to advise the president on all legal issues concerning the president and their administration. The White House counsel also oversees the Of ...

Harriet Miers later agreed to testify under oath before Congress about these matters.

On July 7 and July 30, 2009, Rove testified before the House Judiciary Committee regarding questions about the dismissal of seven U.S. Attorneys under the Bush Administration. Rove was also questioned regarding the federal prosecution of former Alabama Governor Don Siegelman

Donald Eugene Siegelman ( ; born February 24, 1946) is a former American politician, lawyer and convicted felon who was the 51st governor of Alabama from 1999 to 2003. A member of the Democratic Party, as of , Siegelman is the last Democrat, as w ...

, who was convicted of fraud. The Committee concluded that Rove had played a significant role in the Attorney firings.

Activities after leaving the White House

Activities in 2008

Shortly after leaving the White House, Rove was hired to write about the 2008 Presidential Election for ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis (businessman), Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print m ...

''. He was also later hired as a contributor for ''The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' is an American business-focused, international daily newspaper based in New York City, with international editions also available in Chinese and Japanese. The ''Journal'', along with its Asian editions, is published ...

'' and a political analyst for Fox News

The Fox News Channel, abbreviated FNC, commonly known as Fox News, and stylized in all caps, is an American multinational conservative cable news television channel based in New York City. It is owned by Fox News Media, which itself is o ...

. Rove was an informal advisor to 2008 Republican presidential candidate John McCain

John Sidney McCain III (August 29, 1936 – August 25, 2018) was an American politician and United States Navy officer who served as a United States senator from Arizona from 1987 until his death in 2018. He previously served two te ...

, and donated $2,300 to his campaign. His memoir, ''Courage and Consequence'', was published in March 2010. One advance reviewer, Dana Milbank

Dana Timothy Milbank (born April 27, 1968) is an American author and columnist for ''The Washington Post''.

Personal life

Milbank was born to a Jewish family, the son of Ann C. and Mark A. Milbank. He is a graduate of Yale University, where he wa ...

of ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'', said of the book that Rove "revives claims discredited long ago". The controversial book inspired a grassroots

A grassroots movement is one that uses the people in a given district, region or community as the basis for a political or economic movement. Grassroots movements and organizations use collective action from the local level to effect change at t ...

rock and roll compilation of a similar name, Courage and Consequence, that was released a week before the memoir.

On March 9, 2008, Rove appeared at the University of Iowa

The University of Iowa (UI, U of I, UIowa, or simply Iowa) is a public research university in Iowa City, Iowa, United States. Founded in 1847, it is the oldest and largest university in the state. The University of Iowa is organized into 12 co ...

as a paid speaker to a crowd of approximately 1,000. He was met with hostility and two students were removed by police after attempting a citizen's arrest

A citizen's arrest is an arrest made by a private citizen – that is, a person who is not acting as a sworn law-enforcement official. In common law jurisdictions, the practice dates back to medieval England and the English common law, in which ...

for alleged crimes committed during his time with the Bush administration. Near the end of the speech, a member of the audience asked, "Can we have our $40,000 back?" Rove replied, "No, you can't."

On June 24, 2008, Rove said of Democratic presidential nominee Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

, "Even if you never met him, you know this guy. He's the guy at the country club with the beautiful date, holding a martini and a cigarette that stands against the wall and makes snide comments about everyone."

In July 2008, Rove, who was hired by Fox News to provide analysis for the network's November 2008 election coverage, defended his role on the news team to the Television Critics Association.John Edwards

Johnny Reid Edwards (born June 10, 1953) is an American lawyer and former politician who served as a U.S. senator from North Carolina. He was the Democratic nominee for vice president in 2004 alongside John Kerry, losing to incumbents George ...

on September 26, 2008, at the University at Buffalo

The State University of New York at Buffalo, commonly called the University at Buffalo (UB) and sometimes called SUNY Buffalo, is a public research university with campuses in Buffalo and Amherst, New York. The university was founded in 18 ...

. However, Edwards dropped out and was replaced by General Wesley Clark

Wesley Kanne Clark (born December 23, 1944) is a retired United States Army officer. He graduated as valedictorian of the class of 1966 at West Point and was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship to the University of Oxford, where he obtained a degree ...

.

2009–present

In September 2009, Rove was inducted into the Scandinavian-American Hall of Fame. The induction became a major dispute as political views clashed over the announcement. Governor John Hoeven

John Henry Hoeven III ( ; born March 13, 1957) is an American banker and politician serving as the senior U.S. senator from North Dakota, a seat he has held since 2011. A member of the Republican Party, Hoeven served as the 31st governor of Nort ...

was scheduled to introduce Rove during the SAHF banquet but did not attend. At that time, Rove was being investigated by Democrats in Congress for his role in the 2006 dismissal of nine U.S. Attorneys.

In 2010, with former RNC chair Ed Gillespie

Edward Walter Gillespie (born August 1, 1961) is an American politician, strategist, and lobbyist who served as the 61st Chair of the Republican National Committee from 2003 to 2005 and was counselor to the President from 2007 to 2009 during the ...

, Rove helped found American Crossroads

American Crossroads is a US Super PAC that raises funds from donors to advocate for certain candidates of the Republican Party. It has pioneered many of the new methods of fundraising opened up by the Supreme Court's ruling in ''Citizens United' ...

, a Republican 527 organization

A 527 organization or 527 group is a type of U.S. tax-exempt organization organized under Section 527 of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code (). A 527 group is created primarily to influence the selection, nomination, election, appointment or de ...

raising money for the 2012 election effort.Todd Akin

William Todd Akin (July 5, 1947 – October 3, 2021) was an American politician who served as the U.S. representative for from 2001 to 2013. He was a member of the Republican Party. Born in New York City, Akin grew up in the Greater St. Louis ...

's comments regarding " legitimate rape" and the notion that raped women are unlikely to become pregnant, Rove joked about murdering the Missouri Senate candidate, saying "We should sink Todd Akin. If he's found mysteriously murdered, don't look for my whereabouts!" After multiple news outlets picked up on the story, Rove apologized for the remark. Rove's Crossroads GPS

American Crossroads is a US Super PAC that raises funds from donors to advocate for certain candidates of the Republican Party. It has pioneered many of the new methods of fundraising opened up by the Supreme Court's ruling in ''Citizens United' ...

organization had previously pulled its television advertising from Missouri in the wake of the comments.

On November 6, 2012, Rove protested Fox News' call of the 2012 presidential election for Obama, prompting host Megyn Kelly

Megyn Marie Kelly (; born November 18, 1970) is an American journalist and media personality. She currently hosts a talk show and podcast, ''The Megyn Kelly Show'', that airs live daily on SiriusXM. She was a talk show host at Fox News from 20 ...

to ask him, "Is this just math that you do as a Republican to make yourself feel better? Or is this real?"

In 2013 Rove and the PAC American Crossroads created the Conservative Victory Project The Conservative Victory Project is a political initiative launched in 2013 by Karl Rove, the prominent Republican political activist, and the super-PAC American Crossroads

American Crossroads is a US Super PAC that raises funds from donors to a ...

for the purpose of supporting electable conservative candidates.Tea Party movement