Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

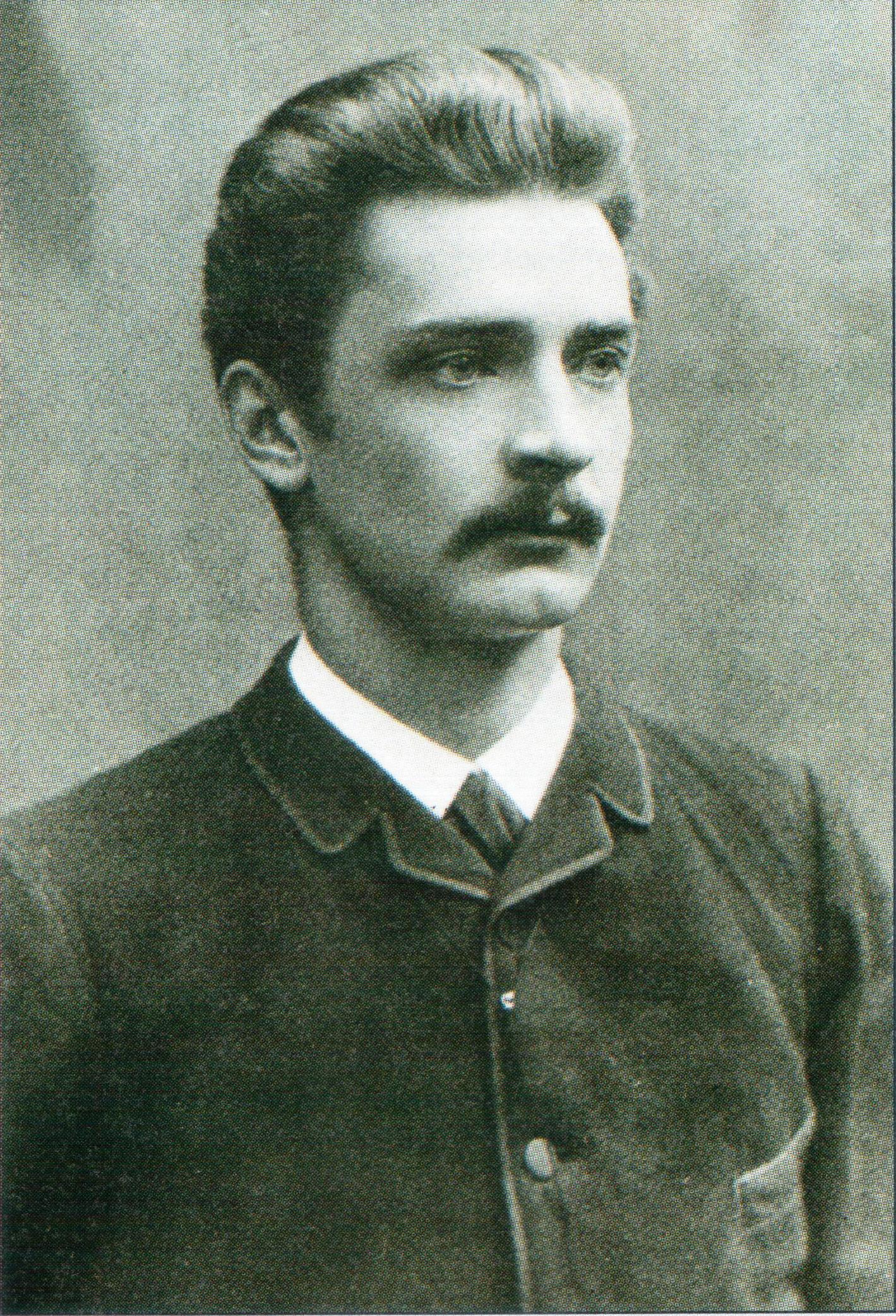

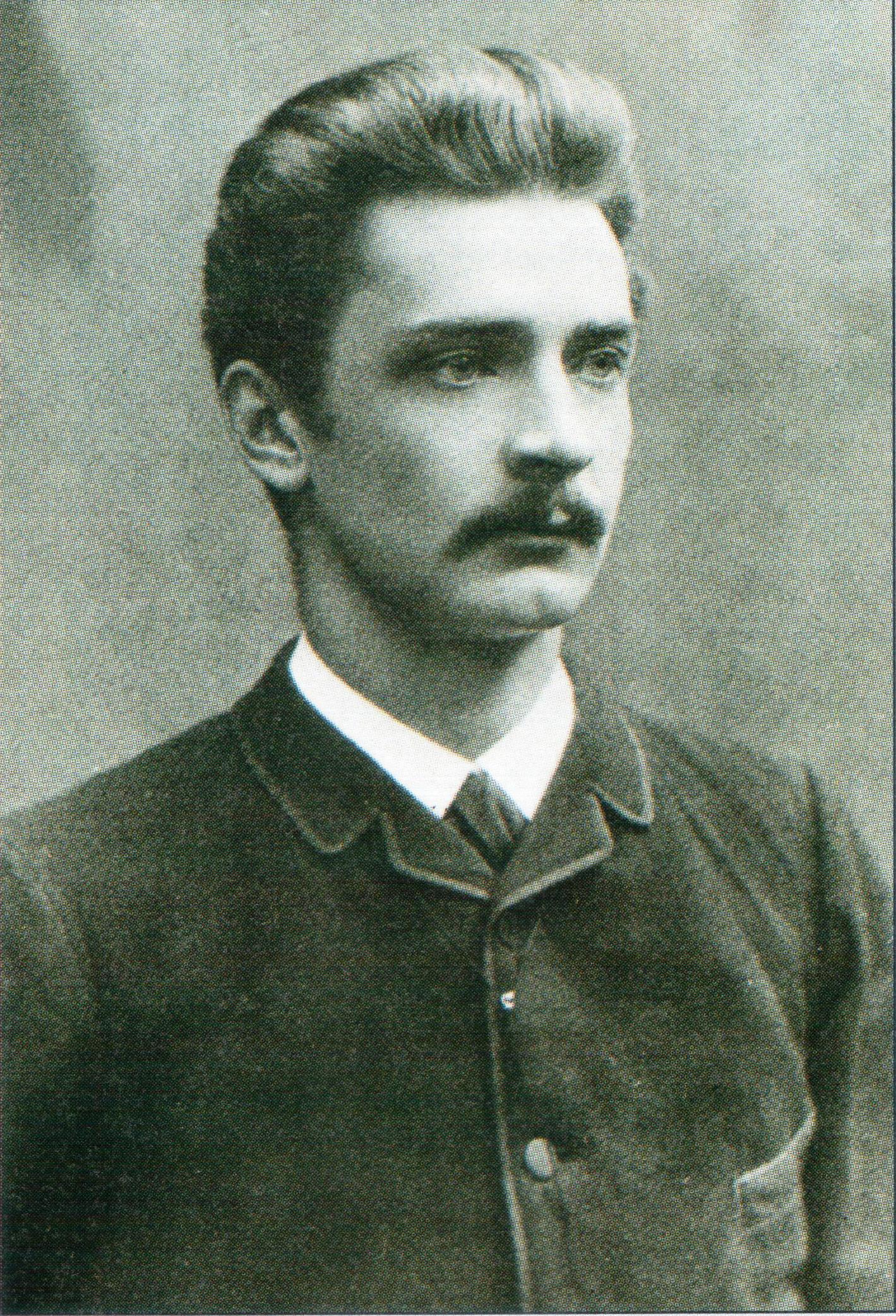

Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg (, ; 28 January 1865 – 22 September 1952) was a Finnish

Ståhlberg and his family lived in

Ståhlberg and his family lived in

Ståhlberg emerged as a candidate for president, with the support of the newly formed National Progressive Party, of which he was a member, and the Agrarian League. In the 1919 Finnish presidential election, he was elected by Parliament as President of the Republic on 25 July 1919, defeating

Ståhlberg emerged as a candidate for president, with the support of the newly formed National Progressive Party, of which he was a member, and the Agrarian League. In the 1919 Finnish presidential election, he was elected by Parliament as President of the Republic on 25 July 1919, defeating

Ståhlberg did not seek re-election in 1925, finding his difficult term of office a great strain. He also believed that the right-wing and the monarchists would become more reconciled to the republic if he stepped down. According to the longtime late Agrarian and Centrist politician Johannes Virolainen, he believed that the incumbent president was too much favoured over the other candidates while standing for re-election. He was offered the post of Chancellor of the University of Helsinki, but declined it, instead becoming a member of the government's Law Drafting Committee. He also served as a National Progressive member of Parliament again, as a member for the Uusimaa constituency from 1930 to 1933.

In 1930, activists from the right-wing Lapua Movement kidnapped him and his wife, attempting to send them to the

Ståhlberg did not seek re-election in 1925, finding his difficult term of office a great strain. He also believed that the right-wing and the monarchists would become more reconciled to the republic if he stepped down. According to the longtime late Agrarian and Centrist politician Johannes Virolainen, he believed that the incumbent president was too much favoured over the other candidates while standing for re-election. He was offered the post of Chancellor of the University of Helsinki, but declined it, instead becoming a member of the government's Law Drafting Committee. He also served as a National Progressive member of Parliament again, as a member for the Uusimaa constituency from 1930 to 1933.

In 1930, activists from the right-wing Lapua Movement kidnapped him and his wife, attempting to send them to the

K. J. Ståhlberg

in The Presidents of Finland * {{DEFAULTSORT:Stahlberg, Kaarlo Juho 1865 births 1952 deaths Academic personnel of the University of Helsinki People from Suomussalmi People from Oulu Province (Grand Duchy of Finland) Finnish Lutherans Young Finnish Party politicians National Progressive Party (Finland) politicians Presidents of Finland Finnish senators Speakers of the Parliament of Finland Members of the Parliament of Finland (1908–09) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1909–10) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1913–16) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1916–17) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1917–19) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1930–33) Kidnapped politicians People of the Finnish Civil War (White side) Finnish legal scholars Grand Crosses of the Order of the Cross of Liberty Liberalism Burials at Hietaniemi Cemetery University of Helsinki alumni

jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyses and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal qualification in law and often a legal practitioner. In the U ...

and academic, which was one of the most important pioneers of republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. ...

in the country. He was the first president of Finland (1919–1925) and a liberal nationalist.

Ståhlberg was an important figure in the years of the Finland's independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the stat ...

and constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

, driving his Republican program through adversity. As a jurist, he anchored the state in liberal democracy

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into ...

, guarded the fragile germ of the rule of law, and embarked on internal reforms. In implementing the form of government of 1919, Ståhlberg piloted an independent Finland towards acting in world politics; in presidential-led foreign

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

and security policy

Security policy is a definition of what it means to ''be secure'' for a system, organization or other entity. For an organization, it addresses the constraints on behavior of its members as well as constraints imposed on adversaries by mechanisms ...

, he relied on international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

and diplomacy

Diplomacy comprises spoken or written communication by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.Ronald Peter Barston, ''Modern diplomacy'', Pearson Education, 2006, p. ...

.

It was only after the opening of private archives of President J. K. Paasikivi

Juho Kusti Paasikivi (; 27 November 1870 – 14 December 1956) was the seventh president of Finland (1946–1956). Representing the Finnish Party until its dissolution in 1918 and then the National Coalition Party, he also served as Prime Minister ...

that it was realized that Ståhlberg had a very significant political role as a “ éminence grise” until his death. He was asked for advice and opinions, which were also followed. Paasikivi highly valued Ståhlberg, and even described his predecessor in exaggerated words: “Ståhlberg was a man who never made mistakes”.

Biography

Early life

Ståhlberg was born in Suomussalmi, in the Kainuu region of the Grand Duchy of Finland, back when Finland was part of theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

. He was the second child of Johan (Janne) Gabriel Ståhlberg, an assistant pastor, and Amanda Gustafa Castrén. On both sides of his family, Ståhlberg's male forebears had been Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

clergymen. He was christened ''Carl Johan'' (), but later Finnicize

Finnicization (also finnicisation, fennicization, fennicisation) is the changing of one's personal names from other languages (usually Swedish) into Finnish. During the era of National Romanticism in Finland, many people, especially Fennomans, ...

d his forenames to ''Kaarlo Juho'' (), as did most Fennomans (i.e. the supporters of Finnish language

Finnish ( endonym: or ) is a Uralic language of the Finnic branch, spoken by the majority of the population in Finland and by ethnic Finns outside of Finland. Finnish is one of the two official languages of Finland (the other being Swedi ...

and culture instead of Swedish).

Ståhlberg and his family lived in

Ståhlberg and his family lived in Lahti

Lahti (; sv, Lahtis) is a city and municipality in Finland. It is the capital of the region of Päijänne Tavastia (Päijät-Häme) and its growing region is one of the main economic hubs of Finland. Lahti is situated on a bay at the southern e ...

, where he also went for grammar school. Ståhlberg's father died when he was a boy, leaving his family in a difficult financial position. The family moved to Oulu

Oulu ( , ; sv, Uleåborg ) is a city, municipality and a seaside resort of about 210,000 inhabitants in the region of North Ostrobothnia, Finland. It is the most populous city in northern Finland and the fifth most populous in the country after ...

, where the children entered school. Kaarlo's mother Amanda worked to support the family until her death in 1879. Ståhlberg's family had always spoken and supported the Finnish language

Finnish ( endonym: or ) is a Uralic language of the Finnic branch, spoken by the majority of the population in Finland and by ethnic Finns outside of Finland. Finnish is one of the two official languages of Finland (the other being Swedi ...

, and the young Ståhlberg was enrolled in Oulu's private Finnish lycee, where he would excel, and was the primus of his class. In 1889 he graduated as a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

in Law from the University of Helsinki

The University of Helsinki ( fi, Helsingin yliopisto, sv, Helsingfors universitet, abbreviated UH) is a public research university located in Helsinki, Finland since 1829, but founded in the city of Turku (in Swedish ''Åbo'') in 1640 as the R ...

. He gained his Doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''l ...

in Law in 1893.

Career as academic and civil servant

Ståhlberg soon began a very long career as the presenter and planner of the Senate's legislation, during the period when Finland was a RussianGrand Duchy

A grand duchy is a country or territory whose official head of state or ruler is a monarch bearing the title of grand duke or grand duchess.

Relatively rare until the abolition of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the term was often used in th ...

. He was a "''constitutionalist''" - supporting the already existing Finnish constitutional framework and constitutional legislative policies, including legislative resistance, against the attempted Russification of Finland. He also came to support the call for women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

, and had a moderate line on Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholi ...

.

Ståhlberg served as secretary of the Diet of Finland

The Diet of Finland ( Finnish ''Suomen maapäivät'', later ''valtiopäivät''; Swedish ''Finlands Lantdagar''), was the legislative assembly of the Grand Duchy of Finland from 1809 to 1906 and the recipient of the powers of the Swedish Ri ...

's finance committee in 1891 before being appointed as an assistant professor of Administrative Law and Economics at the University of Helsinki

The University of Helsinki ( fi, Helsingin yliopisto, sv, Helsingfors universitet, abbreviated UH) is a public research university located in Helsinki, Finland since 1829, but founded in the city of Turku (in Swedish ''Åbo'') in 1640 as the R ...

in 1894. It was at this time that he began his active involvement in politics, becoming a member of the Young Finnish Party

The Young Finnish Party or Constitutional-Fennoman Party ( fi, Nuorsuomalainen Puolue or ) was a liberal and nationalist political party in the Grand Duchy of Finland. It began as an upper-class reformist movement during the 1870s and formed as a ...

.

In 1893, Ståhlberg married his first wife, Hedvig Irene Wåhlberg (1869–1917). They had six children together: Kaarlo (1894–1977), Aino (1895–1974), Elli (1899–1986), Aune (1901–1967), Juho (1907–1973), and Kyllikki (1908–1994).

In 1898, Ståhlberg was appointed as Protocol Secretary for the Senate's civil affairs subdepartment. This was the second-highest Rapporteur position in the Finnish government. This appointment to a senior position in the Finnish administration was approved by the new Governor General of Finland

The governor-general of Finland ( fi, Suomen kenraalikuvernööri; sv, generalguvernör över Finland; russian: генерал-губернатор Финляндии) was the military commander and the highest administrator of Finland sporadic ...

, Nikolai Bobrikov

Nikolay Ivanovich Bobrikov (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Бо́бриков; in St. Petersburg – June 17, 1904 in Helsinki, Grand Duchy of Finland) was a Russian general and politician. He was the Governor-General of Finl ...

, whose term in office saw the beginning of the period of Russification, and whose policies represented all that the ''constitutionalist'' Ståhlberg was opposed to. Ståhlberg was elected in 1901 as a member of Helsinki City Council, serving until 1903. In 1902, he was dismissed as Protocol Secretary, due to his strict legalist views, and his opposition to legislation on compulsory military service.

Career as politician

Ståhlberg participated in theDiet of Finland

The Diet of Finland ( Finnish ''Suomen maapäivät'', later ''valtiopäivät''; Swedish ''Finlands Lantdagar''), was the legislative assembly of the Grand Duchy of Finland from 1809 to 1906 and the recipient of the powers of the Swedish Ri ...

(1904–1905) as a member of the Estate of Burgesses. In 1905, he was appointed as a Senator in the newly formed Senate of Leo Mechelin, with responsibility for trade and industry. One of the most important tasks facing the new ''constitutionalist'' Senate was to consider proposals for the reform of the Diet of Finland

The Diet of Finland ( Finnish ''Suomen maapäivät'', later ''valtiopäivät''; Swedish ''Finlands Lantdagar''), was the legislative assembly of the Grand Duchy of Finland from 1809 to 1906 and the recipient of the powers of the Swedish Ri ...

and, although initially sceptical about some of the proposal, Ståhlberg played a role in the drafting of the legislation which created the Parliament of Finland

The Parliament of Finland ( ; ) is the unicameral and supreme legislature of Finland, founded on 9 May 1906. In accordance with the Constitution of Finland, sovereignty belongs to the people, and that power is vested in the Parliament. The ...

. Ståhlberg resigned from the Senate in 1907, due to Parliament's rejection of a Senate bill on the prohibition of alcohol.

The following year he resumed his academic career and was appointed as Professor of Administrative Law at the University of Helsinki, a position he retained until 1918. During his time in that post he wrote his most influential piece of work, "''Finnish administrative law, volumes I & II''." He also remained active in politics, being elected to the central committee of the Young Finnish Party. In 1908, Ståhlberg was elected as a member of Parliament for the Southern Häme constituency, which he represented until 1910. He also served as a member for the Southern Oulu constituency from 1913 until his appointment as President of the Supreme Administrative Court in 1918. Ståhlberg also served as Speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** In ...

of the Parliament in 1914.

After the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and some ...

in 1917, Ståhlberg was backed by the majority of the non-socialists members of Parliament as a candidate to become Vice-Chairman of the Economic Department of the Senate. However, he did not receive the support of the Social Democrats, which he had made a precondition of his being elected. Instead, the Social Democrat Oskari Tokoi was elected, with Ståhlberg being appointed as chairman of the Constitutional Council. This body had been set up earlier to draw up plans for a new form of government for Finland, in light of the events surrounding the February Revolution and the abdication of Nicholas II as Emperor of Russia and Grand Duke of Finland

Grand Duke of Finland, or, more accurately, the Grand Prince of Finland ( fi, Suomen suuriruhtinas, sv, Storfurste av Finland, rus, Великий князь Финляндский, r=Velikiy knyaz' Finlyandskiy, p=vʲɪˈlʲikɪj knʲæsʲ f� ...

.

The new form of government approved by the council was largely based on the 1772 Instrument of Government, dating from the period of Swedish rule. The proposed form of government was rejected by the Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of the Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately ...

, and was then left largely forgotten for a time due to the confusion and urgency of the situation surrounding the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

and the declaration of Finland's independence.

Architect of the Finnish constitution

After Finland gained its independence in December 1917, the Constitutional Committee drafted new proposals for a form of government of an independent Republic of Finland. As chairman of the council, Ståhlberg was involved in the drafting and re-drafting of constitutional proposals during 1918, when the impact of theFinnish Civil War

The Finnish Civil War; . Other designations: Brethren War, Citizen War, Class War, Freedom War, Red Rebellion and Revolution, . According to 1,005 interviews done by the newspaper ''Aamulehti'', the most popular names were as follows: Civil W ...

, and debates between republicans and monarchists on the future constitution, all led to various proposals. His proposals would eventually be enacted as the Constitution of Finland in 1919. In 1918, Ståhlberg supported the idea of republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

instead of a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

which was supported by more conservative victors of the civil war. Ståhlberg's appointment as the first President of the Supreme Administrative Court in 1918 meant that he relinquished his role as a member of Parliament, and was therefore not involved in the election by the Parliament of Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse

Frederick Charles Louis Constantine, Prince and Landgrave of Hesse (german: Friedrich Karl Ludwig Konstantin Prinz und Landgraf von Hessen-Kassel; fi, Fredrik Kaarle; 1 May 1868 – 28 May 1940), was the brother-in-law of the German Emp ...

as King of Finland

This is a list of monarchs and heads of state of Finland; that is, the kings of Sweden with regents and viceroys of the Kalmar Union, the grand dukes of Finland, a title used by most Swedish monarchs, up to the two-year regency following the in ...

in October of that year. As it became clear that Finland would be a republic, Stålberg also championed direct election of the President of Finland, but the Council of State chose the electoral college system, although the first President would be elected by Parliament.

First President of Finland

Ståhlberg emerged as a candidate for president, with the support of the newly formed National Progressive Party, of which he was a member, and the Agrarian League. In the 1919 Finnish presidential election, he was elected by Parliament as President of the Republic on 25 July 1919, defeating

Ståhlberg emerged as a candidate for president, with the support of the newly formed National Progressive Party, of which he was a member, and the Agrarian League. In the 1919 Finnish presidential election, he was elected by Parliament as President of the Republic on 25 July 1919, defeating Carl Gustaf Mannerheim

Carl Gustaf Mannerheim may refer to:

* Carl Gustaf Mannerheim (naturalist) (1797–1854), Finnish entomologist and governor

* Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim

Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (, ; 4 June 1867 – 27 January 1951) was a Finnish ...

(the candidate supported by the National Coalition and Swedish People's parties) by 143 votes to 50.

Ståhlberg was inaugurated as the first President of the Republic on the following day, and reluctantly moved out of his home in Helsinki to take up residence in the Presidential Palace.

Ståhlberg had been a widower since 1917, but in 1920, as president, he married his second wife, Ester Hällström (1870–1950). He was also very formal and, due to his shyness, wrote everything he had to say in public beforehand. He also had a distaste for official occasions, and he did not like travel or state visits, which is why, despite invitations and exhortations, he made no visits abroad during his presidency and received only one guest, Estonian President Konstantin Päts in May 1922. The Estonian head of state's visit was the first official visit to independent Finland. Finland's Ambassador to Stockholm, Werner Söderhjelm, repeatedly offered Ståhlberg a visit to its western neighbor Sweden, but Ståhlberg maintained his position:The first official visit of the President of Finland abroad was made only by his successor, President L. K. Relander.

As the first President of the Republic, Ståhlberg had to form various presidential precedents and interpretations of how the office of President should be conducted. His term in office was also marked by a succession of short-lived governments. During his time as president, Ståhlberg nominated and appointed eight governments. These were mostly coalitions of the Agrarians and the National Progressive, National Coalition and Swedish People's parties, although Ståhlberg also appointed two caretaker governments. Importantly, Ståhlberg generally supported all the governments that he nominated, although he also sometimes disagreed with them.

He forced Kyösti Kallio's first government to resign in January 1924, when he demanded early elections to restore the full membership of Parliament - 200 deputies - and Kallio disagreed. The Parliament had lacked 27 deputies since August 1923, when the Communist deputies had been arrested on suspicions of treason.

Ståhlberg supported moderate social and economic reforms to make even the former Reds accept the democratic republic. He pardoned

most of the Red prisoners, despite the strong criticism that this aroused from many right-wing Finns, especially the White veterans

of the Civil War and several senior army officers. He signed into law bills that gave the trade unions an equal power with the employers' organizations to negotiate labour contracts, a bill to improve the public care for the poor, and the Lex Kallio law which distributed land from the wealthy landowners to the former tenant farmers and other landless rural people.

In foreign policy Ståhlberg was markedly reserved towards Sweden, largely as a consequence of the Åland crisis, which marked the early years of his presidency. He was also cautious towards Germany, and generally unsuccessful in his attempts to establish closer contacts with Poland, the United Kingdom and France.

Post-presidential life

Ståhlberg did not seek re-election in 1925, finding his difficult term of office a great strain. He also believed that the right-wing and the monarchists would become more reconciled to the republic if he stepped down. According to the longtime late Agrarian and Centrist politician Johannes Virolainen, he believed that the incumbent president was too much favoured over the other candidates while standing for re-election. He was offered the post of Chancellor of the University of Helsinki, but declined it, instead becoming a member of the government's Law Drafting Committee. He also served as a National Progressive member of Parliament again, as a member for the Uusimaa constituency from 1930 to 1933.

In 1930, activists from the right-wing Lapua Movement kidnapped him and his wife, attempting to send them to the

Ståhlberg did not seek re-election in 1925, finding his difficult term of office a great strain. He also believed that the right-wing and the monarchists would become more reconciled to the republic if he stepped down. According to the longtime late Agrarian and Centrist politician Johannes Virolainen, he believed that the incumbent president was too much favoured over the other candidates while standing for re-election. He was offered the post of Chancellor of the University of Helsinki, but declined it, instead becoming a member of the government's Law Drafting Committee. He also served as a National Progressive member of Parliament again, as a member for the Uusimaa constituency from 1930 to 1933.

In 1930, activists from the right-wing Lapua Movement kidnapped him and his wife, attempting to send them to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, but the incident merely hastened the Lapua Movement's demise.

Ståhlberg was a National Progressive Party candidate in the 1931 Presidential election, eventually losing to Pehr Evind Svinhufvud

Pehr Evind Svinhufvud af Qvalstad (; 15 December 1861 – 29 February 1944) was the third president of Finland from 1931 to 1937. Serving as a lawyer, judge, and politician in the Russian Grand Duchy of Finland, he played a major role in the ...

by only two votes in the third ballot. He was also a candidate in the 1937 election, eventually finishing third.

In 1946, Ståhlberg retired and became the legal adviser of President J. K. Paasikivi

Juho Kusti Paasikivi (; 27 November 1870 – 14 December 1956) was the seventh president of Finland (1946–1956). Representing the Finnish Party until its dissolution in 1918 and then the National Coalition Party, he also served as Prime Minister ...

. Paasikivi often consulted Ståhlberg; for example, under the 1950 presidential election an emergency plan was planned to extend Paasikivi's term in parliament as president, which Ståhlberg condemned angrily in his letter to Paasikivi:Their last discussion occurred less than two weeks before Ståhlberg died. He died in 1952, and was buried in Helsinki's Hietaniemi cemetery with full honours.

Among Finnish Presidents, Ståhlberg has retained a remarkably impeccable reputation. He is generally regarded as a moral and

principled defender of democracy and of the rule of law, and as the father of the Finnish Constitution. His decision to voluntarily

give up the presidency is also generally speaking admired as a sign that he was not a power-hungry career politician.see, for example, "The Republic's Presidents 1919-1931" / Tasavallan presidentit 1919-1931, published in Finland in 1993-94

Honours

Awards and decorations

* : Grand Cross of theOrder of the White Rose

The Order of the White Rose of Finland ( fi, Suomen Valkoisen Ruusun ritarikunta; sv, Finlands Vita Ros’ orden) is one of three official orders in Finland, along with the Order of the Cross of Liberty, and the Order of the Lion of Finland. ...

(Finland)

* : Grand Cross of the Order of the Cross of Liberty

* : Cross of Liberty (Estonia)

* : Order of the Three Stars

References

External links

*K. J. Ståhlberg

in The Presidents of Finland * {{DEFAULTSORT:Stahlberg, Kaarlo Juho 1865 births 1952 deaths Academic personnel of the University of Helsinki People from Suomussalmi People from Oulu Province (Grand Duchy of Finland) Finnish Lutherans Young Finnish Party politicians National Progressive Party (Finland) politicians Presidents of Finland Finnish senators Speakers of the Parliament of Finland Members of the Parliament of Finland (1908–09) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1909–10) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1913–16) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1916–17) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1917–19) Members of the Parliament of Finland (1930–33) Kidnapped politicians People of the Finnish Civil War (White side) Finnish legal scholars Grand Crosses of the Order of the Cross of Liberty Liberalism Burials at Hietaniemi Cemetery University of Helsinki alumni