Junimea on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

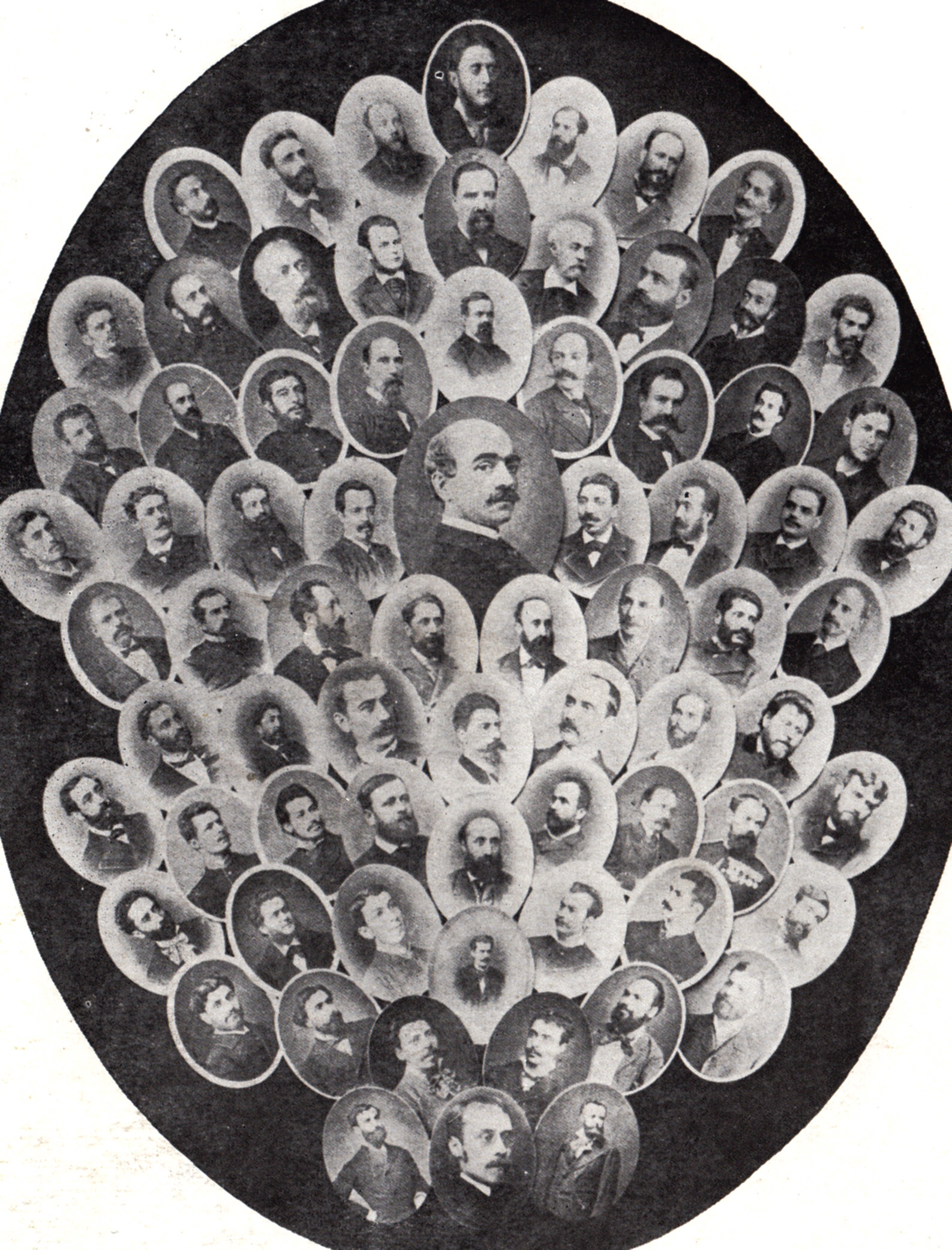

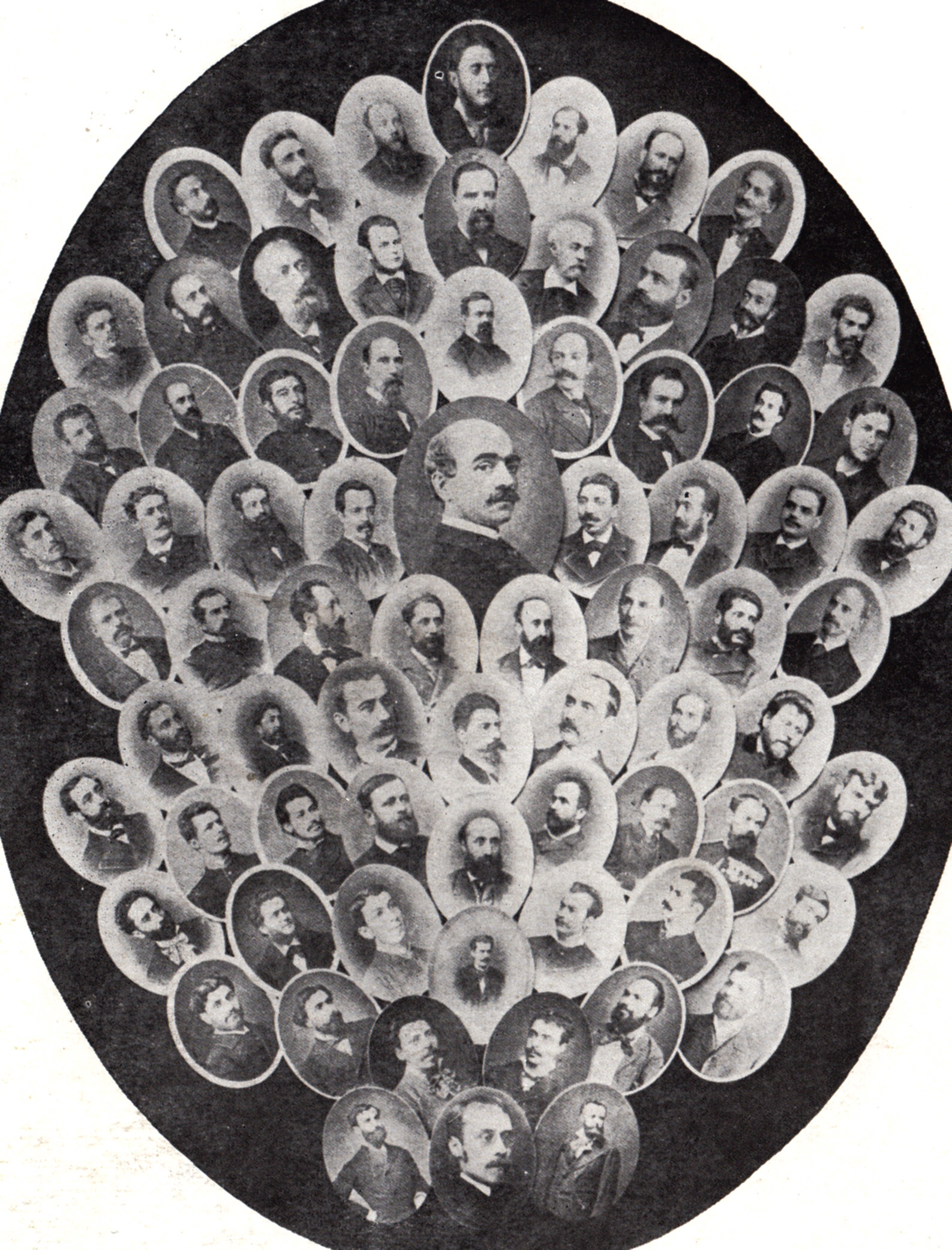

''Junimea'' was a

In 1863, four years after the union of

In 1863, four years after the union of

The earliest literary gathering was one year after ''Junimeas founding, in 1864, when members gathered to hear a translation of '' Macbeth''. Soon afterwards, it became common that they would meet each Sunday in order to discuss the problems of the day and review the newest literary works. Also, there were annual lectures on broad themes, such as ''Psychological Researches'' (1868 and 1869), ''Man and Nature'' (1873) or ''The Germans'' (1875). Their audience was formed of the Iaşi intellectuals, students, lawyers, professors, government officials, etc.

In 1867 Junimea started publishing its own literary review, '' Convorbiri Literare''. It was to become one of the most important publications in the history of

The earliest literary gathering was one year after ''Junimeas founding, in 1864, when members gathered to hear a translation of '' Macbeth''. Soon afterwards, it became common that they would meet each Sunday in order to discuss the problems of the day and review the newest literary works. Also, there were annual lectures on broad themes, such as ''Psychological Researches'' (1868 and 1869), ''Man and Nature'' (1873) or ''The Germans'' (1875). Their audience was formed of the Iaşi intellectuals, students, lawyers, professors, government officials, etc.

In 1867 Junimea started publishing its own literary review, '' Convorbiri Literare''. It was to become one of the most important publications in the history of

In 1885, the society moved to

In 1885, the society moved to

''Spiritul critic în cultura românească''

("Selective Attitudes in Romanian Culture"), 1908

''Un junimist patruzecioptist: Vasile Alecsandri''

("An 1848 Generation Junimist: Vasile Alecsandri")

''Evoluţia spiritului critic – Deosebirile dintre vechea şcoală critică moldovenească şi "Junimea"''

("The Evolution of Selective Attitudes – The Differences Between the Old School of Criticism and ''Junimea''") * Titu Maiorescu

''În contra direcţiei de astăzi în cultura română''

("Against the Contemporary Direction in Romanian Culture", 1868) an

''Direcţia nouă în poezia şi proza română''

("The New Direction in Romanian Poetry and Prose", 1872)

(an essay on Junimist attitudes and more recent developments)

Ovidiu Morar, "Intelectualii români şi 'chestia evreiască'"

("The Romanian Intellectuals and the 'Jewish Question'"), in '' Contemporanul'', 6(639)/June 2005 {{Romanian nationalism 1863 establishments in Romania Political parties disestablished in 1916 Culture in Iași Defunct political parties in Romania Kingdom of Romania 1916 disestablishments in Romania

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

n literary society

A literary society is a group of people interested in literature. In the modern sense, this refers to a society that wants to promote one genre of writing or a specific author. Modern literary societies typically promote research, publish newsle ...

founded in Iași in 1863, through the initiative of several foreign-educated personalities led by Titu Maiorescu, Petre P. Carp, Vasile Pogor, Theodor Rosetti

Theodor Rosetti (5 May 1837, Iași or Solești, Moldavia – 17 July 1923, Bucharest, Romania) was a Romanian writer, journalist and politician who served as Prime Minister of Romania

The prime minister of Romania ( ro, Prim-ministrul Ro ...

and Iacob Negruzzi. The foremost personality and mentor of the society was Maiorescu, who, through the means of scientific papers and essays, helped establish the basis of the modern Romanian culture. Junimea was the most influential intellectual and political association from Romania in the 19th century.

Beginnings

In 1863, four years after the union of

In 1863, four years after the union of Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and for ...

and Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and s ...

(''see: United Principalities

The United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia ( ro, Principatele Unite ale Moldovei și Țării Românești), commonly called United Principalities, was the personal union of the Principality of Moldavia and the Principality of Wallachia, ...

''), and after the moving of the capital to Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

, five enthusiastic young people who had just returned from their studies abroad created in Iaşi a society which wanted to stimulate the cultural life in the city. They chose the name "''Junimea''", a slightly antiquated Romanian word for "Youth".

It is notable that four of the founders were part of the Romanian elite, the boyar class (Theodor Rosetti

Theodor Rosetti (5 May 1837, Iași or Solești, Moldavia – 17 July 1923, Bucharest, Romania) was a Romanian writer, journalist and politician who served as Prime Minister of Romania

The prime minister of Romania ( ro, Prim-ministrul Ro ...

was the brother-in-law of Domnitor

''Domnitor'' (Romanian pl. ''Domnitori'') was the official title of the ruler of Romania between 1862 and 1881. It was usually translated as "prince" in other languages and less often as "grand duke". Derived from the Romanian word "''domn''" ...

Alexandru Ioan Cuza

Alexandru Ioan Cuza (, or Alexandru Ioan I, also anglicised as Alexander John Cuza; 20 March 1820 – 15 May 1873) was the first ''domnitor'' (Ruler) of the Romanian Principalities through his double election as prince of Moldavia on 5 Janua ...

, Carp and Pogor were sons of boyars, and Iacob Negruzzi was the son of Costache Negruzzi), while only Titu Maiorescu was the only one born in a family of city elite, his father Ioan Maiorescu having been a professor at the National College in Craiova and a representative of the Wallachian government to the Frankfurt Parliament

The Frankfurt Parliament (german: Frankfurter Nationalversammlung, literally ''Frankfurt National Assembly'') was the first freely elected parliament for all German states, including the German-populated areas of Austria-Hungary, elected on 1 Ma ...

during the 1848 Wallachian Revolution

The Wallachian Revolution of 1848 was a Romanian liberal and nationalist uprising in the Principality of Wallachia. Part of the Revolutions of 1848, and closely connected with the unsuccessful revolt in the Principality of Moldavia, it sought ...

.

The literary association

Romanian literature

Romanian literature () is literature written by Romanian authors, although the term may also be used to refer to all literature written in the Romanian language.

History

The development of the Romanian literature took place in parallel with tha ...

and added a new, modern vision to the whole Romanian culture.

Between 1874 and 1885, when the society was frequented by the Romanian literature classics – Mihai Eminescu, Ion Creangă, Ion Luca Caragiale

Ion Luca Caragiale (; commonly referred to as I. L. Caragiale; According to his birth certificate, published and discussed by Constantin Popescu-Cadem in ''Manuscriptum'', Vol. VIII, Nr. 2, 1977, pp. 179-184 – 9 June 1912) was a Romanian playw ...

, Ioan Slavici

Ioan Slavici (; 18 January 1848 – 17 August 1925) was a Romanians, Romanian writer and journalist from Hungary, later from Romania.

He made his debut in ''Convorbiri literare'' ("Literary Conversations") (1871), with the comedy ''Fata de biră ...

– and many other important cultural personalities, it occupied the central spot of cultural life in Romania.

Theory

"Forms without substance"

After the Treaty of Adrianople of 1829, the Danubian Principalities (Moldavia and Wallachia) were allowed to engage in trade with other countries than those under Ottoman rule and with this came a great opening toward the European economy and culture (''seeWesternization

Westernization (or Westernisation), also Europeanisation or occidentalization (from the ''Occident''), is a process whereby societies come under or adopt Western culture in areas such as industry, technology, science, education, politics, econo ...

''). However, the Junimists argued, through their theory of "''Forms Without Substance''" (''Teoria Formelor Fără Fond'') that Romanian culture and society were merely imitating Western culture

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

, rapidly adopting forms while disregarding the need to select and adapt them to the Romanian context – and thus "lacked a foundation". Maiorescu argued that, while it seemed Romania possessed all the institutions of a modern nation, all were, in fact, shallow elements of fashion:

Moreover, Maiorescu argued that Romania only had an appearance of a complex modern society, and in fact harbored only two social classes: peasants, which comprised up to 90% of Romanians, and the landlord

A landlord is the owner of a house, apartment, condominium, land, or real estate which is rented or leased to an individual or business, who is called a tenant (also a ''lessee'' or ''renter''). When a juristic person is in this position, t ...

s. He denied the existence of a Romanian bourgeoisie, and presented Romanian society as one still fundamentally patriarchal. The National Liberal Party (founded in 1875) was dubbed as useless since it had no class to represent. Also, socialism was thought to be the product of an advanced society in Western Europe, and argued to have yet no reason of existence in Romania, where the proletariat made up a small part of the population – ''Junimea'' saw socialism in the context of Romania as an "exotic plant", and Maiorescu engaged in a polemic with Marxist thinker Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea.

While this criticism was indeed similar to political conservatism, ''Junimeas purposes were actually connected with gradual modernization that was meant to lead to a Romanian culture and society able to sustain a dialogue with their European counterparts. Unlike the mainstream Conservative Party, which sought to best represent landowners, the politically active Junimists opposed excessive reliance on agriculture, and could even champion a peasant ethos

Ethos ( or ) is a Greek word meaning "character" that is used to describe the guiding beliefs or ideals that characterize a community, nation, or ideology; and the balance between caution, and passion. The Greeks also used this word to refer to ...

. Maiorescu wrote:

Influence

The cultural life in Romania was since the 1830s influenced by France, and ''Junimea'' brought a new wave of German influence, especiallyGerman philosophy

German philosophy, here taken to mean either (1) philosophy in the German language or (2) philosophy by Germans, has been extremely diverse, and central to both the analytic and continental traditions in philosophy for centuries, from Gottfried ...

, accommodating a new wave of Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

– while also advocating and ultimately introducing Realism into local literature. As a regular visitor of the Iaşi club, Vasile Alecsandri

Vasile Alecsandri (; 21 July 182122 August 1890) was a Romanian patriot, poet, dramatist, politician and diplomat. He was one of the key figures during the 1848 revolutions in Moldavia and Wallachia. He fought for the unification of the Romani ...

was one of the few literary figures to represent both ''Junimea'' and its French-influenced predecessors.

The society also encouraged an accurate use of the Romanian language

Romanian (obsolete spellings: Rumanian or Roumanian; autonym: ''limba română'' , or ''românește'', ) is the official and main language of Romania and the Republic of Moldova. As a minority language it is spoken by stable communities in ...

, and Maiorescu repeatedly argued for a common version of the rendition of words in Romanian, favoring a phonetic transcription

Phonetic transcription (also known as phonetic script or phonetic notation) is the visual representation of speech sounds (or ''phones'') by means of symbols. The most common type of phonetic transcription uses a phonetic alphabet, such as the I ...

over the several versions in circulation after the discarding of the Romanian Cyrillic alphabet

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language

Romanian (obsolete spellings: Rumanian or Roumanian; autonym: ''limba română'' , or ''românește ...

. Maiorescu entered a polemic with the main advocates of a spelling that was reflecting pure Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

etymology

Etymology ()The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p. 633 "Etymology /ˌɛtɪˈmɒlədʒi/ the study of the class in words and the way their meanings have changed throughout time". is the study of the history of the Phonological chan ...

rather than the spoken language, the Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

n group around August Treboniu Laurian __NOTOC__

August Treboniu Laurian (; 17 July 1810 – 25 February 1881) was a Transylvanian Romanian politician, historian and linguist. He was born in the village of Hochfeld, Principality of Transylvania, Austrian Empire (today Fofeldea as par ...

:

At the same time, Maiorescu exercised influence through his attack on what he viewed as excessive innovative trends in writing and speaking Romanian:

Accordingly, ''Junimea'' heavily criticized Romanian Romantic nationalism for condoning excesses (especially in the problematic theses connected to the origin of Romanians). In the words of Maiorescu:

Using the same logic, ''Junimea'' (and especially Carp) entered a polemic with the National-Liberal historian Bogdan Petriceicu-Hasdeu over the latter's version of Dacian Protochronism

Dacianism is a Romanian term describing the tendency to ascribe, largely relying on questionable data and subjective interpretation, an idealized past to the country as a whole. While particularly prevalent during the regime of Nicolae Ceaușescu ...

.

The society encouraged a move towards profession

A profession is a field of work that has been successfully ''professionalized''. It can be defined as a disciplined group of individuals, '' professionals'', who adhere to ethical standards and who hold themselves out as, and are accepted by ...

alism in the writing of history, as well as intensified research; Maiorescu, who served as Minister of Education in several late-19th century cabinets, supported the creation of new opportunities in the field (including the granting of scholarships, especially in areas that had previously been neglected – amounting to the creation of one of the most influential Romanian generation of historians, that of Nicolae Iorga

Nicolae Iorga (; sometimes Neculai Iorga, Nicolas Jorga, Nicolai Jorga or Nicola Jorga, born Nicu N. Iorga;Iova, p. xxvii. 17 January 1871 – 27 November 1940) was a Romanian historian, politician, literary critic, memoirist, Albanologist, poet ...

, Dimitrie Onciul

Dimitrie Onciul (26 October / 7 November 1856 – 20 March 1923) was a Romanian historian. He was a member of the Romanian Academy and its president from 1920 until his death in 1923.

Biography

Onciul was born in Straja, at the time in the D ...

, and Ioan Bogdan Ioan Bogdan may refer to:

* Ioan Bogdan (historian) (1864–1919), Romanian historian and philologist

* Ioan Bogdan (footballer) (born 1956), Romanian footballer

See also

* Ion Bogdan (1915–1992), Romanian footballer and manager

* Ioan

* Bog ...

).

Although ''Junimea'' never imposed a single view on the matter, some of its prominent figures (Maiorescu, Carp, and ''Junimea'' associate Ion Luca Caragiale

Ion Luca Caragiale (; commonly referred to as I. L. Caragiale; According to his birth certificate, published and discussed by Constantin Popescu-Cadem in ''Manuscriptum'', Vol. VIII, Nr. 2, 1977, pp. 179-184 – 9 June 1912) was a Romanian playw ...

) notoriously opposed the prevalent anti-Jewish sentiment of the political establishment (while the initially Junimist intellectuals A. C. Cuza, A. D. Xenopol, and Ioan Slavici

Ioan Slavici (; 18 January 1848 – 17 August 1925) was a Romanians, Romanian writer and journalist from Hungary, later from Romania.

He made his debut in ''Convorbiri literare'' ("Literary Conversations") (1871), with the comedy ''Fata de biră ...

became well-known anti-semites

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

).

Moving to Bucharest

In 1885, the society moved to

In 1885, the society moved to Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

, and, through his University of Bucharest

The University of Bucharest ( ro, Universitatea din București), commonly known after its abbreviation UB in Romania, is a public university founded in its current form on by a decree of Prince Alexandru Ioan Cuza to convert the former Princel ...

professorship, Titu Maiorescu contributed to the creation of a new ''Junimist'' generation. However, ''Junimea'' ceased to dominate the intellectual life of Romania.

This roughly coincided with the partial transformation of prominent Junimists into politicians, after leaders such as Maiorescu and Carp joined the Conservative Party. Initially a separate wing with a moderately conservative political agenda (and, as the ''Partidul Constituţional'', "Constitutional Party", an independent political group between 1891 and 1907), ''Junimea'' representatives moved to the Party's forefront in the first years of the 20th century – both Carp and Maiorescu led the Conservatives in the 1910s.

Its cultural interests moved to historical research, philosophy (the theory of Positivism), as well as the two greatest political problems – the peasant question (''see the 1907 Romanian Peasants' Revolt''), and the issue of ethnic Romanians in Transylvania (a region which was part of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

). It ceased to exist around 1916, after becoming engulfed in the conflict over Romania's participation in World War I; leading Junimists (Carp first and foremost) had supported continuing Romania's alliance with the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

, and clashed over the issue with pro-French and anti-Austrian politicians.

Criticism of ''Junimeas guidelines

The first major review of Junimism came with the rise of Romanian populism (''Poporanism''), which partly shared the group's weariness in the face of rapid development, but relied instead on distinguishing and increasing the role of peasants as the root of Romanian culture. The populistGarabet Ibrăileanu

Garabet Ibrăileanu (; May 23, 1871 – March 11, 1936) was a Romanian- Armenian literary critic and theorist, writer, translator, sociologist, University of Iași professor (1908–1934), and, together with Paul Bujor and Constantin Stere, fo ...

argued that ''Junimeas conservatism was the result of a conjectural alliance between low and high Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and for ...

n boyars

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Kievan Rus', Bulgaria, Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia, and later Romania, Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. Boyars wer ...

against a Liberal-encouraged bourgeoisie, one reflected in the "''pessimism

Pessimism is a negative mental attitude in which an undesirable outcome is anticipated from a given situation. Pessimists tend to focus on the negatives of life in general. A common question asked to test for pessimism is " Is the glass half emp ...

of the Eminescu generation''".Ibrăileanu, ''Deosebirile dintre vechea şcoală critică moldovenească şi "Junimea"'' He invested in the image of low boyars, the Romanticist

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

agents of the 1848 Moldavian revolution

The Moldavian Revolution of 1848 is the name used for the unsuccessful Romanian liberal and Romantic nationalist movement inspired by the Revolutions of 1848 in the principality of Moldavia. Initially seeking accommodation within the political f ...

, as a tradition which, if partly blended into ''Junimea'', had kept a separate voice the literary society itself, and had more in common with ''Poporanism'' than Maiorescu's moderate conservatism:

The officially sanctioned criticism of ''Junimea'' during the Communist regime in Romania found its voice with George Călinescu, in his late work, the Communist-inspired ''Compendium

A compendium (plural: compendia or compendiums) is a comprehensive collection of information and analysis pertaining to a body of knowledge. A compendium may concisely summarize a larger work. In most cases, the body of knowledge will concern a sp ...

'' of his earlier ''Istoria literaturii române'' ("The History of Romanian Literature"). While arguing that ''Junimea'' had created a bridge between peasants and boyars, Călinescu criticised Maiorescu's strict commitment to ''art for art's sake

Art for art's sake—the usual English rendering of ''l'art pour l'art'' (), a French slogan from the latter part of the 19th century—is a phrase that expresses the philosophy that the intrinsic value of art, and the only 'true' art, is divorce ...

'' and the ideas of Arthur Schopenhauer, as signs of rigidity.Călinescu, ''Compendiu, XII. Titu Maiorescu'' He downplayed ''Junimeas literature, arguing that many Junimists had not reached their own goals (for example, he rejected Carp's criticism of Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu

Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu ( 26 February 1838 – ) was a Romanian writer and philologist, who pioneered many branches of Romanian philology and history.

Life

He was born Tadeu Hâjdeu in Cristineștii Hotinului (now Kerstentsi in Chernivtsi ...

and others as "''little and unprofessional''"),Călinescu, ''Compendiu, XII. Filologi, istorici, filozofi'' but looked favorably upon the major figures connected with the society ( Eminescu, Caragiale, Creangă etc.) and secondary Junimists such as the materialist philosopher Vasile Conta.

Notes

References

* George Călinescu, ''Istoria literaturii române. Compendiu'' ("The History of Romanian Literature. Compendium"), Editura Minerva, 1983 (Chapter XII, "Junimea") * Keith Hitchins, ''Rumania : 1866–1947'', Oxford History of Modern Europe,Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, 1994

* Garabet Ibrăileanu

Garabet Ibrăileanu (; May 23, 1871 – March 11, 1936) was a Romanian- Armenian literary critic and theorist, writer, translator, sociologist, University of Iași professor (1908–1934), and, together with Paul Bujor and Constantin Stere, fo ...

''Spiritul critic în cultura românească''

("Selective Attitudes in Romanian Culture"), 1908

''Un junimist patruzecioptist: Vasile Alecsandri''

("An 1848 Generation Junimist: Vasile Alecsandri")

''Evoluţia spiritului critic – Deosebirile dintre vechea şcoală critică moldovenească şi "Junimea"''

("The Evolution of Selective Attitudes – The Differences Between the Old School of Criticism and ''Junimea''") * Titu Maiorescu

''În contra direcţiei de astăzi în cultura română''

("Against the Contemporary Direction in Romanian Culture", 1868) an

''Direcţia nouă în poezia şi proza română''

("The New Direction in Romanian Poetry and Prose", 1872)

External links

(an essay on Junimist attitudes and more recent developments)

Ovidiu Morar, "Intelectualii români şi 'chestia evreiască'"

("The Romanian Intellectuals and the 'Jewish Question'"), in '' Contemporanul'', 6(639)/June 2005 {{Romanian nationalism 1863 establishments in Romania Political parties disestablished in 1916 Culture in Iași Defunct political parties in Romania Kingdom of Romania 1916 disestablishments in Romania