June 1946 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The following events occurred in June 1946:

The following events occurred in June 1946:

*In violation of the

*In violation of the

*By a 6–1 vote, the United States Supreme Court ruled in ''Morgan v. Virginia'' that a Virginia law, requiring

*By a 6–1 vote, the United States Supreme Court ruled in ''Morgan v. Virginia'' that a Virginia law, requiring

*

*

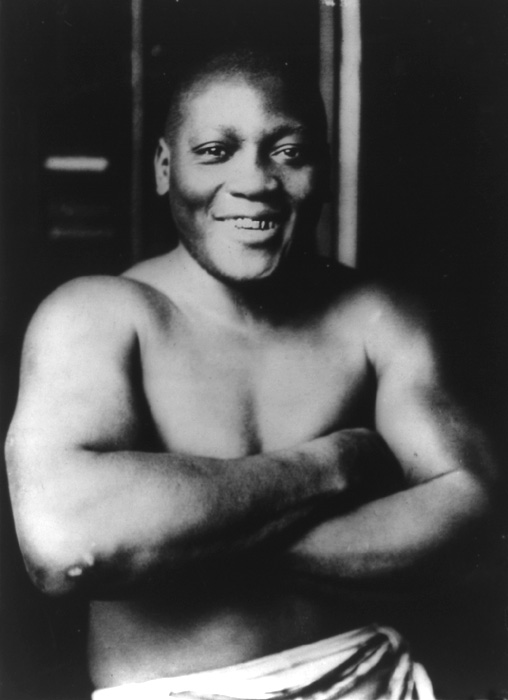

* Jack Johnson, the world heavyweight boxing champion from 1908 to 1915, and the first African-American to win that title, was killed in an automobile accident. In 1910, Johnson had defended his title in what was called then "The Fight of the Century", matching him against "The Great White Hope", former champion Jim Jeffries. Johnson had been driving from Texas to New York when his car crashed into a light pole near

* Jack Johnson, the world heavyweight boxing champion from 1908 to 1915, and the first African-American to win that title, was killed in an automobile accident. In 1910, Johnson had defended his title in what was called then "The Fight of the Century", matching him against "The Great White Hope", former champion Jim Jeffries. Johnson had been driving from Texas to New York when his car crashed into a light pole near

*The

*The

*An agreement to withdraw all Allied occupation forces from Italy, over a 90-day period, was approved in Paris by the representatives of the "Big Four" powers (France, the

*An agreement to withdraw all Allied occupation forces from Italy, over a 90-day period, was approved in Paris by the representatives of the "Big Four" powers (France, the

*U.S. Senator Theodore G. Bilbo of

*U.S. Senator Theodore G. Bilbo of

The following events occurred in June 1946:

The following events occurred in June 1946:

June 1, 1946 (Saturday)

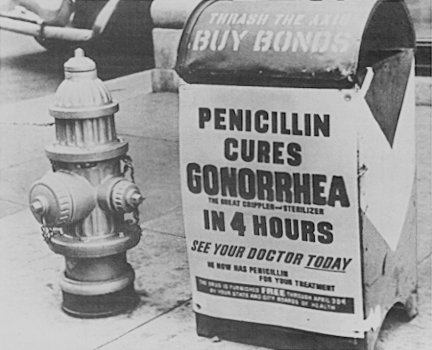

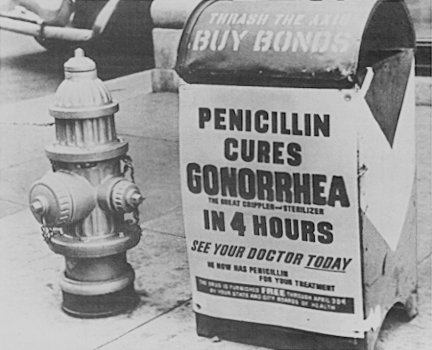

* Penicillin first went on sale to the general public in the United Kingdom. The antibiotic had been made available at pharmacies in the United States beginning March 15, 1945. *Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University's "Marching 100" was founded by the late William P. Foster *By a 61–20 vote, the U.S. Senate granted President Truman emergency powers to end strikes. The bill had passed the House the previous week.Ho–Sainteny agreement

The Ho–Sainteny agreement, officially the ''Accord Between France and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam'', known in Vietnamese as Hiệp định sơ bộ Pháp-Việt, was an agreement made on March 6, 1946, between Ho Chi Minh, President of t ...

of March 6

Events Pre-1600

* 12 BCE – The Roman emperor Augustus is named Pontifex Maximus, incorporating the position into that of the emperor.

* 632 – The Farewell Sermon (Khutbah, Khutbatul Wada') of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

* 845 & ...

, French High Commissioner d'Argenlieu recognized an " Autonomous Republic of Cochin-China" in French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

, predecessor state of South Vietnam. Located in the southern part of what is now Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

, with a capital at Saigon, the Republic's first head of government was Nguyen Van Thinh, overseen by French administrator Jean Henri Cedile. The announcement followed the creation, in March, of the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; vi, Việt Nam Dân chủ Cộng hòa), was a socialist state supported by the Soviet Union (USSR) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Southeast Asia that existed f ...

(later known as North Vietnam) in Hanoi

Hanoi or Ha Noi ( or ; vi, Hà Nội ) is the capital and second-largest city of Vietnam. It covers an area of . It consists of 12 urban districts, one district-leveled town and 17 rural districts. Located within the Red River Delta, Hanoi is ...

.

*Died:

** Ion Antonescu, prime minister and "Conducator" (Leader) of Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

during World War II was executed after being found guilty of betraying the Romanian people to German occupiers.

**Leo Slezak

Leo Slezak (; 18 August 1873 – 1 June 1946) was a Moravian dramatic tenor. He was associated in particular with Austrian opera as well as the title role in Verdi's '' Otello''. He is the father of actors Walter Slezak and Margarete Slezak a ...

, 72, German opera tenor

June 2, 1946 (Sunday)

*By a vote of 12,718,641 to 10,718,502 in the Italian institutional referendum, themonarchy

A monarchy is a government#Forms, form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The legitimacy (political)#monarchy, political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restric ...

in Italy was abolished, ending the brief reign of King Umberto II, who would go into exile. The simultaneous general election, the first since the end of World War II and the Fascist Party dictatorship of Benito Mussolini, and also the first in which women were allowed to vote, determined representation for the Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

. The Christian Democracy party, led by Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi

Alcide Amedeo Francesco De Gasperi (; 3 April 1881 – 19 August 1954) was an Italian politician who founded the Christian Democracy party and served as prime minister of Italy in eight successive coalition governments from 1945 to 1953.

De Gas ...

, won 207 out of 556 seats and formed a coalition government with the Socialists (115) and Communist (104) parties. The Christian Democracy party would lead the Italian government continuously until 1981.

*In the French Parliamentary election, the French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (french: Parti communiste français, ''PCF'' ; ) is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its MEPs sit in the European Un ...

(PCF) lost its plurality (from 159 to 153), and the Popular Republican Movement

The Popular Republican Movement (french: Mouvement Républicain Populaire, MRP) was a Christian-democratic political party in France during the Fourth Republic. Its base was the Catholic vote and its leaders included Georges Bidault, Robert Sc ...

(MRP) gained 16 seats (from 150 to 166). The Socialist Party dropped from 146 to 128. With 586 seats in Parliament, no party had a majority.

*Born: Peter Sutcliffe

Peter William Sutcliffe (2 June 1946 – 13 November 2020) was an English serial killer who was dubbed the Yorkshire Ripper (an allusion to Jack the Ripper) by the press. Sutcliffe was convicted of murdering 13 women and attempting t ...

, English serial killer known as the "Yorkshire Ripper"; in Bingley

Bingley is a market town and civil parish in the metropolitan borough of the City of Bradford, West Yorkshire, England, on the River Aire and the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, which had a population of 18,294 at the 2011 Census.

Bingley railwa ...

, West Yorkshire

West Yorkshire is a metropolitan and ceremonial county in the Yorkshire and Humber Region of England. It is an inland and upland county having eastward-draining valleys while taking in the moors of the Pennines. West Yorkshire came into exi ...

(d. 2020)

*Died: Carrie Ingalls (Caroline Ingalls Swanzey), 75, American newspaper typesetter known from bestselling ''Little House on the Prairie

The ''Little House on the Prairie'' books is a series of American children's novels written by Laura Ingalls Wilder (b. Laura Elizabeth Ingalls). The stories are based on her childhood and adolescence in the American Midwest (Wisconsin, Kansas, ...

'' books written by her older sister, Laura Ingalls Wilder

Laura Elizabeth Ingalls Wilder (February 7, 1867 – February 10, 1957) was an American writer, mostly known for the '' Little House on the Prairie'' series of children's books, published between 1932 and 1943, which were based on her childhood ...

and the subsequent television series.

June 3, 1946 (Monday)

*By a 6–1 vote, the United States Supreme Court ruled in ''Morgan v. Virginia'' that a Virginia law, requiring

*By a 6–1 vote, the United States Supreme Court ruled in ''Morgan v. Virginia'' that a Virginia law, requiring segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

of white and African-American bus passengers, was illegal for interstate travel. The suit had been brought by Irene Morgan, who had refused to sit in the negro section of a bus traveling from Gloucester County, Virginia, to Baltimore, Maryland.

*Died:

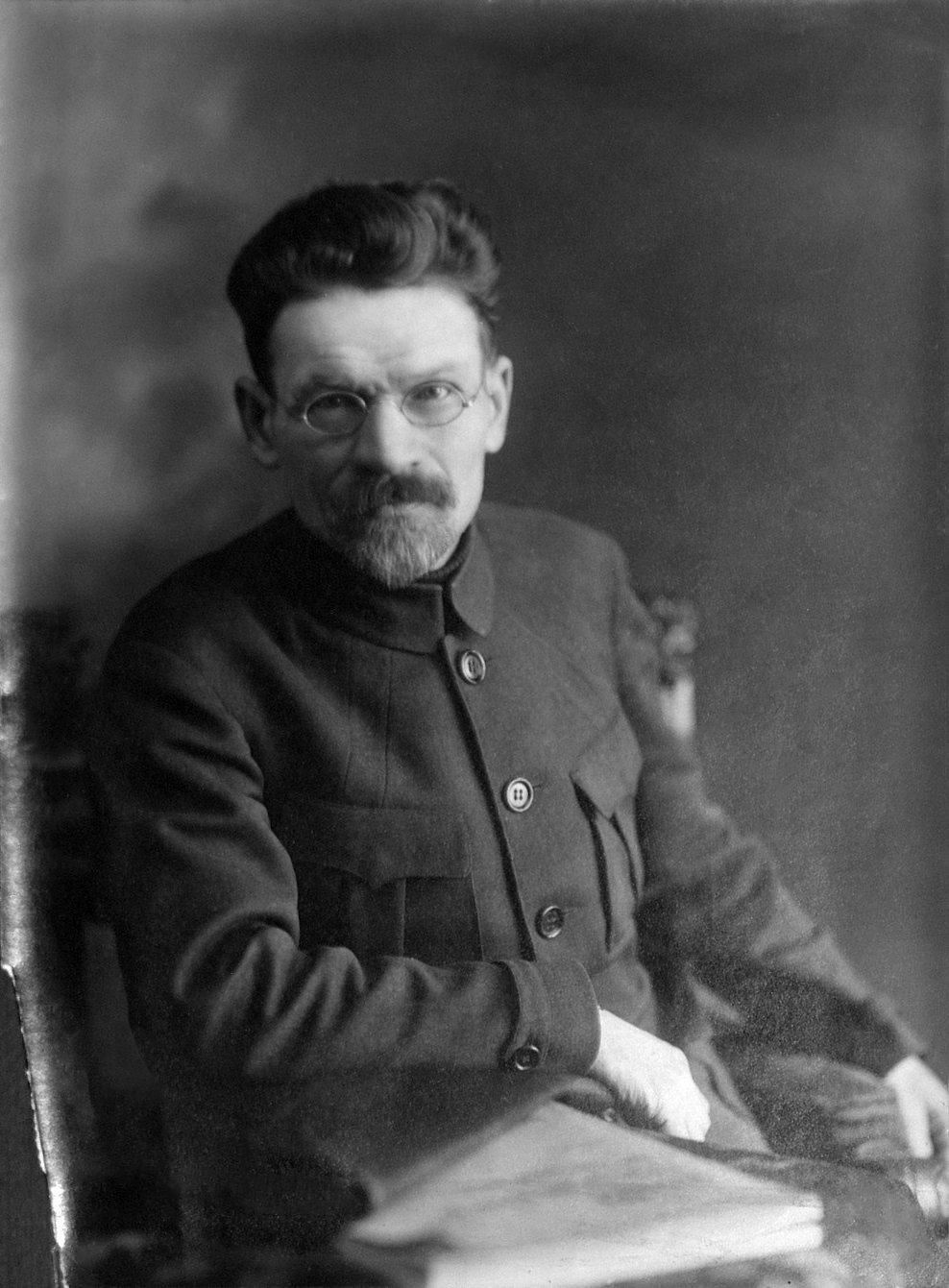

** Mikhail I. Kalinin, 70, former head of state of the U.S.S.R.

** Ch'en Kung-po, 54, founding member of Chinese Communist Party and collaborator, was executed

June 4, 1946 (Tuesday)

*TheUnited States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

recovered a treasure trove of jewelry and manuscripts that had been stolen by a group of American officers from the Friedrichshof Castle in Kronberg

Kronberg im Taunus is a town in the Hochtaunuskreis district, Hesse, Germany and part of the Frankfurt Rhein-Main urban area. Before 1866, it was in the Duchy of Nassau; in that year the whole Duchy was absorbed into Prussia. Kronberg lies at t ...

, Germany. Women's Army Corps

The Women's Army Corps (WAC) was the women's branch of the United States Army. It was created as an auxiliary unit, the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) on 15 May 1942 and converted to an active duty status in the Army of the United States ...

Captain Kathleen Nash Durant had hidden part of the loot at her sister's home in Hudson, Wisconsin

Hudson is a city in St. Croix County, Wisconsin, United States. As of the 2010 United States census, its population was 12,719. It is part of the Minneapolis–St. Paul Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA). The village of North Hudson is direct ...

, and her husband, Colonel Jack W. Durant, had hidden hundreds of diamonds and other gems in a locker at the Illinois Central railway station in Chicago.

*The National School Lunch Act was signed into law by U.S. President Harry S. Truman, permanently establishing federal financial support for free or low-cost meals for schoolchildren.

*The largest solar prominence

A prominence, sometimes referred to as a filament, is a large plasma and magnetic field structure extending outward from the Sun's surface, often in a loop shape. Prominences are anchored to the Sun's surface in the photosphere, and extend ou ...

observed up to that time occurred. The prominence, extending above the surface of the Sun, was seen from the observatory at Climax, Colorado, by astronomer Walter Orr Roberts

Walter Orr Roberts (August 20, 1915 – March 12, 1990) was an American astronomer and atmospheric physicist, as well as an educator, philanthropist, and builder. He founded the National Center for Atmospheric Research and took a personal research ...

. The prominence had been measured at only an hour earlier. At its height, the prominence was nearly as long as the Sun's diameter; in a few more hours, it disappeared completely."

June 5, 1946 (Wednesday)

*A fire at theLa Salle Hotel

The La Salle Hotel was a historic hotel that was located on the northwest corner of La Salle Street and Madison Street in the Chicago Loop community area of Chicago, Illinois, United States. It was situated to the southwest of Chicago City Ha ...

in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

killed 57 people. When the blaze broke out at 12:20 am, there were 1,059 guests and 108 employees in the 20-story building. Firefighters were not called until 15 minutes after the flames were spotted, and by 12:35, the blaze had spread from the hotel's Silver Grill Cocktail Lounge throughout the lower floors. Most of the dead were guests on 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th floors of the twenty-story building. At least ten people jumped to their deaths.

*Died: George A. Hormel

George Albert Hormel (December 4, 1860 – June 5, 1946) was an American entrepreneur, he was the founder of Hormel, Hormel Foods Corporation (then known as George A. Hormel & Co.) in 1891. His ownership stake in the company made him one of the we ...

, 85, American multi-millionaire and founder of Hormel Foods

Hormel Foods Corporation is an American food processing company founded in 1891 in Austin, Minnesota, by George A. Hormel as George A. Hormel & Company. The company originally focused on the packaging and selling of ham, sausage and other pork ...

June 6, 1946 (Thursday)

*The Basketball Association of America was formed in New York City. The forerunner of the NBA, the BAA awarded 13 big-city franchises, of which three — the Boston Celtics, the New York Knicks and the Golden State Warriors (in 1946, the Philadelphia Warriors) — still exist. Other teams were in Chicago (Stags), Detroit (Falcons), Pittsburgh (Ironmen), Providence (Steamrollers), St. Louis (Bombers), Toronto (Huskies) and Washington (Capitols), while franchises in Buffalo and Indianapolis failed to play. *American Research and Development Corporation

American Research and Development Corporation (ARDC) was a venture capital and private equity firm founded in 1946 by Georges Doriot, Ralph Flanders, Merrill Griswold, and Karl Compton.

ARDC is credited with the first major venture capital ...

, the first venture capital

Venture capital (often abbreviated as VC) is a form of private equity financing that is provided by venture capital firms or funds to start-up company, startups, early-stage, and emerging companies that have been deemed to have high growth poten ...

firm, was incorporated in Massachusetts by Georges Doriot

Georges Frédéric Doriot (September 24, 1899 – June 1987) was a French-American known for his prolific careers in military, academics, business and education.

An émigré from France, Doriot became a professor of Industrial Management at Har ...

, Ralph Flanders

Ralph Edward Flanders (September 28, 1880 – February 19, 1970) was an American mechanical engineer, industrialist and politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Vermont. He grew up on subsistence farms in Vermont and R ...

, Karl Compton and Merrill Griswold.

*U.S. Treasury Secretary Fred M. Vinson was nominated by President Truman to be the new Chief Justice of the United States.

*Died: Gerhart Hauptmann

Gerhart Johann Robert Hauptmann (; 15 November 1862 – 6 June 1946) was a German dramatist and novelist. He is counted among the most important promoters of literary naturalism, though he integrated other styles into his work as well. He rece ...

, 83, German dramatist, winner of the 1912 Nobel Prize in Literature

June 7, 1946 (Friday)

*The BBC Television network went back on the air for the first time since it had abruptly halted broadcasting, in the middle of a Mickey Mouse cartoon, at noon onSeptember 1, 1939

"September 1, 1939" is a poem by W. H. Auden written on the outbreak of World War II. It was first published in ''The New Republic'' issue of 18 October 1939, and in book form in Auden's collection ''Another Time'' (1940).

Description

The po ...

, when World War II had begun. The first program shown when broadcasting resumed was the very same cartoon that had been halted almost seven years earlier.

*After setting a Friday evening deadline for walking out on strike two days earlier, the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball team voted to go ahead with their scheduled game against the New York Giants. On June 5, the players voted unanimously to walk off the job unless they were allowed to join the American Baseball Guild

The American Baseball Guild was a short-lived American trade union that attempted to organize Major League Baseball (MLB) players into a collective bargaining unit in 1946.

, a labor union. An unidentified player reported that the vote had been 20 to 17 against a walkout. The team went on to beat the Giants 10–5.

June 8, 1946 (Saturday)

*Thirteen months afterV-E Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945, marking the official end of World War II in Europe in the Easte ...

, the United Kingdom celebrated its victory in World War II with a program that featured "all the pomp and circumstance it had given up during the war" and that was witnessed by "nearly one fourth of England's people" Tens of thousands of uniformed marchers represented the Allied nations in a nine-mile-long procession, while the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

flew overhead.

*Born: Pearlette Louisy

Dame Calliopa Pearlette Louisy (born 8 June 1946) is a Saint Lucian academic, who served as governor-general of Saint Lucia from 19 September 1997, until her resignation on 31 December 2017. She is the first woman to hold the vice-regal office ...

, Governor-General of Saint Lucia

The governor-general of Saint Lucia is the representative of the Saint Lucian monarch, currently Charles III. The official residence of the governor-general is Government House.

The position of governor-general was established when Saint Luci ...

from 1997 to 2017; in Laborie

June 9, 1946 (Sunday)

*

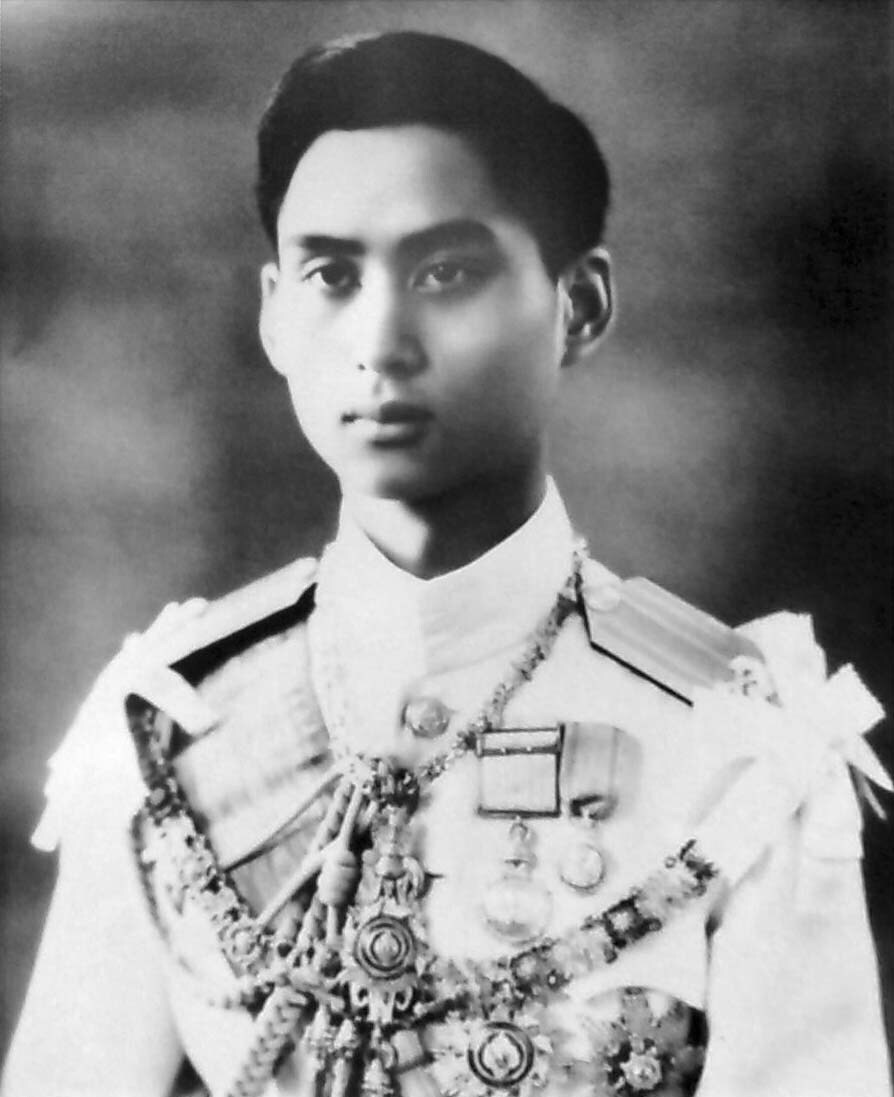

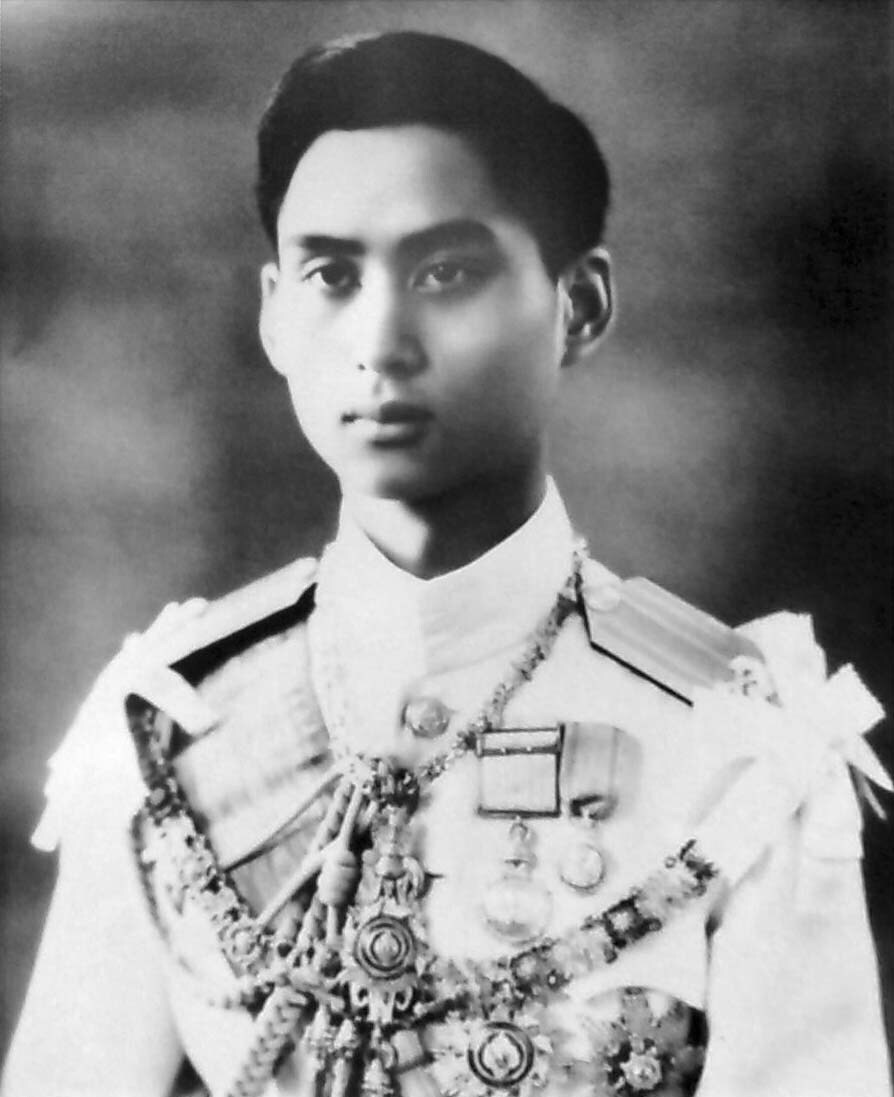

*Ananda Mahidol

Ananda Mahidol ( th, พระบาทสมเด็จพระปรเมนทรมหาอานันทมหิดล; ; 20 September 1925 – 9 June 1946), posthumous reigning title Phra Athamaramathibodin ( th, พระอั� ...

, the 20-year-old King of Thailand

The monarchy of Thailand (whose monarch is referred to as the king of Thailand; th, พระมหากษัตริย์ไทย, or historically, king of Siam; th, พระมหากษัตริย์สยาม) refers to the c ...

, was found in his bedroom dead, from a single gunshot to his forehead, and with his Colt .45 pistol next to him. He was succeeded by his teenaged brother, Bhumibol Adulyadej

Bhumibol Adulyadej ( th, ภูมิพลอดุลยเดช; ; ; (Sanskrit: ''bhūmi·bala atulya·teja'' - "might of the land, unparalleled brilliance"); 5 December 192713 October 2016), conferred with the title King Bhumibol the Great ...

, who became King Rama IX and ruled until his death in October 2016. Although the death was initially ruled an accidental shooting, and speculated by author Rayne Kruger

Charles Rayne Kruger (29 January 1922 – 21 December 2002) was a South African author and property developer.

Charles Rayne Kruger was born on 29 January 1922 in Queenstown, in the Eastern Cape, the son of an unmarried 17-year-old daughter o ...

in ''The Devil's Discus'' (Cassell, 1964) to have been a suicide, royal secretary Chaleo Pathumros and two others were executed in 1955 after being convicted of King Ananda's murder.

*A fire at the Canfield Hotel in Dubuque, Iowa

Dubuque (, ) is the county seat of Dubuque County, Iowa, United States, located along the Mississippi River. At the time of the 2020 census, the population of Dubuque was 59,667. The city lies at the junction of Iowa, Illinois, and Wisconsin, a r ...

, killed 16 people.

June 10, 1946 (Monday)

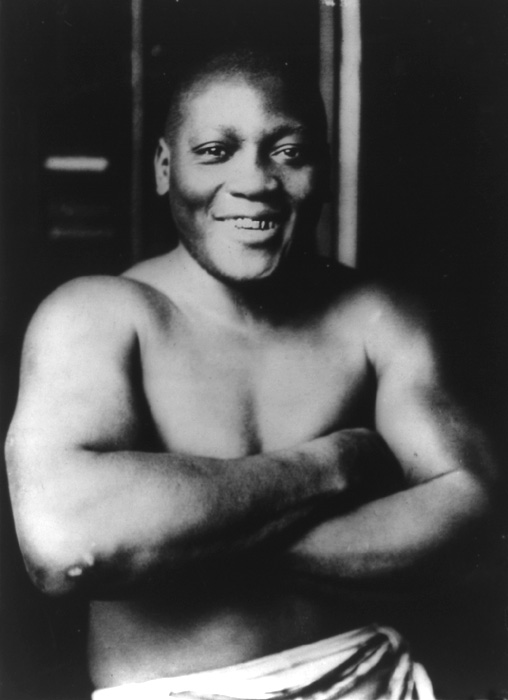

* Jack Johnson, the world heavyweight boxing champion from 1908 to 1915, and the first African-American to win that title, was killed in an automobile accident. In 1910, Johnson had defended his title in what was called then "The Fight of the Century", matching him against "The Great White Hope", former champion Jim Jeffries. Johnson had been driving from Texas to New York when his car crashed into a light pole near

* Jack Johnson, the world heavyweight boxing champion from 1908 to 1915, and the first African-American to win that title, was killed in an automobile accident. In 1910, Johnson had defended his title in what was called then "The Fight of the Century", matching him against "The Great White Hope", former champion Jim Jeffries. Johnson had been driving from Texas to New York when his car crashed into a light pole near Franklinton, North Carolina

Franklinton is a town in Franklin County, North Carolina, United States. The population was 2,456 at the 2020 census.

History

Franklinton, was established as Franklin Depot in 1839 on land owned by Shemuel Kearney (1791–1860), son of Crawford ...

.

June 11, 1946 (Tuesday)

*The Administrative Procedure Act, which governs the rulemaking and judicial functions of all United States government agencies, was signed into law. The law has been described as "the most important statute affecting the administration of justice in the federal field since the passage of the Judiciary Act of 1789".June 12, 1946 (Wednesday)

*After the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry had unanimously recommended that up to 100,000 European Jews be allowed to immigrate to Palestine, British Foreign SecretaryErnest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in the years 1922–194 ...

declared that the United Kingdom would reject the plan. Speaking at the annual conference of Britain's Labour Party, Bevin commented that the motive for American support for a Jewish state was "because they did not want too many of them in New York." Following the rejection of the proposal, Zionist leaders began a campaign of violence against the British government in the future state of Israel.

*Died: John H. Bankhead II, 73, U.S. Senator from Alabama since 1931

June 13, 1946 (Thursday)

*After a reign of 31 days, KingUmberto II of Italy

en, Albert Nicholas Thomas John Maria of Savoy

, house = Savoy

, father = Victor Emmanuel III of Italy

, mother = Princess Elena of Montenegro

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Racconigi, Piedmont, Kingdom of Italy

, ...

elected not to further contest the results of the June 2 referendum that abolished the monarchy, and flew into exile. Earlier in the day, Parliament had granted Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi

Alcide Amedeo Francesco De Gasperi (; 3 April 1881 – 19 August 1954) was an Italian politician who founded the Christian Democracy party and served as prime minister of Italy in eight successive coalition governments from 1945 to 1953.

De Gas ...

power to serve as the acting head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

until the election results could be certified.

*Died:

**Edward Bowes

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

, 72, American creator and host of radio program ''Major Bowes Amateur Hour

The ''Major Bowes Amateur Hour'' was an American radio talent show broadcast in the 1930s and 1940s, created and hosted by Edward Bowes (1874–1946). Selected performers from the program participated in touring vaudeville performances, under ...

''

** Charles Butterworth, 49, American film actor, in an automobile accident

**Jules Guérin

Jules Guérin (14 September 1860 – 10 February 1910) was a French journalist and anti-Semitic activist. He founded and led the Antisemitic League of France (), an organisation similar to the , and edited the French weekly (Paris, 1896–190 ...

, 79, American mural painter.

June 14, 1946 (Friday)

*As the United States representative to the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission, financier Bernard Baruch spoke at the UNAEC's temporary headquarters at New York's Hunter College, and presented the Baruch Plan, the American proposal for United Nations' control of all nuclear weapons. At the time, the United States was the only nation to have produced an atomic bomb. Baruch opened his remarks by saying, "We are here to make a choice between the quick and the dead.". Under the plan, the U.N.'s member nations would have agreed to not develop nuclear weapons and to allow inspections by the UNAEC to verify compliance, with punishments for violation of the agreement. No member of the U.N. Security Council would have been allowed to veto a resolution for enforcement. In return, the UNAEC would have assisted member nations in developing nuclear energy for peaceful uses. A week later, theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

made a counterproposal that would have delayed discussion of enforcement procedures until after weapons were destroyed. No agreement was ever reached, and the world's nations developed their own nuclear arsenals. One historian later offered the opinion that "the Baruch Plan was the nearest approach to a world government proposal ever offered by the United States",

*A total lunar eclipse

A lunar eclipse occurs when the Moon moves into the Earth's shadow. Such alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six months, during the full moon phase, when the Moon's orbital plane is closest to Ecliptic, the plane of t ...

, completely visible over South America, Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia, was seen rising over South America, Europe and Africa and setting over Asia and Australia took place.

*Born: Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

, President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

2017 to 2021, U.S. businessman and television personality; in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

*Died:

**John Logie Baird

John Logie Baird FRSE (; 13 August 188814 June 1946) was a Scottish inventor, electrical engineer, and innovator who demonstrated the world's first live working television system on 26 January 1926. He went on to invent the first publicly dem ...

, 57, Scottish inventor of television technology

**Jorge Ubico

Jorge Ubico Castañeda (10 November 1878 – 14 June 1946), nicknamed Number Five or also Central America's Napoleon, was a Guatemalan dictator. A general in the Guatemalan army, he was elected to the presidency in 1931, in an election where ...

, 67, Guatemalan dictator

June 15, 1946 (Saturday)

*The

*The Blue Angels

The Blue Angels is a flight demonstration squadron of the United States Navy.

, the aerial demonstration team for the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Marine Corps, made its very first performance, with four pilots under the leadership of Lt. Commander Butch Voris flying at an airshow at the Jacksonville Naval Air Station

Naval Air Station Jacksonville (NAS Jacksonville) is a large naval air station located approximately eight miles (13 km) south of the central business district of Jacksonville, Florida, United States., effective 2007-10-25

Location

NAS Jack ...

in Florida.

*In golf's U.S. Open, Byron Nelson

John Byron Nelson Jr. (February 4, 1912 – September 26, 2006) was an American professional golfer between 1935 and 1946, widely considered one of the greatest golfers of all time.

Nelson and two other legendary champions of the time, Ben Hoga ...

, Lloyd Mangrum

Lloyd Eugene Mangrum (August 1, 1914 – November 17, 1973) was an American professional golfer. He was known for his smooth swing and his relaxed demeanour on the course, which earned him the nickname "Mr. Icicle." Early life and family

Mangrum ...

and Vic Ghezzi

Victor J. Ghezzi (October 19, 1910 – May 30, 1976) was an American professional golfer. (Birth year sometimes listed as 1911 or 1912)

Born in Rumson, New Jersey, Ghezzi won 11 times on the PGA Tour, including one major title, the 1941 PGA Champi ...

finished 72 holes of golf in a three-way tie, each having 283, at the tournament in Cleveland. Nelson would have won outright, but his caddy had accidentally brushed his foot against the ball when Nelson's fans crowded the area, costing a penalty stroke. The next day, the three men tied again at 72 in an 18-hole playoff. In the second playoff, played during a violent thunderstorm, Mangrum — who had been wounded twice during the Battle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive, was the last major German offensive campaign on the Western Front during World War II. The battle lasted from 16 December 1944 to 28 January 1945, towards the end of the war in ...

finished at 72, a stroke ahead of Nelson and Ghezzi.

*Born: Demis Roussos

Artemios "Demis" Ventouris-Roussos ( ; el, Αρτέμιος "Ντέμης" Βεντούρης-Ρούσσος, ; 15 June 1946 – 25 January 2015) was a Greek singer, songwriter and musician. As a band member he is best remembered for his work in ...

, Greek singer; in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

(d. 2015)

June 16, 1946 (Sunday)

*The "Night of the Bridges

The Night of the Bridges (formally Operation Markolet) was a Haganah venture on the night of 16 to 17 June 1946 in the British Mandate of Palestine, as part of the Jewish insurgency in Palestine (1944–7). Its aim was to destroy eleven bridges l ...

" took place as agents of the Palmach, a strike force of the Zionist group Haganah, destroyed eleven highway and railway bridges on the night of June 16–17. Author Joseph Heller

Joseph Heller (May 1, 1923 – December 12, 1999) was an American author of novels, short stories, plays, and screenplays. His best-known work is the 1961 novel ''Catch-22'', a satire on war and bureaucracy, whose title has become a synonym for ...

commented later "Ten bridges connecting Palestine with the neighboring states were destroyed with no casualties. British occupying forces rounded many of the Haganah members in Operation Agatha

Operation Agatha (Saturday, June 29, 1946), sometimes called Black Sabbath ( he, השבת השחורה) or Black Saturday because it began on the Jewish sabbath, was a police and military operation conducted by the British authorities in Mandato ...

days later.

June 17, 1946 (Monday)

*Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

achieved independence when the Treaty of London officially came into effect.

*Mobile Telephone Service

The Mobile Telephone Service (MTS) was a pre- cellular VHF radio system that linked to the Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN). MTS was the radiotelephone equivalent of land dial phone service.

The Mobile Telephone Service was one of the ear ...

(MTS), the first "car phone" service in the United States, was introduced by AT&T

AT&T Inc. is an American multinational telecommunications holding company headquartered at Whitacre Tower in Downtown Dallas, Texas. It is the world's largest telecommunications company by revenue and the third largest provider of mobile te ...

in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, working in conjunction with Southwestern Bell

Southwestern Bell Telephone Company is a wholly owned subsidiary of AT&T. It does business as other d.b.a. names in its operating region, which includes Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas, and portions of Illinois.

The company is cu ...

. With the aid of a radio tower that transmitted on 120 kHz and could handle only one call at a time, customers could place and receive phone calls in their automobiles. The service was then instituted in other American cities. To call someone on an MTS phone, a person would first call an AT&T operator, who would then send a signal to the designated MTS telephone number. Calls from an auto were also operator assisted.

* A tornado swept through Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

and then across the U.S.-Canada border into Windsor, Ontario

Windsor is a city in southwestern Ontario, Canada, on the south bank of the Detroit River directly across from Detroit, Michigan, United States. Geographically located within but administratively independent of Essex County, it is the southe ...

, killing 17 people.

*Born: Marcy Kaptur, U.S. Representative (D-Ohio) since 1983; in Toledo, Ohio

Toledo ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Lucas County, Ohio, United States. A major Midwestern United States port city, Toledo is the fourth-most populous city in the state of Ohio, after Columbus, Cleveland, and Cincinnati, and according ...

June 18, 1946 (Tuesday)

*InGoa

Goa () is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is located between the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north and Karnataka to the ...

, at that time part of the colony of Portuguese India, Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia began the passive resistance movement against the Portuguese administration to become part of an independent India. The resistance continued for 15 years until Goa and other Portuguese colonies were invaded by the Indian army and annexed. Goa became India's 25th state in 1987.

*Born:

**Russell Ash

Russell Ash (18 June 1946 – 21 June 2010) was the British author of the '' Top 10 of Everything'' series of books, as well as ''Great Wonders of the World'', ''Incredible Comparisons'' and many other reference, art and humour titles, most nota ...

, British children's author known for '' The Top 10 of Everything'' and its sequels; in Surrey (d. 2010)

**Bruiser Brody

Frank Donald Goodish (June 18, 1946 – July 17, 1988) was an American professional wrestler who earned his greatest fame under the ring name Bruiser Brody. He also worked as King Kong Brody, The Masked Marauder, and Red River Jack. Over the years ...

(ring name for as Frank Goodish), American professional wrestler; in Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

(d. 1988)

June 19, 1946 (Wednesday)

* Georges Bidault was elected as the ProvisionalPresident of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency i ...

by the National Assembly, with 389 votes out of the 586 possible. Communist legislators refused to participate in the vote.

*A rematch between world heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis and challenger Billy Conn

William David Conn (October 8, 1917 – May 29, 1993) was an Irish American professional boxer and Light Heavyweight Champion famed for his fights with Joe Louis. He had a professional boxing record of 63 wins, 11 losses and 1 draw, with 14 wins ...

attracted 45,266 fight fans to Yankee Stadium

Yankee Stadium is a baseball stadium located in the Bronx, New York City. It is the home field of the New York Yankees of Major League Baseball, and New York City FC of Major League Soccer.

Opened in April 2009, the stadium replaced the orig ...

, while another 140,000 viewed the fight on the NBC television network (including broadcasts in theaters). After a lackluster fight, Louis knocked Conn out in the eighth round.;

*Andrei Gromyko

Andrei Andreyevich Gromyko (russian: Андрей Андреевич Громыко; be, Андрэй Андрэевіч Грамыка; – 2 July 1989) was a Soviet communist politician and diplomat during the Cold War. He served as ...

, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

's representative to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

submitted a response to the Baruch Plan proposed by the United States six days earlier, with a disarmament plan of his own. The Soviet proposal was that the world's nations ratify a treaty pledging not to build nuclear weapons, and that within 90 days after ratification, the United States would destroy its atomic weapons arsenal.

*Sixty-three Germans and twenty Ukrainian refugees were killed in the explosion of ammunition that had been stored by the Nazi German regime in a salt mine at Hänigsen, near Celle.

June 20, 1946 (Thursday)

*An agreement to withdraw all Allied occupation forces from Italy, over a 90-day period, was approved in Paris by the representatives of the "Big Four" powers (France, the

*An agreement to withdraw all Allied occupation forces from Italy, over a 90-day period, was approved in Paris by the representatives of the "Big Four" powers (France, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, the United States and the United Kingdom). The Soviets also agreed to withdraw their troops from Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

.

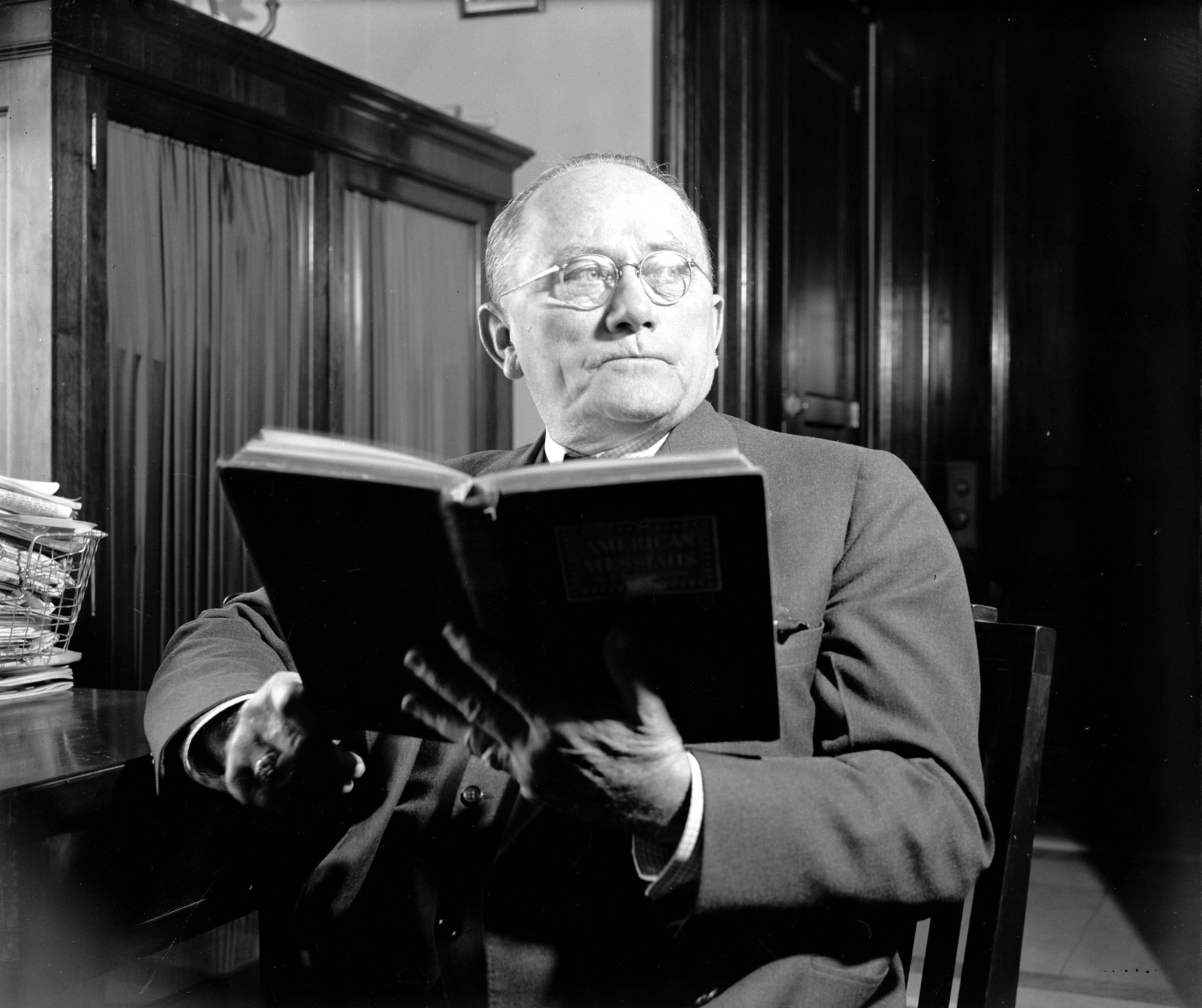

* Fred M. Vinson was confirmed as the new Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court by unanimous vote of the U.S. Senate. Vinson, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, was sworn in four days later.

*The drama film '' Anna and the King of Siam'' starring Irene Dunne

Irene Dunne (born Irene Marie Dunn; December 20, 1898 – September 4, 1990) was an American actress who appeared in films during the Golden Age of Hollywood. She is best known for her comedic roles, though she performed in films of other gen ...

and Rex Harrison was released.

*Born: Xanana Gusmão

José Alexandre "Xanana" Gusmão (; born 20 June 1946) is an East Timorese politician. A former rebel, he was the third President of the independent East Timor, serving from 2002 to 2007. He then became its fourth prime minister, serving from ...

, first President of East Timor

The president of the Democratic Republic of Timor Leste ( pt, Presidente da República Democrática de Timor-Leste; tet, Prezidente Republika Demokratika Timor-Leste) is the head of state of the Democratic Republic of Timor Leste. The executiv ...

(2002–2007), Prime Minister 2007 to 2015; in Manatuto

Manatuto is a city in Manatuto Municipality, East Timor.

Manatuto Vila has 3,692 inhabitants (Census 2015) and is capital of the subdistrict and district Manatuto. It is on the north coast of Timor, (about as the crow flies) east of Dili, ...

, Portuguese Timor

Portuguese Timor ( pt, Timor Português) was a colonial possession of Portugal that existed between 1702 and 1975. During most of this period, Portugal shared the island of Timor with the Dutch East Indies.

The first Europeans to arrive in the ...

*Died: Wanrong, 39, the last Empress Consort of China following her marriage to Emperor Puyi

Aisin-Gioro Puyi (; 7 February 1906 – 17 October 1967), courtesy name Yaozhi (曜之), was the last emperor of China as the eleventh and final Qing dynasty monarch. He became emperor at the age of two in 1908, but was forced to abdicate on 1 ...

June 21, 1946 (Friday)

*At theNuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945, Nazi Germany invaded m ...

, Albert Speer, who had been the German Minister of Armaments and War Production, testified before the War Crimes Tribunal that the Nazis had been "a year or two away from splitting the atom" before the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Speer said that Germany's development of a nuclear bomb had been delayed because many of its atomic scientists had fled to the United States to escape Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's regime.

*A cloud of ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous wa ...

killed seven people and injured 41 at the Baker Hotel in Dallas

Dallas () is the List of municipalities in Texas, third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of metropolitan statistical areas, fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 ...

. Most of the victims were hotel employees who were overcome when an air conditioning unit, in the hotel's basement, exploded.

June 22, 1946 (Saturday)

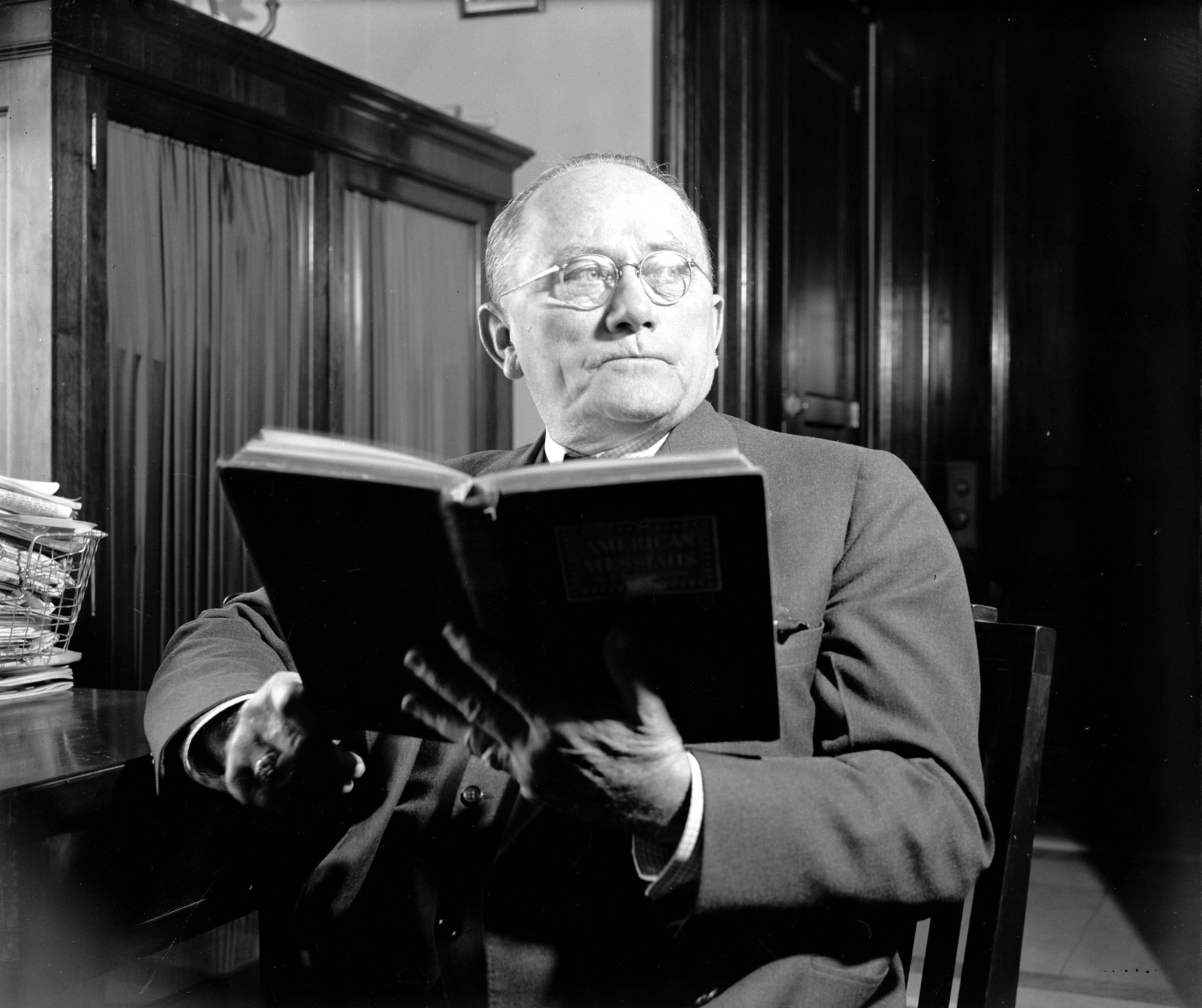

*U.S. Senator Theodore G. Bilbo of

*U.S. Senator Theodore G. Bilbo of Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, running for re-election in the Democratic primary, said in a radio broadcast that he was calling on every "red-blooded Anglo-Saxon man in Mississippi to resort to any means to keep hundreds of Negroes from the polls in the July 2 primary", then added "And if you don't know what the means, you are just not up on your persuasive measures.". Bilbo won re-election in the primary and general election, but as a result of his call for violence against African-American voters, the United States Senate refused to let him be sworn in for a new term.

*The first delivery of the United States mail by jet plane was made by two P-80 Shooting Star planes. The inaugural flight left Schenectady

Schenectady () is a city in Schenectady County, New York, United States, of which it is the county seat. As of the 2020 census, the city's population of 67,047 made it the state's ninth-largest city by population. The city is in eastern New Y ...

, New York at 12:18 and arrived in Washington, D.C. at 1:07 pm, with an air mail letter delivered to President Truman.

*Born: Kay Redfield Jamison

Kay Redfield Jamison (born June 22, 1946) is an American clinical psychologist and writer. Her work has centered on bipolar disorder, which she has had since her early adulthood. She holds the post of the Dalio Professor in Mood Disorders and Psy ...

, American psychiatrist and bipolar disorder specialist

June 23, 1946 (Sunday)

*TheMonnet Plan

:''This article deals with the 1946–50 plan of the immediate post-war period. For the Monnet plan of 1950, see European Coal and Steel Community.

Faced with the challenge of reconstruction after World War II, France implemented the Modernization ...

, France's proposal to dismantle 200 factories in the French Zone of Occupation in southeast Germany to offset France's war losses of 4,869,000,000,000 francs

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centu ...

(40 billion dollars) was presented. Over the next three years, the machinery from 22 factories in the occupation zone would be moved to France, and another 88 factories would be destroyed.

*The National Democratic Front won a landslide victory in the municipal elections in French India

*Born: Ted Shackelford

Theodore Tillman Shackelford III (born June 23, 1946) is an American actor. He played Gary Ewing in the CBS television series ''Dallas'' and ''Knots Landing'' (1979–1993); since 2006, he has appeared in a recurring role on the CBS soap ''The Yo ...

, American television actor known for '' Knots Landing'' from 1979 to 1993; in Oklahoma City

Oklahoma City (), officially the City of Oklahoma City, and often shortened to OKC, is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The county seat of Oklahoma County, it ranks 20th among United States cities in population, a ...

*Died: William S. Hart

William Surrey Hart (December 6, 1864 – June 23, 1946) was an American silent film actor, screenwriter, director and producer. He is remembered as a foremost Western star of the silent era who "imbued all of his characters with honor and inte ...

, 81, American film actor and star of Westerns during silent era

June 24, 1946 (Monday)

*Seven players on theSpokane Indians

The Spokane Indians are a Minor League Baseball team located in Spokane Valley, the city immediately east of Spokane, Washington, in the Pacific Northwest. The Indians are members of the High-A Northwest League (NWL) as an affiliate of the Color ...

minor league baseball team, and their manager, were killed when their bus veered through a guard rail on the Snoqualmie Pass

Snoqualmie Pass is a mountain pass that carries Interstate 90 (I-90) through the Cascade Range in the U.S. state of Washington. The pass summit is at an elevation of , on the county line between Kittitas County and King County.

Snoqualmie ...

Highway and plunged down a 500-foot embankment and into a ravine. The Indians, in fifth place in the Western International League

The Western International League was a mid- to higher-level minor league baseball circuit in the Pacific Northwest United States and western Canada that operated in 1922, 1937 to 1942 and 1946 to 1954. In 1955, the Western International Leagu ...

(now the Northwest League

The Northwest League is a Minor League Baseball league that operates in the Northwestern United States and Western Canada. A Class A Short Season league for most of its history, the league was promoted to High-A as part of Major League Basebal ...

) had been on their way to Bremerton, Washington

Bremerton is a city in Kitsap County, Washington. The population was 37,729 at the 2010 census and an estimated 41,405 in 2019, making it the largest city on the Kitsap Peninsula. Bremerton is home to Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and the Bremer ...

, for a seven-game series against the Bluejackets.

*Born:

** Ellison Onizuka, American astronaut; in Kealakekua, Hawaii

Kealakekua is a census-designated place (CDP) in Hawaii County, Hawaii, United States. The population was 2,019 at the 2010 census, up from 1,645 at the 2000 census.

It was the subject of the 1933 popular song, "My Little Grass Shack in Keala ...

(killed in the ''Challenger'' disaster 1986)

**Robert Reich

Robert Bernard Reich (; born June 24, 1946) is an American professor, author, lawyer, and political commentator. He worked in the administrations of Presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, and served as Secretary of Labor from 1993 to 1997 in ...

, U.S. Secretary of Labor 1993 to 1997; in Scranton, Pennsylvania

Scranton is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Lackawanna County. With a population of 76,328 as of the 2020 U.S. census, Scranton is the largest city in Northeastern Pennsylvania, the Wyoming V ...

June 25, 1946 (Tuesday)

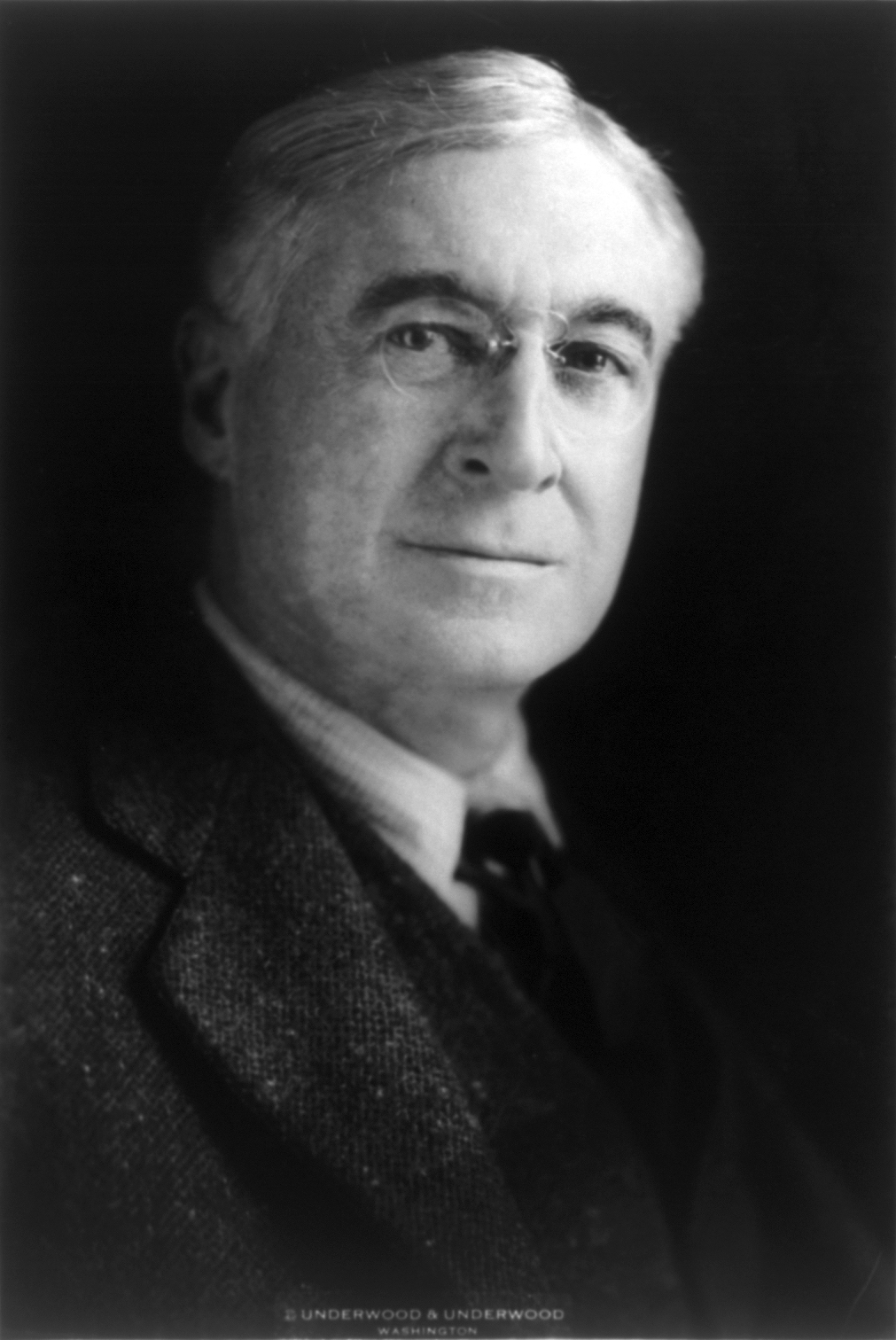

*TheWorld Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purpose of pursuing capital projects. The World Bank is the collective name for the Inte ...

(officially the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development) began operations, with Eugene Meyer, former chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve Board

The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, commonly known as the Federal Reserve Board, is the main governing body of the Federal Reserve System. It is charged with overseeing the Federal Reserve Banks and with helping implement the m ...

, as the IBRD's first president.

*Ten middle school students were killed and twenty wounded at Xuzhou

Xuzhou (徐州), also known as Pengcheng (彭城) in ancient times, is a major city in northwestern Jiangsu province, China. The city, with a recorded population of 9,083,790 at the 2020 census (3,135,660 of which lived in the built-up area ma ...

(Hsuchow), in China's Jiangsu province, after Nationalist Army officer Feng Yu-xiang Fang Jingxing ordered them to be fired on by machine guns. The massacre followed an angry confrontation between the students and the officer.

June 26, 1946 (Wednesday)

*Taking theChinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

into a new phase, President Chiang Kai-shek launched a nationwide military campaign against the Communist Chinese forces of Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

, with Chiang's Nationalist Army moving into central China to take back rural areas that were under Communist control. The Nationalists had superior weapons and more troops, and Chiang received American aid for a strategy that he hoped would defeat Mao's forces within six months. Within nine months, it was clear that the campaign was failing, and by the end of 1949, China's mainland was under control of the Communist forces.

*On the day the campaign started, Nationalist Chinese pilot Liu Shanben defected to the Communists and delivered a B-24 Liberator bomber to the opposition, starting a wave of similar acts. Within three years, 54 pilots and 20 airplanes joined the Communist side.

*William Heirens

William George Heirens (November 15, 1928 – March 5, 2012) was an American criminal and possible serial killer who "confessed" to three murders. He was subsequently controversially convicted of the crimes in 1946. Heirens was called the Lipstic ...

, a 17-year-old student at the University of Chicago, was arrested for burglary, and soon charged with three murders tied to "The Lipstick Killer", including the January 7 murder of 6-year old Suzanne Degnan.

*Died: Alexander Duncan McRae

Alexander Duncan McRae, (November 17, 1874 – June 26, 1946) was a successful businessman, a Major General in the Canadian Army in First World War, a Member of Parliament, a Canadian Senator and a farmer.

Origins

Alexander Duncan McRae was bo ...

, 71, Canadian multimillionaire

June 27, 1946 (Thursday)

*All 46 people aboard the Spanish submarine C-4 were killed after the sub collided with the Spanish destroyer ''Lepanto'' during a naval exercise off of the Balearic Islands. *The Canadian Citizenship Act was approved by Canada's House of Commons, separating Canadian citizenship from British nationality, effective January 1, 1947; Canada was the first Commonwealth country to create its own citizenship laws. *Born:Sally Priesand

Sally Jane Priesand (born June 27, 1946) is America's first female rabbi ordained by a rabbinical seminary, and the second formally ordained female rabbi in Jewish history, after Regina Jonas. Priesand was ordained by the Hebrew Union College-J ...

, first woman rabbi in the United States; in Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

.

*Died: Juan Antonio Ríos

Juan Antonio Ríos Morales (; November 10, 1888 – June 27, 1946) was a Chilean political figure who served as president of Chile from 1942 to 1946, during the height of World War II. He died in office.

Early life

Ríos was born at the ''Hu ...

, 57, President of Chile

The president of Chile ( es, Presidente de Chile), officially known as the President of the Republic of Chile ( es, Presidente de la República de Chile), is the head of state and head of government of the Republic of Chile. The president is r ...

since 1942; of cancer

June 28, 1946 (Friday)

*The first recorded birth in Japan of a baby born of a Japanese mother and one of the American soldiers occupying Japan, was announced on Japanese radio. The birth, the first of tens of thousands that would follow, came a little more than nine months after the first American occupation forces had arrived on theHonshu

, historically called , is the largest and most populous island of Japan. It is located south of Hokkaidō across the Tsugaru Strait, north of Shikoku across the Inland Sea, and northeast of Kyūshū across the Kanmon Straits. The island se ...

island.

*Born: Gilda Radner, American comedian and actress; in Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

(d. 1989)

*Died: Antoinette Perry

Mary Antoinette "Tony" Perry (June 27, 1888June 28, 1946) was an American actress and director, and co-founder of the American Theatre Wing. She is the eponym of the Tony Awards.

Early life

Born in Denver, Colorado, she spent her childhood asp ...

, 58, American stage actress for whom the Tony Award

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre, more commonly known as the Tony Award, recognizes excellence in live Broadway theatre. The awards are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League at an annual ce ...

s are named

June 29, 1946 (Saturday)

*In Palestine, the British Army oversaw "Operation Agatha

Operation Agatha (Saturday, June 29, 1946), sometimes called Black Sabbath ( he, השבת השחורה) or Black Saturday because it began on the Jewish sabbath, was a police and military operation conducted by the British authorities in Mandato ...

", the arrest of 2,700 suspected Jewish terrorists in retaliation of the destruction of 11 bridges two weeks earlier, detaining them at a prison camp at Latrun

Latrun ( he, לטרון, ''Latrun''; ar, اللطرون, ''al-Latrun'') is a strategic hilltop in the Latrun salient in the Ayalon Valley, and a depopulated Palestinian village. It overlooks the road between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, 25 kilometers ...

. The Haganah escalated terror attacks in response, with the King David Hotel bombing

The British administrative headquarters for Mandatory Palestine, housed in the southern wing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, were bombed in a terrorist attack on 22 July 1946 by the militant right-wing Zionist underground organization the ...

taking place the following month.

*Born: Egon von Fürstenberg

Egon is a variant of the male given name Eugene. It is most commonly found in Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Estonia, Hungary, Slovakia, Sweden, Denmark, and parts of the Netherlands and Belgium. The name can also be derived from the G ...

, Swiss fashion designer who created "the power look"; in Lausanne

, neighboring_municipalities= Bottens, Bretigny-sur-Morrens, Chavannes-près-Renens, Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, Crissier, Cugy, Écublens, Épalinges, Évian-les-Bains (FR-74), Froideville, Jouxtens-Mézery, Le Mont-sur-Lausanne, Lugrin (FR ...

(d. 2004)

June 30, 1946 (Sunday)

*After nearly five years of price and wage controls by the United StatesOffice of Price Administration

The Office of Price Administration (OPA) was established within the Office for Emergency Management of the United States government by Executive Order 8875 on August 28, 1941. The functions of the OPA were originally to control money (price contr ...

, the OPA's emergency wartime powers ended at midnight. Two days earlier, the U.S. Senate declined to extend the OPA's authority, and a final appeal to the American public by President Truman failed. Expiring at midnight also were the mandates of the Fair Employment Practice Committee

The Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) was created in 1941 in the United States to implement Executive Order 8802 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt "banning discriminatory employment practices by Federal agencies and all unions and com ...

(FEPC), which had acted against discrimination by race, and the War Relocation Authority

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a United States government agency established to handle the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It also operated the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York, which was t ...

, which carried out racial discrimination, most notably in the internment of more than 100,000 Japanese Americans during World War II, was abolished.

* In a national referendum, voters in Poland were presented with a yes-or-no choice on three issues: abolishing the Senate; supporting nationalization of industries and land, and conforming the border with the Soviet Union to reflect the loss of lands east of the Odra and Nysa rivers. Official results showed two-thirds approval of all three measures, placed Poland under Communist rule for the next 43 years, by the Polish Workers' Party

The Polish Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Partia Robotnicza, PPR) was a communist party in Poland from 1942 to 1948. It was founded as a reconstitution of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP) and merged with the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) in 194 ...

."Polish Voters Favor One-House Parliament", ''St. Petersburg (FL) Times'', July 5, 1946; Jaff Schatz, ''The Generation: The Rise and Fall of the Jewish Communists of Poland'' (University of California Press 1991) p205

References

{{Events by month links 1946 *1946-06 *1946-06