Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe t ...

,

natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

,

separatist theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

,

grammarian, multi-subject educator, and

liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

political theorist

A political theorist is someone who engages in constructing or evaluating political theory, including political philosophy. Theorists may be Academia, academics or independent scholars. Here the most notable political theorists are categorized b ...

.

[ He published over 150 works, and conducted experiments in electricity and other areas of science. He was a close friend of, and worked in close association with ]Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

involving electricity experiments.

Priestley is credited with his independent discovery of oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

by the thermal decomposition of mercuric oxide, having isolated it in 1774. During his lifetime, Priestley's considerable scientific reputation rested on his invention of carbonated water, his writings on electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as describ ...

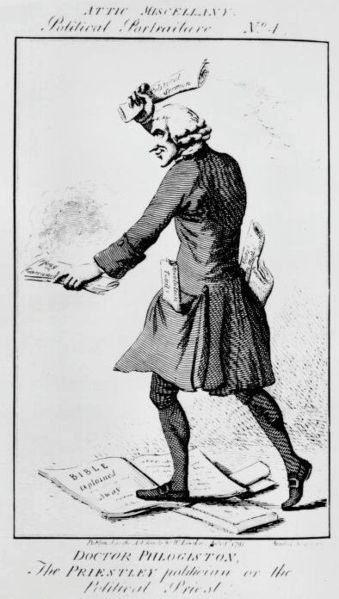

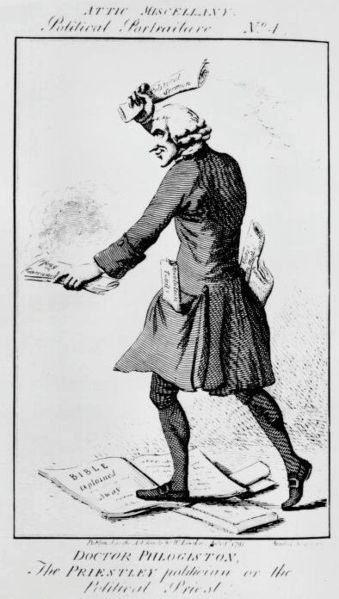

, and his discovery of several "airs" (gases), the most famous being what Priestley dubbed "dephlogisticated air" (oxygen). Priestley's determination to defend phlogiston theory

The phlogiston theory is a superseded scientific theory that postulated the existence of a fire-like element called phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burni ...

and to reject what would become the chemical revolution

The chemical revolution, also called the ''first chemical revolution'', was the early modern reformulation of chemistry that culminated in the law of conservation of mass and the oxygen theory of combustion.

During the 19th and 20th century, this ...

eventually left him isolated within the scientific community.

Priestley's science was integral to his theology, and he consistently tried to fuse Enlightenment rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy ...

with Christian theism

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with '' deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred ...

. In his metaphysical texts, Priestley attempted to combine theism, materialism, and determinism, a project that has been called "audacious and original".[ He believed that a proper understanding of the natural world would promote human ]progress

Progress is the movement towards a refined, improved, or otherwise desired state. In the context of progressivism, it refers to the proposition that advancements in technology, science, and social organization have resulted, and by extension w ...

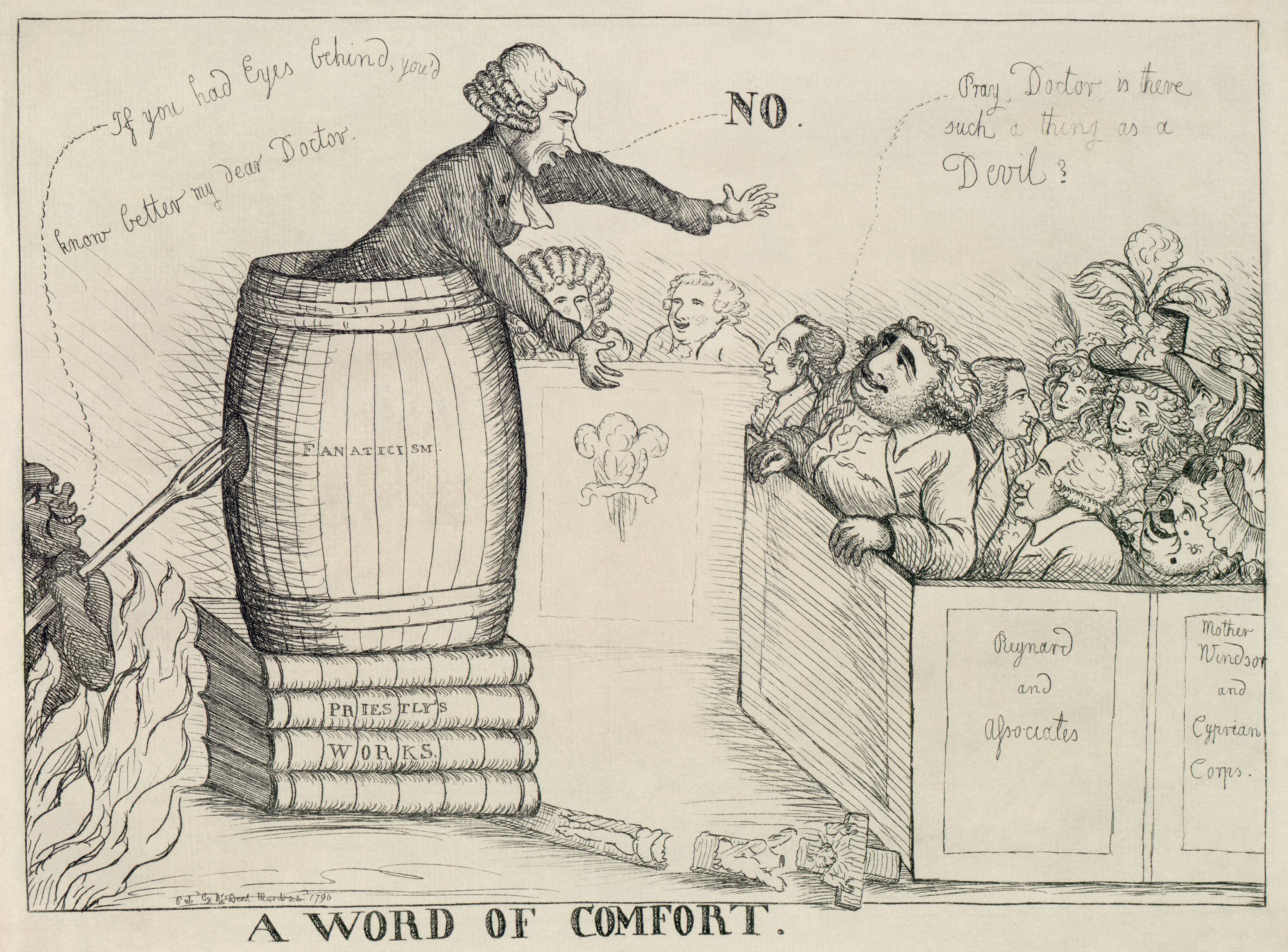

and eventually bring about the Christian millennium.[Tapper, 314.] Priestley, who strongly believed in the free and open exchange of ideas, advocated toleration

Toleration is the allowing, permitting, or acceptance of an action, idea, object, or person which one dislikes or disagrees with. Political scientist Andrew R. Murphy explains that "We can improve our understanding by defining "toleration" as ...

and equal rights for religious Dissenters, which also led him to help found Unitarianism

Unitarianism (from Latin ''unitas'' "unity, oneness", from ''unus'' "one") is a nontrinitarian branch of Christian theology. Most other branches of Christianity and the major Churches accept the doctrine of the Trinity which states that there i ...

in England. The controversial nature of Priestley's publications, combined with his outspoken support of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

and later the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

, aroused public and governmental contempt; eventually forcing him to flee in 1791, first to London and then to the United States, after a mob burned down his Birmingham home and church. He spent his last ten years in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania

Northumberland County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is part of Northeastern Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, the population was 91,647. Its county seat is Sunbury.

The county was formed in 1772 from parts of Lancas ...

.

A scholar and teacher throughout his life, Priestley made significant contributions to pedagogy

Pedagogy (), most commonly understood as the approach to teaching, is the theory and practice of learning, and how this process influences, and is influenced by, the social, political and psychological development of learners. Pedagogy, taken ...

, including the publication of a seminal work on English grammar

English grammar is the set of structural rules of the English language. This includes the structure of words, phrases, clauses, Sentence (linguistics), sentences, and whole texts.

This article describes a generalized, present-day Standard English ...

and books on history; he prepared some of the most influential early timelines. The educational writings were among Priestley's most popular works. Arguably his metaphysical works, however, had the most lasting influence, as now considered primary sources for utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different chara ...

by philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

, John Stuart Mill, and Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression " survival of the fi ...

.

Early life and education (1733–1755)

Priestley was born to an established English Dissenting family (i.e. they did not conform to the

Priestley was born to an established English Dissenting family (i.e. they did not conform to the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

) in Birstall (near Batley) in the West Riding of Yorkshire

The West Riding of Yorkshire is one of three historic subdivisions of Yorkshire, England. From 1889 to 1974 the administrative county County of York, West Riding (the area under the control of West Riding County Council), abbreviated County ...

. He was the oldest of six children born to Mary Swift and Jonas Priestley, a finisher of cloth. Priestley was sent to live with his grandfather around the age of one. He returned home five years later, after his mother died. When his father remarried in 1741, Priestley went to live with his aunt and uncle, the wealthy and childless Sarah (d. 1764), and John Keighley, from Fieldhead.[ Gray & Harrison: Oxford Dictionary of National Bilography, pp. 351-352]

Priestley was quite precocious as a child—at the age of four, he could flawlessly recite all 107 questions and answers of the Westminster Shorter Catechism

The Westminster Shorter Catechism is a catechism written in 1646 and 1647 by the Westminster Assembly, a synod of English and Scottish theologians and laymen intended to bring the Church of England into greater conformity with the Church of Sco ...

—his aunt sought the best education for him, intending him to enter ministry. During his youth, Priestley attended local schools, where he learned Greek, Latin, and Hebrew.

Around 1749, Priestley became seriously ill and believed he was dying. Raised as a devout Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

, he believed a conversion experience was necessary for salvation, but doubted he had had one. This emotional distress eventually led him to question his theological upbringing, causing him to reject election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

and to accept universal salvation. As a result, the elders of his home church, the Independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

Upper Chapel of Heckmondwike

Heckmondwike is a town in the metropolitan borough of Kirklees, West Yorkshire, England, south west of Leeds. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is close to Cleckheaton and Liversedge. It is mostly in the Batley and Spen pa ...

, refused him admission as a full member.[

Priestley's illness left him with a permanent stutter and he gave up any thoughts of entering the ministry at that time. In preparation for joining a relative in trade in Lisbon, he studied French, Italian, and German in addition to ]Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated in ...

, and Arabic. He was tutored by the Reverend George Haggerstone, who first introduced him to higher mathematics, natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

, logic, and metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

through the works of Isaac Watts

Isaac Watts (17 July 1674 – 25 November 1748) was an English Congregational minister, hymn writer, theologian, and logician. He was a prolific and popular hymn writer and is credited with some 750 hymns. His works include "When I Survey the ...

, Willem 's Gravesande

Willem Jacob 's Gravesande (26 September 1688 – 28 February 1742) was a Dutch mathematician and natural philosopher, chiefly remembered for developing experimental demonstrations of the laws of classical mechanics and the first experimental m ...

, and John Locke.

Daventry Academy

Priestley eventually decided to return to his theological studies and, in 1752, matriculated at Daventry

Daventry ( , historically ) is a market town and civil parish in the West Northamptonshire unitary authority in Northamptonshire, England, close to the border with Warwickshire. At the 2021 Census Daventry had a population of 28,123, making ...

, a Dissenting academy. Because he had already read widely, Priestley was allowed to skip the first two years of coursework. He continued his intense study; this, together with the liberal atmosphere of the school, shifted his theology further leftward and he became a Rational Dissenter

English Dissenters or English Separatists were Protestant Christians who separated from the Church of England in the 17th and 18th centuries.

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who disagrees in opinion, belief and ...

. Abhorring dogma and religious mysticism, Rational Dissenters emphasised the rational analysis of the natural world and the Bible.

Priestley later wrote that the book that influenced him the most, save the Bible, was David Hartley's '' Observations on Man'' (1749). Hartley's psychological, philosophical, and theological treatise postulated a material theory of mind

In psychology, theory of mind refers to the capacity to understand other people by ascribing mental states to them (that is, surmising what is happening in their mind). This includes the knowledge that others' mental states may be different fro ...

. Hartley aimed to construct a Christian philosophy in which both religious and moral "facts" could be scientifically proven, a goal that would occupy Priestley for his entire life. In his third year at Daventry, Priestley committed himself to the ministry, which he described as "the noblest of all professions".

Needham Market and Nantwich (1755–1761)

Robert Schofield, Priestley's major modern biographer, describes his first "call" in 1755 to the Dissenting parish in Needham Market, Suffolk, as a "mistake" for both Priestley and the congregation. Priestley yearned for urban life and theological debate, whereas Needham Market was a small, rural town with a congregation wedded to tradition. Attendance and donations dropped sharply when they discovered the extent of his heterodoxy. Although Priestley's aunt had promised her support if he became a minister, she refused any further assistance when she realised he was no longer a Calvinist. To earn extra money, Priestley proposed opening a school, but local families informed him that they would refuse to send their children. He also presented a series of scientific lectures titled "Use of the Globes" that was more successful.

Priestley's Daventry friends helped him obtain another position and in 1758 he moved to

Robert Schofield, Priestley's major modern biographer, describes his first "call" in 1755 to the Dissenting parish in Needham Market, Suffolk, as a "mistake" for both Priestley and the congregation. Priestley yearned for urban life and theological debate, whereas Needham Market was a small, rural town with a congregation wedded to tradition. Attendance and donations dropped sharply when they discovered the extent of his heterodoxy. Although Priestley's aunt had promised her support if he became a minister, she refused any further assistance when she realised he was no longer a Calvinist. To earn extra money, Priestley proposed opening a school, but local families informed him that they would refuse to send their children. He also presented a series of scientific lectures titled "Use of the Globes" that was more successful.

Priestley's Daventry friends helped him obtain another position and in 1758 he moved to Nantwich

Nantwich ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. It has among the highest concentrations of listed buildings in England, with notably good examples of Tudor and Georgian architecture. ...

, Cheshire, living at Sweetbriar Hall in the town's Hospital Street; his time there was happier. The congregation cared less about Priestley's heterodoxy and he successfully established a school. Unlike many schoolmasters of the time, Priestley taught his students natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

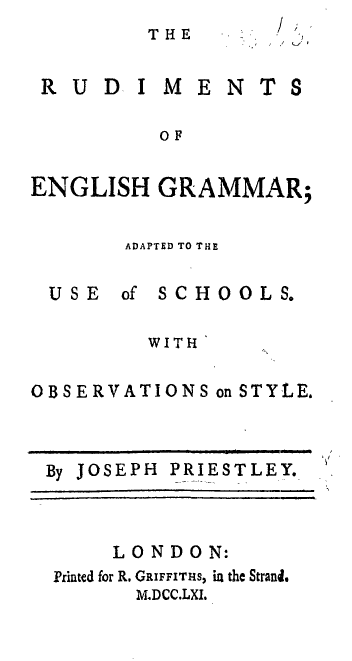

and even bought scientific instruments for them. Appalled at the quality of the available English grammar books, Priestley wrote his own: ''The Rudiments of English Grammar

''The Rudiments of English Grammar'' (1761) was a popular English grammar textbook written by the 18th-century British polymath Joseph Priestley.

While a minister for a congregation in Nantwich, Cheshire, Priestley established a local school; it ...

'' (1761). His innovations in the description of English grammar, particularly his efforts to dissociate it from Latin grammar

Latin is a heavily inflected language with largely free word order. Nouns are inflected for number and case; pronouns and adjectives (including participles) are inflected for number, case, and gender; and verbs are inflected for person, ...

, led 20th-century scholars to describe him as "one of the great grammarians of his time". After the publication of ''Rudiments'' and the success of Priestley's school, Warrington Academy

Warrington Academy, active as a teaching establishment from 1756 to 1782, was a prominent dissenting academy, that is, a school or college set up by those who dissented from the established Church of England. It was located in Warrington (then ...

offered him a teaching position in 1761.

Warrington Academy (1761–1767)

In 1761, Priestley moved to

In 1761, Priestley moved to Warrington

Warrington () is a town and unparished area in the borough of the same name in the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England, on the banks of the River Mersey. It is east of Liverpool, and west of Manchester. The population in 2019 was estimat ...

in Cheshire and assumed the post of tutor of modern languages and rhetoric at the town's Dissenting academy, although he would have preferred to teach mathematics and natural philosophy. He fitted in well at Warrington, and made friends quickly.Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795) was an English potter, entrepreneur and abolitionist. Founding the Wedgwood company in 1759, he developed improved pottery bodies by systematic experimentation, and was the leader in the indus ...

. Wedgwood met Priestley in 1762, after a fall from his horse. Wedgwood and Priestley met rarely, but exchanged letters, advice on chemistry, and laboratory equipment. Wedgwood eventually created a medallion of Priestley in cream-on-blue jasperware

Jasperware, or jasper ware, is a type of pottery first developed by Josiah Wedgwood in the 1770s. Usually described as stoneware, it has an unglazed matte "biscuit" finish and is produced in a number of different colours, of which the most com ...

.Wrexham

Wrexham ( ; cy, Wrecsam; ) is a city and the administrative centre of Wrexham County Borough in Wales. It is located between the Welsh mountains and the lower Dee Valley, near the border with Cheshire in England. Historically in the count ...

. Of his marriage, Priestley wrote:

This proved a very suitable and happy connexion, my wife being a woman of an excellent understanding, much improved by reading, of great fortitude and strength of mind, and of a temper in the highest degree affectionate and generous; feeling strongly for others, and little for herself. Also, greatly excelling in every thing relating to household affairs, she entirely relieved me of all concern of that kind, which allowed me to give all my time to the prosecution of my studies, and the other duties of my station.

On 17 April 1763, they had a daughter, whom they named Sarah after Priestley's aunt.

Educator and historian

All of the books Priestley published while at Warrington emphasised the study of history; Priestley considered it essential for worldly success as well as religious growth. He wrote histories of science and Christianity in an effort to reveal the progress of humanity and, paradoxically, the loss of a pure, "primitive Christianity".

In his '' Essay on a Course of Liberal Education for Civil and Active Life'' (1765), ''

In his '' Essay on a Course of Liberal Education for Civil and Active Life'' (1765), ''Lectures on History and General Policy

''Lectures on History and General Policy'' (1788) is the published version of a set of lectures on history and government given by the 18th-century British polymath Joseph Priestley to the students of Warrington Academy.

The ''Lectures'' cover ...

'' (1788), and other works, Priestley argued that the education of the young should anticipate their future practical needs. This principle of utility guided his unconventional curricular choices for Warrington's aspiring middle-class students. He recommended modern languages instead of classical languages and modern rather than ancient history. Priestley's lectures on history were particularly revolutionary; he narrated a providentialist and naturalist account of history, arguing that the study of history furthered the comprehension of God's natural laws. Furthermore, his millennial perspective was closely tied to his optimism regarding scientific progress and the improvement of humanity. He believed that each age would improve upon the previous and that the study of history allowed people to perceive and to advance this progress. Since the study of history was a moral imperative for Priestley, he also promoted the education of middle-class women, which was unusual at the time. Some scholars of education have described Priestley as the most important English writer on education between the 17th-century John Locke and the 19th-century Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression " survival of the fi ...

. ''Lectures on History'' was well received and was employed by many educational institutions, such as New College at Hackney, Brown

Brown is a color. It can be considered a composite color, but it is mainly a darker shade of orange. In the CMYK color model used in printing or painting, brown is usually made by combining the colors orange and black. In the RGB color model us ...

, Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ni ...

, Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

, and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

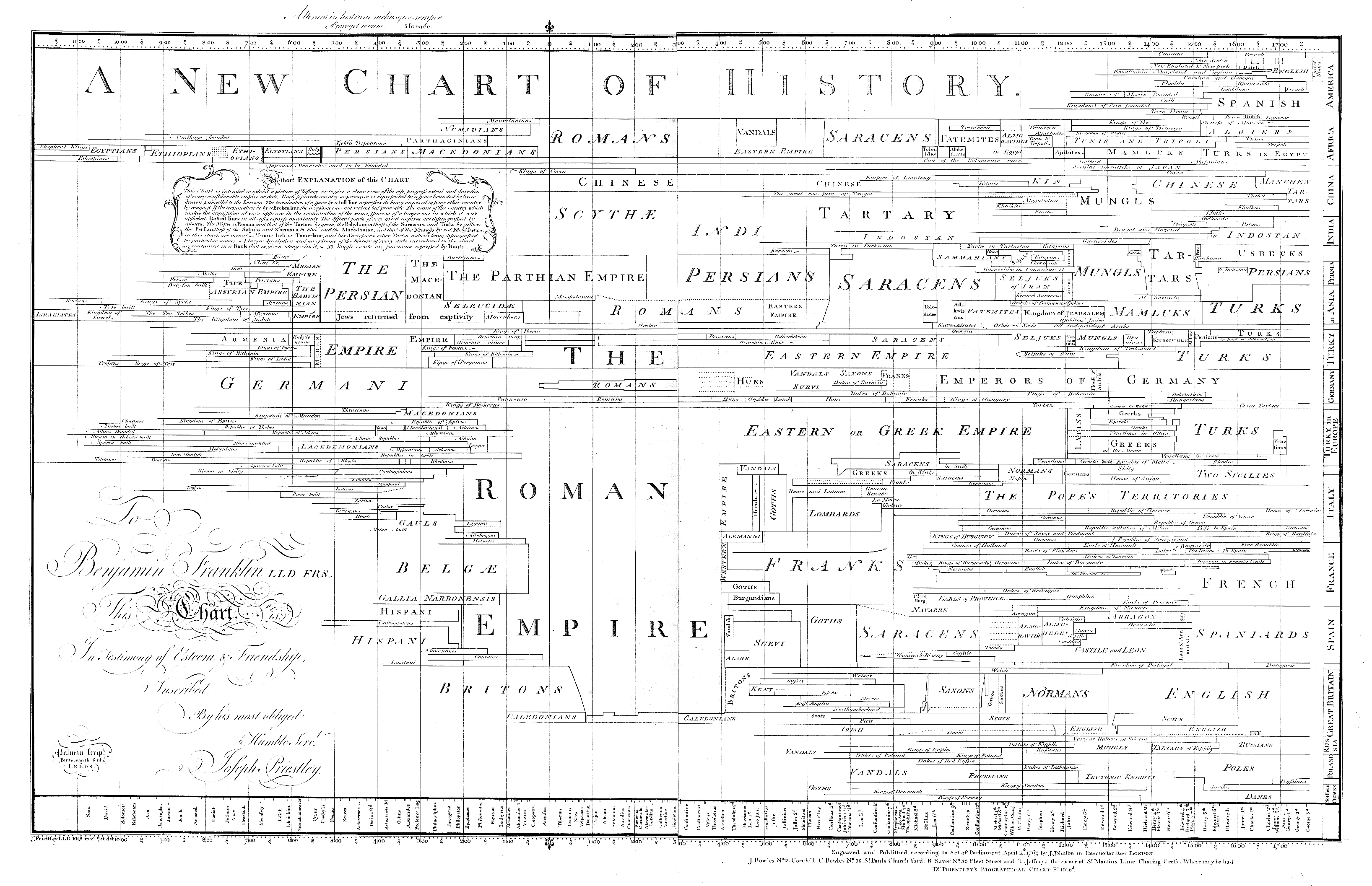

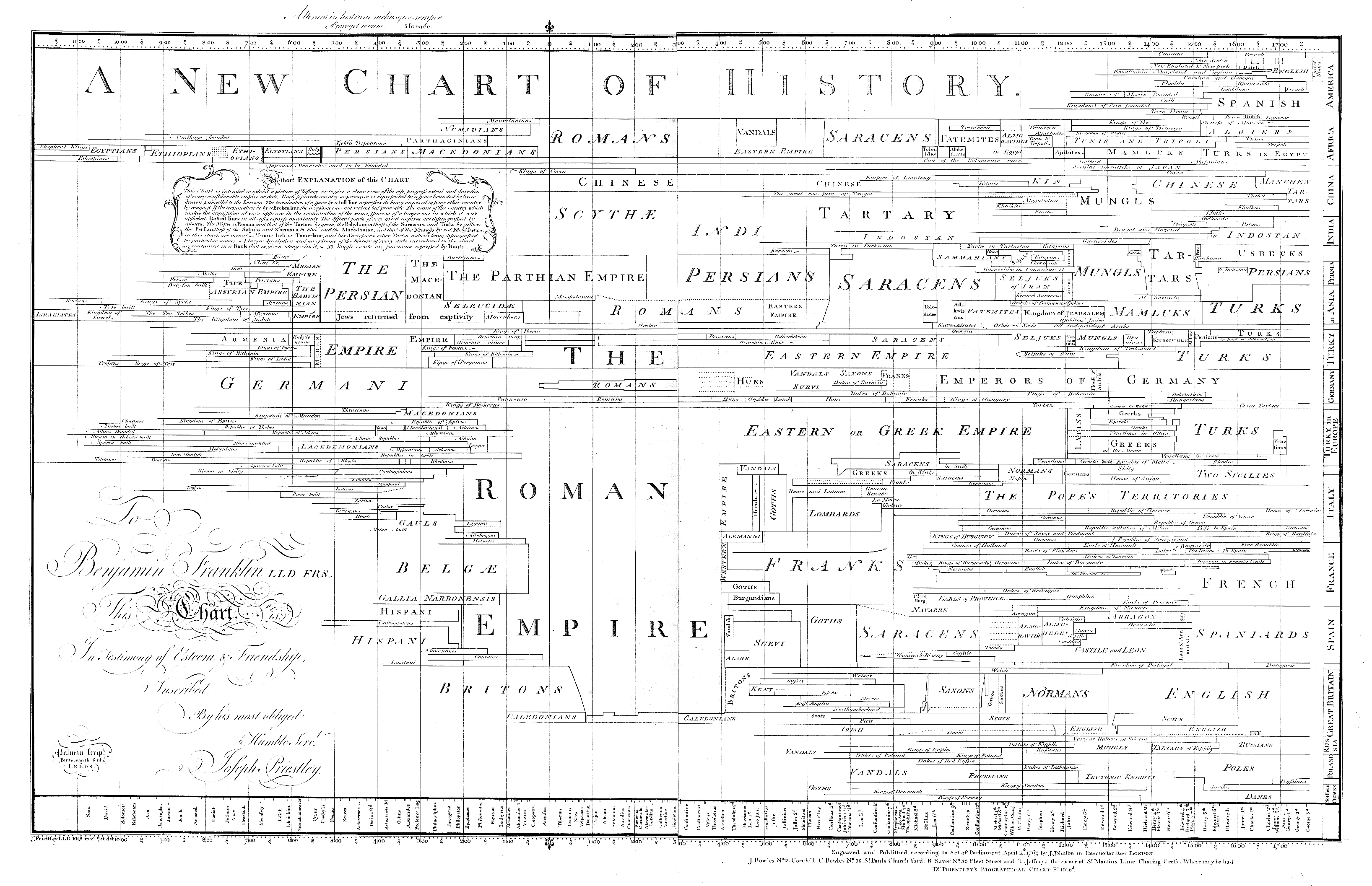

. Priestley designed two ''Charts'' to serve as visual study aids for his ''Lectures''. These charts are in fact timelines; they have been described as the most influential timelines published in the 18th century. Both were popular for decades, and the trustees of Warrington were so impressed with Priestley's lectures and charts that they arranged for the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

to grant him a Doctor of Law

A Doctor of Law is a degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country and includes degrees such as the Doctor of Juridical Science (J.S.D. or S.J.D), Juris Doctor (J.D.), Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), and Legum Doctor (LL ...

degree in 1764. During this period Priestley also regularly delivered lectures on rhetoric that were later published in 1777 as ''A Course of Lectures on Oratory and Criticism''.

History of electricity

The intellectually stimulating atmosphere of Warrington, often called the "Athens of the North" (of England) during the 18th century, encouraged Priestley's growing interest in natural philosophy. He gave lectures on anatomy and performed experiments regarding temperature with another tutor at Warrington, his friend John Seddon. Despite Priestley's busy teaching schedule, he decided to write a history of electricity. Friends introduced him to the major experimenters in the field in Britain—

The intellectually stimulating atmosphere of Warrington, often called the "Athens of the North" (of England) during the 18th century, encouraged Priestley's growing interest in natural philosophy. He gave lectures on anatomy and performed experiments regarding temperature with another tutor at Warrington, his friend John Seddon. Despite Priestley's busy teaching schedule, he decided to write a history of electricity. Friends introduced him to the major experimenters in the field in Britain—John Canton

John Canton FRS (31 July 1718 – 22 March 1772) was a British physicist. He was born in Middle Street Stroud, Gloucestershire, to a weaver, John Canton (b. 1687) and Esther (née Davis). As a schoolboy, he became the first person to deter ...

, William Watson William, Willie, Bill or Billy Watson may refer to:

Entertainment

* William Watson (songwriter) (1794–1840), English concert hall singer and songwriter

* William Watson (poet) (1858–1935), English poet

* Billy Watson (actor) (1923–2022), A ...

, Timothy Lane, and the visiting Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

who encouraged Priestley to perform the experiments he wanted to include in his history. Priestly also consulted with Franklin during the latter's kite experiments. In the process of replicating others' experiments, Priestley became intrigued by unanswered questions and was prompted to undertake experiments of his own design. (Impressed with his ''Charts'' and the manuscript of his history of electricity, Canton, Franklin, Watson, and Richard Price

Richard Price (23 February 1723 – 19 April 1791) was a British moral philosopher, Nonconformist minister and mathematician. He was also a political reformer, pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the French ...

nominated Priestley for a fellowship in the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

; he was accepted in 1766.)

In 1767, the 700-page '' The History and Present State of Electricity'' was published to positive reviews. The first half of the text is a history of the study of electricity to 1766; the second and more influential half is a description of contemporary theories about electricity and suggestions for future research. The volume also contains extensive comments on Priestley's views that scientific inquiries be presented with all reasoning in one's discovery path, including false leads and mistakes. He contrasted his narrative approach with Newton's analytical proof-like approach which did not facilitate future researchers to continue the inquiry. Priestley reported some of his own discoveries in the second section, such as the

In 1767, the 700-page '' The History and Present State of Electricity'' was published to positive reviews. The first half of the text is a history of the study of electricity to 1766; the second and more influential half is a description of contemporary theories about electricity and suggestions for future research. The volume also contains extensive comments on Priestley's views that scientific inquiries be presented with all reasoning in one's discovery path, including false leads and mistakes. He contrasted his narrative approach with Newton's analytical proof-like approach which did not facilitate future researchers to continue the inquiry. Priestley reported some of his own discoveries in the second section, such as the conductivity

Conductivity may refer to:

*Electrical conductivity, a measure of a material's ability to conduct an electric current

**Conductivity (electrolytic), the electrical conductivity of an electrolyte in solution

** Ionic conductivity (solid state), ele ...

of charcoal and other substances and the continuum between conductors and non-conductors.[Schofield (1997), 144–56.] This discovery overturned what he described as "one of the earliest and universally received maxims of electricity", that only water and metals could conduct electricity. This and other experiments on the electrical properties of materials and on the electrical effects of chemical transformations demonstrated Priestley's early and ongoing interest in the relationship between chemical substances and electricity. Based on experiments with charged spheres, Priestley was among the first to propose that electrical force followed an inverse-square law, similar to Newton's law of universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation is usually stated as that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distan ...

. He did not generalise or elaborate on this,[ and the general law was enunciated by French physicist ]Charles-Augustin de Coulomb

Charles-Augustin de Coulomb (; ; 14 June 1736 – 23 August 1806) was a French officer, engineer, and physicist. He is best known as the eponymous discoverer of what is now called Coulomb's law, the description of the electrostatic force of attra ...

in the 1780s.

Priestley's strength as a natural philosopher was qualitative rather than quantitative and his observation of "a current of real air" between two electrified points would later interest Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

and James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism and li ...

as they investigated electromagnetism

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions of ...

. Priestley's text became the standard history of electricity for over a century; Alessandro Volta (who later invented the battery), William Herschel

Frederick William Herschel (; german: Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel; 15 November 1738 – 25 August 1822) was a German-born British astronomer and composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline ...

(who discovered infrared radiation

Infrared (IR), sometimes called infrared light, is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than those of visible light. It is therefore invisible to the human eye. IR is generally understood to encompass wavelengths from around ...

), and Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish ( ; 10 October 1731 – 24 February 1810) was an English natural philosopher and scientist who was an important experimental and theoretical chemist and physicist. He is noted for his discovery of hydrogen, which he termed "infl ...

(who discovered hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

) all relied upon it. Priestley wrote a popular version of the ''History of Electricity'' for the general public titled ''A Familiar Introduction to the Study of Electricity'' (1768). He marketed the book with his brother Timothy, but unsuccessfully.

Leeds (1767–1773)

Perhaps prompted by Mary Priestley's ill health, or financial problems, or a desire to prove himself to the community that had rejected him in his childhood, Priestley moved with his family from Warrington to

Perhaps prompted by Mary Priestley's ill health, or financial problems, or a desire to prove himself to the community that had rejected him in his childhood, Priestley moved with his family from Warrington to Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popula ...

in 1767, and he became Mill Hill Chapel

Mill Hill Chapel is a Unitarian church in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It is a member of the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches, the umbrella organisation for British Unitarians. The building, which stands in the centr ...

's minister. Two sons were born to the Priestleys in Leeds: Joseph junior on 24 July 1768 and William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

three years later. Theophilus Lindsey

Theophilus Lindsey (20 June 1723 O.S.3 November 1808) was an English theologian and clergyman who founded the first avowedly Unitarian congregation in the country, at Essex Street Chapel.

Early life

Lindsey was born in Middlewich, Cheshire, ...

, a rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

at Catterick, Yorkshire, became one of Priestley's few friends in Leeds, of whom he wrote: "I never chose to publish any thing of moment relating to theology, without consulting him." Although Priestley had extended family living around Leeds, it does not appear that they communicated. Schofield conjectures that they considered him a heretic. Each year Priestley travelled to London to consult with his close friend and publisher, Joseph Johnson, and to attend meetings of the Royal Society.

Minister of Mill Hill Chapel

When Priestley became its minister, Mill Hill Chapel

Mill Hill Chapel is a Unitarian church in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It is a member of the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches, the umbrella organisation for British Unitarians. The building, which stands in the centr ...

was one of the oldest and most respected Dissenting congregations in England; however, during the early 18th century the congregation had fractured along doctrinal lines, and was losing members to the charismatic Methodist movement. Priestley believed that by educating the young, he could strengthen the bonds of the congregation.

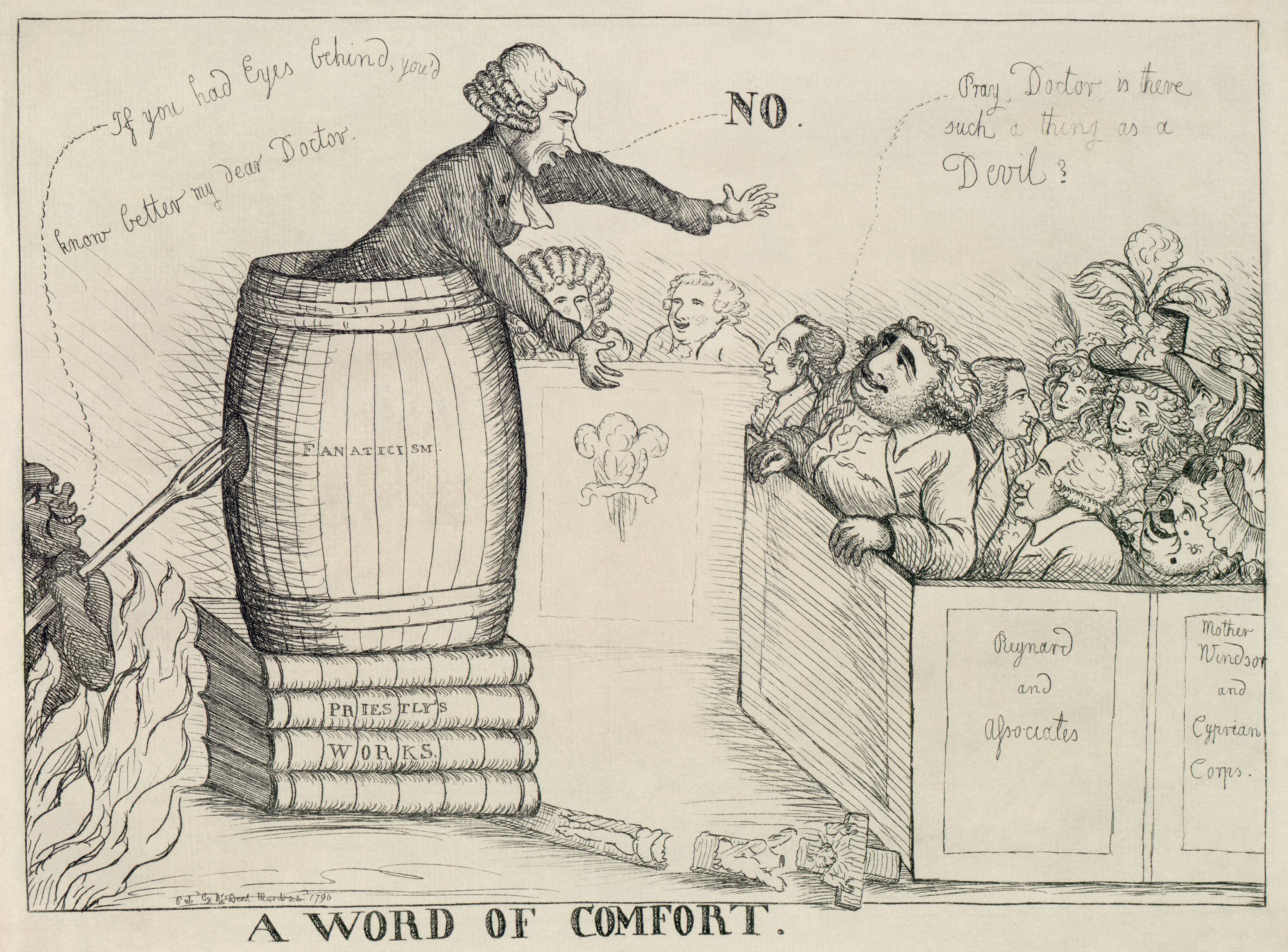

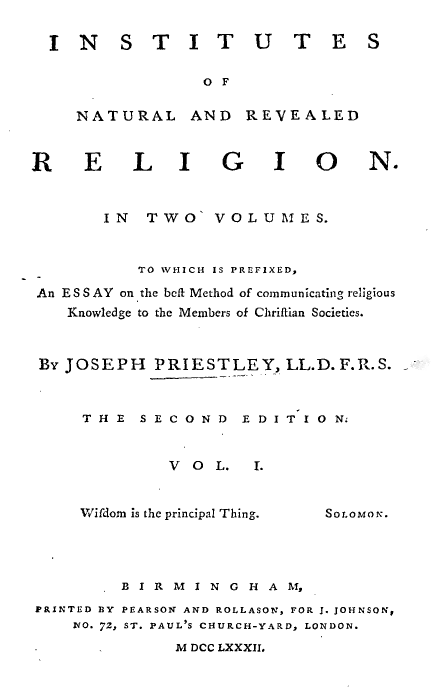

In his three-volume '' Institutes of Natural and Revealed Religion'' (1772–74), Priestley outlined his theories of religious instruction. More importantly, he laid out his belief in Socinianism. The doctrines he explicated would become the standards for Unitarians in Britain. This work marked a change in Priestley's theological thinking that is critical to understanding his later writings—it paved the way for his materialism and necessitarianism (the belief that a divine being acts in accordance with necessary metaphysical laws).

Priestley's major argument in the ''Institutes'' was that the only revealed religious truths that could be accepted were those that matched one's experience of the natural world. Because his views of religion were deeply tied to his understanding of nature, the text's

Priestley's major argument in the ''Institutes'' was that the only revealed religious truths that could be accepted were those that matched one's experience of the natural world. Because his views of religion were deeply tied to his understanding of nature, the text's theism

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with '' deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred ...

rested on the argument from design

The teleological argument (from ; also known as physico-theological argument, argument from design, or intelligent design argument) is an argument for the existence of God or, more generally, that complex functionality in the natural world wh ...

. The ''Institutes'' shocked and appalled many readers, primarily because it challenged basic Christian orthodoxies, such as the divinity of Christ

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Differ ...

and the miracle of the Virgin Birth. Methodists in Leeds penned a hymn asking God to "the Unitarian fiend expel / And chase his doctrine back to Hell." Priestley wanted to return Christianity to its "primitive" or "pure" form by eliminating the "corruptions" which had accumulated over the centuries. The fourth part of the ''Institutes'', '' An History of the Corruptions of Christianity'', became so long that he was forced to issue it separately in 1782. Priestley believed that the ''Corruptions'' was "the most valuable" work he ever published. In demanding that his readers apply the logic of the emerging sciences and comparative history to the Bible and Christianity, he alienated religious and scientific readers alike—scientific readers did not appreciate seeing science used in the defence of religion and religious readers dismissed the application of science to religion.

Religious controversialist

Priestley engaged in numerous political and religious pamphlet wars. According to Schofield, "he entered each controversy with a cheerful conviction that he was right, while most of his opponents were convinced, from the outset, that he was willfully and maliciously wrong. He was able, then, to contrast his sweet reasonableness to their personal rancor",[Schofield (1997), 181.] but as Schofield points out Priestley rarely altered his opinion as a result of these debates.[ While at Leeds he wrote controversial pamphlets on the Lord's Supper and on Calvinist doctrine; thousands of copies were published, making them some of Priestley's most widely read works.

Priestley founded the '' Theological Repository'' in 1768, a journal committed to the open and rational inquiry of theological questions. Although he promised to print any contribution, only like-minded authors submitted articles. He was therefore obliged to provide much of the journal's content himself (this material became the basis for many of his later theological and metaphysical works). After only a few years, due to a lack of funds, he was forced to cease publishing the journal. He revived it in 1784 with similar results.

]

Defender of Dissenters and political philosopher

Many of Priestley's political writings supported the repeal of the

Many of Priestley's political writings supported the repeal of the Test

Test(s), testing, or TEST may refer to:

* Test (assessment), an educational assessment intended to measure the respondents' knowledge or other abilities

Arts and entertainment

* ''Test'' (2013 film), an American film

* ''Test'' (2014 film), ...

and Corporation Acts, which restricted the rights of Dissenters. They could not hold political office, serve in the armed forces, or attend Oxford and Cambridge unless they subscribed to the Thirty-nine Articles

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (commonly abbreviated as the Thirty-nine Articles or the XXXIX Articles) are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the ...

of the Church of England. Dissenters repeatedly petitioned Parliament to repeal the Acts, arguing that they were being treated as second-class citizens.

Priestley's friends, particularly other Rational Dissenters, urged him to publish a work on the injustices experienced by Dissenters; the result was his '' Essay on the First Principles of Government'' (1768). An early work of modern liberal political theory and Priestley's most thorough treatment of the subject, it—unusually for the time—distinguished political rights from civil rights with precision and argued for expansive civil rights. Priestley identified separate private and public spheres, contending that the government should have control only over the public sphere. Education and religion, in particular, he maintained, were matters of private conscience and should not be administered by the state. Priestley's later radicalism emerged from his belief that the British government was infringing upon these individual freedoms.

Priestley also defended the rights of Dissenters against the attacks of William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, judge and Tory politician of the eighteenth century. He is most noted for writing the ''Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Born into a middle-class family ...

, an eminent legal theorist, whose '' Commentaries on the Laws of England'' (1765–69) had become the standard legal guide. Blackstone's book stated that dissent from the Church of England was a crime and that Dissenters could not be loyal subjects. Furious, Priestley lashed out with his ''Remarks on Dr. Blackstone's Commentaries'' (1769), correcting Blackstone's interpretation of the law, his grammar (a highly politicised subject at the time), and history. Blackstone, chastened, altered subsequent editions of his ''Commentaries'': he rephrased the offending passages and removed the sections claiming that Dissenters could not be loyal subjects, but he retained his description of Dissent as a crime.

Natural philosopher: electricity, ''Optics'', and carbonated water

Although Priestley claimed that

Although Priestley claimed that natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

was only a hobby, he took it seriously. In his ''History of Electricity'', he described the scientist as promoting the "security and happiness of mankind". Priestley's science was eminently practical and he rarely concerned himself with theoretical questions; his model was his clse friend, Benjamin Franklin. When he moved to Leeds, Priestley continued his electrical and chemical experiments (the latter aided by a steady supply of carbon dioxide from a neighbouring brewery). Between 1767 and 1770, he presented five papers to the Royal Society from these initial experiments; the first four papers explored coronal discharge

A corona discharge is an electrical discharge caused by the ionization of a fluid such as air surrounding a conductor carrying a high voltage. It represents a local region where the air (or other fluid) has undergone electrical breakdown ...

s and other phenomena related to electrical discharge, while the fifth reported on the conductivity of charcoals from different sources. His subsequent experimental work focused on chemistry and pneumatics.

Priestley published the first volume of his projected history of experimental philosophy, ''The History and Present State of Discoveries Relating to Vision, Light and Colours'' (referred to as his ''Optics''), in 1772. He paid careful attention to the history of optics and presented excellent explanations of early optics experiments, but his mathematical deficiencies caused him to dismiss several important contemporary theories. He followed the (corpuscular) particle theory of light, influenced by the works of Reverend John Rowning and others. Furthermore, he did not include any of the practical sections that had made his ''History of Electricity'' so useful to practising natural philosophers. Unlike his ''History of Electricity'', it was not popular and had only one edition, although it was the only English book on the topic for 150 years. The hastily written text sold poorly; the cost of researching, writing, and publishing the ''Optics'' convinced Priestley to abandon his history of experimental philosophy.

Priestley was considered for the position of astronomer on James Cook's second voyage to the South Seas, but was not chosen. Still, he contributed in a small way to the voyage: he provided the crew with a method for making carbonated water, which he erroneously speculated might be a cure for scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

. He then published a pamphlet with ''Directions for Impregnating Water with Fixed Air'' (1772). Priestley did not exploit the commercial potential of carbonated water, but others such as made fortunes from it. For his discovery of carbonated water Priestley has been labelled "the father of the soft drink", with the beverage company Schweppes regarding him as “the father of our industry”. In 1773, the Royal Society recognised Priestley's achievements in natural philosophy by awarding him the Copley Medal.Richard Price

Richard Price (23 February 1723 – 19 April 1791) was a British moral philosopher, Nonconformist minister and mathematician. He was also a political reformer, pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the French ...

and Benjamin Franklin, Lord Shelburne wrote to Priestley asking him to direct the education of his children and to act as his general assistant. Although Priestley was reluctant to sacrifice his ministry, he accepted the position, resigning from Mill Hill Chapel on 20 December 1772, and preaching his last sermon on 16 May 1773.

Calne (1773–1780)

In 1773, the Priestleys moved to

In 1773, the Priestleys moved to Calne

Calne () is a town and civil parish in Wiltshire, southwestern England,OS Explorer Map 156, Chippenham and Bradford-on-Avon Scale: 1:25 000.Publisher: Ordnance Survey A2 edition (2007). at the northwestern extremity of the North Wessex Downs ...

in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

, and a year later Lord Shelburne and Priestley took a tour of Europe. According to Priestley's close friend Theophilus Lindsey

Theophilus Lindsey (20 June 1723 O.S.3 November 1808) was an English theologian and clergyman who founded the first avowedly Unitarian congregation in the country, at Essex Street Chapel.

Early life

Lindsey was born in Middlewich, Cheshire, ...

, Priestley was "much improved by this view of mankind at large". Upon their return, Priestley easily fulfilled his duties as librarian and tutor. The workload was intentionally light, allowing him time to pursue his scientific investigations and theological interests. Priestley also became a political adviser to Shelburne, gathering information on parliamentary issues and serving as a liaison between Shelburne and the Dissenting and American interests. When the Priestleys' third son was born on 24 May 1777, they named him Henry at the lord's request.

Materialist philosopher

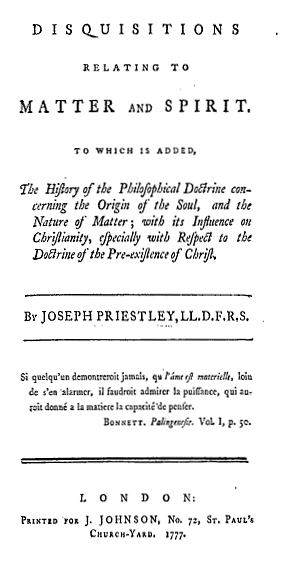

Priestley wrote his most important philosophical works during his years with Lord Shelburne. In a series of major metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

texts published between 1774 and 1780—''An Examination of Dr. Reid's Inquiry into the Human Mind'' (1774), ''Hartley's Theory of the Human Mind on the Principle of the Association of Ideas'' (1775), ''Disquisitions relating to Matter and Spirit'' (1777), ''The Doctrine of Philosophical Necessity Illustrated'' (1777), and ''Letters to a Philosophical Unbeliever'' (1780)—he argues for a philosophy that incorporates four concepts: determinism, materialism, causality, causation, and necessitarianism. By studying the natural world, he argued, people would learn how to become more compassionate, happy, and prosperous.

Priestley strongly suggested that there is no Dualism (philosophy of mind), mind-body duality, and put forth a materialist philosophy in these works; that is, one founded on the principle that everything in the universe is made of matter that we can perceive. He also contended that discussing the soul is impossible because it is made of a divine substance, and humanity cannot perceive the divine. Despite his separation of the divine from the mortal, this position shocked and angered many of his readers, who believed that such a duality was necessary for the Soul (spirit), soul to exist.

Responding to Baron d'Holbach's ''The System of Nature, Système de la Nature'' (1770) and David Hume's ''Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion'' (1779) as well as the works of the French ''philosophers'', Priestley maintained that materialism and determinism could be reconciled with a belief in God. He criticised those whose faith was shaped by books and fashion, drawing an analogy between the scepticism of educated men and the credulity of the masses.

Maintaining that humans had no free will, Priestley argued that what he called "philosophical necessity" (akin to absolute determinism) is consonant with Christianity, a position based on his understanding of the natural world. Like the rest of nature, man's mind is subject to the laws of causation, Priestley contended, but because a benevolent God created these laws, the world and the people in it will eventually be perfected. Evil is therefore only an imperfect understanding of the world.

Although Priestley's philosophical work has been characterised as "audacious and original",

Priestley strongly suggested that there is no Dualism (philosophy of mind), mind-body duality, and put forth a materialist philosophy in these works; that is, one founded on the principle that everything in the universe is made of matter that we can perceive. He also contended that discussing the soul is impossible because it is made of a divine substance, and humanity cannot perceive the divine. Despite his separation of the divine from the mortal, this position shocked and angered many of his readers, who believed that such a duality was necessary for the Soul (spirit), soul to exist.

Responding to Baron d'Holbach's ''The System of Nature, Système de la Nature'' (1770) and David Hume's ''Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion'' (1779) as well as the works of the French ''philosophers'', Priestley maintained that materialism and determinism could be reconciled with a belief in God. He criticised those whose faith was shaped by books and fashion, drawing an analogy between the scepticism of educated men and the credulity of the masses.

Maintaining that humans had no free will, Priestley argued that what he called "philosophical necessity" (akin to absolute determinism) is consonant with Christianity, a position based on his understanding of the natural world. Like the rest of nature, man's mind is subject to the laws of causation, Priestley contended, but because a benevolent God created these laws, the world and the people in it will eventually be perfected. Evil is therefore only an imperfect understanding of the world.

Although Priestley's philosophical work has been characterised as "audacious and original",[ it partakes of older philosophical traditions on the problems of free will, determinism, and materialism.][McEvoy and McGuire, 341–45.] For example, the 17th-century philosopher Baruch Spinoza argued for absolute determinism and absolute materialism. Like Spinoza and Priestley,

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Leibniz argued that human will was completely determined by natural laws;[

Adams, Robert Merrihew. ''Leibniz: Determinist, Theist, Idealist''. New York: Oxford University Press (1998), 10–13, 1–20, 41–44. .]

unlike them, Leibniz argued for a "parallel universe" of immaterial objects (such as human souls) so arranged by God that its outcomes agree exactly with those of the material universe.

Leibniz

and Priestley

share an optimism that God has chosen the chain of events benevolently; however, Priestley believed that the events were leading to a glorious millennial conclusion,[ whereas for Leibniz the entire chain of events was optimal in and of itself, as compared with other conceivable chains of events.

]

Founder of British Unitarianism

When Priestley's friend Theophilus Lindsey

Theophilus Lindsey (20 June 1723 O.S.3 November 1808) was an English theologian and clergyman who founded the first avowedly Unitarian congregation in the country, at Essex Street Chapel.

Early life

Lindsey was born in Middlewich, Cheshire, ...

decided to found a new Christian denomination that would not restrict its members' beliefs, Priestley and others hurried to his aid. On 17 April 1774, Lindsey held the first Unitarianism, Unitarian service in Britain, at the newly formed Essex Street Chapel in London; he had even designed his own liturgy, of which many were critical. Priestley defended his friend in the pamphlet ''Letter to a Layman, on the Subject of the Rev. Mr. Lindsey's Proposal for a Reformed English Church'' (1774), claiming that only the form of worship had been altered, not its substance, and attacking those who followed religion as a fashion. Priestley attended Lindsey's church regularly in the 1770s and occasionally preached there. He continued to support institutionalised Unitarianism for the rest of his life, writing several ''Defenses'' of Unitarianism and encouraging the foundation of new Unitarian chapels throughout Britain and the United States.

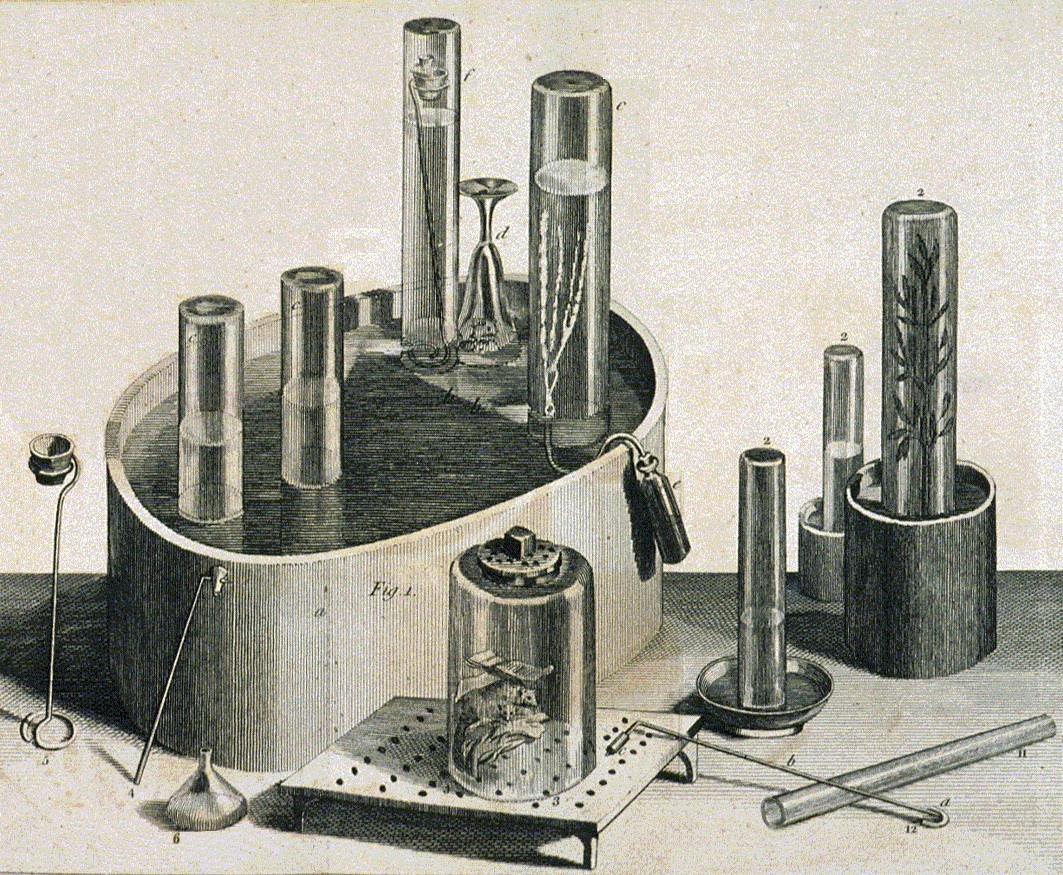

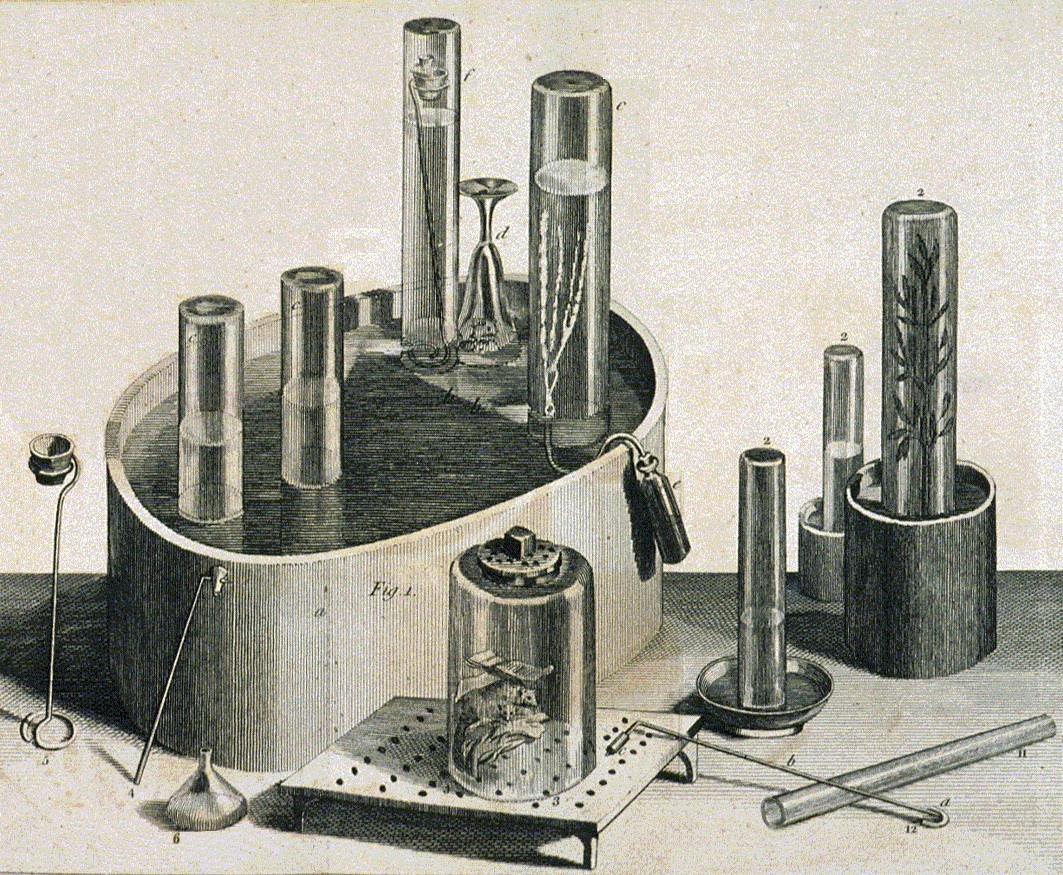

Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air

Priestley's years in Calne were the only ones in his life dominated by scientific investigations; they were also the most scientifically fruitful. His experiments were almost entirely confined to "airs", and out of this work emerged his most important scientific texts: the six volumes of ''Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air'' (1774–86). These experiments helped repudiate the last vestiges of the Classical element, theory of four elements, which Priestley attempted to replace with his own variation of phlogiston theory

The phlogiston theory is a superseded scientific theory that postulated the existence of a fire-like element called phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burni ...

. According to that 18th-century theory, the combustion or redox, oxidation of a substance corresponded to the release of a material substance, ''phlogiston''.

Priestley's work on "airs" is not easily classified. As historian of science Simon Schaffer writes, it "has been seen as a branch of physics, or chemistry, or natural philosophy, or some highly idiosyncratic version of Priestley's own invention". Furthermore, the volumes were both a scientific and a political enterprise for Priestley, in which he argues that science could destroy "undue and usurped authority" and that government has "reason to tremble even at an air pump or an electrical machine".

Volume I of ''Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air'' outlined several discoveries: "nitrous air" (nitric oxide, NO); "vapor of spirit of salt", later called "acid air" or "marine acid air" (anhydrous hydrochloric acid, HCl); "alkaline air" (ammonia, NH3); "diminished" or "dephlogisticated nitrous air" (nitrous oxide, N2O); and, most famously, "dephlogisticated air" (oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

, O2) as well as experimental findings that showed plants revitalised enclosed volumes of air, a discovery that would eventually lead to the discovery of photosynthesis. Priestley also developed a "nitrous air test" to determine the "goodness of air". Using a pneumatic trough, he would mix nitrous air with a test sample, over water or mercury, and measure the decrease in volume—the principle of eudiometer, eudiometry.[Fruton, 20, 29] After a small history of the study of airs, he explained his own experiments in an open and sincere style. As an early biographer writes, "whatever he knows or thinks he tells: doubts, perplexities, blunders are set down with the most refreshing candour." Priestley also described his cheap and easy-to-assemble experimental apparatus; his colleagues therefore believed that they could easily reproduce his experiments. Faced with inconsistent experimental results, Priestley employed phlogiston theory. This led him to conclude that there were only three types of "air": "fixed", "alkaline", and "acid". Priestley dismissed the History of chemistry#17th and 18th centuries: Early chemistry, burgeoning chemistry of his day. Instead, he focused on gases and "changes in their sensible properties", as had natural philosophers before him. He isolated carbon monoxide (CO), but apparently did not realise that it was a separate "air".

Discovery of oxygen

In August 1774 he isolated an "air" that appeared to be completely new, but he did not have an opportunity to pursue the matter because he was about to tour Europe with Shelburne. While in Paris, Priestley replicated the experiment for others, including French chemist Antoine Lavoisier. After returning to Britain in January 1775, he continued his experiments and discovered "vitriolic acid air" (sulphur dioxide, SO2).

In March he wrote to several people regarding the new "air" that he had discovered in August. One of these letters was read aloud to the Royal Society, and a paper outlining the discovery, titled "An Account of further Discoveries in Air", was published in the Society's journal ''Philosophical Transactions''. Priestley called the new substance "dephlogisticated air", which he made in the famous experiment by burning glass, focusing the sun's rays on a sample of mercuric oxide. He first tested it on mice, who surprised him by surviving quite a while entrapped with the air, and then on himself, writing that it was "five or six times better than common air for the purpose of respiration, inflammation, and, I believe, every other use of common atmospherical air". He had discovered

In August 1774 he isolated an "air" that appeared to be completely new, but he did not have an opportunity to pursue the matter because he was about to tour Europe with Shelburne. While in Paris, Priestley replicated the experiment for others, including French chemist Antoine Lavoisier. After returning to Britain in January 1775, he continued his experiments and discovered "vitriolic acid air" (sulphur dioxide, SO2).

In March he wrote to several people regarding the new "air" that he had discovered in August. One of these letters was read aloud to the Royal Society, and a paper outlining the discovery, titled "An Account of further Discoveries in Air", was published in the Society's journal ''Philosophical Transactions''. Priestley called the new substance "dephlogisticated air", which he made in the famous experiment by burning glass, focusing the sun's rays on a sample of mercuric oxide. He first tested it on mice, who surprised him by surviving quite a while entrapped with the air, and then on himself, writing that it was "five or six times better than common air for the purpose of respiration, inflammation, and, I believe, every other use of common atmospherical air". He had discovered oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

gas (O2).

Priestley assembled his oxygen paper and several others into a second volume of ''Experiments and Observations on Air'', published in 1776. He did not emphasise his discovery of "dephlogisticated air" (leaving it to Part III of the volume) but instead argued in the preface how important such discoveries were to rational religion. His paper narrated the discovery chronologically, relating the long delays between experiments and his initial puzzlements; thus, it is difficult to determine when exactly Priestley "discovered" oxygen. Such dating is significant as both Lavoisier and Swedish pharmacist Carl Wilhelm Scheele have strong claims to the discovery of oxygen as well, Scheele having been the first to isolate the gas (although he published after Priestley) and Lavoisier having been the first to describe it as purified "air itself entire without alteration" (that is, the first to explain oxygen without phlogiston theory).

In his paper "Observations on Respiration and the Use of the Blood", Priestley was the first to suggest a connection between blood and air, although he did so using

Priestley assembled his oxygen paper and several others into a second volume of ''Experiments and Observations on Air'', published in 1776. He did not emphasise his discovery of "dephlogisticated air" (leaving it to Part III of the volume) but instead argued in the preface how important such discoveries were to rational religion. His paper narrated the discovery chronologically, relating the long delays between experiments and his initial puzzlements; thus, it is difficult to determine when exactly Priestley "discovered" oxygen. Such dating is significant as both Lavoisier and Swedish pharmacist Carl Wilhelm Scheele have strong claims to the discovery of oxygen as well, Scheele having been the first to isolate the gas (although he published after Priestley) and Lavoisier having been the first to describe it as purified "air itself entire without alteration" (that is, the first to explain oxygen without phlogiston theory).

In his paper "Observations on Respiration and the Use of the Blood", Priestley was the first to suggest a connection between blood and air, although he did so using phlogiston theory

The phlogiston theory is a superseded scientific theory that postulated the existence of a fire-like element called phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burni ...

. In typical Priestley fashion, he prefaced the paper with a history of the study of respiration. A year later, clearly influenced by Priestley, Lavoisier was also discussing respiration at the French Academy of Sciences, Académie des sciences. Lavoisier's work began the long train of discovery that produced papers on oxygen respiration and culminated in the overthrow of phlogiston theory and the establishment of modern chemistry.

Around 1779 Priestley and Shelburne – soon to be the Marquess of Lansdowne, 1st Marquess of Landsdowne – had a rupture, the precise reasons for which remain unclear. Shelburne blamed Priestley's health, while Priestley claimed Shelburne had no further use for him. Some contemporaries speculated that Priestley's outspokenness had hurt Shelburne's political career. Schofield argues that the most likely reason was Shelburne's recent marriage to Louisa Fitzpatrick—apparently, she did not like the Priestleys. Although Priestley considered moving to America, he eventually accepted Birmingham New Meeting's offer to be their minister.

Both Priestley and Shelburne's families upheld their Unitarian faith for generations.

In December 2013, it was reported that Sir Christopher Bullock – a direct descendant of Shelburne's brother, Thomas Fitzmaurice (MP) – had married his wife, Lupton family, Lady Bullock, née Barbara May Lupton, at London's Unitarian Essex Street Chapel, Essex Church in 1917. Barbara Lupton was the second cousin of Family of Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, Olive Middleton, née Lupton, the great-grandmother of Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge. In 1914, Olive and Noel Middleton had married at Leeds' Mill Hill Chapel

Mill Hill Chapel is a Unitarian church in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It is a member of the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches, the umbrella organisation for British Unitarians. The building, which stands in the centr ...

, which Priestley, as its minister, had once guided towards Unitarianism.

Birmingham (1780–1791)

In 1780 the Priestleys moved to Birmingham and spent a happy decade surrounded by old friends, until they were forced to flee in 1791 by religiously motivated mob violence in what became known as the Priestley Riots. Priestley accepted the ministerial position at New Meeting on the condition that he be required to preach and teach only on Sundays, so that he would have time for his writing and scientific experiments. As in Leeds, Priestley established classes for the youth of his parish and by 1781, he was teaching 150 students. Because Priestley's New Meeting salary was only 100 Guinea (British coin), guineas, friends and patrons donated money and goods to help continue his investigations. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1782.

Chemical Revolution

Many of the friends that Priestley made in Birmingham were members of the Lunar Society, a group of manufacturers, inventors, and natural philosophers who assembled monthly to discuss their work. The core of the group included men such as the manufacturer Matthew Boulton, the chemist and geologist James Keir, the inventor and engineer James Watt, and the botanist, chemist, and geologist William Withering. Priestley was asked to join this unique society and contributed much to the work of its members. As a result of this stimulating intellectual environment, he published several important scientific papers, including "Experiments relating to Phlogiston, and the seeming Conversion of Water into Air" (1783). The first part attempts to refute Lavoisier's challenges to his work on oxygen; the second part describes how steam is "converted" into air. After several variations of the experiment, with different substances as fuel and several different collecting apparatuses (which produced different results), he concluded that air could travel through more substances than previously surmised, a conclusion "contrary to all the known principles of hydrostatics". This discovery, along with his earlier work on what would later be recognised as gaseous diffusion, would eventually lead John Dalton and Thomas Graham (chemist), Thomas Graham to formulate the kinetic theory of gases.

In 1777, Antoine Lavoisier had written ''Mémoire sur la combustion en général'', the first of what proved to be a series of attacks on phlogiston theory; it was against these attacks that Priestley responded in 1783. While Priestley accepted parts of Lavoisier's theory, he was unprepared to assent to the major revolutions Lavoisier proposed: the overthrow of phlogiston, a chemistry based conceptually on Chemical element, elements and Chemical compound, compounds, and a new International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry nomenclature, chemical nomenclature. Priestley's original experiments on "dephlogisticated air" (oxygen), combustion, and water provided Lavoisier with the data he needed to construct much of his system; yet Priestley never accepted Lavoisier's new theories and continued to defend phlogiston theory for the rest of his life. Lavoisier's system was based largely on the ''quantitative'' concept that mass is neither created nor destroyed in chemical reactions (i.e., the conservation of mass). By contrast, Priestley preferred to observe ''qualitative'' changes in heat, color, and particularly volume. His experiments tested "airs" for "their solubility in water, their power of supporting or extinguishing flame, whether they were respirable, how they behaved with acid and alkaline air, and with nitric oxide and inflammable air, and lastly how they were affected by the electric spark."

Many of the friends that Priestley made in Birmingham were members of the Lunar Society, a group of manufacturers, inventors, and natural philosophers who assembled monthly to discuss their work. The core of the group included men such as the manufacturer Matthew Boulton, the chemist and geologist James Keir, the inventor and engineer James Watt, and the botanist, chemist, and geologist William Withering. Priestley was asked to join this unique society and contributed much to the work of its members. As a result of this stimulating intellectual environment, he published several important scientific papers, including "Experiments relating to Phlogiston, and the seeming Conversion of Water into Air" (1783). The first part attempts to refute Lavoisier's challenges to his work on oxygen; the second part describes how steam is "converted" into air. After several variations of the experiment, with different substances as fuel and several different collecting apparatuses (which produced different results), he concluded that air could travel through more substances than previously surmised, a conclusion "contrary to all the known principles of hydrostatics". This discovery, along with his earlier work on what would later be recognised as gaseous diffusion, would eventually lead John Dalton and Thomas Graham (chemist), Thomas Graham to formulate the kinetic theory of gases.

In 1777, Antoine Lavoisier had written ''Mémoire sur la combustion en général'', the first of what proved to be a series of attacks on phlogiston theory; it was against these attacks that Priestley responded in 1783. While Priestley accepted parts of Lavoisier's theory, he was unprepared to assent to the major revolutions Lavoisier proposed: the overthrow of phlogiston, a chemistry based conceptually on Chemical element, elements and Chemical compound, compounds, and a new International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry nomenclature, chemical nomenclature. Priestley's original experiments on "dephlogisticated air" (oxygen), combustion, and water provided Lavoisier with the data he needed to construct much of his system; yet Priestley never accepted Lavoisier's new theories and continued to defend phlogiston theory for the rest of his life. Lavoisier's system was based largely on the ''quantitative'' concept that mass is neither created nor destroyed in chemical reactions (i.e., the conservation of mass). By contrast, Priestley preferred to observe ''qualitative'' changes in heat, color, and particularly volume. His experiments tested "airs" for "their solubility in water, their power of supporting or extinguishing flame, whether they were respirable, how they behaved with acid and alkaline air, and with nitric oxide and inflammable air, and lastly how they were affected by the electric spark."

By 1789, when Lavoisier published his ''Traité Élémentaire de Chimie'' and founded the ''Annales de Chimie'', the new chemistry had come into its own. Priestley published several more scientific papers in Birmingham, the majority attempting to refute Lavoisier. Priestley and other Lunar Society members argued that the new French system was too expensive, too difficult to test, and unnecessarily complex. Priestley in particular rejected its "establishment" aura. In the end, Lavoisier's view prevailed: his new chemistry introduced many of the principles on which chemistry, modern chemistry is founded.

Priestley's refusal to accept Lavoisier's "new chemistry"—such as the conservation of mass—and his determination to adhere to a less satisfactory theory has perplexed many scholars. Schofield explains it thus: "Priestley was never a chemist; in a modern, and even a Lavoisierian, sense, he was never a scientist. He was a natural philosopher, concerned with the economy of nature and obsessed with an idea of unity, in theology and in nature." Historian of science John McEvoy largely agrees, writing that Priestley's view of nature as coextensive with God and thus infinite, which encouraged him to focus on facts over hypotheses and theories, prompted him to reject Lavoisier's system. McEvoy argues that "Priestley's isolated and lonely opposition to the oxygen theory was a measure of his passionate concern for the principles of intellectual freedom, epistemic equality and critical inquiry." Priestley himself claimed in the last volume of ''Experiments and Observations'' that his most valuable works were his theological ones because they were "superior [in] dignity and importance".

By 1789, when Lavoisier published his ''Traité Élémentaire de Chimie'' and founded the ''Annales de Chimie'', the new chemistry had come into its own. Priestley published several more scientific papers in Birmingham, the majority attempting to refute Lavoisier. Priestley and other Lunar Society members argued that the new French system was too expensive, too difficult to test, and unnecessarily complex. Priestley in particular rejected its "establishment" aura. In the end, Lavoisier's view prevailed: his new chemistry introduced many of the principles on which chemistry, modern chemistry is founded.

Priestley's refusal to accept Lavoisier's "new chemistry"—such as the conservation of mass—and his determination to adhere to a less satisfactory theory has perplexed many scholars. Schofield explains it thus: "Priestley was never a chemist; in a modern, and even a Lavoisierian, sense, he was never a scientist. He was a natural philosopher, concerned with the economy of nature and obsessed with an idea of unity, in theology and in nature." Historian of science John McEvoy largely agrees, writing that Priestley's view of nature as coextensive with God and thus infinite, which encouraged him to focus on facts over hypotheses and theories, prompted him to reject Lavoisier's system. McEvoy argues that "Priestley's isolated and lonely opposition to the oxygen theory was a measure of his passionate concern for the principles of intellectual freedom, epistemic equality and critical inquiry." Priestley himself claimed in the last volume of ''Experiments and Observations'' that his most valuable works were his theological ones because they were "superior [in] dignity and importance".

Defender of English Dissenters and French revolutionaries