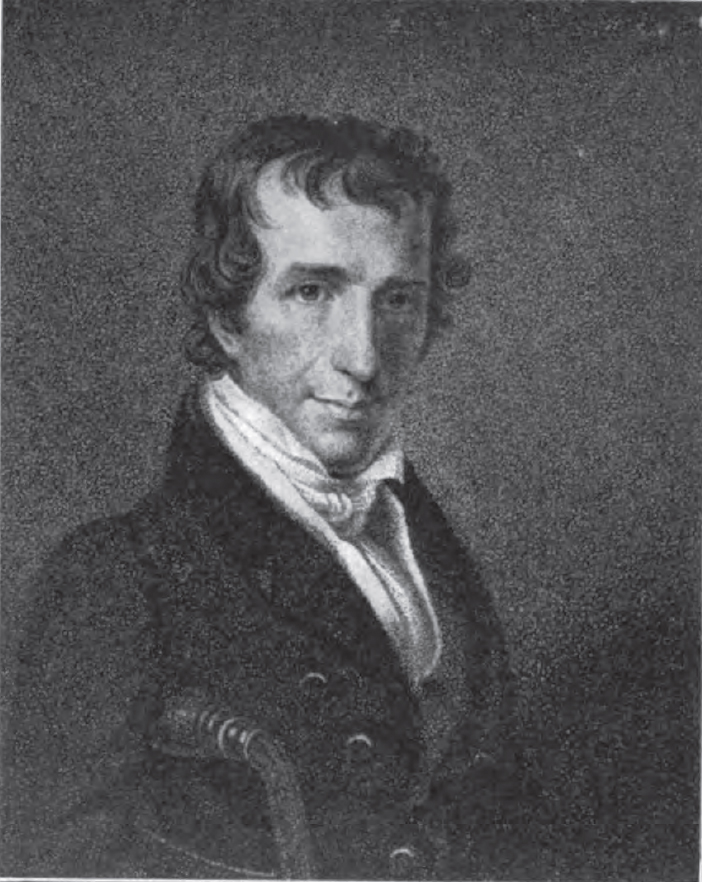

John Rowan (Kentucky) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Rowan (July 12, 1773July 13, 1843) was a 19th-century politician and jurist from the

How the matter escalated to a duel is also the subject of some uncertainty. In his biography of Benjamin Hardin, Lucious P. Little recounts that Chambers immediately challenged Rowan to a duel.Little, p. 178 According to Little, Rowan, embarrassed at his behavior, refused the challenge and repeatedly apologized for his actions, but Chambers was insistent on the duel and continued hurling insults of growing severity at Rowan until Rowan accepted the challenge. A letter from George M. Bibb, published a year after the event and reprinted in 1912 in the ''Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society'', claims that Chambers' challenge was issued through a letter delivered to Rowan by Chambers' friend, Major John Bullock, on January 31, 1801.Johnston, p. 28 Bibb claims that he and Rowan had, after the night of the incident, gone to nearby Bullitt County on business, that Rowan had returned first, and that Rowan showed Bibb the letter upon his return on February 1.

Bullock served as Chambers' second for the duel; Bibb acted as second for Rowan. According to Bibb, he and Bullock met on February 1 to discuss the parameters for the duel. Bullock proposed that the matter be dropped, but Bibb insisted that Chambers would have to retract his challenge, to which Bullock would not consent. The duel was held February 3, 1801, near Bardstown. Both combatants missed with their first shots. Both men fired again, and Rowan's second shot struck Chambers, wounding him severely. (Bibb's account says that Chambers was struck in the left side; other accounts state that the shot hit Chambers in the chest.) Rowan then offered his carriage to take Chambers to town for medical attention, and Chambers asked that Rowan not be prosecuted.Hibbs, p. 27 Despite medical aid, Chambers died the following day.

Public sentiment was against Rowan in the matter of his duel with Chambers. Soon after the duel, friends of Chambers formed a

How the matter escalated to a duel is also the subject of some uncertainty. In his biography of Benjamin Hardin, Lucious P. Little recounts that Chambers immediately challenged Rowan to a duel.Little, p. 178 According to Little, Rowan, embarrassed at his behavior, refused the challenge and repeatedly apologized for his actions, but Chambers was insistent on the duel and continued hurling insults of growing severity at Rowan until Rowan accepted the challenge. A letter from George M. Bibb, published a year after the event and reprinted in 1912 in the ''Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society'', claims that Chambers' challenge was issued through a letter delivered to Rowan by Chambers' friend, Major John Bullock, on January 31, 1801.Johnston, p. 28 Bibb claims that he and Rowan had, after the night of the incident, gone to nearby Bullitt County on business, that Rowan had returned first, and that Rowan showed Bibb the letter upon his return on February 1.

Bullock served as Chambers' second for the duel; Bibb acted as second for Rowan. According to Bibb, he and Bullock met on February 1 to discuss the parameters for the duel. Bullock proposed that the matter be dropped, but Bibb insisted that Chambers would have to retract his challenge, to which Bullock would not consent. The duel was held February 3, 1801, near Bardstown. Both combatants missed with their first shots. Both men fired again, and Rowan's second shot struck Chambers, wounding him severely. (Bibb's account says that Chambers was struck in the left side; other accounts state that the shot hit Chambers in the chest.) Rowan then offered his carriage to take Chambers to town for medical attention, and Chambers asked that Rowan not be prosecuted.Hibbs, p. 27 Despite medical aid, Chambers died the following day.

Public sentiment was against Rowan in the matter of his duel with Chambers. Soon after the duel, friends of Chambers formed a

Rowan often found himself in demand as an orator and host. In February 1818, he was chosen to eulogize his close friend, George Rogers Clark. In June 1819, the citizens of Louisville chose him as their official host for a visiting party that included

Rowan often found himself in demand as an orator and host. In February 1818, he was chosen to eulogize his close friend, George Rogers Clark. In June 1819, the citizens of Louisville chose him as their official host for a visiting party that included

Meanwhile, Rowan, who espoused the Relief position, was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1822 representing

Meanwhile, Rowan, who espoused the Relief position, was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1822 representing

After his service in the Senate, Rowan returned to Kentucky, dividing his time between Louisville and Bardstown. During an epidemic of cholera that spread through Bardstown in 1833, three of Rowan's children (William, Atkinson, and Mary Jane) died. The spouses of William and Mary Jane also died of cholera, as did Mary Jane's daughter, and Rowan's sister Elizabeth and her husband.Capps, p. 21 Aid from Bishop Joseph Flaget and a group of nuns who traveled to Federal Hill during the epidemic probably spared the life of Rowan's orphaned granddaughter, Eliza Rowan Harney.

In 1836, Rowan and two other men founded the Louisville Medical Institute, the forerunner of the

After his service in the Senate, Rowan returned to Kentucky, dividing his time between Louisville and Bardstown. During an epidemic of cholera that spread through Bardstown in 1833, three of Rowan's children (William, Atkinson, and Mary Jane) died. The spouses of William and Mary Jane also died of cholera, as did Mary Jane's daughter, and Rowan's sister Elizabeth and her husband.Capps, p. 21 Aid from Bishop Joseph Flaget and a group of nuns who traveled to Federal Hill during the epidemic probably spared the life of Rowan's orphaned granddaughter, Eliza Rowan Harney.

In 1836, Rowan and two other men founded the Louisville Medical Institute, the forerunner of the

U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sove ...

of Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

. Rowan's family moved from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

to the Kentucky frontier when he was young. From there, they moved to Bardstown, Kentucky

Bardstown is a home rule-class city in Nelson County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 11,700 in the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Nelson County.

Bardstown is named for the pioneering Bard brothers. David Bard obtained a l ...

, where Rowan studied law with former Kentucky Attorney General

The Attorney General of Kentucky is an office created by the Kentucky Constitution. (Ky.Const. § 91). Under Kentucky law, they serve several roles, including the state's chief prosecutor (KRS 15.700), the state's chief law enforcement officer (K ...

George Nicholas. He was a representative to the state constitutional convention of 1799, but his promising political career was almost derailed when he killed a man in a duel stemming from a drunken dispute during a game of cards. Although public sentiment was against him, a judge found insufficient evidence against him to convict him of murder. In 1804, Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Christopher Greenup

Christopher Greenup (c. 1750 – April 27, 1818) was an American politician who served as a U.S. Representative and the third Governor of Kentucky. Little is known about his early life; the first reliable records about him are documents recordi ...

appointed Rowan Secretary of State, and he went on to serve in the Kentucky House of Representatives and the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

.

In 1819, Rowan was appointed to the Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky.

Th ...

, serving until his resignation 1821. He was again elected to the state legislature in 1823. With the state reeling from the Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic ...

, Rowan became the leader of a group of legislators dedicated to enacting laws favorable to the state's large debtor class. He believed the will of the people was sovereign and roundly denounced the Court of Appeals for striking down debt relief legislation as unconstitutional. He led the effort to impeach the offending justices, and when that effort failed, spearheaded a movement to abolish the court entirely and replace it with a new one, touching off the Old Court – New Court controversy

The Old Court – New Court controversy was a 19th-century political controversy in the U.S. state of Kentucky in which the Kentucky General Assembly abolished the Kentucky Court of Appeals and replaced it with a new court. The justices of the o ...

. New Court partisans in the legislature elected Rowan to the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

in 1824. During his term, the nascent Whig Party ascended to power in the state legislature, and at the expiration of his term in 1831, the Whigs replaced him with party founder Henry Clay.

After his term in the Senate, Rowan returned to Kentucky, where he served as the first president of the Louisville Medical Institute and the Kentucky Historical Society

The Kentucky Historical Society (KHS) was originally established in 1836 as a private organization. It is an agency of the Kentucky state government that records and preserves important historical documents, buildings, and artifacts of Kentucky's ...

. In 1840, he was appointed to a commission to prosecute land claims of U.S. citizens against the Republic of Mexico

Mexico ( Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guate ...

, but resigned his commission in 1842 because of failing health. He died July 13, 1843 and was buried on the grounds of Federal Hill, his estate in Bardstown. According to tradition, Stephen Collins Foster, a distant relative of Rowan's, was inspired to write the ballad ''My Old Kentucky Home

"My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!" is a sentimental ballad written by Stephen Foster, probably composed in 1852. It was published in January 1853 by Firth, Pond, & Co. of New York. Foster was likely inspired by Harriet Beecher Stowe's anti-sla ...

'' after a visit to Federal Hill in 1852, but later historians have been unable to conclude whether or not Foster ever visited the mansion at all. The mansion is now owned by the state of Kentucky and forms the centerpiece of My Old Kentucky Home State Park

My Old Kentucky Home State Park is a state park located in Bardstown, Kentucky, United States. The park's centerpiece is Federal Hill, a former plantation home owned by United States Senator John Rowan in 1795. During the Rowan family's occupat ...

.

Early life and family

John Rowan was born July 12, 1773, nearYork

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

in the Province of Pennsylvania."Rowan, John". ''Biographical Directory of the United States Congress'' He was third of five children born to Captain William and Sarah Elizabeth "Eliza" (Cooper) Rowan.Capps, p. 1 His siblings included two older brothers – Andrew and Stephen – and two younger sisters – Elizabeth and Alice. Captain Rowan served in the 4th York Battery during the Revolutionary War, and after the war, he was elected to three consecutive terms as sheriff of York County.

Having exhausted most of his resources in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

helping establish the new United States government, Captain Rowan decided to move the family to the western frontier, where he hoped to start fresh and rebuild his fortune. On October 10, 1783, the Rowans and five other families embarked on a flat bottomed boat near Redstone Creek and began their journey down the Monongahela River

The Monongahela River ( , )—often referred to locally as the Mon ()—is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed August 15, 2011 river on the Allegheny Plateau in north-cen ...

toward the Falls of the Ohio

The Falls of the Ohio National Wildlife Conservation Area is a national, bi-state area on the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky in the United States, administered by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Federal status was awarded in 1981. The fa ...

. The travelers expected the journey to last a few days at most, but ice along the river slowed the journey, and a lack of provisions exacerbated the delays. Three of the families disembarked near what is now Maysville, Kentucky

Maysville is a home rule-class city in Mason County, Kentucky, United States and is the seat of Mason County. The population was 8,782 as of 2019, making it the 51st-largest city in Kentucky by population. Maysville is on the Ohio River, north ...

; the Rowans would later learn that most of these settlers were killed by Indians.Capps, p. 2 The remaining settlers continued downriver, reaching Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

on March 10, 1783.

In April 1784, the Rowans and five other families set out for a tract of land on the Long Falls of the Green River Green River may refer to:

Rivers

Canada

* Green River (British Columbia), a tributary of the Lillooet River

*Green River, a tributary of the Saint John River, also known by its French name of Rivière Verte

*Green River (Ontario), a tributary of ...

that Rowan had purchased before leaving Pennsylvania. The party arrived on May 11, 1784, and constructed a fort which they dubbed Fort Vienna.Capps, p. 3 The fort, then located approximately 100 miles from the nearest white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

settlement, is the present-day town of Calhoun

John C. Calhoun (1782–1850) was the 7th vice president of the United States.

Calhoun can also refer to:

Surname

* Calhoun (surname)

Inhabited places in the United States

*Calhoun, Georgia

*Calhoun, Illinois

* Calhoun, Kansas

* Calhoun, Kentuc ...

.''Biographical Cyclopedia'', p. 272Connelley and Coulter, p. 596 The settlers at Fort Vienna frequently clashed with the Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

who used the area as a hunting ground. The Rowans would remain at Fort Vienna for six years.

Concerned for the education of his children, Captain Rowan moved the family to Bardstown, Kentucky

Bardstown is a home rule-class city in Nelson County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 11,700 in the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Nelson County.

Bardstown is named for the pioneering Bard brothers. David Bard obtained a l ...

in 1790. There, John Rowan began his education under Dr. James Priestly at Salem Academy.Kleber, "Rowan, John", p. 783 Salem Academy was, at the time, considered one of the best educational institutions in the west.Capps, p. 4 Among Rowan's classmates at the Academy were future U.S. Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

Felix Grundy

Felix Grundy (September 11, 1777 – December 19, 1840) was an American politician who served as a congressman and senator from Tennessee as well as the 13th attorney General of the United States.

Biography

Early life

Born in Berkeley Cou ...

, future U.S. Senator John Pope, future U.S. District Attorney

United States attorneys are officials of the U.S. Department of Justice who serve as the chief federal law enforcement officers in each of the 94 U.S. federal judicial districts. Each U.S. attorney serves as the United States' chief federal c ...

Joseph Hamilton Daveiss

Major Joseph Hamilton Daveiss (; March 4, 1774 – November 7, 1811), a Virginia-born lawyer, received a mortal wound while commanding the Dragoons of the Kentucky Militia at the Battle of Tippecanoe. Five years earlier, Daviess had tried to warn ...

, and future Kentucky state senator John Allen. Rowan and Grundy were members of a debating society called the Bardstown Pleiades which may have been an outgrowth of Salem Academy.Capps, p. 27 Other notable members of the society included future Florida Governor

The governor of Florida is the head of government of the state of Florida and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor has a duty to enforce state laws and the power to either approve or veto bills passed by the Florida ...

William Pope Duval

William Pope Duval (September 4, 1784 – March 19, 1854) was the first civilian governor of the Florida Territory, succeeding Andrew Jackson, who had been a military governor. In his twelve-year governorship, from 1822 to 1834, he divided Florid ...

, future U.S. Postmaster General and Kentucky Governor Charles A. Wickliffe, and future Kentucky Senator Benjamin Hardin

Benjamin Hardin (February 29, 1784 – September 24, 1852) was a United States representative from Kentucky. Martin Davis Hardin was his cousin. He was born at the Georges Creek settlement on the Monongahela River, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvan ...

.

Completing his studies in 1793, Rowan moved to Lexington, Kentucky and read law under former Kentucky Attorney General

The Attorney General of Kentucky is an office created by the Kentucky Constitution. (Ky.Const. § 91). Under Kentucky law, they serve several roles, including the state's chief prosecutor (KRS 15.700), the state's chief law enforcement officer (K ...

George Nicholas. He was admitted to the bar

An admission to practice law is acquired when a lawyer receives a license to practice law. In jurisdictions with two types of lawyer, as with barristers and solicitors, barristers must gain admission to the bar whereas for solicitors there are dist ...

in May 1795 and commenced practice in Louisville.Allen, p. 350 Rowan struggled financially during his early years as a lawyer. Nelson County judge Atkinson Hill took an interest in Rowan, furnishing him with money to expand his law library and taking him as a business partner. In order to earn some money, Rowan accepted an appointment as a public prosecutor, but after securing a felony conviction against a young man in his first case, he was so troubled that he resigned the office and resolved never again to play the role of prosecutor. For the remainder of his career, he always represented defendants.Little, p. 177 An advocate of education, Rowan allowed several prominent young law students to study in his office, including future U.S. Treasury Secretary James Guthrie, future Supreme Court Justice

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest-ranking judicial body in the United States. Its membership, as set by the Judiciary Act of 1869, consists of the chief justice of the United States and eight Associate Justice of the Supreme ...

John McKinley

John McKinley (May 1, 1780 – July 19, 1852) was a United States Senator from the state of Alabama and an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Early life

McKinley was born in Culpeper County, Virginia, on May 1, ...

, and future Kentucky Governor

The governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the head of government of Kentucky. Sixty-two men and one woman have served as governor of Kentucky. The governor's term is four years in length; since 1992, incumbents have been able to seek re-el ...

Lazarus W. Powell.Capps, p. 10

Rowan married Anne Lytle on October 29, 1794. She was the daughter of Captain William Lytle, one of the early settlers of Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wi ...

, and by this marriage Rowan became the uncle of Ohio congressman Robert Todd Lytle

Robert Todd Lytle (May 19, 1804 – December 22, 1839) was a politician who represented Ohio in the United States House of Representatives from 1833 to 1835.

Early life and career

Lytle was born in Williamsburg, Ohio, a nephew of John Rowan. ...

."Rowan, John". The Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans Rowan and his wife – who he affectionately nicknamed "Nancy" – had nine children: Eliza Cooper (Rowan) Harney, Mary Jane (Rowan) Steele, William Lytle Rowan, Atkinson Hill Rowan, John Rowan, Jr., Josephine Daviess (Rowan) Clark, Ann (Rowan) Buchanan, Alice Douglass (Rowan) Shaw Wakefield, and Elizabeth (Rowan) Hughes. Atkinson Hill Rowan served as an emissary to Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

for President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

.Capps, p. 18 John Rowan, Jr. was appointed U.S. Chargé d'Affaires to Naples by President James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

, serving from 1848 to 1849. Ann Rowan married Joseph Rodes Buchanan

Joseph Rodes Buchanan (December 11, 1814 – December 26, 1899) was an American physician and professor of physiology at the Eclectic Medical Institute in Cincinnati, Ohio. Buchanan proposed the terms Psychometry (soul measurement) and Sarcogno ...

, a noted physician of Covington, Kentucky

Covington is a home rule-class city in Kenton County, Kentucky, United States, located at the confluence of the Ohio and Licking Rivers. Cincinnati, Ohio, lies to its immediate north across the Ohio and Newport, to its east across the Licking ...

.

In 1795, Rowan began construction of Federal Hill, his family estate, on land that his father-in-law gave him as a wedding present. Due to limited financial resources, the time required to import building materials from the east, and the craftsmanship required to construct the large home, the mansion was not completed until 1818.Capps, p. 5 After a fire destroyed the log cabin in which the Rowans lived in 1812, they moved into the part of the mansion that was completed, and continued to live there while construction on the rest of the house was finished. Federal Hill was once believed to be the first brick house constructed in the state of Kentucky, but more modern sources give the designation to the William Whitley House, also known as Sportsman's Hill, which was completed in 1794 near Crab Orchard, Kentucky.

Rowan owned slaves. He identified with the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the earl ...

and espoused the Jeffersonian principles of limited government and individual liberty. He was chosen to represent Nelson County at the constitutional convention held at Frankfort, Kentucky in 1799 to draft the second Kentucky Constitution The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the document that governs the Kentucky, Commonwealth of Kentucky. It was first adopted in 1792 and has since been rewritten three times and amended many more. The later versions were adopted in 179 ...

. As a delegate, he advocated the supremacy of the legislative branch over the executive and judicial branches, which he believed provided ordinary citizens a greater role in state government. The constitution adopted by the convention abolished the use of electors to choose the governor and state senators, providing for the direct election of these officers instead.

Duel with Dr. James Chambers

Rowan was known throughout his life as an avid gamester.Little, p. 33 On January 29, 1801, Rowan joined Dr. James Chambers and three other men for a game of cards at Duncan McLean's Tavern in Bardstown.Hibbs, p. 26 After several beers and games ofwhist

Whist is a classic English trick-taking card game which was widely played in the 18th and 19th centuries. Although the rules are simple, there is scope for strategic play.

History

Whist is a descendant of the 16th-century game of ''trump'' ...

, Chambers suggested playing Vingt-et-un

Twenty-one, formerly known as vingt-un in Britain, France and America, is the name given to a family of popular card games of the gambling family, the progenitor of which is recorded in Spain in the early 17th century. The family includes the cas ...

for money instead. Rowan had determined not to gamble during this session of gaming, but impaired by the alcohol, he agreed. After a few hands, an argument broke out between Chambers and Rowan. The exact nature of the argument is not known. Some accounts claim it was over who was better able to speak Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

; others suggest that general insults were exchanged between the two men. A brief scuffle followed the disagreement.

How the matter escalated to a duel is also the subject of some uncertainty. In his biography of Benjamin Hardin, Lucious P. Little recounts that Chambers immediately challenged Rowan to a duel.Little, p. 178 According to Little, Rowan, embarrassed at his behavior, refused the challenge and repeatedly apologized for his actions, but Chambers was insistent on the duel and continued hurling insults of growing severity at Rowan until Rowan accepted the challenge. A letter from George M. Bibb, published a year after the event and reprinted in 1912 in the ''Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society'', claims that Chambers' challenge was issued through a letter delivered to Rowan by Chambers' friend, Major John Bullock, on January 31, 1801.Johnston, p. 28 Bibb claims that he and Rowan had, after the night of the incident, gone to nearby Bullitt County on business, that Rowan had returned first, and that Rowan showed Bibb the letter upon his return on February 1.

Bullock served as Chambers' second for the duel; Bibb acted as second for Rowan. According to Bibb, he and Bullock met on February 1 to discuss the parameters for the duel. Bullock proposed that the matter be dropped, but Bibb insisted that Chambers would have to retract his challenge, to which Bullock would not consent. The duel was held February 3, 1801, near Bardstown. Both combatants missed with their first shots. Both men fired again, and Rowan's second shot struck Chambers, wounding him severely. (Bibb's account says that Chambers was struck in the left side; other accounts state that the shot hit Chambers in the chest.) Rowan then offered his carriage to take Chambers to town for medical attention, and Chambers asked that Rowan not be prosecuted.Hibbs, p. 27 Despite medical aid, Chambers died the following day.

Public sentiment was against Rowan in the matter of his duel with Chambers. Soon after the duel, friends of Chambers formed a

How the matter escalated to a duel is also the subject of some uncertainty. In his biography of Benjamin Hardin, Lucious P. Little recounts that Chambers immediately challenged Rowan to a duel.Little, p. 178 According to Little, Rowan, embarrassed at his behavior, refused the challenge and repeatedly apologized for his actions, but Chambers was insistent on the duel and continued hurling insults of growing severity at Rowan until Rowan accepted the challenge. A letter from George M. Bibb, published a year after the event and reprinted in 1912 in the ''Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society'', claims that Chambers' challenge was issued through a letter delivered to Rowan by Chambers' friend, Major John Bullock, on January 31, 1801.Johnston, p. 28 Bibb claims that he and Rowan had, after the night of the incident, gone to nearby Bullitt County on business, that Rowan had returned first, and that Rowan showed Bibb the letter upon his return on February 1.

Bullock served as Chambers' second for the duel; Bibb acted as second for Rowan. According to Bibb, he and Bullock met on February 1 to discuss the parameters for the duel. Bullock proposed that the matter be dropped, but Bibb insisted that Chambers would have to retract his challenge, to which Bullock would not consent. The duel was held February 3, 1801, near Bardstown. Both combatants missed with their first shots. Both men fired again, and Rowan's second shot struck Chambers, wounding him severely. (Bibb's account says that Chambers was struck in the left side; other accounts state that the shot hit Chambers in the chest.) Rowan then offered his carriage to take Chambers to town for medical attention, and Chambers asked that Rowan not be prosecuted.Hibbs, p. 27 Despite medical aid, Chambers died the following day.

Public sentiment was against Rowan in the matter of his duel with Chambers. Soon after the duel, friends of Chambers formed a posse

Posse is a shortened form of posse comitatus, a group of people summoned to assist law enforcement. The term is also used colloquially to mean a group of friends or associates.

Posse may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Posse'' (1975 ...

and rode toward Rowan's house. Rowan concocted a ruse whereby he dressed a family slave in his coat and hat and sent him riding from the house on horseback.Little, p. 179 The posse was fooled into thinking the slave was Rowan and gave chase, but the slave escaped and Rowan's life was spared as well. Days later, the owner of the land where the duel had taken place swore out a warrant for Rowan's arrest for murder. Some accounts hold that, as Commonwealth's Attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or state attorney is the chief prosecutor and/or chief law enforcement officer representing a U.S. state in a lo ...

, Rowan's friend Felix Grundy would have been responsible for prosecuting the case against Rowan and that Grundy resigned the position to avoid prosecuting his friend. Grundy's biographer, John Roderick Heller, admits that this was possible, although no evidence exists to confirm it.Heller, p. 38 Heller also points out that Grundy was Commonwealth's Attorney not in Nelson County (the location of Bardstown), but in neighboring Washington County at the time. Joseph Hamilton Daveiss and Colonel William Allen served as counsel for Rowan. The judge opined that there was insufficient evidence to send the case to a grand jury, and Rowan was released.

Secretary of State and early legislative career

Shortly after his duel with Chambers, Rowan moved to Frankfort, Kentucky, the state capital.Capps, p. 6 In 1802, he was one of 32 men who signed a pledge to bringJames Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

to Transylvania University

Transylvania University is a private university in Lexington, Kentucky. It was founded in 1780 and was the first university in Kentucky. It offers 46 major programs, as well as dual-degree engineering programs, and is accredited by the Southern ...

as superintendent.Capps, p. 9 This action began a long relationship between Rowan and Transylvania, and the university presented him with an honorary Doctor of Laws

A Doctor of Law is a degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country and includes degrees such as the Doctor of Juridical Science (J.S.D. or S.J.D), Juris Doctor (J.D.), Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), and Legum Doctor ...

degree in 1823. Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Christopher Greenup

Christopher Greenup (c. 1750 – April 27, 1818) was an American politician who served as a U.S. Representative and the third Governor of Kentucky. Little is known about his early life; the first reliable records about him are documents recordi ...

appointed Rowan Secretary of State in 1804. He served until 1806, when he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

. He represented Kentucky's Third District (which included Bardstown) during the Tenth Congress from March 4, 1807 to March 3, 1809, even though he did not reside in that district at the time.

The first major congressional debate in which Rowan participated was over the election of William McCreery as representative from Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

.Capps, p. 40 Joshua Barney

Joshua Barney (6 July 1759 – 1 December 1818) was an American Navy officer who served in the Continental Navy during the Revolutionary War and as a captain in the French Navy during the French Revolutionary Wars. He later achieved the rank o ...

, McCreery's opponent in the election, claimed that McCreery did not meet a requirement in the Maryland Constitution

The current Constitution of the State of Maryland, which was ratified by the people of the state on September 18, 1867, forms the basic law for the U.S. state of Maryland. It replaced the short-lived Maryland Constitution of 1864 and is the fourt ...

that a representative live in the district from which he was elected for twelve months prior to the election. McCreery admitted that he had moved from Baltimore to the country prior to the election but claimed that he still owned his home in Baltimore and lived there during the winter months. A resolution was introduced to declare McCreery the duly elected representative from Baltimore, and an amendment was added to clarify that the grounds upon which the resolution was based were that McCreery had not abandoned his Baltimore home. Despite his support for states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

, Rowan opposed the amendment because he felt that state sovereignty was only made possible by national sovereignty and that the national legislature had the right to declare a state law unconstitutional. By giving another reason for declaring McCreery duly elected, Rowan felt this issue would be obscured. The amendment was defeated by a vote of 92–8, and the resolution to declare McCreery duly elected passed 89–18.

Also during the first session of the Tenth Congress, Rowan proposed that a congressional committee be formed to investigate accusations against General James Wilkinson that, in 1788, he took money from the government of Spain in exchange for efforts to separate Kentucky from Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

and unite it with Spain rather than the United States. Aaron Burr had been accused of working with Wilkinson in the so-called Spanish Conspiracy, and when Burr had approached Rowan in 1806 to solicit his services in defending Burr against the charges, Rowan had declined because he believed Burr to be guilty. Rowan's proposal to form an investigative committee against Wilkinson failed, but he succeeded in gaining approval for a committee to investigate federal judge Harry Innes' purported role in the Conspiracy. Rowan was appointed to the committee and delivered its report April 19, 1808; the report stated that the committee could find no evidence of wrongdoing by Innes.

Rowan was not as active during the second session of the Tenth Congress, introducing no legislation and making no major speeches. Newly elected Kentucky Senator John Pope observed in a letter to a friend that the Democratic-Republicans in Congress disliked Rowan and were disappointed in his speaking and debating ability.Capps, p. 41 He opined that Rowan's attempt to investigate Wilkinson had been a slap at party founder Thomas Jefferson (then in his second term as President), under whom Wilkinson was serving as Commanding General of the United States Army

The Commanding General of the United States Army was the title given to the service chief and highest-ranking officer of the United States Army (and its predecessor the Continental Army), prior to the establishment of the Chief of Staff of the ...

. Pope went on to write that, although Rowan personally cited no party affiliation, he was claimed by the Federalist caucus in the House. In studying Rowan's short tenure in the House, historian Stephen Fackler observed that "Rowan adhered more rigidly to the precepts of Jeffersonian republicanism than Jefferson himself, for the president compromised his principles in the national interest."Fackler, p. 8 Fackler observed that Rowan often disagreed with Jefferson as president, and that as a result, some historians labeled him a Federalist, a designation Fackler felt was in error.

After his tenure in Congress, Rowan was elected to represent Nelson County in the Kentucky House of Representatives from 1813 to 1817. In 1817, the House debated a resolution instructing Governor Gabriel Slaughter

Gabriel Slaughter (December 12, 1767September 19, 1830) was the seventh Governor of Kentucky and was the first person to ascend to that office upon the death of the sitting governor. His family moved to Kentucky from Virginia when he was very y ...

to negotiate with the governors of Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

and Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

to secure passage of legislation requiring citizens of those states to return fugitive slaves.Birney, p. 34 Representative James G. Birney vigorously opposed the resolution, and it was defeated. The pro-slavery members of the House then rallied behind Rowan's leadership to pass a substitute resolution which softened the most objectionable language but retained the call for fugitive slave legislation in Indiana and Ohio.

Legislative interim and service on the Court of Appeals

Rowan often found himself in demand as an orator and host. In February 1818, he was chosen to eulogize his close friend, George Rogers Clark. In June 1819, the citizens of Louisville chose him as their official host for a visiting party that included

Rowan often found himself in demand as an orator and host. In February 1818, he was chosen to eulogize his close friend, George Rogers Clark. In June 1819, the citizens of Louisville chose him as their official host for a visiting party that included James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

and Andrew Jackson. In May 1825, he was one of thirteen men chosen by the citizens of Louisville to organize a reception for a visit by the Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

.

Rowan was appointed as a judge of the Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky.

Th ...

in 1819. During his time as a justice, he delivered a notable opinion opposing the constitutionality of chartering of the Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ...

. He also opined that the General Assembly was within its rightful powers to enact a tax on the Bank.Fackler, p. 16 In the case of '' McCulloch v. Maryland'', the U.S. Supreme Court delivered a contradictory opinion. Dissatisfied with the confinement of service on the bench, Rowan resigned from the court in 1821. Though his service was brief, he was referred to as "Judge Rowan" for the rest of his life.Capps, p. 36

While Rowan was still a justice of the Court of Appeals, the General Assembly chose him and John J. Crittenden

John Jordan Crittenden (September 10, 1787 July 26, 1863) was an American statesman and politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He represented the state in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate and twice served as Unite ...

as commissioners to resolve a border dispute with Tennessee.Heller, pp. 137–138 The dispute had arisen from an erroneous survey of the border line conducted by Dr. Thomas Walker years earlier. Walker's line deviated northward from the intended line (36 degrees, 30 minutes north latitude) by some twelve miles by the time it reached the Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. It is approximately long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other name ...

.Heller, p. 137 The Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

commissioners, Felix Grundy and William L. Brown, proposed that, because it had been accepted for so long, the Walker line be observed as far west as the Tennessee River, with Kentucky being compensated with a more southerly line between the Tennessee and Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

Rivers.Heller, p. 138 Crittenden was inclined to accept this proposal with some minor adjustments, but Rowan insisted that Tennessee honor the statutory border of 36 degrees, 30 minutes north. The Tennessee commissioners refused to submit to arbitration in the matter, and Rowan and Crittenden delivered separate reports to the Kentucky legislature. The legislature adopted Crittenden's report; Rowan then resigned as commissioner and was replaced by Robert Trimble. Thereafter, the commissioners quickly agreed to a slightly modified version of the Tennessee proposal.

In 1823, the state legislature chose Rowan and Henry Clay to represent the defendant in a second rehearing of ''Green v. Biddle

''Green v. Biddle'', 1 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 1 (1823), is a 6-to-1 ruling by the Supreme Court of the United States that held that the U.S. state, state of Virginia had properly entered into a compact with the United States federal government under Artic ...

'' before the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

.Little, p. 326 The case, which involved the constitutionality of laws passed by the General Assembly relating to land titles granted in Kentucky when the state was still a part of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, was of interest to the legislature.Little, p. 325 The Supreme Court, however, refused the second rehearing, letting stand their previous opinion that Kentucky's laws were in violation of the compact of separation from Virginia.

Old Court – New Court controversy

Due to thePanic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic ...

, many citizens in Kentucky fell deep into debt and began petitioning the legislature for help.Harrison and Klotter, p. 109 The state's politicians split into two factions. Those who advocated for measures that were more favorable to debtors were dubbed the Relief faction while those who insisted on sound money

In macroeconomics, hard currency, safe-haven currency, or strong currency is any globally traded currency that serves as a reliable and stable store of value. Factors contributing to a currency's ''hard'' status might include the stability and ...

principles and the strict adherence to the obligation of contracts were called the Anti-Relief faction. In 1820, a pro-relief measure passed the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presb ...

providing debtors a one-year stay on the collection of their debts if the creditor would accept payment in devalued notes issued by the Bank of the Commonwealth or a two-year stay if the creditor demanded payment in sound money. Two separate circuit courts found the law unconstitutional in the cases of ''Williams v. Blair'' and ''Lapsley v. Brashear''.Harrison and Klotter, p. 110

Meanwhile, Rowan, who espoused the Relief position, was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1822 representing

Meanwhile, Rowan, who espoused the Relief position, was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1822 representing Jefferson Jefferson may refer to:

Names

* Jefferson (surname)

* Jefferson (given name)

People

* Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), third president of the United States

* Jefferson (footballer, born 1970), full name Jefferson Tomaz de Souza, Brazilian foo ...

and Oldham

Oldham is a large town in Greater Manchester, England, amid the Pennines and between the rivers Irk and Medlock, southeast of Rochdale and northeast of Manchester. It is the administrative centre of the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham ...

counties.Capps, p. 38 He immediately became the leader of the Relief faction in the House.Little, p. 106 When Relief partisans decided to appeal ''Williams'' and ''Lapsley'' to the Kentucky Court of Appeals, which was at the time the court of last resort

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

in the state, Rowan was chosen to argue the appeal before the court alongside George M. Bibb and Lieutenant Governor William T. Barry

William Taylor Barry (February 5, 1784 – August 30, 1835) was an American slave owner, statesman and jurist. He served as Postmaster General for most of the administration of President Andrew Jackson and was the only Cabinet member not to resi ...

.Little, p. 102 Their efforts failed, however, as the Court found the measure unconstitutional, upholding the decisions of the lower courts.Fackler, p. 17

On December 10, 1823, Rowan presented resolutions condemning the Court's decision to the legislature.Little, p. 108 The twenty-six page preamble to the resolutions laid out the Relief faction's reasoning upon the subject of debt relief and legislative supremacy. The preamble and resolutions were adopted in the House by a vote of 56–40.Schoenbachler, p. 105 The offending judges – two of whom had been Rowan's colleagues during his service on the Court – were summoned before the legislature to defend their decisions later in December.Allen, p. 87Capps, p. 39 Following their appearance, Rowan introduced a measure to remove them from office; the vote in the House was 56–40 in favor of the measure, but this fell short of the two-thirds majority 2/3 may refer to:

* A fraction with decimal value 0.6666...

* A way to write the expression "2 ÷ 3" ("two divided by three")

* 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marines of the United States Marine Corps

* February 3

* March 2

Events Pre-1600

* 537 – ...

needed to remove the judges.Fackler, p. 19 The Relief faction then introduced legislation to repeal the law that originally created the Court of Appeals, then replace the abolished court with a new court. Anti-Relief partisans decried the measure as blatantly unconstitutional. Rowan was the chief defender of the measure, and after his impassioned speech on the night of December 24, 1824, it passed by simple majority.Fackler, p. 20 In November 1824, Rowan heavily revised the preamble and resolutions he presented in the previous legislative session. These revised documents effectively formed the faction's platform for the upcoming elections.

Rowan's role in the Old Court – New Court controversy

The Old Court – New Court controversy was a 19th-century political controversy in the U.S. state of Kentucky in which the Kentucky General Assembly abolished the Kentucky Court of Appeals and replaced it with a new court. The justices of the o ...

strained his relationship with his former friend, Benjamin Hardin.Capps, p. 12 Hardin and Rowan had once been so close that Hardin named one of his sons "Rowan" in his colleague's honor. After the controversy, Hardin insisted that friends and family refer to Rowan Hardin as "Ben", but few people other than Hardin himself adopted the new name.

Service in the U.S. Senate

As a result of the 1824 elections, the Relief faction gained a 22–16 majority in thestate Senate

A state legislature in the United States is the legislative body of any of the 50 U.S. states. The formal name varies from state to state. In 27 states, the legislature is simply called the ''Legislature'' or the ''State Legislature'', whil ...

and a 61–39 majority in the House.Little, p. 109 The pro-Relief majority in the state Senate subsequently elected Rowan to the U.S. Senate, which had the inadvertent effect of weakening the faction's cause in the House by removing its leader there.Little, p. 138 Rowan served in the Senate from March 4, 1825 to March 3, 1831. During the Twenty-first Congress, he was chairman of the Judiciary Committee.

On April 10, 1826, Rowan sponsored an amendment to legislation to reorganize the federal judiciary that would have required seven justices to concur with a decision in order to strike down a law as unconstitutional. The amendment, which ultimately failed, was offered in the aftermath of a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States declaring an occupying claimant law to be unconstitutional; Rowan personally disagreed with the Court's decision. Rowan offered another amendment providing that ministers of the federal courts would be subject to state laws when carrying out the decisions of the federal courts. After a month of debate, the entire bill was tabled.Capps, p. 42

An ally of Senator Richard Mentor Johnson

Richard Mentor Johnson (October 17, 1780 – November 19, 1850) was an American lawyer, military officer and politician who served as the ninth vice president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841 under President Martin Van Buren ...

, who was a primary voice against the practice of debt imprisonment, Rowan made a notable speech denouncing the practice on the Senate floor in 1828.''Biographical Cyclopedia'', p. 273 A consistent opponent of internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

and tariffs, even those that would benefit his own constituents, he voted against a measure allocating federal funds for the construction of a road connecting the cities of Lexington and Maysville.Fackler, p. 24 The vote was ill-received by the people of the state, and Rowan's popularity took a significant hit. When the bill was re-introduced in the next congressional session, Rowan voted for it only after receiving significant pressure from the state legislature to do so. The bill passed in this session, but newly elected president Andrew Jackson veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

ed it.

In the state legislative elections of 1830, the ascendent Whig Party gained control of both houses of the General Assembly.Little, p. 156 Rowan's strict adherence to Jeffersonian democracy and leadership of the New Court faction during the court controversy of the 1820s had put him at odds with Whig founder Henry Clay. By this time, however, not even Rowan's fellow Democrats endorsed his re-election.Fackler, p. 25 Henry Clay was elected instead.

Later life and legacy

After his service in the Senate, Rowan returned to Kentucky, dividing his time between Louisville and Bardstown. During an epidemic of cholera that spread through Bardstown in 1833, three of Rowan's children (William, Atkinson, and Mary Jane) died. The spouses of William and Mary Jane also died of cholera, as did Mary Jane's daughter, and Rowan's sister Elizabeth and her husband.Capps, p. 21 Aid from Bishop Joseph Flaget and a group of nuns who traveled to Federal Hill during the epidemic probably spared the life of Rowan's orphaned granddaughter, Eliza Rowan Harney.

In 1836, Rowan and two other men founded the Louisville Medical Institute, the forerunner of the

After his service in the Senate, Rowan returned to Kentucky, dividing his time between Louisville and Bardstown. During an epidemic of cholera that spread through Bardstown in 1833, three of Rowan's children (William, Atkinson, and Mary Jane) died. The spouses of William and Mary Jane also died of cholera, as did Mary Jane's daughter, and Rowan's sister Elizabeth and her husband.Capps, p. 21 Aid from Bishop Joseph Flaget and a group of nuns who traveled to Federal Hill during the epidemic probably spared the life of Rowan's orphaned granddaughter, Eliza Rowan Harney.

In 1836, Rowan and two other men founded the Louisville Medical Institute, the forerunner of the University of Louisville

The University of Louisville (UofL) is a public research university in Louisville, Kentucky. It is part of the Kentucky state university system. When founded in 1798, it was the first city-owned public university in the United States and one o ...

medical school. The next year, Rowan was chosen as the school's first president, serving in that capacity until 1842.Cox and Morison, pp. 12–13 He also served as the first president of the Kentucky Historical Society

The Kentucky Historical Society (KHS) was originally established in 1836 as a private organization. It is an agency of the Kentucky state government that records and preserves important historical documents, buildings, and artifacts of Kentucky's ...

from 1838 until his death.

In his last act of public service, in 1839 Rowan was appointed as a commissioner to adjust land claims of U.S. citizens against the Republic of Mexico

Mexico ( Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guate ...

. During an adjournment of the commission in 1842, Rowan returned to Kentucky to visit relatives.Little, p. 180 While there, he fell ill and was unable to return to Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

; consequently, he resigned his commission.Capps, p. 46 Rowan died July 13, 1843. He was interred in the family burial ground at Federal Hill. In his will, Rowan specified that no marker should be placed over his grave, noting that his parents' graves had no markers, and he did not want to be honored above his parents.Capps, p. 25 Several years later, members of his family placed a marker over his grave, despite his wishes. According to legend, the marker frequently tumbles from its base, purportedly a manifestation of Rowan haunting his grave.Hauck, "Bardstown Cemetery"

Cousin of the Rowan family, Stephen Collins Foster, was inspired by Harriet Beecher Stowe's anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U ...

to write his ballad ''My Old Kentucky Home

"My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!" is a sentimental ballad written by Stephen Foster, probably composed in 1852. It was published in January 1853 by Firth, Pond, & Co. of New York. Foster was likely inspired by Harriet Beecher Stowe's anti-sla ...

''. The song was not associated with Federal Hill until after the Civil War, and Stephen likely never visited the site, as attested by his biographers such as John Tasker Howard, William Austin, Ken Emerson, and JoAnne O’Connell. The mansion remained in the possession of Judge Rowan's family until 1922, when his granddaughter, Madge (Rowan) Frost, sold it to the state of Kentucky to be preserved as a state shrine.Kleber, "Federal Hill", p. 312 Today, it is a part of My Old Kentucky Home State Park

My Old Kentucky Home State Park is a state park located in Bardstown, Kentucky, United States. The park's centerpiece is Federal Hill, a former plantation home owned by United States Senator John Rowan in 1795. During the Rowan family's occupat ...

in Bardstown.Jester, "Myth About "My Old Kentucky Home" in Dispute" In 1856, the Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It comprises the Kentucky Senate and the Kentucky House of Representatives.

The General Assembly meets annually in ...

created a new county from parts of Fleming and Morgan counties and named it Rowan County in Rowan's honor.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Rowan, John 1773 births 1843 deaths Politicians from York, Pennsylvania People of colonial Pennsylvania American people of Scotch-Irish descent Democratic-Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Kentucky Jacksonian United States senators from Kentucky Secretaries of State of Kentucky Members of the Kentucky House of Representatives Judges of the Kentucky Court of Appeals Kentucky lawyers American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law American slave owners American duellists People from Bardstown, Kentucky Politicians from Louisville, Kentucky Rowan County, Kentucky Presidents of the University of Louisville United States senators who owned slaves