John Paul Stevens on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

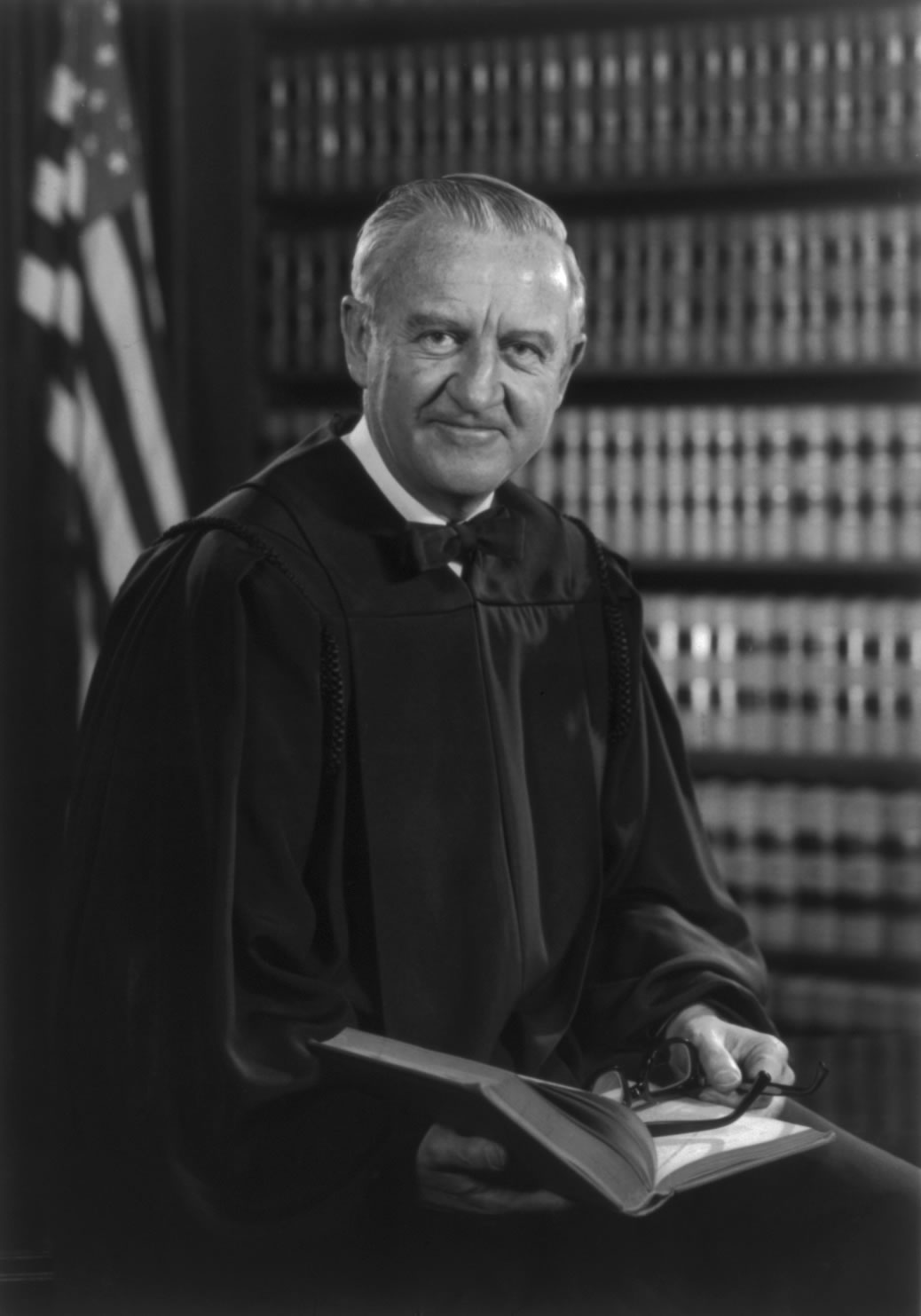

John Paul Stevens (April 20, 1920 – July 16, 2019) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an

"Justice John Paul Stevens has strong Chicago ties"

, WGN, (April 9, 2010). Chicago, Illinois, to a wealthy family. His paternal grandfather had formed an insurance company and held real estate in Chicago, while his granduncle owned the Chas A. Stevens department store. His father, Ernest James Stevens (1884–1972), was a lawyer who later became an hotelier, owning two hotels, the La Salle and the Stevens Hotel. The family lost ownership of the hotels during the

Stevens's role in the Greenberg Commission catapulted him to prominence and was largely responsible for President

Stevens's role in the Greenberg Commission catapulted him to prominence and was largely responsible for President

"With Longevity on Court, Stevens' Center-Left Influence Has Grown"

, '' On January 20, 2009, Stevens administered the

On January 20, 2009, Stevens administered the

Stevens retired on June 29, 2010 as the third-longest-serving justice in the history of the Supreme Court with 34 years and six months of service and just three days short of tying the tenure of the second-longest serving justice in history, Stephen Johnson Field, who had retired on December 1, 1897. The longest-serving justice is Stevens's immediate predecessor, Justice William O. Douglas, who served 36 years and retired on November 12, 1975. He was the last veteran of the Burger Court to remain on the bench.

Stevens was also the second-oldest justice, at age 90 years and two months at retirement, behind Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. who retired at the age of 90 years and 10 months on January 12, 1932. On July 23, 2015, Stevens became the longest-lived retired justice, surpassing

Stevens retired on June 29, 2010 as the third-longest-serving justice in the history of the Supreme Court with 34 years and six months of service and just three days short of tying the tenure of the second-longest serving justice in history, Stephen Johnson Field, who had retired on December 1, 1897. The longest-serving justice is Stevens's immediate predecessor, Justice William O. Douglas, who served 36 years and retired on November 12, 1975. He was the last veteran of the Burger Court to remain on the bench.

Stevens was also the second-oldest justice, at age 90 years and two months at retirement, behind Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. who retired at the age of 90 years and 10 months on January 12, 1932. On July 23, 2015, Stevens became the longest-lived retired justice, surpassing

NPR website

and transcript found a

NPR website

. Cited by Sarah Pulliam Bailey, "The Post-Protestant Supreme Court: Christians weigh in on whether it matters that the high court will likely lack Protestant representation," ''

Christianity Today website

. Also cited by "Does the U.S. Supreme Court need another Protestant?" ''

USA Today website

. All accessed April 10, 2010.

online

* * * *

at OnTheIssues

John Paul Stevens

encyclopedia article by Prof. Joseph Thai

John Paul Stevens, Human Rights Judge

by Prof. Diane Marie Amann

, by Linda Greenhouse, ''

After Stevens

Jeffrey Toobin, ''

The Pessimistic Legacy of John Paul Stevens

', Jeff Greenfield,

Stevens High School

named after Stevens

– slideshow by '' Salon magazine''

John Paul Stevens's Legacy in Five Cases

by '' Newsweek magazine''

Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens to Retire, PBS NewsHour

Justice Stevens a "Champion of the Constitution"

– video report by '' Democracy Now!''

Justice Stevens: An Open Mind On A Changed Court

– audio report by '' NPR'' *

Supreme Court Associate Justice Nomination Hearings on John Paul Stevens in December 1975

United States Government Publishing Office *

Arlington National Cemetery

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Stevens, John Paul 1920 births 2019 deaths 20th-century American judges 20th-century Protestants 21st-century American judges 21st-century Protestants American Protestants Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Illinois Republicans Judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States Law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States Lawyers from Chicago Military personnel from Illinois Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law alumni People associated with Jenner & Block Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients United States court of appeals judges appointed by Richard Nixon United States federal judges appointed by Gerald Ford United States Navy officers United States Navy personnel of World War II University of Chicago alumni University of Chicago Laboratory Schools alumni Writers from Chicago Psi Upsilon

associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

An associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is any member of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the chief justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the Judiciary Act of ...

from 1975 to 2010. At the time of his retirement, he was the second-oldest justice in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court and the third- longest-serving justice. At the time of his death in 2019 at age 99, he was the longest-lived Supreme Court justice ever. His long tenure saw him write for the Court on most issues of American law, including civil liberties, the death penalty, government action, and intellectual property. In cases involving presidents of the United States, he wrote for the court that they were to be held accountable under American law. Despite being a registered Republican who throughout his life identified as a conservative, Stevens was considered to have been on the liberal side of the Court at the time of his retirement.

Born in Chicago, Stevens served in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and graduated from Northwestern University School of Law

Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law is the law school of Northwestern University, a private research university. It is located on the university's Chicago campus. Northwestern Law has been ranked among the top 14, or "T14" law scho ...

. After clerking for Justice Wiley Blount Rutledge, he co-founded a law firm in Chicago, focusing on antitrust law. In 1970, President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

appointed Stevens to the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. Five years later, President Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

successfully nominated Stevens to the Supreme Court to fill the vacancy caused by the retirement of Justice William O. Douglas. He became the senior associate justice after the retirement of Harry Blackmun in 1994. After the death of Chief Justice William Rehnquist, Stevens briefly acted in the capacity of chief justice before the appointment of John Roberts. Stevens retired in 2010 during the administration of President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

and was succeeded by Elena Kagan.

Stevens's majority opinions in landmark cases include '' Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc.'', ''Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council

''Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.'', 467 U.S. 837 (1984), was a landmark case in which the United States Supreme Court set forth the legal test for determining whether to grant deference to a government agency's inte ...

'', ''Apprendi v. New Jersey

''Apprendi v. New Jersey'', 530 U.S. 466 (2000), is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision with regard to aggravating factors in crimes. The Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial, incorporated against the states th ...

'', '' Hamdan v. Rumsfeld'', ''NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware Co.

''National Association for the Advancement of Colored People v. Claiborne Hardware Co.'', 458 U.S. 886 (1982),. was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court ruling 8–0 (Marshall did not participate in the decision) that although ...

'', ''Kelo v. City of New London

''Kelo v. City of New London'', 545 U.S. 469 (2005), was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States in which the Court held, 5–4, that the use of eminent domain to transfer land from one private owner to another private owner ...

'', ''Gonzales v. Raich

''Gonzales v. Raich'' (previously ''Ashcroft v. Raich''), 545 U.S. 1 (2005), was a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that under the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution, Congress may criminalize the production and use of homegrown ca ...

'', ''U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton

''U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton'', 514 U.S. 779 (1995), is a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that states cannot impose qualifications for prospective members of the U.S. Congress stricter than those the Constituti ...

'', and ''Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency

''Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency'', 549 U.S. 497 (2007), is a 5–4 U.S. Supreme Court case in which twelve states and several cities of the United States, represented by James Milkey, brought suit against the Environmental Pr ...

''. Stevens is also known for his dissents in '' Texas v. Johnson'', '' Bush v. Gore'', '' Bethel v. Fraser'', '' District of Columbia v. Heller'', '' Printz v. United States'', and '' Citizens United v. FEC''.

Life and career

Early life and education (1920–1947)

Stevens was born on April 20, 1920, in Hyde Park,William Mullen"Justice John Paul Stevens has strong Chicago ties"

, WGN, (April 9, 2010). Chicago, Illinois, to a wealthy family. His paternal grandfather had formed an insurance company and held real estate in Chicago, while his granduncle owned the Chas A. Stevens department store. His father, Ernest James Stevens (1884–1972), was a lawyer who later became an hotelier, owning two hotels, the La Salle and the Stevens Hotel. The family lost ownership of the hotels during the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, and Stevens's father, grandfather, and an uncle were charged with embezzlement; the Illinois Supreme Court later overturned the conviction, criticizing the prosecution. His mother, Elizabeth Street Stevens (1881–1979), was a high school English teacher. Two of his three older brothers also became lawyers.

A lifelong Chicago Cubs

The Chicago Cubs are an American professional baseball team based in Chicago. The Cubs compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as part of the National League (NL) Central division. The club plays its home games at Wrigley Field, which is locate ...

fan, Stevens was 12 when he attended the 1932 World Series between the Yankees and the Cubs in Chicago's Wrigley Field

Wrigley Field is a Major League Baseball (MLB) stadium on the North Side of Chicago, Illinois. It is the home of the Chicago Cubs, one of the city's two MLB franchises. It first opened in 1914 as Weeghman Park for Charles Weeghman's Chicago ...

, in which Babe Ruth

George Herman "Babe" Ruth Jr. (February 6, 1895 – August 16, 1948) was an American professional baseball player whose career in Major League Baseball (MLB) spanned 22 seasons, from 1914 through 1935. Nicknamed "the Bambino" and "the Su ...

allegedly called his shot. Stevens later recalled: "Ruth did point to the center-field scoreboard. And he did hit the ball out of the park after he pointed with his bat, so it really happened." He also had the opportunity to meet several notable people of the era, including the famed aviators Amelia Earhart and Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

, the latter of whom gave him a caged dove as a gift.

The family lived in Hyde Park, and Stevens attended the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools

The University of Chicago Laboratory Schools (also known as Lab or Lab Schools and abbreviated as UCLS though the high school is nicknamed U-High) is a private, co-educational day Pre-K and K-12 school in Chicago, Illinois. It is affiliated w ...

where he graduated in 1937. He later attended the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

, where he majored in English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

, was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

, and graduated with highest honors in 1941. While in college, Stevens also became a member of the Psi Upsilon fraternity.

He began work on his master's degree in English at the university in 1941 but soon decided to join the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. He enlisted on December 6, 1941, one day before the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

, and served as an intelligence officer in the Pacific Theater from 1942 to 1945. Stevens was awarded a Bronze Star

The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is a United States Armed Forces decoration awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces for either heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious achievement, or meritorious service in a combat zone.

W ...

for his service in the codebreaking team whose work led to the downing of Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto's plane in 1943 ( Operation Vengeance).

Stevens married Elizabeth Jane Shereen in June 1942. Divorcing her in 1979, he married Maryan Mulholland Simon that December; that marriage lasted until Simon's death in 2015 following complications from hip surgery. He had four children: John Joseph (who died of cancer in 1996), Kathryn (who died in 2018), Elizabeth, and Susan.

With the end of World War II, Stevens returned to Illinois, intending to return to his studies in English, but was persuaded by his brother Richard, who was a lawyer, to attend law school. Stevens enrolled in the Northwestern University School of Law

Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law is the law school of Northwestern University, a private research university. It is located on the university's Chicago campus. Northwestern Law has been ranked among the top 14, or "T14" law scho ...

in 1945, with the G.I. Bill paying most of his tuition. Stevens graduated in 1947 ranked first in his class with a J.D. '' magna cum laude'', having earned the highest GPA in the school's history.

Legal career, 1947–1970

After receiving high recommendations from several Northwestern faculty members, Stevens served as alaw clerk

A law clerk or a judicial clerk is a person, generally someone who provides direct counsel and assistance to a lawyer or judge by researching issues and drafting legal opinions for cases before the court. Judicial clerks often play significant ...

to Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

justice Wiley Rutledge during the 1947–48 term.

Following his clerkship, Stevens returned to Chicago and joined the law firm of Poppenhusen, Johnston, Thompson & Raymond (now Jenner & Block). Stevens was admitted to the bar in 1949. He determined that he would not stay long at the Poppenhusen firm after being docked his pay for the day he took off to travel to Springfield to swear his oath of admission. During his time at the firm, Stevens began his practice in antitrust law.

In 1951, he returned to Washington, DC, to serve as associate counsel to the Subcommittee on the Study of Monopoly Power of the Judiciary Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives. During this time, the subcommittee worked on several highly publicized investigations in many industries, most notably Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball organization and the oldest major professional sports league in the world. MLB is composed of 30 total teams, divided equally between the National League (NL) and the American League (A ...

.

In 1952, Stevens returned to Chicago and, together with two other young lawyers with whom he had worked at Poppenhusen, Johnston, Thompson & Raymond, formed his own law firm: Rothschild, Stevens, Barry & Myers. It soon developed into a successful practice, with Stevens continuing to focus on antitrust cases. His growing expertise in antitrust law led to an invitation to teach the "Competition and Monopoly" course at the University of Chicago Law School, and from 1953 to 1955, he was a member of the Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

's National Committee to Study Antitrust Laws. At the same time, Stevens was making a name for himself as a first-rate antitrust litigator and was involved in a number of trials. He was widely regarded by colleagues as an extraordinarily capable and impressive lawyer with a fantastic memory and analytical ability, and authored a number of influential works on antitrust law.

In 1969, the Greenberg Commission, appointed by the Illinois Supreme Court to investigate Sherman Skolnick's corruption allegations leveled at former chief justice Ray Klingbiel and then-current chief justice Roy Solfisburg, named Stevens as its counsel, meaning that he essentially served as the commission's special prosecutor. The commission was widely thought to be a whitewash, but Stevens proved them wrong by vigorously prosecuting the justices, forcing them from office in the end. As a result of the prominence he gained during the Greenberg Commission, Stevens became the second vice president of the Chicago Bar Association in 1970.

Judicial career, 1970–2010

Stevens's role in the Greenberg Commission catapulted him to prominence and was largely responsible for President

Stevens's role in the Greenberg Commission catapulted him to prominence and was largely responsible for President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

's decision to appoint Stevens as a judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit on November 20, 1970. His nomination was put forth by a former University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

classmate, Illinois Senator Charles H. Percy.

On November 28, 1975, President Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

nominated Stevens as an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, to a seat vacated by William O. Douglas. Again, it was Percy who suggested Stevens; the nomination was also strongly supported by Attorney General Edward Levi

Edward Hirsch Levi (June 26, 1911 – March 7, 2000) was an American law professor, academic leader, and government lawyer. He served as dean of the University of Chicago Law School from 1950 to 1962, president of the University of Chicago from ...

, former president of the University of Chicago. He was sworn into office December 19, 1975, after being confirmed 98–0 by the U.S. Senate two days before.

When Harry Blackmun retired in 1994, Stevens became the senior associate justice and thus assumed the administrative duties of the Court whenever the post of Chief Justice of the United States was vacant or the chief justice was unable to perform his duties. Stevens performed the duties of chief justice in September 2005, between the death of Chief Justice William Rehnquist and the swearing-in of his replacement, Chief Justice John Roberts, and presided over oral arguments on a number of occasions when the chief justice was ill or recused. Also in September 2005, Stevens was honored with a symposium by Fordham Law School

Fordham University School of Law is the law school of Fordham University. The school is located in Manhattan in New York City, and is one of eight ABA-approved law schools in that city. In 2013, 91% of the law school's first-time test taker ...

for his 30 years on the Supreme Court, and President Ford wrote a letter stating his continued pride in appointing him.

In a 2005 speech, Stevens stressed the importance of "learning on the job"; for example, during his tenure on the Court, Stevens changed his views on affirmative action (initially opposed), as well as on other issues. President Ford praised Stevens in 2005: "He is serving his nation well, with dignity, intellect and without partisan political concerns."

Additionally, he participated actively in questioning during oral arguments.Charles Lane"With Longevity on Court, Stevens' Center-Left Influence Has Grown"

, ''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'', February 21, 2006. Stevens was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

in 2008. That same year he was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

.

On January 20, 2009, Stevens administered the

On January 20, 2009, Stevens administered the oath of office

An oath of office is an oath or affirmation a person takes before assuming the duties of an office, usually a position in government or within a religious body, although such oaths are sometimes required of officers of other organizations. Suc ...

to Vice President Joe Biden at Biden's request. It is customary for the vice president to be inaugurated by the person of their choice.

On April 9, 2010, Stevens announced his intention to retire from the Supreme Court; he subsequently retired on June 29 of that year. Stevens said that his decision to retire from the Court was initially triggered when he stumbled on several sentences when delivering his oral dissent in the 2010 landmark case '' Citizens United v. FEC''. Stevens said "I took that as a warning sign that maybe I've been around longer than I should."

Tenure and age

Stevens retired on June 29, 2010 as the third-longest-serving justice in the history of the Supreme Court with 34 years and six months of service and just three days short of tying the tenure of the second-longest serving justice in history, Stephen Johnson Field, who had retired on December 1, 1897. The longest-serving justice is Stevens's immediate predecessor, Justice William O. Douglas, who served 36 years and retired on November 12, 1975. He was the last veteran of the Burger Court to remain on the bench.

Stevens was also the second-oldest justice, at age 90 years and two months at retirement, behind Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. who retired at the age of 90 years and 10 months on January 12, 1932. On July 23, 2015, Stevens became the longest-lived retired justice, surpassing

Stevens retired on June 29, 2010 as the third-longest-serving justice in the history of the Supreme Court with 34 years and six months of service and just three days short of tying the tenure of the second-longest serving justice in history, Stephen Johnson Field, who had retired on December 1, 1897. The longest-serving justice is Stevens's immediate predecessor, Justice William O. Douglas, who served 36 years and retired on November 12, 1975. He was the last veteran of the Burger Court to remain on the bench.

Stevens was also the second-oldest justice, at age 90 years and two months at retirement, behind Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. who retired at the age of 90 years and 10 months on January 12, 1932. On July 23, 2015, Stevens became the longest-lived retired justice, surpassing Stanley Forman Reed

Stanley Forman Reed (December 31, 1884 – April 2, 1980) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1938 to 1957. He also served as U.S. Solicitor General from 1935 to 1938.

Born in Ma ...

who died at age 95 years and 93 days on April 2, 1980.

On June 26, 2015, Stevens attended the Court's announcement of the opinion in '' Obergefell v. Hodges'', in which the Court ruled 5–4 that recognition of same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same sex or gender. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 33 countries, with the most recent being Mexico, constituting ...

is protected under the Constitution's Fourteenth Amendment.

Political affiliation

When he was appointed to the Supreme Court, Stevens was a registered Republican. In September 2007, he was a sitting Justice when he was asked if he still considered himself a Republican. Stevens replied, "That's the kind of issue I shouldn't comment on, either in private or in public." Abner Mikva, a close friend, said that as a judge, Stevens refused to discuss politics. "He was more particular about it than a lot of them," Mikva stated. In 2018, Stevens told a Boca Raton crowd thatBrett Kavanaugh

Brett Michael Kavanaugh ( ; born February 12, 1965) is an American lawyer and jurist serving as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President Donald Trump on July 9, 2018, and has served since O ...

's performance during recent Senate hearings should disqualify him from the U.S. Supreme Court bench, citing the potential for political bias should he serve on the Supreme Court. Kavanaugh was nominated by Republican president Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

.

Stevens was generally considered to be one of the last-surviving Rockefeller Republicans

The Rockefeller Republicans were members of the Republican Party (GOP) in the 1930s–1970s who held moderate-to-liberal views on domestic issues, similar to those of Nelson Rockefeller, Governor of New York (1959–1973) and Vice President of ...

.

Just months before his death, Stevens spoke out against President Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

saying that "I am not a fan of President Trump" and when asked about Trump's effect on the country he stated "I don't think it's been favorable."

Judicial philosophy

On the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, Stevens had a moderately conservative record. Early in his tenure on the Supreme Court, Stevens had a relatively moderate voting record. He voted to reinstatecapital punishment in the United States

In the United States, capital punishment is a legal penalty throughout the country at the federal level, in 27 states, and in American Samoa. It is also a legal penalty for some military offenses. Capital punishment has been abolished in 23 ...

and opposed race-based admissions programs, such as the program at issue in '' Regents of the University of California v. Bakke'', . However, on the more conservative Rehnquist Court, Stevens joined the more liberal justices on issues such as abortion rights, gay rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, , ...

and federalism

Federalism is a combined or compound mode of government that combines a general government (the central or "federal" government) with regional governments ( provincial, state, cantonal, territorial, or other sub-unit governments) in a single ...

. His Segal–Cover score, a measure of the perceived liberalism/conservatism of Court members when they joined the Court, places him squarely on the conservative side of the Court. However, a 2003 statistical analysis of Supreme Court voting patterns found Stevens the most liberal member of the Court. President Ford expressed no regrets about Stevens's drift toward liberalism, writing in a 2005 letter to ''USA Today

''USA Today'' (stylized in all uppercase) is an American daily middle-market newspaper and news broadcasting company. Founded by Al Neuharth on September 15, 1982, the newspaper operates from Gannett's corporate headquarters in Tysons, Virgini ...

'', "Justice Stevens has made me, and our fellow citizens, proud of my three decade old decision to appoint him to the Supreme Court."

Stevens's jurisprudence has usually been characterized as idiosyncratic. Stevens, unlike most justices, reviewed petitions for certiorari within his chambers instead of having his law clerk

A law clerk or a judicial clerk is a person, generally someone who provides direct counsel and assistance to a lawyer or judge by researching issues and drafting legal opinions for cases before the court. Judicial clerks often play significant ...

s participate as part of the cert pool

The cert pool is a mechanism by which the Supreme Court of the United States manages the influx of petitions for certiorari ("cert") to the court. It was instituted in 1973, as one of the institutional reforms of Chief Justice Warren E. Burger on ...

and usually wrote the first drafts of his opinions himself; when asked to explain why, he said: "I'm the one hired to do the job." He further explained that he continued to learn about cases and legal theories as he drafted his opinions and re-evaluates his positions on cases while writing.

He was not an originalist (such as Antonin Scalia

Antonin Gregory Scalia (; March 11, 1936 – February 13, 2016) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1986 until his death in 2016. He was described as the intellectu ...

) nor a pragmatist (such as Judge Richard Posner), nor did he pronounce himself a cautious liberal (such as Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Joan Ruth Bader Ginsburg ( ; ; March 15, 1933September 18, 2020) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1993 until her death in 2020. She was nominated by Presiden ...

). He was considered part of the liberal bloc of the Court starting in the mid-1980s, and was dubbed the "chief justice of the liberal Supreme Court", though he publicly called himself a judicial conservative in 2007.

In 1985s '' Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center'', , Stevens argued against the Supreme Court's famous "strict scrutiny

In U.S. constitutional law, when a law infringes upon a fundamental constitutional right, the court may apply the strict scrutiny standard. Strict scrutiny holds the challenged law as presumptively invalid unless the government can demonstrate th ...

" doctrine for laws involving "suspect classifications", putting forth the view that all classifications should be evaluated using the "rational basis" test as to whether they could have been enacted by an "impartial legislature". In ''Burnham v. Superior Court of California

''Burnham v. Superior Court of California'', 495 U.S. 604 (1990), was a United States Supreme Court case addressing whether a state court may, consistent with the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, exercise personal jurisdiction over ...

'', , Stevens demonstrated his independence with a characteristically pithy concurrence.

Stevens was once an impassioned critic of affirmative action; in addition to the 1978 decision in ''Bakke'', he dissented in the case of ''Fullilove v. Klutznick

''Fullilove v. Klutznick'', 448 U.S. 448 (1980), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court held that the U.S. Congress could constitutionally use its spending power to remedy past discrimination.. The case arose as a suit against the en ...

'', , which upheld a minority set-aside program. He shifted his position over the years and voted to uphold the affirmative action program at the University of Michigan Law School challenged in 2003's '' Grutter v. Bollinger'', .

Stevens wrote the majority opinion in '' Hamdan v. Rumsfeld'' in 2006, in which he held that certain military commissions had been improperly constituted. He also wrote a lengthy dissenting opinion in '' Citizens United v. FEC'', arguing the majority should not make a decision so broad that it would overturn precedents set in three previous Supreme Court cases. When reviewing his career at the Supreme Court in his 2019 book, ''The Making of a Justice: Reflections on My First 94 Years'', Stevens lamented being unable to persuade his colleagues against the decision in ''Citizens United'', which he described as "a disaster for our election law."

Freedom of speech

Stevens's views on obscenity under theFirst Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

changed over the years. He was initially quite critical of constitutional protection for obscenity, rejecting a challenge to Detroit zoning ordinances that barred adult theaters in designated areas in ''Young v. American Mini Theatres

''Young v. American Mini Theatres'', 427 U.S. 50 (1976), is a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States upheld a city ordinance of Detroit, Michigan requiring dispersal of adult businesses throughout the city.

Justice Stevens (writing ...

'', , (" en though we recognize that the First Amendment will not tolerate the total suppression of erotic

Eroticism () is a quality that causes sexual feelings, as well as a philosophical contemplation concerning the aesthetics of sexual desire, sensuality, and romantic love. That quality may be found in any form of artwork, including painting, scu ...

materials that have some arguably artistic value, it is manifest that society's interest in protecting this type of expression is of a wholly different, and lesser, magnitude than the interest in untrammeled political debate"), but later in his tenure adhered firmly to a libertarian

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's en ...

free speech approach on obscenity issues, voting to strike down a federal law regulating online obscene content considered "harmful to minors" in '' ACLU v. Ashcroft'', . In his dissenting opinion, Stevens argued that, while " a parent, grandparent, and great-grandparent", he endorsed the legislative goal of protecting children from pornography "without reservation", " a judge, I must confess to a growing sense of unease when the interest in protecting children from prurient materials is invoked as a justification for using criminal regulation of speech as a substitute for, or a simple backup to, adult oversight of children's viewing."

Perhaps the most personal and unusual feature of his jurisprudence was his continual referencing of World War II in his opinions. For example, Stevens, a World War II veteran, was visibly angered by William Kunstler

William Moses Kunstler (July 7, 1919 – September 4, 1995) was an American lawyer and civil rights activist, known for defending the Chicago Seven. Kunstler was an active member of the National Lawyers Guild, a board member of the American Civi ...

's flippant defense of flag-burning in oral argument in '' Texas v. Johnson'', and voted to uphold a prohibition on flag-burning against a First Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

argument. Stevens wrote, "The ideas of liberty and equality have been an irresistible force in motivating leaders like Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry (May 29, 1736June 6, 1799) was an American attorney, planter, politician and orator known for declaring to the Second Virginia Convention (1775): " Give me liberty, or give me death!" A Founding Father, he served as the first a ...

, Susan B. Anthony, and Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

, schoolteachers like Nathan Hale and Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

, the Philippine Scouts

The Philippine Scouts ( Filipino: ''Maghahanap ng Pilipinas'' or ''Hukbong Maghahanap ng Pilipinas'') was a military organization of the United States Army from 1901 until after the end of World War II. These troops were generally Filipinos a ...

who fought at Bataan

Bataan (), officially the Province of Bataan ( fil, Lalawigan ng Bataan ), is a province in the Central Luzon region of the Philippines. Its capital is the city of Balanga while Mariveles is the largest town in the province. Occupying the enti ...

, and the soldiers who scaled the bluff at Omaha Beach. If those ideas are worth fighting for—and our history demonstrates that they are—it cannot be true that the flag that uniquely symbolizes their power is not itself worthy of protection from unnecessary desecration."

Stevens generally supported students' right to free speech in public schools. He wrote sharply-worded dissents in '' Bethel v. Fraser'', and '' Morse v. Frederick'', , two decisions that restricted students' freedom of speech. However, he joined the Court's ruling on ''Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier

''Hazelwood School District et al. v. Kuhlmeier et al.'', 484 U.S. 260 (1988), was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that held that public school curricular student newspapers that have not been established as forums ...

'', which upheld a principal's censorship of a student newspaper

A student publication is a media outlet such as a newspaper, magazine, television show, or radio station produced by students at an educational institution. These publications typically cover local and school-related news, but they may also rep ...

.

Establishment Clause

In ''Wallace v. Jaffree

''Wallace v. Jaffree'', 472 U.S. 38 (1985), was a United States Supreme Court case deciding on the issue of silent school prayer.

Background

An Alabama law authorized teachers to set aside one minute at the start of each day for a moment for " ...

'', , striking down an Alabama statute mandating a minute of silence in public schools "for meditation or silent prayer", Stevens wrote the opinion for a majority that included justices William Brennan, Thurgood Marshall, Harry Blackmun, and Lewis Powell. He affirmed that the Establishment Clause is binding on the States via the Fourteenth Amendment, and that: "Just as the right to speak and the right to refrain from speaking are complementary components of a broader concept of individual freedom of mind, so also the individual's freedom to choose his own creed is the counterpart of his right to refrain from accepting the creed of the majority. At one time, it was thought that this right merely proscribed the preference of one Christian sect over another, but would not require equal respect for the conscience of the infidel, the atheist, or the adherent of a non-Christian faith such as Islam or Judaism. But when the underlying principle has been examined in the crucible of litigation, the Court has unambiguously concluded that the individual freedom of conscience protected by the First Amendment embraces the right to select any religious faith or none at all."

Stevens wrote a dissent in ''Van Orden v. Perry

''Van Orden v. Perry'', 545 U.S. 677 (2005), was a United States Supreme Court case involving whether a display of the Ten Commandments on a monument given to the government at the Texas State Capitol in Austin violated the Establishment Clause ...

'', , in which he was joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg; he argued that the ten commandments displayed in the Texas Capitol

The Texas State Capitol is the capitol and seat of government of the American state of Texas. Located in downtown Austin, Texas, the structure houses the offices and chambers of the Texas Legislature and of the Governor of Texas. Designed in 188 ...

grounds transmitted the message: "This State endorses the divine code of the 'Judeo-Christian' God." The Establishment Clause, he wrote, "at the very least ... has created a strong presumption against the display of religious symbols on public property", and that it "demands religious neutrality—Government may not exercise preference for one religious faith over another". This includes a prohibition against enacting laws or imposing requirements that aid all religions as against unbelievers, or aid religions that are based on a belief in the existence of God against those founded on different principles.

Commerce clause and states' rights

When interpreting the Interstate Commerce Clause, Stevens consistently sided with thefederal government

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government ( federalism). In a federation, the self-gover ...

. He dissented in '' United States v. Lopez'', and '' United States v. Morrison'', , two prominent cases in which the Rehnquist court changed direction by holding that Congress had exceeded its constitutional power under the Commerce Clause. He then authored ''Gonzales v. Raich

''Gonzales v. Raich'' (previously ''Ashcroft v. Raich''), 545 U.S. 1 (2005), was a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that under the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution, Congress may criminalize the production and use of homegrown ca ...

'', , which permits the federal government to arrest, prosecute, and imprison patients who use medical marijuana

Medical cannabis, or medical marijuana (MMJ), is cannabis and cannabinoids that are prescribed by physicians for their patients. The use of cannabis as medicine has not been rigorously tested due to production and governmental restriction ...

regardless of whether such use is legally permissible under state law.

Fourth Amendment

Stevens had a generally libertarian voting record on the Fourth Amendment, which deals with search and seizure. Stevens authored the majority opinion in ''Arizona v. Gant

''Arizona v. Gant'', 556 U.S. 332 (2009), was a United States Supreme Court decision holding that the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution requires law enforcement officers to demonstrate an actual and continuing threat to their safet ...

'', which held that "police may search a vehicle incident to a recent occupant's arrest only if the arrestee is within reaching distance of the compartment at the time of the search or it is reasonable to believe the vehicle contains evidence of the offense of arrest." He dissented in ''New Jersey v. T. L. O.

''New Jersey v. T.L.O.'', 469 U.S. 325 (1985), is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States which established the standards by which a public school official can search a student in a school environment, and to what extent.

The ...

'', and ''Vernonia School District 47J v. Acton

''Vernonia School District 47J v. Acton'', , was a U.S. Supreme Court decision which upheld the constitutionality of random drug testing regimen implemented by the local public schools in Vernonia, Oregon. Under that regimen, student-athletes w ...

'', , both involving searches in schools. He was a dissenter in ''Oliver v. United States

''Oliver v. United States'', 466 U.S. 170 (1984), is a United States Supreme Court decision relating to the open fields doctrine limiting the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Background

Acting upon a tip that defendant was grow ...

'', , a case relating to the open-fields doctrine

The open-fields doctrine (also open-field doctrine or open-fields rule), in the U.S. law of criminal procedure, is the legal doctrine that a "warrantless search of the area outside a property owner's curtilage" does not violate the Fourth Amendme ...

. However, in ''United States v. Montoya De Hernandez

''United States v. Montoya De Hernandez'', 473 U.S. 531 (1985), was a U.S. Supreme Court case regarding the Fourth Amendment's border search exception and balloon swallowing.

Background

Rose Elvira Montoya de Hernandez entered the United States ...

'', , he sided with the government, and he was the author of ''United States v. Ross

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two fi ...

'', , which permits the police to search closed containers found in the course of searching a vehicle. He also authored the dissent in ''Kyllo v. United States

''Kyllo v. United States'', 533 U.S. 27 (2001), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States in which the court ruled that the use of thermal imaging devices to monitor heat radiation in or around a person's home, even if conducted fro ...

'', , which held that the use of thermal imaging requires a warrant.

In a 2009 paper, Ward Farnsworth

Ward Farnsworth (born 1967) is Professor of Law and holder of the W. Page Keeton Chair at the University of Texas School of Law, where he was Dean from 2012-2022. He served as Reporter for the American Law Institute’s Restatement of the Law Th ...

argued that Stevens's "dissents against type" (in Stevens's case, votes in dissent in favor of the government's position and against the accused, such as the one in ''Kyllo'') suggest that while Stevens " elievedstrongly in laying out resources for the sake of accuracy and opportunities to protest an unfair trial, e is

E, or e, is the fifth letter and the second vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''e'' (pronounced ); plura ...

not nearly as concerned about restraining the government at the front end of the process, when it is gathering evidence—for the costs of invaded rights then are to ''liberty'' rather than to ''accuracy''".

Death penalty

Stevens joined the majority in '' Gregg v. Georgia'', , which overruled '' Furman v. Georgia'', and again allowed the use of the death penalty in the United States. In later cases such as ''Thompson v. Oklahoma

''Thompson v. Oklahoma'', 487 U.S. 815 (1988), was the first case since the moratorium on capital punishment was lifted in the United States in which the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the death sentence of a minor on grounds of "cruel and unusual ...

'', and '' Atkins v. Virginia'', , Stevens held that the Constitution forbids the use of the death penalty in certain circumstances. Stevens opposed using the death penalty on juvenile offenders; he dissented in ''Stanford v. Kentucky

''Stanford v. Kentucky'', 492 U.S. 361 (1989), was a United States Supreme Court case that sanctioned the imposition of the death penalty on offenders who were at least 16 years of age at the time of the crime.. This decision came one year afte ...

'', and joined the Court's majority in '' Roper v. Simmons'', , overturning ''Stanford''. In '' Baze v. Rees'', , Stevens voted with the majority in upholding Kentucky's method of lethal injection, because he felt bound by ''stare decisis

A precedent is a principle or rule established in a previous legal case that is either binding on or persuasive for a court or other tribunal when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts. Common-law legal systems place great va ...

''. However, he opined that "state-sanctioned killing is ... becoming more and more anachronistic" and agreed with former justice Byron White

Byron "Whizzer" Raymond White (June 8, 1917 April 15, 2002) was an American professional football player and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1962 until his retirement in 1993.

Born and raised in Colo ...

's assertion that "the needless extinction of life with only marginal contributions to any discernible social or public purposes ... would be patently excessive," in violation of the Eighth Amendment (quoting from White's concurrence in ''Furman''). Soon after his vote in ''Baze'', Stevens told a Sixth Circuit conference that one of the drugs ( pancuronium bromide) in the three-drug cocktail used by Kentucky to execute death row inmates is prohibited in Kentucky for euthanizing animals. He questioned whether Kentucky Derby second-place finisher Eight Belles

Eight Belles (February 23, 2005 – May 3, 2008) was an American Thoroughbred racehorse who came second in the 2008 Kentucky Derby to the winner Big Brown. Her collapse just after the race resulted in immediate euthanasia.

Earlier in the year ...

died more humanely than those on death row. He explained that his death penalty decisions were influenced, in part, by an increasing awareness through DNA testing

Genetic testing, also known as DNA testing, is used to identify changes in DNA sequence or chromosome structure. Genetic testing can also include measuring the results of genetic changes, such as RNA analysis as an output of gene expression, ...

of the fallibility of death sentences, and the fact that death-qualified juries come with a set of biases. Stevens, at the time of his opinion in ''Baze'', was one of four justices—the others being Brennan Brennan may refer to:

People

* Brennan (surname)

* Brennan (given name)

* Bishop Brennan (disambiguation)

Places

* Brennan, Idlib, a village located in Sinjar Nahiyah in Maarrat al-Nu'man District, Idlib, Syria

* Rabeeah Brennan, a village located ...

, Marshall, and Blackmun—who had concluded that post-''Gregg'' capital punishment is unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment. After his retirement, Stevens stated that his vote in ''Gregg'' was the only vote he regretted.

Other significant opinions

''Chevron''

Stevens authored the majority opinion in ''Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.

''Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.'', 467 U.S. 837 (1984), was a landmark case in which the United States Supreme Court set forth the legal test for determining whether to grant deference to a government agency's inte ...

'', . The opinion stands for how courts review administrative agencies' interpretations of their organic statutes. If the organic statute unambiguously expresses the will of Congress, the court enforces the legislature's intent. If the statute is unclear (and is thus thought to reflect a Congressional delegation of power to the agency to interpret the statute), and the agency interpretation has the force of law, courts defer to an agency's interpretation of the statute unless that interpretation is deemed to be "arbitrary, capricious, or manifestly contrary to the statute". This doctrine is now generally referred to as "''Chevron'' deference" among legal practitioners.

Unlike some other members of the Court, Stevens was consistently willing to find organic statutes unambiguous and thus overturn agency interpretations of those statutes. (See his majority opinion in '' Immigration and Naturalization Service v. Cardoza-Fonseca'', , and his dissent in ''Young v. Community Nutrition Institute'', .) Although ''Chevron'' has come to stand for the proposition of deference to agency interpretations, Stevens, the author of the opinion, was less willing to defer to agencies than the rest of his colleagues on the Court.

''Crawford v. Marion County Election Board''

Stevens wrote the lead opinion in ''Crawford v. Marion County Election Board

''Crawford v. Marion County Election Board'', 553 U.S. 181 (2008), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that an Indiana law requiring voters to provide photographic identification did not violate the United States Constit ...

'', a case where the Court upheld the right of states to require an official photo identification card to help ensure that only citizens vote. Chief Justice John Roberts

John Glover Roberts Jr. (born January 27, 1955) is an American lawyer and jurist who has served as the 17th chief justice of the United States since 2005. Roberts has authored the majority opinion in several landmark cases, including ''Nati ...

and Justice Anthony Kennedy joined this opinion, and justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito agreed with them on the outcome. Edward B. Foley, an election law expert at Ohio State University

The Ohio State University, commonly called Ohio State or OSU, is a public land-grant research university in Columbus, Ohio. A member of the University System of Ohio, it has been ranked by major institutional rankings among the best pub ...

, said the Stevens opinion might represent an effort to "depoliticize election law cases." Stevens's vote in ''Crawford'' and his agreement with the Court's conservative majority in two other cases during the 2007–2008 term ('' Medellin v. Texas'', and '' Baze v. Rees'') led University of Oklahoma law professor and former Stevens clerk Joseph Thai to wonder if Stevens was "tacking back a little bit toward the center."

''Bush v. Gore''

In '' Bush v. Gore'', , Stevens wrote a scathing dissent on the Court's ruling to stay the recount of votes in Florida during the 2000 presidential election. He believed that the holding displayed "an unstated lack of confidence in the impartiality and capacity of the state judges who would make the critical decisions if the vote count were to proceed". He continued, "The endorsement of that position by the majority of this Court can only lend credence to the most cynical appraisal of the work of judges throughout the land. It is confidence in the men and women who administer the judicial system that is the true backbone of the rule of law. Time will one day heal the wound to that confidence that will be inflicted by today's decision. One thing, however, is certain. Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year's presidential election, the identity of the loser is perfectly clear. It is the Nation's confidence in the judge as an impartial guardian of the rule of law."Second Amendment

Stevens wrote the primary dissenting opinion in '' District of Columbia v. Heller'' , a landmark case which addressed the interpretation of the Second Amendment and theright to keep and bear arms

The right to keep and bear arms (often referred to as the right to bear arms) is a right for people to possess weapons (arms) for the preservation of life, liberty, and property. The purpose of gun rights is for self-defense, including securi ...

. ''Heller'' struck down provisions of the Firearms Control Regulations Act of 1975 and held that the Second Amendment protects an individual's right to possess a firearm

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes ...

unconnected with service in a militia for traditionally lawful purposes, such as self-defense within the home. His dissent was joined by justices David Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Joan Ruth Bader Ginsburg ( ; ; March 15, 1933September 18, 2020) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1993 until her death in 2020. She was nominated by Presiden ...

, and Stephen Breyer; the majority opinion was written by Justice Antonin Scalia

Antonin Gregory Scalia (; March 11, 1936 – February 13, 2016) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1986 until his death in 2016. He was described as the intellectu ...

.

Stevens stated that the Court's judgment was "a strained and unpersuasive reading" which overturned longstanding precedent

A precedent is a principle or rule established in a previous legal case that is either binding on or persuasive for a court or other tribunal when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts. Common-law legal systems place great v ...

, and that the Court had "bestowed a dramatic upheaval in the law." Stevens also stated that the amendment was notable for the "omission of any statement of purpose related to the right to use firearms for hunting or personal self-defense" which was present in the Declarations of Rights of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

and Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provin ...

. Stevens' dissent seems to rest on four main points of disagreement: that the Founders would have made the individual right aspect of the Second Amendment express if that was what was intended; that the "militia" preamble and exact phrase "to keep and bear arms" demands the conclusion that the Second Amendment touches on state militia service only; that many lower courts' later "collective-right" reading of the ''Miller'' decision constitutes , which may only be overturned at great peril; and that the Court has not considered gun-control laws (e.g., the National Firearms Act) unconstitutional. The dissent concludes, "The Court would have us believe that over 200 years ago, the Framers made a choice to limit the tools available to elected officials wishing to regulate civilian uses of weapons. ... I could not possibly conclude that the Framers made such a choice."

On March 27, 2018, days after the March for Our Lives demonstrations in the wake of the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting

On February 14, 2018, 19-year-old Nikolas Cruz opened fire on students and staff at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in the Miami suburban town of Parkland, Florida, murdering 17 people and injuring 17 others. Cruz, a former student at ...

, described by many media outlets as a possible tipping point for gun control legislation, Stevens wrote an essay for ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', stating that the demonstrators should be demanding the outright repeal of the Second Amendment. He wrote:

Books

In 2011, Stevens published a memoir entitled ''Five Chiefs: A Supreme Court Memoir'', which detailed his legal career during the tenure of five of the Supreme Court's chief justices. In ''Five Chiefs'', Stevens recounts his time as a law clerk during the tenure of Chief Justice Vinson; his experiences as a private attorney during the Warren era; and his experience while serving as an associate justice on the Burger, Rehnquist, and Roberts Courts. In 2014, Stevens published ''Six Amendments: How and Why We Should Change the Constitution'', where he proposed that six amendments should be added to the U.S. Constitution to address political gerrymandering, anti-commandeering, campaign finance reform,capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

, gun violence, and sovereign immunity.

In 2019, at age 99 and shortly before his death, Stevens published ''The Making of a Justice: Reflections on My First 94 Years''.

Personal life

Stevens married Elizabeth Sheeren in 1942. He was on the high court when the couple divorced thirty-seven years later in 1979. Later that same year, he married Maryan Simon; they remained married until her death in 2015. Stevens had four children, two of whom predeceased him. Stevens was aProtestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

, and upon his retirement, the Supreme Court had no Protestant members for the first time in its history. Nina Totenberg, "Supreme Court May Soon Lack Protestant Justices," NPR, ''Heard on Morning Edition'', April 7, 2010, found aNPR website

and transcript found a

NPR website

. Cited by Sarah Pulliam Bailey, "The Post-Protestant Supreme Court: Christians weigh in on whether it matters that the high court will likely lack Protestant representation," ''

Christianity Today

''Christianity Today'' is an evangelical Christian media magazine founded in 1956 by Billy Graham. It is published by Christianity Today International based in Carol Stream, Illinois. ''The Washington Post'' calls ''Christianity Today'' "evan ...

'', April 10, 2010, found aChristianity Today website

. Also cited by "Does the U.S. Supreme Court need another Protestant?" ''

USA Today

''USA Today'' (stylized in all uppercase) is an American daily middle-market newspaper and news broadcasting company. Founded by Al Neuharth on September 15, 1982, the newspaper operates from Gannett's corporate headquarters in Tysons, Virgini ...

'', April 9, 2010, found aUSA Today website

. All accessed April 10, 2010.

Richard W. Garnett

Richard W. Garnett (born November 6, 1968) is the Paul J. Schierl / Fort Howard Corporation Professor of Law, a Concurrent Professor of Political Science, and the founding Director of the Notre Dame Program on Church, State & Society at Notre Dame ...

, "The Minority Court", ''The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' is an American business-focused, international daily newspaper based in New York City, with international editions also available in Chinese and Japanese. The ''Journal'', along with its Asian editions, is published ...

'' (April 17, 2010), W3. He was one of only two Supreme Court justices who divorced while on the Court—the first was William O. Douglas, whom he coincidentally succeeded as an associate justice.

Stevens was also an avid bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually someth ...

player and belonged to the Pompano Duplicate Bridge Club Florida.

Death

Stevens died at the age of 99 from complications of a stroke inFort Lauderdale, Florida

Fort Lauderdale () is a coastal city located in the U.S. state of Florida, north of Miami along the Atlantic Ocean. It is the county seat of and largest city in Broward County, Florida, Broward County with a population of 182,760 at the 2020 Unit ...

, on July 16, 2019. He received hospice care and was with his two surviving children, Elizabeth and Susan, when he died. In addition to his two daughters, Stevens was survived by 9 grandchildren and 13 great-grandchildren. He lay in repose at the Supreme Court on July 22, 2019 before a planned burial at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

on July 23, 2019. The service was attended by all the justices on the court, as well as retired justices Anthony Kennedy and David Souter. President Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

ordered flags to fly at half-staff as a mark of respect on Tuesday, July 23, until sundown.

In popular culture

Stevens was portrayed by the actor William Schallert in the 2008 film ''Recount

An election recount is a repeat tabulation of votes cast in an election that is used to determine the correctness of an initial count. Recounts will often take place if the initial vote tally during an election is extremely close. Election reco ...

''. He was portrayed by David Grant Wright in two episodes of ''Boston Legal

''Boston Legal'' is an American legal drama and comedy drama television series created by former lawyer and Boston native David E. Kelley, produced in association with 20th Century Fox Television for ABC. The series aired from October 3, 200 ...

'' in which Alan Shore

''Boston Legal'' is an American legal-comedy-drama created by David E. Kelley. The series, starring James Spader, with Candice Bergen, and William Shatner, was produced in association with 20th Century Fox Television for the ABC. ''Boston Legal ...

and Denny Crane

''Boston Legal'' is an American legal-comedy-drama created by David E. Kelley. The series, starring James Spader, with Candice Bergen, and William Shatner, was produced in association with 20th Century Fox Television for the ABC. ''Boston Legal' ...

appear before the Supreme Court. Stevens appeared in interviews in two episodes of Ken Burns

Kenneth Lauren Burns (born July 29, 1953) is an American filmmaker known for his documentary films and television series, many of which chronicle American history and culture. His work is often produced in association with WETA-TV and/or th ...

's 2011 PBS documentary miniseries ''Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholi ...

'', recalling his childhood in Chicago in the 1920s and 30s.

According to an April 2009 article in ''The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' is an American business-focused, international daily newspaper based in New York City, with international editions also available in Chinese and Japanese. The ''Journal'', along with its Asian editions, is published ...

,'' Stevens "rendered an opinion on who wrote Shakespeare's plays," proclaiming himself an Oxfordian. That is, he believes the works ascribed to William Shakespeare actually were written by Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (; 12 April 155024 June 1604) was an English peer and courtier of the Elizabethan era. Oxford was heir to the second oldest earldom in the kingdom, a court favourite for a time, a sought-after patron o ...

. As a result, he was appointed ''Oxfordian of the Year'' by the Shakespeare Oxford Society. According to the article, Antonin Scalia

Antonin Gregory Scalia (; March 11, 1936 – February 13, 2016) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1986 until his death in 2016. He was described as the intellectu ...

and Harry Blackmun shared Stevens's belief.

Stevens was 12 years old when he was at Wrigley Field for the 1932 World Series game at which Babe Ruth

George Herman "Babe" Ruth Jr. (February 6, 1895 – August 16, 1948) was an American professional baseball player whose career in Major League Baseball (MLB) spanned 22 seasons, from 1914 through 1935. Nicknamed "the Bambino" and "the Su ...

hit his " called shot" home run. Eighty-four years later, he attended Game 4 of the 2016 World Series, also at Wrigley Field

Wrigley Field is a Major League Baseball (MLB) stadium on the North Side of Chicago, Illinois. It is the home of the Chicago Cubs, one of the city's two MLB franchises. It first opened in 1914 as Weeghman Park for Charles Weeghman's Chicago ...

, wearing a red bowtie with a Chicago Cubs

The Chicago Cubs are an American professional baseball team based in Chicago. The Cubs compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as part of the National League (NL) Central division. The club plays its home games at Wrigley Field, which is locate ...

jacket.

See also

*List of United States federal judges by longevity of service

This is a list of Article III United States federal judges by longevity of service. The judges on the lists below were presidential appointees who have been confirmed by the Senate, and who served on the federal bench for over 40 years. It inclu ...

* List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

* List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 3)

Law clerks have assisted the justices of the United States Supreme Court in various capacities since the first one was hired by Justice Horace Gray in 1882. Each justice is permitted to have between three and four law clerks per Court term. Mo ...

* List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 4)

* List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

A total of 116 people have served on the Supreme Court of the United States, the highest judicial body in the United States, since it was established in 1789. Supreme Court justices have life tenure, and so they serve until they die, resign, re ...

* United States Supreme Court cases during the Burger Court

* United States Supreme Court cases during the Rehnquist Court

* United States Supreme Court cases during the Roberts Court

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * * Rakoff, Jed S., "The Last of His Kind" (review of John Paul Stevens, ''The Making of a Justice: Reflections on My First 94 Years'', Little, Brown, 549 pp.), ''The New York Review of Books

''The New York Review of Books'' (or ''NYREV'' or ''NYRB'') is a semi-monthly magazine with articles on literature, culture, economics, science and current affairs. Published in New York City, it is inspired by the idea that the discussion of i ...

'', vol. LXVI, no. 14 (September 26, 2019), pp. 20, 22, 24. John Paul Stevens, "a throwback to the postwar liberal Republican .S. Supreme Courtappointees", questioned the validity of "the doctrine of sovereign immunity, which holds that you cannot sue any state or federal government agency, or any of its officers or employees, for any wrong they may have committed against you, unless the state or federal government consents to being sued" (p. 20); the propriety of "the increasing resistance of the U.S. Supreme Court to most meaningful forms of gun control" (p. 22); and "the constitutionality of the death penalty... because of incontrovertible evidence that innocent people have been sentenced to death." (pp. 22, 24.)

* Stevens, John Paul. "Keynote Address: The Bill of Rights: A Century of Progress." ''University of Chicago Law Review'' 59 (1992): 13online

* * * *

External links

* *at OnTheIssues

John Paul Stevens

encyclopedia article by Prof. Joseph Thai

John Paul Stevens, Human Rights Judge

by Prof. Diane Marie Amann

, by Linda Greenhouse, ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', August 25, 2005

After Stevens

Jeffrey Toobin, ''

The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

'', March 22, 2010

* The Pessimistic Legacy of John Paul Stevens

', Jeff Greenfield,

Politico

''Politico'' (stylized in all caps), known originally as ''The Politico'', is an American, German-owned political journalism newspaper company based in Arlington County, Virginia, that covers politics and policy in the United States and intern ...

, July 17, 2019

Stevens High School

named after Stevens

– slideshow by '' Salon magazine''

John Paul Stevens's Legacy in Five Cases

by '' Newsweek magazine''

Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens to Retire, PBS NewsHour

Justice Stevens a "Champion of the Constitution"

– video report by '' Democracy Now!''

Justice Stevens: An Open Mind On A Changed Court

– audio report by '' NPR'' *

Supreme Court Associate Justice Nomination Hearings on John Paul Stevens in December 1975

United States Government Publishing Office *

Arlington National Cemetery