John Mitchel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

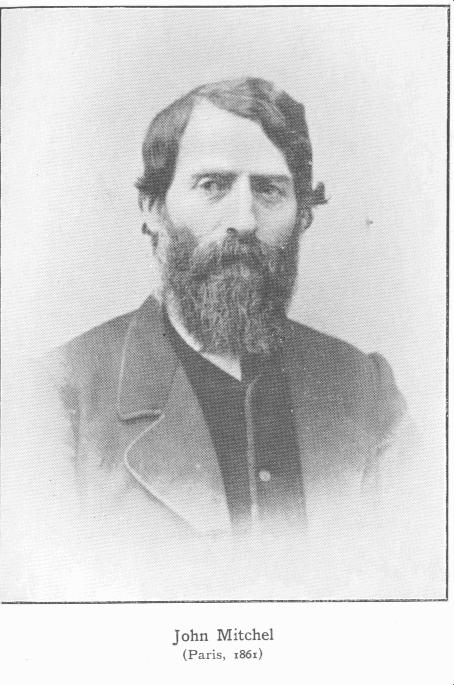

John Mitchel ( ga, Seán Mistéal; 3 November 1815 – 20 March 1875) was an Irish nationalist activist, author, and political journalist. In the Famine years of the 1840s he was a leading writer for ''The Nation'' newspaper produced by the

Duffy suggests that Mitchel had already been on a path that would see him break not only with O'Connell but also with Duffy himself and other Young Irelanders. Mitchel had fallen under the influence of Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher

Duffy suggests that Mitchel had already been on a path that would see him break not only with O'Connell but also with Duffy himself and other Young Irelanders. Mitchel had fallen under the influence of Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher

Once in the United States, Mitchel did not hesitate to repeat the claim that negroes were "an innately inferior people". In what was only the second edition the ''Irish Citizen'', he declared that it was not a crime "or even a peccadillo to hold slaves, to buy slaves, to keep slaves to their work by flogging or other needful correction", and that he himself, might wish for "a good plantation well-stocked with healthy negroes in Alabama". Subject to widely-circulated broadsides from the abolitionist

Once in the United States, Mitchel did not hesitate to repeat the claim that negroes were "an innately inferior people". In what was only the second edition the ''Irish Citizen'', he declared that it was not a crime "or even a peccadillo to hold slaves, to buy slaves, to keep slaves to their work by flogging or other needful correction", and that he himself, might wish for "a good plantation well-stocked with healthy negroes in Alabama". Subject to widely-circulated broadsides from the abolitionist

At war's end in 1864 Mitchel moved to New York and edited the ''New York Daily News''. In 1865 his continued defence of southern secession caused him to be arrested in the offices of the paper and interned at

At war's end in 1864 Mitchel moved to New York and edited the ''New York Daily News''. In 1865 his continued defence of southern secession caused him to be arrested in the offices of the paper and interned at

In July 1874 Mitchel received an enthusiastic reception in Ireland (a procession of ten thousand people escorted him to his hotel in Cork). The ''Freeman’s Journal'' opined that: "After the lapse of a quarter of a century – after the loss of two of his sons … John Mitchel again treads his native land, a prematurely aged, enfeebled man. Whatever the opinions as to the wisdom of his course … none can deny the respect due to honest of purpose and fearlessness of heart".

Back in New York City on 8 December 1874, Mitchel lectured on "Ireland Revisited" at the Cooper Institute, an event organised by the Clan-na-Gael and attended by among other prominent nationalists

In July 1874 Mitchel received an enthusiastic reception in Ireland (a procession of ten thousand people escorted him to his hotel in Cork). The ''Freeman’s Journal'' opined that: "After the lapse of a quarter of a century – after the loss of two of his sons … John Mitchel again treads his native land, a prematurely aged, enfeebled man. Whatever the opinions as to the wisdom of his course … none can deny the respect due to honest of purpose and fearlessness of heart".

Back in New York City on 8 December 1874, Mitchel lectured on "Ireland Revisited" at the Cooper Institute, an event organised by the Clan-na-Gael and attended by among other prominent nationalists

On the day Mitchel died, the Tipperary paper

On the day Mitchel died, the Tipperary paper

Young Ireland

Young Ireland ( ga, Éire Óg, ) was a political and cultural movement in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform. Grouped around the Dublin weekly ''The Nation'', it took issue with the compromise ...

group and their splinter from Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell (I) ( ga, Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilizat ...

's Repeal Association, the Irish Confederation

The Irish Confederation was an Irish nationalist independence movement, established on 13 January 1847 by members of the Young Ireland movement who had seceded from Daniel O'Connell's Repeal Association. Historian T. W. Moody described it as "th ...

. As editor of his own paper, the ''United Irishman

''The United Irishman'' was an Irish nationalist newspaper co-founded by Arthur Griffith and William Rooney.Arthur Griffith ...

'', in 1848 Mitchel was sentenced to 14-years penal transportation, the penalty for his advocacy of James Fintan Lalor

James Fintan Lalor (in Irish, Séamas Fionntán Ó Leathlobhair) (10 March 1809 – 27 December 1849) was an Irish revolutionary, journalist, and “one of the most powerful writers of his day.” A leading member of the Irish Confederation (You ...

's programme of co-ordinated resistance to exactions of landlords and to the continued shipment of harvests to England.

Controversially for a republican tradition that has viewed Mitchel, in the words of Pádraic Pearse, as a "fierce" and "sublime" apostle of Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of c ...

, in the American exile into which he escaped in 1853, Mitchel was an uncompromising pro-slavery

Proslavery is a support for slavery. It is found in the Bible, in the thought of ancient philosophers, in British writings and in American writings especially before the American Civil War but also later through 20th century. Arguments in favor o ...

partisan of the Southern secessionist cause. In the year he died, 1875, Mitchel was twice elected to the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

from Tipperary

Tipperary is the name of:

Places

*County Tipperary, a county in Ireland

**North Tipperary, a former administrative county based in Nenagh

**South Tipperary, a former administrative county based in Clonmel

*Tipperary (town), County Tipperary's na ...

on a platform of Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the e ...

, tenant rights and free education, and twice denied his seat as a convicted felon.

Early life

John Mitchel was born at Camnish near Dungiven in County Londonderry, in the province ofUlster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

. His father, Rev. John Mitchel, was a Non-subscribing Presbyterian minister of Unitarian sympathies, and his mother was Mary (née Haslett) from Maghera

Maghera (pronounced , ) is a small town at the foot of the Glenshane Pass in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. Its population was 4,220 in the 2011 Census, increasing from 3,711 in the 2001 Census. It is situated within Mid-Ulster Distri ...

. From 1823 until his death in 1840, John Sr. was minister in Newry

Newry (; ) is a City status in Ireland, city in Northern Ireland, divided by the Newry River, Clanrye river in counties County Armagh, Armagh and County Down, Down, from Belfast and from Dublin. It had a population of 26,967 in 2011.

Newry ...

, County Down. In Newry, Mitchel attended a school kept by a Dr Henderson whose encouragement and support laid the foundation for classical scholarship that at age 15 gained him entry to Trinity College, Dublin. After taking his degree at age 19 he worked briefly as a bank clerk in Derry, before entering legal practice in the office of a Newry solicitor, a friend of his father.William Dillon, ''The life of John Mitchel'' (London, 1888) 2 Vols. Ch I-II

In the spring of 1836 Mitchel met Jane "Jenny" Verner, the only daughter of Captain James Verner. Despite family opposition, and after two elopements, they became engaged in the autumn and were married in February 1837.

The couple's first child, John, was born in January the following year. Their second, James, (who was to be the father of the New York Mayor John Purroy Mitchel

John Purroy Mitchel (July 19, 1879 – July 6, 1918) was the 95th mayor of New York, from 1914 to 1917. At 34, he was the second-youngest mayor and he is sometimes referred to as "The Boy Mayor of New York." Mitchel is remembered for his sho ...

) was born in February 1840. Two further children were born, Henrietta in October 1842, and William in May 1844, in Banbridge

Banbridge ( , ) is a town in County Down, Northern Ireland. It lies on the River Bann and the A1 road and is named after a bridge built over the River Bann in 1712. It is situated in the civil parish of Seapatrick and the historic barony of Iv ...

, County Down, where as a qualified attorney Mitchel opened a new office for the Newry legal practice.

Early politics

One of Mitchel's first steps into Irish politics was to face down threats ofOrange

Orange most often refers to:

*Orange (fruit), the fruit of the tree species '' Citrus'' × ''sinensis''

** Orange blossom, its fragrant flower

*Orange (colour), from the color of an orange, occurs between red and yellow in the visible spectrum

* ...

retaliation by helping arrange, in September 1839, a public dinner in Newry for Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell (I) ( ga, Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilizat ...

, the leader of the campaign to repeal the 1800 Acts of Union and restore a reformed Irish Parliament.William Dillon, ''The Life of John Mitchel'' (London, 1888) 2 Vols. Ch III

Until his marriage, John Mitchel had by and large taken his politics from his father who, according to Mitchel's early biographer William Dillon, had "begun to comprehend the degradation of his countrymen". Soon after the granting of Catholic emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

in 1829, the O'Connellites challenged the Protestant Ascendancy

The ''Protestant Ascendancy'', known simply as the ''Ascendancy'', was the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland between the 17th century and the early 20th century by a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy, and members of th ...

in Newry by running a Catholic parliamentary candidate. Many members of the Rev. Mitchel's congregation took an active part in the elections on the side of the Ascendancy, and pressed the Rev. Mitchel to do the same. His refusal to do earned him the nickname "Papist Mitchel."

In Banbridge, Mitchel was often employed by the Catholics in the legal proceedings arising from provocative, sometimes violent, Orange incursions into their districts. Seeing how cases were handled by magistrates, who were themselves often Orangemen, enraged Mitchel's sense of justice and spurred his interest in national politics and reform.

In October 1842, his friend John Martin sent Mitchel the first copy of ''The Nation'' produced in Dublin by Charles Gavan Duffy, previously editor of the O'Connellite journal, ''The Vindicator'', in Belfast, and by Thomas Osborne Davis, and John Blake Dillon

John Blake Dillon (5 May 1814 – 15 September 1866) was an Irish writer and politician who was one of the founding members of the Young Ireland movement.

John Blake Dillon was born in the town of Ballaghaderreen, on the border of counties Ma ...

, both like himself Protestants and graduates of Trinity College. "I think ''The Nation'' will do very well", he wrote Martin, while at the same time revealing that he knew how the country "ought to take" news that an additional 20,000 British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

troops were to be deployed to Ireland but would not put it on paper for fear of arrest.

''The Nation''

Succeeds Thomas Davis

Mitchel began to write for the ''Nation'' in February 1843. He co-authored an editorial with Thomas Davis, "the Anti-Irish Catholics", in which he embraced Davis's promotion of theIrish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

and of Gaelic tradition as a non-sectarian basis for a common Irish nationality. Mitchel, however, did not share Davis's anti-clericalism

Clericalism is the application of the formal, church-based, leadership or opinion of ordained clergy in matters of either the Church or broader political and sociocultural import.

Clericalism is usually, if not always, used in a pejorative sense ...

, declining to support Davis as he sought to reverse O'Connell's opposition to the government's secular, or as O'Connell proposed "Godless", Colleges Bill.

Mitchel insisted that the government, aware that it would cause dissension, had introduced their bill for non-religious higher education to divide the national movement. But he also argued that religion is integral to education; that "all subjects of human knowledge and speculation (except abstract science)--and history most of all--are necessarily regarded from ''either'' a Catholic or a Protestant point of view, and cannot be understood or conceived at all if looked at from either, or from both". For Mitchel a cultural nationalism based on Ireland Gaelic heritage was intended not to displace the two religious traditions but rather serve as common ground between them.

When in September 1845, Davis unexpectedly died of scarlet fever, Duffy asked Mitchel to join the ''Nation'' as chief editorial writer. He left his legal practice in Newry, and brought his wife and children to live in Dublin, eventually settling in Rathmines

Rathmines () is an affluent inner suburb on the Southside of Dublin in Ireland. It lies three kilometres south of the city centre. It begins at the southern side of the Grand Canal and stretches along the Rathmines Road as far as Rathgar to t ...

. For the next two years Mitchel wrote both political and historical articles and reviews for ''The Nation''. He reviewed the ''Speeches'' of John Philpot Curran

John Philpot Curran (24 July 1750 – 14 October 1817) was an Irish orator, politician, wit, lawyer and judge, who held the office of Master of the Rolls in Ireland. He was renowned for his representation in 1780 of Father Neale, a Catholic pri ...

, a pamphlet by Isaac Butt

Isaac Butt (6 September 1813 – 5 May 1879) was an Irish barrister, editor, politician, Member of Parliament in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, economist and the founder and first leader of a number of Irish nationalist part ...

on ''The Protection of Home Industry'', ''The Age of Pitt and Fox'', and later on ''The Poets and Dramatists of Ireland'', edited by Denis Florence MacCarthy

Denis Florence MacCarthy (26 May 1817 – 9 April 1882) was an Irish poet, translator, and biographer, from Dublin.

Biography

MacCarthy was born in Lower O'Connell Street, Dublin, on 26 May 1817, and educated there and at St Patrick's College, M ...

(4 April 1846); ''The Industrial History of Free Nations'', by Torrens McCullagh, and Father Meehan's '' The Confederation of Kilkenny'' (8 August 1846).

Responds to the Famine

On 25 October 1845 Mitchel wrote on "The People's Food", pointing to the failure of the potato crop, and warning landlords that pursuing their tenants for rents would force them to sell their other crops and starve. On 8 November, in an article titled "The Detectives", he wrote, "The people are beginning to fear that the Irish Government is merely a machinery for their destruction; ... that it is unable, or unwilling, to take a single step for the prevention of famine, for the encouragement of manufactures, or providing fields of industry, and is only active in promoting, by high premiums and bounties, the horrible manufacture of crimes!".''The Nation'' newspaper, 1844 On 14 February 1846 Mitchel wrote again of the consequences of the previous autumn's potato crop losses, condemning the Government's inadequate response, and questioning whether it recognised that millions of people in Ireland who would soon have nothing to eat.Young Ireland, T.F. O'Sullivan, The Kerryman Ltd, 1945. On 28 February, he observed that the Coercion Bill, then going through theHouse of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

, was "the only kind of legislation for Ireland that is sure to meet with no obstruction in that House". However they may differ about feeding the Irish people, the one thing all English parties were agreed upon was "the policy of taxing, prosecuting and ruining them."''The Nation'' newspaper, 1846

In an article on "English Rule" on 7 March 1846, Mitchel wrote: "The Irish People are expecting famine day by day... and they ascribe it unanimously, not so much to the rule of heaven as to the greedy and cruel policy of England. ... They behold their own wretched food melting in rottenness off the face of the earth, and they see heavy-laden ships, freighted with the yellow corn their own hands have sown and reaped, spreading all sail for England; they see it and with every grain of that corn goes a heavy curse".

Break with O'Connell

In June 1846 the Whigs, with whom O'Connell had worked against theConservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

ministry of Robert Peel, returned to office under Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known by his courtesy title Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and a ...

. Invoking new laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

doctrines "political economy", they immediately set about dismantling Peel's limited, but practical, efforts to provide Ireland with food relief. O'Connell was left to plead for his country from the floor of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

: "She is in your hands—in your power. If you do not save her, she cannot save herself. One-fourth of her population will perish unless Parliament comes to their relief". A broken man, on the advice of his doctors O'Connell took himself to the continent where, on route to Rome, he died in May 1847.

In the months before O'Connell's death, Duffy circulated letters received from James Fintan Lalor

James Fintan Lalor (in Irish, Séamas Fionntán Ó Leathlobhair) (10 March 1809 – 27 December 1849) was an Irish revolutionary, journalist, and “one of the most powerful writers of his day.” A leading member of the Irish Confederation (You ...

in which he argued that independence could be pursued only in a popular struggle for the land. While he proposed that this should begin with a campaign to withhold rent, he suggested more might be implied. Parts of the country were already in a state of semi-insurrection. Tenants conspirators, in the tradition of the Whiteboys and Ribbonmen

Ribbonism, whose supporters were usually called Ribbonmen, was a 19th-century popular movement of poor Catholics in Ireland. The movement was also known as Ribandism. The Ribbonmen were active against landlords and their agents, and opposed "Or ...

, were attacking process servers, intimidating land agents, and resisting evictions. Lalor advised only against a ''general'' uprising: the people, he believed, could not hold their own against the British Army garrison in Ireland.

The letters made a profound impression on Mitchel. When the London journal the ''Standard'' observed that the new Irish railways could be used to transport troops to quickly curb agrarian unrest, Mitchel responded that the tracks could be turned into pikes and trains ambushed. O’Connell publicly distanced himself from ''The Nation, ''appearing to some to set Duffy, as the editor, up for prosecution. In the case that followed, Mitchel successfully defended Duffy in court. O'Connell and his son John were determined to press the issue. On the threat of their own resignations, they carried a resolution in the Repeal Association declaring that under no circumstances was a nation justified in asserting its liberties by force of arms.

The grouping around the ''Nation'' that O'Connell had taken to calling "Young Ireland

Young Ireland ( ga, Éire Óg, ) was a political and cultural movement in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform. Grouped around the Dublin weekly ''The Nation'', it took issue with the compromise ...

", a reference to Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (, , ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the in ...

's anti-clerical and insurrectionist Young Italy

Young Italy ( it, La Giovine Italia) was an Italian political movement founded in 1831 by Giuseppe Mazzini. After a few months of leaving Italy, in June 1831, Mazzini wrote a letter to King Charles Albert of Sardinia, in which he asked him to uni ...

, withdrew from the Repeal Association. In January 1847, they formed themselves anew as the Irish Confederation

The Irish Confederation was an Irish nationalist independence movement, established on 13 January 1847 by members of the Young Ireland movement who had seceded from Daniel O'Connell's Repeal Association. Historian T. W. Moody described it as "th ...

with, in Michael Doheny

Michael Doheny (22 May 1805 – 1 April 1862Some references give 1862: ) was an Irish writer, lawyer, member of the Young Ireland movement, and co-founder of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, an Irish secret society which would go on to launch ...

words, the "independence of the Irish nation" the objective and "no means to attain that end abjured, save such as were inconsistent with honour, morality and reason".Michael Doheny’s The Felon’s Track, M.H. Gill & Son, LTD, 1951 Edition pg 111–112 But unable to secure a pronouncement in favour of Lalor's policy, making control of land the issue in a campaign of resistance, Mitchel soon broke with his confederates.

Influence of Carlyle

Duffy suggests that Mitchel had already been on a path that would see him break not only with O'Connell but also with Duffy himself and other Young Irelanders. Mitchel had fallen under the influence of Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher

Duffy suggests that Mitchel had already been on a path that would see him break not only with O'Connell but also with Duffy himself and other Young Irelanders. Mitchel had fallen under the influence of Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

, who was notorious for his antipathy toward liberal notions of enlightenment and progress.

In the ''Nation'' of 10 January 1846, Mitchel reviewed ''Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches

''Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches: with Elucidations'' is a book by the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle. It "remains one of the most important works of British history published in the nineteenth and twentieth ...

'' (1845), a book by Carlyle that had been publicly condemned by O'Connell only two weeks prior. Despite Mitchel himself waxing indignant at Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

's conduct in Ireland, Carlyle was pleased: he believed Mitchel had conceded Cromwell's essential greatness. Mitchel had just published his own hagiography of the Ulster rebel chieftain Hugh O'Neill, which both Duffy and Davis had found excessively "Carlylean". Mitchel's book was a success: "an early incursion of Carlylean thought into the romantic construction of the Irish nation that was to dominate militant Irish politics for a century." It embraced views which Carlyle had espoused in ''On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History

''On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History'' is a book by the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, published by James Fraser, London, in 1841. It is a collection of six lectures given in May 1840 about prominent ...

'' (1841) and denounced British imperialism and suppression of Irish culture "in the name of Civilisation".

When in May 1846 Mitchel first met Carlyle in a delegation with Duffy in London, he wrote to John Martin describing the Scotsman's presence as "royal, almost Godlike", and did so even while acknowledging Carlyle's unbending unionism.

Hosted by Mitchel in September 1846 in Dublin, Carlyle recalled "a fine elastic-spirited young fellow, whom I grieved to see rushing to destruction ..., but upon whom all my persuasions were thrown away". Carlyle later said, when Mitchel was on trial, "Irish Mitchel, poor fellow… I told him he would most likely be hanged, but I told him, too, that they could not hang the immortal part of him."

The ''United Irishman''

At the end of 1847 Mitchel resigned his position as leader writer on ''The Nation''. He later explained that he had come to regard as "absolutely necessary a more vigorous policy against the English Government than that whichWilliam Smith O'Brien

William Smith O'Brien ( ga, Liam Mac Gabhann Ó Briain; 17 October 1803 – 18 June 1864) was an Irish nationalist Member of Parliament (MP) and a leader of the Young Ireland movement. He also encouraged the use of the Irish language. He ...

, Charles Gavan Duffy and other Young Ireland

Young Ireland ( ga, Éire Óg, ) was a political and cultural movement in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform. Grouped around the Dublin weekly ''The Nation'', it took issue with the compromise ...

leaders were willing to pursue". He "had watched the progress of the famine policy of the Government, and could see nothing in it but a machinery, deliberately devised, and skilfully worked, for the entire subjugation of the island—the slaughter of portion of the people, and the pauperization of the rest," and he had therefore "come to the conclusion that the whole system ought to be met with resistance at every point."

While he would admit no principle that distinguished his position from the "conspirators of Ninety-Eight" (the original United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association in the Kingdom of Ireland formed in the wake of the French Revolution to secure "an equal representation of all the people" in a national government. Despairing of constitutional refor ...

), Mitchel emphasised that he was not recommending "an immediate insurrection": in the "present broken and divided condition" of the country "the people would be butchered". With Finton Lalor he urged "passive resistance": the people should "obstruct and render impossible the transport and shipment of Irish provisions" and, by intimidation, to suppress bidding for grain or cattle if brought "to auction under distress", a method that had demonstrated its effectiveness in the Tithe War

The Tithe War ( ga, Cogadh na nDeachúna) was a campaign of mainly nonviolent civil disobedience, punctuated by sporadic violent episodes, in Ireland between 1830 and 1836 in reaction to the enforcement of tithes on the Roman Catholic majority ...

. Such actions would be illegal, but such was his opposition to British rule

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was hims ...

that in Mitchel's view, no opinion in Ireland was "worth a farthing

Farthing or farthings may refer to:

Coinage

*Farthing (British coin), an old British coin valued one quarter of a penny

** Half farthing (British coin)

** Third farthing (British coin)

** Quarter farthing (British coin)

* Farthing (English ...

which is not illegal".

The first number of Mitchel's own paper, '' The United Irishman'', appeared on 12 February 1848. The Prospectus announced that as editor Mitchel would be "aided by Thomas Devin Reilly, John Martin of Loughorne and other competent contributors" who were likewise convinced that "Ireland really and truly wants to be freed from English dominion." Under the masthead Mitchel ran the words of Wolfe Tone

Theobald Wolfe Tone, posthumously known as Wolfe Tone ( ga, Bhulbh Teón; 20 June 176319 November 1798), was a leading Irish revolutionary figure and one of the founding members in Belfast and Dublin of the United Irishmen, a republican soci ...

: "Our independence must be had at all hazards. If the men of property will not support us, they must fall; we can support ourselves by the aid of that numerous and respectable class of the community, the men of no property."

''The United Irishman'' declared as its doctrine... that the Irish people had a distinct and indefeasible right to their country, and to all the moral and material wealth and resources thereof, ... as a distinct Sovereign State; ... that the life of one peasant was as precious as the life of one nobleman or gentleman; that the property of the farmers and labourers of Ireland was as sacred as the property of all the noblemen and gentlemen in Ireland, and also immeasurably more valuable; ndthat every freeman, and every man who desired to become free, ought to have arms, and to practise the use of them".In the first editorial, addressed to "The Right Hon. the Earl of Clarendon, Englishman, calling himself Her Majesty's Lord Lieutenant – General and General Governor of Ireland," Mitchel stated that the purpose of the journal was to resume the struggle which had been waged by Tone and Emmet, the Holy War to sweep this Island clear of the English name and nation." Lord Clarendon was also addressed as "Her Majesty's Executioner-General and General Butcher of Ireland".''The United Irishman'', 1848 Commenting on this first edition of ''The United Irishman'',

Lord Stanley

Earl of Derby ( ) is a title in the Peerage of England. The title was first adopted by Robert de Ferrers, 1st Earl of Derby, under a creation of 1139. It continued with the Ferrers family until the 6th Earl forfeited his property toward the en ...

in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

, on 24 February 1848, maintained that the paper pursued "the purpose of exciting sedition and rebellion among her Majesty's subjects in Ireland..., and to promote civil war for the purpose of exterminating every Englishman in Ireland". He allowed that the publishers were "honest" men: "they are not the kind of men who make their patriotism the means of barter for place or pension. They are not to be bought off by the Government of the day for a colonial place, or by a snug situation in the customs or excise. No; they honestly repudiate this course; they are rebels at heart, and they are rebels avowed, who are in earnest in what they say and propose to do".P.A. Sillard, ''Life of John Mitchel'', James Duffy and Co. Ltd, 1908

Only 16 editions of ''The United Irishman'' had been produced when Mitchel was arrested, and the paper suppressed. Mitchel concluded his last article in ''The United Irishman'', from Newgate prison, entitled "A Letter to Farmers",ygallant Confederates ... have marched past my prison windows to let me know that there are ten thousand fighting men in Dublin— 'felons' in heart and soul. I thank God for it. The game is afoot, at last. The liberty of Ireland may come sooner or come later, by peaceful negotiation or bloody conflict— but it is sure; and wherever between the poles I may chance to be, I will hear the crash of the down fall of the thrice-accursedBritish Empire The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...."

Arrest and deportation

On 15 April 1848, a grand jury was called on to indict not only Mitchel, but also his former associates on the ''Nation'' O'Brien and Meagher for "seditious libels". When the cases against O'Brien and Meagher fell through, thanks in part toIsaac Butt

Isaac Butt (6 September 1813 – 5 May 1879) was an Irish barrister, editor, politician, Member of Parliament in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, economist and the founder and first leader of a number of Irish nationalist part ...

's able defence, under new legislation the government replaced the charges against Mitchel with Treason Felony

The Treason Felony Act 1848 (11 & 12 Vict. c. 12) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Parts of the Act are still in force. It is a law which protects the King and the Crown.

The offences in the Act w ...

punishable by transportation for life. To justify the severity of the new measures, under which Mitchel was arrested in May, the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

thought it sufficient to read extracts from Mitchel's articles and speeches.Four Years of Irish History 1845–1849, Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co. 1888

Convicted in June by a jury he dismissed as "packed" (as "not empanelled even according to the law of England"), Mitchel was sentenced to be "transported beyond the seas for the term of fourteen years." From the dock he declared that he was satisfied that he had "shown what the law is made of in Ireland", and that he regretted nothing: "the course which I have opened is only commenced". Others would follow.

Mitchel was first transported to Ireland Island in the "Imperial fortress

Imperial fortress was the designation given in the British Empire to four colonies that were located in strategic positions from each of which Royal Navy squadrons could control the surrounding regions and, between them, much of the planet.

His ...

" of Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = "Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, es ...

(arriving on 20 June 1848, aboard the steamer HMS Scourge, and imprisoned in the Prison hulk

A prison ship, often more accurately described as a prison hulk, is a current or former seagoing vessel that has been modified to become a place of substantive detention for convicts, prisoners of war or civilian internees. While many nation ...

HMS Dromedary), where, under harsh conditions, the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

was using convict labour to carve out a dockyard and naval base. Mitchel wore a prisoner's uniform with ''his name and number (1922) in large characters upon his back''. Surviving his time in Bermuda, in 1850 Mitchel was then sent to the penal colony of Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sep ...

(modern-day Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

, Australia), on board the '' Neptune'', where he re-joined O'Brien and Meagher, and other Young Irelanders, convicted in the wake of their abortive July 1848 rising. Aboard ship, he began writing his ''Jail Journal'', in which he reiterated his call for national unity and resistance. After being granted a ticket of leave in Tasmania, he and Martin lived together at Bothwell, in a house still known as Mitchel's Cottage. His wife and children joined him in Bothwell in June 1851.

United States

Mitchel, aided byPatrick James Smyth

Patrick James Smyth (Irish name O'Gowan or ''Mac Gabhainn''; 1823/1826 – 12 January 1885), also known as Nicaragua Smyth, was an Irish politician and journalist. A Young Irelander in 1848, and subsequently a journalist in American exile, fro ...

, escaped from Van Diemen's Land in 1853 and made his way (via Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austra ...

, San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

, Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the countr ...

and Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

) to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

. There, in January 1854, he began publishing the ''Irish Citizen'' but outlived the hero's welcome he had received. His defence of slavery in the southern states was "the subject of much surprise and general rebuke", while his advocacy of European revolution alienated the Catholic Church hierarchy.

Pro-slavery Confederate

Once in the United States, Mitchel did not hesitate to repeat the claim that negroes were "an innately inferior people". In what was only the second edition the ''Irish Citizen'', he declared that it was not a crime "or even a peccadillo to hold slaves, to buy slaves, to keep slaves to their work by flogging or other needful correction", and that he himself, might wish for "a good plantation well-stocked with healthy negroes in Alabama". Subject to widely-circulated broadsides from the abolitionist

Once in the United States, Mitchel did not hesitate to repeat the claim that negroes were "an innately inferior people". In what was only the second edition the ''Irish Citizen'', he declared that it was not a crime "or even a peccadillo to hold slaves, to buy slaves, to keep slaves to their work by flogging or other needful correction", and that he himself, might wish for "a good plantation well-stocked with healthy negroes in Alabama". Subject to widely-circulated broadsides from the abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher

Henry Ward Beecher (June 24, 1813 – March 8, 1887) was an American Congregationalist clergyman, social reformer, and speaker, known for his support of the abolition of slavery, his emphasis on God's love, and his 1875 adultery trial. His r ...

and the French republican exile Alexandre Holinski, the remarks triggered a public furore. In Dublin, the Irish Confederation

The Irish Confederation was an Irish nationalist independence movement, established on 13 January 1847 by members of the Young Ireland movement who had seceded from Daniel O'Connell's Repeal Association. Historian T. W. Moody described it as "th ...

convened an emergency meeting to protest reports in the American and British press which "erroneously attributed" Michel's pro-slavery

Proslavery is a support for slavery. It is found in the Bible, in the thought of ancient philosophers, in British writings and in American writings especially before the American Civil War but also later through 20th century. Arguments in favor o ...

sentiments "to the Young Ireland party".

When Carlyle and others indulged in derogatory comparisons between Irish cottiers and the allegedly-indolent descendants of West Indian slaves, Mitchel response had not been to join O'Connell in proclaiming himself "the friend of liberty in every clime, class and color" Rather, it was to insist on a racial distinction between the Irish and the "negro". This Duffy had discovered in 1847 when he conceded temporary editorship of the ''Nation'' to Mitchel. He found that he had lent a journal, "recognised throughout the world as the mouthpiece of Irish rights", to "the monstrous task of applauding negro slavery and of denouncing the emancipation of the Jews" (another of O'Connell's liberal causes against which Mitchel stood with Carlyle).

It was not only that Mitchel claimed (as others had done) that Irish cottiers were treated worse than black slaves. Nor was it that Mitchel decried as inopportune O'Connell's harping upon "the vile union" in the United States "of republicanism and slavery". Duffy himself was fearful of the impact of O'Connnell's vocal abolitionism upon American support and funding. It was that Mitchel argued (with Carlyle) that slavery was "the best state of existence for the negro".

Provoked by the nativist hostility they encountered in the United States, Mitchel was to further distance his countrymen from the African American by elevating them within the white race. In 1858 he told an audience in New York that "nearly all the great men which Europe has produced have been Celts".

In correspondence with his friend, the Roman Catholic priest John Kenyon, Mitchel revealed his wish to make the people of the U.S. "proud and fond of lavery

Lavery, also spelled Lowry, Lowrie, Lory, Lavoy and Lowery, is an Irish surname derived from the Gaelic ''Ó Labhradha'', meaning the "descendants of Labhradha".

The Ó Labhradha descend from Labhradh, who was the father of Etru, chief of the Mona ...

as a national institution, and oadvocate its extension by re-opening the trade in Negroes". Slavery he promoted for "its own sake". It was "good in itself" for "to enslave fricansis impossible or to set them free either. They are born and bred slaves". The Catholic Church might condemn the "enslavement of men", but this censure could not apply to "negro slaves".

The value and virtue of slavery, "both for negroes and white men", Mitchel maintained from 1857 in the pages of the ''Southern Citizen'', a paper he moved in 1859 from Knoxville, Tennessee

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division and the state' ...

to Washington D.C. The paper circulated widely through Hibernian societies of the south. Among these it was commonplace to propose that the American slave had nothing to envy in the freedom of the Irish tenant-at-will, the cottier family in Ireland that the landlord might set out in the roadside ditch.

Mitchel's wife, Jenny, had her reservations. Nothing, she said, would induce her "to become the mistress of a slave household". Her objection to slavery was "the injury it does to the white masters". There is no record or suggestion of Mitchel, himself, holding any person in bondage. When he briefly farmed in eastern Tennessee it was from a log cabin and, reportedly, with a "colored man" employed only "if he could not get a white man to work".

While championing the South, in the summer of 1859 Mitchel detected the possibility of a breach between France and England, from which Ireland might benefit. He travelled to Paris as an American correspondent, but found the talk of war had been much exaggerated. After the secession from the American Union of several Southern states in February 1861 and the bombardment of Fort Sumter (during which his son John commanded a South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

battery), Mitchel was anxious to return. He reached New York in September and made his way to the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia. There he edited the ''Daily Enquirer'', the semi-official organ of secessionists' president, Jefferson Davis.

Mitchel drew a parallel between the American South and Ireland: both were agricultural economies tied to an unjust union. The Union States and England were "''..the commercial, manufacturing and money-broking power ... greedy, grabbing, griping and grovelling''". Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

he described as "... an ignoramus and a boor; not an apostle at all; no grand reformer, not so much as an abolitionist, except by accident – a man of very small account in every way."

The Mitchels lost both their youngest son Willie in the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

in July 1863, and their son John, returned to Fort Sumter, in July the following year.

After the reverse at Gettysburg Mitchel became increasingly disillusioned with Davis's leadership. In December 1863 he resigned from the ''Enquirer'' and became the leader writer for the ''Richmond Examiner'', regularly attacking Davis for what he saw as misplaced chivalry, especially his failure to retaliate in kind for Federal attacks on civilians.

On slavery, Mitchel remained uncompromising. As the South's manpower reserves depleted, Generals Robert E. Lee and Patrick Cleburne

Major-General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne ( ; March 16, 1828November 30, 1864) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded infantry in the Western Theater of the American Civil War.

Born in Ireland, Cleburne served in the 4 ...

(a native of County Cork) proposed that slaves should be offered their freedom in return for military service. Although he had been among the first to claim that slavery had not been the cause of the conflict but simply the pretext for northern aggression, Mitchel objected: to allow blacks their freedom was to concede that the South had been in the wrong from the start. His biographer Anthony Russell notes that it was "with no trace of irony at all", that Mitchel wrote:

...if freedom be a reward for negroes – that is, if freedom be a good thing for negroes – why, then it is, and always was, a grievous wrong and crime to hold them in slavery at all. If it be true that the state of slavery keeps these people depressed below the condition to which they could develop their nature, their intelligence, and their capacity for enjoyment, and what we call "progress" then every hour of their bondage for generations is a black stain upon the white race.This might have suggested that Mitchel was open to revising his view of slavery. But he remained defiant to the end, going so far as to "raise the blasphemous doubt" as to whether General Robert E. Lee was "a 'good Southerner'; that is whether he is thoroughly satisfied of the justice and beneficence of negro slavery". Mitchel would make no allowances. After the war a Union officer who claimed to have "loved John Mitchel, the Irish patriot, with a purer devotion" than any in Ireland, reported to a Boston paper that, when, as prisoners in Richmond, he and a fellow Irishman contacted his former idol, not only did Mitchel refuse to have anything to do with "Lincoln's hirelings," but in the next issue of the ''Examiner'' he "directed the citizens to treat this human fungi not as prisoners of war, but as 'robbers, murderers and assassins!'"

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

, who in visiting Ireland believed her dispossessed were bound in sorrow at their circumstances with the enslaved in America, accounted Mitchel a “vulgar traitor to liberty.”

At odds with Irish America

Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe, managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth of Virginia, the National Park Service as the Fort Monroe National Monument, and the City of Hampton, is a former military installation in Hampton, Virgi ...

, Virginia, where Jefferson Davis and Senator Clement Claiborne Clay (accused of conspiracy to assassinate Lincoln) were the only other prisoners. His release was secured on condition that he left America. Mitchel returned to Paris where he acted as financial agent for the Fenians. But by 1867 he was back in New York resuming the publication of the ''Irish Citizen''.

Mitchel's anti-Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, pro-Democratic editorial line was opposed in New York by another Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

Protestant, the IRB exile David Bell. Bell's "Journal of Liberty, Literature, and Social Progress", ''Irish Republic,'' cautioned readers "interested in the labor question" from associating themselves with John Mitchel. Mitchel, a "miserable man", was the proponent of a "diabolical" Democratic Party plan to impose upon blacks in the South, "as a substitute for chattel slavery, a system of serfdom scarcely less hateful than the institution it is intended to practically prolong". The policy was nothing less than "an attempt to attach to the laborer in America those medieval conditions which even Russia Emancipation_of_the_Serfs,_1861_.html" ;"title="Emancipation reform of 1861">Emancipation of the Serfs, 1861 ">Emancipation reform of 1861">Emancipation of the Serfs, 1861 has rejected".

The revived ''Citizen'' failed to attract readers and folded in 1872; Bell's ''Irish Republic'' followed a year later. Neither paper was in sympathy with the ethnic-minority Catholicism powerfully represented by the city's Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

Democratic-Party political machine and, until his death in 1864, by the authority of a third Ulsterman, Archbishop John Hughes. Mitchel dedicated his paper to "aspirants to the privileges of American citizenship", arguing that the more integrated (or "more lost") among American citizens the Irish in America were "the better".

Hughes, like Mitchel, had suggested that the conditions of "starving laborers" in the North were often worse than that of slaves in the South, and in 1842 he had urged his flock not to sign O'Connell's abolitionist petition ("An Address of the People of Ireland to their Countrymen and Countrywomen in America") which he regarded as unnecessarily provocative. Hughes nonetheless used Mitchel's stance on slavery to discredit him: as Mitchel saw it, "copying the abolition press to cast an Alabama plantation" in his "teeth".

Final campaign: Tipperary elections

Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa

Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa ( ga, Diarmaid Ó Donnabháin Rosa; baptised 4 September 1831, died 29 June 1915)Con O'Callaghan Reenascreena Community Online (dead link archived at archive.org, 29 September 2014) was an Irish Fenian leader and member ...

. While his visit to Ireland was ostensibly private, Mitchel revealed that he had pressed to stand for British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

and that it was his intention, if any vacancy should occur, to offer himself as a candidate so that he might "get the Irish members to put in operation the plan suggested by O’Connell at one time, of declining to attend in Parliament altogether, that is, to try to discredit and explode the fraudulent pretence of representation in the Parliament of Britain". In the same speech, Mitchel dismissed the Irish Home Rule movement

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for Devolution, self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1 ...

: "the fact that this Home Rule League is friend John Martin among themgoes to Parliament and sets it hope therein, puts me in indignation against the Home Rule League

The Home Rule League (1873–1882), sometimes called the Home Rule Party, was an Irish political party which campaigned for home rule for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, until it was replaced by the Irish Parliam ...

… they are not Home Rulers but Foreign Rulers. Now it is painful for me to say even so much in disparagement of so excellent a body of men as they are … after a little while they will be bought".

The call from Ireland came sooner than expected. In January 1875 a bye-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election (Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to f ...

was called for a parliamentary seat in Tipperary. Stung by his remarks in New York, the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nation ...

was reluctant to endorse Mitchel's nomination. although they may have been confused as to his position. Before re-embarking for Ireland, Mitchel issued an election address in which he appeared to endorse Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

—together with free education, universal tenant rights, and the freeing of Fenian prisoners. As it was, on 17 February, while still approaching the Irish shore, Mitchel was elected unopposed. As had been the case for O'Donovan Rossa who had been returned for very same constituency in 1869, his election was unavailing. On the motion of Benjamin Disraeli, the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

by a large majority declared Mitchel, as a felon, ineligible. Mitchel ran again as an Independent Nationalist in the resulting March by-election, and in a contest took 80 percent of the vote.

Mitchel died at Drumalane, his parents' house in Newry, on 20 March 1875. His last letter, published on St. Patrick's Day, 17 March 1875, expressed his gratitude to the voters of Tipperary for supporting him in exposing the 'fraudulent' system of Irish representation in Parliament. An election petition

An election petition refers to the procedure for challenging the result of a Parliamentary election.

Outcomes

When a petition is lodged against an election return, there are 4 possible outcomes:

# The election is declared void. The result is q ...

had been lodged. Observing that voters in Tipperary had known that Mitchel was ineligible, the courts awarded the seat to Mitchel's Conservative opponent. At Mitchel's funeral in Newry, his friend John Martin collapsed, and died a week later.

Commemoration

On the day Mitchel died, the Tipperary paper

On the day Mitchel died, the Tipperary paper The Nenagh Guardian

''The Nenagh Guardian'' is a weekly local newspaper that circulates in County Tipperary, Ireland. The newspaper is based in Nenagh, County Tipperary, but is printed by the ''Limerick Leader'' in Limerick. The title incorporates two previous loca ...

offered "An American View of John Mitchel": a syndicated piece from the Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television a ...

that declared Mitchel a "recreant to liberty", a defender of slavery and secession with whom "the Union masses of the American people" could have "little sympathy". Obituaries for Mitchel looked elsewhere to qualify their acknowledgement of his patriotic devotion.

The Home-Rule ''Freeman’s Journal'' wrote of Mitchel: "we may lament his persistence in certain lines of action which his intelligence must have suggested to him could have but been futile issue … his love for Ireland may have been imprudent. But he loved her with a devotion unexcelled". The ''Standard'', with which Mitchel had contended in 1847, concluded: "His powers through life, however, were marred by want of judgment, obstinate opinionativeness, and a factiousness which disabled him from ever acting long enough with any set of men".

Pádraic Pearse's placed Mitchel in succession to Theobald Wolfe Tone

Theobald Wolfe Tone, posthumously known as Wolfe Tone ( ga, Bhulbh Teón; 20 June 176319 November 1798), was a leading Irish revolutionary figure and one of the founding members in Belfast and Dublin of the United Irishmen, a republican socie ...

, Thomas Davis, and James Fintan Lalor

James Fintan Lalor (in Irish, Séamas Fionntán Ó Leathlobhair) (10 March 1809 – 27 December 1849) was an Irish revolutionary, journalist, and “one of the most powerful writers of his day.” A leading member of the Irish Confederation (You ...

and hailed Mitchel's "gospel of Irish nationalism" as the "fiercest and most sublime". Pearse's eulogy was seconded by the Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur G ...

leader Arthur Griffith

Arthur Joseph Griffith ( ga, Art Seosamh Ó Gríobhtha; 31 March 1871 – 12 August 1922) was an Irish writer, newspaper editor and politician who founded the political party Sinn Féin. He led the Irish delegation at the negotiations that prod ...

.

In the decades following his death, branches of the Irish National Land League

The Irish National Land League (Irish: ''Conradh na Talún'') was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which sought to help poor tenant farmers. Its primary aim was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farmer ...

were named in Mitchel's honour. There are at least ten Gaelic Athletic Association

The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA; ga, Cumann Lúthchleas Gael ; CLG) is an Irish international amateur sports, amateur sporting and cultural organisation, focused primarily on promoting indigenous Gaelic games and pastimes, which include t ...

clubs named after Mitchel, including one based in his home town, Newry

Newry (; ) is a City status in Ireland, city in Northern Ireland, divided by the Newry River, Clanrye river in counties County Armagh, Armagh and County Down, Down, from Belfast and from Dublin. It had a population of 26,967 in 2011.

Newry ...

and two in County Londonderry, his county of birth – one in Claudy

Claudy () is a village and townland (of 1,154 acres) in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. It lies in the Faughan Valley, southeast of Derry, where the River Glenrandal joins the River Faughan. It is situated in the civil parish of Cumber U ...

and another in Glenullin. Mitchel Park is named after him in Dungiven, near his birthplace, as is Mitchell County, Iowa

Mitchell County is a county located in the U.S. state of Iowa. As of the 2020 census, the population was 10,565. The county seat is Osage. It is not clear whom the county is named after: the county website mentions John Mitchell, an early surv ...

, in the United States. Fort Mitchel on Spike Island, Cork from which he was transported in 1848 is named in his honour.

In 2020 a petition was launched, receiving over 1,200 signatures, calling for a statue of Mitchel in the centre of Newry to be removed, and John Mitchel Place, in which it stands, to be renamed to "Black Lives Matter Plaza". Council officers agreed only to "proceed to clarify responsibility for the John Mitchel statue, develop options for an education programme, identify the origins of John Mitchel Place and give consideration as to other potential issues in relation to slavery within the council area".

Mitchel's recent biographer, Anthony Russell argues that Mitchel's stand on slavery was not an aberration. His rejection of philanthropic liberalism was equal to his disdain for "free labour" political economy. In his ''Jail Journal'' Mitchel urged capital punishment for crimes such as burglary, forgery and robbery. The "reformation of offenders" was not, he argued, "the reasonable object of criminal punishment": "Why hang them, hang them….you have no right to make the honest people support the rogues….and for 'ventilation'… I would ventilate the rascals in front of the county jails at the end of a rope".

As for slavery in the American South, Dillon, another biographer, proposed that for Mitchel it was a "practical issue". Faced with the alternative of a social system of the North in which the relation of master to servant was regulated by competition, "He took his stand in favour of the system that seemed to him the better of the two; and as was his habit, he took it decisively".

Mitchel is remembered for his involvement in radical nationalism, and in particular for writings such as "Jail Journal", "The Last Conquest of Ireland (Perhaps)", "The History of Ireland", "An Apology for the British Government in Ireland", and the less well known "The Life and times of Hugh O'Neill". He was described by Charles Gavan Duffy as "a trumpet to awake the slothful to the call of duty; and the Irish people".

Books by John Mitchel

*''The Life and Times of Hugh O'Neill'', James Duffy, 1845 *''Jail Journal, or, Five Years in British Prisons'', Office of the "Citizen", New York, 1854 *''Poems of James Clarence Mangan'' (Introduction), P. M. Haverty, New York, 1859 *''An Apology for the British Government in Ireland'', Irish National Publishing Association, 1860 *''The History of Ireland, from the Treaty of Limerick to the Present Time'', Cameron & Ferguson, Glasgow, 1864 *''The Poems of Thomas Davis'' (Introduction), D. & J. Sadlier & Co., New York, 1866 *''The Last Conquest of Ireland (Perhaps)'', Lynch, Cole & Meehan 1873 (originally appeared in the ''Southern Citizen'', 1858) *''The Crusade of the Period'', Lynch, Cole & Meehan 1873 *''Reply to the Falsification of History by James Anthony Froude, Entitled 'The English in Ireland, Cameron & Ferguson n.d. *References

Further reading

Biographies of Mitchel

* ''The life of John Mitchel'', William Dillon, (London, 1888) 2 Vols. *''Life of John Mitchel'', P.A. Sillard, James Duffy and Co., Ltd 1908 *''John Mitchel: An Appreciation'', P.S. O'Hegarty, Maunsel & Company, Ltd 1917 *''Mitchel's Election a National Triumph'', Charles J. Rosebault, J. Duffy, 1917 *''Irish Mitchel'', Seamus MacCall, Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd 1938 *''John Mitchel: First Felon for Ireland'', Edited By Brian O'Higgins, Brian O'Higgins 1947 *''John Mitchel Noted Irish Lives'', Louis J. Walsh, The Talbot Press Ltd 1934 *''John Mitchel, Ó Cathaoir, Brendan (Clódhanna Teoranta, Dublin, 1978) *''John Mitchel, A Cause Too Many'', Aidan Hegarty, Camlane Press 2005 *''John Mitchel: Irish Nationalist, Southern Secessionist'', Bryan McGovern, (Knoxville, 2009) * ''Between Two Flags: John Mitchel & Jenny Verner'', Anthony Russell (Dublin, Merion Press, 2015)External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Mitchel, John 1815 births 1875 deaths 19th-century Irish people Convicts transported to Australia Irish journalists Irish Presbyterians Irish solicitors Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Tipperary constituencies (1801–1922) People from County Londonderry People of the American Civil War UK MPs 1874–1880 Ulster Scots people Young Irelanders Proslavery activists 19th-century journalists Male journalists Irish emigrants to the United States (before 1923) Convict escapees in Australia People convicted of treason against the United Kingdom Protestant Irish nationalists 19th-century Irish businesspeople