John Milton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an

John Milton was born in Bread Street, London, on 9 December 1608, the son of composer John Milton and his wife Sarah Jeffrey. The senior John Milton (1562–1647) moved to London around 1583 after being disinherited by his devout

John Milton was born in Bread Street, London, on 9 December 1608, the son of composer John Milton and his wife Sarah Jeffrey. The senior John Milton (1562–1647) moved to London around 1583 after being disinherited by his devout

Milton continued to write poetry during this period of study; his '' Arcades'' and '' Comus'' were both commissioned for masques composed for noble patrons, connections of the Egerton family, and performed in 1632 and 1634 respectively. ''Comus'' argues for the virtuousness of

Milton continued to write poetry during this period of study; his '' Arcades'' and '' Comus'' were both commissioned for masques composed for noble patrons, connections of the Egerton family, and performed in 1632 and 1634 respectively. ''Comus'' argues for the virtuousness of

On returning to England where the Bishops' Wars presaged further armed conflict, Milton began to write prose tracts against episcopacy, in the service of the

On returning to England where the Bishops' Wars presaged further armed conflict, Milton began to write prose tracts against episcopacy, in the service of the

In October 1649, he published '' Eikonoklastes'', an explicit defence of the regicide, in response to the '' Eikon Basilike'', a phenomenal best-seller popularly attributed to Charles I that portrayed the King as an innocent Christian

In October 1649, he published '' Eikonoklastes'', an explicit defence of the regicide, in response to the '' Eikon Basilike'', a phenomenal best-seller popularly attributed to Charles I that portrayed the King as an innocent Christian

Cromwell's death in 1658 caused the English Republic to collapse into feuding military and political factions. Milton, however, stubbornly clung to the beliefs that had originally inspired him to write for the Commonwealth. In 1659, he published ''

Cromwell's death in 1658 caused the English Republic to collapse into feuding military and political factions. Milton, however, stubbornly clung to the beliefs that had originally inspired him to write for the Commonwealth. In 1659, he published ''

Milton's '' magnum opus'', the

Milton's '' magnum opus'', the

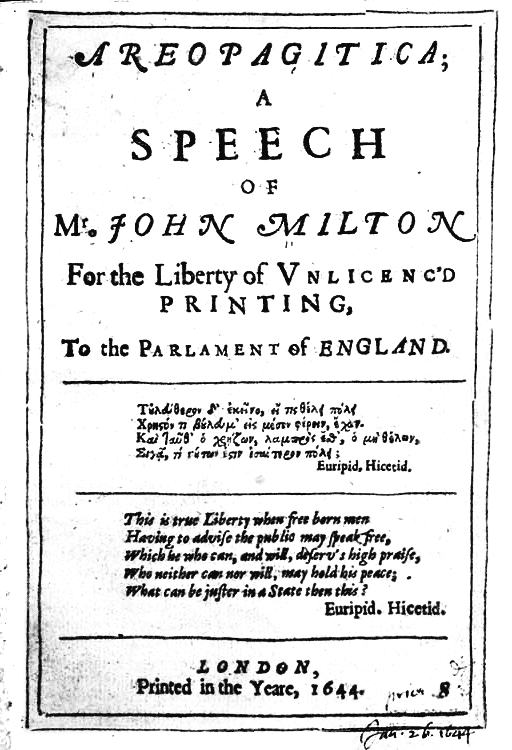

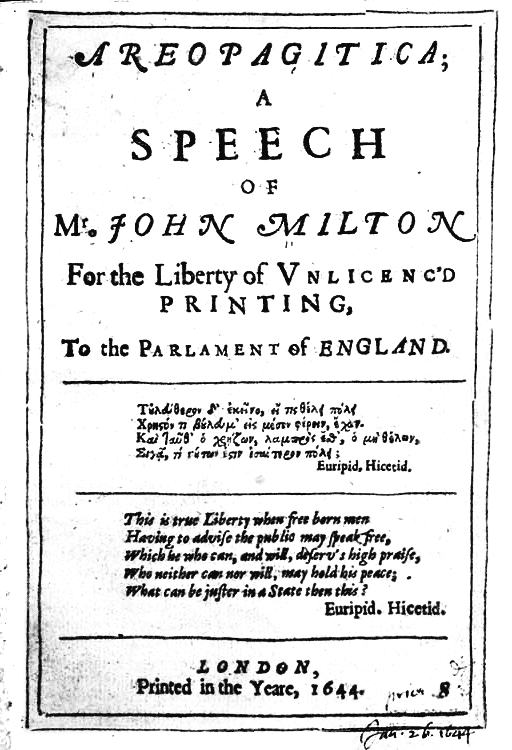

''Areopagitica'' was written in response to the Licensing Order, in November 1644.

Milton's political thought may be best categorized according to respective periods in his life and times. The years 1641–42 were dedicated to church politics and the struggle against episcopacy. After his divorce writings, ''Areopagitica'', and a gap, he wrote in 1649–54 in the aftermath of the execution of Charles I, and in polemic justification of the regicide and the existing Parliamentarian regime. Then in 1659–60 he foresaw the Restoration, and wrote to head it off.

Milton's own beliefs were in some cases unpopular, particularly his commitment to

''Areopagitica'' was written in response to the Licensing Order, in November 1644.

Milton's political thought may be best categorized according to respective periods in his life and times. The years 1641–42 were dedicated to church politics and the struggle against episcopacy. After his divorce writings, ''Areopagitica'', and a gap, he wrote in 1649–54 in the aftermath of the execution of Charles I, and in polemic justification of the regicide and the existing Parliamentarian regime. Then in 1659–60 he foresaw the Restoration, and wrote to head it off.

Milton's own beliefs were in some cases unpopular, particularly his commitment to

William Blake considered Milton the major English poet. Blake placed Edmund Spenser as Milton's precursor, and saw himself as Milton's poetical son. In his '' Milton: A Poem in Two Books'', Blake uses Milton as a character.

William Blake considered Milton the major English poet. Blake placed Edmund Spenser as Milton's precursor, and saw himself as Milton's poetical son. In his '' Milton: A Poem in Two Books'', Blake uses Milton as a character.

Milton's use of blank verse, in addition to his stylistic innovations (such as grandiloquence of voice and vision, peculiar diction and phraseology) influenced later poets. At the time, poetic blank verse was considered distinct from its use in verse drama, and ''

Milton's use of blank verse, in addition to his stylistic innovations (such as grandiloquence of voice and vision, peculiar diction and phraseology) influenced later poets. At the time, poetic blank verse was considered distinct from its use in verse drama, and ''

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral or w ...

and intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator o ...

. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The first version, published in 1667, consists of ten books with over ten thousand lines of verse. A second edition followed in 16 ...

'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and political upheaval. It addressed the fall of man, including the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan

Satan,, ; grc, ὁ σατανᾶς or , ; ar, شيطانالخَنَّاس , also known as the Devil, and sometimes also called Lucifer in Christianity, is an entity in the Abrahamic religions that seduces humans into sin or falsehoo ...

and God's expulsion of them from the Garden of Eden. ''Paradise Lost'' is widely considered one of the greatest works of literature ever written, and it elevated Milton's widely-held reputation as one of history's greatest poets. He also served as a civil servant for the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execu ...

under its Council of State and later under Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

.

Writing in English, Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

, and Italian, Milton achieved global fame and recognition during his lifetime; his celebrated ''Areopagitica

''Areopagitica; A speech of Mr. John Milton for the Liberty of Unlicenc'd Printing, to the Parlament of England'' is a 1644 prose polemic by the English poet, scholar, and polemical author John Milton opposing licensing and censorship. ''Areop ...

'' (1644), written in condemnation of pre-publication censorship, is among history's most influential and impassioned defences of freedom of speech and freedom of the press. His desire for freedom extended beyond his philosophy and was reflected in his style, which included his introduction of new words (coined from Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

and Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

) to the English language

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England. It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the ...

. He was the first modern writer to employ unrhymed verse outside of the theatre or translations.

Milton is described as the "greatest English author" by biographer William Hayley, and he remains generally regarded "as one of the preeminent writers in the English language", though critical reception has oscillated in the centuries since his death often on account of his republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. ...

. Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

praised ''Paradise Lost'' as "a poem which...with respect to design may claim the first place, and with respect to performance, the second, among the productions of the human mind", though he (a Tory) described Milton's politics as those of an "acrimonious and surly republican". Milton was revered by poets such as William Blake, William Wordsworth, and Thomas Hardy.

Phases of Milton's life parallel the major historical and political divisions in Stuart Britain at the time. In his early years, Milton studied at Christ's College at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, one of the world's most prestigious universities, and then travelled, wrote poetry mostly for private circulation, and launched a career as pamphleteer

Pamphleteer is a historical term for someone who creates or distributes pamphlets, unbound (and therefore inexpensive) booklets intended for wide circulation.

Context

Pamphlets were used to broadcast the writer's opinions: to articulate a poli ...

and publicist under Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

's increasingly autocratic rule and Britain's breakdown into constitutional confusion and ultimately civil war. While once considered dangerously radical and heretical, Milton contributed to a seismic shift in accepted public opinions during his life that ultimately elevated him to public office in England. The Restoration of 1660 and his loss of vision later deprived Milton much of his public platform, but he used the period to develop many of his major works.

Milton's views developed from extensive reading, travel, and experience that began with his days as a student at Cambridge in the 1620s and continued through the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

, which started in 1642 and continued through 1651. By the time of his death in 1674, Milton was impoverished and on the margins of English intellectual life but famous throughout Europe and unrepentant for political choices that placed him at odds with governing authorities.

Early life and education

John Milton was born in Bread Street, London, on 9 December 1608, the son of composer John Milton and his wife Sarah Jeffrey. The senior John Milton (1562–1647) moved to London around 1583 after being disinherited by his devout

John Milton was born in Bread Street, London, on 9 December 1608, the son of composer John Milton and his wife Sarah Jeffrey. The senior John Milton (1562–1647) moved to London around 1583 after being disinherited by his devout Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

father Richard "the Ranger" Milton for embracing Protestantism

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

. In London, the senior John Milton married Sarah Jeffrey (1572–1637) and found lasting financial success as a scrivener

A scrivener (or scribe) was a person who could read and write or who wrote letters to court and legal documents. Scriveners were people who made their living by writing or copying written material. This usually indicated secretarial and ad ...

. He lived in and worked from a house on Bread Street, where the Mermaid Tavern

The Mermaid Tavern was a tavern on Cheapside in London during the Elizabethan era, located east of St. Paul's Cathedral on the corner of Friday Street and Bread Street. It was the site of the so-called "Fraternity of Sireniacal Gentlemen", a dri ...

was located in Cheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, which forms part of the A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St. Martin's Le Grand with Poultry. Near its eastern end at Bank junction, whe ...

. The elder Milton was noted for his skill as a musical composer, and this talent left his son with a lifelong appreciation for music and friendships with musicians such as Henry Lawes

Henry Lawes (1596 – 1662) was the leading English songwriter of the mid-17th century. He was elder brother of fellow composer William Lawes.

Life

Henry Lawes (baptised 5 January 1596 – 21 October 1662),Ian Spink, "Lawes, Henry," ''Grove Musi ...

.

The prosperity of Milton's father allowed his eldest son to obtain a private tutor, Thomas Young, a Scottish Presbyterian with a MA from the University of St. Andrews. Young's influence also served as the poet's introduction to religious radicalism. After Young's tutorship, Milton attended St Paul's School in London, where he began the study of Latin and Greek; the classical languages left an imprint on both his poetry and prose in English (he also wrote in Latin and Italian).

Milton's first datable compositions are two psalms written at age 15 at Long Bennington

Long Bennington is a linear village and civil parish in South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England, just off the A1 road, north of Grantham and south of Newark-on-Trent. It had a population of 2,100 in 2014 and 2,018 at the 2011 Census. ...

. One contemporary source is '' Brief Lives'' of John Aubrey, an uneven compilation including first-hand reports. In the work, Aubrey quotes Christopher, Milton's younger brother: "When he was young, he studied very hard and sat up very late, commonly till twelve or one o'clock at night". Aubrey adds, "His complexion exceeding faire—he was so faire that they called him the Lady of Christ's College."Dick 1962 pp. 270–275.

In 1625, Milton gained entry to Christ's College at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, where he graduated with a BA in 1629, ranking fourth of 24 honours graduates that year in the University of Cambridge. Then preparing to become an Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

priest, Milton then pursued his Master of Arts degree at Cambridge, which he received on 3 July 1632.

Milton may have been rusticated (suspended) in his first year at Cambridge for quarrelling with his tutor, Bishop William Chappell. He was certainly at home in London in the Lent Term 1626; there he wrote ''Elegia Prima'', his first Latin elegy, to Charles Diodati, a friend from St Paul's. Based on remarks of John Aubrey, Chappell "whipt" Milton. This story is now disputed, though certainly Milton disliked Chappell. Historian Christopher Hill notes that Milton was apparently rusticated, and that the differences between Chappell and Milton may have been either religious or personal. It is also possible that, like Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, Theology, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosophy, natural philosopher"), widely ...

four decades later, Milton was sent home from Cambridge because of the plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

, which impacted Cambridge significantly in 1625.

At Cambridge, Milton was on good terms with Edward King; he later dedicated "Lycidas

"Lycidas" () is a poem by John Milton, written in 1637 as a pastoral elegy. It first appeared in a 1638 collection of elegies, ''Justa Edouardo King Naufrago'', dedicated to the memory of Edward King, a friend of Milton at Cambridge who dro ...

" to him. Milton also befriended Anglo-American dissident and theologian Roger Williams. Milton tutored Williams in Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

in exchange for lessons in Dutch. Despite developing a reputation for poetic skill and general erudition, Milton suffered from alienation among his peers during his time at Cambridge. Having once watched his fellow students attempting comedy upon the college stage, he later observed, "they thought themselves gallant men, and I thought them fools".

Milton also was disdainful of the university curriculum, which consisted of stilted formal debates conducted in Latin on abstruse topics. His own corpus is not devoid of humour, notably his sixth prolusion and his epitaphs on the death of Thomas Hobson. While at Cambridge, he wrote a number of his well-known shorter English poems, including "On the Morning of Christ's Nativity", "Epitaph on the admirable Dramaticke Poet, W. Shakespeare" (his first poem to appear in print), ''L'Allegro

''L'Allegro'' is a pastoral poem by John Milton published in his 1645 ''Poems''. ''L'Allegro'' (which means "the happy man" in Italian) has from its first appearance been paired with the contrasting pastoral poem, ''Il Penseroso'' ("the mela ...

'', and '' Il Penseroso''.

Study, poetry, and travel

Upon receiving his M.A. in 1632, Milton retired toHammersmith

Hammersmith is a district of West London, England, southwest of Charing Cross. It is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, and identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London ...

, his father's new home since the previous year. He also lived at Horton, Berkshire, from 1635 and undertook six years of self-directed private study. Hill argues that this was not retreat into a rural idyll; Hammersmith was then a "suburban village" falling into the orbit of London, and even Horton was becoming deforested and suffered from the plague. He read both ancient and modern works of theology, philosophy, history, politics, literature, and science in preparation for a prospective poetical career. Milton's intellectual development can be charted via entries in his commonplace book (like a scrapbook), now in the British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom and is one of the largest libraries in the world. It is estimated to contain between 170 and 200 million items from many countries. As a legal deposit library, the Briti ...

. As a result of such intensive study, Milton is considered to be among the most learned of all English poets. In addition to his years of private study, Milton had command of Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French, Spanish, and Italian from his school and undergraduate days; he also added Old English to his linguistic repertoire in the 1650s while researching his ''History of Britain'', and probably acquired proficiency in Dutch soon after.

temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

* Temperance (group), Canadian dan ...

and chastity. He contributed his pastoral elegy ''Lycidas

"Lycidas" () is a poem by John Milton, written in 1637 as a pastoral elegy. It first appeared in a 1638 collection of elegies, ''Justa Edouardo King Naufrago'', dedicated to the memory of Edward King, a friend of Milton at Cambridge who dro ...

'' to a memorial collection for one of his fellow-students at Cambridge. Drafts of these poems are preserved in Milton's poetry notebook, known as the Trinity Manuscript because it is now kept at Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

, Cambridge.

In May 1638, accompanied by a manservant, Milton embarked upon a tour of France and Italy for 15 months that lasted until July or August 1639. His travels supplemented his study with new and direct experience of artistic and religious traditions, especially Roman Catholicism. He met famous theorists and intellectuals of the time, and was able to display his poetic skills. For specific details of what happened within Milton's "grand tour

The Grand Tour was the principally 17th- to early 19th-century custom of a traditional trip through Europe, with Italy as a key destination, undertaken by upper-class young European men of sufficient means and rank (typically accompanied by a tut ...

", there appears to be just one primary source

In the study of history as an academic discipline, a primary source (also called an original source) is an artifact, document, diary, manuscript, autobiography, recording, or any other source of information that was created at the time under ...

: Milton's own ''Defensio Secunda

''Defension Secunda'' was a 1654 political tract by John Milton, a sequel to his ''Defensio pro Populo Anglicano''. It is a defence of the Parliamentary regime, by then controlled by Oliver Cromwell; and also defense of his own reputation against ...

''. There are other records, including some letters and some references in his other prose tracts, but the bulk of the information about the tour comes from a work that, according to Barbara Lewalski, "was not intended as autobiography but as rhetoric, designed to emphasise his sterling reputation with the learned of Europe."

He first went to Calais and then on to Paris, riding horseback, with a letter from diplomat Henry Wotton to ambassador John Scudamore. Through Scudamore, Milton met Hugo Grotius, a Dutch law philosopher, playwright, and poet. Milton left France soon after this meeting. He travelled south from Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative ...

to Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, and then to Livorno and Pisa. He reached Florence in July 1638. While there, Milton enjoyed many of the sites and structures of the city. His candour of manner and erudite neo-Latin poetry earned him friends in Florentine intellectual circles, and he met the astronomer Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

who was under house arrest at Arcetri

Arcetri is a location in Florence, Italy, positioned among the hills south of the city centre.

__TOC__

Landmarks

A number of historic buildings are situated there, including the house of the famous scientist Galileo Galilei (called ''Villa Il G ...

, as well as others. Milton probably visited the Florentine Academy and the Accademia della Crusca

The Accademia della Crusca (; "Academy of the Bran"), generally abbreviated as La Crusca, is a Florence-based society of scholars of Italian linguistics and philology. It is one of the most important research institutions of the Italian langu ...

along with smaller academies in the area, including the Apatisti and the Svogliati.

He left Florence in September to continue to Rome. With the connections from Florence, Milton was able to have easy access to Rome's intellectual society. His poetic abilities impressed those like Giovanni Salzilli, who praised Milton within an epigram. In late October, Milton attended a dinner given by the English College, Rome, despite his dislike for the Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

, meeting English Catholics who were also guests—theologian Henry Holden and the poet Patrick Cary Patrick may refer to:

*Patrick (given name), list of people and fictional characters with this name

*Patrick (surname), list of people with this name

People

*Saint Patrick (c. 385–c. 461), Christian saint

*Gilla Pátraic (died 1084), Patrick or ...

. He also attended musical events, including oratorios, operas, and melodramas. Milton left for Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

toward the end of November, where he stayed only for a month because of the Spanish control. During that time, he was introduced to Giovanni Battista Manso

Giovanni Battista Manso (1570- 28 December 1645) was an Italian aristocrat, scholar, and patron of the arts and artists.

Biography

Giambattista Manso was a wealthy nobleman and a prominent patron of the arts and letters in Naples during the late ...

, patron to both Torquato Tasso and to Giambattista Marino

Giovanni Battista was a common Italian given name (see Battista for those with the surname) in the 16th-18th centuries. It refers to " John the Baptist" in English, the French equivalent is "Jean-Baptiste". Common nicknames include Giambattista, G ...

.

Originally, Milton wanted to leave Naples in order to travel to Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and then on to Greece, but he returned to England during the summer of 1639 because of what he claimed in ''Defensio Secunda'' were "sad tidings of civil war in England." Matters became more complicated when Milton received word that his childhood friend Diodati had died. Milton in fact stayed another seven months on the continent, and spent time at Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

with Diodati's uncle after he returned to Rome. In ''Defensio Secunda'', Milton proclaimed that he was warned against a return to Rome because of his frankness about religion, but he stayed in the city for two months and was able to experience Carnival and meet Lukas Holste

Lucas Holstenius, born Lukas Holste, sometimes called Holstein (1596 – 2 February 1661), was a German Catholic humanist, geographer, historian, and librarian.

Life

Born at Hamburg in 1596, he studied at the gymnasium of Hamburg, and late ...

, a Vatican librarian who guided Milton through its collection. He was introduced to Cardinal Francesco Barberini who invited Milton to an opera hosted by the Cardinal. Around March, Milton travelled once again to Florence, staying there for two months, attending further meetings of the academies, and spending time with friends. After leaving Florence, he travelled through Lucca, Bologna, and Ferrara before coming to Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

. In Venice, Milton was exposed to a model of Republicanism, later important in his political writings, but he soon found another model when he travelled to Geneva. From Switzerland, Milton travelled to Paris and then to Calais before finally arriving back in England in either July or August 1639.

Civil war, prose tracts, and marriage

On returning to England where the Bishops' Wars presaged further armed conflict, Milton began to write prose tracts against episcopacy, in the service of the

On returning to England where the Bishops' Wars presaged further armed conflict, Milton began to write prose tracts against episcopacy, in the service of the Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

and Parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

cause. Milton's first foray into polemics was ''Of Reformation touching Church Discipline in England'' (1641), followed by ''Of Prelatical Episcopacy'', the two defences of Smectymnuus (a group of Presbyterian divines named from their initials; the "TY" belonged to Milton's old tutor Thomas Young), and '' The Reason of Church-Government Urged against Prelaty''. He vigorously attacked the High-church party of the Church of England and their leader William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

, with frequent passages of real eloquence lighting up the rough controversial style of the period, and deploying a wide knowledge of church history.

He was supported by his father's investments, but Milton became a private schoolmaster at this time, educating his nephews and other children of the well-to-do. This experience and discussions with educational reformer Samuel Hartlib led him to write his short tract ''Of Education

The tractate ''Of Education'' was published in 1644, first appearing anonymously as a single eight-page quarto sheet (Ainsworth 6). Presented as a letter written in response to a request from the Puritan educational reformer Samuel Hartlib, it r ...

'' in 1644, urging a reform of the national universities.

In June 1642, Milton paid a visit to the manor house at Forest Hill, Oxfordshire

Forest Hill is a village in Forest Hill with Shotover civil parish in Oxfordshire, about east of Oxford. The village which is about above sea level is on the northeastern brow of a ridge of hills. The highest point of the ridge is Red Hill ...

, and, aged 34, married the 17-year-old Mary Powell. The marriage got off to a poor start as Mary did not adapt to Milton's austere lifestyle or get along with his nephews. Milton found her intellectually unsatisfying and disliked the royalist views she had absorbed from her family. It is also speculated that she refused to consummate the marriage. Mary soon returned home to her parents and did not come back until 1645, partly because of the outbreak of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

.

In the meantime, her desertion prompted Milton to publish a series of pamphlets over the next three years arguing for the legality and morality of divorce beyond grounds of adultery. (Anna Beer

Anna Beer is a British author and lecturer, primarily known for her work as a biographer.

Her particular interests as a biographer are "the relationship between literature, politics and history," /sup> (which was the basis for her life of John ...

, one of Milton's most recent biographers , points to a lack of evidence and the dangers of cynicism in urging that it was not necessarily the case that the private life so animated the public polemicising.) In 1643, Milton had a brush with the authorities over these writings, in parallel with Hezekiah Woodward

Hezekiah Woodward (1590–1675) was an English nonconformist minister and educator, who was involved in the pamphlet wars of the 1640s. He was a Comenian in educational theory, and an associate of Samuel Hartlib. He was one of those articulating th ...

, who had more trouble. It was the hostile response accorded the divorce tracts that spurred Milton to write '' Areopagitica; A speech of Mr. John Milton for the Liberty of Unlicenc'd Printing, to the Parlament of England'', his celebrated attack on pre-printing censorship. In ''Areopagitica'', Milton aligns himself with the parliamentary cause, and he also begins to synthesize the ideal of neo-Roman liberty with that of Christian liberty. Milton also courted another woman during this time; we know nothing of her except that her name was Davis and she turned him down. However, it was enough to induce Mary Powell into returning to him which she did unexpectedly by begging him to take her back. She bore him two daughters in quick succession following their reconciliation.

Secretary for Foreign Tongues

With the Parliamentary victory in the Civil War, Milton used his pen in defence of the republican principles represented by the Commonwealth. '' The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates'' (1649) defended the right of the people to hold their rulers to account, and implicitly sanctioned the regicide; Milton's political reputation got him appointed Secretary for Foreign Tongues by the Council of State in March 1649. His main job description was to compose the English Republic's foreign correspondence inLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

and other languages, but he also was called upon to produce propaganda for the regime and to serve as a censor.

In October 1649, he published '' Eikonoklastes'', an explicit defence of the regicide, in response to the '' Eikon Basilike'', a phenomenal best-seller popularly attributed to Charles I that portrayed the King as an innocent Christian

In October 1649, he published '' Eikonoklastes'', an explicit defence of the regicide, in response to the '' Eikon Basilike'', a phenomenal best-seller popularly attributed to Charles I that portrayed the King as an innocent Christian martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

. A month later the exiled Charles II and his party published the defence of monarchy ''Defensio Regia pro Carolo Primo'', written by leading humanist Claudius Salmasius. By January of the following year, Milton was ordered to write a defence of the English people by the Council of State. Milton worked more slowly than usual, given the European audience and the English Republic's desire to establish diplomatic and cultural legitimacy, as he drew on the learning marshalled by his years of study to compose a riposte.

On 24 February 1652, Milton published his Latin defence of the English people ''Defensio pro Populo Anglicano

''Defensio pro Populo Anglicano'' is a Latin polemic by John Milton, published in 1651. The full title in English is ''John Milton an Englishman His Defence of the People of England.'' It was a piece of propaganda, and made political argument ...

'', also known as the ''First Defence''. Milton's pure Latin prose and evident learning exemplified in the ''First Defence'' quickly made him a European reputation, and the work ran to numerous editions. He addressed his ''Sonnet 16'' to 'The Lord Generall Cromwell in May 1652' beginning "Cromwell, our chief of men...", although it was not published until 1654.

In 1654, Milton completed the second defence of the English nation ''Defensio secunda'' in response to an anonymous Royalist tract ''"Regii Sanguinis Clamor ad Coelum Adversus Parricidas Anglicanos"'' he Cry of the Royal Blood to Heaven Against the English Parricides

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

a work that made many personal attacks on Milton. The second defence praised Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

, now Lord Protector, while exhorting him to remain true to the principles of the Revolution. Alexander Morus, to whom Milton wrongly attributed the ''Clamor'' (in fact by Peter du Moulin), published an attack on Milton, in response to which Milton published the autobiographical ''Defensio pro se'' in 1655. Milton held the appointment of Secretary for Foreign Tongues to the Commonwealth Council of State until 1660, although after he had become totally blind, most of the work was done by his deputies, Georg Rudolph Wecklein

Georg may refer to:

* ''Georg'' (film), 1997

*Georg (musical), Estonian musical

* Georg (given name)

* Georg (surname) George is a surname of Irish, English, Welsh, South Indian Christian, Middle Eastern Christian (usually Lebanese), French, or ...

, then Philip Meadows, and from 1657 by the poet Andrew Marvell.

By 1652, Milton had become totally blind; the cause of his blindness is debated but bilateral retinal detachment

Retinal detachment is a disorder of the eye in which the retina peels away from its underlying layer of support tissue. Initial detachment may be localized, but without rapid treatment the entire retina may detach, leading to vision loss and blin ...

or glaucoma

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases that result in damage to the optic nerve (or retina) and cause vision loss. The most common type is open-angle (wide angle, chronic simple) glaucoma, in which the drainage angle for aqueous humor, fluid withi ...

are most likely. His blindness forced him to dictate his verse and prose to amanuenses who copied them out for him; one of these was Andrew Marvell. One of his best-known sonnets, ''When I Consider How My Light is Spent

"When I Consider How My Light is Spent" (Also known as "On His Blindness") is one of the best known of the sonnets of John Milton (1608–1674). The last three lines are particularly well known; they conclude with "They also serve who only stand a ...

'', titled by a later editor, John Newton, "''On His Blindness''", is presumed to date from this period.

The Restoration

Cromwell's death in 1658 caused the English Republic to collapse into feuding military and political factions. Milton, however, stubbornly clung to the beliefs that had originally inspired him to write for the Commonwealth. In 1659, he published ''

Cromwell's death in 1658 caused the English Republic to collapse into feuding military and political factions. Milton, however, stubbornly clung to the beliefs that had originally inspired him to write for the Commonwealth. In 1659, he published ''A Treatise of Civil Power

A, or a, is the first letter and the first vowel of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''a'' (pronounced ), plural ''aes ...

'', attacking the concept of a state-dominated church (the position known as Erastianism), as well as ''Considerations touching the likeliest means to remove hirelings'', denouncing corrupt practises in church governance. As the Republic disintegrated, Milton wrote several proposals to retain a non-monarchical government against the wishes of parliament, soldiers, and the people.

* ''A Letter to a Friend, Concerning the Ruptures of the Commonwealth'', written in October 1659, was a response to General Lambert's recent dissolution of the Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

"R ...

.

* ''Proposals of certain expedients for the preventing of a civil war now feared'', written in November 1659.

* '' The Ready and Easy Way to Establishing a Free Commonwealth'', in two editions, responded to General Monck's march towards London to restore the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septe ...

(which led to the restoration of the monarchy). The work is an impassioned, bitter, and futile jeremiad

A jeremiad is a long literary work, usually in prose, but sometimes in verse, in which the author bitterly laments the state of society and its morals in a serious tone of sustained invective, and always contains a prophecy of society's immine ...

damning the English people for backsliding from the cause of liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

and advocating the establishment of an authoritarian rule by an oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate ...

set up by unelected parliament.

Upon the Restoration in May 1660, Milton, fearing for his life, went into hiding, while a warrant was issued for his arrest and his writings were burnt. He re-emerged after a general pardon was issued, but was nevertheless arrested and briefly imprisoned before influential friends intervened, such as Marvell, now an MP. Milton married for a third and final time on 24 February 1663, marrying Elizabeth (Betty) Minshull, aged 24, a native of Wistaston

Wistaston is a civil parish and village in the unitary authority of Cheshire East and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, in North West England. It is approximately west of Crewe town centre and east of Nantwich town centre. It has a ...

, Cheshire. He spent the remaining decade of his life living quietly in London, only retiring to a cottage during the Great Plague of London— Milton's Cottage in Chalfont St. Giles

Chalfont St Giles is a village and civil parish in southeast Buckinghamshire, England. It is in a group of villages called The Chalfonts, which also includes Chalfont St Peter and Little Chalfont.

It lies on the edge of the Chiltern Hills, we ...

, his only extant home.

During this period, Milton published several minor prose works, such as the grammar textbook ''Art of Logic'' and a ''History of Britain''. His only explicitly political tracts were the 1672 ''Of True Religion'', arguing for toleration

Toleration is the allowing, permitting, or acceptance of an action, idea, object, or person which one dislikes or disagrees with. Political scientist Andrew R. Murphy explains that "We can improve our understanding by defining "toleration" as ...

(except for Catholics), and a translation of a Polish tract advocating an elective monarchy. Both these works were referred to in the Exclusion debate, the attempt to exclude the heir presumptive from the throne of England— James, Duke of York—because he was Roman Catholic. That debate preoccupied politics in the 1670s and 1680s and precipitated the formation of the Whig party and the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

.

Death

Milton died on 8 November 1674 and was buried in the church of St Giles-without-Cripplegate, Fore Street, London.Walter Thornbury, 'Cripplegate', in Old and New London: Volume 2 (London, 1878), pp. 229-245. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol2/pp229-245 ccessed 7 July 2020 However, sources differ as to whether the cause of death was consumption orgout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intens ...

. According to an early biographer, his funeral was attended by "his learned and great Friends in London, not without a friendly concourse of the Vulgar." A monument was added in 1793, sculpted by John Bacon the Elder.

Family

Milton and his first wife Mary Powell (1625–1652) had four children: * Anne (born 29 July 1646) * Mary (born 25 October 1648) * John (16 March 1651 – June 1652) * Deborah (2 May 1652 – 10 August 1727) Mary Powell died on 5 May 1652 from complications following Deborah's birth. Milton's daughters survived to adulthood, but he always had a strained relationship with them. On 12 November 1656, Milton was married to Katherine Woodcock at St Margaret's, Westminster. She died on 3 February 1658, less than four months after giving birth to her daughter Katherine, who also died. Milton married for a third time on 24 February 1663 to Elizabeth Mynshull or Minshull (1638–1728), the niece of Thomas Mynshull, a wealthy apothecary and philanthropist inManchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The ...

. The marriage took place at St Mary Aldermary in the City of London. Despite a 31-year age gap, the marriage seemed happy, according to John Aubrey, and lasted more than 12 years until Milton's death. (A plaque on the wall of Mynshull's House in Manchester describes Elizabeth as Milton's "3rd and Best wife".) Samuel Johnson, however, claims that Mynshull was "a domestic companion and attendant" and that Milton's nephew Edward Phillips relates that Mynshull "oppressed his children in his lifetime, and cheated them at his death".

His nephews, Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

and John Phillips (sons of Milton's sister Anne), were educated by Milton and became writers themselves. John acted as a secretary, and Edward was Milton's first biographer.

Poetry

Milton's poetry was slow to see the light of day, at least under his name. His first published poem was "On Shakespeare" (1630), anonymously included in theSecond Folio

The Second Folio is the 1632 edition of the collected plays of William Shakespeare. It follows the First Folio of 1623. Much language was updated in the Second Folio and there are almost 1,700 changes.

The major partners in the First Folio ha ...

edition of William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's plays in 1632. An annotated copy of the First Folio has been suggested to contain marginal notes by Milton. Milton collected his work in '' 1645 Poems'' in the midst of the excitement attending the possibility of establishing a new English government. The anonymous edition of ''Comus'' was published in 1637, and the publication of ''Lycidas'' in 1638 in ''Justa Edouardo King Naufrago'' was signed J. M. Otherwise. The 1645 collection was the only poetry of his to see print until ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The first version, published in 1667, consists of ten books with over ten thousand lines of verse. A second edition followed in 16 ...

'' appeared in 1667.

''Paradise Lost''

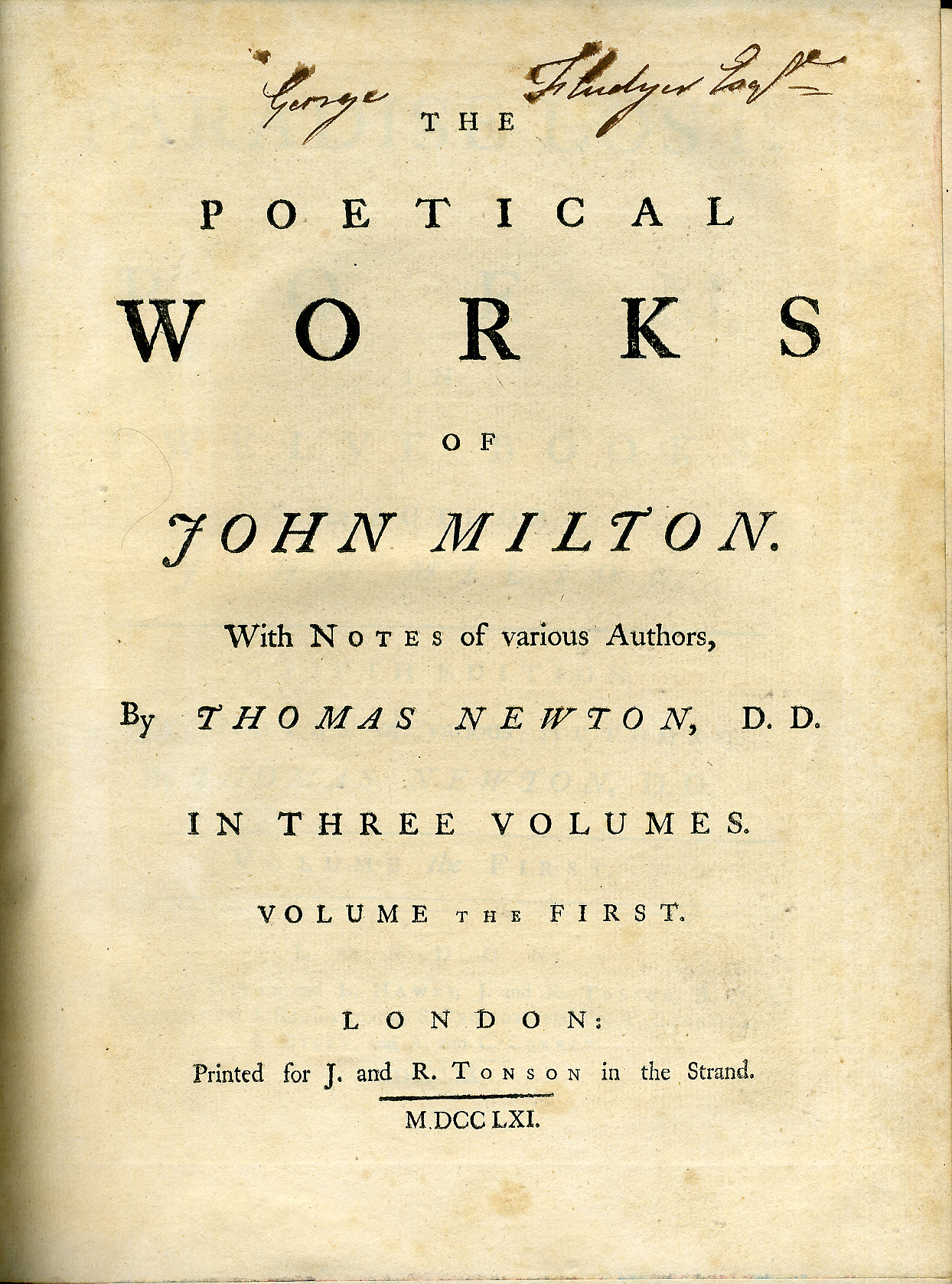

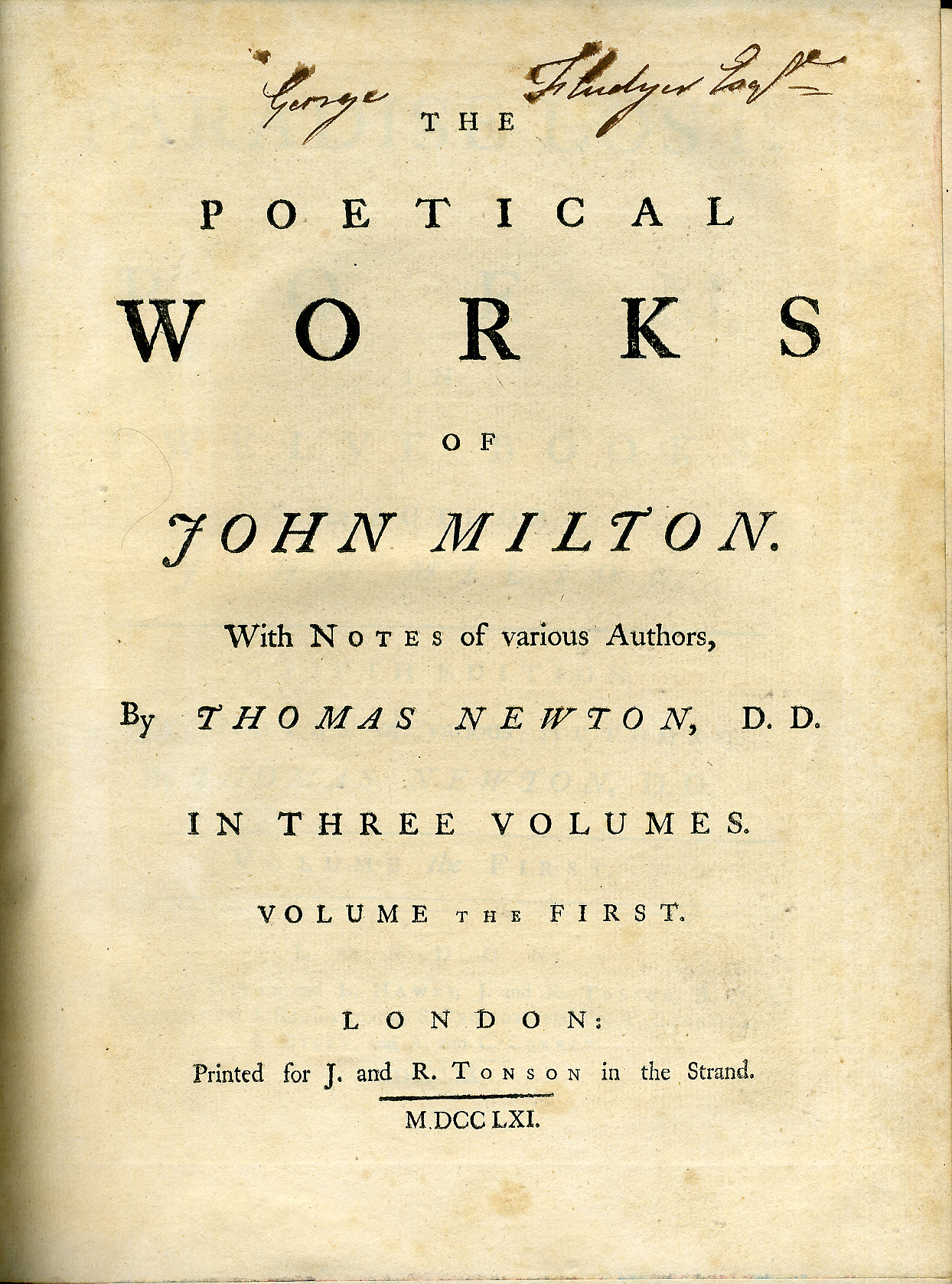

Milton's '' magnum opus'', the

Milton's '' magnum opus'', the blank-verse

Blank verse is poetry written with regular metrical but unrhymed lines, almost always in iambic pentameter. It has been described as "probably the most common and influential form that English poetry has taken since the 16th century", and Pa ...

epic poem ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The first version, published in 1667, consists of ten books with over ten thousand lines of verse. A second edition followed in 16 ...

'', was composed by the blind and impoverished Milton from 1658 to 1664 (first edition), with small but significant revisions published in 1674 (second edition). As a blind poet, Milton dictated his verse to a series of aides in his employ. It has been argued that the poem reflects his personal despair at the failure of the Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

yet affirms an ultimate optimism in human potential. Some literary critics have argued that Milton encoded many references to his unyielding support for the " Good Old Cause".

On 27 April 1667, Milton sold the publication rights for ''Paradise Lost'' to publisher Samuel Simmons

Samuel Simmons (1640–1687) was an English printer, best known as the first publisher of several works by John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise ...

for £5 (equivalent to approximately £770 in 2015 purchasing power), with a further £5 to be paid if and when each print run sold out of between 1,300 and 1,500 copies. The first run was a quarto

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produc ...

edition priced at three shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence ...

s per copy (about £23 in 2015 purchasing power equivalent), published in August 1667, and it sold out in eighteen months.

Milton followed up the publication ''Paradise Lost'' with its sequel '' Paradise Regained'', which was published alongside the tragedy '' Samson Agonistes'' in 1671. Both of these works also reflect Milton's post-Restoration political situation. Just before his death in 1674, Milton supervised a second edition of ''Paradise Lost'', accompanied by an explanation of "why the poem rhymes not", and prefatory verses by Andrew Marvell. In 1673, Milton republished his ''1645 Poems'', as well as a collection of his letters and the Latin prolusions from his Cambridge days.

Views

An unfinished religious manifesto, '' De doctrina christiana'', probably written by Milton, lays out many of his heterodox theological views, and was not discovered and published until 1823. Milton's key beliefs were idiosyncratic, not those of an identifiable group or faction, and often they go well beyond the orthodoxy of the time. Their tone, however, stemmed from the Puritan emphasis on the centrality and inviolability of conscience. He was his own man, but he was anticipated by Henry Robinson in ''Areopagitica''.Philosophy

While Milton's beliefs are generally considered to be consistent with Protestant Christianity, Stephen Fallon argues that by the late 1650s, Milton may have at least toyed with the idea ofmonism

Monism attributes oneness or singleness (Greek: μόνος) to a concept e.g., existence. Various kinds of monism can be distinguished:

* Priority monism states that all existing things go back to a source that is distinct from them; e.g., i ...

or animist materialism, the notion that a single material substance which is "animate, self-active, and free" composes everything in the universe: from stones and trees and bodies to minds, souls, angels, and God. Fallon claims that Milton devised this position to avoid the mind-body dualism of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

and Descartes as well as the mechanistic

The mechanical philosophy is a form of natural philosophy which compares the universe to a large-scale mechanism (i.e. a machine). The mechanical philosophy is associated with the scientific revolution of early modern Europe. One of the first expo ...

determinism of Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

. According to Fallon, Milton's monism is most notably reflected in ''Paradise Lost'' when he has angels eat (5.433–439) and apparently engage in sexual intercourse (8.622–629) and the ''De Doctrina'', where he denies the dual natures of man and argues for a theory of Creation ''ex Deo''.

Political thought

Milton was a "passionately individual Christian Humanist poet." He appears on the pages of seventeenth century English Puritanism, an age characterized as "the world turned upside down." He was a Puritan and yet was unwilling to surrender conscience to party positions on public policy. Thus, Milton's political thought, driven by competing convictions, a Reformed faith and a Humanist spirit, led to enigmatic outcomes.Milton’s apparently contradictory stance on the vital problems of his age, arose from religious contestations, to the questions of the divine rights of kings. In both the cases, he seems in control, taking stock of the situation arising from the polarization of the English society on religious and political lines. He fought with the Puritans against the Cavaliers i.e. the King’s party, and helped win the day. But the very same constitutional and republican polity, when tried to curtail freedom of speech, Milton, given his humanistic zeal, wrote ''Areopagitica'' . . . 'sic''ref name=":1">

''Areopagitica'' was written in response to the Licensing Order, in November 1644.

Milton's political thought may be best categorized according to respective periods in his life and times. The years 1641–42 were dedicated to church politics and the struggle against episcopacy. After his divorce writings, ''Areopagitica'', and a gap, he wrote in 1649–54 in the aftermath of the execution of Charles I, and in polemic justification of the regicide and the existing Parliamentarian regime. Then in 1659–60 he foresaw the Restoration, and wrote to head it off.

Milton's own beliefs were in some cases unpopular, particularly his commitment to

''Areopagitica'' was written in response to the Licensing Order, in November 1644.

Milton's political thought may be best categorized according to respective periods in his life and times. The years 1641–42 were dedicated to church politics and the struggle against episcopacy. After his divorce writings, ''Areopagitica'', and a gap, he wrote in 1649–54 in the aftermath of the execution of Charles I, and in polemic justification of the regicide and the existing Parliamentarian regime. Then in 1659–60 he foresaw the Restoration, and wrote to head it off.

Milton's own beliefs were in some cases unpopular, particularly his commitment to republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. ...

. In coming centuries, Milton would be claimed as an early apostle of liberalism. According to James Tully:

A friend and ally in the pamphlet wars was Marchamont Nedham. Austin Woolrych

Austin Herbert Woolrych (18 May 191814 September 2004) was an English historian, a specialist in the period of the English Civil War.

Early life and education

Austin Woolrych was born in Marylebone, London, the son of Stanley Herbert Cunliffe ...

considers that although they were quite close, there is "little real affinity, beyond a broad republicanism", between their approaches. Blair Worden remarks that both Milton and Nedham, with others such as Andrew Marvell and James Harrington, would have taken their problem with the Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

"R ...

to be not the republic itself, but the fact that it was not a proper republic. Woolrych speaks of "the gulf between Milton's vision of the Commonwealth's future and the reality". In the early version of his '' History of Britain'', begun in 1649, Milton was already writing off the members of the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septe ...

as incorrigible.

He praised Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

as the Protectorate was set up; though subsequently he had major reservations. When Cromwell seemed to be backsliding as a revolutionary, after a couple of years in power, Milton moved closer to the position of Sir Henry Vane, to whom he wrote a sonnet in 1652. The group of disaffected republicans included, besides Vane, John Bradshaw, John Hutchinson, Edmund Ludlow

Edmund Ludlow (c. 1617–1692) was an English parliamentarian, best known for his involvement in the execution of Charles I, and for his ''Memoirs'', which were published posthumously in a rewritten form and which have become a major source ...

, Henry Marten, Robert Overton, Edward Sexby

Colonel Edward Sexby (or Saxby; 1616 – 13 January 1658) was an English Puritan soldier and Leveller in the army of Oliver Cromwell. Later he turned against Cromwell and plotted his assassination.

Biography

Sexby was born in Suffolk in 161 ...

and John Streater

John Streater (died 1687) was an English soldier, political writer and printer. An opponent of Oliver Cromwell, Streater was a "key republican critic of the regime" He was a leading example of the "commonwealthmen", one division among the English r ...

; but not Marvell, who remained with Cromwell's party. Milton had already commended Overton, along with Edmund Whalley

Edward Whalley (c. 1607 – c. 1675) was an English military leader during the English Civil War and was one of the regicides who signed the death warrant of King Charles I of England.

Early career

The exact dates of his birth and death are u ...

and Bulstrode Whitelocke, in ''Defensio Secunda

''Defension Secunda'' was a 1654 political tract by John Milton, a sequel to his ''Defensio pro Populo Anglicano''. It is a defence of the Parliamentary regime, by then controlled by Oliver Cromwell; and also defense of his own reputation against ...

''. Nigel Smith writes that

As Richard Cromwell

Richard Cromwell (4 October 162612 July 1712) was an English statesman who was the second and last Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland and son of the first Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell.

On his father's deat ...

fell from power, he envisaged a step towards a freer republic or "free commonwealth", writing in the hope of this outcome in early 1660. Milton had argued for an awkward position, in the '' Ready and Easy Way'', because he wanted to invoke the Good Old Cause and gain the support of the republicans, but without offering a democratic solution of any kind. His proposal, backed by reference (amongst other reasons) to the oligarchical

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, r ...

Dutch and Venetian constitutions, was for a council with perpetual membership. This attitude cut right across the grain of popular opinion of the time, which swung decisively behind the restoration of the Stuart monarchy that took place later in the year. Milton, an associate of and advocate on behalf of the regicides, was silenced on political matters as Charles II returned.

Theology

Milton was neither a clergyman nor a theologian; however, theology, and particularly English Calvinism, formed the palette on which John Milton created his greatest thoughts. John Milton wrestled with the great doctrines of the Church amidst the theological crosswinds of his age. The great poet was undoubtedly Reformed (though his grandfather, Richard "the Ranger" Milton had been Roman Catholic). However, Milton's Calvinism had to find expression in a broad-spirited Humanism. Like manyRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

artists before him, Milton attempted to integrate Christian theology with classical modes. In his early poems, the poet narrator expresses a tension between vice and virtue, the latter invariably related to Protestantism. In ''Comus'', Milton may make ironic use of the Caroline

Caroline may refer to:

People

*Caroline (given name), a feminine given name

* J. C. Caroline (born 1933), American college and National Football League player

* Jordan Caroline (born 1996), American (men's) basketball player

Places Antarctica

* ...

court masque by elevating notions of purity and virtue over the conventions of court revelry and superstition. In his later poems, Milton's theological concerns become more explicit.

His use of biblical citation was wide-ranging; Harris Fletcher, standing at the beginning of the intensification of the study of the use of scripture in Milton's work (poetry and prose, in all languages Milton mastered), notes that typically Milton clipped and adapted biblical quotations to suit the purpose, giving precise chapter and verse only in texts for a more specialized readership. As for the plenitude of Milton's quotations from scripture, Fletcher comments, "For this work, I have in all actually collated about twenty-five hundred of the five to ten thousand direct Biblical quotations which appear therein". Milton's customary English Bible was the Authorized King James. When citing and writing in other languages, he usually employed the Latin translation by Immanuel Tremellius, though "he was equipped to read the Bible in Latin, in Greek, and in Hebrew, including the Targumim or Aramaic paraphrases of the Old Testament, and the Syriac version of the New, together with the available commentaries of those several versions".

Milton embraced many heterodox Christian theological views. He has been accused of rejecting the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

, believing instead that the Son was subordinate to the Father, a position known as Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

; and his sympathy or curiosity was probably engaged by Socinianism: in August 1650 he licensed for publication by William Dugard

William Dugard, or Du Gard (9 January 1606 – 3 December 1662), was an English schoolmaster and printer. During the English Interregnum, he printed many important documents and propaganda, first in support of Charles I and later of Oliver Cromwe ...

the '' Racovian Catechism'', based on a non-trinitarian creed. Milton's alleged Arianism, like much of his theology, is still subject of debate and controversy. Rufus Wilmot Griswold

Rufus Wilmot Griswold (February 13, 1815 – August 27, 1857) was an American anthologist, editor, poet, and critic. Born in Vermont, Griswold left home when he was 15 years old. He worked as a journalist, editor, and critic in Philadelphia, New Y ...

argued that "In none of his great works is there a passage from which it can be inferred that he was an Arian; and in the very last of his writings he declares that "the doctrine of the Trinity is a plain doctrine in Scripture." In ''Areopagitica,'' Milton classified Arians and Socinians as "errorists" and "schismatics" alongside Arminians and Anabaptists. A source has interpreted him as broadly Protestant, if not always easy to locate in a more precise religious category. In 2019, John Rogers stated, "Heretics both, John Milton and Isaac Newton were, as most scholars now agree, Arians."

In his 1641 treatise, '' Of Reformation'', Milton expressed his dislike for Catholicism and episcopacy, presenting Rome as a modern Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

, and bishops as Egyptian taskmasters. These analogies conform to Milton's puritanical preference for Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

imagery. He knew at least four commentaries on ''Genesis'': those of John Calvin, Paulus Fagius, David Pareus

David Pareus (30 December 1548 – 15 June 1622) was a German Reformed Protestant theologian and reformer.

Life

He was born at Frankenstein in Schlesien on 30 December 1548. At some point, he hellenized his original surname, ''Wängler'' (mean ...

and Andreus Rivetus.

Through the Interregnum, Milton often presents England, rescued from the trappings of a worldly monarchy, as an elect

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

nation akin to the Old Testament Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, and shows its leader, Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

, as a latter-day Moses. These views were bound up in Protestant views of the Millennium

A millennium (plural millennia or millenniums) is a period of one thousand years, sometimes called a kiloannus, kiloannum (ka), or kiloyear (ky). Normally, the word is used specifically for periods of a thousand years that begin at the starting ...

, which some sects, such as the Fifth Monarchists predicted would arrive in England. Milton, however, would later criticise the "worldly" millenarian views of these and others, and expressed orthodox ideas on the prophecy of the Four Empires.

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660 began a new phase in Milton's work. In ''Paradise Lost'', '' Paradise Regained'' and '' Samson Agonistes'', Milton mourns the end of the godly Commonwealth. The Garden of Eden may allegorically reflect Milton's view of England's recent Fall from Grace

To fall from grace is an idiom referring to a loss of status, respect, or prestige.

Fall from grace may also refer to:

* Fall of man, in Christianity, the transition of the first man and woman from a state of innocent obedience to God to a state ...

, while Samson's blindness and captivity—mirroring Milton's own lost sight—may be a metaphor for England's blind acceptance of Charles II as king.

Illustrated by ''Paradise Lost'' is mortalism

Christian mortalism is the Christian belief that the human soul is not naturally immortal and may include the belief that the soul is “sleeping” after death until the Resurrection of the Dead and the Last Judgment, a time known as the int ...

, the belief that the soul lies dormant after the body dies.

Despite the Restoration of the monarchy, Milton did not lose his personal faith; ''Samson'' shows how the loss of national salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its ...

did not necessarily preclude the salvation of the individual, while ''Paradise Regained'' expresses Milton's continuing belief in the promise of Christian salvation through Jesus Christ.

Though he maintained his personal faith in spite of the defeats suffered by his cause, the '' Dictionary of National Biography'' recounted how he had been alienated from the Church of England by Archbishop William Laud, and then moved similarly from the Dissenters by their denunciation of religious tolerance in England.

Writing of the enigmatic and often conflicting views of Milton in the Puritan age, David Daiches wrote convincingly,"Christian and Humanist, Protestant, patriot and heir of the golden ages of Greece and Rome, he faced what appeared to him to be the birth-pangs of a new and regenerate England with high excitement and idealistic optimism.”A fair theological summary may be: that John Milton was a Puritan, though his tendency to press further for liberty of conscience, sometimes out of conviction and often out of mere intellectual curiosity, made the great man, at least, a vital if not uncomfortable ally in the broader Puritan movement.

Religious toleration

Milton called in the ''Areopagitica

''Areopagitica; A speech of Mr. John Milton for the Liberty of Unlicenc'd Printing, to the Parlament of England'' is a 1644 prose polemic by the English poet, scholar, and polemical author John Milton opposing licensing and censorship. ''Areop ...

'' for "the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties" to the conflicting Protestant denominations. According to American historian William Hunter, "Milton argued for disestablishment

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular s ...

as the only effective way of achieving broad toleration

Toleration is the allowing, permitting, or acceptance of an action, idea, object, or person which one dislikes or disagrees with. Political scientist Andrew R. Murphy explains that "We can improve our understanding by defining "toleration" as ...

. Rather than force a man's conscience, government should recognise the persuasive force of the gospel."

Divorce

Milton wrote ''The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce'' in 1643, at the beginning of the English Civil War. In August of that year, he presented his thoughts to the Westminster Assembly of Divines, which had been created by theLong Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septe ...

to bring greater reform to the Church of England. The Assembly convened on 1 July against the will of King Charles I.

Milton's thinking on divorce caused him considerable trouble with the authorities. An orthodox Presbyterian view of the time was that Milton's views on divorce constituted a one-man heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

:

Even here, though, his originality is qualified: Thomas Gataker had already identified "mutual solace" as a principal goal in marriage. Milton abandoned his campaign to legitimise divorce after 1645, but he expressed support for polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is marr ...

in the '' De Doctrina Christiana'', the theological treatise that provides the clearest evidence for his views.