John McEwen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

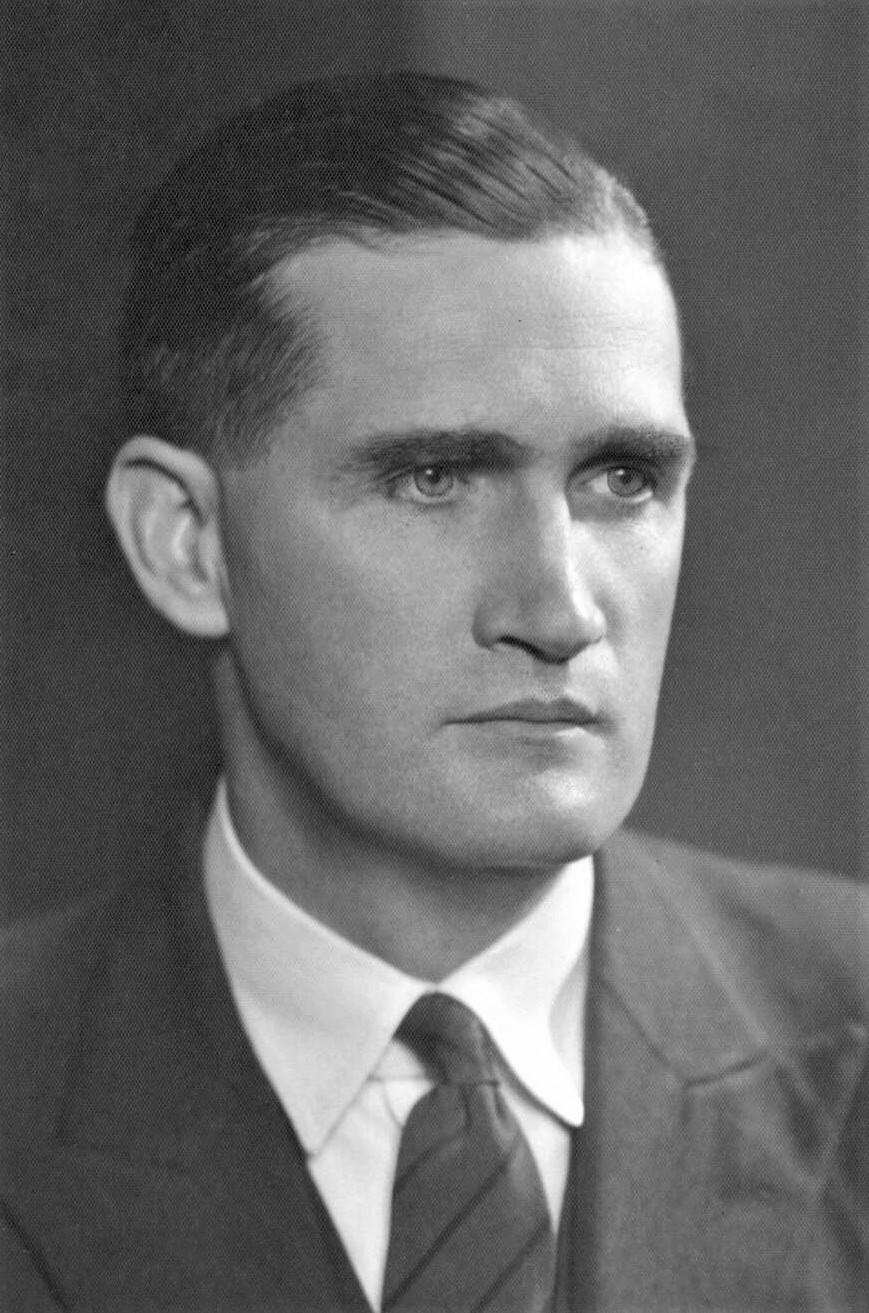

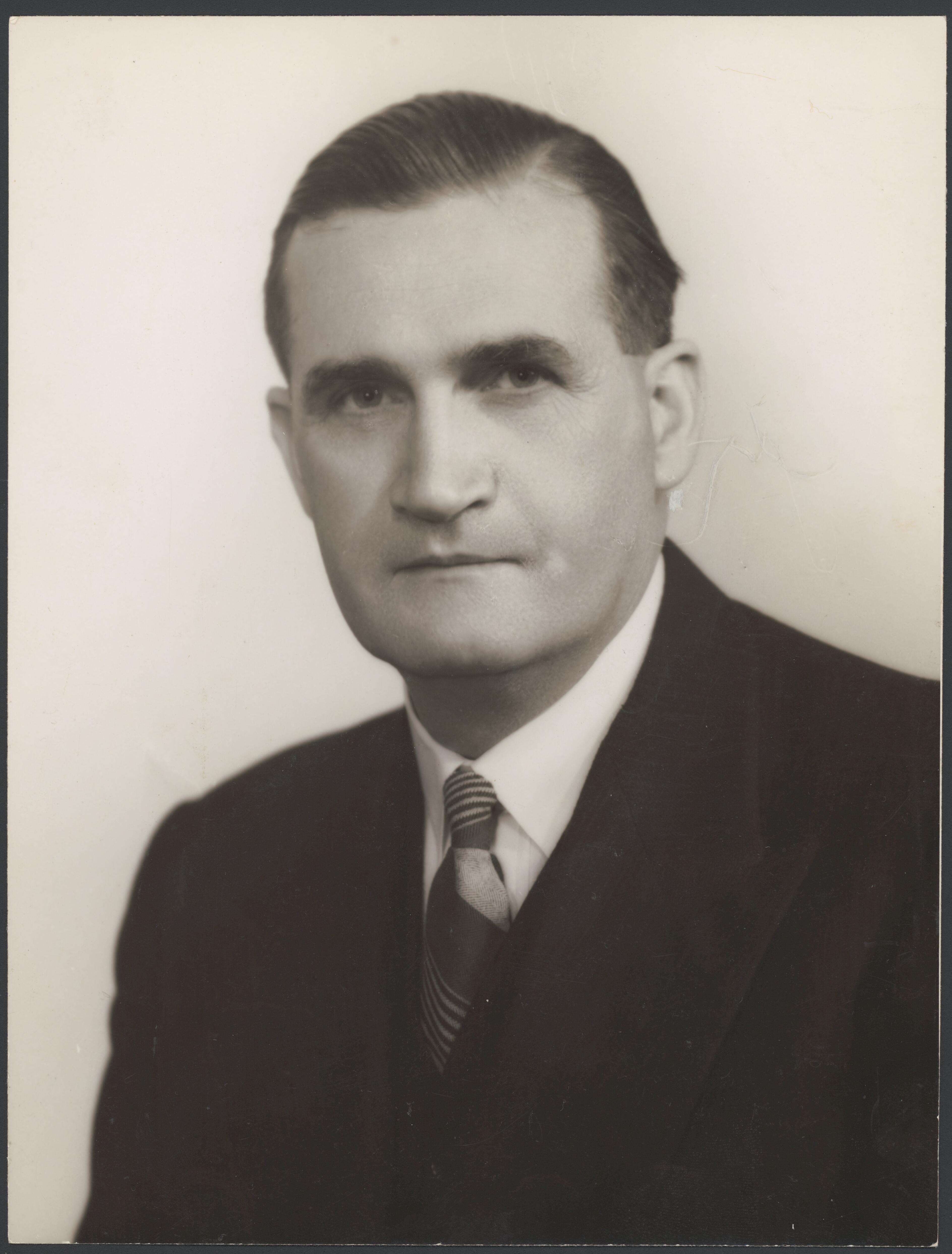

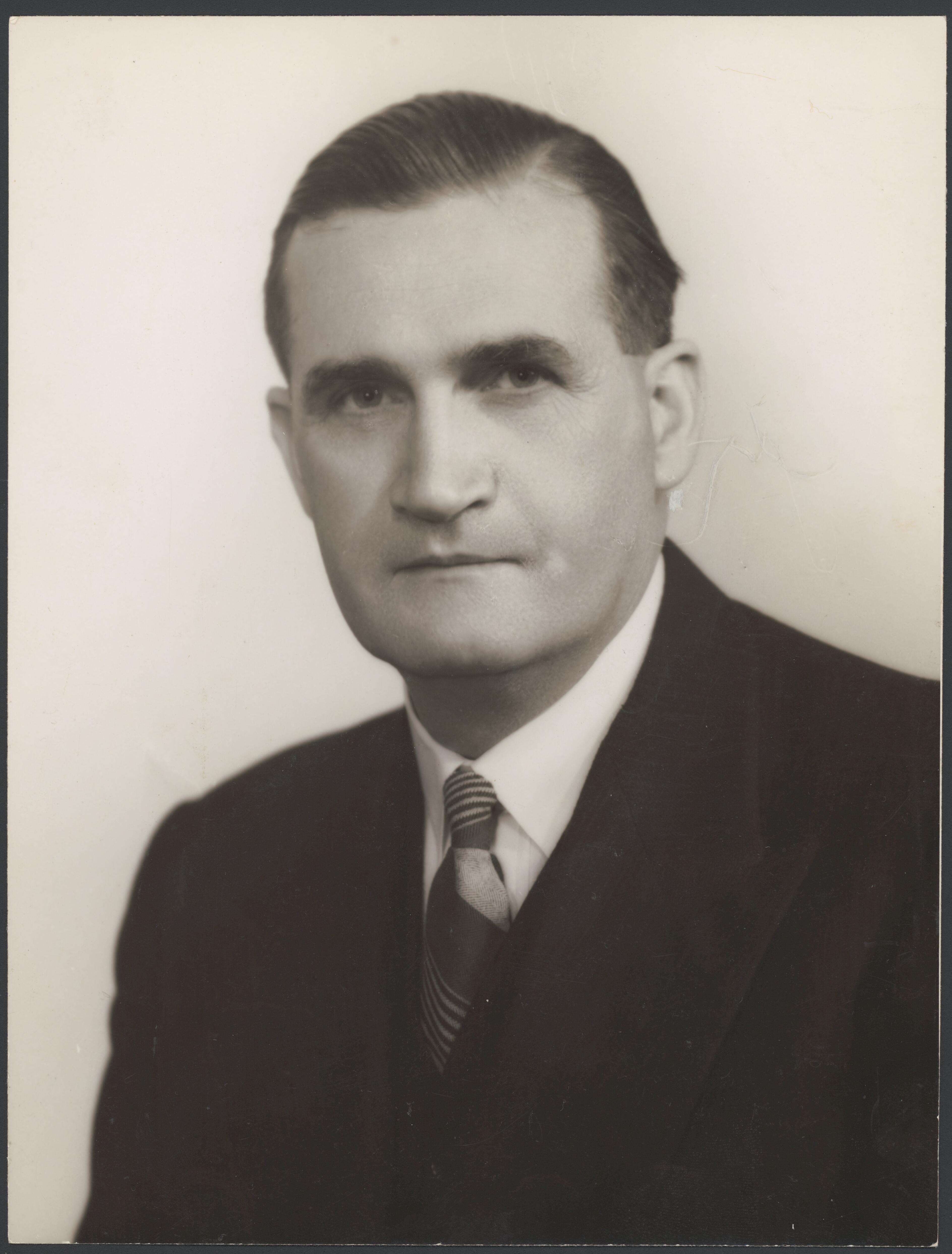

Sir John McEwen, (29 March 1900 – 20 November 1980) was an Australian politician who served as the 18th

In 1958, following Fadden's retirement, McEwen was elected unopposed as leader of the Country Party. This made him the ''de facto''

In 1958, following Fadden's retirement, McEwen was elected unopposed as leader of the Country Party. This made him the ''de facto''

Harold Holt disappeared while swimming at Portsea, Victoria, on 17 December 1967, and was officially presumed dead two days later. The

Harold Holt disappeared while swimming at Portsea, Victoria, on 17 December 1967, and was officially presumed dead two days later. The  Another key factor in McEwen's antipathy towards McMahon was hinted at soon after the crisis by the veteran political journalist Alan Reid. According to Reid, McEwen was aware that McMahon was habitually breaching Cabinet confidentiality and regularly leaking information to favoured journalists and lobbyists, including

Another key factor in McEwen's antipathy towards McMahon was hinted at soon after the crisis by the veteran political journalist Alan Reid. According to Reid, McEwen was aware that McMahon was habitually breaching Cabinet confidentiality and regularly leaking information to favoured journalists and lobbyists, including

Gorton created the formal title

Gorton created the formal title

McEwen was awarded the

McEwen was awarded the

McEwen, Sir John (1900–1980)

, adb.online.anu.edu.au; accessed 10 June 2015.

Former Prime Minister Sir John McEwen's secret pain led to tragic end, says book by Julian Fitzgerald

'' Adelaide Advertiser'', 3 November 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2017. McEwen was cremated, and his estate was sworn for probate at $2,180,479. He was also receiving a small pension from the Department of Social Security at the time of his death.

John McEwen at the National Film and Sound Archive

* {{DEFAULTSORT:McEwen, John 1900 births 1980 deaths 1980 suicides 20th-century Australian politicians Australian farmers Australian Freemasons Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Australian Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Australian military personnel of World War I Australian ministers for Foreign Affairs Australian monarchists Australian people of English descent Australian people of Irish descent Australian people of Ulster-Scottish descent Australian politicians awarded knighthoods Australian politicians who committed suicide Deputy Prime Ministers of Australia Grand Cordons of the Order of the Rising Sun Leaders of the National Party of Australia Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Echuca Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Indi Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Murray Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Cabinet of Australia National Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia Prime Ministers of Australia Suicides by starvation Suicides in Victoria (Australia)

prime minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister heads the executive branch of the federal government of Australia and is also accountable to federal parliament under the princip ...

, holding office from 1967 to 1968 in a caretaker capacity after the disappearance of Harold Holt

On 17 December 1967, Harold Holt, the Prime Minister of Australia, disappeared while swimming in the sea near Portsea, Victoria. An enormous search operation was mounted in and around Cheviot Beach, but his body was never recovered. Holt was p ...

. He was the leader of the Country Party from 1958 to 1971.

McEwen was born in Chiltern, Victoria. He was orphaned at the age of seven and raised by his grandmother, initially in Wangaratta and then in Dandenong

Dandenong is a southeastern suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, about from the Melbourne CBD. It is the council seat of the City of Greater Dandenong local government area, with a recorded population of 30,127 at the . Situated mainl ...

. McEwen left school when he was 13 and joined the Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal land warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (CA), who ...

at the age of 18, but the war ended before his unit was shipped out. He was nonetheless eligible for a soldier settlement

Soldier settlement was the settlement of land throughout parts of Australia by returning discharged soldiers under soldier settlement schemes administered by state governments after World War I and World War II. The post-World War II settlem ...

scheme, and selected a property at Stanhope. He established a dairy farm, but later bought a larger property and farmed beef cattle.

After several previous unsuccessful candidacies, McEwen was elected to the House of Representatives at the 1934 federal election. He was first elevated to cabinet by Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 – 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the 10th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1932 until his death in 1939. He began his career in the Australian Labor Party (ALP), ...

in 1937. McEwen became deputy leader of the Country Party in 1940, under Arthur Fadden

Sir Arthur William Fadden, (13 April 189421 April 1973) was an Australian politician who served as the 13th prime minister of Australia from 29 August to 7 October 1941. He was the leader of the Country Party from 1940 to 1958 and also served ...

. He replaced Fadden as leader in 1958, and remained in the position until his retirement from politics in 1971. He served in parliament for 36 years in total, spending a record 25 years as a government minister.

The Liberal-Country Coalition returned to power in 1949, initially under Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

and then under Harold Holt

Harold Edward Holt (5 August 190817 December 1967) was an Australian politician who served as the 17th prime minister of Australia from 1966 until his presumed death in 1967. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party.

Holt was born in ...

. McEwen came to have a major influence on economic policy, particularly in the areas of agriculture, manufacturing, and trade. When Holt died in office in December 1967, he was commissioned as caretaker prime minister while the Liberal Party elected a new leader. He was 67 at the time, the oldest person to become prime minister and only the third from the Country Party. McEwen ceded power to John Gorton

Sir John Grey Gorton (9 September 1911 – 19 May 2002) was an Australian politician who served as the nineteenth Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1968 to 1971. He led the Liberal Party during that time, having previously been a l ...

after 23 days in office, and in recognition of his service was appointed deputy prime minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

, the first time that position had been formally created. He was Australia's third shortest serving prime minister, after Earle Page and Frank Forde. He remained as deputy prime minister until his retirement from politics in 1971.

Early life

Birth and family background

McEwen was born on 29 March 1900, at his parents' home in Chiltern, Victoria. He was the son of Amy Ellen (née Porter) and David James McEwen. His mother was born in Victoria, and had English and Irish ancestry. His father was of Ulster Scots origin, born in Mountnorris,County Armagh

County Armagh (, named after its county town, Armagh) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. Adjoined to the southern shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of an ...

(in present-day Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is #Descriptions, variously described as ...

). He worked as a chemist, and also served a term on the Chiltern Shire Council.Golding (1996), p. 37. The family surname was originally spelled "MacEwen

The Scottish surname MacEwen derives from the Old Gaelic ''Mac Eoghainn'', meaning 'the son of Eoghann'. The name is found today in both Scotland and Northern Ireland. Because it was widely used before its spelling was standardised, the modern n ...

", but was altered upon David McEwen's arrival in Australia in 1889.

Childhood

In his memoirs, McEwen recounted that he had almost no memories of his parents. His mother died of lung disease in March 1902, just before his second birthday; she had given birth to a daughter, Amy, a few months earlier. She was the second of his father's three wives, and McEwen had three half-siblings – Gladys, Evelyn, and George.Golding (1996), p. 36. After their mother's death, McEwen and his sister were raised by their father, living in the rooms behind his chemist's shop. He died frommeningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or ...

in September 1907, when his son was seven. John and Amy were sent to live with their widowed grandmother, Nellie Porter (née Cook), while their younger half-brother went to live with his mother in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a metro ...

.Golding (1996), p. 38. They had never lived with their older half-sisters, who had been sent to live in a children's home upon their mother's death in 1893.

McEwen's grandmother ran a boardinghouse in Wangaratta. He grew up in what he described as "pretty frugal circumstances", and in 1912 his grandmother moved the family to Dandenong

Dandenong is a southeastern suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, about from the Melbourne CBD. It is the council seat of the City of Greater Dandenong local government area, with a recorded population of 30,127 at the . Situated mainl ...

, on the outskirts of Melbourne. McEwen attended state schools in Wangaratta and Dandenong until the age of thirteen, when he began working for Rocke, Tompsitt & Co., a drug manufacturer in central Melbourne. He initially worked as a switchboard operator

In the early days of telephony, companies used manual telephone switchboards, and switchboard operators connected calls by inserting a pair of phone plugs into the appropriate jacks. They were gradually phased out and replaced by automated system ...

, for which he was paid 15 shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence ...

s per week. McEwen began attending night school in Prahran, and in 1915 passed an examination for the Commonwealth Public Service and began working as a junior clerk at the office of the Commonwealth Crown Solicitor

The Australian Government Solicitor (AGS) is an Australian public servant and a federal government agency of the same name which provides legal advice to the federal government and its agencies.

AGS was originally the Crown Solicitor's Office, ...

. His immediate superior there was Fred Whitlam

Harry Frederick Ernest "Fred" Whitlam (3 April 1884 – 8 December 1961) was Australia's Crown Solicitor from 1936 to 1949, and a pioneer of international human rights law in Australia. He was the father of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, and ...

, the father of another future prime minister, Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from 1972 to 1975. The longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1967 to 1977, he was notable for being the h ...

.Golding (1996), p. 40.

Soldier-settler

With World War I ongoing, McEwen resolved to enter the military when he turned 18. He joined theAustralian Army Cadets

The Australian Army Cadets (AAC) is the youth military program and organisation of the Australian Army, tasked with supporting participants to contribute to society, fostering interest in defence force careers, and developing support for the ...

and completed a Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the principal naval force of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (CN) Vice Admiral Mark Hammond AM, RAN. CN is also jointly responsible to the Minister o ...

course in radiotelegraphy, hoping to qualify for the newly opened Royal Military College, Duntroon

lit: Learning promotes strength

, established =

, type = Military college

, chancellor =

, head_label = Commandant

, head = Brigadier Ana Duncan

, principal =

, city = Campbell

, state ...

. He passed the entrance exam, but instead chose to enlist as a private in the Australian Imperial Force, in order to be posted overseas sooner. The war ended before his unit shipped out. Despite the briefness of his service, McEwen was eligible for the Victorian government's soldier settlement

Soldier settlement was the settlement of land throughout parts of Australia by returning discharged soldiers under soldier settlement schemes administered by state governments after World War I and World War II. The post-World War II settlem ...

scheme. He selected an lot at Stanhope, on land that previously been a sheep station. As with many other soldier-settlers, McEwen initially did not have the money or the expertise needed to run a farm. He spent several months working as a farm labourer and later did the same as a stevedore

A stevedore (), also called a longshoreman, a docker or a dockworker, is a waterfront manual laborer who is involved in loading and unloading ships, trucks, trains or airplanes.

After the shipping container revolution of the 1960s, the number ...

at the Port of Melbourne

The Port of Melbourne is the largest port for containerised and general cargo in Australia. It is located in Melbourne, Victoria, and covers an area at the mouth of the Yarra River, downstream of Bolte Bridge, which is at the head of Port Ph ...

, eventually saving enough money to return to Stanhope and establish his dairy farm.

McEwen's new property was virtually undeveloped, with only a single existing building (a small shack) and no fences, irrigation, or paddocks. He and the other soldier-settlers in the Stanhope district suffered a number of hardships in the early 1920s, including droughts, rabbit plagues, and low milk prices. Many of them were forced off their properties, allowing those who survived to expand their holdings relatively cheaply. In 1926, McEwen sold his property and bought a larger farm nearby, which he named ''Chilgala'' (a portmanteau of Chiltern and Tongala

Tongala is a town in the Goulburn Valley region of northern Victoria, Australia. The town is in the Shire of Campaspe local government area, between Kyabram and Echuca, north of the state capital, Melbourne. At the , Tongala had a population of ...

, the birthplaces of himself and his wife). He switched from dairy to beef cattle, and was able to expand his property by buying abandoned farms from the government. At its peak, ''Chilgala'' covered and carried 1,800 head of cattle. McEwen had a reputation as one of the best farmers in the district, and came to be seen by the other soldier-settlers as a spokesman and leader. He represented them in meetings with government officials, and was secretary of the local Water Users' League, which protected the interests of irrigators. In 1923, he co-founded the Stanhope Dairy Co-operative, and was elected as the company's inaugural chairman.

Political career

Early years

McEwen was active in farmer organisations and in the Country Party. In 1934 he was elected to the House of Representatives for the electorate ofEchuca

Echuca ( ) is a town on the banks of the Murray River and Campaspe River in Victoria, Australia. The border town of Moama is adjacent on the northern side of the Murray River in New South Wales. Echuca is the administrative centre and larges ...

. That seat was abolished in 1937, and McEwen followed most of his constituents into Indi

Indi may refer to:

*Mag-indi language

* Division of Indi, an electoral division in the Australian House of Representatives

*Indi, Karnataka, a town in the state of Karnataka, India

*Instrument Neutral Distributed Interface, a distributed control sy ...

. He changed seats again in 1949, when Murray

Murray may refer to:

Businesses

* Murray (bicycle company), an American manufacturer of low-cost bicycles

* Murrays, an Australian bus company

* Murray International Trust, a Scottish investment trust

* D. & W. Murray Limited, an Australian who ...

was carved out of the northwestern portion of Indi and McEwen transferred there. Between 1937 and 1941 he was successively Minister for the Interior

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of government w ...

, Minister for External Affairs and (simultaneously) Minister for Air and Minister for Civil Aviation. In 1940, when Archie Cameron resigned as Country Party leader, McEwen contested the leadership ballot against Sir Earle Page: the ballot was tied and Arthur Fadden

Sir Arthur William Fadden, (13 April 189421 April 1973) was an Australian politician who served as the 13th prime minister of Australia from 29 August to 7 October 1941. He was the leader of the Country Party from 1940 to 1958 and also served ...

was chosen as a compromise. McEwen became his deputy.

Menzies and Holt Governments

When the conservatives returned to office in 1949 underRobert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

after eight years in opposition, McEwen became Minister for Commerce and Agriculture, switching to Minister for Trade in 1956. Menzies nicknamed him "Black Jack", due to his dark eyebrows, grim nature, and occasional temper. In the Menzies Government, McEwen pursued what became known as "McEwenism" – a policy of high tariff protection for the manufacturing industry, so that industry would not challenge the continuing high tariffs on imported raw materials, which benefitted farmers but pushed up industry's costs. This policy was a part (some argue the foundation) of what became known as the "Australian settlement

The Australian settlement was a set of nation-building policies adopted in Australia at the beginning of the 20th century. The phrase was coined by journalist Paul Kelly in his 1992 book ''The End of Certainty''. Kelly identified five policy "p ...

" which promoted high wages, industrial development, government intervention in industry (Australian governments traditionally owned banks and insurance companies and the railways and through policies designed to assist particular industries) and decentralisation.

In 1958, following Fadden's retirement, McEwen was elected unopposed as leader of the Country Party. This made him the ''de facto''

In 1958, following Fadden's retirement, McEwen was elected unopposed as leader of the Country Party. This made him the ''de facto'' deputy prime minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

, and gave him a free choice of portfolio. Fadden had been Treasurer, but McEwen somewhat unexpectedly chose to continue on as trade minister. This allowed Harold Holt

Harold Edward Holt (5 August 190817 December 1967) was an Australian politician who served as the 17th prime minister of Australia from 1966 until his presumed death in 1967. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party.

Holt was born in ...

to become the first Liberal MP to serve as Treasurer; since then every Treasurer in a Coalition Government has been a Liberal. McEwen nonetheless had considerable influence in cabinet. He and his party favoured interventionist economic policies and were opposed to foreign ownership of industrial assets, which placed him frequently at odds with his Liberal colleagues. In 1962, a dispute between McEwen and Assistant Treasurer Les Bury ended with Bury being sacked from cabinet. His stature eventually grew to the point where he was considered a potential successor to Menzies as prime minister. An opinion poll in December 1963 showed that 19 percent of Coalition voters favoured McEwen as Menzies' successor, only two points behind the poll leader Holt. By December 1965, this number had risen to 27 percent, compared with Holt's 22 percent. McEwen's cause was championed by a number of media outlets, including '' The Sun'' and ''The Australian

''The Australian'', with its Saturday edition, ''The Weekend Australian'', is a broadsheet newspaper published by News Corp Australia since 14 July 1964.Bruns, Axel. "3.1. The active audience: Transforming journalism from gatekeeping to gatew ...

''. Nonetheless, he had few supporters within the Liberal Party, and it was generally held that he would have to become a Liberal if he were to lead the Coalition, which he was unwilling to do.

Holt replaced Menzies as prime minister in January 1966, with McEwen continuing on his previous position. His portfolio had been expanded after the 1963 election, with his department now called the Department of Trade and Industry. McEwen enjoyed a "sound working relationship" with Holt, but without the same rapport he had had with Menzies. However, he had a poor relationship with William McMahon

Sir William McMahon (23 February 190831 March 1988) was an Australian politician who served as the 20th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1971 to 1972 as leader of the Liberal Party. He was a government minister for over 21 years, ...

, Holt's replacement as Treasurer. They had philosophical differences over free trade and foreign investment, both of which McEwen opposed. McMahon was also suspected to be undermining McEwen through his connections in the media.

McEwen's most serious disagreement with Holt came in November 1967, when it was announced that Australia – which had converted to decimal currency

Decimalisation or decimalization (see spelling differences) is the conversion of a system of currency or of weights and measures to units related by powers of 10.

Most countries have decimalised their currencies, converting them from non-decimal ...

the previous year – would not follow the recent devaluation of the pound sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and ...

. This effectively marked Australia's withdrawal from the sterling area. McEwen issued a public statement criticising the decision, which he feared would damage primary industry. Holt considered this a breach of cabinet solidarity, and made preparations for the Liberal Party to govern in its own right in case the Country Party withdrew from the government. The situation was eventually resolved In Holt's favour.

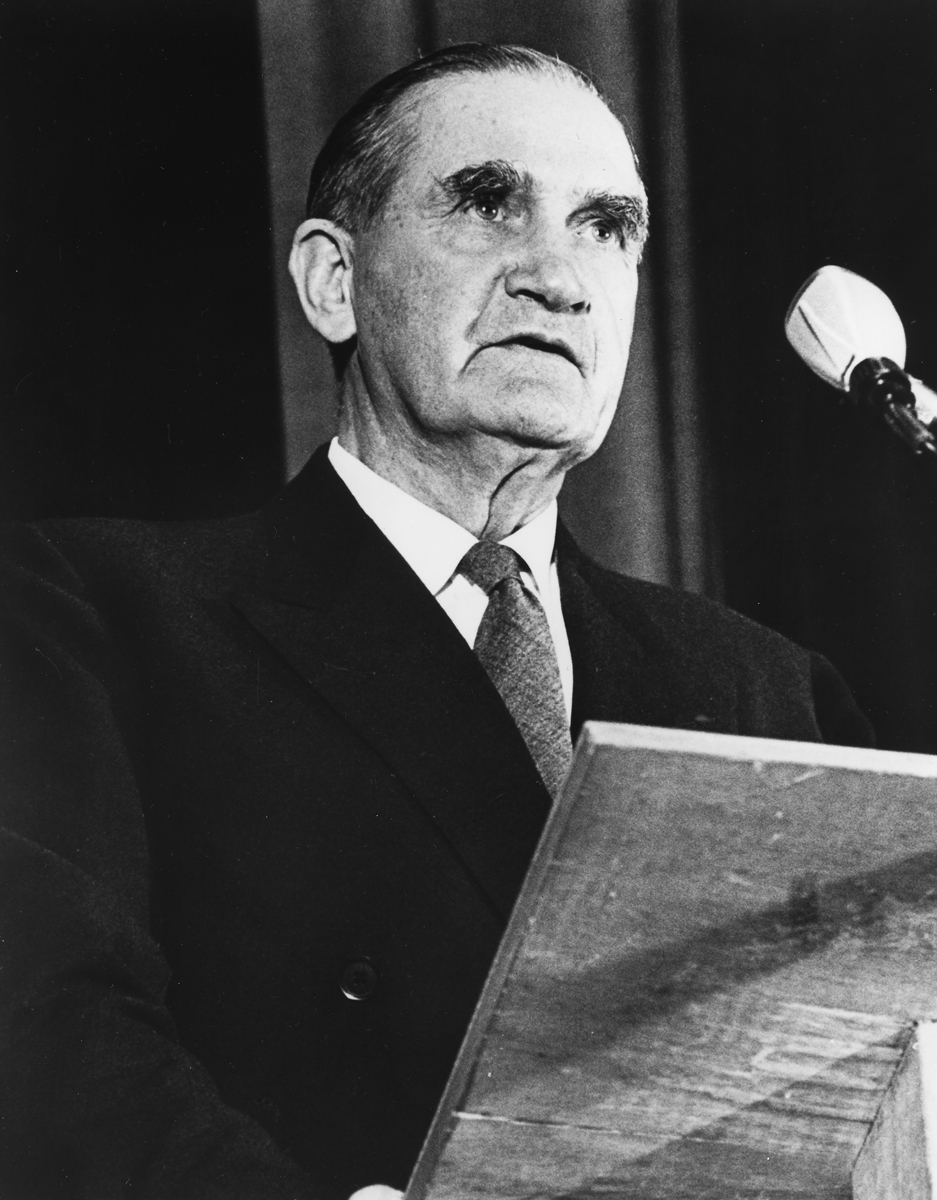

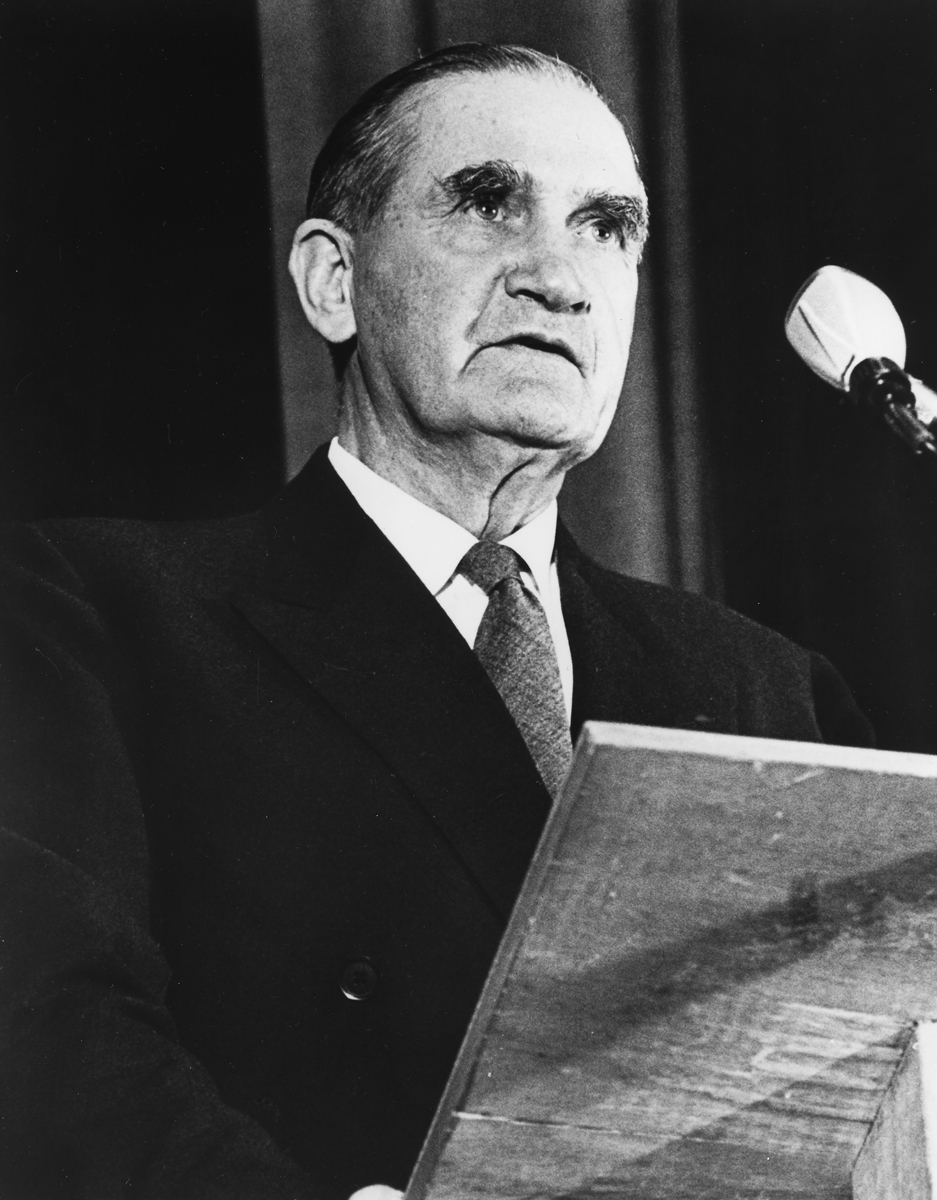

Prime Minister

Harold Holt disappeared while swimming at Portsea, Victoria, on 17 December 1967, and was officially presumed dead two days later. The

Harold Holt disappeared while swimming at Portsea, Victoria, on 17 December 1967, and was officially presumed dead two days later. The Governor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

, Lord Casey

Richard Gavin Gardiner Casey, Baron Casey, (29 August 1890 – 17 June 1976) was an Australian statesman who served as the 16th Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1965 to 1969. He was also a distinguished army officer, long-serving ...

, sent for McEwen and commissioned him as interim Prime Minister, on the understanding that his commission would continue only so long as it took for the Liberals to elect a new leader. McEwen contended that if Casey commissioned a Liberal as interim Prime Minister, it would give that person an undue advantage in the upcoming ballot for a full-time leader.

McEwen retained all of Holt's ministers, and had them sworn in as the McEwen Ministry. Approaching 68, McEwen was the oldest person ever to be appointed Prime Minister of Australia, although not the oldest to serve; Menzies left office one month and six days after his 71st birthday. McEwen had been encouraged to remain Prime Minister on a more permanent basis but to do so would have required him to defect to the Liberals, an option he had never contemplated.

It had long been presumed that McMahon, who was both Treasurer and deputy Liberal leader, would succeed Holt as Liberal leader and hence Prime Minister. However, McEwen sparked a leadership crisis when he announced that he and his Country Party colleagues would not serve under McMahon. McEwen is reported to have despised McMahon personally. More importantly, McEwen was bitterly opposed to McMahon on political grounds, because McMahon was allied with free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

advocates in the conservative parties and favoured sweeping tariff reforms, a position that was vehemently opposed by McEwen, his Country Party colleagues and their rural constituents.

Another key factor in McEwen's antipathy towards McMahon was hinted at soon after the crisis by the veteran political journalist Alan Reid. According to Reid, McEwen was aware that McMahon was habitually breaching Cabinet confidentiality and regularly leaking information to favoured journalists and lobbyists, including

Another key factor in McEwen's antipathy towards McMahon was hinted at soon after the crisis by the veteran political journalist Alan Reid. According to Reid, McEwen was aware that McMahon was habitually breaching Cabinet confidentiality and regularly leaking information to favoured journalists and lobbyists, including Maxwell Newton

Maxwell Newton (29 April 1929 – 23 July 1990) was an Australian media publisher. He was a founding editor of '' The Australian''. He was the owner of ''Daily Commercial News'' from 1969 to 1981, publisher of the '' Melbourne Observer'' from 197 ...

, who had been hired as a "consultant" by Japanese trade interests.

Even in the wake of their landslide victory in 1966, the Liberals were still four seats short of an outright majority. With only the Country Party as a realistic coalition partner, McEwen's opposition forced McMahon to withdraw from the leadership ballot. This opened the door for the successful campaign to promote the Minister for Education and Science, Senator John Gorton

Sir John Grey Gorton (9 September 1911 – 19 May 2002) was an Australian politician who served as the nineteenth Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1968 to 1971. He led the Liberal Party during that time, having previously been a l ...

, to the Prime Ministership with the support of a group led by Defence Minister

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in s ...

Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983, holding office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Fraser was raised on hi ...

. Gorton was elected as leader of the Liberal Party on 9 January 1968, and succeeded McEwen as Prime Minister the following day. It was the second time the Country Party had effectively vetoed its senior partner's choice for the leadership; in 1923 Earle Page had demanded that the Nationalist Party, one of the forerunners of the Liberals, remove Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

as leader before he would even consider coalition talks.

Later years

Gorton created the formal title

Gorton created the formal title Deputy Prime Minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

for McEwen, confirming his status as the second-ranking member of the government. Prior to then, the title had been used informally for whoever was recognised as the second-ranking member of the government – the leader of the Country Party when the Coalition was in government, and Labor's deputy leader when Labor was in government. Even before being formally named Deputy Prime Minister, McEwen had exercised an effective veto over government policy since 1966 by virtue of being the most senior member of the government, having been a member of the Coalition frontbench without interruption since 1937.

McEwen retired from politics in 1971. In his memoir, he recalls his career as being "long and very, very hard", and turned back to managing 1,800 head of cattle on his property in Goulburn Valley. In the same year, Clifton Pugh

Clifton Ernest Pugh AO, (17 December 1924 – 14 October 1990) was an Australian artist and three-time winner of Australia's Archibald Prize. One of Australia's most renowned and successful painters, Pugh was strongly influenced by German Expr ...

won the Archibald Prize

The Archibald Prize is an Australian portraiture art prize for painting, generally seen as the most prestigious portrait prize in Australia. It was first awarded in 1921 after the receipt of a bequest from J. F. Archibald, the editor ...

for a portrait of McEwen. While he had softened in his "unequivocal support for protection" by the time of his retirement he had given way to free-traders with regards to agriculture. However, he felt differently about manufacturing, as it was essential to National power:"My own view has always been that it would be ridiculous to think that Australia was safe in the long term unless we built up our population and built up our industries. So I have always wanted to make Australia a powerful industrialised country as well as a major agricultural and mining country. This basic attitude meant that I was bound to favour broadly protectionist policies aimed at developing our manufacturing sector."At the time of his resignation, he had served in parliament for 36 years and 5 months, including 34 years as either a minister (1937–1941 and 1949–1971) or opposition frontbencher (1941–1949). He was the last serving parliamentarian from

the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

era, and hence the last parliamentary survivor of the Lyons

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of t ...

government. By the time of his death, Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983, holding office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Fraser was raised on hi ...

's government was abandoning McEwenite trade policies.

Honours

McEwen was awarded the

McEwen was awarded the Companion of Honour

The Order of the Companions of Honour is an order of the Commonwealth realms. It was founded on 4 June 1917 by King George V as a reward for outstanding achievements. Founded on the same date as the Order of the British Empire, it is sometimes ...

(CH) in 1969. He was knighted in 1971 after his retirement from politics, becoming a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

(GCMG). The Japanese government conferred on him the Grand Cordon, Order of the Rising Sun in 1973.C.J. LloydMcEwen, Sir John (1900–1980)

, adb.online.anu.edu.au; accessed 10 June 2015.

Personal life and death

On 21 September 1921, he married Anne Mills McLeod, known as Annie; they had no children. In 1966, she was made a Dame Commander of theOrder of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

(DBE). After a long illness Dame Anne McEwen died on 10 February 1967.

At the time of becoming Prime Minister in December of that year, McEwen was a widower, being the first Australian Prime Minister unmarried during his term of office. (The next such case was Julia Gillard

Julia Eileen Gillard (born 29 September 1961) is an Australian former politician who served as the 27th prime minister of Australia from 2010 to 2013, holding office as leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP). She is the first and only ...

, Prime Minister 2010–13, who had a domestic partner although unwed.)

On 26 July 1968, McEwen married Mary Eileen Byrne, his personal secretary for 15 years, at Wesley Church, Melbourne

Wesley Church is a Uniting Church in the centre of Melbourne, in the State of Victoria, Australia.

Wesley Church was originally built as the central church of the Wesleyan movement in Victoria. It is named after John Wesley (1703–1791), the f ...

; he was aged 68, she was 46. In retirement he distanced himself from politics, undertook some consulting work, and travelled to Japan and South Africa. He had no children by any of his marriages.

McEwen suffered from severe dermatitis

Dermatitis is inflammation of the skin, typically characterized by itchiness, redness and a rash. In cases of short duration, there may be small blisters, while in long-term cases the skin may become thickened. The area of skin involved c ...

for most of his adult life. He recounted that "for literally months at a time, I would be walking about Parliament House with my feet bleeding and damaged." The pain became unbearable in later years, and he began refusing food in order to hasten his death; he died of self-imposed starvation on 20 November 1980, aged 80.'' Adelaide Advertiser'', 3 November 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

See also

* McEwen MinistryReferences

Further reading

* * *External links

* * *John McEwen at the National Film and Sound Archive

* {{DEFAULTSORT:McEwen, John 1900 births 1980 deaths 1980 suicides 20th-century Australian politicians Australian farmers Australian Freemasons Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Australian Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Australian military personnel of World War I Australian ministers for Foreign Affairs Australian monarchists Australian people of English descent Australian people of Irish descent Australian people of Ulster-Scottish descent Australian politicians awarded knighthoods Australian politicians who committed suicide Deputy Prime Ministers of Australia Grand Cordons of the Order of the Rising Sun Leaders of the National Party of Australia Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Echuca Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Indi Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Murray Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Cabinet of Australia National Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia Prime Ministers of Australia Suicides by starvation Suicides in Victoria (Australia)