John Marrant on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Marrant (June 15, 1755 – April 15, 1791) was an American Methodist preacher and missionary and one of the first black preachers in North America. Born free in New York City, he moved as a child with his family to

Marrant was born free in

Marrant was born free in  His mother moved the family to

His mother moved the family to

At the age of 13, about 1768, Marrant and a friend went to hear

At the age of 13, about 1768, Marrant and a friend went to hear  Marrant lived with the Cherokee for two years during which he had visited with other tribes of the area, including Catawa, Housaw, and

Marrant lived with the Cherokee for two years during which he had visited with other tribes of the area, including Catawa, Housaw, and

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

. His father died when he was young, and he and his mother also lived in Florida and Georgia. After escaping to the Cherokee, with whom he lived for two years, he allied with the British during the American Revolutionary War and resettled afterward in London. There he became involved with the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion

The Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion is a small society of evangelical churches, founded in 1783 by Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, as a result of the Evangelical Revival. For many years it was strongly associated with the Calvinist ...

and ordained as a preacher.

Marrant was supported to travel in 1785 as a preacher and missionary to Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, where he founded a Methodist church in Birchtown. He married there before settling in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

. In 1790 he returned to London. He wrote a memoir about his life, published in 1785 in London as ''A Narrative of the Lord's Wonderful Dealings with John Marrant, a black''; also published were a 1789 sermon, and a journal in 1790 covering the previous five years of his life.

Early life

Marrant was born free in

Marrant was born free in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

on June 15, 1755, the second youngest child in his family; he had two older sisters and an older brother, and a younger sister. Their father died in 1759 when Marrant was four.

His mother moved the family to

His mother moved the family to St. Augustine, Florida

St. Augustine ( ; es, San Agustín ) is a city in the Southeastern United States and the county seat of St. Johns County on the Atlantic coast of northeastern Florida. Founded in 1565 by Spanish explorers, it is the oldest continuously inhabi ...

, where Marrant started school, which was unique for black children. After 18 months in Florida and during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

, Marrant's mother moved the family to Georgia, which was a British colony at that time. He continued in school until the age of 11, learning to read and write. (His mother remarried at some time, and an older sister married in Charleston.) After they moved to Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

, Marrant became interested in music and learned to play the French horn

The French horn (since the 1930s known simply as the horn in professional music circles) is a brass instrument made of tubing wrapped into a coil with a flared bell. The double horn in F/B (technically a variety of German horn) is the horn most ...

and violin

The violin, sometimes known as a '' fiddle'', is a wooden chordophone ( string instrument) in the violin family. Most violins have a hollow wooden body. It is the smallest and thus highest-pitched instrument ( soprano) in the family in regu ...

. He frequently entertained the local gentry at balls and social gatherings. He studied music for a year and a half or two years and then he was an apprentice carpenter for more than one year.

Religious journey

At the age of 13, about 1768, Marrant and a friend went to hear

At the age of 13, about 1768, Marrant and a friend went to hear Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

preacher George Whitefield

George Whitefield (; 30 September 1770), also known as George Whitfield, was an Anglican cleric and evangelist who was one of the founders of Methodism and the evangelical movement.

Born in Gloucester, he matriculated at Pembroke College at ...

, who was active in the South during the Great Awakening

Great Awakening refers to a number of periods of religious revival in American Christian history. Historians and theologians identify three, or sometimes four, waves of increased religious enthusiasm between the early 18th century and the lat ...

. He experienced a dramatic conversion, falling to the floor in a faint or illness. Unable to move or speak for half an hour, he was carried from the meeting to his home. Doctors were called, but he refused medicine. He got better by studying the Bible, but his steadfastness to Biblical study was troubling to his family. It was about this time that his family became concerned about some bizarre behavior by Marrant. They treated him as if he was mentally unstable. After disagreements with his family about religion, he left home, and wandered into a forest outside the city, relying on God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

to feed and protect him.

He was found by a Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

hunter who knew his family but whom he persuaded not to take him back to town. Marrant traveled and hunted with the Cherokee for more than two months to gather furs for trade. They went to the man's fortified Cherokee town, where Marrant was stopped from entry. Told he did not have sufficient reason to be there, he was sentenced to death. Marrant's prayers to Jesus appeared to convert

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* "Conversion" (''Stargate Atlantis''), an episode of the television series

* "The Conversion" ...

the executioner, who argued with the sentencing judge and arranged for Marrant to meet the king, who spared his life. They all heard him pray in English and Cherokee.

Marrant lived with the Cherokee for two years during which he had visited with other tribes of the area, including Catawa, Housaw, and

Marrant lived with the Cherokee for two years during which he had visited with other tribes of the area, including Catawa, Housaw, and Creek people

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands He converted a number of Native Americans and is thought to have been an influence in creating lasting bonds between black and Cherokee people.

He wore Native American style clothing made of animal skins. He had no pants, but wore a sash around his middle, and a long pendant that went down his back. When he returned to Charleston, his family did not initially recognize him. Marrant was deeply relieved when his sister recognized him. He stated in his journal: "thus the dead was brought to life again; thus the lost was found." His experience is related to that of Lazarus and

He lived at

He lived at

Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the m ...

, both of whom were important figures among black Christians who were enslaved or held captive and longed for freedom and a rebirth. He sought work on plantations as a free carpenter, and conducted missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

work with slaves until the start of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. Although some owners objected, others allowed slaves to become Christianized.

American Revolutionary War

During theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, Marrant was impressed into the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

, serving as a musician for more than six years before being discharged in 1782. In 1780, he was at the Siege of Charleston

The siege of Charleston was a major engagement and major British victory in the American Revolutionary War, fought in the environs of Charles Town (today Charleston), the capital of South Carolina, between March 29 and May 12, 1780. The Britis ...

. One year later, he was wounded in the Battle of Dogger Bank. He described battles in his Narrative, but official records do not document him as having served with the Navy.

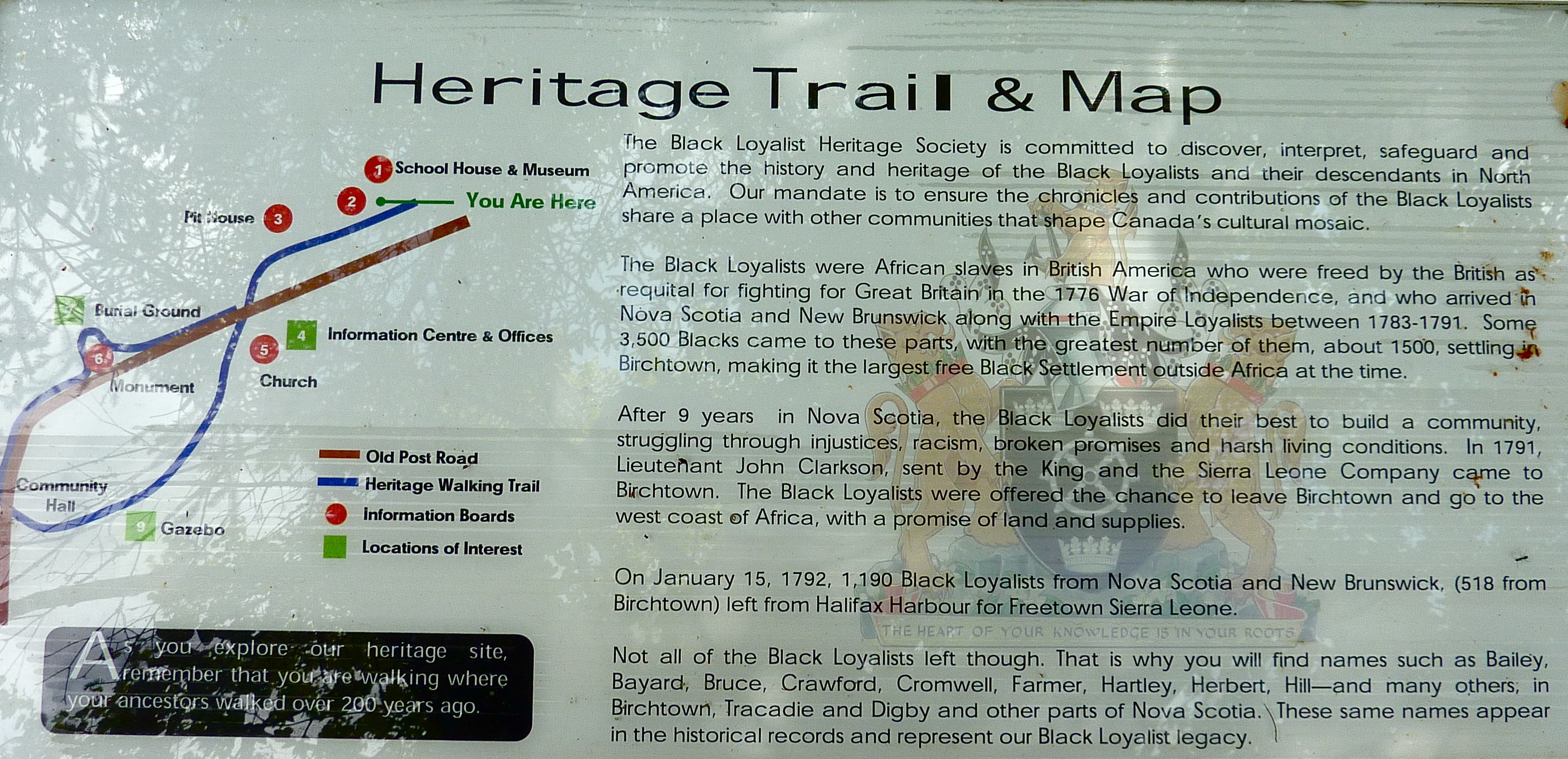

During the war, blacks slaves were told that if they served the British Crown, they would gain their freedom. There were 3,000 people who took the agreement and were called Black Loyalist

Black Loyalists were people of African descent who sided with the Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the C ...

s. In 1783, they were transported to Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

after their names were recorded in the Book of Negroes

The ''Book of Negroes'' is a document created by Brigadier General Samuel Birch, under the direction of Sir Guy Carleton, that records names and descriptions of 3,000 Black Loyalists, enslaved Africans who escaped to the British lines during ...

, also called the ''New York City Inspection Roll of Negroes''. The Black Loyalists were interested in learning about Christianity. Marrant's brother sent him a letter asking for him to come to Nova Scotia.

Ministry

Marrant worked for a clothing or cotton merchant in London after he was discharged from the Navy. While in London, he met Rev. Whitehead and told him of his dramatic conversion. Whitehead introduced him toSelina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon

Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon (24 August 1707 – 17 June 1791) was an English religious leader who played a prominent part in the religious revival of the 18th century and the Methodist movement in England and Wales. She founded an ...

, who encouraged him to become a minister. He thus joined the ministry of the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion

The Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion is a small society of evangelical churches, founded in 1783 by Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, as a result of the Evangelical Revival. For many years it was strongly associated with the Calvinist ...

, which was a sect that practiced a combination of Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

and Methodism. It separated from the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

in 1783. After he was ordained as a preacher on May 15, 1785 in Bath, Marrant left for Nova Scotia. After an eleven-week journey from England, he arrived in Nova Scotia in November 1785.

He lived at

He lived at Birchtown, Nova Scotia

Birchtown is a community and National Historic Site in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, located near Shelburne in the Municipal District of Shelburne County. Founded in 1783, the village was the largest settlement of Black Loyalists and t ...

, the largest new black community, where he founded a Huntingdonian church.Sidbury (2007), p. 87 Marrant served the black people in the Birchtown area and developed a strong Christian community there. He travelled throughout Nova Scotia to other towns where Black Loyalists settled, such as Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

and Cape Negro. He also spoke to white congregations and First Nation

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

people, the Miꞌkmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Miꞌkmaw'' or ''Miꞌgmaw''; ; ) are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the n ...

s. When he delivered sermons, he used specific Bible verses to infer that he was a prophet sent to Nova Scotia to help raise up the Black Loyalists that listen to him. Further, he said that those who did not listen to him would perish. These kinds of messages were threatening to white residents. Speaking to the hardships that blacks endured, he said that lessons from God where often hidden: "God often hides the sensible signs of his favor from his dearest friends… real Christians, whilst they are among fiery serpents are awaiting with desire, and holy expectations, for the good of the promise."

He had difficulty among other churches, particularly other Methodist churches. White ministers were especially upset when members of their congregations attended Marrant's services. He inspired the creation of Christian faith among black communities, including religious leaders Boston King Boston King ( 1760–1802) was a former American slave and Black Loyalist, who gained freedom from the British and settled in Nova Scotia after the American Revolutionary War. He later immigrated to Sierra Leone, where he helped found Freetown and b ...

, John Ball, and Moses Wilkinson

Moses "Daddy Moses" Wilkinson or "Old Moses" (c. 1746/47 Wilkinson's entry in the Book of Negroes gives his age as 36. – ?) was an American Wesleyan Methodist preacher and Black Loyalist. His ministry combined Old Testament divination with ...

, who were Methodists. Another was David George, a Baptist.

He did not receive the monies he expected from the Countess for his missionary work in Nova Scotia and suffered a six-month bout of smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

. In 1787, Marrant traveled to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

. The next year, he became the chaplain of the African Masonic Lodge in Boston, a group active in the movement to abolish slavery in the United States. This was one of the first American organizations to have the name "African" in its title, representing the emerging identity of people of African descent in the United States after the Revolution. In a speech at the Lodge, published in 1789, Marrant described the black people as "an essentially distinct nation within a Christian universalist family of mankind."Sidbury (2007), p. 88

Author

In 1785, with the help of Rev. William Aldridge, he published ''A Narrative of the Lord's Wonderful Dealings with John Marrant, A Black'', with the assistance of William Aldridge, who transcribed it. The narrative told of his time living with Cherokee people, and became one of the most popular stories of that kind. It also told of his conversion to Christianity and his observances of the condition and experiences of blacks in the Colonial period. Critics have noted that the narrative has a very different tone to his later publications. ScholarHenry Louis Gates Jr.

Henry Louis "Skip" Gates Jr. (born September 16, 1950) is an American literary critic, professor, historian, and filmmaker, who serves as the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African Amer ...

has argued in ''The Signifying Monkey'' that many early African-American narratives were transcribed by white editors, who sometimes influenced the style of such narratives.

Marrant delivered a sermon ''A Sermon Preached on the 24th Day of June 1789...at the Request of the Right Worshipful the Grand Master Prince Hall, and the Rest of the Brethren of the African Lodge of the Honorable Society of Free and Accepted Masons in Boston'' in 1789 noting the equality of men before God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

; it was published. His final published work was a 1790 journal, ''A Journal of the Rev. John Marrant, from August the 18th, 1785, to the 16th of March, 1790''.

Personal life

He married Elizabeth Herries, whose parents were Black Loyalists, on August 15, 1788 at Birchtown, Nova Scotia and returned with her to Boston. In a letter to Marrant, Margaret Blucke (wife of Stephen Blucke), asked about Marrant's children. He may have been previously married or adopted children. There is also boy that travelled with him. His name is not mentioned in the ''Journal'', but he may have been Anthony Elliot from Birchtown who was an assistant. Marrant traveled toLondon

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

in 1789 or 1790, where the journal of the previous five years was published. He preached in chapels in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, including the Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a district in East London and the future administrative centre of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a part of the East End of London, east of Charing Cross. Part of the historic county of Middlesex, the area formed ...

area. He died on April 15, 1791 in Islington and was buried at the chapel graveyard on Church Street.

Legacy

Marrant did not live a long life, but he influenced black people in the United States and Canada, including the Black Loyalists who settled inSierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

in Africa in 1792. He inspired future generations through his narrative. He shared a message of perseverance and faith.

Notes

References

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Marrant, John 1755 births 1791 deaths Converts to Methodism American evangelicals African-American writers American writers African-American Methodist clergy American Methodist clergy Clergy of historically African-American Christian denominations Writers from New York City American Methodist missionaries African-American musicians Methodist missionaries in the United States African-American missionaries