John Isaac Hawkins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Isaac Hawkins (1772–1855) was an inventor who practised civil engineering.

He was known as the co-inventor of the ever-pointed pencil, an early

John Isaac Hawkins (1772–1855) was an inventor who practised civil engineering.

He was known as the co-inventor of the ever-pointed pencil, an early

Google Books.

/ref>

*Experiments in 1810–11 for a brick pedestrian tunnel under the Thames, with Charles Wyatt, proposal to the

*Experiments in 1810–11 for a brick pedestrian tunnel under the Thames, with Charles Wyatt, proposal to the

*Samuel Thompson, ''Reminiscences of a Canadian Pioneer for the Last Fifty Years: An Autobiography'', Toronto: Hunter, Rose & Company, 1884, pp. 11, 1

*

John Isaac Hawkins (1772–1855) was an inventor who practised civil engineering.

He was known as the co-inventor of the ever-pointed pencil, an early

John Isaac Hawkins (1772–1855) was an inventor who practised civil engineering.

He was known as the co-inventor of the ever-pointed pencil, an early mechanical pencil

A mechanical pencil, also clutch pencil, is a pencil with a replaceable and mechanically extendable solid pigment core called a "lead" . The lead, often made of graphite, is not bonded to the outer casing, and can be mechanically extended as its ...

, and of the upright piano.

Early life

Hawkins was born 14 March 1772 atTaunton

Taunton () is the county town of Somerset, England, with a 2011 population of 69,570. Its thousand-year history includes a 10th-century monastic foundation, Taunton Castle, which later became a priory. The Normans built a castle owned by the ...

, Somerset, England,R. L. Tafel, ''Documents Concerning Swedenborg'', p. 1217 the son of Joan Wilmington and her husband Isaac Hawkins, a watchmaker. The father, Isaac Hawkins, would become a Wesleyan

Wesleyan theology, otherwise known as Wesleyan– Arminian theology, or Methodist theology, is a theological tradition in Protestant Christianity based upon the ministry of the 18th-century evangelical reformer brothers John Wesley and Charle ...

minister, but was expelled by John Wesley

John Wesley (; 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, theologian, and evangelist who was a leader of a revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies he founded became the dominant form of the independent Meth ...

; and after moving the family to Moorfields

Moorfields was an open space, partly in the City of London, lying adjacent to – and outside – its northern wall, near the eponymous Moorgate. It was known for its marshy conditions, the result of the defensive wall acting like a dam, ...

in London he was a minister in the Swedenborgian

The New Church (or Swedenborgianism) is any of several historically related Christian denominations that developed as a new religious group, influenced by the writings of scientist and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772).

Swedenborgian or ...

movement, which John Isaac would also follow. John Isaac emigrated to the United States about 1790, attending the College of New Jersey, where he studied medicine and later, chemical filtration.

Hawkins married in New Jersey, and was living at Bordentown and Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

. In his own account, he was influenced by work of Georg Moritz Lowitz to try charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ...

for filtration purposes, and ran an exhibition on the topic, with Raphaelle and Rembrandt Peale, in the Philadelphia Exchange Coffee House. He operated a non-vocational craft school in Bristol, Pennsylvania

Bristol is a borough in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, United States. It is located northeast of Center City Philadelphia, opposite Burlington, New Jersey on the Delaware River. It antedates Philadelphia, being settled in 1681 and first incorpora ...

from about 1800; and he collaborated on inventions with Rev. Burgess Allison.A. W. Skempton (editor), ''A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland: 1500–1830'' (2002), pp. 305–6Google Books.

/ref>

In London

Hawkins returned to England in 1803, and opened a London sugar refinery. He also worked as apatent agent

A patent attorney is an attorney who has the specialized qualifications necessary for representing clients in obtaining patents and acting in all matters and procedures relating to patent law and practice, such as filing patent applications and o ...

and consultant at this period. He set up a museum of "useful mechanical inventions", featuring a number of his own, as reported in the '' Monthly Magazine'' in 1808. He also continued inventing and performed "experiments of a delightfully awful character". As a Swedenborgian, he associated with Manoah Sibly, becoming secretary of the "London Conference" in 1814 when Sibly was president. He took an interest in phrenology

Phrenology () is a pseudoscience which involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits.Wihe, J. V. (2002). "Science and Pseudoscience: A Primer in Critical Thinking." In ''Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience'', pp. 195–203. C ...

from 1815, for the rest of his life. Hawkins and his wife adopted from the workhouse a child, James Chalmers, orphaned after his parents had entered the Poyais project of Gregor MacGregor

General Gregor MacGregor (24 December 1786 – 4 December 1845) was a Scottish soldier, adventurer, and confidence trickster who attempted from 1821 to 1837 to draw British and French investors and settlers to "Poyais", a fictional Central A ...

; he died young.

Hawkins joined the Institution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters are located in the UK, whi ...

in 1824. In 1825, he went to Vienna to superintend the construction of a beet sugar works there, and subsequently did the same in Paris. Back in London, where his wife Anna died in 1838, he superintended the construction of the Thames Tunnel

The Thames Tunnel is a tunnel beneath the River Thames in London, connecting Rotherhithe and Wapping. It measures 35 feet (11 m) wide by 20 feet (6 m) high and is 1,300 feet (396 m) long, running at a depth of ...

under Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "on ...

.Thompson, ''Reminiscences'', 17 Hawkins also served as president of the Anthropological Society of London, a phrenological group.

Later life

Later in life Hawkins fell into debt and concluding that America presented a better opportunity to profit from his patents, he decided to re-emigrate, departing in autumn 1848.Tafel, ''Documents Concerning Swedenborg'', p. 1218 Returning to New Jersey, "as a grey old man" he lived with his third wife "who was barely out of her teens". Lectures there for local ladies could not survive their disapproval of his display of human skulls or the preserved organs of his deceased adopted son, his only child, whom he had dissected following the boy's death at age seven. He published the ''Journal of Human Nature and Human Progress'', but this was short-lived, and he died in poverty and relative obscurity at Rahway or Elizabethtown, New Jersey, 28 June 1855.Pianino

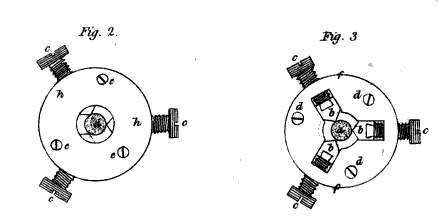

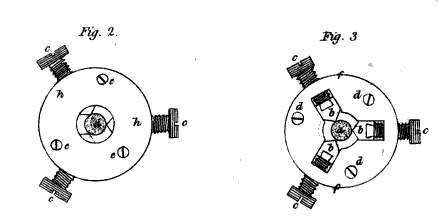

Hawkins was the first to see the importance of using iron in pianoforte framing. He was living in Philadelphia when he invented and first produced the pianino or cottage pianoforte – the "portable grand" as he then called it – which he patented in 1800.Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

bought one, of 5½ octaves, for $264.

There had been upright grand piano

The piano is a stringed keyboard instrument in which the strings are struck by wooden hammers that are coated with a softer material (modern hammers are covered with dense wool felt; some early pianos used leather). It is played using a keybo ...

s as well as upright harpsichords

A harpsichord ( it, clavicembalo; french: clavecin; german: Cembalo; es, clavecín; pt, cravo; nl, klavecimbel; pl, klawesyn) is a musical instrument played by means of a keyboard. This activates a row of levers that turn a trigger mechanism ...

, the horizontal instrument being turned up on its wider end and a keyboard and action adapted to it. William Southwell, an Irish piano-maker, had in 1798 tried a similar experiment with a square piano, to be repeated in later years by William Frederick Collard of London; but Hawkins was the first to make a piano, or pianino, with the strings descending to the floor, the keyboard being raised. His instrument was in a complete iron frame, independent of the case; and in this frame, strengthened by a system of iron resistance rods combined with an iron upper bridge, his sound-board was entirely suspended. An apparatus for tuning by mechanical screws regulated the tension of the strings, which were of equal length throughout. The action, in metal supports, anticipated Robert Wornum

Robert Wornum (1780–1852) was a piano maker working in London during the first half of the 19th century. He is best known for introducing small cottage and oblique uprights and an action considered to be the predecessor of the modern upright ac ...

's in the checking, and later ideas in a contrivance for repetition. This bundle of inventions was brought to London and exhibited by Hawkins himself; but the instrument was poor in tone.

Other inventions, proposals and works

*Patented (1802) an improvedphysiognotrace

A physiognotrace is an instrument, designed to trace a person's physiognomy to make semi-automated portrait aquatints. Invented in France in 1783–1784, it was popular for some decades. The sitter climbed into a wooden frame (1.75m high x 0.65m ...

, a device by which one could quickly produce a silhouette

A silhouette ( , ) is the image of a person, animal, object or scene represented as a solid shape of a single colour, usually black, with its edges matching the outline of the subject. The interior of a silhouette is featureless, and the silhou ...

portrait (i.e. a paper cut-out profile).

*Invented and obtained a patent in 1803 for the polygraph

A polygraph, often incorrectly referred to as a lie detector test, is a device or procedure that measures and records several physiological indicators such as blood pressure, pulse, respiration, and skin conductivity while a person is asked ...

, a mechanism for producing a duplicate copy while a handwritten original was created. This is credited with being the first autopen. Charles Willson Peale

Charles Willson Peale (April 15, 1741 – February 22, 1827) was an American Painting, painter, soldier, scientist, inventor, politician and naturalist. He is best remembered for his portrait paintings of leading figures of the American Revolu ...

made the first, and sold it to Benjamin Henry Latrobe

Benjamin Henry Boneval Latrobe (May 1, 1764 – September 3, 1820) was an Anglo-American neoclassical architect who emigrated to the United States. He was one of the first formally trained, professional architects in the new United States, dra ...

. Latrobe then showed it to Thomas Jefferson, who took an interest in the invention.

*Experimented with machines for reproducing sculptures (1804). Later Benjamin Cheverton took up the idea, making a reducing machine for sculptures (1828), and exhibiting it at the Great Exhibition of 1851

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition which took pl ...

. It was a type of engine lathe, explained by Hawkins in the British Association meeting, Section G, in 1837.

*For water filtration

A water filter removes impurities by lowering contamination of water using a fine physical barrier, a chemical process, or a biological process. Filters cleanse water to different extents, for purposes such as: providing agricultural irrigation ...

(1808) *Experiments in 1810–11 for a brick pedestrian tunnel under the Thames, with Charles Wyatt, proposal to the

*Experiments in 1810–11 for a brick pedestrian tunnel under the Thames, with Charles Wyatt, proposal to the Thames Archway Company

The Thames Archway Company was a company formed in 1805 to build the first tunnel under the Thames river in London.

The development of dockyards on both sides of the river around the Isle of Dogs indicated that a river crossing of some kind was n ...

*The mechanical pencil (1822); the rights were sold to Sampson Mordan and Gabriel Riddle.

* Trifocal corrective eyeglass lenses, patented in 1827, also coining the name "bifocal" for the dual focal length lenses invented by Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading int ...

*Sugar refining

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or doubl ...

, by the method of Edward Charles Howard for whom he had worked.

*The iridium

Iridium is a chemical element with the symbol Ir and atomic number 77. A very hard, brittle, silvery-white transition metal of the platinum group, it is considered the second-densest naturally occurring metal (after osmium) with a density o ...

-tipped gold pen (1834). Platinum-nib pens with iridium tips sold at a guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

.

*Translated ''A Treatise on the Teeth of Wheels'' from the French of Charles Étienne Louis Camus

Charles Étienne Louis Camus (25 August 1699 – 2 February 1768), was a French mathematician and mechanician who was born at Crécy-en-Brie, near Meaux.

He studied mathematics, civil and military architecture, and astronomy after leaving Collè ...

, and advocated involute

In mathematics, an involute (also known as an evolvent) is a particular type of curve that is dependent on another shape or curve. An involute of a curve is the locus of a point on a piece of taut string as the string is either unwrapped from o ...

profile for gears (by 1840)

*Perfected Perkins' steam gun, intended to eliminate warfare by making resistance impossible.Thompson, ''Reminiscences'', p. 15

References

;Attribution *R. L. Tafel, ''Documents Concerning the Life and Character of Emanuel Swedenborg'', vol. 2, part 2, London: Swedenborg Society, 1877, p. 121*Samuel Thompson, ''Reminiscences of a Canadian Pioneer for the Last Fifty Years: An Autobiography'', Toronto: Hunter, Rose & Company, 1884, pp. 11, 1

*

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hawkins, John Isaac 1772 births 1855 deaths English inventors English engineers Phrenologists English Swedenborgians