John Ireland (bishop) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Ireland (baptized September 11, 1838 – September 25, 1918) was an American religious leader who was the third Roman Catholic bishop and first Roman Catholic archbishop of Saint Paul, Minnesota (1888–1918). He became both a religious as well as civic leader in

/ref> He was the second of seven children born to Richard Ireland, a carpenter, and his second wife, Judith Naughton. His family immigrated to the United States in 1848 and eventually moved to

Disturbed by reports that Catholic immigrants in eastern cities were suffering from social and economic handicaps, Ireland and

Disturbed by reports that Catholic immigrants in eastern cities were suffering from social and economic handicaps, Ireland and

Ireland advocated state support and inspection of Catholic schools. After several parochial schools were in danger of closing, Ireland sold them to the respective city's board of education. The schools continued to operate with nuns and priests teaching, but no religious teaching was allowed. This plan, the Faribault–Stillwater plan, or Poughkeepsie plan, created enough controversy that Ireland was forced to travel to

Ireland advocated state support and inspection of Catholic schools. After several parochial schools were in danger of closing, Ireland sold them to the respective city's board of education. The schools continued to operate with nuns and priests teaching, but no religious teaching was allowed. This plan, the Faribault–Stillwater plan, or Poughkeepsie plan, created enough controversy that Ireland was forced to travel to

In 1891, Ireland refused to accept the clerical credentials of Byzantine Rite, Ruthenian Catholic

In 1891, Ireland refused to accept the clerical credentials of Byzantine Rite, Ruthenian Catholic

At the

At the

BioIreland, John (1838-1918)

MNopedia. *

The Church and Modern Society

' on Internet Archive *

Bishop Ireland's Connemara Experiment:

'' Minnesota Historical Society'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Ireland, John 1838 births 1918 deaths History of Saint Paul, Minnesota Irish emigrants to the United States (before 1923) People from County Kilkenny Roman Catholic bishops of Saint Paul Roman Catholic archbishops of Saint Paul 19th-century Roman Catholic archbishops in the United States 20th-century Roman Catholic archbishops in the United States Union Army chaplains 19th-century Irish people

Saint Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

during the turn of the 20th century. Ireland was known for his progressive stance on education, immigration and relations between church and state, as well as his opposition to saloons and political corruption. He promoted the Americanization

Americanization or Americanisation (see spelling differences) is the influence of American culture and business on other countries outside the United States of America, including their media, cuisine, business practices, popular culture, te ...

of Catholicism, especially in the furtherance of progressive social ideals. He was a leader of the modernizing element in the Roman Catholic Church during the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

. He created or helped to create many religious and educational institutions in Minnesota. He is also remembered for his acrimonious relations with Eastern Catholics

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also called the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous ('' sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

.

History

John Ireland was born in Burnchurch, County Kilkenny,Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, and was baptized on September 11, 1838.Shannon, J. P. "Ireland, John" ''New Catholic Encyclopedia'', Vol. 7. 2nd ed. Detroit: Gale, 2003/ref> He was the second of seven children born to Richard Ireland, a carpenter, and his second wife, Judith Naughton. His family immigrated to the United States in 1848 and eventually moved to

Saint Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul (abbreviated St. Paul) is the capital of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Ramsey County. Situated on high bluffs overlooking a bend in the Mississippi River, Saint Paul is a regional business hub and the center ...

, in 1852. One year later Joseph Crétin

Joseph Crétin (19 December 1799 – 22 February 1857) was the first Roman Catholic Bishop of Saint Paul, Minnesota. Cretin Avenue in St. Paul, Cretin-Derham Hall High School, and Cretin Hall at the University of St. Thomas are named for him. ...

, first bishop of Saint Paul, sent Ireland to the preparatory seminary of Meximieux in France. Ireland was consequently ordained in 1861 in Saint Paul. He served as a chaplain of the Fifth Minnesota Regiment in the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

until 1863 when ill health caused his resignation. Later, he was famous nationwide in the Grand Army of the Republic

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army (United States Army), Union Navy (U.S. Navy), and the Marines who served in the American Civil War. It was founded in 1866 in Decatur, Il ...

.

He was appointed pastor at Saint Paul's cathedral in 1867, a position which he held until 1875. In 1875, he was made coadjutor bishop of St. Paul and in 1884 he became bishop ordinary. In 1888 he became archbishop with the elevation of his diocese and the erection of the ecclesiastical province of Saint Paul. Ireland retained this title for 30 years until his death in 1918. Before Ireland died he burned all his personal papers.Empson, ''The Streets Where You Live'', 144

Ireland was personal friends with Presidents William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

and Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

. At a time when most Irish Catholics were staunch Democrats, Ireland was known for being close to the Republican party. He opposed racial inequality

Social inequality occurs when resources in a given society are distributed unevenly, typically through norms of allocation, that engender specific patterns along lines of socially defined categories of persons. It posses and creates gender c ...

and called for "equal rights and equal privileges, political, civil, and social."

Ireland's funeral was attended by eight archbishops, thirty bishops, twelve monsignors, seven hundred priests and two hundred seminarians.

He was awarded an honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hon ...

(LL.D.

Legum Doctor (Latin: “teacher of the laws”) (LL.D.) or, in English, Doctor of Laws, is a doctorate-level academic degree in law or an honorary degree, depending on the jurisdiction. The double “L” in the abbreviation refers to the early ...

) by Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

in October 1901, during celebrations for the bicentenary of the university.

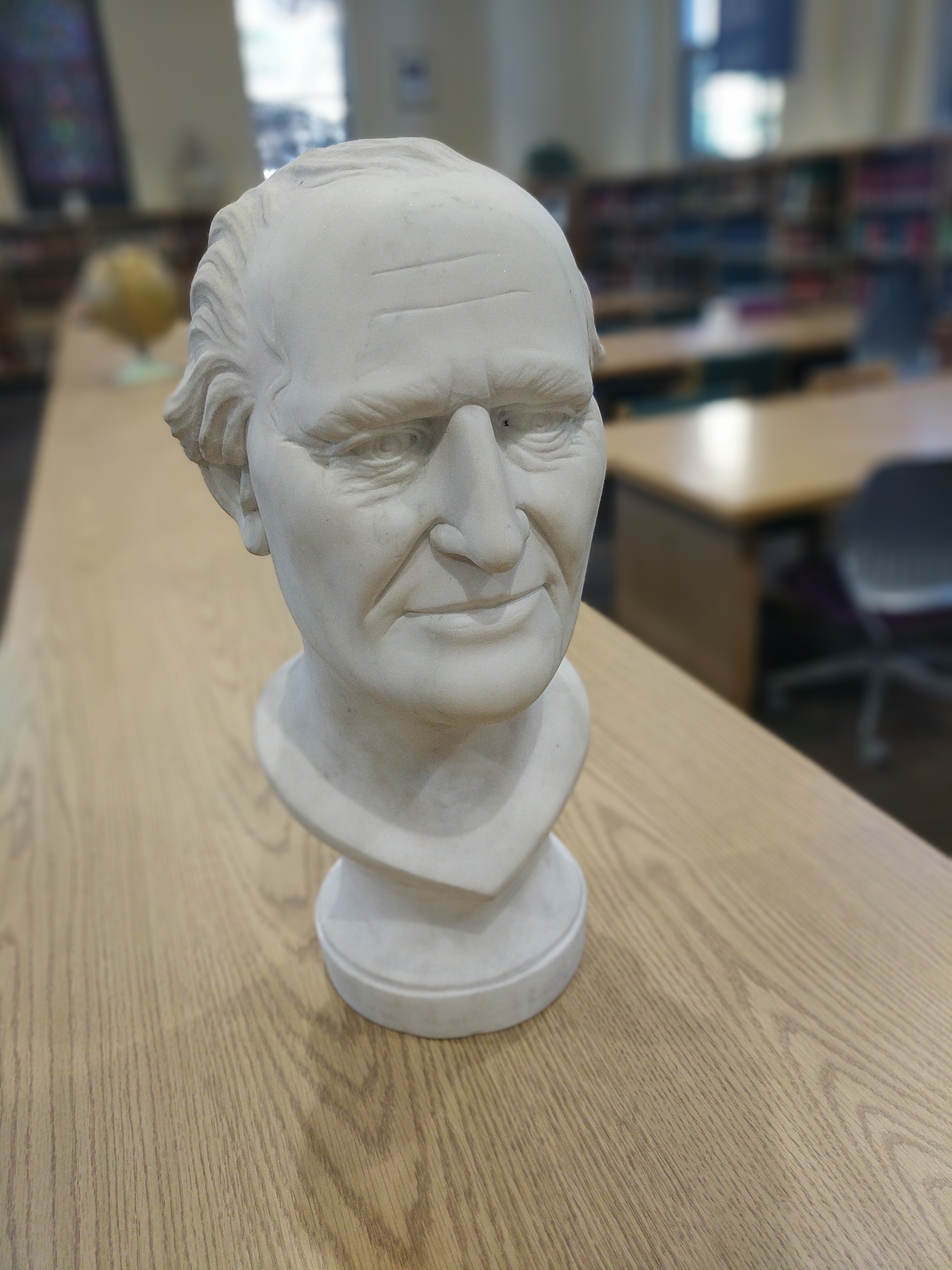

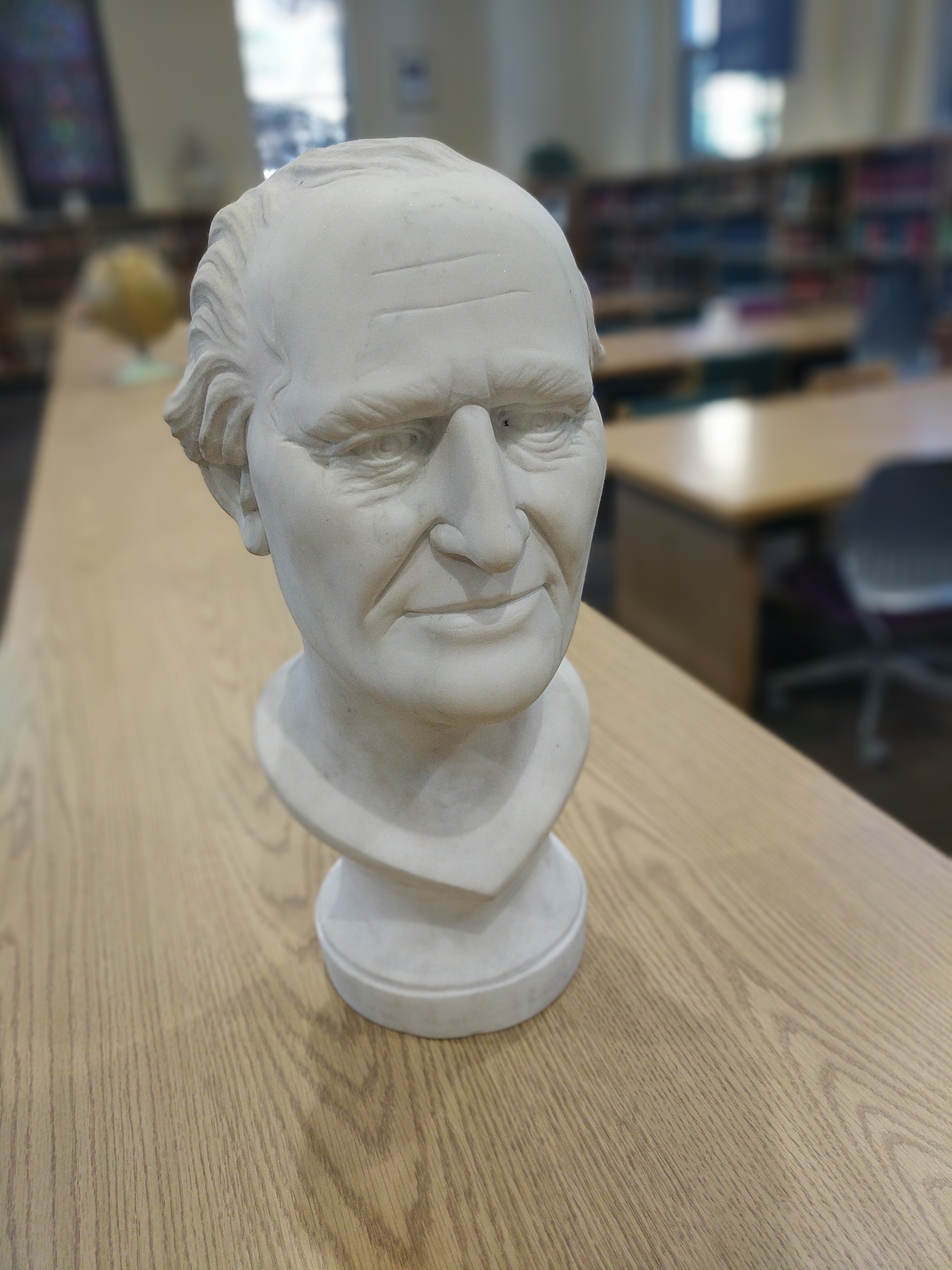

A friend of James J. Hill

James Jerome Hill (September 16, 1838 – May 29, 1916) was a Canadian-American railroad director. He was the chief executive officer of a family of lines headed by the Great Northern Railway, which served a substantial area of the Upper Midwes ...

, whose wife Mary was Catholic (even though Hill was not), Archbishop Ireland had his portrait painted in 1895 by the Swiss-born American portrait painter Adolfo Müller-Ury

Adolfo Müller-Ury, KSG (March 29, 1862 – July 6, 1947) was a Swiss-born American portrait painter and impressionistic painter of roses and still life.

Heritage and early life in Switzerland

He was born Felice Adolfo Müller on 29 March ...

almost certainly on Hill's behalf, which was exhibited at M. Knoedler & Co., New York, January 1895 (lost) and again in 1897 (Archdiocesan Archives, Archdiocese of Saint Paul & Minneapolis).

Legacy

The influence of his personality made Archbishop Ireland a commanding figure in many important movements, especially those fortotal abstinence

Teetotalism is the practice or promotion of total personal abstinence from the psychoactive drug alcohol, specifically in alcoholic drinks. A person who practices (and possibly advocates) teetotalism is called a teetotaler or teetotaller, or is ...

, for colonization in the Northwest, and modern education. Ireland became a leading civic and religious leader during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Saint Paul. He worked closely with non-Catholics and was recognized by them as a leader of the modernizing Catholics.

Ireland called for racial equality at a time in the U.S. when the concept was considered extreme. On May 5, 1890, he gave a sermon at St. Augustine's Church, in Washington, D.C., the center of an African-American parish, to a congregation that included several public officials, Congressmen including the full Minnesota delegation, U.S. Treasury Secretary William Windom

William Windom (May 10, 1827January 29, 1891) was an American politician from Minnesota. He served as U.S. Representative from 1859 to 1869, and as U.S. Senator from 1870 to January 1871, from March 1871 to March 1881, and from November 1881 ...

, and Blanche Bruce

Blanche Kelso Bruce (March 1, 1841March 17, 1898) was born into slavery in Prince Edward County, Virginia, and went on to become a politician who represented Mississippi as a Republican in the United States Senate from 1875 to 1881. He was ...

, the second black U.S. Senator. Ireland's sermon on racial justice concluded with the statement, "The color line must go; the line will be drawn at personal merit." It was reported that "the bold and outspoken stand of the Archbishop on this occasion created somewhat of a sensation throughout America."

Colonization

Disturbed by reports that Catholic immigrants in eastern cities were suffering from social and economic handicaps, Ireland and

Disturbed by reports that Catholic immigrants in eastern cities were suffering from social and economic handicaps, Ireland and Bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is c ...

John Lancaster Spalding

John Lancaster Spalding (June 2, 1840 – August 25, 1916) was an American author, poet, advocate for higher education, the first bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Peoria from 1877 to 1908 and a co-founder of The Catholic University of Ameri ...

of the Diocese of Peoria

The Diocese of Peoria ( la, Diœcesis Peoriensis, Peoria, Illinois) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in the central Illinois region of the United States. The Diocese of Peoria is a suffragan diocese w ...

, Illinois, founded the Irish Catholic Colonization Association. This organization bought land in rural areas to the west and south and helped resettle Irish Catholics from the urban slums.

Ireland helped establish many Irish Catholic colonies in Minnesota. The land had been cleared of its native Sioux following the Dakota War of 1862

The Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising, the Dakota Uprising, the Sioux Outbreak of 1862, the Dakota Conflict, the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, or Little Crow's War, was an armed conflict between the United States and several ban ...

. He served as director of the National Colonization Association. From 1876 to 1881 Ireland organized and directed the most successful rural colonization program ever sponsored by the Catholic Church in the U.S. Working with the western railroads and with the Minnesota state government, he brought more than 4,000 Catholic families from the slums of eastern urban areas and settled them on more than of farmland in rural Minnesota.

His partner in Ireland was John Sweetman, a wealthy brewer who helped set up the Irish-American Colonisation Company there.

In 1880 Ireland assisted several hundred people from Connemara

Connemara (; )( ga, Conamara ) is a region on the Atlantic coast of western County Galway, in the west of Ireland. The area has a strong association with traditional Irish culture and contains much of the Connacht Irish-speaking Gaeltacht, ...

in Ireland to emigrate to Minnesota. They arrived at the wrong time of the year and had to be assisted by local Freemasons, an organisation that the Catholic Church condemns on many points. In the public debate that followed, the immigrants, being Gaelic speakers, could not voice their opinions of Bishop Ireland's criticism of their acceptance of the Masons' support during a harsh winter. De Graff and Clontarf in Swift County, Adrian

Adrian is a form of the Latin given name Adrianus or Hadrianus. Its ultimate origin is most likely via the former river Adria from the Venetic and Illyrian word ''adur'', meaning "sea" or "water".

The Adria was until the 8th century BC the mai ...

in Nobles County, Avoca, Iona and Fulda in Murray County, Graceville in Big Stone County and Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded i ...

in Lyon County were all colonies established by Ireland.

Charlotte Grace O'Brien

Charlotte Grace O'Brien (23 November 1845 – 3 June 1909) was an Irish author and philanthropist and an activist in nationalist causes and the protection of female emigrants. She is known also as a plant collector.

Life

Early life

Born on 23 ...

, philanthropist and activist for the protection of female emigrants, found that often the illiterate young women were being tricked into prostitution through spurious offers of employment. She proposed an information bureau at Castle Garden

Castle Clinton (also known as Fort Clinton and Castle Garden) is a circular sandstone fort within Battery Park at the southern end of Manhattan in New York City. Built from 1808 to 1811, it was the first American immigration station, predating ...

, the disembarkation point for immigrants arriving in New York; a temporary shelter to provide accommodation for immigrants, and a chapel, all to Archbishop Ireland, whom she believed of all the American hierarchy would be most sympathetic. Ireland agreed to raise the matter at the May 1883 meeting of the Irish Catholic Association which endorsed the plan and voted to establish an information bureau at Castle Garden. The Irish Catholic Colonization Association was also instrumental in the establishment of the Mission of Our Lady of the Rosary for the Protection of Irish Immigrant Girls.

Education

Ireland advocated state support and inspection of Catholic schools. After several parochial schools were in danger of closing, Ireland sold them to the respective city's board of education. The schools continued to operate with nuns and priests teaching, but no religious teaching was allowed. This plan, the Faribault–Stillwater plan, or Poughkeepsie plan, created enough controversy that Ireland was forced to travel to

Ireland advocated state support and inspection of Catholic schools. After several parochial schools were in danger of closing, Ireland sold them to the respective city's board of education. The schools continued to operate with nuns and priests teaching, but no religious teaching was allowed. This plan, the Faribault–Stillwater plan, or Poughkeepsie plan, created enough controversy that Ireland was forced to travel to Vatican City

Vatican City (), officially the Vatican City State ( it, Stato della Città del Vaticano; la, Status Civitatis Vaticanae),—'

* german: Vatikanstadt, cf. '—' (in Austria: ')

* pl, Miasto Watykańskie, cf. '—'

* pt, Cidade do Vati ...

to defend it, and he succeeded in doing so. He also opposed the use of foreign languages in American Catholic churches and parochial schools. The use of foreign languages was not uncommon at the time because of the recent large influx of immigrants to the U.S. from European countries. Ireland influenced American society by actively promoting the use of the English language by large numbers of German immigrants. He is the author of ''The Church and Modern Society'' (1897).

Relations with Eastern Catholics

In 1891, Ireland refused to accept the clerical credentials of Byzantine Rite, Ruthenian Catholic

In 1891, Ireland refused to accept the clerical credentials of Byzantine Rite, Ruthenian Catholic priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in partic ...

Alexis Toth

Alexis Georgievich Toth (or Alexis of Wilkes-Barre; March 18, 1853 – May 7, 1909) was a Russian Orthodox church leader in the Midwestern United States who, having resigned his position as a Byzantine Catholic priest in the Ruthenian Catholi ...

, despite Toth's being a widower. Ireland then forbade Toth to minister to his own parishioners, despite the fact that Toth had jurisdiction from his own bishop and did not answer to Ireland. Ireland was also involved in efforts to expel all non-Latin Church

, native_name_lang = la

, image = San Giovanni in Laterano - Rome.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, alt = Façade of the Archbasilica of St. John in Lateran

, caption = Archbasilica of Saint Joh ...

Catholic clergy from the United States. Forced into an impasse, Toth went on to lead thousands of Ruthenian Catholics out of the Roman Communion and into what would eventually become the Orthodox Church in America

The Orthodox Church in America (OCA) is an Eastern Orthodox Christian church based in North America. The OCA is partly recognized as autocephalous and consists of more than 700 parishes, missions, communities, monasteries and institutions ...

. Because of this, Archbishop Ireland is sometimes referred to, ironically, as "The Father of the Orthodox Church in America". Marvin R. O'Connell, author of a biography of Ireland, summarizes the situation by stating that "if Ireland's advocacy of the blacks displayed him at his best, his belligerence toward the Uniates showed him at his bull-headed worst."

Establishments

At the

At the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore

The Plenary Councils of Baltimore were three national meetings of Catholic bishops in the United States in 1852, 1866 and 1884 in Baltimore, Maryland.

During the early history of the Roman Catholic Church in the United States all of the diocese ...

the establishment of a Catholic university was decided. In 1885 Ireland was appointed to a committee, along with, Bishop John Lancaster Spalding

John Lancaster Spalding (June 2, 1840 – August 25, 1916) was an American author, poet, advocate for higher education, the first bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Peoria from 1877 to 1908 and a co-founder of The Catholic University of Ameri ...

, Cardinal James Gibbons

James Cardinal Gibbons (July 23, 1834 – March 24, 1921) was a senior-ranking American prelate of the Catholic Church who served as Apostolic Vicar of North Carolina from 1868 to 1872, Bishop of Richmond from 1872 to 1877, and as ninth ...

and then bishop John Joseph Keane dedicated to developing and establishing The Catholic University of America

The Catholic University of America (CUA) is a private Roman Catholic research university in Washington, D.C. It is a pontifical university of the Catholic Church in the United States and the only institution of higher education founded by U.S. ...

in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

Ireland retained an active interest in the University for the rest of his life.

He founded Saint Thomas Aquinas Seminary, progenitor of four institutions: University of Saint Thomas (Minnesota), the Saint Paul Seminary School of Divinity

The Saint Paul Seminary (SPS) is a Roman Catholic major seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota. A part of the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, SPS prepares men to enter the priesthood and permanent diaconate, and educates lay men and women on ...

, Nazareth Hall Preparatory Seminary, and Saint Thomas Academy

Saint Thomas Academy (abbr. STA), originally known as St. Thomas Aquinas Seminary and formerly known as St. Thomas Military Academy, is the only all-male, Catholic, college-preparatory, military high school in Minnesota. It is located in Mendota ...

. The Saint Paul Seminary was established with the help of Methodist James J. Hill

James Jerome Hill (September 16, 1838 – May 29, 1916) was a Canadian-American railroad director. He was the chief executive officer of a family of lines headed by the Great Northern Railway, which served a substantial area of the Upper Midwes ...

, whose wife, Mary Mehegan, was a devout Catholic.Empson, ''The Streets Where You Live'', 143 Both institutions are located on the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

. DeLaSalle High School located on Nicollet Island in Minneapolis was opened in October 1900 through a gift of $25,000 from Ireland. Fourteen years later Ireland purchased an adjacent property for the expanding Christian Brothers school.

In 1904 Ireland secured the land for the building of the current Cathedral of Saint Paul located atop Summit Hill, the highest point in downtown Saint Paul. At the same time, on Christmas Day 1903 he also commissioned the construction of the almost equally large Church of Saint Mary, for the Immaculate Conception parish in the neighboring city of Minneapolis. It became the Pro-Cathedral of Minneapolis and later became the Basilica of Saint Mary, the first basilica in the United States in 1926. Both were designed and built under the direction of the French architect Emmanuel Louis Masqueray.

John Ireland Boulevard, a Saint Paul street that runs from the Cathedral of Saint Paul northeast to the Minnesota State Capitol

The Minnesota State Capitol is the seat of government for the U.S. state of Minnesota, in its capital city of Saint Paul. It houses the Minnesota Senate, Minnesota House of Representatives, the office of the Attorney General and the office ...

, is named in his honor. It was so named in 1961 at the encouragement of the Ancient Order of Hibernians

The Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH; ) is an Irish Catholic fraternal organization. Members must be male, Catholic, and either born in Ireland or of Irish descent. Its largest membership is now in the United States, where it was founded in N ...

.

References

Further reading

* * * . Pages 143-144 * *External links

* *Bio

MNopedia. *

The Church and Modern Society

' on Internet Archive *

Bishop Ireland's Connemara Experiment:

'' Minnesota Historical Society'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Ireland, John 1838 births 1918 deaths History of Saint Paul, Minnesota Irish emigrants to the United States (before 1923) People from County Kilkenny Roman Catholic bishops of Saint Paul Roman Catholic archbishops of Saint Paul 19th-century Roman Catholic archbishops in the United States 20th-century Roman Catholic archbishops in the United States Union Army chaplains 19th-century Irish people