John Holmes (Maine politician) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Holmes (March 14, 1773 – July 7, 1843) was an

Holmes, a

Holmes, a

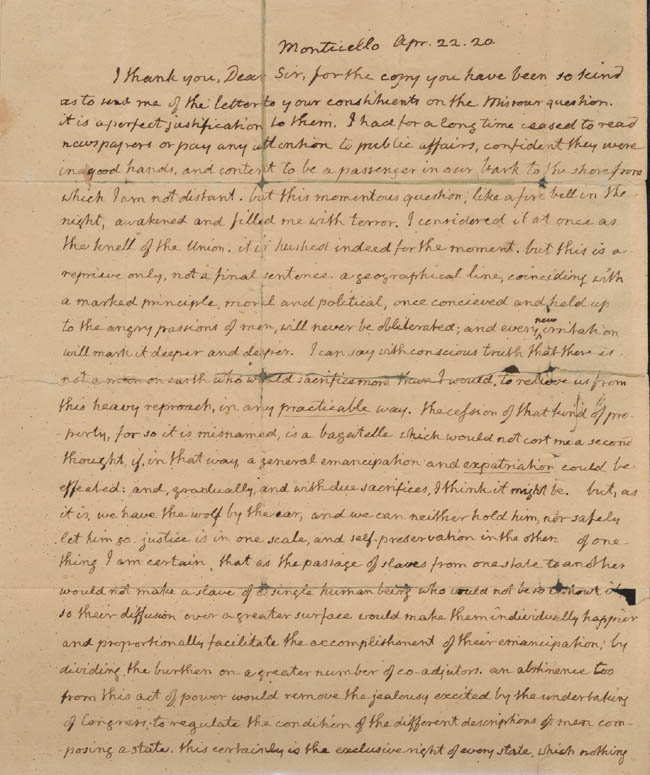

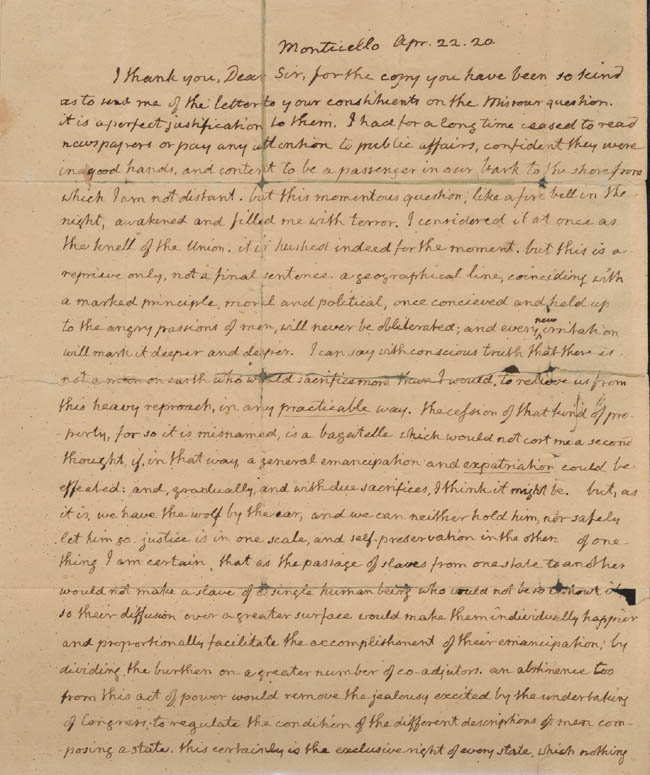

''Letter to Holmes, April 22, 1820''

etter to Holmes, April 20, 1820

Engraving of John Holmes from the Maine Memory Network

{{DEFAULTSORT:Holmes, John (U.S. Politician) 1773 births 1843 deaths Brown University alumni United States senators from Maine Massachusetts state senators Members of the Maine House of Representatives People from Alfred, Maine Politicians from Portland, Maine People from Kingston, Massachusetts Maine Democratic-Republicans Massachusetts National Republicans 19th-century American politicians Maine National Republicans National Republican Party United States senators Democratic-Republican Party United States senators Democratic-Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts Burials at Eastern Cemetery United States Attorneys for the District of Maine People of colonial Massachusetts

American politician

The politics of the United States function within a framework of a constitutional federal republic and presidential system, with three distinct branches that share powers. These are: the U.S. Congress which forms the legislative branch, a bi ...

. He served as a U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

from Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

and was one of the first two U.S. Senators from Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

. Holmes was noted for his involvement in the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

.

Biography

Holmes was born in Kingston in theProvince of Massachusetts Bay

The Province of Massachusetts Bay was a colony in British America which became one of the thirteen original states of the United States. It was chartered on October 7, 1691, by William III and Mary II, the joint monarchs of the kingdoms of ...

, and attended public schools in Kingston. In 1796, he graduated from the College of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (the former name of Brown University) in Providence, Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

. Holmes studied law and was admitted to the bar

An admission to practice law is acquired when a lawyer receives a license to practice law. In jurisdictions with two types of lawyer, as with barristers and solicitors, barristers must gain admission to the bar whereas for solicitors there are dist ...

in 1799, opening a law practice in Alfred in Massachusetts' District of Maine

The District of Maine was the governmental designation for what is now the U.S. state of Maine from October 25, 1780 to March 15, 1820, when it was admitted to the Union as the 23rd state. The district was a part of the Commonwealth of Massachu ...

. At this time, he was also engaged in literary pursuits.

Career

Holmes, a

Holmes, a Democratic-Republican

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

, was elected to the Massachusetts General Court

The Massachusetts General Court (formally styled the General Court of Massachusetts) is the State legislature (United States), state legislature of the Massachusetts, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name "General Court" is a hold-over from th ...

in 1802, 1803, and 1812. He was elected to the Massachusetts State Senate

The Massachusetts Senate is the upper house of the Massachusetts General Court, the bicameral state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The Senate comprises 40 elected members from 40 single-member senatorial districts in the st ...

in 1813 and 1814.

In 1816, Holmes was one of the commissioners under the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

to divide the island

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island ...

s of Passamaquoddy Bay

Passamaquoddy Bay (french: Baie de Passamaquoddy) is an inlet of the Bay of Fundy, between the U.S. state of Maine and the Canadian province of New Brunswick, at the mouth of the St. Croix River. Most of the bay lies within Canada, with its w ...

between the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

and Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

. He was also appointed by the legislature to organize state prisons and revise the Massachusetts criminal code.

Holmes was elected as a United States representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

from Massachusetts in 1816, serving from March 4, 1817, to his resignation on March 15, 1820. During the 16th Congress, Holmes served as chairman of the Committee on Expenditures in the Department of State. Holmes supported William H. Crawford

William Harris Crawford (February 24, 1772 – September 15, 1834) was an American politician and judge during the early 19th century. He served as US Secretary of War and US Secretary of the Treasury before he ran for US president in the 1824 ...

, (a "Crawford Republican"), and John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

. He was opposed to Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

(an "Anti-Jackson").

Holmes supported the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and ...

, and was praised by Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

for his pamphlet ''Mr. Holmes's Letter to the People of Maine''. In the letter, Jefferson thanks Holmes for a copy of this pamphlet. This pamphlet defends Holmes's position on supporting the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and ...

—the admission of Maine as a free state with the admission of Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

as a slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

, which was an unpopular position in Maine. This letter is also notable for being the first written attestation of the phrase " to have the wolf by the ear". Jefferson himself rejected the compromise:

But this momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. it is hushed indeed for the moment. but this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. a geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper. (...) An abstinence too from this act of power would remove the jealousy excited by the undertaking of Congress, to regulate the condition of the different descriptions of men composing a state. this certainly is the exclusive right of every state, which nothing in the constitution has taken from them and given to the general government. could congress, for example say that the Non-freemen of Connecticut, shall be freemen, or that they shall not emigrate into any other state? :— Letter by Thomas Jefferson to John Holmes, April 22, 1820Holmes was later a delegate to the Maine Constitutional Convention. Upon separation from Massachusetts and the admission of Maine as a state, he was elected to the

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

and served from June 13, 1820, to March 3, 1827. Holmes was again elected to the Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Albion Parris, serving from January 15, 1829, to March 3, 1833. During the 17th Congress, Holmes served as chairman of the Committee on Finance (1821–1822); during the 21st Congress, Holmes was chairman of the Committee on Pensions.

After leaving the Senate, Holmes resumed his law practice. From 1836 to 1837, he was a member of the Maine House of Representatives. In 1841, Holmes was appointed as the United States Attorney for the District of Maine, a post he held until his death in Portland on July 7, 1843.

Death and legacy

Holmes was interred in a private tomb of Cotton Brooks, Eastern Cemetery. In 1840, Holmes published ''The Statesman, Or Principles of Legislation and Law'', a law book.Further reading

*"Acquiring Virginia's Treasures."University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with highly selective ad ...

, April 12, 2001. https://web.archive.org/web/20021107202152/http://www.lib.virginia.edu/speccol/exhibits/mellon/acquiring.html

*Kestenbaum, Lawrence. ''Holmes, John (1773–1843)'', '' Political Graveyard''. http://politicalgraveyard.com/bio/holmes.html

* Founders Online''Letter to Holmes, April 22, 1820''

etter to Holmes, April 20, 1820

See also

* Sen. John Holmes HouseFootnotes

External links

Engraving of John Holmes from the Maine Memory Network

{{DEFAULTSORT:Holmes, John (U.S. Politician) 1773 births 1843 deaths Brown University alumni United States senators from Maine Massachusetts state senators Members of the Maine House of Representatives People from Alfred, Maine Politicians from Portland, Maine People from Kingston, Massachusetts Maine Democratic-Republicans Massachusetts National Republicans 19th-century American politicians Maine National Republicans National Republican Party United States senators Democratic-Republican Party United States senators Democratic-Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts Burials at Eastern Cemetery United States Attorneys for the District of Maine People of colonial Massachusetts