John Hewitt (poet) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

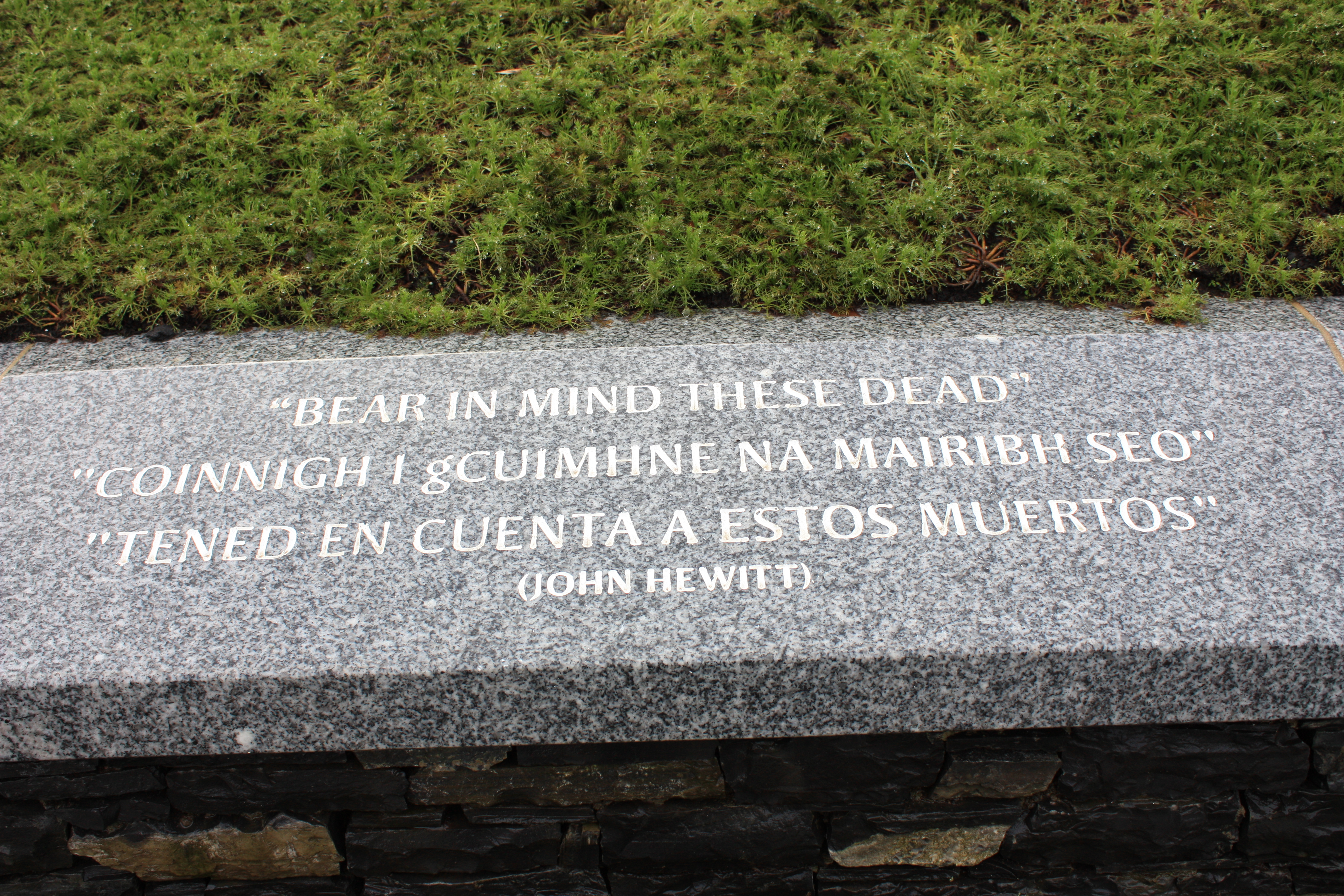

Hewitt's poem ''Neither an Elegy nor a Manifesto'' was recited at the August 2008 remembrance service 10 years after the Omagh bomb. Translations in Irish and Spanish of the final line "Bear in mind these dead" were read out from the site of the blast.Dumigan, Niall; Keenan, Dan: ''Omagh remembers dead 10 years after bombing''

Hewitt's poem ''Neither an Elegy nor a Manifesto'' was recited at the August 2008 remembrance service 10 years after the Omagh bomb. Translations in Irish and Spanish of the final line "Bear in mind these dead" were read out from the site of the blast.Dumigan, Niall; Keenan, Dan: ''Omagh remembers dead 10 years after bombing''

Glens of Antrim Historical Society

1969; 2nd edition 1984) *''The Planter and the Gael: an anthology of poems by John Hewitt & John Montague '' (

Blackstaff Press

1974) *''Time Enough: Poems New and Revised '' (Blackstaff Press, 1976) *''The Rain Dance: Poems New and Revised '' (Blackstaff Press, 1978) *''Kites in Spring: a Belfast boyhood '' (Blackstaff Press, 1980) *''The Selected John Hewitt '' (Blackstaff Press, 1981) *''Mosaic '' (Blackstaff Press, 1981) *''Loose Ends '' (Blackstaff Press, 1983) *''Freehold and Other Poems '' (Blackstaff Press, 1986) *''The Collected Poems of John Hewitt (Ed.

Lagan Press

1999)

The John Hewitt Collection at the University of UlsterThe John Hewitt BarThe John Hewitt International Summer SchoolThe John Hewitt Collection at the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hewitt, John 1907 births 1987 deaths British art Male writers from Northern Ireland 20th-century writers from Northern Ireland Irish art British poets Writers from Belfast People educated at Methodist College Belfast 20th-century Irish poets 20th-century British male writers British male poets Alumni of Stranmillis University College

John Harold Hewitt (28 October 1907 – 22 June 1987) was perhaps the most significant Belfast

John Hewitt Collection, University of Ulster, accessed 27 August 2007 From November 1930 to 1957, Hewitt held positions in the Belfast Museum & Art Gallery. His radical socialist ideals proved unacceptable to the Belfast Unionist establishment and he was passed over for promotion in 1953. Instead in 1957 he moved to

John Hewitt Collection, University of Ulster, accessed 27 August 2007 He was attracted to the

, John Hewitt International Summer School, accessed 27 August 2007 John Hewitt officially opened the Belfast Unemployed Resource Centre (BURC) Offices on Mayday 1985. His life and work are celebrated in two prominent ways – the annual John Hewitt International Summer School – and, less conventionally, a Belfast pub is named after him – the John Hewitt Bar and Restaurant, which is situated on the city's Donegall Street and which opened in 1999. The bar was named after him as he officially opened the Belfast Unemployed Resource Centre, which owns the establishment. It is a popular meeting place for local writers, musicians, journalists, students and artists. Both the

His life and work are celebrated in two prominent ways – the annual John Hewitt International Summer School – and, less conventionally, a Belfast pub is named after him – the John Hewitt Bar and Restaurant, which is situated on the city's Donegall Street and which opened in 1999. The bar was named after him as he officially opened the Belfast Unemployed Resource Centre, which owns the establishment. It is a popular meeting place for local writers, musicians, journalists, students and artists. Both the

– until 1954; the Belfast Lyric Players performed a stage version in 1957, which they revived in 1986), which tells of a legendary massacre of Roman Catholics by poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems ( oral or wri ...

to emerge before the 1960s generation of Northern Irish poets that included Seamus Heaney

Seamus Justin Heaney (; 13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature.

, Derek Mahon

Derek Mahon (23 November 1941 – 1 October 2020) was an Irish poet. He was born in Belfast, Northern Ireland but lived in a number of cities around the world. At his death it was noted that his, "influence in the Irish poetry community, lit ...

and Michael Longley

Michael Longley, (born 27 July 1939, Belfast, Northern Ireland), is an Anglo-Irish poet.

Life and career

One of twin boys, Michael Longley was born in Belfast, Northern Ireland, to English parents, Longley was educated at the Royal Belfast A ...

. He was appointed the first writer-in-residence at Queen's University Belfast in 1976. His collections include ''The Day of the Corncrake'' (1969) and ''Out of My Time: Poems 1969 to 1974'' (1974). He was also made a Freeman of the City of Belfast in 1983, and was awarded honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hon ...

s by the University of Ulster

sco, Ulstèr Universitie

, image = Ulster University coat of arms.png

, caption =

, motto_lang =

, mottoeng =

, latin_name = Universitas Ulidiae

, established = 1865 – Magee College 1953 - Magee Un ...

and Queen's University Belfast.John Hewitt (1907–1987)John Hewitt Collection, University of Ulster, accessed 27 August 2007 From November 1930 to 1957, Hewitt held positions in the Belfast Museum & Art Gallery. His radical socialist ideals proved unacceptable to the Belfast Unionist establishment and he was passed over for promotion in 1953. Instead in 1957 he moved to

Coventry

Coventry ( or ) is a city in the West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its city status until the Middle Ages. The city is governed b ...

, a city still rebuilding following its devastation during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Hewitt was appointed Director of the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum where he worked until retirement in 1972.

Hewitt had an active political life, describing himself as "a man of the left", and was involved in the British Labour Party, the Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. T ...

and the Belfast Peace League.John Hewitt: Man of the LeftJohn Hewitt Collection, University of Ulster, accessed 27 August 2007 He was attracted to the

Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

dissenting tradition and was drawn to a concept of regional identity within the island of Ireland, describing his identity as Ulster, Irish, British and European.Biography: John Harold Hewitt (1907–1987), John Hewitt International Summer School, accessed 27 August 2007 John Hewitt officially opened the Belfast Unemployed Resource Centre (BURC) Offices on Mayday 1985.

His life and work are celebrated in two prominent ways – the annual John Hewitt International Summer School – and, less conventionally, a Belfast pub is named after him – the John Hewitt Bar and Restaurant, which is situated on the city's Donegall Street and which opened in 1999. The bar was named after him as he officially opened the Belfast Unemployed Resource Centre, which owns the establishment. It is a popular meeting place for local writers, musicians, journalists, students and artists. Both the

His life and work are celebrated in two prominent ways – the annual John Hewitt International Summer School – and, less conventionally, a Belfast pub is named after him – the John Hewitt Bar and Restaurant, which is situated on the city's Donegall Street and which opened in 1999. The bar was named after him as he officially opened the Belfast Unemployed Resource Centre, which owns the establishment. It is a popular meeting place for local writers, musicians, journalists, students and artists. Both the Belfast Festival at Queen's

Belfast International Arts Festival, formerly known as Belfast Festival at Queen’s, claims to be the city’s longest running international arts event.

Originally established in 1962, it was hosted by Queen’s University until 2015, after whi ...

and the Belfast Film Festival

The Belfast Film Festival is Northern Ireland's largest film festival, attracting over 25,000 people annually. Since its founding in 1995, the festival has grown to include the Docs Ireland international documentary festival, as well as an Audi ...

use the venue to stage events.

Hewitt's life and writing

Early life

After attending Agnes Street National School, Hewitt attended theRoyal Belfast Academical Institution

The Royal Belfast Academical Institution is an independent grammar school in Belfast, Northern Ireland. With the support of Belfast's leading reformers and democrats, it opened its doors in 1814. Until 1849, when it was superseded by what today is ...

from 1919 to 1920 before moving to Methodist College Belfast

God with us

, established = 1865

, type = Voluntary grammar

, religion = Interdenominational

, principal = Jenny Lendrum

, chair_label = Chairwoman

, chair = Revd. Dr Janet Unsworth

, founder ...

, where he was a keen cricketer. In 1924, he started an English degree at the Queen's University of Belfast, obtaining a BA in 1930,The John Hewitt Papers (D/3838)Public Record Office of Northern Ireland

The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) is situated in Belfast, Northern Ireland. It is a division within the Engaged Communities Group of the Department for Communities (DfC).

The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland is disti ...

, accessed 27 August 2007 which he followed by obtaining a teaching qualification from Stranmillis College, Belfast. During these years, his calling to radical and socialist causes deepened; he heard James Larkin

James Larkin (28 January 1874 – 30 January 1947), sometimes known as Jim Larkin or Big Jim, was an Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. He was one of the founders of the Irish Labour Party along with James Connolly and Willia ...

address a Labour rally, began to write for a range of Trades Union and Socialist publications, and co-founded a journal entitled ''Iskra''. Hewitt also attended the Northern Ireland Labour Party

The Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP) was a political party in Northern Ireland which operated from 1924 until 1987.

Origins

The roots of the NILP can be traced back to the formation of the Belfast Labour Party in 1892. William Walker stoo ...

Annual Conference as a Belfast City delegate in 1929 and 1930. He resisted the advocacy of a workers’ republic in the party's constitution.

In 1930, Hewitt was appointed Art Assistant at the Belfast Museum and Art Gallery

The Ulster Museum, located in the Botanic Gardens in Belfast, has around 8,000 square metres (90,000 sq. ft.) of public display space, featuring material from the collections of fine art and applied art, archaeology, ethnography, treasures ...

, where amongst other duties, he gave public lectures on art, at one of which he met Roberta "Ruby" Black, whom he was to marry in 1934. Roberta was also a convinced Socialist, and the couple became members of the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

, the Belfast Peace League, the Left Book Club and the British Civil Liberties Union.

Early writing

Hewitt began experimenting with poetry while still a schoolboy at Methodist College in the 1920s. Typically thorough, his notebooks from these years are filled with hundreds of poems, in dozens of styles; Hewitt's main influences at this time includedWilliam Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. ...

, William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

and W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

, and for the most part the verse is either highly romantic, or strongly socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

, a theme which increased in prominence as the 1930s began. Morris is the key figure, combining both these strains, and allowing Hewitt to articulate the radical, dissenting

Dissent is an opinion, philosophy or sentiment of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or policy enforced under the authority of a government, political party or other entity or individual. A dissenting person may be referred to as ...

strain which he inherited from his Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

forbearers, including his father.

As the 1920s moved into the 1930s, Hewitt's writing began to develop and mature. Firstly, his role models (including Vachel Lindsay

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay (; November 10, 1879 – December 5, 1931) was an American poet. He is considered a founder of modern ''singing poetry,'' as he referred to it, in which verses are meant to be sung or chanted.

Early years

Lindsay was bor ...

) became more modern; secondly, he discovered in Chinese poetry a voice which was "quiet and undemonstrative but clear and direct", and which answered a part of Hewitt's temperament which had been suppressed. Finally, and most importantly, he began his lifelong work of excavation and discovery of the poetry of Ulster, starting with Richard Rowley, Joseph Campbell and George William Russell

George William Russell (10 April 1867 – 17 July 1935), who wrote with the pseudonym Æ (often written AE or A.E.), was an Irish writer, editor, critic, poet, painter and Irish nationalist. He was also a writer on mysticism, and a centra ...

(AE). This research culminated, in part, with the publications of ''Fibres, Fabric and Cordage'' in 1948, ''Rhyming Weavers and other Country Poets of Antrim and Down'' (based on his MA thesis, ''Ulster Poets 1800–1870'' of 1951) in 1974, and a book called ''The Rhyming Weavers'' in 1979. All of these publications and more, were based on his interest in the Ulster rhyming weaver poets of the 19th century, such as Henry MacDonald Flecher, David Herbison

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

, Alexander MacKenzie, James MacKowen, and James Orr.

Hewitt himself felt that his juvenilia ended with the poem ''Ireland'' (1932), which he placed at the start of his ''Collected Poems'' (1968), and indeed it is more complex than most of his earlier work, and begins his lifelong preoccupation with bleak landscapes of bog and rock; with exile, and with the nature of belonging.

The 1930s

The 1930s was a period of transition in Hewitt's poetry, one in which he began seriously to address the tortured history of his native province, and the contradictions between his love for the people and the landscape, his inspiration in the radical dissenting tradition, and the bloody, fratricidal conflicts which scar Northern Ireland to this day. A key text is ''The Bloody Brae: A Dramatic Poem'' (finished in 1936, though not broadcast – on the Northern Ireland Home Service of theBBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Cromwellian

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in History of England, English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 ...

troops in Islandmagee

Islandmagee () is a peninsula and civil parish on the east coast of County Antrim, Northern Ireland, located between the towns of Larne and Whitehead. It is part of the Mid and East Antrim Borough Council area and is a sparsely populated rural ...

, County Antrim, in 1642. John Hill, one of the soldiers who has been racked by guilt since he participated in the slaughter, returns many years later to beg forgiveness. This he receives from the ghost of one of his victims, a gesture which she wraps in a condemnation of his self-indulgence, luxuriating in his guilt rather than taking positive action to combat bigotry. Another theme which was to become a fixture in Hewitt's poetry also first appears in ''The Bloody Brae''; that is, a bold assertion of the right of his people to live in Ulster, rooted in their hard work and commitment to it:

:This is my country; my grandfather came here

:and raised his walls and fenced the tangled waste

:and gave his years and strength into the earth

Also in the 1930s, Hewitt was involved with a group of young artists and sculptors known as the 'Ulster Unit', and acted as their secretary.

1940s and 1950s

From the late thirties Hewitt was one of a set ofLinen Hall Library

The Linen Hall Library is located at 17 Donegall Square North, Belfast, Northern Ireland. It is the oldest library in Belfast and the last subscribing library in Northern Ireland. The Library is physically in the centre of Belfast, and more g ...

members who would regularly retire to Campbell's Cafe in Belfast's city centre. The regulars, at various points, included writers John Boyd, Denis Ireland

Denis Liddell Ireland (29 July 1894 – 23 September 1974) was an Irish essayist and political activist. A northern Protestant, after service in the First World War he embraced the cause of Irish independence. He also advanced the social credit id ...

, Sam Hanna Bell

Sam Hanna Bell (16 October 1909 – 9 February 1990) was a Scottish-born Northern Irish novelist, short story writer, playwright, and broadcaster.

Bell was born in Glasgow to Ulster Scots parents. Following the sudden death of his father in ...

and Richard Rowley, actors Joseph Tomelty

Joseph Tomelty (5 March 1911 – 7 June 1995) was an Irish actor, playwright, novelist, short-story writer and theatre manager. He worked in film, television, radio and on the stage. starring in Sam Thompson's 1960 play ''Over the Bridge''.

...

, Jack Loudon and J.G. Devlin

James Gerard Devlin (8 October 1907 – 17 October 1991) was a Northern Irish actor who made his stage debut in 1931, and had long association with the Ulster Group Theatre. In a career spanning nearly sixty years, he played parts in TV pro ...

, the poet Robert Greacen

Robert Greacen (1920–2008) was an Irish poet and member of Aosdána. Born in Derry, Ireland, on 24 October 1920, he was educated at Methodist College Belfast and Trinity College Dublin. He died on 13 April 2008 in Dublin, Ireland.

Greacen's ...

, artists Padraic Woods, Gerard Dillon, Harry Cooke Knox and William Conor

William Conor OBE RHA PPRUA ROI (1881–1968) was a Belfast-born artist.

Celebrated for his warm and sympathetic portrayals of working-class life in Ulster, William Conor studied at the Government School of Design in Belfast in the 1890s ...

and (an outspoken opponent of sectarianism) the Rev. Arthur Agnew. The ebullient atmosphere the circle created was a backdrop to the appearance of Campbell's Cafe in Brian Moore's wartime ''Bildungsroman

In literary criticism, a ''Bildungsroman'' (, plural ''Bildungsromane'', ) is a literary genre that focuses on the psychological and moral growth of the protagonist from childhood to adulthood (coming of age), in which character change is import ...

'', The Emperor of Ice-Cream.

During the 1940s and 1950s, Hewitt increasingly played the role of reviewer and art critic. He gained an MA from Queen's University Belfast, with a thesis on Ulster poets from 1800–1870, in 1951. In 1951 he had been appointed deputy director and keeper of art at the Belfast Museum and Art Gallery

The Ulster Museum, located in the Botanic Gardens in Belfast, has around 8,000 square metres (90,000 sq. ft.) of public display space, featuring material from the collections of fine art and applied art, archaeology, ethnography, treasures ...

but in 1957, Hewitt left to take up the position of Art Director at the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum in Coventry

Coventry ( or ) is a city in the West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its city status until the Middle Ages. The city is governed b ...

, a position he held until 1972.Frank Ormsby, ‘Hewitt, John Harold (1907–1987)’, rev. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

, Oxford University Press, 2004 While in Coventry

Coventry ( or ) is a city in the West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its city status until the Middle Ages. The city is governed b ...

, Hewitt started work on his unpublished autobiography, ''A North Light''. He subsequently returned to Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

on his retirement in 1972. The John Hewitt Estate and Four Courts Press

Four Courts Press is an independent Irish academic publishing house, with its office at Malpas Street, Dublin 8, Ireland.

Founded in 1970 by Michael Adams, who died in February 2009, its early publications were primarily theological, notably t ...

published ''A North Light: twenty-five years in a Municipal Gallery'' in 2013.

Legacy

The John Hewitt Society was established in 1987 to commemorate his life and work. Its mission is "to promote literature, arts, and culture inspired by the ideals and ideas of the poet John Hewitt". The Society runs an annual summer school.Bibliography

Poetry

Irish Times

''The Irish Times'' is an Irish daily broadsheet newspaper and online digital publication. It launched on 29 March 1859. The editor is Ruadhán Mac Cormaic. It is published every day except Sundays. ''The Irish Times'' is considered a newspaper ...

16 August 2008

Other poems include:

*''Conacre ''(privately printed, 1943)

*''No Rebel Word ''(Frederick Muller, 1948)

*''The Lint Pulling ''(1948)

*''Those Swans Remember: a poem ''(privately printed, 1956)

*''Tesserae ''(Queen’s University Belfast Festival Publication, 1967)

*''Collected Poems 1932–1967 ''(MacGibbon & Kee, 1968)

*''The Day of the Corncrake: poems of the nine glens 'Glens of Antrim Historical Society

1969; 2nd edition 1984) *''The Planter and the Gael: an anthology of poems by John Hewitt & John Montague '' (

Arts Council of Northern Ireland

The Arts Council of Northern Ireland (Irish: ''Comhairle Ealaíon Thuaisceart Éireann'', Ulster-Scots: ''Airts Cooncil o Norlin Airlan'') is the lead development agency for the arts in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1964, as a successor to ...

, 1970)

*''An Ulster Reckoning ''(privately printed, 1971)

*''The Chinese Fluteplayer ''(privately printed, 1974)

*''Scissors for a One-Armed Tailor: Marginal Verses 1929–1954 ''(privately printed, 1974)

*''Out of My Time: poems 1967–1974 ''Blackstaff Press

1974) *''Time Enough: Poems New and Revised '' (Blackstaff Press, 1976) *''The Rain Dance: Poems New and Revised '' (Blackstaff Press, 1978) *''Kites in Spring: a Belfast boyhood '' (Blackstaff Press, 1980) *''The Selected John Hewitt '' (Blackstaff Press, 1981) *''Mosaic '' (Blackstaff Press, 1981) *''Loose Ends '' (Blackstaff Press, 1983) *''Freehold and Other Poems '' (Blackstaff Press, 1986) *''The Collected Poems of John Hewitt (Ed.

Frank Ormsby

Francis Arthur Ormsby (born 1947) is a Northern Irish author and poet.

Life

Frank Ormsby was born in Irvinestown, County Fermanagh. He was educated at St Michael's College, Enniskillen and then Queen's University Belfast.

From 1976 until his r ...

) '' (Blackstaff Press, 1991)

Prose

*''Ancestral Voices: the selected prose of John Hewitt (Ed. Tom Clyde) ''(Blackstaff Press, 1987)Drama

*''Two Plays: The McCrackens, The Angry Dove (Ed. Damian Smyth) 'Lagan Press

1999)

Art criticism

*'' Colin Middleton ''(Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon and the Arts Council of Northern Ireland, 1976) *''Art in Ulster (with Mike Catto) ''(Blackstaff Press, 1977) *'' John Luke (artist) 1906–1975 ''(Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon and the Arts Council of Northern Ireland, 1978)Editor

*''The Poems ofWilliam Allingham

William Allingham (19 March 1824 – 18 November 1889) was an Irish poet, diarist and editor. He wrote several volumes of lyric verse, and his poem "The Faeries" was much anthologised. But he is better known for his posthumously published ''Di ...

''(Oxford University Press/ Dolmen Press, 1967)

See also

*List of Irish writers

This is a list of writers either born in Ireland or holding Irish citizenship, who have a Wikipedia page. Writers whose work is in Irish are included.

Dramatists A–D

*John Banim (1798–1842)

* Ivy Bannister (born 1951)

*Sebastian Barry (born ...

References

External links

The John Hewitt Collection at the University of Ulster

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hewitt, John 1907 births 1987 deaths British art Male writers from Northern Ireland 20th-century writers from Northern Ireland Irish art British poets Writers from Belfast People educated at Methodist College Belfast 20th-century Irish poets 20th-century British male writers British male poets Alumni of Stranmillis University College